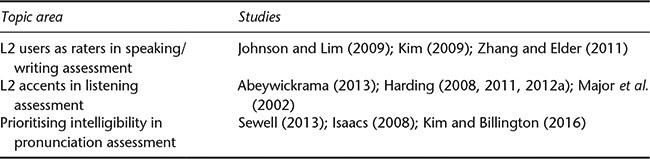

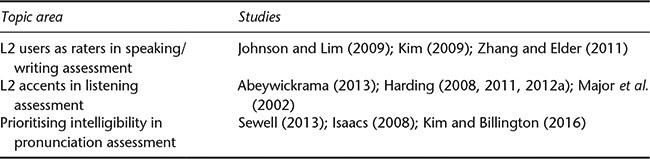

Table 45.1 Illustrative studies addressing ELF concerns in language assessment

p.570

Luke Harding and Tim McNamara

Introduction

The sociolinguistic reality of English as a lingua franca (ELF) communication represents one of the most significant challenges to language testing and assessment since the advent of the communicative revolution. ELF research not only destabilises the central place of the native speaker in determining acceptable and appropriate language use, but also forces us to reconsider the nature of language proficiency itself, and to recognise the important role played by accommodation and interactional communicative strategies. The implications for language assessment are radical: they involve at the very least a reconsideration of the criteria for judging successful performance, as well as a fundamental redefinition of the test construct to include more of what Hymes (1972) called “ability for use”, general cognitive and non-cognitive abilities not specific to language. The shifting of focus towards accommodation and interactional strategies also calls into question the policy of exempting participants in ELF communication who have native-language proficiency from being tested at all, given what studies have revealed of the role of native-speaker behaviour in communicative failure in ELF, particularly in high-stakes contexts such as aviation and medicine.

This chapter will discuss the challenge of English as a lingua franca for language assessment in four sections. The first section has introduced the issue of ELF and language assessment. The second section will describe the specific challenges ELF presents for language assessment, and connect these with broader debates around the nature of communicative competence. The third section will discuss how research in language testing and assessment has addressed the ELF challenge thus far, showing that tangible progress has been slow and more work needs to be done. The fourth section will discuss what an ELF construct for assessment purposes might look like, and how this construct could be operationalised through tasks. The conclusion will discuss future challenges for integrating ELF perspectives into language assessment.

Conceptualising the ELF challenge

As discussed in other chapters within this volume, ELF research has undergone a series of transformations over the past 20 years. Early studies typically represented attempts to describe regular features of ELF; that is, to identify common features of usage – phonological, syntactic, lexical, pragmatic – across English language communicative situations where interactants do not share the same first language (L1) (see Seidlhofer, 2005). Jenkins’ (2000) Lingua franca core is characteristic of this “first wave” of ELF research: a set of pronunciation features deemed crucial for speech intelligibility within ELF contexts. In this early stage, as described by Jenkins (2015), ELF shared commonalities with the World Englishes paradigm (e.g., Kachru, 1992) in its focus on description of a new variety with a view to establishing its legitimacy. Like the World Englishes movement, early ELF research also served to disrupt the assumption that native-speaker norms were central to successful communication: if interlocutors in ELF situations routinely communicate without recourse to native speaker norms, then for many language users, the native-speaker model would lose relevance.

p.571

This view eventually transformed into the current focus of much ELF research: revealing what makes communication in English successful in fluid and dynamic contexts (see Jenkins, Cogo and Dewey, 2011). Driven by insights gained from corpora (see Seidlhofer, 2011), ELF research has identified a range of elements crucial for communicative success including accommodation (adjusting to an interlocutor’s speech style) and the use of various strategies to pre-empt or negotiate misunderstandings, for example, requests for clarification, self-repair, repetition and paraphrasing (Jenkins et al., 2011). These strategic behaviours and linguistic repertoires are deployed in each new interaction in order to make meaning and achieve communicative outcomes. In this sense, ELF communication is purely a “context driven phenomenon” (Leung and Lewkowitz, 2006), or as expressed by Canagarajah (2007: p. 926), ELF is “intersubjectively constructed in each specific context of interaction . . . negotiated by each set of speakers for their purposes”.

