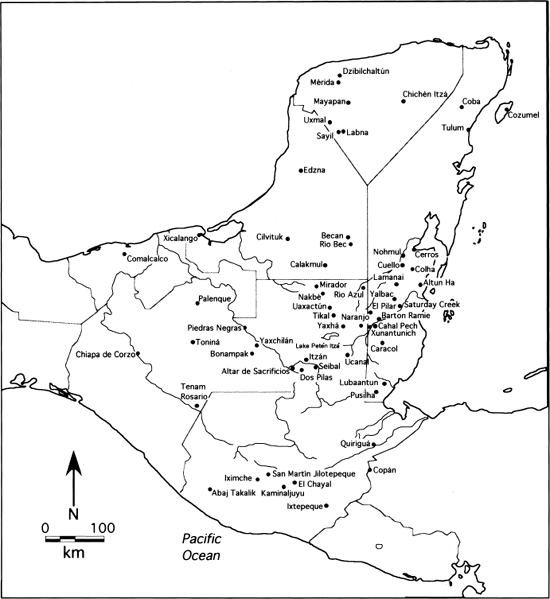

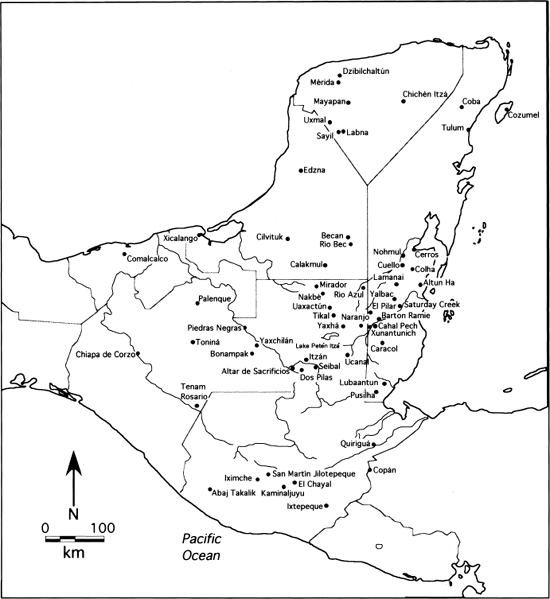

No one questions the existence of powerful Classic Maya rulers in the southern Maya lowlands of present-day Central America (northeastern Chiapas, eastern Tabasco, southern Campeche and Yucatán of Mexico, north and central Guatemala, Belize, and western Honduras) (Figure 2.1). To appreciate their accomplishments, we need to understand the variety of political systems as well as the people who supported rulership via surplus goods and labor—commoners. Farmers provided rulers’ foods, goods, and the labor to work in their fields and to build their palaces, temples, and ball courts. Evidence for surplus above and beyond household and community needs is quite apparent in the archaeological record—monumental buildings (temples, palaces, and ball courts), large-scale water systems (e.g., reservoirs), skillfully manufactured and labor-intensive wealth objects and inscribed and carved monuments, and the presence of nonsubsistence producers (e.g., artisans and rulers and their families, retinues, and underlings). Maya kings could not have funded these activities without the support (surplus) of many others. While it is not possible at present to determine exactly how surplus was organized (equal compensation, corvée labor, or combinations of both), there can be little doubt that surplus labor was available and that kings were able to access it.

How did Maya rulers acquire surplus from others? What say did commoner farmers have? These questions are crucial in view of how the Maya lived on a day-to-day basis and what this meant for rulers who wanted, and needed, to interact and communicate with farmers to be able to appropriate surplus labor and goods. They also relate to how powerful Maya rulers became. Simply put, the most complex and powerful polities emerged in areas with the most noticeable seasonal rainfall concerns—not enough or too much—and large amounts of fertile land. Before focusing on the varied Late Classic Maya political systems and histories at minor, secondary, and regional centers in Chapters 4, 5, and 6, I briefly describe Maya subsistence and settlement, a history of Maya rulership, and characteristics that distinguish different centers.

Figure 2.1. The Maya area

Ancient Maya Living

Among the ancient Maya, as in other agricultural societies, the distribution of resources and people across the landscape affected the ability of rulers to interact with and integrate people and expand the political economy. Farmers used varied agricultural techniques to grow maize, beans, and squash, including house gardens, short-fallow infields, and long-fallow outfields, or combinations thereof (Flannery 1982; Harrison and Turner 1978; Killion 1990). Maya agriculture was rainfall-dependent, and farmers used various water or agricultural systems including aguadas, artificial reservoirs, raised fields, dams, canals, and terraces (Dunning et al. 1997). The majority of farmers lived in farmsteads (one to five structures facing an open area or patio) dispersed throughout the hinterland, as well as near or in centers, mirroring scattered pockets of fertile land (Dunning et al. 1998; Fedick and Ford 1990; Ford 1986; Rice 1993; Sanders 1977). Many farmers also seasonably inhabited field houses away from their homes (e.g., Lucero 2001:35–38; Webster et al. 1992). In addition, farmers searched for new land in the face of population growth and competition over land (Ford 1991a; Tourtellot 1993). Finally, it appears that scattered hinterland settlements were largely economically self-sufficient (Lucero 2001). Something then had to bring farmers and other subsistence producers to centers and get them to pay taxes, so to speak. It was not stored food, since centralized or large-scale storage facilities are unknown in the southern Maya lowlands (Lucero n.d.a). The average farmer probably did what the Lacandon of highland Chiapas do at present; farmers collect corn every few days from their fields as needed (McGee 1990:36). They turn the ears of corn downward to prevent damage from rain and pests (e.g., birds).

