In This Chapter

Standing as an art

Standing as an art

Using standing postures to enhance body and mind

Using standing postures to enhance body and mind

Practicing fundamental standing postures

Practicing fundamental standing postures

The simple act of standing upright brings your spine, muscles, tendons, and ligaments into play. Ordinarily, these parts do their assigned tasks quite automatically. But to stand efficiently and elegantly, you also need to bring awareness to the act, and that’s where yoga enters the picture. In this chapter, you can find ten of the most common and favored yoga standing postures to practice. They can help you discover the art of standing consciously, efficiently, and beautifully.

Standing Strong

The yogic standing postures make up the foundation of asana practice. You may hear that you can derive everything you need to master your physical practice from the standing postures. The standing postures help you strengthen your legs and ankles, open your hips and groin, and improve your sense of balance. In turn, you develop the ability to “stand your ground” and “stand at ease,” which are important aspects of the yogic lifestyle. The standing postures are versatile. You can use them in the following ways:

- As a general warm-up for your practice.

- In preparation for a specific group of postures (think of the standing forward bends, for example, as a kind of on-ramp to the seated forward bends, which you can find in Book II, Chapter 7).

- To counterbalance another posture, such as a back bend or side bend. For more information, see Book II, Chapter 7.

- For rest.

- As the main body of your practice.

You can creatively adapt many postures from other groups to a standing position, which you can then use as a learning (or teaching) tool or for therapeutic purposes. Consider, for example, the well-known cobra posture, a back bend that many beginning students find hard on the lower back (see Book II, Chapter 7). By performing this same posture in a standing position near a wall, you can use the changed relationship to gravity, the freedom of not having your hips blocked by the floor, and the pressure of the hands on the wall to free your lower back. Then you can apply this newly won understanding about your back in your practice of the more demanding traditional form of the cobra posture — or any other posture that you choose to modify at the wall. (For more on Yoga against the Wall, head to Book VI, Chapter 2.)

You can creatively adapt many postures from other groups to a standing position, which you can then use as a learning (or teaching) tool or for therapeutic purposes. Consider, for example, the well-known cobra posture, a back bend that many beginning students find hard on the lower back (see Book II, Chapter 7). By performing this same posture in a standing position near a wall, you can use the changed relationship to gravity, the freedom of not having your hips blocked by the floor, and the pressure of the hands on the wall to free your lower back. Then you can apply this newly won understanding about your back in your practice of the more demanding traditional form of the cobra posture — or any other posture that you choose to modify at the wall. (For more on Yoga against the Wall, head to Book VI, Chapter 2.)

Exercising Your Standing Options

This section introduces you to ten standing postures and describes the step-by-step process for each exercise. You can also find discussions on the benefits and the classic (traditionally taught) version of the posture. If you’re a beginner, avoid the classic version because, in most cases, the postures are more difficult and sometimes risky. Here are a few tips before you get started with the standing postures:

- Many of these postures start in the mountain posture, so be sure to check out the “Mountain posture: Tadasana” section.

- When you try the postures on your own, follow the instructions for each exercise carefully, including the breathing. Always move into and out of the posture slowly and pause after the inhalation and exhalation (flip to Book II, Chapter 1 for more on breathing). Complete each posture by relaxing and returning to the starting place.

- When you bend forward from all the standing postures, start with your legs straight (without locking your knees), and then soften, or slightly bend, your knees when you feel the muscles pulling in the back of your legs.

- When you come up out of a standing forward bend, do so in one of these three ways:

- The easiest and safest way is to roll your body up like a rag doll, stacking your vertebrae one on top of the other, with your head coming up last.

- The next level of difficulty is to bring your arms up from the sides like wings as you inhale and raise your back.

- The third and most challenging way is to start with the inhalation and extend your arms forward and up alongside your ears. Then continue raising the upper, middle, and lower back until you’re straight up and your arms are overhead, if possible.

Mountain posture: Tadasana

The mountain posture is the foundation for all the standing postures. Tadasana aligns the body, improves posture and balance, and facilitates breathing.

-

Stand tall but relaxed, with your feet at hip width (down from the sits bones, not the outer curves), and hang your arms at your sides, with your palms turned toward your legs.

