Origin and History of Tree of Jesse Iconography

Before discussing the fifteenth and early sixteenth-century use of Tree of Jesse imagery, it is first essential to understand the origin and history of the iconography. The term ‘Tree of Jesse’, used so widely today, may not have been universally recognised in the late medieval period, as it does not occur in either scripture or medieval biblical exegesis. The Vulgate discusses the ‘virga de radice Jesse’ (the rod, or shoot, out of the root of Jesse), and one of the earliest references to a pictorial representation of the subject, in the twelfth century, describes it as the ‘Stirps Iesse’ (stem of Jesse).16 In the vernacular it has been referred to in several different ways. Two early sixteenth-century German contracts describe it as the ‘der stam Jesse’ (the root/trunk of Jesse), or ‘König Jesse Mit ainem Aufwachsenden stamb’ (King Jesse with a growing root/trunk).17 In addition, an English document of 1635, which mentions the original late medieval stained glass in the Lady Chapel of Winchester Cathedral, talks about a now lost window as painted with the ‘Genealogie from the Root of Jesse’.18 Consequently, even though ‘boem van Jesse’ (tree of Jesse) can be found in a Flemish contract of 1474,19 it seems that the use of ‘Tree of Jesse’ as a general term to classify the iconography was not commonplace until the eighteenth century.20 Nevertheless, for the purpose of clarity, the term will be used throughout this book.

As an illustration of a prophecy fulfilled by the Incarnation, the Tree of Jesse, the genealogical tree of Christ, had been a favourite theme throughout the Middle Ages. Isaiah had prophesised that a Messiah would be born to the family of Jesse, the father of King David, Isaiah 11:1–3, ‘et egredietur virga de radice Jesse et flos de radice eius ascendet’.

And there shall come forth a rod out of the root of Jesse, and a flower shall rise up out of his root. And the spirit of the Lord shall rest upon him: the spirit of wisdom, and of understanding, the spirit of counsel, and of fortitude, the spirit of knowledge, and of godliness. And he shall be filled with the spirit of the fear of the Lord. He shall not judge according to the sight of the eyes, nor reprove according to the hearing of the ears.

This passage, combined with the genealogy at the beginning of Saint Matthew’s Gospel, related again by Saint Luke, provided the textual basis for the iconography.21 Support for the prophecy was found in Revelation 22:16, ‘I Jesus have sent my angel, to testify to you these things in the churches. I am the root and stock of David, the bright and morning star’, and also in the Epistle of Saint Paul to the Romans 15:12, ‘And again Isaias saith: There shall be a root of Jesse; and he that shall rise up to rule the Gentiles, in him the Gentiles shall hope’. It was further enriched at the beginning of the third century, when the early Christian author Tertullian linked the Vulgate Latin word for rod, virga with the Virgin virgo and the flower flos with Christ.22

Is it not because he is himself the flower from the stem [rod] which came forth from the root of Jesse, while the root of Jesse is the house of David, and the stem [rod] from the root is Mary, descended from David, that the flower from the stem [rod], the Son of Mary, who is called Jesus Christ, must himself also be the fruit?

Tertullian’s interpretation was reaffirmed in the fourth century by Saint Ambrose, in his text on the Holy Spirit, Book II, Chapter 5, verse 38, ‘The root of Jesse the patriarch is the family of the Jews, Mary is the rod, Christ the flower of Mary, Who, about to spread the good odour of faith throughout the whole world, budded forth from a virgin womb’.23 It was affirmed again by Saint Jerome in his letter XXII to Eustochium:

There shall come forth a rod out of the stem of Jesse, and a flower shall grow out of his roots. The rod is the mother of the Lord—simple, pure, unsullied; drawing no germ of life from without but fruitful in singleness like God Himself. The flower of the rod is Christ, who says of Himself: I am the rose of Sharon and the lily of the valleys.24

The messianic prophecies of the Old Testament are, therefore, realised in the incarnation of Christ through the lineage of David and the virgin birth. This concept, which was seen to emphasise the prefigurative significance of the biblical passage, became commonplace in early medieval commentaries.

