Little Burgundy was a refuge. To escape our prior workplace, Fred and I would go for drives around Montreal, stopping at hardware stores, food markets, Chinatown, old corner restaurants. Sometimes we would browse junk shops or raid the downtown Salvation Army. Maybe we were already starting to build a restaurant in our minds, or maybe we just needed to get away from the supper-club scene on Boulevard Saint Laurent, where we worked. Either way, we were always on the lookout for old plates, oyster forks, live king crabs, shitty chairs, medicine cabinets, or the ultimate baloney sandwich. All roads led to Little Burgundy.

Little Burgundy is an area in southwest Montreal bordering the Lachine Canal. In the mid-1700s, French colonists named it La Petite-Bourgogne because of its resemblance to its namesake in France. It sits on a plateau, south of Mount Royal and just north of the Saint Lawrence River. Home to the Canadian National Railway yards and the Canadian Steel plant, Little Burgundy was, and remains, a working-class neighborhood. For the past ten years, it has been featured in every local magazine’s “next up-and-coming neighborhood” article, but for reasons both obvious and obscure, it has been slow to reach its supposed potential.

Notre Dame is Little Burgundy’s main north-to-south thoroughfare, a street full of inimitable characters, historical edifices, and appealing old boutiques, among them the amazing Grand Central antiques, the eclectic and now sadly defunct Arcadia, the Irish lady junk shop, and the All Things Vintage store. Nearby is antique purveyor Madame Cash, who earned her nickname in the 1960s from cashing government checks for residents in the surrounding row houses. Across the street stands the majestic Corona Theatre. Ella and Oliver Jones played there; so did Oscar Peterson, who was born in Little Burgundy. Around the corner is the ever-abiding Atwater Market. This neighborhood has everything going for it.

Among all this stood Café Miguel, a diamond in the (very) rough located at 2491 Rue Notre Dame West owned by a wildly passive-aggressive troll of a man. He made six killer sandwiches and espresso as strong as it was good. And while his ambition to open a small restaurant was good, he soon ran into trouble—trolls, alas, don’t make good restaurant owners. His trouble was our opportunity, and Allison, Fred, and I got to thinking. We knew we could cook, we knew what the restaurant should look like, and we knew intuitively that we could get people to come to Little Burgundy. But it would take work.

For one thing, the café was a bit of a dump, like a dirty pig that wears a dress, too many accessories, and perfume. It had a solid, yet filthy shell and was furnished with IKEA tables, school chairs, and a blackboard with sandwich listings full of spelling mistakes. There was a six-burner stove, a deep fryer, a ventilation hood, an espresso machine, and a working chimney. We would essentially be acquiring the bare bones of a restaurant, which might make it workable, since we had very little money to start.

The backyard was full of graffiti, cigarette butts, beer bottles, tiny plastic bags, and what Fred believed was industrial waste. The clientele consisted of local furniture refinishers and antique dealers—basically guys with yellow fingers who stunk of lacquer thinner. Allison, Fred, and I held meetings in my truck in the backyard, during which we brainstormed on what our restaurant might look like, what food we would serve, and who we would harass—or terrorize—for favors to get it off the ground. We had anxiety about putting it all together, and for good reason: we don’t have the organizational skills to do anything. Ask anyone and they’ll tell you that we essentially have the attention spans of ferrets on speed. At least Fred and I do. Allison is the voice of reason.

So we met with three friends who also happen to be financial guys, Ronnie Steinberg, Jeff Baikowitz, and David Lisbona, to see if our idea could become a financial reality. We don’t remember much of the meeting except that it was boring, it was held in a boardroom, and after five minutes I was wearing a baseball helmet I picked off a nearby shelf and Fred was chasing me around with no shirt on. The obvious conclusion is that Ronnie, Jeff, and David convinced us it could work (if we did it on the cheap), and they agreed to partner in for 10 percent. Jeff tells us now that when we left the room, he told Ronnie and David to give whatever amount they would feel comfortable never seeing again.

We are still partners with these three, and if it weren’t for them, none of this would be possible. If you walk into David Lisbona’s office today, you’ll see seventy-five laminated newspaper clippings about Joe Beef alongside one picture of his kids. Their faith and pride in us are astounding.

It took two months to build. We scrounged quickly to make it work. The restaurant came together with love, about twenty packs of wainscoting, and unlimited generosity and interest from friends. Mathieu Gaudet, a Montreal sculptor, friend, and Saint Henri local, built, among other things, our tables. On first glance, they look like they are ebony and mahogany, but they are actually MDF (medium-density fiberboard) combined with that really bad Masonite pressboard and many shiny coats of oil finish. He also built the bar from an old farmhouse floor that probably had fifteen coats of lead paint on it. (Don’t worry, it’s sealed; you can’t go crazy from eating at the Joe Beef bar.)

The beautiful old tavern chairs we found by chance. We spotted them when we were driving around one day and pulled over and asked the guy what he wanted for them. He said twenty bucks—not per chair, but for the lot.

Our friend Peter Hoffer did a beautiful installation of paintings: about twenty small abstracts and landscapes on one wall. We have always liked Peter’s aesthetic, whether it is of Quebec trees or girls without shirts. His art fits our rustic environment and feels like it has always been there.

The eccentric and kooky Joe Battat, another one of our friends and favorite customers, showed up one day in the dining room with a giant bison head. It looks real and is about half the size of a Honda Civic. We zapped it onto the wall of the bathroom, and it has been scaring young kids ever since.

A couple of years back, one of our customers, Howie Levine, gave Fred a fart machine with a remote control. Fred immediately hid it in an ear of the bison, so whenever someone walked into the bathroom and closed the door, Fred would go crazy on the remote and wait for the customer to emerge in a daze of confused humiliation.

The bathroom also boasts old photos taken at Bob Dylan and Neil Young concerts by Joe Battat and the door is covered with old Canadian license plates, fishing permits, and Quebec signage. Serendipitously, all the crazy elements seem to come together.

People still show up with old nostalgia-laden items that somehow fit the spirit of Joe Beef—things they’ve found at yard sales, in their grandma’s attic, at the back of the garage. We have a barracuda caught by a Quebec politico, Viking candelabras, bear heads, a grand notice of the beatification of the now good brother Saint Andre, whale bones, trophies (Best Eater: Kevin), pictures of Uncle Jack fishing for salmon in British Columbia, and glasses shaped like naked women.

In other words, ambience is a big part of Joe Beef. The lighting, the music, and what’s on the walls matter a great deal to us. Wine and food are not the only story. A true restaurateur has to be a jack of many trades. You see it all the time in restaurants: the food is good and the wine list is awesome, but the chairs suck, the art on the wall is revolting, and a Café Del Mar CD is playing continuously on the sound system. You can be a good cook or even a great chef, but it doesn’t make you a restaurateur. You have to have other interests, and you have to actually read.

