It was May 3, 2010, and the plan was to meet at a nondescript bar in the basement of Place Bonaventure, Montreal’s central station. When I arrived, Fred, Dave, and Jennifer (the photographer for this book) were on their second round of Campari and soda and their first plate of wings. Fred had a new recruit for his sermon of the train, and Dave and I exchanged knowing glances.

For the last six years, I had been so brainwashed on the merits of the great Canadian railroad that the previous summer I had taken the twenty-six-hour trip (advertised as twenty-one hours) on the Chaleur route from Montreal to the tip of mainland Canada, Gaspé, where I stayed for just two nights before heading home. “You want to be sure to take it on a Wednesday, as that’s when they use the Budd [stainless-steel cars built in the 1950s by the Budd company, makers of the fabled California Zephyr], rather than the Renaissance [hand-me-downs from England purchased within the last ten years; ‘uncomfortable, narrow, and ill-equipped,’ according to Fred] equipment,” Fred advised. So I did. I had a single roomette all done in chrome and Tiffany blue paint. I ate a foie gras parfait that Fred had packed and drank a bottle of Muscat that Dave said I would need. I fell asleep somewhere near Rivière-du-Loup and woke up on the gulf of the Saint Lawrence. It was strangely one of the most exotic trips I’ve ever taken. And here I was again about to set out on a seventeen-hour train trip to Moncton on the Ocean, the oldest continuously operated train route in North America.

At the bar, Fred was showing Jen his train manuals, while Dave and I witnessed people in suits engaging in after-office affairs before taking the suburban trains back home. “I like to read about trains while on the train,” Fred was saying. You know how Trekkies probably lose their mind over the blueprint to the Starship Enterprise? That’s how Fred is with the Renaissance car operating manual. He’s just hoping there will be a mechanical breakdown and he’ll be able to live out his dreams.

We finally boarded and unloaded in our side-by-side roomettes. Now, maybe we like a stronger gin and tonic than the average person, or maybe we like the fanfare of a nice bar setup. Or, maybe we’re just drunks. Regardless, Fred brought his traveling-salesman bar kit, complete with bottles of vermouth, gin, Johnny Walker, and Fernet Branca. Knowing him well, I preempted any catastrophies by grabbing bottles of soda and tonic, olives, lemons, limes, and cherries. We had cocktails and headed to the dining car.

The city was far behind us by the time we were onto Black Forest cake and our fifth bottle of Canadian wine. This was Dave’s first time on a Canadian dining car, and knowing how much he hates to leave his family, I was surprised that he even agreed to come: “Hey, if Fred likes trains, I like trains, too.”

Finally, we withdrew to our rooms, where in the agreeable company of one another we ate peanuts and listened to notorious train lover Neil Young’s Everyone Knows This Is Nowhere on Dave’s twenty-dollar speakers. We talked about how we would approach Fred’s obsession in this book. The train lulled us sleepily and we listened patiently: “I want it to be a call to arms, a call to protect the railroad.…” —ME

The neighborhood of Point Saint Charles, or The Point, which lies directly beside Saint Henri, is one of the oldest working-class neighborhoods in the country. It is also where the Grand Trunk Railway Company incorporated in 1852, making it the oldest train hub in the country. This is where the harbor, the canal, and the railroads joined and where the row houses for the workers were crammed tight and piled high. It’s these workers, along with the sailors and wharf rats, whom we imagine frequented the original Joe Beef somewhere between the 1870s and 1880s.

Up until the area was bulldozed to make way for Expo 67, it remained a railroad haunt. A customer of ours who grew up in The Point drew us a map of the blocks around the rails. Twenty-seven bars were operating in about a four-block radius. They were set up so the men could jump off the train directly through the back door of a bar. There was the Moose Tavern, the Pall Mall, the 1 and 2, the Palomino, and the Olympic Tavern. He said you would walk into those places and they’d be buzzing with train radios and packed with men still in their work clothes, stinking of diesel fuel. The fact that we opened so close to this feels serendipitous and calming, and often reminds us of another era.

There was a time when the only way you could travel long distances in this country was by train. And the only way that the railroads could compete with one another was by the service they provided on board. They boasted smoking parlors, piano bars, barber salons, and fashion shows. The Canadian National (CN) even had an onboard radio service, the CRBC, which was the model the Crown used to set up the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation in 1936. There were noble attendants, servers, cooks, and professional bartenders who had a fully stocked bar from which they made drinks in an array of real glasses. The premade bottled Césars and potato chips you get today were probably not an option. One of the main attractions of train travel was the dining car and the quality and array of food it offered. The kitchens were not always limited centralized setups made for ease and speed. Starting as early as 1872, the Delmonico dining car, which was inaugurated in the U.S. Midwest, had a full kitchen, complete with stove tops for meats and sauces and ovens for fresh pastries. When we visited the Exporail Train Museum in Saint Constant (located a convenient twenty minutes away from Joe Beef), the archivist showed us the original cooking manuals that were given to the kitchen staff in 1912. Lake Winnipeg pickerel, crab Monte Cristo, ox tongue, Alberta sirloin with mash, Roquefort with crackers, stewed rhubarb—all dishes available en route.