Isaiah played a central role in providing scriptural authority for many of the widely held beliefs regarding the Virgin, and he alone among the prophets seems to refer to her explicitly, Isaiah 7:14, ‘Therefore the Lord himself shall give you a sign. Behold a virgin shall conceive, and bear a son and his name shall be called Emmanuel’.25 This passage, along with that relating to Jesse, became an essential part of the liturgy for Advent, and the prophecy is further recalled in one of the Greater Antiphons, O Radix Jesse, which was prescribed by the eighth century for Vespers on the Wednesday of Ember week.26

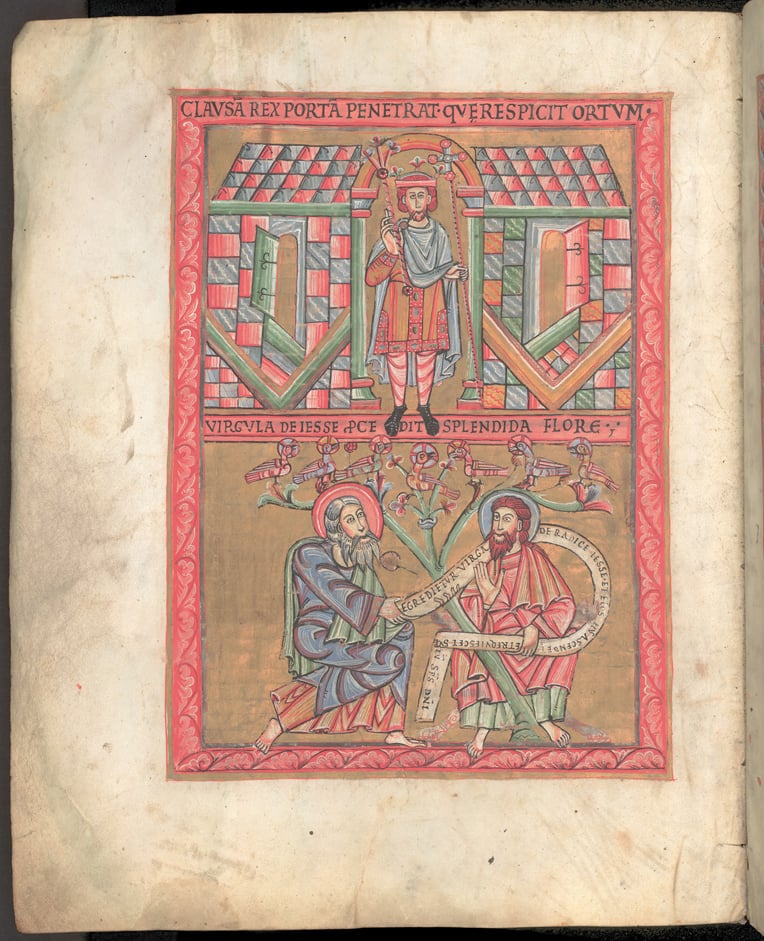

In pictorial representations of the subject, it is possible to see an evolution in the iconography over a relatively short space of time.27 The first images present the most literal interpretation of Isaiah’s text and usually show Jesse alone, with the tree growing from his body. The placement of the trunk is varied, and can be depicted either growing from Jesse’s head, shoulders, heart, stomach or groin. These different placements have been discussed by Christiane Klapisch-Zuber, who distinguishes between those she considers carnal, with their obvious association with the origin of life, and those she considers spiritual.28 By the mid-fifteenth century, however, the most popular form of representation has the trunk growing from Jesse’s heart.29 Resting on the flowers of the tree are doves, which relate to the second part of Isaiah’s prophecy and represent the gifts of the Holy Spirit.30 The earliest known depiction of the subject occurs in a Bohemian manuscript dated 1086, which may have originated in the circle of the scriptorium at the Monastery of Saint Emmeram in Regensburg (National Library of the Czech Republic, MS XIV, A.13, fol.4v) (Figure 0.1).31 This manuscript, known as the Vyšehrad Codex, contains the Coronation Gospels of King Vratislav II, the first monarch of Bohemia. The image is located on the lower register of the page preceding the Gospel of Saint Matthew, with a representation of the closed gate of Ezekiel, commonly interpreted as a prefiguration of the virgin birth, in the upper register.32 The previous page features illustrations of the virga Aaron and the virga Moses, which were also seen as prefigurations of the Incarnation.33 Therefore, all four images appear to relate to the virgin birth of Christ, even though the Virgin and Christ are not actually depicted. The virga Aaron and virga Moses have an obvious association with the virga Jesse and, consequently, it is not unusual to find Moses and/or Aaron appearing in later Tree of Jesse imagery.34 In the Vyšehrad Codex, Isaiah is depicted with a scroll that bears the text of his prophecy ‘et egredietur virga de radice Jesse’, which wraps around the seated figure of Jesse. A tree grows from beneath Jesse’s foot and seven haloed doves perch on the blooming

