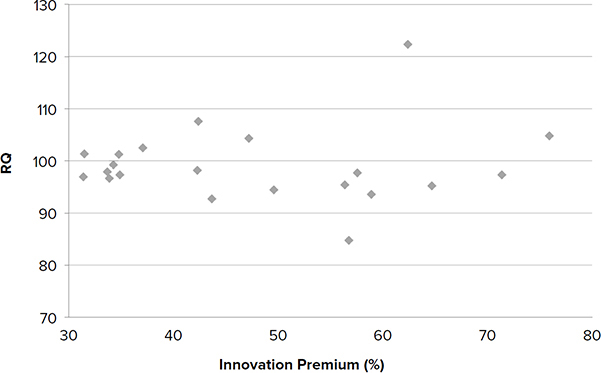

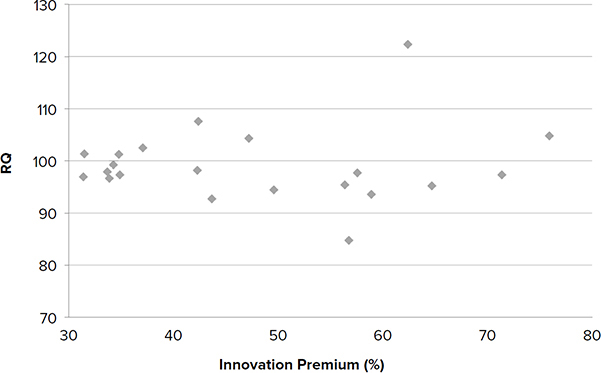

FIGURE 8-1. Holt’s Innovation Premium (IP) is uncorrelated with RQ

We learned in Chapter 4 that RQ allows companies to determine whether to increase or decrease R&D investment, and by how much. It also allows them to quantify the expected impact of the change in R&D on sales, profits, and market value. Given this ammunition, a request to increase the R&D budget in underinvesting firms should be a slam dunk for CEO approval. However, when I’ve proposed this to companies in the past, the typical reaction is, “There is no way we can increase R&D that much—the shareholders won’t allow it.”

Initially I was surprised by this reaction: (1) how could shareholders wield so much power, and (2) why would shareholders prevent companies from doing something in their own best interest? Then I realized it’s because shareholders don’t understand what’s in their best interest—they are subject to the same “flying blind” problem confronting companies.

As a crowning example of that, Warren Buffet, perhaps the most sophisticated investor of all time, has historically eschewed technology stocks, precisely because he didn’t have a way to value them. He once joked to a class that he would fail any student who gave an answer to an exam question asking them to value an Internet company.

How do investors value innovation currently? Trade Radar (one of the most followed authors on Seeking Alpha, a crowdsourced content service for financial markets that Kiplinger’s named as Best Investment Informant) identifies seven factors to consider with tech stocks.1 Of these, all but one are factors to consider for any stock: (1) year-over-year comparisons versus sequential quarterly results, (2) gross margin, (3) average selling price (ASP), (4) debt, (5) customer base, (6) license (subscription) revenue, and (7) R&D. The only factor specific to tech was R&D. And here the only advice was to beware when R&D expenses appear to be in steady decline. “This could be a sign that they are milking current product lines while ignoring the future.” Trade Radar is certainly right that R&D decline is something you want to investigate (though as we saw in Chapter 4, many public companies do need to decrease their R&D). However, watching R&D decline doesn’t help you value innovation; it merely tracks the input to innovation. So these seven factors won’t solve Warren Buffet’s problem.

A more sophisticated approach to valuing innovation is Holt’s Innovation Premium (IP). Holt is a division of Credit Suisse that develops tools for evaluating investments. Its IP measure is the basis for Forbes’s annual innovation ranking. IP is defined as “the difference between market capitalization and a net present value of cash flows from existing businesses. [This] is the bonus given by equity investors on the educated hunch that the company will continue to come up with profitable new growth.”2 In this sense, IP is similar to an academic measure called Tobin’s Q, developed by Nobel economist James Tobin, that compares the market value of the company to its total assets. While IP goes beyond Trade Radar’s seven factors, it is not fundamental analysis that allows you to value innovation. It is almost the opposite—it reports back to investors how much value they have already attached to a company’s innovation. Accordingly, IP does not correlate with subsequent returns, as noted on the Forbes website: “(IP) is also not a statement about expected excess returns—in fact . . . we went back through the data for the past 20 years and find that there is . . . no correlation of IP with subsequent return to investors.”

