17

EINSTEIN’S ROAD

TO RELATIVITY

J. RICHARD GOTT

Einstein’s name is synonymous with genius, as in “Hey, Einstein, get over here!” (“Hey, genius, get over here!”) or “He’s no Einstein,” meaning “He’s no genius.” Einstein is famous for being a genius. Newton was also a genius. But around the world and throughout world history there have been other geniuses as well. Who is preeminent in English literature? Shakespeare! From his plays and poems, Shakespeare is often cited as the person in world history with the largest demonstrated vocabulary. His works contain a vocabulary of 31,534 different words. A statistical analysis of his works by Bradley Efron and Ronald Thisted suggests he must have actually known more than 66,000 different words. Shakespeare would take Newton on the Verbal portion of the SAT! But Newton would beat Shakespeare in the SAT’s Math section, I suspect. Newton often gets the edge over Einstein, because in addition to his work in gravity and optics, he made important contributions in math, inventing differential and integral calculus. But Newton was also lucky, born at the right place at the right time—in Europe when they were talking about just these kinds of problems. Newton’s mentor and his professor at Cambridge, Isaac Barrow, was interested in calculating the volumes of barrels and other such objects—a topic that integral calculus would tackle. Clearly, the time was ripe for discovering differential and integral calculus. In fact, the philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz invented differential and integral calculus independently in Europe. If you look at a world map, you see that Newton and Leibniz lived just a few hundred miles apart at roughly the same time. This is not simply a coincidence. Europe was talking about these ideas at that time.

The world of the late seventeenth century was primed for a great discovery, because Kepler had already quantified 600 pages of observations on the positions of the planets, as recorded by Tycho Brahe, and converted them into three simple laws of planetary motion that could be subjected to mathematical analysis. As Michael discussed in chapter 3, Newton used Kepler’s third law to derive the 1/r2 force law for gravity. In similar fashion, in the twentieth century, experimental data on the wavelengths of the hydrogen Balmer series lines gave clues to a formula describing the energy levels in the hydrogen atom and paved the way for a quantum understanding of the atom by Neils Bohr and Edwin Schrödinger.

Time magazine picked Einstein as the most influential person of the twentieth century—the “Person of the Century.” Gutenberg, Queen Elizabeth I, Jefferson, and Edison were each judged most important in their centuries by Time. Shakespeare just missed out, because Time selected Isaac Newton as its “Person of the Seventeenth Century.”

Newton has a very nice life-sized statue of himself in Trinity College, at Cambridge University. William Wordsworth wrote a poem about the statue, calling it:

The marble index of a mind forever

Voyaging through strange seas of Thought, alone.

The statue has an inscription on it: Newton Qui genus humanum ingenio superavit. One translation of this is: “Newton, who in his genius surpassed the human race.” For those like Neil who believe that Newton was the world’s smartest person, here is some real evidence in favor of that—in marble. Einstein has a larger-than-life-sized statue in Washington, D.C., near the Vietnam Memorial, in front of the National Academy of Sciences. He is sitting down, and his statue is still 12 feet tall. Children come and play on his knees.

Now let me compare Einstein and Newton a bit more. I’m not going to contest Neil’s contention that Newton is the greatest scientist ever. I want to give Newton his due. But I am going to argue that Einstein is someone who should compete for this title—someone in Newton’s league.

What is Newton’s most famous equation?

What is Einstein’s most famous equation?

E = mc2.

Which one of these two equations is more famous? Newton’s equation, which we discussed in detail in chapter 3, says that more massive objects are harder to accelerate. Important for dynamics, but pretty simple. It’s harder to get a piano moving than a harmonica. Einstein’s equation says that a tiny bit of mass can be converted into an enormous amount of energy. It is the secret behind the atomic bomb. It tells us how the Sun shines. Which equation seems more important to you?

Newton has another famous equation: F = GmM/r2 for the gravitational force between two particles of masses m and M. This is quite important. Einstein has another equation too: E = hν, where he found that light comes in particles of energy called photons with an energy equal to Planck’s constant h times their frequency ν. Newton thought, to his credit, that light was made of particles, but you might say Einstein proved it. Light has a particle nature as well as a wave nature, a notion that is crucially important for quantum mechanics.

