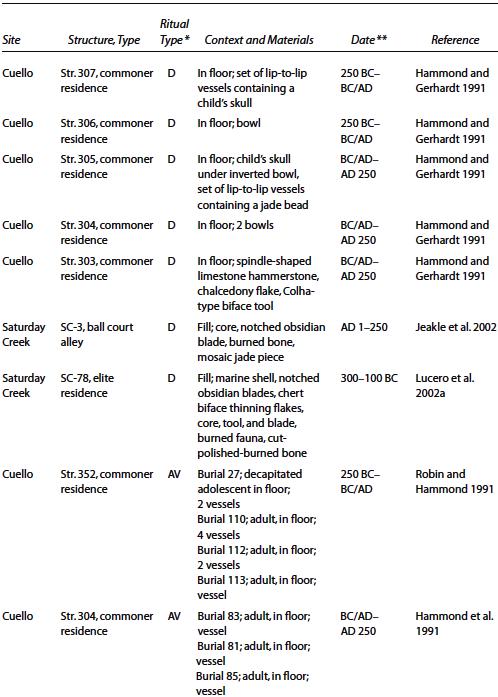

In this chapter I detail the distinguishing features of community organizations (see Table 1.1) and Maya minor centers, which have several factors in common (see Table 2.1). I also present the history of ritual activities at Saturday Creek, a minor river center without rulers or any other royal trappings. My intent is to show that all Maya conducted the same rites, whether or not they were taxpayers, and whether or not they were royal.

Community Organization

In community organizations, farmers live in villages and practice swidden or small-scale intensive agriculture as well as hunt and fish. Relatively low population densities result in fewer demands on the land. Farmers depend on seasonal rainfall and do not rely on water or agricultural systems. Wealth differences exist and are expressed in differential access to resources, exotics, labor, and other goods. Political power typically does not develop, because resources are relatively extensive, stable, and plentiful (e.g., Kirch 1994). Consequently, there is no need for capital to maintain water/agricultural systems, though elites can provide food to people in need from their own stores. Elites typically attain greater wealth as a result of their being the first settlers and monopolizing the best resources (e.g., Carmean and Sabloff 1996; Marcus 1983). As a result, their power lies in the respect they are shown as founding families, for example, in making decisions involving the entire community (e.g., lineage chiefs, village headmen). Land is corporately owned, though chiefs/elites may own other means of production, such as fishing canoes. Relations are typically heterarchical, since wealth differences do not translate into a monopoly on political power. “Heterarchy may be defined as the relation of elements of one another when they are unranked or when they possess the potential for being ranked in a number of different ways” (Crumley 1995b:3). For example, Marajo Island at the mouth of the Amazon was occupied for approximately a millennium, until ca. AD 1100 (Roosevelt 1999:23):

The general picture from the Marajoara cultural remains … is of populous, wealthy, but apparently uncentralized, societies. Their populations lived in sometimes sizable, long-term communities atop large-scale earth constructions, taking sustenance from fish, horticultural crops, and orchards. They created highly elaborate and often monumental art, and craft objects that were available to all residential groups, although in somewhat different quality and quantity.

A major factor that prevented the development of centralized power is that inhabitants of Marajo Island had the option to flee into uninhabited jungle areas.

Elites, as landowners or owners of other critical resources, compensate people for goods and services rendered, including manufacturing prestige goods, working elites’ land, and building their homes, shrines, and community structures (e.g., ritual architecture). Compensation comes in the form of food and access to resources and/or prestige goods, which the elites obtain as participants in a regional elite interaction sphere (long-distance exchange). Commoners, however, also are involved in the exchange of utilitarian and prestige items with their cohorts, typically without elite interference. An element of choice is involved since people can choose for whom and when to perform tasks for others who can afford to pay. Patron-client relations can fall in this category, even though over time clients may have little choice but to work for a patron due to debts owed. Patrons, however, also have obligations to their clients to take care of them in times of trouble or need.

A key issue is that there is more than one wealthy individual or family rather than a sole political leader (Fried 1967:26–32; Marcus 1983). To promote solidarity in the face of wealth differences, however, elites sponsor community feasts, performances, and religious rites and organize the building of small-scale public works (e.g., religious structures, terraces, and canals). These activities also serve to increase their prestige as pillars of the community. Household rites typically involve ancestors and fertility, since they are critical to everyone’s survival (Fried 1967:138). Ancestors are typically represented in a stylized manner in various media, such as body decoration, sacred items, shields, and banners (e.g., clan totems or emblems) (Durkheim 1995 [1912] :111–117). People have no need of writing or recording systems, because each lineage is responsible for maintaining and passing on family oral histories.

Communities may or may not interact with a centralized or integrative political system. For example, rulers of the Kedah state in Malaysia (AD 700–1500) had peer relations with foreign trade partners (e.g., from China, Vietnam, Thailand, and India) and equal, heterarchical relations with inhabitants of the forest far upstream, with whom they exchanged foreign goods for forest products (e.g., timber) necessary for trade (Allen 1999). Whether or not they interact with larger polities, small-scale raiding for food and land (and some political reasons) is endemic but regulated (Fried 1967:178). Feuding is kept in check by lineage elders, village headmen, and any other person of respect (e.g., Leach 1970 [1954] : 184–185). There are various reasons why elites do not have much political power in addition to the material factors mentioned above. David Small (1995) discusses how external trade can prohibit the development of hierarchical organization, because opportunities to participate are open to all. For example, the kula ring (interisland trade) of the Trobriand Islands is accessible to all men for trading and creating alliances (Johnson and Earle 2000: 272). Other social organizations that keep relations nonhierarchical are kinship systems, age-sets, and specialists (magicians, sorcerers, rain-makers), as found among several precolonial African societies, including Tellensi farmers and Nuer and Logoli Bantu cattle herders and farmers (Evans-Pritchard 1940; Fortes 1940; Wagner 1940).

Communities are stable and have lengthy histories, as long as there are enough resources to sustain people and as long as people can adapt to changing conditions (e.g., long-term climate change). And “because of their broader, grassroots base, heterarchical formations appear to achieve more political stability and cultural longevity than hierarchical systems imposed from above by small ruling groups” (Roosevelt 1999:14). For example, in the Maya lowlands, many communities continued long after the collapse of the political hierarchy, with little change. At Laguna de On in northern Belize, Marilyn Masson (1997) posits that communities rather than the earlier civic-ceremonial centers became the focal point for political, social, and economic organization.

I illustrate a community organization through a brief description of the Trobriand Islanders (Johnson and Earle 2000:267–280). The Trobriand Islands are located north of New Guinea, with unvaried resources. Islanders practice intensive agriculture (e.g., taro gardens) and fish. However, they do not build water/agricultural systems. Important staples are yams, which are stored, and taro. They are dependent on seasonal rainfall, and periods of drought can result in famine. When this happens, chiefs’ stores of yams become critical. Trobriand Islanders live in village clusters, and chiefs reside in larger villages. Each lineage (dala) has a chief, and the lineages are ranked. Chiefly lineages are wealthier than other lineages, indicated by their larger houses and storage facilities. They acquire part of their wealth through dowry, a particularly lucrative strategy, as chiefs have several wives—not to mention more alliances and exchange partners. Chiefs also own canoes necessary for fishing but do not own land. Land is corporately owned by each dala. Consequently, there are no chiefly territories per se, only alliances and ties with nearby villages. Some men have the means and connections (alliances) to participate in the kula ring for subsistence and prestige goods (see Malinowski 1984 [1922]), which they exchange with people who do not participate in the kula ring. Chiefs, while they do not necessarily acquire tribute, do demand payment for use of their canoes and for food provided during famine. Raiding can occur during times of famine as well as for “political purposes” (Johnson and Earle 2000:271).

Household and village rites revolve around ancestors and clan totems (Malinowski 1984 [1922] : 63, 72–73). Garden magicians and other ritual specialists act for the entire community, and each village has one (p. 59). Public rites take place in open, ceremonial areas, located in chiefly villages. Ceremonies involve the ancestral spirits critical to Trobriand life (pp. 421–424). Symbols represent clam totems, spirits, and witches (e.g., Anderson 1989 [1979] : Figure 5.3).

The Trobriand Islanders traditionally live in a relatively stable society because they do not over-use resources and have social mechanisms to offset food shortages and other seasonal problems (e.g., sharing stored foods).

Such societies have several factors in common with the Maya who lived in minor centers during the Late Classic (ca. AD 550–850), particularly the lack of political leaders and material conditions that were not conducive for the emergence of rulers.

The Maya: Minor Centers

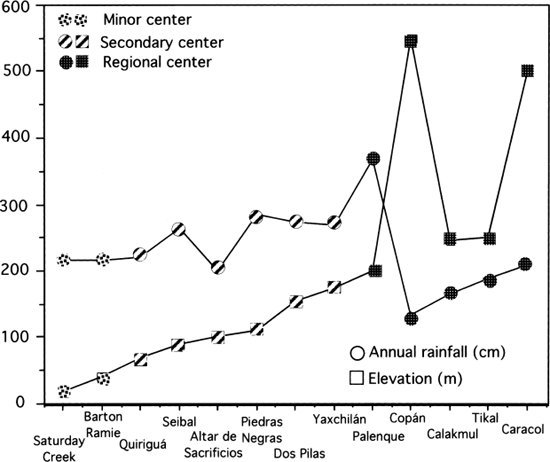

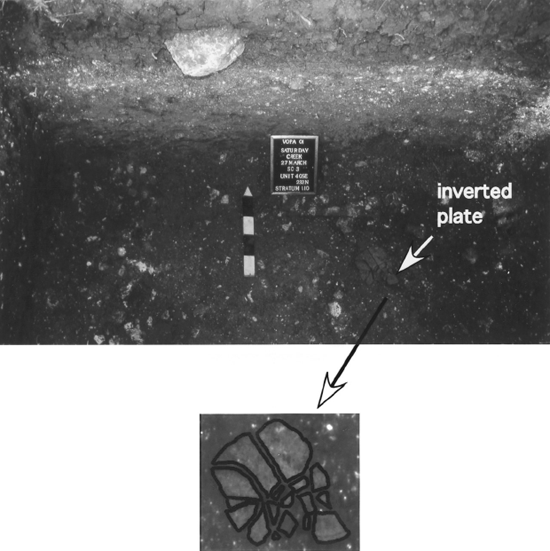

Minor centers such as Barton Ramie and Saturday Creek are located on the Belize River on a relatively broad alluvium (1–2+ km wide) on the eastern periphery of the southern Maya lowlands (see Figure 2.1). They appear to be some of the earliest and longest-occupied settlements (e.g., 900 BC–AD 1500), which is not surprising given their prime location in an area with plentiful water and land. These centers are located in lower elevations (20–40+ m asl) and have higher annual rainfall than the majority of regional centers (Figure 4.1)—216 cm at Saturday Creek, similar to that of Barton Ramie, 25 km away. The naturally moist alluvial soils on the terraces above the river are excellently suited for cash crops such as cacao and cotton (Gómez-Pompa et al. 1990), not to mention maize, beans, and squash. The relatively dispersed settlement suggests that ancient Maya farmers planted fields interspersed among their houses (Drennan 1988; Killion 1990) or that landlords or estate owners living in the center or absentee limited settlement and set or determined planting schedules. Farmers did not need to use water/agricultural systems, because water was plentiful; farmers relied on the annual rising and subsiding of rivers for agriculture (recession agriculture). Annual inundation of the poorly drained soils of the lower terraces deterred the Maya from building or planting too close to the river. For example, at Saturday Creek occupants lived dispersed on the upper terraces along the Belize River and avoided the lower, poor-draining terraces that are seasonally inundated (Lucero n.d.b).