Not only is IP uncorrelated with future returns, it is also uncorrelated with RQ. Figure 8-1 plots the RQ and IP values for companies in the Forbes 100 (the public companies with the 100 highest IP values).3 Each diamond in the figure represents a company. To locate a company’s IP, merely drop a vertical line from the diamond to the x-axis; to locate its corresponding RQ, draw a horizontal line to the y-axis. You can see from the figure that more than half of the Forbes 100 companies have below-average values of RQ (the RQ scale mimics the IQ scale, so the average is 100). Thus IP appears to be capturing companies whose growth is coming from something other than R&D. Accordingly that growth may not be sustainable.

FIGURE 8-1. Holt’s Innovation Premium (IP) is uncorrelated with RQ

The approach to valuing R&D that best conforms to fundamental analysis comes from Aswath Damodaran, a finance professor at NYU.4 Professor Damodaran notes that the biggest problem with treating R&D as an operating expense rather than as a capital expense (as required by the Financial Accounting and Standards Board [FASB])5 is that investors lose the most potent tool for both estimating growth and checking for internal consistency. This is because the resulting measures of company reinvestment rate and return on capital are meaningless when the biggest asset is off the books.

Damodaran therefore offers a valuation approach that attempts to capitalize R&D. This approach requires (1) estimating the amortizable life of R&D, (2) collecting, then amortizing, all years of R&D expense across the years of life, (3) adjusting each year’s operating earnings to add back that year’s R&D and subtract the amortized R&D for all the other years, (4) adding the unamortized portion of R&D for all years to both the book values of both equity and capital, and (5) using those book values to determine adjusted values for return on equity and return on capital.

While this approach certainly solves the problem of uncapitalized R&D, it implicitly treats R&D and physical capital as equivalent. While it would be fairly straightforward to adjust the analysis for R&D and capital to have separate returns, the role of R&D is to increase the productivity of physical capital over time. Thus R&D should be an accelerator of the returns to physical capital.

We see that investors, like companies, have lacked the means to value R&D. How does that affect their behavior? We saw that when companies lack measures of R&D effectiveness, their R&D investment is suboptimal, and their RQ tends to decline over time. Investors don’t have those problems, but they have an equivalent set of problems that hurt them as well as the companies they invest in. The first problem is that investors have to rely on faith that R&D should generate growth. Faith is hard to maintain, particularly when the alternative is to cut R&D. Cutting R&D immediately increases profits—it reduces expenses, with no detrimental impact on current revenues.

This problem of faith is captured in the sentiments of Shannon O’Callaghan, an analyst at Nomura Securities International, who covers 3M:

3M clearly has more of a long-term focus [than many publicly traded companies] and less desire to please investors every quarter. . . . That’s admirable up to a point, but when do you acknowledge the expectations of the equity investors and finally give them what they’ve been looking for?6

Note that O’Callaghan holds these sentiments even though 3M has kept operating margins above 20 percent and has increased its dividend in each of the past 55 years.

More powerful than analysts who pressure companies for current profits are activist investors such as Nelson Peltz of Trian Fund. Rather than merely discouraging R&D investment, Peltz pressured DuPont to split into two divisions, arguing that the promise of combining chemical R&D and biological R&D wasn’t bearing fruit. Ultimately Peltz prevailed, though through a circuitous route of DuPont first merging with Dow, then splitting the merged entity into three companies. In anticipation of the merger, DuPont dismissed 50 percent of its scientists at the central research lab and cut its 2016 R&D budget roughly 10 percent relative to the $1.9 billion it invested in 2015.