Maya political agents were faced with integrating a dispersed, relatively self-sufficient populace, and one that may have been somewhat seasonally mobile. Traditionally, Maya move their families around for several reasons. For example, during the agricultural season in San José, Lake Petén Itzá, Guatemala, many farmers live in their field houses away from their village homes; the size and distance of milpa fields determine whether they stay just during the week (49%, n = 39) or move their entire families to the field for the duration of the growing season (11%, n = 9) (Reina 1967). This strategy is often necessary due to the demands of agriculture; for example, in the Lake Petén Itzá area, fields are first cleared (cutting can be easier during the rainy season when vegetation is green; Faust 1998:153) and then burned at the end of the dry season. The Maya plant seeds at the beginning of the rainy season, after which the most intensive labor is required for daily maintenance (e.g., weeding) when crops are growing (Reina 1967; see also Atran 1993).

Ruben Reina (1967) also notes that farmers abandon field houses every three to four years when crop productivity decreases in search of more fertile land. Betty Faust (1998:56–57) describes a similar pattern for the Maya in Pich, in the southeastern Yucatán; each family group has rights to two or three rancherías (field houses). Each field is planted for about two years and left fallow for fifteen to twenty years. Consequently, each household could conceivably build at least three field houses, if not more, during the course of a generation. Faust (1998:82) also found that people migrated in search of water:

…oral histories collected from 1985–1992 indicate that normal yearly fluctuations just result in temporary migration to relatives in neighboring villages that have more reliable wells…. These same oral histories refer to processes of village fission, where groups of young people leave to look for existing ponds (which possibly were abandoned reservoirs of former occupied settlements) near good soil, where they can begin new hamlets.

Seasonal and residential mobility occurred during the Colonial period too (e.g., Farriss 1984:199–223; Graham 1994:325; Tozzer 1941:90). Social and political factors also can result in migration; for example, migration was an effective strategy to escape Spanish demands in colonial Mexico (Fox and Cook 1996). The point of this brief presentation of historic and ethnographic cases of seasonal and residential mobility is to highlight the fact that these processes also likely took place in the more distant past—especially to meet dry-season water needs. Thus, even if the majority of prehispanic Maya farmers were involved in intensive agricultural and permanently settled in hinterland areas, the need for water may have drawn them into centers.

Nearly everything in Maya life was rainfall-dependent (e.g., Scarborough 2003). The annual dry season, up to six months long, had to be a concern, especially in areas without surface water. While the dry season was an agricultural down-time for the most part (usually January through May or June), people still required water for daily drinking needs, not to mention for cooking maize and other food preparation, making plaster and ceramics, bathing, and other activities. When the southern Maya lowlands became a green desert each year, water was vital and became a key factor in the emergence of political power in many, if not most, areas (Lucero 1999b). People relied on artificial reservoirs (e.g., Ford 1996). For example, Vernon Scarborough (2003:51; Scarborough and Gallopin 1991) shows that the water catchment system at Tikal could collect more than 900,000 m3 of water (based on 150 cm of annual rainfall). The central precinct reservoirs (six) alone could hold from 100,000 to 250,000 m3 of water. Using the estimate suggested by Patricia McAnany (1990) that each person needs 4.8 liters of water daily (which includes water for drinking, washing, making ceramics, cooking, and other daily requirements), we can estimate how many people Tikal’s reservoirs potentially serviced. There are several estimates for Tikal’s population, including the periphery; William Haviland (2003) suggests about 45,000 people, while T. Patrick Culbert et al. (1990) suggest up to 62,000. Given that 1 m3 is equal to 1,000 liters, 45,000 to 62,000 people would require, for a period of six months, from 38,880,000 to 53,568,000 liters or 38,880 to 53,568 m3 of water. These figures do not take into account other types of reservoirs at Tikal (residential and bajo-margin reservoirs andaguadas) (Scarborough and Gallopin 1991) or other types of activities that require water (e.g., agricultural activities and building projects). However, this brief exercise does illustrate the potential number of people who could have used royal reservoirs at Tikal (and other centers).

Hinterland farmers may have had another option than relying on royal reservoirs: spring wells. Kevin Johnston (2004b) suggests that some Maya in the Petén dug wells at fault springs, which he found to be the case at Itzán (which is less than a kilometer from Laguna Itzán), Uaxactún, and Quiriguá. None of these sites, however, are regional centers. Adequate dry-season water supplies meant that rulers did not have the means to acquire much power. And in contrast to parts of the northern lowlands, the water table is too low to access water via wells in the southern Maya lowlands (McAnany 1990), except in a few instances (e.g., Quiriguá) (Ashmore 1984).