Figure 4.1. Elevation and annual rainfall at southern Maya lowland centers

The Belize valley, due to its location and elevation, also benefited from annual runoff from Guatemala, Mexico, and western Belize, which supplied enough water for everyone throughout the year. The downside of runoff is that it often results in flooding and the deposition of clayey soils, which can remain saturated for most of the year. For example, in 1998 at Saturday Creek the lower river terrace was inundated during May and June, the end of the dry season. In May and June of 1999, however, the lower terrace was completely dry. The lower terrace was also devoid of prehispanic settlement, suggesting that the terrace was frequently inundated in the past. The Maya probably planted several crops a year as farmers do at present, indicating a lesser need for storage, which would explain why we do not find evidence for storage facilities (Lucero n.d.a).

These communities were composed of relatively low densities of dispersed farmsteads (e.g., 100–151 structures/km2; Lucero et al. 2004; Rice and Culbert 1990:Table 1.1; Willey et al. 1965:573). A major factor preventing elites from acquiring political power was their inability to restrict plentiful water and extensive alluvium and integrate dispersed farmers. Further, even if elites owned all the land, farmers clearly had the option to leave if elite demands became too onerous. Not relying on water/agricultural systems meant that there was no need for farmers to rely on the benevolence of political leaders to supply capital to repair damage. Communities, however, may have been subsumed under a regional polity, depending on factors such as distance from major centers and accessibility (e.g., Scarborough et al. 2003). For example, Olivier de Montmollin (1989:203) suggests that some valley areas around Tenam Rosario in the Usumacinta lowlands might have been elite or royal cotton and cacao estates. This might have been the case in other valley areas. Current evidence does not indicate involvement in warfare; if inhabitants did participate in aggressive acts against others, their involvement likely related to whether or not they were involved in regional politics.

Wealth differences account for various-sized residences and other signs of wealth rather than political power (e.g., Carmean and Sabloff 1996); elites compensated the workers who built their larger homes and worked their fields rather than exacted tribute (e.g., with prestige goods and access to land) (e.g., Potter and King 1995). Elites attained their wealth as a result of being the first settlers and owning the best and/or the largest plots of land; they acquired status as founding families, which was expressed by how members reacted to their community-wide decisions (e.g., Carmean and Sabloff 1996; McAnany 1995: 96–97; Tedlock 1985:204–205; Tozzer 1941:25–26). Consequently, greater wealth was not concentrated in the hands of one person or family but dispersed among several elite families. Elites participated to some degree in the elite interaction sphere through personal ornamentation, ceremonies, and long-distance exchange (e.g., exotic goods such as small jade and obsidian items) (Chase and Chase 1992).

Farmers and elites also traded their produce with Maya living in different areas. For example, in the upper Belize River area, there is evidence that valley farmers, who may or may not have been beholden to rulers at the nearest centers of El Pilar or Yalbac, acquired ceramic vessels and chert tools from Maya living in the foothills. The foothills have less productive agricultural soils, but plentiful raw materials for ceramic and lithic production (chert outcrops, clays, and tempers) (Ford 1990, 1991a; Lucero 2001:65–67). This type of exchange took place without elite interference (e.g., Scarborough et al. 2003). Consequently, even if Maya at minor centers were not integrated within a larger political system, they still interacted with their peers in other areas; after all, they were still members of a broader society and so identified themselves by acquiring value-laden items recognizable throughout the Maya world.

Elites sponsored local small-scale public rituals and feasts at small temples, usually not exceeding 10 m in height and relatively small plazas, and organized the construction of public works to promote solidarity in the face of wealth differences (Arie 2001; Lucero et al. 2004). Maya farmers also conducted rites in their homes, agricultural fields, and sacred places (e.g., caves and water bodies). There is no obvious public iconographic evidence for water imagery or rulers at such centers, which, by contrast, is pervasive on monumental architecture, sculpture, and mobile goods at some secondary and all regional centers. Elites did not keep a written record; nor did they have the means, or right, to make use of emblem glyphs.

Terminal Classic (ca. AD 850–950) events were pretty much the same as during the Late Classic. Minor centers were stable and lasted as long as there were enough resources to sustain people (Lucero 2002a). For example, the Maya occupied Saturday Creek and Barton Ramie long after they deserted secondary and regional centers, though population size gradually decreased throughout the Postclassic (ca. AD 950–1500) (Conlon and Ehret 2002; Willey et al. 1965). The long occupation histories (ca. 900 BC–AD 1500) raise the question as to why rulers did not emerge, an issue I address in Chapter 7.

Ritual History of Saturday Creek

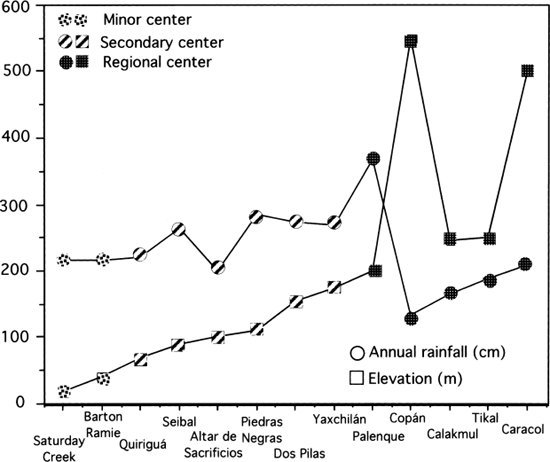

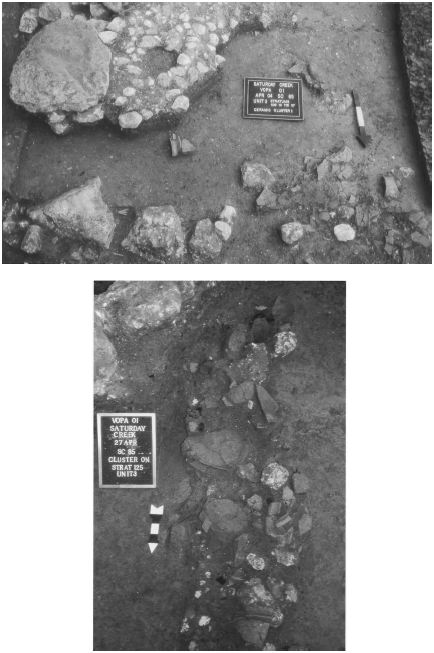

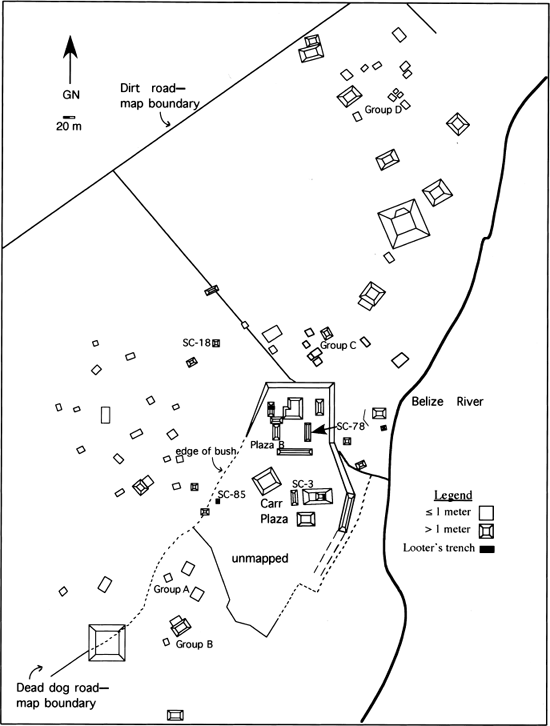

Saturday Creek is located along the Belize River on an extensive floodplain (20 m asl) in central Belize on the eastern periphery of the southern Maya lowlands (see Figure 2.1).1 Settlement was dispersed (100–151 structures/km2; Lucero et al. 2004) and consisted of solitary mounds (67%, n = 53), mound groups or plazuelas, a ball court, and small temples (up to ca. 10 m tall) (Figure 4.2). The Valley of Peace Archaeology (VOPA) project, which I directed, mapped 79 structures within a 0.81 km2 area bounded by roads on the north side of the river. Most of the site is located in a plowed field that is currently intensively cultivated by Mennonite farmers; they plow it at least twice a year and plant maize, beans, watermelon, or black-eyed peas. Consequently, mounds in the plowed field have been reduced in height and spread in areal extent. A large portion of the site (ca. 350 × 300 m), including the center core, has not been plowed. The core area has not been mapped in its entirety due to dense secondary growth (noted in Figure 4.2). Saturday Creek’s former inhabitants included farmers, part-time specialists (e.g., potters had ample supplies of clay and water), and elite landowners. Elites procured exotics, such as obsidian and jade items, albeit small and simple ones. Commoners also acquired these objects but in even smaller sizes and quantities—either as gifts or compensation from elites or through exchange with peers in other areas. Elites also organized the building of the ball court and temples.

