In light of industrial musicians’ purported concern with the politics of control, one might expect them to engage with the topic of race. This happens only rarely in a direct sense, though. A close look at this music over time nonetheless helps us not just understand its racial attitudes but also explain why these attitudes matter, and how they relate to the music’s past and future.

By the numbers, the overwhelming majority of industrial musicians and fans are caucasian. The low level of minority participation in the music might have something to do with the already rich body of protest music in Latin America and the African diaspora; one could argue that there’s an abundance of protest musics more welcoming of diversity. But beyond that, there’s a more insightful set of reasons for industrial music’s predominant whiteness (and perhaps its maleness). This book notes early on that a lot of industrial music embodies the enraged response to “waking up” from a supposed hegemonic enslavement. For example, Paul Lemos of the band Controlled Bleeding wrote in 1985 that his output “reflects the frustration that comes in realizing one’s own inability to affect a political system, and one’s own insignificance in the scope of the masses.”1 But waking up to a cataclysmic personal shock like this is only possible to those lulled into slumber to begin with—a condition predicated on certain privileges, such as the promise of adequate earning power, correct fluency in the dominant language, and an inheritance of social autonomy, trust, and belonging.

To many people who aren’t socially granted these privileges of identity, it’s self-evident that the system is rigged. Although the cultural conversations of racial disenfranchisement might not be overly concerned with exterminating all rational thought, it’s yesterday’s news that western culture’s particular brand of rationality sometimes offers limited benefit to outcasts. Industrial music’s privilege, along with its post-1990 surge of lyrics about romantic relationships gone bad (more about this in the coming chapters), largely accounts for the occasional journalistic criticism of the genre as being whiny.

Industrial music’s mission of exposing western control systems has the greatest potential significance to those for whom such controls and their categorizations are least visible. Put plainly within the specific context of race, this means that industrial music presumes a white audience. This doesn’t mean that the music is racist; nor does it preclude deeper, more nuanced articulations of racial politics within the genre. It does suggest, though, that a genre concerned with recognizing and combating social hegemonies could potentially learn and gain strength from an ongoing dialogue with other racial expression and critique.

This chapter looks closely at how industrial music inadvertently operates within, and reinforces its presumption of, identity. It also acknowledges and analyzes the genre’s engagement with racial otherness, highlighting both some actualized moments and some missed opportunities in the dialogue just mentioned.

Before delving into how industrial music assumes and responds to whiteness, let’s begin by locating some of its nonwhite origins. Recalling Chapter 3’s differentiation between industrial and classical values in music, we should reiterate that industrial is a form of western popular music, and that broadly some of the most ubiquitous features of modern popular styles derive expressly from African American music. A kick-snare backbeat and a pervasive syncopation in vocal rhythm are just two practices that have become so normalized across rock and dance music that, taken on their own now, they convey only faint traces of any markedly African music. With a few exceptions like the power electronics subgenre, most industrial music has spoken with—or at least spoken about—this pop language since 1980 or so. In the overwhelming majority of industrial music and pop styles, rhythms are looped with consistent tempo and beat emphasis, harmonic progressions repeat cyclically (often in patterns of two or four chords at a time), key changes are rare, and melodies recur unchanging. The modern use of these musical building blocks is remarkably consistent on records by Al Green and à;GRUMH… alike, and it all stems unambiguously from the collision of African musical practices with the historical Euro-American soundscape.

Beyond industrial music’s prerequisite (and occasionally resented) pop heritage, it intersects in a few more meaningful and specific ways with African American music. For example, Chapter 9 noted the pleasure that Nitzer Ebb took in the blues; Douglas McCarthy’s voice constantly slides between a song’s tonic and its minor third, a hallmark gesture of the style. As more influences from rock filtered into industrial music in the 1990s, borrowings like that spread; Sister Machine Gun’s “Cut Down” is a prime example, with a flatted fifth in its melody, a jivey offbeat emphasis in its drums, and a brass-filled, zero-irony chorus about “the middle of the big ol’ night.”

From a chronological view, though, the first important junction we should acknowledge between industrial music and racial otherness is in the genre’s early connection to experimental jazz. The pop and blues idioms just outlined are so ingrained in modern western music as to be plausibly transparent, but industrial music’s invocation of jazz comes from a self-aware position of musical understanding. In most cases, it’s a nod of kinship to a shared revolutionary moment when musical worlds were bridged by commonalities of improvisation, (Afro-)Futurism, and organizational independence.

The heavily improvisatory nature of early industrial music, combined with its literate self-inscription within a twentieth-century political tradition, compels connections to the Englishman Cornelius Cardew. Cardew was a former protégé of Stockhausen who, with a Maoist focus on equality, formed the radically improvisatory Scratch Orchestra in 1969. Like Genesis P-Orridge, Cardew was involved with the Fluxus art movement in the 1970s and saw the bounds of musical composition as extending well beyond traditional performance: in addition to his fascination with the recording studio as an instrument, he studied graphic design to allow his nebulous, abstract musical scores to stand as art themselves.2

Outside this European intelligentsia, however, the fundamental improvisatory force in music was the free jazz that Ornette Coleman and others had been playing since the early 1960s. Free jazz (a loaded term that, like nearly any good subgenre name, was largely disavowed by its practitioners) is wilder and less populist than Cardew’s music, and it thrives on the tension between players’ responsive musical dialogue and the loud tantrum of their individual, isolated monologues, warring for the listener’s ear.