Thankfully, Fred, Allison, and I geek out over the same classic stuff: a perfect Adirondack chair, a red vinyl banquette with brass nails, a pretty oyster-bar counter, old enameled cast-iron sinks, industrial lamps, a banged-up Rancilio coffee machine. We like wood, old paint, and a simple touch of cottage. This is why we love Maine, the Gaspé, and Kamouraska. I had so many bad experiences with Montreal’s “hottest” designers, who simply couldn’t design a proper service station, that I ended up buying an old medicine cabinet for Joe Beef. Its shelves, drawers, and glass bottles that once held swabs now hold knives. It works and it looks like it is where it should be. As Joe Beef came together, that’s how it felt in general: like it had always been there.

The restaurant group we worked with prior to Joe Beef never understood our cooking, but the customers did. We are thankful for the experience; it just wasn’t for us. We wanted our next project to be different from anything we had done before. We wanted to open a small, simple bistro, not unlike what Sam Hayward was doing with beautiful country food at Fore Street in Portland, Maine.

We imagined we would walk to the market and buy our produce every day. I was going to cook the meats, Fred was going to do the appetizers and vegetables, and then we were going to do the dishes … together. Allison would run the dining room, and John Bil would tend bar and shuck the occasional oyster. We would be open for lunch. Seventy bucks would be our top-end wine. Fred would put one lobster item on the menu, but more for him than for anyone else. We figured we might move one or two lobster spaghettis per day but not much more. We just wanted to sell a few oysters, a bit of fish, and a bit of steak.

On opening day, the restaurant was packed. It went well. The only crazy thing was that Fred and I shelled fava beans in the backyard for three hours, and we believed that it was going to be that way every day. On the second day of business, we realized we needed to get a proper dishwasher. We also realized at 4:00 P.M. that we had been there since 9:00 A.M. and we wanted to go home. One lunchtime highlight was watching a country gentleman named Mr. Barber eat Dungeness and drink Meursault while wearing classic hunting apparel. Hence, the Grand Opening and prompt Grand Closing of lunch service at Joe Beef.

When we first opened, we thought we would be catering primarily to the antique dealers and other locals who lived on the Lachine Canal. But people actually followed us from our previous workplace, and we were getting customers who wanted to pay for two-pound lobsters, small-farm beef, and small-grower Champagnes and premier cru Burgundies. Fred was thrilled to come up with these dishes, and I was more than willing to work with private wine agents who wouldn’t have dealt with us on Saint Laurent. We had the opportunity to work with modest-sized purveyors because we were working in a different context. All of a sudden, these smaller sources were not only willing to sell to Joe Beef, they were also coming to the restaurant to eat and visit!

We have never experimented with the concept of the food at Joe Beef. It has evolved in some ways, of course, but the food has always been the food we wanted to do since day one. We serve true Bocusian-Lyonnaise cuisine du marché (French market cuisine), which enables us to roll with the market in a way that wouldn’t be possible with a printed menu. Although some complained that our food “lacks presentation” or is “too simplistic,” we started getting good reviews and earning acclaim soon after opening. Chefs from every corner of the United States started showing up at our door.

One night, Fred noticed a ragged-looking Korean American guy ordering everything on the menu. Lo and behold, it was David Chang, owner of New York’s Momofuku. This was right before David was ordered to rest by his doctor. He had boarded a plane for Montreal, landed at Trudeau International Airport, and was at the Joe Beef bar a couple of nights later. The week was, of course, a complete haze of food, wine, and long nights, and David has been a good friend and Joe Beef supporter ever since. The props he gave us were a game changer for us, and now we seem to be part of the North American Food Itinerary. We’re baffled and utterly appreciative. But more important, we are truly happy coming to work every day.

Six months after Joe Beef opened, we were booking one month in advance. You may think it is a dream to be that busy, but when you’re small, reservations can be a nightmare to manage. Each day you pick up the phone and say no to all the people who were there with you from the beginning, including your mom.

So two years later, when our landlord and friend, Danny Lavy, told us that the restaurant space he owned two doors down was coming up for rent, we jumped at the chance to expand. “More tables and more room for all of our shit in the basement,” we thought.

The building at 2501 Rue Notre Dame West is a beautiful Victorian. It has a double entrance and, from the outside, looks like two side-by-side soda-pop shops. When we took over the lease, the inside was a complete disaster. Electrical wiring was covered by floral wallpaper, and chicken wire was posing as some sort of modern installation on the ceiling. We took four truckloads of garbage out of there in the first week, and soon after painted the walls and floors the original Canadian National Railway green. We worked steadily for five or six weeks, and with the exception of Pelo (one of the earliest cooks at Joe Beef) falling through the floor into the basement, there was little drama.

From the beginning, Liverpool House had a more feminine aesthetic than the decidedly masculine Joe Beef. What was not feminine, however, was the smell. It took us a few weeks to find out we had a dead skunk under the storage room. When a skunk dies, it, like most animals, decomposes quickly. The scent sack, on the other hand, doesn’t. Each time a customer walked in the front door, we prayed he or she wouldn’t notice. But, of course, everyone noticed. It stunk! So we called Monsieur Caron, a murder grow-op cleanup guy who did skunks on the side. He and his wife (who also calls him Monsieur Caron) showed up, and after a couple of minutes said, “The good news is you don’t have a live skunk. The bad news is you have a dead one.” He tried everything from a perfume that smelled like patchouli to an oxidizing compound. Nothing worked. Finally, he brought in the big gun, an ozone generator that we had to turn on each night after service (and walk away quickly because it was toxic). It took about six months for the smell to disappear completely.

Other than the persistent scent sack, we had no real issues opening Liverpool … well, except maybe for the Italian thing. We had the idea to open an Italian version of Joe Beef, but we all knew that the idea was mostly tongue-in-cheek, since neither Fred nor I has a drop of Italian blood. We didn’t want to mess with Joe Beef. We loved it the way it was, and our plan was that Liverpool would complement it and vice versa. That said, we wanted to serve Italian food that you might get in London, à la River Café, not what you would get in Rome. If you could order mushrooms with a poached egg and mimolette cheese at Joe Beef, then you could get mushrooms with a poached egg and shaved Parmesan at Liverpool, and all of a sudden it seemed Italian. We wanted to order basket-clad Chianti; hang heavy, purple velvet curtains; and get someone really rich to lend us a Caravaggio (“Don’t worry about it, we’re in the worst part of town, it will be fine.”)