Figure 4.2. Saturday Creek

There were no rulers, no tribute payments, no water or agricultural systems, no royal palaces, and no inscriptions; neither did Saturday Creek’s residents create public iconography or use emblem glyphs. Saturday Creek was a stable and long-lasting community that was occupied from at least 900 BC through AD 1500 (Conlon and Ehret 2002). The nearest center is Yalbac, a secondary center 18 km to the northwest, and inhabitants of Saturday Creek may have had some kind of interaction with them. Even if the Maya at Saturday Creek were not politically incorporated into a larger polity, they were without question members of a larger society and interacted through social and economic exchanges (e.g., lithic tools from foothill or upland areas). Surface collections and excavated materials from Saturday Creek residences and from houses up-river indicate their relative wealth, not to mention long-distance contacts (e.g., Pachuca obsidian from central Mexico, polished hematite items, jade, and marine shell) (Lucero 1997, 2002b).

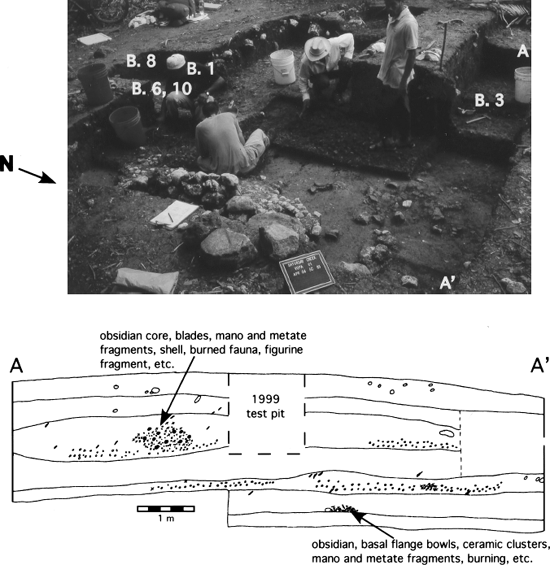

To maximize the range of ritual activities, in 2001 we excavated several structure types: two solitary mounds or commoner residences, SC-18 and SC-85; an eastern structure of an elite compound, SC-78; and a temple ball court, SC-3 (Lucero 2002b) (see Figure 4.2). In general, at each structure we began by bisecting the mound with a 2-meter-wide trench. At the two solitary mounds, we then horizontally exposed several living floors, excavating about 60% of SC-18 and 75% of SC-85. The large size of SC-78 only permitted us to bisect its width with a 2-meter-wide trench and excavate several 2 × 2 m test pits placed within structure rooms (determined using post-hole testing). This method resulted in our exposing about 20% of the mound. We excavated a 1-meter-wide trench at SC-3, bisecting the temple, platform, and ball-court side wall and alley.

We excavated following natural stratigraphy and used the Harris Matrix method of recording strata to highlight depositional sequences (see Harris 1989). Ceramic analysis was conducted concurrent with excavations resulting in chronologies for each mound in 100- to 200-year increments (Conlon and Ehret 2002). Analysis particularly focused on ceramic assemblages and their contexts because the Maya used them as ritual paraphernalia for dedicatory caches, grave goods, and termination deposits (Lucero 2003).

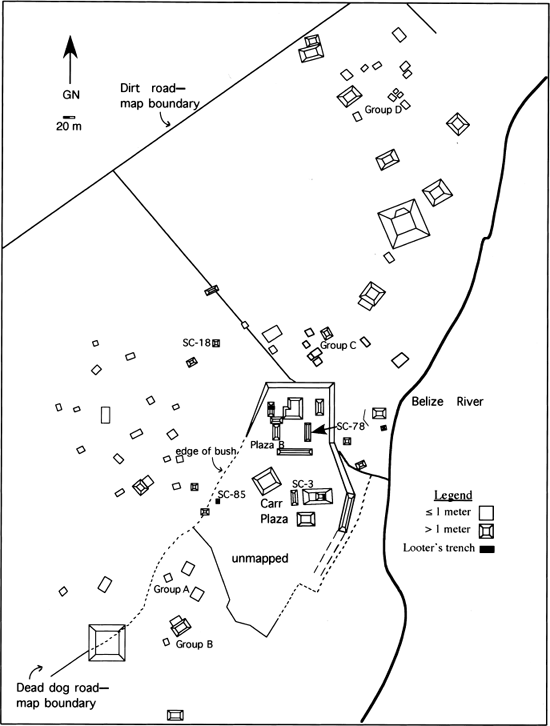

SC-18 (10 × 8 m, 1.24 m high) (Figure 4.3) is a commoner residence located ca. 150 m northwest of the site core on prime alluvium. It has at least six construction phases dating from ca. AD 400 through 1150 (Lucero and Brown 2002). The Maya constructed several thin plaster floors (most with cobble ballasts 2–5 cm thick), one on top of the other. Single or double-course boulder walls provided the foundation for thatch or wattle-and-daub structures. Some of the boulders were faced on the side facing inside. It has been plowed several times, and we do not know how much of the mound has been sheared off.

Figure 4.3. Commoner residence SC-18 with foundation walls and floors (in the sidewalls) visible; the locations of burials mentioned in text are noted. The east wall profile highlights some of the ritual deposits mentioned.

The occupants of SC-18 apparently were relatively well off farmers who acquired exotics, including small obsidian objects, jade inlays or mosaic pieces, and worked and unworked marine shell, hematite, and slate items. We also recovered a celt, bark beater, spindle whorls, bone needles, and a candelario.

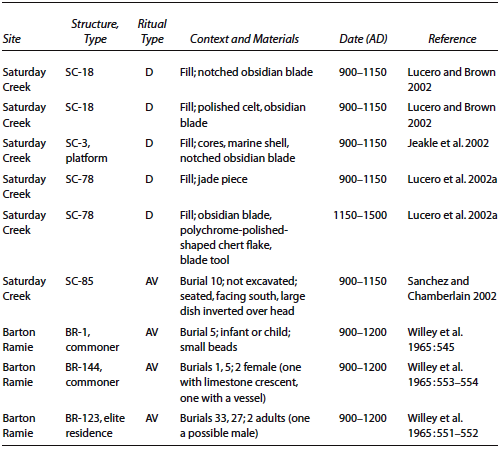

SC-85 (6 ×4 m, 1.34 m in height) (Figure 4.4) is a commoner house located ca. 100 m southwest of the site core on more clayey soils. It also has six construction phases, consisting of a series of thin plaster floors with less substantial ballasts, one cobble surface, earthen surfaces (the earliest), and unshaped foundation boulder walls (one to three courses) for wattle-and-daub structures (Lucero, McGahee, and Corral 2002). We recognized five of the six surfaces by their termination deposits rather than plaster floors; the surrounding clays erode plaster. The Maya occupied SC-85 from at least ca. AD 400 through 1150. It is located in an area of secondary growth just east of the plowed Mennonite fields and does not appear to have been plowed.

Figure 4.4. Commoner residence SC-85 with a cobble surface visible as well as a termination deposit. The north wall profile highlights some of the ritual items mentioned.

Residents of SC-85 were less wealthy than their counterparts at SC-18, a result of their having lived surrounded by clayey, less productive soils. The Maya that lived here, however, acquired exotics and other specialized items, albeit small and simple, including Colha chert tools, worked and unworked marine-shell objects, obsidian blades, jade inlays or mosaic pieces, and hematite items.

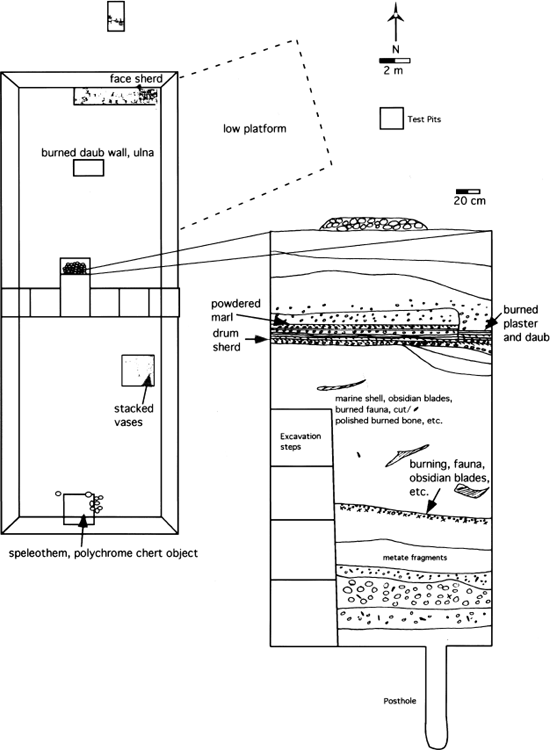

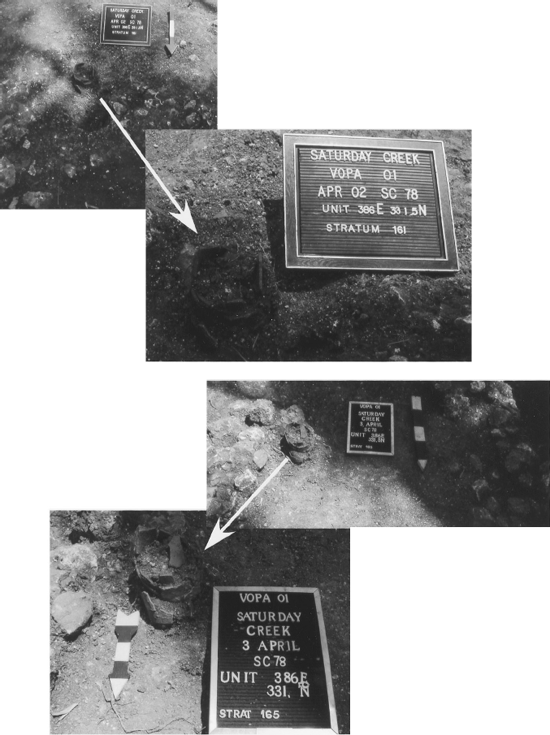

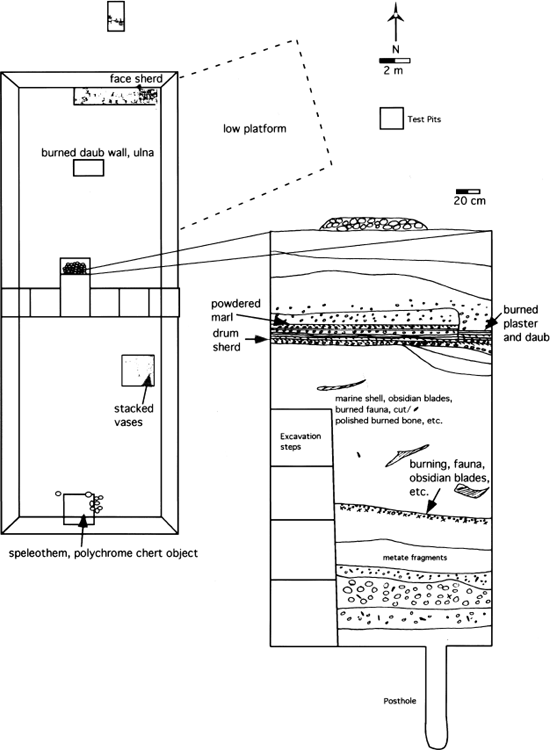

SC-78 (Figure 4.5), the eastern structure of an elite plaza group in the site core up on one of the terraces, consists of a stepped platform (29.4 X 9.5 m, 3.85 m in height) with several relatively substantial domestic and specialized structures, especially on its north side. Some structures have thick plaster floors, ballasts, and standing walls with cut stone blocks. The Maya also used wattle-and-daub buildings (Lucero, Graebner, and Pugh 2002). It has not been plowed, as far as we know, but was being used as a milpa in 2001. The Maya lived at Saturday Creek at least by 600 BC through AD 1500, though ceramics dating to ca. 1000 BC were found in lower fill contexts. While domestic artifacts were recovered from several contexts, their frequency and density are noticeably lower than at SC-18 and SC-85. Their relative scarcity might indicate that fewer people lived here and/or that some structures had specific functions (e.g., a kitchen, storeroom, work area, shrine, or sweat bath).