Train passengers were the original locavores: It made sense that you picked up Alberta beef in the prairies and ate it outside of Calgary. It made sense that you were eating salmon as you departed Vancouver. More by necessity than choice, as the supplies for lengthy trans-Canadian trips were too heavy to carry, pickups for fruits, vegetables, and dairy were scheduled across the country, and the cooks would in turn serve only the freshest provisions in the dining car. You would eat chowder and shellfish on Atlantic lines, “lumberjack” breakfasts through central Canada, and prime beef through the prairies.

One of the things I love most about train travel is the etiquette: You get on and get settled. You freshen up, put on a clean shirt or dress. Meet for drinks in the lounge for an hour. Get off during stops for cigarillos. Eat together and retire to another lounge for a nightcap. Go to the room, get ready for bed. Go to sleep in one province, wake up in another.

Call me nostalgic, but it’s sad to think of what trains used to be, what they used to serve. Can you imagine a time when every aspect of train travel was Sunday’s best? Now the food is equal to that of what you get on airlines, and wi-fi is considered providing service. It’s when I look through my old train books or visit Exporail that the pain is really felt.

Until 1974, Canada had two national train companies: Canadian National (CN) and Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR). In 1978, after decades of losing millions on passenger routes, CN and CPR merged and the passenger lines were taken over by the highly marketed sapphire blue and gold VIA Rail. Because this is not a chapter about economic feasibility, but rather nostalgia, we’ll skip the politics and reasoning. The fact is, though the fanfare is something only to be remembered, the routes still exist and there are fine dining cars with lounges and banquettes and room to have prepackaged cheese and wine with your friends while you look out on some of the country’s most beautiful scenery. Train travel takes longer and is only slightly less expensive than flying or driving, so the only raison d’être for the train is fun. If you’re hungry, you can make the foie de veau in this book, or you can eat a can of tuna for sustenance. Likewise, if you want to go to the Gaspé, you can take the twenty-something-hour sleeper car, have wine, and meet people, or you can drive the eight-hour autoroute. Like the beauty of people buying art not for trading, taking the train is for the hobbyist in each of us. If efficiency is your only goal, then drop this book and eat a meal in a pill.

If I could take the train, somehow, each day, I would. When I am able to take the train, I often ride the metro train to the suburban train to the VIA train. And once I’m on, I never want to leave.

The following recipes are inspired by and meant for train travel. We wish we could eat these on the imaginary train ride of tomorrow. —FM

FRED’S TOP CANADIAN TRAIN ITINERARIES

1. THE HUDSON BAY

I flew to Winnipeg, took a nondescript cab to the train station, and then boarded the train at the end of the day. I was in the lounge section watching TV and thought I was alone, so I changed the curling channel after thirty minutes of boredom. Two older women with tight blue curls immediately chastised me for being so selfish. That’s when I understood the Canadian love of curling.

By Law of Treaties, you can’t be charged more than two dollars and fifty cents per freight box, so this train is a runner of sorts, with a lot of people sending provisions up north. Folks still depend on this train. Coureurs des bois (literally, “runners of the woods”) are thought of almost as folklore now, but on this route, you actually see men with long beards who trap and skin animals for a living. It’s the gateway to the north.

In Winnipeg, it was 60°F (15°C) and in Churchill -40°F (-40°C). It is practically the Arctic. I stayed in Churchill for three nights in March. During my stay I went to the Gypsy Café, which is the “fancy” restaurant in town. The counter had the strangest setup. On one side was Gatorade, on the other, Dom Pérignon. There was a slide-in light box display of the menu, with items ranging from corn dogs and poutine to caribou and arctic char.

My big highlight was going out with Claude, the Arctic ranger. His business is skidoo expeditions, which I know nothing about. He took me out, just because he had to drop the flags for the upcoming qualifier to the Iditarod dog race. I thought I had dressed for winter, but Claude schooled me by lending me sealskin gloves, giant boots, gasoline-smelling pants, and a Hezbollah-looking face mask—and I was still cold. We toured for six hours through vast tundra. Because it’s the Hudson Bay, you don’t know if you’re on ice on the bay or on the shore. He told me funny stories of French tourists crashing into one another, and showed me Arctic landmarks.

2. THE CANADIAN

In early spring, Allison was in Edmonton with her family, so I took the chance to ride the Canadian. I asked Paul Coffin to come, and, being the most relaxed guy, he said “sure.” The Canadian is the longest and most proud route, running from Toronto to Vancouver over four days. We found the Budd train milk run to Toronto. We played tourist for the afternoon: picture at the landmark CN tower, peameal bacon at the St. Lawrence market, hung with Stephen Alexander at Cumbrae’s meats. We left in the evening, around ten, and woke up the next day to real food from a real kitchen with real appliances. It’s the only train in Canada that still has a full kitchen. It is an emblematic train with a true Canadian aura. If you haven’t taken it, I highly suggest it. It is the only VIA route with a luxury option.

