Morphologic Manifestations of Toxic Cell Injury

Matthew A. Wallig1 and Evan B. Janovitz2, 1University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, United States, 2Bristol-Meyer Squibb Company, Princeton, NJ, United States

Abstract

Whatever causes injury to a cell—toxicant, toxin, infectious agent, or otherwise—the result is a simple or complex biochemical shift that generally results in a morphologic change, which can be observed in some form. The pathologist must be able to recognize that such changes in morphology reflect a significant alteration in the cell’s homeostasis and then must decide whether or not this finding indicates reversible injury, irreversible injury, or adaptation to the new situation. Visible manifestations of disrupted function, whether ultrastructural, microscopic, or macroscopic, are lesions by definition, and lesions are still the primary means by which a toxicologic pathologist arrives at a diagnosis, hopefully one that includes the etiology as well as a description of the underlying morphologic alterations and a plausible pathogenesis of how the lesions came about. This chapter serves as an overview of the basic histologic and ultrastructural features that reflect cell injury and cell death as well as the sequelae to such processes.

Keywords

Adaptation; adenosine triphosphate (ATP); apoptosis; apoptotic; atrophy; autophagic cell death; autolysis; autophagy; calcium; caspase(s); cell injury; cell swelling; cytochrome c; fatty change; fibroblast; fibrosis; glutathione; high-amplitude swelling; homeostasis; hyperplasia; hypertrophy; hypoxia; irreversible; lipid; lipidosis; lysosome(s); macrophage; metaplasia; mitochondria; mitochondrial; necrosis; necrotic; neutrophil; programmed cell death; reversible; rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER); smooth endoplasmic reticulum (sER); sequela(e); sodium; vacuolar change

Introduction

Structural and Functional Components of Cell Injury

Living cells are complex structures comprising an interdependent array of many essential components including organelles, fluids, proteins, electrolytes, signaling molecules, and plasma membrane receptors. Although injury to any one of these components can ultimately result in death of the entire cell, some are particularly critical for cell survival: the plasma membrane is the site of osmotic, electrolyte and water regulation, and receptor-ligand signal transduction; the mitochondrion is the site of aerobic respiration and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) generation; the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is the site of most protein synthesis and calcium storage; and the nucleus, where DNA transcription occurs. The biochemical consequences of damage to these structures have been discussed in Chapter 2, Biochemical and Molecular Basis of Toxicity. Other structures, such as lysosomes, peroxisomes, secretory granules, microtubules, microfilaments, and even the extracellular matrix (ECM), may be altered in cell injury, but these generally reflect penultimate changes rather than the proximate cause of cell death.

Cell Injury in Context

The onset and progression of cell injury depend on the nature of the noxious insult, including its severity and duration. If injury to the cell is mild and not persistent, recovery is usually rapid and complete; a morphologic manifestation may be absent or imperceptible although a temporary functional disruption and/or a brief biochemical alteration may be detectable. For example, transient release of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) from hepatocytes into plasma after administration of a mild hepatotoxic compound for a short period of time may not be evident microscopically. At the other extreme, a potent hepatotoxic compound may cause such widespread necrosis that hepatocyte ALT content is no longer sufficient to be detectable in serum even though the lesion is obvious at the macroscopic level. If the compound is still detectable in blood or tissue by analytical techniques, a presumptive diagnosis is possible. But with chronic tissue injury, such as glomerulosclerosis or retinal atrophy, the etiology may be indeterminable. Cell injury can be manifested exclusively by functional deficits without perceptible morphologic manifestations. Such injury could even result in death of the animal. The complete disruption of oxidative phosphorylation by acute cyanide toxicity is such an example.

The metabolic rate of a cell has a significant effect on lesion development. Cells with high metabolic activity are generally more sensitive to noxious injury than cells with low energy needs. For example, neurons are quite sensitive to hypoxia while fibroblasts are quite resistant. Metabolically active cells absolutely depend on a continuous supply of oxygen (O2) and functional mitochondria to generate ATP for sustaining cell function. Toxic injuries that break the link between O2 diffusion from inhaled air across pulmonary alveoli, to the O2-carrying capacity of red blood cells, to blood vessels, to mitochondria where oxidative phosphorylation and ATP generation occur can subsequently injure cells with high energy needs. Adequate cellular ATP is necessary to maintain normal structure and function of many vital, specialized cell populations, such as neurons that require energy to sustain membrane integrity and polarity as well as neurotransmitter production, myocardial cells that require energy for myofilament contraction/relaxation and Ca+2 transport, and renal tubular epithelial cells that require energy for transport of fluids, electrolytes, and metabolites. Even small changes in cellular O2 tension leading to mildly decreased ATP production can cause serious alterations in essential functions of these cell types, with severe consequences for survival. Shifting to anaerobic glycolysis is inefficient and leads to lactic acidosis. By contrast, cells with low metabolic activity, such as fibroblasts and adipocytes, are resistant to low O2 supply and can tolerate hypoxic conditions. Hence, these connective tissue elements can play prominent roles in regeneration and scarring.

Highly specialized cells are generally more sensitive to toxic insult than connective tissue cells. The latter, such as fibroblasts, are “plastic” in their adaptability to a variety of conditions, assuming an assortment of different roles due to their relatively undifferentiated nature and broad functional capabilities. These cells can tolerate anaerobic conditions and many types of toxic insults. In contrast, highly specialized cells, such as retinal rods and cones, must expend abundant energy to maintain their membranes in conformations capable of trapping photons (see Chapter 22a: Special Senses—Eye). Hence, they are exquisitely sensitive to injury.

The specialized functions of a given cell may predispose it to a particular type of noxious insult. Specific receptors on a cell population may render it susceptible to insults that would not impact neighboring cell types. For instance, cells expressing the fas receptor may undergo apoptosis when fas ligand binds to their receptors, whereas cells without this receptor will be unaffected. Some cells may accumulate toxicants because they have specific transporters that facilitate uptake of the molecule. For example, the nephrotoxicity of gentamicin, and similar aminoglycoside antibiotics, depends on the organic cation transport system that leads to gentamycin accumulation in lysosomes. Lysosomes eventually rupture hastening cell death. Pancreatic acinar cells are especially sensitive to excessive dietary intake of lysine or arginine. Toxicity may be further enhanced if the target cell is incapable of metabolic detoxification or metabolizes the toxicant to a more reactive chemical species. Phase I metabolism, especially by certain members of the cytochromes P450 (CYP) family, is particularly important in bioactivation of xenobiotics to toxic intermediates. For example, the presence in the hepatocyte of CYP 2E1 makes it uniquely susceptible to damage by acetaminophen, which is bioactivated to a highly reactive quinone imine by this CYP isozyme.

The “innate” ability of a cell to counter an injurious stimulus can be critical for resisting a toxic insult. For example, cells with high levels of antioxidants are typically resistant to oxidative injury. The liver, which receives 60% of its blood supply directly from the gastrointestinal tract through the portal vein, can generally tolerate a remarkably high level of potential noxious agents originating from the gut. This tolerability is attributable to high concentrations of antioxidants such as reduced glutathione and vitamins C and E, and a broad array of phase I and phase II detoxification enzymes within hepatocytes. Of course, being rich in metabolizing enzymes is a “double-edged sword” since otherwise innocuous compounds may be metabolized to highly bioactive, toxic intermediates, which deplete glutathione and then bind to proteins or nucleic acids. Cells lacking high concentrations of endogenous antioxidants and/or antioxidant enzymes or that are missing the appropriate quantities or combinations of phase I and phase II enzymes can be especially prone to toxic injury. This vulnerability is heightened if cells tasked with detoxification, like the hepatocyte or the bronchiolar exocrine (club or Clara) cell in the lung, fail to detoxify harmful substances before they reach the general circulation.

Host Reactions to Cell Injury

Host reactions to injured or dead cells often play a key role in the morphologic manifestation of toxic cell injury. The inflammatory reaction to injured cells can amplify the original toxic injury to a more substantial lesion or even a life-threatening condition. Thus what could have been a relatively mild and recoverable injury can progress to a severe, nonresolving lesion. For example, acute necrotizing pancreatitis induced by acinar cell toxicants is exacerbated by activated neutrophils attracted by released zymogen granules. Neutrophils release a variety of preformed and de novo-generated chemicals that indiscriminately destroy even previously unaffected cells in the vicinity of the original injury. With necrotic cell death, the inflammatory reaction is provoked by leakage of intracellular contents and signaling proteins from disintegrating (parenchymal and inflammatory) cells. This process especially attracts neutrophils, the “foot soldiers” of the acute inflammatory response. In contrast, with apoptotic cell death, an orderly sequence of cell senescence preserves membrane integrity. The sequestration of intracellular materials within the debris (apoptotic bodies) permits macrophages to scavenge potential pro-inflammatory products before they can be released. Therefore, it is important to remember that the inflammatory reaction to apoptotic (so-called “programmed”) cell death is muted or even absent altogether.

All the aforementioned factors and more contribute to the varied susceptibility of different cells and tissues to injury. Regardless of the type of injury or the factors present that mitigate or exacerbate that injury, a given cell population has only a limited number of responses available for survival and repair.

Adaptation

A cell exists within a narrow range of physiochemical conditions necessary to maintain a viable state. Thus, a cell, even a highly specialized one, dedicates much of its resources toward maintaining this homeostatic internal environment. Ion gradients, intracellular pH, and cytosolic osmolarity are vigorously maintained by the cell, even at the cost of its own specialized functions. A cell threatened with a loss of homeostasis will often jettison its specialized structures and cut back on its specialized functions, regardless of whether these functions are critical to the survival of the host, in order to maintain homeostasis of the cell. Substantial deviations from homeostasis lead to death of the cell. Less substantial deviations may lead to a new, usually reduced, level of function or metabolic activity in an attempted compromise between overall cell survival and specialized cell function. The response of a cell to disrupted homeostasis while maintaining some degree of function and avoiding death is called adaptation.

Atrophy

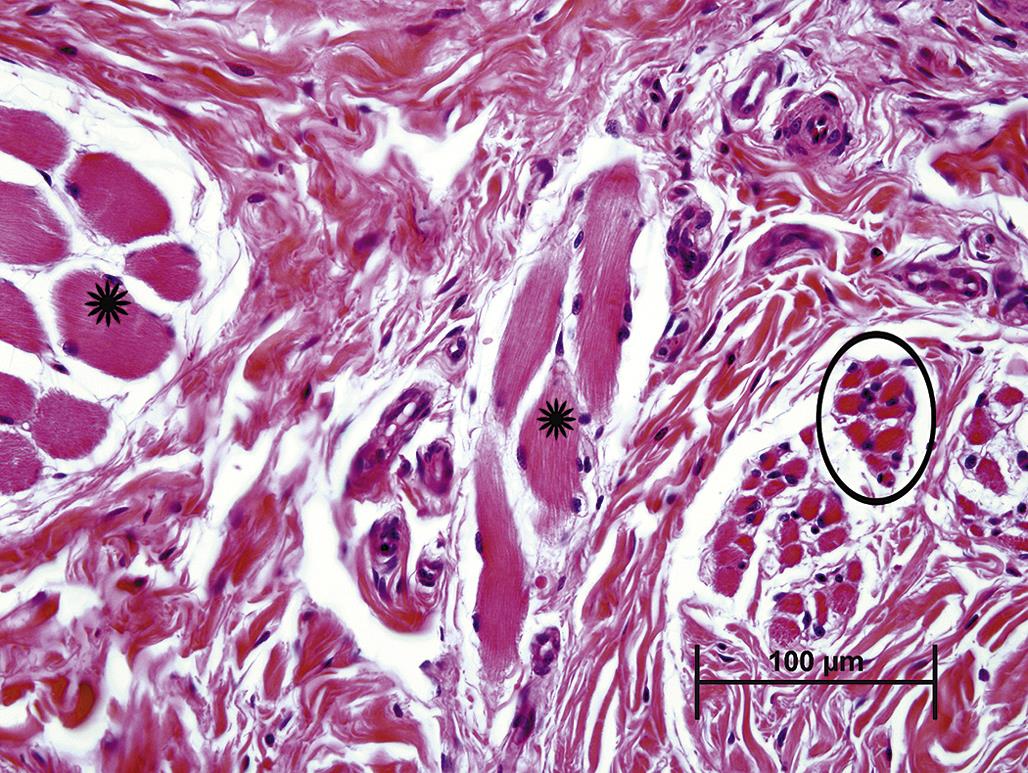

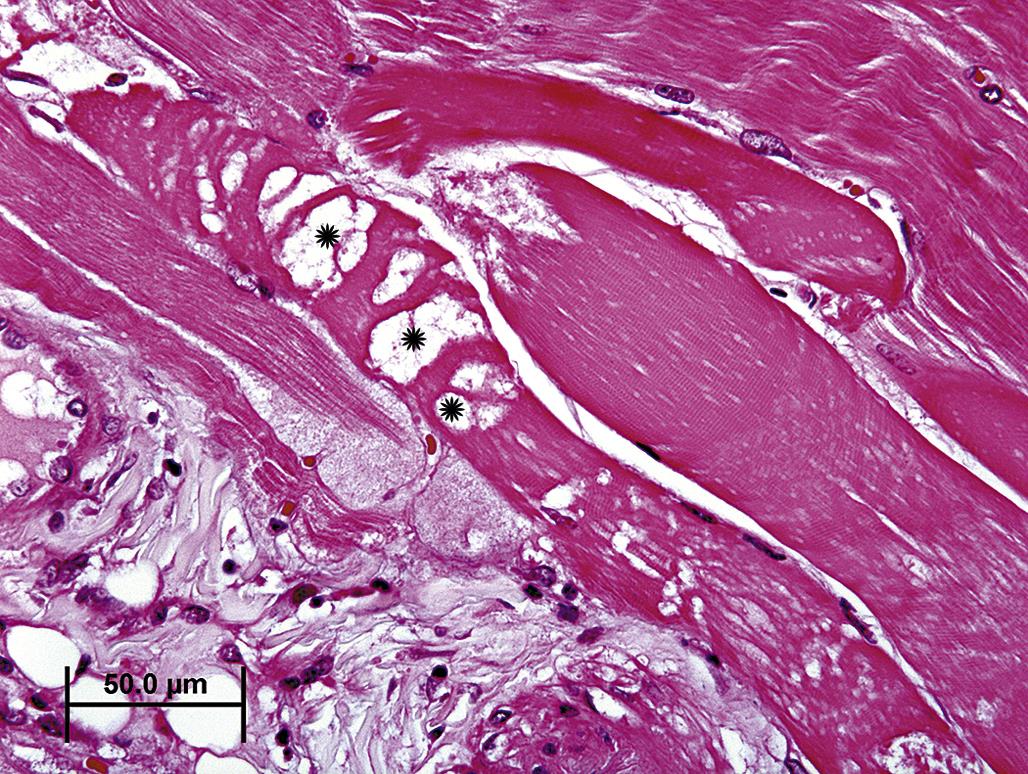

Atrophy is an adaptive change characterized by a reduction in the size of a cell, tissue, or organ. Cell atrophy can simply result from lack of use, such as occurs in skeletal muscle fibers after denervation or with immobilization. The lack of muscle contraction leads to a reduction in sarcoplasmic contractile proteins, which is evident microscopically as a decrease in myofiber diameter (Figure 5.1). Atrophy can also result from a lack of hormone stimulation. Deficiencies in pituitary trophic hormones, such as thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) or adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), lead to atrophy of thyroid follicular and adrenal cortical epithelial cells, respectively, resulting in atrophy of that portion of each gland where unstimulated cells reside. The severity of atrophic changes is dependent on both the degree and duration of stimulus withdrawal. Complete loss of stimulation for an extended period of time can lead to autophagy (see below) and senescence. Cell atrophy can also result from an insufficient supply of energy or substrates required to maintain structure and function. For example, pressure from an adjacent tumor can disrupt normal circulation leading to hypoxia or insufficient delivery of glucose for ATP generation or amino acids to maintain structural proteins. Cells that are capable of surviving in such an adverse environment will undergo atrophy. Cells in the immediate vicinity of the tumor may be compressed and distorted by physical displacement.

