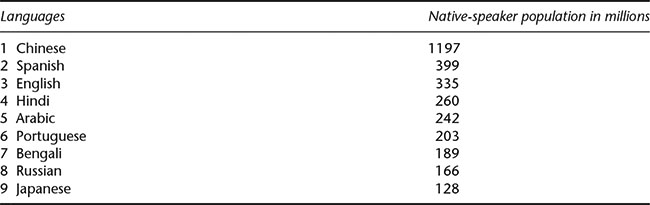

Table 44.1 Example of global languages ranking by L1 population indicator

Source: adapted from Ethnologue’s 2015 figures (Paul, Simons and Fenning, 2015).

p.556

Global languages and lingua franca communication

Sonia Morán Panero

Introduction

The current situation of English in the world is most commonly defined in academia by the unprecedentedness of its global status and functions. Although the world has seen previous lingua francas being used internationally, and although English is not the only set of linguistic resources operating as a lingua franca at present, the degree of global reach achieved by English has not been recorded in any language before (see e.g. Crystal, 1997; Murata and Jenkins, 2009: 1). In ELF studies, as in other academic fields that seek to understand language mobility in an era of globalisation, scholars have sought to critically explore the linguistic, social and theoretical consequences that result from such unprecedented ‘globality’ (Ammon, 2010: 101). This crucial line of enquiry has been largely motivated by the understanding that, in addition to economic and political changes, globalisation processes have led to alterations of major relevance at societal, cultural and linguistic levels as well (see Coupland, 2010; Dewey, 2007; Fairclough, 2006; Giddens, 1999). Not only are some languages seen as global nowadays, but they also play a crucial role in the development of globalisation and they are affected by global processes in significant and unexpected ways. For instance, mobility and interactional patterns have been intensified and complexified by new and faster forms of transport and communication (see Coupland, 2003, 2010; Mar-Molinero, 2010) and as a result, linguistic resources are also being mobilised around the world at unprecedented rates. Deeper levels of interconnectivity are therefore making the interaction between people with different sets of linguistic resources more diverse than ever.

All of these changes are having important sociolinguistic consequences in terms of how we use, value or label ways of speaking, in terms of the different multiple groups with which we may (wish/be able to) be affiliated, and in terms of the different ways in which we may perform new and old identities (e.g. Pennycook, 2007; Otsuji and Pennycook, 2010). Unsurprisingly, the context of a globalised world where transcultural communication is especially evident has highlighted scholars’ need to understand the evolving landscape of language use at global as well as local levels. Of course, academic scrutiny has not only been restricted to the study of the globality of English. Other world languages such as Arabic, Chinese, Portuguese or Spanish have also been largely recognised as worthy of the global label. The evolution of each of these global languages, the roles or functions they perform, and the impact of their international spread are also being closely analysed in academia (see, e.g., Mar-Molinero, 2010 on Spanish; Paulo and Moita-Lopes, 2015 for accounts of Portuguese; Tsung and Cruickshank, 2010 on Chinese; and Versteegh, 2015 on Arabic). In addition to the relevance and value attached to the global status and international prestige of isolated languages (i.e. socially bounded and labelled sets of linguistic resources), a great deal of attention has been put by scholars, governments, international organisations, language authorities, educational institutions and the general public to examining how these languages interact with and/or influence each other. As Maurais and Morris (2003) point out, further global integration and interconnectedness have highlighted the perceived need for further ‘direct’ communication (i.e. through the ‘same’ language), and seem to have fostered a continuous and dynamic relation of competition between languages to fulfil a lingua franca function across international borders. Thus, a task of high importance for language experts and non-experts alike seems to be the prediction of which language, languages or what medium or mode will cover the need for global lingua franca communication in a short- and/or long-term future.

p.557

This chapter seeks to examine the benefits, challenges and potential blind spots that emerge from the identification and study of global languages as well as from attempts to describe, quantify and predict which linguistic resources are or will be fulfilling an international lingua franca function. I begin by critically reviewing the indicators that are usually examined to classify and rank the global status of world languages, and briefly consider some of the reasons for which being able to attribute globality and a lingua franca function to some resources seems to be highly valued. Then, I reflect on how different academic approaches to the study of language in a context of globalisation influence the representations and analysis that we construct of the globality of English and other world languages, and consider how these approaches have informed (and/or are being informed by) different waves of ELF studies. Throughout the article I also discuss the importance that analysing (changing) ideas, evaluations and theorisations of language can have as part of such descriptive and predictive endeavours, even though these aspects have not always been held as significant indicators.

The globality of world languages: (how) can we tell?

