| GIANT PANDA Ailuropoda melanoleuca |

HB 120–180cm; T 8–16cm; SH 71–86cm; W ♀ 70–100kg, ♂ 85–125kg

Unmistakable and probably the most recognisable mammal on Earth. The distinctive white-and-black coloration is not aposematic as in skunks and other black-and-white carnivores. It has been suggested that it helps pandas locate one another in dense habitat during the breeding season, although they clearly utilise scent-marking and calls to find mates, as do most carnivores. The ear and eye markings are thought to be important for intraspecific communication. Cubs are tiny at birth, weighing only around 100g, relatively much smaller compared with the mother’s size than in all other bears. Cubs have sparse white fur: black markings appear gradually by 3–4 weeks. The forefoot has a ‘false thumb’, actually a greatly modified sesamoid bone (normally tiny in bears) with its own pad, which helps in grasping and manipulating bamboo, the species’ main food source.

Distribution and Habitat

Restricted to 6 mountain ranges in the C China provinces of Sichuan (which has about 75% of the population), Gansu and Shaanxi. Formerly widespread across C and SW China, into N Myanmar and N Vietnam. Dependent on temperate montane forest with abundant bamboo at altitudes of 1,200–4,100m. Suitable habitat now occurs only on steep rugged slopes that are inaccessible for agriculture.

Feeding Ecology

The most specialised and herbivorous of bears, and indeed of carnivores, with more than 99% of the diet made up of bamboo. Eats more than 60 bamboo species, moving seasonally between altitudes to exploit the availability of different types as they germinate and grow. Most parts of the plant are consumed, but it prefers leaves and shoots, which are high in protein and easier to digest than stems and branches. Although it is a capable climber, it eats on the ground, usually in dense stands of bamboo, in a sitting or reclining position. It occasionally eats other items, particularly in years of bamboo die-off, when it is forced to seek other food, including leaves, shoots, roots and the bark of other plants, crops (including wheat, kidney beans and pumpkin) and fruits. Recorded occasionally scavenging from carrion and human refuse. Foraging occurs day and night, with about 50–55% of the time spent eating or gathering bamboo; adults eat 12–15kg a day. Unlike in other bears, foraging patterns do not change during the year to maximise periods of high food abundance. As food is available year-round, Giant Pandas do not hibernate. Females fast for a limited period of 2–3 weeks when they give birth.

Social and Spatial Behaviour

Solitary and non-territorial, with considerable overlap in home ranges. Individuals may remain in small core areas ≤3km2 for extended periods; these overlap little between same-sex adults, although it is unknown if they are actively defended as territories. Range size 1–60km2, averaging 5–15km2, and changes seasonally as different bamboo species flower and Giant Pandas migrate vertically to track food. Usually stays in high altitudes during summer and spring, and descends to lowlands in winter to forage and avoid deep snow. Unusually among bears, it appears that young females disperse and young males settle close to their natal range. Density estimates are poorly known and controversial; 48/100km2 estimated for Mabian NR, Sichuan.

Reproduction and Demography

Giant Pandas have a reputation for poor reproduction, but this arises from the difficulties of breeding them in captivity. Wild Giant Pandas have a similar reproductive output to other bears. Seasonal. Mating March–May. Oestrus 12–25 days; gestation 97–163 days (averaging 145–146 days in the wild), with delayed implantation. Cubs born August–September. Litter size 1–2 (very rarely 3); with twins, the mother often ignores the second cub, which dies. It is the only bear that regularly gives birth to more cubs than it raises, the reasons for which are unknown. Weaning at 8–9 months. Independence at around 1.5 years. Inter-litter interval 2–3 years, averaging 2.2. Sexual maturity at 4.5 years for both sexes: earliest breeding 5–7 years for females and probably similar for males. Females can reproduce until their early 20s, males until age 17. MORTALITY Post-emergence (i.e. excluding abandoned twins), most cubs survive, with mortality estimated at 10–30%. Adult mortality normally ≤10% for both sexes, except in occasional years of mass bamboo die-offs, when starvation is a serious threat, e.g. at least 138 adults starved in a die-off event in the mid-1970s. No definite records of predation: Giant Panda remains have been found in Leopard scats, although it is not clear if the bears were killed or scavenged. Brown Bear, Asiatic Black Bear and Dhole co-occur and could plausibly kill subadults and perhaps adults. Cubs are helpless for a prolonged period and could be killed also by Snow Leopard, Mainland Clouded Leopard, Asiatic Golden Cat and Yellow-throated Marten. LIFESPAN Maximum 26 years in the wild, 37 in captivity.

Status and Threats

Numbers in the wild (excluding dependent young <1.5 years of age) estimated to have increased to ~1,860 in 2014 from ~1,200 in 1988, although the species’ shyness and the rugged habitat make accurate population estimates challenging. They are strictly protected in China and now rarely killed by humans; occasionally killed unintentionally in snares set for ungulates. Reforestation has led to a ~12% increase in occupied range since 2004, although continued destruction of habitat for forestry and agriculture is a grave threat elsewhere in the range. Now restricted to 33 subpopulations in 6 mountain ranges, each of which is an isolated island surrounded by deforested areas and cultivated land. Within each, habitat is further fragmented by cultivation and forestry, so that most populations number fewer than 50 adults; 18 contain fewer than 10 individuals. An estimated 67% of the population is protected in 67 reserves, but both protected and non-protected areas remain vulnerable to human activities. As well as ongoing habitat conversion, pressures include bamboo-shoot collection by local people, expanding livestock populations and associated grazing pressure, and infrastructure development, especially the building of highways and dams that further fragments habitat. CITES Appendix I; Red List VU, population trend Increasing.

