The environment in its largest sense creates the context in which choice is made, but the choice is made by individuals.

LEACH (1970 [1954]:259)

I focus on economically stratified (including incipient) agricultural societies, and how and when wealth differences transform into political power. Specifically, how do a few people get others to contribute their labor, goods, and services without compensating them equally? My definition of political power reflects the focus on surplus appropriation, and therefore my perspective is necessarily materialist. Thus, I view resources as a condition for, not a cause of, political complexity (cf. Fried 1967:111; Russell 1938:31) and focus on the way people interact with their natural and social surroundings. My approach is not environmentally deterministic but acknowledges the key role that resources play in surplus production, especially rainfall dependency and the degree to which people rely on water or agricultural systems. Long-term climate change (e.g., rainy seasons begin later than usual or are shorter than usual, temperatures drop slightly, and so on) has various, and sometimes drastic, impacts on agricultural and political systems (see Fagan 1999, 2004). After all, no matter how unique people are in terms of how they think, act, and create, they still need to survive and interact with the material and social world. The way in which surplus is appropriated, however, is another matter; and this is where the role of ritual is crucial.

I discuss water (especially seasonal vagaries) and ritual separately, because to appreciate the whole we must first understand its constituent parts. In doing so, individual factors can only appear as static entities. Nevertheless, my goal by the end of this work is to discuss them as an integrated, dialectical, and dynamic system. Edmund Leach (1970 [1954]: 63; emphasis in original) said it best when he explained the challenges of detailing structural change between gumsa and gumlao organization in highland Burma:

I assume that the system of variation as we now observe it has no stability through time. What can be observed now is just a momentary configuration of a totality existing in a state of flux. Yet I agree that in order to describe this totality it is necessary to represent the system as if it were stable and coherent.

This being said, it is important to acknowledge that the model presented does not and cannot account for all the varied political histories; instead, I attempt to provide an idealized general organizational framework from which to evaluate under what material and social conditions political leadership develops and fails. The defining traits of each political type are not static and impermeable; they are fluid and part of a continuum and only a heuristic device. The use of types is simply an attempt to separate the constituent parts of complex and dynamic systems (see Klejn 1982:17, 52). My goal also is to avoid the baggage that usually comes with using traditional terminology that implies stages through which all societies must pass in the drive toward complexity (such as tribes, simple chiefdoms, complex chiefdoms, and states). The systems I describe thus can be viewed synchronically (nested hierarchies), diachronically (changing political histories), or as separate entities (autonomous); different political systems can apply to societies in different times and places or to a single culture during a specific period. In the Maya case, various southern lowland centers are evaluated either as separate polities or as nested hierarchies during the Late Classic period.

People interact with natural and social forces in various ways, resulting in varied political histories. Given that there are a limited number of responses (Friedman and Rowlands 1978), however, similar processes must be at work (Earle 1997:193). The model thus provides a useful construct to illuminate the inner mechanisms of political systems and how they emerge, expand, and fail.

There is no doubt that many types of relations can and do exist within social systems (e.g., kinship, alliance, marriage); here I focus specifically on how seasonal water issues and ritual bear on political systems. Finally, while the cross-cultural case studies that I use to illustrate the varied political systems are well known, what is different is the way in which I discuss and situate them.

In this chapter I introduce the different types of political systems (community, local, and centralized and integrative polities) and the factors that distinguish them. I then detail the step-by-step process of how rulers emerge and the crucial role that ritual plays in their rise, maintenance, and loss of power. I define political collapse and discuss the relationship of short-term and long-term seasonal climate change and resource stability with political power. Finally, I discuss ritual and collapse and present a scenario illustrating a political history.

Political Systems

The distribution of critical resources affects how people settle across landscapes, which in turn bears on the ability of aspiring leaders to communicate ideas and to conduct large-scale activities (political rallies, feasts, and work parties) (Roscoe 1993). Densely settled areas where people are tied to the land through investments in subsistence technology (e.g., plowed fields, canals, dams, agricultural terraces, fish ponds, transportation, storage buildings) facilitate the consolidation of power (Carneiro 1970; Gilman 1981; Hayden 1995), because political aspirants can more easily access critical resources and surplus (Earle 1997:7). Dispersed populations that rely on scattered resources are more difficult to organize, regardless of surplus potential. Aspiring leaders thus need to bring people together physically, and they accomplish this through funding and conducting integrative events and providing some type of material benefit. Political demands (e.g., corvée labor), however, are superimposed onto existing economic and social institutions that may or may not be affected by the waxing and waning of political power.

Surplus funds the political economy. Without it everyone would be concerned only with household and community obligations. This scenario would not leave much time or money for emerging rulers to recruit followers; organize military campaigns; sponsor public works, monumental building projects, and public spectacles such as feasts and ceremonies; support royal family members, retinues, or administrators; and fund artisans (see Sahlins 1972 :101; Wolf 1966:4–9). Without surplus production, farmers could not take time off from working in their own fields to labor in the fields of their patrons or of the political elite, not to mention provide corvée labor to build the material manifestations of political power (e.g., Sahlins 1968:92). And even if rulers owned or controlled, for example, large plots of agricultural land, they could not benefit from the fruits of the land if they could neither afford to pay laborers nor implement labor demands on others. Access to labor, thus, is more critical than resource control—surplus labor, that is (cf. Russell 1938:31). The point is this: whatever the source of surplus, it is a must for anything political.