There seems to be a great deal of consensus among scholars on the most significant indicators to study when wishing to establish whether a language may currently be conceived as ‘global’, how global in comparison with other languages, in relation to which functions and domains and when trying to predict whether the language will continue to be so in a foreseeable future (e.g. Ammon, 2010; Crystal, 2008; Graddol, 2006). Demographic information such as the present and future population size of the speakers of a language, their migratory movements, or their distribution are among the most well-known measures for the global status of a language. However, even if estimated numbers of different groups of speakers are available (e.g. ‘native’, ‘second’, and/or ‘non-native/foreign’), these do not necessarily work as evidence of international language use, and they do not seem to tell us much about the functions, prestige and values that may be ascribed to such languages. Thus, the political and/or legal status that a language has in different countries, supranational organisations and multinational companies, is also seen as a useful indicator and predictor (e.g. official and working status). Equally relevant is establishing the degree of presence, promotion and maintenance that a world language enjoys in international domains such as scientific/academic ones, as well as for technological, internet, or media use and other forms of cultural production (see Mar-Molinero, 2008 on Spanish-speaking music and television outputs). Of course, the economic status of the countries, institutions and/or multinationals where the language is spoken and/or studied are also significant (e.g. Gross Domestic Product calculations of native and second-language speakers). As Ammon (2010) points out, economic strength may make a language seem more attractive to prospective learners even if comparatively it has smaller numerical strength. Perhaps the economic strength indicator may also point to the amount of resources and power that can be deployed to further promote a language in international spheres.

p.558

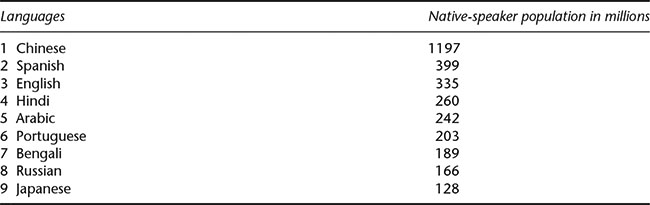

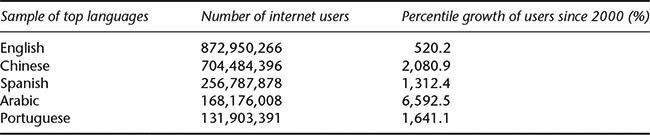

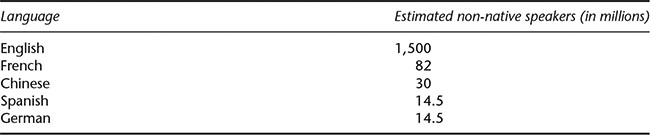

It is clear that analysing these indicators requires different forms of quantification and categorisation. Counting not only applies to speakers, it is also required to produce numbers of spaces in which a language is spoken officially, to number its scientific publications or to establish in how many schools it is used for instruction. The resulting figures are often organised in the form of rankings (see Tables 44.1, 44.2 and 44.3), and are generally assigned high degrees of relevance. For instance, the data published by Ethnologue (e.g. Paul, Simons and Fennig, 2015) is often cited as a widely respected source of global languages ranking in academia. States, governments and a variety of organisations (e.g. language academies, educational and/or research institutions) also follow the movement of ranking positions over time, and may use them to inform their language policies or to guide decisions on the cost of their linguistic investments. As these rankings are increasingly blogged about, shared and commented on by social media users (e.g. Lucas López’s 2015 infographic for the South China Morning Post), it is clear that such quantitative data also seems to have currency and recognition outside experts and linguists’ circles.

Table 44.1 Example of global languages ranking by L1 population indicator

Source: adapted from Ethnologue’s 2015 figures (Paul, Simons and Fenning, 2015).

Table 44.2 Example of global languages ranking by internet users

Source: adapted from 2015 data published at www.internetworldstats.com/stats7.htm (accessed 15 January 2016).

p.559

Table 44.3 Example of rankings by estimated figures of non-native speaker ‘learners’

Source: adapted from Ammon, 2010; Crystal, 2008; Lucas López, 2015.

Overall, the indicators that show the lingua franca function of a language (i.e. communication in a language that is classifiable as ‘additional’ or ‘foreign’ for at least some of the speakers involved) seem to be achieving the highest value among the variety of measurements that can determine the globality of a language. For instance, Ammon (2010: 101–102) distinguishes between ‘global status’ (i.e. geographical spread of speakers and status) and ‘global function’ (i.e. use for global communication) as two different aspects of the globality of a language, and prioritises the latter as a measure that allows us to define a language as being ‘more’ global or international than another. He illustrates his point by suggesting that while Spanish enjoys a similar global status to English, its global function is considerably lower. The author even suggests that

a lingua franca which extends over several languages [i.e. a lingua franca that is used among non-native speakers] can be given more weight than a language of bilateral asymmetric use [i.e. a lingua franca that is mainly used between native and non-native speakers], and that this is what distinguishes English most noticeably from other languages.

(Ammon, 2010: 103, emphasis added)

Other linguistic resources, whether neatly bounded and labelled as ‘global languages’ or not, are of course used for lingua franca communication as well. Nevertheless, scholars normally specify that these resources are restricted to specific regional or supranational areas and to a narrower range of domains. Godenzzi (2006), for example, identifies four different types of contexts in which Spanish is used as a lingua franca. These include lingua franca interactions with/between speakers of different creoles and indigenous languages in Spanish-speaking contexts, interactions in borderlands or contact areas with other languages such as in Brazil or the Amazonian Forests, bilingual education systems, and interactions with transnational migrants (e.g. tourists) and other global uses (e.g. international commerce collaborations in MERCOSUR). Therefore, Spanish as a lingua franca or ‘SLF’ interactions seem to be taking place on a rather smaller scale still.