We stuck with the Italian idea for about six months and then phased it out. Few people asked any questions. Liverpool House now is like Joe Beef’s bistro, or Joe Beef lite. It’s for the everyday, and we gladly serve many locals. A TV is tucked away in one corner for watching nos glorieux Canadiens de Montréal play, and luckily for us, it’s a favorite after-game destination for the Habs players. It’s got a bustling bar, and I would say four of the eight stools are almost always taken by restaurant people. Liverpool is the kind of place you can drop in after work for a dozen Carr’s Family Malpeque oysters, a couple glasses of Muscadet, and a piece of fish, and have a conversation with the bartender or watch the game and go home.

Named after Montreal’s venerable tavern owner Charles McKiernan (see the excerpt by Peter DeLottinville), our luncheonette sits on the other side of Joe Beef, right next door. The two share one backyard, which serves as the McKiernan lunch terrace and the Joe Beef dinner terrace in the summer. The space used to be a great little vegetarian spot called Bonnys, which we happily took over when Bonny moved down the street. It’s about the size of a large walk-in closet and seats eighteen people all day, max.

The idea for the luncheonette was pretty straightforward: a lunch spot that we were always looking for but could never find. The method of Fred locking himself into Liverpool House with a pile of tools and a couple of minions, with me feeding them pizza through a crack in the door, worked well, so we decided to do the same with McKiernan. I did my usual collage of old and inspiring French and Canadian home magazines. Allison opened new accounts, and Fred began building. It was ready in two months.

Brunch at McKiernan consists of dishes like a half lobster with poached eggs and baloney, smorgasbords, and breakfast sandwiches made with homemade sausage. For lunch, we serve classic soups, sandwiches, and salads for women with sensible shoes. At night, McKiernan is almost like a Joe Beef private room for parties. But when it’s not rented, it acts as the local quiet spot with a new menu nightly. One unique aspect of McKiernan is that Fred’s woodworking shop, complete with drafts and train calendars, lies directly below, in the basement. It is also rumored to have a tunnel that connects the three restaurants: a mythical mine shaft or “tunnel of pleasure.”

Now, five years later, we’re on “the compound,” sharing what seems like a massive backyard, with cooks running between the three restaurants, speaking Frenglish, and finishing service with a drink under the lights of the baseball field in the back. The “we” has gone from a staff of six at the beginning to thirty-five as we write this book.

The idea of having three restaurants next to one another on the same street may seem weird to some people. The restaurants rose from a desire for something different and all our own. Everything else happened from that. We wanted more room, so we built Liverpool House. We wanted to smoke everything ourselves, so we built a smoker in the backyard. Fred wanted Joe Beef to have its own vegetables, so we built (and continually care for) a garden. The idea of a greenhouse came up, and within a week, we (along with John Bil on his “vacation”) had finished it.

Joe Beef was created with nostalgia in mind, with the sense that the original paint is probably better than what is covering it and that the classic L’art culinaire français has almost more use than any cooking manual that’s come after it. We’re inspired by the traditions of Quebec and what’s in our own backyard. The following recipes are the Joe Beef classics. —DM

Fois Gras Parfait with Madeira Jelly

Makes 10 to 12 ramekins

This dish, which calls for a whole fresh duck foie gras, has been on our menu since day one. We like it with a thin layer of our Madeira Jelly poured on top, but almost any compote, jam, or jelly can be served alongside.

1 whole fresh duck foie gras, about 18 ounces (500 g)

4 cups (1 liter) milk

1½ cups (375 ml) whipping cream (35 percent butterfat)

1 tablespoon brandy

1 teaspoon sugar

Salt and pepper

6 egg yolks

2 whole eggs

Boiling water, as needed

Black truffle shavings for topping (optional)

Madeira Jelly (recipe follows)

Toasted brioche or pain de campagne (country bread) for serving

1. Place the liver in a large bowl, and pour the milk over it. Cover and set aside at room temperature for 1½ to 2 hours. You want the liver to soften and to look and feel like a giant piece of Silly Putty. When you have that consistency, take the liver out of the bowl, put it on paper towels, and pat it dry. Throw out the milk.

2. Preheat the oven to 325°F (165°C). Put the cream in a small saucepan and place it over high heat.

3. Now, here’s the weird part: Using a table knife, split the liver in half lengthwise. There will be veins and nerves and bile ducts. Basically, anything you see that is red or green should be taken out. It’s not a big deal if you don’t remove it all. Just get what you can. Pat both halves dry.

4. Cut the liver into cubes. The smaller they are, the easier on your blender or food processor. Put the cubes in a large, wide bowl; add the brandy, sugar, and a healthy sprinkle each of salt and pepper; and turn the cubes gently to coat them on all sides.

5. Put the cubes in a blender or food processor and pulse until the cubes are all gone and you are left with a creamy consistency. Add the egg yolks and whole eggs. The cream will be at a boil by now, so take it off the burner. You want to pulse for about 10 seconds, add some cream, pulse for 10 seconds more, add a little more cream, and then pulse again. Continue like this until all the hot cream is added and the liver is smooth and creamy, like a frothy McDonald’s milk shake.

6. Pour the liquid liver through a coarse-mesh sieve into a bowl with a spout or a large measuring pitcher. You need to strain out any nasty bits you may have missed before. Divide the mixture evenly among 10 to 12 ramekins or jam jars, ½ cup (125 ml) each. Select a baking dish just large enough to hold the ramekins without touching (you may need to use 2 baking dishes or bake the parfaits in batches), and line the bottom with a double layer of paper towels. Place the ramekins in the baking dish.

7. Pull out the oven rack, put the baking dish on it, pour the boiling water into the baking dish to reach about halfway up the sides of the ramekins, and push in the oven rack. Bake for 25 minutes, then pull out the oven rack and lightly shake the ramekins. If the liver wobbles stiffly, you’re ready. If not, push in the rack and bake for another 5 to 8 minutes, then test again.

8. When the parfaits are ready, remove them from the baking dish and let them cool to room temperature. If you are using the truffle shavings, arrange some on top of each parfait. Cover the parfaits and refrigerate until chilled. Top with the jelly as directed, then re-cover and return to the refrigerator as directed. The parfaits will keep for up to 4 days. Remove from the refrigerator about 10 minutes before serving with the toasted brioche.

Makes 1 cup (250 ml)

6 sheets gelatin

1 cup (250 ml) Madeira wine

6½ tablespoons (100 ml) water

2 tablespoons maple syrup

1 teaspoon white wine vinegar

1. Bloom the gelatin sheets in a bowl of cool water to cover for 5 to 10 minutes, or until they soften and swell.

2. In a small pot, combine the wine, water, maple syrup, and vinegar over medium heat. When hot, remove from the heat. Gently squeeze the gelatin sheets, add to the wine mixture, and whisk until completely dissolved.