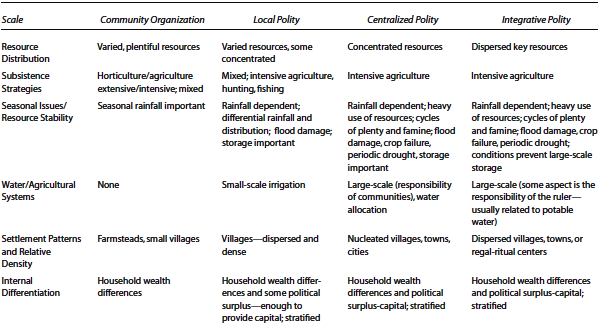

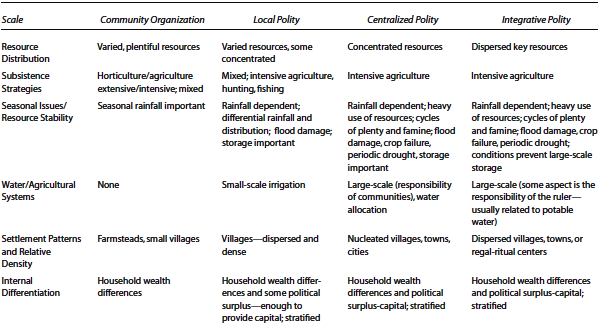

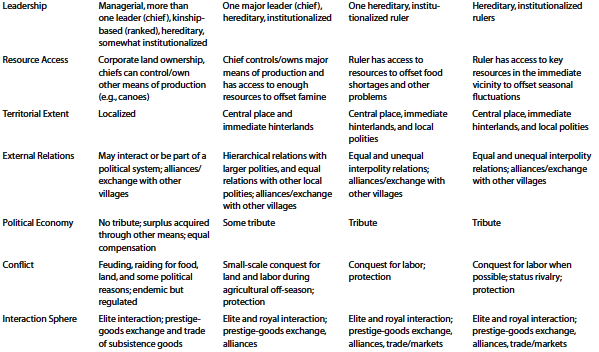

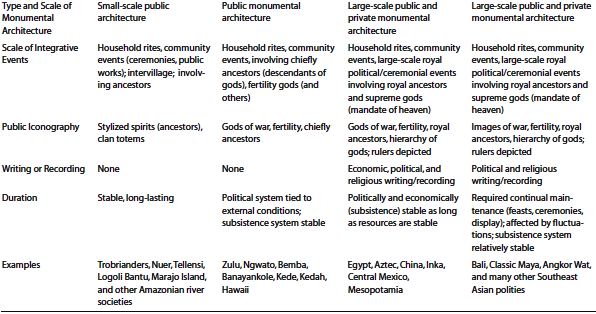

For the sake of simplicity, I define four kinds of political systems—community organization, local polity, and centralized and integrative polities. Each is detailed in Chapters 4, 5, and 6 and described in terms of resource distribution, subsistence strategies, seasonal issues and resource stability, presence of water or agricultural systems, settlement patterns and relative density, internal differentiation, leadership, resource access, territorial extent, external relations, political economy, conflict, interaction sphere, type and scale of monumental architecture, scale of integrative events, public iconography, the presence of writing or recording, and duration (Table 1.1). While I discuss some factors more than others, I include them all here to provide a more complete backdrop.

RESOURCE DISTRIBUTION: Water supply and critical resources (concentrated, dispersed, or extensive agricultural land and other resources) bear on population size and density, as well as whether or not resources potentially can yield a surplus.

SUBSISTENCE STRATEGIES: This factor relates to the amount of surplus produced, as well as how it is distributed and for what purpose it is used (e.g., to procure prestige items, to contribute to political coffers, and to build monuments and public works).

SEASONAL ISSUES AND RESOURCE STABILITY: Seasonal food scarcity and/or water shortages, transportation problems, heavy rainfall resulting in property damage, flooding and erosion, hurricanes, water allocation, and other natural disasters (e.g., blight, hail, crop diseases, and pests) are factors that the political elite can use to their advantage (for example, store food and repair flood-damaged subsistence technologies) (e.g., Scarborough 2003).

WATER OR AGRICULTURAL SYSTEMS: Reservoirs, check dams, canals, terraces, and other subsistence technologies reflect local adaptive strategies as well as the number of people they can service. Their location and scale typically reflect their role in politics (e.g., water allocation). Small-scale systems are built and maintained at the household and/or community level; large-scale systems are funded or built, or at least maintained, by a political body.

SETTLEMENT PATTERNS AND RELATIVE DENSITY: The number of people and the way in which they are distributed across the landscape affect the ability of leaders to incorporate and communicate with people, not to mention their ability to tap the surplus of others.

INTERNAL DIFFERENTIATION: This factor distinguishes wealth differentiation from political power. In the former, wealthy people equally compensate others for goods and services; in the latter, the political elite exacts tribute without equal compensation to fund the political economy.

LEADERSHIP: The number and the type of leaders are significant factors relating to who has access to the most surplus (e.g., several clan leaders or chiefs versus one institutionalized ruler).

RESOURCE ACCESS: Garnering the means of production is key in any political system (Fried 1967) for gift giving and to fund public works, ceremonies, and feasts. Wealth provides the means to sponsor integrative events and create obligatory relations (debt). Political leaders also provide capital to repair public works damaged by weather gods (flooding, hurricanes, hailstorms, etc.) and food when necessary from their own stores or acquired via trade (e.g., Scarborough 2003:96–99).

TERRITORIAL EXTENT: This involves community, local, or regional territorial extent, or how many people rulers incorporate.

EXTERNAL RELATIONS: This includes equal or unequal external relations and the nature of ties with other groups (e.g., peer political alliances, subjugated polities or communities, and heterarchical relations).

POLITICAL ECONOMY: This involves the ability to exact tribute. The amount of surplus that rulers extract corresponds with the degree of political power. Paying taxes does not negate resistance on the part of farmers, who use various strategies to avoid paying onerous demands (e.g., Adas 1981; Joyce 2004).

CONFLICT: Incorporating more people via conquest results in more tribute and hence greater political power. Rulers also provide protection from outsiders and keep internal conflict under control. Conquest differs from raiding, in which the goals are to steal food and kidnap women (and acquire land, if possible) (Johnson and Earle 2000:249) and which involves feuding among lineages.

INTERACTION SPHERE: This involves prestige-goods exchange, political alliances, and royal marriages. The way in which and degree to which elites and royals distinguish themselves reflect wealth and extent of power. It also involves the exchange of goods between commoners, typically free from elite interference.

TYPE AND SCALE OF MONUMENTAL ARCHITECTURE: These features reflect labor organization (compensation versus tribute), restricted (royal) versus public activities, and the number of participants (e.g., size of public areas; Moore 1996).

Table 1.1. Political systems

SCALE OF INTEGRATIVE EVENTS: This includes household rites, small-scale community ceremonies, and large-scale public ceremonial and political events. Successfully propitiating supernatural entities guarantees material rewards for both intermediaries and participants.

PUBLIC ICONOGRAPHY: This represents what is significant in political, social, and religious life, which is visible for all to witness and absorb.

WRITING OR RECORDING: The presence of a writing or recording system indicates the need to keep track of important royal and supernatural events, economic transactions (taxes and trade), and ideas, usually for an exclusive few (Postgate et al. 1995).

DURATION: This factor highlights differences between political and occupational histories. The length and stability of political systems relate to specific circumstances and surplus availability. Changing political fortunes typically do not affect daily living (settlement, subsistence practices)—political collapse often results in people abandoning their kings, not their land and homes.

In brief, community organizations have several leaders (e.g., lineage heads, village chiefs) who are unable to implement tribute demands but who use their wealth to distinguish themselves materially. Farmers are extensive and/or intensive agriculturalists who rely on seasonal rainfall but do not rely on water/agricultural systems. People honor ancestors through public ceremonies. Local polities differ from community organizations because they have denser settlements, rely on small-scale water/agricultural systems, and have one major institutionalized leader (e.g., a paramount chief). In exchange for what leaders provide in times of need, such as providing food during famine and capital to repair water/agricultural systems damaged by heavy rains or flooding, people contribute labor and goods to political coffers. Their power to acquire surplus from others is conveyed in public ceremonies which thank chiefly ancestors.

