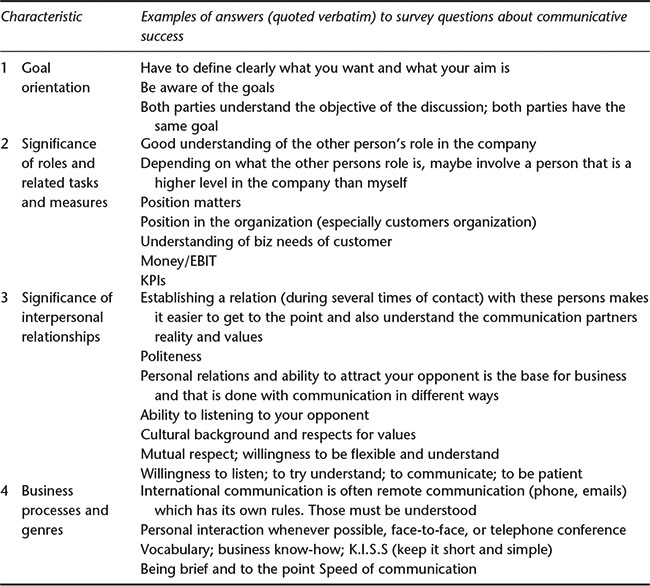

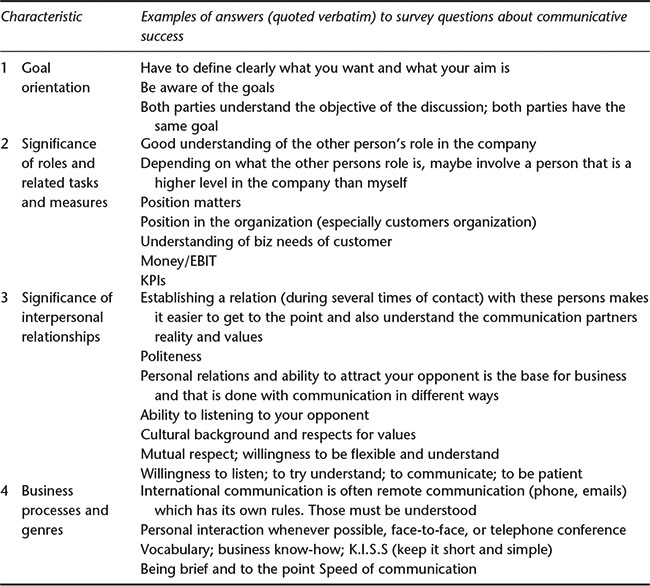

Table 25.1 Characteristics of business knowledge as perceived by practitioners

p.309

ELF in the domain of business—BELF

Anne Kankaanranta and Leena Louhiala-Salminen

Introduction

Since the introduction of the concept of BELF (English as a business lingua franca; Louhiala-Salminen et al., 2005) it has inspired a number of researchers in applied and socio-linguistics, in business communication in particular, and recently also in the discipline of international management (e.g. Piekkari, Welch, & Welch, 2014). The concept of BELF was developed to grasp three imperative qualities that make it distinct within the ‘umbrella discipline’ of ELF (English as a lingua franca): its domain of use (international business), the role of its users (professionals), and the overall goal of the interactions (getting the job done and creating rapport).

Interestingly, the concept of BELF has been acknowledged and accepted in (socio)linguistic and even international management research to such an extent that the epistemological grounds of the ‘B’ have not really been addressed. In addition to journal articles in various outlets such as English for Specific Purposes, Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, (International) Journal of Business Communication, and Public Relations Review, BELF research has found its way into handbooks, review articles and books dealing with language issues in international management. For instance, Gerritsen and Nickerson (2009) address BELF as a specific approach and methodology in the Handbook of Business Discourse and argue for the need of systematic, empirical investigations into the causes of failure in BELF communication. Simultaneously, they are offering a future research agenda, which should focus on comprehensibility challenges, cultural differences, and stereotyped associations. Further, in their review of developments in research into ELF, Jenkins et al. (2011: 298) point out that “in the past few decades it has become widely accepted that the lingua franca of international business is English” and then continue on summarizing BELF research in the business domain. BELF has also found its way into the discipline of international management, which is inherently interested in the management of language in multinational companies, albeit “not on how ‘English’ is conceptualized, how it is used, or what the discourse is like” (Kankaanranta et al., 2015: 134). In their book on language in international management, Piekkari et al. (2014) address BELF from the point of view of global business expansion in general, and in particular discuss language management issues in various corporate functions such as human resource management, marketing, and foreign operations. For them, language is inherently present in various business operations. In yet another handbook focusing on economics and language, Holden (2016: 291) further argues that “none of the great empires of the Ancient World” involved in international business could have survived “without a fully functioning language of business” (emphasis added): a professional communication system (both written and spoken) with specific business terminology, sensitivity to context, and a variety of business partners.