Both of these approaches to improvisation hung fresh in the air when early industrial acts like Clock DVA got their start. Their debut White Souls in Black Suits offers a panorama of thin, reverberant soundscapes devoid of steady rhythm and littered with saxophone whines; bearded band member Charlie Collins was a self-described Ornette Coleman fan.3 Remember also the choking, frantic saxophone that pervaded early performances of Deutsch-Amerikanische Freundschaft (the 1979 live version of “Gib’s Mir” on Die Kleinen und die Bosen is particularly ferocious); it becomes clear that the innovations of jazz music in particular were important to industrial musicians, especially because so many of them had been weaned on the jazz inflections of the prog-rock scenes of the 1970s—even Kraftwerk’s first records were full of flute solos.

This jazz crossover is evident in the media surrounding early industrial music as well. The November 1984 issue of Artitude magazine boasts in-depth artist profiles of both Coleman’s guitarist James “Blood” Ulmer and NON’s Boyd Rice, unblinking in its juxtaposition. In 1987, the Jazz Composers’ Orchestra Association took out full-page ads for their New Music Distribution Service in San Francisco’s industrial zine Unsound, hawking records by Coleman, goth-blues shrieker Diamanda Galás, turntablist Christian Marclay, and John Zorn, a jazz wild man from New York’s No Wave scene.4

It was in this downtown sensibility that the connections between industrial and jazz are most clearly forged, and their mutual encounter is still visible today in crossover magazines such as The Wire. Although Zorn, for all his clattering abjection, never had much to do with the industrial scene, he and his New York contemporaries (notably Glenn Branca, Lydia Lunch, Elliott Sharp, and bands like Bill Laswell’s Material and Sonic Youth) were similarly concerned with moving beyond punk’s rockabilly trappings and exploring noise. No Wave scene historian Marc Masters writes, “No Wave’s deconstructive approach drew on other ancestors from the 1960s and ’70s: the radical noise of free jazz musicians like Albert Ayler and Sun Ra, the experimental blues-rock of Captain Beefheart and the Magic Band, the trance-inducing rituals of German groups like Can and Faust.”5 The majority of industrial music however, had generally seemed to jazz-descended hipsters in the 1980s a bit too white both in its inability to achieve a relaxed coolness and in its real (if rare) pockets of racial extremism. Recalling the geography of industrial music’s earliest years, we might even posit that at the turn of the 1980s the genre’s relative silence in New York (and for that matter, Chicago, Bristol, and Paris) had a lot to with the degree to which African-descended populations contributed to the urban dialogue of cultural innovation.* Despite this, a few important No Wave–related acts managed to appeal both to the ever-trendy offspring of the New York scene and to the industrial milieu. Prominent among these are Michael Gira’s occasionally gothic band Swans (later joined by tape scene chanteuse Jarboe); some projects by Jim G. Thirlwell (of Foetus), whose York (First Exit to Brooklyn) album, for example, employed No Wave’s session players and its spirit; and Jon Spencer’s pre-hardcore band Pussy Galore, arguably most known for their raucous 1988 version of Einstürzende Neubauten’s “Yü Gung.”

The rare direct borrowings from jazz in later industrial music reach back to a cultural moment when cacophony bleated a pruriently appealing threat to the western status quo. (This jibes particularly well with industrial’s debt to Burroughs and beat poetry.) Such nods include Trent Reznor’s modal saxophone improvisation in “Driver Down” from the soundtrack to Lost Highway, whose auteur David Lynch stands at the crux of industrial extremism and 1960s cool cat Americana. Or take Nettwerk Records signee MC 900 Ft Jesus, whose career’s odd shape owed heavily to the fact that neither he nor his record label could seem to figure out whether he was an industrial musician, a rapper, a comedian, or a jazz man; he delved deep into Coleman territory on his third album, 1994’s One Step Ahead of the Spider, on which he traded out Steven Gilmore’s cyber-cool graphic design for a whiteness-obscuring, neobiblical portrait by graffiti artist Greg Contestabile. Or consider 2004’s “Sex With Sun Ra (Part One—Saturnalia)” by old school industrialists Coil; Sun Ra was among the most daring and opulent performers in free jazz, and in this marimba-driven song John Balance narrates an imagined religious experience with the man (who had in fact been dead since 1993). Within later dance industrial music, Haujobb’s 1996 “The Cage Complex” concludes with a thrillingly earnest saxophone solo, full of altissimo squeals and multiphonic squonks directly from the bebop language of the 1960s, and Mona Lisa Overdrive’s 1993 “It’s Time” opens with a faux Miles Davis moment of trumpet cool. The message in all these songs’ close brushes with jazz is at the very least a recognition of its musical power, both in the notes themselves and in its stylistic connotations—a consideration inextricable from race. To most musicians (and likely many audiences), these borrowings function as musical admiration or homage.

Production effects and recording techniques are other touchstones that have connected industrial music across racial lines in ways that don’t immediately strike one as problematic. Dub music—a 1970s reggae-derived experimentation with beats, textures, and effects—has especially close ties to industrial, both historically through a handful of individuals who straddled both scenes and conceptually through the idea of Afrofuturism, which is the practice of reclaiming and controlling the dialogue of one’s racial otherness by becoming “out of this world” through technology and sheer strangeness. By recasting disenfranchisement as literally alien, Afrofuturists tap into science fiction’s treatment of the alien as awe-inspiring and plainly superior. Musicians such as Sun Ra, Afrika Bambaataa, Janelle Monae, and Kanye West have all invoked Afrofuturism, and production practices like sampling and remixing (first practiced live by African American DJs) are inextricably associated with it. Scholar and electronic music producer Steve Goodman asserts that it’s a driving force behind jungle, dubstep, and nearly every major innovation in recent dance music, and its compatibility with industrial music’s technophilia (if not its techno-paranoia) is self-evident.

