CHAPTER 7

Liminal worlds

The British Early Upper Palaeolithic and the earliest populations of Homo sapiens

INTRODUCTION

From a northern European point of view, an interrupted archaeological record indicative of successive dispersals and regional extinctions is the rule throughout the Upper Palaeolithic (Verpoorte 2008). As with the preceding Middle and Lower Palaeolithic, hominin groups dispersed into the region infrequently and the relatively precise chronology available for the British Upper Palaeolithic reveals that it was interstadials, some of which approached the Holocene in terms of mean temperatures, which ultimately facilitated the northwestwards dispersal of grassland faunal communities into Britain. Only towards the end of the Pleistocene can one identify a boreal woodland community – in the second half of the last interstadial before the Holocene – an indication of the Early Holocene and Mesolithic communities to come. As will be seen below, the British Upper Palaeolithic record is remarkably sparse and even the Late Magdalenian/Creswellian record of the first half of the Late Glacial Interstadial need represent, in our opinion, no more than the activities of one group resident for a handful of years.

Traditionally, the British Upper Palaeolithic has been divided into two: an Early Upper Palaeolithic preceding the Last Glacial Maximum, and a Late Upper Palaeolithic following recolonisation of the Northern European Plain as the severe conditions of the LGM ameliorated (Campbell 1977). In this chapter we examine the former.

CLIMATES, ENVIRONMENTS AND RESOURCES

The climatic oscillations of MIS3 and their environmental implications have been discussed fully in Chapter 6 and as the time period covered in this chapter essentially forms part of the continuing climatic instability of the period only a brief summary is necessary here. In the NGRIP core at least eight interstadials are recorded for the period ~38–28 ka cal BP – Greenland Interstadials (GI) 8, 7, 6, 5, 4 and 3 (from oldest to youngest; Svensson et al. 2008). In terms of the terrestrial record, of the five interglacials recognised in northern Europe for the period ~58–28 ka cal BP (Zagwijn 1989; Behre 1992) two are relevant to the concerns of this chapter: the Hengelo (~39–36 ka cal BP) and the Denekamp (~32–28 ka cal BP). In Britain, however, only one clear interstadial – Upton Warren – has been indentified at present (Coope et al. 1961) which, at apparently ~42–44 ka cal BP, precedes the arrival of Upper Palaeolithic groups. However likely it is, therefore, that Early Upper Palaeolithic dispersal into Britain was restricted to certain interstadials, the rarity of dated assemblages and chronological imprecision make this difficult to demonstrate convincingly at present. More broadly speaking, in terms of a three-phase model for MIS3 (see Chapter 6) the arrival of Homo sapiens coincides with the phase of climatic deterioration with relatively tightly spaced oscillations down to ~37 ka cal BP and the onset of cold stadial conditions thereafter.

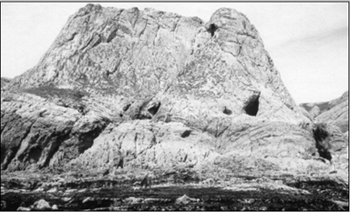

From modest origins in the Scottish Highlands the British–Irish ice sheet (BIIS) expanded between ~40 and 33 ka cal BP (Chiverrell and Thomas 2010) although it would not be until MIS2 that the glaciers reached their Last Glacial Maximum limits across the entirety of Ireland and northern Scotland (see Text Box 7.1). As noted in Chapter 7 the pre-LGM Devensian BIIS was probably highly dynamic, fluctuating in nature over the course of the period, although given the coarseness of the terrestrial data, details of the extent of such fluctuation are at present unavailable. Remains of woolly rhinoceros from Dunbartonshire in central Scotland, for example, have been dated to 31,140 ± 170 14C BP (OxA-19560) and 32,250 ± 700 14C BP (OxA-X-2288-33) and reveal that the region must have been free of ice ~34.7–35.8 ka cal BP (Jacobi et al. 2009). Whatever the dynamics, organic deposits immediately south of the BIIS margins indicate that the cold, open tundra landscape that characterised MIS3 persisted until the climatic deterioration into the LGM (Chiverrell and Thomas 2010).

Text Box 7.1

THE LAST GLACIAL MAXIMUM IN BRITAIN

During the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) Britain, northern Germany and northern France were, it seems, completely depopulated (Roebroeks et al. 2011). Glacial ice began to accumulate once more from ~32 ka BP (Telfer et al. 2009) and it is probably significant that the youngest Mid Upper Palaeolithic activity in Britain dates to ~33 ka BP. Most specialists now agree that approaching the LGM, the maximum extent of the British–Irish Ice Sheet (BIIS) was reached ~27 to ~24 ka BP (Scourse et al. 2009a; Clark et al. in press) corresponding to maximum global ice volumes over the same period (Boulton and Hagdorn 2006; Peltier and Fairbanks 2006; Clark et al. 2009). The BIIS was a relatively small and discrete ice sheet (Hubbard et al. 2009), the growth and deglaciation of which seems to have been dynamic, marked by regional differences in deglaciation rates, standstills and readvances, and there is as yet no consensus on the extent and variability of such dynamism (e.g. Fretwell et al. 2008; Clark et al. 2010). Rapid ice advances and retreats have, for example, been suggested for the North Sea, that is, down the the east coast of England; the west coast of Scotland and Ireland and the Scilly Isles (Clark et al. 2011; Bateman et al. 2011) and such fluctuations are known across the world (Clapperton 1995). The precise extent of the LGM BIIS is unclear, as is the question of whether it was confluent with the Scandinavian Ice Sheet (SIS), although recent micromorphological analysis of sediments from North Sea cores suggest that they were joined during at least two periods within the Devensian (Carr et al. 2006). In contrast to modern ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica the BIIS had a relatively low elevation and extensive, active, elongated lobes at its margins (Boulton and Hagdorn 2006; Bateman et al. 2011). The extent of the BIIS in the North Sea is still known only imprecisely. Diamictons of the Cape Shore Formation extend across much of the North Sea basin from the Norwegian Channel to the northern parts of East Anglia, indicating extensive glaciation that peaked ~27 ka BP. Those of the succeeding Bolders Bank Formation form a large lobe extending up to 50 km off the north-east coast of England and across much of the southern North Sea to Dutch territory, probably reflecting a readvance after ~22 ka BP (Carr et al. 2006).

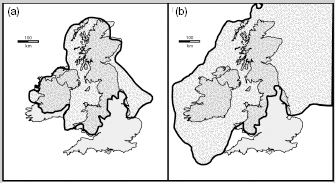

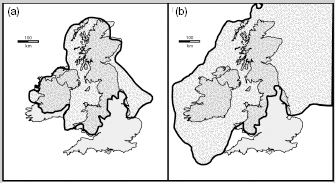

On land, the extent of the glaciers across the British and Irish land mass is better known (e.g. Boulton and Hagdorn 2006; Clark et al. 2004; Greenwood and Clark 2009; Shennan et al. 2006; Chiverrell and Thomas 2010). This has traditionally been mapped on the basis of the distribution of diamicts, end-moraines, eskers, drumlins, weathered/unweathered landforms, meltwater channels including tunnel valleys, weathering limits (trimlines), ice-dammed lakes and erratic dispersal patterns (Clark et al. 2004; Chiverrell and Thomas 2010; see Figure 1). Two large lobes extended down the Vale of York and the eastern English coast, extending respectively as far as Escrick or Doncaster, and down the east Lincolnshire coast and over the Wash (Bateman et al. 2011).

FIGURE 1

Approximate limits of the Last Glacial Maximum ice over Britain; (a) after Boulton et al. 1977; (b) after Scourse et al. 2009a.

A series of moraines mark the southern limits of the LGM BIIS across the Wye Valley in Hertfordshire and in south Wales around Abergavenny and Usk. Periglacial deposits on Gower reveal that most of south Wales was covered by ice (e.g. Hiemstra et al. 2009). Ice streams ran from the southern Irish Sea basin past the coasts of Pembrokeshire and Wexford to west of the Isles of Scilly (Scourse et al. 2009a and references therein). In southern Ireland a subglacial diamicton indicateS its presence over much of the country and an extension well out into the Celtic Sea and moraines off the coast of Connemara indicate probably complete coverage of the west coast. Estimates of the thickness of the ice sheets vary. The highest parts, such as in the Scottish Highlands, could have reached anywhere between ~950 m and over 1,800 m (depending on which physical model one favours) and approached 700 m in Ireland (Ballantyne et al. 1998, 2008). Fretwell et al. (2008) used digital terrain mapping to model the extent and volume of the ice based on three existing ice sheet models. Unlike previous models, this technique takes into account the effects of topography on overlying ice volumes. The results of these models indicate a variable thickness of ice cover with central cores of very thick ice (900-1,600 m) over regions such as the south-east Grampians, the inner Solway Firth and northern and central Ireland. These cores were surrounded by extensive areas of very thin ice (<100 m), and potentially abrupt transitions from ~1,000m to zero in a few kilometres.

Global sea level during MIS2 was ~114–35 m below that of the present day (Shennan et al. 2006) and most of the North Sea basin and eastern parts of the English Channel were dry land (Coles 1998). Coleoptera suggest extensive snowfall during the height of the LGM (Atkinson et al. 1987) and all areas free of ice witnessed severe periglacial conditions during the LGM, as evidenced by significant river incision, solifluction and cryoturbation from the south-west to south-east. The aggrading, braided, gravelly rivers flowed through treeless, polar landscapes barren of mammalian life (Walker 1995; Collins et al. 1996 and references therein). The increased winds of the period distributed coversand and loess across large areas of southern and eastern England throughout the period and even during deglaciation (Bateman 1998; Bateman et al. 2008; Reynolds et al. 1996; Clarke et al. 2007). Apart from the glaciers the large proglacial lakes Humber and Pickering, dammed by North Sea basin ice, were prominent features of Late Devensian Britain, covering ~4,500 km2 (Bateman et al. 2008).

Biostratigraphy and faunal turnover within later MIS3 and early MIS2

Biostratigraphically, the period is characterised by the taxonomically rich Pin Hole MAZ discussed in Chapter 6 (Currant and Jacobi 1997, 2001, 2011). Dominant taxa were spotted hyaena, mammoth, horse, woolly rhinoceros, bison and reindeer. Fox, lion, arctic hare and humans were also relatively familiar although perhaps unevenly distributed elements. As Turner (2009) has noted, the relatively persistent presence of lion and hyaena throughout MIS3 indicates a relatively rich resource base of herbivores. Following MIS3, the Dimlington Stadial Interzone that opened MIS2 has yielded a comparatively impoverished mammalian fauna, reflecting the severity of the climate as conditions deteriorated towards the Last Glacial Maximum (see Chapter 8). Some faunal changes, however, distinguish the Early Upper Palaeolithic world from the preceding Middle Palaeolithic one. Hyaena and woolly rhinoceros seem to have become extinct in Britain by ~36–37 ka cal BP (Stuart and Lister 2007) and Neanderthals probably followed shortly thereafter depending on whether or not Lincombian–Ranisian–Jerzmanowician (LRJ) assemblages are a proxy indicator of their presence or not (see below). The lesser scimitar-toothed cat, Homotherium latidens, may have been active in Britain during MIS3; a dentary of this species from south-east of the Brown Bank has been directly dated to 28,100 ± 220 14C BP (UtC-11000, tooth) and 27,650 ± 280 BP (UtC-11065, mandibular bone) revealing its presence within 50 km of the current East Anglian coast ~31–32 ka BP (Reumer et al. 2003), and the recovery of a tooth assigned to this species apparently associated with Late Upper Palaeolithic archaeology from Robin Hood Cave at Creswell Crags – although undated – may suggest the Late Pleistocene persistence, or arrival, of this predator on the British Mainland (Jacobi 2006).