Plate 59

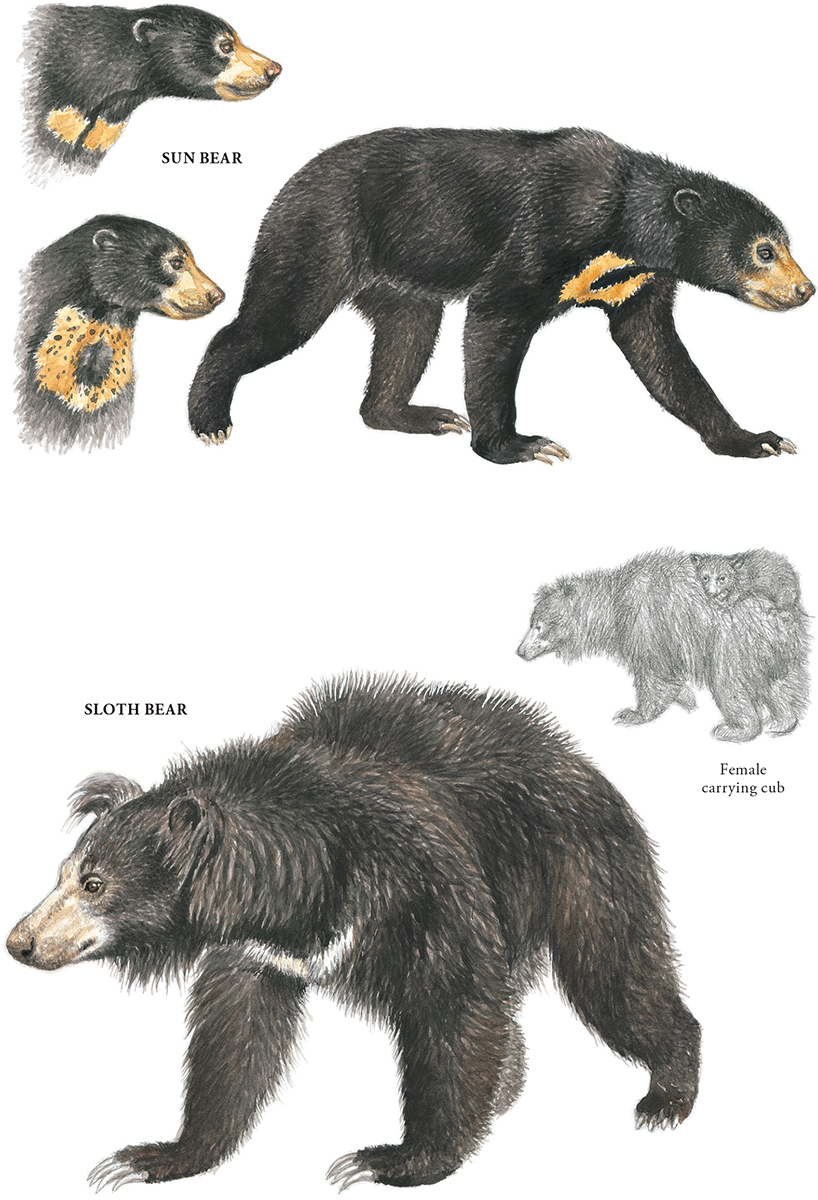

| SUN BEAR Helarctos malayanus |

HONEY BEAR, MALAYAN SUN BEAR

HB 100–140cm; T 3–7cm; SH 70cm; W ♀ 25–50kg, ♂ 34–80kg

Smallest bear, with short jet-black (occasionally chocolate-brown) velvety fur, very small ears and a pale muzzle and chin. Named for its distinctive orange, yellow or cream chest patch, which is highly variable in shape and sometimes absent altogether. Distribution and Habitat Occurs patchily, from E Bangladesh throughout Indochina to Malaysia, Sumatra and Borneo. Recorded barely in Yunnan, S China, but very rarely, and possibly only as transients from Myanmar. A published 2017 photo record from extreme S Tibet was actually an Asiatic Black Bear. Extinct in Singapore. Optimum habitat is dense lowland dry and wet forests, as well as montane evergreen forest and swamp forest, from sea-level to 3,000m. Extends into marginal habitats such as mangroves and plantations, provided dense forest is nearby. Feeding Ecology Omnivorous, with a narrow diet dominated by insects, honey and fruits. Eats more than 100 species of insects, especially social species such as ants, termites and bees. Breaks into nests with its powerful claws, and uses its extremely long tongue to consume adult insects, larvae, eggs, honey, honeycomb, beeswax and nesting resin. Fruits are also extremely important, with more than 40 species eaten, especially figs. Occasionally eats other invertebrates such as earthworms and scorpions, reptiles (including small turtles), rodents and birds’ eggs. Eats little vegetation, but apparently relishes coconut-palm growth shoots (‘hearts’); their extraction kills the trees and creates conflict in plantations. Also may raid fruit orchards and crops such as sugar cane, potatoes and manioc. Livestock depredation is almost unknown, except for exceptional attempts at raiding poultry coops. Scavenges from human dumpsites, especially when natural food is scarce. Foraging is mainly diurnal when undisturbed, but almost exclusively nocturnal when close to humans. Highly arboreal, adeptly climbing trees to forage for fruits and insect nests, and building large nest platforms from branches for resting. Does not hibernate. Social and Spatial Behaviour Solitary; reported to gather occasionally around fruiting trees. Spatial patterns poorly known; unlikely to be strongly territorial, but 4 collared males in Borneo occupied small exclusive core areas of less than 1km2 with larger overlapping ranges of 6.2–20.6km2. Two females in poor habitat had small ranges of around 4km2. Density estimates 4.3–5.9/100km2 (Khao Yai NP, Thailand). Reproduction and Demography The only bear species that is not seasonal at all (although reproduction is very poorly known in the wild). Gestation short, 95–97 days (captivity), suggesting no delayed implantation. One cub (exceptionally 2) born in a tree cavity or hollow log. First reproduction 3 years for females, probably later for males. MORTALITY Poorly known. Humans cause most deaths in many populations. Vulnerable to starvation in poor fruiting years, when conflicts with humans (and related retributive killings) also rise. Confirmed predators include Tiger and Reticulated Python (1 known case, of an old, starvation-weakened adult). LIFESPAN Unknown in the wild, 24–25 years in captivity. Status and Threats Numbers have declined an estimated 35% since the mid-1980s, chiefly due to pervasive commercial hunting, and deforestation from logging and conversion to plantations. Hunted mainly for gall bladders for traditional Chinese medicinal use, and for bear-paw soup. Hunting reduced one Thai Sun Bear population by an estimated 50% in 20 years. CITES Appendix I; Red List VU, population trend Decreasing.