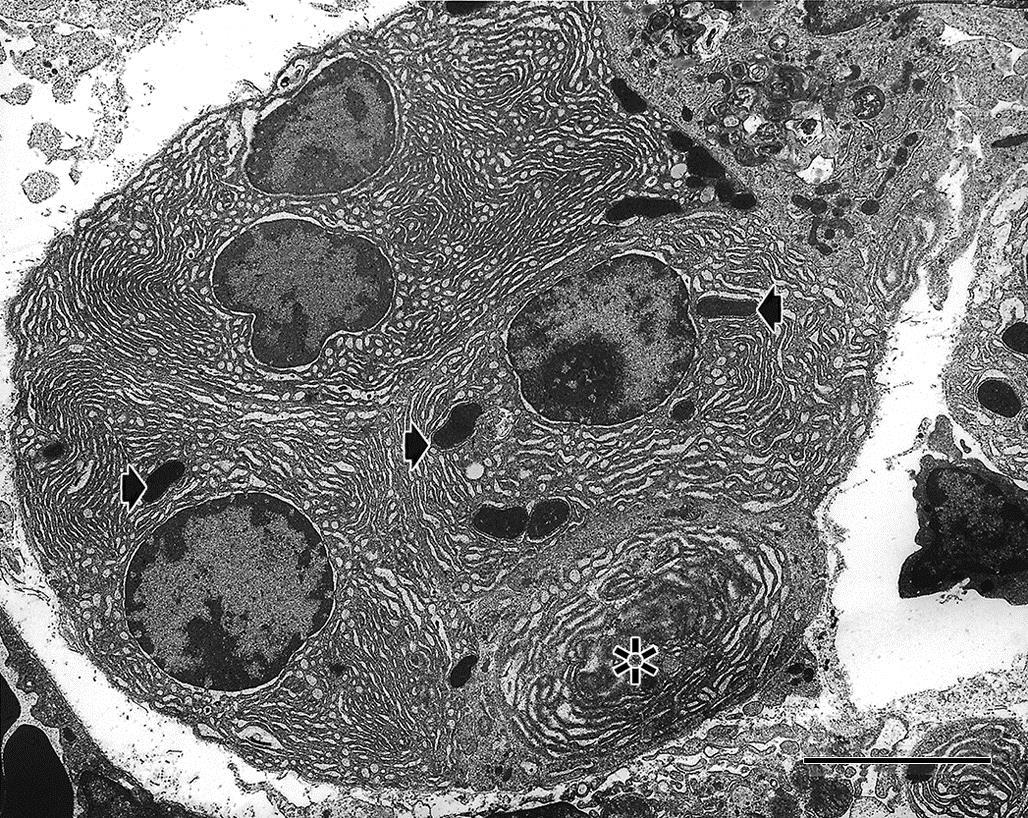

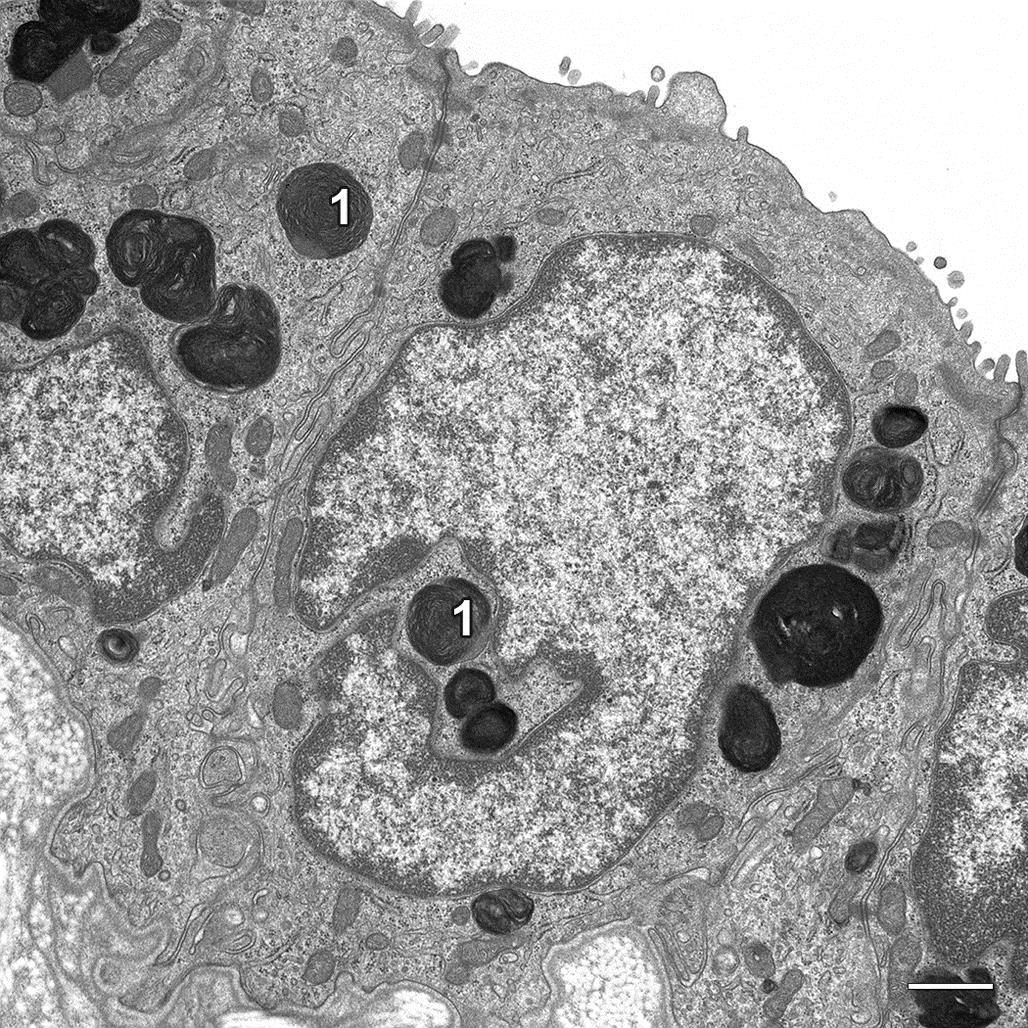

At the subcellular level, an atrophied cell may show morphologic evidence of an adaptive catabolic state reflecting the reduced demand for use or supply of substrates. Affected cells not only may be reduced in size but also may lack organellar features typical for a fully functional cell of that particular phenotype (Figure 5.2). Often atrophy is accomplished by a process termed autophagy. Autophagy is characterized by sequestration of degenerate organelles in a vesicle (defined by an “induction membrane”), termed an “autophagosome” (or autophagic vacuole). Autophagosomes ultimately fuse with a lysosome to form autophagolysosomes, where enzymatic digestion of the vesicle contents can provide a source of recycled macromolecules. The autophagocytic process is observable by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Initially, enveloped organelles may be structurally disrupted but remain largely intact and recognizable within discrete double-layered membrane-bound vesicles, a process termed “macroautophagy.” As degradation proceeds, organelles lose their distinctive structural features, and the vesicles tend to be defined by a single-layered membrane. Amorphous vesicles containing electron-dense granular material often represent residual bodies, an end-stage of autophagolysosomes, or a process termed “microautophagy,” which is characterized by tubular proteasome formation associated with ubiquitin-mediated destruction of proteins. Autophagy can be so severe that the cell undergoes cell death in a modified form of apoptosis, termed “autophagic cell death.” In this case, the ultrastructural and histologic morphology of the affected cell resembles closely the classical form of apoptosis (see later), but without the nuclear changes typical of apoptosis. Cells undergoing autophagic cell death are generally not removed by macrophage ingestion.

The contents of residual bodies are typically nondegradable complex lipids and lipoproteins that collectively may be termed lipofuscin or ceroid “wear and tear” pigments (Figure 5.3). Residual bodies are particularly common in longer lived, metabolically active cells that have a high turnover of membrane components, such as striated muscle cells, neurons, and hepatocytes.

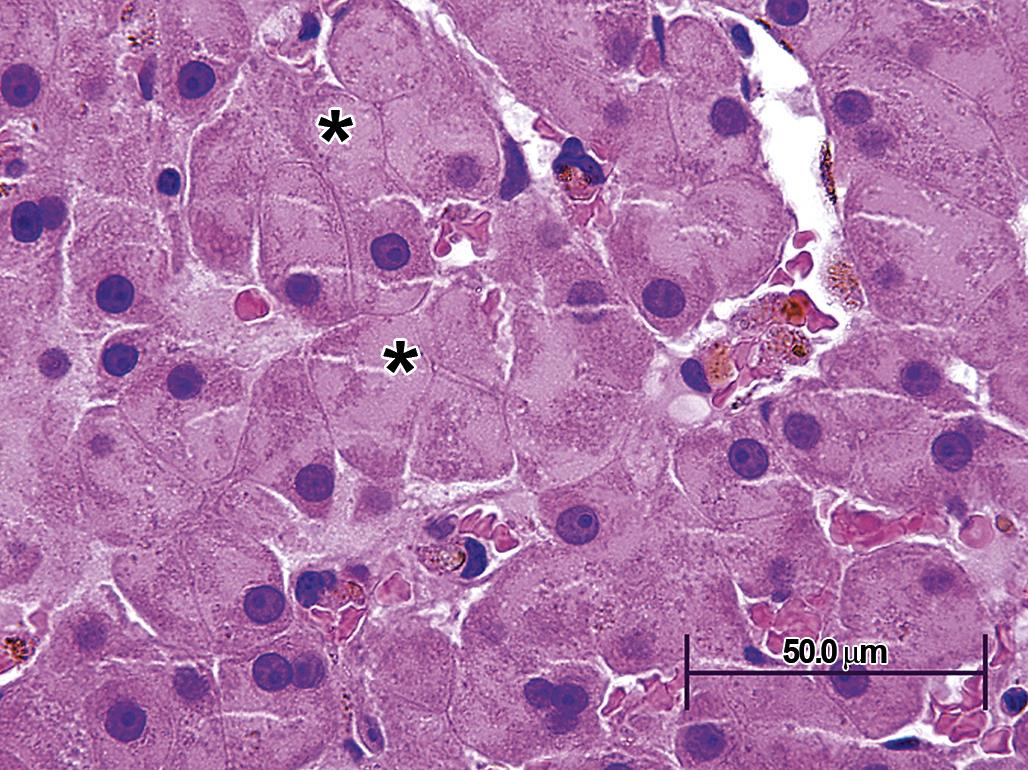

Atrophic cells may lose some, or all, of their specialized structures such as microvilli, cilia, contractile apparatuses, or secretory granules. In the extreme, an atrophic cell may not be recognizable as a specialized cell at all (Figure 5.4). Under light microscopy with standard hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, an atrophic cell is typically small with reduced amounts of cytoplasm that may contain eosinophilic droplets, reflective of retained autophagosomes, or red-brown or golden-brown pigment granules, which represent residual bodies filled with lipofuscin and ceroid pigments. Grossly, an atrophic organ may simply appear small and pale but with normal conformation, such as thyroid glands following prolonged lack of TSH stimulation, or may be shrunken and deformed as a reflection of the underlying etiology, such as shrunken, irregularly contoured, gray, and firm kidneys resulting from chronic interstitial inflammation and fibrosis.

Tissue or organ atrophy can also result from a decrease in the number of normal-sized cells subsequent to cell death, for example, by apoptosis or necrosis (discussed in more detail later), or insufficient cell replacement. Atrophic tissue often displays the mechanism of cell death. When cell loss has occurred via widespread apoptosis, tissue macrophages may be prominent within the atrophic tissue (Figure 5.5). Vacuoles, representing phagolysosomes or residual bodies containing remnants of dead cells in various stages of degradation, may be evident within surviving cells or within nearby tissue macrophages. Apoptotic bodies may be observed (Figure 5.6), but if apoptosis has waned inflammation is usually absent. Grossly, atrophic organs resulting from loss of cell numbers may be indistinguishable from atrophic tissue resulting from reduction in cell mass, but when subtle the decrease in organ size may only be revealed by reductions in absolute or relative organ weight.

Tissue or organ atrophy resulting from overt cell necrosis is evident by light microscopy by the presence of swollen or lysed cells, with spillage of the cells content (Figure 5.7). Where patent capillary beds remain, inflammatory cell infiltration is typical. Chronically, after necrotic cells are removed, fibrosis, evident grossly as firmness and pallor, will ensue to replace the void left by the lost parenchymal tissue.

Hypertrophy

Hypertrophy is an adaptive increase in the mass of a cell, tissue, or organ that does not result from cell proliferation, that is, hyperplasia. The most common example of hypertrophy in toxicologic pathology is xenobiotic induction of hepatocyte metabolizing enzyme systems, which leads to expansion of hepatocyte cytoplasm. Elevations in serum transaminases (due to leakage across the plasma membranes of swollen cells) or even hepatocyte necrosis can result from handling of mice with severely enlarged livers after xenobiotic treatment.

Endogenously, hypertrophy is commonly a response to increased demand for the specialized function provided by the particular cell population. Endocrine cells responsive to trophic hormones often undergo hypertrophy when stimulated by the appropriate hormonal ligand. Hypertrophy of gonadotrophic adenohypophyseal cells in response to gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus at the onset of puberty is a classic example. By light microscopy, hypertrophy appears as an increase in the volume of cytoplasm, which may be more granular if accompanied by organelle hyperplasia. The nuclei of hypertrophied cells are often enlarged and contain a prominent nucleolus. By TEM, hypertrophied cells are usually replete with morphologically normal organelles, although certain organelles may also be enlarged or more numerous, for examples, peroxisomes, ER, or cytoskeletal microfilaments. Diffuse but subtle cell hypertrophy may be imperceptible by standard microscopy but can be discerned grossly by organ weight increases or by morphometry if necessary.

In toxicologic pathology, hepatocyte peroxisome proliferation is the classic, although now somewhat historical, example of organelle hyperplasia causing cell and organ hypertrophy. Xenobiotics that agonize peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs, especially PPAR-α) on the nuclear membrane induce activation of particular transcription factors, which subsequently lead to such widespread proliferation of peroxisomes that hepatocytes are noticeably enlarged, with abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 5.8).