The wet season also brought its own suite of problems, especially flooding and hurricanes. While the prehispanic Maya did not settle directly in areas that flooded annually on the coast or the lower river terraces, tropical storms caused heavy damage to crops and water/agricultural systems everywhere, as they do at present (e.g., Hurricane Katrina). Farmers repaired small-scale systems on their own. Large-scale ones, however, required organization and capital to repair, something that Maya kings provided (Lucero n.d.b).

A final seasonal issue that had an impact on farming schedules is when the rainy season actually began. In any given area in the lowlands, the beginning of the rainy season could vary by up to five months, and the annual rainfall also varied (Gunn et al. 2002). If the rains came later than expected, planted seeds rotted. If they began earlier than usual, seeds did not germinate. And there was always the risk that farmers might not burn their milpa fields early enough before the rains began; wet brush does not burn easily, if at all.

I contend that Maya kings provided water during annual drought through maintaining water systems and/or provided capital when water/agricultural systems and crops were lost to storm gods. Rulers brought people together by sponsoring public events that derived from household, agricultural, and water rituals that highlighted their special abilities in reaching gods and ancestors. As a result of this strategy, common farmers participated in creating their own subordination, not to mention debt relations.

History of Maya Rulership

The Preclassic (ca. 1200 BC–AD 250)

The Middle Preclassic (ca. 1200–250 BC) is characterized by the migration of Maya peoples into formally unoccupied inland areas (e.g., the Petén) from riverine or coastal areas (Ford 1986:59, 80–82).1 Tikal and its core area, located in the deep interior of the Petén, were one of the last regions settled. This area has some of the richest agricultural soils in the tropical world but has limited water sources; some scholars suggest that some bajos (seasonally inundated swamps) at one time may have been perennial wetlands or even lakes, which may have silted up due to erosion by the beginning of the Classic period (e.g., Culbert 1997; Dunning et al. 1998, 2003, n.d.; Hansen et al. 2002; Pope and Dahlin 1989). Either way, as populations grew, water became a concern.

The earliest southern lowland Maya elites or wealthy families emerged in the Middle Preclassic (ca. 900 BC) as first founders. We also see the first appearance of Olmec iconography, which has implications for rulership later on. Everyone, rich and poor, conducted domestic rites (e.g., at Cuello; Hammond and Gerhardt 1991; Hammond et al. 1991). And the first lithic “eccentrics” appear during this period (McAnany 1995:46). Eventually elites organized the building of monumental architecture, including small temples, often with masks flanking staircases (e.g., Cerros), ball courts (e.g., Nakbé), and platforms (e.g., Cerros, Nakbé, Cuello, Lamanai, El Mirador) (Freidel and Schele 1988; Hammond et al. 1991; Hansen 1998; Marcus 2003; Matheny 1987; Pendergast 1998).

The Maya, however, built water/agricultural systems even before they constructed monumental architecture (Scarborough 1993). The earliest known water systems in the southern Maya lowlands (ca. 1000 BC) are found in northern Belize and consist of “shallow ditches draining the margin of swamps” (Evans and Webster 2001:354; Scarborough 2003:50). Their construction accelerates after 1000 BC, when Maya began to migrate into inland areas lacking permanent water sources. Water systems include wetland reclamation (e.g., Cerros) and “passive” or concave micro-watershed systems where the Maya took advantage of the natural landscape, particularly depressions (e.g., El Mirador, Petén) (Scarborough 1993). Water symbolism also appears in the Preclassic and is associated with early public monumental architecture (Scarborough 1998).

In the Late Preclassic period (ca. 250 BC–AD 250), high-ranking lineages were transformed into royal ones, when rulers may have assumed shamanistic characteristics to mediate between people, ancestors, and gods and became ritual specialists par excellence (Freidel et al. 1993; cf. Stuart 1995:188). Virginia Fields (1989:6) has demonstrated that “the thematic content of the primary symbols of Maya rulership (i.e., royal regalia and titles), whose imagery was rooted in the natural world, reveals a continuity with more ancient Mesoamerican culture [i.e., Olmec].” These include “the depiction of rulers as seated (also embodied in the ‘seating’ glyphic expression for accession), the use of jaguarian imagery to express rulership … and the ‘maize headband,’ which, as the Jester God, becomes a primary icon of rulership among the lowland Maya” (p. 98). The use of the headband suggests to Karl Taube (1995) that Maya kings performed agricultural and rain-making rites.

