The Circuit of Industrial Capital

Volume 1 of Capital is largely self-contained, and it primarily gives a general analysis of capitalism and its process of development from the perspective of production – what are the social relations that allow capital to create surplus value and how do these give rise to economic realities and social developments around production? The other two volumes of Capital are devoted both to elaborating and to extending this general analysis. For this reason it is appropriate that the beginning of Volume 2 should analyse the circuit of capital. This is because this circuit provides the basis for understanding a whole series of phenomena – commercial, interest-bearing and fixed capital, distribution of income and output, the turnover of capital, productive and unproductive labour, and crises – as well as providing an economic structure in which the social relations of production analysed in Volume 1 can be presented in more concrete form. In other words, Volumes 2 and 3 are about how the value relations of production, studied in Volume 1, give rise to more complex outcomes through the processes and structures of exchange and distribution.

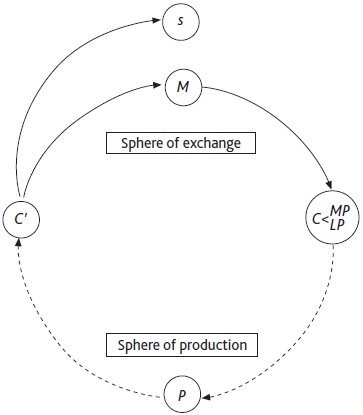

Volume 2 begins with an account of the money circuit of capital. This is an expansion of the characterisation of capital as self-expanding value (see Chapter 3), taking explicit account of the process of production. The general form of the circuit of industrial capital is:

Under the most general circumstances, and regardless of the commodity produced, the industrial capitalists advance money capital (M) in order to purchase commodity inputs (C), comprising labour power (LP) and means of production (MP). It should be realised that money is necessary for these transactions, but does not in itself make them possible. It is the separation in ownership of labour power from the means of production – a class relation of production – that allows a definite group of people (the capitalists) to hire others (the workers) in exchange for a wage. This can be stressed by explicitly separating the means of production and labour power in the circuit of capital:

![]()

On purchase, the inputs (C) form productive capital (P). Production proceeds as labour power is exercised on the means of production, and the result is different commodity outputs, with a higher value (C’). C and C’ are linked to P by dots to indicate that production has intervened between the purchase of inputs (C) and sale of outputs (C’). The commodities produced are denoted by C’ not because their use value is different from that of the means of production (although this is generally the case), but because they contain surplus value over and above the value of the advanced capital, M. This is shown by the sale of the output for more money capital, M’ > M.

It was shown in Chapter 3 that surplus value, s = M’ – M, is created in production by the purchase of labour power at its value, which is less than the labour time expended (value created) in production. Surplus value makes its first appearance in commodity form immediately after production. Since the inputs (especially labour power, tools, machines and buildings) seem symmetrical in their contribution to output, it is easy to credit the creation of surplus value to the ‘productivity’ of all the factor inputs without distinction. Correspondingly, it is difficult to credit surplus value to the excess of actual over necessary labour time, because the appearance of surplus value is delayed until after production has taken place, whereas the free exchange of labour power for its value takes place before production (even if the wages are paid in arrears).

The produced value (and surplus value) is now converted into money by the sale of the output on the market. Having obtained sales income M’, the capitalists can renew the circuit of capital – either on the same scale (by renewing the original advance, M, with given prices and technologies, and spending the surplus value on consumption), or by embarking on an expanded productive circuit, through the investment of part of the surplus value (see below, and Chapter 5).

It was shown above (and in Chapter 3) that capital is the social relation underpinning the self-expansion of value, or the production, appropriation and accumulation of surplus value. Capital, as self-expanding value, is essentially the process of reproducing value and producing new value. The circuit of capital describes this motion, and it highlights that capital takes different forms in its reproduction process. The social relation that is capital successively assumes and relinquishes the forms of money, productive capital and commodities.

The circuit of industrial capital is best represented by a circular flow diagram (see Figure 4.1). This circuit is important for laying out the basic structure of the capitalist economy and for showing how the spheres of production and exchange are integrated with one another through the movement of capital as (surplus) value is produced, distributed and exchanged. As the circuit repeats itself, surplus value (s) is thrown off. Thus, capital as self-expanding value embraces not only definite social relations of production, but is also a circular movement as it goes through its various stages repeatedly. If s is accumulated for use as capital, we can think of expanded reproduction as being represented by an outward spiral movement.

Figure 4.1 The circuit of capital

Industrial capital changes successively into its three forms: money capital (M), productive capital (P) and commodity capital (C’). Each form presupposes the existence of the other two because it presupposes the circuit itself. This allows us to distinguish the specific function of each of the forms of capital from its general function as capital. In societies where they exist, money, factor inputs and commodities can always function, respectively, as means of payment, means of production and depositories of exchange value, but they only serve as (industrial) capital when they follow these functions sequentially in the circuit of capital. Then, money capital acts as a means of purchasing labour power, productive capital acts as a means of producing surplus value, and commodity capital acts as the depository of surplus value to be realised as money upon sale.

In the movement through the circuit, two spheres of activity can be identified: production and circulation (exchange). The sphere of production lies between C and C’. In this sphere, use values are transformed and value and surplus value are created. This has profound implications for Marx’s theory of distribution, because it explains what there is to be distributed as well as the structures and processes of distribution of goods and values in the economy. The sphere of circulation contains the process of exchange between C’ and C, and the realisation of surplus value, s.