Figure 0.1 The Vyšehrad Codex, c.1086

National Library of the Czech Republic, Kodex Vyšehradský, Shelfmark: XIV.A.13.fol.4v

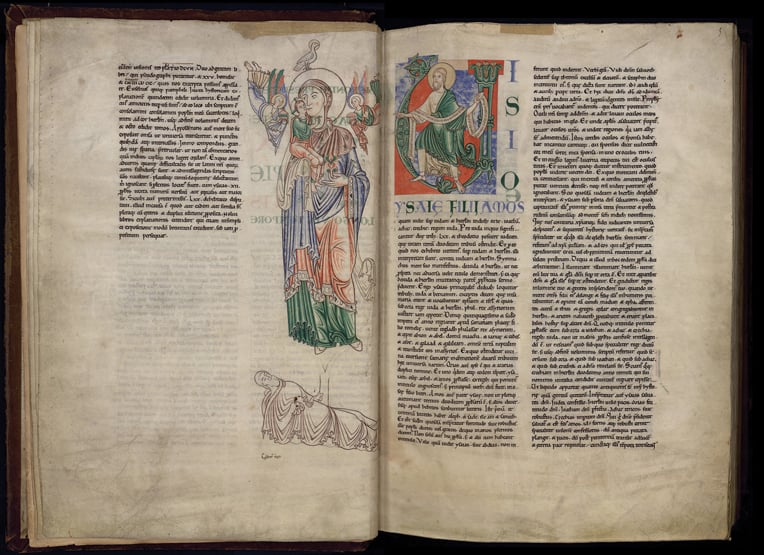

branches. Across the top of the image a Latin inscription reads ‘Virgula de Iesse p[ro] cedit splendida flore’ (the rod of Jesse produces a splendid flower). A later representation of Jesse depicted with seven doves can be found in the Bible of Saint-Bénigne, (Bibliothèque municipale de Dijon, MS00002, fol.148r) (Figure 0.2), thought to date from the second quarter of the twelfth century. This miniature appears at the beginning of the Book of Isaiah, filling the centre of the opening initial of Visio Isaie.35

Figure 0.2 Tree of Jesse Detail From the Bible of Saint-Bénigne, Twelfth Century

Bibliothèque municipale de Dijon, MS00002, fol.148r

A further group of images incorporate the second prophecy of Isaiah, ‘Behold a virgin shall conceive, and bear a son, and his name shall be called Emmanuel’. These images emphasise the role of the Virgin as the mother of Christ. One of the earliest to assign her a preeminent position can be found in a manuscript from the Abbey of Cîteaux in Burgundy (Bibliothèque municipale de Dijon, MS00129, fols.4v and 5r) (Figure 0.3). This manuscript, the S. Hieronymi Explanatio in Isaiam, contains Saint Jerome’s commentary on Isaiah and has been dated to c.1125. Jesse appears asleep at the bottom of the tree; he holds the trunk with his left hand and where the trunk splits into two, the Virgin stands with the Christ Child in her arms. In her left hand she appears to hold a twig, presumably a further reference to the prophecy, and a single dove rests on her halo, which may intend to imply a dual meaning. On the opposite page, Isaiah stands in the initial letter with a scroll inscribed with the text of both of his prophecies, ‘et egredietur virga’, and ‘ecce virgo concipiet’. He points to the image on the adjoining page to indicate that this is the fulfilment of those prophecies. This conflation of Isaiah’s prophecies gives prominence to the Virgin’s role in the Incarnation, and she may even form the virga, the shoot of the tree, as in a miniature from the twelfth-century Lambeth Bible (Lambeth Palace Library, Ms.3, fol.198r) (Figure 0.4).