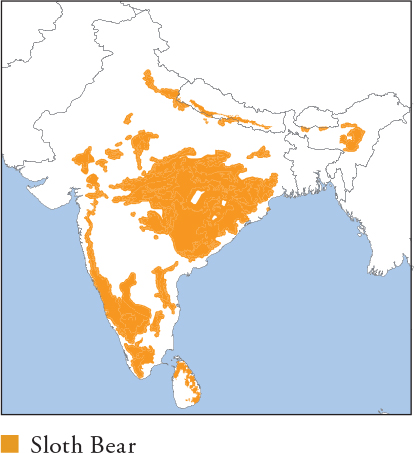

| SLOTH BEAR Melursus ursinus |

HB 140–190cm; T 8–17cm; SH 60–92cm; W ♀ 50–100kg (exceptionally to 120kg), ♂ 70–150kg (exceptionally to 190kg)

Solid black coloration, rarely chocolate brown or reddish brown, with a crescent-shaped whitish-cream patch on the chest, and a pale muzzle and face. Fur is long and shaggy. Distribution and Habitat Restricted to Sri Lanka, India (90% of the range) and Nepal; extends very marginally into S Bhutan, these are likely vagrant bears from India. Formerly Bangladesh, where it is now presumably extinct. Lives primarily in dry or moist forest, scrubland, savannah and grassland, mostly in lowlands below 1500m, but occasionally to 2,000m, e.g. Western Ghats, India. Feeding Ecology The only bear species adapted for myrmecophagy, with flexible, protrusible lips and nostrils that it can seal when sucking termites and ants. Switches mainly to fruits, especially figs, during the fruiting season; mostly eats fallen fruits rather than foraging in trees, although it is a capable climber, e.g. to access honey. Eats tubers, roots and some flowers, but otherwise consumes little vegetation. Rarely eats meat, aside from exceptional meals of small vertebrates and carrion. Feeds on crops, including sugar cane, maize, rice, potatoes and sweet potatoes. Livestock depredation is virtually unknown. Has a reputation for unpredictability and aggression, and may attack people, e.g. 350 injuries and 16 fatalities in Madhya Pradesh, India, in 2001–15. Attacks occur mostly in fields and adjacent forest when people are collecting non-timber forest products, e.g. bamboo, seeds and flowers, or grazing livestock; humans are rarely hunted as prey. Foraging is mainly nocturnal. Pregnant females den for up to 2 months, although it is unclear if they actually hibernate; other cohorts are active year-round. Social and Spatial Behaviour Solitary and non-territorial. Home ranges often overlap extensively, and individuals may feed in close proximity without interacting, although females appear to maintain small exclusive core areas. Home range size averages 2km2 (♀s) to 4km2 (♂s) in Sri Lanka, to 25–100km2 in Panna NP, India. Density estimates 6–8/100km2 (dry forest habitat, Panna NP) to 27/100km2 (productive Terai grassland and forest, Royal Chitwan NP, Nepal). Reproduction and Demography Seasonal. Mating May–July. Gestation 4–7 months (captivity), with delayed implantation. Litter size 1–3 (usually 2), with cubs born November–January. Cubs emerge from the den at around 6–10 months, and ride on the mother’s back for up to 6 months, probably as a defence against predation. Weaning at 12–14 months, and cubs accompany the mother for 1.5 or 2.5 years, depending on food availability. First breeding at 4 years for females, probably later for males. MORTALITY Poorly known. Humans are the main predator; natural predation of adults is rare, but is known by Tiger and Leopard. LIFESPAN 40 years in captivity. Status and Threats Reasonably secure inside protected areas, but outside suffers heavily from habitat fragmentation and anthropogenic killing. Killed retributively and preventively in conflict situations, as well as for commercial trade in its parts, particularly gall bladders. In some parts of India and Nepal, females are killed and cubs captured to be trained mainly by Kalandar gypsies as ‘dancing bears’, illegal (since 1972) and enforced (since 2009), but still practised in the India–Nepal border region. CITES Appendix I; Red List VU, population trend Decreasing.

Plate 60

| ANDEAN BEAR Tremarctos ornatus |

SPECTACLED BEAR

HB 130–190cm; T <10cm; SH 70–90cm; W ♀ 60–80kg, ♂ 100–175kg (exceptionally to 200kg)

The only bear in South America. Typically black, occasionally reddish brown, with variable, pale facial ‘spectacles’ that usually extend onto the throat and chest, and are unique to individuals. Distribution and Habitat Endemic to the tropical Andes in Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia; recently confirmed in NW Argentina (but probably transient dispersers) and possibly occurs in Darién region, Panama. Optimum habitat is high-elevation humid forest and páramo, but it inhabits a variety of forests, woodland and grassland at 250–4,750m. An isolated population lives in coastal desert scrub forest around Cerro Chaparrí, NW Peru. Feeding Ecology Perhaps the most herbivorous of bears after Giant Panda, eating mainly bromeliads and fruits (especially of the fig and avocado families). Opportunistically eats cacti, moss, orchids, bamboo, tree wood, palms, honey, invertebrates, birds and small mammals. Mountain Tapirs are sometimes observed with wounds suggestive of bear attacks, and a camera-trap photo from Colombia shows an Andean Bear unequivocally attacking an adult tapir. Kills cattle, including adults, and occasionally sheep, donkeys and horses. Eats crops, particularly corn, and is considered a major crop pest in some places. Foraging is primarily diurnal (0600–2100), although probably more nocturnal where it is persecuted. Given that its preferred food is above ground, it is highly arboreal. Builds a large nest-like ‘feeding platform’ by pulling fruiting branches into a bunch to support its weight while feeding; this possibly doubles as a rest bed. Readily scavenges, especially from livestock carcasses. With food available year-round, does not hibernate. Social and Spatial Behaviour Solitary, but reported to feed in groups (of up to 9) in cornfields and cactus groves. Spatial patterns are poorly known, but like other bears it is unlikely to be strongly territorial. Home ranges of radio-collared bears in Ecuador overlap considerably and average 34km2 (♀s) to 150km2 (♂s). Density estimates 7.5/100km2(N Ecuador). Reproduction and Demography Seasonal. Mating in the only well-studied wild population (NW Peru) occurs December–January with births late-June to mid-October. Gestation 160–255 days (captivity) with delayed implantation. 1–4 cubs (usually 2) are born. They emerge at around 3 months, coinciding with the following fruiting season, and accompany the mother for up to 14 months (possibly longer). First reproduction at 4 years for both sexes (captivity). MORTALITY Poorly known. Humans are the main cause of death in many populations, estimated to be at least 180 bears annually (a minimum estimate) across the range. LIFESPAN Unknown in the wild, 36 years in captivity. Status and Threats Reduced to an estimated 42% of its historical range, now present in only 260,000km2 in many isolated populations scattered along the Andes. The largest, least fragmented intact sites are in Peru and Bolivia. Habitat destruction from forestry and agriculture is the chief threat, although human hunting is equally grave for many populations. Killed mainly for crop raiding and cattle killing, as well as for fur, meat and some traditional medicinal use. Dairy cow production is increasing rapidly in parts of the range, e.g. N Ecuador, driving an escalation of conflict-related killing. CITES Appendix I; Red List VU, population trend Decreasing.