Emerging from this research, the ELF challenge for language assessment comes in two parts: (Challenge 1) that native-speaker norms should no longer be considered the standard in language assessments, and (Challenge 2) that language assessment is wrongly focused on judging against a “stable variety” (Jenkins and Leung, 2013, p. 4), whether this be a native-speaker variety, or a legitimised L2 variety. Challenge 1 overlaps, to a certain extent, with a parallel critique posed by the World Englishes paradigm that large-scale, standardised tests based on “inner-circle” norms of English routinely penalise features of new or emerging varieties, and target features of native-speaker varieties that may be irrelevant for many L2 users (see Davies, Hamp-Lyons and Kemp, 2003; Lowenberg, 2000, 2002). This critique is not confined to discrete measures such as tests of grammar, vocabulary and pronunciation, but extends to considerations of rubric development and rater training in the assessment of writing and speaking, as well as the selection of input texts for reading and listening assessment.

Challenge 2 is ELF-specific. Jenkins and Leung explain the nature of the critique thus:

[ELF speakers] are not necessarily oriented towards a particular variety of English (native or otherwise) ... [t]herefore the language assessment issues raised by ELF transcend questions of proficiency conceptualized in terms of a stable variety; they are concerned with what counts as effective and successful communication outcomes through the use of English that can include emergent and innovative forms of language and pragmatic meaning.

(2013, p. 4)

The critique is, therefore, that there is a need to fundamentally reconfigure our understanding of language proficiency itself. This perspective is articulated at greater length in Canagarajah’s (2006) paper: “In a context where we have to constantly shuttle between different varieties and communities, proficiency becomes complex . . . One needs the capacity to negotiate diverse varieties to facilitate communication. The passive competence to understand new varieties” (p. 233). This type of capacity requires a shift away from viewing language proficiency as a static ability, and towards a view which foregrounds adaptability (Harding, 2014). For Canagarajah, the particular skills that would support this type of adaptability might include “proficiency in pragmatics . . . sociolinguistic skills . . . style shifting . . . interpersonal communication . . . conversation management and discourse strategies” (2006, p. 233).

p.572

There is a resemblance here to the area of communicative competence described by Hymes (1972) as “ability for use”. In his famous and influential model of communicative competence, Hymes argued that underlying the ability to communicate were not only knowledge of language forms and pragmatic conventions but both other kinds of knowledge (for example, areas of professional competence) and a range of non-cognitive factors such as motivation (1972, p. 283). He quotes Goffman (1967) to specify some of the likely dimensions of ability for use: “capacities in interaction such as courage, gameness, gallantry, composure, presence of mind, dignity, stage confidence” (cited in Hymes 1972, p. 283).

The possession of relevant features of “ability for use” cuts across the distinction between native and non-native speakers in two ways. First, not all native speakers are equally endowed with the capacities Hymes has in mind. Native speakers differ in their ability to tell jokes successfully, for example, a performance that involves a good memory for the joke, mimicry ability, a sense of timing, confidence in front of an audience, a sense of humour, and so on, not all of which native speakers possess to the same degree. Second, a non-native speaker may have the relevant non-linguistic knowledge or personal capacities to the same or to a greater degree than a native speaker. This implies that in terms of those capacities other than simple linguistic knowledge that underlie the ability to communicate, there is a level playing field between native and non-native speakers; native speakers have no natural advantage, and in fact may be deficient in ways that their non-native speaker interlocutors are not. If motivation, for example, as Hymes argues partly determines competence, then a native-speaker’s unwillingness to engage in those things that research has shown to facilitate successful communication in ELF settings may compromise their likelihood of success in those settings, compared to a motivated non-native speaker (see Lindemann, 2002). This is only one of many ways in which what interlocutors bring to ELF communication may not correspond at all to the abilities that are the focus of the native/non-native distinction. And exclusive focus on these latter abilities (let us call it language proficiency for short) misses the target of what should be our focus in determining who is competent in ELF communication and who is not.

Addressing ELF challenges in language testing research

Researchers from within the language testing community have responded in a serious, if sporadic, way to the two challenges raised by ELF. A number of conceptual papers over the past 10 years have discussed ELF (or more typically the broader issue of EIL (English as an international language), which is a conflation of ELF and WE concerns), and the opportunities these developments afford language testers in re-thinking constructs (Brown, 2014; Elder and Davies, 2006; Elder and Harding, 2008; McNamara, 2011, 2012, 2014; Sawaki, 2016; Taylor, 2006). These conceptual papers range from those that are strongly critical of current language testing practice (e.g. McNamara, 2011), through to those that provide a defence of the field in light of critiques (e.g., Brown, 2014; Elder and Harding, 2008; Taylor, 2006). Generally, the defence is in three parts: 1) that the field has engaged in useful research that provides greater insights into ELF concerns, 2) that language testing has already moved in the direction of prioritising communicative effectiveness, and 3) that other constraining factors around the assessment process – the need for clear measurement models, the avoidance of bias, acceptability among test-takers – make it difficult to initiate change. Given that these arguments were first advanced by Taylor in 2006, it is instructive to consider the current status of each defence.