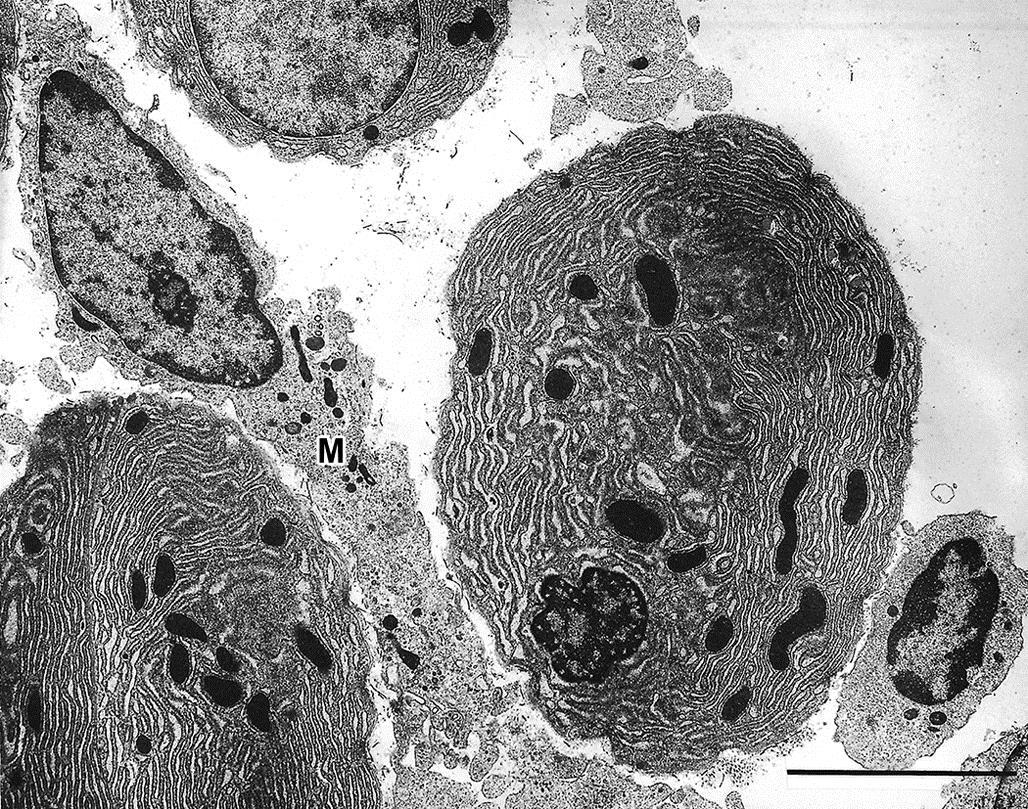

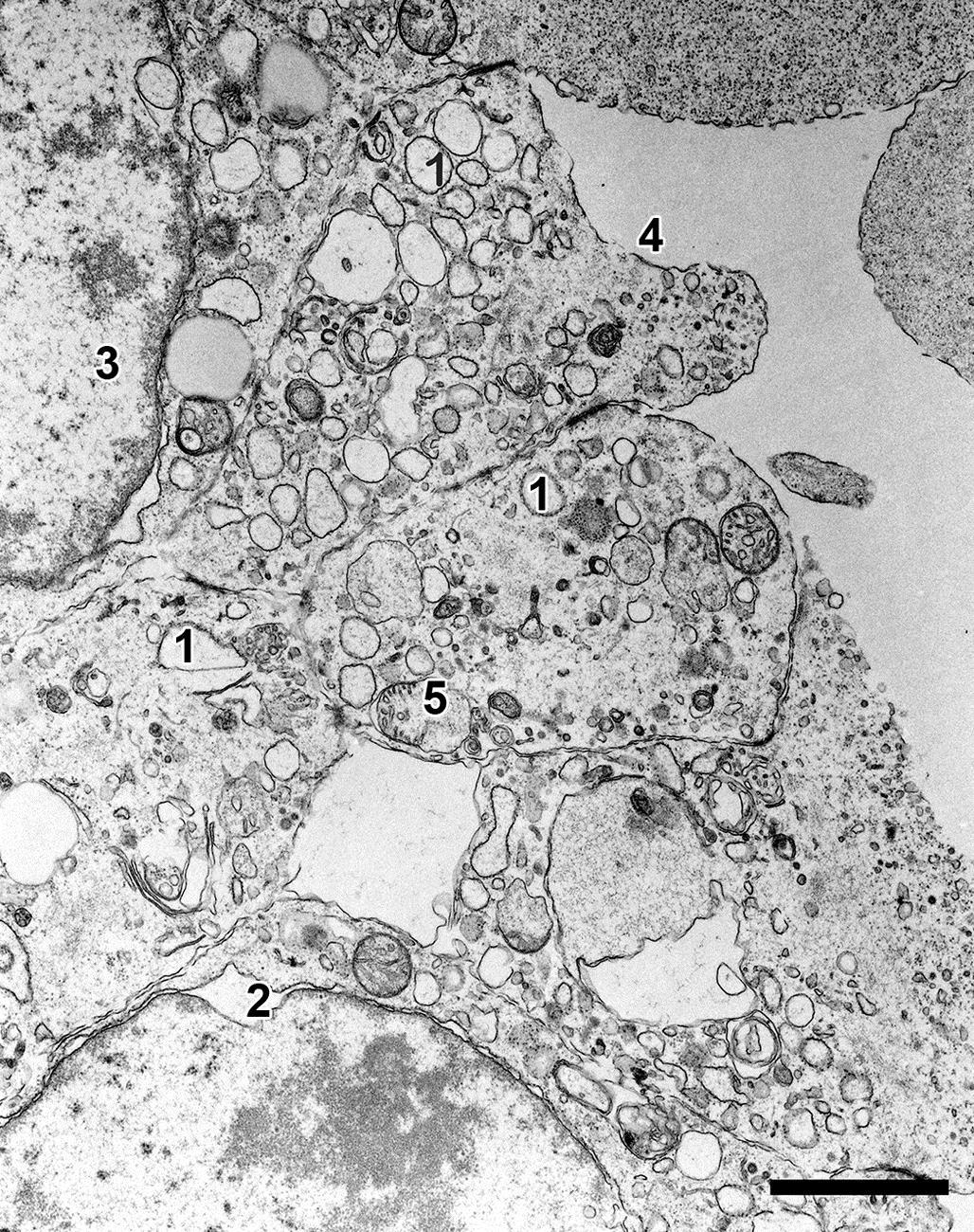

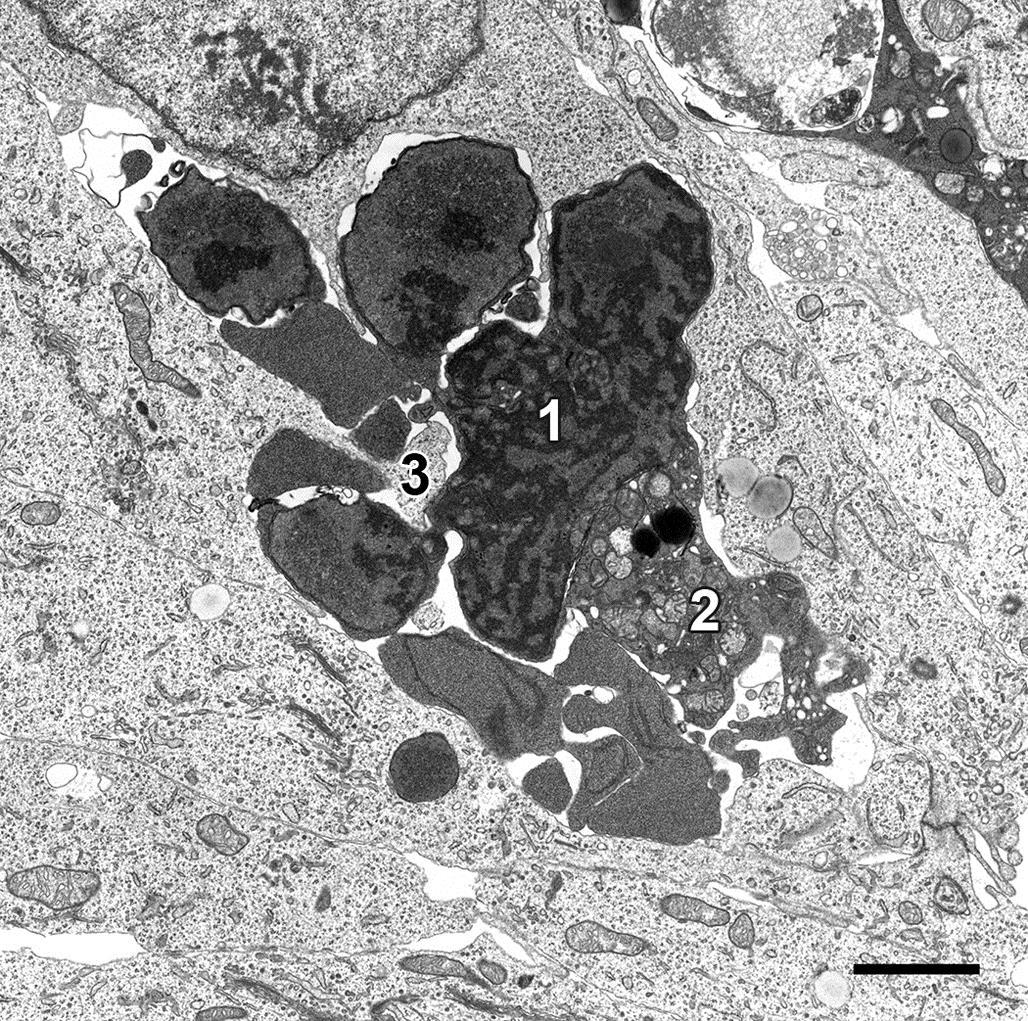

Although not necessarily considered hypertrophy by every pathologist, phospholipidosis is another common cause of xenobiotic-induced cell enlargement due to organelle accumulation. Cationic amphiphilic compounds accumulating in lysosomes can alter degradation of phospholipid-rich membranes. With standard processing for light microscopy, most of the retained lipid-soluble breakdown products dissolve leaving abundant, finely vacuolated, or “moth-eaten” appearing, cytoplasm. With processing for TEM, the lipids are retained so that “vacuoles” appear as enlarged, discrete, membrane-bound bodies containing laminated whorls of partially degraded membranes, termed “myelin whorls” (Figure 5.9).

Often cell or even organ hypertrophy is not injurious, especially in the short term, and merely reflects a physiologic response to an increased demand on a tissue for its specialized function. However, organelle proliferation can interfere with other cell functions leading to so-called pathologic hypertrophy; this is fairly common in toxicologic pathology. For example, hypertrophy of smooth endoplasmic reticulum (sER) of hepatocytes chronically exposed to phenobarbital or other anticonvulsant drugs (Figure 5.10) can impair other hepatocyte functions such as urea production or bile excretion, leading to hyperammonemia or bilirubinemia, respectively. Hypertrophy of sER is not necessarily pathologic. In investigative toxicologic pathology, treatment of experimental animals with 1-aminobenzotriazole used to inhibit phase I metabolism can lead to nonpathologic hypertrophy of affected hepatocytes secondary to mild sER hypertrophy (Figure 5.11).

Irreversible versus Reversible Cell Injury

Cell injury is any physical or chemical insult that results in the loss of a cell’s capacity to maintain homeostasis, in either a normal or adapted state. In toxicologic pathology, cell injury is often in the context of exposure to a noxious stimulus that prevents the cell from maintaining its physiologic parameters within survivable limits. Defining these limits for an injured cell, that is, detecting the “point of no return,” at the biochemical level is a complex undertaking. However, it is clear that alteration of mitochondrial membrane permeability leading to leakage of the electron transport chain enzyme cytochrome c into the cytosol is a critical step for both necrosis and apoptosis. The leakage of cytochrome c is a nonrecoverable event.

Recognizing whether an injured cell is destined to die as compared to one that will survive can be challenging via light microscopy. There is a time lag between those biochemical events that inevitably lead to cell death and the obvious morphological manifestations of necrosis or apoptosis. With TEM, morphologic changes of irreversible cell injury are generally evident somewhat earlier than with light microscopy. Fortunately, it is rarely necessary for a toxicologic pathologist to be concerned with the potential fate of an individual cell because other cells within the affected tissue will typically manifest the morphologic features of irreversible cell injury.

Reversible cell injury simply indicates that the affected cell has the potential to survive following a noxious insult. A reversibly injured cell may be morphologically recognizable by a variety of changes depending on its phenotype. For example, specialized cells may lose their unique phenotypic structures, such as cilia from injured respiratory epithelium. More generally, reversibly injured cells may exhibit classic morphologic features of what has been termed cell "degeneration." For example, hydropic degeneration refers to a swollen cell with pale cytoplasm attributed to excessive accumulation of fluid resulting from a disruption in water balance. Even reversible cell injury can be fatal to the entire organism if a vital function is impaired or the consequences of cell injury are catastrophic. Examples of this concept include neuronal or neuroglial swelling in the central nervous system leading to respiratory arrest, and cardiac myofiber swelling leading to loss of contractility and altered depolarization, repolarization, or electrical conductance. In contrast, hepatocyte swelling in the liver can be quite marked but, considering the reserve and regenerative capacity of the liver, still have little impact on the animal's viability.

Two classic morphologic features of reversible cell injury are cell swelling and fatty change. Both can progress to cell death.

Cell Swelling

Cell swelling is an early degenerative change that occurs in many types of acute cell injury. It may be a prelude to more drastic changes or may resolve as the cell adapts and repairs the damage.

By light microscopy, cell swelling is characterized by expanded, pale cytoplasm. The cell nucleus and/or adjacent cells may be displaced. Occasionally, cell swelling resulting from reversible cell injury may resemble organelle hyperplasia or hypertrophy. While special histochemical stains or electron microscopy may be necessary to distinguish between these processes, microscopic evaluation of the affected tissue overall is usually sufficient to allow for accurate interpretation. By TEM, cell swelling is usually characterized by dilution of cytoplasmic elements and dispersion of organelles; dilated cisternae of ER may also be evident. Rarely, extreme organelle hyperplasia/hypertrophy of organelles may lead to swelling so that both processes occur simultaneously. As cell swelling progresses, clear spaces or vacuoles may form in the cytoplasm; these usually represent dilated portions of the ER and/or Golgi apparatus. If severe enough, cisternae may rupture and “cytoplasmic lakes” may form. Solubilized or denatured proteins that accumulate in these “lakes” are eosinophilic and appear as so-called hyaline droplets. This type of change is termed “vacuolar degeneration” or “vacuolar change.” Diffuse cytoplasmic swelling with minimal vacuolation is also termed “ballooning degeneration” or “cloudy swelling” (Figure 5.12).

The nucleus of reversibly injured cells is often morphologically normal. However, nuclei of affected cells may undergo chromatin clumping, rarefaction, and peripheral nucleolar migration as an indication of more severe cell injury.

Cell swelling occurs when the cell loses its ability to maintain the balance between cytosolic influx of sodium (Na+) ions and water, and efflux of potassium (K+) ions. Swelling reflects the influx of excessive water as a consequence of ineffective membrane ATPases required to actively exchange Na+ for K+. The optimum osmotic gradient is lost, and water follows Na+ into the cell cytoplasm. The pathophysiology of cell swelling can result from direct damage to these ATP-dependent “pumps,” an inadequate supply of ATP substrate, or an overwhelming influx of Na+ after direct damage to the plasma membrane. Cytoplasmic vacuoles may also form directly from the ER if the Na+/K+ ATPases in the ER membrane are sufficiently functional to import excess Na+ (followed by water) out of the cytoplasm into ER cisternae (Figure 5.13).

The morphologic changes associated with cell swelling are also due to the influx of calcium (Ca++) via the diminished capacity or function of the ATP-dependent Na+/Ca++ exchange pumps. The dissociation of cytoskeletal elements and the loss of intercellular junctions that result from excessively high cytosolic levels of free Ca++ leads to additional loss of normal shape and a tendency for the cell to assume a spherical profile (Figure 5.14).

Cell swelling is not lethal per se but may indicate an early phase of a lethal process. In other words, a lethally injured cell may be fixed at the stage of cell swelling. Alternative interpretations for what appears as cell swelling or vacuolar change by light microscopy include hepatocytes with glycogen accumulation, commonly observed when liver samples are obtained from animals in the fed state. Glycogen is typically stored within the hepatocyte cytosol as aggregates, recognized by TEM as “rosettes.” A large portion of these rosettes dissolve during processing for light microscopy, leaving behind swollen hepatocytes with clear or “feathery” cytoplasm that resembles vacuolar change but is not an indication of cell injury. Partially degraded complex carbohydrates that accumulate within neuronal lysosomes with inherited or acquired lysosomal enzyme deficiency, such as swainsonine toxicosis (locoism) in sheep, can also appear as vacuolar degeneration. In principle, such acquired lysosomal storage diseases are reversible following withdrawal of the toxic etiology. However, resolution may be incomplete in highly specialized cells such as neurons.

Fatty Change

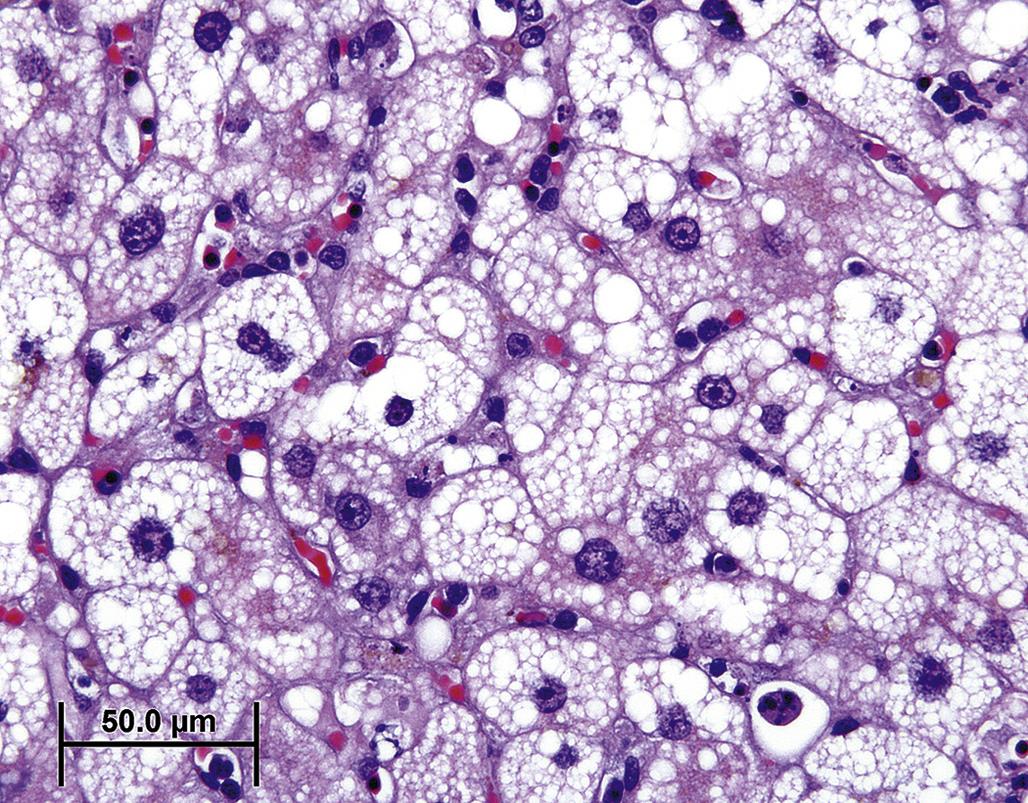

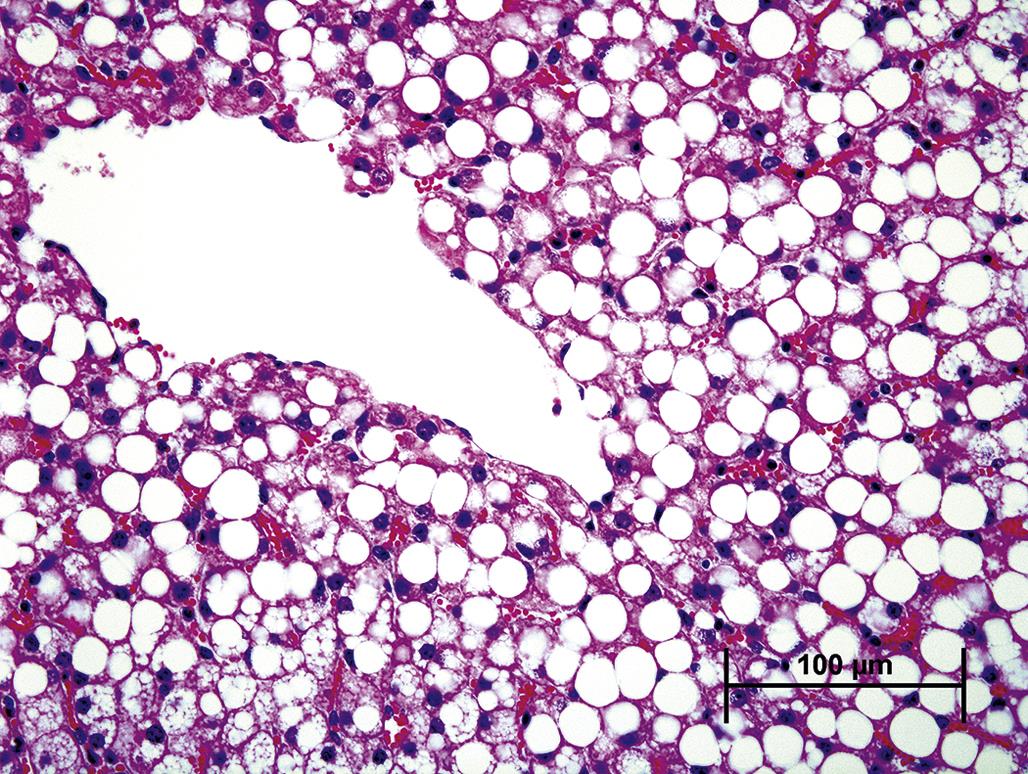

Fatty change, also termed fatty degeneration, lipidosis or “steatosis,” is a second manifestation of reversible cell injury. It occurs in cells that are capable of storing and metabolizing lipid, usually in the form of triglycerides, and is especially common in hepatocytes but also affects myocardial cells and renal tubular epithelium. Whether fatty change represents a degenerative or adaptive change depends on the pathogenesis, although severe fatty change can lead to irreversible cell injury regardless of etiology.

Excessive influx or inadequate efflux of triglycerides will lead to accumulation of lipid droplets throughout the cytoplasm. Mitochondrial dysfunction can lead to insufficient β-oxidation of triglycerides and accumulation of non-metabolized triglycerides, typically adjacent to affected mitochondria. Inadequate protein synthesis secondary to a noxious insult or hypoxia can result in a deficiency of apolipoproteins for lipid transport or oxidative enzymes necessary for β-oxidation of fatty acids; consequently, lipid droplets accumulate within the cytoplasm. Cells with fatty degeneration can be swollen enough to occlude vascular supply. Lipid droplets may be so abundant or large that organelles necessary for normal cell function are compromised.