The closest continued acknowledgment between Afrofuturism and industrial music occurred in the mid-1980s with the racially mixed Bristol UK–based dub reggae scene that Adrian Sherwood and Mark Stewart helped to kickstart. Assisted intermittently by New York–based compatriots Doug Wimbish and Keith LeBlanc—both backing musicians for first-generation rap acts such as the Sugar Hill Gang—Sherwood and the On-U Sound collective applied dub production techniques to records by Nine Inch Nails, Ministry, and KMFDM. The Bristol scene, which also included Tricky and the future members of Massive Attack, effortlessly applied what they called “dub logic” to reggae and harsh dance music alike.

Dub involves the spacialization and blurring of musical events through looping, equalization, and reverberation; in the hands of Sherwood, dub owed nearly as much to Brian Eno as it did to Jamaican production and DJing. In the 1980s, Sherwood and his buddies produced and played on literally hundreds of albums—mostly for Jamaican artists—while maintaining a relationship with industrial music. For example, as Keith LeBlanc cut tracks for World’s Famous Supreme Team’s 1986 album Rappin’, he was at the same time assembling his own underground hit single “Major Malfunction,” sampling the Challenger shuttle explosion and looping Ronald Reagan’s intonation that space was “pulling us into the future.” Similarly, Mark Stewart’s band at the time, the Maffia, felt at home crafting straight-up reggae tracks such as “None Dare Call It A Conspiracy” alongside the classic industrial assaults “Hypnotised” and “The Wrong Name and the Wrong Number”—tracks beloved by cEvin Key of Skinny Puppy.6 For these musicians, the path between Black Uhuru and Big Black was clear and open: “I don’t see race,” Stewart says flatly.7 Jamaican reggae and dub are the sound of a culture transplanted from Africa across the ocean and forced to adapt; the sound that Sherwood, Lee “Scratch” Perry, and Mark Stewart crafted is that of a culture now twice transplanted, echoing the cold of England and its postindustrial techno-ambivalence into the old song. Displacement itself is the subject here, and it follows the trade routes of slave ships.

It should be noted that Sherwood is white, which in the 1980s led to a few members of the Rastafarian sect Twelve Tribes accusing him of appropriating a sound that was “rightfully theirs.” However, to most of the musicians he worked with, his commitment to and respect for reggae was in no conflict at all with his race and his industrialist tendencies. In Sherwood, industrial music and Afrofuturism mutually absorb one another; On-U Sound’s releases used to be stamped with a copyright date of ten years into the future, boldly reclaiming the music’s displacement with sci-fi panache.

But On-U Sound is an anomaly, and after the 1980s Sherwood only occasionally popped his head into the industrial scene. Even then, it was just to remix a twelve-inch version for old friends like Skinny Puppy and Nine Inch Nails. In the dub-meets-industrial world, there are remarkably few descendants of this bloodline: Godflesh and Scorn both mixed noise, reggae, and metal together, Legendary Pink Dots bassist Ryan Moore founded Twilight Circus Dub Sound System, and the French act Treponem Pal broke modest ground with some rootsy industrial rock records in the 1990s, but these endeavors had limited impact on industrial music as a whole.

Although the previous examples suggest a symbiosis between industrial music and African-derived traditions, the relationship is usually more parasitic. Beyond the aforementioned blues, jazz, and dub inflections, industrial music’s connection to race is less a dialogue than a monologue: as mentioned at this chapter’s outset, industrial music tends to presuppose whiteness—that is, hegemonic non-otherness—on the part of audience and musician alike. This manifests in its use of racial caricature and its engagement with certain technologies as racially incidental rather than intentional. In what follows, the point again is not to brand any music or individuals as racist, but to look at how industrial music seldom acknowledges racial otherness.

Part of industrial music’s vocabulary is its “Third World tribal rhythm mentality [that] was thrown in to add a sense of disembodied cultural yearning,” according to tape scene historian Scott Marshall.8 Some industrial musicians feel a genuine empathy with the ritual and trance elements of specific foreign musics, but this is in nearly every instance an outsider’s projection, not a case of “going native.” Marshall refers mostly here to the influential lineage of 1950s exotica, which manifests musically in certain recordings by Throbbing Gristle (the song “Exotica,” unsurprisingly) and NON. It lurks behind the band names of Pygmy Children and Voodoo Death Beat, and with varying degrees of irony it’s also an undercurrent in the music of 23 Skidoo, Hula, and other postpunk acts. Masked as world beat, this exotica was the entire foundation of the Italian pseudo-Inca band Atahualpa, whose “Ultimo Imperio” was a hit on industrial dancefloors in 1990.

Musicologist Phil Ford connects exotica to Futurism in its ability to relate simultaneously to modernity and also to an imagined world that offers an alternative to the military-industrial control of culture, “Seeking a residue of the primitive in a present cluttered with our machines.”9 In this way, it occupies a role similar to the “fallen Europe” trope that martial industrial music has centralized, or more recently, the playful vintage aesthetic that the industrial-turned-steampunk act Abney Park invokes. Exotica, Ford says, “is a kind of pictorial music, broadly representational though not necessarily narrative,” and thus (again, not unlike steampunk) inasmuch as exotic sensibilities feed into industrial music, its no surprise that they’re most evident in the visual component of the genre.10 Recall, for example, Monte Cazazza’s forays into Mondo-derived filmmaking, or consider the record sleeves seen here.

Figure 14.1: The cover sleeve of Hunting Lodge’s 1985 “Tribal Warning Shot” single uses a photograph of African tribespeople from a 1935 textbook. The rear sleeve quotes the book, “The little people are very good to us when they learn that we do not mean to harm them. They listen with great curiosity to our small radio, which seems like magic to them.”

Figure 14.2: The Fair Sex’s 1987 “Bushman” single exoticizes the southern African people by name while its cover obscures the German quintet in a gauzy jungle of otherness.

Figure 14.3: Bizarr Sex Trio’s 1990 self-titled record closely resembles (and overtly sexualizes) the Congolese Pende tribe’s Gitenga mask art. Art by Paul B. Hirsch.