p.310

Although ELF and BELF share a number of characteristics, what makes BELF distinct is the B, ‘business.’ The three key contextual features of the domain of use, the role of its users and the overall goal of the interactions are closely intertwined with business knowledge, which, as Louhiala-Salminen and Kankaanranta (2011) argue, is the key component of professional communicative competence in the global business context. In their model of Global Communicative Competence, business knowledge forms the outermost layer, thus emphasizing its integral role in successful communication. The two other layers, BELF competence and multicultural competence, overlap with business knowledge (Louhiala-Salminen & Kankaanranta, 2011: 258). But, what exactly does that business knowledge entail?

In this chapter, we elaborate on the notion of business knowledge among BELF speakers and present how business practitioners and scholars conceptualize such knowledge. After reviewing some relevant literature, we introduce our empirical study on the perceptions of both business practitioners and scholars on the ‘B’ of BELF. Finally, we conclude by discussing the question if and why we need the concept of BELF in the first place.

Literature review

It comes as no surprise for an ELF researcher today that the dynamic notion of ‘ELF resource’ also questions such traditional fundamentals of sociolinguistics as variety, domain and location of use. In today’s globalized and technologized/digitalized environment, the notion of speech community seems outdated in view of the heterogeneous speakers of different mother tongues who use English—or rather ELF—all over the world. For instance, ELF researchers have used Wenger’s (1998) notion of community of practice to embrace the ELF resource and its users (see e.g. Seidlhofer, 2006; Dewey, 2010; Ehrenreich, 2010a; Cogo, 2016). However, the notion has recently met with criticism because the shared ELF repertoire does not typically exist a priori (Jenkins, 2015; also Dewey, 2010; Seidlhofer, 2011). Indeed, for example, Jenkins (2015) argues for Pratt’s (1991) notion of ‘contact zones’ as better capturing the transient and ad hoc nature of ELF groupings, while for the more established BELF communities Wenger’s (1998) notion finds a better fit.

Interestingly, the concept of speech community has not been much used in (international) business communication research, where the use of English in cross-border contacts has been on the research agenda since the 1990s. With the acceleration of international mergers and acquisitions, business communication scholars started to examine questions related to the communication of individual employees and teams who used (non-native) English to do their work (e.g. Firth 1996; Louhiala-Salminen 1997, 2002; Nickerson, 2000; Poncini, 2003; Kankaanranta 2005; Louhiala-Salminen & Charles 2006; Du-Babcock 2009; Pullin Stark, 2009). Many of these studies were pedagogically motivated as the researchers set out to investigate the implications of the spreading use of English for the teaching of English or English Business Communication. For this strand of research, such theoretical constructs drawn from applied linguistics as ‘discourse community’ and ‘genre’ (e.g. Swales 1990) were frequent tools for analyzing the usage of English for/in international business communication. In the 2000s, along with ever-advancing globalization and English turning into the most used corporate language the question of the impact of ELF on professional communicative competence is still very relevant (see e.g. Louhiala-Salminen & Kankaanranta 2011, 2012). The notion of BELF is frequently applied to refer to the current business context, where languages and cultures are intertwined and the main language for communication is English used as a lingua franca, in a dynamic interplay with other languages and linguistic resources (e.g. Evans, 2013; Pullin, 2010).

p.311

To examine the significance of the ‘B’ for the concept of BELF, we chose to apply the notion of community of practice as our analytical tool. We will discuss it at a high level of abstraction and view it from the perspective of the domain of (international) business and the community of internationally operating business practitioners. While attempting to gain an overall understanding of the ‘B,’ we will—unavoidably—lose some depth and detail of such smaller CoPs as individual teams, corporations and industries

Wenger’s (1998) key theoretical focus is learning as social participation but since we are interested in the ‘B,’ we modify Wenger’s (1998: 4) elaboration of participation to refer to the process of being active participants in the business practices of social (business) communities and constructing identities in relation to these communities. We will also refer to Ehrenreich’s (2010a) study of BELF usage among the business executives in a German multinational company. For our purposes, CoP with its three dimensions is particularly relevant in order to come to terms with the notion of ‘business knowledge,’ which is assumed to be shared among internationally operating business professionals of the domain.