The sits bones, also known as the ischial tuberosity, are the bony parts you feel underneath the flesh of your buttocks you when you sit up straight on a firm surface.

-

Visualize a vertical line connecting the opening in your ear, your shoulder joint, and the sides of your hip, knee, and ankle.

Look straight ahead, with your eyes open or closed, as in Figure 3-1.

- Remain in this posture for 6 to 8 breaths.

Note:

In the classic version of this posture, the feet are together and the chin rests on the chest.

Standing forward bend: Uttanasana

The Sanskrit word uttana (pronounced oo-tah-nah) means “extended,” and this posture certainly fits that bill. The standing forward bend (see Figure 3-2) stretches the entire back of the body and decompresses the neck (makes space between the vertebrae), thus freeing the cervical spine and allowing the neck muscles to relax. It also improves overall circulation and has a calming effect on the body and mind. The following steps walk you through the process.

Be careful of all forward bends if you have a disc problem. If you’re unsure, check with your doctor or health professional.

Be careful of all forward bends if you have a disc problem. If you’re unsure, check with your doctor or health professional.

- Start in mountain posture and, as you inhale, raise your arms forward and then up overhead (see Figure 3-2a).

-

As you exhale, bend forward from your hips.

When you feel a pull in the back of your legs, soften your knees (as in the Forgiving Limbs discussion in Book I, Chapter 3) and hang your arms.

-

If your head isn’t close to your knees, bend your knees more.

If you have the flexibility, straighten your knees but keep them soft. Relax your head and neck downward, as Figure 3-2b illustrates.

-

As you inhale, roll up slowly, stacking the bones of your spine one at a time from bottom to top, and then raise your arms overhead.

Rolling is the safest way to come up. If you don’t have back problems, after a few weeks, you may want to try the two more advanced techniques discussed earlier in the section.

- Repeat Steps 1 through 4 three times, and then stay in the folded position (Step 3) for 6 to 8 breaths.

Note:

In the classic posture, the feet are together and the legs are straight. The forehead presses against the shins, and the palms are on the floor.

Half standing forward bend: Ardha uttanasana

The Sanskrit word ardha (pronounced ahrd-ha) means “half.” The half standing forward bend strengthens your legs, back, shoulders, and arms, and improves stamina.

- Start in the mountain posture and, as you inhale, raise your arms forward and then up overhead, as in the standing forward bend (see the preceding section).

- As you exhale, bend forward from your hips; soften your knees and hang your arms.

-

Bend your knees and, as you inhale, raise your torso and arms up from the front so that they’re parallel to the floor, as in Figure 3-3.

If you have any back problems, keep your arms back by your sides; then, over a period of time, gradually stretch them out to the sides like a T and eventually in front of you so they’re parallel to the floor.

-

Bring your head to a neutral position so that your ears are between your arms; look down and a little forward.

To make the posture easier, move your arms back toward your hips instead of having them extend forward or out to the sides — the farther back, the easier.

- Repeat Steps 1 through 4 three times, and then stay in Step 4 for 6 to 8 breaths.

Note:

In the classic version of this posture, the feet are together and the legs and arms are straight.

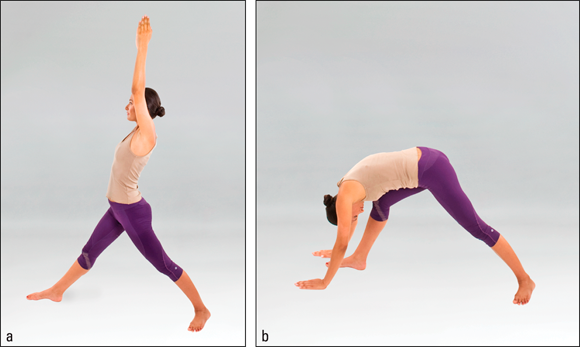

Asymmetrical forward bend: Parshva uttanasana

The asymmetrical forward bend stretches each side of the back and hamstrings separately. The Sanskrit word parshva (pronounced pahr-shvah) means “side” or “flank,” and this posture indeed opens the hips, tones the abdomen, decompresses the neck, improves balance, and increases circulation to the upper torso and head.

-

Stand in the mountain posture and, as you exhale, step forward about 3 to 3½ feet (or the length of one leg) with your right foot.

