| DINGO Canis lupus familiaris/Canis familiaris |

Includes NEW GUINEA SINGING DOG OR NEW GUINEA

HIGHLAND WILD DOG C. dingo hallstromi/C. hallstromi

HB ♀ 70.3–101cm, ♂ 75–111cm; T 20–37cm; W ♀ 8–17kg, ♂ 7–22kg

The Dingo has been classified as a distinct species, Canis dingo, or a subspecies of the Grey Wolf, C. lupus dingo, i.e. derived from a regional population of Grey Wolves in Asia independently of the lineage leading to the domestic dog (C. l. familiaris/C. familiaris). The New Guinea Singing Dog (named for its distinctive melodic howl; also known as New Guinea Highland Wild Dog) has been classified as both a subspecies of the Dingo, C. dingo hallstromi, and as a full species, C. hallstromi. A recent and comprehensive review, including genetic analyses, concluded that the 2 forms are very closely related and together comprise an ancient breed (or breeds) of domestic dog that likely arose in Southeast Asia perhaps ~10,000 years after the effective genetic separation of domestic dogs from the ancestral Grey Wolf population. Accordingly, from an evolutionary perspective, the Dingo is most correctly regarded as an archaic domestic dog that later became established in the wild. Based on fossil evidence, the Dingo colonised Australia at least 3,500–4,000 years ago, probably in association with humans; there is limited, unresolved genetic evidence that this occurred without human assistance as early as 8,300 bce, when a land bridge connected New Guinea and Australia. Regardless, Australia is now the only place where the Dingo unequivocally lives wild. In New Guinea and Southeast Asia, it is primarily associated with humans, although often in a semi-feral state. Australian Dingoes are approximately the size of a Border Collie; New Guinea Singing Dogs have a shorter body length and shorter legs, giving them a smaller, stockier appearance. Usually tawny ginger; pale sandy, white (not albino) and black-and-tan variants occur. Tail tip and paws are usually white or cream. Sable (Alsatian-like), brindled and piebald coloration typically indicates hybridisation with modern (of European descent) domestic dogs.

Distribution and Habitat

Commensal with humans in S Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, Borneo, Philippines, Sulawesi and New Guinea; wild in Australia, where it inhabits desert, grassland, woodland savannah, wetland, alpine moorland and forest. Occurs in rural habitats, including extensive livestock production areas, and in peri-urban areas provided there is sufficient habitat and prey. Wild populations mostly avoid intensive agriculture, although extensive sugar-cane monocultures with associated bushland are important habitats for peri-urban Dingoes (Queensland).

Feeding Ecology

Very broad diet; 177 prey species recorded from Australia, with mammals comprising around 75% of the diet on average. At least 1 macropod – especially Red Kangaroo, Euro, and Swamp, Agile and Red-necked wallabies – features prominently in the diet across its range. Other important prey includes wombats, brushtail possums, bandicoots, introduced European Rabbit and Magpie Goose. Small rodents, mainly Spinifex Hopping-mouse, Sandy Inland Mouse, Long-haired Rat and introduced House Mouse, dominate the diet of Simpson Desert Dingoes during rodent population irruptions. A very wide variety of other items are opportunistically eaten, usually forming a small proportion of the diet, including birds, reptiles, crocodile and turtle eggs, invertebrates, fruits and seeds. Dingoes on Fraser Island (Queensland) eat mainly small to medium-sized mammals, especially Northern Brown Bandicoot, with relatively high proportions of seeds, fruits and large skinks, as well as marine species hunted and scavenged along the shore. After bandicoot, fish – almost all scavenged from people’s fishing waste – are the second-most common dietary item for Fraser Island Dingoes. They also consume crustaceans and molluscs, and scavenge stranded marine turtles, whales, dolphins, Dugongs and New Zealand Fur Seal. Occasionally cannibalistic. Kills sheep, goats and cattle calves. Foraging is mainly nocturno-crepuscular, but diurnal where the Dingo is free from persecution. Forages alone or socially; large prey such as kangaroos are usually hunted cooperatively in packs, which increases hunting success, e.g. from 5.5% (alone) to 19% (packs) when hunting Red Kangaroos. Scavenges, including from livestock carcasses, human-killed feral animals (especially pigs and deer), human refuse and recreational fishing waste. Peri-urban Dingoes in Queensland eat pet food, but only rarely; diet is mainly natural rather than from human sources.

Social and Spatial Behaviour

Free from persecution, lives in stable packs of 2–12 adults and their pups in enduring home ranges. Territorial, but often shares important resources such as waterholes with neighbouring packs. Breeding is often restricted to the alpha pair, and other pack members help raise pups by provisioning and guarding. Under persecution (around half of its Australian range), social structure may be fractured, so that packs are smaller and less stable. Individuals associate in loose ‘tribes’, sharing a range that is not actively defended, and foraging is mostly solitary. Size of pack territories: 4–55km2 (moist, cool forest) and 32–126km2 (Simpson Desert), to more than 300km2 in Australian desert areas generally.

Reproduction and Demography

Breeding is generally seasonal, most strongly in arid C Australia. Dingoes (including New Guinea Singing Dogs) differ from modern domestic dog breeds in having only a single breeding season per year. Mating period peaks April–June; births peak June–August. Gestation 61–69 days. Litter size 1–10, averaging 5. Most females first breed at around 24 months; males sexually mature at 12 months, but breeding is limited by social dynamics. Females can breed until 11 years (wild). MORTALITY Highly variable depending on the level of human persecution; on average, approximately two-thirds of Dingoes die before 2 years from natural causes (primarily starvation and intraspecific killing, including infanticide). Persecution by people is the next most significant cause of mortality, especially for adults. Occasionally killed by Water Buffalo, Red Kangaroo and Wedge-tailed Eagle (pups). LIFESPAN 13.3 years in the wild, 20 in captivity.