Although, as Ammon (2010: 208) observes, the number of additional/lingua franca speakers is on the rise for Spanish, Chinese, Japanese and possibly for Arabic and Portuguese too, English is still championed, at least for now, as the language with the highest degree of global function. In fact, if we abandon conventional understandings of what may count as a ‘native speaker’, English would actually lead all indicators measuring the globality of a language. It is then not surprising that most academic predictions on the future global linguistic landscape of the twenty-first century (or at least its first half), still concur with Graddol’s (2006) suggestions that English will maintain its predominant position, while also experiencing more pressure from the growing importance of Chinese, Spanish and possibly also Russian, Hindi and Portuguese. Although so far this projection seems to hold, commentators warn us of the potential long-term effects that may emerge from unexpected economic and socio-political turns such as the global 2008/2009 economic crisis (Ammon, 2010; Pennycook, 2010), austerity cuts in many parts of the world (Coupland, 2010), the slow down and potential stagnation of the Chinese economy, the apparent upsurge of regional retreat (e.g. Catalan and Scottish nationalisms, Brexit) or the recent growth in visibility of xenophobic attitudes, at least in Europe and the USA. As Jenkins rightly puts it (2009: 234), ‘you can probably do little more than make educated guesses in relation to some of these issues . . . and wait and see what happens’.

p.560

In addition to the uncertainty of predictions, the actual description and classification of global languages at present are also anything but problem free. The shortcomings of these quantifications are manifold and have been pointed out by numerous scholars on multiple occasions (e.g. Busch, 2016; Pennycook, 2010; 2012). To begin with, censuses are not always able to capture unofficial information. For instance, some census may report on the linguistic repertoires of citizens in a country, but have no information on legal or illegal immigrants. Also, distinctions between the actual use of ‘official’, ‘working’ and/or ‘de facto’ languages are not always adequately reflected. Another major issue is the categorisation of speakers and the subjective and controversial decision-making and boundary-setting that lie behind such categorisations. Studies on the use of English as a lingua franca and of other global languages show that classifications of ‘L1’, ‘L2’, ‘foreign’, ‘native’ or ‘non-native’ speakers are difficult to make, and many have questioned the representability, reliability and usefulness of such constructs (see Busch, 2016 for a critical deconstruction of category-making processes in statistical offices and the ideological assumptions reproduced in such categories). For instance, whether a speaker may be considered a (foreign/additional language) ‘user’ or a ‘learner’ by an observer may not be that informative, given that, there is no objective way of drawing a line between the two social constructs. Establishing standard ways of assigning this label would not make it more representative, given the multiple ways in which different users may conceive and label themselves and their own use.

Similarly, the ranked languages seem to be neatly separated and ‘boxed up’, but even deciding what counts as ‘English’, ‘Chinese’ or ‘Spanish’ use is difficult to establish. For instance, in order to represent the use of world languages online, some kind of decision has to be made on whether variations from idealised standards, perceived ‘errors’, or the ‘mix’ of multilingual/hybrid resources often found in informal social media platforms, count towards the use of one specific or various languages. A well-known example of translanguaging phenomena that would be difficult to classify is ‘parquear la troca’ – a series of linguistic resources used to say ‘parking the truck’ that are often labelled as ‘Spanglish’ and that linguists would normally dissect as a ‘mix’ between and adaptation of English and Spanish morphemes. Thus, placing boundaries around the language use that is included in or excluded from the rankings, and establishing who has the right to make that decision, are all highly controversial.

The difficulty in representing different ways of thinking about what constitutes a language puts in sharp relief the risks of uncritically taking the estimates of these rankings to support scholarly claims or predictions on the spread of different sets of linguistic resources (see Pennycook, 2012 for a scholarly discussion on Chinese, English and different modes of thinking about language in the Western and Eastern world). But, if painting an accurate picture of the world’s current global languages and their lingua franca use is that difficult – if not impossible – if our best rankings only offer relative, distorted and partial results and if predicting the future of language is mainly a ‘speculative business’ (Pennycook, 2010: 677), we may be left wondering why governments, language and/or research institutions fund the production of such statistics, why they seem to inform policy-making, or even why we write book chapters, articles and even monographs in academia about the global status and function of world languages.

p.561

Global languages and lingua francas: (why) do they matter?

The globality and international prestige of different labelled languages continues to be a relevant and polemic feature for a variety of reasons. For instance, large or global languages are thought to have a higher communicative value for the reason that those languages can be used with a higher number of speakers (De Swaan, 2001; 2010). In turn, this value is thought to work as a self-expanding force, attracting more prospective language learners. For similar reasons, global languages are thought to grant access to global markets and to foster business competitiveness (Heller, 2010). As Blommaert (2010 :12) suggests, ‘bits’ of global languages such as idealised accents or standards, are often associated with promises of social, scalar or territorial mobility as well as with a variety of identification possibilities. On the whole, practices of value and meaning attribution of this sort can have significant consequences for individuals, institutions and other forms of social organisation. Heller (2010: 359) puts it well when she suggests that:

[i]ndividuals worry about what kind of linguistic repertoire they need in order for them or their children to profit from current conditions, and states worry about whether their citizens have the language skills they need in order to function under those conditions.