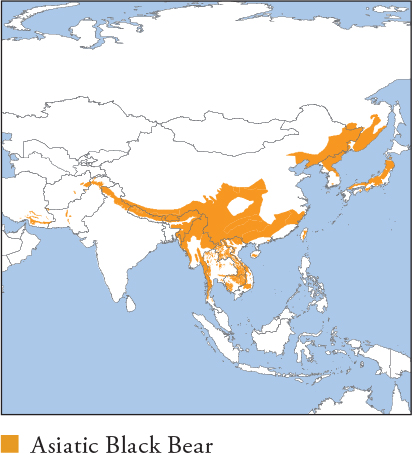

| ASIATIC BLACK BEAR Ursus thibetanus |

HIMALAYAN BLACK BEAR, MOON BEAR, TIBETAN BLACK BEAR

HB ♀ 110–150cm, ♂ 120–189cm; T <12cm; SH 70–100cm; W ♀ 40–140kg, ♂ 60–200kg

Solid black coloration, often paler on the muzzle and face, and usually with a characteristic crescent-shaped cream patch on the chest. A rare chocolate-brown morph exists, and a highly variable blond morph is known from Cambodia, Laos and Thailand. Distribution and Habitat Southern Asia in a narrow band mostly associated with mountains, from SE Iran across C Asia into Southeast Asia (except Malaysia) and S China, including Taiwan, NE China, the Russian Far East, the Korean Peninsula and Japan. Lives primarily in temperate and tropical forested habitats in hilly and mountainous terrains to 4,300m. Avoids open country, but enters plantations, agricultural fields and open alpine meadows in forested habitat. Westernmost population, in S Pakistan/Iran, lives in arid thorn forest. Feeding Ecology Chiefly herbivorous, with 80–90% of the diet comprising plant matter. Diet varies seasonally as it moves between habitats and elevations, tracking food availability. In spring, eats mainly succulent young vegetation, including grass, leaves, forbs and bamboo shoots, switching to fruits (including berries) in summer, and hard mast such as oak acorns, beechnuts, walnuts, chestnuts and hazelnuts in autumn. Invertebrates are consumed when available, typically peaking in summer. Vertebrates to the size of small (10–20kg) ungulates such as muntjacs and serows are also eaten. Active hunting occurs, although most meat is probably scavenged. Both sexes hibernate in winter in the northern part of its range (October–May; Russia), while only pregnant females hibernate in the tropics; southern bears that do not hibernate eat mainly hard mast and fruits. Feeds in fruit orchards, plantations (where it ring-barks trees to access the tender cambium) and crops, especially corn and oats. Humans are rarely attacked, and probably never as prey. Foraging is mainly diurnal, although nocturnal activity increases in autumn, when hard mast is abundant, e.g. Taiwan. Readily scavenges, especially from mammals caught in hunters’ traps. Social and Spatial Behaviour Solitary and appears non-territorial. Home range size averages 26km2 (♀s) to 66km2 (♂s) in Japan, and 117km2 (1 ♀) and 27–202km2 (♂s) in Taiwan. Ranges overlap extensively, but females and young males avoid productive areas where adult male ranges concentrate during autumn (Taiwan). Density estimates 8–29/100km2(Khao Yai NP, Thailand). Reproduction and Demography Likely seasonal, especially in temperate areas; poorly known from the tropics. Mating May–July. Gestation 6–7 months (captivity), with delayed implantation. 1–3 cubs (most often 2) born December–March (Russia). Cubs accompany the mother for 2–3 years. Sexual maturity 3–4 years for both sexes (captivity). MORTALITY Humans are the main cause of death in many populations. Known natural predators of adults include Brown Bear, Tiger and (rarely) other Asiatic Black Bears. LIFESPAN Unknown in the wild, 36 years in captivity. Status and Threats Chief threats are habitat loss, combined with intense human hunting that feeds a massive commercial market for bear products, mainly bile used in the Asian medicinal trade and paws for luxury restaurants. Bear farms are common in China, Vietnam and, increasingly, Laos for bile production. Some are ostensibly self-supporting, but many do not breed bears, and wild bear products are more valuable, fuelling ongoing hunting and capture of wild bears. Relict in Iran (<200) and South Korea (~40, a reintroduced population in Jirisan NP). Sport hunting is legal only in Russia (75–100/year) and Japan (around 500/year); illegal and/or nuisance killing results in an additional 500 and 1,000–2000 deaths, respectively. CITES Appendix I; Red List VU, population trend Decreasing.