It should be remembered that the Pin Hole MAZ is a formal biostratigraphic zone apparently covering ~35,000 years of Upper Pleistocene time, not a reflection of specific faunal communities over this period, which were presumably constantly remodelled in response to the highly unstable climate of the period. One assumes that such fluctuations – probably occurring at the level of centennial- and millennial-scale climate change at the very least – form the context in which successive hominin dispersals and extinctions in Britain occurred although, given the relatively low number of well-understood palaeontological assemblages and the imprecision of chronometric dating for the period, such fluctuations are only very poorly understood. Some indications of MIS3 faunal turnover have been observed in the Goat’s Hole at Paviland on the Gower Peninsula, south Wales (often referred to as Paviland Cave) and at Pontnewydd Cave in north Wales, both the result of ambitious radiocarbon dating projects in the context of major new analyses of old archaeological and palaeontological collections (Aldhouse-Green 2000a; Aldhouse-Green et al. in press). At Paviland a relatively impoverished fauna of woolly rhino, reindeer, aurochs and bear, possibly attributable to the MIS4/early MIS3 Banwell MAZ, was replaced by a richer ‘mammoth steppe’ community ~33 ka BP (Pettitt 2000). This community included humans in the form of Mid Upper Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers, apparently reaching Britain as a small-scale and momentary dispersal prior to the decline of conditions as they began to approach the Last Glacial Maximum (see Text Box 7.2).

Text Box 7.2

DISPERSAL OF THE MAMMOTH STEPPE AND THE ARRIVAL OF THE GRAVETTIANS

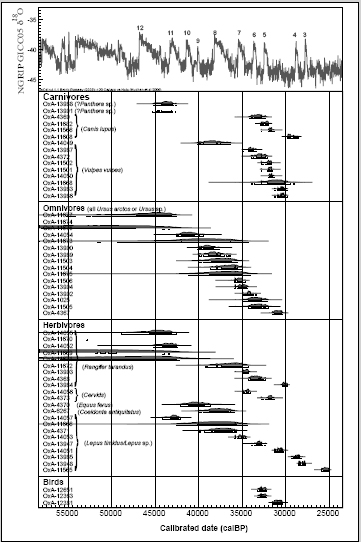

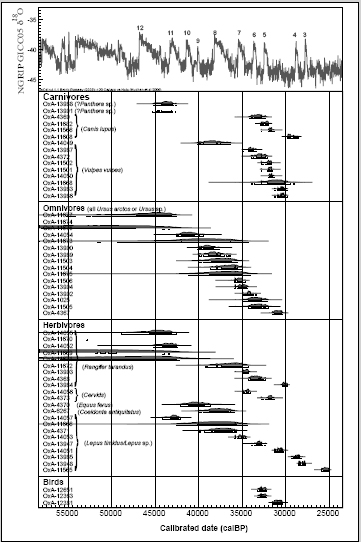

Pontnewydd Cave in north Wales and the Goat’s Hole, Paviland, in south Wales have yielded large amounts of Pleistocene fauna that have been the subject of major radiocarbon dating projects (Pettitt 2000; Pettitt et al. in press; see Figure 1) in the context of major reassessments of the caves’ archaeology and palaeontology (Aldhouse-Green 2000; Aldhouse-Green et al. in press). These have revealed fluctuating faunal communities over the period ~41 to ~28 ka BP and, at Paviland, directly dated human remains and humanly modified artefacts reveal how Gravettian groups were an integral part of this animal community. Despite some taxonomic differences – the presence of hyaenas and humans at Paviland for example – broad similarities exist between the two caves.

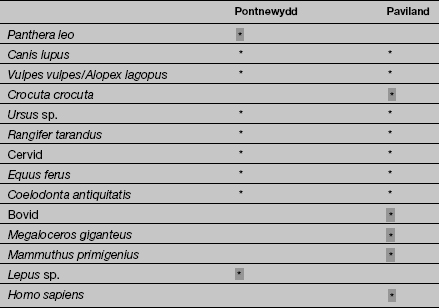

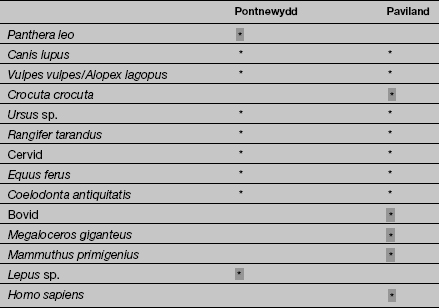

With twelve faunal taxa (including humans) Paviland is taxonomically richer than Pontnewydd (nine, lacking humans) (see Table 1). The two caves share seven taxa (three carnivores – wolf, fox and bear, and four herbivores – reindeer, cervid, horse and woolly rhino). Five of these overlap chronometrically although horse and unspecified cervid appear to have occurred earlier at Pontnewydd. Lion and arctic hare are present at Pontnewydd but are entirely absent from Paviland. With the exception of woolly rhinoceros and reindeer, which may have been present at Paviland before ~41 ka BP, there is an abrupt appearance of several taxa from this time, revealing a quadrupling of taxonomic diversity. Around the same time taxonomic diversity doubled at Pontnewydd, indicating the appearance of the rich mammoth steppe faunal community in the west of Britain at this time.

FIGURE 1

Calibrated age ranges of direct AMS radiocarbon measurements on fauna from Pontnewydd Cave, plotted against NGRIP climate curve. (From Pettitt et al. in press.)

Table 1 Taxonomic composition at Pontnewydd and Paviland between ~41 and ~28 Ka BP, after Pettitt et al. in press. Shading denotes the presence of a taxon at one site which is unknown from the other.

At Paviland, bovids and the extinct giant deer Megaloceros had appeared by ~36 ka BP, and mammoth by ~33 ka BP. To this one may add the presence of culturally Gravettian humans ~33 ka BP (Jacobi and Higham 2008) and wolves and hyaenas at least from ~32 ka BP. Clearly by this time the faunal community of GI6 was rich enough to support three social carnivores. Similar rises in taxonomic diversity are recorded at Pontnewydd ~41 ka BP and ~33 ka BP, although the absence of humans is notable. By contrast to Paviland, bears (Ursus arctos or Ursus sp.) were common here between ~41 and ~30 ka BP although, as there is no evidence of Gravettian presence anywhere in north Wales, it seems that this is a genuine regional absence rather than competitive exclusion from the cave by bears. The floruit of fox at Pontnewydd after ~34 ka BP (a rare taxon at Paviland) further reflects a regionally distinct faunal community in the north of Wales from this time.

At both sites very few fauna date to younger than ~30 ka BP. Clearly a significant diminution of populations occurred at each site from this time, presumably reflecting the faunal depopulation of Wales as conditions deteriorated into the Last Glacial Maximum.

A rich fauna from the Upper Breccia at Pontnewydd Cave, Clwyd, spans later MIS3 to the beginning of MIS 2, that is, Currant and Jacobi’s Pin Hole MAZ and possibly into the Dimlington Stadial mammalian interzone. Like Paviland, an ambitious programme of radiocarbon dating has clarified a picture of faunal turnover during this period (Pettitt et al. in press). The basic composition of the Pontnewydd fauna shares elements with Currant and Jacobi’s biostratigraphy although differences can be observed which may provide important indications of regional differences in the composition of animal communities within the broad mammoth steppe. The radiocarbon dates span the period ~25 ka–~40 ka 14C BP and terminate abruptly at the end of MIS3, presumably reflecting the marked deterioration of climate into the Dimlington Stadial Interzone. It seems that the onset of severe conditions caused the localised extinction of most MIS3 faunal taxa, or at the very least a dramatic impoverishment in taxonomic diversity.

Eight of the dated faunal taxa from Pontnewydd are found in the type locality of Pin Hole cave, Creswell (Currant and Jacobi 2001, Table 5), with Pin Hole lacking only a cervid other than reindeer or Megaloceros. Compared with Pin Hole, Pontnewydd lacks mammoth, the giant deer Megaloceros, two mustelids and possibly Bison. Importantly, taxonomic diversity is relatively low in the Pontnewydd fauna compared with Pin Hole (9 taxa as opposed to 15) and is in fact similar to that for the ‘impoverished’ fauna of the preceding Bacon Hole MAZ with which it shares five taxa (Canis lupus, Vulpes vulpes, Ursus sp., Rangifer tarandus and Lepus sp.). So, taxonomically, the sampled and dated MIS3 faunal community from Pontnewydd is intermediate between the MIS4 Bacon Hole MAZ and the Pin Hole MAZ with which it is biostratigraphically equated.

Assuming the results are broadly indicative of real faunal turnover and not hopelessly distorted due to the vagaries of preservation, recovery and sampling for dating, a degree of diachronic change can be observed. A major restructuring of the faunal community seems to have occurred ~44 ka BP. Prior to this lion, bear, and possibly red fox seem to have been the only carnivores at the site, and reindeer the only dated herbivore. Taxonomic diversity increased ~42 ka BP with a concentration of dates on bear, the possible persistence of red fox, and the appearance of wild horse, woolly rhino and Lepus (hare). Later still, ~34 ka BP, wolves appear, possibly in the context of the diminution or disappearance of bear. The two dated cervids fall into this phase but the only herbivorous taxon that persists through the sequence is Lepus. With the exception of one date on Lepus at ~27 ka BP, no dates are younger than ~30 ka BP, by which time local conditions may have been too severe to support a mammoth-steppe community.

A small series of radiocarbon dates on fauna from other Welsh caves – Ffynnon Beuno, Coygan Cave, Little Hoyle and Ogof-yr-Ychen – support the broad picture provided by Paviland and Pontnewydd (Aldhouse-Green et al. 1995), in the sense that their dated faunas begin ~44 ka BP and show some evidence of biostratigraphic turnover shortly thereafter. Radiocarbon dates from sites in western England or on a broad latitudinal parallel with Pontnewydd – Bench Tunnel Cavern and Kent’s Cavern, Devon; Soldier’s Hole, Hyaena Den, Uphill Quarry, Somerset; and Pin Hole, Robin Hood Cave, The Arch, Church Hole and Ash Tree Cave, Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire – although relatively few, are also consistent with the broad picture. Seven taxa dated from Pontnewydd are variably found among these sites and in the case of fox, reindeer, bear, wolf and cervid their broad age ranges overlap; in fact the only taxon conspicuously lacking among the dated examples from western English sites is Lepus. The main contrast of other Welsh and English sites with Pontnewydd is, of course, the conspicuous lack of human presence at the latter (see Text Box 7.2).

