In this chapter I describe centralized and integrative polities (see Table 1.1) and river and nonriver major Maya centers, which have several factors in common (see Table 2.1). I also present a history of ritual activities at Tikal, home to some of the most powerful Maya kings.

Centralized Polity

When Anu and Enlil [major gods] gave me the lands of Sumer and Akkad to rule, and entrusted their sceptre to me, I dug the canal Hammurabi-the-abundance-of-the-people which bringeth water for the lands of Sumer and Akkad. The scattered people of Sumer and Akkad I gathered, with pasturage and watering I provided them; I pastured them with plenty and abundance, and settled them in peaceful dwellings.

HAMMURABI (CA. 1792–1750 BC), TRANSLATED IN RUSSELL (1938:77)

A centralized polity is politically centralized, integrating several local polities and communities. It is largely based on a ruler’s access to concentrated critical resources and concomitant nucleated, dense settlements (e.g., river valleys) (Carneiro 1970; Earle 1997; Friedman and Rowlands 1978; Gilman 1981). Examples include several ancient complex polities that arose along rivers, where leaders more easily controlled access to waterways and/or concentrated alluvium, as well as the labor of surrounding farmers who lived in farmsteads, communities, villages, or towns (e.g., China, Egypt, Mesopotamia, parts of Mesoamerica, and coastal Andean South America). Political demands are superimposed onto existing economic and social institutions. Centralized polities are what anthropologists have traditionally defined as archaic states (e.g., Marcus 1998). They have dense populations (e.g., urbanization), institutionalized rulership with power over life and death of subjects, the ability to collect tribute and raise an army, centralized storage and/or stores of capital, socioeconomic stratification, occupational specialization, specialized personnel (military, religious, and administrative personnel or bureaucrats), interdependency (e.g., protection, reliance on large-scale water/agricultural systems), and, secondarily, writing or recording and codified laws (Adams 1966; Carneiro 1970; Childe 1951 [1936] : 114–120; Engels 1978 [1884]; Fried 1967:229–240; Marx and Engels 1977 [1932]; Service 1962:180; Steward 1972 [1955] :191–196; White 1959:141–147).

Lineages, clans, or comparable groups corporately own land (Trigger 2003: 320). The largest landholders, however, are monarchs, temple estates, and aristocratic families (p. 333). While farmers typically are largely economically self-sufficient (pp. 112, 402), they—along with urban dwellers—face periodic drought, famine, and damaged crops and water/agricultural systems resulting from heavy rains. Rulers provide food from their granaries or via trade and capital to rebuild water/agricultural systems (cf. Trigger 2003:387). They also allocate water and/or resolve disputes involving water rights and protect subjects and their property from raids and invasions.

Sociopolitical relations are hierarchical and unequal, though kings have to take care not to over-exploit their subjects. Inequality results from rulers’ being able to exact tribute without any obligation to compensate subjects equally. Military support is for protection from foreign threats, but, more importantly, to conquer land and incorporate more people. The presence of an army indicates that rulers could coerce compliance from farmers to pay their share in maintaining the political economy. In other words, farmers had less choice and fewer options but still resisted when they could, usually in subtle ways, with what Scott (1990) labels “hidden transcripts.” For example, taxpayers express discontent and resistance through jokes, folktales, songs (p. 19), role-reversals (e.g., Carnival) (pp. 80, 173), and poaching (p. 190) and stealing from royal or elite lands.

Monarchs participate in the royal interaction sphere, including alliances, marriages, and prestige-goods exchange. Large-scale integrative events (e.g., trickle-down of exotics, ceremonies, and feasts) are necessary to legitimize rulership and promote solidarity. Corvée labor is used to build both public (e.g., stadiums) and private/restricted buildings (e.g., palaces). All members of society participate in trade independent of elite interference, either between individuals or in markets.

Regal rites revolve around royal ancestors to illustrate that they have the “mandate of heaven” (Fried 1967:238; Helms 1998). Ceremonies also acknowledge the importance of other gods, especially those in the upper echelons of the supernatural hierarchy. Rulers, because of their role in the continuance of life and society, are depicted in public iconography, often alongside powerful gods (e.g., sun and water deities), on various media from small objects (e.g., coins) to large public buildings (e.g., temples) (for example, Durkheim 1995 [1912] : 64). Everyone conducts household and community rites, which revolve around ancestors and fertility. Writing or recording systems typically emerge to record important information, including economic transactions, dynastic histories, religious rites, and myths (Postgate et al. 1995).

Centralized polities last as long as resources hold out and seasonal regimes do not change drastically for long periods. Demand for surplus production instituted by monarchs may contribute to the over-exploitation of resources, a condition that can be exacerbated by changing climate patterns. “Evidence of resource degradation is more common in periods when hierarchical, centralized polities held sway, even when overall population density in the polities was not much greater than in periods when non-centralized societies were in charge” (Roosevelt 1999:14). For example, the increased salinization of irrigated land in southern Mesopotamia likely contributed to the loss of political power, critical resources, and people in and around urban areas in the eighteenth to seventeenth centuries BC (Jacobsen and Adams 1958; Postgate 1992:181; Yoffee 1988). However, as mentioned, it is a rare occurrence when regions are largely abandoned.

I illustrate a centralized polity through a brief description of one of the “largest desert areas in the world” (Kemp 1991:8), Egypt during the New Kingdom (1540–1070 BC). Egyptians lived along the Nile River, a rich, fertile area replenished each year during annual flooding. Intensive agriculture, as well as the herding of cattle (and sheep and goats) and the capture of riverine life (fish and fowl), supported densely settled villages, towns, and cities (including temple towns) (Baines and Yoffee 1998). Since farmers depended on the annual rising and subsiding of the Nile for their livelihood, famine was always a concern, caused either by drought or by flood damage (Hassan 1994). Canals and earthen embankments (dikes) diverted water to fields, which were built under both local and government supervision. By the New Kingdom, the shaduf was introduced, a water-lifting device that expanded available farmland. Potential food shortages were mitigated by the use of granaries, which pharaohs, temple estates, and wealthy individuals built and stocked (Kemp 1991:296). In addition, many residential compounds had wells.

Stratification was undeniable, in terms of both wealth (palace, temple, and noble estates) and political power, with the pharaoh ruling from the top and with various high officials and temples priests vying for wealth and power. The pharaoh owned large amounts of land, as did temple priests, officials, and wealthy families. Elites also owned the ships vital for trade. However, everyone owed tribute to the pharaoh. In addition, the royal household controlled the vast wealth from conquered lands, including, for example, gold from Nubia. Pharaohs supported a standing army as well as foreign mercenaries to conquer rich areas and to protect their people and territory from invasion (Kemp 1991: 228). Egyptians had access to trade and other goods in the markets as well as through local exchange independent of royal supervision (p. 259).

Monumental architecture was closely tied to religious and political venues, including temples that housed divine images and royal tombs that served as royal ancestral cults (Kemp 1991:21, 53), both of which collected tribute (p. 235). In addition, each deity had its own temple and priests, all of whom vied for material support. At the household and community level, rites revolved around ancestors at family tombs and various deities from the vast pantheon of Egyptian gods. Villages also commemorated “the gods they favoured” (p. 304) (e.g., Amun, Amun-Ra). If able, elites built small shrines in their garden in honor of the royal family (p. 301). Royal and religious rites were grand public affairs to celebrate and honor gods as well as the divine ruler. The importance of gods and the pharaoh is also reflected in public iconography, which is dominated by the inscribed life stories of gods and rulers, conquests, and festivals, not to mention the annual height of the Nile flood (Kemp 1991:23). The relationship between king and deities and the cosmos was also detailed in the written record.

Political power has changed hands numerous times throughout Egypt’s long history, but it has always been densely settled and is still going strong today.

Integrative Polity

To be a god does not necessarily mean to have more license, but rather to have more duties: divinité oblige.

HOCART (1970 [1936] : 151–152)

A major difference between centralized and integrative polities is that the former exhibit greater centralized and hierarchical power structures, whether they are city-states (e.g., Mesopotamia), territorial states (e.g., Egypt), or empires (e.g., Inka). One system gives the appearance of a unified front through high culture (i.e., civilization) (Baines and Yoffee 1998), and the other actually is more politically unified. The confusion has arisen when scholars conflate civilization and the state (Yoffee 1988). A civilization shares a “great tradition” or an elite and royal culture. Centralized polities have one primary ruler, whereas integrative ones have several relatively autonomous ones. In integrative polities, periods of centralization, if any, are brief; but they have a common political ideology expressed via monumental iconography, writing, and royal public rites. Marcus (1998) mentions some of these factors in her dynamic model. While she argues that most archaic states go through cycles of centralization and decentralization, I argue that in many instances periods of decentralization are a normal state of affairs for integrative polities (cf. Demarest 1992; Feinman 1998). In some cases “success” (centralization) is achieved, but usually only briefly or not at all (e.g., Angkor and the Classic Maya).