Plate 61

| AMERICAN BLACK BEAR Ursus americanus |

HB ♀ 120–168cm, ♂ 129–188cm; T <12cm; SH ♀ 63–85cm, ♂ 72–103.5cm; W ♀ 40–150kg (exceptionally to 190kg), ♂ 60–300kg (exceptionally to 400kg)

Smallest of North America’s bears and endemic to that continent. Colour is highly variable, most often black but also many shades of brown (‘Cinnamon Bear’, common in the W USA); a grey-blue morph, ‘Glacier Bear’, in Alaska and NW Canada; and a cream morph, ‘Kermode Bear’, which occurs only in coastal British Columbia (10–25% of the population). There is some evidence that Kermode adults are more successful than black individuals at catching salmon in daylight (but not in darkness), possibly because their light coloration is less conspicuous to salmon against daylit sky. Except in the Kermode morph, the muzzle is usually a contrasting shade of buff-brown, useful for distinguishing the species from Brown Bear. Cubs of any colour may be born into the same litter, and brown cubs often darken after their second year, occasionally becoming black by adulthood. Up to 80% of cubs have a white chest patch that usually disappears but is retained in some adults.

Distribution and Habitat

Widespread and abundant in most of Canada, and the E and W USA (including Alaska), becoming patchy and fragmented in the S USA and N Mexico. Adaptable, and occupies a wide range of forested habitats from sea-level to 3,500m. Generally avoids areas without cover, although a unique population has colonised open coastal tundra in NE Canada since the recent local extinction of Brown Bears. Readily occupies human landscapes, e.g. farmland and peri-urban areas, provided there is cover.

Feeding Ecology

Omnivorous, feeding mainly on vegetation, with a relatively small proportion of the diet consisting of animal matter. As in other bears, the diet shifts seasonally, reflecting available food sources. Eats mainly new grasses, buds, shoots and forbs in spring; fruits and soft mast in summer; and hard mast such as hazelnuts, oak acorns and Whitebark Pine nuts, and berries, including huckleberries and buffalo berries, in autumn. Kills are made opportunistically in any season, but especially of winter-debilitated and newborn ungulates in spring. A capable hunter that is recorded killing animals to the size of Moose cows, but most kills are the size of White-tailed Deer fawns or smaller, e.g. rodents, birds, reptiles, fish and invertebrates. Carrion eater, especially of winter-killed ungulates after emerging from hibernation in spring. Readily exploits foods from human sources, especially during autumn hyperphagia. Occasionally kills livestock and eats crops such as apples, oats and corn, and can become a pest by raiding domestic beehives, suburban bird feeders, refuse bins, dumpsters, campgrounds and refuse dumps. Humans are sometimes killed: although rare, kills are thought to be mainly predatory rather than in defence of food or cubs. There are very few records of female Black Bears attacking humans while defending cubs. Foraging is mostly solitary and diurnal, with early-morning and late-afternoon peaks; becomes more nocturnal in human-dominated areas. Forms tolerant congregations at food-rich sites like refuse dumps. Hibernates throughout its range for 3–7 months; in its southern range, where food is available year-round, only pregnant females and mothers with yearling cubs hibernate.

Social and Spatial Behaviour

Mostly solitary, except mothers with emerged cubs that stay in family groups for 16–18 months. Non-territorial, with enduring home ranges that overlap considerably with those of other adults. Females sometimes establish exclusive areas in their home range that they defend from other females, probably related to raising cubs. Excursions up to 200km outside their own range are fairly common in periods of food scarcity, especially during autumn hyperphagia; individuals typically return to their own range to hibernate. Depending on food availability, range size is 2–1,100km2, exceptionally reaching 7,000km2 in the NE Canadian tundra, where food is especially scarce. Ranges expand in seasons, years and regions of low food availability. Male ranges are typically 2–10 times the size of female ranges. Average range sizes include 6.9km2 (♀s) and 51.2km2 (♂s) in Tennessee, 17.1km2 (♀s) and 22.4km2 (♂s) in California, 28km2 (♀s) and 318km2 (♂s) in Massachusetts, 48.8km2 (♀s) and 112.1km2 (♂s) in Idaho, and 295km2 (♀s) and 495km2 (♂s) in Manitoba. Females mostly settle near their natal range; males disperse more widely. Dispersal distance is typically 10–220km. Density estimates 20/100km2 (SC Alaska), 40–50/100km2 (N Montana) and 120–150/100km2 (SW Washington).

Reproduction and Demography

Seasonal. Mating mid-May–July, occasionally as late as September in southern areas. Oestrus is ‘seasonally constant’, lasting until conception or the end of the breeding period. Gestation 200–253 days, with delayed implantation. Cubs born January–February (rarely December). Litter size 1–5, average 2–2.5. Weaning at 5.5–7 months. Independence at 16–17 months. Inter-litter interval usually 2 years, longer when food availability is low. Sexually mature at 2.5–3 (♀s) and 3.5 (♂s) years; earliest breeding at 3–8 (♀s; average 4.5–5.6 years) and 3.5–8 (♂s) years. Reproduction by females is possible until at least age 20. MORTALITY On average, 35% (eastern populations) to 46% (western populations) of cubs die in their first year, but cub mortality ranges from 0% (wilderness, Nevada) to 83% (urban area, Nevada). Mortality averages 23–28% (often much higher for individual populations, especially close to people) following independence, mainly from starvation and human causes, declining to on average 12% (western) to 18% (eastern) for adults. Even in populations not hunted, humans are often the main cause of death, especially from roadkills and problem animal control. Adults have few predators except Brown Bears and Grey Wolf packs, typically of hibernating individuals killed in their dens. Cubs are additionally vulnerable to predation by adult male American Black Bears, and occasionally by Bobcats and Coyotes; there is at least 1 record of Golden Eagle predation. LIFESPAN Maximum 24 (♀s) and 20 (♂s) years in the wild, 32 in captivity.

Status and Threats

Widespread and globally secure, with a total population estimated at 850,000–950,000. Has disappeared from large areas of its southern and mid-western US historic range, where remaining populations are patchy, and some are threatened (Florida and Louisiana) or endangered (Mexico). Vulnerable to severe habitat loss and fragmentation, but thought to be recolonising or increasing in much of its range. As many as 40,000–50,000 are legally killed annually by sport hunters and trappers in the USA and Canada. Sport hunting is illegal in Mexico. Poaching, illegal killing and roadkills are serious local threats for some populations. CITES Appendix II; Red List LC, population trend Increasing.

