The Good, the Bad, and the Oily

If there is one thing that we in the global north know how to do, it is to consume. The product-packed shelves that line the aisles of stores and the seemingly infinite options brought to us through online shopping can leave us feeling overwhelmed by choice. A Los Angeles Times report suggested that the average American household contains roughly 300,000 items.1 While we do not encourage anyone to start counting them, there is no denying that even those living “minimalist” lifestyles in wealthier countries are likely to own thousands of products, from clothes to electronics to furniture to medicine.

In general, the flow of goods in our current economic model can be described as a linear process: products are manufactured (often from multiple other chemicals and products), packaged, distributed, purchased, consumed, and ultimately disposed. Introducing recycling to the process can, at least to some extent, transform the linear economy into one that is circular; that is, instead of the product ending up in a landfill, some materials might be recovered and reused to begin the cycle anew.

The consumer economy viewed from the perspective of a chemist or a chemical engineer, however, might look a little different. Rather than conceive the flow of raw materials through to consumer products as linear or circular, a scientist or engineer might imagine a tree, as shown in figure 1. In this analogy the roots represent the most basic raw materials available to us, such as plants, minerals, water, and air. Moving up the trunk to the crown, we reach the tree’s largest branches. These correspond to the set of basic products that can be made from the raw materials. Smaller branches shoot off from these larger ones, and even smaller branches from those, eventually yielding twigs with leaves. The point is that the most basic raw materials, when taken in combination, can form a larger set of products, which in turn can be used to create an even larger set. The process continues to the point where we are able to create all the complex products and consumer goods available today. The tree analogy especially makes sense when one considers that as many as 100,000 chemicals and consumer products derive from a mere few hundred chemicals and that these intermediate chemicals are made from roughly twenty basic chemicals, which in turn come from the base natural resources – gas, coal, oil, minerals, water, and air.

Figure 1. The chemical tree in which raw materials, such as minerals, wood, water, and fossil resources, are located at the roots, and the consumer products that they form make up the tree’s leaves.

Unlike consumer goods such as cars and clothes, most of the materials and chemicals located in the pathway between the root raw materials and the final consumer products are mainly invisible to the average consumer. Taking the example of seemingly simple adhesive tape, if we were to work our way down the tree of chemicals, starting from the roll of tape, to the root resources, we would easily encounter several dozen chemicals and materials along the way. The adhesive used to make the sticky side of the tape is composed of an acrylate polymer, which itself derives from a type of acrylate monomer, which in turn is made by reacting acrylic acid with an alcohol. Acrylic acid is made using propylene, a by-product of gasoline production, meaning that both the acid and the alcohol originate from crude oil. The non-sticky backing of the tape is made from cellulose acetate, which itself comes from acetic acid and cellulose, the latter of which is obtained from the fibers in wood or cotton. To allow the tape to be wound and unwound, the backing is often treated with a release coating, such as fluorosilicone, a synthetic rubber made from petroleum products. Finally, the backing and adhesive are stuck together using a styrene acrylic or a polyurethane, both of which can be made from a wide range of chemicals; most of these chemicals start from oil-derived products such as propylene, ethylene, and ammonia. All this, however, does not even include the chemicals, materials, and water that enable the many manufacturing processes, or all those that go into making the plastic dispenser and packaging. Clearly there is more to a simple everyday roll of adhesive tape than meets the consumer’s eye.

You might have been surprised to find that crude oil – a fossil fuel – is a raw material used in the making of adhesive tape. For many of us, putting fuel in our cars might appear as our most direct contact with the fossil industry; however, the truth is that we live in a veritable fossil-fuel economy in which the majority of consumer products – for example, aspirin, rubber, paint, plastics, and fertilizer – derive from chemicals that themselves derive from fossil products. The point is that if we are to break free completely from our reliance on fossil resources, without compromising the manufacturing of essential consumer goods, we need to find alternative ways of making that set of basic chemicals located near the bottom of the chemical tree.

Do substitutes for these chemical processes even exist? The answer is surprising. As it turns out, there is plenty of potential for CO2, arguably an abundant natural carbon resource, to replace fossil products in the manufacturing of many key chemicals. Although you may be skeptical, we encourage you to keep an open but critical mind as we take you through this journey of the CO2 molecule, from its creation at the beginning of the universe to its movement throughout the earth’s carbon cycle to its role in inducing global warming and finally to its potential to help decarbonize our industries, reduce dependence on fossil resources, and ultimately mitigate the impacts of climate change. First, however, the following is some background into our emissions crisis.

It Is All Up in the Air

Le Bourget is a small municipality located in the northeastern suburbs of Paris. It was here, in December of 2015, that all 196 members of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change agreed to adopt the first universal, legally binding, climate-change deal, better known as the Paris Agreement. It opened for signature on April 22, 2016, in honor of Earth Day, and officially came into effect in November of the same year, one month after fifty-five members, who accounted for at least 55 percent of global emissions, had ratified the agreement. The document outlines goals and strategies to strengthen the global response to climate change, the most fundamental of which is to keep global temperature rise well below 2°C, with an aspiration of 1.5°C.

Global temperature rise is directly related to the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere, as we shall explain in greater detail in chapter 2. Much like how a doctor measures blood pressure to gauge a patient’s overall health, measuring CO2 concentrations is a key tool in monitoring the health of the planet. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) of the United States has been recording atmospheric carbon dioxide levels over the past fifty years. These data, recorded in parts per million (ppm), have been presented in the form of the well-documented Charles Keeling Curve, shown in figure 2.

Figure 2. Keeling Curve, showing atmospheric carbon dioxide, in parts per million, from the years 1700 to 2020.

The overall trend shows a continuous increase in atmospheric CO2 concentrations over the last fifty years, from 315 ppm in 1958 to 408 ppm in 2020. The periodically spaced black wiggles superimposed onto the curve correspond to the annual rise and fall of CO2 concentrations in accordance with seasonal plant growth and decay.

The continuous rise in atmospheric CO2 levels has been connected to the use of fossil fuels since the beginning of the industrial revolution. Frighteningly, over half of the total amount of greenhouse gases emitted since the end of the eighteenth century occurred during the past thirty years, due to the accelerated extraction and use of fossil fuels.4 While we could easily fill pages presenting the overwhelming scientific evidence of the rapid, human-induced global warming, many excellent books have already been written on the topic.