Figure 4.5. Plan of SC-78 and the north wall profile from the center excavation unit.

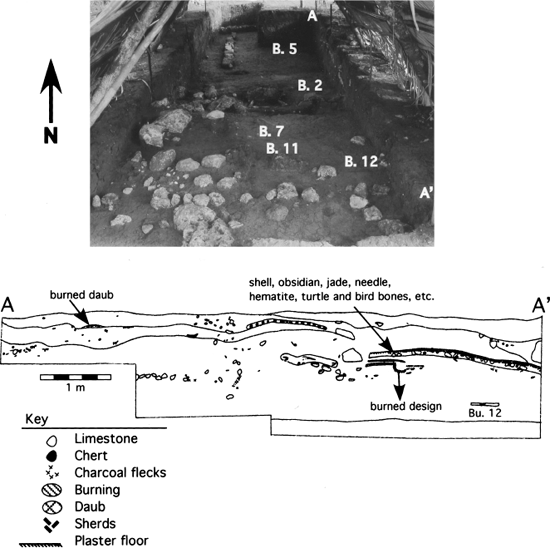

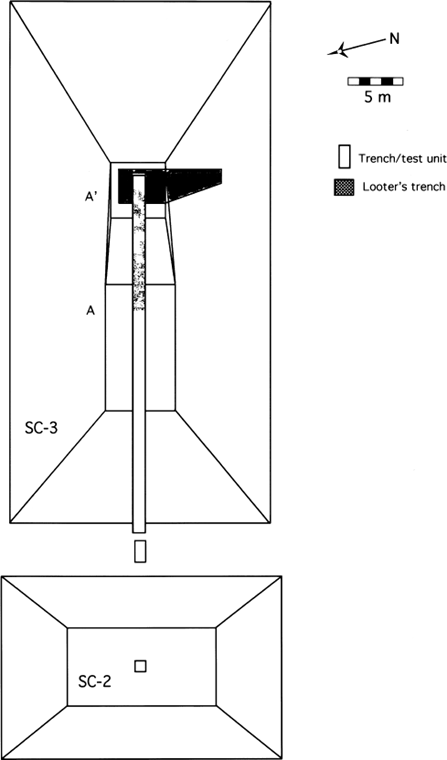

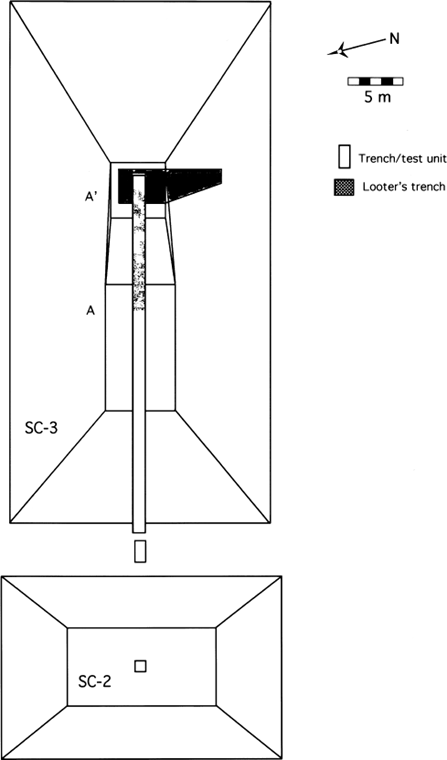

SC-3 (Figure 4.6) is a temple (5 × 5 m, 2.44 m in height) oriented 10° west of north on top of a stepped platform (48 × 24 m, 3 m in height). It lies in the site core surrounded by two plazas and has not been plowed. The last major construction phase of the temple consists of a stone façade with a clay fill; some blocks are shaped, and some surfaces are plastered. We exposed an additional ten strata. A large looter’s trench runs from the far northern edge of the temple down to the southern edge of its substructure or platform, extending about 10 m roughly north-south, 1.5 m to 3.5 m wide and from 1 to 2.5 m deep. The western side of the platform contained the eastern half of a ball court (Jeakle 2002; Jeakle et al. 2002).

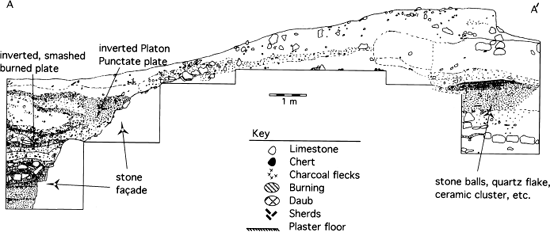

The 1-m-wide excavation trench revealed several major construction phases, including steep, tiered walls and a platform with several construction phases and plastered steps (Figure 4.7). Due to time constraints, we were not able to reach sterile at SC-3. Excavated material, however, dates from at least ca. 300 BC to AD 1500, though ceramics dating as early as 600 BC were found in fill deposits. We also excavated a 1 × 1-m test unit on the top center of SC-2 (26 × 17 m, ca. 3 m high), the western half of the ball court, which likely dates to the Late Classic period.

Due to the relatively limited extensive excavations undertaken at Saturday Creek, I use ritual data from other comparable sites (Barton Ramie and Cuello) to illustrate that dedication, ancestor veneration, and termination rites have a long history extending from before rulers to after they had long disappeared. I have no doubt that further excavations at Saturday Creek would have yielded ritual evidence similar to what I present from other sites.

The Preclassic (1200 BC–AD 250)

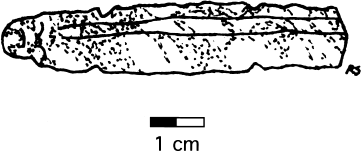

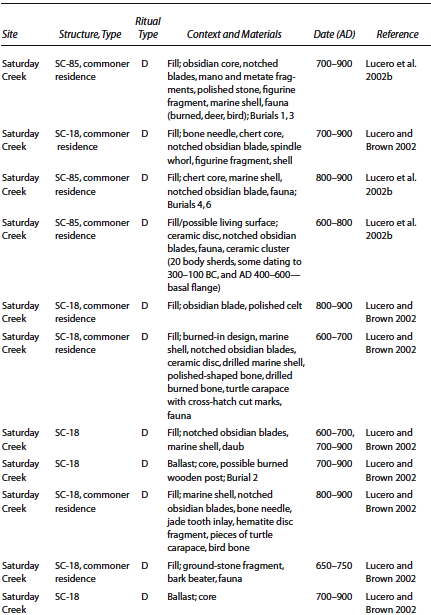

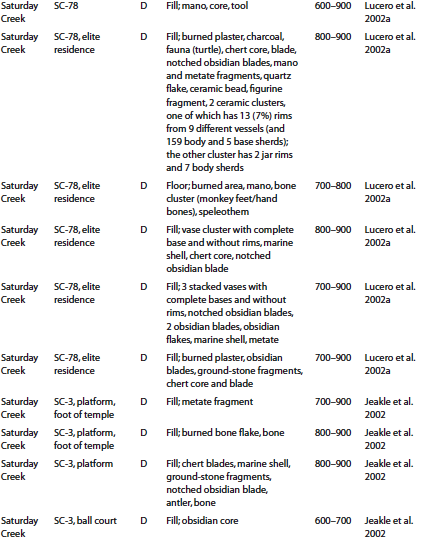

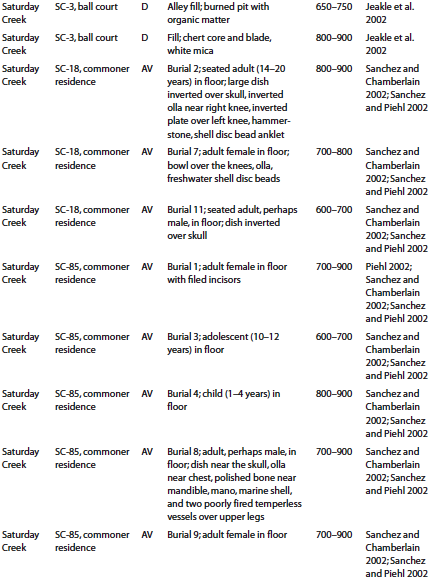

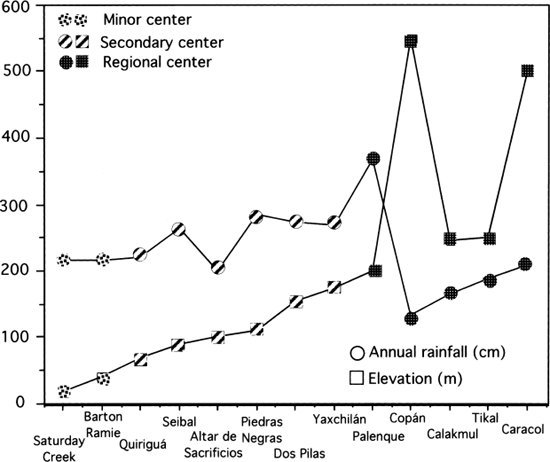

The only clear evidence for dedication rites at Saturday Creek occurs at the elite structures (Table 4.1), which in all probability began as commoner structures, or at the very least houses not distinguishable from other early residences. Construction fill of commoner houses from the small, early secondary center of Cuello in northern Belize between the New and Hondo Rivers, however, yielded several caches—from a single bowl and a spindle-shaped limestone hammerstone, chalcedony flakes, and a biface tool to two pairs of lip-to-lip vessels, one containing a child’s skull and the other a jade bead (Hammond and Gerhardt 1991) (see Figure 2.1; this area is little more than 10 m asl, and water is abundant; one can just dig a little and hit water almost anywhere). At SC-78, the elite residence, the thick clay construction fill, dating from 300 to 100 BC, yielded a dedication cache that included marine shells, a cut and polished burned bone, notched and unnotched obsidian blades (Figure 4.8), biface thinning flakes, a chert core, tool, and blade, and burned faunal remains (Lucero, Graebner, and Pugh 2002) (see Figure 4.5). In the ball-court alley fill at SC-3 we recovered a chert core, a notched obsidian blade, burned bone, and a mosaic jade piece.