THE BRITISH EARLY UPPER PALAEOLITHIC RECORD

In this and the following chapter we follow the division of British Upper Palaeolithic into two phases, an earlier (EUP/MUP) and later (LUP) as initially proposed by Campbell (1977), separated by the LGM. One can identify both qualitative and quantitative differences between the EUP/MUP and LUP; the British EUP is represented by very few sites and, as Jacobi and Higham (2011, 181) have noted, is comprised almost entirely of lithic finds, unlike the far larger and better contextualised LUP. On the continent, the Upper Palaeolithic spans the period from ~45 ka BP to the end of the Pleistocene ~11.6 ka BP, a period over 30,000 years in duration. This includes ‘leafpoint’ assemblages which, although formally defined on technological grounds as Upper Palaeolithic are, by general consensus (although not clear demonstration), thought to have been made by Neanderthals. Britain seems to have been devoid of human occupants for much of this period. Even radiocarbon dates for MIS3 – the few that exist – are relatively imprecise, with errors typically spanning at least 1,000 radiocarbon years at 2σ. Even taking these large degrees of chronological uncertainty into account, the period they cover amounts to no more than ~5,000 total years of radiocarbon time spread over five or so occupational phases. This is of course a small number of measurements, sampling human occupation that may have been more frequent in time, although there are no reasons to believe on the basis of the remarkably poor archaeological record of the British Early Upper Palaeolithic (EUP) and Mid Upper Palaeolithic (MUP) that occupation was anything other than brief. Despite intensive excavations in the country’s major known caves, and intensive prospecting of both major and minor river valleys, the EUP and LRJ record amounts to no more than a few hundred finds from around 60 sites, and of these the majority represent single findspots rather than assemblages. The latter, where they exist, are small, usually less than 50 artefacts. Thus, EUP and MUP humans may well have been active in the British landscape for far less than 5,000 radiocarbon years, probably for a total period countable in years or tens of years rather than in centuries. A stringent reading of the existing radiocarbon dates relevant to human activity, taking into account the potentially vast exaggeration of age ranges caused by chronometric imprecision, supports such a parsimonious interpretation. Given Britain’s geographical location this is perhaps not surprising; a similar pattern of human settlement can be observed for neighbouring regions of the continent, such as northern France, Belgium and The Netherlands (Housley et al. 1997) and over the entire period one has to look as far south as the Loire or Mittelgebirge to find essentially continuous human presence. From this point of view, animals such as bison, aurochs and horse seem to have been far more successful in their exploitation of the western periphery of Doggerland. Far from lamenting the poor state of the British LRJ and EUP record we should be grateful that these brief dispersals, occurring in such a remote period, have left any archaeology at all.

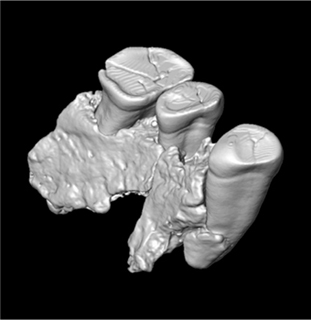

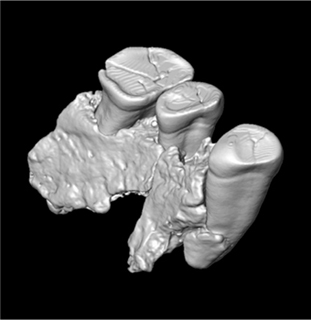

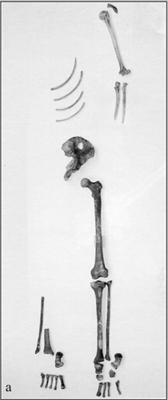

With regard to the biological species of humans associated with the British Early Upper Palaeolithic the record is effectively non-existent and one is forced to make assumptions about which species the archaeological record acts as a proxy for. The only anatomical remains apparently belonging to the period is the KC4 partial human maxilla from Kent’s Cavern (Oakley et al. 1971). This takes the form of a partial right maxilla with associated C, P4 and M1 (Oakley et al. 1971: see Figure 7.1). The taxonomic status of the maxilla has been debated for some time (Stringer 2006; E. Trinkaus pers. comm.) although on morphometric grounds now seems to be Homo Sapiens (Higham et al. 2011). The maxilla is small, the teeth are heavily worn and the shapes of the tooth crowns do not display the extreme pattern visible on some Neanderthals but given the range of variation observed in its features there is nothing clearly diagnostic in its anatomy (E. Trinkaus pers. comm.). Attempts to date the maxilla directly also failed and it is assumed to date to ~41.5–44.1 ka BP on the basis of radiocarbon measurements on faunal remains found in close proximity to the maxilla (Higham et al. 2006; Jacobi et al. 2006; Jacobi and Higham 2011; Higham et al. 2011). It is of course an assumption that these measurements broadly relate to the age of the maxilla and that dated and undated artefacts from the Vestibule – an area of intense activity – are relatively undisturbed. It is highly unlikely that such an assumption is justified. Uncalibrated radiocarbon measurements on fauna stratified 50 cm above and below the level of the mandible vary between ~41 and 46 ka BP (OxA-13921, 36,040 ± 330 to OxA-14285, 43,600 ± 3,600: Jacobi and Higham 2011 Table 11.5) but most importantly they are not stratigraphically consistent; several measurements on samples stratified above the maxilla have older mean ages than those on samples stratified below it. This clearly reveals a degree of disturbance, and as this affects dated samples up to one metre above and one metre below it is probable that mixing of material of widely different ages was considerable. Thus, while Bayesian modelling appears to resolve the age of the maxilla, individual radiocarbon measurements pertain only to the samples they date and do not have stratigraphic relevance. Even assuming that the dated samples immediately above and below it provide a reasonable estimate of its age this could still be as young as ~41 ka BP and as old as ~46 ka BP at 2σ (uncalibrated measurements: OxA-13965 37,200 ± 550 BP and OxA-13888 40,000 ± 700 BP). These are but two samples and this is assumption; we suggest that it is sensible to regard the maxilla as dated no more precisely than to MIS3.

Chronometric dating for the British Early Upper Palaeolithic and Mid Upper Palaeolithic is very poor. A handful of radiocarbon dates from a few sites reveals three main periods of activity, which may be taxonomically equated with the leafpoints of the continental LRJ, a phase of the Aurignacian and a phase of the Gravettian. There are no chronometric or typological grounds to indicate the presence of any other technocomplex, or indeed sustained or substantial settlement during these periods. As with the preceding Middle Palaeolithic and succeeding Late Upper Palaeolithic, it seems that humans were more often absent than present.

In a broad sense, British Early Upper Palaeolithic findspots are widely distributed south of the limits of the LGM glaciers (see below). This broad distribution belies other patterning, however. By far the majority of finds derive from caves, no doubt because of the intense levels of excavation activity in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, which almost always focused on these sites. Where materials have derived from openair sites these are almost always remarkably small collections and often single finds. A clear contrast with the preceding Middle Palaeolithic is the relative lack of importance of the major rivers in the distribution of EUP materials which, given that this dominates in the distribution of the Middle Palaeolithic, cannot be entirely due to sampling. As Bridgland (2010) has noted, the terrace systems of the major British rivers, so important for pre-MIS5 archaeology, reveal very little for MIS3 in general. Some patterning may, by contrast, relate to real differences in human distribution. The small number of EUP assemblages that can be classified as Aurignacian are all in the west, which may relate to contrasting dispersal and settlement patterns to the preceding LRJ and succeeding Gravettian (Jacobi and Pettitt 2000; Pettitt 2008 and see below).

FIGURE 7.1

CT scan of the KC4 human maxilla. (Courtesy Barry Chandler, Torquay Museum.)

LEAFPOINTS AND BLADE-POINTS ~42–43 KA BP

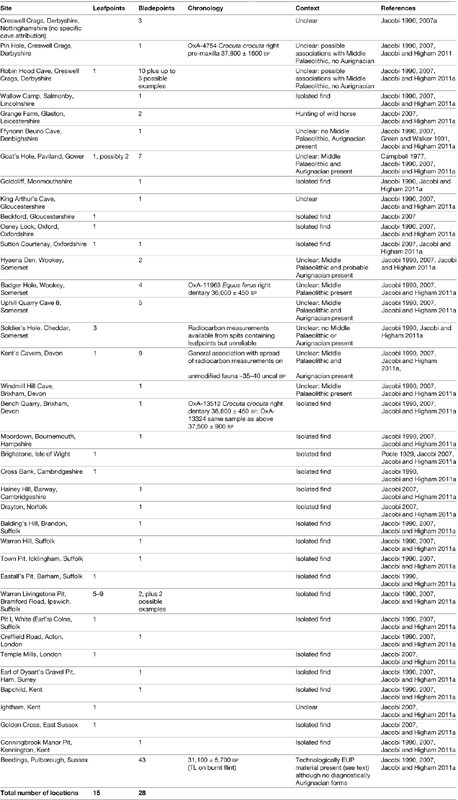

Leafpoints sensu lato are known from at least 38 findspots in England and Wales (Table 7.1). Although reliable radiocarbon dates exist only for three British leafpoint sites, those noted in the table can be accepted as reliably of Early Upper Palaeolithic age on the basis of:

• their context and/or preservational state (Jacobi 2007, 273);

• the fact that they are distinguishable from later prehistoric ‘knives’;

• the fact that Britain seems never to have played host to visits from other users of bifacial leaf-shaped points, that is, the Solutreans.

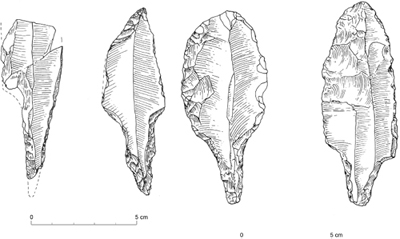

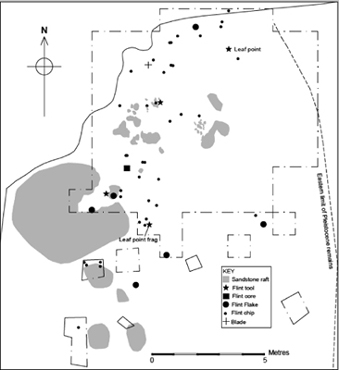

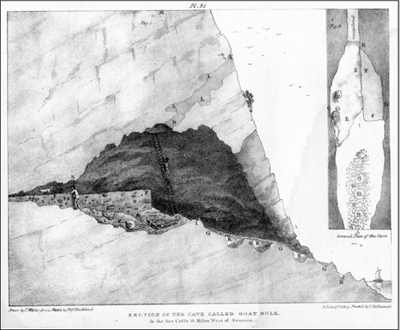

Of the known findspots, 25 have yielded either isolated solitary leafpoints or solitary leafpoints within assemblages where an association with other material is not demonstrable on the basis of available stratigraphic information. Only at three caves – Robin Hood Cave (Figure 7.2), the Goat’s Hole at Paviland and Kent’s Cavern – and two open sites – Beedings and Warren Livingston Pit in Ipswich – have more than eight examples been found and these are probably all palimpsests. Only at Beedings and Glaston is it possible to associate with any degree of confidence leafpoints with other lithic artefacts. As many of these finds were made long ago, and reported cursorily if at all, it is impossible today to establish precisely whether leafpoints contextually represent chance losses of armatures during hunting or whether they originally formed part of wider assemblages which have not been sampled. The isolation of most finds perhaps supports the former interpretation. Most of the caves which have yielded leafpoints have also yielded Middle Palaeolithic assemblages and it may be that tools and débitage classified as such were originally associated with leafpoints, although the amounts of such material are small, as seen in Chapter 6, and do not suggest intensive occupation.