Another major difference between centralized and integrative polities has to do with the material basis for political power (see Table 1.1). Unlike in a centralized polity, it is more challenging for kings of integrative polities to access completely the dispersed critical resources, resulting in a decentralized subsistence economy (e.g., Fox 1977:54; de Montmollin 1989:17–19; Kunen n.d.). As a result, farmers live in farmsteads or villages scattered throughout the landscape, making it difficult for leaders to bring people together to organize work parties, feasts, and ceremonial events (e.g., Java; Miksic 1999). Integrative polities also lack large-scale and centralized storage facilities—for food, at least; water storage and allocation is another matter. Without centralized storage, rulers cannot assist their subjects in times of need, unless they have the means to import food. Hereditary rulers, however, still involve themselves in supporting large-scale water/agricultural systems, which are critical in the face of seasonal concerns such as drought, floods, and water allocation. Other economic systems, such as trade, also can be garnered to support rulership. But monarchs bring people together, for example, in regal-ritual centers (Fox 1977) by sponsoring elaborate ceremonies and feasts at monumental temples, temple-palace complexes, stadiums, and arenas. The goal is to create obligatory relationships and impose taxation on those who congregate at royal centers.

The population of the city consists of those bound to the court by kinship, official duties, or craft specializations…. The life-style is defined by the calendrical round of state rituals, kingly ceremonies, coronations, funerals, preparations for war, royal feasts, and divine sacrifices, rather than by individualism and secularism. (Fox 1977:53)

Consequently, competition exists among rulers to attract and keep followers. Of course, everyone still performs household and community rites. Rulers, however, are better able to communicate with the supernatural world and highlight their contention that the continuance of their rule benefits everyone.

Kings are depicted in the iconography to emphasize their ties to gods, especially sun and rain or water deities. This relationship is often recorded via carved inscriptions for all to see but not usually to read and comprehend. Writing systems do not record economic transactions as much as they do royal and supernatural events (cf. Postgate et al. 1995). Rulers still need funding, however, to support the political system. When possible, they amass an army to incorporate more labor and for protection, though coercion is politically unstable (Earle 1997:7–8; Scott 1990:109; Trigger 2003:222). Warfare typically thus is small-scale and ceremonial in nature, often related to status rivalry (Webster 1998; e.g., Geertz 1980:252). Nor do they have much of a bureaucracy, if at all (e.g., Geertz 1980:132). Rulers are heavily involved in a far-flung royal interaction sphere to bolster their rights of power over others (e.g., Helms 1993). In addition, while they cannot force compliance, people often listen to their advice because of what leaders provide in return. For example, when corporate kin groups no longer can resolve disputes involving nonkin members, rulers can adjudicate intergroup problems (e.g., water and land disputes) (Hocart 1970 [1936] : 133). The king thus is a lineage elder writ large.

“Galactic polities” of Southeast Asia (Tambiah 1977) exemplify such a system, the traits of which are summarized by Arthur Demarest (1992:150):

The most salient characteristic … is the great importance of ritual performances in their ceremonial centers and the awe (and authority) that these displays generated…. Other important features include (1) the organization of hegemonies into capital centers loosely controlling a cluster or galaxy of subordinate centers; (2) a redundancy of structure and functions between the capital center and dependencies; (3) an emphasis on control over labor and allegiance rather than territory; (4) little direct control by the rulers over local economic infrastructure; (5) an extreme dependency on the personal performance of the ruler in warfare, marriage alliances, and above all, ritual; and (6) the tendency of these states to expand and contract in territory, reflecting the dynamics resulting from all of these features, as dependencies struggle against authority or shift allegiances or as expanding capitals impose short-lived attempts at centralization.

Another noticeable feature of integrative polities is the degree of leverage that farmers have over ruling elites, which is more than in centralized polities. Michael Adas (1981:218), based on his research on precolonial and colonial Southeast Asia polities, argues that political power actually

... is in reality severely restricted by rival power centers … by weaknesses in administrative organization and institutional commitment on the part of state officials, by poor communications, and by a low population-to-land ratio that places a premium on manpower retention and regulation.

In precolonial times, rivalries existed among elites for labor control as well as the rivalry between rulers and regional lords. Marriage alliances served to cement ties between elite/royal families and benefited both sides. Further, since administrators “at all levels” kept a portion of taxes collected rather than being paid a salary per se, institutionalized corruption was rampant. Monarchs also found it difficult to control much beyond the capital city and hinterlands, especially at the village level. They found it challenging to compete with village headmen. Village headmen in Java and Burma, for example, generally came from local elite landholding families, who usually claimed to be descended from founding families:

Their control over local affairs rested on the extent of their holdings, the number of laborers and artisans dependent on the use of their land and their patronage, the wisdom they demonstrated in village councils, and their ability to defend the interests of their communities in dealings with supravillage officials and their agents. (p. 222)

In Java:

Most of the remaining families in the village were attached as clients, with varying degrees of dependence, to one of the [elite] households. The clients … worked the [elites’] fields for a customary share of the harvest yield, performed domestic and artisanal services, and in some cases actually lived in dwellings provided by their patron. (p. 226)

Kings could not do much about this situation because of the lack of a military force powerful enough to guarantee compliance. Elite officers commanded troops of poorly trained and equipped conscripted peasants. It was also difficult to control regional lords and collect taxes, not to mention organize large-scale labor-intensive projects.

Thus, precolonial rulers were compelled to rely mainly upon adherence to state cults centering on the ruler’s powers to protect and to grant fertility, on chains of patron-client clusters extending from the court to local notables, and on the cooperation of village leaders, rather than on military clout, to ensure that taxes were collected and order maintained. (p. 223)

These conditions in precolonial Southeast Asia, in turn, provided the means for farmers to avoid excessive demands through several strategies, which rarely included outright revolt and violence. It was not usually necessary in the face of other options farmers had. They migrated, chose other patrons, or fled to temple estates/monastic orders or to rival kingdoms. Farmers could always return if rulers or patrons lessened their tribute demands. Since the success of patrons (royal or not) was based on their prosperity—brought to them through the labor of others—attracting and keeping laborers was critical. Patrons thus had to demand enough taxes and labor to demonstrate their success without making the demands too onerous. Clearly, farmers had leverage, since the loss of labor was detrimental to royal and noble power and prestige. Consequently, competition for their loyalty and labor was intense. “The flight of the peasantry came to be seen in most African and Asian cultures as a sign of dynastic weakness and socioeconomic decline” (Adas 1981:234). Monarchs traveled throughout their domain to interact ritually with their subjects.

An integrative polity is thus less politically integrated than centralized polities because material wealth is inadequate in and of itself to support the political system, as are integrative events. Consequently, rulers must continually maintain their power through feasts, ceremonies, and elaborate displays. This system consequently is more susceptible to any type of fluctuation—climatic, economic, political, or social. As long as resources and climate regimes are stable, however, the economic system is relatively stable or unaffected by cyclical or changing political histories.

I illustrate an integrative polity through a brief description of nineteenth-century Balinese kingdoms. Wet rice intensive agriculture supported the entire population but not political power per se, since individual “irrigation societies” (subaks, consisting of up to 100 farmers) were economically independent and self-sufficient and crosscut dispersed hamlets or residential units (Geertz 1980 : 50; Lansing 1991:4). The island of Bali is covered with rivers, streams, springs, and rich agricultural land but has no urban centers. Water is scarcer in the north part of the island (Hauser-Schäublin 2003). Water allotment was crucial, since farmers relied on the “seasonal flow of rivers and springs” (Lansing 1991:38) during the five-month rainy season. Priests at water temples found throughout Bali allocated water, which was staggered and couched in ceremonial proceedings (Geertz 1980:82; Lansing 1991:117–118). This system was critical, since up to 100 subaks relied on the same river (Lansing 1991:4). Husked rice was stored in storehouses built by subak members (Hauser-Schäublin 2003). Various forms of clientship existed: between higher and lower ruling lineages, between ruling and priestly lineages, and between ruling lineages and communities (Geertz 1980:34, 37–38). The irrigation systems, consisting of dams, canals, dikes, dividers, tunnels, aqueducts, reservoirs, and terraces, were owned by subaks (Geertz 1980:69), though the land was owned by the gods (p. 128); and “the king was represented as the prime ‘guardian,’ ‘custodian,’ or ‘protector,’ ngurah, of the land and its life …” (p. 129). While there was no bureaucracy per se, there was an official (perbekel) who served to link hamlets to kings (Geertz 1980:54).