Status and Threats

Widespread in Australia, where it is protected in national parks, World Heritage sites and Aboriginal reserves. Elsewhere, legally regarded as a pest and persecuted, mainly in livestock-producing landscapes, including by state-sanctioned trapping and poisoning. Persecution is intense in some areas, but Dingo populations are very resilient and capable of rapid recovery. Hybridisation from modern (European) domestic dogs threatens the integrity of the ancient Dingo genotypes, worthy of conserving in their own right (even if only for what they might reveal about the early stages of dog domestication). Pure Dingoes are most common in C and N Australia, rare/possibly extinct in S and NE Australia, and probably extinct in SE and SW areas. Without intensive conservation effort, pure Dingo genotypes are unlikely to persist except perhaps on islands (e.g. Fraser Island) or in very remote areas (e.g. Tanami Desert). Red List VU, population trend Increasing overall (including hybrids), purebreds Decreasing.

Plate 43

| GREY WOLF Canis lupus |

TIMBER WOLF, ARCTIC WOLF, TUNDRA WOLF

HB ♀ 87–117cm, ♂ 100–130cm; T 35–50cm;

SH 66–81cm; W ♀ 18–55kg, ♂ 20–79.4kg

The world’s largest canid, with significant variation in size and coloration. Largest individuals (Alaska and Canada) are 3–6 times as heavy as Middle Eastern and S Asian wolves. Typically pale to dark grey, but highly variable, e.g. ginger in E to C Asia (‘Himalayan Wolf’ or ‘Tibetan Wolf’), brown in W to N Eurasia, and white, especially in N Canada (‘Arctic Wolf’). Black coloration is rare outside forested North America, and traces to interbreeding with early domesticated dogs 10,000–15,000 years ago. Grey Wolves hybridise with Coyotes, particularly in areas where Grey Wolves, and hence conspecific mates, are rare. Grey Wolf is the progenitor of the domestic dog, and they can interbreed. Dingo treated here as a domestic dog variant, is sometimes classified as a Grey Wolf subspecies. Twelve Grey Wolf subspecies are described, most on the basis of morphology, which is unreliable. Genetically, the most distinct lineages are the Mexican Wolf (C. l. baileyi); wolves of coastal SE Alaska, usually recognised as C. l. ligoni; and Himalayan Wolves (C. l. himalayensis; Himalayas to Tibetan Plateau), which some scientists treat as a separate species, C. himalayensis.

Distribution and Habitat

North America and Eurasia, formerly one of the most widespread mammals. Widespread in Canada and Alaska, extirpated in the lower USA except in the N Rockies and N Midwest, and relict in SW USA–Mexico, where reintroduction has established 100–110 Mexican Wolves. Widespread in Russia and C Asia, fragmented and reduced in SW Asia, the Middle East, and W and N Europe. Occupies many habitat types, including desert (to 50°C), open plains, steppe, mountainous areas, swamps, forest and Arctic tundra (to –56°C). Although tolerant of habitat modification, rarely inhabits agricultural and pastoral areas due to intense anthropogenic persecution.

Feeding Ecology

Highly opportunistic and proficient pack hunter. Diet varies extensively by region and season, but medium to large ungulates are usually the mainstay, e.g. Musk-ox, bison, Moose, Elk, Red Deer, Reindeer/Caribou, White-tailed Deer, roe deer, wild sheep, ibex and Wild Boar. Juvenile and debilitated individuals are most often killed, but even a single Grey Wolf is capable of killing healthy adults, especially during winter. When ungulates are less vulnerable (spring–summer), the diet is more diverse, with increased consumption of beavers, hares, rodents, waterfowl, fish and fruits. Kills smaller carnivores, especially Coyotes, and occasionally Pumas and young Black Bears (here), Brown Bears and (exceptionally) Polar Bears. Livestock is readily killed, especially during spring–summer, when wild prey disperses and stock occupies productive grazing areas; livestock (including semi-domestic Reindeer) is the most important prey for many Eurasian populations. Unprovoked attacks on humans are very rare and usually attributed to rabies, e.g. 2 fatalities by healthy wolves in North America since 1900. Hunting is cathemeral, with greater diurnalism where it is protected. Hunting is highly social; pack members exchange the lead in chases and cooperatively bring down large prey. Can reach 64km/h and has extraordinary endurance, maintaining pursuit to 8km (with an exceptional record of 21km). Hunting success rates 10–49% for packs (North America). Scavenges, including from refuse dumps and appropriated carcasses from other carnivores.

Social and Spatial Behaviour

Highly social and territorial, living in packs numbering up to 42 but typically 2–15. Nucleus of the pack is a mated adult pair, accompanied by adult offspring. Pack size fluctuates depending on dispersal of offspring, which is affected by food availability. Dispersal is low in productive years, producing large packs with up to 4 generations of grown offspring. Most offspring ultimately disperse and seek non-related adults to form new packs. Recruitment of unrelated individuals (especially to replace a lost breeder) or small groups of dispersers occurs occasionally in established packs. Packs occupy enduring ranges that are usually defended aggressively from other packs. Range size 33–4,335km2, averaging 69–2,600km2. Ranges increase locally during winter and with increasing latitude; largest ranges recorded are from Alaska and the Canadian Arctic. Wolves following migratory herds have massive ranges of 63,000–100,000km2 annually that are not defended. Density estimates 5/1,000km2 (NW Alaska) to 92/1,000km2 (Isle Royale, Canada), but rarely exceeding 40/1,000km2.

Reproduction and Demography

Seasonal. Mating January–April depending on latitude, with pups born March–June. Gestation 60–75 days, typically 62–65. Litter size 1–13, averaging 4–7. Pack’s dominant female is normally the only breeder, although multiple females (probably close relatives) occasionally breed under high prey availability. All pack members help raise pups by provisioning the mother and pups at the den, and by defending pups from predators. Weaning at around 8–10 weeks. Pups leave the den permanently and travel continually with the pack from 4–6 months by September–October. Dispersal is usually at 11–24 months, but is recorded at 5–60 months. Inter-litter interval typically 12 months; 2 litters a year produced on rare occasions. Sexual maturity at around 10 months for both sexes, although breeding opportunities rarely arise before 3 years. MORTALITY Annual pup mortality averages 34%, ranging from 9% (Denali NP, Alaska) to 61% (N Wisconsin). Adult mortality from 14%, to 44% where heavily exploited. Human hunting and trapping are often the main cause; in unexploited populations, starvation (mostly of pups) and aggression from other wolves are the main factors. Disease is an important cause of death, although population effects are poorly known. Wolves occasionally die in hunting accidents and are killed by bears, Puma and Amur Tiger. LIFESPAN 13 years in the wild, 17 in captivity.