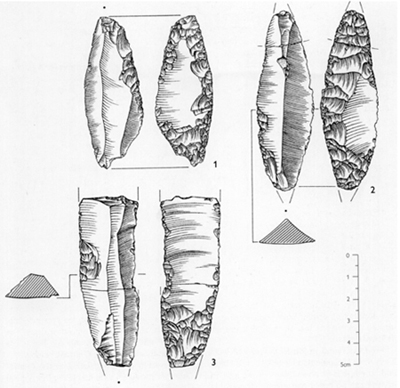

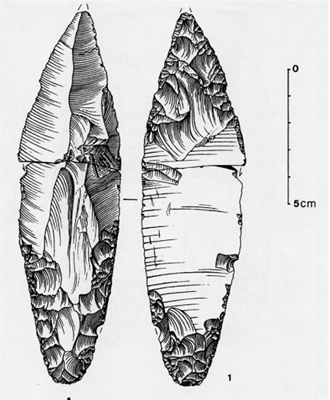

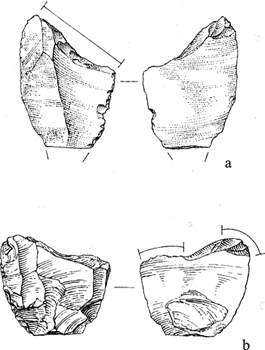

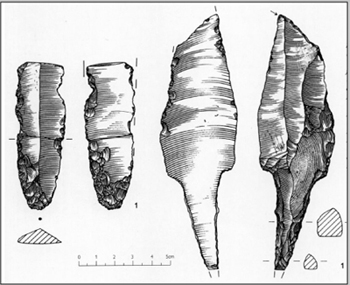

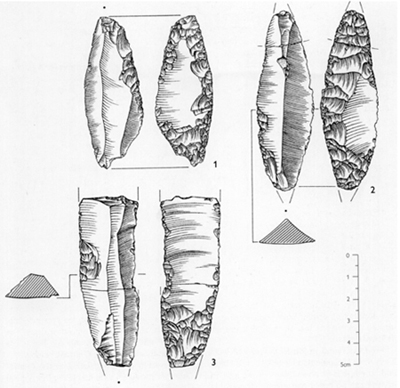

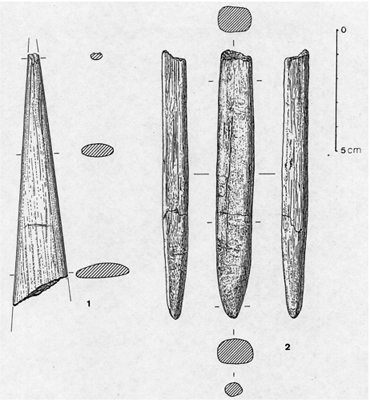

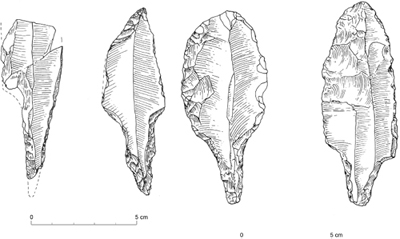

FIGURE 7.2

Bladepoints from Robin Hood Cave, Creswell Crags. (From Pettitt and Jacobi 2009; drawings by Hazel Martingell.)

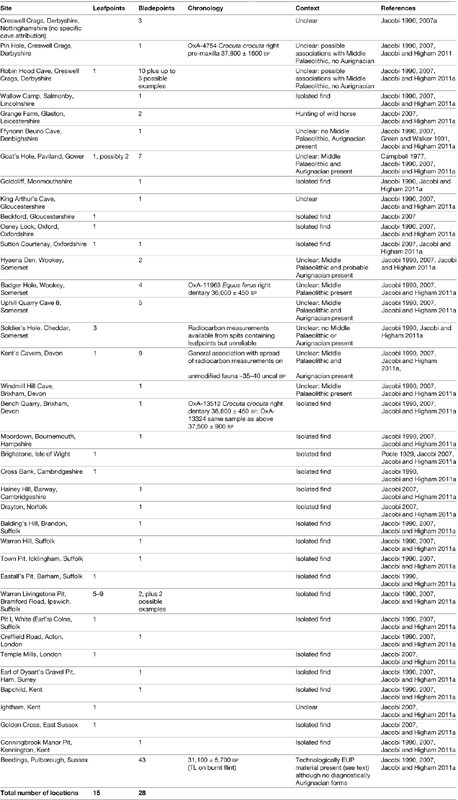

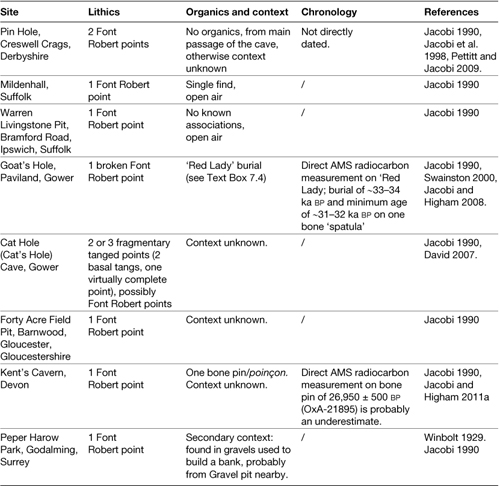

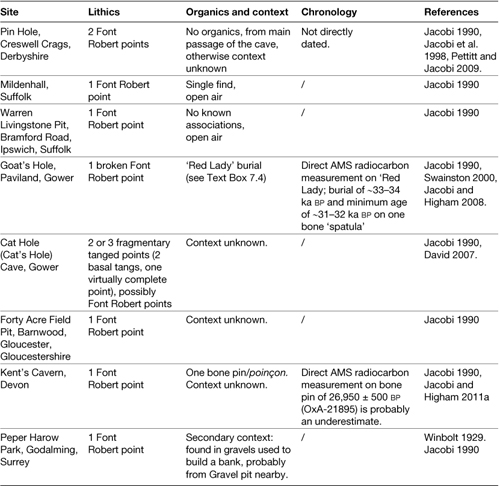

Table 7.1 Major British Late Middle Palaeolithic sites Site

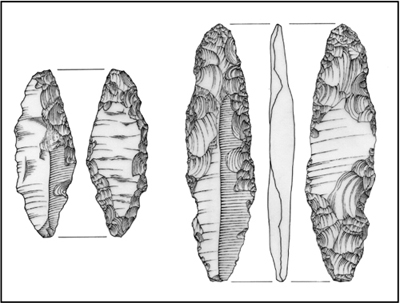

Leafpoint sites (the LRJ; see below) are found in all major British regions south of the LGM ice limits and there is no discernible geographical patterning to their occurrence. They are found in most counties up to Lincolnshire and Derbyshire in the north (Jacobi 2007; Figures 7.3 and 7.4). Four regions each contain a site with multiple leafpoints: Paviland in south Wales, Kent’s Cavern in the south-west, Beedings in the south-east and Robin Hood Cave in the north and the greatest number of sites with multiple examples is in the south west (Hyaena Den and Badger Hole at Wookey (Figure 7.5), Uphill, Kent’s Cavern and Paviland) although, given the small numbers of finds nationally, it is unclear as to whether there is any meaning to this. Indeed, the overall distribution of finds – isolated or not – shows that leafpoint users were active, at least at times, over the entire landscape that had been exploited by preceding Neanderthals. Both bifacially worked leafpoints and relatively lightly-worked blade-points (see below) can be found at the same sites, suggesting, if they do represent different populations, that their ranges overlapped in space, if not in time. Jacobi (1999, 36), for example, noted that both fully bifacial leafpoints were present at Soldier’s Hole, Cheddar, whereas partly bifacial blade-points were found at nearby Hyaena Den, Wookey. It must be said, however, that no leafpoint sites are precisely dated and individual artefacts in most palimpsest assemblages could be separated by several centuries. The general imprecision of dates in this period may therefore mask a degree of diachronic change in leafpoint assemblages.

FIGURE 7.3

Distribution of Early Upper Palaeolithic bifacially worked leafpoints in Britain

FIGURE 7.4

Distribution of Early Upper Palaeolithic bladepoints in Britain

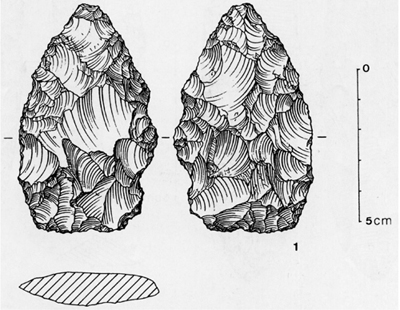

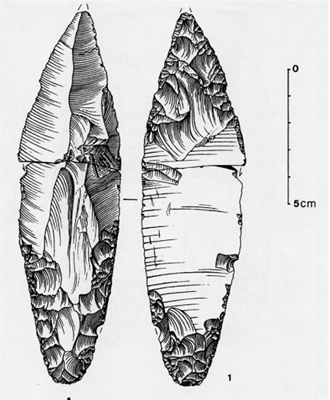

LRJ sites: technological and typological definitions

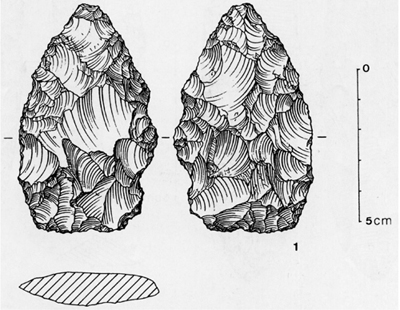

Among leafpoints in general, Jacobi (1990; 2000; 2007a) has identified two technological categories. Leafpoints sensu stricto are bifacially worked pieces showing relatively intensive manufacture through principles of façonnage similar to that used to produce handaxes. Indeed, the relatively wide form of some of these, such as that shown by the example from Kent’s Cavern (Figure 7.6) may indicate that these forms arose straight out of Late Middle Palaeolithic bifacial traditions. By contrast, blade-points (or blade leafpoints to use the term preferred by Jacobi and Higham 2011, 185) are, as the name implies, produced on the products of Middle Palaeolithic opposed-platform blade technology and usually show evidence of minimal working. On these, retouch is restricted to the ventral surface and usually only to the proximal and distal ends, functioning simply to reduce the natural curvature of the blank. Formally speaking the term ‘blade-point’ also covers partially bifacial leafpoints, Jerzmanowician points, Pointes du Spy and unifacial leafpoints. We shall use the terms leafpoint and blade-point to refer to these categories.

FIGURE 7.5

Bifacially worked ‘bladepoints’ (leafpoints) from Badger Hole, Wookey, Somerset. (Drawn by Joanna Richards and courtesy Roger Jacobi.)

Raw material probably accounts for some variability in the intensity and form of leafpoint modification. More intensive, bifacial techniques were appropriate when raw material came in the form of flattened nodules or in tabular form, whereas the relatively minimally or partially worked blade-point production was appropriate for high-quality but irregularly formed materials where the sole requirements were to straighten the longitudinal profile of the blank and point its ends. Variability can be observed in the same collections, however, although it is impossible to establish whether this was due to changes in the availability or quality of raw materials in palimpsest assemblages, or whether it relates to deliberate choice of modification methods, perhaps for different functions. As Jacobi (1990) noted, blade-points represent the manifestation of a desire to produce a straight implement in situations where raw material takes the form of irregular nodules and where thin tabular flint was rare. In such cases the retouch served to reduce the natural curvature of the object and bring about a convergence of the proximal and distal ends and thus an elongated leaf shape.

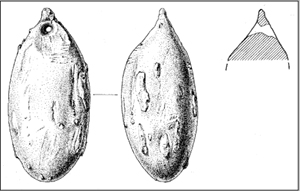

FIGURE 7.6

Bifacially worked leafpoint from Kent’s Cavern, Devon. (Courtesy Roger Jacobi.)

To our knowledge no microwear evidence of function has been established for EUP leafpoints. It is usually assumed that they functioned as weapon heads although there is no reason to suppose why their use may have been restricted to spearpoints and why some may not have been used as knives. Known British examples typically vary from ~6 cm to ~12 cm in length although the example from Cross Bank in Suffolk is ~20 cm long. In view of this one might expect some variation in function although it is of course possible that these tipped variable weapon systems. If this were the case, it may indicate that by this time different weapon systems, such as light and heavy spears, were being deployed on different prey. It is interesting in this light that, very broadly speaking, the LRJ occurs alongside other technocomplexes in which characteristic point forms were becoming more standardised, such as the Châtelperronian and Ulluzian, almost certainly reflecting developments in weaponry, and one cannot rule out the possibility that the LRJ forms part of continent-wide behavioural developments in weapon systems at this time. Several other lines of evidence support the notion that leafpoints were, in the main, weapon heads. Most findspots have yielded only singular finds, suggesting that they were hunting losses rather than tools discarded in occupational contexts; breakage patterns at Beedings are consistent with impact damage and retooling (Jacobi 2007a), and possible impact fractures have also been observed on a broken example from Buhlen, Germany (O. Jöris pers. comm. to PP). It may also be of significance that the locations of the two largest British assemblages – Beedings and Glaston (Cooper 2004; Cooper et al. in press) – are at tactically important points in the landscape suggestive of hunting stands.