Several kingdoms competed for tribute. For example, in the nineteenth century the Dutch recognized eight kingdoms (Lansing 1991:17). The Balinese participated in foreign trade with other Southeast Asian countries to acquire exotics. People also acquired goods at local, regional, and large rotating markets (Hauser-Schäublin 2003). Kingdoms were funded by clients, rent, trade, and taxation, in exchange for which farmers could use agricultural land (Lansing 1991:31, 103). Labor obligations also were owed to the king (p. 27). In addition, each temple implemented tribute demands in exchange for their services in keeping the water flowing (p. 107). Politics particularly came into play when temples competed for tribute, especially during the dry season and/or during drought, when temples were not “working” and rival temples claimed that they could provide the needed water (pp. 107–108). Competition also existed between temple priests and “princes” (p. 90). Sometimes competition escalated to war, which, according to Clifford Geertz (1980:256), consisted of a “series of brief lance and dagger skirmishes” with few casualties. Warfare clearly had a ritual aspect to it.

Bali had six great (regional) water temples (Geertz 1980:40; Lansing 1991: 44); in addition, each subak maintained a water temple (Lansing 1991:81). And of course each palace had a temple (p. 109). Each temple had a god, and these gods controlled water and irrigation (Lansing 1991:53). Water and fertility rites took place at all temples, with increasing grandeur and scale (Geertz 1980:40). “[A]ll traditional Balinese social units, from households to kingdoms, possess their own altars or temples, where regular offerings are made to the gods concerned with their affairs …” (Lansing 1991:50). “Ancestor shrines for commoners may have from one to three meru roofs, high-caste aristocrats, five or more, with the highest rank of eleven roofs reserved for consecrated kings” (Lansing 1991:71). Royal ancestors were important in the lives of all Balinese and were acknowledged in various rites (Hauser-Schäublin 2003). The importance of gods was reflected in the iconography, where major Indic (Hindu-Buddhist) gods (e.g., the supreme god, Siva, or the sun god, Surya), as well as traditional gods, were represented (Geertz 1980:105; Lansing 1991:63). Kings were also represented in the iconography, and they left inscribed edicts throughout the land detailing settlement and temple borders, royal regulations, and required offerings for particular shrines and temples (Hauser-Schäublin 2003).

The king himself was a “ritual object” (Geertz 1980:131). “The extravagance of state rituals was not just the measure of the king’s divinity … it was also the measure of the realm’s well-being. More important, it was a demonstration that they were the same thing” (Geertz 1980:129). This fact, however, could not prevent their conquest by the Dutch in the mid-nineteenth century when the traditional Balinese royal system collapsed (Lansing 1991:19). Ironically, the disastrous consequences of the 1970s Green Revolution (use of modern technology and fertilizers and planting crops at the same time) demonstrated the critical importance of water temples, priests, and rituals (and formerly kings) in the allocation of water to prevent the spread of disease and pests (Lansing 1991:111–126).

In sum, centralized and integrative political systems differ from one another in the way in which the distribution of resources affects how people settle and subsist, which in turn relates to political organization. Resources that are more easily accessed and where people are tied to the land facilitate the development of more centralized hierarchical political systems, whereas dispersed and diverse resources typically do not. Another crucial element is seasonal rainfall—too much or too little. All systems, however, are similar in that rulers often provide capital and sustenance (food and/or water) during times of need as well as allocate water and provide protection when necessary. Finally, political demands are superimposed on existing social and economic institutions that consequently are less affected by cyclical political histories. A greater reliance on large-scale water/agricultural systems in the face of seasonal vagaries and an illadaptive government can also be a formula for disaster.

Late Classic (ca. AD 550–850) river and nonriver major Maya centers have several factors in common with centralized and integrative polities, as I detail below.

The Maya: Regional Centers

River Centers

Regional centers, such as Palenque and Copán, are located along or near rivers with concentrated alluvium, more in line with archaic states found in temperate zones (see Figure 2.1) (e.g., Mesopotamian city-states, China, Egypt, and coastal Andean South America). The major difference between regional and other centers is that they incorporate more people and have greater power. At present I assign only two centers to this category, though others might be added in the future (e.g., possibly Yaxchilán and Piedras Negras). The elevation of Palenque and Copán is higher than that of minor and most secondary centers and similar to that of nonriver centers, from 200 to 550 m asl. Both are located on the edges of the Maya lowlands: Palenque to the northwest and Copán to the southeast. Annual rainfall is both above and below that found at nonriver centers; 130 cm at Copán and 370 cm at Palenque (see Figure 4.1). Alluvial soils surrounding Copán are concentrated within a 24 sq km area (Webster 1999). Rulers also probably monopolized trade with highland areas for jade and obsidian (e.g., Fash 1991), especially utilitarian obsidian blades (Aoyama 2001). Copán’s kings initially had the support of Tikal’s royal family to bolster their claims over others, since the founding ruler of Copán (ca. AD 426–427), K’inich Yax K’uk Mo’, may have been an “elite warrior” from Tikal (Sharer 2003).

Copán’s occupants also built large reservoirs, which may have been managed and controlled by the political elite, based on their distribution and analysis of water symbolism (Fash 2005). Additionally, while the presence of rural aguadas signifies some degree of self-reliance on the part of noncenter farmers, relatively low annual rainfall and undrinkable river water during the height of the dry season meant that local farmers relied on water management systems part of the year or even perhaps during the height of the rainy season, when heavy rains churned up sediment in the river (Davis-Salazar 2003; Fash and Davis-Salazar n.d.). As a consequence, people had fewer options and had to acquiesce to tribute demands. And since the surrounding hillsides are more difficult to plant—not to mention dealing with problems that result from heavy rainfall and erosion—farmers were more tied to the concentrated alluvium and center and hence more susceptible to political machinations. They still, however, participated in exchange with Maya in other areas independent of elite or royal supervision (e.g., Webster and Gonlin 1988). Commoners thus had some leverage, since they could either move far from the center or opt to gift their surplus to another ruler (e.g., Quiriguá).

A similar situation existed at Palenque. Palenque overlooks a fertile valley (de la Garza 1992:51–52). It sits “on a 2 × 1 sq. km plateau 100 meters above the seasonally inundated plains to the north” (Barnhart 2001:70). A sharp escarpment lies to the south, and to the east and west “the mountainside becomes more karstic and areas of habitable land appear only in isolated pockets” (p. 71). Within Palenque are over fifty streams and springs; inhabitants built aqueducts and canals to drain water away from the center—not too surprisingly, given that annual rainfall exceeds 360 cm (French 2002; French et al. n.d.). In addition, people may have constructed irrigation canals on the plains below (Barnhart 2001:101). The prevalence of water is also illustrated in the Maya name for Palenque, Lakam Ha or Big Waters (p. 100). Surrounding farmers relied on the plentiful water sources at Palenque, especially during the nonagricultural dry season.

Kings provided capital to maintain and repair water systems, especially since they were often damaged during heavy rainfall. They also handled water allocation issues or disputes. Finally, while there is little evidence for storage facilities, rulers probably supplied food from their presumed extensive fields in times of need (Lucero n.d.a).

Settlement is typically dense around centers. For example, there are 1,449 structures/km2 within Copán’s core (0.6 km2) (Rice and Culbert 1990 :Table 1.1; Webster and Freter 1990), and noticeably fewer structures in areas beyond the alluvium (e.g., 28–99 structures/km2 in rural Copán). Palenque’s site core (2.2 km2) has 643 structures/km2 (Barnhart 2001:Table 3.1).

Rulers collected tribute from densely settled farmers because of their ability to access concentrated resources, provide water and capital, sponsor integrative events, and incorporate lower-order centers and communities in the vicinity. As in secondary centers, chultuns for storage are small-scale and cluster around elite and royal residences, indicating their insignificant role in politics (Lucero n.d.a). Texts do not mention a bureaucracy or administrators, a standing army, or a formal code of laws (Fox et al. 1996). Kings, though, probably provided some degree of protection, especially to those farmers more tied to the land in the immediate vicinity; however, commoners still had the option to flee elsewhere in the face of conflict. Kings could at least protect large-scale water systems in the site core. While rulers did not have a standing army, they still could muster enough men to capture the rulers of other centers, especially secondary ones. Victory demonstrated to subjects of the vanquished rulers that it was better to support the victor. Corvée labor built large ball courts, private palaces, temples, and funerary temples. While rulers could easily access densely settled people, they still needed to integrate them, justify their rights to demand tribute, and promote solidarity in the face of political and economic inequality, which they did via public ritual events. For example, up to 3,000 observers could have watched ball games at Copán and viewed other events from the Great Plaza steps (Fash 1998). Maya farmers, however, still continued to conduct traditional rites in their homes and communities.