Your left foot turns out naturally, but if you need more stability, turn it out even more — but not past 45 degrees.

- Place your hands on the top of your hips, and square the front of your pelvis; release your hands and hang your arms.

- As you inhale, raise your arms forward and then overhead, as in Figure 3-4a.

-

As you exhale, bend forward from the hips, soften your right knee and both arms, and hang down, as Figure 3-4b illustrates.

If your head isn’t close to your right knee, bend your knee more. If you have the flexibility, straighten your right knee — but keep it soft.

-

As you inhale, roll up slowly, stacking the bones of your spine one at a time from the bottom up, and then raise your arms overhead; relax your head and neck downward.

Rolling up is the safest way to come up, but if you don’t have back problems, you may want to try the more advanced techniques covered earlier in the section after a few weeks.

-

Repeat Steps 3 and 4 three times, and then stay in Step 4 for 6 to 8 breaths.

- Repeat the same sequence on the left side.

Note:

In the classic version of this posture, both legs are straight and the forehead presses against the forward leg.

To make the posture more challenging, square your hips forward and rotate your back foot inward.

To make the posture more challenging, square your hips forward and rotate your back foot inward.

Triangle posture: Utthita trikonasana

The Sanskrit word utthita (pronounced oot-hee-tah) means “raised,” and trikona (pronounced tree-ko-nah) means “triangle.” The triangle posture stretches the sides of the spine, the backs of the legs, and the hips. It also stretches the muscles between the ribs (the intercostals), which opens the chest and improves breathing capacity.

- Stand in the mountain posture, exhale, and step out to the right about 3 to 3½ feet (or the length of one leg) with your right foot.

-

Turn your right foot out 90 degrees. On your left foot, have your toes turned slightly in rather than straight ahead.

An imaginary line drawn from the right heel (toward the left foot) should bisect the arch of the left foot.

- Face forward and, as you inhale, raise your arms out to the sides parallel to the line of the shoulders (and the floor) so that they form a T with your torso (see Figure 3-5a).

-

As you exhale, reach your right hand down to your right shin as close to the ankle as is comfortable for you, and then reach and lift your left arm; as much as you can, bring the sides of your torso parallel to the floor.

Bend your right knee slightly, as in Figure 3-5b, if the back of your leg feels tight.

-

Soften your left arm and look up at your left hand.

If your neck hurts, look down or halfway down at the floor.

- Repeat Steps 3 through 5 three times, and then stay in Step 5 for 6 to 8 breaths.

- Repeat the same sequence on the left side.

Note:

In the classic version of this posture, the arms and legs are straight and the trunk is parallel to the floor. The right hand is on the floor outside the right foot.

Reverse triangle posture: Parivritta trikonasana variation

The Sanskrit word parivritta (pronounced pah-ree-vree-tah) means “revolved,” which makes perfect sense with this posture. The action of twisting and untwisting increases circulation of fresh blood to the discs between the spinal vertebrae (intervertebral discs) and keeps them supple as you grow older. The reverse triangle also stretches the backs of your legs, opens your hips, and strengthens your neck, shoulders, and arms.

- Standing in the mountain posture, exhale and step the right foot out to the right about 3 to 3½ feet (or the length of one leg).

- As you inhale, raise your arms out to the sides parallel to the line of your shoulders (and the floor) so that they form a T with your torso, as Figure 3-6a illustrates.

- As you exhale, bend forward from your hips and then place your right hand on the floor near the inside of your left foot.

-

Raise your left arm toward the ceiling and look up at your left hand; soften your knees and your arms, and then bend your left knee, or move your right hand away from your left foot (and more directly under your torso), as in Figure 3-6b, if necessary.

If you feel neck strain, turn your head toward the floor.

-

Repeat Steps 2 through 4 three times, and then stay in Step 4 for 6 to 8 breaths.

- Repeat the same sequence on the left side.

Note:

In the classic version of this posture, the feet are parallel and the legs and arms are straight. The torso is parallel to the floor, and the bottom hand rests lightly outside the opposite side foot.