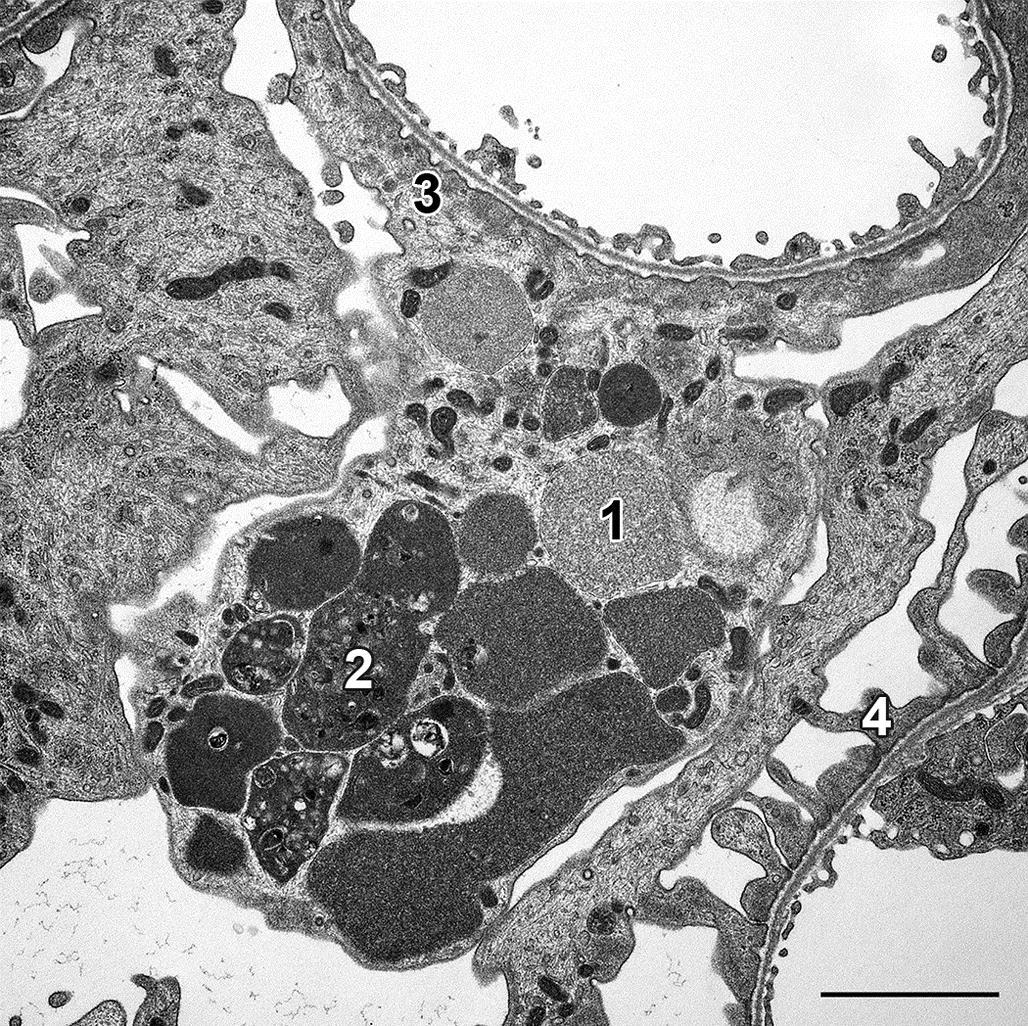

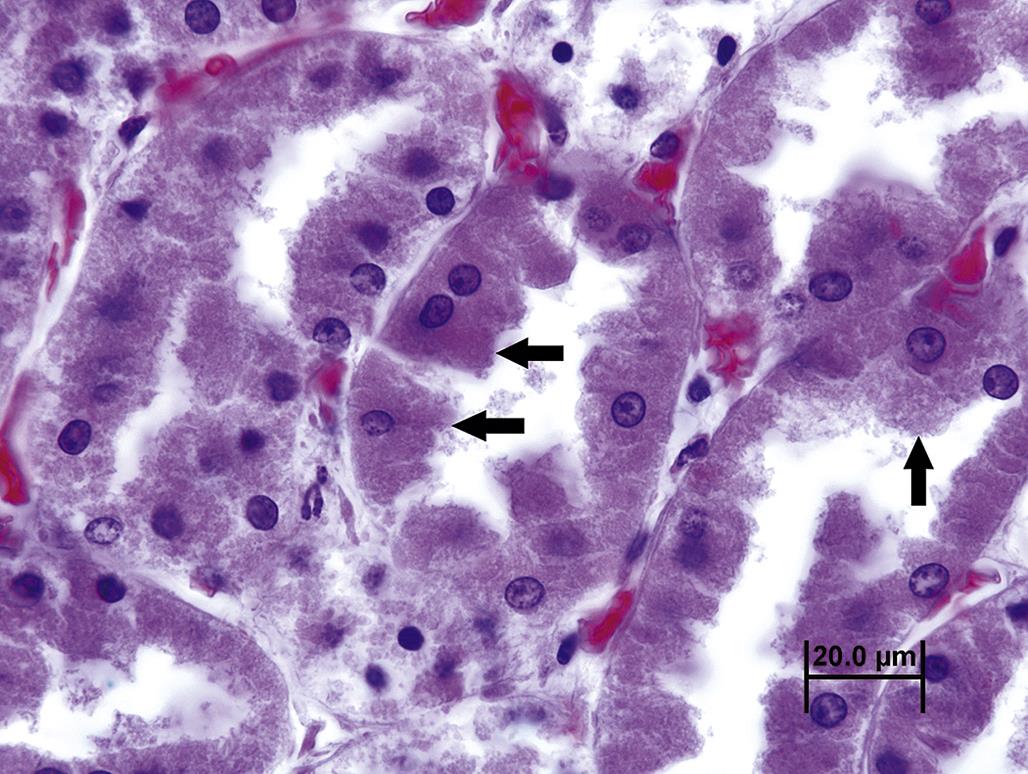

By TEM, fatty change is characterized by accumulation of spherical, often homogenous, cytoplasmic inclusions of varying electron density. These arise from the sER, forming between the inner and outer membrane leaflets. Hence lipid droplets are usually surrounded by a single layer of phospholipids derived from the outer membrane leaflet of the sER (Figure 5.15). Lipid droplets occur in a wide range of sizes. They can be relatively small and dispersed, so-called “microvesicular” lipidosis, which often occurs in the context of an acute insult (Figure 5.16). Lipid droplets can also be quite large, so-called “macrovesicular” lipidosis, occupying almost the entire cell and displacing organelles, including the nucleus, peripherally (Figure 5.17); this type of fatty change typically requires a longer time to develop. Microscopically, cells that have undergone fatty degeneration are swollen with one large to numerous, variably sized, perfectly round, clear spaces compressing the residual cytosol and nucleus to the periphery of the cell. Lipid droplets dissolve when tissue is routinely processed for light microscopy, but are easily recognized. If confirmation of their lipid component is necessary, frozen sections can be stained with Oil Red O (orange droplets), Sudan black (black droplets), or osmium tetroxide (black droplets).

Macroscopically, a fresh liver with fatty change is easily recognized as one of the classic lesions in pathology. It is orange to yellow, evenly reticulated with a distinct lobular pattern, friable, and greasy. Lipidosis in the heart or kidney appears as pale whitish-yellow areas. In the heart, lipidosis may occur in the myocardium bordering an infarct where mitochondrial β-oxidation pathways are impaired. In the kidney, triglycerides may accumulate in renal tubular epithelium in the context of hyperlipidemia with diabetes mellitus. In areas of inflammation involving lipid-rich tissue, macrophages sequester lipids in discrete round vacuoles. A prototypic instance of this is necrosis of infarcted brain or spinal cord tissue, especially white matter, with the recruitment of numerous foamy “gitter cells” to remove the lipid-rich debris (see Chapter 21: Nervous System). While replete foamy macrophages may degenerate and elicit phagocytosis by adjacent macrophages, this type of lipid accumulation is considered a normal cell function and not primary cell injury.

Irreversible Cell Injury

Irreversible cell injury denotes the “point-of-no-return” from which a damaged cell is incapable of recovery and is committed to die. Functionally, this occurs when the physiology of an irreversibly injured cell is disrupted enough that homeostasis cannot be maintained. Once a cell has reached this state, cell death, whether via a passive process, that is, necrosis (or more formally, “oncotic necrosis”), or an active process, that is, apoptosis (more formally, “apoptotic necrosis”), is inevitable. The dead cell ultimately degrades, lyses, and dissolves, or is phagocytized.

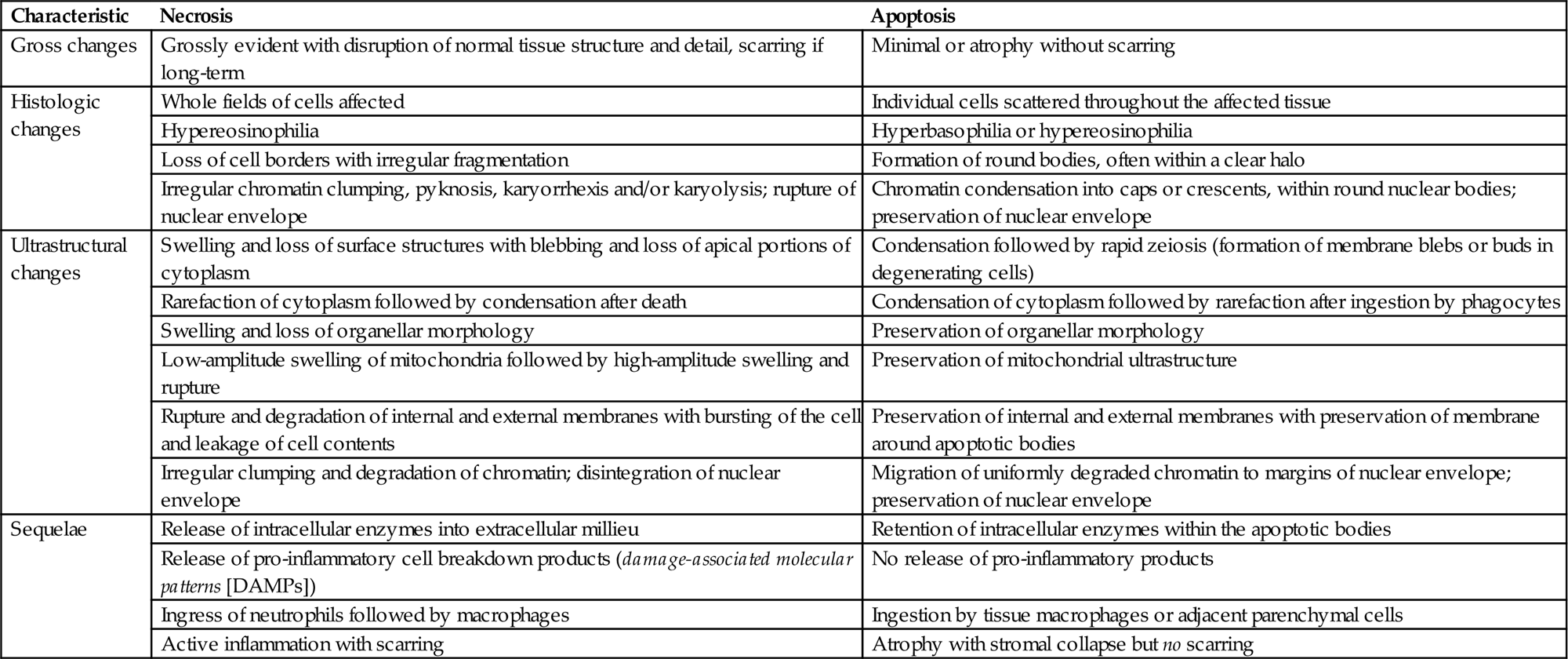

Defining the precise physiologic criteria necessary for a cell to become irreversibly injured is virtually impossible, but an irreversibly injured cell exhibits stereotypical morphologic features that can clearly indicate the lethal aspect of its injury. In some instances, such features reveal the pathogenesis or even etiology of the noxious insult, and these may provide the only clues regarding why the cell was in the process of dying (Table 5.1). The morphologic progression of a dead cell’s breakdown and removal can be termed generically as “necrosis,” regardless of the mechanism of cell death.

Table 5.1

| Characteristic | Necrosis | Apoptosis |

| Gross changes | Grossly evident with disruption of normal tissue structure and detail, scarring if long-term | Minimal or atrophy without scarring |

| Histologic changes | Whole fields of cells affected | Individual cells scattered throughout the affected tissue |

| Hypereosinophilia | Hyperbasophilia or hypereosinophilia | |

| Loss of cell borders with irregular fragmentation | Formation of round bodies, often within a clear halo | |

| Irregular chromatin clumping, pyknosis, karyorrhexis and/or karyolysis; rupture of nuclear envelope | Chromatin condensation into caps or crescents, within round nuclear bodies; preservation of nuclear envelope | |

| Ultrastructural changes | Swelling and loss of surface structures with blebbing and loss of apical portions of cytoplasm | Condensation followed by rapid zeiosis (formation of membrane blebs or buds in degenerating cells) |

| Rarefaction of cytoplasm followed by condensation after death | Condensation of cytoplasm followed by rarefaction after ingestion by phagocytes | |

| Swelling and loss of organellar morphology | Preservation of organellar morphology | |

| Low-amplitude swelling of mitochondria followed by high-amplitude swelling and rupture | Preservation of mitochondrial ultrastructure | |

| Rupture and degradation of internal and external membranes with bursting of the cell and leakage of cell contents | Preservation of internal and external membranes with preservation of membrane around apoptotic bodies | |

| Irregular clumping and degradation of chromatin; disintegration of nuclear envelope | Migration of uniformly degraded chromatin to margins of nuclear envelope; preservation of nuclear envelope | |

| Sequelae | Release of intracellular enzymes into extracellular millieu | Retention of intracellular enzymes within the apoptotic bodies |

| Release of pro-inflammatory cell breakdown products (damage-associated molecular patterns [DAMPs]) | No release of pro-inflammatory products | |

| Ingress of neutrophils followed by macrophages | Ingestion by tissue macrophages or adjacent parenchymal cells | |

| Active inflammation with scarring | Atrophy with stromal collapse but no scarring |

From Haschek, W.M., Rousseaux, C.G., Wallig, M.A. (Eds.), 2007. Handbook of Toxicologic Pathology, second ed. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, Table 2.1, p. 16.

Generally, the process of post-necrotic cell degradation is also termed degeneration and can be recognized by various gross or light microscopic features after lethal cell injury. Viable tissue surrounding necrotic cells will often exhibit a host reaction, such as hemorrhage or inflammation, which allows a pathologist to distinguish antemortem from postmortem cell death. The latter, also termed autolysis, encompasses many of the end-stage physiologic and some of the morphologic manifestations of antemortem cell death. Importantly, autolysis affects large contiguous portions of whole organs, while necrosis typically affects distinct areas. Autolysis proceeds at different rates depending on internal and external factors. For example, autolysis of intestinal mucosa is rapid because bacteria are already present and abdominal viscera retain their warmth after death. In contrast, autolysis of the brain may be quite slow, especially if the ambient temperature is low, since heat rapidly dissipates from the skull.

Necrosis

Ultrastructural features of necrosis mimic some of those characteristic of reversible cell injury, including cytoplasmic swelling and rarefaction of the cytosol, dilation of the ER or formation of cytoplasmic lakes, loss or deformation of specialized structures such as microvilli, and/or dissociation from adjacent cells or the extracellular matrix (ECM). Subcellular changes of lethal cell injury may be evident hours before they are recognizable histologically.

Plasma membrane alterations are an early indication of lethal injury. These include loss of microvilli and cilia (Figure 5.18) and disruption of intercellular junctions (e.g., gap junctions separate, the maculae densae and zonulae adherentes degrade, and the terminal cytoskeletal web dissolves). As the cell swells and the intricate substructure of the plasma membrane is disturbed, cytoplasmic “blebs” or “out-pouchings” may form on the surfaces of lethally injured cells (Figure 5.19). Such cytoplasmic fragments may detach from the bulging surface of the swollen cell and slough into an adjacent lumen or interstitial space, where they eventually lyse and release their contents, which include lytic enzymes and pro-inflammatory chemicals.

The aforementioned pro-inflammatory chemicals include damage-associated molecular pattern molecules (DAMPs), which trigger inflammatory and immunologic responses, but these are generally mild in comparison to the responses invoked by an infectious agent (discussed later). DAMPs include both proteins and non-protein substances that are normally sequestered within a viable cell or as part of the ECM. Intracellular DAMP proteins include heat shock proteins (HSPs), S-100, and the chromatin-associated protein high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1). Non-protein DAMPs include ATP, adenosine, uric acid, and DNA itself. ECM-derived DAMPs include hyaluronan fragments and heparan sulfate.

Lethal cell injury commonly leads to cell swelling with disruption of plasma membrane integrity. Cell swelling often reflects loss of energy-dependent, membrane-bound ion exchange proteins, but it also may reflect enzymatic digestion of the plasma membrane by phospholipases activated by uncontrolled Ca+2 influx. Other causes of plasma membrane injury include free radicals generated by dysfunctional mitochondria and noxious agents that are directly toxic to plasma membrane phospholipids (Figure 5.19). By TEM, portions of partially degraded, bilayered plasma membrane characteristically roll into laminated myelin whorls (Figure 5.9).