Centers like El Mirador and Nakbé arose during this time, only to be abandoned by the end of the Preclassic, perhaps because of failed water-management systems as a result of silting-up (Hansen et al. 2002; Scarborough 1993), drought (Gill 2000), or subjugation by more powerful polities (Marcus 2003). If there were perennial wetlands and/or lakes, they also silted up as a result of erosion (e.g., Hansen et al. 2002). Monumental architecture became more standardized (Hansen 1998). For example, the E-Group assemblage makes its debut (Chase and Chase 1995). The first elite tombs also appear in the Late Preclassic (Krejci and Culbert 1995). Inscriptions focused on ceremonial events (e.g., accession), which were carved or painted on portable objects rather than on public monuments (Mathews 1985; Schele and Miller 1986:109). Individuals were not yet depicted, though the term ahaw (lord, ruler) appeared by the first century BC. The first recorded royal dynasties were founded in the first century AD, at least retrospectively (Grube and Martin 2001).

The Early Classic (ca. AD 250–550)

The Early Classic is characterized by increasing population shifts (e.g., to centers in some areas and abandonment of others) and growth (Adams 1995; Rice 1996). Bruce Dahlin (1983) notes the appearance of defensive works, especially in the northeastern lowlands (e.g., Becan; Webster 1977).

Water storage, especially artificial reservoirs, became particularly important in the Early Classic (ca. AD 250–550), when Maya farmers continued to move into upland areas with fertile land but with few, if any, permanent water sources (e.g., Tikal). Even people living close to rivers such as Río Copán and Río Azul began to build reservoirs and other water systems (Fash and Davis-Salazar n.d.; Harrison 1993).

This period witnessed full-blown Maya rulership. Inscriptions shifted from a focus on ceremonial bloodletting to individual rulers (Mathews 1985; Pohl and Pohl 1994). Genealogical succession and the role of ahaw were firmly established. This fact is ornately portrayed on free-standing public monumental sculpture (stelae and altars), including the first appearance of rulers holding the manikin scepter, a staff symbolizing rulership (Freidel and Schele 1988; Stuart 1996). The Maya built the first royal architectural features (e.g., hieroglyphic stairways and palace complexes) at regional centers, including Copán (Fash 1998), Tikal (Jones 1991), and Palenque (Barnhart 2001). This period “was characterized by states with palaces, standardized two-room temples arranged on platforms in groups of three, royal tombs, and a four-tiered settlement hierarchy …” (Marcus 1998:61).

The earliest rulers arose at regional centers such as Calakmul and Tikal (Marcus 1993) and later at secondary centers. Kings conflated the traditional practice of ancestor veneration with rulership (Gillespie 2000b; McAnany 1995:227). Early Classic deposits became much more diverse in terms of quality, form, and quantity in elite and royal contexts but remained largely the same for nonelite deposits. Rulers emphasized the importance of royal ancestors in the lives of everyone and their close ties to important deities (rain, maize). They conducted ceremonies on palace platforms and the top of tall, multitiered temples overlooking audiences in large plazas. Rulers resolved the increasing numbers of disputes arising over land and water allotment. Corporate kinship relations were no longer adequate to adjudicate disputes involving resources. Kings (for example, at Tikal and Copán) also incorporated foreign themes such as the central Mexican non-Maya rain god, Tlaloc, and other elements from Teotihuacan (Fash 1998; Schele and Miller 1986:213) that demonstrated their esoteric ties and knowledge. Inscriptions tell of monumental building dedications (Schele and Freidel 1990). They also mention conquests and the capture of royal persons, royal visitations, heir accession, bloodletting, and period-ending rites (e.g., katun or twenty years at Tikal, Copán, Yaxchilán, Altar de Sacrificios, and Piedras Negras). Competition between centers became more obvious, as reflected in the iconography, where military themes start to appear (Mathews 1985; Stuart 1993, 1995:133).

“A political breakdown (known as ‘the hiatus’) characterized some, but not all, Petén sites during the Middle Classic, AD 534–593 …” (Marcus 1998:61; Pohl and Pohl 1994), which likely indicates fluctuating political histories, not to mention shifting labor pools (Lucero 1999b). Throughout the Early Classic, competition between centers increased for control over labor, exemplified by the increasingly hostile relations of Tikal, Calakmul, Caracol, and other centers (Chase and Chase 1989).

The Late Classic (ca. AD 550–850)

The Late Classic is characterized by increasing population (Rice 1996), competition, and warfare. Inscriptions leave little doubt as to the prevalence of warfare throughout the Late Classic (Stuart 1995:133, 304), at least in the written records. Victorious Maya kings won over the labor pools of vanquished rulers because of their success on the battlefield.

Water management reached its height in sophistication and scale in this period, epitomized in convex macro-watershed systems where reservoirs, dams, and channels were designed to capture and store water (e.g., Tikal, Caracol) (Scarborough 1993, 2003:50–51; Scarborough and Gallopin 1991). This pattern is mirrored in other water/agricultural systems as well (e.g., Harrison and Turner 1978).