Figure 0.3 S. Hieronymi Explanatio in Isaiam, c.1125

Bibliothèque municipale de Dijon, MS00129, fols.4v and 5r

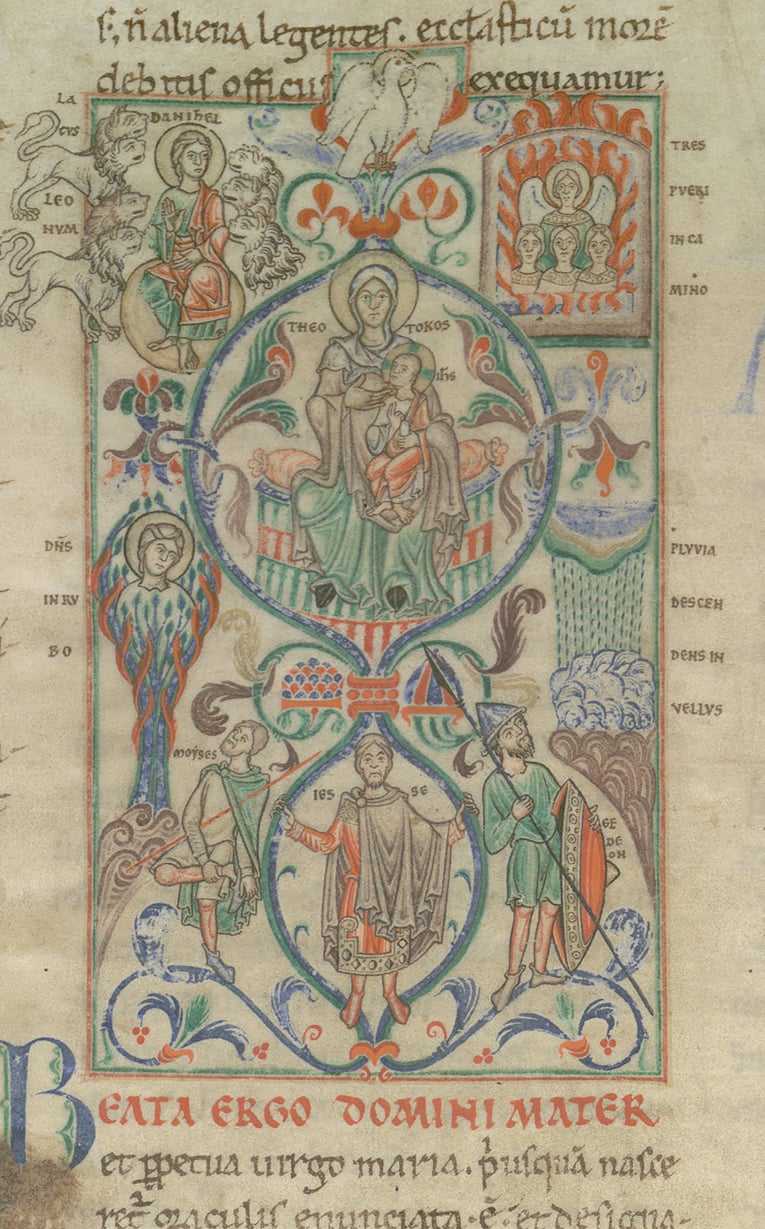

In another manuscript of a similar date, also from Cîteaux, the Virgin can be seen enthroned in the tree (Bibliothèque municipale de Dijon, MS00641, fol.40v) (Figure 0.5). Known as the Vitae Sanctorum, or the Légendaire de Cîteaux, and dated c.1110–20, this miniature also incorporates four other Old Testament prefigurations: Daniel and the Lion’s Den, Moses and the Burning Bush, Gideon and his Fleece and the Three Young Men and the Fiery Furnace.36 These prefigurations, which also came to be

