Simple codes and ciphers can be created with pencil, paper and patience. This chapter describes various examples of simple codes, which, while being quite basic in formulation, are in fact a very effective method of concealing meaning, and have been used by secret agents and spies many times.

Perhaps the simplest way of concealing a written message is a space code, in which the plaintext is broken up into different ‘words’. For example ‘This is an example of a space code’ could be encoded as THI SISA NEXAM PLEO FAS PAC ECO DE. It wouldn’t fool anyone for long, though. Neither will a backwards code: EDOC SDRAWKCAB A LLIW REHTIEN. This message can be made slightly less recognizable by breaking up the word groups: EDO CSD RAWK CAB ALL IWREH TIEN.

A ‘code’ is a system in which words and/or phrases are changed, and therefore requires a code book, which is like a dictionary. In a ‘cipher’, the substitution is of letters, so no code book is necessary, and deciphering requires knowledge of how the letters have been changed. An advantage of ciphers is that the same letter can be changed to many different letters or numbers, making it much harder to detect (see page). Turning a message into code and then enciphering that text is called ‘superencipherment’.

A history book written in 14th-century Egypt notes that tax and army officials used the names of perfumes, fruits, birds and flowers to denote certain letters or terms. This kind of code is pretty much unbreakable, but there are difficulties in execution:

• All correspondents need a copy of the code words in use, and this document will be bulky and hard to conceal.

• Anyone able to see this code book can understand your messages. You would also probably need to expand the code book to allow you to use a wide vocabulary, so there would be security issues about this valuable document.

• If someone studies your conversation or writing, they will be able to make informed guesses about the types of words in the gaps (verbs, nouns, numbers, etc.) and eventually decipher at least parts of it, simply from the context.

• However, it is very easy to create a code allowing you to talk or write to a friend with no chance of others understanding your communication. All you have to do is agree to change each important word for another word, rendering the plaintext incomprehensible.

TRANSPOSITION CIPHERS

• A cipher in which letters are rearranged, as in the backwards cipher on page 53, is known as a transposition cipher.

• Other examples in this chapter are the rail fence cipher on pages 64–5 and the Greek scytale (see pages).

• Transposition ciphers are easy to spot if you analyze the letter frequency (see pages).

Codes where words stand for other words or phrases are known as sub rosa codes. A famous story involving their use comes from World War I, when censors who were suspicious of the cable message ‘Father is dead’ amended it to ‘Father is deceased’. This caused confusion with the recipient, who cabled back, ‘Is father dead or deceased?’

The practice was also widespread among spies in World War II. A series of intercepted letters contained detailed concerns apparently about the correspondent’s doll collection such as, ‘A broken doll in a hula grass skirt will have all damages repaired by the first week of February.’ It was eventually established that each doll was code for a different American ship.

One way to avoid having to create and update a code book is to use a dictionary code for all, or some, words. This has proved a popular method for secret agents countless times. When you wish to disguise a word, you quote the page, column and entry number where it appears in your dictionary: you just have to make sure both parties are using the same edition of the tome. For example, in the tenth edition of Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, the word ‘dictionary’ is on page 322, column 1, and is the third entry, so its code number is 322,1,3. The comma is required to avoid confusion between the three pieces of information: for example 32213 could mean page 32, column 2, entry 13, which is ‘allow’. The number for ‘code’ is 221,2,17.

Thus the plaintext, ‘This sentence is in dictionary code’ would be encoded as:

‘THIS SENTENCE IS IN 322,1,3 221,2,17’ if you just change two key words, or if you change them all:

1227,1,14 1067,1,13 620,2,11 585,2,6 322,1,3 221,2,17

Anyone trying to decode this message would immediately know how many words it contained by counting the spaces between numbers. The use of three numbers for each word also betrays the ‘page, column, entry’ format, especially as the middle number is always 1 or 2. So you would quickly discern that it is a dictionary code, but would be unable to proceed further without identifying which dictionary was used.

Armed with this knowledge, you might decide to conceal the page numbers by making every page number four digits, leaving the column number untouched, but making all the entry numbers two digits, filling in gaps with zeroes. Now you can run all the numbers together and remove the commas:

122711410671130620211058520603221030221217

CODES IN BOOKS

• Jules Verne’s Voyage to the Centre of the Earth features a baffling code that turns out to be Latin written in reverse that can be read through the back of the paper.

• William Makepeace Thackeray included a Cardano grille (see pages) in The History of Henry Esmond.

• H. Rider Haggard used a cipher in Colonel Quaritch, QV.

• Agatha Christie used a flower-names code in The Four Suspects, solved by the indomitable Miss Marple.

• Mystery writer Dorothy L. Sayers used a message in Playfair cipher (see pages) as a fundamental part of the plot in her Lord Peter Wimsey novel, Have His Carcass. He solves it by guessing that the message starts with the name of a city and then a year, providing him with a crib.