As Wenger (1998: 47) argues, practice connotes doing in a (historical and social) context, which gives structure and meaning to the doing. Practice thus involves that doing but it also involves knowing about the doing, both explicitly and implicitly—neither can exist alone. The explicit represents, for example, language, tools, regulations and codified procedures, whereas the implicit refers to underlying assumptions, shared worldviews and untold rules of thumb (see also e.g. Nonaka et al., 1996). Typically, implicit knowledge may never be verbalized, but it is still like the glue tying the members of the particular community together and is essential for its success. Understood in this way, practice is the source of coherence of a community through three dimensions of their relationship: mutual engagement, joint enterprise and a shared repertoire (Wenger, 1998: 72–73).

First, mutual engagement refers to people being engaged in actions whose meanings they can negotiate with each other (Wenger, 1998 73). As Ehrenreich (2010a: 131) points out in her study of BELF usage in a German multinational company, the executives belonged to different CoPs simultaneously, and interacted in various ways both face-to-face and virtually. Although both Wenger (1998: 74) and Ehrenreich (2010a) argue that mutual engagement requires interactions, we could also see this dimension on a higher level of abstraction in the sense that the interaction could be—and is—possible because of shared knowledge of business fundamentals gained in education and/or in practice (linked to joined enterprise and shared repertoire) among business practitioners.

Second, joint enterprise refers to “the participants’ negotiated response to their situation” (Wenger, 1998: 77). Although the participants may have a stated goal that they strive to achieve, they need to negotiate their way through by creating relations of mutual accountability. In other words, the members of the community negotiate a shared understanding of such key notions as “what matters and what does not, what is important and why it is important, what to talk about and what to leave unsaid” (Wenger, 1998: 81). While some aspects of accountability may be reified into explicit statements, those statements need to be interpreted and a practice evolves around this process of interpretation. “Being able to make distinctions between reified standards and competent engagement in practice is an important aspect of becoming an experienced member” (Wenger, 1998: 82). In her study, Ehrenreich (2010a) argues that the overall goal of a business CoP—such as the one she investigated in a German multinational—is profit making. Within this overall goal, the members of the community contribute by, for example, negotiating contracts and ensuring deliveries within a time frame. For an outsider the appropriateness or relevance of that work may not fully unfold and novices of the community learn from the more experienced members.

p.312

Third, a shared repertoire involves the production of resources that are needed in the practice and in the negotiation of meaning within the community (Wenger, 1998: 83). Such resources may be activities, symbols, or artifacts including specific routines, words, tools, ways of doing things, genres, symbols, and concepts. Ehrenreich (2010a: 133) gives examples of the shared repertoire of the business executives of a German multinational including languages (e.g. German, English) and documents (e.g. drawings, charts, power point presentations). Wenger further emphasizes that the repertoire is shared in a dynamic and interactive way and it does not suggest shared beliefs are in any way essential for a shared practice.

Study: what does ‘B’ stand for?

As the purpose of this study was to increase knowledge of the ‘business’ component of BELF, we made the assumption that finding out about ‘business knowledge’ from those actively engaged, first, in business practice and second, in business research would help us to elaborate on the specific character and significance of the ‘B’ and thus discuss BELF’s position within ELF research overall.

Methods

To achieve this aim, two kinds of data were used: (1) we revisited the data (683 open survey answers) that we had gathered for a major research project (see Louhiala-Salminen & Kankaanranta, 2011), which focused on the perceptions of internationally operating business professionals on communication; and (2) we conducted 15 email interviews among professor-level faculty of an international business school.