Figure 4.6. Plan of SC-3.

Figure 4.7. North wall profile of temple and platform SC-3 (A-A').

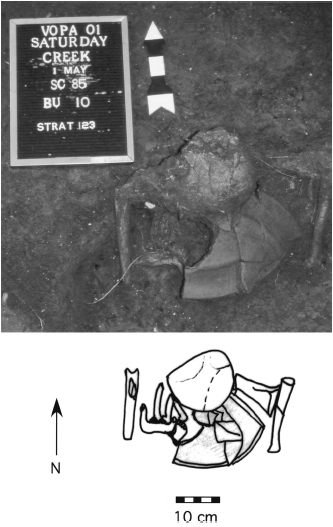

No Preclassic burials were recovered at Saturday Creek, but burial data from the small secondary center of Cuello provide some of the best evidence available for Preclassic burial patterns. During the Early Middle Preclassic (1200–700 BC), most burials are located in house floors along with shell, ceramics, and some jade items (Hammond 1995, 1999). A common grave good consisted of an inverted bowl placed over the head. In the Late Middle Preclassic (700–400 BC) jade is found only in burials of males. In addition, burials start to appear in ancillary structures and community plazas. Finally, in the Late Preclassic (400 BC–AD 250), a large platform became the major locus for ceremonial activities and elite burials, the majority of which are males buried with exotic goods (Hammond et al. 1991; Robin and Hammond 1991). Domestic burials, in contrast, remained similar to those of earlier periods, usually including inverted vessels over the head as well as more diverse and exotic goods.

Barton Ramie, a minor center along the Belize River similar to Saturday Creek and heavily plowed by Mennonite farmers, also yielded Preclassic elite burials. For example, the elite residence BR-123 (33 × 23 m, 2.75 m high) had some of the earliest “lavish” burials in the Belize Valley, dating to ca. 100 BC–AD 250, including some of the earliest Maya polychrome pottery and jade beads and pendants (Willey et al. 1965:531). Burial 30, an adult male, was buried with three vessels, a jade bead, two shell discs, and forty Spondylus shell beads (p. 551).

Table 4.1. Preclassic ritual deposits

*D = Dedication;AV = Ancestor Veneration;T = Termination.

**Saturday Creek dates were determined using ceramic chronology (type-variety) (see Conlon and Ehret 2002).

The only Preclassic termination rituals at Saturday Creek consisted of smashed and burned sherds at the foot of the temple (SC-3) dating to 100 BC–AD 250 and at SC-78 on floor surfaces (burned sherds and areas, obsidian blade and chert tool fragments, and mano and metate fragments). However, there is solid evidence for domestic termination rituals at Cuello. Throughout the several construction phases of residences (and temples), the Maya burned floors and destroyed architectural features by at least 900 BC (Hammond et al. 1991). Later the Maya would scatter jade beads on some burned residential surfaces (e.g., Str. 317).

Figure 4.8. Example of a notched obsidian blade. Drawing by Rachel Saurman.

The Early Classic (ca. AD 250–550)

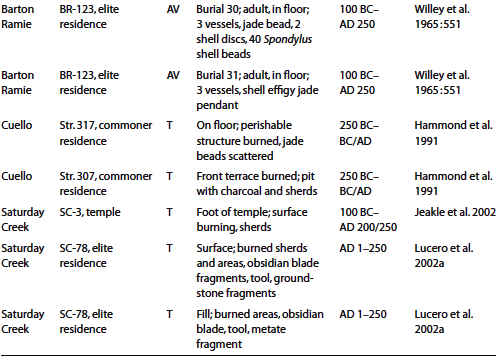

At the commoner residence SC-85, dedicatory fill deposits dating to ca. AD 400–600 yielded chert cores, marine shell, notched and unnotched obsidian blades, drilled marine shell, faunal remains, mano and metate fragments, perforated sherds, and ceramic sherd clusters (Lucero, McGahee, and Corral 2002) (Table 4.2). In addition to the same items listed above, elite caches at SC-3 and SC-78 included speleothems (stalagmite or stalactite fragments from caves, considered sacred to the Maya as portals to the underworld or Xibalba), chalcedony and obsidian cores, quartz pebbles, stone balls, and a concave sherd containing human phalanges, some of which were twisted and deformed (Jeakle et al. 2002; Lucero, Graebner, and Pugh 2002). A partially reconstructible Early Classic (ca. AD 290–550) polychrome plate was found in the fill of the temple superstructure (SC-3).

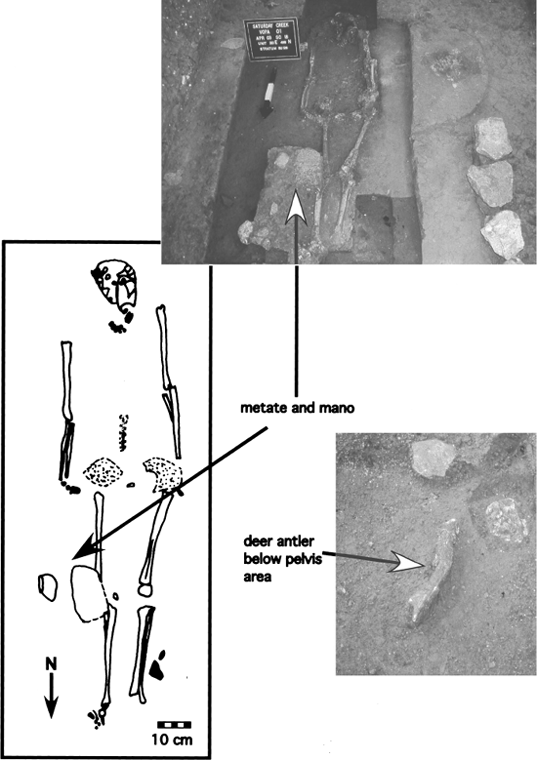

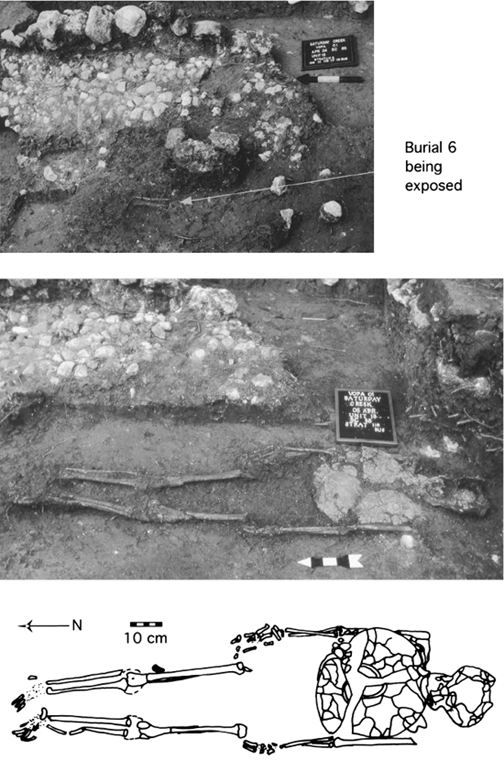

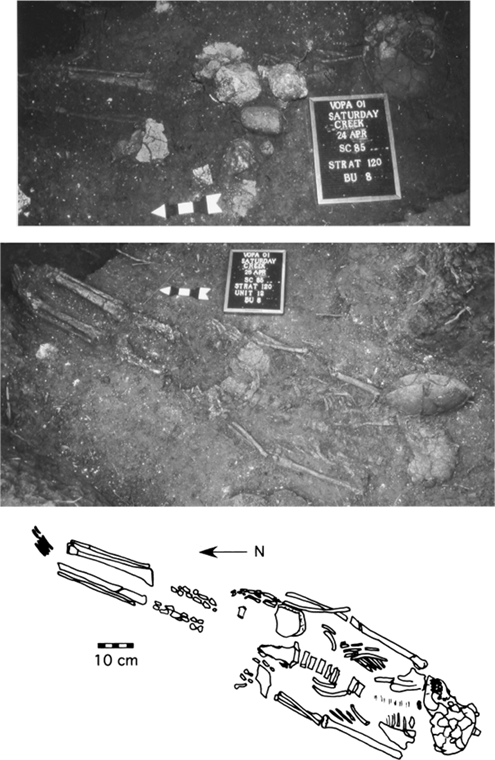

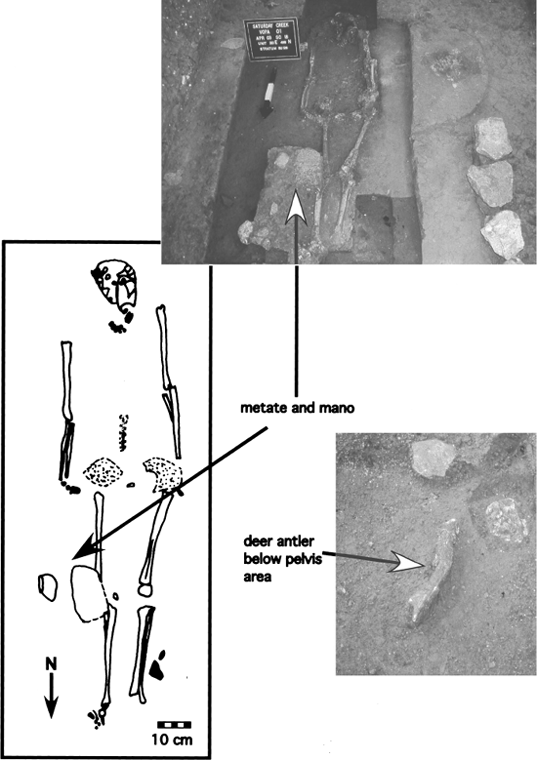

Both of the Early Classic burials at Saturday Creek have grave goods. Burial 5 (Figure 4.9) consists of an extended and supine adult, sex unknown, with filed incisors (Piehl 2002) buried underneath a floor with a metate fragment over the right knee, a mano next to the metate, and a deer antler underneath the pelvis area (Sanchez and Chamberlain 2002). Parts of the skeleton have eroded and are indicated by dark stains (e.g., the thorax, pelvic girdle, and vertebral column). Burial 6 (Figure 4.10) is an extended and prone adult, likely a male, buried with an undecorated poorly fired (friable) plate with little temper inverted over the chest. No burials were found at SC-3 or SC-78, which is not too surprising given our limited excavations. At an elite Barton Ramie structure (BR-123), however, a male adult (Burial 13) was buried under a floor with three vessels and a jade effigy pendant (Willey et al. 1965:90, 550).