A few years back, our friend Adam Gollner wrote a nice piece in Gourmet magazine called “The Very Noble Train of the Huntsman,” about our fishing trip to Club Kapitachuan and the eleven-hour route to northern Quebec. This route is in some way intimate to Joe Beef. It starts almost in our backyard and goes through The Point and Saint Henri backyards. Once you leave the island, you pass by Saint-Tite-des-Caps, where there is a huge country music festival: it’s the Woodstock of RVs. Then at Hervey Junction the train splits in two, and the Saguenay makes its way to Jonquière and the Abitibi heads north to the outdoor country.

The route has trestles and tunnels, and after La Tuque, you’re in the woods. A footnote that was (understandably) left out of the Gourmet story: We took a pile of local cheese up north, not knowing that back in Montreal there was a vast listeriosis scare. Men in black came to Joe Beef and demanded that Allison show them proof that the cheese was with us, and not at the restaurant. Meanwhile, we had started on our trip home and were (very quickly) made aware that we were at ground zero of the epicenter of an Ebola-like listeriosis outbreak. We felt odd and had the worst gas and stomach pain aboard the train. We then all crawled into bed for days. Part of me still thinks it was just the booze.

4. THE CHALEUR

What a train: This silver beauty inches its way along the Saint Lawrence River and the Chaleur Bay. You spot a lighthouse a few yards away. Three hours later, the Percé Rock. As you near cities you’re moving slowly and so close to people’s homes that you can see what they are watching on TV.

I love this train; I love the name, even if VIA Rail, in a move away from emotional nostalgia, generally abandoned names for destinations, that is, Montreal to the Gaspé. And what’s a railroad claim to fame these days if it’s not romance and nostalgia? I once got out of a mean parking ticket because I mentioned to the judge that I was on the Chaleur and it ran late because of the snow. And late it was, so late in fact that the run was cancelled halfway through. Right in Matapedia we backed up and I stayed at HoJo for two nights, and then took the bus to my destination. (Everything was wrong with that: I had a nice room onboard—my Christmas gift—I was largely hung over, and a 6:00 A.M. bus ride through rural New Brunswick is my equivalent of a Twilight Zone episode.)

Anyway, the train still runs, and the sights are still as gorgeous. I suggest you pack a French aristocrat picnic and a bar case, and choose a date when the acts of God aren’t as prevalent.

Serves 4

As we write this, it seeaems much more acceptable to spend $18 for an entire appetizer than it does to spend $180 an ounce for real caviar. What makes this setup grand is the ceremonial feel it has, like something you could get on the Orient Express. Feel free to use any kind of fish eggs: whitefish, salmon, trout, or even smoked or preserved fish. It’s also crucial that what you save on the real caviar, you spend on Champagne and on an overpriced silver serving dish from eBay.

Eat it in your bed or on the bus.

BLINI

⅓ cup (40 g) all-purpose flour, sifted

⅔ cup (85 g) buckwheat flour

¼ teaspoon salt

1 tablespoon baking powder

1 egg

1 cup (250 ml) water

2 tablespoons neutral oil, plus more for cooking

1 teaspoon sugar

Melted unsalted butter for serving

1 small container mújol (Spanish mullet caviar) or Canadian or American sturgeon caviar (1 ounce/30 g per person)

4 hard-boiled eggs, peeled and whites and yolks separated and chopped (or pushed through a coarse-mesh sieve)

¼ cup (10 g) chopped fresh chives

2 lemons, halved

½ cup (125 ml) crème fraîche (see Smorgasbord)

2 tablespoons grated fresh horseradish

1. To make the blini, in a bowl, sift together the all-purpose flour, buckwheat flour, salt, and baking powder. In another bowl, whisk together the egg, water, oil, and sugar until well mixed. Whisk together the dry ingredients and wet ingredients briefly. It is better to have tiny clumps than rubbery dough.

2. Place a nonstick frying pan over medium heat and add 1 teaspoon of oil. When the pan is hot, drop in the batter by spoonfuls, forming silver dollar–size blini. When the tops begin to set, flip the blini carefully. Continue to cook until firm. They should take 2 to 3 minutes total to fry. Transfer to a warm tray and cover with a kitchen towel to keep warm. Repeat with the remaining batter. You should have about 24 blini. Just before serving, brush with melted butter.

3. To serve, place the caviar, eggs, chives, lemons, crème fraiche, and horseradish in serving dishes alongside the warm blini. Build as you see fit.