Every year the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) releases a report on the status of the global climate. To date it has declared the past five years (2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019) to be the warmest on record,* with 2016 being the warmest of them all at 1.1°C above pre-industrial times.5 This has been accompanied by consistently rising levels of atmospheric CO2, dramatic drops in Arctic sea ice, and a major rise in global sea levels each year. In 2018 the global temperature of the ocean reached the highest on record, contributing to coral bleaching and mortality in tropical waters.6 Rising temperatures are also having detrimental effects on glaciers, with up to one-third of the Himalayan range, which currently serves as a water source to over a billion and a half people, expected to melt by 2100.7 Multiple catastrophic weather events include record-breaking hurricanes in the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, over forty million people displaced by flooding in the Indian subcontinent, severe drought in East Africa, and bush fires in Australia.5,8,9 Although the term climate refugee is not yet recognized under international law, the extreme weather and increased frequency of natural disasters caused by climate change is forcibly displacing millions of people from their communities. Conflict resulting from climate-related food-and-water insecurity further exacerbates the human toll of climate change. Although it is difficult to estimate the exact numbers, the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre reported 18.8 million new disaster-related internal displacements in 2017, with floods and storms being the biggest trigger.10

According to the Global Energy and CO2 Status Report 2019 of the International Energy Agency (IEA), annual global energy-related CO2 emissions grew by 1.7 percent in 2018, reaching a historic high of 33.1 gigatonnes (Gt)* – that is over 33 billion tonnes in a single year.11 To help us grasp this reality, figure 3 shows a picture of a ten-meter-diameter sphere of CO2, weighing one tonne, in relation to a London double-decker bus. This illustration gives meaning to one tonne of CO2 in the form of volume under ambient temperature and pressure conditions.†

Figure 3. Volume equivalent of one tonne of CO2 in relation to the size of a London double-decker bus.

Illustration courtesy of Dr. Chenxi Qian.

Imagine 33 billion of these one-tonne CO2 spheres being injected into our atmosphere every year from the combustion of fossil fuel. This is equivalent to putting one thousand of these CO2-filled balloons into the atmosphere every second. To evade action on climate change is no longer a choice but a failure to adapt to reality, with serious environmental, social, and economic implications.

The two main strategies in the Paris Agreement to combat climate change involve mitigating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and reducing fossil fuel consumption. So how are we doing when it comes to curbing our emissions to meet our goals?

Each year for the past decade an international team of leading scientists has put forth the UN Environment Emissions Gap Report to assess the world’s progress in meeting the Paris Agreement goals of holding global temperature to well below 2°C. It evaluates the level of implementation of member countries’ emission-reductions pledges with regard to current emission trends to create an “interim report card” of our efforts so far.

The findings of these reports have been discomforting. The national pledges at the foundation of the Paris Agreement are expected to cover only one-third of the emissions reductions necessary to remain on track toward the goal of staying well below 2°C by 2100.13 At this point, if all countries follow through completely with both their conditional and their unconditional emission-reduction promises, we could still face a 3°C rise in global temperature by the end of the century. Countries will need to go above and beyond their initial pledges if we are to have a chance at keeping warming well below 2°C. To make matters worse, many countries are already failing to meet their originally proposed pledges for 2020. New policies and swifter action will be necessary for many member states, especially given that the ambiguity of some of the proposed nationally determined contributions caused uncertainty in the emissions originally estimated for 2030.14

The New Climate Economy: The 2018 Report of the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate warns that the next ten to fifteen years present a critical “use it or lose it” opportunity, emphasizing in particular that the next two to three years constitute a critical window.15 At this point there is considerable uncertainty as to whether the energy transition from fossil fuels to renewables, and the concomitant reduction in CO2 emissions, will be fast enough, especially given the current fossil fuel outlook and lagging political action.16 In November 2018 the WMO announced that global temperatures were on course for a rise of 3°C to 5°C this century, far overshooting the global target of limiting their increase to 2°C. This is particularly alarming given that economic transitions have historically occurred over the span of decades.17 Clearly we need to act quickly to get the world on track to meet the emission targets. But what are these targets exactly, how do they relate to global temperature rise, and where does the challenge lie in reducing them?

As previously mentioned, global temperature rise is directly related to the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere. Scientists can therefore estimate the “carbon budget” that ensures a decent chance at limiting global temperature rise to a given level. Global Warming of 1.5°C, the 2018 report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), states that keeping our cumulative CO2 emissions to no more than 420 Gt (that is, 420 × 109 tonnes) of CO2 will result in a 66 percent chance of global temperature rising to no more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

What exactly do we mean by cumulative emissions? These are the total CO2 emissions that are added to the atmosphere over a certain time. As we shall see in chapter 2, this number is actually different than the amount we send into the atmosphere, because nearly half of emissions are taken up by the ocean and terrestrial biospheres. The IPCC’s report considers cumulative emissions as those starting in 2018. At present we emit roughly 33 Gt of CO2 into the atmosphere annually, and this number continues to grow every year. From 2010 to 2014, for example, emissions increased at an unprecedented annual rate of 2.75 percent. So, to cap our total cumulative emissions at 420 Gt, it is not enough to simply reduce our annual emissions to a steady rate; we need to emit fewer and fewer emissions every year until we eventually reach zero annual emissions. Recent climate reports from the IPCC, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and the Royal Society, all state that ceasing emissions entirely might not be enough and that removing CO2 from the atmosphere will be necessary to prevent a dangerous rise in global temperature.

How fast exactly do these reductions need to happen? If we overshoot our target, will we still be able to reduce global temperatures? The 2018 IPCC report suggests that CO2 emissions should peak to no more than 30 Gt per year by 2030, then start to decline, ideally reaching zero emissions by 2050. While these recommendations are based on climate models, which are inherently subject to assumptions and uncertainties, one thing remains clear: the faster we reduce our annual emissions to zero the better chance we have of restricting global temperature rise.

Trends in Global Emissions

Before diving into the ways in which we can cut our GHG emissions, we begin by identifying the derivations of the emissions. Our planet’s total GHG emissions can be broken down in many ways: by country or region, by person, by source, and so forth. One particularly useful approach is to break down emissions according to the following sectors: energy, industry, transportation, buildings, and land use.