Both men invented things. Newton invented the reflecting telescope. All the big telescopes now are reflecting telescopes. The Hubble Space Telescope and the Keck telescopes are reflecting telescopes. Einstein invented the principle behind the laser. Every time you play a CD or a DVD, you are using Einstein’s invention. Both men did some government work. Newton became Master of the Royal Mint. He invented the milling on the edges of coins that we still use today. This prevented thieves from scraping silver off the edges of silver coins and passing off the coins for full value. If they scraped off the milling, you could tell. Every time you pick up a quarter, you can see Newton’s influence. Einstein’s decisive role in world affairs is well known: he wrote a crucial letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, which led to the Manhattan Project and the atomic bombs that ended World War II. What Einstein did then was so important that we are still dealing with its effects today.

Einstein was such a famous character that people loved to tell anecdotes about him, which then added to the Einstein lore. One such story (perhaps apocryphal) goes like this: Einstein was talking to a man at the Institute of Advanced Study in Princeton. All at once the man reached inside his coat pocket and pulled out a small notebook and scribbled something down. Einstein asked, “What’s that?” “Oh, this is my notebook,” the man said. “I carry it with me everywhere, so if I have a good idea, I can write it down so I don’t forget it.” “I never had need for such a notebook,” Einstein replied. “I only had three good ideas.” So what were these good ideas, and how did Einstein get them?

The first was special relativity, which led to E = mc2. The second was the photoelectric effect, the E = hν equation, for which Einstein won the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics. And the third was general relativity, Einstein’s theory of curved spacetime to explain gravity. After he got the equations worked out, Einstein predicted that light would be bent, traveling in curved spacetime near the Sun, and he also predicted the amount of the bending. Stars seen near the Sun during a solar eclipse should appear in slightly displaced positions in the sky relative to pictures taken months earlier when the Sun was nowhere near those stars. The amount of deflection Einstein predicted (1.75 seconds of arc for stars near the limb, or outer edge, of the Sun) was twice what Newton would have predicted for particles traveling at the speed of light according to his theory. Sir Arthur Eddington led a British expedition to measure this. Einstein’s prediction turned out to be right, and Newton’s prediction turned out to be wrong. Today we believe Einstein’s theory and not Newton’s. Let’s take a moment to appreciate that!

At the close of the twentieth century, I saw a program on its greatest moments in sports: Jesse Owens winning the 100 meters at the 1936 Berlin Olympics; Secretariat winning the Belmont Stakes by 31 lengths, to complete horse racing’s Triple Crown; Mohammed Ali knocking out George Foreman in Zaire, to regain the heavyweight boxing championship of the world. What was the greatest play in science in the twentieth century? Imagine Newton and Einstein on a basketball court.

Newton’s got the ball. He is dribbling the ball down court. And it’s not just any ball, it’s his theory of gravity—the proudest thing he ever did! Einstein comes along, steals the ball, shoots it up, and, swish, it’s in the basket! This is the greatest play in science in the twentieth century.

I want to explain how Einstein got his great ideas. Einstein was good in school. He got good grades in science. Those stories you may have heard that Einstein got all bad grades in school—forget them. He was introduced to science at the age of 4, when his father showed him a compass. Einstein was quite taken with it, and this set him on a career in science. Einstein taught himself differential and integral calculus when he was about 12 years old. Smart fellow. And when he was 16, he started to think about the most exciting physical theory of his day—Maxwell’s theory of electromagnetism. Maxwell put together all the different laws of electricity and magnetism.