Centralized polities represent the pinnacle of political power, and there is little doubt that rulers’ capital and abilities to reach the supernatural are necessary in situations where dense regional populations rely on rainfall, intensive agriculture, and large-scale water/agricultural systems. Their success is publicized in large-scale ceremonies with roots in traditional rites. In integrative polities, the ruler has a similar role. The distinguishing features are that key resources and settlement are more dispersed, two factors that pose a challenge for rulers to integrate people. They succeed in doing so through frequent ceremonies, feasts, and other displays as well as playing a major role in funding large-scale water systems. A greater reliance on large-scale water/agricultural systems in the face of changing climate patterns, however, can also be a formula for disaster.

The question is, who superimposed political demands? How were people able to accomplish this feat and in many cases expand the political economy? Clearly, material resources are critical. Just as critical, or even more so, is ritual; simply put, those persons interested in acquiring power use ritual as a means to achieve their ends.

Ritual and Political Power

Ritual is not in good odour with our intellectuals…. In their eyes only economic interests can create anything as solid as the state. Yet if they would only look about them they would everywhere see communities banded together by interest in a common ritual; they would even find that ritual enthusiasm builds more solidly than economic ambitions, because ritual involves a rule of life, whereas economics are a rule of gain, and so divide rather than unite.

HOCART (1970 [1936]:35)

This section and the following one address the question of how a few people get others to contribute labor and services without compensating them equally. There are many pathways to political power, all of which have several common elements (see Godelier 1978). For example, Michael Mann (1986) argues that economy, ideology, military force, and politics are the four sources of social power or the means of social control. Similarly, Timothy Earle (1997) views economy, ideology, and the military as sources for political power or the expansion and domination of the political economy. Richard Blanton (1998) distinguishes two major sources of power: an objective base (material) and a cognitive-symbolic base (shared ideology). While alternative pathways to power exist (e.g., Flannery 1972), more centralized political systems develop when more sources of power are controlled and integrated (Earle 1997:210–211). Local circumstances (cf. Fried 1967:37–38; Trigger 1991) and how people interact with other people and adapt to their surroundings affect the ultimate success and duration of different political strategies, as well as the amount of goods and labor that political leaders can extract from others (e.g., Earle 1997:15). Further, “these generic sources of power may in fact be universal to the political process in human society, but the outcomes are highly variable” (Earle 1997:193).

A common factor in all political success stories, whatever their origins, is ritual. Political aspirants integrate people, promote political agendas, and situate political change within known cultural constructs through the replication and expansion of traditional rituals. They incorporate new elements in such a way as to make them seem as timeless and natural as the original rites. Emerging leaders not only take on the role of ritual specialist but, more significantly, serve as intermediaries between people and gods. Consequently, rituals reflect this new role, but in traditional formats.

Edmund Leach (1966) notes that ritual pervades all aspects of society and life, and thus it is not surprising that the politically ambitious transform ritual action into political fortune (e.g., Bourdieu 1977 :41). Ritual integrates religious, social, economic, and political life, including, for example, creating and maintaining alliances through marriage and long-distance trade (e.g., Friedman and Rowlands 1978), warfare (e.g., Carneiro 1970), and integrative activities such as constructing public works (e.g., Service 1975:96) and sponsoring religious ceremonies, political rallies (e.g., Kertzer 1988), and feasts (e.g., Hayden 1995; Hayden and Gargett 1990). How these various factors intersect largely determines the pathway to power. Through ritual, political actors involve active participants in political change rather than passive observers (e.g., Joyce 2004).

Leaders, by rights as lineage elders and heads of military societies, kinship groups, and religious sodalities, often promote political change through ritual (Kertzer 1988:30) in which they show that their success benefits all members of society (Godelier 1977:111–119). They organize the building and maintenance of religious structures, subsistence technology including irrigation systems, and canoes or roads for trade and craft production facilities and lead raiding parties—activities that typically involve ritual. Their role presupposes their abilities to lead and provides the opportunity for expanding their influence outside their particular group. Often successful aspirants are descendants of founding families, who have closer ties to original ancestors—another predisposition in their favor.

Each group has special ties to an aspect of the supernatural world, which political aspirants appropriate to highlight their special abilities (Bloch 1986). Emerging political elites claim closer ties to the supernatural world (particularly ancestors), using the same means employed by kinship lineage heads, who themselves often are politically ambitious (Friedman 1975). As descendants of founding ancestors, they connect with more people (Bloch 1986:86). As intermediaries, they receive offerings that once were made directly to the ancestors (Friedman 1998; e.g., Friedman and Rowlands 1978; Helms 1998; Joyce 2004; McAnany 1995) and other supernatural forces.

… this development is an internally determined evolution, the outgrowth of the operation of the political economy within a pre-structured kinship system. Thus, the transformation to ranked hierarchy can be explained without any external references. Nothing new has been added, but certain relations have emerged as dominant on the social level which were previously only latent in the supernatural realm. A headman becomes a chief by taking on some of the properties formerly possessed only by the deities. (Friedman 1998: 129)

For example, among the Kwakiutl, Eric Wolf (1999:103) notes:

Since chiefs are represented as “iterations” of the founding ancestor or donor, they are equated with the creators or progenitors of the human groups over whom they exercise authority. Because the original donor or ancestor first occupied the resource area that will subsequently be utilized by his group, the chief is also “owner” or manager of that resource base. Since the original donor was endowed with valuables—houses, crests, masks, songs—the chief also keeps and wields these prerequisites.

Maurice Bloch (1986:117–119) explicitly details how the circumcision ritual in nineteenth-century Madagascar, in which every Merina male took part, was transformed into a state ritual using the same rules of descent and authority. “The state took on the appearance of a large descent group, the descent groups took on aspects of being a constitutive part of a small kingdom. As a result, at the same time as the child renewed the blessing of the ancestors through circumcision, he also became a subject of the king,” whereby he basically made a declaration of his allegiance (pp. 117–118). The entire kingdom is thus represented as one descent group. The king also takes on the authority structure of kinship; earlier it was elder to younger; later, and in addition, it became king to subject, as the king took on the role of elder (p. 192). The Merina king also was able to keep an accurate count of men for taxation purposes (p. 144): he required a specific time (every seven years) for the circumcision ritual to take place (p. 126). The ritual itself was performed privately in houses that involved family and community members (p. 115). Afterward, the king traveled the land, “performing rituals at a number of specified sites to which were brought the children who had been circumcised” (p. 115). The royal circumcision ceremony was quite spectacular and included an elaborate procession with members of the court and army (p. 127).

By what means do political aspirants succeed? In a word, surplus. To be more specific, it takes material capital to support rulers, their families, and their retinues and to sponsor public works and integrative events (e.g., Hayden 1995; Hayden and Gargett 1990; Trigger 2003: 375). Consequently, adequate resources necessary to generate a surplus are a must, whatever the reasons for political change (Engels 1964 [1957] :274–275). While material factors have varying roles in the emergence of rulership, material resources undeniably are required to support the political economy. Promoters attract supporters and simultaneously create obligations that last beyond the time frame of rituals. This strategy results in long-term material benefits (e.g., debt relations). “A man possesses in order to give. But he also possesses by giving. A gift that is not returned can become a debt, a lasting obligation …” (Bourdieu 1990:126, 1977:191–195). These public events thus promote the production of surplus (Hayden 1995; Hayden and Gargett 1990) and enable political agents to acquire it.