Breaking down emissions according to each of these five sectors, however, is not simple. For example, buildings account for nearly 20 percent of all GHG emissions, but this is in large part due to buildings consuming large amounts of heat and electricity (via lighting, ventilation systems, heating, and air-conditioning, for example). In fact, over half the emissions from buildings are indirect, associated with the production of energy in the form of heat and electricity. So, although these emissions appear to come from buildings themselves, they ultimately derive from the energy sector.

From this example, one can quickly appreciate why it is important to identify the scope of these sectors. For the purpose of discussing decarbonization strategies, we will stick to breaking emissions down according to their sector of origin. For example, the production of energy worldwide is responsible for nearly 35 percent of all GHG emissions.* Although much of this energy is eventually used by other sectors (mainly buildings and industrial processes), these emissions result from the production of the energy itself, and therefore we will attribute them to the energy sector.

Decarbonization: the elimination of greenhouse gas emissions, specifically carbon dioxide, from a technology, process, or system.

The fact that most of our GHG emissions derive from energy production should come as no surprise given that most of our energy, be it heat or electricity, comes from burning oil, natural gas, and coal. While heat and electricity production account for over two-thirds of these emissions, the remaining third comes from other auxiliary processes in the energy supply chain, such as fuel extraction, refining, and processing.

We tend to refer to oil, natural gas, and coal together as simply fossil fuels. While this is accurate in that all three derive from fossil resources, it is worth noting that they are not equal in terms of their emissions. Coal-fired power plants were the single largest contributor to the growth in emissions in 2018, with coal-fired electricity generation accounting for nearly one-third of total CO2 emissions. In fact, a recent assessment conducted by the IEA found burning coal to be the single largest source of global temperature rise.18 In certain instances, switching from coal to natural gas, a less carbon- intensive fossil fuel, has the potential to reduce the energy sector’s emissions. For example, switching from coal to natural gas in 2018 alone helped to avoid 40 megatonnes (Mt) and 45 Mt of CO2 emissions in the United States and China, respectively.18 We emphasize, however, that substituting natural gas for coal does not necessarily offer a sustainable solution to the mitigation of emissions, and the overall carbon footprint of natural gas depends on the nature of its extraction. For example, obtaining natural gas contained within shale formations requires hydraulic fracturing technology to enable a process otherwise known as fracking. This involves drilling deep underground to access the shale formation and then pumping high-pressure fluid to crack the rock, thereby releasing any gas trapped within. One study found that when methane emissions are included, the greenhouse-gas footprint of shale gas is larger than that of conventional oil, natural gas, and coal.19 So, while it might be tempting to view natural gas as the “cleaner” fossil-based energy source, the true environmental impact of any one fossil-fuel project depends on the specifics of its extraction and refinement processes. Although coal use is decreasing worldwide, its decline is being outpaced by increased consumption of oil and natural gas, which are now the principal drivers of growth in carbon dioxide emissions.20 Be it coal, natural gas, or oil, burning fossil fuels is the main cause of climate change.

It may come as a surprise that some of the largest contributors of emissions, after energy, are agriculture, forestry, and land use. These sectors generally consist of all human activity involving land changes. Unlike the energy sector’s emissions that derive from the burning of fossil fuels, the emissions associated with land-use change often result from alterations to natural carbon sinks. For example, the removal of natural forests to expand agricultural lands contributes 6 Gt of CO2 emissions every year. Deforestation in the tropics, for example, accounts for over 4 Gt of CO2 emissions alone.21 This sector also includes many of the emissions that arise from our global food-supply chain. You may have heard that going vegetarian is one of the most impactful measures you can take to reduce your individual carbon footprint. Indeed, at 7.1 Gt CO2-equivalent per year, livestock contribute more GHG emissions than any other food source, and cattle alone account for two-thirds of these.22

There are many promising strategies to reduce emissions associated with agriculture, forestry, and land use. Many of these simply involve implementing more sustainable management practices, rather than completely overhauling the infrastructure. For example, integrating trees and shrubs into fields dedicated to crops and livestock, a practice known as agroforestry, can help prevent erosion, enhance soil properties, improve water infiltration, and ultimately increase the carbon- storage capacity of the land through photosynthesis. Similarly, other land-management strategies have the potential to ameliorate the land’s carbon- sequestration capacity. Conservation, restoration, and improved land-management strategies have the potential to mitigate up to 23 Gt of emissions per year.23

Agroforestry: the practice of growing trees and/or other perennial plants alongside crops and/or livestock.

Technological strategies also exist to address emissions associated with agriculture, forestry, and land use. Advances in molecular biology are creating opportunities to restore and enhance the carbon uptake of land and to adapt crops to changing climates. Genome modification, for example, can help both to enhance the health and yield of crops and to make plant varieties that may thrive under warmer temperatures. Other strategies, such as vertical farming, in which crops are grown on inclined surfaces or integrated into other structures, can minimize the amount of land dedicated to agriculture. Incorporating trees and plants into urban landscapes presents another opportunity to enhance the carbon-sequestration of land. The award-winning Bosco Verticale (Vertical Forest), a pair of residential towers in Milan that boasts hundreds of trees and tens of thousands of different plants and shrubs on its facades, removes upwards of thirty tonnes of CO2 every year. Greening buildings not only constitutes a feasible and effective strategy for capturing carbon but also can help regulate building temperature, promote local biodiversity, and clean the air – not to mention being an aesthetic addition to the urban landscape. For example, PhotoSynthetica, a United Kingdom–based company, provides a variety of building cladding solutions that capture CO2 from air, using algae. Its technology enhances the sequestration capacity of vertical areas by maximizing the interaction of the air flow with the algae-containing cladding, resulting in the removal of approximately one kilogram of CO2 per day.

The next most intensive sector is industry, accounting for over a fifth of global emissions. The industrial sector comprises a broad range of manufacturing processes, including those of chemicals, pharmaceuticals, steel, iron, and cement. Roughly 40 percent of industry’s emissions derive just from the on-site burning of fossil fuels to produce the heat required for these processes.30 For example, the production of cement involves heating limestone (carbon carbonate) to very high temperatures to decompose it into calcium oxide and carbon dioxide. Cement production therefore emits carbon dioxide in two ways: first through the burning of fossil fuels to generate enormous amounts of heat, and second by nature of the chemical reaction itself, which yields CO2 as a by-product. The fact that many industrial emissions are intrinsic to the chemical processes themselves makes it particularly challenging to address. Although switching to renewable energy can eliminate the emissions associated with powering industrial processes, it cannot resolve the CO2 produced by the reactions themselves; however, we will delve deeper into this later.