Electric charges can be either negative or positive. Opposite charges attract each other and like charges repel each other with a 1/r2 force. Two positive charges repel each other, two negative charges repel each other, but a positive and a negative charge attract each other. This is Coulomb’s law. It causes static electricity. Charges create electric fields, filling the space around them, and if you are a charge, the electric field acts to accelerate you. The electric field causes that 1/r2 electric force. It causes static cling in your clothes in winter. But moving charges create a magnetic field in addition, and a magnetic field can affect you if you are a moving charge. If a charge is not moving, the magnetic force on it is zero, but if it is moving and there are magnetic fields, there will be a magnetic force on the charge. These ideas had been worked out in several more physical laws. Ampère’s law tells you how moving charges (e.g., a current in a wire) create a magnetic field, and if you know the magnetic fields and the electric fields at a given point, you can calculate the electric and magnetic forces on a moving charge at that location. Faraday’s law describes how a changing magnetic field creates an electric field. And it was known that there are no “magnetic charges”; that is, one never finds an isolated north (or south) magnetic pole with a magnetic field spreading out from it. The law of charge conservation states that the total number of charges (number of positive charges minus the number of negative charges) stays constant. For example, if you had 10 positive charges and 9 negative charges in a region, the total charge was +1. A positive and negative charge could combine and eliminate each other, leaving 9 positive charges and 8 negative charges, but the total number of charges would remain +1.

Maxwell looked at the known laws of electromagnetism and showed that they were inconsistent with the law of charge conservation. To rectify this, he showed that a new effect needed to be added: a changing electric field creates a magnetic field. He put all these effects together into a set of four equations: Maxwell’s equations. (You sometimes see physics students wearing them on T-shirts!)

Maxwell’s equations included a constant, c, which was related to the ratio of the strength of electric to magnetic forces. If you had a swarm of charges moving with velocities v, the ratio of magnetic to electric forces they created was of order v2/c2, where c was a velocity. He then did experiments in the lab where he compared magnetic and electric forces to determine what the constant c was, and he got a very high value. He estimated the constant c was 310,740 km/sec. Maxwell also found a highly interesting solution to his own equations: it was an electromagnetic wave that traveled through empty space with velocity c.

The magnetic and electric fields were perpendicular to the velocity of the wave. The wave was sinusoidal, and the electric and magnetic fields oscillated at your location as the sinusoidal wave passed by you. Thus, the electric and magnetic fields were both changing. The changing electric field created the magnetic field, and the changing magnetic field created the electric field, and they bootstrapped themselves along with the wave, moving forward through empty space at a velocity c = 310,740 km/sec.

Eureka! Maxwell recognized that velocity—it was the velocity of light! Light must be electromagnetic waves! It was one of the great moments in science. How did Maxwell know the velocity of light? It was because astronomers—I want to speak up for astronomers here—had measured the velocity of light! In 1676, Danish astronomer Ole Rømer noticed that successive eclipses of Jupiter’s moon Io by Jupiter were more closely separated in time when Earth was approaching Jupiter but were more widely spaced in time when Earth was moving away from Jupiter. Looking at those satellites orbiting Jupiter was like looking at a giant clock face. When we approach Jupiter, we observe the clock running fast, whereas when we move away from Jupiter, we observe the clock running slow. Rømer correctly attributed this to the finite velocity of light. As we approach Jupiter, the distance to Jupiter shrinks, and light beams from successive eclipses have less and less distance to travel to get to us, speeding their arrival. This effect is like a Doppler shift with light beams from successive eclipses being crowded together. He deduced that it must take light approximately 11 minutes to cross the half-diameter of Earth’s orbit. It actually takes about 8 minutes, so Rømer was pretty accurate. When Earth is closest to Jupiter, the Jupiter clock is about 8 minutes fast, and when we are farthest away, the Jupiter clock is about 8 minutes slow. As discussed in chapter 8, Giovanni Cassini, in 1672, measured the parallax distance to Mars, which allowed one to deduce the radius of Earth’s orbit. Using Rømer’s data and knowing the approximate radius of Earth’s orbit, Christiaan Huygens was able to estimate the speed of light: he got 220,000 km/sec (only about 27% low relative to the actual value of 299,792 km/sec).