Status and Threats

Widespread and stable in most of its northern range, especially in Alaska, Canada, Kazakhstan and Russia (total combined estimate 113,000–127,000 wolves). None the less, it has lost an estimated third of its historic range, mainly in the USA/Mexico, W Europe and S Asia, where it is mostly threatened or endangered. Chief threat is persecution by humans, often as part of state-sanctioned control programmes. Diseases, especially canine parvovirus, mange and rabies produce local declines. Reintroduction of 31 individuals to Yellowstone NP in 1995–96 has been highly successful, growing to approximately 1,900 animals in 6 states in 2016; reintroduction to the SW USA (Mexican Wolf subspecies) has been less successful. Legally hunted and trapped in at least 15 countries, with the largest numbers killed in Canada (4,000 annually), Russia (10,000–20,000 annually) and Mongolia. CITES Appendix I – Bhutan, India, Nepal and Pakistan, Appendix II – elsewhere; Red List LC, population trend Stable.

Plate 44

| COYOTE Canis latrans |

BRUSH WOLF, PRAIRIE WOLF

HB 74–95cm; T 26–46cm; W ♀ 7.7–14.8kg (exceptionally to 25kg), ♂ 7.7–18.1kg (exceptionally to 34kg)

Generally uniformly coloured, from frosted grey to rufous-brown, with pale underparts and often a greyish or ‘salt-and-pepper’ saddle. Tail is typically infused with dark brown to black hairs, and usually dark-tipped (rarely white-tipped). Varies very widely geographically and seasonally; northern and winter individuals are generally larger and paler/greyer. Rufous sides, outer legs and backs of ears are common in eastern and southern (including Central American) individuals. Melanistic, leucistic, brindled, sable (Alsatian-like) and blond individuals occur, particularly in eastern North America, where admixture with domestic dogs is most prevalent (‘Eastern Coyote’).

Distribution and Habitat

N Alaska and Canada (except NE Canada), throughout the USA and Meso-America to Panama. Recorded east of the Panama Canal for the first time in 2013; not confirmed from Colombia (as of 2017). At the time of European settlement, Coyotes were restricted to non-forested W and C North America. Habitat conversion, with a concomitant increase in White-tailed Deer and extirpation of Grey Wolves, fostered their expansion across virtually the entire North American continent and Meso-America in 200 years. Now inhabits virtually all habitat types, from Arctic tundra to deserts, tropical and montane forest, and heavily modified anthropogenic habitats, including all kinds of agricultural land and suburban–urban areas, even in large cities, e.g. Chicago and New York.

Feeding Ecology

Extremely opportunistic generalist that consumes virtually any edible food source. Vertebrate prey is most important, mainly rodents (chiefly squirrels, mice and voles), lagomorphs, juvenile ungulates and carrion. A wide variety of other small to medium-sized mammals are also taken incidentally, including armadillos, Virginia Opossums and mesocarnivores, e.g. Northern Raccoons, Striped Skunks, foxes and Bobcats (probably juveniles). Capable of killing adult large ungulates, including 4 recent records of 2–5 Coyotes killing Moose older than 20 months (Ontario, Canada), but large mammals are rarely killed, and debilitated individuals, such as those weakened in deep snow, are usually targeted. Scavenging of winter- and wolf-killed large ungulates is particularly important to northern populations, e.g. scavenged Moose is the main dietary item in Cape Breton Highlands NP, Canada. Mammalian prey is always supplemented by a wide variety of other food sources, especially fruits, seeds, vegetables, grains (including crops), eggs and invertebrates. Diet varies very widely regionally and seasonally. Coyotes adjust intake of different food types depending on local availability, for example, different fruits including blackberries, wild plum, wild grape, black cherry and persimmon peak at different times in the diet of Coyotes in Longleaf Pine habitat (Joseph W. Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia) as the fruiting season progresses. Birds are typically ancillary prey; waders, shorebirds and waterfowl form a large part of the diet on protected islands off the coast of South Carolina. Coyotes take small livestock (goats, sheep and young calves) and poultry. Domestic pets, especially cats and less so small dogs, are eaten rarely; cats occur in 0–2% of scats collected in urban and suburban studies. Attacks on people are very rare and not as prey; attacks occur most often during the breeding and pup-rearing season, when adults are very defensive. There are 2 recorded human fatalities, a 3-year-old child (California, 1981) and an adult woman killed by a pair (Cape Breton Highlands NP, 2009). Foraging is mainly diurno-crepuscular, but generally nocturnal near humans, particularly where hunted. Usually forages alone, less often in pairs. Where large ungulates are available, Coyotes may hunt socially, usually as pairs or small family groups; typically the alpha pair is responsible for the attack, and younger animals play little part. Sometimes associates with foraging American Badgers, snatching rodents flushed from cover or burrows as the badger digs. Large groups, including non-relatives, congregate relatively amicably at large carcasses. Scavenges, including from carnivore (especially Grey Wolf) kills, human refuse, pet food and bird feeders.

Social and Spatial Behaviour

Sociality is extremely flexible, changing regionally and temporally depending on food availability. Basic social unit is a territorial monogamous pair that may breed for life. ‘Associate’ individuals, usually grown offspring of previous litters, remain with the pair under high food availability, forming packs numbering up to 10. Associates help raise pups and defend territories, although not to the extent of the breeding pair. Large packs occur where ungulates are the main prey, while pairs and trios are typical where prey is small. Some Coyotes never join packs and live as solitary nomads. Average resident territory size (excluding small breeding ranges) 2–3km2 (SW USA) to 42–61km2 (Minnesota). Territories in urban habitats range from 5–36km2 (resident) to 27–115km2 (transient). Density varies very widely, depending on habitat, season, protection and Grey Wolf density, e.g. 1–9/100km2 (Alberta) to 150–230/100km2 (Texas); urban populations reach extremely high densities, e.g. up to 600/100km2 in Chicago.