Discussions around GHG emissions often center on cars: the need to drive less, to switch to electric vehicles (EVs), and to improve transportation infrastructure. Contributing nearly 15 percent of our total GHG emissions, the transportation sector has major potential to decarbonize.* Similarly to the energy sector, most emissions from transportation arise from the combustion of fossil fuels and therefore have the potential to be replaced by renewably generated electricity. Even without the introduction of new technologies, significant reductions may be achieved through improving the efficiency of internal combustion engines, expanding public transit systems, and bettering operational efficiency in transport systems. For example, some estimate that aviation emissions could be reduced by up to two-thirds simply through the implementation of operational changes to enhance efficiency.31 Alternative viable options for travelers, such as high-speed electric trains for short intercity trips, could also significantly reduce the number of flights taking off every day.

Finally, buildings are another major sector behind global carbon emissions. The direct emissions associated with buildings refer to the amount of emissions produced on site. If we also consider the emissions associated with the production of heat and electricity that is then consumed by buildings, the latter account for nearly one-fifth of energy-related CO2 emissions. Clearly, there is the potential for major emission savings by simply improving building design and switching to more efficient heating and cooling systems, lighting, and appliances. The United Nations Environment Programme estimates that increasing building efficiency could prevent nearly 2 Gt of CO2 emissions per year.13 All the more reason to invest in energy- efficient appliances and switch to LED (light-emitting diode) bulbs – it makes sense for both your wallet and the environment.

Hopefully you now have a better idea of where all these emissions come from. That is an important first step to identifying where reductions are needed most if we are to meet the goals laid out by the Paris Agreement. While emissions from all sectors must be addressed if we are to eventually bring our net annual emissions to zero, reducing the emissions associated with the energy sector is especially critical given its connection to other sectors, particularly industry, transportation, and buildings. At this point we will briefly digress to discuss global trends in energy because we believe they warrant special attention.

Global Trends in Energy

The enormous amount of emissions currently associated with the energy sector illustrates the importance of transitioning toward non-fossil energy generation. Technologies that utilize renewable energy sources, such as photovoltaic cells, wind turbines, tidal power, and geothermal heating systems, are already proving to be capable of large-scale heat and electricity production and are occupying an increasing portion of the global energy sector.

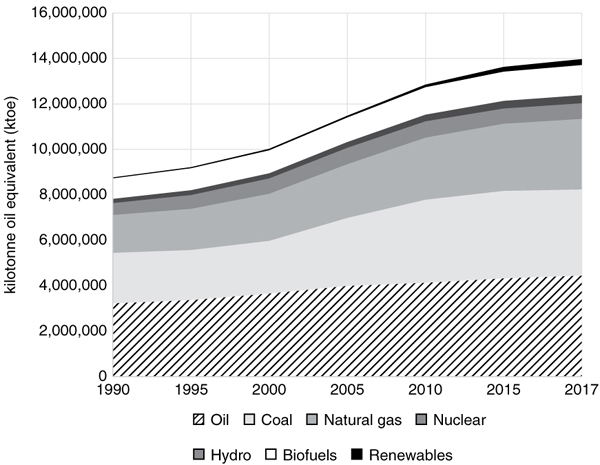

The growth in renewable energy can be better appreciated by observing the trends in global shares of primary energy since 1990, shown in figure 4. The chart displays the amount of energy produced, expressed in kilotonne oil-equivalent, from fossil-based sources (i.e., oil, natural gas, and coal) and from non-fossil energy sources, worldwide. Note that the same quantity of two different fuels can yield different amounts of energy; therefore, to make a just comparison, the amounts have been expressed in terms of kilotonne of oil equivalent, that is, the amount of energy released by burning one thousand tonnes of crude oil.*

Figure 4. Global primary energy supply.

Source: IEA (2019), World Energy Balances.

Hydroelectric power (hydro) has been excluded from the category of renewable energy sources. It involves harnessing the energy of flowing water through a turbine to produce electricity via a generator. The fact that water is not consumed in the process makes hydro theoretically a renewable source of energy; however, it is not included in the category of renewable energy sources largely because of its effect on the environment. Large-scale hydro typically requires the construction of dams that have an impact on natural water systems, aquatic ecosystems, and the silt loads of rivers and streams. Dams can block migrating fish from reaching spawning grounds and can even affect the temperature and chemistry of rivers. The carbon footprint of hydroelectric power has also turned out to be higher than previously thought. The artificial reservoirs, characteristic of hydro projects, give off CO2 and methane through the decay of previously stable soil and vegetation. Put otherwise, dam construction transforms what was once a carbon-sequestering environment (e.g., forests, wetlands) into a carbon-emitting environment. A 2016 study analyzed 1,500 hydro plants from around the world and computed that a global average of roughly 173 kilograms (kg) of CO2 and 2 kg of methane was emitted per megawatt hour (MWh) of electricity produced from hydro.32 While this is much lower than the emissions from fossil energy, it is still significant. The impact of hydro projects varies greatly, and many design measures can be taken to minimize their effects on aquatic wildlife. Dams can also be upgraded to enhance their efficiency and to avoid construction of brand-new projects. So, while hydro is technically a lower-carbon, renewable source of energy, it is not without environmental impacts and a concomitant carbon footprint.

The global energy mix is gradually changing, with non-fossil sources, such as nuclear and hydroelectric power, deemed to represent half of the growth in energy supplied over the next two decades. However, we are currently experiencing a boom in natural gas. With a 1.6 percent annual growth rate, natural gas is now the fastest-growing fuel and is expected to overtake coal as the second- largest source of fuel by 2035. The growth of oil is currently 0.7 percent per year but is projected to decline slowly. The growth of coal is expected to drop even more sharply, by 0.2 percent per year, and will cease to grow in around 2025. The most rapidly growing source of energy, at 7.1 percent per annum, is renewables, which include wind, solar, tidal, and geothermal power. Their share of the primary energy mix is expected to be up to 10 percent by 2035, from 3 percent in 2015. Optimistically, through government policies and financial incentives promoting the use of non-fossil energy sources, this increase will continue.