Figure 0.5 Tree of Jesse Detail From the Légendaire de Cîteaux, c.1110–20

Bibliothèque municipale de Dijon, MS00641, fol.40v

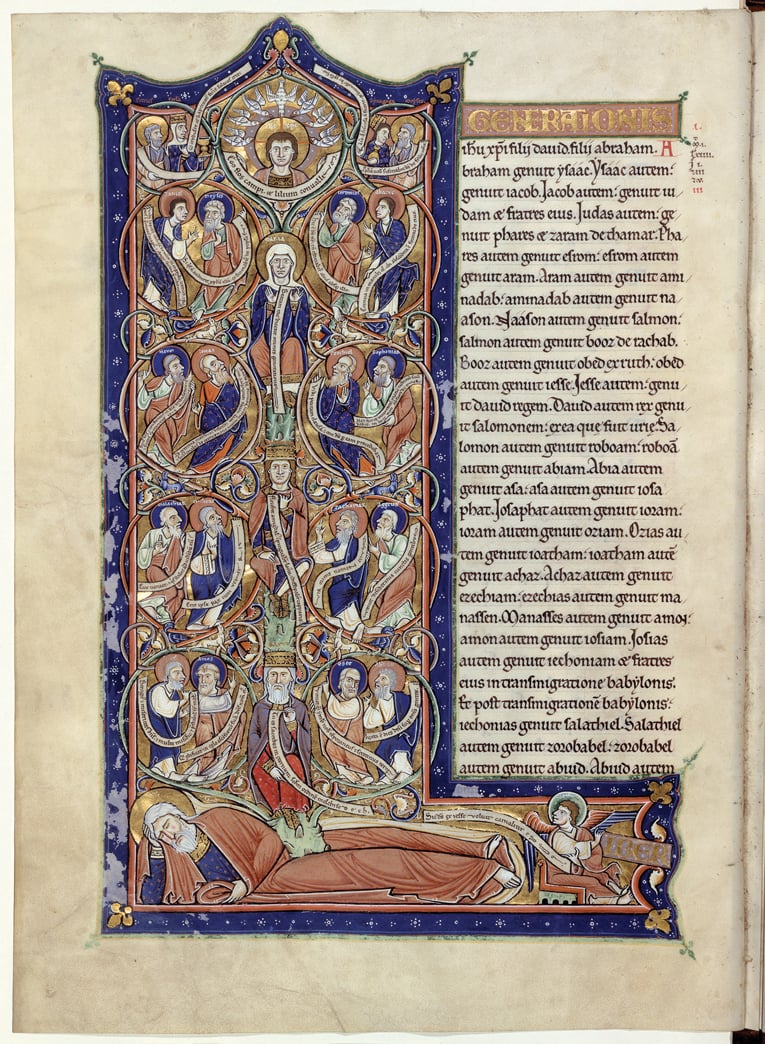

associated with the Virgin and Birth of Christ, can often be found represented alongside Tree of Jesse iconography. In other miniatures, Mary appears without prefigurations, but with King David, occasionally Solomon, and sometimes prophets, as in two twelfth-century manuscripts in the British Library: the Shaftesbury Psalter (Lands-downe 383, fol.15r) and the Winchester Psalter (Cotton MS Nero C IV, fol.9r).37 Examples can also be found in illuminated Bibles, where the Tree of Jesse was often used to illustrate the beginning of the Book of Isaiah or Gospel of Matthew, as in the twelfth-century Bible of Saint Bertin in Paris (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Latin 16746, fol.7v), where a Tree of Jesse decorates the first initial of the Liber generationis of the first chapter of Matthew (Figure 0.6). Although not explicit from a reading of the Gospels, it is unsurprising that in time the Tree of Jesse also came to be seen as the genealogical tree of the Virgin and, as such, an affirmation of her Davidic and royal paternity.

This notion is evident in more complex representations that depict the extended genealogy from Jesse through David to the Virgin and Christ. In these images, Jesse is shown sleeping at the base of the tree in a semi-reclining position, sometimes under a tent-shaped canopy.38 The tree that grows from his body branches out to accommodate the ancestors of Christ, who are depicted among the foliage. David is almost always shown with his harp, particularly in later representations, and sometimes Solomon can be identified from his turban. The number of secondary ancestors featured varies, depending on the space available. Crowning the tree are the Virgin and Christ, shown either separately or together, and sometimes surrounded by doves. It is also common to see prophets with scrolls inscribed with a quotation from the text of their prophecies; they are often shown in an animated state and may point to Christ as the foretold Messiah. Many early stained glass windows also include other attributes around Jesse; examples include a suspended lamp, which Watson has suggested may be symbolic of the eternal light of Christ.39