Figure 14.4: The Neon Judgement’s 1986 Mafu Cage, inspired by the 1977 film of the same name. Frontman Dirk Da Davo says, “We wanted to do an album that fit a voodoo kind of feeling. We wanted to use monkey sounds, earthy sounds.”

It’s apparent that there’s a dimension of cultural and racial border crossing at work here. Ford explains, “The exotica imagination is orientalist … whether or not the places it envisions are literally oriental, or even belong in the real world.”13 Westerners’ use of these racialized images then isn’t specific but is instead based on the otherness of the supposed cultures it portrays; it illustrates a sexual, safarilike, dangerous fun that’s presumably absent from the white postindustrial world. Here this manifests beyond the African diaspora and includes the near eastern flavor one hears in SPK’s Zamia Lehmanni album, Laibach’s version of “God Is God” (originally by Juno Reactor), and A Split-Second’s 1988 “Mambo Witch,” a catchy single that freely conflates “the Hindu curse”—whatever that is—with Cuban mambo.

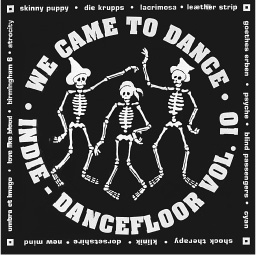

Figure 14.5: The visual theme of We Came to Dance (12 vols., 1993–1999) derives from the Mexican Día de los Muertos celebration. Art by Margit Tabert, Charly Rinne, and Nadine Van Den Brock.

Figure 14.6: The back sleeve image of Dance or Die’s 1991 3001 is of a Javanese puppet.

Ford characterizes exotica as “a libidinous fantasy stocked with conventionalized others. The human objects of orientalist perception are unreasoning, instinctual, indolent, childish, cruel, sexual—the old colonial hand’s half-wishful inversion of his own self-understanding.”14 And so for industrial music, this wishfulness takes the form of the Burroughs-esque wild boy persona to whom abjection comes laced in gross whimsy, more clownish than miserable. Good examples of this are 1992’s “Do the Monkey (Hitchhike to Mars)” by Swedish act Peace, Love & Pitbulls and 1995’s “Hey Fuck Da’ World” by Klute, a side project of the Danish EBM powerhouse Leæther Strip.

Figure 14.7: Neither the name of the American coldwave band Clay People nor their 1995 EP title Iron Icon quite clarifies the use of a Japanese porcelain figurine on the record’s cover. The image was selected for use by the band’s record label owner.

The critical considerations of exotica lie well beyond its aesthetic intent. Ford concludes, “When intellectuals handle this music with the hermeneutic equivalent of tongs and a HAZMAT suit they are in a sense not hearing it at all. The moment we insist on the interpretive priority of colonialism and commodification, fun time’s over.”15 Certainly this chapter is guilty as Ford charges, but nevertheless, in order for exotica’s fun to work at all, one needs to assume a collective self-identity against which to frame the otherness portrayed. From its Tiki theater, exotica gives free rein to the white imagination—but perhaps only the white imagination—to roam outside the western responsibilities of culture and privilege.

Another possibly contentious way that industrial music interfaces with race is in its use of gestures from traditional African-derived musics as a source of irony, reading them as kitsch. A clear case of this is KMFDM’s 1995 “Juke Joint Jezebel,” whose chorus features a massive gospel choir erupting out of nowhere, rhyming “sister salvation” ridiculously with “my cremation.” In addition to the backup singers, the chorus’s harmonic use of the flatted seventh within a major key (the Mixolydian mode, as it’s called) immediately sets the song apart from industrial conventions. It’s a send-up, to be sure, but of what? At once sleazy and exuberant, the chorus takes pleasure in self-destruction (as the lyrics describe), tapping into shallow perceptions of religious fervor and lasciviousness. Is the musically encoded sense of African American stereotypes the point, then, or is KMFDM using it as a genuinely expressive meeting ground for the old industrial warhorse topics of Christianity, sex, and hypocrisy? Both interpretations are problematic. And there are other examples too. Nearly the exact same reading is available to 1985’s “The Only Good Christian Is A Dead Christian” by Scraping Foetus Off the Wheel, a foot-stomping jive song that in gospel harmony declares, “I’m payin’ for the price of sin,” while simultaneously, “The time is ripe for satisfaction.” Or for that matter, Revolting Cocks’ “Beers, Steers, and Queers” is plainly a rap song about (among other things) “sex in barns,” proclaiming, “Texas has religion: Revolting Cocks are God!” Are industrial musicians taking pleasure in African American tropes while simultaneously turning their nose up at those for whom such music is a genuine expression, or are they shooting holes in minstrelsy by parading it as absurd? If the latter is the case—a charitable reading—then the tactics of reversal here share the same pitfalls as industrial’s treatment of fascism, as discussed in the preceding chapter.

In this industrial tackiness (which seems to have all but died out since the mid-1990s), racial borrowings are a source of humor. Even if this humor might not expressly come at the expense of African American culture or its music, it’s worth asking whether the joke would work in the same way if the musicians were not white. Describing a similar kind of borrowing in language, anthropologist Jane H. Hill talks about what she calls “mock Spanish,” as when Arnold Schwarzenegger’s badass cyborg character learns to say “no problemo” and “hasta la vista, baby” in Terminator 2. But, as Hill argues, “It is only possible to ‘get’ ‘Hasta la vista, baby’ if one has access to a representation of Spanish speakers as treacherous,” and by extension, “getting” the caricature thus reinforces it.16 So although there is real musical pleasure and power in these industrial borrowings, and despite their arguable status as “crossover” gestures (“curiously indeterminate” in their politics, Hill says), they nevertheless occupy an uneasy position, their value relying to a degree on the genre’s baseline assumption of whiteness.*