This period witnessed the florescence of political power and royal public rituals, not to mention the continuation of traditional rites in the home. Inscriptions include the elevated status k’ul ahaw (divine or holy lord) (Houston and Stuart 1996; Stuart 1995:189). Inscriptions and iconography also amply illustrate that Classic Maya rulers had close connections to important Maya deities (e.g., lightning’s power, ancestral spirits) and to the otherworld (e.g., Marcus 1978; Peniche Rivero 1990; Schele and Freidel 1990). Rulers often impersonated gods (Houston and Stuart 1996), and their names embodied some of their qualities—for example, K’inich (Sun god) Balam (Jaguar) of Palenque. Other inscriptions tell of “house censing” or “house burning” (Stuart 1998) and illustrate the proliferation of royal or nondomestic rites, in addition to pan-Maya ones, that included ball games, royal marriages, period-ending rites, royal anniversaries, royal visitations, heir accession, sacrifice of royal captives, bloodletting, and other rites not yet understood (fish-in-hand, flapstaff) (Gossen and Leventhal 1993; Schele and Freidel 1990; Schele and Miller 1986). Late Classic ritual deposits demonstrate great diversity in terms of form, quality, and quantity—at elite and royal structures at least. The most powerful kings were entombed in funerary temples facing large plazas that could hold thousands of people (McAnany 1995:51).

Scenes on Late Classic polychrome vessels depict royal rites and ritual dances taking place “on the spacious stairs and upper terraces of the palace complex” (Reents-Budet 2001:202). These buildings faced plazas where large numbers of people could watch and participate in ceremonial events. Scenes on vessels and other iconography also depict feasts, banquets (Reents-Budet 2001), and tribute payments to rulers (Stuart 1995:365). Such payments are “often represented by Spondylus shells attached to heaped mantles” and “quantities of cacao beans” as well as “heaps of tamales and bowls of pulque” (Houston and Stuart 2001:69). Rulers were also depicted alongside gods, indicating their near-divine status: “These symbols of supernatural identity strongly suggest that rulers had significant priestly functions in the making and celebrating of stations of the calendar, a function that was central in defining their ritual responsibilities …” (Stuart 1995:199).

The Terminal Classic (ca. AD 850–950) and Early Postclassic (ca. AD 950–1200)

The Terminal Classic is characterized by “disintegration,” whereby the Maya abandoned most centers (see Demarest et al. 2004b). At an early stage, however, smaller centers started to build monuments on their own or, more specifically, independent of major centers (Marcus 1976; Pohl and Pohl 1994). For example, rulers of the small centers of Ixlú and Jimbal, formerly subordinate to Tikal, both proclaimed themselves K’ul Mutal Ahaw (in AD 879 and AD 889, respectively), a title once only used by Tikal’s rulers (Valdés and Fahsen 2004). Farmers left centers—more specifically rulers—or migrated out of the southern Maya lowlands altogether. In addition, architectural evidence from the Petén lakes region suggests a different type of sociopolitical organization or reorganization (Rice 1986). Access to private royal palaces was no longer restricted; there were no large funerary monuments. The majority of the last-dated monumental construction also occurred at this time (e.g., Tikal, AD 869; Piedras Negras, AD 810; Bonampak, AD 790; Yaxchilán, ca. AD 810). And the last known inscriptions at many centers (e.g., Yaxchilán, Palenque, Piedras Negras, etc.) all involve military themes. “At the very moment that cities like Tikal were collapsing, others in Belize (such as Lamanai) and in the Puuc region of the Yucatán Peninsula were ascending to their greatest heights…. And when some cities in Belize and in the Puuc began to decline, there was a new surge in state formation and expansion, particularly in northern Yucatán …” (Marcus 1998 : 62; e.g., Carmean and Sabloff 1996). Many Terminal Classic inscriptions no longer incorporated individual rulers or dynasties but instead emphasized deities (e.g., Chichén Itzá) (Wren and Schmidt 1991).

In addition to what was happening internally, Terminal Classic ceramics, stelae, and architectural evidence indicate that there was also an intrusion of some sort by non-Petén Maya (e.g., perhaps the Chontal Maya), for example, in the Petén lakes region (Rice 1986). Foreign or new/different elements, perhaps from Ucanal in the northeast (Tourtellot and Sabloff 2004), also start to appear in the iconography and architecture at Altar de Sacrificios and Seibal, especially the latter; they include “non-Classic Maya figures, long hair, strange costumes and regalia…. phallic ‘Atlantean’ dwarfs, a ‘Toltec’ prowling jaguar, a circular pyramid, ball courts, radial temples, causeways, a remote stela platform …” (Tourtellot and González 2004:61). David Stuart (1993) suggests, however, that they may represent a new social order where for the first time nonroyal personages were incorporated into monumental or public art, a further sign of changing times. The appearance of nonroyal personages in the iconography also occurred at centers not affected by foreign influences, such as Copán (Fash et al. 2004; Fash and Stuart 1991), which likely was related to the erosion of both resources and political power. However, there were definitely outside influences coming into the Maya lowlands that reflected a political system more susceptible to external penetration due to the increasing sociopolitical disintegration. Whatever the causes, it should be noted that centers that show “foreign” influences, such as Seibal (e.g., last dated monument—AD 889), Altar de Sacrificios (last date AD 849), and other southern centers, went through a period of florescence (albeit brief) when other areas in the interior Petén were crumbling (Culbert 1988; Sabloff 1992; Willey and Shimkin 1973).