Another refinement is to use any odd number instead of ‘1’ to indicate the entry is in the left-hand column, and any even number in place of ‘2’ for the right-hand column. This will confuse the decoder. Yet another trick is to add the same number to every figure. For example, adding five to each figure in the code above would produce this ciphertext:

123261910726180625716059071103276080226722

A determined decoder will still be able to recognize number patterns, although you can further confound them by changing the procedure slightly and locating the words in the same position but four pages in front of the word in the plaintext. Now your message reads:

THERAPEUTICS SEMESTER INVESTITURE IMPATIENCE DEWAR CLOVE

The ‘four pages back in the dictionary’ code is exactly the method unearthed in the scandal surrounding the disputed 1876 American Presidential election in which both Democrats and Republicans were suspected of malpractice. In one Democrat message, the phrase, MINUTELY PREVIOUSLY READMIT DOLTISH, translates as, ‘Must purchase Republican elector’, via the Household English Dictionary published in 1876.

Any book can function as a code book in much the same way as a dictionary, and this again, for centuries, has been a very common encoding method. One problem, though, is in finding the words in the book in the first place. For example, a message using this system from Benedict Arnold, the 18th-century American general who defected to the British, found him culling words from pages as far apart as 35, 91 and 101. That’s a lot of searching for one word – it would be infinitely easier today using the search facility on a word-processing program.

The disadvantage of using a dictionary or book for creating a code is that many words, such as place names, simply won’t be in the text and will then need to be laboriously spelled out letter by letter, with the code specifying the page, line, word and letter numbers. This will create a very long message, which occupies hours for both encoder and decoder. However, provided the interceptor never identifies the book used, it is a very secure method, especially if the book is changed frequently, which explains its popularity. Another benefit is that the shelves of secret agents will not be stacked with incriminating code books or stencils, but merely hold a stock of seemingly innocent books.

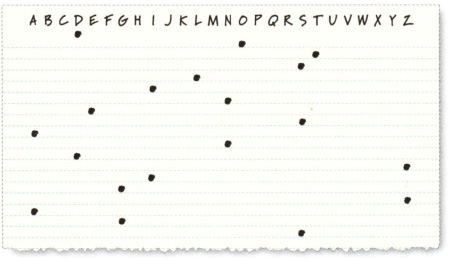

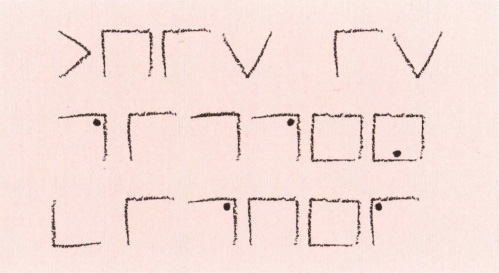

This is totally different to the practice of dotting or pinpricking newspapers favoured by thrifty Victorians (see page). The alphabet is written on squared paper with one letter on each line and the receiver needs an exact copy. The ciphertext is created by putting a dot under each letter in your message, working down the page so that each new dot is on a new line. The end result looks like piano roll music for an automatic piano. So the message, ‘Dots lines and zigzags’ will look like the illustration below. The alphabet can also be written vertically rather than horizontally, in which case the dots will read from left to right.

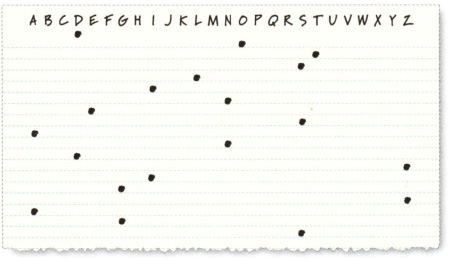

You can disguise the message by connecting the dots to make lines, a graph or even a crazy picture, or go in sequence to create a zigzag pattern as you can see in the illustrations below. The dots from which these variations are produced must be positioned precisely to avoid confusion in decoding.

The dot cipher.

A refinement of this system is to set the alphabet in a different, pre-arranged order, such as backwards or with all the vowels first.

The line and zigzag ciphers.

In transposition ciphers, letters are rearranged in a different order, creating an anagram of the message. There are various systems determining how to change the position of the letters to form a cipher.

The scytale is the earliest known piece of cryptographic equipment, dating from 5th-century BC Greece. Probably first used by the Spartans to carry messages around the battlefield, it is a simple transposition machine. A piece of parchment rather like a ribbon was wrapped around a cylinder, such as a wooden staff. The message was then written unencrypted onto the coiled paper.

Once removed from the rod, the writing was just a jumble of letters that would be meaningless if the enemy captured it. It is possible that messengers wore the fabric as a belt with the writing on the inside. When the message was delivered, it was wrapped around a cylinder identical in diameter to the first one, and could be read.

A CONE TO DECODE

A scytale message can be decoded by simply wrapping the material around a cone and sliding it around until the text makes sense.

Part of the scytale’s value was the speed at which communication took place, because no enciphering and deciphering was involved: the message was written, transported with reasonable security, and read.