Without knowing DuPont’s RQ, it was almost impossible for then CEO Ellen Kullman to fend off Peltz. There was no way to quantify the returns to DuPont’s R&D, nor a way to demonstrate whether the company was overinvesting or underinvesting. The best defense the company could raise appeared to be a 2014 report that estimated that DuPont’s combined know-how in chemical and biological engineering generated about $400 million in annual revenues (approximately 1 percent of total revenues). That analysis in itself seemed to support Peltz’s case, since DuPont was investing approximately 6 percent of revenues in R&D each year. Thus a stronger defense would be to aggregate the R&D for all projects and show the increase in revenues expected from each of them. This is precisely what RQ does without having to get into the weeds of itemizing all the projects and matching them to revenues.

Because we have RQ, we can now rationally analyze whether Nelson Peltz was right about DuPont overinvesting in R&D. The unfortunate answer (because it’s always tragic to see a central lab dissolve) appears to be yes. Given DuPont’s RQ, a 10 percent increase in R&D ($200 million) only generates a 1 percent increase in gross margin ($156 million). Thus DuPont would increase profits by decreasing its R&D.

Activist investors are relatively rare, so it’s useful to think about another important investor group that wields significant power over companies, institutional investors. In general, institutional investors are assumed to have a longer-term perspective than other investors. Focusing on the long term rather than current period profits should favor R&D, but what does the record show? A recent study by Trey Cummings at Washington University shows that companies with institutional investors have higher RQ and invest more in R&D. This leads naturally to the chicken-and-egg question of whether institutional investors make companies more innovative (increase their RQ) or are merely better at identifying innovative companies (those with higher RQ). Trey’s results indicate that companies become more innovative when the number of shares held by institutional investors increases. This almost seems implausible since institutional investors don’t manage any of the R&D. However, what they do control is CEO compensation, and it appears that when institutional ownership increases, more of the CEO’s compensation is tied to stock price. When that’s true, CEOs themselves develop a longer-term perspective, increase R&D spending, and improve RQ.7 Of course, few companies are lucky enough to attract institutional investors. What the other companies need is a way to fend off investor pressure to cut R&D to increase current profits.

In principle, companies should be able to make shareholders more patient merely by communicating how the increased investment in R&D will increase revenues, profits, and market value. Ultimately that will be true, but because RQ is new, shareholders need to develop confidence in these forecasts.

The best means to instill confidence is to present investors with short-run opportunities to profit from using RQ—trading strategies that allow sophisticated investors to benefit from the fact that only a few other investors know about RQ.

One simple but powerful strategy is merely to invest in an RQ50 Index fund. The RQ50 Index is the set of companies with the highest RQ in the prior fiscal year. While the RQ measure didn’t exist until recently, the data to compute RQ go back to 1965, so I’ve constructed the index for every year from 1973 forward. I computed the RQs for all public companies conducting R&D in each year, ranked them in descending order of RQ, then identified the top 50 companies in each year. I then synthetically “invested” $20 in each RQ50 stock from fiscal year 1972 on January 1, 1973. On December 31, 1973, I “sold” all the stocks. I took the proceeds from that sale, divided that by 50, then invested that amount in each of the new RQ50 stocks on January 1, 1974. This is called an equal-weighted, annually rebalanced portfolio. Incidentally, about two-thirds of the stocks remained in the portfolio from one year to the next—reflecting the fact that R&D capability is fairly durable.

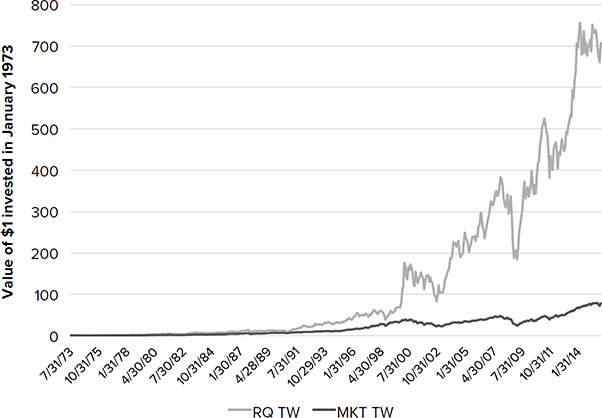

When I repeated this process annually through December 2015, I obtained the returns seen in Figure 8-2. What you can see is that the RQ50 Index fund outperformed the market by a factor of nine! In other words, if you had invested $1,000 in the market index on January 1, 1973, 43 years later (December 31, 2015) you would have $78,000. If, however, you had invested the same $1,000 in the RQ50 Index on January 1, 1973, you would have $708,000 on December 31, 2015!8