3. If using for the parfaits, spoon a thin layer of the warm liquid over each chilled parfait and refrigerate for 15 minutes to set the jelly. The layer should be ⅛ inch (3 mm) thick. If not using for the parfaits, pour the warm liquid into a jar with a tight-fitting lid and refrigerate. It will keep for up to 7 days. When serving this jelly on a plate, we press it through a ricer to give it a mound of kryptonite appearance.

Serves 2 for dinner (2 bones per person) or 4 for lunch (1 bone per person)

Nowadays, every restaurant seems to have marrow on the menu. But for decades, the after-work evenings of local chefs have usually ended up (drunkenly) in the same place, L’Express, with its infamous three large trunks of marrowbone, sel gris, and rounds of cabbage. There is something about hot marrow in a cold climate; it’s the kind of thing you want to eat when snow is melting off your boots.

Essentially a thick French peasant (cultivateur) vegetable soup with marrow, this recipe is a Joe Beef winter standard. Marrowbones are always from the hind legs of the animal. You want them crosscut, which reveals a long tube of marrow. If you have purchased them frozen, thaw them in the fridge first.

4 crosscut marrowbones, each about 6 inches (15 cm) long

Salt and pepper

3 tablespoons unsalted butter

½ cup (45 g) or 6 slices diced bacon

⅓ cup (50 g) diced onion

⅓ cup (55 g) diced, peeled potatoes (Yukon Gold or fingerling)

⅓ cup (55 g) diced carrots

⅓ cup (25 g) diced cabbage

⅓ cup (45 g) tiny cauliflower florets

⅓ cup (25 g) chopped leek, white part only

⅓ cup (55 g) diced white turnip

⅓ cup (45 g) diced zucchini

6 sugar snap peas, thinly sliced on the diagonal

2 sprigs thyme

2 cups (500 ml) chicken stock

1 teaspoon cider vinegar

1 tablespoon Dijon mustard, plus more for serving

Canola oil for searing

1 clove garlic, smashed

Fresh flat-leaf parsley leaves for garnish

Italian bread, as much as you want

Sea salt for serving

1. When you get the marrowbones home, put them in a big bowl with water to cover and 2 tablespoons salt. They should sit refrigerated for a minimum of 4 hours or as long as overnight.

2. To prepare the vegetables, place a cast-iron pot over medium heat and add 2 tablespoons of the butter. Once it starts to bubble, add the bacon. Let the bacon crisp up for 2 minutes, and then add the onion. Let the onion cook for a couple of minutes, stirring now and again, and then bomb the rest of the vegetables in except for the zucchini and snap peas. Cook the vegetables for about 5 minutes, stirring occasionally. Base the cooking on the potatoes, as they will taste the worst if they are not cooked through. In the last minute of cooking, add the zucchini and snap peas.

3. Add 1 teaspoon salt, 1 thyme sprig, and a pinch of pepper to the pot, then pour in the stock and bring to a boil. Cook for 2 minutes and add the vinegar. At the last minute, add the remaining tablespoon of butter and the mustard, mixing well. Season with salt and pepper and set aside over very low heat.

4. Now for the bones. Preheat the oven to 425°F (220°C). Drain the bones and pat them dry. Put a large ovenproof pan over high heat. Pour in a thin film of canola oil, and add the garlic and the remaining 1 thyme sprig. Cook, stirring, for 1 minute. Add the bones, marrow side down, and sear for 2 minutes. You are not looking for color, just a bit of heat penetration. Flip the bones marrow side up and put the pan into the oven. Roast for 12 minutes. We suggest using a thermometer to check the core of the marrow for doneness. It should register 140°F (60°C). A knife should penetrate the marrow easily. If the bones wobble and tip over, loosely crumble a sheet of foil and nestle them for sturdiness.

5. Take the bones out of the oven and place 1 or 2 bones, cut end up, in each shallow soup bowl. Divide the vegetable mixture among the bowls. Garnish with the parsley. Serve with the bread, mustard, and sea salt.

Serves 2

We take this name from an old Iron Chef episode when the host declared “Battle Homard Lobster!” Yes, homard and lobster mean the same thing (like “minestrone soup”).

Among other things that don’t make any sense: this is probably the most popular Joe Beef dish.

8 quarts (8 liters) plus 2 cups (500 ml) water

Salt and pepper

1 live lobster, weighing about 2½ pounds (1.2 kg)

2 portions spaghetti

1 tablespoon olive oil

2 cups (500 ml) whipping cream (35 percent butterfat)

1 teaspoon unsalted butter

2 tablespoons brandy

1 sprig tarragon

1 clove garlic, smashed

3 slices slab bacon, cut into matchsticks and crisped in a pan

Fresh parsley, julienned, for garnish

1. Start by dividing the 8 quarts water evenly between 2 pots. Add 2 tablespoons salt to each pot, and bring both pots to a rolling boil. (One is for the lobster, and the other one is for the spaghetti.)

Lobsters live in the sea, and the best lobster you’ll ever eat will be when you are on a ship or near the shore and the lobster is boiled in seawater. So, before you add the lobster, salt the water. When it is as salty as the sea, slide in the live lobster. You need to cook a lobster for about 5 minutes per pound (455 g), which is about 12 minutes for this lobster. If you don’t want to look at the live lobster as it boils, you are probably someone who likes to have sex with the light off. That’s okay.

2. Measure the spaghetti. To do that, make the size of a quarter with your thumb and index finger; 1 portion of pasta is what fits into that “hole.” Measure 2 portions and add them to the second pot of boiling water. Cook the pasta according to the instructions on the package. We don’t make our own spaghetti, so we don’t expect you to, either. Drain it, then disregard the “canons of pasta” and go ahead and rinse it under cold running water. Toss it with the olive oil so it doesn’t stick together and keep it at room temperature nearby.

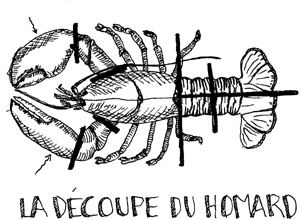

3. The lobster will be cooked by now. With your trusty long tongs, take it out of the water and put it in a bowl. Let it cool down until you can touch it with your hands, then remove the claws and the knuckles. Crack the claws with a knife or with a cracker, whichever you feel most comfortable using. Take the tail off the torso and crack it in two. (See this diagram to see how to cut the lobster.)Everything is still in the shell, and you want to leave it like that. Put the claws, knuckles, and tail pieces in a bowl and put the bowl aside.

4. Now you will be left with the torso. Hack it into 4 or 5 rough chunks with a cleaver. If that’s too dramatic, use a large knife. Keep them separate from the other pieces.