Reproduction and Demography

Seasonal. Mating January–March, with pups born April–June. Gestation 58–65 days. Maximum litter size 11, averaging 4–7. Pups weaned at 5–7 weeks; dispersal from 6 months. MORTALITY Humans are the main cause of death, mainly from shooting or trapping; collisions with vehicles comprise 35–62% of mortalities in urban areas. Grey Wolf is the chief natural predator. Annual mortality (adults and subadults) is lower in protected and urban populations (20–47%), compared to trapped and hunted populations (50–70%). LIFESPAN 15.5 years in the wild (rarely beyond 8), 18 in captivity.

Status and Threats

Extremely widespread, common and resilient. Coyotes are heavily hunted, trapped and persecuted across much of their North American range, but populations are very resistant to persecution. Official control actions, largely in response to complaints of livestock depredation, killed more than 77,000 Coyotes in the USA in 2016. Very tolerant of habitat modification; deforestation to open habitat actually favours Coyotes. Combined with extirpation of Grey Wolves (the main natural predator and competitor), such habitat conversion has enabled colonisation outside its historic range, e.g. E Canada, E USA and E Central America, which continues today. Red List LC, population trend Increasing.

Plate 45

| GREY WOLF–COYOTE HYBRIDS |

The canids depicted opposite have all been (and sometimes still are) classified as discrete species in eastern North America. Recent (2016) compelling genetic evidence indicates that all are hybrid populations of Coyote and Grey Wolf. The analysis suggests that Coyotes and Grey Wolves diverged from a common ancestor very recently, within the last 117,000 years, making them sufficiently closely related to interbreed occasionally and produce fertile offspring. The amount of admixture correlates with Grey Wolf declines in eastern North America following European colonisation; this opened up the large canid niche to Coyotes and allowed them to expand eastward into the void. Faced with reduced opportunities for reproduction, remaining Grey Wolf individuals mated with Coyotes, and their fertile hybrid pups formed part of an expanding Coyote population that rapidly colonised former Grey Wolf distribution. Accordingly, continuous, large populations of Alaskan Grey Wolves almost never hybridise, and average 8–8.5% Coyote ancestry. Wolves from Algonquin Provincial Park, Ontario, thought to be pure Eastern Wolf (see below), actually have 32.5–35.5% Coyote ancestry, while Red Wolves in CE USA (see below), where human pressures on Grey Wolves were early, intense and sustained, have 70–80% Coyote ancestry – they are now more Coyote than Grey Wolf.

Coyotes and Grey Wolves continue to exchange genetic material today, although hybridisation is most prevalent where and when wolf persecution is intense and Coyote populations expand; there is little evidence of ongoing hybridisation in some populations with mixed ancestry where persecution has relaxed. Wolves of the western Great Lakes region are recovering from historic low numbers around a century ago, when their Coyote ancestry (21.7–23.9%) is assumed to have largely arisen. Great Lakes Grey Wolves today are not limited in mating opportunities with other Grey Wolves (strictly speaking, mostly Grey Wolf, from a genetic perspective), and are more likely to kill Coyotes rather than breed with them.

Grey Wolf–Coyote hybrid populations not only reveal the intriguing challenges in defining species (see the box ‘How many species of carnivores?’); they also present a quandary for conservationists. Does having mixed ancestry mean they do not warrant conservation efforts? They are fascinating in their own right and have similar aesthetic and ecological value to ‘true’ species. They fulfil an important regulatory role as the major predators of super-abundant White-tailed Deer, a species that causes hundreds of human deaths and tens of thousands of injuries through road accidents, as well as an estimated US$3.5 billion in damage to crops, nursery plants and tree seedlings each year across eastern North America. Medium-sized wolf-like canids such as the Red Wolf and Eastern Coyote defy traditional categorisation as species, yet they are better suited to modern anthropogenic eastern North America than the original Grey Wolf occupants, which need vast wilderness areas with very large ungulate prey.

| EASTERN COYOTE Canis latrans var. (Canis ‘oriens’) |

See Coyote for species account

Advocates have proposed that the Coyote in NE North America warrants recognition as a unique species, Canis ‘oriens’ (often referred to as ‘Coywolf’), with little validity. Eastern Coyotes tend to be larger than western Coyotes, but there is continuous variation in size from west to east; they are not significantly genetically differentiated nor reproductively isolated from western or southeastern Coyotes. The Eastern Coyote is essentially a Coyote with some Grey Wolf genes that, in the absence of competing Grey Wolves, has undergone natural selection for a slightly larger ecotype to exploit White-tailed Deer more effectively. As well as having Grey Wolf ancestry, Eastern Coyotes have hybridised with domestic dogs. All sampled individuals are mainly Coyote, with some that have almost no Grey Wolf genes, but none is exclusively Coyote, and none completely lacks dog genes. The mix of genes gives rise to wide morphological variation, including coat colour variants such as brindled, sable (Alsatian-like) and blond (depicted opposite), rarely seen in other populations.

| RED WOLF Canis ‘rufus’ |

HB ♀ 99–120cm, ♂ 104–125cm; T 30–46cm; SH 66–76cm; W ♀ 16–30kg, ♂ 21–41kg

The Red Wolf’s status is controversial. There is ongoing debate over whether hybridisation was pre-historic (~10,000 bce) or since European colonisation; and some taxonomists suggest it is not a hybrid but instead evolved very recently from a common ancestor with the Coyote. Regardless, its biological profile – updated from the first edition of this book – is included here to provide ecological data broadly representative of the canid hybrid populations now inhabiting eastern North America.