Kings are depicted in the iconography, as is water imagery (e.g., Fash 2005; Fash and Davis-Salazar n.d.; French 2002; French et al. n.d.; Scarborough 1998). It is interesting to note that while water lilies cannot grow in Palenque’s springs and flowing streams, their obvious ubiquity in the iconography indicates the importance of water symbolism in political ideology and rituals throughout the Maya region (see below). However, Edwin Barnhart (personal communication, 2002) suggests that some of the artificial pools could have supported water lilies. For example, he notes that an artificial pool off an aqueduct in the possible early central precinct Picota Plaza may have had water lilies, since water plants are present today, and it never dries up. Inscriptions also highlight the importance of kings and their relationship to the supernatural, watery world (Schele and Freidel 1990). Emblem glyphs of Copán and Palenque are some of the most often mentioned outside their respective centers, probably indicating their greater power compared to other center rulers (Marcus 1976).

Rulers of both river centers are some of the first kings to lose political power in the Terminal Classic. Demand for surplus production instituted by rulers may have contributed to the over-exploitation of resources. For example, Copán’s farmers started to plant on the less-productive hillsides at the end of the Late Classic due to either competition or resource degradation (Wingard 1996). Any decrease in surplus undermined the political system, whether it was caused by resource degradation, decreasing water supplies, or both. Kings had no choice but to abandon the trappings of what formerly defined Classic Maya political life—palaces, temples, inscribed sculpture, and dynastic rites. A disruption in the trade of exotics also would have lowered the prestige of rulers in the eyes of their subjects (e.g., Demarest 2004; Hosler et al. 1977). Consequently, Copán and Palenque, but not necessarily their hinterlands, were largely abandoned during the ninth century. While archaeologists do not agree on the occupation history of Terminal Classic and Early Postclassic Copán and its hinterlands (Fash et al. 2004; Webster et al. 2004), there is no doubt that its rulers disappeared forever. And because of their close ties, the decline of regional rulers also contributed to the disruption of royal power at secondary centers.

Nonriver Centers

Nonriver centers such as Tikal, Calakmul, and Caracol are similar to river centers except for several factors (see Table 2.1). They are located in upland areas with large pockets of dispersed fertile land without permanent water sources but with large artificial reservoirs located next to temples and palaces (see Figure 2.1). Centers are located at higher elevations than minor or secondary centers (over 245 m asl). The need for an adequate water supply is related to annual rainfall; it was typically less than at secondary and regional river centers (see Figure 4.1). For example, annual rainfall at secondary centers ranges from over 200 to over 280 cm; at Tikal it was just under 190 cm, at Calakmul just under 170, and at Caracol 210 (Neiman 1997:Table 15.1).

Regional rulers collected tribute in return for providing drinking water during the dry season, particularly from January through April or May, when for all intents and purposes rainfall was nonexistent and the jungle became a green desert (e.g., Folan et al. 1995; Ford 1996; Lucero 1999b; Scarborough 1991, 1993, 1996; Scarborough and Gallopin 1991). At Tikal, for example, there are at least six major reservoirs, all located in the site core next to palaces and temples (Scarborough and Gallopin 1991).

Peter Harrison (1993) correlates reservoir building with the accelerated construction of monumental architecture in Tikal’s core, especially beginning in the Early Classic. Quarrying of reservoirs provided building materials for monumental construction projects, including limestone fill, wall facing, and plaster (Scarborough 1993). At Calakmul, which is surrounded by bajos (low-lying seasonal swamps), there are extensive canal systems as well as thirteen reservoirs and aguadas (Braswell et al. 2004; Folan et al. 1995). Caracol has at least two major reservoirs next to temples and is literally surrounded by terraced hillsides for agriculture as well as water control (Chase and Chase 1996, 2001; Healy et al. 1983). Even if some bajos turn out to have been perennial wetlands or lakes (e.g., Culbert 1997; Dunning et al. 1998, n.d.; Hansen et al. 2002), their location at or near major centers would have provided rulers with even more water and agricultural surplus at their disposal. This may have been more noticeable in higher elevations; Pope and Dahlin (1989) note that perennial wetlands are more common in areas below 80 m asl. Until we have better information about bajos, however, I take a conservative approach and treat them all the same at present (i.e., as seasonal swamps).

A challenge the Maya did face, however, was keeping standing water clean during the dry season. Standing water quickly becomes stagnant and provides prime conditions for insects and parasites to proliferate and, more significantly, can result in the build-up of noxious chemicals (e.g., nitrogen) (Burton et al. 1979; e.g., Hansen et al. 2002). The natural wetland biosphere acts to sustain clean water if a balance of hydrophytic and aquatic plants is maintained (Hammer and Kadlec 1980; Nelson et al. 1980). Maya kings organized the maintenance of reservoirs during the dry season (Ford 1996) and performed important rites to keep water clean (Fash 2005; Lucero 1999b; Scarborough 1998). In fact, Maya rulers appropriated traditional water rites and conducted them in grand settings to demonstrate their success in propitiating the gods (Scarborough 1998). Rulers conducted water rites at the sources themselves—reservoirs next to temples.

Settlement is dense around centers (e.g., 235–557 structures/km2; Culbert et al. 1990) and in hinterland areas (e.g., up to 313 structures/km2; Folan et al. 1995). People lived in farmsteads scattered throughout the landscape, mirroring the distribution of good land, which made it challenging for rulers to bring people together to organize work parties, feasts, and ceremonies, not to mention to extract surplus. This fact did not prevent commoners from exchanging goods with one another outside of elite or royal interference (e.g., Ford 1986). Similar to the situation at secondary centers, corvée labor probably only worked the royal plots of land in the immediate vicinity of centers. Beyond this, kings had to compensate laborers with exotics and a portion of the crop. Rulers, however, funded large-scale public rituals in plazas at the foot of temples to attract and integrate farmers, especially during annual drought when water shortages would have been a problem. In exchange, rulers received tribute in the form of surplus labor, goods, and food from farmers and people from lower-order centers and communities in the vicinity (Lucero 1999b). Despite participating in royal rites, Maya commoners conducted similar rites in the home on a much smaller and private scale. Again, small-scale storage facilities precluded their role in political life (Lucero n.d.a).

Rulers interacted on an equal footing with other primary rulers through alliances, marriages, and warfare and incorporated nearby secondary and minor centers. Warfare was conducted to capture fellow royals, increase their prestige in the eyes of contributors, and attract more members into their political fold. For example, after kings from Caracol defeated those of Tikal twice in the latter half of the sixth century (AD 556 and 562), possibly with a little help from their allies at Calakmul (Braswell et al. 2004; Chase and Chase 1989), many farmers appeared to have left the losing polity to join the successful one. Because of their victory, Caracol’s kings were able to attract or persuade many of the Tikal’s former supporters to nucleate around Caracol (and perhaps Calakmul; Marcus 2003) instead of Tikal. As a result of this population shift Caracol’s kings had access to a dramatically larger labor pool, since it was obvious that Caracol’s rulers had better supernatural connections than those at Tikal. Evidence for migration to Caracol includes a noticeable increase in settlement density in and near Caracol (Chase and Chase 1996), the large number of terraces that appeared relatively quickly, and an increase in inscriptions and monumental building in the site core (Chase and Chase 1989). Arlen Chase and Diane Chase (1996) estimate that population increased 325 percent over the next 130 years. Further, there are the indications that population growth slowed at Tikal (27.5% for central Tikal and 15% for its hinterlands) (Haviland 1970). Commoners moved to Caracol’s realm to access the victor’s better supernatural connections.

Thus, during the Classic period, “hiatus” (AD 534–593 and as late as 692 at Tikal)—defined as a lessening or a cessation of stela erection and monumental construction—probably represented labor and power shifts (e.g., Fry 1990). In other words, kings who did not have the means to attract the necessary labor could not afford to build monumental structures. Caracol’s rulers, however, were not the only ones competing for labor, as recorded in the inscriptions at Late Classic centers with the increasing mention of battles, intercenter ball games, and the sacrifice of captives.

Kings distributed exotics to lower-level elites and some commoners. They also organized the construction of public works, ball courts, large administrative and private palaces, and funerary temples as well as utilized carved texts and emblem glyphs. Other than Caracol, nonriver center emblem glyphs are the most frequently mentioned at other centers (Marcus 1976; Martin 2001). In addition, E-Group and Twin-Pyramid complexes are typically found only at nonriver centers (Arie 2001:49).