As briefly mentioned, the first political agents likely come from founding family stock; their wealth, as descendants of first-comers of any given area and owners of prime land or other resources, allows them to sponsor community or small-scale public rites. These actions result in obligations whereby sponsors materially come out ahead. The scale on which rituals can be performed and the amount of surplus acquired vary in any given area.

The obligations created are not just unidirectional. With leadership come duties and responsibilities. Rulers now are obligated to take care of those who, at one level, pay for their services and protection (e.g., Leach 1970 [1954] : 187). They are duty-bound to help clients or subjects in times of trouble and need. Failing to fulfill obligations or violating subjects’ trust can result in the “contract” becoming null and void (Scott 1990:104). Finally, rulers’ power may be limited or constrained to some degree because of the challenges of living up to the “idealized presentation of themselves to their subordinates” (p. 54). For example, regarding the relationship between serfs and their aristocratic masters in feudal Europe, James Scott (1990:104; emphasis in original) writes:

…it would be important to understand how their claim to hereditary authority was based on providing physical protection in return for labor, grain, and military service. This “exchange” might be discursively affirmed in an emphasis on honor, noblesse oblige, bravery, expansive generosity, tournaments and contests of military prowess, the construction of fortifications, the regalia and ceremony of knighthood, sumptuary laws, the assembling of serfs before their lords, exemplary punishment for insubordination, oaths of fealty, and so forth. The feudal “contract” could be discursively negated by any conduct that violated these affirmations: for example, cowardice, petty bargaining, stinginess, runaway serfs, failures to physically protect serfs, refusals to be respectful or deferential by serfs, and so forth.

In this and other cases, problems can arise when nonelites buy into an elite or royal ideology more than elites or royals themselves do (p. 104).

In sum, while various ways of acquiring political power exist, the general processes of situating change typically do not; and a material foundation (namely, surplus goods and labor) is required. Ritual expansion occurs in tandem with political change, both of which are funded by surplus goods and services. Rituals express and explain the changes occurring through familiar means. Ritual thus is not a source of political power in the same manner as the military, economy, and ideology but rather advances political agendas based on these intersecting sources of power. It allows people to redefine the worldviews and codes of social behavior that explain “why specific rights and obligations exist” (Earle 1997:8, 143–158; see Blanton et al. 1996; Wolf 1999:55). After all,

…the same rite should seem to produce multiple effects while keeping the same components and structure…. Conversely, just as a single rite can serve several ends, several rites can be used interchangeably to bring about the same end…. What matters most is that individuals are assembled and that feelings in common are expressed through actions in common. But as to the specific nature of these feelings and actions, that is a relatively secondary and contingent matter. (Durkheim 1995 [1912] :390)

I have described how the politically ambitious use ritual to serve political ends. But how does this process occur?

Ritual and Political Change

Traditional power has on its side the force of habit; it does not have to justify itself at every moment, nor to prove continually that no opposition is strong enough to overthrow it. Moreover, it is almost invariably associated with religious or quasireligious beliefs purporting to show that resistance is wicked.

RUSSELL (1938:38)

Rulers incorporate traditional beliefs and practices into more elaborate forums to situate political change using culturally familiar means. History has shown that the most successful rituals derive from the home (e.g., Bloch 1986). Needless to say, rituals sponsored and performed by rulers serve to integrate larger numbers of people than could ceremonies conducted in the home. However, rulers do not replace or restrict them. Consequently, public ceremony promotes solidarity, not to mention political agendas (Kertzer 1988; e.g., Joyce 2004). Ritual expansion occurs in tandem with growing political inequality. Rulers eventually link their rule with the continuance of vital elements of life such as fertility and rain (Rappaport 1999:281). They are looked to as munificent providers of plenty but are also blamed during periods without plenty (Lincoln 1994 :207). The obvious, conspicuous displays of “wealth, material resources, mass approval or record-high productivity all tangibly testify to the fruitful fit between the particular social leadership and the ways things should be” (Bell 1997:129).

Pierre Bourdieu (e.g., 1977, 1990), Anthony Giddens (e.g., 1979, 1984), and others emphasize the importance of the dynamic relationship between structure (material and social) and practice. Structure provides choices and constraints or limits within which individuals practice or act but does not determine behavior. This flexible structure leaves the door open for variability and change. Hence, different but culturally acceptable behavior feeds back into the structure, transforming it. Consequently, the process of social change can be, and often is, incremental and typically comes from within a social group (Giddens 1979:223, 1984:247). As actions are imitated and reproduced, agents can affect change. Traditional rituals serve as an ideal forum for emerging rulers to insert and justify their own political agendas

…just because of [their] conservative properties. New political systems borrow legitimacy from the old by nurturing the old ritual forms, redirected to new purposes. (Kertzer 1988:42; emphasis in original)

Memories associated with … earlier ritual experiences color the experience of a new enactment of the rites. Rites thus have both a conservative bias and innovating potential. (Kertzer 1988:12)

Invoking ties to the past makes new ideas or change appear traditional (Bell 1997:149); they “contextualize and subordinate the current moment, thereby ordering the relations of the past and present and establishing a sense of continuity, security, and direction” (p. 168). Changes thus are “reconciled with tradition” (Pauketat 2000:123). These rituals are successful because they incorporate the same familiar traditional practices into more elaborate and larger settings to situate the growing political power of particular interest groups (cf. Bourdieu 1990:109–110; Flannery 1972; Weber 1958 [1930] :55). “[M]any of the originators of the changes in the ritual were conscious of the political implications of what they were doing, and that this motivated what they did” (Bloch 1986:162). For example, the Merina circumcision ritual basically remained unchanged (p. 122). There were some new elements, however, that identified it as a state ritual (e.g., a schedule and required fee/tax) (p. 115). A less successful alternative is abrupt or extreme change. Such actions are much less likely to succeed because new ideas, beliefs, and practices are too foreign and thus unacceptable. For example, the first emperor of China, Ch’in Shih Hwang Ti,

… made an abrupt attempt to replace the prevailing Confucianist political philosophy, which emphasized moral precepts as the basis for social tranquility of the state, with a strongly pragmatic legalist doctrine backed by centrally administered, coercive force…. This attempt was an abject failure and resulted in the destruction of the emperors’ administration and dynasty after only 15 years. (Webster 1976:824)