Reddish fur, becoming pale ginger to cream on the lower limbs, and distinctive white throat and chest patches. Distribution and Habitat Extinct in the wild except for a reintroduced population occupying 6,000km2 in E North Carolina, USA, which inhabits pine forest–wetland mosaics, marshland and agricultural land with cover. Feeding Ecology Eats mainly White-tailed Deer, raccoons, Marsh Rabbit and small rodents. Livestock is eaten, although recent records are all of carrion. Hunting is nocturno-crepuscular, and usually in small packs or singly. Social and Spatial Behaviour Forms small family packs of 2–12 animals, comprising a dominant breeding pair and its offspring. Packs are territorial and occasionally kill unrelated intruders. Females disperse at higher rates than males, and some individuals never disperse, remaining in the pack as non-breeding helpers. Resident pack range size averages 68.4km2 (range, 25–190km2); ranges for transients are much larger, average 319km2 (range, 122–681km2). Reproduction and Demography Seasonal. Mating February–March; births April–May. Gestation 61–63 days. Litter size averages 3–5, exceptionally to 10. MORTALITY Rates low for canids: 32% (pups), 21% (yearlings) and 19% (adults) annually. Shooting and roadkills are the main causes; natural deaths account for a quarter of the total, mainly from intraspecific killing, sarcoptic mange and starvation (of pups). LIFESPAN 20 years in captivity. Status and Threats Treated as an endangered species by the US government and declared Extinct in the Wild by 1980. Reintroduced from captivity in 1987 and formerly numbered up to 130; there are currently fewer than 50 in the wild, including pups (2018). Humans are the main threat. Given recent genetic data, its conservation status is uncertain; it is still (2018) treated as a distinct species by the US Fish and Wildlife Service. Red List CR, population trend Decreasing.

| EASTERN WOLF Canis lupus var. (Canis ‘lycaon’) |

See Grey Wolf for species account

The Eastern Wolf has been variously classified as a distinct species, Canis ‘lycaon’, the same species as Red Wolf, a hybrid between Red Wolf and Grey Wolf, or (as in this book) a Coyote-admixed population of the Grey Wolf. Historically, its range was defined as S Quebec and Ontario, centred on Algonquin Provincial Park, although this is contiguous with Grey Wolf distribution across E Canada. Algonquin Provincial Park wolves have historically been heavily hunted by people (including official culling programmes as recently as the 1960s; they have been protected since), and wolves are legally hunted and trapped throughout the area considered Eastern Wolf range. Resulting hybridisation with Coyotes is typical of heavily hunted wolf populations; this declines along a cline north and west into more continuous and less hunted Grey Wolf range in Canada.