In other words, global languages can work as gatekeepers to a series of opportunities, goals or life-trajectories. While acquiring global languages is expected to open up mobility, and transfer value and prestige to the speakers and institutions that know and/or use them, this apparent benefit may clash with other local and/or global interests. These clashes may include the perceived curtailment of the domains of local languages, perceptions of power asymmetries, or the emergence of tensions between notions of what national/regional/speech community identity is and how it ties in with language use and the shape of people’s linguistic repertoires. In addition to concerns over the need to acquire or provide access to linguistic resources thought to be necessary to succeed in a global world, interest in the globality of a particular language may also come from desires of promoting its spread for private and/or national gain. As Ammon (2010: 120) argues, promoting a country’s own mother tongue internationally is highly cherished by nation-states because of the belief that ‘knowledge of one’s own language abroad enhances the diffusion of one’s own values and favourable attitudes towards one’s own country, and consequently helps to improve economic and other international relationships’. In fact, the actual process of encouraging the learning of a language globally can result in economic profits in itself for the organisations behind its promotion (see e.g. Heller, 2003 on the commodification of French).

Overall, predictions over which language(s) will be the global communicative mode of the future can be useful, in theory, for individuals and states with economic and organisational resources to plan which linguistic investment may be more fructiferous in the long-term (e.g. which ‘foreign’ languages to learn/teach, if any). Institutions behind the active promotion of international languages (e.g. Instituto Cervantes) might also find them helpful to design or rethink their commodification and expansion strategies. These predictions could even inform the future plans of action of groups concerned with the protection of language diversity and multilingualism, or groups with fears of perceived ‘lack of fairness . . . in communication . . . but also in establishing international relations’ (Ammon, 2010: 120). Perhaps more importantly, in creating and discussing ‘futuribles’ (i.e. possible future scenarios), we may also be intentionally or inadvertently creating discourses that influence language users and their learning choices, and we may ultimately affect forthcoming linguistic developments (see De Swaan, 2010; Fairclough, 2006) – although influencing discourses are likely to be multiple, variable, mutually contradictory and of unpredictable effects.

p.562

In addition to the observed rivalry between labelled sets of resources, the idea that global languages can provide access to certain opportunities also fosters tensions ‘within’ them, that is, struggles over who is more qualified to produce, teach and distribute them, over who gets to decide what counts as ‘good’ or ‘legitimate’ language use, and therefore over who gets to control or exert power on the present and future form of a particular language (see e.g. Gal, 2013; Heller, 2003; 2010: 358). On the one hand, different institutions or individuals may compete to act as linguistic authorities and to control processes of standardisation and top-down prescription that dictate how a language should be used and learned, and what counts as valuable and ‘authentic’ use. On the other hand, these authorities are constantly being contested by language users themselves. As Heller (2010) reminds us, this contestation may take place through the development of actual explicit discourses of resistance (e.g. discourses on language rights, challenges to native-speaker ideology identified in ELF research) and/or through variable, hybrid and unexpected linguistic practices that vary from prescribed standards and/or beliefs about correct language use (see Blommaert, 2010 on polycentricity of perceived authorities).

In order to capture and understand concerns, interests and social, symbolic or linguistic consequences of this kind in depth, it is necessary to look at the global spread and use of linguistic resources from perspectives that go beyond counting and ranking (Coupland, 2010; Pennycook, 2012). In other words, it is necessary to seek qualitative insights of contextual use and interpretation, and to consider emerging social, linguistic and discursive practices around global linguistic resources. As I explain next, this realisation is what has driven research undertaken across different waves of ELF studies, as well as other approaches to translingual and transcultural flows. This body of work has not only helped problematise some of the measurements typically used to assign globality to world languages – among other language constructs and categorisations (see e.g. Cogo and Dewey, 2012) – it is also urging scholars to reconsider the ways in which language and linguistic boundaries are treated to make descriptions and predictions of the global linguistic landscape, in academia and in language education at large.