It was shown in Chapter 3 that even if capital and labour are employed in exchange they add no value to the output. This conclusion seems strange to mainstream economists because they are usually interested in obtaining a price theory by aggregating the (supposedly independent) contribution of all the factors used in production and exchange. But Marx is interested in the social relations of production and distribution, and in the structures of distribution of the values produced during the circuit. For example, he argues that whereas commercial capital adds no value, this does not prevent it from receiving a share of the (surplus) value produced (see Chapter 11).

By constructing the circuit of capital in circular form, as in Figure 4.1, it becomes arbitrary to open and close the circuit with money capital, since a circle has neither beginning nor end. Note that the money circuit contains the interruption of the sphere of circulation by the sphere of production. In characterising capital as self-expanding value, it has been shown that the capitalists’ motive is to buy in order to sell more dearly. So, for capital seen from the perspective of the money circuit, production appears as a necessary but unfortunate (and even wasteful) interruption in the process of money making. Merchant’s and interest-bearing capital avoid this interruption, although they depend upon production taking place elsewhere. However, what is possible for an individual (merchant or interest-bearing) capitalist does not hold for all (or even most) capitalists. If a nation’s capitalists were seized by the attempt to make profit without the unavoidable link of production, they would find themselves in a speculative boom that would eventually crash. At this point the economy would be brought back to the reality of the need for production – the only possible source of the value required to pay dividends, settle debts, service interest commitments and clear financial obligations (see Chapters 7, 12 and 14).

Marx also analyses the circuit from two other perspectives, those of productive capital and commodity capital. The circuit of productive capital begins and ends with P, production. The purpose of the circuit appears to be production and, in so far as surplus value is accumulated, production on an extended scale. In contrast to the money circuit, for the productive circuit the sphere of circulation appears as a necessary but unwanted intrusion in the process of production. But it has been shown above that it is not sufficient to produce (surplus) value; it has to be realised on sale. Economists more often than capitalists tend to ignore this necessary but uncertain mediation by exchange, for a capitalist who unwittingly accumulates a growing inventory of commodities is soon brought back to reality with the loss of working capital. Finally, the circuit of commodity capital begins and ends with C’, and so its purpose appears to be to satisfy society’s consumption needs. As the sphere of circulation is followed by the sphere of production, neither sphere is interrupted by the other, so neither appears as unnecessary or wasteful.

The three circuits of capital derive from the circuit as a whole. One might wonder why there are not four circuits of capital, with each ‘node’ on the circuit (P, C’, M and C) forming a starting and finishing point. The reason C is not the basis for a circuit of capital is that it is not capital. The purchased means of production may be another capitalist’s commodity production and hence commodity capital. However, labour power is never capital until it is purchased, and then it becomes productive capital and not commodity capital, which must contain produced surplus value. Thus, while from a technical point of view capitalism can be self-reliant for raw materials, it always and necessarily depends on the social reproduction of labour power from outside the pure system of production (see Chapter 5). This entails the use of political, ideological and legal as well as economic power in order to get the labourer to work. The same problems do not exist in getting a machine to work.

It has been shown above that different views of capital’s process of reproduction can be constructed, each corresponding to one of the circuits of capital. These need not be uncritical of capitalism, but individually they are always inadequate, stressing one or more of the processes of production, consumption, exchange, profit making and accumulation at the expense of the others. For example, only fleetingly, as they enter the circuit, do labour power and produced means of production appear separated and then, not forming capital, they do not spontaneously generate a view of the circuit as a whole. Partly for this reason, mainstream economic theory appears to eliminate class relations altogether. However, these relations re-enter mainstream theory as distributional or exchange relations, rather than as relations of production.

In contrast, the money circuit suggests models of exchange. For mainstream economics, the matching of supply and demand becomes the be all and end all, and capital and labour are seen as merely productive services. Difficulties are associated with the informational services performed by the price (and interest rate) mechanism. The productive circuit, in turn, tends to ignore the market, and neoclassical and most growth theories can be cited in this context. This yields an excellent input–output analysis of economic reproduction, but the economy is not clearly capitalist at all. Finally, the commodity circuit is reflected in neoclassical general equilibrium theory, where supply and demand harmoniously interact through production and exchange to yield final consumption. This circuit supports the myth that the purpose of production is consumption rather than profit or exchange, and it is well-illustrated by Edgeworth box diagrams, familiar to economics students. One of the strengths of Marx’s circuit of capital is to expose the limitations of these outlooks. At the same time, it reveals the functions of the forms in which capital appears and constructs a basis on which major economic categories and phenomena can be understood.

Marx’s analysis of exchange, especially in Volume 2 of Capital, has been relatively neglected despite the insights it offers. Often an approach has been adopted of complementing his theory of production with the Keynesian theory of effective demand, as if the two aspects of Marx’s theory were subject to separate treatments. As suggested here and in Marx’s own account, production and exchange are structurally separated, but integrally related through the circuits of capital. Marx’s own analysis of the circuit of capital is developed in Marx (1976, pt.2, 1978b, pts 1–2). It is explained in Ben Fine (1980, ch.2) and Alfredo Saad-Filho (2002, chs 3–5). On Volume 2 of Capital, see Chris Arthur and Geert Reuten (1998). For similar interpretations to those offered here, see David Harvey (1999, ch.3) and Roman Rosdolsky (1977, pt.4). The concepts of money as money and money as capital are explained by Costas Lapavitsas (2003a) and Roman Rosdolsky (1977, pt.3).