The first set of data comes from an online questionnaire survey conducted in 2007–2008, which set out to identify features of successful communication in international business (for details, see Louhiala-Salminen & Kankaanranta, 2011; Kankaanranta & Planken, 2010). The 987 respondents of the survey worked for five globally operating companies (cargo handling, logistics, and consulting); they represented different organizational levels and 31 different native languages, although most of them came from Finland and other parts of Western Europe. The survey (response rate 52 percent) provided rich data through which it was possible to get a wide and reliable overview of how international business professionals perceive communicative success and its constraints. For the present study, we focused on the three open-ended questions of the survey, which addressed the respondents’ perceptions about the factors that (1) make communication succeed, (2) make communication fail, and (3) confirm that a communicative act succeeded in the global business environment. Through the answers to the questions we looked for the informants’ conceptualizations of ‘business knowledge’ and its components. Naturally, all 987 respondents did not answer the open questions, but these responses amounted to 230 (question 1), 230 (question 2), and 223 (question 3), which means that over 20 percent of the respondents gave their views of potential success/failure of communication using their own words.

p.313

The second set of data comes from email interviews (N = 15) that we conducted in February 2016 among the academic faculty of an international business school based in Finland. The informants represented different business disciplines, on the basis of which the following pseudonyms were drafted, i.e. finance (F), accounting (A1, A2), management (Mg), entrepreneurship (E), marketing (M1, M2), information and service management (ISM1, ISM2, ISM3), international business (IB1, IB2), sustainability (S), and organizational communication (OC1, OC2). Here, our aim was to explore and uncover the (at times hidden) views of business researchers of the ‘business fundamentals’ that belong to the shared knowledge base of business professionals. We posed two questions to our interviewees: From your perspective (as a business scholar), what elements are included in the concept of ‘business knowledge’? What are ‘the shared business fundamentals’ that a business professional would automatically know when working in the present-day business context? The questions were phrased as very open since we were looking for the personal views of the interviewees and their immediate reactions to the concept of ‘business knowledge,’ which was also emphasized in the cover message.

To analyze the data sets we used qualitative content analysis (e.g. Krippendorf, 2004). As an author team with business degrees, with over 25 years of work experience in educating business students, and with regular collaboration with business practitioners, we carefully read through all the answers and categorized them on the basis of our interpretation of what they revealed about the informants’ conceptualization of ‘business knowledge.’ The analysis of the academic faculty’s responses was a fairly smooth exercise and produced four perspectives to business knowledge. In analyzing the practitioner answers, we decided to approach the data with a set of wh-questions as well to more thoroughly understand, how the respondents view the scene of international business: Who are the actors? What do they do? Why do they do this? How do they act? Although the categorization necessarily required some negotiation, we finally combined the two analyses and formed four categories that seemed significant and distinctive enough to explain the respondents’ conceptualization of ‘business knowledge.’ In addition to the four categories each displaying a characteristic that the respondents included in the concept, we identified three overall qualities that we interpreted as essential for business operations. Taken together, both the four perspectives drawn from the business-faculty informants and the categories identified from the business-practitioner informants were comprehensive in the sense that the answers could be interpreted to refer to at least one of them.

Findings

The first data set—the business-practitioner respondents’ reactions to the three open questions related to communicative success in international contexts—consisted of a number of brief answers, typically consisting of a phrase or a few words that more or less directly answered the question. For example, to the question “Think of your own experience and list the main reasons that make communication succeed in the globalized business environment,” the following short answers were given: have to define clearly what you want and what your aim is; be sure targets are understood; the must to succeed; and agreed upon results and actions. However, there were also longer answers such as this one: Competence in the business, to be open and dialog with your partners/customers, understand strategic issues and personal interests or conflicts.

p.314

The overall qualities that emerged in the responses of the business-practitioner respondents were (1) ‘shared understanding,’ (2) ‘business mindset,’ and (3) the ‘win-win’ mentality. First, to be able to act in the business context it was important that the actor has a shared understanding with the other actors of the four fundamental characteristics listed below. The respondents referred to understanding, for example, ‘the business itself,’ ‘different terms,’ ‘objectives,’ ‘business processes,’ and of ‘what is necessary to get things done.’ Second, the significance of the ‘business mindset’ became conspicuous in the respondents’ descriptions on how things are/should be done. They highlighted such adverbs as quickly, smoothly, correctly, efficiently, on time, and repeatedly mentioned co-operation, trust, good relationships, willingness, and openness as essential elements for their communication. Finally, understanding the ‘win-win’ mentality emerged in many answers; in other words, your goals can only be reached if—at least in the long run—you simultaneously help the other party to reach theirs as well.