From global languages to sociolinguistic and multilingual resources: furthering the descriptive and predictive challenge

Despite the complex problems involved in the ranking practices introduced so far, these forms of quantification have inspired scholars to develop theoretical frameworks for the study of language in a global context. A widely known example is De Swaan’s (2001, 2010) language systems framework, and similar approaches that have also maintained metaphors of ecology dynamics and language constellations. De Swaan introduces a hierarchical typology of languages based on the numbers of speakers and functions that particular languages have in specific constellations or geographical spaces (i.e. ‘peripheral’ languages at the bottom, connected by ‘central’ languages, followed by ‘supercentral’ languages, and with English at the top as the ‘hypercentral’ language of global communication). De Swaan intended to provide a macroscopic framework that explains how 6,000 groups of language speakers are connected globally through multilingualism and lingua franca communication. The typology also seeks to explain how varying numbers of speakers, together with largely shared expectations about the utility or communicative value of particular linguistic resources, can affect the vitality of the different world languages composing the global system. According to De Swaan, the dynamics in this system tend to boost languages at the top of the pyramid because of their higher communicative possibilities, thus threatening the world’s linguistic diversity and cultural capital (e.g. English is compared to a black hole that ‘devours’ all languages it comes in contact with).

p.563

Quantifications, classifications and metaphors of this sort have been influential, to different extents, in much research on the study of global languages. For instance, the realisation that non-native speakers of English had largely outnumbered native speakers, and claims over English functioning as the international medium of communication per excellence, were often cited by scholars in the initial stages of ELF studies as a motivation for the careful and empirical investigation of the use of English as a lingua franca (e.g. Jenkins, 2000: 1). In fact, more than 10 years later, the hypercentrality of English is still being invoked in some ELF publications (e.g. Hülmbauer and Seidlhofer, 2013), to justify the appropriateness of ‘putting the main focus of a research task specifically on the use of English rather than any other language as a lingua franca’ (p. 391).

Although De Swaan’s framework engages critically with complex matters of choice, expectations and power inequalities, therefore emphasising the need to understand the dynamics between global languages ‘as inherently political’ (Blommaert, 2010: 18), such top-down approaches have also been heavily criticised (see e.g. Heller, 2010). Frameworks on global languages systems have been accused of providing acontextual and ahistorical generalisations, and therefore of failing to address the ‘detail, contradiction and complexity’ (Blommaert, 2010: 18) that characterise the mobilisation or flows of linguistic resources through geographical, indexical and social spaces. In other words, there seems to be a lack of empirical explorations on which agents are involved in actual processes of change, how and with what specific effects. It also seems to me that, while a great deal of weight is granted to seemingly rational decision-making based on the communicative value of languages, sufficient attention is not given to the exploitable potential that ‘non-native’ users of a super/hypercentral language may have to perform functions that go beyond referential meaning exchange (see Baker, 2011 on how ELF communication is neither culture- or identity-free). Thus, the frameworks do not appear to consider how this potential may affect value assignation patterns at local levels of interaction or how they may influence speakers’ decision-making on which languages to invest in.

Top-down approaches have also been criticised for favouring a focus on ‘whole’ languages and neglecting to examine the spread of genres, styles and registers, perceived accents or idealised standard forms, for relying on dubious language labelling and speaker categorisations, and for reproducing nationalistic associations between nations, languages and cultures in the ecologically framed treatments of language death. As Coupland (2010: 10) puts it, distributional sociolinguistic accounts of global languages seem to have operated with understandings of linguistic flows ‘as transference – as movement of codes and people across predefined and unchanging boundaries – rather than in terms of transformation and transcendence’. As a result, crucial developments of language such as ‘hybrid’ or superdiverse uses, the meshing of linguistic resources in multilingual repertoires, the potential re-semiotisation, re-valorisation and variation of linguistic resources as they are re-embedded into different contexts of use, and/or the transformation of the varying contexts in which they are re-embedded, are left unexplained in these frameworks.

p.564

Although speaker quantifications and distributional approaches to global languages as separate bounded units have informed ELF studies, the field has – also from its initial stages – moved beyond, and sought to empirically address most, if not all, of the gaps outlined in the previous paragraph. As Dewey (2007) explains, ELF studies also take a transformationalist approach (see Held, McGrew, Goldblatt and Perraton, 1999) to the study of language globalisation. For instance, the first wave of ELF studies (i.e. ‘ELF1’ in Jenkins, 2015) was mainly concerned with exploring the transformation of English linguistic form. The second wave of ELF studies (i.e. ‘ELF2’ in Jenkins, 2015) sought to explore and understand the sociolinguistic and pragmatic functions that motivate the linguistic sameness and variability that are observed in ELF interactions, therefore also investigating which kind of re-valorisations, referential and social meaning changes, and identificational possibilities could be performed by all English users in ELF interactions and in what ways (e.g. Baker, 2011; Kalocsai, 2014; Kitazawa, 2013).

It is by now clear that the way in which scholars explore language in a context of globalisation has varied and diversified over time. The analysis of actual use in local contexts seems to be forcing us to reconsider the approaches and frameworks with which we try to describe and explain global languages and translocal linguistic flows, and they are even leading us to question the adequacy of looking at languages as isolated, autonomous, bounded entities. A growing body of scholars supports conceptualisations of language as emergent social practice instead (e.g. Baird, Baker and Kitazawa, 2014; Jenkins, 2015; Pennycook, 2007, 2010, 2012), and some advocate for focusing on linguistic resources instead of languages, and understanding these resources as a set of semiotic signs through which people construct referential and social meanings (e.g. Blommaert’s 2010 sociolinguistics of mobile resources). From this perspective, both languages and boundaries between them are seen as ideological constructs, but constructs with ‘real’ social and communicative consequences and therefore constructs that still need to be attended to (e.g. Canagarajah, 2013).