Not all connections between industrial music and race are borrowings. Technology provides musical similarities across genres that can be both historically incidental and ideologically loaded. Prior to the advent of the sampler as an instrument, musicians who wanted to make electronic pop of any kind had a decidedly finite choice of sounds, due to the limited number of synthesizers and drum machines for sale. Thus the drum and bass sounds we hear in the mid-1980s work of Chris & Cosey come in some cases from the same presets on the same gear that was used on disco records from the era. For example, musicologist Robert Fink has traced the use and history of the “ORCH5” preset on the Fairlight CMI workstation, replete with appearances in the music of Kate Bush and Afrika Bambaataa alike.17 As hinted at in Chapter 8, it makes for a sonic sameness across styles that might optimistically be read as kinship: it’s part of why clubs like Antwerp’s Ancienne Belgique and Chicago’s Muzic Box could play breakdance records alongside Cabaret Voltaire. It’s also why on Front 242’s first U.S. tour they attracted massive audiences of African Americans who heard a connection between early EBM and the electro to which they regularly danced; a quick listen to 1983’s Enter album by Juan Atkins’s band Cybotron drives home the point nicely. Through the first half of the 1980s, neither these electronic sounds nor the gear nor the production practices were particularly racially coded.

But the way people enjoyed this music could indeed be racially coded. As this book’s discussions of beat-driven industrial and EBM have suggested, much of the musical pleasure in repetition is rooted in bodily pleasure, most directly connected to dancing, but also mapped as an analogue for sexual expression. Pop scholars have pretty conclusively demonstrated that a lot of the repetition and bodily-ness that we hear in popular music today takes funk and disco as its basis, and that because those musics share a common cultural and racial origin, there’s an associative cultural element in dancing to the harmonically static and the rhythmically relentless. This is certainly the case in America, Africa, and Western Europe by virtue of their long, often ugly history in which music, culture, money, and slaves repeatedly crossed the Atlantic.

Beyond the shared sounds across electronic musics in the 1980s (racially imprinted or not), we can talk about repetition in popular music as a potential function of technology. Recall, for instance, the loop-based songs of Deutsch-Amerikanische Freundschaft discussed in Chapter 5. The technological repetition of a groove, digitally precise in its sameness, resonates naturally both with this somewhat racialized bodily pleasure and with industrial music’s ironic fetishization of technology and uniformity. This is another reason why the musical phrase lengths in à;GRUMH…’s “Ayatollah Jackson,” addressed in Chapter 2, are of seemingly arbitrary duration: in the recording studio, a singer who belts lyrics over a looping beat doesn’t have to memorize a predetermined timing but instead can start and stop as the mood strikes. The coldness of technology and the human “feel” of music’s structure find a common ground here. As Skinny Puppy’s cEvin Key says, it “wasn’t intentional to throw in time changes as much as it was a hunch, like what sounded right at the time.”18 Again, this hearkens back to the improvisatory nature of the music and its connections to jazz.

As the 1980s moved along, sampling became an affordable reality in record production, and this started to differentiate electronic styles that had previously shared sonic profiles. The records and sounds being digitally reproduced reflected musicians’ taste, culture, and physical surroundings. Samplers made first by AMS and later by Akai and Yamaha allowed multisecond snippets of sound to become building blocks of production, and musicians used them no longer just to capture a drum hit or a guitar pluck; now they were lifting entire one- and two-measure segments from records and looping them. Probably the most impressive work done with this technique occurred in hip-hop between 1988 and 1991, where Public Enemy’s producers the Bomb Squad aligned old funk loops in tempo and layered them with one another amidst horn jab samples, nonverbal funk grunts, and gospel choirs to create a veritable curriculum in African American music history. The Dust Brothers, who helped assemble the Beastie Boys’ Paul’s Boutique album in 1989, used their samplers with similar cultural savvy, highlighting the group’s white boy wackiness.

Loop-based sampling is especially well suited to hip-hop and industrial music because both styles tend to downplay traditional melodic and harmonic concerns, thus minimizing the degree to which a producer might worry about clashing tones in the sampled measures. Jon Savage recognized in 1983 the connection between hip-hop’s sound collage and the “anti-music” of the industrial movement: we “hear cut-ups played freely on the radio, in popular ‘scratch’ and ‘rap’ music.…”19 With the sonic retooling of the past being a tenet of industrial and hip-hop, it’s no surprise that they both reached the boiling point at the same time in the late 1980s, driven in part by the availability of sampling.

Simon Reynolds writes, “Sampling is enslavement: involuntary labour that’s been alienated from its original environment and put into service in a completely other context, creating profit and prestige for another.”20 In this distant way, sampling allows musicians to turn the tables on the slavery narrative, or alternatively to abreact it; the racial power in this act is clear, but industrial music’s themes of authoritarian control and sadomasochism resonate here duly, if with less historical force. And as exemplified by Meat Beat Manifesto, Consolidated, the Beatnigs, the Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy, MC 900 Foot Jesus, and other moments of crossover such as Ministry’s 1989 guest vocal rap “This Is A Test,” industrial music and rap found common ground in their anger and the practice of sampling. It wasn’t that Burroughs-reading anarchists were expressly concerned with racial struggle, or that the Bomb Squad had been necessarily listening to Test Dept., but rather the sampler was a vital, shared tool in the political expression of all contemporary urban cultures. Thus the modes of production between these musics overlapped as a result of political similarities, emphasizing certain common musical characteristics.

