Capital and Exploitation

In the previous chapter, it was shown that the production of use values as commodities, which is typical of capitalism, tends to conceal the social relations of production as a relationship between producers. This type of production focuses attention instead on exchange as a relationship between things. Nevertheless, as simple commodity production demonstrates logically and a history of trade demonstrates in reality, exchange itself can and does exist without capitalism. It is only when labour power becomes a commodity and wage workers are regularly hired to produce commodities for sale at a profit that capitalism becomes the mode of production typical of a given society. In this chapter, by examining exchange from the perspective first of the workers and then of the capitalists, it will be seen why capitalism is not merely a system of commodity production, but is also, more crucially, a system of wage labour.

Beyond simple bartering, which is a very limited historical phenomenon, money is essential to exchange. The functions of money have been well explored in the literature: it is a measure of value, a standard of prices (i.e. a unit of account), a means of circulation, and a store of value. As a means of circulation, it mediates the process of exchange. When commodities are bought on credit and debt is settled afterwards, money functions as a means of payment. The use of money as a means of payment may come into conflict with money’s use as a store of value, and this is important in crises, when credit is given less readily and actual payments are demanded.

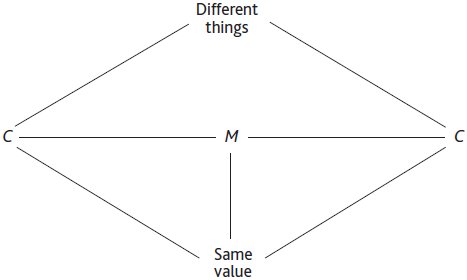

Consider initially a general problem: an individual owns some commodity but, for whatever reason, would prefer to exchange it for another. First, the commodity (C) must be exchanged for money (M). This sale is represented by C – M. Second, the money obtained is exchanged for the desired commodity, M – C. In both cases, C – M and M – C, commodity values are realised on the market; the seller obtains money and the buyer acquires a use value, which may be used either in consumption or production. In general, then, commodities are sold in order to purchase other commodities, and this can be represented by C – M – C: the circulation of commodities. The two extremes of commodity circulation are denoted by C because they are in commodity form and have the same value, not because they are the same thing – indeed they cannot be the same thing, otherwise the whole purpose of the exchange is defeated, speculative activity in commodities aside.

We presume that both commodities have the same value, because commodity circulation (exchange) as such cannot add value to the goods or services being exchanged. Although some sellers can profit from the sale of commodities above value (unequal exchange), as with unscrupulous traders and speculators for example, this is not possible for every seller because whatever value one party gains in exchange must be lost to the other. In this light, simple commodity exchanges are summarised in Figure 3.1.

Typically, under capitalism, simple commodity exchanges can start with a worker or a capitalist. For the worker, the only commodity available to sell is her or his labour power, and this is exchanged for wages (M) and eventually for wage goods (C). Alternatively, the commodity sale C – M could also be undertaken by a capitalist, either in order to buy goods for personal consumption or to renew production, for example, through the subsequent purchase of labour power, raw materials, machines, and so on.

Figure 3.1 Simple commodity exchange: selling in order to buy

In contrast with simple exchanges, which start with commodity sales, capitalist production must start with the purchase of two types of commodities. These commodities are the means of production (inputs for further processing, machines, spare parts, fuel, electricity, and so on) and labour power. A necessary condition for the latter is the willingness on the part of the workers to sell this commodity. This willingness, an exercise of the ‘freedom’ of exchange, is forced on the workers: on the one hand, selling labour power is a condition of work, for otherwise the workers cannot gain access to the means of production, which are monopolised by capitalists. On the other hand, it is a requirement for consumption, as this is the only commodity that the workers are consistently able to sell (see Chapters 2 and 6).