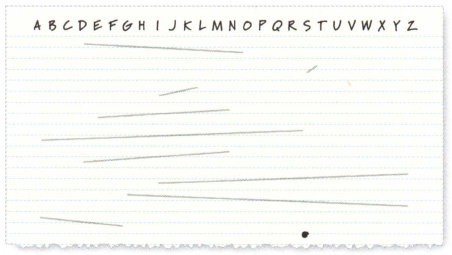

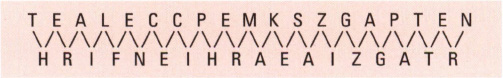

In the 19th century, hundreds of miles of fencing was put up across the US as new territories were taken over. Known as split-rail fences, they form a zigzag pattern when seen from above, similar to the pattern made by letters in the rail fence cipher. If you write the message, ‘The rail fence cipher makes a zigzag pattern’ in zigzags, it looks like this:

The enciphered message is created by writing each row, choosing, if you wish, to put the letters into groups of four, in which case you will need to fill in the gaps with ‘padding letters’ or ‘nulls’, which are usually X or Z. The first null indicates where the new line starts. In this example, the last two nulls ensure the ciphertext ends with a group of four letters.

TEAL ECCP EMKS ZGAP TENX HRIF NEIH RAEA IZGA TRZZ

To decipher this message, count the letters (40) then divide into two groups. You can now put the letters into order by writing the first letter from each group, then the second, and so on, ignoring the nulls, and reading the words created.

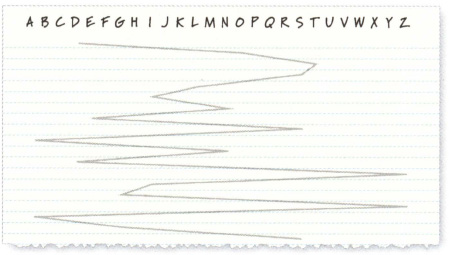

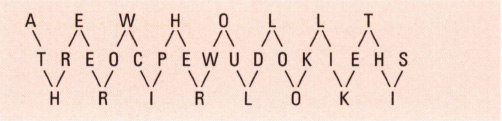

The cipher can be written in three or more rows, either zigzagging across the page or starting a new column every three letters. This is the code written in zigzag pattern for ‘A three row cipher would look like this’:

This creates the code message AEWH OLLT TREO CPEW UDOK IEHS HRIR LOKI

INTENSIVE CARE

Transposition ciphers require a lot of laborious work to prepare, and there is plenty of scope for mistakes, so they have not been used as widely as some other ciphers in the past. However, they are effective and the concept lies behind many modern computer-driven cipher algorithms.

ADDING NULLS

When adding nulls to pad out a grid, the number of letters added can be indicated by the final letter’s position in the alphabet. So, a one-letter null would be an A, and if four letters were added, the last one would be D.

The message can be revealed by writing out the eight letters of the top row, the 16 in pairs of the middle row, and the eight of the bottom row, recreating the zigzag pattern of the original. Then the letters are written out in the new order reading down and up.

Like other transposition ciphers, the cipher features letter frequencies similar to those of the language in everyday use (see pages), so you can identify them by counting letter frequency. Now you need to unscramble the letters on the page, which is much easier than finding substitutes for them.

To decipher a transposition cipher you need to identify then ignore the padding nulls – frequency analysis (see pages) will help here – then try reading every second letter, and if that doesn’t work, every third letter, and so on. The longer the message, the bigger the jumps will have to be.

Once the letters are put into a four-column grid, they do not have to be enciphered in the standard left to right, or top to bottom order. For example, your key could be to start at the bottom right corner and spiral clockwise to the centre. This is called a route cipher and makes decryption much more difficult. The encryption of the same four-row message already used :

T |

I |

I |

N |

O |

H |

S |

T |

I |

W |

I |

W |

T |

N |

S |

S |

R |

E |

R |

A |

would then begin at the A in the bottom right corner and read as:

ARERS IHTII NOWSN TWSTI

Other paths for enciphering include:

• In a spiral from the centre.

• Diagonally (specifying upwards or downwards, left to right, or right to left).

• Up one column, down the next.

Another way to scramble the letters from a grid is to identify the columns with a key word or number. This is called columnar transposition. If you have a four-column grid with the message, This makes it more complicated’ written across, it looks like this:

T |

H |

I |

S |

M |

A |

K |

E |

S |

I |

T |

M |

O |

R |

E |

C |

O |

M |

P |

L |

I |

C |

A |

I |

E |

D |

T |

B |

Two nulls have been added, the last being B to indicate ‘two nulls’. Making the other nulla T rather than, say, an X makes them harder to spot as imposters.

THE KEY

The encipherer and decipherer agree in advance how many rows the ‘fence’ will have, and, if necessary, the direction of writing (e.g. forwards, backwards and whether using diagonals or columns). This information is called the key and allows the message to be rapidly deciphered.