In sum, the Terminal Classic period can be described as one where the seams of the political system were coming apart. This system, once supported by a large labor pool, collapsed without the support of people who now were migrating out to other areas or dispersing permanently into the hinterlands. A different story unfolds in the northern lowlands, which experienced a florescence from ca. AD 750 to 1000 (e.g., Carmean et al. 2004; Demarest et al. 2004a).

The Early Postclassic period in the southern Maya lowlands is characterized by smaller settlements; many, if not most, of them are found near permanent water sources. For example, the Maya continued to live in the Belize River valley, although not necessarily in centers (e.g., Ashmore et al. 2004; Lucero et al. 2004; Willey et al. 1965:292), other Belize valleys (e.g., McAnany et al. 2004), wetland areas in northern Belize (e.g., Andres and Pyburn 2004; Masson and Mock 2004; Mock 2004), and near lakes and rivers in the Petén (e.g., Laporte 2004; Rice and Rice 2004) and elsewhere (e.g., Fash et al. 2004; Johnston et al. 2001). For example, population shifted north to Chichén Itzá (Cobos 2004), likely attracted by better opportunities (e.g., trade) and a new ideology originally from central Mexico centered around Kukulcan, the feathered serpent. Trade became more focused on maritime routes involving both subsistence and exotic or prestige goods (e.g., salt production) (McKillop 1995, 1996).

The disintegration of the southern lowland Maya polities, embedded in ritual, water, and resources, also was expressed in the changing focus of public iconography, which is now largely found in the northern lowlands. During the Classic period, there were a number of gods particularly associated with the ruling elite, especially K’awil and God D (Itzamna) (Miller and Taube 1993:99; Taube 1992: 31–42, 78; Thompson 1970:200–233). The main focus on Itzamna dramatically lessened with the political collapse, not surprisingly, since this was a god associated with divination, esoteric knowledge, and writing (Taube 1992 : 31–40). This deity was also connected to the sun, rain, and maize gods (Thompson 1970:210) and, significantly, also had an evil side having to do with the destruction of crops. Thus, what we see in the Early Postclassic period is a different type of religious focus than the one found in the Classic period, which mirrored the political system it formerly legitimized—that is, semidivine rulers versus group rulership (popol na or council house) (Pohl and Pohl 1994).

To summarize the major points in Maya prehistory, notable trends include population growth (steady growth over a millennium; Deevey et al. 1979; Rice 1996) and shifts, changing political histories and competition, and the presence of ornate royal paraphernalia. At the household level, however, things pretty much remained the same, and domestic rites never left the home (e.g., Andres and Pyburn 2004). Political demands and royal rites had been superimposed onto existing systems that in some degree continue to this day. So for the common farmer what changed was the lifting, for a time, of the burden of paying tribute.

Water and Late Classic Maya Political Systems

The scale and degree to which Maya rulers and elites could expand rituals and political power at minor, secondary, and regional centers were largely conditioned by the amount and distribution of agricultural land, seasonal water vagaries, scale of water/agricultural systems, and settlement patterns (Lucero 1999b, 2002a, 2003). In general, kings acquired and maintained varying degrees of political power through their ability to provide water during the annual dry season and capital during the rainy season and to integrate farmers through ritual, especially dedication, ancestor veneration, termination, water, and other traditional rites.

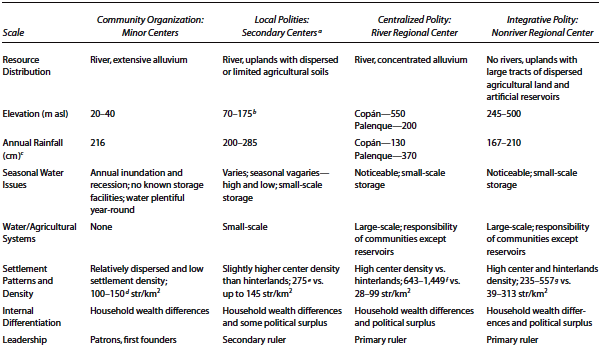

Each center type can be viewed as part of a continuum. The model is a heuristic device to assess political histories at different Maya centers. The types are not static and impermeable; they are fluid and are only an attempt to separate the constituent parts of complex and dynamic systems. Each center has its own specific history; even though this is the case, all Maya, elite or not, lived in a tropical setting that had an impact on their social, economic, political, and religious lives. Structurally, center types are similar to those briefly presented in Chapter 1. The major difference is that in the Maya case we are dealing with one society in one major period. In many cases, centers can be viewed as nested hierarchies, though clearly the histories of how they relate to one another vary by type and particular circumstances. Consequently, some centers were independent entities and others were subsumed under larger polities. This being said, minor centers have features similar to those of community organizations, though typically larger-scale; secondary centers are the same as local polities, regional river centers the same as centralized polities, and regional nonriver centers the same as integrative polities. The factors used to define types (which are detailed in Chapters 4, 5, and 6) are similar to those in Chapter 1 and include resource distribution, elevation, annual rainfall, seasonal water issues, the presence of water or agricultural systems, settlement patterns and density, internal differentiation, leadership, resource access, territorial extent, external relations, political economy, conflict, interaction sphere, type and scale of monumental architecture, scale of integrative events, public iconography, the presence of writing and emblem glyphs, duration, and Terminal Classic events (Table 2.1). While I discuss some factors more than others, I include them all here to provide a more complete backdrop.