Plate 62

| BROWN BEAR Ursus arctos |

GRIZZLY BEAR

HB ♀ 140–228cm, ♂ 160–280cm; T 6.5–21cm; SH 90–152cm; W ♀ 55–277kg, ♂ 135–725kg

Second-largest terrestrial carnivore after the closely related Polar Bear. Massively built, with a distinctive shoulder hump, distinguishing it from similarly coloured morphs of American Black Bear. Colour is variable, ranging from light blond through various shades of brown to near black. Some individuals have blond tips to the hairs, giving a grizzled appearance, hence the name Grizzly Bear (used only in North America). Cubs often have a white or blond collar that usually fades after their first year, but sometimes persists in adults, especially in Eurasian populations. Size varies significantly, seasonally within populations and regionally between populations: smallest bears are W Eurasian, e.g. Syrian Bear (U. a. syriacus, the subspecies inhabiting Iran to Turkey), while bears with access to abundant salmon, e.g. in coastal habitats of Alaska, British Columbia and eastern Russia, are largest.

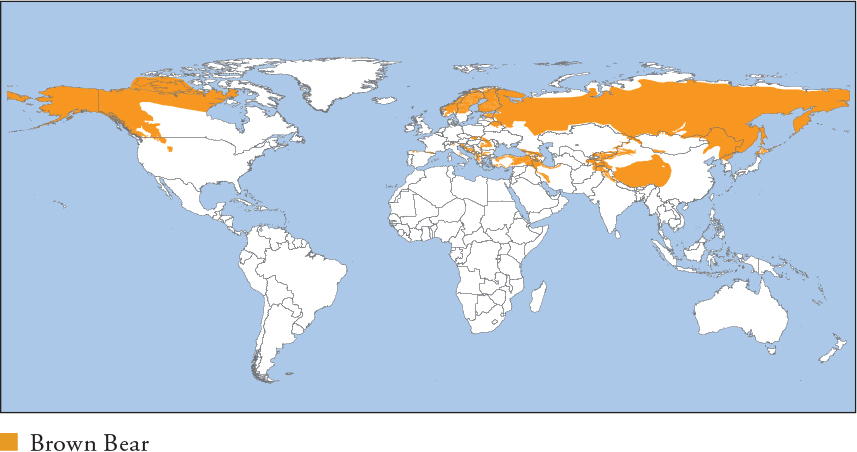

Distribution and Habitat

The most widespread bear, ranging across NW North America, the Russian Far East and through northern Asia, including Japan, to Fenno-Scandinavia, and south in progressively fragmented populations through the Tibetan Plateau to the Himalayas, SW Iran, Turkey and W Europe. Inhabits a wider variety of habitat types than any other ursid, including all types of temperate forest, coastal habitats, meadows, grassland, steppes, tundra and semi-desert, from sea-level to 5,000m.

Feeding Ecology

Highly omnivorous and opportunistic, with the broadest diet of any bear species, comprising all types of fungi, plant matter, invertebrates, fish, reptiles, birds, eggs and mammals. In most populations, the diet changes seasonally as bears move between habitats and elevations, reflecting food availability. In spring and early summer, they eat mainly grasses, shoots, sedges and forbs, and actively hunt newborn ungulates such as Elk, Moose and Caribou/Reindeer calves. Fruits, including berries, become increasingly important during summer and early autumn; roots and bulbs are also eaten, and may become critical in autumn for some inland populations if fruit crops are poor. Super-abundant salmon is a key food source for many coastal populations, especially in autumn during the spawning run. Invertebrates and hard mast are also important in summer and autumn, given their high fat content, e.g. Rocky Mountain bears in high talus slopes eat up to 40,000 Army Cutworm moths daily, and harvest Whitebark Pine nuts from American Red Squirrel middens almost exclusively. Meat dominates the diet at the end of winter as the bears emerge from hibernation to scavenge carcasses of winter-killed ungulates, and hunt weakened Moose, Elk, bison, Caribou/Reindeer, Wild Boar and various deer species; adult Musk-ox occasionally recorded. Occasionally kills livestock, raids crops and ransacks domestic beehives, typically peaking during autumn hyperphagia and especially when natural food sources are poor. Humans are sometimes killed, usually in defence of carrion or cubs, but occasionally as food. Loses 5–43% of its body mass during winter hibernation. Foraging is mostly solitary, but large seasonal congregations gather at food-rich sites like spring meadows, salmon runs, alpine-moth aggregations and refuse dumps. May cache food, especially large carcasses, by covering it with dirt and vegetation, and often lies close to the pile. Readily scavenges, including from human refuse.

Social and Spatial Behaviour

Solitary, but emerged cubs (≥3 months old) accompany their mothers for up to 3 years, and adults congregate amicably at seasonal feeding sites. Not classically territorial. Adults maintain enduring home ranges that often overlap extensively; subordinate bears give way to dominant individuals in well-defined dominance hierarchies that segregate individuals and prioritise access to food and mates. Range size is smallest in populations with concentrated dependable food sources such as salmon, e.g. 24–89km2 (♀s) and 115–318km2 (♂s) in coastal Alaska and British Columbia. Ranges generally increase inland where food sources are more dispersed, e.g. 281km2 (♀s) to 874km2 (♂s) in Yellowstone NP, USA; up to 2,434km2 (♀s) and 8,171km2 (♂s) in the C Canadian Arctic. Subadult bears occupy areas of up to 20,000km2, e.g. C Canadian Arctic, before settling into their adult range. Females tend to settle near their natal range, while males disperse more widely. Density estimates 1–3/1,000km2 (Norway), 3–4/1,000km2 (Arctic National WR, Alaska), 14–18/1,000km2 (Yellowstone NP), 47–80/1,000km2 (Glacier NP, USA), 135–190/1,000km2 (Abruzzo NP, Italy), to 191–551/1,000km2 (coastal Alaska).