Instead of writing the encryption out by following the column order, you can change it with the four-letter keyword CODE (one letter for each column). In alphabetical order within the word, these letters are 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th. This would re-arrange the grid to read:

C |

0 |

D |

E |

1st |

4th |

2nd |

3rd |

T |

S |

H |

I |

M |

E |

A |

K |

S |

M |

I |

T |

0 |

C |

R |

E |

0 |

L |

M |

P |

I |

T |

C |

A |

E |

B |

D |

T |

In blocks of five (with a three on the end, which could be filled with nulls if you choose), the enciphered message now reads:

TSHIM EAKSM ITOCR EOLMP ITCAE BDT

The decipherer now works out the column lengths by dividing the key length (four, from the keyword CODE) into the message length (28 letters). This reveals the number of rows as seven, so the content of each column can be identified, then re-ordered according to the code word, the nulls counted and removed, and the message read.

BOOK CODES IN THE MOVIES

Book, and especially Bible, codes are popular in Hollywood movies.

• In the 1996 film Mission: Impossible there are several references to Job 3:14: ‘with kings and their advisors whose palaces lie in ruins’.

• The 2002 thriller Red Dragon features numerous apparent Bible citations, which turn out to refer to a different book, The Joy of Cooking. This may be less of a surprise when you consider the film is a sequel to the cannibalistic The Silence of the Lambs (1991).

• National Treasure (2004) has a plot based around a code hidden in the US Constitution revealing the whereabouts of a treasure buried during the 1700s.

A technique for breaking down transposition ciphers is to guess the number of rows, group letters accordingly, then slide the letters around looking for words or anagrams. Double transposition counteracts this by repeating the scrambling of columns during encryption, usually with a second keyword. Both keywords can be changed at will to protect the cipher from attack.

Double transposition was used by the German Army during World War I, but it was successfully broken by the French. They were greatly aided by the fact that the Germans, confident of the security of their cipher, used the same key for more than a week at a time – a major sin in the world of cryptography (see pages). Double transposition was widely used in World War II as well, as it was regarded as the most complex cipher an agent could use as a field cipher.

Transposition ciphers create anagrams of the plaintext by mixing up the words or letters. Substitution ciphers leave the letters in the order they should be read, but disguise them.

An early example of this comes from 2,000 years ago in a message sent by Roman leader Julius Caesar to Cicero, whose forces were under siege. The Roman letters were substituted with Greek letters, which Caesar knew Cicero would understand.

MONO TO POLY

• A Substitution cipher that uses one alphabet for encryption so that each plaintext letter is represented by the same ciphertext letter throughout is described as ‘monoalphabetic’.

• Later ciphers that used more than one alphabet are known as polyalphabetic ciphers (see pages).

Caesar had many reasons to encrypt his messages and did so in many ways. The most famous is the shift cipher, in which each letter is replaced by the letter three places on in the alphabet: ‘a’ becomes D, ‘b’ becomes E, ‘c’ is F and so on. The message, ‘Named after Julius Caesar’ would be written as:

QDPHG DIWHU MXOLXV FDHVDU

The Caesar shift was widely used for centuries – it was even one of the ciphers being used by Russian forces in 1915. A big advantage of the shift cipher is that it does not require a code book as the method can be easily memorized. It can also be adapted to shift the letters any number of places from 1 to 25 for a standard 26-letter alphabet through the use of a code number. This is called the St Cyr cipher, after the French national military academy where it was taught in the 1880s.

However, it is also known as the slide rule cipher because it can be created by sliding an alphabet strip below an identical strip to create the shifted letters. So the code number 7 would indicate a 7-place shift, creating this alphabet:

Plain alphabet: |

a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z |

Cipher alphabet: |

H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A B C D E F G |

However, the fact that the cipher is in alphabetical order makes this kind of shift key very easy to break. All you have to do is take one word or set of letters and try out all the possible encryption keys. For example, if the cipher text includes the letters SIFBVE, the word can be discovered through the process shown in this table:

Shift |

Produces letters |

0 |

SIFBVE |

1 |

TJGCWF |

2 |

UKHDXG |

3 |

VLIEYH |

4 |

WMJFZI |

5 |

XNKGAJ |

6 |

YOLHBK |

7 |

ZPMICL |

8 |

AQNJDM |

9 |

BROKEN |

So shifting the encrypted message nine places along the alphabet solves the cipher.