p.573

Empirical research relevant to ELF in language assessment

On the first point, while there has been research interest into ELF issues from within language assessment, the range of topics has been limited, and arguably this research interest has mostly been concerned with Challenge 1 – the general notion that the native speaker should be displaced in language assessment. Research connected with this area has concentrated on three main areas: the use of non-native raters in judging speaking and writing assessment; the use of L2 accents in listening assessment; and the focus on intelligibility (rather than level of foreign accent) in pronunciation assessment. Example studies associated with each research area are shown in Table 45.1.

Results from these studies have provided useful empirical insights into the effects of shifting away from orthodox positions in the design and administration of language assessments. However, these studies have also raised numerous questions. For example, while the use of non-native speaker raters in speaking assessment has been shown to result in equivalent test scores (e.g., Zhang and Elder, 2011), the features of performance that raters attend to appear to differ according to their background. This is an acknowledgement of the inevitably greater variability involved in the assessment of ELF communication; while this is a real issue, it does not mean that the need to determine adequate means of assessing such communication can be wished away. Similarly, the use of L2 accents in listening assessment has shown occasional shared L1 effects, suggesting that L2 listeners are advantaged when listening to a speaker who shares their L1. This raises the problem of the potential for a small amount of bias. However, as Harding (2012a) has argued, the alternative to introducing bias is an impoverished test construct. In sum, while research has explored these issues, findings are rarely unequivocal, and usually point to the complexity of ELF scenarios. The decision around implementing change to assessment practices, therefore, often becomes one of testing policy rather than an issue that can be resolved empirically, although a commitment to the necessary program of research to identify and further understand the issues in assessing ELF communication should also be a priority for the field.

Table 45.1 Illustrative studies addressing ELF concerns in language assessment

p.574

The shift towards communicative effectiveness

On the second point, Taylor (2006), Elder and Harding (2008) and Brown (2014), for example, all point out that language testing – particularly those tests that have emerged from the communicative tradition – has already experienced a general shift from a focus on formal accuracy to one of communicative effectiveness. One example of this kind of shift has been seen in some scales of pronunciation ability, such as the “delivery” part of the TOEFL iBT speaking scale, which makes no reference to native speaker norms, and instead refers only to intelligibility. Similarly, writing or speaking scales that include a criterion for grammar may focus more on appropriateness or effective conveyance of meaning than formal accuracy.

Yet, as McNamara (2012) points out, the native speaker still “lurks” within many scales and proficiency frameworks either explicitly, or implicitly (e.g., in references to “naturalness”). In the speaking sub-scales of the Common European Framework of Reference (Council of Europe, 2001), for example, the assumption throughout is that the L2 user whose capacities the framework offers to define is engaged in communication with a native speaker, rather than another L2 user. Egregious instances within the framework descriptors make this painfully clear, as in the following characterisation of ability to hold a conversation at B2 level: “Can sustain relationships with native speakers without unintentionally amusing or irritating them or requiring them to behave other than they would with a native speaker” (Council of Europe, 2001, p. 76). This privileging of the native speaker is also reflected in policies that assume that separate assessments are required of the communicative skills of native and non-native speakers, with native speakers automatically granted exemption from assessment (for example, in current policies governing entry into the international aviation workplace: Kim and Elder 2009, 2015). In fact, however, research has for many years, and again recently, demonstrated the variability of native-speaker performance on cognitively demanding language assessment tasks (Hamilton et al., 1993; Hulstijn, 2007, 2011), so that the assumption of the superiority of native-speaker performance is unwarranted, especially at levels of proficiency beyond the basic.