Sixty-five per cent of British leafpoint sites and findspots have yielded blade-points. The figure is even greater if one accounts for the total of individual pieces; of a minimum of 125 artefacts classed as leafpoints 104 (83%) are blade-points. Clearly then, blade-points were by far the most common diagnostic element of the British LRJ. As can be seen in Table 7.1, leafpoints and blade-points are found together at only five sites (13% of the total findspots); leafpoints are found without blade-points at 10 sites (66%) and blade-points are found without leafpoints at 23 sites (82%). Clearly, in the main, leaf-points and blade-points have a relatively exclusive occurrence and on four of the five sites on which they co-occur they occur in raised number, suggesting that these sites were probably palimpsests. Although the data are poor, this patterning may suggest that leafpoints and blade-points were taxonomically separate entities during the British LRJ.

Campbell (1977) classified British leafpoint assemblages as Lincombian, after Lincomb Hill in Wellswood on the outskirts of Torquay, Devon, within which Kent’s Cavern formed. There is nothing wrong with this term, although in order to stress continental parallels we use here the term Lincombian–Ranisian–Jerzmanowican (LRJ). Jacobi’s (1990; 2007a) surveys of leafpoint assemblages included examples from both cave and open contexts. They clearly display technological and typological parallels with broadly contemporary assemblages to the east of Britain, such as Ilsenhöhle (Ranis), Mauern in Germany and Nietoperzowa Cave near Jerzmanovice in Poland (Desbrosse and Kozlowski 1988; Flas 2008) and can thus be considered to be part of a relatively continuous tradition on the Northern European Plain.

When British leafpoints are found in association with other tool forms (particularly at Beedings, Sussex) these are clearly Upper Palaeolithic in nature (if culturally undiagnostic), including endscrapers on blades and burins, although it must be said that examples of such associations are few. By contrast, there is little evidence to associate them with typologically Mousterian forms (Jacobi 1999), although undiagnostic flakes often found with them are consistent with Middle Palaeolithic technology. Campbell (1977) suggested that leafpoints formed part of a wider technology of which the few known British Aurignacian assemblages were part but, as Jacobi (1990) has noted, there are no known associations between the minimal Aurignacian presence in Britain and leafpoints. Only three sites (Kent’s Cavern, Paviland and Ffynnon Beuno) have yielded both assemblage types but this can probably be explained by the strategic position and repeated use of these caves rather than any meaningful connection between the assemblages (Jacobi 1980, 17; Figure 7.7). At Kent’s Cavern, the spatial distribution of the two artefact types was mutually exclusive. Furthermore, south of the LGM ice-limit leaf-points are geographically widespread, with many recovered from central and eastern England, a dramatic contrast to the restricted distribution of the few known Aurignacian sites exclusively in the west (Jacobi and Pettitt 2000). Thus if the two were related in a technological whole deployed by the same groups of Homo sapiens, one would have to conclude that these groups used weapons tipped with leafpoints across much of England, and then changed their toolkits radically for operating in Wales. Clearly the most parsimonious interpretation is that these two assemblage types represented distinct human populations although the issue of whether these were biologically distinct, that is, Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens, does remain to be resolved (see below).

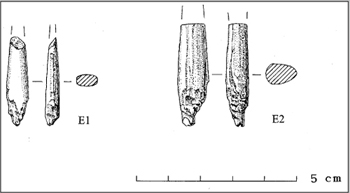

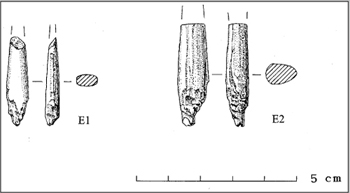

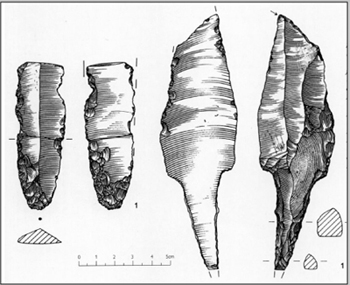

FIGURE 7.7

Welsh Early Upper Palaeolithic bladepoints. Left: Paviland; right: Ffynnon Beuno. (Illustration by Andrew David.)

Stapert (2007) observed that the frequencies of unifacial leafpoints (i.e. blade points) increases from east to west on the Northern European Plain and at their westernmost distribution – in Britain – dominate over bifacial forms. As stratigraphic observations on central European sites reveal that bifacial points (often referred to as ‘Mauern type’) apparently pre-date the unifacial forms (‘Jerzmanowician type’), he suggested that the east–west patterning may represent an actual westwards movement of Neanderthals, a ‘great trek’, which may have occurred as a response to expanding populations of Homo sapiens. Other interpretations of this patterning are possible; if the leafpoint tradition arose in the west one might expect larger numbers there, especially if the tradition were short-lived as was noted above. It is impossible to say.

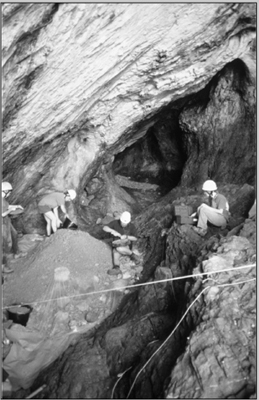

At Glaston in Leicestershire, blade-points have been recovered from an assemblage of 83 pieces (see Text Box 7.3). As noted above, however, the only British leafpoint collection that can truly be said to be part of a large assemblage is that from Beedings, near Pulborough in Sussex (Jacobi 2007a). The site has yielded by far the largest number of leafpoints in the country, amounting to ~34% of the known sample, and in fact on a continental scale only the assemblage from Nietoperzowa is larger (Flas 2008). Here, material was derived from ‘gulls’ (erosional fissures) that provided sedimentary traps in which artefacts also accumulated. The site commands extensive views across the landscape of the Sussex Weald, and is therefore suggestive of a hunting camp, although the lack of faunal preservation precludes testing this hypothesis. Originally excavated in the early twentieth century and comprising some 2,300 pieces, the collection has been considerably reduced and now only around 180 can be identified with certainty. In addition, the lack of fauna and thus dating, and the mixing within the gulls of archaeological materials of significantly different ages, severely limits the utility of the Beedings collection for understanding the behaviour of LRJ makers. As Jacobi (2007a, 271) noted, ‘there is an inevitable element of subjectivity when it comes to identifying the Early Upper Palaeolithic component of what is very clearly a multi-period collection among which there are few clues, such as condition, as to the relative ages of individual artefacts’. Despite this, his comprehensive analysis of the surviving artefacts provides a rare technological and typological context for leafpoints. The source of the flint used for the Beedings assemblage is unknown, although was probably local in the Sussex Downs. The 36 examples of leafpoint from Beedings are exclusively blade-points sensu stricto. Micro-structural fabric analysis of the artefacts showed that variable raw materials were used for non-leafpoint artefacts at the site, suggesting an ad hoc use of locally available stone, whereas far less variability was observed for the leafpoints, suggesting greater selectivity of material from a source of finer quality flint.

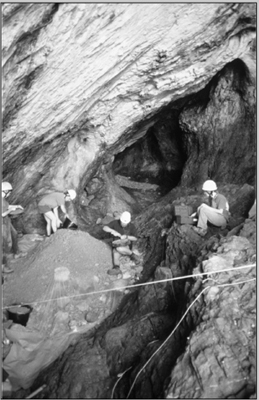

Text Box 7.3

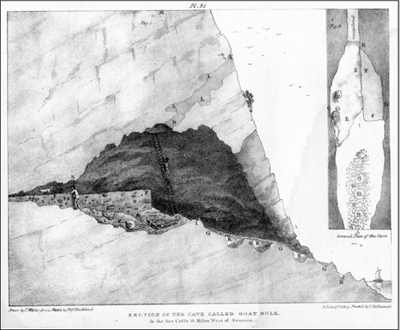

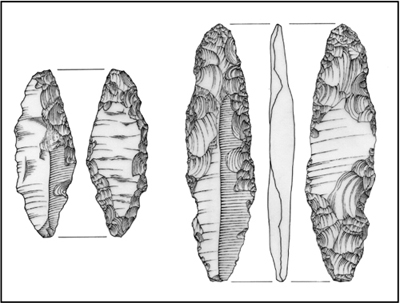

LEAFPOINTS, HYAENAS AND HORSE HUNTING AT GLASTON, LEICESTERSHIRE

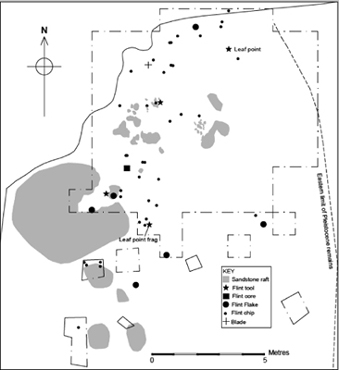

The remains of an open-air LRJ activity site and hyaena den was excavated at Glaston, Leicestershire in 2000 (Cooper 2004; Cooper et al. in press). The site is situated on the top of a ridge flanked by rivers to the north and south and was preserved when the apex subsided into a fault basin. Free standing remnants or ‘rafts’ of local sandstone presented opportunities for shelter in this otherwise exposed landscape and probably explain, in addition to the views the locale commands over the surrounding landscape, the activity of LRJ makers and hyaenas. The latter had created burrows beneath the rafts and humans exploited the shelter provided in their lee. AMS radiocarbon dates on fauna indicate that the activity occurred between ~42 and 44 ka BP, the age range of the few continental LRJ sites which have reliable dates (see main text).

FIGURE 1

The location of Glaston. (Courtesy of Lynden Cooper.)

The site yielded a lithic assemblage of 83 pieces, dominated by flakes (including trimming flakes from leafpoint manufacture or maintenance) alongside two notched flakes, and a laminar core rejuvenation flake (Cooper et al. in press). In addition to these a complete blade-point and a blade-point fragment were recovered. No local source for the flint can be identified although it is unclear how far it may have been imported onto the site. The blade-point was produced on a bipolar core in keeping with typical blank production for the LRJ (see main text). The blade-point fragment bears a bending fracture consistent with impact damage supporting the notion that leafpoints sensu lato were armatures rather than general purpose knives. Knapping clearly took place on-site, although one need invoke no activities other than the repair of weapon systems – and perhaps a degree of butchery – to account for the lithic assemblage. In this sense Glaston need represent nothing more than a hunting stop at which animals killed in the locale were eaten and weapons repaired.

FIGURE 2

Leafpoint and fragmentary leafpoint from Glaston. (Courtesy of Lynden Cooper.)

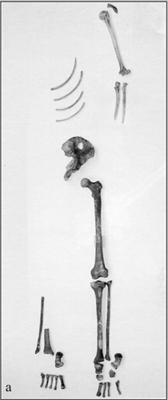

Faunal remains – which probably relate predominantly to the hyaena denning – indicate the presence of woolly rhinoceros, mammoth, wild horse, reindeer, wolverine and arctic hare, certainly indicative of a Pin Hole MAZ. Anthropogenic modifications have only been found on the remains of horse, which bear spiral fractures suggestive of marrow extraction, and which were found in close proximity to the complete blade-point (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3

Horse limb bones from Glaston showing fractures. (Courtesy of Lynden Cooper.)