Plate 46

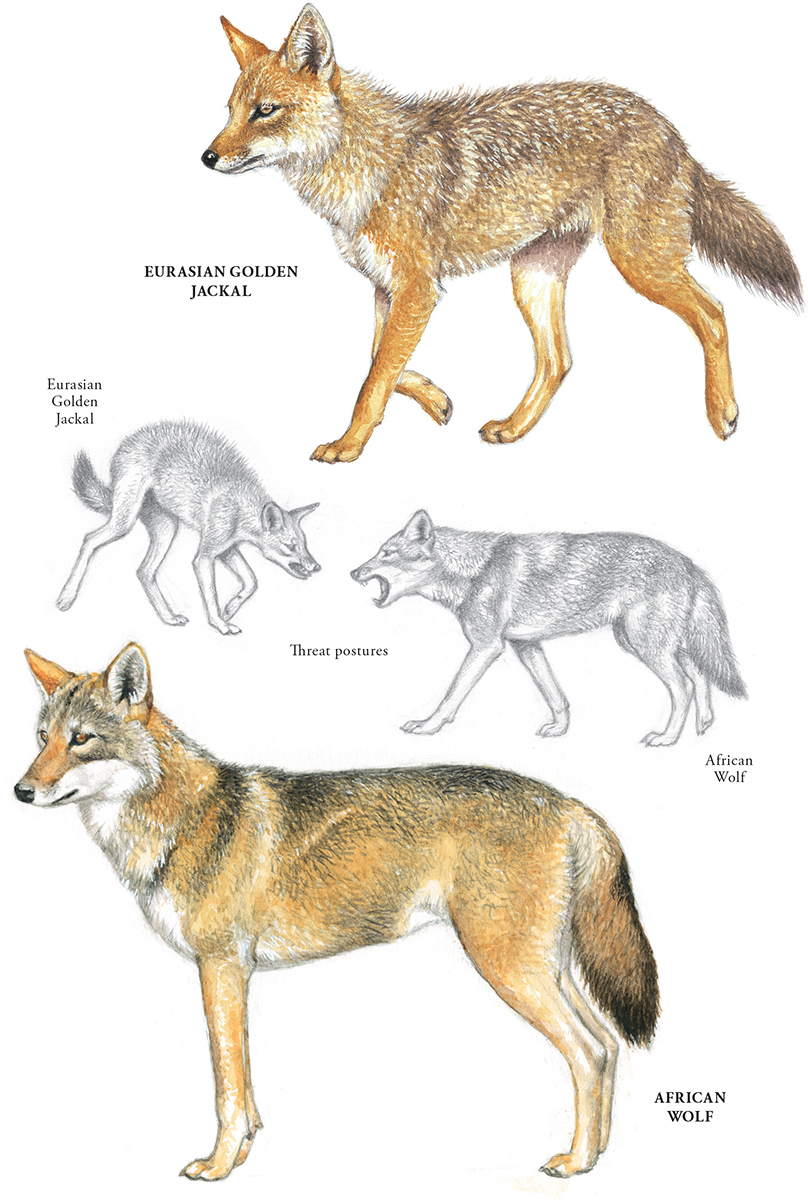

| EURASIAN GOLDEN JACKAL Canis aureus |

GOLDEN JACKAL, ASIATIC JACKAL, INDIAN JACKAL, COMMON JACKAL

HB ♀ 69–85cm, ♂ 70–90cm; T 20–38cm; SH 35–48cm; W ♀ 4.9–13.6kg, ♂ 6.7–14.5kg

The only jackal in Eurasia. Until 2011, it included the species now classified as the African Wolf. It is now uncertain whether the Eurasian Golden Jackal occurs anywhere in Africa; there is a possible hybrid zone from Egypt to Israel. Uniformly tawny grey to greyish brown, without discrete markings except a greyish mantle in some populations; bushy tail usually has a dark tip (never white). Melanism occurs very rarely and may be the result of hybridisation with domestic dogs. Distribution and Habitat Arabian Peninsula to SE Europe, and C Asia to Indochina; may occur in Egypt. Inhabits semi-desert, grassland, dry woodland, forest, and agricultural and semi-urban areas. Feeding Ecology Omnivorous, eating mainly rodents, hares, lizards, snakes, invertebrates, fruit, seeds, mast and vegetable matter, including crops. Small fawns e.g. of Chital and rarely to Sambar size, are taken. Birds are usually ancillary prey but dominate diet locally or seasonally, e.g. mostly migratory egrets, Garganey and coucals are the main winter prey in Patna Bird Sanctuary, India. Jackals inhabiting a mangrove island in the Gulf of Kachchh, India, eat almost exclusively crabs and fish. Takes small stock and poultry, these dominating the diet (kills and carrion combined) in some sites, e.g. Greece and Israel. Foraging is mainly nocturnal, and crepuscular/diurnal where protected. Hunts singly, in adult pairs or in small family groups. Caches surplus food in shallow holes, and scavenges: congregations of up to 18 adults are recorded at large carcasses and in dumps. Social and Spatial Behaviour Breeding pair is the main social unit, often accompanied by grown helpers from previous litters. Pairs are usually formed during the breeding season, but persist year-round under high food availability. Pairs defend a core territory centred on dens, and may defend larger territories under high food availability. Territories 3–30km2 (India). A collared female in Thailand occupied 151km2 in mostly agricultural habitat. Densities 0.1–1.5/km2 (Greece, Hungary, Romania) to 15/km2 (very high prey availability, with no large carnivores, Keoladeo NP, India). Reproduction and Demography Seasonal; births often coincide with peak food supply, such as birth flushes of ungulates or rodents, e.g. December–May (Israel) and April–June (India, C Asia). Gestation 63 days. Maximum litter size 8, typically 3–6. MORTALITY Poorly known; sometimes killed by large cats, Grey Wolf and domestic dogs. LIFESPAN 16 years in captivity. Status and Threats Generally common and widespread. Slowly declining outside protected areas in some countries, but expanding range in Europe (possibly due to historic Grey Wolf declines), most recently into Austria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Germany, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Switzerland. Very tolerant of human activities and converted landscapes, but disappears under agricultural intensification (often with associated use of poisons) and urbanisation. Vulnerable to transmission of disease, especially rabies and distemper by feral dogs in anthropogenic landscapes. CITES Appendix II – India; Red List LC, population trend Increasing.

| AFRICAN WOLF Canis lupaster |

AFRICAN GOLDEN WOLF, GOLDEN WOLF

HB ♀ 74–100cm, ♂ 76–105cm; T 20–26cm; SH 38–50cm; W ♀ 6.5–14.5kg, ♂ 7.6–15.5kg

Prior to 2011, misclassified as a Golden Jackal subspecies. Morphological and genetic analyses has shown that the canid previously assigned to Golden Jackal in Africa is a distinct species, Canis lupaster (sometimes called C. anthus), which is more closely related to Grey Wolf. Western and northern African Wolves are larger, more variable in appearance, and tend to be more ‘wolf-like’ than E African individuals, which closely resemble Eurasian Golden Jackal. Yellow-grey to greyish brown, with pale underparts, breast shield and throat, often with a greyish mantle, and russet or ginger undertones on upperparts. Tail is usually interspersed with blackish hairs, especially dorsally, and has a black tip (never white). Distribution and Habitat Former distribution of Golden Jackal in Africa is now assumed to be African Wolf range: N Tanzania to Senegal, throughout C, W and N Africa. Very wide habitat tolerance; inhabits semi-desert, grassland, woodland, forest, and agricultural and semi-urban habitats. Penetrates deeply into very arid habitat in the Sahara, where it is associated with massifs, vegetation or the presence of livestock. Recorded from sea-level to 3,800m (Bale Mountains, Ethiopia). Feeding Ecology Omnivorous and highly opportunistic, with a broad diet. Capable of killing ungulates to the size of adult Thomson’s Gazelle, but most kills are of small vertebrates to the size of hares. Common prey includes mice, rats, mole rats, gerbils, cane rats, ground squirrels, hares, reptiles, birds and eggs. In Algeria, Wild Boar comprises 20% (Djurdjura NP) to 41% (Tlemcen HR) of diet by biomass, presumably mainly scavenged although piglets may be hunted. Barbary Macaque, Dama Gazelle, Red Fox and domestic cat are also recorded from scats in Algeria. Invertebrates, especially dung beetles, grasshoppers, locusts, termites and larvae, are readily consumed. Eats fruit, seeds and vegetable matter, including cultivated crops. Takes small stock; Ethiopian pastoralists in the Guassa highlands consider it to be the main livestock predator, mainly of sheep, although dietary analysis found sheep to be only rarely consumed. Foraging is mainly nocturnal, especially where persecuted, but frequently crepuscular/diurnal where protected. Forages singly or in small family groups; larger prey is more often taken by groups. Caches surplus food in shallow diggings, and scavenges from carcasses and human refuse; individuals in Ethiopian montane farmlands take rodents caught in human hunters’ traps. Congregates at large carcasses and in dumps. Social and Spatial Behaviour Known mainly from E Africa (especially Serengeti NP, Tanzania), when studied as Golden Jackal. Breeding pair is the main social unit, often accompanied by grown helpers from previous litters. Pairs typically form during the breeding season, but persist year-round in good conditions. They defend a core territory around dens, and may cooperate to establish larger territories, depending on food availability. Territory size 1.1–20km2, with densities of up to 4/km2 (Serengeti NP). Densities in Guassa highlands are 0.03/km2 (natural bushland) to 0.31/km2 (human dump site). Reproduction and Demography Seasonal, with births coinciding with peak food supply, e.g. December–April (E Africa). Gestation 63 days. Maximum litter size 8, typically 3–6. MORTALITY Poorly known; sometimes killed by Lions, Leopards and domestic dogs. Humans are likely the main cause of mortality for many populations; Ethiopian pastoralists (Guassa highlands) kill them by plugging den entrances with stones. LIFESPAN 16 years in captivity. Status and Threats Generally common, although declining outside protected areas, where persecution is intense. Very tolerant of human activities and prospers in livestock and farming areas despite often high levels of persecution. They have been extirpated where poisoning (usually illegal) occurs. Red List NE, population trend Unknown.