FIGURE 8-2. $1,000 invested in the RQ50 portfolio in 1973 would be worth $708,000 in December 2015 (versus $78,000 for the market portfolio)

Why does the RQ50 Index perform so much better than the market? First, these stocks fly under investors’ radar precisely because there hasn’t been a reliable way to value innovation before. Ultimately (two to three years later) that R&D capability shows up in higher profits, which the market does know how to value. So the higher returns of the RQ50 Index are coming from investing in innovative companies before the market understands how their innovation will impact future profits.

The RQ50 Index is compelling evidence for both companies and investors that RQ delivers on its promise to translate R&D into market value. Next I’ll show you what that translation looks like. Thus while the RQ50 should attract investor attention, the ability for investors to do fundamental analysis for all R&D stocks is what is ultimately needed for them to fully support companies’ R&D investment. I discuss that next.

We learned in Chapter 1 that RQ determines how revenue and profit are affected by a company’s R&D. A logical next step is to see how market value is affected by RQ. If financial markets are efficient, then the market value of a company should be the net present value of its future profit stream. Thus, if I forecast all future profits, discount them by the appropriate cost of capital each year, and add them together, I should obtain the company’s market value.

This sounds easy in principle but can be complex to compute. Fortunately, we can make a few assumptions to clean up much of the complexity. The first assumption is that profits grow at a constant rate, g, forever. In fact, in the case of RQ, this isn’t really an assumption—it’s a result derived from a theory of growth discussed in Chapter 4. While the theory tells us that higher RQ translates into higher growth, it doesn’t tell us by how much. We had to determine that from the data. A colleague and I found that a 10 percent increase in R&D contribution increases five-year growth 0.65 percent.9

The second assumption is that the cost of capital, d, remains the same forever. With those assumptions, we have a handy formula, the Gordon Growth Model (GGM), to make life simple. GGM says the present value (in this case market value), V, of a dividend stream (in this case profit stream) equals the annual income, π, divided by the cost of capital, d, minus the growth rate of profits, g:

V = π / (d − g)

This simple relationship explains where a stock’s price to earnings ratio (P/E) comes from. It’s merely 1/(d − g).

The next thing we need is profits. We know that profits equal revenues minus costs. In Chapter 10, I will show you the full profit equation for firms conducting R&D, but for now, I’m going to simplify that equation:

π = R&DRQ × (Revenue contributions from non-R&D inputs) − costs

Substituting the profit equation for π in the value equation yields the following equation for market value as a function of R&D and RQ:

MV = (R&DRQ × (Revenue contributions from non-R&D inputs)-costs)) / (d-g)

What you see from this equation is that any time we increase RQ (keeping R&D constant), we increase the company’s market value. The other thing you can see from the equation is that the contribution of R&D to revenues, profits, and market value combines two factors: the level of R&D and the productivity of that R&D (RQ) in a particular way: R&DRQ. I call this combination the R&D contribution. The R&D contribution amplifies the contribution from the other inputs.

You can of course refine this equation in additional ways. However, given the annual spread in minimum and maximum stock prices of even very stable companies, it’s a little like using calipers to measure, and then cutting with a saw. The more interesting question is whether the market behaves as if RQ affects companies’ stock price. The answer is yes. My colleagues Mike Cooper and Wenhao Yang and I compared companies’ monthly stock market returns to their RQ, controlling for all other factors known to affect returns. We found that not only was RQ a significant predictor of returns, it was the most significant predictor. The next closest predictor was momentum.10

Understanding the link between RQ and market value is the first step in making RQ interesting to investors—they can now value R&D in fundamental analysis. In fact, I thought as soon as RQ was available, it would rapidly diffuse throughout the investor community. I naively assumed that all investors preferred to do value investing, and therefore would jump on the opportunity to finally be able to value R&D.