Legal battles and shifts in technology and trends toned down the sampling-as-politics practice in hip-hop and industrial music by the mid-1990s. This move away from reliance on the sampler was simultaneous with the mutual distancing of industrial and hip-hop, though technology may have played less of a role in this divide than suburbia’s remarkable repackaging of hip-hop as a marker of coolness and toughness for dominant white social groups; as an emerging soundtrack to high school jock culture, hip-hop became a flag of outcasts’ enemies. Nevertheless, postmillennial industrial rap groups such as SMP and Stromkern serve as a reminder, if only as a throwback, of this hinted-at kinship.

In terms of sonic artifacts on industrial recordings, the connection to African American musics via sampling also means that hip-hop sounds are all over records by the likes of Front Line Assembly: for example, 1992’s “The Blade” samples James Brown’s classic “Funky Drummer” beat, while 1997’s “Sado-Masochist” samples NWA’s Eazy-E. Nine Inch Nails similarly sample Prince’s “Tamborine” on 1990’s “Head Like A Hole (Opal mix).” This indicates both some cross-stylistic ideologies and tactics and also the simple fact that industrial musicians were listening across racial lines; for example, Paul Lemos of Controlled Bleeding boasts his fandom of Public Enemy and Ultramagnetic MCs in a 1989 interview.21 This crossing of lines was largely a one-way practice, though: industrial DJs in the UK, Germany, and America could spin rap records, but the days of the left-field crossover into hip-hop culture had effectively ended with the advent of its explicitly political self-awareness, around 1987.

One of the reasons for this unidirectionality was that despite a common attraction to the cut-up and a desire to subvert and confront, industrial music, on the rare occasions when it grapples with race directly as a topic, has a tendency to misunderstand or naïvely misuse elements of racial discourse.

German EBM act Funker Vogt offer a politicized racial context in their fascinating 2000 song “Black Market Dealers,” which seeks to capture the experience of German children following their nation’s defeat in 1945: “The first black men they ever saw were among the foreign soldiers. Some of them were really kind,” states the lyric. There’s a noncommittal strangeness to this passage that goes beyond Funker Vogt’s frequent infelicities with English. Rather, the careful mention of the soldiers’ kindness hints at a consciously civil response to racial otherness that may reflect the band’s modern politics as much as the experiences of the children they sing about.

Belgian project Holy Gang evidently felt the need to comment musically on the 1992 rape conviction of boxer Mike Tyson. The one-off group, which included Front 242’s Richard 23, titled their 1994 album Free! Tyson Free!, explaining to industrial zine Music from the Empty Quarter, “We felt if there was a rape, it was the rape of Mike Tyson more than anything else… he was black in America.”22 But any racially savvy critique that the trio offered of “New York City’s ghetto streets” badly misfired with the title track’s chorus chant of “Free Tyson! Fuck that bitch,” obliquely attacking submerged racism with direct and senseless misogyny.

This off-kilter treatment of race plays out elsewhere. Consider, for example, three industrial songs that sample the voice of Martin Luther King Jr.: Swedish act Covenant’s 1994 “Voices” replays a segment of his American Liberties Medallion acceptance speech, but incongruously it is a song about a man’s individual paranoia and regret; German electro-industrial band X Marks the Pedwalk transforms King’s cry of “Free at last!” from a dream of racial equality into a personal escape from “emotional lies” on their 1992 “Repression” (notably not “Oppression”); Australian act Snog’s “Born to Be Mild” of the same year critiques yuppie culture’s “Rick Astley look” and then confusingly throws in a sample of “I have a dream,” reframing either King himself or his dream—or in a less likely reading, perhaps commenting on yuppie suburbia’s coopting of King’s legacy. Regardless, in all of these songs artists play fast and loose with race. The industrial information war means cutting up the signs of the control machines, but in some of these cases artists are instead destabilizing other victims of that same control. Even when KMFDM aims for camaraderie across racial lines, enlisting Adrian Sherwood’s friend reggae singer Morgan Adjei to implore “Black man [and] white man” to “rip the system,” the message falls a little flat in its simplicity.

The industrial artists mentioned here hail from countries outside what cultural studies scholar Paul Gilroy calls the Black Atlantic. As such, the cross-racial interactions in their work are different from those of American, African, Caribbean, English, or French artists. Indeed, nearly every nonwhite industrial musician lives in America, including Charles Levi and Jacky Blacque of My Life With the Thrill Kill Kult, Ministry engineer and keyboardist Duane Buford, the members of Code Industry, Noise Box’s Dre Robinson, and members of Hawaiian Cleopatra Records signee Razed in Black. Brit Dean Dennis of Clock DVA and Amadou Sall of the French act Collapse are among the only exceptions.

Industrial acts from within the Black Atlantic region—especially American musicians—comment musically on race less frequently than those based elsewhere. Generally, by the late 1980s in America leftist white musicians, regardless of genre, shared an understanding that, however benevolent the intention, their overt critiques of racial power dynamics contributed little to what was an already exceedingly rich discourse in African American and Latin American music, and in fact many felt that by speaking they risked silencing other voices in this dialogue. This, combined with a few particularly mortifying public instances of white attempts to co-opt hip-hop (including rapping commercials for Chicken McNuggets and Fruity Pebbles), contributed both toward the relative lack of white American music expressly about race (including industrial music) and toward the perception that genre lines were racially enforced. The difference of approach to race in music between Europe and North America has a story all of its own, and it includes, among other chapters, a white British fascination with reggae in the 1970s and some often-overlooked German forays into rap idioms in the early 1980s, among them Spliff’s “Das Blech” and Die Toten Hosen’s “Hip Hop Bommi Bop.”*