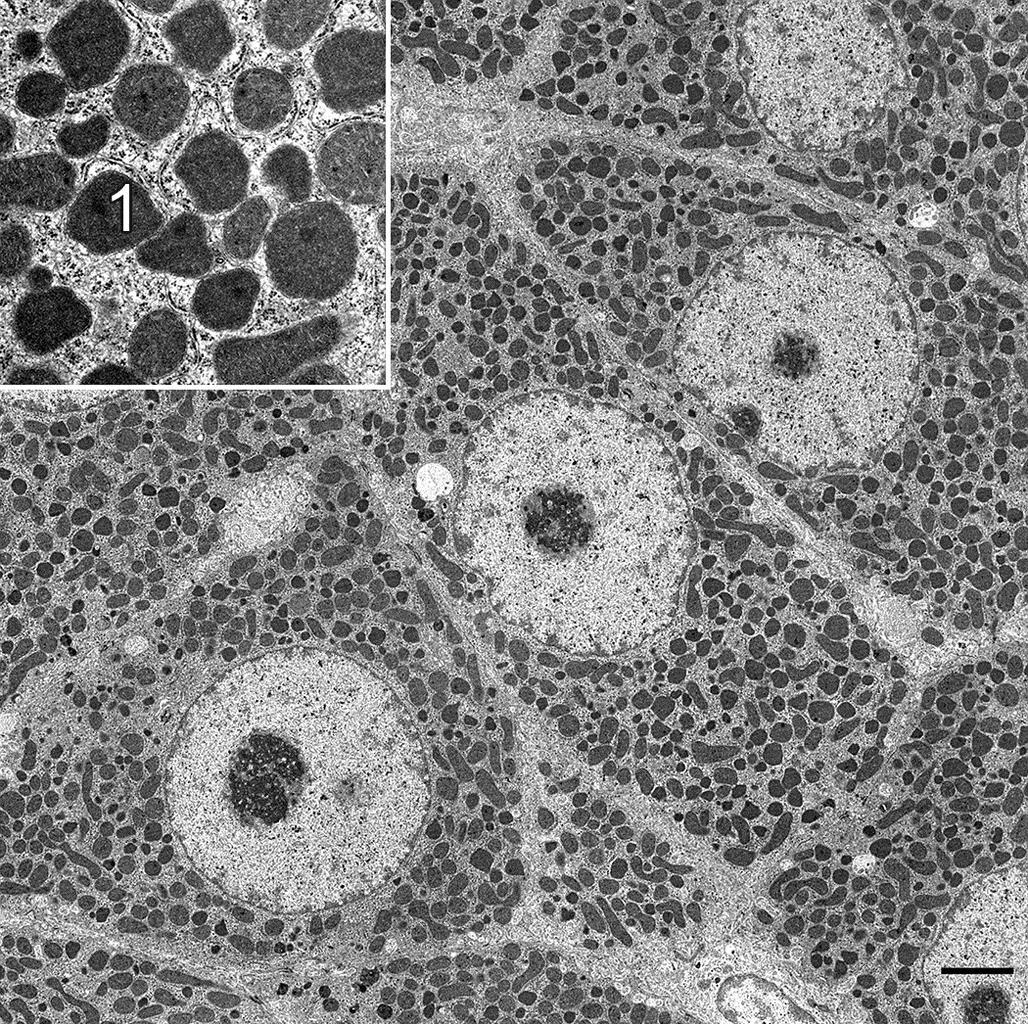

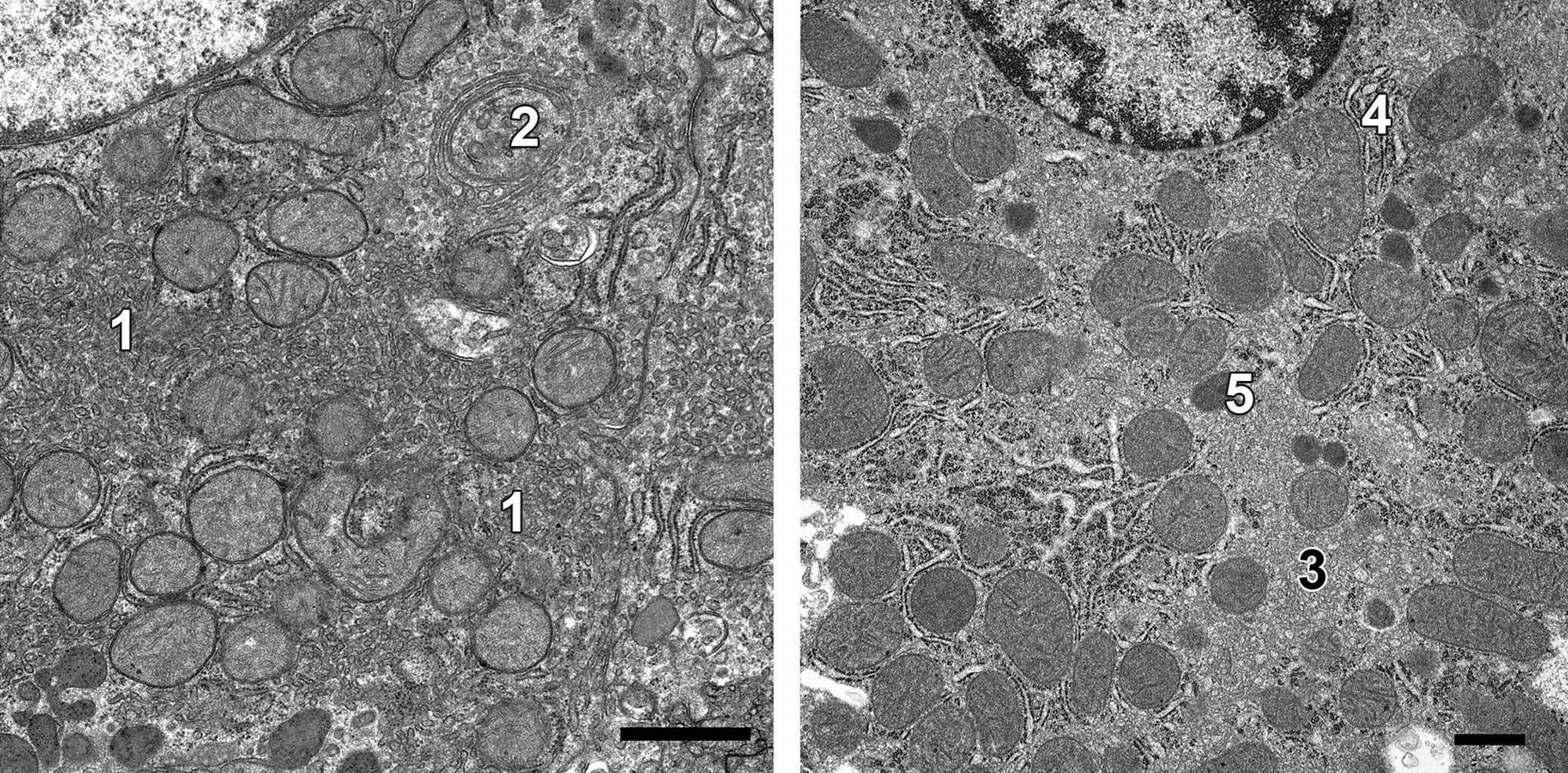

Mitochondria exhibit a variety of dramatic morphologic changes during the process of necrosis. These organelles first undergo a form of distension termed “low-amplitude” swelling, which develops as ATP production diminishes and ATP-dependent ion pumps in the mitochondrial outer membrane become incapable of maintaining water balance. Low-amplitude swelling refers to expansion of the outer mitochondrial compartment as water and electrolytes flow from the inner compartment and sequester in the intermembranous space. Concurrently, the inner mitochondrial compartment condenses, becoming electron-dense when observed by TEM. This state is recoverable if the noxious insult halts. With persistent injury, electron-dense calcium phosphate deposits form as Ca+2 homeostatic mechanisms fail, and over time these enlarge to form “flocculent densities” composed of partially degraded protein and membrane elements.

“High-amplitude” mitochondrial swelling is an indication that the necrotic processes have progressed to the “point-of-no-return.” It is characterized by massive swelling of both inner and outer compartments, loss of cristae (cristolysis), and accumulation of precipitated mineral and protein (Figure 5.19). As the inner mitochondrial compartment expands to contact the outer compartment, an irreversible state termed mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) ensues. Once MTP begins, ATP-generating particles on the inner mitochondrial membrane detach, ATP production ceases, and molecules of adenine nucleotide transporter (ANT) are released. ANT binds to the mitochondrial matrix protein cyclophilin D. This complex binds to an outer membrane ion transport protein, the voltage-dependent anion channel, forming the MPT pore, which allows the passage of small molecules between the cytosol and the mitochondrial matrix. At this stage, Ca+2 salt precipitates are especially prominent, especially when vascular perfusion replenishes interstitial fluid Ca+2 and phosphate into the extracellular interstitial fluid surrounding the injured cells. With MPT pore formation, the mitochondrial outer membrane ruptures, and the mitochondrion is no longer viable. For most cell types, necrosis quickly follows complete depletion of energy storage and production.

Coincident with the morphologic and functional deterioration of mitochondria that portends imminent necrosis, water continues to accumulate in the cytoplasm. Distension of the rough and smooth ER may reflect a temporary accommodation for the excess fluid; however, ER fragmentation typically ensues as ribosomes detach from the rough ER and adaptive protein synthesis ceases. Recovery is now impossible. Once organelle membranes rupture, releasing lysosomal enzymes, degradation of cellular components accelerates, leaving condensed cellular remnants. The sequence of cell swelling followed by condensation is characteristic of necrosis. In contrast, cell death by apoptosis is characterized initially by condensation followed by fragmentation and ingestion by adjacent phagocytes.

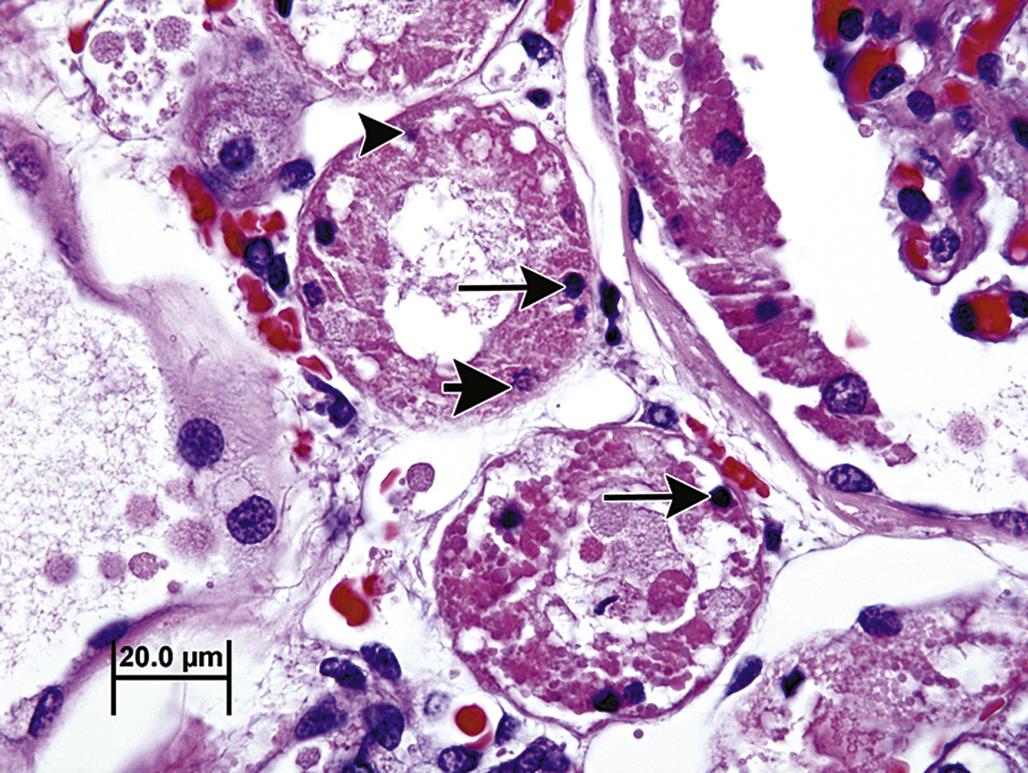

In the cell nucleus, morphologic changes of irreversible cell injury are manifested mainly by changes in chromatin and the nuclear membrane. Chromatin clumps along the nuclear membrane so that the distinction between light-staining euchromatin (i.e., the regions with more active gene transcription) and dark-staining heterochromatin are lost. This is considered a consequence of decreasing nuclear pH that occurs during the process of necrosis. The nuclear membrane pores break down, severing normal connections between the nucleus and the ER cytocavitary network. After the nuclear membrane ruptures, the nucleus typically shrinks and condenses, a morphologic hallmark of necrosis termed pyknosis, while the swollen cytosol and enlarged perinuclear space impinge on the nucleus (Figure 5.20). Eventually the nuclear membrane breaks down completely, leading to rarefaction of the remaining nucleoplasm and dispersion of the aggregated bits of degraded chromatin while attached to plasma membrane fragments; this change is another morphologic hallmark of necrosis, termed karyorrhexis (Figure 5.20). Eventually all the chromatin, nucleoplasm, and nuclear membrane are completely degraded, a change that is termed karyolysis (Figure 5.20).

Once an irreversibly injured cell is no longer physiologically active, lysosomes swell, their membranes leak, and their enzymes are released into the cytosol, triggering a process termed autolysis. Because lysosomal enzymes require sequestration to prevent their leakage into a viable cell’s cytoplasm, lysosomal membranes are relatively resilient to noxious stimuli, so that their constituent enzymes are typically released into the cytosol quite late in the process of necrosis. However, there are a few examples of primary lysosomal damage leading to cell injury. For example, hepatotoxicity occurs when excessive amounts of copper accumulate in hepatocyte lysosomes, predisposing them to increased lysosomal membrane permeability. Release of enzymes and highly oxidative cupric cations into the cytosol then leads to uncontrolled degradation of cell constituents.

When degradation of cell components by lysosomal enzymes nears completion, the cell is clearly recognizable by light microscopy as necrotic (Table 5.1). The morphology of necrosis is quite stereotypical, although features do vary depending on biochemical, functional, or structural traits specific to the particular cell, tissue, or organ. Most necrotic cells are characterized by diffusely hypereosinophilic cytoplasm as a consequence of coagulated proteins. The cytoplasm may become “glassy” in appearance, that is, hyalinized, as reactive peptides released from degrading proteins bind to eosin. Eosinophilia is also enhanced by the loss of normally hematoxylin-staining, that is, basophilic, nucleic acids, such as ribosomal RNA. Cytoplasmic granules, representing mitochondria laden with Ca+2 deposits, may also be observed by light microscopy. As the degradation of a necrotic cell progresses, its cytoplasm becomes “moth-eaten” and fragmented. In tissues with a large influx of Ca+2, a necrotic cell’s cytoplasm may calcify, or mineralize, yielding a strong basophilic, stippled, fragmented, or even crystalline appearance (Figure 5.21). The morphologic progression of necrosis as manifested in the injured cell cytoplasm and nucleus does not necessarily occur in a predictable sequence, so several permutations are possible. Viable tissue adjacent to necrotic cells typically reacts to the injury with an inflammatory response.

The macroscopic, that is, gross, characteristics of necrotic tissue are almost as diverse as the number of specialized tissues. The nature of the lethal injury and the reaction of surrounding viable tissues to the lethal injury can complicate the gross pathology further. Necrotic tissue is often pale, friable, and shrunken, especially if its blood supply was lost antemortem. If blood supply was maintained, necrotic tissue may become swollen, soft, and dark as a consequence of dilated vasculature and exuded blood-derived fluid. A clear indication of antemortem necrosis is a discrete area of pallor demarcated by a dark-red rim, which represents hemorrhage and congestion often with some degree of inflammation in response to the core of necrotic tissue.

Necrotic tissue can be classified based on gross and histologic characteristics. Coagulation, or coagulative, necrosis refers to necrotic tissue that has retained its basic structural features. The necrotic tissue remains discernable by light microscopy; necrotic cells are distinct and lightly eosinophilic but lack detail so that they appear ghost- or shadow-like. “Coagulation” necrosis is generally acute and, therefore, is seen with many toxicities. Cells with few lysosomes may be prone to coagulation necrosis because they lack a primary source for enzymes that accelerate the degradative process. The inflammatory response in viable tissue surrounding areas of coagulation necrosis may be somewhat diminished with toxicant-induced injury since the DAMPs required to trigger a more substantial inflammatory response have yet to be released in abundant quantities. Pro-inflammatory proteins, such as active complement fragments, and antigen-antibody binding, are also typically not a prominent feature of toxicant-induced injury.

Liquefactive necrosis occurs when neutrophils and activated macrophages infiltrate necrotic tissue, adding their extensive lytic enzyme pools to the process of tissue degradation. This is common with several bacterial infections and related to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), molecular motifs—usually of microbial origin—that activate Toll-like receptors on neutrophils and macrophages as well as complement pathways. Activated neutrophils characteristically release their lysosomal enzymes into the extracellular milieu, accelerating tissue digestion and producing a lesion that is typically soft and semiliquefied. Some lipid-rich tissues, particularly the central nervous system, undergo liquefactive necrosis since denatured lipids become greasy or oily. The end result of liquefaction is removal of tissue, leaving a space.

Caseous necrosis is the term used when necrotic tissue has the consistency of dry cheese (i.e., consists of crumbling, amorphous debris). It is most common with infections that release PAMPs. Necrotic tissue is typically pale yellow or light green, sometimes with a white tint, quite soft or pasty, and friable but generally does not spontaneously fall apart.