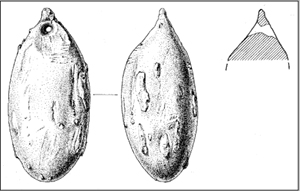

Fifty-five of the Beedings artefacts (30.5%) are formally débitage although a number of these may be of post-Palaeolithic age. Of the retouched tools, two appear to be Late Middle Palaeolithic in age: (1) a piece which can be identified either as a unifacial handaxe on a proximally thinned flake or a partially bifacial double sidescraper (2) and the proximal end of a sidescraper. A number of Late Middle Palaeolithic handaxes have been found at nearby locations in the Sussex Weald and in Kent, so an identification of a small Mousterian element at Beedings is not surprising. Between 30 and 40 retouched tools are identifiably Early Upper Palaeolithic. These include 11 burins of dihedral, break, truncation and Corbiac forms, two of which appear to have been made on fragmentary leafpoints. No single type dominates. Four or five Kostenki knives from the site have been taken by some as an indication that it is of younger (i.e. Mid Upper Palaeolithic) age, although as Jacobi points out these forms are found in Middle Palaeolithic and leafpoint assemblages on the continent. Seven composite tools, three of which are burin/Kostenki knife combinations, one a burin/endscraper, and two Kostenki knives, one with a truncation and the other lateral retouch, form the last group of tool forms. One denticulate and one piercer may also belong to the leafpoint assemblage and ten utilised pieces are indicative of a variety of tasks. Otherwise, the Beedings assemblage is overwhelmingly dominated by leafpoints, all of which, as mentioned above, are of the blade-point form (Figure 7.8). They typically have a triangular cross-section and several have been fluted, perhaps to assist hafting. All examples are broken and the symmetry displayed on fragmentary points suggests that they were finished pieces. Thus, in the main, the Beedings site represents a place where weapons/knives were being discarded, although at least two examples of leafpoint manufacture survive, suggesting that retooling was practised at least on occasion at the site; the two activities may, of course, have been linked.

FIGURE 7.8

Bifacially worked bladepoint (leafpoint) from Beedings, Sussex. (Drawn by Joanna Richards and courtesy Roger Jacobi.)

LRJ chronology

On the continent, radiocarbon dates place the LRJ between ~42 and 44 ka BP (Jöris and Street 2008, 790; Flas 2008) although it can hardly be said that the number of dated assemblages is comprehensive. The existing chronology for British LRJ assemblages is poor, although enough stratigraphical and chronometric data exist for cave sites such as Kent’s Cavern, Pin Hole and Robin Hood Cave to demonstrate at least that they post-date the Late Middle Palaeolithic as they do on the continent. The few existing 14C dates on fauna found in stratigraphic association with leafpoints suggest ages in excess of ~40 ka BP (Jacobi 1999, contra Aldhouse-Green and Pettitt 1998). As Jacobi (1999) has noted, however, there are problems with almost all radiocarbon dates on fauna apparently associated with leafpoints. We critically need new examples of leafpoints, excavated and recorded with modern methods, and ultrafiltrated radiocarbon dates on clearly associated fauna. Only at three sites – Kent’s Cavern, Bench Quarry and Badger Hole – are radiocarbon dates at all reliably associated with LRJ materials (see Table 6.1) and, assuming these are broadly representative of LRJ occupation of Britain, indicate a time span between ~42 and 44 ka BP. We are, however, sceptical about the relationship between the two at Kent’s Cavern, as discussed below. Broadly speaking then, British LRJ material is contemporary with continental LRJ assemblages in radiocarbon terms. Non-14C dates for British material, such as a TL date of 31,100 ± 5,700 BP on a burnt flint from Beedings (Jacobi 2007a), are so imprecise that they play no role in the chronological definition of Middle and Early Upper Palaeolithic technocomplexes.

Wider issues: faunal context and authorship of the LRJ

On the continental scale, evidence for the LRJ is poor. Actual assemblages exist only at Nietoperzowa Cave at Jerzmanowice in Poland (~277 artefacts), the Ilsenhöhle at Ranis, Germany (~63 artefacts) and Beedings and Glaston in Britain (Flas 2008). Its representation, therefore, is largely one of isolated finds and in terms of these the greater majority are in Britain. In view of this, the LRJ may well have been a very brief phenomenon indeed. Furthermore, the lack of LRJ assemblages excavated with modern methods, and lack of clear association with fauna, renders the broader contextualisation of this technocomplex impossible at present. Breakage fractures on wild horse bones at Glaston show that leafpoint users were exploiting this species (Thomas and Jacobi 2001; Cooper et al. in press), otherwise there are no further data, other than a broad chronological overlap between the LRJ and faunas of the Pin Hole MAZ noted above. Their pertinence to Neanderthal extinction is also severely limited; assuming the LRJ does represent the latest Neanderthals in Britain, all one can say is that they became extinct in the region some time before 40 ka BP, although this is questionable.

It is usually assumed that continental LRJ assemblages were produced by late Neanderthals. As noted above the KC4 human maxilla from Kent’s Cavern may date to ~40–42 ka BP and for this reason is usually assumed to have an LRJ cultural association (e.g. Jacobi 2007a, 307). The maxilla, however, was excavated in 1927, its location is relatively poorly recorded, one cannot trust apparent stratigraphic relationships between objects in British caves that were the subject of early excavations and, in any case, the maxilla was found in a separate area of the cave (the Vestibule) to the cluster of leaf-points. As such a lack of spatial correlation has been used to argue that leafpoints and Aurignacian materials are not meaningfully connected (Jacobi 1990, 281–5) one must follow the same logic and argue that there is no clear correlation between the maxilla and the LRJ. This situation will not improve and it is futile to continue discussing the maxilla in the context of considering the LRJ.

On the continent the picture is no better. It is usually assumed that Neanderthals were the authors of LRJ assemblages given that they are technologically rooted in the Middle Palaeolithic (e.g. Desbrosse and Kozlowski 1988, 37; Otte 1990b, 248–9; Jacobi 2007a, 305–7; Jöris and Street 2008, 388). There are, however, absolutely no associations between the LRJ and human fossils. Because of this, LRJ assemblages are usually assumed to represent a northern and central European equivalent of the Châtelperronian, which is associated with Neanderthal fossils at two sites, the Grotte du Renne at Arcysur-Cure and Saint-Césaire (Bailey and Hublin 2006; Lévêque and Vandermeersch 1980). At neither site are direct causal associations between the human fossils and archaeological industries particularly convincing, however. A major series of radiocarbon measurements on fauna from the Grotte du Renne has indicated considerable stratigraphic mixing (Higham et al. 2010) leaving no reliable cultural context for the Neanderthal teeth from the site; and the apparent Neanderthal burial at Saint-Césaire was devoid of artefactual associations. In any case there is no a priori reason why the curved-backed point tradition Châtelperronian of the south should be at all relevant to LRJ assemblages on the Northern European Plain; the only link between the two is the repeated tendency of specialists to group them under the increasingly meaningless term ‘transitional industry’. Human fossil associations are desperately needed and, until new excavations provide these, as Roebroeks (2008, 923) notes, ‘exercises in lithic phylogeny are not going to solve the debate over the character of transitional industries or their authorship’.

AURIGNACIAN DISPERSALS AND THE COMING OF HOMO SAPIENS

From a north-west European point of view the Aurignacian technocomplex provides the first unambiguous indication of the arrival of Homo sapiens (e.g. Davies 2001; Conard and Bolus 2003; Mellars 2005; Jöris and Street 2008). Although associations with fossils classed as Homo sapiens are few (Churchill and Smith 2000) a respectable and growing number of diagnostic fossils date to the period ~41 ka BP and thereafter (Pettitt 2011 and references therein). The most parsimonious reading of the continental archaeological record sees the gradual dispersal of culturally Aurignacian Homo sapiens from west to east, presumably from the Near East, with ‘Protoaurignacian’ populations established in the south of Europe by ~42 ka BP, central Europe and the Russian plain by ~40–41 ka BP and across much of Europe from ~36 ka BP (Jöris and Street 2008 and references therein). By ~40 ka BP Neanderthals seem to have disappeared from all of their previous territories whether or not one regards the LRJ and ‘transitional’ technocomplexes as proxies for their presence.

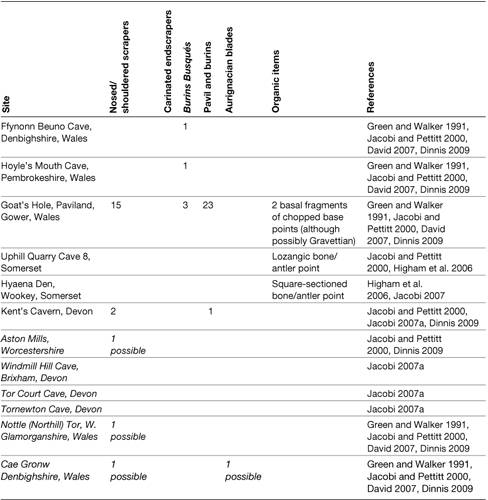

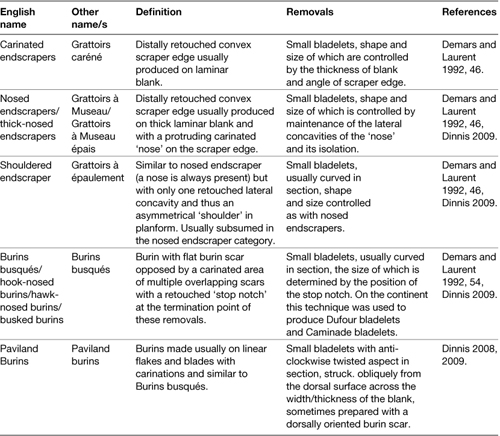

The British Aurignacian is defined on the basis of the presence of carinated/nosed/shouldered endscrapers, burins busqués and related variants and bone/antler sagaies (Campbell 1977, Jacobi 1999, 2007a; David 2007; Dinnis 2005; 2008, 2009; Pettitt 2008; Jacobi and Higham 2011). It seems that artefacts formally defined as carinated endscrapers and scrapers functioned primarily as cores for the production of small bladelets which were often subsequently retouched into tool forms such as the dufour bladelet (Chiotti 2003; Le Brun-Ricalens 2005). The production of these bladelet forms was clearly complex, aimed at highly specific forms which presumably formed parts of well-designed, multi-component tool and weapon systems. As Dinnis (2008, 19) has noted, the specific morphology of nosed endscrapers (grattoirs à museau), on which the ‘nose’ is a protrusion of the ventral surface and served as a platform for bladelet removal in a similar manner to larger blade cores, reveals a concern with standardisation of bladelet removals. One of the most diagnostic lithic forms of the Aurignacian is the burin busqué.1 These bear a flat burin scar which functioned as the platform for the removal of a series of regular bladelets, the length of which has been determined by a terminal ‘stop-notch’ which served to terminate the removal. It is this latter character that distinguishes burins busqués from other nosed endscrapers, although their reduction is otherwise broadly similar (Dinnis 2008). Burins busqués are known from Paviland (see Text Box 7.4), Ffynnon Beuno and Hoyle’s Mouth in Wales, revealing that although bladelets have understandably not survived from these early excavations they were produced as part of the quotidian activities of Aurignacians in Britain.

The earliest Aurignacian in northern Europe is poorly dated. The oldest reliable radiocarbon measurements for a handful of sites indicate that it had arrived in northern Germany somewhere between ~40 and 38 ka BP and in Poland and Belgium by ~41 ka BP, persisting until ~32 ka BP in these regions (Flas 2008). It is no surprise that the few reliable radiocarbon measurements for British Aurignacian sites fall at the younger end of this range, parsimoniously reflecting a gradual north-west dispersal of Aurignacian groups (see below). Assemblages in Northern France possess blade and bladelet production including dufour bladelets, carinated endscrapers and Aurignacian blades, dihedral and truncation burins.