Elsewhere, there has been discussion of paired speaking as a potential type of test format currently in use (e.g., in the Cambridge English: Advanced) where ELF competences may be targeted (see Taylor and Wigglesworth, 2009). By nature, paired- (and group-) speaking tasks create the conditions for ELF communication: they include NNS–NNS communication, and as a result test-takers may need to negotiate meaning, deal with unfamiliar variation, accommodate their interlocutor and repair communication breakdown. However, even in a paired-speaking test, ELF strategies may not be activated if no “complication” is introduced in the interaction (e.g., if the interaction progresses smoothly there may not be any reason to negotiate meaning; if interactants have high levels of proficiency there may be no opportunities to negotiate form). In addition, rating scales for these tasks continue to focus more on “language proficiency” as described above. For example, the publicly available rating scale for the Cambridge English: Advanced (Cambridge English Language Assessment, 2015, pp. 86–87) makes reference to “negotiation”, but this is in relation to the need to bring the conversation towards an outcome (conversation management). There are no references to self-repair, re-formulation, repetition or paraphrase, and indeed the descriptors for the “discourse management” criterion suggest that a candidate may be penalised for repetition or hesitation. Paired-speaking tasks are useful additions to the repertoire of tasks used in language assessments, but they do not necessarily provide evidence of a candidate’s ability to operate in a challenging ELF communication environment.

p.575

Managing constraints

A number of barriers to adopting an ELF approach in language testing have been identified in discussion of assessment of ELF communication, but in our view none of them are insurmountable, or are in fact nullified if there is a clear purpose-driven need for operationalising the ELF construct. Underlying much of the discussion is an ideological conservatism, really an institutionalised conservatism, which often prevents change from taking place.

The first barrier is what might be called a concern for stability. Test-takers generally prepare for examinations, and preparation is usually more straightforward when there is a particular standard or body of knowledge which needs to be mastered rather than a novel situation that needs to be coped with. To some extent of course all language assessment, especially when formalised in language examinations, is a game with rules; the necessary artificiality of assessment procedures contributes to this perception of the test on the part of test-takers. While one can have some sympathy with this preference for the known and for what can be prepared for, the nature of English as a lingua franca communication is inevitably unpredictable, and we cannot allow a focus on test preparation to distract us from the construct we are intending to assess.

Second, there are concerns for fairness, the avoidance of bias and threats to reliability (see Brown, 2014; Elder and Harding, 2008). These are of course important professional considerations for all test developers. As stated earlier, a comprehensive program of research is required to identify the greater of these threats and ways to overcome them; language testing research has a history of identifying and solving problems in communicative language assessment on which it can draw. The articulation of a clear ELF construct derived from a domain analysis would be a useful starting point in constructing an interpretation/use argument (Kane, 2013).

Third, there are concerns for acceptability: the fear that test-takers may not “accept” changes to norms. This also has an impact on the commercial viability of large-scale tests. Of course any changes require “selling” and proper communication. In teaching about, and researching, ELF communication and assessment, we have encountered enthusiastic responses, particularly from non-native English-speaking students, when they understand the nature of the change and its motivation in terms of fairer and more relevant assessments, and the level playing field between native and non-native speakers in ELF communication, which they welcome. The ideological conservatism resisting this change is likely to come more from native speakers and the language teaching and language testing industries dominated by organisations in English-speaking countries than from the learners themselves. Native speakers will not relinquish their privilege easily, but commercial forces can be harnessed to bring in the change, if creative means of teaching and assessing ELF communication continue to be developed.

Towards a model of ELF assessment

One position agreed upon by all commentators is that assessment decisions should be governed by test purpose, and that design decisions should proceed from clear view of the purpose of the test (e.g., Brown, 2014; Sawaki, 2016). This position is perhaps the clearest form of support for attempting to assess ELF competences across a range of domains. Arguably, an ELF approach would be extremely valuable in many language for specific purposes (LSP) assessment contexts: aviation (Kim and Elder, 2009, 2015); diplomacy and international relations (Kirkpatrick, 2010); business communication (Rogerson-Revell, 2007), call-centre communication (Lockwood, 2010); English for academic purposes (Smit, 2010); and health communication (Roberts, Atkins and Hawthorne, 2014).

p.576

To take the example of aviation English, Kim and Elder (2009) demonstrated that language proficiency assessment policies governing access to the international aviation workplace have got it wrong about who is safe to be admitted, and who is not, a failure that has had led to a covert boycott of the policy by a number of national aviation regulating bodies. Kim’s PhD research (Kim 2009) investigated what were the contributing factors to communication failure involving English as a lingua franca communication in “near miss” situations at Seoul’s Incheon airport, using introspective accounts from experienced Korean pilots and air traffic controllers as they listened to recordings of the episodes of communication failure. Many factors were found to contribute. Above a minimum threshold of proficiency, factors such as situation awareness, experience and cooperativeness in this ELF situation were found to contribute most; native-speaking pilots were found to contribute to the failure as much as or more than non-native speaking pilots or air traffic controllers. Yet native speakers are often considered by definition exempt from the communication assessment regime required by the International Civil Aviation Organisation. A proper understanding of the nature of English as a lingua franca communication, which is in fact properly reflected in some of the conventions for communication in the international workplace, but that are often not observed by more proficient speakers, particularly native speakers, would significantly alter the appropriate assessment regime.