Another well-known example comes from ancient Egypt. For a brief time in the late Eighteenth Dynastic period, a “heretic” king, Akhenaten, ruled Egypt (1353–1335 BC) (Kemp 1991:262–273). His claim to fame, or infamy, is that he implemented major religious reform by rejecting the human form of the sun cult (Amun or Amun-Ra) and replacing it with the sun disk, the Aten, a “disk from which many rays descended, each one ending in a little hand” (p. 262). Images of Amun, as well as other gods from the vast Egyptian pantheon, were defaced. Akhenaten established a novel temple format with open courtyards filled with altars; this contrasted with the traditional temple layout, where priests “wrapped the image of god in darkness and secrecy” (p. 262). Akhenaten also confiscated temple estates, where priests had become increasingly wealthy and powerful (White 1971 [1949] :246–248). Akhenaten and his court left the traditional religious capital of Thebes to build a new one, Akhetaten or “Horizon of the Aten” (known today as El-Amarna) (Kemp 1991:266–267). Akhenaten and his wife and consort, Nefertiti, were depicted as gods alongside the Aten as sole intermediaries, which further extended the pharaoh’s power (Kemp 1991:265). However,

…the Aten robbed Egyptians of a tradition of explaining the phenomena of the universe through an extraordinary rich imagery … which managed to contain the concept that a unity, a oneness, could be found in the multiplicity of divine forms and names. Akhenaten was telling the Egyptians something that they knew already, but in a way that made further speculation pointless. It is easy to understand why the Egyptians rejected the king’s religion after his death. He had tried to kill intellectual life. (p. 264)

Soon after Akhenaten’s death during his seventeenth year of rule, his successor, Tutankhamun, returned to “religious orthodoxy” and reestablished traditional temple cults and estates (e.g., Amun at Karnak) (Kemp 1991:267). Egyptians destroyed most of Akhenaten’s monuments and basically erased much evidence of his rule from history; when he was referred to, he was “that enemy from Akhetaten” (p. 267). Within 100 years, Akhetaten was abandoned (p. 272).

In contrast, successful political leaders incorporate existing “principles of legitimation” (Earle 1989) but do not expropriate them. For example, T’ang (ad 618–906) imperial rites in China originated from earlier dynastic ones (e.g., Chou, 1121–220 BC) that themselves derived from earlier ancestral cults (McMullen 1987). These Confucian-sanctioned rites were central to the T’ang political system for both its origin and continuance, especially in the face of increasing royal control over critical resources (cereal and rice fields) and increasing taxation. Everyone, though, continued to conduct domestic ancestral rites privately. Imperial ancestral ceremonies, however, were conducted publicly on a much grander scale. Chinese emperors replicated and expanded household rites but did not restrict or replace them. All members of society conducted similar ancestral rites—from farmers and local bureaucrats to the emperor—with increasing grandeur and scale. Of course, they added new elements to traditional formats (e.g., the fact that they have the mandate of heaven), which were accepted because of the familiar format used.

The successful application of acceptable family or domestic rites increases the prestige of sponsors and legitimizes political authority, including rulers’ monopolization of large amounts of land and their ability to acquire surplus from others (Bourdieu 1977:183–184, 1990:109–110; Cohen 1974:82; Giddens 1979: 1881–1895, 1984:257–261). Such rituals integrate larger numbers of people than the small-scale household or community rites from which they derive. For example, when Enga Big Men of precolonial Papua New Guinea became increasingly involved in external exchange networks, the growing wealth differences were situated within traditional ancestor and bachelor cult rituals (Wiessner and Tumu 1998:369).

When rulers sponsor public rites (e.g., feasts and ceremonies), they touch emotions (Bell 1997:73–74; Rappaport 1999:49, 226). Such feelings tend to dissipate afterward. Political actors thus use strategies that result in long-term benefits; key factors are content, repetition, and type of ceremony (Rappaport 1999:286), as well as the tangible symbols used (Helms 1998:166). Rulers typically associate themselves with rituals that revolve around vital elements of life such as rain, agricultural fertility, and ancestor veneration, conducted according to set schedules (ritual calendars) in special places (Cohen 1974:135). By directly associating themselves with natural forces of day-to-day life, rulers extend their influence beyond the duration of centripetal, integrative events.

Cross-culturally, rulership is associated with fertility, purification, and associated rites (Helms 1993:78–79). People believe rulers to have special powers (Ibn Khaldun 1967 [ca. 1382–1404]:319; Rappaport 1971, 1999:281; e.g., Geertz 1980:129–131); they are seen to have exclusive knowledge and skill and are viewed as closer to the supernatural realm (Friedman and Rowlands 1978; Helms 1998:74) or even as gods themselves. In time, they become directly involved in the continuity of natural forces (Frazer 1920 [1890]: 51, 245–247). For example, after the 1905 revolution in Russia, Tsar Nicholas II discontinued many public ceremonies, including the annual blessing of the waters. The people “believed that the prayers purified the water. They blamed the outbreak of cholera occurring from 1908 to 1910 on the suspension of the ceremony” (Wortman 1985:263). Similarly, in China the emperor played a major role in the regulation of the rivers; “… if the rivers broke the dikes, or if rain did not fall despite the sacrifices made, it was evidence—such was expressly taught—that the emperor did not have the charismatic qualities demanded by Heaven” (Weber 1964 [1951]:31).

Participation in public rites does not mean that people are automatons or that they are being hoodwinked; “acceptance is not belief…. Acceptance … is not a private state, but a public act” (Rappaport 1999:119–120; emphasis in original).

Symbols, rituals, emblems, and names are powerful sources of social integration even if the members of a group do not attach the same meaning, motivation, or interpretation to them. Individuals are united in a community because they share signs and rituals, but they may share these things without sharing their meanings. (Lee 2000:151)

Public ceremony promotes solidarity and a sense of community, which is critical as part of evolving political relationships. How audiences respond to royal events can determine how successful they are (Inomata and Coben n.d.) and also create a situation where people contribute to their own subordination (e.g., Joyce 2000, 2004). “Performances communicate on multiple sensory levels, usually involving highly visual imagery, dramatic sounds … [resulting in a situation where] one is not being told or shown something so much as one is led to experience something” (Bell 1997:160). Rulers put on a show when they perform traditional rites. Commoners thus are not passive witnesses but active participants with a voice (e.g., Bell 1997:73; Houston and Taube 2000). Their goal is to reach gods and ancestors on behalf of the people to bring forth rain, bountiful crops, and so on. Thus, commoners benefit by attaining access to socially defined value-goods handed out at special events (food, objects, etc.) (Pauketat 2000). In addition, nonparticipation might be perceived as antisocial or noncompliance and result in social sanctions (e.g., ostracism, accusations of sorcery, and refused access to local resources).

Religious nonconformity was an offence against the state; for if sacred tradition was tampered with the bases of society were undermined, and the favour of the gods was forfeited. But so long as the prescribed forms were duly observed, a man was recognised as truly pious, and no one asked how his religion was rooted in his heart or affected his reason. (Robertson Smith 1956 [1894]:21)

As illustrated by the T’ang rites mentioned above, however, domestic rituals never leave the home. Rulers replicate and expand them but do not replace or restrict them. People all participate in the larger-scale public ceremonies and their own small-scale private domestic rituals from which the former derived. Royal rites are superimposed on traditional ones (e.g., Godelier 1977:188), with new elements highlighting the special qualities of rulers (e.g., Chang 1983).