There are a few important exceptions to the rule that American industrial music avoids race as a lyrical topic. As discussed in the preceding chapter, San Francisco’s ultra-Marxist industrial rap act Consolidated often invited confrontation, and they delighted in interspersing their album tracks with live recordings of their political sparring with concertgoers. In one such encounter, documented on the 1991 track “Murder One,” an African American man expresses concern that the band is speaking on behalf of minorities despite “not going through what I’m going through.” This leads to their inviting him on stage to speak and rap for himself. More noteworthy in this category is the band Code Industry, who were probably the first (and perhaps the only) all African American industrial act to release a record. On their 1990 debut, released only in Belgium on Antler Subway, racial politics are submerged, but 1992’s followup (distributed by Caroline Records in the United States) was called Young Men Coming to Power and boldly asserts a revolutionary stance, complete with Malcolm X samples. A few years later, Seattle-based Noise Box released “Monkey Ass.” The song begins auspiciously with a sample of Black Panther founder Bobby Seale declaring, “We’re gonna walk on this racist power structure and we’re gonna say to the whole damn government… motherfucker, this is a hold up.” Both “Monkey Ass” and Code Industry’s later oeuvre invoke a militant language reminiscent of Public Enemy—at once a call to political action for racial minorities, a scathing exposé of institutional western racism, and a celebration of collective expression.

If these are exceptions, though, then we can at this point summarize the racial politics of the genre. What follows are tendencies, not rules, and they are based on past industrial practices, not necessarily current or future ones.

Like nearly all western popular styles, industrial music derives its rhythms from African Diaspora music, but notably it also celebrates a political and musical kinship with postwar experimental jazz. However, industrial music more readily appreciates this music’s experimental status than its racial origins. A few exceptional figures aside, industrial music in general passively presumes whiteness, as evidenced by its cavalier use of caricature and exotica, both of which declare racial otherness to be a playground. Thus, despite its ostensibly parallel ideals of freedom from oppression and technologically rewriting the past, industrial music has been largely oblivious to its own potential for a radical discourse of real politics, resulting in its consistent use of African-derived signifiers as barely differentiated from any other.

It’s possible that this presumption of whiteness is inextricable from the genre’s central debates. To move beyond empirical history and into a bit of theory, recall that a large amount of industrial music is concerned with mechanically replacing the body. This move is much easier when the body is hegemonically invisible—when it’s “normal” enough to be blindly assumed, and thus inessential to one’s identity. Questions of the body—like whether it’s necessary or outmoded, or whether it’s a site of pleasure or a site of discipline—are available to industrial music largely because of the normativity of whiteness within the western culture it participates in (or rails against): in the west, the white body is not a site of constantly reinforced difference, and so it can be ambiguous and amorphous in industrial music. A body of another race, however, is almost always fixedly at the center of hegemonic attention, demanding definition. In turn, because industrial music has so privileged these debates over the body’s different meanings, it tends to be a poor stylistic fit for racial otherness, in which one has less control over the dialogue of social identity that surrounds one’s own body. It’s therefore no surprise that most moments indebted to free jazz within the genre don’t happen within electronic body music. Front 242’s Patrick Codenys cautiously explains: “We were asking what ‘white rhythm’ meant, because people talk about black rhythms or Hispanic rhythms. That idea of EBM, the physical body, white rhythm—it comes from something very mathematical and very tribal.”23 In short, industrial music’s politics themselves are in conflict with the otherness of the body; if racial status is culturally foisted upon a body as its primary concern, then the issue preempts both Skinny Puppy’s abject destruction of the body and Laibach’s commanding it in salute.

As an appendix to this chapter, let’s explore one final intersection, considering industrial music’s largely Anglo-Saxon heritage for the time being not as a hegemonic blind spot but as a meaningful source of musical traditions. Scholar Peter Webb has correctly connected the dots between industrial music and the neofolk genre. Sometimes called apocalyptic folk, this style freely employs the noise textures, military soundscapes, quasi-totalitarian imagery, and thematic direness of Throbbing Gristle and Whitehouse, but unlike those acts neofolk bands such as Death in June, Current 93, and Sol Invictus are also steeped in the folk music revival and psychedelia of the 1960s. Neofolk’s antecedents use modern technology to comment on the past; industrial music arose in response to the postindustrial society, and as folk music historian Britta Sweers makes clear, the electric instrumentation of hippie-era revivalists such as Fairport Convention and Steeleye Span was directly tied to how they explored “the exotic and grotesque … mythic topics.”24 Both industrial music and electric folk are also rooted in the imagery of (and occasionally the participation in) pagan belief systems.

Although the development from early industrial music into neofolk has been made clear through shifts in personnel and musical practices, not much has been said about how archaic folk derivations have fed back into industrial music’s dance-oriented strains. Earlier in this chapter and in this book, the idea of repetition in pop music was cast in terms of the African diaspora and technology: machines make possible a never-ending groove. Consider here a partial supplementary explanation for this repetition, one that stems from the ever-present repetition in the British Isles ballads so favored by late-1960s electric revivalists and neofolk bands alike.

In his book Origins of the Popular Style, Peter van der Merwe writes:

In European folk music, as in African music, the repeated cycle remain[s] the standard form. It might be closed, that is, come to an end in the familiar way, or open (or, as it is sometimes put, circular), where instead of coming to a close, the tune simply repeat[s] itself indefinitely.25

A clear example of this is “Twa Corbies,” an English-Scottish ballad with a text dating to 1611 and a melody adapted from the old Breton song “An Alarc’h.” After being popularized by electric folk band Steeleye Span in 1970, “Twa Corbies” became a mainstay in the repertoires of neofolk acts Sol Invictus (1989) and Omnia (2006). “Twa Corbies” consists of a repeated melody, with every line in every verse based on the same melodic ascent of a third. In the earliest printed version of the melody (1839), thirty-two verses were to be sung, though in most later versions this number is reduced to five.26 The ballad’s lyrics (about crows in a tree), its modal tune, and the brightly majestic arrangements that bands drape around the song all emphasize repetition within the modern context of a mythic, lost England.