Kings and water imagery were prevalent in the iconography and are visible indicators of the relationship between water and political power, especially their performance of water rituals and providing clean water (Lucero 1999b). A visible sign of clean water is water lilies. Water lilies (Nymphaea ampla) are sensitive hydrophytic plants that can only grow in shallow (1–3 meter), clean, still water that is not too acidic and does not have too many algae or too much calcium (Conrad 1905:116; Lundell 1937:18, 26). Thus, the presence of water lilies on the surface of aguadas and reservoirs is a visible indicator of clean water. A major symbol of royalty in Classic Maya society is the water lily and associated elements (e.g., water lily pads, the water lily monster, etc.), which are found depicted on stelae, monumental architecture, murals, and mobile wealth goods such as polychrome ceramic vessels (e.g., Fash 2005; Fash and Davis-Salazar n.d.; Hellmuth 1987; Puleston 1977; Rands 1953; Scarborough 1998). Ford (1996 : 303) notes that Nab Winik Makna (Water Lily Lords) refers to Classic Maya kings. Water lilies often make up part of royal headdresses as well (Fash and Davis-Salazar n.d.). Often rulers have names that include “water” (e.g., Water Lily Lord of Tikal and Lord Water of Caracol). Further, kings impersonated sun, maize, and other gods through the wearing of masks and costumes; “Another deity impersonated by Maya lords … seems to be aquatic represented as a serpent with a water-lily bound to its head” (“water serpent”; Houston and Stuart 1996:299).

The continued supply of clean water meant that rulers were successful in supplicating gods and ancestors and that rulers had special ties to the supernatural world that benefited everyone—for a price, of course. Inscriptions and iconography amply illustrate that Classic Maya rulers had closer ties to important Maya deities, ancestors, and the supernatural world than the rest of Maya society (e.g., Houston and Stuart 1996; Marcus 1978; McAnany 1995; Schele and Freidel 1990; Schele and Miller 1986).

Farmers in hinterland areas without permanent water sources could not amass enough labor to build their own water catchment systems, since they lived dispersed throughout the hinterlands (e.g., Scarborough 2003:93). During the rainy season, it would have been easy to store water in jars or other containers, since supplies were replenished daily. They also relied on aguadas, but their small size would not have supported large numbers of people throughout the year. In addition, during the dry season water eventually evaporated in smaller aguadas (Scarborough 1996). Estella Weiss-Krejci and Thomas Sabbas (2002), however, suggest that archaeologists need to take into account small (7–722 m2, 0.4–1.0 m deep) natural and artificial depressions as possible year-round household water storage systems based on their work in northwestern Belize. But only four (25%) of the sixteen depressions they excavated were “good” candidates for water storage. They suggest that the Maya may have relied on the water stored in these depressions throughout the year and perhaps prevented evaporation by using covers, for example. Weiss-Krejci and Sabbas also note that in times of particularly bad dry spells that stored water would not have lasted the entire dry season. Taken together, these factors suggest that at least during the dry season many farmers had little choice but to rely on royal reservoirs, though perhaps a few family members stayed behind. Farmers did have options as to which royal reservoir people paid to quench their thirst (e.g., the Tikal/Caracol labor shifts discussed above).

The Terminal Classic period (ca. AD 850–950) witnessed the loss of political power. As long as the water supply was adequate, rulership lasted. For example, Tikal has one of the longest political histories in the entire southern Maya lowlands (inscriptions date from AD 292 to 869). Clearly rulers were successful in expanding and maintaining their political base through providing water and sponsoring integrative events. Their source of power, however, was susceptible to fluctuations, especially in the water supply. This accounts for the abandonment of Maya royal centers by the ninth or tenth century (e.g., Braswell et al. 2004; Valdés and Fahsen 2004). For example, Arlen Chase and Diane Chase (2004) demonstrate that the Maya at Caracol continued to build monumental architecture until after ca. AD 800 and that nonroyal elites continued to live in the epicenter until ca. AD 895. They also note that when people did abandon Caracol, by ca. AD 900, they did it relatively rapidly. As long as subsistence resources were available, however, farmers did not necessarily abandon hinterland areas, since political events taking place at royal centers did not always affect them. They continued to farm in small communities, participate in local and household ceremonies, and maintain small-scale water systems (e.g., aguadas).

In sum, we can better understand how the Maya lived at regional centers through what we know about centralized and integrative polities. The major difference between centralized polities/river centers and integrative polities/nonriver centers is that in the former case most of the agricultural land is concentrated along rivers rather than being dispersed in areas without surface water. As a consequence, there were different settlement patterns; farmers lived near where the land is fertile. Where farmers are more dispersed, rulers continually had to maintain their ties with subjects through frequent feasts, ceremonies, and games. The nature of Maya warfare was different as well and related more to status rivalry (Webster 1998) rather than conquest for labor per se. I am sure, however, that victorious kings benefited from access to greater labor pools—not by forcibly incorporating people but by attracting them due to their success as warriors and as intermediaries with gods and ancestors. Another distinctive aspect of the Maya is the apparent lack of large-scale storage facilities. Combined factors of humidity, heat, and farming practices did not make the construction of large-scale storage facilities practical or feasible. A final difference from most other ancient societies is the lack of clear evidence for markets, though some Mayanists suggest plazas could have served as markets (e.g., Jones 1991; Scarborough et al. 2003). The nature of subsistence practices—relatively self-sufficient—and the archeological record indicate a royal and elite concern with the long-distance exchange of prestige goods rather than utilitarian ones.

Since there are many similarities between river and nonriver regional centers, especially the degree of political power that rulers had, I only detail the ritual history at one such center, Tikal.

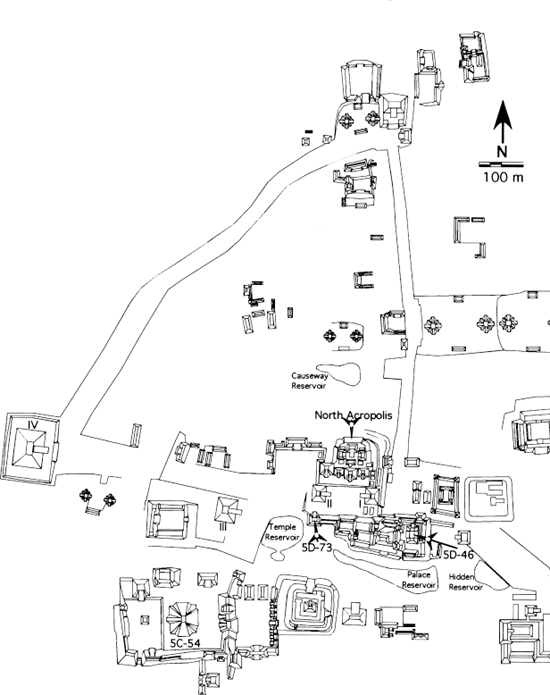

Ritual History of Tikal

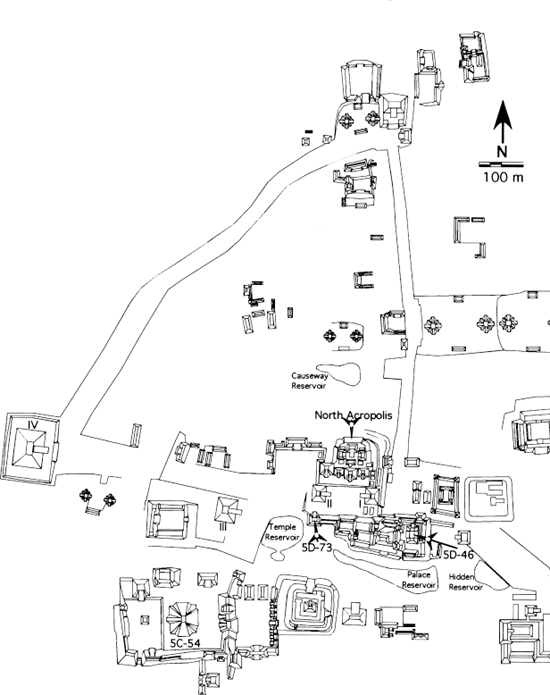

Tikal is located in the Petén district, Guatemala, on top of an escarpment (250 m asl) surrounded by swampy areas to the west and east, earthworks to the north and south (Jones et al. 1981), and large tracts of fertile land (Fedick and Ford 1990).1 It is one of the best-known and largest Maya centers (Figure 6.1). Since it is not near lakes or rivers, its inhabitants relied on several complex reservoir systems to offset seasonal water shortages (Scarborough and Gallopin 1991), which are found next to temples and royal palaces. The central core (9 km2) consists of a densely built landscape of public and private monumental and nonmonumental architecture (ca. 235 structures/km2) (Culbert and Rice 1990:Table 1). Annual rainfall is less than at secondary centers and Palenque, but more than at Copán (ca. 190 cm) (see Figure 4.1).