Reproduction and Demography

Seasonal. Mating April (Eurasia) to mid-May (North America) until July. Oestrus 10–30 days; gestation 210–255 days, with delayed implantation. Cubs born January–March. Litter size typically 1–3, rarely to 6. Adoption and exchange of emerged cubs sometimes occurs. Weaning at around 18 months, independence at 2–3 years, occasionally as long as 4.5 years. Inter-litter interval averages 3.5 years, range 2–6, depending on food availability. Sexual maturity at 3.5 (♀s) and 5–5.5 (♂s) years; earliest breeding at 4–8.1 (♀s) and 5–8 (♂s) years. Reproduction by females possible until age 28. MORTALITY 13–44% of cubs die in their first 1.5 years. Adult mortality ≤10% (♀s) and 6–38% (♂s), higher rates occurring in hunted populations. Even in populations that are not hunted, humans are often the main cause of death. Adults have few predators except other Brown Bears and (rarely) Tigers; Russia). Both sexes (but usually males) occasionally kill cubs, and males sometimes kill other adults. Cubs are occasionally killed by Grey Wolf and Golden Eagle (1 confirmed record). LIFESPAN Maximum 25–30 years in the wild, reportedly 47 in captivity.

Status and Threats

Still widespread and relatively common in much of its northern range, with large numbers in W Canada (~25,000), Alaska (~33,000) and Russia (100,000–125,000). The next largest subpopulations are in W Europe, excluding Russia, and are fragmented (~15,400); W China (~5,000–6,000); and Hokkaido, Japan (~2,200). Southern range has undergone significant contraction and severe fragmentation into numerous very small and isolated populations. Extirpated from Mexico, most of the lower 48 United States, and most of its former range in Europe and the Middle East. Formerly occurred in N Africa, perhaps until the mid-1800s in Morocco and Algeria, and the only modern bear species to inhabit Africa. Globally secure, but small isolated populations are vulnerable to contact with humans. Legal sport hunting occurs in at least 18 range countries, with the largest numbers killed in Canada, Finland, Romania, Russia, Slovakia and the USA (Alaska only). Some 300–800 bears, a very high percentage of the population, are killed annually on Hokkaido to limit the population and manage conflict. CITES Appendix I – Bhutan, China, Mongolia, Mexico and Himalayan populations, Appendix II – elsewhere; Red List LC, population trend Stable.

Plate 63

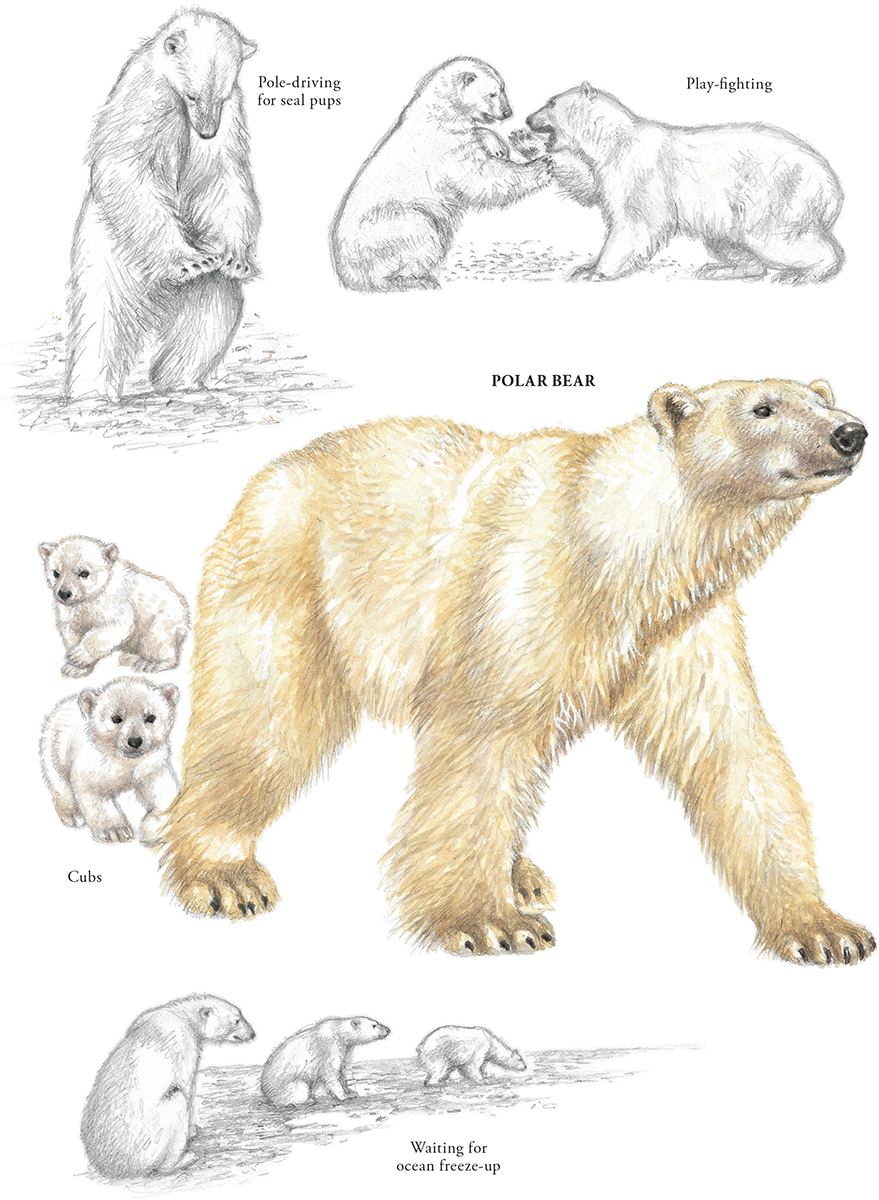

| POLAR BEAR Ursus maritimus |

HB ♀ 180–247cm, ♂ 200–285cm; T 6–21cm; SH 120–170cm; W ♀ 150–450kg, ♂ 300–655kg (exceptionally to 800kg)

The world’s largest terrestrial carnivore. The bear’s white fur is actually unpigmented and transparent, its shifting hue depending on reflected light, e.g. golden at sunset/sunrise and bluish when it is cloudy or misty. Impurities such as oils from kills also stain the fur, contributing to a dirty cream or yellowish colour. Skin is pink in young cubs, but completely black (as on nose) in adults; it was once thought to enhance the absorption of ultraviolet (UV) light, but the transparent hairs actually absorb UV before it reaches the skin. Hairs are also hollow, increasing insulation (and the reason why captive animals sometimes appear greenish due to algal growth inside the hair). Closely related to Brown Bear; ranges of the 2 species overlap minimally, chiefly in the W Canadian Arctic, where wild hybrids are rarely recorded – 2 were shot by hunters in Canada’s Northwest Territories, in 2006 (Banks Island) and 2010 (Victoria Island).