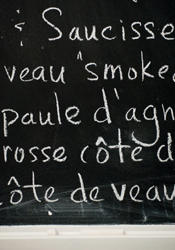

Makes about thirty 3-inch (7.5-cm) links, enough for a large family breakfast

You can make sausage links or you can make patties, which are a lazy man’s links. If you opt for links, you will need a sausage stuffer. You may also have to special order the casings from your butcher. It is a good idea to double the recipe, too, because it is easier to work with a larger amount. These are good breakfast sausages, but they also shine with kraut, lentils, or duck. Enjoy with a nice glass of Hungarian wine, or with a nice Hungarian man, i.e., artist Peter Hoffer.

1 pound (455 g) ground pork

1 pound (455 g) ground veal, turkey, or duck

½ cup (40 g) rolled oats

¼ cup (60 ml) ice water

¼ cup (75 g) maple syrup

1 tablespoon Sriracha sauce

2 teaspoons salt

2 tablespoons powdered sage

1 tablespoon pepper

1 teaspoon garlic powder

½ teaspoon ground ginger

Canola oil for frying

2 bundles ¾ to 1-inch (2 to 2.5-cm) lamb casings, if making links

1. In a large bowl, combine the pork, veal, oats, ice water, maple syrup, Sriracha sauce, salt, sage, pepper, garlic powder, and ginger. Mix thoroughly with your hands. In a frying pan, heat a little canola oil over medium heat. Fry a small test patty and correct the seasoning if needed.

2. Now, if you want to make patties rather than links, form the meat mixture into flattened golf balls. Return the frying pan to medium heat, add a little more oil, and then the patties. Fry, turning once, for about 3 minutes on each side, or until just cooked through. Serve hot.

3. If you are feeling ambitious, load the meat mixture into the sausage stuffer. Slide the casing onto the stuffing tube and begin to stuff. The casing should be full and tight, but not full enough to burst when you begin to pinch the links. Stuffing sausage takes Yoda-like patience at the beginning. That’s why most folks say screw it and make patties instead. But making your own links is a skill, and with practice, you’ll be stuffing casings like a pro. To form the links, press your forefinger and thumb together to make a slight indent in the casing about every 3 inches (7.5 cm) or every second sausage, then twist each indent about 3 turns.

4. Finally, fry the sausages in a frying pan with a little oil, turning to brown all sides, for 4 to 5 minutes, or until just cooked through. Serve hot.

Serves 2

This dish is not surprising in taste (it’s duck, sausage, and potato—what can go wrong?), nor very feminine (in other words, it’s not pretty). We like the look a lot, because the fingerlings, duck pieces, and links are all the same size and shape. This is the best way to enjoy duck in the middle of the winter.

¼ cup (60 ml) canola oil

Salt

1 boneless duck breast, a little less than 1 pound (about 420 g)

10 fingerling potatoes, parboiled and peeled

1 sprig thyme

1 French shallot, thinly sliced

1 tablespoon ketchup

¼ cup (60 ml) Beef Shank Stock

1 tablespoon unsalted butter

1. In a frying pan, heat 2 tablespoons of the oil over medium heat. Salt the duck breast on both sides and place, skin side down, in the pan. Sear for 4 minutes, then turn and continue cooking for 3 minutes on the other side; it should be medium-rare. Set the duck aside in a warm spot.

2. Pour the fat out of the pan. Return the pan to medium-high heat and add the remaining 2 tablespoons oil. Then add the potatoes, links, and thyme and cook, turning the potatoes and links every now and again, for 8 minutes. You want those potatoes to soak up all that fat the links release. Now add the shallot and ketchup and mix well. Finally add the stock and butter to the mix. Stir for another 2 minutes, just enough to warm everything up evenly.

3. Cut the duck into slices similar in size to the links. Divide the duck, spuds, and links between 2 plates, and pour the sauce from the pan on top.

Serves 2

This recipe is taken from an old Canadian National Railway menu. It became an instant Joe Beef classic, which goes to show: people love train food.

1 long slice calf liver, about 10 ounces (280 g) and 1½ inches (4 cm) thick

6 tablespoons (55 g) unsalted butter

½ cup (85 g) diced cooked ham

1 shallot, finely chopped

½ cup (40 g) finely chopped white mushrooms

1 tablespoon Cognac

Salt and pepper

½ clove garlic, minced

1 tablespoon finely chopped fresh flat-leaf parsley

½ cup (55 g) toasted bread cubes (from 1 slice stale white bread)

½ cup (55 g) grated Parmesan cheese

1 tablespoon Dijon mustard

¼ cup (10 g) chopped fresh chives

½ cup (125 ml) Beef Shank Stock

1. Preheat the oven to 400°F (200°C). With a long sharp knife, carefully slice open the piece of liver like a wallet.

2. To make the stuffing, grab a sauté pan and melt 2 tablespoons butter over medium heat. It seems like a lot of butter because it is. After 2 minutes, add the ham and the shallot. Sweat it for a minute or two and then add the mushrooms, Cognac, and ¼ teaspoon salt to draw the water from the mushrooms. Stir in the garlic, parsley, and a pinch of pepper and cook for 3 minutes. Lastly, add the bread and mix everything together. Remove from the heat and let cool.