Commoners were densely settled immediately around Tikal—for example, 181 to 307 structures/km2 in the 7 km2 area immediately surrounding the core and 112 to 198 structures/km2 beyond that (Culbert and Rice 1990:Table 1). They acquired goods through exchange with other commoners elsewhere, especially for utilitarian goods, as well as prestige items (e.g., Haviland 1985). The nearest known obvious agricultural systems (terraces) are ca. 28 km away (Harrison 1993), though some of the bajos might have supported two or three crops per year (Scarborough 1993; e.g., Hansen et al. 2002). Chultuns, as is the case at other Maya centers, cluster at elite residences (see Puleston 1983 survey maps).

Tikal was ruled by a “holy” or “divine” king (k’ul ahaw), who implemented tribute demands. Tikal has inscriptions, its own emblem glyph, water symbolism, palaces, royal funerary temples, large ball courts, and tall temples facing large and open plazas (e.g., Temple IV is 65 m tall). Its monumental complexes are connected via sacbeob (causeways). The earliest inscribed stela in the southern Maya lowlands (Stela 29, AD 292) is found at Tikal, and it has one of the longest dynastic histories in the Maya area (last known inscribed date: AD 869). Rulers early on absorbed surrounding centers (e.g., Uaxactún). The earliest recorded inauguration was in AD 320 and the last in AD 768, though a founding ruler is mentioned much earlier, between AD 219 and 238 (Sharer 1994:178), and kings are mentioned up to AD 869 (Martin 2003). Even if outsiders from Teotihuacan replaced or intermarried with Tikal’s royal line in AD 378 (Martin 2003), they clearly adopted the use of traditional Maya rites in addition to foreign and new ones; there is no break in the ritual histories of structures. Tikal was largely abandoned in the AD 900s, as were most major centers in the southern Maya lowlands.

Figure 6.1. Tikal. Adapted from Martin and Grube (2000:24).

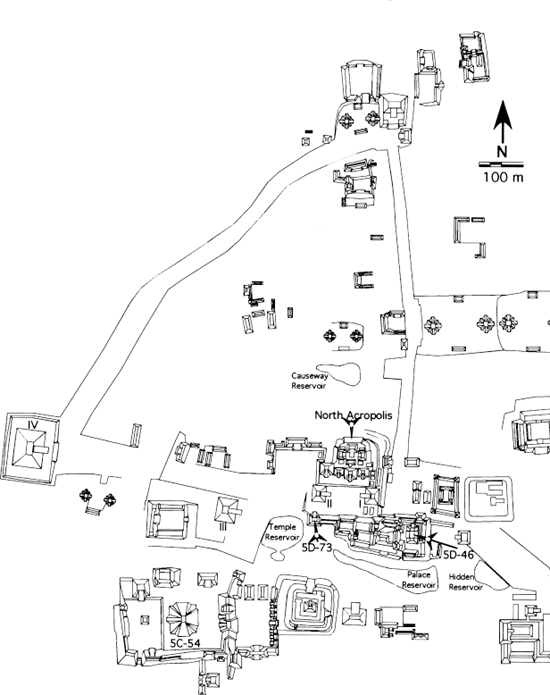

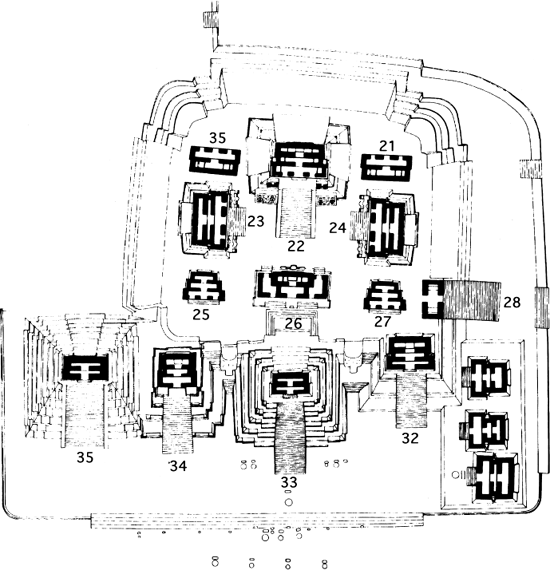

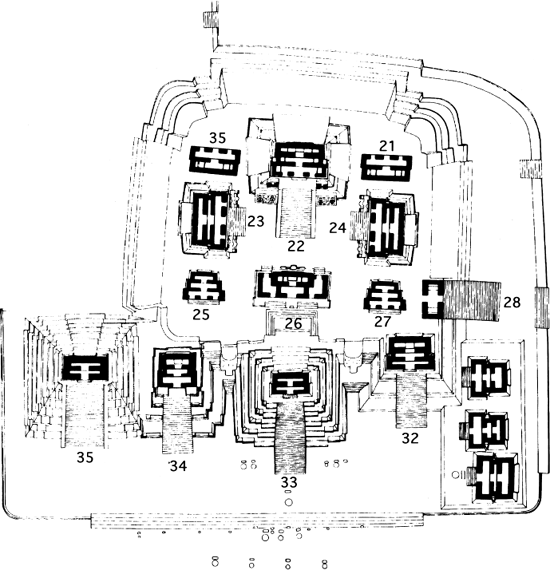

Tikal also has one of the longest sequences of monumental architecture in the Maya lowlands. For example, more than a thousand years of temple construction (e.g., twenty plaster floors), destruction (e.g., smashed objects and defaced monuments), and rebuilding occurred in the site’s North Acropolis (Figure 6.2) (Sharer 1994:154–159). At the time of abandonment, this necropolis was approximately 100 × 80 m, with structures totaling 40 m high, though it began as a 6 × 6 m structure (Coe 1965b, 1965c, 1990) (Figure 6.3), similar in size to commoner residences at Saturday Creek. It supports at least eight funerary temples, most from the Early Classic period. On the south it faces the Great Plaza (125 × 100 m), where an audience probably would have watched and participated in royal ritual performances at least until the last few centuries of occupation at Tikal, when structures were built that restricted access.

Figure 6.2. North Acropolis, Tikal. After W.R. Coe, University of Pennsylvania Museum Tikal Project, Neg. #98-5-2.

Figure 6.3. North Acropolis profile. After W.R. Coe, University of Pennsylvania Museum Tikal Project, Neg. #67-5-113.

In the following section I highlight the history of royal ritual events, because they differ noticeably from Saturday Creek and Altar de Sacrificios rites and because elite and commoner ritual deposits are more similar to those at the smaller centers.

The Preclassic (800 BC–AD 250)

While ritual evidence from commoner contexts in Tikal’s outskirts does not seem apparent as it does in later periods, the earliest houses and small temples actually are buried underneath later and increasingly monumental buildings. I largely focus on the ritual history of the North Acropolis because of the extensive excavations conducted there by the University of Pennsylvania team and later by Guatemalan archaeologists.

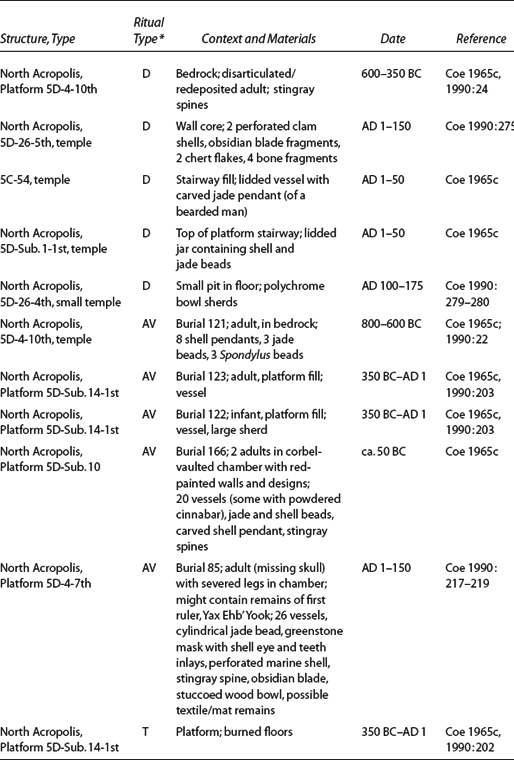

The Maya began to build the North Acropolis sometime after 600 BC by digging several pits, within which they placed a human skull and Preclassic ceramics. The earliest substantial architecture (300–200 BC) includes three successive platforms (5D-Sub.14-3rd, -2nd, -1st), each comparable in size to a large thatched house on a platform, approximately 6 × 6 m, similar in size to SC-18 and SC-85 at Saturday Creek. William Coe (1965c:12–13) describes the last of these three temples (5D-Sub.14-1st) as follows:

The roof was probably of thatch with poles at the corners…. This building burned, then was refloored, then charred again…. Beneath its floors were three burials, an infant and two adults who were partially protected by … large inverted Chuen [350 BC–AD 1] plates. Pits in bedrock in front of these platforms yielded other insights. One contained a young adult … with a necklace of shell pendants and imported jade and shell beads…. The other pit contained the incomplete disarticulated remains of an adult accompanied by fragments of one or more stingray spines [used for ceremonial bloodletting].