In renewable energy, Europe currently leads the way, with non-fossil sources expecting to reach around 40 percent of the energy mix by 2035. The largest growth over the next twenty years in renewables, however, is envisioned by China, adding more than Europe and America combined. As solar and wind technologies become more attractive economically, their market share is anticipated to increase worldwide. Indeed, the dropping costs of renewables – the costs of solar and wind power have fallen by 85 percent and 50 percent, respectively, since 2010 – is the main factor driving their adoption. This price drop is owed to a combination of technological improvements and market-stimulating policies. A recent study analyzing the causes of cost reduction in photovoltaic modules, for example, showed that government policies to help grow markets accounted for nearly 60 percent of the overall cost decline.42 The drop in costs has meant that renewable projects are already beginning to operate without government assistance. At the time of writing, solar farms were being built without subsidies or tax breaks in both Spain and Italy. China plans to cease financial support soon to some of its existing renewable infrastructure. In fact, we have reached the point where the cost of developing renewable infrastructure can no longer be used as an argument in favor of fossil energy. A 2018 study, for example, concluded that renewable electricity was already outcompeting oil on price and beginning to challenge natural gas.43 From an economic standpoint, it no longer makes sense to argue in favor of expanding fossil infrastructure when renewables power is already outcompeting all other sources of electricity.

There is a component of systems-level change to electrifying our energy sector. Specifically, increased investment in electricity- drawing technologies tends to advance production of and research in energy-storage devices, which themselves assist in the development of a renewable energy infrastructure. Similarly, increasing the accessibility and affordability of renewably sourced electricity will, in turn, encourage adoption of low-carbon, electric-powered products. In this regard, many recent technological breakthroughs have also rejuvenated hope in a future energy economy built around electricity generated from renewable sources. The replacement of internal combustion engines by EVs is revolutionizing the transportation industry, which currently accounts for roughly 60 percent of all liquid-fuel consumption and 20 percent of all energy consumption worldwide.44 In 2017 there were three million electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles on the road, a 50 percent increase compared to 2016.45 That same year, there were a record 250 million electric bicycles in China.46 The global market share of EVs is anticipated to keep growing given the falling cost of battery packs, the expansion of charging infrastructure, and continued policy support.

On this note, it is worth addressing some claims around the true emissions-reduction potential of EVs. The GHG emissions associated with any vehicle technology is not limited to burning fuel; that is, there are also emissions associated with the multitude of materials and processes – including battery production – involved in manufacturing a new car. We should always ask how the carbon footprint of EVs compares to that of combustion engine vehicles, taking into account all the emissions associated with manufacturing. For the most part, the majority of a car’s GHG emissions emerge from the exhaust pipe. There is some evidence to suggest that simply employing more efficient combustion engines will have a greater impact on carbon-emissions reduction compared to introducing electric cars.44 But, while increasing energy efficiency through carpooling and optimized engine technology is always beneficial, it should not be a reason to avoid the electric option. The true carbon footprint of any one vehicle is complex and depends on the local energy infrastructure and the emissions associated with its manufacturing, distribution, and ultimate disposal. Moreover, studies evidence that, unlike those of combustion engine vehicles, the emissions associated with EVs are only anticipated to drop as the carbon intensity associated with the energy and manufacturing industries declines and the share of electricity from renewables rises.45,47 Moreover, EVs offer additional environmental benefits, such as the reduction of groundwater pollution associated with oils and lubricants. Simply put, it is never too early to purchase an EV.

Amid the excitement of the growing number of electric cars on the road, however, trucks, boats, ships, trains, and aeroplanes still constitute most of the transportation industry’s fuel demand.* The question remains as to whether a large vehicle, bearing heavy cargo and traveling over long distances, can feasibly run on lithium-ion batteries, which remain the technology of choice for electric vehicles.

The answer, until recently, was said to be “unlikely.” The gravimetric energy density (i.e., the amount of energy supplied per unit mass) of lithium batteries is much lower than that of hydrocarbon fuels. Large-volume vehicles and ships carrying heavy cargo would therefore require bigger batteries (or more batteries), and at some point the energy supplied by the battery could not satiate the weight of the cargo and of the battery itself. Nevertheless, decarbonizing large-transport vehicles is not an all-or-nothing scenario. The limitations of current lithium-ion battery technology should not hold us back from attempting to reduce emissions associated with this sector. Hybrid-electric aircraft, for example, in which an electric propulsion system is integrated alongside a jet fuel engine to improve the propulsive efficiency, can offer a means to reducing emissions during flight takeoff and landing.49 Eventually, as battery technology improves, we can conceive of a future with fully electric aircraft.

Already the impossible is becoming possible, with the recent announcement that the first electric-powered autonomous cargo ship will be delivered in 2020, and will be rendered autonomous by 2022.50,51 The maritime engineering firm Kongsberg is developing the battery system, electric drive, and all the components for seaborne transportation and autonomous navigation. The plan is to initially use the vessel as a substitute for land transport: the electric ship is anticipated to replace a total of 40,000 truck journeys every year.

In November of 2017, Tesla unveiled the Tesla Semi, the first heavy-duty, all-electric truck. It can reach an impressive 65 miles per hour going up a 5 percent grade (which is 50 percent faster than the average truck) and boasts a 500-mile range on a single charge.52 Barely ten days later, aircraft maker Airbus, engine manufacturer Rolls-Royce, and electrical technology producer Siemens announced that they would join forces to design and build a hybrid-electric aeroplane. A prototype that would by ready to fly is anticipated for 2020 and could come to market as early as 2030.53

Although these technologies certainly give new hope for a sustainable future, they alone do not constitute the full solution to the electrification challenge of large transport vehicles. Decarbonizing and expanding the electricity grid will be necessary to power a future electrified fleet of aircraft, trucks, and ships. For example, a 2019 study found that a fleet of electric aircraft carrying out all flights up to a distance of roughly 1,000 km would form an equivalent of 0.6–1.7 percent of global electricity consumption.49 In addition to expanding the grid to meet the new scale of demand, the extent of their adoption would ultimately depend on access to cheap renewable electricity. It has been estimated that renewable power would need to drop as low as four cents per kilowatt hour (kWh) to reach economic competitiveness with jet fuel, in the case of aircraft. Furthermore, in the absence of aggressive policy, there are usually considerable jumps to be made for a new technology or product to become competitive on the market, let alone to preempt a well- established industry. Owing to the long design and service times of aircraft, it is anticipated that the aviation sector will likely depend on the availability of liquid hydrocarbons for decades to come. Similarly, heavy-duty trucks, as well as maritime and road transportation, will likely continue to rely first and foremost on liquid hydrocarbon fuels in the near to mid future. Despite the growing uptake of EVs, the number of combustion engine vehicles continues to rise. For example, although the number of EVs on the road is expected to grow to 130–230 million by 2030, depending on the policy scenario,45 the total number of motor vehicles on the planet is projected to reach two billion over this period.54 So, while the growing market share of EVs is not insignificant, it will be some time before electrification takes over the better part of our transportation sector.

