Musée Rodin

Small-Scale Models of Major Works

Final Years: Looking Back, Looking Forward

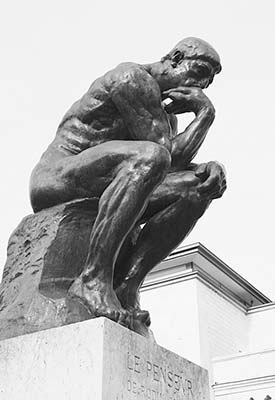

Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) was a modern Michelangelo, sculpting human figures on an epic scale, revealing through their bodies his deepest thoughts and feelings. Like many of Michelangelo’s unfinished works, Rodin’s statues rise from the raw stone around them, driven by the life force. With missing limbs and scarred skin, these are prefab classics, making ugliness noble. Rodin’s people are always moving restlessly. Even the famous Thinker is moving; while he’s plopped down solidly, his mind is a million miles away.

The museum presents a full range of Rodin’s work, housed in a historic mansion and its gardens where the artist once lived and worked.

(See “Rodin Museum Overview” map, here.)

Cost: €10, free for those under 18, free on the first Sun of the month Oct-March, €4 for gardens only, €18 combo-ticket with Orsay Museum, both museum and gardens covered by Museum Pass. Your ticket or Museum Pass also covers any special exhibits.

If you have a Museum Pass or a ticket purchased online (www.musee-rodin.fr, €2 booking fee), you can bypass both the line for buying tickets and the one for entering the museum building itself (lines are rarely a problem).

Hours: Tue-Sun 10:00-17:45, closed Mon; gardens close at 18:00, Oct-March at 17:00.

Information: Tel. 01 44 18 61 10, www.musee-rodin.fr.

When to Go: The museum is busiest on weekends and on rainy days (when the building is packed and the gardens are unpleasant). Note that if you are tight on time and money—and plan to go to the Orsay—there are several good statues by Rodin there.

Getting There: It’s at 77 Rue de Varenne, near the Army Museum and Napoleon’s Tomb (Mo: Varenne). Bus #69 stops two blocks away at the intersection of Rue Grenelle and Rue Bellechasse. Bus #87 also stops nearby, a long block south on Rue de Babylone.

Tours: A €6 audioguide covers the museum and gardens and is really helpful to fully appreciate the art.

Length of This Tour: Allow one hour.

Baggage Check: Even a fairly small bag must be checked, unless you tuck it under your arm like a purse.

Cuisine Art: A peaceful $ self-service cafeteria is in the gardens behind the museum. Picnics are not allowed in the gardens. For better options, you’ll find many recommended cafés and restaurants in the Rue Cler area (a 15-minute walk; see here).

(See “Rodin Museum Overview” map, here.)

• Enter and buy tickets in the modern entrance hall. There’s a bookstore, a gallery for temporary exhibits, and WCs. Pick up the museum map (and audioguide, if interested).

Exit the ticket hall, walk across the courtyard of the gardens, and enter the mansion (where you’ll check your bag). You’ll follow a one-way route over two floors, circling each clockwise, ground floor first and then upstairs. Now enter Room 1, which generally displays...

Rodin’s early works match the belle époque style of the time—noble busts of bourgeois citizens, pretty portraits of their daughters, and classical themes. Born of working-class roots, Rodin taught himself art by sketching statues at the Louvre and then sculpting copies.

The Man with the Broken Nose (L’Homme au Nez Cassé, 1865)—a deliberately ugly work—was 23-year-old Rodin’s first break from the norm. He meticulously sculpted this deformed man (one of the few models the struggling sculptor could afford), but then the clay statue froze in his unheated studio, and the back of the head fell off. Rodin loved it! Art critics hated it. Rodin persevered. (Note: The museum rotates the display of two different versions—the broken-headed one and a repaired version that Rodin made later and critics accepted.)

You may also see portraits of Rodin’s future wife, Rose Beuret, the woman who would suffer with him through obscurity and celebrity.

To feed his family, Rodin cranked out small-scale works—portraits, ornamental vases, nymphs, and knickknacks to decorate buildings—with his boss’ name on them (the more established sculptor Albert Carrier-Belleuse). Still, the series of mother-and-childs he was hired to do (perhaps depicting Rose and baby Auguste?) allowed him to experiment on a small scale with the intertwined twosomes he’d perfect later in his career.