Aurignacian chronology and relationship with the LRJ

At least six British cave sites have yielded demonstrably Aurignacian material and a further six may include a very small number of Aurignacian artefacts although some are ambiguous (Table 7.2). Assuming these represent the earliest arrivals of Homo sapiens in Britain (see Jacobi and Pettitt 2000; Jacobi et al. 2006; Jacobi 2007a; Pettitt 2008; Dinnis 2009) there seems to be no chronometric overlap between these and the makers of the LRJ. It now seems fairly clear that Aurignacian implements were not part of LRJ assemblages as was suggested for example by McBurney (1965, 26–9); they are usually found fairly exclusively (Jacobi 1999, 38) and, even at sites where LRJ leafpoints and diagnostic Aurignacian artefacts are both present, the two are usually distinguishable on the basis of condition if not stratigraphy (Jacobi 2007a, 299; Swainston 2000, 100) and, at Kent’s Cavern at least, on the basis of exclusive distribution (Garrod 1926, 44–5; Jacobi 2007a). Furthermore, the restriction of the Aurignacian to the south-west and the wider distribution of LRJ assemblages is best interpreted as distinct chrono-cultural territories rather than activity facies (Pettitt 2008).

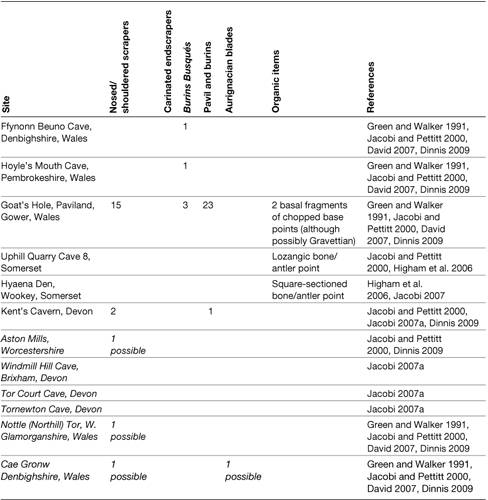

Table 7.2 British sites with Aurignacian material (possible Aurignacian material in italics). Data from Jacobi 1980, 1999; Swainston 1999, 2000; Jacobi and Pettitt 2000; Dinnis 2005, 2008, 2009. Where details are discrepant we follow the figures of Dinnis 2009.

The presence of burins busqués and nosed carinated endscrapers in British Aurignacian sites has been seen by several specialists as indicating a recent Aurignacien Evolué rather than earlier Aurignacien Ancien attribution (e.g. Jacobi 1980; Jacobi and Pettitt 2000; Swainston 2000; Dinnis 2009). Such a late attribution is in keeping with the known chronology for the spread of the Aurignacian in Europe generally (e.g. papers in Zilhão and d’Errico 2003) and for the two absolute dates for British Aurignacian material. A direct AMS radiocarbon date on a lozangic bone/antler point from Uphill Quarry Cave 8 (Somerset) indicates an age of ~35–36 ka BP (OxA-13716, 31,730 ± 250 BP, Jacobi et al. 2006). This is typologically similar to points from continental Aurignacian II (or Aurignacien Evolué) assemblages with similar ages and the age is further supported by a direct date on a typologically undiagnostic bone/antler point from the Hyaena Den of 31,550 ± 340 BP (OxA-13803, Jacobi et al. 2006), that is, statistically the same calibrated age range. While these are the only two dates currently existing for the British Aurignacian they are at least consistent and suggest an age of ~34–35 ka BP for the appearance of modern humans in the country. Thus, even assuming the LRJ dates to be as young as ~42 ka BP, and the Aurignacian to as early as ~34 ka BP, there seems on current evidence to have been a gap of perhaps 8,000 years between the two. Although the database is far too poor to allow statements of any confidence we hypothesise, therefore, that contemporaneity, contact and interaction between Neanderthals and modern humans did not occur in Britain; when modern humans dispersed into the country they did so into a landscape devoid of other human predators. With a small and poorly dated set of Aurignacian sites in Britain it is, however, impossible to establish the duration of this pioneer dispersal. Jacobi and Pettitt (2000) drew attention to the geographically restricted range of known assemblages and the similarity of their inventories, suggesting that in all probability they represent a very brief time range, and Dinnis (2008) suggested that this may have been restricted to Greenland Interstadial 7. It is possible that Aurignacian activity in Britain was, in reality, restricted to a single group, perhaps even during only one seasonal visit, although of course this is impossible to establish. There is, however, certainly no reason to assume long-term or even year-round occupation.

AURIGNACIAN SITES AND ASSEMBLAGES

The most stringent identifications of British Aurignacian material are those of Jacobi and Pettitt (2000) and particularly Dinnis (2009), both of which employ strict criteria to identify only typologically diagnostic artefacts. As such they may underestimate the actual amount of known Aurignacian material, although probably only to a very minor extent, as much British Upper Palaeolithic material is typologically LUP as will be seen in Chapter 8. It cannot be ruled out, for example, that some débitage from discoidal reduction from Paviland is of Aurignacian age; although it is generally assumed to be of Middle Palaeolithic age, it can be found in well-stratified Aurignacian assemblages on the continent such as at Abri Pataud and Lommersum (Dinnis 2009, 169). In Britain, however, contextualised examples of discoidal technology are Middle Palaeolithic, as seen in Chapter 6 and, given the very low numbers of EUP artefacts in Britain in general, however, a parsimonious approach seems sensible. Of the six to twelve sites which have yielded Aurignacian material it is noticeable that these belong to a tight geographical area in the south-west, with groups in Devon, Somerset and south Wales (Table 7.2 and Figure 7.9). Those clearly attributable to the Aurignacian include carinated endscrapers, often of nosed or shouldered form, and burins busqués as noted above. Formally diagnostic Aurignacian artefacts are remarkably limited in number; the stringent analysis by Dinnis (2009) identified only 49 artefacts as clearly diagnostic markers of the Aurignacian.

FIGURE 7.9

Distribution of British sites/findspots classified as Aurignacian.

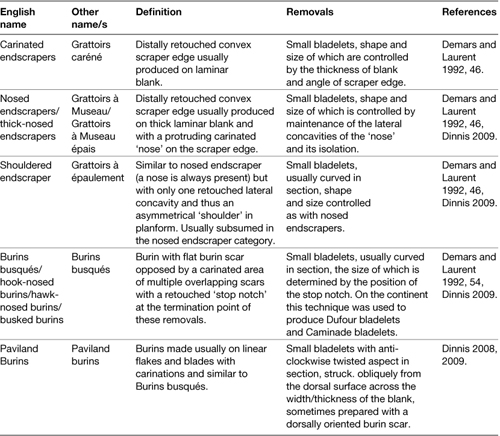

Rather than finished tools, it seems that a number of Aurignacian ‘endscraper’ and ‘burin’ forms are actually cores from which small bladelets have been removed, their differing morphologies relating to how the size and shape of resulting bladelets has been determined. On the continent these generally belong to the Aurignacien Evolué. They are summarised in Table 7.3.

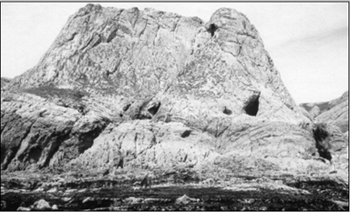

Only the Goat’s Hole at Paviland contained what may be referred to as an Aurignacian assemblage, although even this is remarkably small. Campbell (1977, 144–5) implied that several dozen artefacts from the cave are Aurignacian, although Dinnis (2009, 172) has noted that his overly broad typological classification resulted in this ‘entirely erroneous’ number; Swainston (2000, 100–101) identified only 55, and Dinnis (2009, 173) arrived at a similar count of 49. The raw materials represented by the diagnostic artefacts suggest procurement to the west (Pembrokeshire), locally, and possibly to the south-east (Somerset; see below). The diagnostic artefacts are dominated by ‘Paviland Burins’ (23; see below) and followed by carinated burins (8), thick-nosed endscrapers (8) and flat-nosed endscrapers (7) with three burins busqués.

Table 7.3 Diagnostic Aurignacian endscraper and burin forms (bladelet cores) represented in Britain and on the continent.

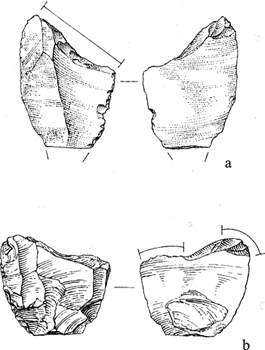

Swainston (1999, 50; 2000, 109–11) drew attention to the idiosyncratic retouch used to create ‘shouldered (nosed) endscrapers’ at the site. Breuil had first identified these and defined them as a ‘rostrate [beak-like] grattoir [endscraper] with inverse terminal retouches’ (Sollas 1913, 344). These are fairly standardised in form and bear four to six diagonal retouch facets (bladelet removals) on the ventral surface (Figure 7.10). Swainston noted that this idiosyncratic type of retouch occurred additionally on an endscraper on a blade and acted as the platform for burin spall removal in at least two cases, the similarity suggesting that the assemblage derived from only a single occupation. Dinnis (2008, 26–8) noted the general similarity of these forms with burins busqués although he has demonstrated that they are distinct technological forms due to consistent technological differences. He classified them as ‘Paviland Burins’, noting that they may represent the final stages of more standardised burins busqué reduction or a completely independent reduction sequence.

FIGURE 7.10

Aurignacian shouldered endscrapers from Paviland. (From Swainston 1999, 2000 and courtesy Steph Swainston.)

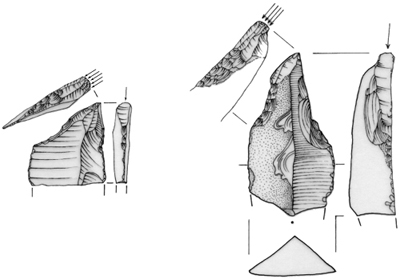

To the west of Paviland, the small cave of Hoyle’s Mouth near Tenby in south-west Wales has yielded a single burin busqué in a lithic assemblage otherwise Late Glacial in character (David 2007, 12; Figure 7.11). As Dinnis (2009, 183) has noted, the presence of hyaena and woolly rhinoceros indicate the presence of Mid Devensian deposits in the cave and thus this identification is not surprising, although clearly one is dealing with a very brief occupation, possibly the result of a westward search for raw materials from the Gower area. The burin busqué is made on high-quality flint possibly from a source in the now-submerged Bristol Channel (David 1991, 148); if correct this supports the notion of a link to the east.

In north Wales, two caves with Upper Palaeolithic archaeology are found next to each other in the Vale of Clwyd; Ffynnon Beuno and Cae Gwyn. Ffynnon Beuno contained the larger assemblage of the two and its small amount of Early Upper Palaeolithic archaeology includes a leafpoint and a burin busqué (David 2007, 8; Figure 7.11), the latter on high-quality flint from a relatively large nodule (Dinnis 2009, 185). At Cae Gwyn the number of artefacts is much smaller. Two objects from the cave have been seen by some as Early Upper Palaeolithic – a blade and endscraper on blade with ‘Aurignacian-like’ retouch (Green and Walker 1991, 51) – although these are not particularly diagnostic and could be Late Glacial in age.

Kent’s Cavern contained a small number of Aurignacian artefacts and, although their actual number is open to question, there is no reason to believe that they represent anything other than a brief occupation. Campbell (1977, 142) grouped these with LRJ material, suggesting that the overall count for EUP artefacts from the cave was 112, although this is certainly an over-estimation. Jacobi (2007a, Figure 60) plotted 10 artefacts as Aurignacian on the cave’s plan, yet Dinnis (2009, 188) recognised only three apparently diagnostic artefacts – a Paviland Burin and two flat-nosed endscrapers and has subsequently noted the presence of a carinated burin (pers. comm. to PP). At present the source of the flint used for these is unknown. The distribution of diagnostic Aurignacian artefacts in Kent’s Cavern is apparently restricted to the eastern (downslope) end of the Vestibule and to the adjacent areas of the Passage of Urns and the northern end of The Great Chamber (Jacobi 2007a).