This pattern of burning and destroying—terminating—earlier architectural features continues throughout the building of the North Acropolis (Coe 1990:506).

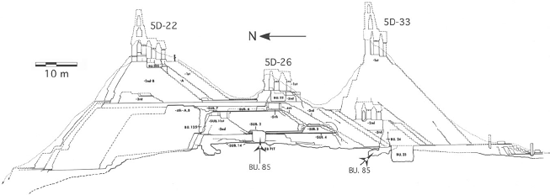

The Maya also dedicated each construction event. As early as ca. AD 1–50, a lidded jar with shell and jade beads was found on top of one of the platform stairways associated with Str. 5D-Sub.1-1st (Table 6.1). At a contemporary temple with four stairways (Str. 5C-54) beneath the base of the east stairway the Maya had placed a large lidded red vessel containing a carved jade pendant depicting a bearded man (Coe 1965c). In the wall core of an early temple dating to AD 1–150, Str. 5D-26-5th, the Maya deposited two perforated clam shells, two obsidian blade fragments, two chert flakes, and four bone fragments (Coe 1990:275). In the next phase (5D-26-4th), dating to AD 100–175, the Maya dug a small pit in which they placed the sherds of a large polychrome bowl (pp. 279–280).

The earliest clearly elite or royal burial at the North Acropolis is associated with Platform 5D-Sub-10 (Burial 166), dating to ca. 50 BC. The Maya entombed two females in a corbel-vaulted chamber with painted designs on redplastered walls along with twenty vessels, some with powdered cinnabar, jade and shell beads, stingray spines, and a carved shell pendant (Coe 1965c). Another elite burial located within Platform 5D-4-7th (No. 85, dating to AD 1–150) consisted of a simple chamber with small slabs as a roof, within which a bundled male was buried with his legs severed and without a skull. Twenty-six vessels were also interred, as well as a cylindrical jade bead, a greenstone mask with shell eye and dental inlays, a perforated marine shell, a stingray spine, an obsidian blade, a stuccoed wood bowl, possible cinnabar dust (perhaps all that remains of a red-painted textile or mat), and other objects (Coe 1990:217–219). Burial 85 actually might contain the remains of the first acknowledged ruler of Tikal, Yax Ehb’ Yook (?) (Martin 2003). Whether burials were public or private events, the fact that these burials were found in monumental buildings distinguishes them from residential burials.

Commoner Maya practiced similar, though simpler, rites, as did their peers at Saturday Creek, Altar de Sacrificios, and other Maya centers.

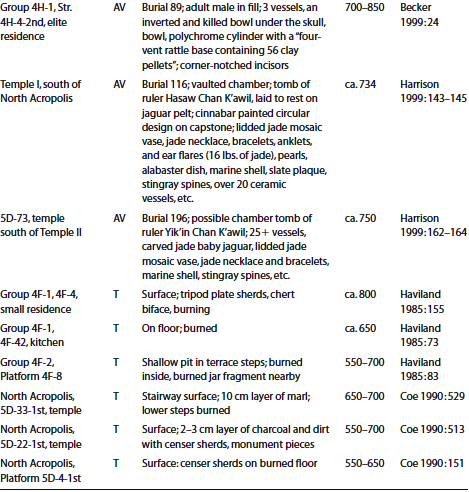

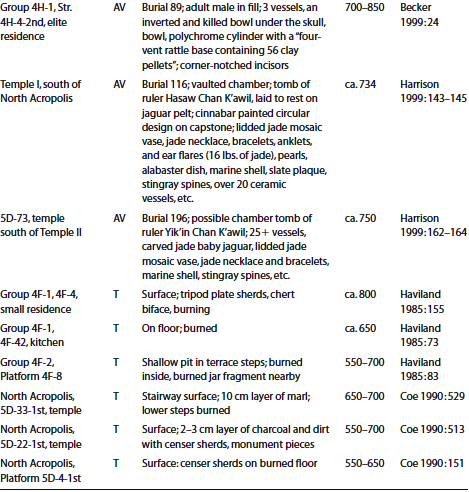

Table 6.1. Tikal Preclassic ritual deposits

*D = Dedication; AV = Ancestor Veneration;T = Termination.

The Early Classic (ca. AD 250–550)

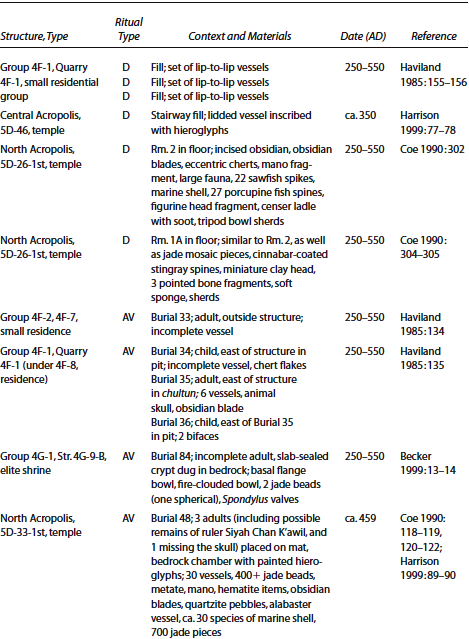

At the North Acropolis of Tikal during the Early Classic, Coe (1965c:31) notes a “plethora” of ritual deposits under floors, on the surface of floors, and in the fill, consisting of thousands of obsidian pieces, eccentric cherts, and marine objects (shell, especially carved Spondylus, sea-worms, stingray spines) (Table 6.2).

Lip-to-lip ceramic vessels with offerings were replaced by fancier lidded vases and other vessels, some of which are incised or painted with hieroglyphs stating who lived in the structure (e.g., stairway dedication cache, Str. 5D-46) (Harrison 1999:77–78). Within Str. 5D-26-1st, in the floor of one of the two rooms (Room 2), archaeologists found incised obsidian, obsidian blades, chert eccentrics, a mano fragment, large faunal remains, twenty-two sawfish spikes, marine shell, twenty-seven porcupine fish dermal spines, part of a tripod bowl, a censer ladle encrusted with soot, and a figurine head fragment (Coe 1990: 302). They recovered similar items in the floor of Room 1A, as well as jade mosaic pieces, a miniature clay head, three sharpened bone fragments, soft sponge, and cinnabar-coated stingray spines (Coe 1990:304–305). These caches contrast with those found in residences about 1 km to the northeast, which consist of single sets of lip-to-lip vessels (Haviland 1985:155–156).

Elite Maya distinguished their ancestors from common ones by burying their dead in eastern shrines, which first appear in the Early Classic (Becker 1999:144). For example, Burial 84 in Str. 4G-9-B, dating to ca. AD 250–550, consists of a crypt dug into bedrock sealed with stone slabs (p. 13). An adult was interred with a basal flange bowl, a fire-clouded bowl, jade beads (including a spherical one), and Spondylus valves (pp. 13–14). Commoner residential burials at Tikal are similar to those at Saturday Creek and Altar de Sacrificios. For example, Burial 33, just south of Str. 4F-7, includes an adult male with an incomplete vessel (Haviland 1985:134). In contrast, Burial 48, associated with temple 5D-33-1st of the North Acropolis, consisted of a chamber with a domed ceiling and walls painted with hieroglyphs (Coe 1990:118–119; Harrison 1999: 89–90) that contained three individuals (possibly including the ruler Siyah Chan K’awil and sacrificial victims), one with a severed head, placed on mats or skins, along with 30 vessels, over 400 jade beads, a metate and mano, hematite items, obsidian blades, quartzite pebbles, an alabaster vessel, about 30 different species of marine shell, and nearly 700 jade pieces (perhaps part of a mosaic) (Coe 1990:120–122). Its location at the foot of an imposing temple facing a plaza may indicate a public ceremony venerating a royal ancestor.

Termination rituals are indicated by burned floors at every residence (Haviland 1985) as well as burned and smashed items such as ceramics. Burning also occurred throughout Early Classic building events at the North Acropolis (Coe 1990). The Maya incorporated into the fill of new monumental structures the destroyed remains of earlier carved building fragments (e.g., Str. 5D-26-1st) (p. 314).