In 1728, another astronomer, James Bradley, used a different method to measure the speed of light. Imagine a star directly overhead. Its light comes straight down onto you like rain. If you drive in a car, the rain on the windows comes down at a slant, because you are moving. Earth is moving at 30 km/sec in its orbit around the Sun. It’s like moving in a car. If you point your telescope straight up, the light will fall down and hit the side of your telescope rather than reach the eyepiece at the bottom—because you are moving. To see the star, you will have to tilt your telescope to match the slant of the rain you are seeing in your moving vehicle, Earth. How much? It has to be slanted by about 20 seconds of arc. When you observe the same star 6 months later, it will be shifted 20 seconds of arc in the other direction. Bradley was able to measure that effect, called stellar aberration. The slope of this tilt is vEarth/vlight, which Bradley found to be about 1 part in 10,000. Thus he could deduce that the velocity of light was about 10,000 times faster than the 30 km/sec orbital velocity of Earth, or 300,000 km/sec. So, in 1865, when Maxwell predicted that his electromagnetic waves traveling through empty space should have a velocity of about 310,740 km/sec, he recognized it as corresponding to the speed of light, which astronomers had already measured (300,000 km/sec). Within the plausible errors of his prediction (due to errors in his measurements of electric and magnetic forces) and the astronomical observational errors, the two numbers agreed. Light was electromagnetic waves. Maxwell recognized that electromagnetic waves could have wavelengths much shorter or longer than those of visible light. We know the shorter ones today as ultraviolet rays, X-rays, and gamma rays, while the longer ones are known as infrared, microwaves, and radio waves. In 1886, Heinrich Hertz proved the existence of electromagnetic waves by transmitting and receiving radio waves across a room. Maxwell’s was the most exciting scientific theory of Einstein’s day, and Einstein was very excited about it too.

Einstein did the following thought experiment in 1896, when he was just 17 years old. He imagined traveling away from the town clock at the speed of light. As he looked back at the clock, it would seem frozen at noon, because the light showing it at noon was traveling right along with him. Did time somehow stop if you traveled at the speed of light? He imagined looking at the light beam traveling alongside him. He would see static waves of electric and magnetic fields like furrows in a field; they were not moving relative to him. He was traveling along at the same speed as the wave, so it would look static to him. But such a stationary wavelike configuration of electric and magnetic fields in empty space was not allowed by Maxwell’s field equations. What he was seeing out the window of his imagined spaceship seemed impossible. Einstein figured there was a paradox here—something must be wrong. It took him 9 years to figure out how to fix it.

What Einstein did was very original. In 1905, he decided to adopt two postulates:

1. Motion is relative. The effects of the laws of physics must look the same to every observer in uniform motion (motion at constant speed in a constant direction without turning).

2. The speed of light through empty space is constant. The velocity of light c through empty space should be the same as that measured by every observer in uniform motion.

These two postulates are the basis of Einstein’s theory of special relativity. It’s called relativity because “motion is relative” (the first postulate), and special because the motion is uniform. The first postulate you have tested yourself. Have you ever been on a jet plane traveling at 500 miles per hour (in a straight line without turning), with the shades pulled down so you can see some bad movie? It seems just like you are still sitting on the ground. In the moving plane, it seems just like you are at rest. Right now we are orbiting the Sun at 30 km/sec, and yet it seems like we are at rest. This first postulate is the relativity principle: that only relative motions are important, and that you cannot determine an absolute standard of rest. Newton’s law of gravity obeys this postulate. It said that the acceleration (change of velocity) of two particles depended on their separation and had nothing to do with their velocities. Thus the solar system would work the same way if the Sun were stationary with the planets orbiting around it, or if the whole kit and caboodle were moving along at 100,000 km/sec. It wouldn’t matter to Newton whichever was the case. You cannot tell by any gravitational experiment in the solar system whether the whole solar system is moving or not. In fact it is moving, going around the center of the galaxy at about 220 km/sec. Newton’s theory obeyed the first postulate, and Einstein thought Maxwell’s equations should obey this postulate too. All the laws of physics should obey this postulate.

The second postulate is peculiar. It means that if I see a light beam pass me, I must measure its speed to be 300,000 km/sec. But if another person comes running past me at 100,000 km/sec and looks at the same light beam, he must not measure it to be going at 200,000 km/sec, as you might think. He must see it going 300,000 km/sec, just like I do. It’s crazy!