RESOURCE DISTRIBUTION: The location of centers with regard to water supply and concentrated, dispersed, or extensive agricultural land bears on population size and density, as well as whether or not resources could produce enough surplus to fund the political economy. Agricultural potential of soil is based on soil fertility, soil parent material, workability, root zone, drainage, slope, and erosion (Fedick 1996).

ELEVATION: This factor relates to precipitation, terrain, temperature, and agricultural soil type (Fedick 1996). It may also relate to whether or not wetlands were perennial or seasonal; for example, Kevin Pope and Bruce Dahlin (1989) note that perennial wetlands are more common in elevations below 80 m asl (above sea level).

ANNUAL RAINFALL: The amount and timing of seasonal rainfall affected agricultural schedules and settlement practices, factors that were critical since the Maya were rainfall-dependent.2

SEASONAL WATER ISSUES: Water shortages during annual drought were particularly problematic, which the political elite used to their advantage. Flooding, hurricanes, and other rain damage also affected settlement decisions, agricultural practices, and political power. The lack of obvious large-scale storage facilities indicates that Maya kings did not provide food during times of need, as was the case for other complex societies (D’Altroy and Earle 1985; Lucero n.d.a).

WATER OR AGRICULTURAL SYSTEMS. Artificial reservoirs, check dams, canals, terraces, aguadas, aqueducts, and ditches reflect local adaptive strategies, as well as the number of people they serviced. Their location (concentrated or dispersed) and scale (small or large) also reflect their role in politics. Small-scale systems are built and maintained at the household and/or community level; large-scale systems are funded or built, or at least maintained, by Maya rulers.

Table 2.1. Late Classic Maya political systems (ca. AD 550–850)

aSome secondary centers may very likely turn out to be regional centers, particularly Yaxchilán and Piedras Negras. Numerous other centers fit into this category; the table lists only sites discussed in text.

bThe elevation of Lamanai differs dramatically—15 m asl. It also has a unique history as it was occupied through colonial times until the seventeenth century.

cMost rainfall data are from Neiman (1997 :Table 15.1).

dLucero et al. 2004; Rice and Culbert 1990 :Table 1.1.

eAshmore 1990; Loten 1985; Rice and Culbert 1990:Table 1.1;Tourtellot 1990.

fBarnhart 2001 : Table 3.1; Rice and Culbert 1990:Table 1.1; Webster and Freter 1990.

gCulbert et al. 1990; Folan et al. 1995. Bajo settlement typically accounts for lower densities.

hThe presence of writing and rulers in public iconography at secondary centers differs from local polities as defined in Chapter 1. However, since I am dealing with the same society rather than different ones, this is not a concern.

iWhile I do not discuss Naranjo, it definitely would fall into this category; other nonriver centers where primary rulers did not emerge due to various historical (political) and material (less agricultural land) circumstances include, for example, La Milpa, Uaxactún, and so on.

SETTLEMENT PATTERNS AND DENSITY: How many people there were and in what manner they were distributed across the landscape affected the ability of leaders to incorporate and communicate with people, not to mention their ability to tap the surplus of others. Estimating population size in the southern Maya lowlands is a relatively contentious topic (see Lucero 1999a). For example, due to the high Late Classic population estimates proposed by some (e.g., Culbert and Rice 1990), Scarborough et al. (2003 :xvi) “suggest that absolute village autonomy during the Classic period was not an option.” However, as I have written and summarized elsewhere (Lucero 1999a), evaluating population size is difficult at best. The lack of refined chronologies (e.g., less than fifty years) does not help matters. Further, we need to take into account the movement of people through the landscape (e.g., seasonal mobility, migration) and structure function (e.g., percentage of specialized structures vs. domiciles such as workshops, religious structures, sweat houses, field houses, storages structures, kitchens, and administrative buildings). In addition, there are “invisible mounds,” which are difficult to identify in the archaeological record (Johnston 2004b; Pyburn 1997). For present purposes, I use structure densities, a relative measure that is easier to compare among sites. Whatever the population size, there is no doubt that the highest population numbers and densities occurred in the Late Classic period (Rice and Culbert 1990).

INTERNAL DIFFERENTIATION: This factor distinguishes surplus resulting in wealth differences where elites compensated laborers for services rendered from surplus politically extracted without equal compensation.

LEADERSHIP: The more surplus one appropriated without equal compensation, the more powerful one was.

RESOURCE ACCESS: Monopolizing resources provided the necessary wealth to sponsor ceremonies and feasts and create obligatory relations through gift-giving (e.g., debt). Rulers also provided capital to repair public works damaged by the vagaries of weather gods (e.g., flooding and hurricanes).