Table 6.2. Tikal Early Classic ritual deposits

The Late Classic (ca. AD 550–850)

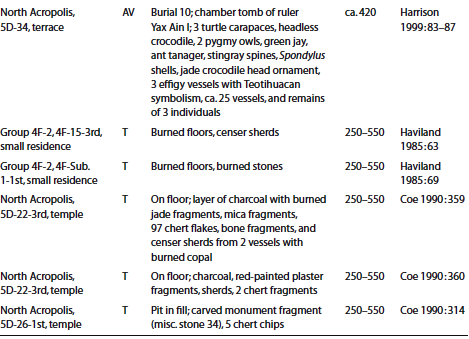

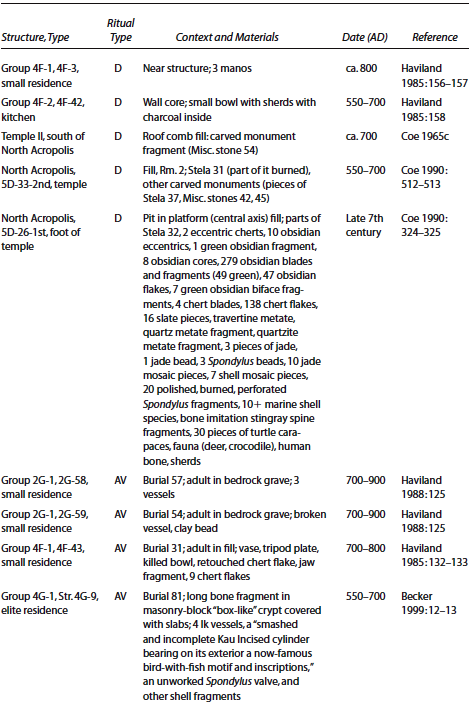

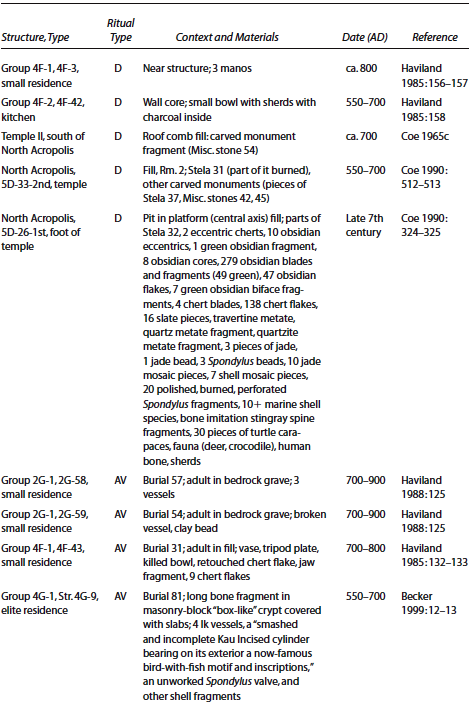

Caching behavior somewhat similar to that seen at Saturday Creek and Altar de Sacrificios is evident among smaller residences at Tikal, contrasting dramatically with what has been revealed in monumental architecture (Table 6.3). At the small residence Str. 4F-3 of Group 4F-1, three manos were placed near the house, in what Haviland (1985:156–157) calls a “votive” deposit. In a gap in a wall of Str. 4F-42, another small residence, the Maya placed a small bowl containing sherds and charcoal (p. 158). These caches noticeably differ from royal ones.

At Temple II, Miscellaneous Stone 54, originally a Preclassic sculptural decoration, was refit with another façade fragment from Late Classic temple fill 800 years later (Coe 1965c). In another example of the caching of older monumental pieces, the Early Classic Stela 31 was cached under the floor of Str. 5D-33-2nd prior to the Late Classic construction of Temple 5D-33-1st (Coe 1990:512–513). Other offerings included large chert eccentrics, incised obsidian, stingray spines, jade items of all shapes and sizes, hematite objects, coral, various species of marine shell, and stuccoed objects (e.g., Temple 5D-26-1st).

Table 6.3. Tikal Late Classic ritual deposits

Late Classic royal burials are quite spectacular. One of the most imposing temples at Tikal, Temple I, served as the funerary temple of Tikal’s most powerful ruler, Hasaw Chan K’awil (Heavenly Standard Bearer), who ruled from AD 682 until about AD 734 (Burial 116) (Harrison 1999:143–145). It overlooks a large plaza where subjects likely witnessed the interment of their deceased king. With him were entombed over twenty vessels, slate plaques, alabaster dishes, carved and incised bone, and more than sixteen pounds of jade items, including a mosaic-lidded vase. His family members and priests laid him to rest on a jaguar pelt, the major symbol of Maya kingship. In contrast, Late Classic burials found beneath the floors of one of the five structures of Group 2G-1, a nonroyal Tikal residence less than 2 km northeast of the North Acropolis, were quite simple and involved family members only. Burial 57 consisted of a male placed in a “bedrock grave containing three vessels”; another male (Burial 54) was buried with only “a single broken vessel and a clay bead” (Haviland 1988 : 125). A similar pattern is found at residences located less than 1 km northeast of the North Acropolis. For example, Groups 4F-1 and 4F-2 burials yielded polychrome bowls and some small jade pieces (Haviland 1985).

Commoner and elite burials are similar to those described for Saturday Creek and Altar de Sacrificios. In the summit of Str. 4G-9 of Group 4G-1, the eastern structure (shrine) of an elite residence, archaeologists came upon a masonry-block “box-like” crypt sealed with slabs (Burial 81) (Becker 1999:12). It consists of a long bone fragment, four Ik vessels, a “smashed and incomplete Kau Incised cylinder bearing on its exterior a now-famous bird-with-fish motif and inscriptions” (p. 12), an unworked Spondylus valve, and other shell fragments. At another elite burial (Burial 89), dating to ca. AD 700–850 in the fill of Str. 4H-4-2nd of Group 4H-1, the Maya interred an adult male who had corner-notched incisors, with three vessels, an inverted and killed bowl underneath the skull, a bowl, and a polychrome cylinder with a “four-vent rattle base containing 56 clay pellets” (Becker 1999:24).

Termination rites at Tikal, especially indicated by burned plaster floors and broken items, are evidenced throughout small houses and monumental buildings. For example, tripod sherds and a chert biface were found on a burned floor of Str. 4F-4, a commoner residence (Haviland 1985:155). A residential platform (4F-8) contained a pit with burning on the inside and half a burned jar (p. 83). At the North Acropolis, Coe (1990:525) writes, “Fire and presumably incense appear to have been a functional constant.” The Maya burned copal in censers and then broke them (e.g., Temple 5D-22-1st, Platform 5D-4-1st).

Site formation processes similar to those at Saturday Creek and Altar de Sacrificios shaped small and monumental structures at Tikal. In “almost constant renovation, razing, and renewed construction” (Coe 1965c:13), ever-larger temple complexes grew over these early deposits. This process clearly resembles household rituals, albeit on an increasingly grand and public scale. Caches, burials, burned deposits, and destroyed objects are found throughout the depositional history of the North Acropolis and other monumental architecture. Through time in elite and later royal contexts, ritual activities became more labor intensive, exotic, political, and public but materially remained tied to traditions, including those supplicating gods and ancestors for water and other critical elements in life.

Rulers of Tikal conducted the same rituals as elsewhere but on a much larger and public scale. The life histories of monumental public buildings demonstrate ritual replication and expansion of dedication, ancestor veneration, and termination rites. These buildings face large plazas in which hundreds, if not thousands, of people witnessed and participated in ritual events. Further, because of their location these public arenas function as acoustic marvels. One can stand on top of Temple II, for example, speak, and be heard by all below. Aptly, the title ahaw can be translated as “he who shouts” (Houston and Stuart 2001), which would go well with the idea of the king performing, communicating important information, and conducting rites for the people below. Elite and commoner residences show the same depositional histories but on a smaller scale, more in line with those seen at Saturday Creek, Barton Ramie, Altar de Sacrificios, and Cuello. The goods that elites and commoners interred or destroyed as offerings, however, were not as ornate as the items found in royal contexts.

Kings at Tikal and comparable nonriver and river centers were vulnerable to changing material conditions because of seasonal water fluctuations and reliance on large-scale water/agricultural systems. Ritual can only go so far in bringing people into the political system. Kings need to feed and entertain farmers as well as provide water during seasonal drought and/or capital to repair water/agricultural systems damaged by heavy rains. When they could no longer do so, they lost their major means of extracting food and services from subjects. People voted with their feet and withdrew their support of Classic Maya kings. A few hardy souls reoccupied royal homes (“squatters”) or remained in hinterland areas; they all continued to conduct traditional rites, at least through ca. AD 1000 (e.g., at Temples I, II, and III and other buildings) (Valdés and Fahsen 2004).