3. Spoon the stuffing carefully into the veal wallet. Unlike a real wallet, you want this one only three-quarters full. Squeeze the top to make sure that the bottom is full. Now sew the top shut with bamboo skewers. It doesn’t have to be perfect; just shut it so the stuffing doesn’t fall out.

4. In a small cocotte or other small flameproof casserole, melt 2 tablespoons butter with a pinch each of salt and pepper over medium heat. When the butter is foaming, fit the liver in the pan and place in the oven for 12 minutes.

5. Time to make the herb crust: Melt the remaining 2 tablespoons butter, let cool, then mix with the Parmesan, mustard, and chives.

6. After 12 minutes, take the liver out but don’t turn off the oven. With a spoon, smear the buttery crust on top of the liver. Add the stock to the pan, return the pan to the oven, and bake for another 5 minutes, or until a thermometer inserted into the thickest part reads 135°F (58°C).

7. Take out the skewers, let the liver rest for a minute, then slice and serve.

Serves 6

The idea here is to get great pulled pork but in the shape of High Liner Captain’s fish sticks. If you don’t have a proper fryer, you can still do this recipe—just don’t attempt it drunk and/or naked. You can use a thick-bottomed pot and a deep-fat thermometer, and of course, have a fire extinguisher nearby. Try these sticks with any of the suggested dips for Cornflake Eel Nuggets, or serve on mashed potatoes with onion jus.

Pulled pork from Scallops with Pulled Pork

6 sheets gelatin

1½ cups (375 ml) BBQ Sauce

3 tablespoons chopped French shallots

Salt and pepper

BREADING

2 cups (255 g) all-purpose flour

2 tablespoons Old Bay seasoning (optional)

4 eggs

1 cup (250 ml) milk

Salt and pepper

4 cups (170 g) panko (Japanese bread crumbs), crushed in the bag(s) between your hands to powder a bit

Canola oil for deep-frying

1. At Joe Beef, we smoke the pork butt for 10 hours for this recipe. If you have a smoking device, we suggest you use it. But if not, no problem; just roast it in the oven as directed. When the pork is ready, shred it and set it aside; do not add the BBQ Sauce yet.

2. Bloom the gelatin sheets in a bowl of cool water to cover for 5 to 10 minutes, or until they soften and swell. Meanwhile, heat the BBQ Sauce in a large saucepan over medium heat until warmed through. Remove the saucepan from the heat. Gently squeeze the gelatin sheets, add to the sauce, and whisk until completely dissolved. Add the shredded pork to the sauce and mix well. Stir in the shallots, taste, and correct the seasoning with salt and pepper.

3. Line a rimmed baking sheet with plastic wrap. Transfer the meat mixture to the baking sheet and press well and evenly. Cover with plastic wrap and refrigerate for at least 2 hours or up to 4 days.

4. To ready the breading, set up three bowls. In a shallow bowl, mix together the flour and the Old Bay seasoning. In a second bowl, whisk together the eggs, milk, and a pinch each of salt and pepper. Put the panko in a third bowl.

5. Unmold the chilled meat mixture on a cutting board by turning the baking sheet upside down and using your fingers to gently remove the meat (it’s okay if it breaks up a little as you can re-form it with your hands). Cut the meat into fish stick–sized sticks. Now, set up the bowl assembly line. Carefully toss the sticks in the flour, then in the egg mixture, and then, with a clean hand, in the panko. If you feel unsure of the resistance of your breaded crust, you can repeat the egg and panko steps, hence doubling the crust. Lay the pork sticks on a clean baking sheet and refrigerate uncovered in a single layer for about 15 minutes to dry out a bit.

6. Meanwhile, pour the oil to a depth of 3 inches (7.5 cm) into your deep fryer and heat to 350°F (180°C). Working in batches of 5 or 6 sticks, fry for 3 to 4 minutes, until golden and crisp. (Remember to let your fryer return to its initial temperature between batches; respect that little orange light!) Remove the sticks from the oil, pat dry with paper towels, and let cool for 3 or 4 minutes. Season to taste with salt and pepper and serve.

Serves 1

George Pullman was a fervent industrialist and a train man. He created the sleeping car, the hotel car, and eventually the dining car. Some say the Pullman sandwich loaf was designed after his cars. Others say it was designed to fit into the cube-shaped train shelves. Either way, this is an easy dish we would love to eat for breakfast—on the train, of course. This recipe makes one serving; use up the rest of the Pullman loaf making more boxes.

1 unsliced loaf day-old Pullman (sandwich) bread (works best if the bread is cold)

2 tablespoons unsalted butter

1 smoked mackerel fillet or a few slices smoked salmon

3 eggs

2 tablespoons whipping cream (35 percent butterfat)

Salt and pepper

1 tablespoon crème fraîche or sour cream

1 teaspoon chopped fresh chives

Few shavings fresh horseradish

Caviar for garnish (optional)

1. Basically, what you are doing here is building a big box of buttered bread, a little home for your eggs. Start by removing a slice about 2 inches (5 cm) thick from the loaf. Cut off the crusts from the slice, then remove its core by cutting a square hole in the middle. Keep in mind that the hole has to be big enough to contain three scrambled eggs and the delicious fish.