It doesn’t make any common sense. Velocities should add. In fact, the only way it can make sense is if his clocks are ticking at a rate different from mine and if his measurements of distance are also different from mine. Remarkably, what Einstein did was to believe these two postulates and throw common sense right out the window! If this were a chess game, we would call this a “genius move” (denoted this way: !!), the kind of move that forces a checkmate 17 moves later. Einstein was going to assume these two postulates were true, prove theorems based on thought experiments derived from the postulates, and see what he got. If those theorems were then checked with observations and turned out to be correct, then that would be evidence that the postulates were true. This was amazing. No one had ever done anything quite like it before. Einstein’s postulates were falsifiable.1 If Einstein’s theorems gave answers that were contradicted by observations, his theory would be proven wrong. If the theorems agreed with observations, while it would not prove the postulates themselves, it would certainly provide evidence supporting them.

Why did Einstein believe the second postulate? It was because the velocity of light was a constant in Maxwell’s equations, related to a ratio of magnetic to electric forces you could measure in the lab. Maxwell calculated that light waves traveled through empty space at about 300,000 km/sec. If you saw a light beam passing you at any other speed (say, at 200,000 km/sec), you would be able to deduce that you were moving at 100,000 km/sec—you could deduce you were moving. That would violate the first postulate. In 1887, Albert Michelson and Edward Morley, in a famous experiment, tried to measure the velocity of Earth moving around the Sun by bouncing light beams off mirrors in their laboratory. Effectively, they measured differences in the speed of light relative to their lab for light beams traveling parallel and perpendicular to the velocity of Earth. They achieved enough precision to be sensitive to the 30 km/sec velocity of Earth around the Sun. Amazingly, they got a result of zero for the velocity of Earth, as if Earth were stationary and light beams in all directions traveled at the same speed relative to their lab. But we know Earth is moving—we see stellar aberration. It was quite puzzling. But their result is exactly what Einstein’s second postulate would have predicted. You would always measure the speed of light to be the same whether Earth were moving or not, and therefore, if you believed the second postulate, you would have predicted that Michelson and Morley should have gotten a result of zero.

So, Einstein is going to believe his two postulates and prove theorems based on them. Here is one result. You can’t build a rocket ship that travels faster than light. Why is that? Suppose I shine a laser beam toward a wall in my living room; it hits the wall. I am allowed to think I am at rest. But if you built a rocket that was going faster than light, and tried the same experiment on board the rocket, you would get a different result. If you sat in the middle of your rocket ship and directed your laser beam toward the front end of your ship, it would never get there. Any athlete can tell you that you cannot catch a runner who is faster than you and has a head start. The light beam from the laser can’t catch the front end of the rocket, because the front end of the rocket is traveling faster (faster than light) and it has a head start. Clearly, if you did this experiment on the rocket ship, the laser beam would never reach the front end of the rocket, and you would know that you were moving (faster than the speed of light, in fact). But wait—that’s not allowed by the first postulate. Since you are going at constant speed without turning, you must not be able to prove that you are moving. You must get the same results that I get in my living room. From this, it follows that you must not be able to build a rocket ship that travels faster than the speed of light. A strange result, but if you believe the two postulates, you must believe this result also. If you go slower than the speed of light, the laser beam eventually catches the front end of the rocket. It might take a very long time, but if your clocks were ticking slowly, for example, it might work out fine. Traveling slower than the speed of light is okay, but you can’t build a rocket that travels faster than light. We have tested this in our particle accelerators, where we make particles like electrons and protons go faster and faster, nudging them ever closer to the speed of light but never quite reaching it.