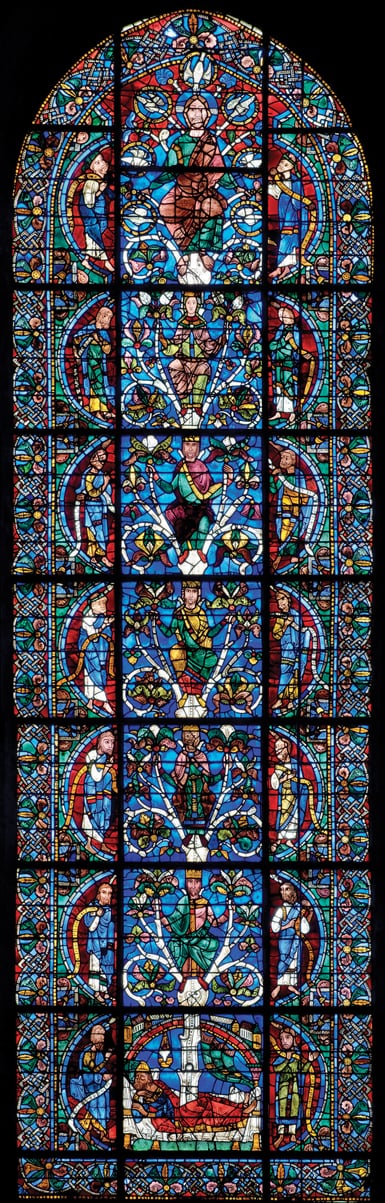

The earliest known example of this type of extended iconography appeared in the stained glass window commissioned in 1144 by Abbot Suger for the new choir of Saint Denis in Paris.40 Unfortunately, this window has been extensively altered by restoration, although it is believed that the Jesse window located beneath the rose at the west end of Chartres Cathedral, dated only a few years later and considerably better preserved, is an almost identical copy of Suger’s window (Figure 0.7).41 Suger’s design appears to have been popular for stained glass, and many twelfth- and early thirteenth-century windows throughout northern Europe are thought to have derived from the Saint Denis and Chartres model.42

By the mid-fifteenth century, the Tree of Jesse was a well established and familiar typological motif, when it seems there was a standardisation in pictorial representations of the subject. The most common number of kings depicted was now twelve, which was probably linked to the idea of the twelve tribes of Israel. This appears to derive from Acts 7:8, which states that Abraham’s son was Isaac and that his son was Jacob, the father of the twelve patriarchs who were the founders of the twelve tribes of Israel. This was perhaps also intended to provide an analogy with the twelve apostles, or the twelve fruits on the Tree of Life.43 When named, the kings usually follow the order of twelve of the fourteen kings described by Matthew, starting with David, before the transmigration of Babylon.44 Although by now commonplace, this was not an entirely new idea, as a twelfth-century precedent for the depiction of twelve kings can be found on the north doorway of the Baptistery at Parma. In addition, the

Figure 0.6 Bible of Saint Bertin, Twelfth Century

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Latin 16746, fol.7v

kings were now often shown as half figures in blossoms of flowers on the tree; a precedent for this type of representation can be found in a Parisian Bible Historiale dated c.1414–15 (Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels, Ms.9002, fol.223r) (Figure 0.8).45 Seven doves, representing the gifts of the Holy Spirit, also became rarer, presumably because the image now appears to focus more on the genealogy of Christ and

the Virgin, and less on a literal translation of the messianic prophecy. Despite this, it remains usual to find two or four prophets depicted on either side of Jesse. As will be seen in the following chapters, representations of a seated Jesse also became more widespread, particularly in northern France and the Netherlands, and representations of the Virgin on a crescent moon, the antique symbol of chastity, and/or surrounded by a mandorla, became increasingly frequent. This was presumably a reference to the Woman of the Apocalypse, who was exegetically identified with the Virgin and became a key allegory for the Virgin’s involvement in man’s salvation.46