The particular characteristics of ‘business knowledge’ consisted of the knowledge of (1) goal orientation, (2) significance of professional roles and related tasks and measures, (3) significance of interpersonal relationships, and (4) business processes and genres. Table 25.1 lists the four characteristics and displays examples of the exact words by the respondents, on the basis of which characteristics were identified.

As can be seen in Table 25.1, the characteristics of ‘business knowledge’ that were formed on the basis of the open survey answers naturally emphasize the practitioner dimension. They stem from perceptions of international business professionals who were encouraged to think in very concrete terms of their daily situations at work, and give their answers from that point of view. The examples (verbatim quotes by the survey respondents) in Table 25.1 were chosen as representative of a large number of similar answers, where the particular characteristic could be drawn from. For example, in the answers ‘Goal orientation’ was described emphasizing the aims, objectives or goals, whose existence was assumed as shared knowledge among the participants. Similarly, the respondents highlighted the fact that they have to know both the organizational roles of their communication partners and the most frequently used measures for business success, e.g. such notions as KPI (key performance indicator) and EBIT (earnings before interest and taxes). The largest number of practitioner views fell into category 3, which can be seen to indicate the crucial significance of interpersonal relationships in business. The respondents explicitly mentioned the importance of the relationship as such, but also referred to overall flexibility, respect, and politeness as necessary elements enabling the relationship. Interestingly, ‘listening’ emerged in a large number of answers; without it, no relationship can be built. The examples that were categorized as referring to business processes and genres mainly described the methods, channels, or strategies that the practitioners use.

Our second set of data, 15 written elaborations on the concept of ‘business knowledge’ by business scholars, was collected particularly for this paper, to validate—or question—the practitioner views described above. The informants here come from the academia and accordingly, look at ‘business knowledge’ from a different vantage point. They base their answers on their own research, projects, and teaching and analyze the concept ‘business knowledge’ within that framework. As the questions we posed were open and invited the respondent to discuss his or her perception, the answers naturally varied a great deal as to the perspective taken and the length of the text. The shortest answer amounted to 27 words and the longest to 582 words, with an average of 148 words.

p.315

Table 25.1 Characteristics of business knowledge as perceived by practitioners

The perceptions of our respondents of the concept ‘business knowledge’ were categorized into the following four perspectives:

1 generic knowledge vs. specific knowledge;

2 knowledge gained from education and research vs. experience and practice;

3 elements of knowledge (= content, what?);

4 knowledge of ways of doing (= behavior, how?).

Within the first perspective, the informants explicated the difference between generic business knowledge and specific, contextually defined knowledge. The former consists of ‘a business mindset’ and elements that are transferrable from one business context to another. Examples given of such knowledge referred to, for example, the basic tenets of accounting and finance practices, and such strategic constructs as Porter’s Five Forces Model and the Balanced Scorecard Framework. The latter type of knowledge is linked to a particular industry or even a particular company. This was explained by, for example, by the significance of the annual key figures in a particular industry, e.g. knowing if a 10 percent profit in this company at this point of time indicates a good performance or not. According to OC2, the specific part also “includes the labels used for speaking about the above, i.e. the company speak and industry slang.”

p.316

The second perspective came out very clearly from our academic informants. They noted that, on the one hand, business knowledge is something that you gain through education and research and, on the other hand, something that is accumulated through work experience. Through education we aim at “understanding how markets work” and through research at “systematically increasing this understanding” (Informant A1). Informant M1 emphasized experience by noting that business knowledge is “tacit knowledge about how markets, organizations and business in general work, how decisions are made and how collaboration is constructed.”