Distribution and Habitat

Circumpolar in the Arctic: Canada, the USA (Alaska), Russia, Norway (Svalbard) and Greenland. Transient in N Iceland, where it is usually shot, e.g. 2 in June 2008. Reliant on sea-ice habitats mostly within 300km of the coast, where marine productivity is the highest. Follows retreating ice northwards in summer where possible, e.g. N Greenland, where summer ice remains near the coast; otherwise forced inland, e.g. Hudson Bay, Canada. After the first few months of life, many individuals spend their entire lives on sea-ice.

Feeding Ecology

The most carnivorous bear species and profoundly dependent on seals and sea-ice for hunting; cannot hunt in open water. The most important prey species is Ringed Seal, followed by Bearded Seal, Harp Seal and Hooded Seal. Seals are caught by ‘still-hunting’, which involves patiently waiting at breathing holes, sometimes for hours; by carefully stalking basking seals either on ice or from water; or by ‘pole-driving’ into seal birth dens to catch newborn pups. Walruses are occasionally hunted, sometimes by stampeding colonies at haul-out sites, e.g. Wrangel Island, Russia, resulting in dozens of crushed animals, which are scavenged. Recorded killing Narwhals and Beluga Whales, usually when the whales are trapped in ice. During lean periods, e.g. summer, when some populations are restricted to ice-free land, opportunistically eats berries, kelp, grasses, fish, seabirds, eggs, small mammals, hares and Reindeer/Caribou, but it cannot survive indefinitely on this diet. Humans are killed extremely rarely, typically by starving male bears; 20 fatalities globally 1870–2014. Polar Bears have a prodigious ability to fast when food is scarce, dependent on extensive fat reserves accumulated from seals. Fasting bears enter a similar physiological state to hibernation, but remain active and alert. This can occur during food shortages in any season (in contrast to other bears, which fast only during winter hibernation). Pregnant females can fast for 8 months from the time they leave the ice to den until the next ocean freeze-up after birth. Healthy males and non-pregnant females easily fast for 4–6 months, but apart from sheltering temporarily in severe weather, they do not overwinter in dens. Foraging is mostly solitary, but congregations form around large carcasses, Walrus colonies and dumps. Readily scavenges, e.g. from beached whales and refuse.

Social and Spatial Behaviour

Solitary, but emerged cubs (≥3 months old) always accompany their mothers, and bears congregate amicably at food-rich areas and while waiting for the freeze-up, when unrelated adults often engage in highly social behaviour such as play-fights. Extremely mobile and has the largest home ranges of any carnivore; utilises different areas in its range depending on ice dynamics, but does not wander randomly as once thought. Annual ranges are smaller in near-shore areas with stable ice, averaging 50,000km2, compared with ranges on drift ice, which average 250,000km2. Hudson Bay females have annual ranges of 8,470–311,646km2 (average 106,613km2), while Beaufort Sea (Canada/Alaska) female ranges are 13,000–597,000km2 (average 149,000km2). Straight-line movements (i.e. minimum estimates) can exceed 50km per day and 6,200km per year. Easily swims 25–40km and capable of extraordinary endurance in water: a monitored Beaufort Sea female swam continuously for 232 hours, covering 687km, in 2–6°C water. Ranges and movements are thought to be similar for both sexes, but males are rarely radio-collared as their neck circumference exceeds their head size.

Reproduction and Demography

Seasonal. Mating March–June. Oestrus duration poorly understood, but mating associations last 2–4 weeks; gestation 195–265 days, with delayed implantation. Cubs born mid-November–mid-January in traditional denning areas near the coast or in drift ice, where snowfall and topography allow excavation of snow dens. Litter size 1–3 (4 exceptionally recorded from captivity), most often 2. Weaning and independence occur together, coinciding with the mother’s next breeding season, normally at 30 months, sometimes at 18 or 42 months, depending on food availability. Inter-litter interval averages 3.1–3.6 years. Both sexes are sexually mature at 3–3.5 years, but earliest breeding is at 4–6 (♀s) and 6–8 (♂s). Reproduction is possible until age 27 (♀s) and over 20 (♂s). MORTALITY Depending on resources, 25–65% of cubs die in their first year, most from starvation. Survival rates increase each year of life until prime adult natural mortality is 1–4%. Adults have no predators except other Polar Bears and humans; male bears are sometimes infanticidal, and Grey Wolves are (rarely) recorded killing young cubs. There are occasional records of Walruses killing bears when attacked. LIFESPAN 32 (♀s) and 29 (♂s) years in the wild, 42 in captivity.

Status and Threats

Total numbers estimated at 20,000–25,000 in 19 relatively discrete subpopulations. Protected by a 5-nation treaty that restricts hunting to indigenous communities (Canada, Alaska and Greenland), or prohibits hunting (Norway/Svalbard and Russia, largely unenforced in the latter, where illegal hunting in E Russia is estimated to kill 100–200 bears a year). Annually, 700–800 bears are legally hunted, most (~500) in Canada, which is also the only range state that permits sport hunting, under the quota to native people. Excessive harvest causes population declines and is a short-term threat in some areas, e.g. in the Chukchi Sea subpopulation (hunted legally in the US and illegally in Russia). Given the species’ strict dependence on sea-ice, global warming is now recognised as the greatest long-term threat; southernmost populations are already impacted by earlier than usual sea-ice thaws, e.g. S Beaufort Sea and W Hudson Bay, and display lowered condition and survival, and escalated conflict with people in their search for food; the former is 1 of 3 (and possibly 5) subpopulations known to be declining. CITES Appendix II; Red List VU, population trend Unknown.

Plate 64