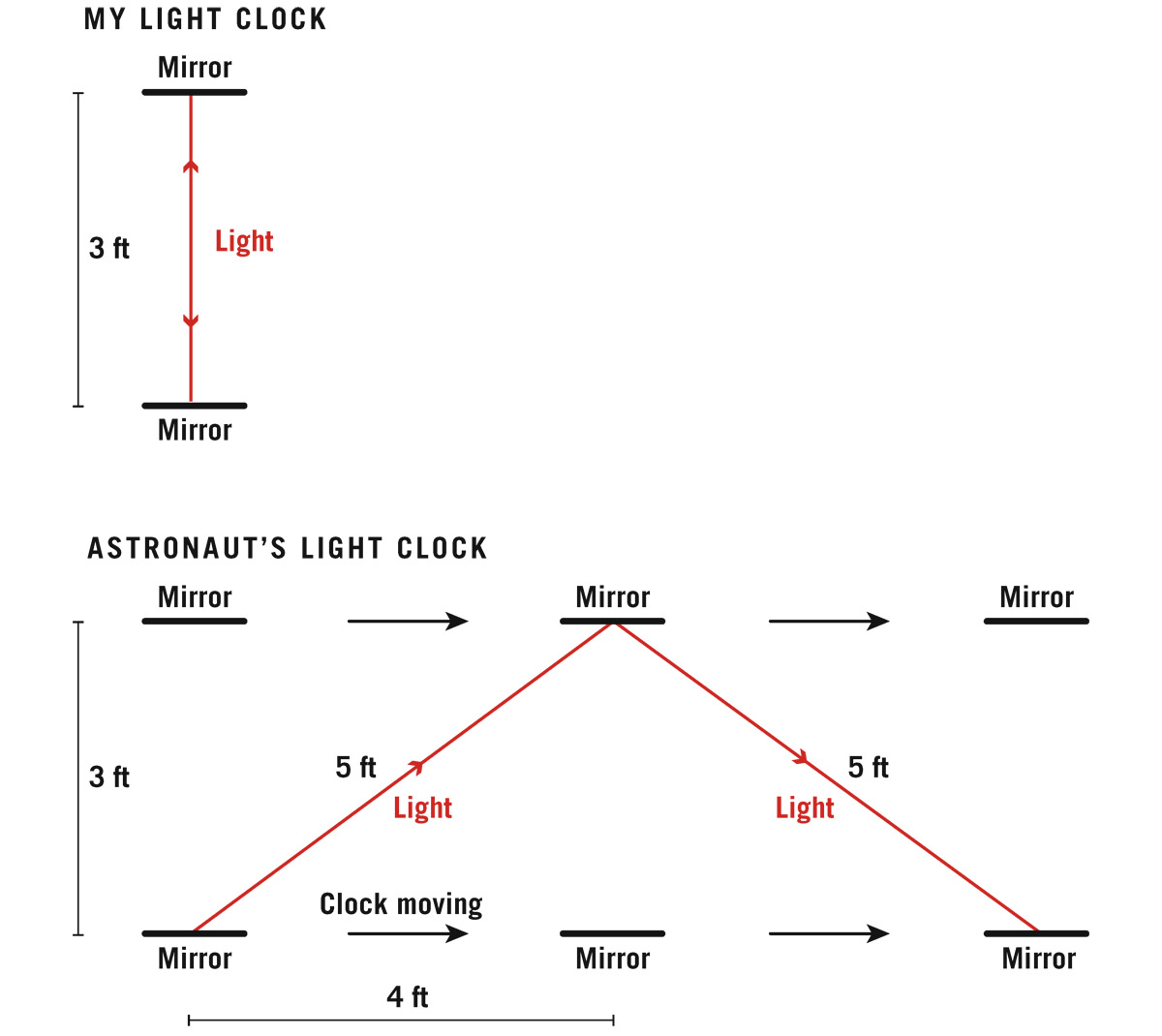

Here is another result. Imagine a “light clock,” in which a light beam bounces vertically between two mirrors, say, one on the ceiling and one on the floor; each bounce represents a tick of the clock. Light travels at 300,000 km/sec, or about 1 foot per nanosecond. One nanosecond is one billionth of a second. If we separate the two mirrors vertically by just 3 feet, the clock will tick once every 3 nanoseconds (figure 17.1).

FIGURE 17.1. Light clocks. My light clock ticks once every 3 nanoseconds. A similar light clock is carried by an astronaut moving at 80% of the speed of light relative to me. Light moves at a constant velocity of 1 foot per nanosecond. I see the light beams in the astronaut’s clock traveling on long diagonal paths 5 feet long, and therefore I see the astronaut’s clock ticking only once every 5 nanoseconds.