2. Preheat the oven on a low setting. Melt 1 tablespoon of the butter in a nonstick frying pan—or better, use a breakfast griddle—over low heat and slowly color the box on all sides. Put the box on a plate along with the fish and place the plate in the oven to heat the fish and keep the box warm.

3. In a small bowl, whisk together the eggs, cream, and a little salt and pepper. Scramble the eggs over low heat in the remaining butter in the same pan (or a new pan if you used a griddle for the bread). When they are almost set, nonchalantly add the warm pieces of fish. Heat the ensemble through.

4. Place the ensemble in the box. Garnish with the crème fraîche, chives, and horseradish. We also find a teaspoon of caviar to be a nice touch.

Makes about 4 pounds (1.8 kg)

Even though peameal has nothing to do with the bacon we know and love, many still refer to it as “Canadian bacon.” They call it that in Canada, the place on both sides of Quebec—joking, joking.… Part of the history of Montreal is an overdramatized opposition to Toronto. Maybe it’s hockey, maybe it’s the separatist thing, or maybe it’s just a friendly rivalry. Regardless, we love Toronto. It’s where our favorite butcher, Stephen Alexander, has his shops (Cumbrae’s), and it’s the national capital of oyster bars (Rodney’s, Oyster Boy, Starfish). It’s also home to Kids in the Hall, John Candy, the Black Hoof, and, of course, the Saint Lawrence Market, where you can get a peameal bacon bun with maple mustard.

Peameal is not made with peas anymore. Like most aspects of life, ranging from food to plastic, peameal is being taken over by corn. We make our peameal with dried yellow peas crushed in the processor. The purpose of peas or cornmeal is to wick and dry, thus preventing spoilage. You will let the meat brine for a minimum of four full days, ninety-six hours, in the fridge. It is necessary to have a brine injector; they sell them nowadays for under ten bucks in big stores.

3 quarts (3 liters) cold water

1 cup (300 g) maple syrup

⅔ cup (150 g) kosher salt

2 tablespoons Prague powder #1 cure (optional)

10 peppercorns

1 tablespoon mustard seeds

1 bay leaf

4½ pounds (2 kg) boneless lean pork loin

1½ cups (215 g) coarse cornmeal or 1½ cups (340 g) dried yellow peas, roughly milled in a food processor

1. In a plastic (preferably) container large enough to hold both the brine and the meat, mix together the water, maple syrup, salt, cure, and spices.

2. Scoop out a scant 1 cup (200 ml) brine, and use it to load the brine injector. Then, inject the loin every ¾ to 1 inch (2 to 2.5 cm), inserting the needle about ¾ inch (2 cm) deep. Try to distribute the brine evenly over the loin. Place the loin in the container with the remaining brine, and keep the meat submerged with the help of a plate or an object of a similar build. Cover and refrigerate for 4 full days.

3. Remove the loin from the brine and pat it dry. Then roll it in the meal of your choosing. Give it a day’s rest, uncovered, in the fridge, so the meal and meat form as one.

4. You have two options on cooking it: you can slice it and griddle it for a minute on each side (for thin slices that is), or you can bake it at 375°F (190°C) for about an hour, or until it has a core temperature of 142°F (61°C), then slice it. I like it the first way, especially when it gets a bit burnt on the edges and I have added a dash of maple syrup that caramelizes a bit toward the end.

Serves 4

This recipe is an homage. While aboard the Ocean, en route to Prince Edward Island, we had three choices for dinner: haddock Dugléré, chicken jalfrezi, or fish chowder and sandwich. Meredith went for the chicken, everyone else had haddock. Fred looked at Meredith’s, knew it was better, and talked the entire trip about ordering it on our return. As we made our way back to Quebec, all he wanted was a warm and true jalfrezi.

So we’re back on the train, in our favorite booth, two bottles of wine down when the attendant comes to our table. Fred orders. “Sorry, sir, all we have left are ham sandwiches and Pringles.” Devastation in the form of a one-hour rant about the decline of the railroad ensues.

The jalfrezi had such an impact that we wanted to get it into this chapter. So we asked ex–Joe Beefer and curry pro Kaunteya Nundy to come up with a classic jalfrezi. Not surprisingly, he came up with a recipe that put the VIA Rail version to shame. This is for Fred. And this is what Kaunteya had to say about the dish: “I asked my family what jalfrezi means, and I was told by my Bengali grandmother [Calcutta region] that jal means ‘hot’ and frezi means ‘fry.’ This is a very Anglo-Indian dish that was invented by the British. My mom, Shobhna Nundy, and I created this recipe. We made it three times to make sure that it was just right and would not blow away the ‘white folks’ from a spicy [heat] level.”