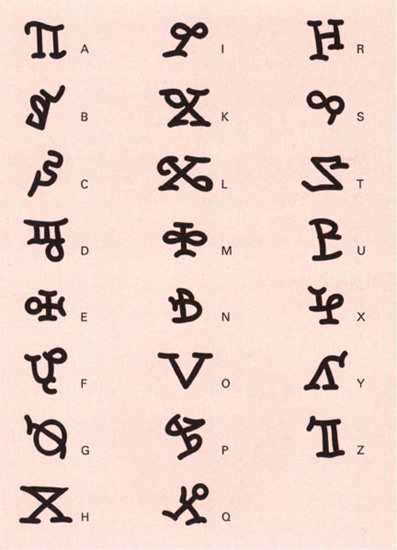

THE SHADOW

The Shadow magazine published serialized stories for 18 years from 1931, and remains a cult publication. The tales of the mysterious sleuth, written by newspaperman and magician Walter B. Gibson under the pen name Maxwell Grant, featured various codes in various ways. One story, ‘Chain of Death’, features an inventive alphabet, and is illustrated below.

So far this is just a graphically pleasing substitution alphabet, but the cipher was later refined with an additional four symbols:

![]()

Each symbol indicates a degree of rotation, adding three levels of transposition to the alphabet. For example, a quarter turn shown by symbol 2 transforms the character for ‘a’ into that of B, and ‘c’ becomes D.

The Shadow was brought to life in a radio serial in the 1930s, a period when public interest in secret codes was high. Secret decoders were popular toys and promotional gifts from the 1930s onwards, especially from manufacturers of children’s drinks and cereals. The ‘Captain Midnight’ radio serial in the 1930s and 1940s included secret codes giving clues about the next episode and listeners could send in for a working cipher disc as part of a ‘Spy-Detector Writer’ kit, which could be used to decrypt messages broadcast in the show.

EARLY SUBSTITUTION

A 10th-century Persian substitution alphabet used the names of birds for letters of the alphabet. Another substituted them with names for parts of the night sky.

Another approach is to start the alphabet with a key word, followed by the remaining letters in alphabetical order. This allows regular changing of the cipher by replacing the keyword and enhances security of the system. Repeated letters in a code word are omitted (so omitted would be spelt with one ‘t’ as omited). Here the keyword is ‘scramble’:

Plain alphabet: |

a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z |

Cipher alphabet: |

S C R A M B L E D F G H I J K N O P Q T U V W X Y Z |

Notice that some letters stay the same in this cipher, a feature best avoided. There are a couple of ways of getting around this. The cipher alphabet can follow the keyword in any agreed order, so one with the keyword ‘backwards’, followed by the rest of the alphabet in reverse, would look like this:

Plain alphabet: |

a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z |

Cipher alphabet: |

B A C K W R D S Z Y X V U T Q P O N M L J I H G F E |

Alternatively, the keyword need not come at the beginning of the alphabet. So if the keyword is ‘thirteen’ and happens to start on the 13th letter of the alphabet, you would produce this cipher alphabet:

Plain alphabet: |

a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z |

Cipher alphabet: |

L M O P Q S U V W X Y Z T H I R E N A B C D F G J K |

Since one weakness of these substitution ciphers is their alphabetical order, the way to protect them is to put the alphabet into a different, random order. Theoretically this creates 403,291,461,126,605,635,584,000,000 different possible cipher alphabets – more than someone could test in a lifetime, even if they were equipped with a computer.

However, because the cipher alphabet is random, it would have to be memorized by two people (which is unreliable) or written down (which threatens cipher security). It is also, as we will see later, easily broken by frequency analysis.

The typewriter cipher substitutes the alphabet for the letters of the keyboard in order from top to bottom (the qwerty keyboard is a random order for which there seems to be no explanation – it certainly doesn’t reflect frequency of use for its letters. However, have you noticed that the characters of ‘typewriter’ are all on the top row of letters?).

Plain alphabet: |

a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z |

Cipher alphabet: |

Q W E R T Y U I O P A S D F G H J K L Z X C V B N M |

Alternatives are for each key to represent, say, the one to its left, with the cipher wrapping round to the beginning when the end of the row is reached, or to the left and above, so that ‘typewriter cipher’ would be enciphered as:

5603248534 D80Y34

A cipher with an alphabetical basis can be attacked fairly easily by cryptanalysts because there will be a pattern to at least parts of the cipher for the letters not in the keyword. One option is to re-order the alphabet, for example by writing it backwards:

Plain alphabet: |

a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z |

Cipher alphabet: |

Z Y X W V U T S R Q P O N M L K J I H G F E D C B A |

This produces one of the most famous (and simplest) ciphers in history, Atbash, a cipher in which the first letter becomes the last, the second becomes the second last, reversing the alphabetical order. This was a device used by Hebrew scribes to encipher parts of the Old Testament. ATBASH is so-called because in the cipher the Hebrew letter A becomes T, B becomes Sh, and so on, hence ATBSh, which is pronounced ATBASH. It is remarkably easy to break because there is only one solution!

Another option is to write all the vowels first, followed by the consonants:

Plain alphabet: |

a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z |

Cipher alphabet: |

A E I O U B C D F G H J K L M N P Q R S T V W X Y Z |

Again, to prevent letters being encrypted as themselves, do this backwards:

Plain alphabet: |

a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z |

Cipher alphabet: |

Z Y X W V T S R Q P N M L K J H G F D C B U O I E A |

If the cipher alphabet is not alphabetical at all, it is harder to break. However, both parties must remember, or keep a record of, the invented alphabet, which can weaken security.