Plate 47

| DHOLE Cuon alpinus |

ASIATIC WILD DOG

HB 80–113cm; T 32–50cm; SH 42–55cm; W ♀ 10–17kg, ♂ 15–21kg

Superficially resembles a large jackal. Pale tawny brown to rich russet-brown with a dark-tipped tail. Northern temperate individuals are usually more reddish, with contrasting bright white underparts. Distribution and Habitat W and S China, Nepal, Bhutan, India, Southeast Asia, Sumatra and Java; patchily distributed in N China; uncertain in SE Russia and C Asia, where there are no confirmed records for >30 years. Inhabits forest, forest–grassland mosaics and montane scrubland. Avoids open habitat, and agricultural and pastoral areas. Feeding Ecology Pack hunter that mostly kills ungulates, with Chital, Red Muntjac and Sambar preferred across much of its range; also Blackbuck, Nilgai, Swamp Deer, Gaur, Asiatic Buffalo, Banteng, Blue Sheep, Markhor, Himalayan Tahr, gorals and Wild Pig. Juveniles are often selected, but packs are capable of killing adults of all but the largest species. Large Indian Civet was a preferred prey species during a short-term study in Salakpra WS, Thailand. Livestock is sometimes killed, especially when unguarded and where natural prey is depleted. People in SE Thailand blame Dholes for most losses of free-roaming poultry, possibly due to confusion with Eurasian Golden Jackals. Foraging is usually diurno-crepuscular and cooperative. Scavenges, including kleptoparasitism from other carnivores, e.g. Leopard. Social and Spatial Behaviour Lives in packs of 2–15 adults and their pups, exceptionally totalling 30 individuals. Packs have a dominant breeding pair and are biased towards males because females disperse more often. Packs occupy defined home ranges, though the extent of territorial defence is unknown. Pack range estimates (telemetry) 12–49.5km2 (mixed evergreen forest, Phu Khieo WS, Thailand) and 26.1–202.8km2 (dry forest, Pench NP, India). A pack of 6 in lowland forest used 100km2, as estimated by camera-traps (Khao Ang Rue Nai, Thailand). Reproduction and Demography Seasonal. Breeding October–April (India) and January–May (Java). Gestation 60–63 days. Litter size 4–12. Breeding usually restricted to the dominant pair, although multiple females occasionally breed and subordinate males sometimes mate with the alpha female. Pack members assist reproduction by guarding, provisioning at the den and regurgitating food to pups. A monitored pack in Baluran NP, Java, denned in burrows on steep slopes with dense vegetation and moved pups to new dens every 2 weeks on average. MORTALITY Poorly known; Tiger and Leopard are known predators. LIFESPAN 16 years in captivity. Status and Threats Endangered and declining, chiefly from persecution, habitat loss and prey declines due to human hunting. Extirpated from at least 75% of former range. Likely extinct in its former E and C Asian range, and in Southeast Asia restricted to large protected areas. S and C India is the species’ stronghold, where it reaches high densities in small protected areas; reasonably tolerated in non-protected areas, where it is generally not significantly involved in conflict with humans or hunted for illegal trade of body parts. CITES Appendix II; Red List EN, population trend Decreasing.

| ETHIOPIAN WOLF Canis simensis |

SIMIEN JACKAL, ABYSSINIAN WOLF, SIMIEN FOX

HB ♀ 84.1–96cm, ♂ 93–101.2cm; T 27–39.6cm; SH 53–62cm; W ♀ 11.2–14.2kg, ♂ 14.2–19.3kg

Rich tawny rufous with white underparts and bright white markings on the lower face, throat, chest and lower legs. Tail has a white base, darkening to a chocolate-brown tip. Hybrids with domestic dogs have a stockier build and lighter, duller coat. Despite its confusing array of common names, the species is most closely related to Coyote and Grey Wolf. Distribution and Habitat Restricted to 7 isolated populations at 3,000–4,500m in Ethiopia. Inhabits open highland habitats, especially montane grassland, heath and shrubland. Avoids agricultural areas, which reach 3,500–3,800m in parts of its range. Feeding Ecology Feeds almost exclusively on small diurnal mammals, especially mole rats, rats and Starck’s Hare. Infrequent prey includes Rock Hyrax, juvenile Grey Duiker, reedbucks and Mountain Nyala, as well as birds such as Blue-winged Goose juveniles and francolins, and their eggs. Foraging is largely diurnal and solitary, with most kills made by individual wolves stalking rodents or digging them from burrows. Small packs of 2–4 sometimes cooperatively pursue prey, especially hares and young antelopes. Rarely kills sheep lambs; does not kill cattle calves, and often forages among herds and Gelada Baboon troops, which may assist hunting by providing cover and flushing rodents. Appropriates kills from raptors and scavenges, including from livestock carcasses. Caches surplus food in shallow holes. Social and Spatial Behaviour Forms packs of 2–13 adults that defend small, stable territories from other packs. Pairs or small packs occur where prey availability is low. Males rarely disperse, so packs contain up to 8 related adult males, as well as 1–3 adult females that may or may not be related; some females remain in their natal pack, while others disperse for breeding opportunities. Average territory size ranges from 6km2 in productive habitat to 13.4km2 in poor habitat. Estimated densities include 0.1–0.25/km2 in poor habitat or unprotected areas, to 1–1.2/km2 in optimum protected habitat. Reproduction and Demography Seasonal. Mating August–November; births October–January. Gestation 60–62 days. Litter size 2–6. Reproduction is largely by the pack’s alpha pair, but the dominant female also mates with visiting males from neighbouring packs. All pack members provision pups at the den, and subordinate females sometimes assist in suckling (it is unclear if extra nursing females are pseudo-pregnant or absorb/abandon their own litters). Pups weaned from 10 weeks, and accompany the pack from 6 months. Sexual maturity at 18–24 months. MORTALITY Most mortality is anthropogenic and natural factors are poorly known; predation has not been observed, but may occur on pups by Spotted Hyaena, African Wolf and large eagles. LIFESPAN 12 years in the wild. Status and Threats Endangered, with approximately 360–440 adults (>1 year old), of which <250 are breeding adults in 7 disjunct populations. Extreme pressure on habitat for agriculture and livestock is the chief threat, combined with exotic disease, especially rabies and distemper, from domestic dogs. More than half of the remaining Ethiopian Wolves live in the Bale Mountains, where numbers have declined by ~30% since 2008 (to approximately 210 adults >1 year old) due to successive disease epidemics. Roadkills, persecution and hybridisation with domestic dogs (mainly in the Bale Mountains) are lesser threats. Red List EN, population trend Decreasing.