It then occurred to me what investors must really care about is whether there is opportunity to trade on that knowledge. So far we’ve seen there is at least a trillion dollars in market value to be made if companies optimize their R&D budgets. However, only activist investors like Nelson Peltz are likely to get companies to optimize their R&D investment. An easier strategy, and the only strategy for most investors, is to identify companies that are undervalued given their RQ. This is precisely the strategy Warren Buffet uses for value investing in companies other than ones that do R&D. But how can you identify such companies? We saw one very simple way to profit from companies whose R&D was undervalued was to invest in the RQ50 Index.

When I saw that opportunity, I wanted to invest in the index myself! The problem was all my funds were tied up in a 401(k) at Vanguard. I approached our dean, showed him the returns to the RQ50 Index, and proposed that we create an “Olin RQ50 Index Fund.” He was intrigued by the idea, so he put me in touch with Kim Walker, Washington University’s chief investment officer. She too was intrigued, so she put me in touch with the head of product development at Vanguard. I described for him the foundations of RQ, and showed him the performance of the RQ50 Index. He first explained that the RQ50 is not an index. An index is intended to be a representative sample of companies in a particular domain. I asked, why would you want to invest in a representative sample when you could instead invest in exemplars? He then explained that even removing the name “index” from the fund wouldn’t solve the problem, because Vanguard isn’t interested in building funds around new theories. They let other investment companies experiment with new theories, and then pursue the ones left standing.

So the RQ50 Index is the simplest way to profit from investing in undervalued R&D companies. A second way that involves more work is to identify companies whose P/E ratio is below what it should be given their RQ. I showed earlier that P/E is merely shorthand for a company’s expected growth and cost of capital. Since R&D investment is the primary driver of growth, then a company’s price to earnings ratio (P/E) ought to track its R&D contribution. If the company’s R&D contribution is rising (either because of increased R&D or increasing RQ), but the P/E is failing to track that, then the company may be undervalued (a buying opportunity). Conversely, if the company’s R&D contribution is falling and the P/E is failing to track that, then the company may be overvalued (a selling opportunity).

In principle, the hardest step in determining if a company is undervalued using this approach is calculating its RQ. I’ve made that easy for investors. Access to a database of company RQs is available for free to all retail trading sites. Thus, RQ can appear on each stock page along with the standard metrics such as Market Capitalization, forward P/E, and Beta. If your preferred site doesn’t provide RQ, recommend to it that it does.

Let’s apply this approach to identifying opportunity using some case examples. Looking first at undervaluation, Merck’s P/E tracked its R&D contribution pretty closely through 2008 (Figure 8-3a). Thereafter its R&D contribution increased, while its P/E failed to follow. Thus Merck appears to have been undervalued from 2008 through 2012. Indeed, the stock price seems to reflect that. Merck’s stock price on January 1, 2009, was $26.75; its price four years later (January 1, 2013) was $44.20 (an annual return of 13.3 percent).

McKesson also appears to have been undervalued over roughly the same period (Figure 8-3b), and its returns were even more impressive over the same period. Its stock prices on the same dates were $44.20 and $105.23, respectively. Thus, its annual return was 24.2 percent. Note that several other factors affect these companies’ stock prices over the period, such as market conditions and interest rates. This comparison of R&D contribution to P/E is merely one indicator a company is potentially undervalued, and therefore may warrant deeper investigation.

Merck and McKesson both appear to be undervalued via this comparison, but there is also trading opportunity for companies that are overvalued. This appears to have been the case for Motorola (Figure 8-4a) and ConocoPhillips (Figure 8-4b). In 2007 both companies’ R&D contributions suffered a steep decline from the financial shock that never enjoyed the recovery of Merck and McKesson. While their R&D contributions remained low or fell further in 2008, their P/E didn’t reflect that until two to three years later. Accordingly, both companies appear to have been overvalued—suggesting a signal to sell before the market recognized that. Indeed, Motorola’s stock price on January 1, 2007, was $80.24, but fell to $17.91 on January 1, 2009—a 78 percent loss in value. Similarly, ConocoPhillips’ stock price on January 1, 2007, was $50.63, but fell to $28.46 on January 1, 2009—a 44 percent loss in value.