Clearly it is challenging for the transportation sector to replace the use of hydrocarbon fuels at the speed required to meet the emission targets set out by the Paris Agreement. However, with the ever-decreasing cost of renewable electricity and continued technological developments, it is possible to imagine a future in which all our power needs – including large transport vehicles – are fully met by electricity generated from renewable energy sources.

The rise in the use of electricity-based technologies and processes to replace hydrocarbon fuels clearly requires the continued development and expansion of a robust electricity infrastructure based on emission-free energy sources. At present the amount of GHG emissions associated with electrical generation varies greatly between countries, and even regionally, because it depends on the local energy infrastructure being used. The range varies from a mere 60 grams (g) of emissions per unit of electricity in Iceland, generated primarily from geothermal and hydroelectric power plants, to 1,060 g of CO2 equivalent per unit in Australia, where coal still remains the dominant source of electricity generation.55

The technical challenge of relying exclusively on renewable energy every day, everywhere on the globe, comes down to the issues of transport, storage, distribution, and intermittency associated with renewable electricity. Technologies such as photovoltaic cells and wind turbines are highly dependent on climate and geography, and limitations to electricity storage make it non-trivial to meet demand at all hours of the day. Still, despite these obstacles, global energy projections show that growth in renewables is underway and will almost certainly continue to rise, especially with new technological innovation and sustained government support.

Although the shift toward non-fossil energy sources is certainly a positive progression, it remains a slow one. Too slow, as a matter of fact. If our emissions trajectory was the hill of a rollercoaster, we would currently be located somewhere between the point of steepest ascent and the maximum height of the hill. The sooner we reach the maximum height of the hill, the sooner we begin the descent. Unfortunately, emissions are unlikely to reach their peak before 2040,56 which does not bode well for achieving our goal of zero emissions by 2050. Our current emissions trajectory results from the fact that, despite growth in renewables, overall fossil-fuel consumption continues to rise. At the heart of this problem lies the USD 5.3 trillion in subsidies that the fossil-fuel industry receives globally each year.57,58 With around 50 percent of our legacy fossil fuels remaining in the ground, many in the industry see little impetus to halt extraction of oil, gas, and coal completely.

Drivers of Emissions

The continued rise in oil, natural gas, and coal consumption is heavily related to the growing demand for energy needed to satisfy the Western lifestyle. A sobering number is the 7,604 kg of oil equivalent that an average Canadian consumes every year.* This amounts to 8.4 × 104 kWh of energy, which can be given context by comparing it with the various processes shown in table 1. The worldwide demand for energy is expected to dramatically increase as the population grows to an anticipated nine billion by the end of the century.

Table 1. Energy consumption associated with various activities.

| Activity | Energy (kilowatt hours) |

|---|---|

| Worldwide energy consumption in 2017 | 1.1 × 1014 |

| Worldwide renewable energy production in 2017 | 3.0 × 1012 |

| Bitcoin’s annual electricity consumption 59* | 4.7 × 1010 |

| Canada’s per capita electricity consumption in 2018 | 1.4 × 104 |

| Round-trip flight New York–London on a Boeing 74761† | 6.2 × 103 |

| Canada’s per capita electricity consumption in 1960 | 5.6 × 103 |

| China’s per capita electricity consumption in 2017 | 4.6 × 103 |

| Barrel of oil equivalent | 1.7 × 103 |

| Driving 100 km in a Model S Tesla at 80 km/h62 | 1.5 × 101 |

| Five hours of running a desktop computer with monitor and printer | 1.0 × 100 |

| Five hours of running a laptop | 3.3 × 10-1 |

| Charging an iPhone 6 (a single charge) | 1.7 × 10-2 |

Unless otherwise specified, data was obtained from IEA statistics © OECD/IEA 2020.

* The idea that the digitization of our industries can lead to lesser environmental impact is largely a myth. Computing infrastructure consumes enormous amounts of energy to operate; for example, bitcoin alone uses more electricity than do some entire countries.60

† This statistic assumes the aeroplane to be 80 percent full. Most flights are not at full capacity.

In addition to our seemingly endless demand for energy, our fossil-fuel consumption is driven by our high consumer lifestyles. Beyond our driving a car and switching on the lights when we get home, every product we purchase and consume, from a new smartphone to a cup of coffee, has associated CO2 emissions. The emissions associated with everyday phenomena can be surprisingly difficult to estimate because the true carbon footprint of any product includes the extraction or harvesting of raw materials, the processing or manufacturing steps, and the distribution and transportation of products – not to mention the further processing and packaging materials, which have their own associated carbon footprints. Furthermore, many of our favorite amenities are made, either directly or indirectly, from oil- and natural gas–derived products. Everything from sports equipment and cosmetics to crayons and chewing gum to aspirin and toothpaste has its origins in petroleum products. Some of our most critical commodities, such as ammonia-based fertilizers, without which current levels of food production would not be possible, call for fossil fuels (in this case, natural gas–derived methane) in their manufacturing process. Indeed, they are so intrinsically tied to our lifestyles and into the global economy that there is hardly a sector of modern society that operates independently of oil, gas, and coal.

So, despite the increasing market share of emissions-free-energy suppliers and technologies, our ever-rising demand for energy makes it difficult for new zero-carbon infrastructure to keep up. What does it take, exactly, to get our emissions under control?