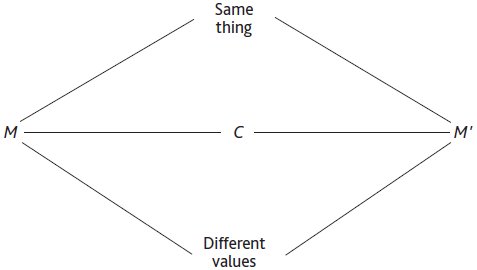

Having gathered together means of production and labour power (M – C), the capitalists organise and supervise the production process, and sell the resulting output (C – M). In the latter case, the dash conceals the intervention of production in the transformation of the commodity inputs into money (see Chapter 4). For the moment, we can represent a capitalist’s exchange activity by M – C – M’. In contrast to simple commodity exchange, C – M – C, discussed in the previous section, the capitalist circulation of commodities begins and ends with money, not commodities. This implies that at the two extremes one finds the same thing, money, rather than different things, commodities with distinct use values. Clearly, the only purpose in undertaking this exchange activity on a systematic basis is to get more value, rather than different use values (M’ must be greater than M). The difference between M’ and M is s, or surplus value. Capitalist exchanges are summarised in Figure 3.2.

Marx points out that capital is self-expanding value. Money acts as capital only when it is used to generate more money or, more precisely, when it is employed in the production of surplus value. This basic understanding of the nature of capital allows it to be distinguished from the various specific forms it assumes and the functions undertaken by those forms, whether as money, factor input or commodity. Each of these is capital only in so far as it contributes directly towards the expansion of the advanced value. As such, money functions as capital, as well as performing its specific tasks as means of payment, depository of exchange value, or means of production.

Figure 3.2 Capitalist exchange: buying in order to sell dearer

We have characterised capital through the activity of the industrial capitalists (which includes not only manufacturing capital, but also provision of services and other activities productive of surplus value). There are other forms of capital, though, namely merchant’s capital and loan capital. Both of these also expand value by buying (merchandise or financial assets rather than means of production) in order to sell dearer. Both appear historically before industrial capital. It was Marx’s insight to reverse their historical order of appearance, in order to analyse capitalism abstractly and in its pure form as a social system of production. This allows him to focus on the wage relation and the production of (surplus) value without the complications introduced by forms and relations of exchange, including mercantilism or usury, which merely transfer value (for a more detailed analysis of these forms of capital, see Chapters 11 and 12).

Surplus Value and Exploitation

Most economists might find this characterisation of capital as self-expanding value uncontroversial, even if a little odd. Looking back at Figure 3.2, and with reference to Figure 3.1, it is evident that although M and M’ have different values, M and C have the same value. This implies that extra value has been created in the movement C – M’. This added (surplus) value is the difference between the values of outputs and inputs. The existence of surplus value (profit in its money form) is uncontroversial, for this is obviously the motive force of capitalist production, and M – C – M’ is clearly its general form. The problem is to provide an explanation for the source of surplus value.

This has already been located in production, above, by showing that exchange does not create value. Therefore, among the commodities purchased by the capitalist there must be one or more that creates more value than it costs. In other words, for surplus value production at least one commodity must contribute more labour time (value) to the outputs than it costs to produce as an input; therefore, one of its use values is the production of (surplus) value. As already indicated, this leaves just one candidate – labour power.

First, consider the other inputs. While they contribute value to the output as a result of the labour time socially necessary to produce them in the past, the quantity of value that they add to the output is neither more nor less than their own value or cost – for otherwise money would be growing magically on trees or, at least, in machines. In other words, non-labour inputs cannot transfer more value to the output than they cost as inputs for, as was shown above, equal exchanges do not create value, and unequal exchanges cannot create surplus value, only change its distribution where it already exists.

Now consider labour power. Its value is represented by its cost or, more precisely, by the value obtained by the workers against the sale of their labour power. This typically corresponds to the labour time socially necessary to produce the wage goods regularly purchased by the working class. In contrast, the value created by labour power in production is the labour time exercised by the workers in return for that wage. Unlike the other inputs, there is no reason why the contribution made by the workers to the value of the output (say, ten hours per day per worker) should equal the cost of labour power (whose value may be produced in, say, five hours). Indeed, it can only be because the value of labour power is less than social labour time contributed that surplus value is created.

Using social labour time as the unit of account, it has been shown that capital can expand only if the value contributed by the workers exceeds the remuneration received for their labour power – surplus value is created by the excess of labour time over the value of labour power. Therefore, labour power not only creates use values: when exercised as labour it also creates value and, potentially, surplus value. The strength of this argument is seen by its brief comparison with alternative theories of value.