Apoptosis

Cell death by apoptosis contrasts with cell death by necrosis in a variety of important morphologic and molecular ways, and is a common mechanism of toxicant-induced injury. At a basic morphologic level, apoptosis is characterized by cell condensation and fragmentation, while necrosis is characterized by cell swelling. Apoptosis is a morphologically ordered and mechanistically regulated process. Synonyms for apoptosis include apoptotic necrosis, single cell necrosis, programmed cell death, cell suicide, and necrobiosis. Apoptosis is quite common but tends to be morphologically less conspicuous than necrosis for two reasons: apoptosis is a rapid process, and apoptotic cells are quickly ingested by adjacent parenchymal cells or macrophages; and apoptosis typically affects only a small fraction of a cell population at any one time. Apoptosis has several causes and triggering mechanisms, which progress along generally common biochemical pathways. While generally stereotypical in its morphological evolution, apoptosis is manifested somewhat uniquely in some specialized cells or tissues.

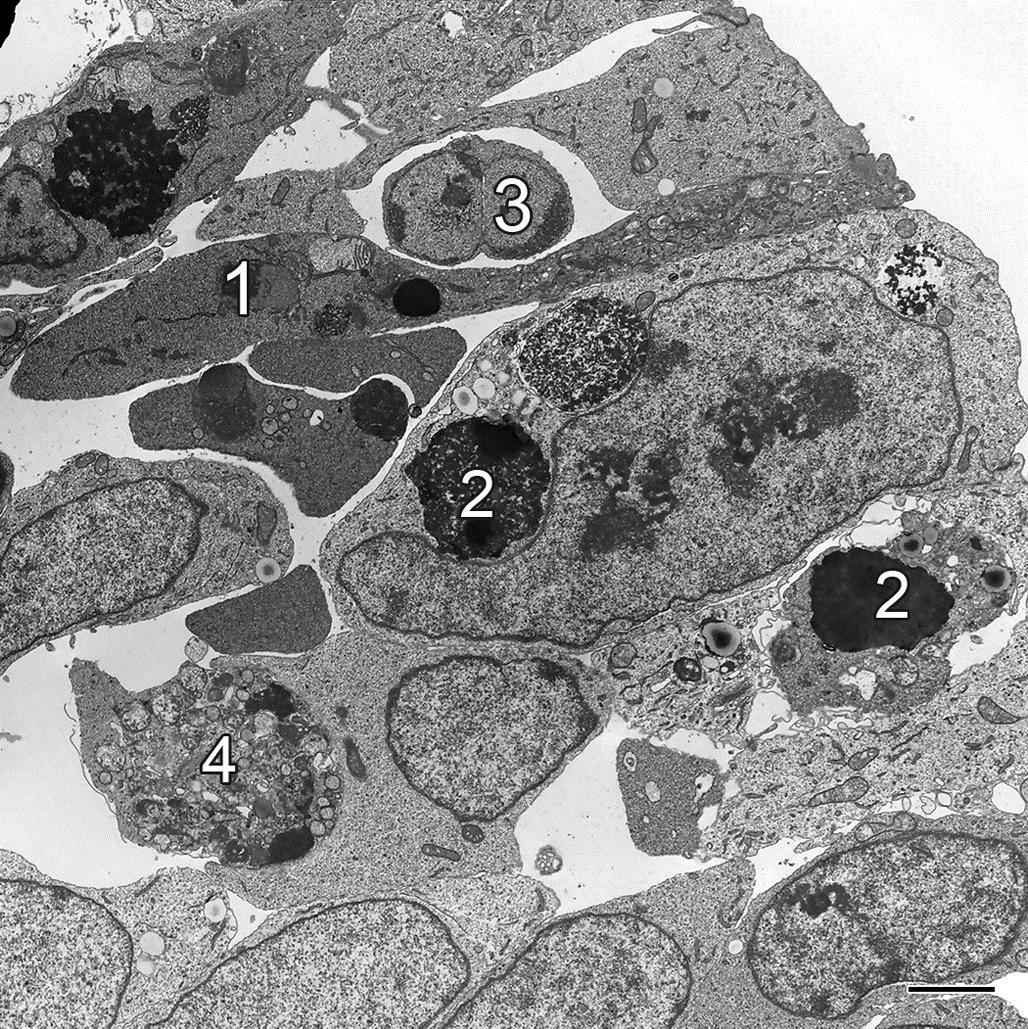

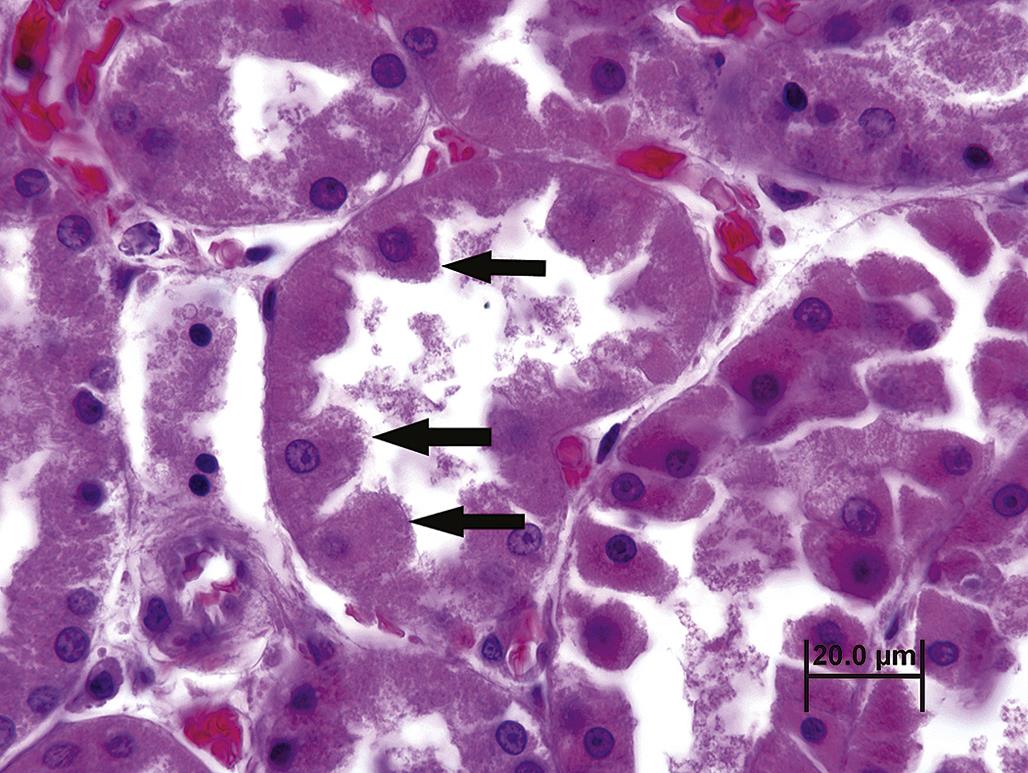

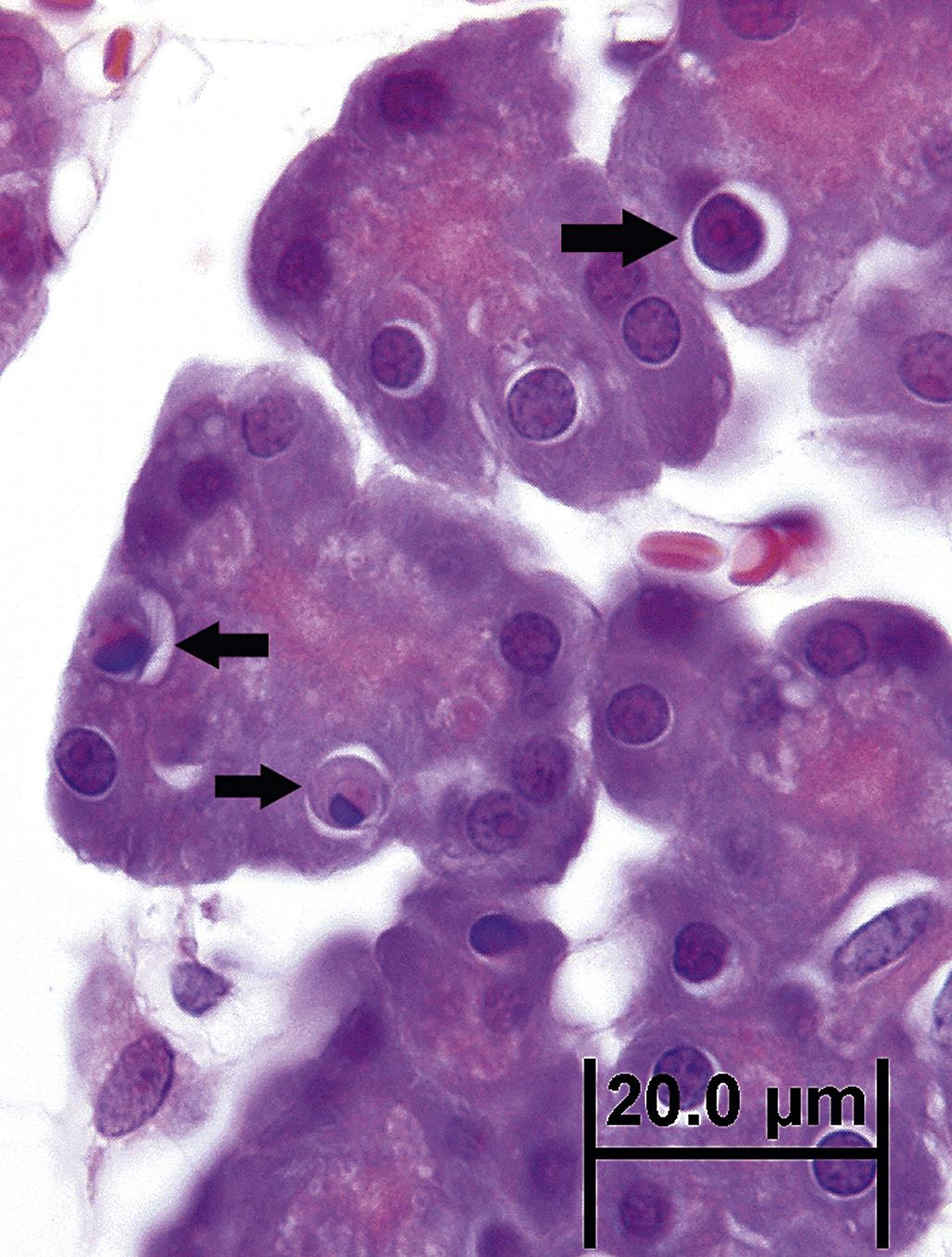

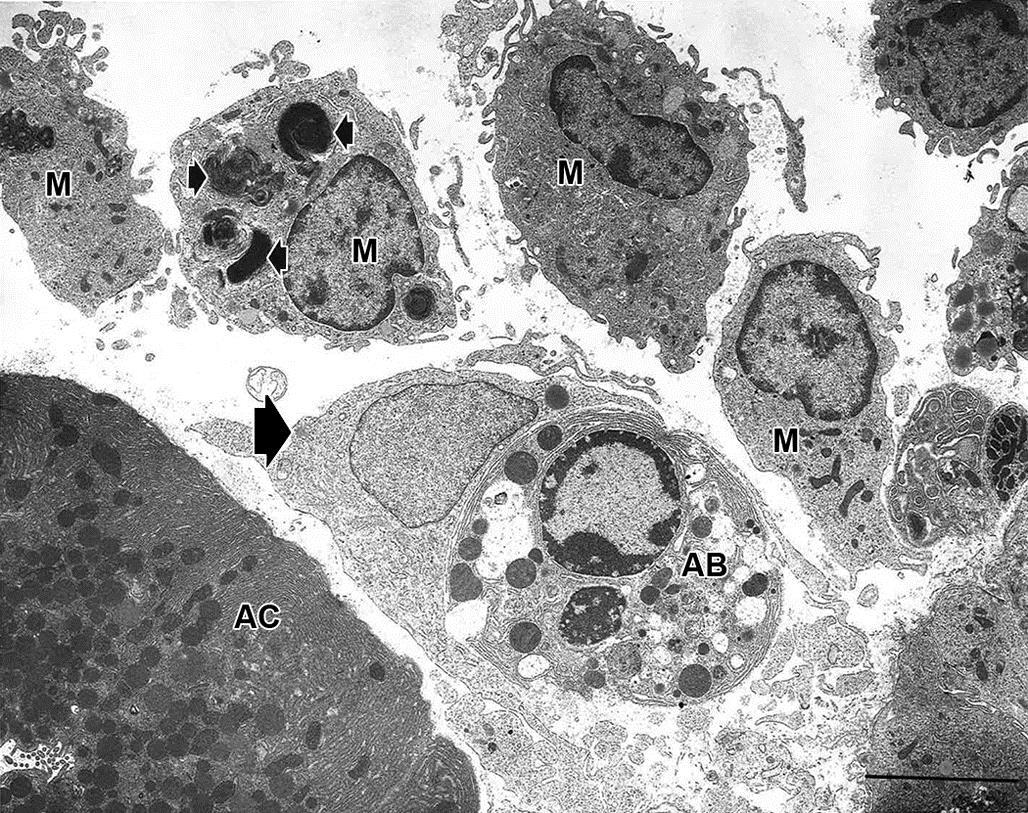

The ultrastructural morphology of apoptosis is quite distinctive and clearly contrasts with necrosis (Table 5.1). Initially a cell undergoing apoptosis detaches from adjacent cells or stroma, and rapidly condenses into spherical body, losing any specialized surface structures. Secretory cells disgorge their storage granules as they condense. Initial dilation of the ER may be observed as Na+ ions and water are pumped into the cisternae prior to condensation of the cytoplasm. As the cytosol condenses, organelles are drawn closer together. Portions of the cell pinch off into spherical, membrane-bound fragments or apoptotic bodies, a process of bleb formation termed zeiosis (Figure 5.22). The integrity of the plasma membrane is generally preserved, even after fragmentation, so organelles such as mitochondria may be visible within detached apoptotic bodies (Figure 5.22). Ribosomes may even remain attached to the rough ER.

Nuclear changes of apoptosis occur before, during or after cytoplasmic changes and zeiosis. While the nuclear envelope is usually preserved, the nucleolus segregates from the chromatin, which uniformly condenses into crescent-shaped or smooth-edged clusters along the nuclear envelope. The nucleus may also undergo zeiosis, forming small, round to oval bodies of densely packed chromatin enveloped by an intact nuclear membrane. After phagocytosis by adjacent cells, apoptotic cells or bodies swell and degrade within phagolysosomes, where their remnants are indistinguishable from those of a necrotic cell.

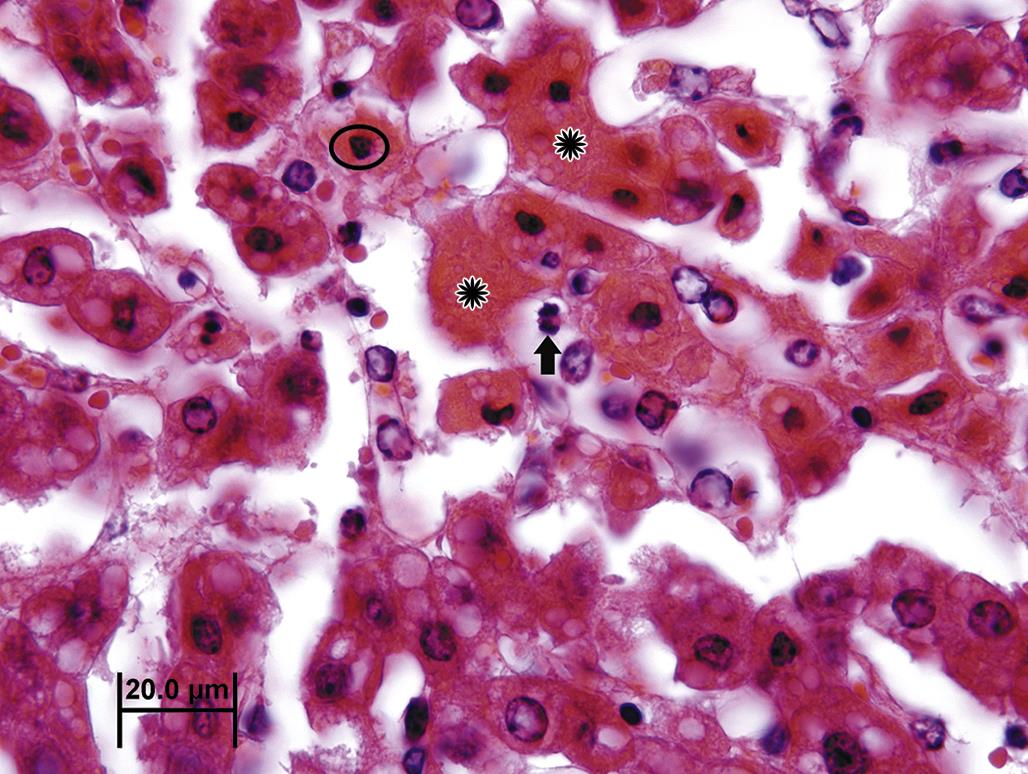

By light microscopy, the morphology of an apoptotic cell is quite distinctive. A key feature is that an apoptotic cell almost always appears isolated, small, spherical, and densely stained. In H&E-stained sections, an apoptotic cell is often demarcated by a thick, clear pericellular halo. Its nuclear remnants are darkly stained by hematoxylin and its cytoplasm by eosin. Apoptotic bodies have clearly defined cell boundaries, reflective of their intact plasma membranes. The surrounding halo may actually be a phagocytic vacuole (Figure 5.23). A particularly characteristic nuclear feature of apoptosis occurs when chromatin condenses as a crescent- or cap-shaped mass along one edge of the nuclear envelope.