The third perspective refers to the content that the informants found essential in business knowledge. This category was divided into three subcategories as it included the largest number of quotations. First, the informants referred to knowledge in particular areas that make up business knowledge; e.g. “the basics of selling, marketing, production, purchasing, finance, annual accounts, and corporate communication” (Informant F). Also, the skills involved in management and leadership, strategy work, and projects and networks were mentioned, as well as “Core business concepts. Like benchmark, target group, documentation, volatility” (Informant ISM3). Second, overall understanding of how to run a business emerged as essential. This was explained in simple terms by Informant F: “how money comes in to a company and on what it is spent.” Here, profit orientation was mentioned and the goal-oriented mindset that the practitioners had highlighted was evident. It is important to understand the significance of the different business operations for the company and be able to “orchestrate these to serve the purposes of the organization as a whole” (Informant ISM2). Overall, business knowledge refers to an ability to “understand what is important and what is not” (Informant F). The third dimension within this perspective consisted of views that deal with positioning the business in its environment. In other words, it was considered important to understand the company–society interface, to know and follow the prevailing norms and regulations, to be able to recognize new business opportunities that emerge in the environment, and also to understand the rules of ‘fair play.’ Two of our informants discussed the role of values in business knowledge and to some extent questioned the prevailing understanding of (merely) profit driven business. Informant ISM3 noted: “I think that along with profit we should always talk about sustainability—always when a particular solution is evaluated, we should include a measure for sustainability.”

The fourth perspective, knowledge of ways of doing (= behavior, how?), was close to what the practitioners meant by knowledge of “business processes and genres.” Here, business knowledge is knowing how to behave when something has been agreed upon, how to solve problems and how to treat your fellow professionals so that you show respect towards them and their time. The strategic, goal-oriented mindset is the basis of business procedures, on which the industry and company specific behavior patterns are built. In this perspective, we included such comments as “routines and familiar practices” (Informant Mg) and “different fields and industries, cultural environments and organizations (teams etc.) have their own legitimate ways of doing and communicating; learning these often takes a long time” (Informant IB1).

Conclusion

In this chapter, we have examined and analyzed the notion of ‘business knowledge’ as an integral component of the concept of BELF and as the glue that ties the members of the business community of practice (CoP) together. Our aim was to investigate the significance of the ‘B’ in BELF through the perceptions of two related groups: over 200 members of the community (of practice) of internationally operating business practitioners and 15 members of faculty of an international business school. We have elaborated on the notion of business knowledge as a mediating or moderating force at play in BELF communication and demonstrated how business practitioners and scholars conceptualize business knowledge, what they take for granted and consider as tacit knowledge. Our findings make evident the existence and the amount of a complex and multidimensional knowledge base that is embraced by the business community of practice. Since we operated on a fairly high level of abstraction to conceptualize business knowledge, we were able to tap into numerous experiences and interactions of the practitioners but unavoidably lost the rich detail and depth of individual cases, which could be addressed by other methodology such as interview and ethnographic methods, and discourse analysis.

p.317

On the basis of our findings, we argue that business knowledge functions as a common frame of reference that eases—or, indeed, enables—communication in the CoP of (internationally operating) business professionals. Thus, the concept of BELF is needed to make sense of the communication of the community of business professionals with their mutual engagement, joint enterprise and shared repertoire of resources. In what follows, we discuss the question “What does the B stand for?”

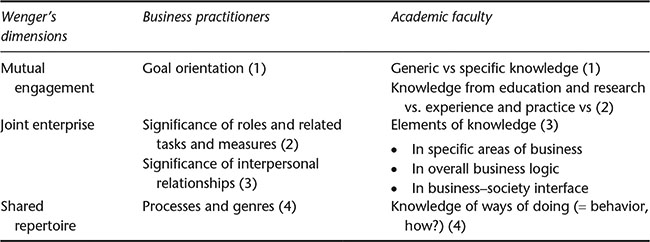

Table 25.2 combines Wenger’s three CoP dimensions with our findings among business practitioners and business scholars.

As can be seen from Table 25.2, our findings based on both practitioners’ and scholars’ perceptions of business knowledge seem to comply with Wenger’s (1998) dimensions of community of practice. Indeed, international business would not be possible without mutual engagement among business practitioners on the general level (for more, see Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989; Holden, 2016). For example, companies could not spread around the globe via cross-border mergers, acquisitions and other business arrangements if they could not rely on being mutually engaged with practitioners with whom they have not had interactions before. Enabling engagement can thus be subtle, as Wenger (1998, p. 74) points out. Our findings indicate that this subtle engagement is enabled on the general level by the conspicuous goal orientation of the practitioners and their understanding of the generic and specific nature of required business knowledge, which has been gained through education and/or practice.