5. Next comes the sauce: In a large stockpot, combine the torso pieces, cream, butter, brandy, tarragon, garlic, and the remaining 2 cups water. Place over medium heat until the mixture starts to bubble. Reduce the heat to very low and simmer gently for 30 minutes, making sure it doesn’t reduce too much. You need about 1 cup (250 ml) liquid left.

6. Filter out all the parts, toss them away, and keep just the cream. You don’t want the cream runny; instead, it should nicely coat the back of a spoon. Season with salt and pepper.

7. In a large, shallow pan, warm together the lobster cream and the lobster pieces over medium heat. Add the spaghetti and bacon and twirl all the ingredients around with a wooden spoon for 3 to 4 minutes to heat through. Garnish with the parsley and serve family style (turn on the TV and start arguing).

Serves 2

The great thing about this recipe is that even if you mess it up (which is tough to do), you still have a delicious mushroom and bacon cream that you can pour on toast and call it a day. This is a classic coddled egg but with much more garnish.

8 ounces (225 g) chanterelle or morel mushrooms

3 tablespoons unsalted butter

1 French shallot, thinly diced

6 slices bacon, diced (about 1⅔ ounces/50 g)

Salt and pepper

½ cup (125 ml) whipping cream (35 percent butterfat)

½ cup (125 ml) Chicken Skin Jus, Beef Shank Stock, or chicken stock, reduced to ¼ cup (60 ml)

1 tablespoon vin jaune or dry sherry (optional)

2 eggs

Buttered toasted bread wedges for serving

1. In a frying pan, sweat the mushrooms with the butter over medium heat for about 2 minutes, or until the mushrooms have released their water. Add the shallot, bacon, and a pinch each of salt and pepper and simmer for 5 minutes.

2. Meanwhile, ready a bain-marie: place 2 ramekins, each about ⅔ cup (160 ml), in a small pan. Fill the pan with water to reach about halfway up the sides of the ramekins. Take the ramekins out and put the pan of water on to boil.

3. Meanwhile, add the cream, stock, and vin jaune to the mushrooms and cook over medium heat, stirring occasionally, for 5 to 7 minutes, or until the cream has reduced by one-third.

4. Fill each ramekin two-thirds full with the cream mixture. Crack 1 egg onto each ramekin, nesting it on top of the cream mixture.

5. The water should now be boiling: using tongs, carefully place each ramekin into the pan of boiling water and cover the pan immediately. Cook for 5 minutes, or until the egg whites are cooked but the yolks are still slightly runny.

6. Remove the ramekins from the pan and serve at once with the buttery toast soldiers.

Serves 4

At Joe Beef, we serve this dish with East Coast scallops, about 5 or 6 per person, with a few tablespoons of hollandaise and a nice spoonful of pulled pork on top. Such a portion is a food-cost disaster and intimidating to some*, but the scallops go down easily and they’re better topped with pork than some foamy composition. To make this dish, you are going to work on the pulled pork first, then the hollandaise, and lastly the scallops, as they take only minutes. You will end up with an excessive amount of meat, which you can use to make some pulled pork sandwiches.

2 tablespoons paprika

1 tablespoon salt

1 tablespoon pepper

1 tablespoon sugar

1 Boston butt (shoulder), 4 to 5 pounds (about 2 kg)

¼ cup (60 ml) yellow mustard

½ cup (125 ml) water

16 to 20 sea scallops (U10 size), 4 or 5 per person

Canola oil for frying

Sea salt and pepper

A Note on Pork: Boston butt (échine in French and coppa di spalla in Italian) comes from the upper part of the shoulder. It lends itself to both braising and smoking. It is a good idea to test your oven with a thermometer before attempting the long cooking called for here. You would be surprised how much effect just fifteen degrees of difference can have to a long cooking time. Put the thermometer in the oven, turn on the oven to the specified temperature, and then wait for it to preheat. Check the thermometer and adjust the oven setting accordingly.

1. To make the pulled pork, preheat the oven to 275°F (135°C). In a small bowl, stir together the paprika, salt, pepper, and sugar. Rub the meat all over with the mustard and then with the paprika mixture.

2. Put the pork in a large roasting pan and add the water to the pan. Place the pork in the oven and roast for up to 9 hours. Check the pork after 5 hours and every hour after that to make sure it isn’t burning or drying out. If the meat starts to dry out or feel like cardboard, cover it with foil. Remove the pork from the oven at 9 hours and verify that it shreds easily with a fork. The best way is to press it against the side of the pan. If it is not shredding easily, put it back in the oven for another 10 to 15 minutes. When it’s ready, remove the pork and let it cool for 10 minutes.

3. While the pork is still warm, shred it by hand or with a fork and place in a bowl. Mix the pork with as much BBQ sauce as you like and keep the bowl warm until you are ready to serve.

4. Make the hollandaise and reserve, then immediately set to work on the scallops. Pat the scallops dry with paper towels. Do not season them at this point. Outfit yourself with long sleeves and long tongs. Heat a cast-iron or nonstick frying pan over high heat. When the pan is hot, pour in the oil to a depth of ⅛ to ¼ inch (3 to 6 mm). When the oil is almost smoking, carefully place the scallops in the pan, spacing them 1 inch (2.5 cm) apart. After 1 minute, wiggle each scallop ever so gently with your tongs. After another 2 minutes, flip ’em away from you (“away” is important, so you don’t propel vast amounts of scalding oil toward you if you drop a scallop!). Remove from the heat and season the scallops with sea salt and pepper.

5. To serve, divide the scallops evenly among 4 plates. Top each serving of scallops with a few spoons of the hollandaise and then a big spoonful of the pork. Serve right away.

* This is true for most people, except for our friend Dan “The Automator” Nakamura, who we have seen eat four Joe Beef main courses, followed by a “snack” of Big Ed burgers, poutine (fries, gravy, and cheese curds), and hot dogs four hours later at Montreal’s Moe’s diner. By himself, he can decimate the food reserves of a small nation, bringing famine upon its inhabitants. Sir, we tip our hat to you.

Arctic Char for Two with Gulf of St. Lawrence Snow Crab.

Serves (you guessed it) 2

Some chefs have decided cedar-planked fish is out of fashion, but we are still making it into the 2000s for two reasons: because it’s delicious and because our friend Mathieu, who is an amazing sculptor, will sometimes show up with some pretty radical cedar boards.

Before starting this recipe, it’s a good idea to fill up the sink and soak your cedar board in cold water for as long as you can. This prevents a fire and makes the board a perfect steam generator for cooking the fish.