Developing a construct

It is clear that compelling reasons exist for the assessment of ELF competences, particularly in English for specific purposes contexts. However, to date there is little guidance on what an ELF construct would involve, and how it might be operationalised. Elder and Davies (2006) explored the feasibility of an “ELF test”, proposing two different models. The first was a test where special consideration was given to ELF users by way of, for example, avoiding NS-centric vocabulary, recruiting highly proficient ELF users as interlocutors in speaking exams, training raters to ignore non-standard features that did not impact on understanding, and involving ELF users in the standard-setting process. This model of ELF assessment connects with Challenge 1, described above. The second proposal was more in line with Challenge 2. Elder and Davies suggested a range of tasks where strategic competence, adaptability and task fulfilment would be prioritised, such as listening tests featuring multiple accents and role-play speaking assessments where interlocutors were from different linguacultural backgrounds, and different proficiency levels.

Beyond Elder and Davies’ (2006) suggestions, there has been little written on the practical steps that would be required to move beyond discussion of ELF assessment, and to develop a workable construct definition that could then be operationalised. Recognising this gap, and drawing on the previous work of Elder and Davies, as well as Canagarajah (2006), Harding (2012b) proposed a set of competences that might provide a starting point for developing an ELF construct for assessment purposes:

p.577

• The ability to tolerate and comprehend different varieties of English: different accents, different syntactic forms and different discourse styles.

• The ability to negotiate meaning when meaning is ambiguous.

• The ability to use those phonological features that are crucial for intelligibility across speakers of different L1 backgrounds.

• An awareness of appropriate pragmatics (e.g., awareness of politeness in cross-cultural situations).

• The ability to accommodate your interlocutor, to make yourself understandable to whomever you are speaking with.

• The ability to notice and repair breakdowns in communication.

Although some of these competences could be targeted through more traditional proficiency tasks (e.g., the first competence might be assessed by introducing a greater range of spoken varieties in listening assessment), the ELF construct would arguably be most efficiently assessed through a purpose-built assessment task designed to capture the various competences within the same communicative task. An illustrative example of a study exploring the feasibility of a purpose-built task of this kind is described below.

Operationalising an ELF construct

In order to test how the list of competences above might be operationalised in practice, Harding (2015) conducted a pilot study of a purpose-built ELF assessment task. Using the earlier description of the ELF construct as a starting point, Harding mapped out the specific features of a task designed to elicit those features (Table 45.2).

A suitable task was identified in the map tasks collection of the Human Communication Research Corpus [HCRC] (see Anderson et al., 1991). The task is an information-gap activity where one speaker takes the role of “information provider” (IP) and must explain a route on the map to an interlocutor, the “information receiver” (IR). Differences in landmarks provided on each map provides a complicating factor that requires the negotiation of meaning. The task can also be designed to provide challenges on a linguistic level (such as consonant clusters or unfamiliar vocabulary), which are anticipated to provoke negotiation of form. In this sense, the map task met all of the requirements listed in Table 45.2.

p.578

Two participants, who were unknown to each other, took part in the pilot study: May (a Thai L1 adult student) and Ricardo (a Spanish L1 adult student). Evidence of repetition and clarification strategies were observed at different points in the interaction, such as the example shown in Excerpt 1 below, where Ricardo – who was following May’s directions, but did not have “pelicans” marked on his map – repeats the word “pelicans” as a clarification check, and reformulates “your right hand” as “on my right” for the same purpose:

Excerpt 1

| May: | and from Saxon barn (1.6) ah: (.6) go down the hill again (.) and you see pelicans |

| Ricardo: | (1.6) pelicans (.) [where where are the pelicans= |

| May: | [yes =pelicans is on your right |

| (.) your right hand= | |

| Ricardo: | =on my right um: |

(Harding, 2015, p. 25)

What is notable about this exchange is that it does not appear typically “fluent” – both interlocutors pause frequently and at length. However, the focus of the interaction is on successful communication, which the speakers appear to achieve in this particular exchange. Elsewhere, there was evidence of further requests for clarification and repetition, as well as accommodation in the form of self-repair (reformulating mispronunciation).