Rodin’s work brought in enough money for him to visit Italy, where he was inspired by the boldness, monumental scale, restless figures, and “unfinished” look of Michelangelo’s sculptures. Rapidly approaching middle age, Rodin was ready to rock.

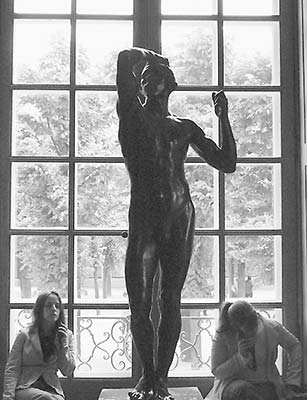

Rodin moved to Brussels, where his first major work, The Age of Bronze (L’âge d’Airain, 1877), brought controversy and the fame that surrounds it. This nude youth, perhaps inspired by Michelangelo’s Dying Slave (in the Louvre—see here), awakens to a new world. It was so lifelike that Rodin was accused of not sculpting it himself but simply casting it directly from a live body. The boy’s raised left arm looks like it should be leaning on a spear, but it’s just that missing element that makes the pose more tenuous and interesting.

The art establishment still snubbed Rodin as an outsider, and no wonder. Saint John the Baptist (1880)—though now acknowledged as a classic—was savaged by the critics for its awkward, flat-footed pose. His ultra-intense The Call of Arms (La Défense, 1912-1918) screams, “Off with their heads!” at the top of her lungs. Rodin loved twisted poses, fragmented figures, and weird juxtapositions. He was forging a style that was unique. He was a slave to his muses, and some of them inspired monsters.

Little by little, Rodin gathered an entourage around him of like-minded souls: wealthy patrons, fellow artists who understood his vision, and students who adored him...including one he’d later become involved with, Camille Claudel.

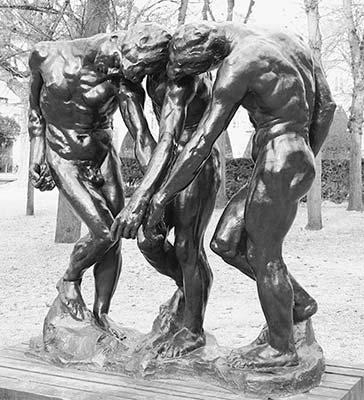

Rodin and his stable of talented artists began cranking out works that have become classics. As you’ll see throughout the museum, Rodin often started with small-scale versions of works that were later executed on a grand scale. (This process is explained in the sidebars.) He tinkered with The Thinker for years before creating the massive bronze version in the gardens (which we’ll see later). The Three Shades (Les Trois Ombres, before 1886)—whose heads and hands join in the solidarity of the damned—would appear later on his epic Gates of Hell (which we’ll also see in the gardens).

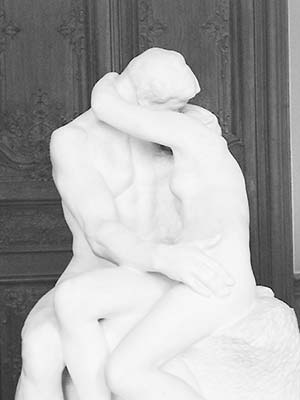

In The Kiss (Le Baiser, 1888-1889), a passionate woman twines around a solid man for their first, spontaneous kiss. Looking at their bodies, we can almost read the thoughts, words, and movements that led up to this meeting of lips. The Kiss was the first Rodin work the public loved. Rodin came to despise it, thinking it simple and sentimental.

The Hand of God (La Main de Dieu, 1896) shapes Adam and Eve from the mud of the earth to which they will return. Rodin himself worked in “mud,” using his hands to model clay figures, which were then reproduced in marble or bronze, usually by his assistants. Inspect this masterpiece from every angle. Rodin first worked on the front view, then checked the back and side profiles, then filled in the in-between.

Rodin excelled in creating ensembles. As he worked on small-scale studies for the grim execution scene known as The Burghers of Calais (small white plaster model in glass case is on display here, the full-sized bronze version stands in the gardens), he needed not only to capture each man’s individual expression but also how his body language conversed with the other members of the group.

What did Rodin think of women? There are many different images from which you can draw your own conclusions.

He loved sculpting women, either alone or as part of an intertwined couple. Danaïd (1889) buries her head in the marble over her meaningless fate. Eve (1881) buries her head in shame, hiding her nakedness. But she can’t hide the consequences—she’s pregnant.