12 ounces (340 g) Gulf of St. Lawrence snow or Jonah crabmeat (frozen is good as long as you drain it), flaked and checked for bits of shell and cartilage

2 tablespoons minced fresh chives

2 tablespoons minced fresh dill

1 egg

1 slice white bread, cut into small cubes

1 tablespoon Dijon mustard

2 tablespoons chopped capers

Salt and pepper

1 artic char (rainbow trout works too), 2 to 2½ pounds (about 1 kg), boned from inside by the fish guy (butterflied and pin boned)

1 or 2 slices bacon

3 bay leaves

3 tablespoons canola oil

Wax Beans and Clams for garnish (recipe follows), optional

1. Preheat the oven to 400°F (200°C).

2. To make the crab stuffing, in a bowl, combine the crab, chives, dill, egg, bread, mustard, and capers and mix gently. Season lightly with salt and about 6 turns of pepper.

3. Stuff the crab mixture into the fish cavity and cover the opening with the bacon slices—like a bacon fence—to hold the stuffing in place. Tie with kitchen twine in 4 or 5 spots down the fish to hold everything in place. Sneak those bay leaves under the twine. Drizzle the oil over the fish, and season again lightly with salt and pepper.

4. Bake for 35 to 40 minutes, or until a metal skewer inserted in the thickest part of the fish and then withdrawn is hot when you touch it to your chin. If you have an instant-read thermometer, that’s about 140°F (60°C).

5. Remove the fish from the oven, transfer it to a platter, and snip the twine. Using a serrated knife, slice the fish along the twine grooves. Bring the whole fish on the platter to the table and serve each piece of fish with a heaping spoonful of beans and clams on the side.

Serves 4

¼ cup (55 g) unsalted butter

24 small clams such as little-necks, savoury (aka varnish), or manila, well scrubbed and free of sand

1 pound (455 g) yellow wax beans, trimmed and cut in half crosswise

¼ cup (60 ml) dry white wine

1 teaspoon chopped garlic

½ teaspoon chopped fresh chile

1 teaspoon smoked paprika

¼ cup (40 g) whole roasted almonds

1 tablespoon chopped green onion

Salt and pepper

1. In a large frying pan or sauté pan, melt half of the butter over medium-high heat. Add the clams, beans, wine, garlic, chile, and smoked paprika. Cover and cook for about 5 minutes, or until the clams open. Lift the lid and peek occasionally to make sure the pan doesn’t go dry. If it does, add a little water.

2. Uncover and pick out and discard any clams that failed to open. Add the remaining butter, the almonds, and the green onion and toss to mix evenly and melt the butter. Season with salt and pepper and serve right away.

Makes 1 sandwich

When we opened Joe Beef, we made all kinds of promises, oaths of sorts: no cranberry juice, we would wash dishes ourselves, we would stay open on Monday nights. We also said we would always have (at least) one breakfast item on the dinner menu. Of course, we are closed Mondays and never do the dishes ourselves, but we do always have one breakfast item on the menu. Oh, and we still don’t serve cranberry juice.

We see foie gras the same way we see skateboarding: we had a phase, like most everyone. But then it stopped, and now it’s here and there and we enjoy it in small doses. If you come to town and want to feast on foie gras everything, make a pit stop at Au Pied de Cochon; they are good friends and do it better than anyone.

Our favorite way to serve foie gras is with a breakfast-sausage patty or with peameal bacon, a well-peppered over-easy egg, and an English muffin. Add a dash of maple mustard and you’re happy, whether it’s 7:00 A.M. or 7:00 P.M. (You’ll have plenty of mustard left over, but that’s okay. It’s good with everything from salmon to corn dogs.) Remember, when you sear foie gras, be generous with salt, use a good pan, and most important, be prepared for a smoke show. Work fast and have a tray and tongs at hand before you start.

MAPLE MUSTARD

¾ cup (230 g) maple syrup

½ cup (125 ml) Dijon mustard

1 tablespoon mustard seeds

½ teaspoon pepper

2 thin slices Canadian back bacon or Peameal Bacon

1 egg

1 English muffin, split

2 tablespoons canola oil

4-ounce (115-g) piece fresh duck or goose foie gras, ¾ inch (2 cm) thick

Salt and pepper

1. To make the maple mustard, bring the maple syrup to a boil in a heavy saucepan over medium-high heat and boil for about 6 minutes, or until the bubbles increase in size. Remove from the heat, let cool for about 3 minutes, then whisk in the prepared mustard, the mustard seeds, and the pepper. Let cool completely before using. Maple mustard stores well in a tight-capped container in the fridge for at least a couple of weeks.

2. The best thing to have for this operation is one of those plug-in flat, nonstick griddles, the kind the tasting ladies have in the grocery store. You can cook your egg, bacon, and muffin on the griddle while you blast the liver on the stove top. Preheat the oven to 350°F (180°C); this is to keep the bacon warm after cooking or to blast the foie if need be. Turn on the griddle and set to medium-high heat. When the griddle is ready, cook the bacon until the edges are golden brown and lightly crispy, fry the egg over easy, and toast the cut sides of the muffin.

3. Heat the oil in a frying pan over high heat. When the frying pan is superhot, add the liver and cook, turning once, until nicely colored. You want a good color on the foie gras, kind of like the skin of a roasted chicken. This will take only a minute or two total in a very hot pan. Remember to flip the liver away from you so you don’t splash your belly. Carefully transfer the liver to a baking sheet. If the liver is still hard to the touch, put it in the oven for a minute or two. The fat that collects in the baking sheet (but not the fat from the frying pan) is good to drizzle on the muffin.

4. Now build your sandwich: start with a muffin half, cut side up, and top it with the bacon, the egg, and the foie. Drizzle the stack with a little mustard, sprinkle with salt and pepper to taste, and top with the other muffin half.

Serves 4

Not long ago, restaurants were just fun places to eat out—not the foodist temples of today. And they were often an ode to the owner’s homeland, hobby, or previous livelihood: a ski or fishing lodge, a Bahamian beach hut, a Chinese pagoda. At the top of our list is the stube, the Austrian ski shack with crossed skis hung over the mantel, beer steins, pretzel buns as bread, schnapps, and kabinnet. The menus here would invariably feature sides of mustard in glass jars, parsleyed potatoes, krauts and wursts of all kinds, and, ultimately, the schnitzel—crisp and hot and overlapping the plate like Dom DeLuise on a bar stool.

We include schnitzel on the Joe Beef menu twice a year: in the spring with peas, cream, and morels, and in the fall with chanterelles, eggs, and anchovies (of course). Ask your butcher for 4 large, pounded schnitzels. Sizewise, default to your biggest pan. You can top the schnitzel with Oeufs en Pot, or with a plain fried egg with a lemon wedge alongside.