Theories of abstinence, waiting or inter-temporal preference depend upon the sacrifice by capitalists of present consumption as the source of profits. Nobody could deny that these ‘sacrifices’ (usually made in luxurious comfort) are a condition of profit, but, like thousands of other conditions, they are not a cause of profits. People without capital could abstain, wait and make inter-temporal choices until they were blue in the face without creating profits for themselves. It is not abstinence that creates capital, but capital that requires abstinence. Waiting has existed in all societies; it is even to be found among squirrels without their earning any profits. Similar conclusions apply to viewing risk as a source of profit. It must always be borne in mind that it is not things, abstract or otherwise, that create economic categories, for example profits or wages, but definite social relations between people.

Marginal productivity theories at the heart of mainstream economics explain the increase in value between C and M’ by the technically (or physically) determined contributions of labour and capital goods to output. Such an approach can have no social content, and it offers no specific insight into the nature of labour and ‘capital’ when attached to capitalism. For labour and labour power (never clearly distinguished from one another) are treated on a par with things, while the theory has neither the interest in explaining, nor the capacity to explain, the social organisation of production. Only the quantities of means of production and labour power matter, as if production were primarily a technological rather than a social process. However, factors of production have existed in all societies; the same cannot be said of profits, wages, rents or even prices, which, in their current pervasiveness, are new, historically speaking. Explanation of the form of the production process, the mode of social interaction and reproduction based upon it, and the categories to which they give rise demands more than mainstream economic theory is able to offer.

Marx argues that all value (including surplus value or profit) is created by labour, and that surplus value is brought about by the exploitation of direct or living labour. Suppose that the average workday is ten hours, and that the wages correspond to half the value created in this labour time. Then for five hours each day work is ‘free’ for the capitalist class. In this case, the rate of exploitation, defined as the ratio of surplus to necessary labour time, is five hours divided by five hours, or one (100 per cent). Although Marx refers to the rate of surplus value when being specific about exploitation under capitalism, this concept could be similarly applied to other modes of production, for example feudalism with feudal dues or slavery. The difference is that, in these last two cases, the fact of exploitation and its measure are apparent while, under capitalism, exploitation in production is disguised by the freedom of exchange.

Denote surplus labour time by s and necessary labour time by v. Together s and v make up the living labour, l. With s known as surplus value, v is called variable capital, and l is the newly produced value:

s + v = l

The rate of exploitation is e = s/v. Marx calls v variable capital because the amount of value that will be added by the workers, l, is not fixed in advance, when they are hired, but depends upon the amount of work that can be extracted on the production line, at the farm, or in the office. It is variable, in contrast to constant capital, c. This is not fixed capital (as is, for example, a factory that lasts several production cycles), but the raw materials and the wear and tear on fixed capital, in so far as these are consumed during the period of production. For example, a building or machine that has a value of 100,000 units of labour time, but which lasts for ten years, will contribute 10,000 units of value per annum to constant capital. The value of constant capital does not vary during production (since only labour creates value), but is preserved in (or, in other work, transferred to) the output by the worker’s labour, a service freely and unwittingly performed for the capitalist. Clearly, c and v are both capital because they represent value advanced by the capitalists in order to make profit. Therefore, the value λ of a commodity is made up of constant and variable capital plus surplus value, λ = c + v + s. Alternatively, λ can be seen to include constant capital c plus living labour v + s; finally, the cost of the commodity is c + v, with surplus value (s) forming the capitalist’s profits.

Absolute and Relative Surplus Value

The surplus value produced depends on the rate of exploitation and the amount of labour employed (which can be increased by accumulation of capital; see Chapter 6). Assume, now, that real wages remain unchanged. The rate of exploitation can be increased in two ways, and attempts to increase it will be made. For the nature of capital as self-expanding value imposes a qualitative objective on every capitalist on pain of extinction (that is, business bankruptcy and, potentially, degradation into the class of wage workers): profit maximisation, or at least that the growth of profitability should take a high priority.