While discourse-level data from the pilot task suggested that ELF-like competences were being elicited at points throughout the task, the major challenge was how to capture these for scoring/rating purposes. A simple holistic rubric was trialled with 10 judges based on the competence areas described in Table 45.3, which in turn was based on aspects of ELF communication that have emerged from the literature (Jenkins et al., 2011). While there was broad agreement about which of the interlocutors demonstrated more of these features, it was far from clear what judges were attending to in the performances, or indeed whether the scale was being interpreted in any meaningful way.

The pilot study led to some useful observations about the potential of a task such as this to tap into ELF competences. For one, the task selected had some features that could be usefully translated into more specific testing contexts (e.g., its goal-oriented, information-gap nature; the inclusion of specific complications); however the task lacked authenticity and would therefore be likely to have negative washback. Of equal importance, the scoring of an ELF task raises enormous practical challenges. What is observable through an analysis of discourse may be very difficult for raters to detect in practice. Further research is therefore required to explore the potential for more authentic tasks which include the features described in Table 45.2, and also to develop data-driven rating scales which capture the ELF-related strategic behaviour observed.

p.579

Conclusion

Implications of ELF for constructing language assessments

The above discussion points the way to a need for purpose-built ELF assessment tasks. Existing assessments may not be easily re-tooled for ELF assessment purposes, but in situations where ELF assessment is desirable, tasks might include features that would allow the elicitation of ELF performance (essentially, tapping into “ability for use”). Alternatively, it seems more likely that ELF is, at least in the short term, not going to replace more static proficiency constructs, but rather would function as an add-on in contexts of language assessment where ELF competences are expected to come into play (which may be all situations). An example of this kind of gradual change can be found in the project for reforming the criteria for assessing spoken competence in a major test of English for health communication, the Occupational English Test (OET) (Elder, 2016). Investigation of what counts for clinical supervisors in judging clinical trainee communication with patients led to recommendations for the revision of the criteria used to assess performance on the clinically based roleplay tasks in the OET speaking test. Two criteria additional to the traditional proficiency criteria were recommended, focusing on the clinician’s management of the interaction and their engagement with the patient (Pill, 2016). The option was given of reporting performance against these two criteria separately from performance against the proficiency criteria. It may be symptomatic of the difficulty of reform that there is no sign at the time of writing that the owners of the test, which includes Cambridge English Language Assessment, will heed these recommendations.

Implications of ELF for determining language assessment policy

As we have seen in the discussion of the aviation setting above, ELF assessment opens up the question of who is to be tested; removing the privileged status of the non-native speaker, who may have no natural advantage over a non-native speaker in achieving successful ELF communication. We have argued, however, while ELF assessment flows naturally from a deep understanding of the communicative demands of particular language domains, so that there should be no implicit barrier in determining whose language is to be assessed in these terms, this would represent a radical shift for language assessment generally. We can see the difficulties involved if we consider again the case of aviation. Despite variations in the implementation of the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) language proficiency requirements for aviation English, in many cases native speakers are assessed in quite different ways from non-native speakers in order to determine (or indeed, confirm) only that their proficiency is at “Expert Level 6” (see Estival et al., 2016). We would argue that the widescale adoption of these practices – which often effectively exempt native speakers from needing to demonstrate language skills crucial to ELF communication – provides evidence of an institutionalised conservatism, discussed above, around the place of the native speaker in language assessment policy. Further, the profession of language testing, through its international organisation the International Language Testing Association (ILTA), has focused its efforts to support the existing ICAO policy by offering to validate the quality of the assessment instruments used by national authorities. However, this process may have at the same time granted legitimacy to misguided practices in the assessment of native speakers under the ICAO guidelines. We can look to a long struggle ahead in this and in other domains where ELF assessment presents a fundamental challenge.

p.580

Related chapter in this volume

46 Shohamy, ELF and critical language testing

Further reading

Brown, J.D. (2014). The future of World Englishes in language testing. Language Assessment Quarterly, 11(1), pp. 5–26.

Canagarajah, S. (2006). Changing communicative needs, revised assessment objectives: Testing English as an international language. Language Assessment Quarterly, 3(3), pp. 229–242.