Warrior I: Vira bhadrasana I

The Sanskrit word vira (pronounced vee-rah) is often translated as “hero,” and bhadra (pronounced bhud-rah) means “auspicious.” This posture, also known as just warrior, strengthens your legs, back, shoulders, and arms; opens your hips, groin, and chest; increases strength and stamina; and improves balance. As its name suggests, this posture instills a feeling of fearlessness and inner strength. For pointers on moving into this posture, go to

The Sanskrit word vira (pronounced vee-rah) is often translated as “hero,” and bhadra (pronounced bhud-rah) means “auspicious.” This posture, also known as just warrior, strengthens your legs, back, shoulders, and arms; opens your hips, groin, and chest; increases strength and stamina; and improves balance. As its name suggests, this posture instills a feeling of fearlessness and inner strength. For pointers on moving into this posture, go to http://www.dummies.com/go/yogaaiofd.

-

Stand in the mountain posture and, as you exhale, step forward approximately 3 to 3½ feet (or the length of one leg) with your right foot (see Figure 3-7a).

Your left foot turns out naturally, but if you need more stability, turn it out more (so that your toes point to the left).

- Place your hands on the top of your hips, and square the front of your pelvis; release your hands and hang your arms.

-

As you inhale, raise your arms forward and overhead, and bend your right knee to a right angle (so that your knee is directly over your ankle and your thigh is parallel to the floor), as in Figure 3-7b.

If your lower back is uncomfortable, lean your torso slightly over your forward leg until you feel a release of tension in your back.

- As you exhale, return to the starting place in Figure 3-7a; soften your arms and face your palms toward each other, and look straight ahead.

- Repeat Steps 3 and 4 three times, and then stay in Step 3 for 6 to 8 breaths.

- Repeat Steps 1 through 5 on the left side.

Warrior II: Vira bhadrasana II

Like the warrior I posture covered in the preceding section, warrior II strengthens your legs, back, shoulders, and arms. It focuses more on your hips and groin, and it increases strength and stamina; it also improves balance. Use the following steps as your guide.

- Stand in the mountain posture; exhale and step out to the right about 3 to 3½ feet (or the length of one leg) with your right foot.

-

Turn your right foot out 90 degrees, and have the toes of your left foot turned slightly in rather than forward.

An imaginary line drawn from your right heel toward your left foot should bisect the arch of your left foot.

- Face forward and, as you inhale, raise your arms out to the sides, parallel to the line of your shoulders (and the floor), so that they form a T with your torso (see Figure 3-8a).

- As you exhale, turn your right foot out 90 degrees and bend your right knee over your right ankle so that your shin is perpendicular to the floor, as in Figure 3-8b; if possible, bring your right thigh parallel to the floor.

-

Repeat Steps 3 and 4 three times, keeping your arms in a T; then turn your head to the right, looking out over your right arm, and stay for 6 to 8 breaths.

- Repeat Steps 1 through 5 on the left side.

Be careful not to force your hips open; doing so may cause problems with your knees.

Be careful not to force your hips open; doing so may cause problems with your knees.

Standing spread-legged forward bend: Prasarita pada uttanasana

The Sanskrit word prasarita (pronounced prah-sah-ree-tah) means “outstretched,” and pada (pronounced pah-dah) means “foot.” This posture, also called the wide-legged standing forward bend, stretches your hamstrings and your adductors (on the insides of the thighs) and opens your hips. The hanging forward bend increases circulation to your upper torso and lengthens your spine. Figure 3-9 illustrates this posture.

- Stand in the mountain posture, exhale, and step your right foot out to the right about 3 to 3½ feet (or the length of one leg).

- As you inhale, raise your arms out to the sides, parallel to the line of your shoulders (and the floor), so that they form a T with your torso.

- As you exhale, bend forward from the hips and soften your knees.

-

Hold your bent elbows with the opposite-side hands, and hang your torso and arms.

- Stay in Step 4 for 6 to 8 breaths.

Note:

In the classic version of this posture, the legs are straight, the head is on the floor (and the chin presses the chest), and the arms reach back between the legs, with the palms on the floor.