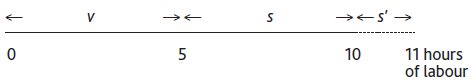

First, e can be increased through what Marx calls the production of absolute surplus value. On the basis of existing methods of production – that is, with commodity values remaining the same – the simplest way to do this is through the extension of the working day. If, in the example given above, the working day is increased from ten to eleven hours, with all else constant, including the wages, the rate of exploitation rises from 5 ⁄ 5 to 6 ⁄ 5, an increase of 20 per cent. The production of absolute surplus value (s’) is illustrated in Figure 3.3 (total surplus value is s + s’).

Figure 3.3 Production of absolute surplus vale (s’)

There are other ways of producing absolute surplus value. For example, if work becomes more intense during a given working day, more labour will be performed in the same period, and absolute surplus value will be produced. The same result can be achieved through making work continuous, without breaks even for rest and refreshment. The production of absolute surplus value is often a by-product of technical change, because the introduction of new machines, such as conveyors and, later, robots in the production line, also allows for the reorganisation of the labour process. This offers an excuse for the elimination of breaks or ‘pores’ in the working day that are sources of inefficiency for the capitalists and, simultaneously, leads to increased control over the labour process (as well as greater labour intensity) and higher profitability, independently of the value changes brought about by the new machinery.

The desired pace of work could also be obtained through a crudely applied discipline. There may be constant supervision by middle management and penalties, even dismissal, or rewards for harder work (i.e. producing more value). But more indirect methods might also be employed. A system of wages based on piece rates, for example, is meant to encourage the workers to set a high pace of labour, while a premium for overtime is an inducement to work beyond normal hours (although the premium must not absorb the entire extra surplus value created in that additional time, for otherwise there would be no extra profit for the capitalist).

Yet another way of producing absolute surplus value is the extension of work to the whole working-class family. On the face of it, children, wife and husband all receive separate wages. But the structural role played socially by those wages is to provide the means to reproduce the working-class family and, therefore, the working class as a whole. With the extension of waged work to the whole family, labour-market pressure (lower wages due to more workers seeking employment) could even result in more labour being provided for little or no increase in the value of wages as a whole.

There are limits to the extent to which capitalism can depend upon the production of absolute surplus value. Quite apart from the natural limits of the number of hours in the day and the physiological requirements of reproduction of the workers, resistance of the working class and, as the result of this, labour laws and health-and-safety rules can offer barriers to the extraction of absolute surplus value. Nevertheless, absolute surplus value is always important in the early phases of capitalist development, when workloads tend to increase rapidly, and at any time it is a remedy for low profitability (even for contemporary developed capitalist countries) – to the extent that the medicine can be administered.

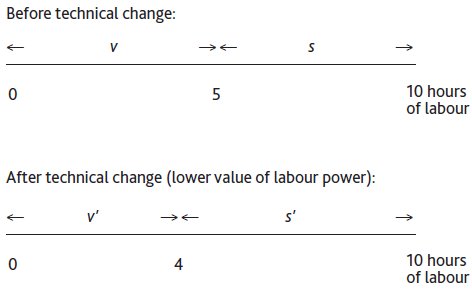

Relative surplus value does not suffer from the same limitations, and it tends to become the dominant method of increasing e as capitalism develops (see Chapter 6). Relative surplus value is produced through the reduction of the value of labour power (v) by means of improvements in the production of wage goods (with a constant real wage) or, more generally, through the appropriation of productivity gains by the capitalist class. In this case, the working day remains the same, for example at ten hours, but, because of productivity gains (either directly, or indirectly through the constant capital used) in the production of wage goods, v falls from five to four hours, leaving a surplus value of six hours (e rises from 5 ⁄ 5 to 6 ⁄ 4, that is, by 50 per cent). There are several ways to achieve this result, including increased co-operation and finer division of labour, use of better machinery, and scientific discovery and innovation across the economy. The production of relative surplus value is illustrated in Figure 3.4. As a result of technical change, v falls to v’, and relative surplus value is produced in addition to the old surplus value. (This figure should be compared with Figure 3.3.)

Figure 3.4 Production of relative surplus value

The production of absolute surplus value can be based on the grim determination of individual capitalists, using the threat of punishment, dismissal and lockouts, with supportive state intervention rarely found wanting when required; for example, in order to protect the viability of the firm, the competitiveness of the industry or to promote the ‘national interest’. In contrast, production of relative surplus value depends upon all capitalists, since none alone produces a significant proportion of the commodities required for the reproduction of the working class. In particular, it depends upon competition and accumulation in the economy as a whole inducing technical changes that bring down the value of labour power.