3 cups (385 g) all-purpose flour

Salt and pepper

4 eggs

1 cup (250 ml) sour cream

¼ teaspoon freshly grated nutmeg

4 cups (170 g) panko (Japanese bread crumbs), pulsed for a few seconds in a food processor until the texture of regular bread crumbs

1 cup (115 g) grated sbrinz or grana padano cheese

4 large pork schnitzels (loin cutlets), pounded by the butcher to ¼ inch (6 mm) thick

¼ cup (60 ml) canola oil or more if needed

1. Prepare 3 flat containers, each big enough to contain 1 schnitzel at a time. Put the flour and a good pinch each of salt and pepper in the first container. In the second container, whisk together the eggs, sour cream, nutmeg, and another good pinch each of salt and pepper. In the third container, mix together the processed panko and the cheese.

2. Dip a schnitzel in the flour and shake off the excess; drop it in the egg mixture and drain off the excess; and lay it in the third container with the panko mixture and coat it well. Shake off the excess crumbs and put it on a platter. Repeat with the remaining schnitzels, then put the platter, uncovered, in the fridge, and leave it to dry a little.

3. Heat the oil in a big frying pan over medium-high heat. Do not wait until the oil smokes, but it should be hot enough so that a pinch of crumbs sizzles on contact. Place 1 schnitzel in the pan. Remember to lay it down away from you, so you don’t splash yourself. Cook, turning once, for 3 minutes on each side, or until golden brown. You want to maintain a steady sizzle the whole time the schnitzel cooks, but you don’t want it to overcolor. Transfer to paper towels to absorb the excess oil, and season with salt and pepper. Repeat with the remaining schnitzels, adding more oil to the pan if needed.

4. Serve the schnitzels one at a time as they are ready, or leave them on the paper towels and place in a low oven until serving.

Serves 2

This is one of our favorite dishes from the old classic French repertoire, essentially a big moist meatball served on a bone. According to legend, Pojarsky (or Pojarski), a favored innkeeper of Czar Nicholas, was made famous by his killer meatballs re-formed on a veal chop bone. Serve with a frond of blanched fennel.

4 large pats unsalted butter

¼ cup (8 g) dried porcini mushrooms, hydrated in warm water to cover, drained, and chopped

1 shallot, finely chopped

1 clove garlic, finely chopped

1 pound (455 g) ground veal

Leaves from 1 sprig thyme

¼ cup (15 g) day-old white bread crumbs in ¼-inch pieces soaked in ¼ cup (60 ml) milk for 15 minutes

1 egg, lightly beaten

1 teaspoon salt

1 ball (size of a fist) caul fat, thawed in the refrigerator if frozen and soaked in cold water until it can be gently stretched flat

2 veal chop bones or lamb chop bones obtained from a butcher (optional, but without the bones, you have lonely meatballs)

Fennel for garnish

1. Preheat the oven to 450°F (230°C).

2. In a frying pan, melt 2 pats of butter over medium heat. Add the mushrooms, shallot, and garlic and sweat for 4 or 5 minutes, or until soft. Let cool for 5 minutes.

3. In a large bowl, combine the veal, porcini mixture, thyme, soaked bread, egg, and salt. Mix together with your hands. It’s wise to have a little hot pan on a burner, so you can cook and test a spoonful for flavor, then adjust the seasoning if needed.

4. Divide the mixture in half, and shape each half into a ball. Flatten the balls a bit and then shape each one to look like a large chop. With a sharp knife, cut the caul fat in half, and wrap half around each “chop.” Finally, poke a hole at one end of each “chop,” and stick a bone into each hole.

5. Drop the remaining 2 pats of butter onto the bottom of a large cocotte or other heavy ovenproof pot. Carefully lay the “chops” side by side in the pot. Place in the oven and cook for 30 to 40 minutes, basting with the butter every 4 or 5 minutes, until sizzling and fragrant, and the caul fat has melted down.

6. In the meantime, bring a small pot of water to a boil over medium-high heat. Add the fennel and blanch for 2 minutes.

7. When the veal is ready, toss the fennel in the cooking fat. Bring the cocotte to the table and serve at once.

Serves 6 to 8

In Quebec, only two real game meats can be legally sold, caribou from the great north and hare snared in the winter. The taste of these meats is surprising at first, the incarnation of the word “gamey,” but like truffles or blue cheese, it becomes what you crave.

Many little classic Parisian restaurants offer this dish in season, and there are as many ways to cook it as there are chefs. The basics are wild hare (lièvre), red wine, shallots, thyme, and garlic. The rest can vary. At Joe Beef, we use both hare and rabbit. D’Artagnan (www.dartagnan.com) ships in-season Scottish game hare that we have tried. It’s gamey all right, but it’s the real McCoy. If you can’t find a hare, you can use all rabbit. Count on two days to prepare this recipe. It should yield six to eight portions, and it freezes well.

FIRST DAY

1 small rabbit, 2 to 2½ pounds (about 1 kg), quartered

1 hare, about 1¾ pounds (800 g), quartered and the blood collected if possible and kept in the fridge

1 chunk bacon, about 9 ounces (250 g)

1 veal trotter (ideally) or 2 pig’s trotters (not the leg, just the foot, about 8 inches/20 cm long)

2 large carrots, peeled

2 celery stalks

1 bouquet garni of 1 sprig each parsley, thyme, bay leaf, and peppercorn

1 (750 ml) bottle sturdy red wine such as Merlot or Cabernet

¼ cup (60 ml) brandy

Salt and pepper

SECOND DAY

SAUCE

¼ cup (25 g) finely chopped French shallots

3 tablespoons unsalted butter

Leaves from 4 sprigs thyme

1 bay leaf

4 juniper berries

1 clove garlic, minced

6 tablespoons (90 ml) brandy

2 cups (500 ml) sturdy red wine such as Merlot or Cabernet

1 tablespoon cocoa powder

3 cups (750 ml) reserved cooking jus from first day

MATIGNON

10 French shallots, finely diced

3 cloves garlic, minced

¼ cup (55 g) unsalted butter

2 tablespoons chopped fresh flat-leaf parsley

Salt and pepper

TO BUILD

6 to 8 slices fresh duck or goose foie gras, each about 3½ ounces (100 g) and ¾ to 1 inch (2 to 2.5 cm) thick

Salt and pepper

12 ounces (340 g) caul fat, thawed in the refrigerator if frozen and soaked in cold water until it can be gently stretched flat

1 or 2 fresh or canned black truffles, thinly sliced (optional)

Unsalted butter for baking dish

FINISHING SAUCE À LA ROYALE

1 (750 ml) bottle sturdy red wine such as Merlot or Cabernet

Reserved cooking jus from first day

1 tablespoon whipping cream (35 percent butterfat)

1 tablespoon red wine vinegar

1 tablespoon brandy

Salt and pepper

¼ cup (55 g) unsalted butter, cut into 1-inch pieces

2 egg yolks

The reserved blood (optional, if you have it)

1. Preheat the oven to 275°F (135°C). In a big, enameled cast-iron pot, combine the rabbit, hare, bacon, veal trotter, carrots, celery, bouquet garni, wine, and brandy. Season with salt and pepper and add water to reach 1 inch (2.5 cm) below the top of the meats.