As Rodin became famous, wealthy, and respected, society ladies all wanted him to do their portraits. You may see a sculpture of his last mistress (La Duchesse de Choiseul), an American who lived with him here in this mansion. Rodin purposely left in the metal base points (used in the sculpting process), placing them suggestively.

Throughout the museum are studies of the female body in its different forms—crouching, soaring, dying, open, closed, wrinkled, intertwined.

• Continue your visit upstairs.

Rodin started hanging out with Paris’ intellectuals, artists, and glitterati as one of their own. You may see statues and portrait busts of celebrities he knew personally. Remember, Rodin lived and worked in this mansion, renting rooms alongside Henri Matisse, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke (Rodin’s secretary), and the dancer Isadora Duncan.

Rodin was especially fascinated with trying to capture the perfect portraits of his two famous writer friends, Victor Hugo and the controversial French novelist Honoré de Balzac. With Balzac, Rodin’s feverish attempts ranged from a pot-bellied Bacchus to a headless nude cradling an erection (the display changes). In a moment of inspiration, Rodin threw a plaster-soaked robe over a nude form and watched it dry. This became the inspiration for the definitive version—proud and turning his nose up at his critics. (This version is displayed in the gardens, near The Thinker; other casts stand in the Orsay Museum and on a street median in Montparnasse.) When the Balzac statue was unveiled, the crowd booed, a fitting tribute to both the defiant novelist and the bold man who sculpted him.

You’ll find a few paintings by fellow artists Rodin either knew or admired, such as Vincent van Gogh, Claude Monet, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Rodin enjoyed discussions with Monet and other artists and incorporated their ideas into his work. Rodin is often considered an Impressionist because he captured spontaneous “impressions” of figures and created rough surfaces that catch reflected light.

• In the center room on the back side enjoy nice views overlooking the gardens. On the back wall is a large painting of Rodin in his studio. The next room (#16) is dedicated to...

You’ll find several works by Camille Claudel, mostly in the style of her master. The 44-year-old Rodin, inspired by 18-year-old Camille’s beauty and spirit, took her as his pupil, muse, colleague, and lover, and often used her as a model. (See several versions of her head.) We can follow the arc of their relationship in the exhibits.

As his student, “Mademoiselle C” learned from Rodin, doing portrait busts in his lumpy, molded-clay style. Her bronze bust of Rodin shows the steely-eyed sculptor with strong frontal and side profiles, barely emerging from the materials they both worked with.

Soon they were lovers. The Waltz (La Valse) captures the spinning exuberance the two must have felt as they embarked together on a new life. The couple twirls in a delicate balance.

But Rodin was devoted as well to his lifelong companion, Rose. Claudel’s Maturity (L’Age Mûr, 1895-1907, also in Orsay Museum) shows the breakup. A young woman on her knees begs the man not to leave her, as he’s reluctantly led away by an older woman. The statue may literally depict a scene from real life, in which a naked, fragile Claudel begged Rodin not to return to his wife. In the larger sense, it may also be a metaphor for the cruel passage of time, as Youth tries to save Maturity from the clutches of Old Age.

Rodin did leave Claudel. Talented in her own right but tormented by grief and jealousy, she became increasingly unstable and spent her final years in an institution. Claudel’s The Wave (La Vague, 1900), carved in green onyx in a very un-Rodin style, shows tiny, helpless women huddling together as a tsunami is about to engulf them.

• Finally, step into the corner room.

By the end of Rodin’s long and productive life, he had become as famous as his works. He was viewed as a modern master of the most classic of art forms—sculpture, a tradition that stretched back to ancient times. At the same time, he was always looking ahead, restlessly forging new forms of expression.

Rodin took classical Greek motifs—myths and nymphs—and used them to create something completely new. He loved the broken look of Greek ruins and created his own ready-made fragments. He expanded the age-old repertoire of “acceptable” poses by studying the fluid movements of dancers. He loved the off-balance, unposed pose (which the invention of the camera also helped to capture).

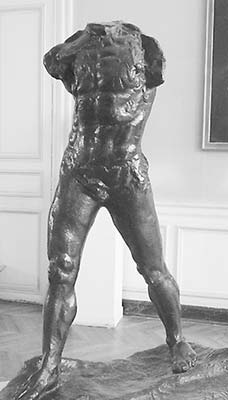

The tall bronze Walking Man (L’Homme Qui Marche, 1900-1907) depicts the bold spirit of the turn-of-the-last-century era. Armless and headless, he plants his back foot forcefully, as though he’s about to stride, while his front foot has already stepped. Rodin captures two poses at once—of a man who has one foot in the classical past, one in the modernist future.