A third way to exploit opportunities to trade on companies’ RQ is to act on changes to either their R&D spending or their RQ. This requires tracking a particular set of stocks, and checking them manually or setting up an alert system on a database that triggers your attention when either RQ or R&D is changing beyond some bounds.

Once you’ve identified such companies, the next step is to calculate the impact of those changes. To do that, you need to isolate the “non-R&D market value” (MV−R) of the company. This is the market value of the company stripped of its R&D. To obtain that value, you need the company’s market value in year t, before the change (MVt), as well as its R&D and RQ before the change. The “non-R&D market value” (MV−R) is merely the company’s market value prior to the change (MVt), divided by its R&D contribution prior to the change (R&DRQ):11

MV−R = MVt / (R&DRQ)t

The next step is to compute the new R&D contribution (R&DRQ)t+1 by changing either R&D, RQ, or both. Once you’ve done that, the expected market value after the change, (MVt+1), is simply the “non-R&D market value” (MV−R) times the new R&D contribution (R&DRQ)t+1:

E(MV)t+1 = MV−R × (R&DRQ)t+1

To make that a little clearer, let’s apply this analysis to Motorola. In 2006, Motorola’s market value (MV2006) was $49.29 billion. Its R&D was $3.68 billion, and its “raw RQ” was 0.264. So Motorola’s R&D contribution was 8.74 (= 3,6800.264). We obtain its “non-R&D market value” (MV−R)t by dividing its market value by its R&D contribution. This value is $5.64 billion (= $49.29 billion/8.74).

In 2007, Motorola underwent two changes. It increased its R&D to $4.14 billion, but its “raw RQ” decreased to 0.156, so its new R&D contribution was 3.67 (= 4,1400.156). When we multiply Motorola’s new R&D contribution (3.67) by the “non-R&D market value” (MV−R) computed using 2006 data ($5.64 billion), we obtain Motorola’s expected market value for 2007 of $20.7 billion (a 58 percent reduction):

E(MV)2007 = MV−R × (R&DRQ)2007 = $5.64 billion × 3.67 = $20.7 billion

Thus knowing Motorola’s R&D and RQ would have allowed investors to anticipate a decrease in the company’s stock price, even though the company was increasing its R&D.

A final strategy to trade on a company’s RQ is to invest in anticipation of its RQ changing. This requires both knowing that a company’s R&D strategy has changed and recognizing how that strategy change will affect its RQ. We are still pretty far from being able to do that. Fortunately, for the time being, there is plenty of opportunity to pursue the undervalued/overvalued investment strategy, and the strategy of responding to observed changes in R&D or RQ.

We’ve gone pretty far down the path of helping investors trade on opportunities that exploit the fact that most other investors don’t know how to value R&D. You can now exploit those opportunities for your personal investing. That wasn’t our primary goal for this chapter, however. Our primary goal was to alleviate the current problem companies face from investors—unwarranted pressure to reduce R&D.

The role of the trading strategies was to demonstrate that investors ultimately should value R&D correctly, because those that do can make money in the short run by trading against those who don’t. Ultimately, this will drive the don’ts from the market. When that happens, companies should be able to pursue R&D strategies they’re currently dissuaded from. In the meantime, you may want to court institutional investors, since they already seem to value R&D.

The first way RQ helps companies is by telling them how much they should invest in R&D. However, if investors don’t know how the increased investment translates to market value, companies may not have the discretion to expend additional funds. Fortunately RQ defines the relationship between companies’ R&D and their market value. While I showed that relationship, I also showed that because most investors don’t know companies’ RQs, there is trading opportunity for those who do! Ultimately, of course, all investors should know companies’ RQs. So the bad news is the trading opportunity will go away, but the good news is once that happens, companies will no longer be under pressure to cut R&D expenditure (unless of course their R&D exceeds the optimum).

Given the influence investors exert over companies, they too play a critical role in restoring economic growth. Even though they don’t invest in R&D directly, they influence the behavior of companies that do. The proof that investors affect behavior is that R&D spending and RQ increase when companies have more sophisticated investors (institutional investors).