Elder, C. and Davies, A. (2006). Assessing English as a lingua franca. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 26, pp. 282–304.

Jenkins, J. and Leung, C. (2013). English as a lingua franca. In A. Kunnan, ed., The companion to language assessment. John Wiley & Sons, pp. 1607–1616.

McNamara, T. (2011). Managing learning: Authority and language assessment. Language Teaching, 44(4), pp. 500–515.

References

Abeywickrama, P. (2013). Why not non-native varieties of English as listening comprehension test input? RELC Journal, 44(1), pp. 59–74.

Anderson A.H., Bader M., Bard E., Boyle, E., Doherty, G., Garrod, S., Isard, S., Kowtko, J., McAllister, J. Miller, J., Sotillo, C., Thompson, H.S. and Weinert, R. (1991). The HCRC map task corpus. Language and Speech, 34(4), pp. 351–366.

Brown, J.D. (2014). The future of World Englishes in language testing. Language Assessment Quarterly, 11(1), pp. 5–26.

Cambridge English Language Assessment (2015). Cambridge English advanced: Handbook for teachers for exams from 2015. Cambridge: Cambridge English Language Assessment.

Canagarajah, S. (2006). Changing communicative needs, revised assessment objectives: Testing English as an international language. Language Assessment Quarterly: An International Journal, 3(3), pp. 229–242.

Canagarajah, S. (2007). Lingua franca English, multilingual communities, and language acquisition. The Modern Language Journal, 91(s1), pp. 923–939.

Council of Europe (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Davies, A. Hamp-Lyons, L. and Kemp, C. (2003). Whose norms? International proficiency tests in English. World Englishes, 22(4), pp. 571–584.

Elder, C. ed. (2016). Exploring the limits of authenticity in LSP testing. Special Issue. Language Testing, 33(2).

Elder, C. and Davies, A. (2006). Assessing English as a lingua franca. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 26, pp. 282–304.

Elder, C., and Harding, L. (2008). Language testing and English as an international language. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 31(3), pp. 1–34.

Estival, D., Farris, C., and Molesworth, B. (2016). Aviation English: A lingua franca for pilots and air traffic controllers. London and New York: Routledge.

Hamilton, J., Lopes, M., McNamara, T.F. and Sheridan, E. (1993). Native-speaker performance on tests of English for Academic Purposes. Language Testing, 10, pp. 337–353.

p.581

Harding, L. (2008). Accent and academic listening assessment: A study of test-taker perceptions. Melbourne Papers in Language Testing, 13(1), pp. 1–33.

Harding, L. (2011). Accent and listening assessment: A validation study of the use of speakers with L2 accents on an academic English listening test. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Harding, L. (2012a). Accent, listening assessment and the potential for a shared-L1 advantage: A DIF perspective. Language Testing, 29(2), pp. 163–180.

Harding, L. (2012b). Language testing, World Englishes and English as a lingua franca: The case for evidence-based change. Invited keynote address, CIP symposium 2012, University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

Harding, L. (2014). Communicative language testing: Current issues and future research. Language Assessment Quarterly, 11(2), pp. 186–197.

Harding, L. (2015). Adaptability and ELF communication: The next steps for communicative language testing? In J. Mader and Z. Urkun, eds, Language testing: Current trends and future needs. IATEFL TEASIG.

Hulstijn, J.H. (2007). The shaky ground beneath the CEFR: Quantitative and qualitative dimensions of language proficiency. The Modern Language Journal, 91(4), pp. 663–667.

Hulstijn, J.H. (2011). Language proficiency in native and nonnative speakers: An agenda for research and suggestions for second-language assessment. Language Assessment Quarterly, 8(3), pp. 229–249.

Hymes, D. (1972). On communicative competence. In J.B. Pride and J. Holmes, eds, Sociolinguistics. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, pp. 269–293.

Isaacs, T. (2008). Towards defining a valid assessment criterion of pronunciation proficiency in non-native English-speaking graduate students. Canadian Modern Language Review, 64(4), pp. 555–580.

Jenkins, J. (2000). The phonology of English as an international language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jenkins, J. (2015). Repositioning English and multilingualism in English as a lingua franca. Englishes in Practice, 2(3), pp. 49–85.

Jenkins, J. Cogo, A. and Dewey, M. (2011). Review of developments in research into English as a lingua franca. Language Teaching, 44(3), pp. 281–315.