CO2 emissions can be analyzed and projected using the Kaya identity. The concept was first introduced by the current president of Japan’s Research Institute of Innovative Technology for the Earth, Yoichi Kaya, who developed the identity in the early 1990s while he was a professor at the University of Tokyo. According to Kaya, the total GHG emissions can be expressed as the product of human population, gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, energy intensity (energy consumed per unit of GDP), and carbon intensity (CO2 emissions produced per unit of energy consumed):

In other words, an increase in population, GDP per capita, energy consumption, or fossil-fuel usage will result in greater CO2 emissions. Transitioning toward energy sources that emit less, for example by replacing coal with natural gas, can reduce carbon intensity without the need to reduce population or consumption. This highlights a key feature of the Kaya identity: the decoupling of economic growth from carbon emissions.63 In other words, it is possible to reduce CO2 emissions without compromising economic growth.

We should, however, point out that the relative impact of each variable in the Kaya identity is subject to wild variation around the globe. An increase in population, for example, will have less effect on GHG emissions in countries where GDP per capita is low, compared to wealthier countries where it is high. As wealth and resources are not distributed equally around the globe, the Kaya identity does not offer much insight when each variable is taken as a global average. Economic inequality is so acute that the wealthiest 10 percent of global population account for nearly 50 percent of the total lifestyle-consumption emissions. Conversely, the poorest 50 percent are responsible for only about 10 percent of total lifestyle-consumptions emissions.64 If you are reading this book, it is likely that your lifestyle emits 10–20 tonnes per year, upwards of ten times the emissions of an individual who falls within the poorest half of the world’s population.65 The carbon-emissions gap is so wide that even within the world’s “emerging economies,” such as China, Brazil, India, and South Africa, the lifestyle emissions of their richest citizens still fall far from those in wealthier countries. There is even a stark contrast in individual carbon footprints within countries, with South Africa and Brazil being the most extreme cases in which the richest 10 percent have a per capita carbon footprint ten and nine times that of their country’s poorest half of the population, respectively.

Albeit this point is controversial, population size still has direct consequences on global energy consumption and carbon footprint. On the global scale, slowing population growth could provide roughly 16–29 percent of the emission reductions necessary to achieve our long-term climate goals, such as limiting warming to no more than 2°C.66 However, stating that we simply need to “stop having children”67 is not a particularly helpful message and grossly oversimplifies the complexity of population dynamics, not to mention that it ignores the dramatic variability in per capita consumption. Sudden shifts in a country’s population pyramid, for example, can have unintended social and economic complications associated with an aging demographic.68 Moreover, population-control policy is understandably a complicated and sensitive issue with a long history of forced sterilization targeted at marginalized peoples.69,70 Selective focus on population instead of per capita consumption as the principal driver of emissions places unfair responsibility on the global south; after all, countries with the highest fertility rates tend to have the lowest per capita carbon footprint, whereas consumption in developed countries with declining birth rates has been the principal driver of climate change to date.71 As Detraz writes in her book Gender and the Environment, “shining light on population is often done without simultaneously (or alternatively) spotlighting the connections between patriarchal economic processes, consumption levels, lifestyle choices, and environmental change.”72 Clearly, population control as a strategy for emissions mitigation must consider the multiplex economic, social, and political processes that drive global trends in birthrates.

Even the most aggressive population strategies, such as imposing a worldwide one-child policy, although undeniably beneficial in the long term (i.e., in the coming centuries), would offer little to no effect in mitigating emissions in the coming decades and therefore would not provide a quick fix for meeting our near-term emissions targets.73 Furthermore, there exist highly effective alternatives to implementing radical population policies. Investing in family-planning programs and female education has been demonstrated to have a positive impact on the health of both humans and the environment in the short and long term. Family-planning programs have already been demonstrated as an impactful and cost-effective means to control fertility rates in many countries,74 and women’s education and empowerment can enable further control of fertility, as well as alleviate poverty and provide a more skilled labor force. Most interestingly, it has recently been suggested that offering universal general education, particularly at the primary and secondary levels, could be the key to enhancing climate-change adaption because it promotes social capital and reduces vulnerability to natural disasters.75,76 Indeed, it turns out that teachers may be just as, if not more, important than engineers and policymakers when it comes to tackling climate change.

While the Kaya identity offers a helpful way of modeling different energy scenarios, it carries limitations and should therefore be interpreted carefully. Factors such as GDP per capita and energy intensity (i.e., consumption per GDP), for example, are not entirely decoupled from one another in reality. And, as mentioned earlier, when taking global numbers, the formula does not properly capture local information, regional variations, or the relationship between population growth and CO2 emissions. The interplay between demographics, energy consumption, and social and economic development are non-trivial, to say the least.

What the Kaya Identity does illustrate, however, is that emissions can be reduced without compromising population or economic growth, by lowering energy and carbon intensity. Economic indicators and carbon-emissions data confirm that carbon intensity and economic growth are not always linked. From 2008 to 2015, for example, the United States reduced its emissions by 1.4 percent annually and yet also experienced economic growth by 1.4 percent annually.77

The question remains as to the rate and the extent to which energy and carbon intensity can be reduced. Informed and ambitious policy, together with focused investment in carbon-reducing technologies, is necessary to effectively reduce carbon emissions within the time frame required by the Paris Agreement.

A Race against Time

At the time of the industrial revolution, during the period of its development from 1760 to 1840, Europeans made a gradual transition from human-, horse-, and oxen-powered machines to machines powered by fossil fuels. The creation of this new fossil- based energy infrastructure took about a hundred years. The world’s present fossil-based energy infrastructure, requiring trillions of dollars, was built over a century. Transitioning away from our current system to one that is based on carbon-neutral and renewable energy will take time and sustained investment. History tells us that such an energy transition is likely to take several decades or longer, possibly stretching to the end of the twenty-first century.

Given the bleakness of the situation, it is not surprising that certain advocates are calling for other approaches, such as geoengineering, to prevent the impacts of climate change. Although geoengineering might have once been reserved for the realm of science fiction, being deemed too audacious for real-world implementation, the approach is now being increasingly endorsed by academics, technologists, and climate advocates who believe that it is our only remaining choice for lessening the worst effects of climate change. In his 2017 Joule commentary, MIT professor emeritus John Deutch writes: “It is difficult to be optimistic that mitigation on its own will protect the globe from the consequences of climate change ... the world must urgently turn to learning how to adapt to climate change and to explore the more radical pathway of geoengineering.”63

Geoengineering: planetary-scale interventions aimed at managing the greenhouse effect by directly modifying the earth’s climate system.