The fact that everyone, rich and poor, performs the same rites promotes solidarity and a sense of belonging (e.g., Bell 1997:123; Kertzer 1988:19). For example, in nineteenth-century Madagascar, all members of Merina society conducted new-year renewal ceremonies in which they called upon their ancestors to bless them (Bloch 1987). The same ritual bath was repeated in every household, from commoner to royal. These rituals, which took place at the beginning of the agricultural season, involved blessings from superior to junior, a feature that rulers expanded—from master to servant, ancestors to elders to children, father to son, to king to subjects. They not only served to legitimize authority but, more significantly, also provided a forum for advancing royal power, particularly after the often violent succession of a new king. In addition, gifts were presented from junior to senior, resulting in the king’s receiving large amounts of tribute. Palace layout, cardinal directions, sacred places, and objects were also co-opted by Merina royals to emphasize their sanctified right to rule and common ties with their subjects (Kus and Raharijaona 1998, 2000).

Eventually, these series of events often result in the development of centralized systems where kinship ties are replaced with nonkin ties that take on the appearance of kinship relations and are later replaced by nonkin ties where pretense no longer is required (Cohen 1974:24; Earle 1997:4–6; Godelier 1977: 123), though patrimonial rhetoric can still be used (Blanton et al. 1996). Additionally, once they have a certain degree of power, rulers can create completely new and different rituals without ties to the past for public as well as private or restricted consumption. For example, early Frankish kings in the Middle Ages were anointed with the same oil used to baptize the first Christian Frank, St. Clovis (Giesey 1985). The king’s first entrée into Paris was celebrated by enactments of the baptism of Clovis along his route. After 1550, however, the content of celebrations in Paris shifted to the king himself from earlier religious and historical themes. By the eighteenth century the entrée into Paris was dropped altogether, replaced by another set of rites revolving around the “cult of the Sun King.” In this case, traditional rites were initially replicated, then expanded, and later transformed. When French kings acquired enough power (e.g., a standing army), they could replace earlier rites with both public and private/restricted ones: “When a dynasty is firmly established, it can dispense with group feeling” (Ibn Khaldun 1967 [ca. 1382–1404] :314; emphasis in original). However, the French continued to conduct traditional Catholic rites in their homes and local churches.

What factors set in motion monarchs’ loss of power? Since the foundation of political power is surplus, long-term interference with surplus production and appropriation can and does bring down the political house of cards. Political elites lose their power because their rituals fail to reach the gods. Before addressing this question further, I define political collapse.

Demise of Political Power

Dynasties have a natural life span like individuals.

IBN KHALDUN (1967 [CA. 1382–1404]:343; EMPHASIS IN ORIGINAL)

George Cowgill (1988) has defined various types of collapse. In most cases, it involves “political fragmentation” whereby politically unified systems break down into their constituent parts (e.g., Mesopotamia, India, Egypt, and the Roman Empire). Great traditions, however, typically persist, as they did for long periods in Roman territories, Egypt, and Mesopotamia. Replacement also occurs, whereby new governments replace previous ones for various reasons, as was the case in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and France. In rare cases people abandon a region, as in some areas of the southern Maya lowlands and likely parts of southern Mesopotamia (Cowgill 1988; Tainter 1988:191). It is also rare when a political vacuum remains empty, which was the case in the southern Maya lowlands in the Terminal Classic period.

Norman Yoffee (1988) calls for a distinction between the collapse of “states” and the disappearance of “civilizations.” In the former case, the political economy fails, resulting in a reversion to prestate organization or the replacement of one political hierarchy by another. For example, while centralized political systems of Egypt have changed hands for millennia, their subsistence base (the Nile and alluvium) has remained stable through present times (Kemp 1991:10–13). In the latter case, it is the disappearance of “great traditions,” including writing systems and elite and royal symbols and monumental architecture. For example, Yoffee (1988; Baines and Yoffee 1998) details how variously sized political fortunes changed hands several times during the millennia but shows that the Mesopotamian “great tradition” persisted long after Mesopotamian political systems were replaced by foreigners in ca. 539 BC (Cyrus of Persia) until at least ca. AD 75.

Joseph Tainter (1988) also notes that collapse is not necessarily catastrophic, especially for the majority of people; usually only people in the upper political echelons and administrators are affected by political disintegration. Furthermore, collapse can be an adaptive mechanism when, for whatever reasons, the current system no longer works (p. 198). It is typically political histories that change or disintegrate, rather than traditions; the majority of people are rarely put out since, as mentioned above, political systems are superimposed on existing social and economic institutions, which typically long survive political systems. For example, based on their work at the Zapotec regional center of Río Viejo, Oaxaca, Mexico, Arthur Joyce et al. (2001) posit that nonelite farmers, if they did not have a direct role in the demise of the political elite, definitely made their feelings known after rulers fell from grace at the end of the Classic period. They reused royal monuments as building materials and subsistence tools (e.g., metates) and built their homes on the former royal acropolis.

For purposes of this study, a collapsed society can be defined as one that is “suddenly smaller, less differentiated and heterogeneous, and characterized by fewer specialized parts; it displays less social differentiation; and it is able to exercise less control over the behavior of its members” (Tainter 1988:38; emphasis added). The latter part of this statement is particularly significant—losing access to the labor of others, the reasons for which become apparent throughout this work.

Climate, Resources, and Political Histories

…a Prince who rests wholly on Fortune is ruined when she changes.

MACHIAVELLI (1994 [1514]:81)

In a fascinating series of studies, Carole Crumley (1993, 1994, 1995a, 2001) convincingly argues that the height of Roman power in Europe was facilitated by a stable climate pattern that favored an urban-rural lifestyle. This climatic period (ca. 300 BC–AD 250), called the Mediterranean climatic regime, consisted of hot and dry summers and rainy winters. Climate prior to this period was cooler and more seasonally unpredictable. Crumley suggests that the unstable climate episodes required more flexible subsistence, social, and political strategies, like those found before 300 BC in Celtic Europe. The Celts practiced agropastoralism, were somewhat mobile, and had a loose social structure. During Roman hegemony, also known as the Roman Climatic Optimum (300 BC–AD 250), the stable climate “facilitated urbanization [and] the homogenization of the landscape through the commoditization of rural produce …” (Crumley 1994:198) and sustained relatively “inflexible forms of governance” (p. 192), resulting in what Crumley (1995a:26) refers to as an “ecology of conquest.” Climate change, when more unpredictable and cooler seasons predominated beginning in the late second century ad, resulted in consistent crop failures, hailstorm damage, and blight (Crumley 2001). The Roman Empire depended on agricultural surplus to feed the people of Rome and to fund the political economy. The loss of surplus resulted in the rug being pulled out from under Roman hegemony, a process exacerbated by other events of the time (e.g., foreign invasions). Finally, Celtic peoples, now free from Roman demands, did not and could not revert to the life they had led before 300 BC; different circumstances existed, much history had passed, and much knowledge about the natural landscape had disappeared, setting the stage for serfdom (Crumley 2003).