Jenkins, J. and Leung, C. (2013). English as a lingua franca. In A. Kunnan, ed., The companion to language assessment. John Wiley & Sons, pp. 1607–1616.

Johnson, J.S. and Lim, G.S. (2009). The influence of rater language background on writing performance assessment. Language Testing, 26(4), pp. 485–505.

Kachru, B.B. (1992). The other tongue: English across cultures. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Kane, M.T. (2013). Validating the interpretations and uses of test scores. Journal of Educational Measurement, 50(1), pp. 1–73.

Kim, Y.H., (2009). An investigation into native and non-native teachers’ judgments of oral English performance: A mixed methods approach. Language Testing, 26(2), pp. 187–217.

Kim, H. and Billington, R. (2016). Pronunciation and comprehension in English as a lingua franca communication: Effect of L1 influence in international aviation communication. Applied Linguistics. doi:10.1093/applin/amv075.

Kim, H. and Elder, C. (2009). Understanding aviation English as a lingua franca: Perceptions of Korean aviation personnel. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 32(3), pp. 23.1–23.17

Kim, H. and Elder, C. (2015). Interrogating the construct of aviation English: Feedback from test takers in Korea. Language Testing, 32(2), pp. 129–149.

Kirkpatrick, A. (2010). English as a lingua franca in ASEAN: A multilingual model. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Leung, C. and Lewkowicz, J. (2006). Expanding horizons and unresolved conundrums: Language testing and assessment. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), pp. 211–234.

Lindemann, S. (2002). Listening with an attitude: A model of native-speaker comprehension of non-native speakers in the United States. Language in Society, 31(3), pp. 419–441.

Lockwood, J. (2010). Consulting assessment for the business processing outsourcing (BPO) industry in the Philippines. In G. Forey and J. Lockwood, eds, Globalization, communication and the workplace (pp. 221–241). New York: Continuum International.

p.582

Lowenberg, P. (2000). Non-native varieties and the sociopolitics of English proficiency assessment. In J. Hall and W. Eggington, eds, The sociopolitics of English language teaching. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Lowenberg, P. (2002). Assessing English proficiency in the expanding circle. World Englishes, 21(3), pp. 431–435.

McNamara, T. (2011). Managing learning: Authority and language assessment. Language Teaching, 44(4), pp. 500–515.

McNamara, T. (2012). English as a lingua franca: The challenge for language testing. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 1(1), pp. 199–202.

McNamara, T. (2014). 30 years on: Evolution or revolution? Language Assessment Quarterly, 11(2), pp. 226–232.

Major, R.C., Fitzmaurice, S.F., Bunta, F. and Balasubramanian, C. (2002). The effects of nonnative accents on listening comprehension: Implications for ESL assessment. TESOL Quarterly, 36(3), pp. 173–190.

Pill, J. (2016). Drawing on indigenous criteria for more authentic assessment in a specific-purpose language test: Health professionals interacting with patients. Language Testing, 33(2), pp. 175–194.

Roberts, C., Atkins, S. and Hawthorne, K. (2014). Linguistic and cultural factors in the membership of the Royal College of General Practitioners examination. London: Centre for Language, Discourse and Communication, King’s College London with the University of Nottingham.

Rogerson-Revell, P. (2007). Using English for international business: A European case study. English for specific purposes, 26(1), pp. 103–120.

Sawaki, Y. (2016). Large-scale assessments of English for academic purposes from the perspective of English as a lingua franca. In K. Murata, ed., Exploring ELF in Japanese academic and business contexts: Conceptualisation, research and pedagogic implications. New York: Routledge, pp. 224–239.

Seidlhofer, B. (2005). English as a lingua franca. ELT Journal, 59(4), pp. 339–341.

Seidlhofer, B. (2011). Understanding English as a lingua franca. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sewell, A. (2013). Language testing and international intelligibility: A Hong Kong case study. Language Assessment Quarterly, 10(4), pp. 423–443.

Smit, U. (2010). English as a lingua franca in higher education. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

Taylor, L. (2006). The changing landscape of English: Implications for language assessment. ELT Journal, 60, pp. 51–60.

Taylor, L. and Wigglesworth, G. (2009). Are two heads better than one? Pair work in L2 assessment contexts. Language Testing, 26(3), pp. 325–339.

Zhang, Y. and Elder, C. (2011). Judgments of oral proficiency by non-native and native English speaking teacher raters: Competing or complementary constructs? Language Testing, 28(1), pp. 31–50.