Geoengineering strategies currently comprise two streams. The first includes technologies aimed at directly removing CO2 from the atmosphere, and the second is based in solar-radiation-management methods to modify the albedo of the planet. Ideas for direct GHG removal include adjusting land-use management to enhance carbon sinks, and enhancing natural weathering processes to remove CO2 from the atmosphere more efficiently. Solar-radiation management, however, involves more direct approaches, such as stratospheric aerosol injection. In this method, solar-radiation-blocking particles are put into the stratosphere to induce a reflective effect in a manner analogous to the release of gases during a volcanic eruption. Compared to carbon-dioxide- removal methods, stratospheric aerosol injection, once deployed, could potentially reverse planetary warming within a few years. A recent study estimated that a future program to deploy stratospheric aerosol injection could cost as little as USD 2 billion per year.78

Albedo: a measure of solar reflection off a surface, usually on a scale of 0 to 1.

Aerosol: a mixture consisting of solid or liquid particles suspended in a gas.

Still, opponents of geoengineering often point to its unforeseen consequences and its lack of addressing the root problem of burning fossil fuels. Stratospheric aerosol injection, for example, requires additional injections as a result of particles precipitating, and the impacts are unlikely to be uniform around the globe. The IPCC’s 2018 report Global Warming of 1.5°C also acknowledges the potential ecological and health risks associated with altering weather patterns and atmospheric chemistry; however, it concludes that geoengineering strategies, particularly stratospheric aerosol injection, could be used as a supplementary measure to meet the 1.5°C target.79 The decision to include aerosol injection, however, is largely due to the absence of alternative technologies that are able to reduce emissions quickly enough.

Solar geoengineering research pioneer Dr. David Keith of Harvard University, though careful not to endorse the strategy wholly, points out that the evidence for solar geoengineering to reduce climatic hazards is strong and that, although doing it certainly carries risk, there are also risks to not doing it.80 So, while a multinational geoengineering program remains unlikely in the near future, the possibility has become the subject of serious consideration and deserves attention by climate researchers as anthropogenic emissions continue to rise.

The urgency in reducing GHG emissions has never been more evident. Allowing temperature rise to exceed a mere half degree beyond the 1.5°C target poses major risk to all life on the planet. The frequency of extreme weather events, such as droughts, floods, forest fires, and extreme heat, would increase significantly, forcing hundreds of millions into poverty. A mere half degree over the limit risks doubling the number people experiencing water insecurity. Insect species vital to crops may become completely eradicated by a mere additional half-degree rise in temperature, creating global food scarcity. Coral reef ecosystems may not survive, marine life would sharply decline, and sea-levels rise could add an additional ten centimeters to coastlines.

Yet somehow the sheer scale of the issue, together with political barriers, has made the execution of solutions (at best) slower than necessary. Any serious strategy to combat climate change must involve understanding the reasons the reduction of emissions remains a challenge and what it will specifically take to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement. Do we have an existential problem that is too big, too complicated, too costly, and too political to solve?

KEY TAKEAWAYS

• CO2 emissions should peak to no more than 30 Gt per year by 2030 (a ~45 percent decline from 2010 levels) and then need to be reduced to zero by 2050 for a decent chance of global temperature rising to no more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

• Fulfillment of every country’s original nationally determined contributions set out by the Paris Agreement will not allow us to meet the 1.5°C target.

• Limiting global temperature rise to 1.5°C requires the rapid reduction of emissions across all sectors of the economy – energy, land, buildings, transportation, and industry. Enhancing atmospheric carbon sequestration (i.e., creating negative emissions) will be necessary.

• Globally, the energy sector, which involves the production of heat and electricity, contributes more emissions than does any other sector, with coal-based power generation being the single biggest contributor to global temperature rise.

• Despite the rise in adoption of renewable energy sources, and increased electrification efforts, fossil-fuel consumption continues to rise.

• It is possible to reduce GHG emissions without compromising economic growth.

• Population control is not an effective strategy for meeting our near-term emission targets.

__________________

* Although 2018 was the coolest of the five years, it was marked by the La Niña phenomenon, which characteristically begets lower temperatures and therefore should not be misinterpreted as a reversal of the rising temperature trend.

* The total number of greenhouse gas emissions is over 50 Gt a year if we include the contribution of methane, nitrous oxide, and fluorinated gases.12

† Specifically, this corresponds to the volume of CO2 at 1 atm (the atmospheric pressure at sea level), at which the density of CO2 gas is 1.98 kg/m3.

* The production and consumption of energy together account for over 70 percent of all GHG emissions

* The greenhouse gas emissions resulting from transportation vary dramatically across the globe and are heavily tied to unequal patterns in consumption. In wealthier countries, for example, where there are more cars per capita, transportation generally accounts for a larger share of total carbon emissions.

* The carbon content of fossil fuels does not scale with the energy they provide because of the different organic content in each fossil fuel. One tonne of natural gas contains 0.75 carbon content and yields 50.2 gigajoules (GJ) of energy. The same amount of oil and coal contains 0.84 and 0.85 carbon content but yields 41.6 and 26.0 GJ of energy, respectively. For the same reason, the exact hydrocarbon content of a barrel of crude oil varies somewhat between locations.

* Traditional nuclear reactors typically offer anywhere between several hundred to a few thousand megawatts of power, depending on the scale of the site.

* Aeroplanes are among the worst emitters in terms of CO2. The combustion of jet fuel by aircraft account for 2 to 3 percent of all energy use–related CO2 emissions. On top of the massive fuel requirements of aeroplanes, emissions released at higher altitudes are nearly twice as potent as emissions released at ground level. Cargo ships, by contrast, have the lowest CO2 emission levels of any other cargo transportation method, generating fewer carbon emissions per tonne of freight per kilometer compared to those of barges, trains, and trucks. Still, the heavy fuel oil that cargo ships burn has a particularly high sulfur content, resulting in significant amounts of sulfur oxides and nitrogen oxides being emitted from ship smokestacks. Sulfur oxides pose a particularly high risk to human health and the environment, and the shipping industry accounts for 13 percent of these emissions annually.48

* IEA statistics © OECD/IEA 2020.