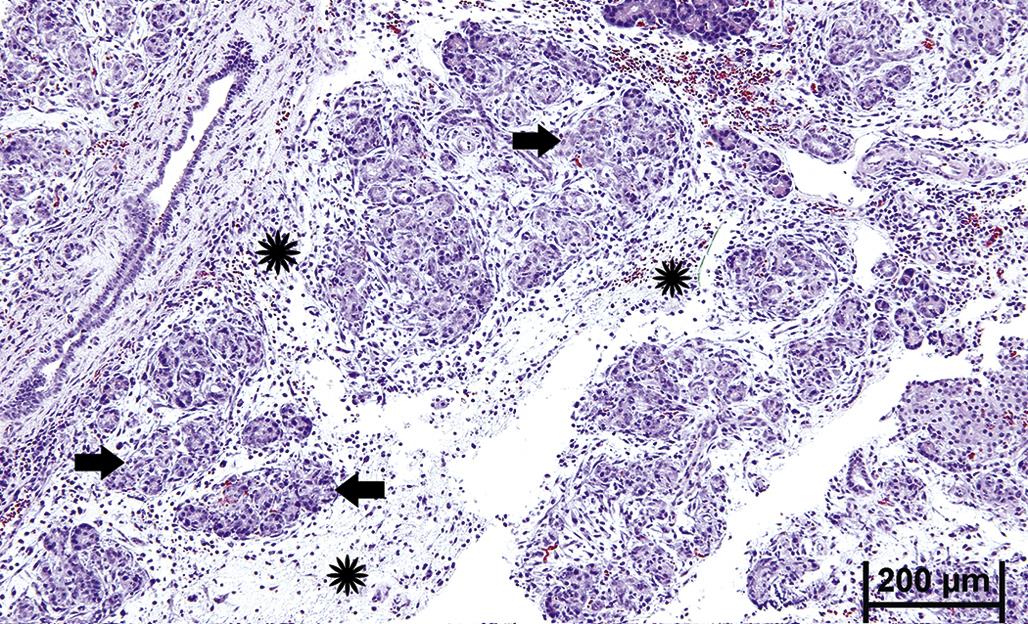

Because the apoptosis is morphologically a rapid process and apoptotic cells are efficiently removed, apoptotic cells are rarely numerous. Even in tissues with toxicologically significant apoptosis, usually only 1%–2% at most of the total cell population are recognizable as apoptotic in any tissue section.

Apoptosis can be triggered by a wide variety of physiologic or toxicologic mechanisms. Injured cells that retain enough function to forestall overt necrosis can be stimulated to undergo apoptosis. The mechanism underlying this form of apoptosis is mediated by caspase 9, reflecting a progressive loss of mitochondrial function, and is referred to as the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis. Examples of this process include oxidative stress with decreased sulfide–disulfide ratios, disrupted ion gradients, or structural damage to proteins on the inner mitochondrial membrane. MPT pores, that is, contact points between the inner and outer mitochondrial membranes, are not a prominent feature of mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis. MPT pores seem to form through dimerization of pro-apoptotic proteins, such as Bax and Bak, from the cytosol and/or outer mitochondrial membrane. These proteins are normally in an inactive, monomeric state docked to the anti-apoptotic protein, Bcl-2, in the outer mitochondrial membrane. As with necrosis, mitochondrial cytochrome c passes through the pores and binds to Apaf-1, a protein that also is “docked” to anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2. The Apaf-1/cytochrome c complex forms a hexamer that binds to pre-caspase 9, also located on the outer mitochondrial membrane, to form the apoptosome leading to activation of caspase 9. This enzyme in turn activates cytosolic caspase 3, the effector protein that serves as the final common “master molecule” for induction of apoptosis.

Another mechanism of apoptosis depends on activation of Fas ligand (FasL), a homodimer which trimerizes with Fas receptor (FasR) to form a “death-inducing signaling complex” (DISC) that spans the cell membrane. This mechanism is termed the extrinsic pathway of apoptosis. Intracellular attachments to DISC include proteins such as Fas-associated protein with death domain (FADD) or tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor type 1-associated death domain protein (TRADD). These are bound to pre-caspase 8. When trimerization of the FasL/FasR complex occurs, pre-caspase 8 is cleaved, releasing active caspase 8 into the cytosol where it also activates caspase 3. Caspase 8 also activates the cytosolic protein Bid to tBid, which then binds to Bcl-2, causing it to release bound Bax and/or Bak, which dimerize and form MPT pores. Therefore, although the FasL mechanism of apoptosis is initiated outside mitochondria, mitochondria are critical in completing the process.

Although not completely understood, another apoptotic mechanism of toxicologic relevance is initiated by activation of caspase 12, when the severity of ER stress exceeds the injured cell’s adaptive capacity, for example, through NFκB activation. ER stress is manifested by accumulation of misfolded or unfolded proteins within cisternae with subsequent induction of “sensor” proteins, release of Ca+2, and activation of pre-caspase 12 on the cytosolic side of the ER. Caspase 12 then activates caspase 3, leading to apoptosis.

Activated caspase 3 initiates a variety of downstream events that mediate the morphological changes of apoptosis. These include promoting degradation of the cytoskeleton via cleavage of β-catenin, fodrin, actin, lamin, and gel-solin, and inactivating several cell cycle pathways such as protein kinase b/Akt. Caspase 3 also activates pro-apoptotic proteins such as scramblase, which promotes eversion of phosphatidylserine (PS) from the inner plasma membrane leaflet to the outer leaflet.

Caspase 3 regulates the fate of the genome during apoptosis via caspase-activated DNase, an endonuclease that cleaves DNA into 180 base pair units. It also inactivates certain key enzymes involved in DNA repair, for example, Poly[ADP-ribose] polymerase 1 (PARP-1), DNA phosphokinase C, and topoisomerases I and II. Indirectly, histones are released from the nucleosome, further exposing DNA to degradation. In this way, caspase 3 is also linked to p53-initiated apoptosis when toxicant-induced injury to the genome overwhelms DNA repair mechanisms.

As additional molecular mechanisms involved in cell death are discovered, classification schemes and nomenclature are updated. For example, the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death recommends using biochemical and/or signaling pathways rather than morphologic criteria to this end (see Chapter 2: Biochemical and Molecular Basis of Toxicity). Morphologic criteria may no longer be precise enough because only “autophagic” cell death, apoptosis, and necrosis can be recognized regardless of which of many mechanisms of cell death may be responsible. However, since several biochemical mechanisms of cell death only occur in certain cell types or only have been described in vitro, whether new classifications are fully accepted by the community of pathologists ultimately will depend on their translational relevance to toxicant-induced cell injury in vivo. For now, morphologic criteria, as well characterized by conventional light and electron microscopy, remain the mainstay for toxicologic pathologists (see Elmore et al., 2016).

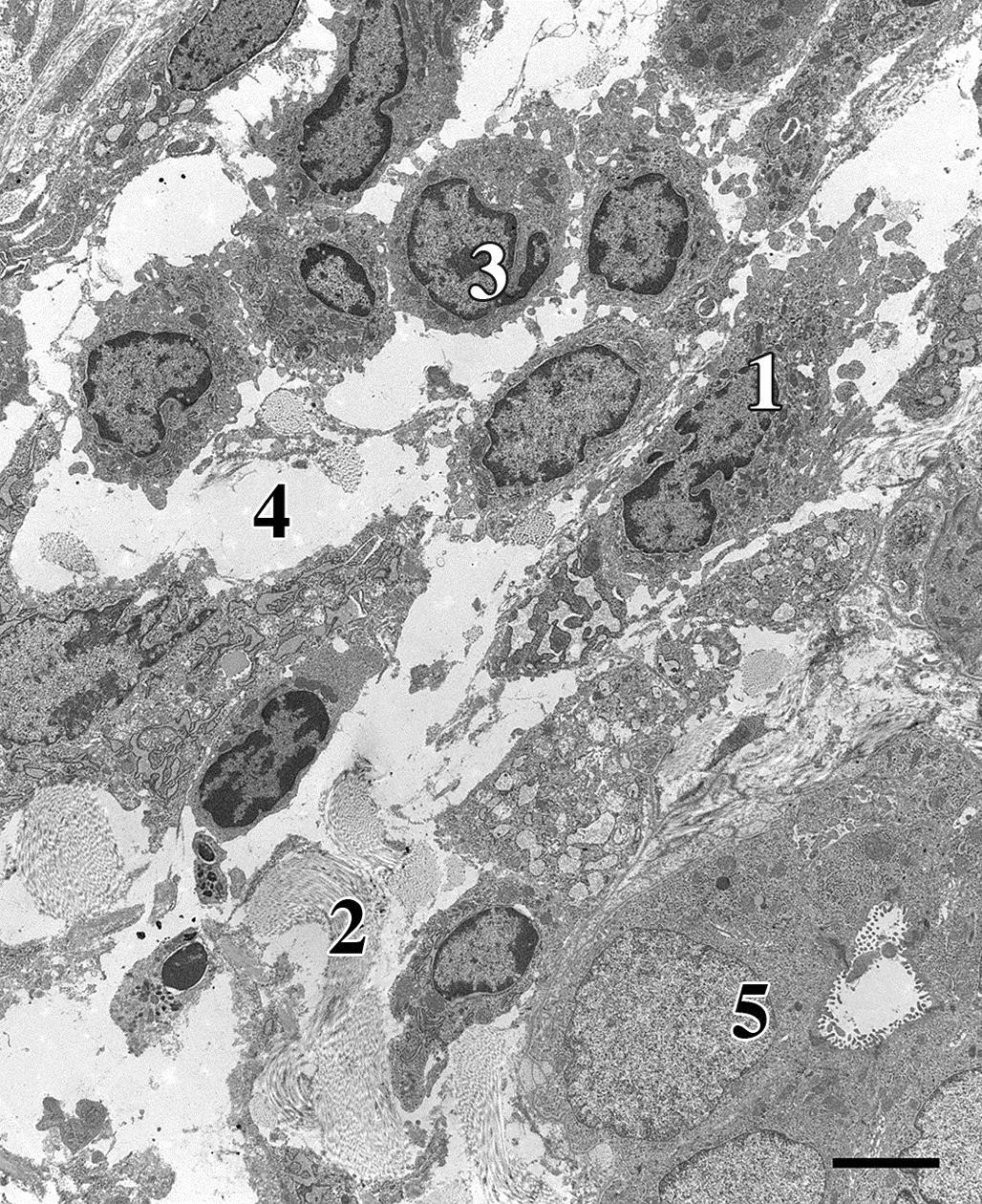

Toxicant-induced injury to a tissue rarely leads exclusively to apoptosis or necrosis. Instead, these two manifestations of irreversible cell injury commonly occur simultaneously. Less severely injured cells, such as those that maintain the functional elements necessary to complete the apoptotic process because they are exposed to a lower dose of the toxicant or are closer to an intact blood supply near the edge of a lesion, tend to undergo apoptosis. Examples of required functional elements that might allow this to happen include sufficient ATP, glutathione, and Ca+2 regulation necessary for caspase activity. In contrast, more severely injured cells or those less capable of maintaining these functional elements tend to lose osmoregulation and proceed to non-caspase-mediated cell death, that is, necrosis. Therefore, toxicant-induced lesions manifested by irreversible cell injury can present with apoptotic cells near the outer limits of a larger focus of overt necrosis, particularly in the liver.

Consequences of Irreversible Cell Injury

Necrosis

In most instances, necrosis elicits an inflammatory response, the extent and nature of which depend on variety of factors, the most obvious being the time elapsed between the initial injury and the actual pathologic evaluation. For example, inflammation will not be observed in the heart when sudden death results from acute myocardial infarction. Alternatively, when death occurs several days after the infarct, an inflammatory response is often quite elaborate.

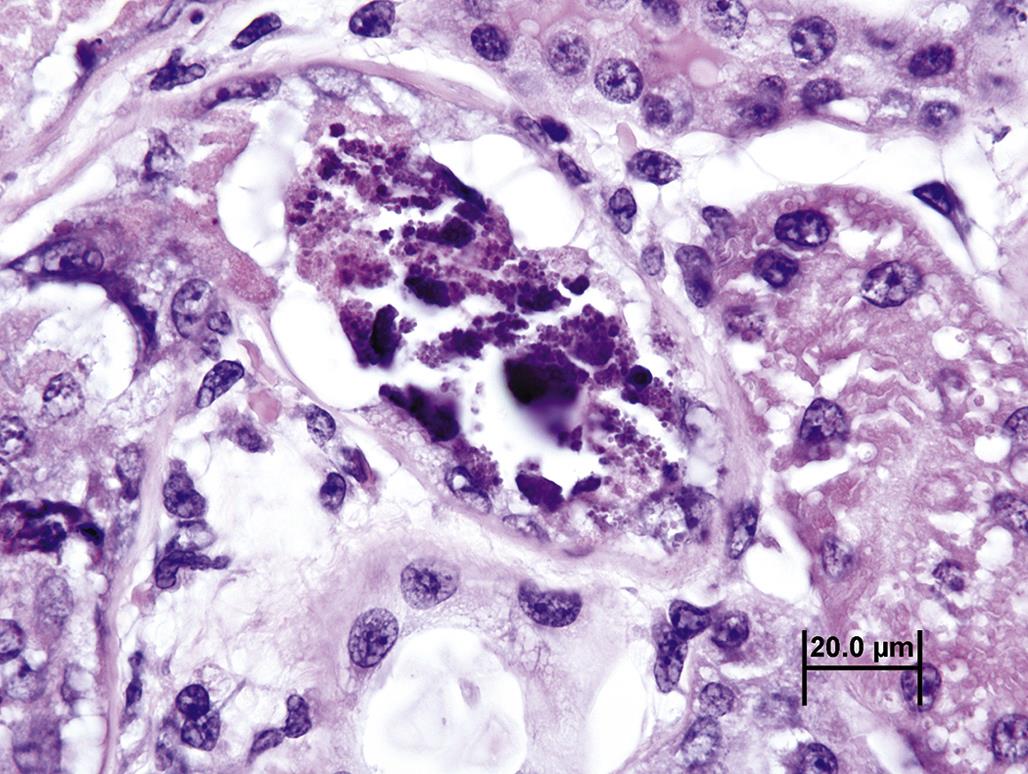

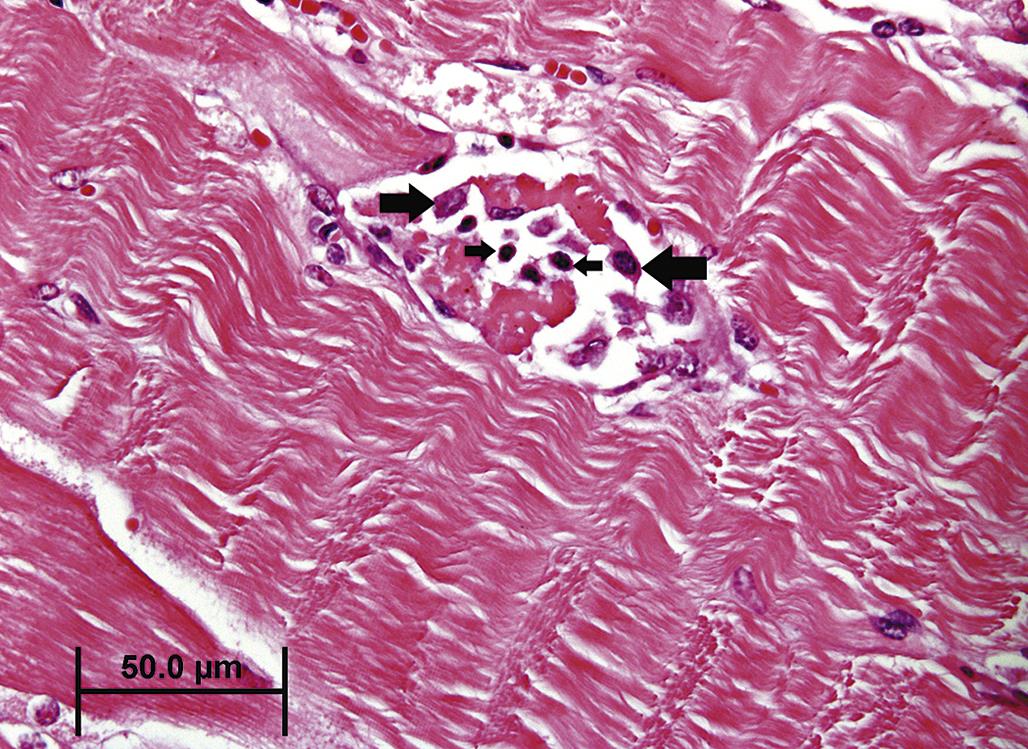

Neutrophils are generally the first inflammatory cell type to infiltrate an area of necrosis. Macrophages, from differentiated blood-derived monocytes and resident precursors, typically predominate within a few days (Figure 5.24). Neutrophils play a critical role in the progressive morphogenesis of a necrotic lesion since their release of lysosomal enzymes into the ECM during phagocytosis of necrotic cell remnants often results in indiscriminate degradation of stroma and lysis of viable “innocent bystander” cells, including neutrophils themselves. This process can exacerbate the severity of the initial parenchymal tissue injury. Neutrophils also produce soluble mediators of inflammation, for example, cytokines that attract more neutrophils, and eventually macrophages, to the site of injury.