FIGURE 7.11

Burins busqué from the Welsh Aurignacian. Left: Hoyle’s Mouth; right: Ffynnon Beuno. (Illustration courtesy Andrew David.)

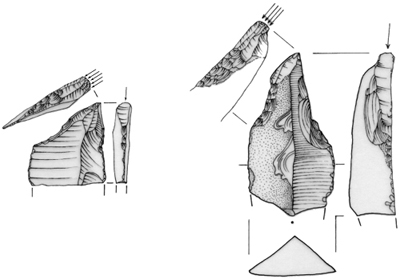

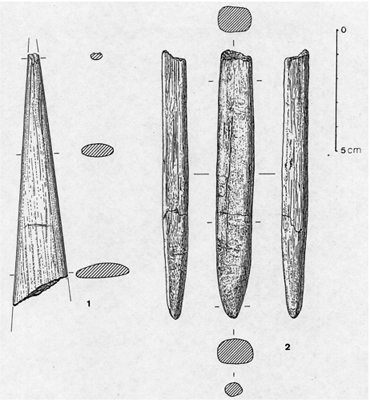

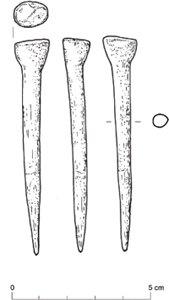

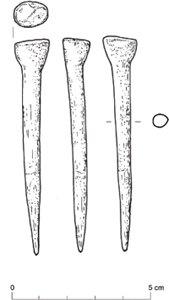

As noted above, two organic armatures are referrable to the British Aurignacian (Figure 7.12). Although no diagnostic lithics were recovered from Uphill Quarry Cave 8 just outside of Weston-super-Mare (Somerset), a broken lozangic bone/antler point of similar typological form to those from Aurignacian II/Aurignacien Evolué assemblages on the continent has a direct AMS radiocarbon measurement of 31,730 ± 250 BP (OxA-13716, Higham et al. 2006). A bone/antler point recovered from the South Passage of the Hyaena Den at Wookey (Somerset) – like Uphill associated with the Axe river – also bears similarities to those from continental Aurignacian sites and has been dated to 31,550 ± 340 (OxA-13803, Higham et al. 2006) but otherwise the cave contained no identifiable Aurignacian artefacts. Both of these indicate calendrical ages of ~35–36 ka BP. Two basal fragments of chopped-base bone points from Paviland may also be Aurignacian but could equally be Gravettian or late glacial in derivation.

FIGURE 7.12

Organic points from Aurignacian contexts in Somerset. Left: Uphill Quarry; right: Hyaena Den. (From Pettitt 2008 and courtesy Roger and Jacobi.)

In addition to the sites with demonstrable Aurignacian material, several caves have yielded artefacts which may be Aurignacian but which are ambiguous. The number of potential Aurignacian artefacts from such sites is so low that, whether or not they are accepted as Aurignacian, does not change the overall picture of very brief settlement in the south-west. The small fissure (now destroyed) of Nottle Tor on the north part of the Gower peninsula yielded a possible shouldered endscraper which was accepted as Aurignacian by Jacobi and Pettitt (2000, 316) but, as Dinnis (2009, 186) has rightly pointed out, this remains open to question. Similar doubt surrounds the possible flat-nosed endscraper from the terrace deposits of the Carrant Brook in Worcestershire at Aston Mill. The site has yielded a number of MIS3 fauna although, as Dinnis (2009, 185–6) notes, the issue is open. Jacobi (2007a, 298) has suggested that the shared presence of flint available in the vicinity of Kent’s Cavern in Tornewton Cave, Tor Court Cave and Windmill Hill Cave in Devon suggests that this material is also attributable to the Aurignacian. No diagnostic artefacts from these additional sites have yet been reported, however, and in view of this such an attribution seems provisional (Dinnis 2009, 85). It is worth noting that Late Upper Palaeolithic artefacts are known from Tornewton and Windmill Hill caves at least and that one cannot therefore rule out a shared Late Upper Palaeolithic raw material source.

Aurignacian settlement

The British Aurignacian record could not contrast more with the larger assemblages of the continental Aurignacien Evolué, with their large and varied lithic and organic inventories, deep stratigraphies and regional traditions of rock art and art mobilier. Typologically and chronologically, however, it is understandable as a brief northwestwards dispersal of an Aurignacien Evolué group, carrying with it the technological connaisance and savoire-faire of the lithic and organic technologies of the time. The remarkably low number of British artefacts attributable to the Aurignacian is striking and must reflect at best ephemeral occupation of the northwestern edge of the Aurignacian range. Even assuming that undiagnostic débitage belonging to the Aurignacian has not been recognised and that in the early history of cave investigation in Britain such artefacts have gone unnoticed, the extremely small size of British Aurignacian assemblages is of note. Aurignacian assemblages from the closest regions of continental Europe vary in size, from those which more closely approximate the Paviland assemblage (~30–50 pieces, such as Des Agneux, Côtes-d’Armor, France), to those containing ~100–200 artefacts (e.g. Wildscheuer cave in Hesse and Ilsenhöhle at Ranis), more typical assemblages containing ~400–500 artefacts (e.g. La Pièce de Coinville in the valley of the Orne, northern France), those with up to ≥1,500 artefacts (e.g. Épouville-la-Briquetterie Dupray in Normandy and Herbeville, Yvelines) and even those with ≥5,000 (at Breitenbach in Thuringia) (Gouédo 1996; Flas 2008). The other striking pattern is the total lack of open air findspots in Britain (with the possible exception of one artefact at Aston Mills). Given the predominance of diagnostically Aurignacian artefacts in the caves from which one can identify material, and given that open air findspots are known for the Gravettian (see below) and Late Upper Palaeolithic (see Chapter 8) this cannot, we suggest, be explained by recovery bias. One imagines a chronologically discrete and geographically restricted dispersal to south-west Britain perhaps by one small Aurignacian group. The specific reason for such a modest and probably very brief Aurignacian presence in Britain is unknown. On the basis of the mammoth ivory artefacts from the Goat’s Hole, Paviland, Dennell (1983, 132–3) suggested that it may reflect deliberate sourcing of mammoth ivory, although it is now fairly clear that the worked ivory from this site is of Gravettian context, and thus does not pertain to the Aurignacian, and no artefacts of this material are known for the period.

The similarities of the British material to the continental Aurignacian II/Aurignacien Evolué, lack of evidence of any typological subdivisions within the British material, and the clustering of the known sites in the western uplands of Britain (Jacobi 1999; Jacobi and Pettitt 2000), adds support to the notion that Britain was visited only by one or a small number of groups. Broad typological similarities suggest potential sources for such a dispersal to the south (e.g. south-west France) and east (e.g. Belgium; see discussion in Dinnis 2009). ‘Paviland Burins’ (sensu Dinnis 2008) for example are known at Spy and Trou Magritte in Belgium and Le Piage in south-west France (ibid.). Aldhouse-Green (2004, 16) suggested that the source of the British Aurignacian was the ‘classic’ region of south-west France and Pettitt (2008) argued that the distribution of sites in Britain may reflect the importance of the Atlantic coast in the northwards dispersal of an Aurignacian group into Britain, arguing that a parsimonious dispersal would be to follow the Atlantic coastline of the time, along the rugged landscapes of northwestern France into similar landscapes from the west of Cornwall onto the plains of what is now the Bristol Channel and the Severn Valley. This remains plausible and would explain the lack of Aurignacian findspots further east in lowland England. It should be remembered, however, that a major part of Aurignacian territory in north-west Europe could now be submerged, that is, the vast valleys of the Channel River (R. Dinnis pers. comm.). If a westward dispersal occurred along this route there is no reason why finds should be recovered from lowland England.

Whatever the specific direction of dispersal into Britain Aurignacian settlement clearly focussed on the south-west, and if numbers of sites with known archaeology of the period and numbers of artefacts are at all indicators then possibly south Wales was the main focus, the plains of the Severn River/Bristol Channel and its tributaries such as the Axe channelling the movement of herbivorous prey. Upland plateaux on south Gower such as above the Goat’s Hole at Paviland and at Uphill could have provided excellent vantages for monitoring prey, as would the plateau above the Hyaena Den at Wookey for observing movements along the Axe Valley.

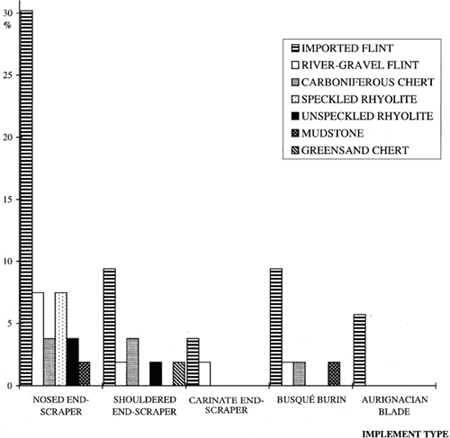

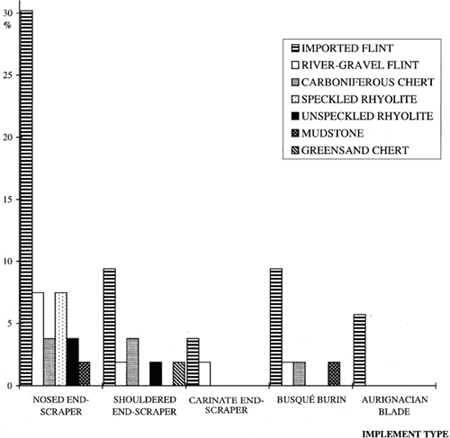

Lithic raw materials support the notion of connectedness between the known British Aurignacian sites. Swainston (2000, 104–5) noted that imported flint dominates the small Aurignacian assemblage from the Goat’s Hole, Paviland (Figure 7.13). It is certain that the Goat’s Hole contains the most varied raw material types of all known British Aurignacian sites (Dinnis 2009, 181). To an extent this may be a factor of the remarkably low number of artefacts from all other sites although this supports the notion that if there was any ‘centre’ of settlement for the brief Aurignacian occupation of Britain it was the Gower region. The Aurignacian blades identified from the site are on flint, as are the burins busqués, suggesting, perhaps, that deliberate lithic gearing-up occurred in Pembrokeshire. By contrast the presence of artefacts of Greensand chert – used for example for a shouldered endscraper – suggests a source in Somerset.

FIGURE 7.13

Representation of raw material types among the Aurignacian lithics from Paviland. (From Swainston 2000 and courtesy Steph Swainston.)

It could be said that all known Aurignacian material in Britain relates to armature use and manufacture, that is, the two known sagaies from the Axe River and the various ‘burins’ and ‘endscrapers’ that were presumably the source for armature-mounted bladelets which early excavations failed to recover. In this sense the whole Aurignacian record of Britain looks like a relatively brief hunting episode in which an Aurignacian group dispersed along the Channel River system or Atlantic coast, inserted themselves tactically into a readily understandable landscape in which rivers channelled herbivores in predictable ways, plateaux were available for monitoring such prey, caves presented shelter and gearing-up was practised at flint and chert sources within and on the periphery of the temporary range. The small nature of the artefact collections at all sites within the range suggest small-scale but highly mobile residential mobility, as noted above, probably during a very brief stay.

THE BRITISH MID UPPER PALAEOLITHIC: GRAVETTIAN LIFE AND DEATH