The period after the fall of the western Roman Empire became known as the Dark Ages (AD 400–900) (Gunn 1994), which really meant that there were not many written records, since the recording of dynasties, royal events, tribute lists, and so forth was unnecessary. The Dark Ages were followed by another favorable climatic regime (favorable for surplus production and appropriation, anyway), known as the High Middle Ages (AD 90–1250). Population “plummeted” in the Late Middle Ages (AD 1250–1450) with the “return of cool and moist summers” (Gunn 1994:94). Interestingly, Joel Gunn (1994:95) notes that when “Europe is blossoming, the Mayas retire to subsistence agriculture”—at least in the southern lowlands.

While the scenario in Europe might appear to hark back to formulaic cultural ecology (warmer, stable climate = inflexible political systems; and cooler, variable climate = flexible political systems), it does make sense in light of the available evidence, especially when taking into account historical and social factors. For example, community organizations, with flexible sociopolitical organization and plentiful resources, could more easily adapt in the face of climatic change. The same could not be said for centralized and integrative polities, which are less politically flexible. Local polities fall somewhere in between; consequently, specific historical circumstances largely determine their fate. In other words, different trajectories are set in motion by changing climate (e.g., Fagan 2004). The more powerful and inflexible they are, the harder they fall in the face of long climatic perturbations. While political systems may fail, fragment, or be replaced, average commoners are working to adapt their subsistence and settlement practices to changing conditions, a strategy that has been in place since the dawn of humanity.

Climate change also exacerbates other existing problems. For example,

…the Sumerian, Akkadian, and subsequent civilizations in the Tigris and Euphrates River Basin in present-day Syria, Iraq, and western Iran, and the Indus, or Harappan, civilization in the Indus River Basin in present-day Pakistan and western India were all negatively impacted by deforestation, overgrazing, and salinity built up from long-term irrigation. (Hardesty and Fowler 2001:79)

These factors affect surplus production and hence political systems. Farmers in ancient Egypt did not have to face the problem of salinity, because “after the harvest in summer, the ground dried and cracked, enabling aeration to take place, which prevented water logging and the excessive accumulation of salt” (Kemp 1991:10). Since their political foundation was based on surplus fruits born of the Nile, however, inadequate flooding during dry years spelled trouble for pharaohs when famine and plagues spread throughout the land. Fekri Hassan (1994) plots the relationship between climate and political history and notes that periods of political instability largely resulted from low floods and drought. Dynasties weakened or failed altogether. Egyptologists refer to these times as intermediate periods.

A well-known biblical story emerged during one such period: the story of Joseph in the Book of Genesis (41–47). Several scholars place the story in the early part of the Second Intermediate period (1640–1540 BC), when Hyksos ruled Egypt for a time (Bright 1981:87). In the story Joseph, originally brought into Egypt as a slave, successfully interprets the pharaoh’s dream signifying seven years of plenty followed by seven years of famine. Forewarning allowed the pharaoh to stockpile grain and thus be prepared when annual floods were inadequate and famine eventually spread throughout the land. In the first year of famine, people gave “money” and livestock in exchange for food. In the second and following years, when people’s money and livestock were depleted, the people handed over their land and offered their labor in exchange for food and access to land they formerly owned. They still farmed the land they once owned but now owed a fifth of the crop to the pharaoh. I am sure that if the famine had lasted longer, eventually even the pharaoh’s stockpile would have dissipated. They might have been able to feed their people with food acquired via trade, but eventually the surplus they needed for exchange would be depleted, as would their political power. Clearly, while climate change can result in political instability, it can also benefit the political savvy under certain conditions.

These examples clearly illustrate the critical role that climate patterns and change played in subsistence and political systems. How do these factors affect different political systems?

Communities and local polities are typically more stable and durable than centralized and integrative polities because they rely less on large-scale subsistence technology and rulers’ capital and food stores and make fewer demands on resources. Nonetheless, in all situations there are circumstances that are beyond their control. The more flexible their social and political system, however, the better people can deal with, for example, changing climate or other drastic changes.

When noticeable change does occur, for whatever reason, it can affect political systems in various ways—they can fragment into their constituent parts, or governments can be replaced from within or with external forces (Cowgill 1988).1

Ritual and Political Collapse

Rituals are performed in all societies, whatever the political system. As Arthur Hocart (1970 [1936] :35) aptly notes, rituals existed long before governments. In community organizations elites sponsor feasts, performances, and religious rites and organize small-scale projects (e.g., building religious structures, terraces, and canals) to promote solidarity in the face of wealth differences. Household rites involve ancestors and fertility, both critical to their survival. In local polities, chiefs perform rituals in public arenas that involve chiefly ancestors as descendants of gods, as well as agricultural fertility, rain, and war gods. All members conduct similar rites in the home and community. In centralized and integrative polities, royal rites revolve around royal ancestors and the fact that they have the “mandate of heaven.” Rulers conduct elaborate ceremonies and feasts in monumental settings including temples, stadiums, and arenas to attract and keep followers. Ceremonies also acknowledge the importance of other gods, especially those in the upper echelons of the supernatural hierarchy. Household and community rites continue to revolve around ancestors and traditional deities concerned with rain and crops. They are still quite important, especially since farmers are relatively economically self-sufficient and thus must rely more on their own ceremonies. Rulers, however, are the major players in reaching the supernatural world and highlight the perception that the continuance of their rule results in prosperity for them all.

In all political systems, ritual never leaves the home; and when rulers disappear or political dynasties are replaced, people continue to conduct the same rites in the same places they had since before the emergence of political leaders. Nor is there any doubt that ritual is critical for political power and survival. Rulers who associate their rule with the supernatural are successful in times of plenty. When food and/or water supplies diminish to the point where people are materially affected, however, rulers are the first to be blamed when their ceremonies fail. Clearly the gods no longer support rulers (Frazer 1920 [1890] :352; e.g., Helms 1998:168; Kaufman 1988). This failure might result in last-ditch efforts to reach the gods through even more elaborate rituals, which might actually hurt the system even more if surplus is being used to fund ceremonies rather than feed people.

Political power thus lasts as long as rulers demonstrate that their ceremonies successfully propitiate supernatural entities (Hocart 1970 [1936]:142–155). When they cannot, there is no longer any reason for farmers to contribute to political coffers:

… beliefs vindicating the power of rulers also became limits on their power. If they ruled because they enjoyed the approval of forces greater than they, or because they were wiser or more virtuous than their fellows, it followed that evidence of supernatural disapproval, or of folly or vice, vitiated their claims to general obedience. Gradually, the doctrines that conferred on them the ability to elicit obedience came in some cases to justify insubordination and even rebellion. Indeed, in time, the doctrines not only permitted such resistance to undeserving rulers; they were sometimes held … to mandate it. The security and power of the inner governing circles were thus weakened by the very principles that had once blocked challenges to their ascendancy. (Kaufman 1988:226–227; emphasis in original)

For example, in China there is evidence as early as the Chou dynasty (1100–256 BC) of a “heaven’s mandate” that related to whether or not kings were successful (Chang 1983:34). “[P]olitical dynasties fell because the king misbehaved and no longer deserved to rule…. The dynastic cycles … have nothing to do with the rise and fall of the civilization; it merely signifies the shifting political fortunes of specific social groups whose rulers gain or lose their claim to the moral authority to rule” (Chang 1983:35). A similar situation existed in Bali; J. Stephen Lansing (1991:109) discusses how temple priests and princes could lose the mandate of heaven if they were unable to amass the necessary labor and goods to sponsor large-scale rituals, which they could not do when water supplies were low.