Joint enterprise is manifested in the CoP members’ understanding of the significance of organizational roles, measures of success and interpersonal relationships. Through this understanding, and through the specific elements of knowledge discussed above, they are able to negotiate their response to varying situations in the community. They develop a shared understanding of the issues that enable them to become experienced members of the community who, according to the words of our Informant F, “understand what is important and what is not.” The findings also comply with a number of international business communication and BELF studies in terms of the importance of relationships, politeness, culturally intelligent behavior, listening skills (e.g., Nickerson, 2000; Poncini, 2003; Ehrenreich, 2010b; Kankaanranta & Louhiala-Salminen, 2010; Kankaanranta & Planken, 2010; Louhiala-Salminen & Kankaanranta 2011; Evans, 2013).

Table 25.2 CoP dimensions in relation to the characteristics of and perspectives to business knowledge

p.318

Concretely, a shared repertoire ties CoP members together. Although teams, companies, and industries may have somewhat different routines, activities, documents, and specifications for accomplishing some particular practices, still the members of the overall business community would know the rationale and be able to negotiate their meaning. For example, business practitioners seem to share knowledge of the patterns on what, why, how, and when to communicate in a particular situation. International business communication scholars, in particular, have produced plenty of insights related to the repertoires of communication media and genres (e.g. Louhiala-Salminen, 1997, 2002; Nickerson, 2000; Kankaanranta, 2006; Louhiala-Salminen & Charles, 2006; Kankaanranta & Louhiala-Salminen, 2010).

To conclude, although business dominates many spheres of life today and as consumers we are all automatically involved, it is only the insiders—business practitioners and business faculty—who are in the know. With this study, we have shown what the ‘B’ in BELF stands for, how multifaceted the needed business knowledge is, and why we need the concept of BELF in the first place.

Related chapters in this handbook

2 Baker, English as a Lingua Franca and intercultural communication

3 Ehrenreich, Communities of Practice and English as a lingua franca

29 Cogo, ELF and multilingualism

44 Morán Panero, Global languages and lingua franca communication

Further reading

Angouri, J. (2013). The multilingual reality of the multinational workplace: Language policy and language use. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 34(6), 564–581.

Räisänen, T. (2016). Finnish engineers’ trajectories of socialisation into global working life: From language learners to BELF users and the emergence of a Finnish way of speaking English. In Holmes, P. & Dervin, F. (Eds.) The cultural and intercultural dimensions of English as a lingua franca. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 157–179.

References

Bartlett, C. A., & Ghoshal, S. (1999). Managing across borders: The transnational solution (Vol. 2). Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Cogo, A. (2016). “They all take the risk and make the effort”: Intercultural accommodation and multilingualism in a BELF community of practice. In Lopriore, L. & Grazzi, E. (Eds.) Intercultural communication: New perspectives from ELF. Rome: Roma Tre Press, pp. 364–383.

p.319

Dewey, M. (2010). English as a lingua franca: Heightened variability and theoretical implications. In Mauranen, A. & Ranta, E. (Eds.) English as a lingua franca: Studies and findings. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 60–83.

Du-Babcock. B. (2009). English as a business lingua franca: A framework of integrative approach to future research in international business communication. In Louhiala-Salminen, L. & Kankaanranta, A. (Eds.). The ascent of international business communication, B-109, Helsinki: HSE Print, pp. 45–66. http://hsepubl.lib.hse.fi/FI/publ/hse/b109

Ehrenreich, S. (2010a). English as a lingua franca in multinational corporations: Exploring business communities of practice. In Mauranen, A. & Ranta, E. (Eds.) English as a lingua franca: Studies and findings. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 126–151

Ehrenreich, S. (2010b). English as a business lingua franca in a German multinational corporation: meeting the challenge. Journal of Business Communication, 47(4), pp. 408–431.

Evans, S. (2013). “Just wanna give you guys a bit of an update”: Insider perspectives on business presentations in Hong Kong. English for Specific Purposes, 32(4), pp. 195–207.

Firth, A. (1996). The discursive accomplishment of normality: on “lingua franca” English and conversation analysis. Journal of Pragmatics, 26(2), pp. 237–259.