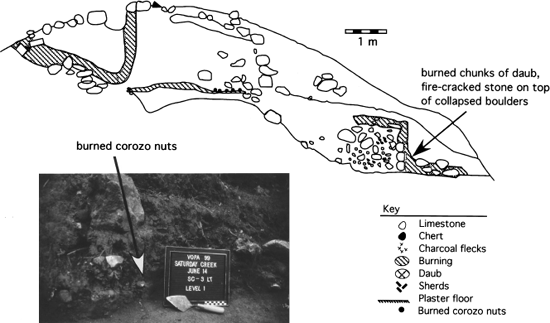

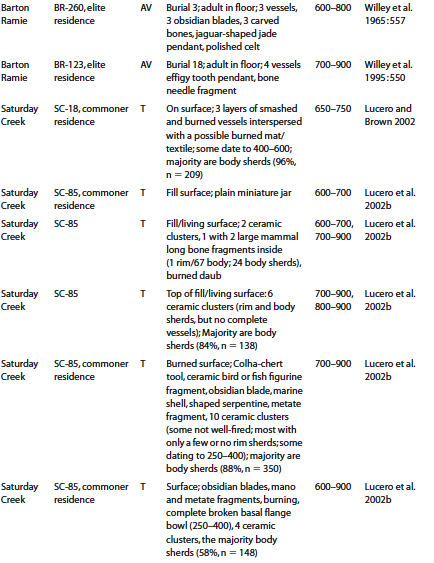

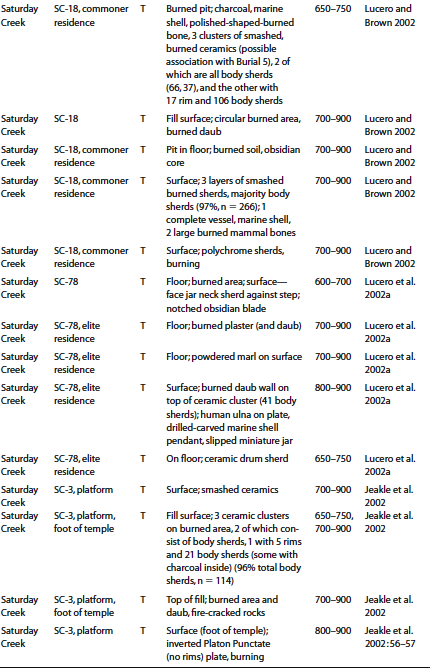

Burned surfaces were recorded for every construction phase at Saturday Creek, including that over burials (e.g., Burial 5, SC-18), indicating a consistent ritual behavior. We also found notched and unnotched obsidian blade fragments and metate pieces on burned surfaces. At SC-3, there were at least two major burning events at the upper temple and its platform. The first consists of a layer of burned corozo palm nuts at the base of the temple, and the second of burned daub, fire-cracked chert and charcoal-flecked soil on top of the partially collapsed (destroyed) platform substructure (Figure 4.11).

Table 4.2. Early Classic ritual deposits

The Late Classic (ca. AD 550–850)

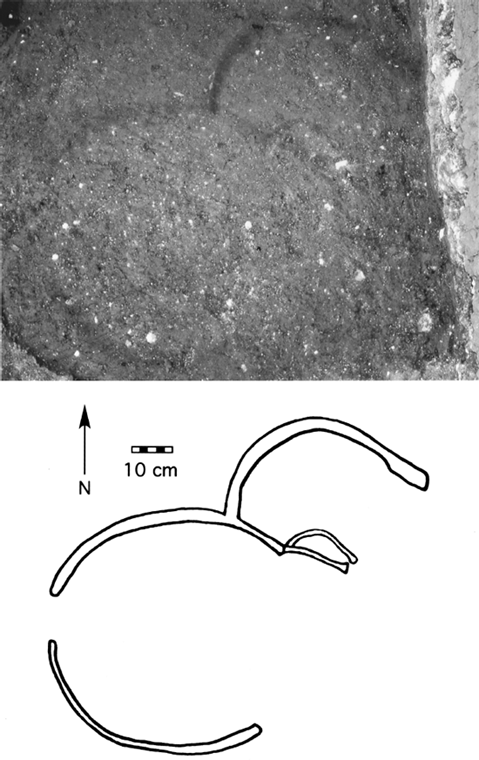

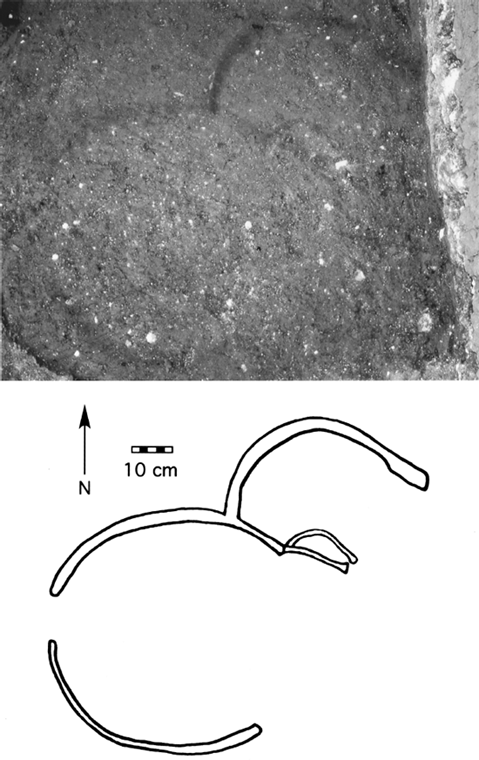

At Saturday Creek, dedication caches were recovered from all four structures (Table 4.3). Those found at the two commoner residences (SC-18, SC-85) are similar to those of earlier periods, but with slightly more diverse items—notched and unnotched obsidian blade fragments, mano and metate fragments, polished stone, bone needles, a miniature jar, polished and shaped bone, drilled marine shell and bone, chert cores, spindle whorls, a polished celt, a bark beater, marine shell, burned and unburned faunal remains, figurine fragments, ceramic discs, ceramic sherd clusters, and a few small jade and hematite inlay or mosaic pieces (Lucero and Brown 2002; Lucero, McGahee, and Corral 2002). A ceramic cluster at SC-85, consisting only of body sherds, may include pieces of heirloom vessels, since their dates range from 300 BC to AD 600. At SC-18 we also found a possible burned wooden post fragment, as well as some kind of design burned onto a surface, which was then buried (Figure 4.12).2 In addition to items found at commoner houses, elite structures (SC-78, SC-3) also yielded quartz pebbles and flakes, complete notched and unnotched obsidian blades and cores, ceramic beads, a deer antler, mica, complete chert and obsidian blades, coral, speleothems, and spider monkey hand bones (Jeakle et al. 2002; Lucero, Graebner, and Pugh 2002). At SC-78 we also recovered stacked vases with bases, but without rims; in the two examples shown in Figure 4.13, three vases are stacked, one inside the other. Of the two ceramic sherd clusters noted at SC-78, 7% (n = 13) are rim sherds from nine different vessels; 93% (n = 164) are body and base sherds. And while we did not recover a ball-court marker from the center of the alley at SC-3, the Maya had dug a pit in which they burned a large quantity of unknown organic material.

Figure 4.9. Burial 5, SC-18.

Figure 4.10. Burial 6, SC-85.

Figure 4.11. East wall profile of SC-3 looter’s trench with burned corozo nuts and burned and destroyed platform.