Machinery and Technical Change

Marx attaches great importance to the analysis of the way in which production develops under capitalism. He devotes considerable attention both to the power relations between workers and capitalists, and to the technical relations under which production takes place, while also showing that they should not be treated separately: production technologies embody relations of power. In particular, for developed capitalism, Marx argues that the factory system necessarily predominates (rather than, for example, independent craft production or the putting-out system, in which capitalists provide inputs to handicraft workers and, later, collect their produced commodities). Within the factory, the production of relative surplus value is pursued systematically through the introduction of new machinery, which can bring, at least temporarily, extraordinary profits to the innovating capitalist.

New machinery increases productivity because it allows greater amounts of raw materials to be worked up into final products in a given labour time. Initially, the physical power of the worker is replaced by the power of machinery. Later, the workers’ tools are incorporated into the machinery, turning the workers into minders or appendages of the machines – to feed the machines and watch over them, and to become their servants rather than vice versa (which may, nevertheless, require high levels of technical expertise).

The introduction of machinery increases the intensity of work in a way that differs from that experienced under the production of absolute surplus value, for new machinery inevitably restructures the labour process. This has contradictory effects on the working class. They are deskilled by the machinery that displaces them and simplifies their tasks at work, but they are also required to command new skills as a number of these simplified tasks are combined, often simply so that more complex machines can be operated at higher levels of productivity. Similarly, though the physical burden of work is lightened by the power of machinery, it is also increased through the higher pace, intensity and restructuring of work, and by the need to adapt human bodies to the demands imposed by new technology.

To a large extent, this analysis presupposes a given set of products and production processes which are systematically transformed through the increasing use of machinery. Marx does not neglect, indeed he emphasises, the roles of science and technology in bringing forth innovation in both products and processes. But such developments cannot be the subject of a general theory, since their extent and rhythm do not generally take place under the command of capitalist production and are contingent upon the progress of scientific discovery, the translation of discoveries into more productive technologies, and their successful introduction into the workplace. Nevertheless, Marx concludes that the factory system leads to a massive increase in the ratio of physical capital to labour – what he termed the technical composition of capital (see Chapter 8). On the one hand, this follows from the definition of productivity increase, since each labourer works up more raw materials into final products (otherwise productivity would not have risen). On the other hand, this is a condition for productivity growth, since the mass of fixed capital in the form of machinery and factories must also increase.

Productive and Unproductive Labour

Marx’s distinction between productive and unproductive labour is a corollary of his concept of surplus value. Wage labour is productive if it produces surplus value directly. This implies that productive labour is wage labour performed for (and under the control of) capital, in the sphere of production, and directly producing commodities for sale at a profit. The commodities produced and the type of labour performed – ranging from shipbuilding through harvesting to computer programming, or to teaching or singing – are irrelevant; in addition, commodities evidently need not be material.

All other types of ‘wage’ labour are unproductive: for example, labour that is not hired by capital (such as independent producers of commodities, the self-employed, and most government employees), labour that is not directly employed in production (such as managers or workers employed in exchange activities, including the retail and financial sectors, as well as accountants, salespeople and cashiers, even if they are employed by industrial capital), and workers not producing commodities for sale (such as housemaids and other independent providers of personal services).

The productive–unproductive distinction is specific to capitalist wage labour. It is not determined by the product of the activity, its usefulness or its social importance, but by the social relations under which labour is performed. For example, doctors and nurses can perform either productive or unproductive labour, depending on their form of employment – at a private clinic or a public hospital, for example. Even though their activities are the same, and possibly equally valuable for society in some sense, in one case their employment is contingent upon the profitability of enterprise, while in the other case they provide a public service that is potentially free at the point of delivery.