Even if neofolk acts themselves seldom make industrial dance music, one could reasonably suspect that the highly repetitive old northern European melodies and texts that so compel them have assuredly crossed back into the central vocabulary of industrial music. In certain industrial songs, the cyclical relentlessness we hear is not merely technology’s resonance with blues-derived musical practice but an arcane assertion of a pre-modern tradition.

Among the clearest examples of British Isles balladry in industrial music is 1993’s “Soldiers Song” by the Swiss act Spartak. The track is a highly appealing EBM cover of “The Kerry Recruit” (also called “The Irish Recruit”), a ballad about the Crimean War of the 1850s, first collected in an 1870 issue of Putnam’s Magazine.27 The band’s interest in folk music had been evident in their earlier song “Volkstanz.” On “Soldiers Song,” Spartak’s vocals are arranged as a unison male choir, which suggests a certain workmanlike solidarity—a sound that the band Funker Vogt would later make their trademark.

We might also consider the 1989 club hit by Controlled Bleeding “Words (of the Dying).” Though the band has at times identified as a noise act, this song comes from a period when they were signed to WaxTrax! and were releasing a fair amount of dance music. The song’s rhythm loop is built around a flammed drum pattern, the snare rolling just enough to militarize the beat. Harmonically and melodically, the song is almost entirely composed with the black keys of a synthesizer, giving it a folky modal sheen while perhaps suggesting the band’s limited comfort with keyboard performance. The chorus of the song is a two-measure sequence with alternating G-flat and A-flat major chords, one per measure, and this pattern continues six times as the chords rock back and forth, resolving indifferently to E-flat minor. It’s in this repetitive chorus pattern that the influence of old music filtered through electric folk and neofolk is heard: the upper vocal part is an unsyncopated leaping gesture whose lower note, instead of fitting into the sounding chord, follows a melodically determined sequence.

![]()

The effect of the straight rhythm, its short repeated cycle, and the modal emphasis on melody (in the absence of harmonic consideration) is unambiguously folkish. Paul Lemos, who cowrote the song, doesn’t recall specifically channeling folk music in its composition—“If anything, it was our attempt to sound a bit like D[epeche] Mode, whose music Chris [Moriarty, his bandmate] was really digging at that time.” But influence is seldom a one-to-one correlation; Lemos does grant that during this time “I came to really like Fairport [Convention], Nick Drake and others in this genre.”28 The band’s pronouncement that “We’re very interested in the music that was developing in Europe, from the period of 1100 or 1200 to 1400 or 1500,” speaks loudly of an openness to old forms like the English ballad—the first of which (“Judas”) appeared in the thirteenth century.29

A third convincing example might be the 1998 song “Genetik Lullaby” by the Pennsylvania-based act THD (or Total Harmonic Distortion). The melody of the verse follows a logic identical to “Words (of the Dying),” in which a two-note cycle—as before, played just on black keys—is transposed upon repetition (Figure 14.9).

![]()

This pattern repeats eight times before the chorus ever arrives, again always guided by melodic considerations that effectively ignore the unchanging harmony. Despite the aggressive dance beats of the song, its compositional seed was this melody, which as frontman Shawn Rudiman explains immediately sounded like a lullaby when he first thought it up.30 Verses commence with “Hush little baby, sleep,” and “Hush little child, don’t you cry”—derivations of “Hush-a-by baby” from the English book of children’s folksongs Mother Goose’s Melody, dating back at least to 1796.

Even stranger is the case of “Little Black Angel,” which began as “Brown Baby,” a 1958 spiritual by African American activist Oscar Brown Jr. and was subsequently rewritten as “Black Baby” in 1973 by Marceline Jones, the (white) wife of Rev. Jim Jones, whose cult’s nine-hundred-member suicide in 1978 made headlines. In 1992, Death In June rewrote the song’s lyrics to address an angel (note the bodiless-ness here) and altered its music, replacing the vibrato-rich organ, free rhythm, and melodic glides with majestic acoustic guitars in rigid 3/4 time and Douglas Pearce’s declamatory British baritone. The effect is specifically a channeling of the English ballad style, almost completely replacing the soul of the original. Then in 2011, to the delight of goth club DJs everywhere, synthpop act Ladytron released their own cover of Death In June’s rewrite of Marceline Jones’s rendition of Oscar Brown Jr.’s song. Filtered through Death In June’s über whiteness, the song’s transformations make musically clear the stylistic influence of the British Isles ballad on music from outside its tradition. Ladytron’s end result is appropriately befitting an industrial club, complete with pounding kick drums and synths in an unflinching 4/4 meter and a vocal performance so compellingly sterile as to be creepy.

Ladytron found their way to Death In June’s ballad-esque catalogue, Controlled Bleeding captures a particularly northern sense of nobility in their alternating chord progressions. THD channels the lullaby tradition, and Spartak directly recreate an Irish ballad: these examples are evidence that industrial music, almost certainly more so than most other pop, is in meaningful dialogue with British Isles folksong. This is hardly a surprising claim, given how often industrial musicians play concerts and share record labels with faux-medieval and neofolk acts, but it’s an important point.

It’s also important to remember that the conversation between archaic folk music and industrial goes two ways: plenty of acts have straddled the stylistic line successfully. For example, sometime WaxTrax! artist In the Nursery had, on one hand, made a name for themselves by recording orchestrally tinged military new age music and scoring silent films that directly depict a “lost England,” while on the other hand they’ve packed club dancefloors with remixes by Flesh Field, Haujobb, and Assemblage 23. More recently, the French act Dernière Volonté has similarly hybridized industrial dance and neofolk. The upshot of all of this is that in the songwriting and production of industrial music, when we hear repetition, we should recognize not merely the confluence of technology and African heritage that pervades nearly all western dance styles of the late twentieth century but also a rare strain of something expressly European, conjuring the past through its relentless repetition.