SPICE MIX

2 teaspoons coriander seeds

2 teaspoons cumin seeds

½ cinnamon stick

2 bay leaves

2 dried red chiles

Seeds from 4 green cardamom pods

6 whole cloves

½ teaspoon fennel seeds

½ teaspoon ground turmeric

JALFREZI

5 tablespoons (75 ml) vegetable oil

2 pounds (900 g) boneless, skinless chicken thighs, halved

Salt and pepper

3 onions, finely chopped

4 cloves garlic, finely minced

½-inch (12-mm) piece fresh ginger, peeled and finely minced or grated

2 green chiles, finely chopped

4 to 5 tablespoons (60 to 75 ml) red wine vinegar

6 canned plum tomatoes, lightly pressed with a fork

2 tablespoons ketchup

1 large green bell pepper, seeded and cut into 1-inch (2.5-cm) squares

1 large red bell pepper, diced into 1-inch (2.5-cm) squares

1 teaspoon ghee (clarified butter)

2 tablespoons plain yogurt

Coarsely chopped fresh coriander for garnish

BASMATI RICE

2 cups (400 g) basmati rice

4 cups (1 liter) water

2 bay leaves

2 whole cloves

2 green cardamom pods

Pinch of saffron threads

Pinch of salt

3 to 4 teaspoons butter, melted

Lightly toasted slivered almonds for garnish

Note: There are two ways to make Basmati rice. The quick and dirty way, aka boil and drain, or the traditional way. This is the traditional way.

1. To prepare the spice mix, in a small sauté pan, combine the coriander, cumin, cinnamon, bay leaves, dried chiles, and cardamom and roast over medium heat for about 4 minutes, or until a very fragrant cumin aroma is released. Let cool. Transfer to a spice grinder, add the cloves and fennel seeds, and grind to a fine powder. Pour into a small bowl, add the turmeric and mix well. Set aside.

2. To make the jalfrezi, preheat a large, thick-bottomed stew pot over high heat and add the vegetable oil. At the same time, season the chicken thighs with salt and pepper. When the oil just begins to smoke, using tongs, place the thigh pieces into the pot and sear until golden brown on all sides. This should take 4 to 6 minutes. Remove the thighs with a slotted spoon to a large plate and set aside.

3. Add the onions, garlic, ginger, and green chiles to the pot and sauté, scraping the bottom of the pot as you stir. After about 7 minutes, reduce the heat to medium and season with salt and pepper. This will cause the onions to release some of their liquid, which will make it easier to dislodge the browned chicken bits from the bottom of the pot as you stir. When the onions are lightly caramelized, deglaze the pot with the vinegar and continue to scrape the bottom of the pot.

4. Return the chicken to the pot along with any juices that accumulated on the plate while it rested. Add the spice mix and stir together all the ingredients so the spices adhere to the chicken pieces. Now add the tomatoes, ketchup, and the bell peppers and mix well. Add just enough water to cover the top of the chicken, raise the heat to high, and stir constantly. When the mixture is about to boil, cover the pot, reduce the heat to medium-low, and simmer for 15 to 20 minutes, or until the chicken is cooked through.

5. Uncover and raise the heat to medium-high to evaporate the excess water and to thicken. When the dish starts to thicken slightly and a light sheen of oil is visible on the surface, add the ghee. Move the chicken pieces to the sides of the pot, creating a well in the center. Mix the yogurt into the liquid in the well, then remove from the heat. The ghee and yogurt will enrich the sauce.

6. While the jalfrezi is cooking, prepare the rice. Preheat the oven to 375°F (190°C). Rinse the rice until most of the starch is removed. We like to do this by rubbing the grains between our palms under cool running water. Drain the rice well, then place it in a heavy ovenproof pot with a tight-fitting lid. Add the water, bay leaves, cloves, cardamom pods, saffron, and salt.

7. Place the pot on the stove top over high heat and bring to a boil, stirring occasionally. When the rice is boiling, cover the pot tightly with aluminum foil and then the lid and place in the oven for 20 minutes. Remove the rice from the oven and let it sit, still covered, for another 10 minutes.

8. To serve, transfer the jalfrezi to a warmed serving dish and garnish with the fresh coriander. Remove the lid and foil from the rice pot. The rice should be “standing,” very aromatic, and slightly orange from the saffron. Fluff the rice with a fork and drizzle the melted butter on top for an even richer, nuttier flavor. Garnish with the slivered almonds for a traditional finish. Serve the jalfrezi with the rice.

Serves 4

This recipe is from a trip that Fred took with Allison and her parents to the Czech Republic: “I was thirty, traveling in the back of an Opel minivan loaded with adults. The bottles of beer were always too small and the stops never frequent enough. This was back when I was ignoring a little gluten issue and drinking vast quantities of Czechvar/Budvar. Basically, this trip was like the Griswolds in Prague.

“While visiting an old brewery’s beer garden, I noticed a ‘little things to eat with beer’ section of the menu. It was full of pickled herring, utopenec (pickled sausage), and cheese. We ordered them all, and when the cheese arrived, it was like a gathering of all of the cheese leftovers blended with beer. It was unsightly and completely delicious.”