It is important to emphasise that, although unproductive workers do not directly produce surplus value, they are exploited if they work for longer than the value represented by their wage – being unproductive is no obstacle to capitalist exploitation! From the point of view of capital, unproductive sectors – retailing, banking, or the public health system, for example – are a drag on accumulation because they absorb part of the surplus value produced in the economy in order to obtain the wherewithal to pay wages, other expenses and their own profits. This is done through transfers from the value-producing sectors via the pricing mechanism. For example, commercial capital purchases commodities below value and sells at value, whereas interest-bearing capital (including banks and other financial enterprises) obtains revenue primarily through the payment of customer fees and interest on loans (see Chapters 11 and 12). Finally, public services are funded by general taxation and, in some cases, user fees. None of this suggests that unproductive sectors are either ‘useless’ in general or simply a drag on social prosperity: these sectors and their workers can perform useful service for society and/or the accumulation of capital as a whole – but they do not directly produce surplus value.

Volume 1 of Capital is in part concerned with the question: how is profit compatible with freedom of exchange? The answer given transforms the question into one of how surplus value is produced. This, in turn, is answered by reference to the unique properties of labour power as a commodity, and the extraction of both relative and absolute surplus value. Marx addresses these in the theoretical terms covered here, but also in some empirical detail, focusing on changes in production methods themselves, especially the shift from manufacturing (literally production by hand) to the factory system.

It is important to Marx to explain the source of surplus value prior to examining how it is distributed as profit (and interest) and rent – something he does in Volume 3 of Capital (covered in later chapters). He designates profit, rent and wages as the ‘Trinity Formula’. These forms of revenue, which have very different origins and places in the structures and processes of the capitalist system, are subject to the illusion that they are symmetrically placed as the prices of capital, land and labour, respectively, as opposed to being the basis for a system of exploitation.

Marx’s theory of capital and exploitation is explained in several of his works, especially Marx (1976, pts 2–6). The interpretation in this chapter draws upon Ben Fine (1998) and Alfredo Saad-Filho (2002, chs 3–5, 2003b). For similar approaches, see Chris Arthur (2001), Duncan Foley (1986, chs 3–4), David Harvey (1999, chs 1–2), Roman Rosdolsky (1977, pt.3), John Weeks (2010, ch.3) and the references cited in Chapter 2.

Once the specificity of Marx’s value theory and his emphasis on the uniqueness of labour power as a commodity are accepted, his theory of exploitation to explain surplus value and profit is relatively uncontroversial. It is necessary, though, to see surplus value as the result of coercion to work beyond the value of labour power rather than as a deduction from what the worker produces or as a share taken in the division of net product (as in what are termed Sraffian or neo-Ricardian approaches). On this, see Ben Fine, Costas Lapavitsas and Alfredo Saad-Filho (2004), Alfredo Medio (1977) and Bob Rowthorn (1980, especially ch.1). Marx’s theory of exploitation has inspired a rich vein of complementary analyses of the labour process, both in its technical and in its organisational aspects. Science and technology do not simply improve technique; they are governed, if not determined, by the imperative of profitability, with the corresponding need to control and discipline labour (thereby influencing what is invented and how, and, similarly, what is adopted in production and how); see Brighton Labour Process Group (1977), Les Levidow (2003), Les Levidow and Bob Young (1981, 1985), Phil Slater (1980), Bruno Tinel (2012) and Judy Wajcman (2002). In addition, there is an imperative to guarantee sale (at a profit), with a corresponding departure in products and methods of sale from the social needs of consumers (however defined and determined) in pursuit of private profitability of producers; see Ben Fine (2002) for example. By way of contrast with mainstream economics, for which work has become treated as a disutility by necessity as opposed to a consequence of its organisation under capitalism, see David Spencer (2008).

Finally, the distinction between productive and unproductive labour is important as a starting point for examining the different roles played by industrial, financial, public sector and other workers in economic and social reproduction (see Chapter 5). One debate has been over whether the distinction is valid or worthwhile – for example, on the grounds that all exploited (wage) labour should be lumped together as sources of surplus value. Another debate, amongst those who accept the distinction, concerns who should count as productive: this can be narrowly defined, as including only manual wage labour, or more broadly, to include all waged workers. Marx explains his categories of productive and unproductive labour in Marx (1976, app., 1978a, ch.4). These categories are discussed by Ben Fine and Laurence Harris (1979, ch.3), Simon Mohun (2003, 2012), Isaak I. Rubin (1975, ch.19, 1979, ch.24) and Sungur Savran and Ahmet Tonak (1999).