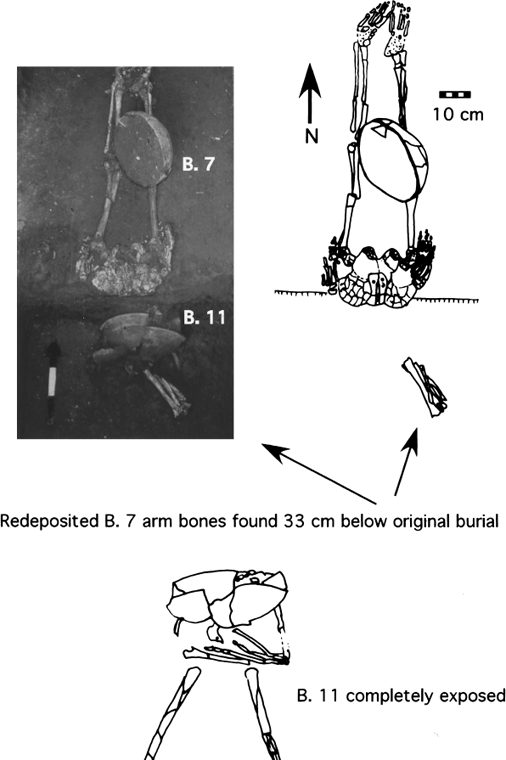

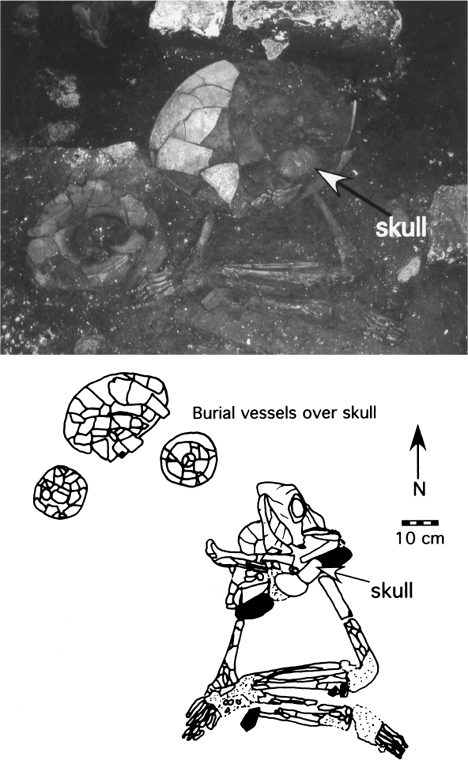

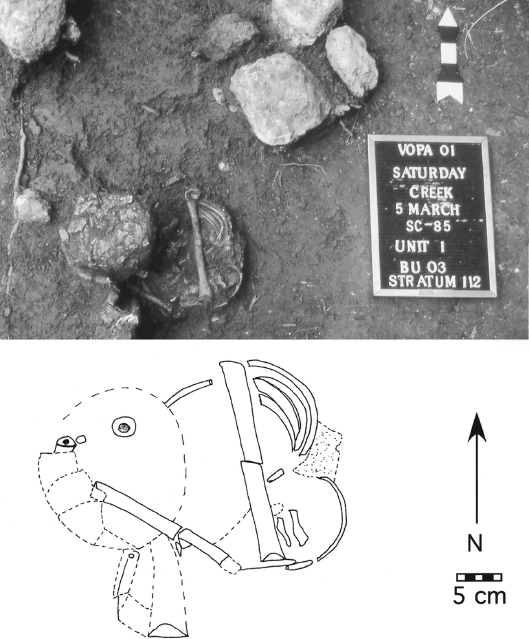

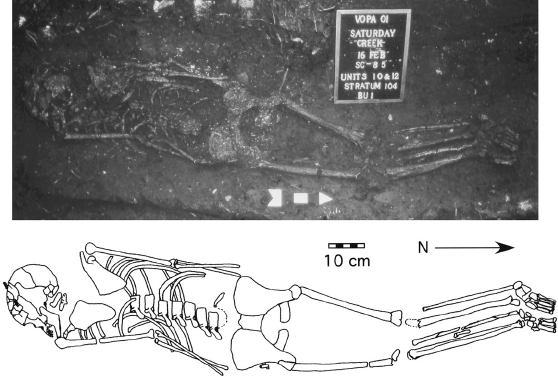

Eight Late Classic burials were recovered from the two smaller residences, four with grave goods (Sanchez and Chamberlain 2002). The three burials at SC-18 all have grave goods, including an adult, likely female (Burial 7), interred with a bowl over the knees, an olla, and freshwater shell disc beads (Figure 4.14). We are not completely sure of the sex because the burial was disturbed during the interment of Burial 11; the Maya removed everything above the pelvis and reinterred only the arm bones near Burial 11. The skull and the rest of the upper body are missing. Two of the three burials are seated, which might indicate high status (McAnany 1998; Sanchez and Piehl 2002). One seated adult, perhaps male (Burial 11), was interred with an inverted dish over the skull (see Figure 4.14), and the other (Burial 2), a young adult (14–20 years, sex unknown), with a large inverted dish over the skull, an olla near the right knee, a hammerstone next to the olla, an inverted plate over the left knee, and marine shell disc beads near the right ankle (Figure 4.15). The sole burial (Burial 8) with grave goods at SC-85, likely of an adult male, includes a dish near the skull, an olla near the chest, a mano fragment, marine shell, two heavily eroded (poorly fired) untempered vessels over the upper legs, and a polished bone near the mandible (Figure 4.16). Burial 3 at SC-85 is a bundle burial of an adolescent (ca. 10–12 years of age) without grave goods (Figure 4.17). The extended and prone adult female at SC-85 (Burial 1) has filed incisors but was not buried with any grave goods (Piehl 2002) (Figure 4.18).

Table 4.3. Late Classic ritual deposits

Due to the limited excavations at Saturday Creek elite structures, we did not find any burials. At Barton Ramie, however, elite burials yielded, in addition to jade beads, at least three jade effigy pendants as well as typically more goods per burial (Willey et al. 1965:90, 549–552). For example, grave goods interred with an adult (Burial 3) at BR-260 (ca. 40 × 30 m with four mounds up to 2 m high) included three vessels, three obsidian blades, three carved bones, a jaguar-shaped jade pendant, and a polished celt (pp. 267–270, 557).

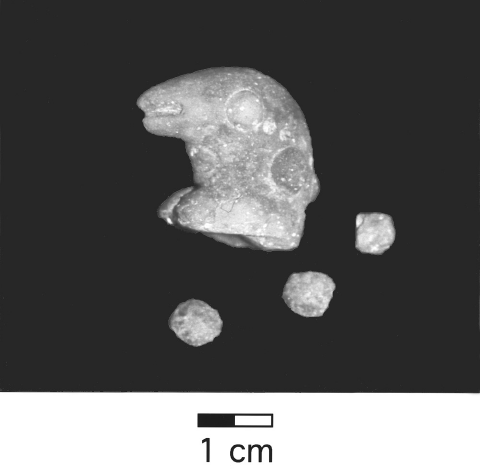

We found termination deposits at all four structures, which are similar to earlier periods. They consist of smashed and burned vessels on surfaces. For example, at SC-18 we recovered three layers of burned and smashed ceramics, mostly body sherds (96%), some of which date to AD 400–600. They had been deposited on top of a textile or mat of some sort, which also had been burned (Figure 4.19). In a later termination event at SC-18, the Maya again burned and smashed three layers of largely rimless ceramic sherds (8 rims or 3%; and 266 body sherds or 97%); we also found a complete but broken bowl in the same deposit, as well as burned bone and marine shells. Similarly, at SC-85, the Maya broke and burned several items, including daub and ceramics; some sherds contain the long bones of a large mammal, likely a deer. They also placed an undecorated miniature jar on a burned surface at ca. AD 600–700. In what appears to be a major termination event, the Maya at SC-85 burned and smashed ceramics (10 different clusters, some not well-fired, with only a few rims) and offered a Colha-chert tool, a ceramic bird or fish figurine fragment, an unnotched obsidian blade, marine shell, shaped serpentine, and a metate fragment (Figures 4.20 and 4.21). Some of the ceramics were possible heirloom vessels, since they dated to as early as ca. AD 250.

Figure 4.12. Burned symbol on a surface at SC-18.

Figure 4.13.Two examples of stacked vases without rims at SC-78.

Figure 4.14. Burial 7 (and Burial 11), SC-18.

Figure 4.15. Burial 2, SC-18. The plate over the left knee has been removed and is not shown in the photograph.

Figure 4.16. Burial 8, SC-85. The upper photograph shows the grave goods found on top of the remains (mano, olla, and two poorly fired vessels).

Figure 4.17. Burial 3, a bundle burial at SC-85. Vandals displaced the skull before we could draw it.

Figure 4.18. Burial 1, SC-85.

Figure 4.19. Termination deposit at SC-18, consisting of three layers of smashed and burned ceramics. The outline of a burned textile or mat is visible.

Figure 4.20. Termination deposit at SC-85, consisting of burned and smashed ceramics and other items. The lower deposit is located east of the upper one and one floor below.

Figure 4.21. A bird or fish figurine fragment at SC-85 that was part of the termination deposit in Figure 4.20.

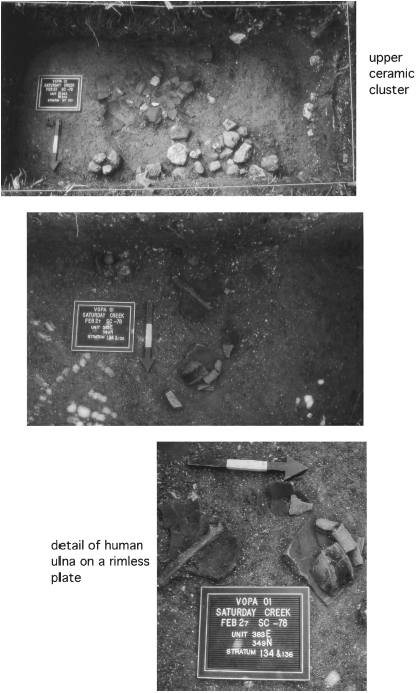

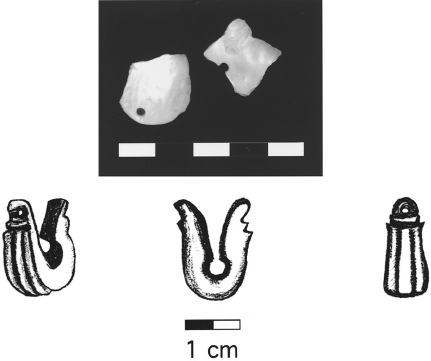

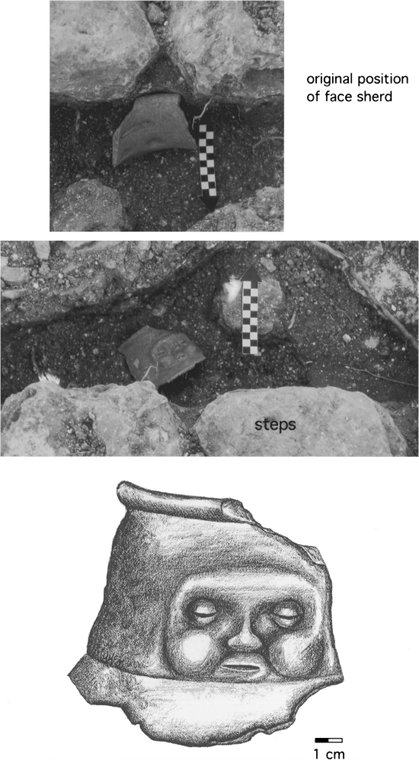

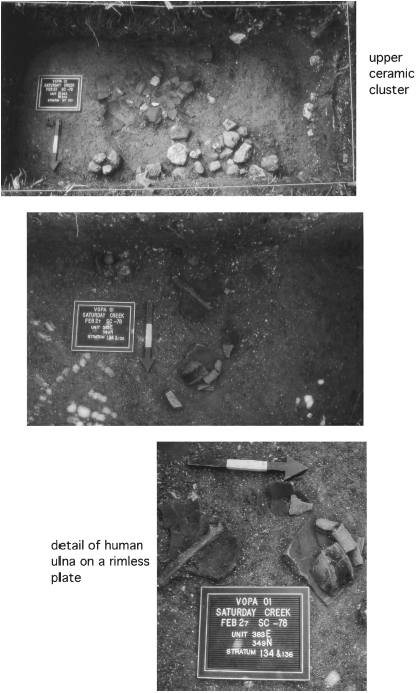

The major difference between commoner and elite termination deposits is the types of vessels smashed. At SC-18 and SC-85, the Maya smashed vessels usually consisting of plain or monochrome slipped bowls, jars and plates, and only a few polychrome sherds, as well as the other items just described. In many cases, however, the smashed ceramic clusters in both elite and commoner contexts largely consist of body sherds with few or no rims. The elite structure and temple yielded, in addition to the above, drum vases, polychrome vessels, molded ceramic pieces, drilled and carved marine shell, powdered marl, burned plaster fragments, and human bone. For example, sometime during the ninth century AD, the Maya at SC-78 burned an entire structure of wattle-and-daub (Figure 4.22). One wall collapsed on a deposit of several burned and smashed decorated vessels (all body sherds), a human ulna placed on top of a large rimless plate, an incised drilled marine shell pendant, and a drilled shell (Figure 4.23). On the north edge of the platform at about AD 600–700, the Maya placed a molded-face jar neck sherd and a notched obsidian blade against the lower platform step near a burned patch of plaster floor (Figure 4.24). In another case, at the foot of the temple at SC-3, an inverted Platon Punctate rimless plate was burned (Figure 4.25; see Figure 4.7 for location) (Jeakle 2002:56–57). This ceramic type was not found anywhere else at Saturday Creek (Conlon and Ehret 2002), and James Gifford et al. (1976:257) note that it was only found in burial contexts at Barton Ramie.