By not making already fixed boundaries between languages the starting point of our descriptive and predictive efforts, we reduce the risk of excluding linguistic uses that do not necessarily fit with pre-existing ideas, categories and labels from our data analysis. Also, by not reducing our attention solely to the evolution and/or loss of fixed, bounded, labelled languages (e.g. language decay, death), we will be better prepared to record and explain emergent linguistic and labelling practices that may not have been granted official recognition yet or which may never achieve it, but which still play a significant role in language use at local and or global levels (e.g. Spanglish practices mentioned earlier). As Otsuji and Pennycook (2010) evidence with their ‘metrolingualism’ approach, from this position we are able to see how old and new labels, boundaries, identity and/or cultural relations may be (re)created in (meta)linguistic practice.

Once more, the opportunities, consequences and challenges that the study of mobile linguistic resources has for academic practice, as opposed to the study of bounded languages or codes, are also being addressed by ELF scholars. This is especially the case within what Jenkins’ (2015) identifies as the third wave of ELF studies or ‘ELF3’. Jenkins spells out the need to re-theorise ELF studies in a way that truly reflects the maxim that ‘ELF is a multilingual practice and research should . . . explore how ELF’s multilingualism is enacted in different kinds of interactions’ (2015: 63). While similar observations about ELF’s multilingualism had been brought up before, Jenkins’ point is that its implications had not been fully integrated into ELF theorising or in the analytic and interpretative practices of its researchers. For instance, the author argues that in ELF2 the focus had been maintained on resources that we call ‘English’, while relegating other multilingual resources to the periphery. Thus, Jenkins urges us to better conceptualise the constant presence or influence that other languages have in ELF interactions, hence going beyond notions of code-switching or L1-transfer.

p.565

It seems to me that the implications of consistently treating ELF as multi-/trans-lingual practice would require a clearer ontology of boundaries between linguistic resources than what has been offered before. For instance, a well-defined conceptualisation of boundaries would be necessary to theorise further the interaction (i.e. ‘leakage’ or ‘flow’ in Jenkins, 2015: 75) that takes place between different sets of linguistic resources in ELF interaction, and to theorise what it is that we understand by speakers’ multilingual ‘repertoires-in-flux’ (p. 76). While concerns over establishing boundaries and ascribing labels have already been voiced in ELF literature, so far there seems to have been a certain degree of theoretical ambiguity around them. For example, Hülmbauer and Seidlhofer (2013: 399) indicate that ‘language forms are no longer clearly assignable to a particular code when they emerge from the dynamics of intercultural encounters’, a point that I believe can have implications for the terminology we use ourselves when attempting to explain the social phenomena we study. Nevertheless, it is not clear whether these authors maintain that such codes do not exist outside the realm of ideology construction or whether they hold that there are virtual codes, but we just cannot be sure of which code is influencing which in the performance observed (see Vetchinnikova 2015 for a discussion of the incompatibility between ‘usage-based’ and ‘virtual language/code’ ontologies of language).

Jenkins explicitly stated the need to address this ambiguity in ELF3, when she reminded us that ‘the extent to which it is possible to identify “any boundaries” between languages is open to empirical investigation and further debate’ (Jenkins, 2015: 68). I propose that, in order to do this, we need to understand how speakers themselves conceptualise language boundaries and multilingualism (e.g. as added monolingualism, or as translanguaging), and their role in ELF. Although much ELF research has explored users’ perceptions and evaluations of linguistic resources that usually fall under the label of ‘English’, we need a better understanding of how users of English as a lingua franca draw boundaries and assign new and/or old labels to linguistic resources themselves. In addition, we need to understand what kind of ideological work is done through such labelling practices, for what pragmatic and communicative purposes and with what social effects (Morán Panero, 2016).

The reasons that would motivate us to carefully examine users’ own labelling and boundary-drawing practices are several. First, as linguistic anthropology and indexicality scholars argue, it is through metalinguistic, ideological or discursive practices that we give shape to linguistic resources or semiotic signs, and turn them or ‘sediment’ them into different labelled languages, varieties, dialects, accents or any other perceived collective ways of speaking (see e.g. Irvine and Gal, 2000; Johnstone, 2010). If we take language boundaries to be ideological constructions that emerge from people’s ideas and discourses, it seems necessary to look at the processes of conceptualisation and metalinguistic practices in which speakers engage to constitute, challenge or modify such boundaries. Also, from this perspective there seems to be no principled reason for which linguists’ labelling practices may be more legitimate to explain social phenomena than users’ own. As I have shown before (Morán Panero, 2016), knowing how users apply labels and boundaries may actually be crucial to avoid essentialising tendencies in our research; that is, we need to avoid the risk of imposing our fixed notions to interpret data and to draw conclusions, if they do not correspond with those of our participants or do not represent them consistently (see e.g. Baker, 2013 for a discussion on essentialising treatments of cultures).