Credit: Adapted from J. Richard Gott (Time Travel in Einstein’s Universe, Houghton Mifflin, 2001)

It’s a very fast clock, like a grandfather clock, only much faster. The light beam will bounce up and down, up and down, between the two mirrors. It hits a mirror once every 3 nanoseconds. This is my light clock. Now imagine an astronaut who passes me going left to right at 80% the speed of light, holding a similar light clock (figure 17.1). That’s slower than the speed of light, so she can do that. From the point of view of the astronaut, she sees her light clock ticking normally with the light beam going up and down, ticking every 3 nanoseconds according to her. But if I look through the window of her space ship, I see her light clock moving along at 80% the speed of light and I see her light beam traveling on a diagonal path. The light beam starts at the bottom, but by the time it has moved up 3 feet, the upper mirror has moved from left to right by 4 feet. The light beam travels on a diagonal path that is 5 feet long. We have a 3-4-5 right triangle—3 feet vertically, 4 feet from left to right, and 5 feet along the diagonal hypotenuse. It solves Pythagoras’s theorem 32 + 42 = 52. While relative to me the light beam moves 5 feet diagonally from bottom left to top right, the astronaut moves 4 feet from left to right. Thus, she is traveling at 4/5 or 80% of the speed of light relative to me. Since I must observe the light beam to be traveling at 1 foot per nanosecond (according to the second postulate), I must say it takes 5 nanoseconds to go from bottom left to top right on the diagonal path of 5 feet I observe. I must see it take another 5 nanoseconds to come diagonally back down, arriving 8 feet to the right of where it started. Thus, I must say her clock ticks only once every 5 nanoseconds rather than once every 3 nanoseconds. I must see her clock ticking slowly (at 3/5 of the rate mine does).

Now for the interesting part. I must observe the astronaut’s heart to be ticking slowly (also at 3/5 of the rate of mine), or she would notice that her light clock was ticking slowly relative to her heart, and she could deduce that she was moving, which is not allowed by the first postulate. Any clock she has on board must also be ticking slowly, at the 3/5 rate, or else she would be able to tell that she was moving. If she has a muon (an unstable elementary particle heavier than the electron) that is decaying, it must decay more slowly. She must age more slowly. She eats dinner more slowly. And . . . she . . . talks . . . more . . . slowly. Every process on the rocket ship goes more slowly.

How much more slowly depends on the astronaut’s velocity v: if I age 10 years, a similar calculation using the light clock2 shows the astronaut ages 10 years times √[1 – (v2/c2)]. For velocities that are small compared with the speed of light, such as we encounter in everyday life, this aging factor will turn out to be nearly exactly 1. If v/c is small relative to 1, then (v2/c2) will be really tiny relative to 1; something really tiny subtracted from 1 leaves something still about equal to 1, and the square root of 1 is 1—all of which means that this factor does not appreciably change the astronaut’s aging. That is, the astronaut would also age 10 years, and I wouldn’t notice any difference between her aging and mine. That’s why we don’t ordinarily notice that moving clocks are ticking slowly. However, if the astronaut is moving at a speed close to the speed of light—say, at 99.995% the speed of light—then v/c = 0.99995 and √[1 – (v2/c2)] is only 0.01. You can check that on a calculator. While I age 10 years, I observe the astronaut aging only 1/10 of a year. At velocities approaching the speed of light, the slowing of time on the spaceship can be very dramatic.

We believe this formula, because we have checked it experimentally. Physicists took atomic clocks on plane trips around the world, going east so that the velocity of the plane added to the rotational velocity of Earth, and they observed that those atomic clocks came back slow (by about 59 nanoseconds) relative to atomic clocks left on the runway—just as Einstein would have predicted. Muons in the lab decay with a half-life of 2.2 microseconds—meaning half of them decay in 2.2 microseconds. But muons that are traveling toward Earth at nearly the speed of light (as cosmic rays) decay much more slowly, in accord with Einstein’s formula. We believe this formula is right, because we have tested it many times. This is a funny universe, operating in surprising ways, but it seems to be the universe in which we live. Einstein’s two postulates seem to be true. We’ll see in the next chapter that these postulates also lead to the conclusion that E = mc2, and that was verified in the atomic bomb. These are some truly remarkable results. The results are remarkable, because the postulates are remarkable. The more all these theorems check out, the more we may trust that the postulates are true.