Figure 4.22. Termination deposit at SC-78, consisting of a collapsed burned daub wall (removed) over smashed and burned ceramics and other items, including a human ulna on a rimless plate.

Figure 4.23. Drilled and carved marine shells from a termination deposit at SC-78. 1 cm scale. Drawing of pendant by Gaea McGahee.

The Postclassic (ca. AD 950–1500):The Story Continues

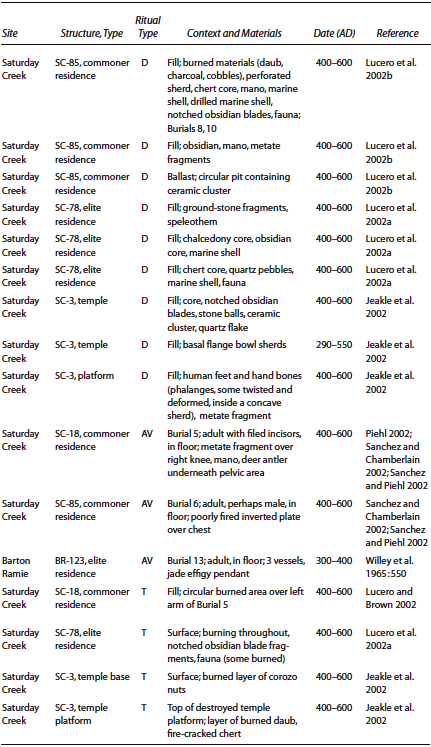

The Maya continued to conduct the same traditional rites in the home long after royals and upper elites ceased conducting theirs. At Saturday Creek, for example, the occupants of one of the small houses (SC-18) expanded the structure south; within fill dating to ca. AD 900–1150, we found a notched obsidian blade (Table 4.4). In another expansion episode in the same area and period, the Maya added more fill and another floor, within which they had placed a polished celt and an unnotched obsidian blade (Lucero and Brown 2002). The other commoner house (SC-85) yielded a Postclassic burial (Burial 10) of a seated individual facing south (Figure 4.26). Time constraints prevented us from completely excavating the burial, but we were able to remove the offering, a complete large red dish (Daylight orange) that the Maya had inverted over the head. We do not know if there were more offerings, since we only exposed the head and shoulders.

Evidence for even later rites comes from the elite compound at Saturday Creek (SC-78). From a fill deposit dating to ca. AD 1150–1500 on the far south of the mound, we recovered a chert blade tool and a shaped and polished multicolored chert flake (Figure 4.27) (Lucero, Graebner, and Pugh 2002). An earlier fill deposit (AD 900–1150) on the north side of the platform mound yielded a piece of jade. In a final example from Saturday Creek, we recovered cores, marine shell, and notched obsidian from a fill deposit of the platform of the temple ball court (SC-3) that dates to ca. AD 900–1150 (Jeakle et al. 2002). Ritual deposits at SC-78 and SC-3 began by at least 300 BC (and very likely earlier) and continued through the Postclassic period, from AD 1150 to 1500.

Figure 4.24. A face jar neck sherd recovered against a step on the north side of SC-78. Drawing by Gaea McGahee.

Figure 4.25. An inverted Platon Punctate rimless plate at the foot of temple SC-3.

Similar patterns were noted at Barton Ramie, especially for burials. BR-1, a mound 2 m in height and 28 m in diameter with 12 occupation phases dating from ca. 100 BC to AD 1200 (Willey et al. 1965:36), yielded an unbroken sequence of ritual events. For example, in the last period of occupation at this house, an infant or child was interred with small beads (Burial 5, p. 545).

At an elite residence, BR-123, Gordon Willey and his crew found thirty-five burials in the thirteen occupation levels (pp. 90, 112), two of which date to the Postclassic (Burials 27 and 33). Neither was buried with grave goods, though one of the burials might be that of a male (pp. 551–552), a pattern that contrasts sharply with earlier burial practices at this mound (see Tables 4.1, 4.2, 4.3).

This pattern differs from BR-144 (1.5 m high, 35 × 35 m). The Maya lived here from ca. AD 0–1200 but only appeared to have two major construction episodes (or perhaps it was quite late in construction and the ceramics from fill contexts came from elsewhere). There are seven burials, all of which date to either ca. AD 800–900 or 900–1200 (pp. 553–554). Only two burials, both of female adults (Burials 1 and 5), have grave goods; the former was buried with a “crescent-shaped object of limestone” (p. 553), and the latter with one vessel.

Table 4.4. Postclassic ritual deposits

While we did not recover obvious Postclassic termination deposits at Saturday Creek, the Maya likely still performed rites at the end of an object’s life. This pattern continues into the Colonial period and into the present, as illustrated in Chapter 3. Also, both Barton Ramie and Saturday Creek have been heavily plowed during the last few decades, which has likely destroyed much evidence for Postclassic termination and other ritual activities. Postclassic rituals are scarce or nonexistent, however, at major centers such as Tikal and Altar de Sacrificios. Their purpose as a place for royal rites decreased in significance when rulers lost power and centers were largely abandoned in the AD 900s.

Figure 4.26. Burial 10, SC-85.

Figure 4.27. A polychrome polished chert flake tool from the south side of SC-78. 1 cm scale.

At Saturday Creek, ritual deposits at commoner residences SC-18 and SC-85 remained basically the same throughout their entire occupation (ca. AD 400–1150). The earliest ritual deposits at the elite structure SC-78 (fill dating to ca. 300–100 BC) are similar (that is, simpler and smaller in scale) to those found at the two solitary commoner mounds (SC-18 and SC-85) throughout both commoner houses’ entire occupation (e.g., marine shell, obsidian blade fragments, and undecorated vessels). This pattern signifies that earlier, commoner ritual deposits at SC-78 are the same as at the two commoner residences and that later, elite buildings have increasingly more diverse goods. As to the significance of notched obsidian blades, they may have served as smaller or commoner versions of eccentrics. The ceramic clusters with only a relatively few rim sherds need explaining; perhaps depositing ceramics without rims was a way to kill vessels in both dedication and termination rituals. In addition, the inclusion of older vessels as termination offerings might indicate the sacrifice of heirloom objects (e.g., R. Joyce 2000).

Evidence for ancestor veneration rites does not noticeably change at commoner residences in over 500 years at Saturday Creek and longer elsewhere. It appears that only select people were buried in houses, particularly adults of both sexes, but mostly males (Sanchez and Piehl 2002; e.g., Haviland 1997). These practices are similar to those seen at small residences at Cuello, Barton Ramie, Altar de Sacrificios, and Tikal (see Chapters 5 and 6). While the burial patterns presented in this chapter are simple, they actually involve complex ritual behaviors. For example, when the residents of SC-18 buried the adult of Burial 5, they first dug a pit, which they filled with flakes and burned and broken pottery (Lucero and Brown 2002). They placed the antler in the center of the pit, after which they put in fill and the deceased individual. They added more fill and then burned and smashed more ceramics. Afterward, they added the mano and metate fragments and more ceramics and placed more fill (dirt). Finally, they burned more items and placed vessels just south of the skull and burned the entire deposit again.

The Maya conducted small-scale rituals inside the home for family members. Some rituals were conducted privately in the elite compound, and some probably involved community members. Its location on a terrace facing a plaza overlooking the majority of Saturday Creek’s inhabitants provided both privacy (it is not visible from below) and an arena for public participation. The more diverse and exotic offerings also distinguished elites at SC-78. Communal or voluntary labor likely built the temple ball court. There is evidence (faunal remains, decorated serving vessels) of feasting near or in the ball-court alley, which elites sponsored for Saturday Creek’s inhabitants. In her analysis of Spanish Lookout (AD 700–900) ceramic forms and faunal remains from the platform and ball-court alley, Julie Jeakle (2002) found noticeable differences between SC-3 assemblages and those from houses, especially the commoner ones. While SC-3 had the lowest ceramic density of the four excavated sites, it yielded a high proportion of large serving vessels. Further, several kinds of bowls were only found at SC-3 and were probably used during feasts. Finally, Jeakle noted that excavated materials from the ball-court alley yielded the highest percentage of large mammal remains (e.g., deer) and turtle carapaces. No faunal remains were recovered from the temple on top, where Maya elites conducted private dedication and termination (and probably ancestor veneration) rituals not visible from the ball-court alley below, at least in the Classic period, when the platform was built up. A similar scenario likely occurred at Barton Ramie.

With plentiful water and land throughout the year, the Maya at Saturday Creek lived a comfortable existence without the worry and bother of outside interference. The lack of obvious water systems and public imagery does not indicate a lesser reliance on gods and ancestors for rain, but rather a lesser need for assistance from other mortals. As members of a larger society, however, they participated in creating and defining Maya social and cultural worldviews. Despite the fact that kings did not emerge at Saturday Creek, elites still conducted traditional rituals at the community level to offset potential conflict in the face of wealth differences and to promote solidarity.

In conclusion, we can better understand how the Maya lived at minor centers through knowledge of their community organization. The only noticeable difference between the general definition of community organization and minor centers is that we do not know about land ownership per se, though it was probably both corporate and private. We must assume that, even if the Maya did not fight as warriors, there was probably some type of conflict (e.g., feuding). And while there is no political iconography or obvious decorative element on monumental architecture, decorations on portable items (e.g., vessels and incised bone) were significant to the Maya and still reflected the critical importance of ancestors and the gods.