You will need four (4-ounce) cheese molds with holes or four Styrofoam coffee cups with holes poked in the bottoms and sides, plus four paper coffee filters to make the cheese.

4½ ounces (130 g) quark cheese

4½ ounces (130 g) cream cheese

3½ ounces (100 g) blue cheese

½ cup (125 ml) pilsner beer

1 teaspoon salt

½ clove garlic, finely minced

Hefty pinch of paprika

ACCOMPANIMENTS

Rye bread slices panfried in butter and rubbed with a garlic clove

Pickled cherry or banana peppers

1. Leave the cheeses at room temperature for about 1 hour.

2. In a small pot, warm the beer over medium heat and then remove from the heat.

3. In a food processor, combine the cheeses, beer, salt, garlic, and paprika and process until smooth and homogenous, stopping to scrape down the sides of the bowl as needed.

4. If you are using Styrofoam cups (see note above), use a hot nail or small pointed knife blade to poke holes in each cup, spacing them every square inch (2.5 cm). You should have about 30 holes. Dampen the coffee filters, and line each perforated Styrofoam cup or drainage cup with a filter.

5. Divide the cheese mixture into 4 equal portions, and put a portion in each lined cup. Put the cups on a rimmed plate, cover with plastic wrap, and refrigerate overnight.

6. Unmold the cheeses and place each portion on a plate. Serve with the rye bread, pickled peppers, and crudités.

Serves 4

This great side dish has a bit of a Quebecois-lumberjack-in-Bollywood taste. It is red lentils cooked like dahl, seasoned like baked beans. It is a pork chop’s best friend, or will mate with a hefty breakfast.

4 slices bacon, finely diced

1 onion, finely chopped

½ teaspoon minced garlic

2 cups (400 g) red lentils, picked over and rinsed

4 cups (1 liter) water

¼ cup (60 ml) ketchup

2 tablespoons maple syrup, plus more as needed

2 tablespoons neutral oil

1 tablespoon cider vinegar, plus more as needed

2 tablespoons Colman’s dry mustard

1 teaspoon pepper, plus more as needed

1 bay leaf

Salt

1. Preheat the oven to 350°F (180°C). In an ovenproof pot with a lid, fry the bacon over medium-high heat until crisp. Add the onion and cook, stirring, for about 4 minutes, or until softened. Then add the garlic and cook for 1 minute longer.

2. Add the lentils, water, ketchup, maple syrup, oil, vinegar, mustard, pepper, and bay leaf. Stir well and season with salt. Bring to a boil. Cover, place in the oven, and bake for 45 minutes, or until the lentils are tender.

3. Taste and correct the seasoning with salt, pepper, maple syrup, and vinegar. Serve hot now or later.

Serves 4 to 6

It’s tough to find real chowder in this city, so we promised we would always have delicious homemade chowder by the cup or bowl at McKiernan. Ours is made with fresh Carr’s PEI clams.

½ cup (115 g) unsalted butter

6 celery stalks, chopped

3 large onions, chopped

9 ounces (250 g) bacon, cut into ¼-inch squares

2 large spuds, preferably Yukon Gold, peeled and diced

Fistful of all-purpose flour

4 cups (1 liter) 2-percent milk

Salt and pepper

15 large cherrystone clams, preferably from PEI; 20 little-necks; or 4 pounds (1.8 kg) savoury (aka varnish) or manila clams, well scrubbed and free of sand

One 12-ounce (375-ml) can beer

Pringles, fresh chives, and chopped celery heart (if not too bitter) for garnish

1. In a large stockpot, melt the butter over medium heat. Add the celery, onions, and bacon and cook for 6 to 7 minutes, or until the onion is translucent and the bacon is cooked and glossy but not yet crisp.

2. Add the spuds and flour to the pot and stir steadily until all of the bacon fat and butter drink up the flour. (A flat spatula and flat-bottomed pot make a difference to the job, since once the flour is in the pot, it sticks in about 4 minutes if you’re not paying attention.) Add the milk and drop the heat to low. Season with salt and pepper and leave the chowder to cook, uncovered.

3. Meanwhile, in another large stockpot, combine the clams and the beer over high heat. Use only half of the beer; drink the rest. Too much beer will make the chowder curdle. Cover and cook for about 5 minutes, or until the clams open. Remove from the heat, uncover, and pick out and discard any clams that failed to open. When cool enough to handle, remove the clams from their shells, capturing any juice in the pan. Discard the shells and set the meats aside. Strain the juice through the finest-mesh sieve available and set aside.

4. Slice the clam meats. Check to see if the potatoes are cooked, and if they are, add the clam meats and strained juice.

5. The chowder is ready to eat, but it is better when it is one day old. Cover and refrigerate and reheat the next day, adding more milk if it is too thick. Serve with Pringles on the side and topped with chives and celery heart. Repeat recipe twice a week for 2 years.