p.566

Finally, if we see ideas and ideologies about language as influential resources that form part of our sociolinguistic repertoires (Blommaert, 2010: 102), it is necessary to examine the role that users’ understandings of language, multilingualism and language boundaries can have in actual linguistic developments. Ammon (2010), for instance, reminds us that ideas and attitudes towards what ‘linguistic fairness’ may mean in international communication can have a great impact on regulation and promotion of certain linguistic uses. The same goes, he adds, for positions on how identity relates or should relate to language use, ideas about the cost or value of multilingualism, and general beliefs on perceived rules of communication and interaction (e.g. speaking a client’s language for a business transaction, or whether translanguaging practices are acceptable or not in formal encounters). As Pennycook (2010: 675) rightly emphasises, in our descriptive and predictive efforts ‘we need to think not only in terms of the ways languages reflect the political economy, but also in terms of the language ideologies that underpin our ways of thinking about language’.

Conclusion

In this chapter I have discussed two main approaches in the study of labelled global languages and lingua franca communication, and I have shown how the field of ELF studies has been moving from working with metaphors of pluralisation of varieties and languages to the study of linguistic and sociolinguistic resources as social and multilingual practice. I have argued that one of the main future challenges that we face in the description and prediction of English as a multilingua franca (and potentially other multilingua francas where English resources are not available) is incorporating the implications of a clear ontology of boundaries between languages to our academic practice. This ontology should inform the theorisations and terminology we produce (e.g. language ‘leaking’ in multilingual repertoires), the methodologies that we design to collect and analyse data (see also Cogo, 2016) and the research interpretations and conclusions that we draw. In particular, I have emphasised that, if the starting point in ELF3 is that ‘mixed language is normative’ (Jenkins, 2015: 68), we need to explore how this works at ideological and indexical levels for language users. As labelling and boundary-drawing practices are variably applied by different language users, and even from moment to moment by the same speaker (e.g. Morán Panero, 2016), we need to understand the pragmatic intentions and effects that they may serve, and critically reflect on the extent to which it may be justified to prioritise linguists’ conceptualisations of languages and their boundaries, when these do not correspond to the ones held by our own research participants. Finally, if the goal in ELF3 is to avoid giving more centrality to English than to the multi-/trans-lingual nature of ELF, it may be necessary to rethink the validity of claims about English having more ‘weight’ in global rankings because of its lingua franca function, and thus rethink the usefulness of attempting to quantify which labelled languages are used as lingua francas on the whole. In order to treat ELF as multilingual practice, we may even need to examine the adequacy of reproducing the idea that ‘English’ is the most widely used lingua franca (see Pennycook, 2012 on a discussion of how this claim could be a ‘truism’) as a motivator for ELF studies in our writing.

p.567

Related chapters in this handbook

24 Kimura and Canagarajah, Translingual practice and ELF

29 Cogo, ELF and multilingualism

42 Baird and Baird, English as a lingua franca: changing ‘attitudes’

47 Jenkins, The future of ELF?

Further reading

Blommaert, J.M.E. (2010). The Sociolinguistics of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Coupland, N. (ed.) (2010). Handbook of Language and Globalization. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Jenkins, J. (2015). Repositioning English and multilingualism in English as a lingua franca. Englishes in Practice, 2(3), pp.49–85.

Maurais, J. and Morris, M.A. (2003). Languages in a Globalising World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rubdy, R. and Alsagoff, L. (2013) (eds), The Global–Local Interface and Hybridity. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

References

Ammon, U. (2010). The concept of world language: ranks and degrees. In Coupland, N. (ed.) The Handbook of Language and Globalization. Malden, MA and Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, pp.101–122.

Baird R., Baker, W. and Kitazawa, M. (2014). The complexity of ELF. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca 3(1), pp.171–196.

Baker, W. (2011). Culture and identity through ELF in Asia: fact or fiction? In Archibald, A. Cogo, A. and Jenkins, J. (eds) Latest Trends in ELF Research. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp.35–55.

Baker, W. (2013). Interpreting the culture in intercultural rhetoric: a critical perspective from English as a lingua franca studies. In Belcher, D. and Nelson, G. (eds) Critical and Corpus-Based Approaches to Intercultural Rhetoric. Ann Arbor, MA: The University of Michigan Press, pp.22–45.

Blommaert, J.M.E. (2010). The Sociolinguistics of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Busch, B. (2016). Categorising languages and speakers: why linguists should mistrust census data and statistics. Working Papers in Urban Language and Literacies, 189, pp.1–18.

Canagarajah, S. (2013). Translingual Practice. London: Routledge.

Cogo, A. (2016). Repertoires and boundaries: questionning multilingualism in ELF. Paper presented at the 9th International Conference of English as a Lingua Franca, Lleida, 27–29 June 2016.

Cogo, A. and Dewey, M. 2012. Analysing English as a Lingua Franca: A Corpus-driven Investigation. London: Continuum.

Coupland, N. (2003). Introduction: sociolinguistics and globalisation, Journal of Sociolinguistics, 7(4), pp.465–473.

Coupland, N. (2010). Introduction: sociolinguistics in the global era. In Coupland, N. (ed.) Handbook of Language and Globalization. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, pp.1–27.