The point is this: the power of rulers is closely tied to divine support, a relationship maintained through ritual and funded through surplus. When support is removed, so is their power.

In the next section I present a possible scenario as to the process of how political rulers emerge, how the majority of people participate in the creation of political obligations, and how political power is lost. The following scenario can (and does) occur at any time and place and serves as the framework for the present study.

A Scenario

History repeats itself.

In cases where farmers migrate to previously uninhabited areas (versus the autochthonous emergence of a farming lifestyle), first founders eventually distinguish themselves from newcomers by building larger houses and acquiring exotics. Everyone performs the same rites; elites, however, use more expensive items as offerings—they can afford to relinquish them forever. Elites compensate workers with prestige items, food, and/or access to resources. Workers must be well paid since they could choose to work for other elite families. Patrons sponsor ceremonies and feasts for workers, their families, and the entire community to show their gratitude and to attract more clients. These events provide a break from work, a time to socialize, and opportunities to exchange information and goods. Public ceremonies and feasts also provide elites a chance to increase their prestige in the eyes of farmers and other elites who compete for labor and prestige. Finally, these events allay conflict in the face of socio-economic differences.

This story has been repeated again and again throughout time and space. The question becomes, when and how does equal compensation (choice) transform into tribute extraction (little or no choice)? That is, when do wealthy individuals or elites become rulers? When and how do patron-clients become ruler-subjects? Where necessary material conditions do not exist, of course, these questions are moot. But when they do, and historical circumstances are just so …

Initially, extensive farming provides enough food for everyone. Later, as more and more people move into any given area and population grows, farmers start to invest more effort and time in intensive strategies to produce greater yields. Kinship groups no longer can resolve disputes over land and water allocation since they often involve nonkin interactions. Nor can farmers protect themselves from outsiders without organized assistance. A greater reliance on domesticates makes farmers more vulnerable and dependent on rainfall, especially in the face of seasonal flood damage and drought. Elites with larger land-holdings typically have more stored foods, which they dole out in times of need. Emerging leaders do not provide these services for free. Ambitious people realize that they can demand payment for use of their services, above and beyond what could be defined as equal compensation. Some acquire large landholdings—corporate or otherwise—from hungry or thirsty people who then become tenant farmers. They have to be careful, however, not to demand too much, or farmers could flee; in other words, farmers do have some leverage.

Leaders’ chances are enhanced in areas with noticeable seasonal issues or problems. The story of Joseph in the book of Genesis illustrates this point quite well; after the seven-year famine, the pharaoh owned many means of production—in this case, fertile land. And this story is repeated again and again throughout history. When circumstances become favorable again, it is clearly due to rulers’ successful supplication of gods and ancestors, which they do in increasingly grand forums by performing traditional rites and funding grand ceremonies and feasts (“bread and circuses”). These events provide a break from the hardships of daily survival and opportunities for leaders to illustrate their success in the eyes of their clients and fellow patrons. If famine lasts too long and food stores run out, however, people no longer can rely on rulers’ ability to reach the gods.

A leader’s success keeps people paying and keeps attracting others, including people who are persuaded to leave rival factions. To further increase the number of tax-paying members, political leaders use surplus acquired from others to support military incursions into neighboring polities; the goal is to conquer for access to more land and labor, not to kill people per se (other than enemy leaders, of course). More people require more food and water, and consequently they further rely on intensive agricultural regimes. While leaders may not own such systems or organize their actual construction, they do provide capital to rebuild them after damage caused by, for example, flooding. During famine, they also open their storage facilities, filled to the brim with food from their fields or from trade. Again, these services are not provided for free. Leaders continue to sponsor integrative events in large arenas to promote solidarity and a sense of belonging. Traditional rites writ large include new elements that highlight ruler’s ability to reach the gods. Leaders also perform new rites that revolve around royal families for both public and private viewing.

Eventually, one powerful ruler arises above others in an area where seasonal fluctuations in water and food supplies exist and where people rely heavily on large-scale water/agricultural systems—as well as the plentiful agricultural land that supports their lifestyle and subjects. Farmers by this time do not have many options but to pay taxes. Avoidance and resistance are met with force. Blatant coercion, however, is unstable and potentially politically dangerous. Rulers must offset any negative feelings about their power over others by providing protection, food, and capital and sponsoring grand events. But commoners have to get something in return for their tribute (e.g., protection, capital, acknowledgement of social membership, or food and water in times of need). Maintaining a balance is the challenge. If demands are too much, farmers flee to a rival kingdom or, if possible, flee political demands altogether and live in more marginal areas. If demands are inadequate, rulers cannot fund the political economy.

Rulers distinguish themselves from others not only through living in palaces and owning a plethora of wealth items but also through having skilled artisans copy their likenesses onto public and private media—from rollout stamps and coins to massive and grandiose sculptures and buildings. Often kings make sure they are depicted alongside gods as if they, too, are divine. Everyone participates in ceremonies that revolve around the royal family to celebrate their divine or special status. Such rites are superimposed on traditional ones that everyone continues to perform, royal or not. They also integrate a large enough number of followers to require a recording system to keep track. If writing does not develop for economic matters (trade and taxes), it emerges to rewrite history to place rulers and their families in a better light than reality post hoc facto—that is, they successfully outcompete other elite families, who then become enemies, administrators, and/or local representatives.

All good things come to an end, however—the more monarchs depend on surplus provided by others for their bread and butter, especially in the face of seasonal vagaries, the more vulnerable they are to changing material conditions. As Crumley demonstrates, inflexible political and subsistence systems are less able to adapt to changing conditions. Rituals no longer work, and rulers fail in their supplications to supernatural entities. Close ties to the otherworld have pros and cons; pro when rain and food are plentiful, and con when they are not. Of course, farmers blame the ruler. After a king falls from grace, elite and nonelite farmers continue to conduct the same rites they always had before and during the appearance of rulers, which remained geared to surviving in a changing world.

Concluding Remarks

The approach taken in this work bridges the gap between studies on the emergence and demise of rulership by focusing on two factors—water and ritual. I attempt to show how emerging Maya rulers expanded family-scale rites (especially dedication, ancestor veneration, and termination rituals) into larger communal ceremonies as part of the process that drew seasonal labor from farmsteads to centers. This system worked for nearly a millennium. What happened to cause farmers to abandon their rulers? Why did rulers eventually fail to convince farmers to pay homage in the form of surplus goods and labor? The remainder of this book seeks to address these questions.