2. Cover the pot, place in the oven, and bake for 9 hours, or until the meats begin to fall apart. Check the water level every now and again and add more water if it begins to drop.

3. Remove the pot from the oven and carefully transfer the meats and the trotter to a rimmed baking sheet and let cool. Strain the liquid into a clean bowl and discard the solids. Cover the bowl and refrigerate.

4. Shred the meat away from the hare and rabbit bones, keeping it in big chunks. Be careful as you work, as both meats are notorious for their tiny bones, which can pose a choking risk. Remove the meat from the trotter; discard the gelatin, skin, and bones; and chop the meat finely. Shred the bacon. Cover and refrigerate all of the meats.

1. To make the sauce, in a 2-quart (2-liter) saucepan, sweat the shallots in the butter over low heat for 4 or 5 minutes, or until fragrant and translucent. Add the thyme, bay leaf, juniper berries, and garlic, and sweat for 2 minutes more. Add the brandy to deglaze the pan.

2. Turn the heat to medium. Add the wine and cocoa powder, stir, and then cook for 15 to 20 minutes, until the sauce turns syrupy.

3. Add 3 cups of the reserved cooking jus and cook for 20 to 25 minutes, until the sauce is reduced by half. Remove the pan from the heat and strain the sauce through a fine sieve, pressing on the shallots to extract the pulp.

4. To make the matignon, in a sauté pan, sweat together the shallots and garlic in the butter over medium heat for 4 to 6 minutes, or until fragrant and translucent. Stir in the parsley and season with salt and pepper. Set aside.

5. To build the dish, season the foie gras slices on both sides with salt and pepper. Place a large frying pan or sauté pan over medium-high heat. When the pan is hot, add the foie gras and sear for 1 minute on each side. Transfer to a plate and let rest. Reserve the fat that collected in the pan for adding to the meat mix or the sauce.

6. In a bowl, combine the meat mixture, the matignon, and enough of the sauce to moisten the dish. Season with salt and generously with pepper, then give the mixture a once-over again for bones.

7. Preheat the oven to 400°F (200°C). Cut 6 to 8 pieces of caul fat each the size of a legal letter, and fold each piece in half. Shape the meat mixture into 12 to 16 patties each the size of a pack of American cigarettes. Place 1 slice of foie gras between 2 patties, then arrange a line of truffle slices on the top. Wrap the stack in a folded sheet of caul fat, cutting away the excess and tucking the ends under. The truffle slices will be visible through the caul fat layer.

8. Butter a baking dish just large enough to hold the wrapped stacks side by side, and arrange the stacks in it. Place in the oven and bake for 35 minutes, or until slightly golden.

9. Just before the stacks are ready to come out of the oven, make the finishing sauce. In a saucepan, reduce the wine to half over medium heat. Add the remaining reserved cooking jus and cook until reduced to 2 cups (500 ml). Add the cream, vinegar, and brandy; mix well and season with salt and pepper. Bring to a boil, whisk in the butter, a piece at a time, and remove from the heat. In a bowl, whisk together the yolks and the blood, add to the sauce, and buzz the sauce with a hand blender until smooth. (At this point, you cannot reheat the sauce above about 180°F/84°C or it will separate.)

10. For each serving, place a spoonful of the potatoes on a warmed plate, and put a portion of lièvre on each mound of potatoes Break an opening in the top of each portion, and spoon some sauce inside. Keep the rest of the sauce handy. Serve at once. You will find it is necessary to drink un grand Bourgogne with this dish.

Serves 2

Occasionally we refer to Le Repertoire de la Cuisine, the little brown book of classic French recipes, to find inspiration for the Joe Beef menu. It’s a gold mine of forgotten culinary knowledge, including the sauce paloise, a classic variation on sauce béarnaise that uses mint instead of tarragon. You decide on the meat. If you freak on kidneys, use kidneys. We like it on a mutton chop, one chop per person.

½ cup (50 g) diced French shallots

½ cup (125 ml) white wine vinegar

2 tablespoons dried mint

2 tablespoons cracked peppercorns

6 egg yolks

1 cup (225 g) unsalted butter, melted

Salt and pepper

Leaves from 4 sprigs mint, chopped

SAUSAGE

8 ounces (225 g) ground pork

8 ounces (225 g) ground lamb

1¼ teaspoons salt

1 teaspoon wild dill or fennel seeds

1 clove garlic, finely chopped

1 teaspoon Sriracha sauce

½ teaspoon pepper

1 tablespoon cold water

Watercress for serving

Apple Vinny for serving

1. To make the sauce, in a nonreactive saucepan, combine the shallots, vinegar, dried mint, and peppercorns over high heat. Cook, stirring occasionally just to keep the sides of the pan clean, until reduced by half. Strain the reduction. This is the beginning of your paloise. Discard the solids.

2. In a saucepan, whisk together the yolks and the reduction. Now, create a double boiler—a small pan (or a heatproof bowl) above a larger pan—which is a good way to whisk your delicate sauce over high heat: Pour water to a depth of about 2 inches (5 cm) into a large pan, bring to a boil over high heat, and rest the small pan holding the egg yolk mixture over (not touching) the water in the large pan. Start whisking continuously.

3. Now is a good time to whip out an instant-read thermometer. You don’t want the mixture to go above 183°F (85°C) or the eggs will curdle. As the eggs start heating up, start slowly pouring in the butter while continuing to whisk constantly. After all of the butter is in, add a couple tablespoons of hot water to loosen up the sauce a bit, then add a pinch or two of salt and pepper. Keep the sauce in a warm spot but not on a burner. Have the fresh mint on hand.

4. To make the sausage, turn on the broiler or light a charcoal or gas grill. In a bowl, combine the pork, lamb, salt, dill, garlic, Sriracha sauce, pepper, and cold water. Mix together well with your hands. Shape the mixture into small torpedo-shaped sausages about 2 inches (5 cm) long.

5. Place the sausages on a rimmed baking sheet and slip the sheet under the broiler, or place on a grill rack. Cook, turning as needed, for 4 to 5 minutes, or until browned on all sides.

6. Put the sausages on a platter and immediately turn to the paloise. Add in the fresh mint and stir well. Serve the sausages with the paloise—from a nice old sauce tray, if possible—with the watercress dressed with Apple Vinny on the side.