Half chair posture: Ardha utkatasana

The Sanskrit word ardha (pronounced ahrd-ha) means “half,” and utkata, (pronounced oot-kah-tah) translates as “powerful.” The half chair posture strengthens the back, legs, shoulders, and arms and builds overall stamina. If you find this posture difficult or you have problem knees, you may want to skip this position for now and return to it after your leg muscles become a little stronger. Don’t overdo this exercise (either by holding the position too long or by repeating it more than recommended), or you’ll have sore muscles the next day. But there’s no harm in experiencing some muscle soreness, either, especially if you haven’t exercised in a long time. Check out Figure 3-10 for guidance.

- Start in the mountain posture and, as you inhale, raise your arms forward and up overhead, with your palms facing each other.

- As you exhale, bend your knees and squat halfway to the floor.

-

Soften your arms, but keep them overhead; look straight ahead.

- Repeat Steps 1 through 3 three times, and then stay in Step 3 for 6 to 8 breaths.

Note:

In the classic version of this posture, the feet are together and the arms are straight, with the fingers interlocked and the palms turned upward. The chin rests on the chest.

Downward-facing dog: Adhomukha shvanasana

The Sanskrit word adhomukha (pronounced ahd-ho-mook-hah) means “downward facing,” and shvan (pronounced shvahn) means “dog.” Inspired by a dog’s leisurely stretching, the downward-facing dog practice stretches the entire back of your body and strengthens your wrists, arms, and shoulders. This posture is a good alternative for beginning students who aren’t yet ready for inversions like the handstand and headstand. Because the head is lower than the heart, this asana circulates fresh blood to the brain and acts as a quick pick-me-up when you’re fatigued.

-

Start on your hands and knees; straighten your arms, but don’t lock your elbows (see Figure 3-11a).

Be sure that the heels of your hands are directly under your shoulders, with your palms on the floor, your fingers spread, and your knees directly under your hips. Emphasize pressing down with the thumbs and index fingers, or the inner web of your hand.

- As you exhale, lift and straighten (but don’t lock) your knees; as your hips lift, bring your head to a neutral position so that your ears are between your arms.

-

Press your heels toward the floor and your head toward your feet, as in Figure 3-11b.

If your hamstrings feel tight, try putting a little bend in your knees to help you straighten your spine.

Don’t complete Step 3 if doing so strains your neck.

Don’t complete Step 3 if doing so strains your neck.

- Repeat Steps 1 through 3 three times, and then stay in Step 3 for 6 to 8 breaths.

Note:

In the classic posture, the feet are together and flat on the floor, the legs and arms are straight, and the top of the head is on the floor, with the chin pressed to the chest.

Be careful not to hold this posture too long if you have problems with your neck, shoulders, wrists, or elbows.

Be careful not to hold this posture too long if you have problems with your neck, shoulders, wrists, or elbows.

Standing as an art

Standing as an art Using standing postures to enhance body and mind

Using standing postures to enhance body and mind Practicing fundamental standing postures

Practicing fundamental standing postures You can creatively adapt many postures from other groups to a standing position, which you can then use as a learning (or teaching) tool or for therapeutic purposes. Consider, for example, the well-known cobra posture, a back bend that many beginning students find hard on the lower back (see Book II,

You can creatively adapt many postures from other groups to a standing position, which you can then use as a learning (or teaching) tool or for therapeutic purposes. Consider, for example, the well-known cobra posture, a back bend that many beginning students find hard on the lower back (see Book II,

Be careful of all forward bends if you have a disc problem. If you’re unsure, check with your doctor or health professional.

Be careful of all forward bends if you have a disc problem. If you’re unsure, check with your doctor or health professional.

The Sanskrit word vira (pronounced vee-rah) is often translated as “hero,” and bhadra (pronounced bhud-rah) means “auspicious.” This posture, also known as just warrior, strengthens your legs, back, shoulders, and arms; opens your hips, groin, and chest; increases strength and stamina; and improves balance. As its name suggests, this posture instills a feeling of fearlessness and inner strength. For pointers on moving into this posture, go to

The Sanskrit word vira (pronounced vee-rah) is often translated as “hero,” and bhadra (pronounced bhud-rah) means “auspicious.” This posture, also known as just warrior, strengthens your legs, back, shoulders, and arms; opens your hips, groin, and chest; increases strength and stamina; and improves balance. As its name suggests, this posture instills a feeling of fearlessness and inner strength. For pointers on moving into this posture, go to