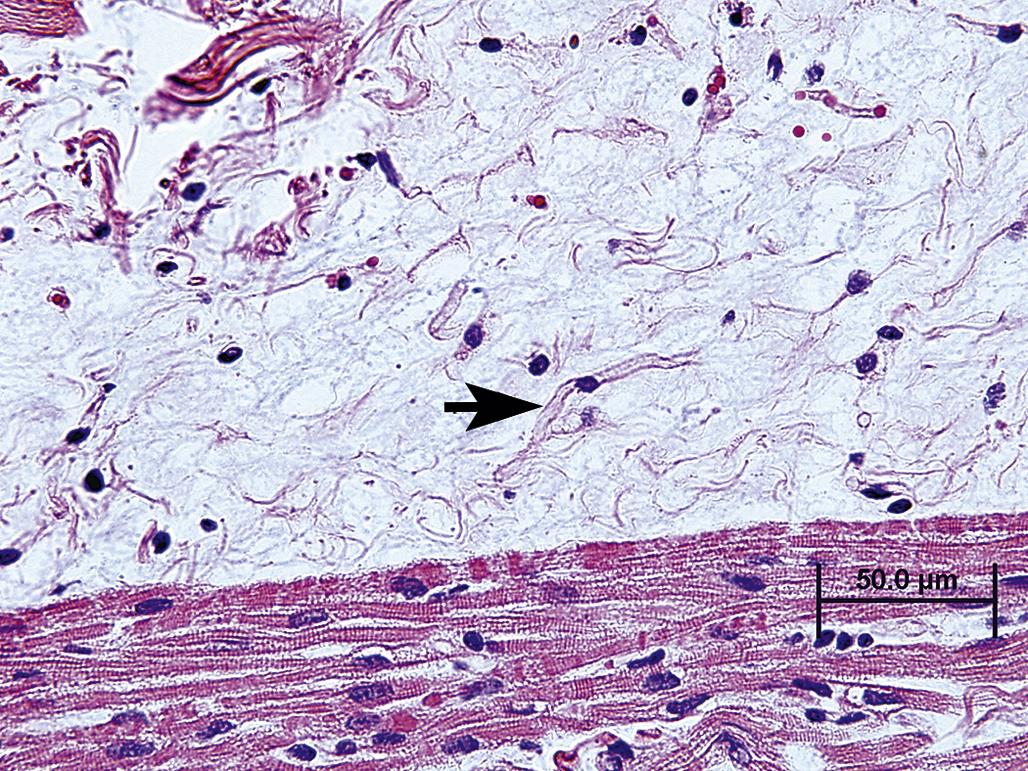

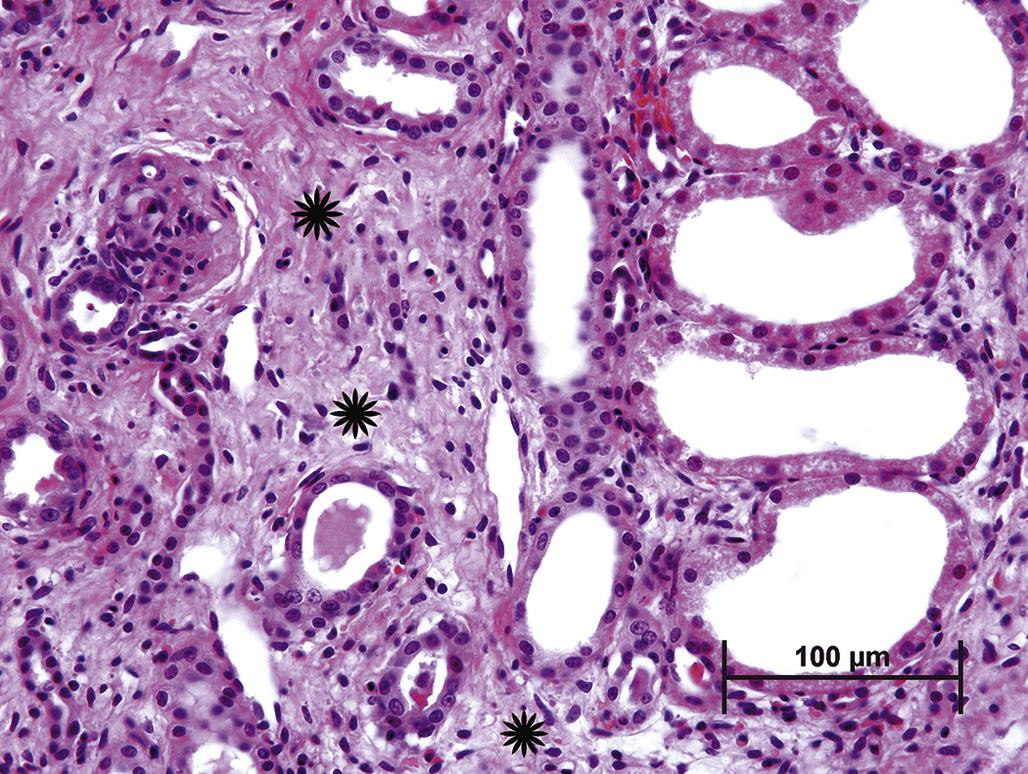

In many organs, extensive tissue damage that cannot be repaired by parenchymal regeneration stimulates fibrosis, for example, scar formation, a process characterized by replacement of lost tissue with nonfunctional stroma. In contrast to normal supporting stroma, which comprises Type IV collagen, elastin, and laminin, fibrotic tissue is predominantly of Type I collagen, which is generally resistant to restoration of functional parenchyma (Figure 5.25). Extensive fibrosis leads to permanent loss of function in the affected tissue. In some organs, such as the liver or kidney, a substantial reserve capacity provides a buffer between multifocal fibrosis and organ failure, but progressive or recurring injury eventually erodes this capacity.

The specialized function and structure of some organs dictates the nature of an inflammatory response to a toxic injury. For example, necrotic pancreatic acinar cells release proteases, which stimulate a dramatic influx of neutrophils. A vicious cycle can ensue, with neutrophils inciting further acinar cell necrosis so that a localized lesion can rapidly progress to an extensive one. The inflammatory response also depends on the extent of the initial tissue damage and the degree of tissue vascularization. For example, a large renal infarct typically elicits a more intense inflammatory response than a lesion localized to only part of one nephron. Injury to well vascularized tissue, such as the pulmonary parenchyma, often elicits a stronger inflammatory cell infiltrate than does damage to a poorly vascularized tissue, such as articular cartilage. However, a better blood supply can also lead to faster and more complete tissue repair.

When supporting stroma is retained following tissue injury, the inflammatory response tends to be muted. For example, inflammation subsequent to gastric erosion (i.e., loss of part or all of the mucosa) is generally less intense than is the response to a gastric ulcer (i.e, a full thickness penetration of the wall), and the latter is more likely to result in a scar.

Secondary or opportunistic infections can complicate the inflammatory response to a toxicant-induced lesion. Bacteria are an additional source of toxins and PAMPs that cause further cell injury, inhibit regeneration, and attract more inflammatory cells, especially neutrophils. Those tissues with a so-called barrier function, such as the skin and gastrointestinal tract, are at particular risk for opportunistic bacterial infections following a toxic insult. Hematogenous dissemination of bacteria from the damaged intestinal mucosa can lead to secondary hepatitis or even septicemia.

Complete structural restoration of injured tissue is predicated on viable supporting architectural stroma. For example, following a toxic injury, the basement membrane of an epithelial tissue must remain intact or, if damaged, be adequately resynthesized before the epithelium can effectively regenerate. Typically this type of tissue restoration proceeds from the lateral or deep margins of a resolving necrotic lesion, where vascular ingrowth is initiated. Incomplete restoration of parenchymal tissue, also termed repair, may be evident microscopically as fibrosis for an extended period of time even if the overall organ function is maintained.

The process leading to repair mirrors that of regeneration. The initial neutrophil-predominant response is followed by a macrophage-predominant one. Macrophages, derived from circulating monocytes and resident macrophage precursors, scavenge cell debris, including effete neutrophils, and secrete mediators of cell differentiation and migration. These cytokines and chemokines include a variety of growth factors that drive the repair process. Tissue repair in mice depleted of resident macrophages or lacking certain macrophage functions is defective.

The number of macrophage-derived chemokines is enormous. Of particular importance in tissue repair are platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), epithelial growth factor (EGF), fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β). Epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells are also sources of chemokines. Chemokine-mediated activation of fibroblasts at the site of tissue injury temporally coincides with the influx of macrophages, typically within a few days after the initial injury. These fibroblasts produce a matrix rich in fibronectin, hyaluronan, glycosaminoglycans, and Type III collagen, a matrix that serves as a scaffold for fibroblasts and capillary-forming endothelial cells. The matrix is also well hydrated, and therefore conducive to diffusion of oxygen and amino acids. Many fibroblasts express smooth muscle actin and acquire a contractile function. These myofibroblasts promote contraction of tissue undergoing repair, which accelerates lesion resolution but sometimes results in tissue distortion.

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is another important chemokine involved in tissue repair. VEGF is secreted by a variety of cell types under hypoxic conditions and stimulates budding of endothelial cells from intact adjacent capillaries into the area of tissue injury. The purpose of this response is obvious: to reestablish the blood supply required for supplying essential nutrients to regenerating parenchymal cells and proliferating fibroblasts. Provided tissue injury has ceased, endothelial buds form tubular structures that merge with the intact capillary network and interweave with newly deposited collagen fibers. By light microscopy, interwoven neocapillaries and immature collagen fibers present a “basket-weave” pattern, termed granulation tissue (Figure 5.26). Neocapillaries are porous, allowing protein-rich plasma to leak into the well-hydrated ECM. Hence, in life, young granulation tissue is typically pink, somewhat gelatinous, quite friable, and bleeds easily. Granulation tissue is more suited for scar formation than parenchymal cell regeneration, but over time may be partially remodeled so that partial resolution is possible. With type I collagen maturation, cross-linking condensation and reduced vascularization allow tissue contraction to proceed beyond that mediated by myofibroblast function. At this time, the lesion can be recognized grossly as a firm, tough, white scar. This scar tissue serves as a near-permanent barrier to regeneration (i.e., complete parenchymal restoration). For a comprehensive insight regarding how tissue repair versus regeneration occurs in a damaged tissue, refer to Chapter 15: Digestive System.

Apoptosis

In contrast to necrosis, which usually provokes a robust inflammatory response, the tissue response to apoptosis is quite benign. One explanation for this difference is that apoptotic cells do not release quantities of DAMPs sufficient enough to attract inflammatory cells, in particular neutrophils and blood-derived monocytes. Instead, the membranes of the apoptotic bodies are targeted for rapid phagocytosis by adjacent parenchymal cells and resident tissue macrophages (Figures 5.27 and 5.28). The molecular basis for this targeting is complex and appears to depend on a number of factors. Phosphatidylserine (PS) is normally confined to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane by a β-catenin bridge to the actin cytoskeleton. During zeiosis, PS everts to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane. Macrophages loosely bind to externalized PS, along with “immature” glycans, facilitating phagocytosis of apoptotic bodies. Other external macromolecules apparently recognized by macrophages include lysophosphatidyl choline, calreticulin, and annexin. Macrophage receptors, such as LOX-1 and CD61, appear to be necessary for binding to apoptotic cells. Phagocytosis of an apoptotic body after engulfment by a macrophage has been described as a “big gulp” to contrast with the “zipper” type of engulfment that typically precedes phagocytosis of bacteria; the latter is characterized by tight binding of the macrophage membrane to specific ligands on the bacterial membrane. The “big gulp” mode of phagocytosis is thought to involve three signaling pathways: Rac-1, CD91/LRP→hCED/GULP→ABCA, and ELMO.

The precise mechanisms involved in digestion of the apoptotic body are uncertain, but the overall process depends on gradual acidification and protease degradation of the phagosome. Interleukin (IL)-10 synthesis and release by macrophages with engulfed apoptotic bodies partially explain the dampened inflammatory response to apoptosis. IL-10 inhibits synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), IL-2, IL-3, TNF-α, and granulocyte/macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF). The net effect of is to block antigen presentation by those macrophages with engulfed apoptotic bodies. Furthermore, while apoptotic bodies remain in their phagosomes, macrophages have markedly reduced phagocytic capability. In total, phagocyte-derived release of intracellular inflammatory chemokines, those that enhance endothelial permeability and activate or attract neutrophils, is minimal.

Widespread apoptosis within a tissue leads to atrophy (Figure 5.5). Once the cause of apoptosis is addressed, for example, by removing a noxious insult or adding a trophic hormone, full regeneration is usually achievable provided a residual precursor cell population survives. Regeneration potential is particularly high in tissues with constant cell turnover such as lymph nodes, intestinal epithelium, and liver. However, in those tissues with so-called permanent cell populations, such as the retina, significant apoptosis will result in a permanent lesion, retinal atrophy, with some loss of function.

Hyperplasia

As part of the regenerative process subsequent to widespread cell loss, cell proliferation is necessary and often recognizable temporarily as compensatory hyperplasia. However, compensatory hyperplasia can predispose to an ominous molecular event, namely the permanent establishment, that is, fixation, of genetic mutations that can lead to cancer. Hyperplasia in this context is discussed in Chapter 6, Carcinogenesis: Manifestation and Mechanisms. Tissues vary widely in their capacity for compensatory hyperplasia with those composed of so-called labile cell populations most capable followed by those with stable cell populations. Tissues with labile cell populations include lymph nodes and bone marrow; tissues with stable cell populations include lung, liver, and kidney. Retaining precursor cells with the capacity to reenter the active cell cycle as well as adequate stromal and vascular support are prerequisites. Initiation and maintenance of a hyperplastic response among surviving parenchymal cells is mediated at the molecular level by a myriad of protein and small molecule ligands interacting with an array of receptors and downstream signal transduction pathways. Some of these are tissue-specific, such as hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and others are nonselective, such as epidermal growth factor (EGF) and TGF-β. Compensatory hyperplasia can result in peculiar lesions such as hyperplastic nodules with cirrhosis or hyperplastic polyps with chronic colitis. While such proliferative lesions are benign, they can harbor genetic mutations, such as those that may arise from exposure to mutagenic toxicants, and predispose to carcinomas.

Metaplasia

A less common response to tissue injury than hyperplasia, but quite important from a disease perspective, is metaplasia. Metaplasia is generally defined as the replacement of mature fully specialized cells with mature but less specialized cells. It occurs in certain tissues when conditions for complete regeneration are suboptimal, particularly in the context of persistent but relatively limited injury. Classic examples are squamous metaplasia of ciliated bronchial epithelium in response to chronic injury by tobacco smoke and intestinal metaplasia of the esophageal mucosa in response to chronic injury by gastric acid reflux. In both examples, metaplastic cells are more resistant to the inciting injury than are the elements in the normal specialized cell population. Paradoxically, in the bronchus, columnar epithelium is commonly replaced by squamous epithelium, while in the esophagus, squamous epithelium is replaced by goblet cell-rich columnar epithelium. Metaplastic tissue is a stop-gap measure for regeneration, having less functional efficiency than normal tissue. Metaplastic tissue arises in the context of hyperplasia since the new cell type must arise from a precursor cell type and then proliferate. Therefore, metaplastic tissue is also predisposed to neoplastic transformation. In fact, metaplastic tissue is generally more likely to undergo neoplastic transformation than is hyperplastic tissue. This is not surprising since the process of metaplasia requires activation of genes normally suppressed and suppression of genes that are normally active; for example, proto-oncogenes could be newly activated, and tumor suppressor genes newly suppressed. Finally, metaplastic cells may metabolize xenobiotics through substantially different enzymatic pathways than do normal specialized cells. The nature of such metabolites, for example, whether they form protein or DNA adducts, can impact the eventual pathologic outcome of a metaplastic lesion. Metaplasia is further discussed in Chapter 6, Carcinogenesis: Manifestation and Mechanisms.

Clinical Pathology

When a sufficient number of cells in an organ or tissue, such as liver or muscle, are necrotic, specific biomarkers reflecting such damage may be measurable in the plasma or other biofluids. Cytoplasmic blebs released from injured or dying cells can break away and rupture, releasing a variety of cell constituents, such as enzymes, structural proteins, or ribosomal RNA, directly into the blood or interstitial fluid. The identity and quantity of these released constituents often allows a clinical pathologist to determine which organ or tissue is affected, and how severely, while the individual is still alive. In general, during the progression of necrosis, unbound cytosolic enzymes are released earliest, followed by mitochondrial membrane-bound enzymes and finally by lysosomal enzymes. Analysis of isoenzymes may provide exquisite specificity for determining the site of injury. While clinical pathology analyses can provide the sensitivity and even specificity to detect necrosis in certain tissues, the nature of the apoptotic process precludes any widespread usefulness of clinical biomarkers in detecting this process during life. This is understandable considering that apoptotic bodies are rapidly dispatched by adjacent cells, thus minimizing the opportunity for apoptotic cell constituents to reach the interstitial fluid let alone the systemic circulation.

Clinical pathology evaluations can also reflect functional consequences of irreversible cell injury. A classic example is bilateral adrenal cortical necrosis, which may be caused by a variety of toxic and nontoxic injuries. Without the damaged zona glomerulosa, mineralocorticoids are not synthesized, leading to life-threatening hyperkalemia and hyponatremia.

Summary

The morphologic features of an injured cell are complex but generally stereotypical in form and often independent of the etiology. Occasionally, they are distinctive enough to provide an indication of the pathogenesis, particularly when the time course of subcellular changes is known. The terminology used to classify, and subclassify, the stages and manifestations of cell injury is in constant flux as modern molecular techniques are used to correlate morphology, including ultrastructural pathology, with biochemical alterations. This chapter provides a synopsis of concepts in cell injury formulated from observations and experiences (communicated since the early 20th century) that are widely accepted by toxicologic pathologists. No synopsis can be complete because the number of variables, including those that can render injured cells more or less sensitive to noxious stimuli, is impossible to estimate. The succeeding chapters in this book will focus on many of these variables, including those that are dependent on the mechanism of toxicity and on the organ system affected.