Corblet had suggested that representations of the tree growing out of Jesse’s body may have been designed to provide an analogy with Adam, who lay asleep on the ground while God created Eve from one of his ribs. The Virgin on the Tree of Jesse was seen by Corblet as the Second Eve, who has been sent to redeem the first. Watson, however, believed another analogy was closer, that the Tree of Jesse, like the Tree of the Cross, was a tree of salvation.47 This argument appears logical; consequently, it seems likely that the Tree of Jesse can be seen as part of a much wider tradition in Christian art, alongside the Tree of Knowledge, the Tree of Life, the vine and the physical tree from which the True Cross was made, all of which allude to a general concept of salvation.48 As Watson identified, the virga Jesse and virga Crucis were brought into close association at an early date in the writings of Peter Damian, the eleventh-century monastic leader and church reformer whose works were widely distributed and remained popular for many generations.49 Damian followed his homily, In nativitate Beatissimae Virginis Mariae, with the De exaltatione Sanctae Crucis. Introducing this, he wrote, ‘Out of the virga of Jesse we came to the virgam of the cross and the beginning of redemption was the conclusion’.50 Damian, therefore, saw the Tree of Jesse as the beginning of the story of salvation, which led to man’s redemption through the Tree of the Cross. The placing of a Cross on the altar in front of an image of the Tree of Jesse would provide a similar association of ideas. In the early sixteenth century, many Antwerp carved altarpieces and Breton windows actually combined the Tree of Jesse with the Crucifixion in a single work, highlighting the humanity of Christ and adding a Eucharistic dimension to the motif. These images, which provide a complete visual rendition of the story of salvation, are examined in further detail in Chapters Five and Six. Some pictorial representations link the Tree of Jesse with other religious trees, for example, the Saint-Omer Psalter of c.1330–40 in the British Library (Yates Thompson 14 fol.7r), depicts a historiated Beatus initial with a Tree of Jesse and historiated border containing nine roundels that include the Tree of Knowledge. Obvious parallels also exist with the Tree of Consanguinity or the Lignum Vitae of Saint Bonaventure.

Certain scholars have associated renewed interest in the Tree of Jesse in the fifteenth century with the belief in the concept of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin. The first to propose this was Mâle, who briefly examined the reappearance of the iconography in French stained glass and printed Books of Hours between 1450 and 1550.51 He suggested that its use at this time was primarily because the motif had become some kind of symbol of the concept. Belief in the Immaculate Conception was a subject of great controversy among theologians during the fifteenth century, and although it did not become a dogma of the church until the nineteenth century, it was widely supported by many influential religious orders, particularly the Franciscans, Carmelites and Benedictines. The theory that the Tree of Jesse had become an expression of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin was discussed in more detail by D’Ancona.52 D’Ancona supported Mâle’s premise, but also allowed for the use of the motif by those opposed to the concept. D’Ancona differentiated between the Immacu-list tree, which she believed referred specifically to Mary, and the Maculist tree, which she believed referred specifically to Christ. This hypothesis will be discussed further in Chapter Two.

The brief study conducted by Böcher in 1973 also identified that the Tree of Jesse had become particularly fashionable again in Germany from the 1460s, particularly along the Rhine.53 Yet Böcher does not single out the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin as the motivation for this renewed use, but relates it more to a wider interest in the matrilineal genealogy of Christ. Böcher is supported by more recent studies that focus on Saint Anne, such as those by Kathleen Ashley and Pamela Sheingorn, Virginia Nixon and Jennifer Welsh, which associate the late medieval use of the Tree of Jesse with the rapid expansion of the cult of the Virgin’s mother in Germany and the Low Countries.54 Although the examination of the iconography in these texts is cursory and restricted to few examples, all agree that images of the Holy Kinship and Tree of Jesse became popular during the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries to convey the various familial relationships described in the apocryphal Protoevangelium of Saint James, the Pseudo Matthew and the Golden Legend, Jacobus de Voragine’s widely read anthology of the saints’ lives.

This argument appears to be corroborated by the surveys undertaken by Esser and Lepape, who give many examples that illustrate the renewed interest in both Holy Kinship and Tree of Jesse iconography that occurred in Germany, the Netherlands, and parts of northern France, from c.1450 to c.1550.55 However, as neither author considers individual works in any depth, they are unable to shed further light on exactly how the iconography might have functioned in relation to patronage and location. This book will attempt to fill the gap in the existing literature, and address some of the previous assumptions made about the late medieval use of Tree of Jesse iconography.