• The visit continues outside in the gardens. There you can see the finished, large-scale versions of many small-scale “studies” you may have seen inside the museum.

Rodin loved the overgrown gardens that surrounded his home, and he loved placing his creations amid the flourishing greenery. These, his greatest works, show Rodin at his most expansive. The epic human figures are enhanced, not dwarfed, by the nature surrounding them.

• Leaving the house, you’ve got four more stops: one to the left and three on the right. Beyond these stops is a big, breezy garden ornamented with many more statues, a cafeteria, and a WC.

Leaning slightly forward, tense and compact, every muscle working toward producing that one great thought, Man contemplates his fate. No constipation jokes, please.

This is not an intellectual but a linebacker who’s realizing there’s more to life than frat parties. It’s the first man evolving beyond his animal nature to think the first thought. It’s anyone who’s ever worked hard to reinvent himself or to make something new or better. Said Rodin: “It is a statue of myself.”

There are 29 other authorized copies of this statue, one of the most famous in the world. The Thinker was to have been the centerpiece of a massive project that Rodin wrestled with for decades—a doorway encrusted with characters from Dante’s Inferno. It’s our next stop, The Gates of Hell.

• Follow The Thinker’s gaze across the gardens. Standing before a tall, white backdrop is a big, dark door...

These doors (never meant to actually open) were never finished for a museum that was never built. But the vision of Dante’s trip into hell gave Rodin a chance to explore the dark side of human experience. “Abandon all hope ye who enter here,” was hell’s motto. The three Shades at the top of the door point down—that’s where we’re going. Beneath the Shades, pondering the whole scene from above, is Dante as the Thinker. Below him, the figures emerge from the darkness just long enough to tell their sad tale of depravity. There are Paolo and Francesca (in the center of the right door), who were driven into the illicit love affair that brought them here. Ugolino (left door, just below center) crouches in prison over his kids. This poor soul was so driven by hunger that he ate the corpses of his own children. On all fours like an animal, he is the dark side of natural selection. Finally, find what some say is Rodin himself (at the very bottom, inside the right doorjamb, where it just starts to jut out), crouching humbly.

You’ll find some of these figures writ large in the gardens. The Thinker and The Shades (c. 1889) are behind you, and Ugolino (1901-1904) dines in the fountain at the far end.

It’s appropriate that The Gates—Rodin’s “cathedral”—remained unfinished. He was always a restless artist for whom the process of discovery was as important as the finished product. Studies for The Gates are scattered throughout the museum, and they constitute some of Rodin’s masterpieces.

• To the left of The Gates of Hell, along the street near where you entered, are...

The six city fathers trudge to their execution, and we can read in their faces and poses what their last thoughts are. They mill about, dazed, as each one deals with the decision he’s made to sacrifice himself for his city.

Rodin depicts the actual event from 1347, when, in order to save their people, Calais’ city fathers surrendered the keys of the city—and their lives—to the king of England. Rodin portrays them not in some glorious pose drenched in pomp and allegory, but as a simple example of men sacrificing their lives together. As the men head to the gallows, with ropes already around their necks, each body shows a distinct emotion, ranging from courage to despair.

Circle the work counterclockwise. The man carrying the key to the city tightens his lips in determination. The bearded man is weighed down with grief. Another buries his head in his hands. One turns, seeking reassurance from his friend, who turns away and gestures helplessly. The final key-bearer (in back) raises his hand to his head.

Each is alone in his thoughts, but they’re united by their mutual sacrifice, by the base they stand on, and by their weighty robes—gravity is already dragging them down to their graves.

Pity the poor souls; view the statue from various angles (you can’t ever see all the faces at once); then thank King Edward III, who, at the last second, pardoned them.

• To the right of The Gates of Hell is a glassed-in building, the...

Unfinished, these statues show human features emerging from the rough stone. Imagine Rodin in his studio, working to give them life.

Victor Hugo (at the far end of the gallery), the great champion of progress and author of Les Misérables and The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, leans back like Michelangelo’s nude Adam, waiting for the spark of creation. He tenses his face and cups his ear, straining to hear the call from the blurry Muse above him. Once inspired, he can bring the idea to life (just as Rodin did) with the strength of his powerful arms. It’s been said that all of Rodin’s work shows the struggle of mind over matter, of brute creatures emerging from the mud and evolving into a species of thinkers.