Crystal, D. (1997). English as a Global Language, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crystal, D. (2008) Two thousand million? English Today, 24(1), pp.3–6.

De Swaan, A. (2001). The World Language System; A Political Sociology and Political Economy of Language. Cambridge: Polity Press.

De Swaan, A. (2010). Language systems. In Coupland, N. (ed.) Handbook of Language and Globalization. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, pp.56–76.

Dewey, M. (2007). ‘English as a lingua franca and globalisation: an interconnected perspective’. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 17(3), pp.332–353.

Fairclough, N. (2006). Language and Globalisation, London: Routledge.

p.568

Gal, S. (2013). A linguistic anthropologist looks at English as a lingua franca. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 2(1), pp.177–183.

Giddens, (1999). The Consequences of Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press

Godenzzi, J. (2006). Spanish as a lingua franca. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 26, pp.100–122.

Graddol, D. (2006). English next: why Global English may mean the end of English as a foreign language. London: British Council, available at: www.britishcouncil.org/learning-research (accessed August 2015).

Held, D. McGrew, A. Goldblatt, D. and Perraton, J. (1999). Global Transformations: Politics, Economics and Culture. Cambridge: Blackwell.

Heller, M. (2003). Globalization, the new economy, and the commodification of language and identity. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 7(4), pp.473–492.

Heller, M. (2010). Language as a resource in the new globalised economy. In Coupland, N. (ed.) Handbook of Language and Globalization. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, pp.349–365.

Hülmbauer, C. and Seidlhofer, B. (2013). English as a lingua franca in European multilingualism. In Berthand, A. Grin, F. and Liidi, G. (eds) Exploring the dynamics of multilingualism: the DYLAN Project. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp.378–406.

Irvine, J. and Gal, S. (2000). Language ideology and linguistic differentiation. In Kroskity, P. V. (ed.) Regimes of Language: Language Ideologies, Polities, and Identities. New Mexico: School for American Research Press, pp.35–79.

Jenkins. J. (2000). The Phonology of English as an International Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jenkins, J. (2009). World Englishes: A Resource Book for Students. London: Routledge.

Jenkins, J. (2015). Repositioning English and multilingualism in English as a lingua franca. Englishes in Practice, 2(3), pp.49–85.

Johnstone, B. (2010). Indexing the local. In Coupland, N. (ed.) Handbook of Language and Globalization. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, pp.386–405.

Kalocsai, K. (2014). Communities of Practice and English as a Lingua Franca. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

Kitazawa, M. (2013). Approaching Conceptualisations of English in East Asian Contexts: Ideas, Ideology, and Identification. Unpublished doctoral thesis. University of Southampton.

Lucas López, A. (2015). Infographics: A world of languages. South China Morning Post. www.scmp.com/infographics/article/1810040/infographic-world-languages?page=all (accessed November 2015).

Mar-Molinero, C. (2008). Subverting Cervantes: language authority in global Spanish. International Multilingual Research Journal, 2(1), pp.27–47.

Mar-Molinero, C. 2010. The spread of global Spanish: from Cervantes to reggaetón. In Coupland, N. (ed.) The Handbook of Language and Globalization. Malden, MA and Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, pp.162–181.

Maurais, J. and Morris, M.A. (2003). Languages in a Globalising World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Morán Panero, S. (2016). Multilingualism, boundaries and labelling-practices: exploring speakers’ perspectives. Paper presented at the 9th International Conference of English as a Lingua Franca, Lleida, 27–29 June 2016.

Murata, K. and Jenkins, J. (2009). Global Englishes in Asian Contexts: Current and Future Developments. London: Palgrave Macmillan

Otsuji, E. and Pennycook, A. (2010) Metrolingualism: fixity, fluidity and language in flux. International Journal of Multilingualism, 7(3) pp.240–254.

Paul, L.P., Simons, G.F. and Fennig, C.D. (eds) 2015. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Eighteenth edition. Dallas, TX: SIL International. www.ethnologue.com [accessed: November, 2015].

Paulo, L. and Moita-Lopes (2015). Global Portuguese: Linguistic Ideologies in Late Modernity. Abingdon: Routledge.

Pennycook, A. (2007). Global Englishes and Transcultural Flows. Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

Pennycook, A. (2010). The future of Englishes: one, many or none? In. Kirkpatrick, A. (ed.) The Routledge Handbook of World Englishes. Abingdon: Routledge, pp.637–687.

p.569

Pennycook, A. (2012) Lingua francas as language ideologies. In Kirkpatrick, A. and Sussex, R. (eds) English as an International Language in Asia: Implications for Language Education. London: Springer, pp.137–154.

Tsung, L and Cruickshank, K. (eds) (2010). Teaching and Learning Chinese in Global Contexts. London: Continuum International.

Versteegh, K. (2015). An empire of learning: Arabic as a global language. In Stolz, C. (ed.) Language Empires in Comparative Perspective. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp.41–54.

Vetchinnikova, S. (2015). Usage-based recycling or creative exploitation of the shared code? The case of phraseological patterning. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca 4(2), pp.223–252.