Encrypting a word message into a number cipher is another way to disguise meaning. The most obvious way is to number the alphabet (‘a’ = 1, ‘b’ = 2, etc.), but this will be simple to detect (see frequency analysis, pages 89–95). All the variations in alphabet order described on pages 71–9 could be adapted to create a number rather than a letter alphabet.

Another way, which has more possibilities for deception, is a five-by-five grid, giving 25 squares. As there are 26 letters in the alphabet, this requires two to be combined: ‘i’ and ‘j’ will do. The grid looks like this:

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

1 |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

2 |

F |

G |

H |

I/J |

K |

3 |

L |

M |

N |

O |

P |

4 |

Q |

R |

S |

T |

U |

5 |

V |

W |

X |

Y |

Z |

Letters can now have a number created from their grid reference with the horizontal row number appearing first then the vertical column, so ‘b’ would be 12 and ‘s’ would be 43. Thus the plaintext ‘number cipher’ would be encrypted as:

33-45-32-12-15-42 13-24-35-23-15-42

The alphabet can be written in any agreed order in the grid, perhaps using a keyword, and decryption is a simple matter of matching letters to their numbers. One disadvantage of this system is that the ciphertext is twice the length of the plaintext, and writing out the enciphered message is double the work.

NO ROOM FOR ERROR

Whenever you are encoding, it is crucial to avoid making any mistakes, as these will confuse the recipient of the message. This is especially true when using numbers. Inputting the wrong number or, worse, omitting a digit, will render the message incomprehensible.

The numbering method on such a grid is known as the Greek square, or the Polybius square, after its inventor. Dating back 2,200 years to ancient Greece, it was used to send messages long distances by holding up torches, with the number held in each hand indicating the grid reference. There are records of a similar method being used in 16th-century Armenia to add a sense of mystery to religious texts.

The system lends itself to communication with lamps, smoke signals, knots or stitches in string or quilts, and sounds. Translated into a system of knocks, it is a method for messaging between prison cells. It is said to have been used in this way by captives of the Russian Tsars, and by American prisoners of war during the Vietnam War.

Since each letter is matched by one number, this cipher can be broken by frequency analysis (see pages), just like any other monoalphabetic substitution cipher. However, there are possibilities for making it more complex, which are explored on pages 97–100.

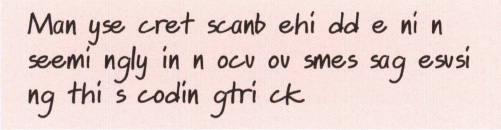

One cipher cunningly conceals its use of the Polybius square in cursive handwriting. The number of characters between each break where the pen is removed creates a numeric code. Apparently this method was also used in letters home from captured German U-boat officers during World War II. Using the ciphertext given on page 80:

33-45-32-12-15-42 13-24-35-23-15-42

The message – in this case, ‘Many secrets can be hidden in seemingly innocuous messages using this coding trick’ – would be written as follows:

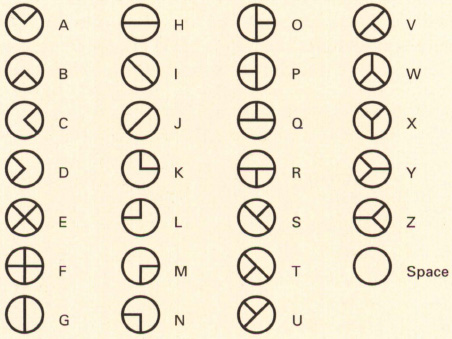

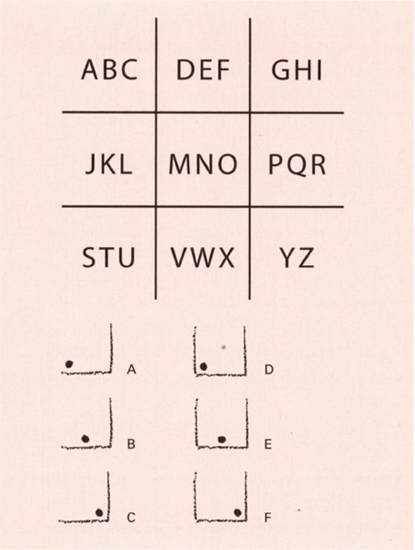

A different approach to substitution ciphers is to use an alternative alphabet consisting wholly or partly of symbols. This has been done many times in history. The earliest record of it is an ancient Greek practice of using dots for vowels (one for alpha, two for epsilon, and so on), with the consonants left unchanged.

An example of this is the King Charlemagne cipher dating from the 8th century and used in his battle reports. It was a 23-letter symbolic alphabet (there was no ‘j’, ‘v’ or ‘w’ at the time), which recipients of his messages were required to learn.