TERRITORIAL EXTENT: How many people Maya kings politically incorporated from surrounding hinterlands and smaller centers illustrated the extent of their power, as well as providing an idea as to how much tribute they acquired (e.g., de Montmollin 1989:103).

EXTERNAL RELATIONS: This factor relates to the nature of ties with other rulers, whether or not center polities were autonomous (peer/equal or unequal) (e.g., Freidel 1986; Sabloff 1986). While not all relations are political in nature, the more frequent and widespread emblem glyphs and rulers’ names were in the inscriptions, presumably the more powerful they were (Marcus 1976; Martin 2001).

POLITICAL ECONOMY: The amount of surplus that was extracted via taxation corresponds with political power.

CONFLICT: Incorporating more people resulted in more tribute and hence more political power. The scale and motives of Classic Maya warfare are also contentious topics in Maya studies (Webster 1998, 2000). Conditions in the southern Maya lowlands jungle—wet and dry seasons, lack of roads, no beasts of burden, no metal armaments, and travel issues—make it difficult to assess the nature of warfare (Webster 2002:223–228). Nor is there an obvious war god, though some gods appear to be associated with violent death and sacrifice (Taube 1992:148–149). However, Stuart (1995:361) notes the clear association of warfare and tribute in the hieroglyphic record. Some battles may have resulted in territorial gain (Culbert 1991; Marcus 2003), especially those fought between centers in close proximity to one another (e.g., in the Petexbatún area; Demarest 1997), but most likely consisted of struggles among elites to gain prestige in the eyes of their supporters (Webster 1998). Maya rulers could not provide much protection per se; commoners protected themselves by escaping to other areas or into the bush.

INTERACTION SPHERE: Elite interaction is expressed through prestige-goods exchange, whereas royal interaction is expressed through prestige-goods exchange plus intercenter alliances and marriages and royal dynastic rites. The way in which and degree to which elites and royals distinguished themselves reflect wealth and power. Interaction also included the exchange of goods between commoners in different communities or centers, typically free from elite interference.

TYPE AND SCALE OF MONUMENTAL ARCHITECTURE: This includes private and administrative palaces, temples (built in several stages over time), funerary temples (built in one major construction event as a tomb for a single ruler), and ball courts. The type and scale of monumental architecture reflects labor organization and control (compensation versus tribute); restricted (royal) versus public activities; and the number of participants.

SCALE OF INTEGRATIVE EVENTS: The scale of ritual activities corresponds to the number of people participating and includes household rites, community small-scale ceremonies, and large-scale public ceremonial and political events. Public events require open areas (plazas). Successfully propitiating supernatural entities guaranteed material rewards for both intermediaries and participants.

PUBLIC ICONOGRAPHY: The predominance of rulers and their ancestors and water symbolism (e.g., Cauac or Witz Monster, Water Lily Monster, fish, crocodiles, water lilies, and turtles) in the iconography clearly signifies their importance in political, social, and religious life.

WRITING AND EMBLEM GLYPHS: Literacy and access to scribes were largely royal prerogatives for the recording of royal events and dynastic histories. The use of emblem glyphs, insignia representing a ruler’s domain (Stuart and Houston 1994), has territorial and political implications.

DURATION: This factor highlights differences between political and occupation histories. Since political demands were superimposed onto existing social and economic systems, they had varied responses to changing political histories. In other words, changing political fortunes may or may not have caused commoner farmers to leave their homes and lands, depending on the circumstances.

TERMINAL CLASSIC EVENTS (CA. AD 850–950): Here I focus on the varied political and social (settlement decisions) responses at different centers to changing climate (see Chapter 7).

In brief, kings of regional polities acquired and maintained political power through their access to concentrated resources and large-scale water/agricultural systems and their ability to integrate densely settled and/or scattered farmers through ritual. Kings at secondary centers acquired power by dominating prestige-goods exchange and nearby agricultural land, but to a lesser extent than regional kings, because they were unable to access all the dispersed pockets of agricultural land, small-scale water/agricultural systems, and scattered farmers. Elites at minor centers could not obtain tribute but relied on their wealth as landowners to procure prestige goods and organize local ceremonies. They did not have much or any political power, because agricultural land was extensive and plentiful, and elites could only integrate farmers in the immediate vicinity. Nor did farmers rely on water/agricultural systems, since water was plentiful year-round; instead they relied on the annual flooding and receding of the river for agriculture. Whether or not they were beholden to rulers at major centers, as members of a larger society, Maya at minor centers interacted and exchanged information and goods with Maya from other areas.

The Classic Maya were similar to other ancient civilizations where water and seasonal issues played a major role in the underwriting of political power and where subjects perceived rulers as protectors and providers. When conditions changed and rainfall decreased, rulers were the first ones blamed. This resulted in their loss of rights over the surplus of others and their primary means of support and, ultimately, in their loss of power. In the next chapter, I set the stage to explain how Maya rulers acquired and maintained the right to exact tribute—through ritual.