Gerritsen, M., & Nickerson, C. (2009). BELF: Business English as a lingua franca. The handbook of business discourse. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 180–192

Holden, N. (2016). Economic exchange and the business of language in the ancient world: An exploratory review. In Ginsburgh, V. & Weber, S. (Eds.) The Palgrave handbook of economics and language. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 290–311

Jenkins, J. (2015). Repositioning English and multilingualism in English as a lingua franca. Englishes in Practice, 2(3), pp. 49–85.

Jenkins, J., Cogo, A., & Dewey, M. (2011). Review of developments in research into English as a lingua franca. Language Teaching, 44(3), pp. 281–315.

Kankaanranta, A. (2005). “Hej Seppo, could you pls comment on this!”—internal email communication in lingua franca English in a multinational company. PhD dissertation. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä. http://ebooks.jyu.fi/solki/9513923207.pdf

Kankaanranta, A. (2006). Focus on research: “Hej Seppo, could you pls comment on this!”—Internal email communication in lingua franca English in a multinational company. Business Communication Quarterly, 69, pp. 216–225.

Kankaanranta, A., & Louhiala-Salminen, L. (2010). ”English?—Oh, it’s just work!”: A study of BELF users’ perceptions. English for Specific Purposes, 29, pp. 204–209.

Kankaanranta, A., Louhiala-Salminen, L., & Karhunen, P. (2015). English in multinational companies: Implications for teaching “English” at an international business school. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 4(1), pp. 125–148.

Kankaanranta, A., & Planken, B. (2010). BELF competence as business knowledge of internationally operating business professionals. Journal of Business Communication, 47(4), pp. 380–407.

Krippendorf, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Louhiala-Salminen, L. (1997). Investigating the genre of a business fax: A Finnish case study. Journal of Business Communication, 34(3), pp. 316–333.

Louhiala-Salminen, L. (2002). The fly’s perspective: Discourse in the daily routine of a business manager. English for Specific Purposes, 21(3), pp. 211–231.

Louhiala-Salminen, L., & Charles, M. (2006). English as the lingua franca of international business communication: Whose English? What English. In Palmer-Silveira J., Ruiz-Garrido, M., & Fortanet-Gomez, I. (Eds.) English for international and intercultural business communication. Bern: Peter Lang. pp. 27–54.

Louhiala-Salminen, L., Charles, M., & Kankaanranta, A. (2005). English as a lingua franca in Nordic corporate mergers: Two case companies. English for Specific Purposes, Special issue: English as a lingua franca international business contexts, 24(4), pp. 401–421.

Louhiala-Salminen, L., & Kankaanranta, A. (2011). Professional communication in a global business context: The notion of global communicative competence. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, Special issue on Professional Communication in Global Contexts, 54(3) September, pp. 244–262.

Louhiala-Salminen, L., & Kankaanranta, A. (2012). Language issues in international internal communication: English or local language? If English, what English? Public Relations Review, 38(2), pp. 262–269.

p.320

Nickerson, C. (2000). Playing the corporate language game: An investigation of the genres and discourse strategies in English used by Dutch writers working in multinational corporations. Utrecht studies of language and communication, vol. 15. Amsterdam and Atlanta, GA: Rodopi.

Nonaka, I., Umemoto, K., & Senoo, D. (1996). From information processing to knowledge creation: a paradigm shift in business management. Technology in society, 18(2), pp. 203–218.

Piekkari, R., Welch, D.E., & Welch, L.S. (2014). Language in international business: The multinlingual reality of global business expansion. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Poncini, G. (2003). Multicultural business meetings and the role of languages other than English. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 24(1), pp. 17–32.

Pratt, M.L. (1991). Arts of the contact zone. Profession, pp. 33–40.

Pullin, P. (2010). Small talk, rapport, and international communicative competence lessons to learn from BELF. Journal of Business Communication, 47(4), pp. 455–476.

Pullin Stark, P. (2009). No joke—This is serious! Power, solidarity and humour in business English as a lingua franca (BELF). In Mauranen, A. & Ranta, E. (Eds.) English as a lingua franca: Studies and findings. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 152–177

Seidlhofer, B. (2006). English as a lingua franca and communities of practice. In Volk-Birke, S. & Lippert, J. (Eds.) Anglistentag 2006 Halle proceedings. Trier: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, pp. 307–318

Seidlhofer, B. (2011). Understanding ELF. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Swales, J.M. (1990). Genre analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Wenger, E. 1998. Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambrdige: Cambridge University Press.