The King Charlemagne symbol alphabet code.

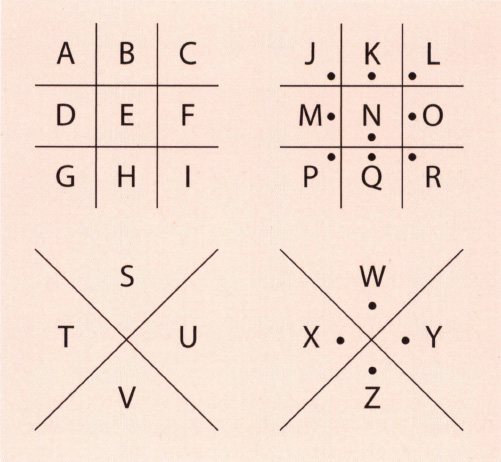

The pigpen cipher – see page for an example of it in use.

This is an alternative alphabet that was widely used by masons in the 18th century (it is also known as the Freemason cipher), although some put its origins centuries earlier, during the Crusades. The letters of the alphabet are written inside a grid (which looks like an animal pen, hence the name) (see diagrams above).

Each letter is represented by the graphic symbol from its part of the grid, with dots added to allow each symbol to be used for two different letters. So ‘This is pigpen cipher’ would look like this:

Pigpen cipher was used by Confederate forces during the American Civil War, possibly because, apparently, many of the generals were Freemasons and so were familiar with the system. It was solved by a former shop worker who recognized the symbols because the same system had been used to mark the prices of goods in the shop in which he had worked before the war!

A variant of the pigpen cipher (also based on a grid), but with the same shape now representing one of three letters, which are identified by placing a dot on the left, centre or right, is known as the Rosicrucian cipher.

The Rosicrucian cipher and an example of it in use.

When Mary, Queen of Scots was being held at Chartley Hall in Staffordshire in 1586, she knew that letters in and out would be studied for indications of any plot against her half-sister Queen Elizabeth I. Consequently, when she wanted to correspond with a Catholic sympathizer, she took precautions:

• Letters were smuggled in and out hidden in the bung hole of a beer keg.

• She wrote using 23 letter substitutions and 36 code signs for words and phrases. This blend of code words and cipher is known as a nomenclator.

• She avoided direct references to plots to kill the queen and put her (Mary) on the throne.

Mary was confident that these precautions prevented her being accused of treason. She did not know that:

• Her correspondent, Gilbert Clifford, was a double agent.

• Even the brewer who supplied the beer kegs was in the pay of English spymaster Francis Walsingham.

• Her letters were routinely opened and copied for analysis.

• Once Mary’s nomenclator was broken, Walsingham was browsing through her post even before her servants had sneaked incoming letters past the guards at Chartley Hall.

Such was Walsingham’s grasp of the intricacies of Mary’s code system that he even had extra writing forged onto one of her own letters to try to elicit incriminating information. Although she denied all at her trial, Mary’s letters showed she knew and approved of a plot against Elizabeth. It was enough for her to be executed.

The queen’s spymaster had set up a cipher school in London, where Mary’s code was broken. The method relied on a revolutionary new weapon in western cryptanalysis: frequency analysis.

Frequency analysis is the deadly weapon that breaks substitution and transposition ciphers. It was first developed in the 9th century by an Arab religious scholar called Al-Kindi, who was studying sacred texts of previous civilizations. He realized that in any language some letters are used far more often than others, that some only appear rarely, and that this pattern remains consistent.

Therefore, in a substitution cipher, the most commonly occurring ciphertext letters are likely to represent the most common letters in the plaintext language. This allows cryptanalysts to make informed guesses about the identity of individual letters following statistical analysis of both the plaintext language and the ciphertext.

Furthermore, once a common letter is known, its position in a word helps identify its partners. For example, once ‘e’ is identified, any three-letter words with which it ends are very likely to be ‘the’, so identifying ‘t’ and ‘h’.

ELEMENTARY, MY DEAR WATSON

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s famous fictional detective Sherlock Holmes applied his deductive powers (usually studying letter frequency) to several codes, including:

• A message concealed as every third word in The ‘Gloria Scott’.

• A book code created by arch foe Moriarty using Whitaker’s Almanac in The Valley of Fear.

• An unusual cipher using stick men symbols in Adventure of the Dancing Men. There are 26 of them, so each represents a letter of the alphabet (see the illustration below, which spells out ‘Am here Abe Slaney’).

• In the English language, about one in every eight letters is likely to be an ‘e’. So, if about one-eighth of the letters in a ciphertext are Y, it is likely to be an ‘e’ in plaintext.

• The vowels, a, e, i, o and u, and the part-time vowel ‘y’, make up about 40 per cent of English text.

• The least common letters are k, j, q, x and z, which, between them, account for just over one per cent of English letters used.

In order of frequency, the English alphabet reads:

• e, t, a, o, n, r, i, s, h, 1, d, c, u, f, p, m, w, y, b, g, v, k, x, q, j, z.

• Counting the letters in the plaintext, if the six most common letters are the first six listed here, and there are very few of the final letters listed, the cipher is likely to be a giant anagram created by transposition.

• By similar logic, if the most frequently occurring letters in the ciphertext are those that only appear rarely in natural text, the cipher is likely to be of the substitution variety.

MORSE SENSE

The dots and dashes used in Morse code were decided according to frequency analysis, with the most commonly used letters requiring the least effort to transmit (see pages).

The next step is to look for short words. Only ‘A’ and ‘I’ are one-letter words, but there are many more of two, three and four letters. If you can identify word lengths, either because they are not disguised or by identifying the spacer null letter, you can guess what they are most likely to be according to their natural frequency of use and the context (some words are unlikely to follow others, or to start or end sentences). It is worth bearing in mind, however, that code messages do not always follow the rules of sense and grammar. Ciphertext may be shortened to save effort in translating and transmission, and may include code words that are short for phrases or sensitive information.

However, frequency tables are gold dust for a cryptanalyst. For example, it is much easier to make informed guesses about the ends of words when armed with the information that more than half of all words end with e, s, t or d. Similarly, if two letters in a transposition ciphertext are the same, they are most likely to be (in order): ss, ee, tt, ff, ll, mm, oo. Two letters in a substitution ciphertext may or may not be the same.

The brain is a powerful tool and is very good at filling in gaps. For example:

-ou a-e –roba-ly ab-e t- rea- t-is te— e-en tho—- a -ot — it i- m—si-g!

This shows how finding some letters, even in a shifting substitution text, can allow you to identify new information.

A digraph is two letters that together make a single sound. These are common in English, which helps in cryptanalysis because identifying one letter leads us towards the other. In order of frequency they are:

• th, he, an, in, er, on, re, ed, nd, ha, at, en, es, of, nt, ea, ti, to, io, le, is, ou, ar, as, de, rt, ve.

Trigraphs are parts of words formed by three letters. Their order of frequency is:

• the, and, tha, ent, ion, tio, for, nde, has, nce, tis, oft, men.

Double value |

Triple knowledge |

Four-letter words |

|||

The most common two-letter words in English are: |

The most common three-letter words in English are: |

The most common four-letter words in English are: |

|||

1 |

of |

1 |

the |

1 |

that |

2 |

to |

2 |

and |

2 |

with |

3 |

in |

3 |

for |

3 |

have |

4 |

it |

4 |

are |

4 |

this |

5 |

is |

5 |

but |

5 |

will |

6 |

be |

6 |

not |

6 |

your |

7 |

as |

7 |

had |

7 |

from |

8 |

at |

8 |

her |

8 |

they |

9 |

so |

9 |

was |

9 |

know |

10 |

we |

10 |

one |

10 |

want |

11 |

he |

11 |

our |

11 |

been |

12 |

by |

12 |

out |

12 |

good |

13 |

or |

13 |

you |

13 |

much |

14 |

on |

14 |

all |

14 |

some |

15 |

do |

15 |

any |

15 |

time |

16 |

if |

16 |

can |

16 |

very |

17 |

me |

17 |

day |

17 |

when |

18 |

my |

18 |

get |

18 |

come |

19 |

up |

19 |

has |

19 |

here |

20 |

an |

20 |

him |

20 |

just |

Word breaks are valuable to a cryptanalyst because they can gain clues using the following information:

• Most common first letter in a word, in order:

t, o, a, w, b, c, d, s, f, m, r, h, i, y, e, g, 1, n, o, u, j, k.

• Most common third letter in a word, in order:

e, s, a, r, n, i.

• Most common last letter in a word, in order:

e, s, t, d, n, r, y, f, 1, o, g, h, a, k, m, p, u, w.

• Letters most likely to follow the letter ‘e’:

r, s, n, d.

Zipf’s law identifies the most common words and in what proportion of text they will appear. Named after Harvard linguist George Kingsley Zipf, it shows that seven per cent of all words are ‘the’, followed by ‘of’ at about half that frequency, then ‘and’. Cryptanalysts can apply this law to make informed guesses about words in context.

CODED SCULPTURE

Just outside the Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA’s) headquarters in Langley, Virginia, is ‘Kryptos’, a 12-foot-high copper, granite and petrified wood sculpture that has baffled staff and other cryptologists since its installation in 1990. Sculptor James Sanborn, an ex-CIA worker, inscribed it with some 1,800 letters forming four messages, each in a different cipher.

Three of the ciphers have been broken using frequency analysis and a Vigènere square (see pages). They reveal a set of coordinates, possibly of a nearby location where Sanborn has buried something. The fourth passage retains its secrets.

After ‘Kryptos’, Sanborn created other coded sculptures, including ‘The Cyrillic Projector’, a cylindrical installation at the University of North Carolina, which contains text from classified Russian KGB documents in Cyrillic alphabet.