Plate 48

| AFRICAN WILD DOG Lycaon pictus |

PAINTED DOG, CAPE HUNTING DOG

HB 76–112cm; T 30–42cm; SH 61–78cm; W ♀ 17–26.5kg, ♂ 21–36kg

Africa’s largest canid, with coarse fur coloured a mottled patchwork of tawny, black and white. Tail has a conspicuous white tip, extending variably along the length; some individuals have an entirely white tail. Very rarely, the tail is tipped black. Coloration varies very widely within and between populations; southern African individuals tend to be tawnier, while E and NE African animals tend to be darker, but colour is not reliable for identifying origin. Coloration is unique to each individual, allowing identification for life. Little sexual dimorphism; males are slightly heavier than females and recognisable by a prominent penile sheath. There is little regional variation in size.

Distribution and Habitat

Sub-Saharan Africa, mainly in E and southern Africa, with scattered populations across Sahelian W and C Africa. Reaches highest densities in woodland savannah, but occurs widely in open grassland, semi-desert and scrubland. Absent from C African forest, but inhabits forest patches in E Africa. Penetrates deeply into true desert, but cannot permanently colonise very arid areas. Tolerant of habitat modification, but rarely inhabits pastoral landscapes due to intense persecution.

Feeding Ecology

Highly efficient pack hunter capable of taking prey as large as adult zebras and female African Buffaloes, but mostly kills medium-sized antelope species; each population focuses on 1–2 of the most common locally available species. Typical prey includes Impala, Nyala, Red Lechwe, Thomson’s Gazelle and Blue Wildebeest (usually to subadult size). Largest preferred prey is Greater Kudu, in which adult females (135kg) are commonly killed (Namibia). Able to switch to smaller prey, especially where large species are absent or in low numbers, e.g. outside protected areas in N Kenya, Kirk’s Dik-dik (3–7kg) comprises 70% of prey. Bushbuck, duikers, Steenbok and Warthog are also important prey in some areas. Opportunistically kills smaller prey, including hares, small carnivores (e.g. Bat-eared Fox) and reptiles, but these form an insignificant proportion of the diet. Kills small livestock, but depredation is rare where wild prey is available, even when it is heavily outnumbered by stock. No records of predation on humans. Hunting is almost always diurnal and highly social, often preceded by a frenzy of greeting between pack members. Reaches speeds of 66km/h and has terrific endurance, with chases extending for 2km. Hunts are highly coordinated and cooperative; pack members fan out and run in relays to maximise opportunities for capture, sometimes yielding more than 1 kill per hunt. Prey is killed cooperatively, usually by many pack members after capture by 1 dog; large and dangerous prey, e.g. Warthog and wildebeest, is often restrained by the head while other dogs disembowel and dismember it. Although this appears cruel (contributing to pastoralists’ hatred for the species), the prey usually dies within 2–4 minutes. Hunts have high success rates, 42–70%, which increase with the number of adults present. Occasionally scavenges, including appropriating carcasses from other packs, Leopard, Spotted Hyaena and (very rarely) Lion.

Social and Spatial Behaviour

Intensely social, with pack members in almost constant association. Packs form around the dominant breeding pair, with up to 28 adults, but normally average 5–10 adults accompanied by yearlings and pups; the pack size occasionally exceeds 50, including pups old enough to travel. Same-sex adults in the pack are usually related to one another but not to opposite-sex adults. Packs usually form through interchange of same-sex subgroups, typically dispersing littermates that join opposite-sex subgroups. Both sexes may disperse, with females dispersing sooner but settling nearer to their natal range than males. Occupies enduring defined ranges that are often very large and overlap those of other packs. Active territorial defence is infrequent, but occurs in overlapping areas and around den sites, where inter-pack encounters are aggressive and sometimes fatal. Range size 150–2,460km2, averaging 423–1,318km2 and dropping to 50–260km2 when young pups are in the den. Due to its wide-ranging behaviour, the species naturally occurs at low densities that fluctuate significantly depending on pup survival, e.g. 5/1,000km2 (semi-arid savannah, N Botswana), 2.8–22.5/1,000km2 (dry savannah, N Kruger NP), 16–24/1,000km2 (Selous GR, Tanzania) and 19–39/1,000km2 (mesic woodland, S Kruger NP).

Reproduction and Demography

Weakly seasonal. Pups born year-round, but most litters coincide with peak prey availability, e.g. March–June (Serengeti NP, Tanzania) and April–September (Kruger NP). Gestation 69–73 days. Litter size typically 10–11, exceptionally to 21. Pack’s dominant female is usually the only breeder. All pack members cooperate to help raise pups by provisioning the mother at the den, regurgitating food to the pups and guarding the den. Helpers are essential for raising litters, and small packs (<4 adults) rarely reproduce successfully. Subordinate females occasionally breed, but their pups survive only when prey availability is high (they are sometimes ‘stolen’ and raised by the dominant female); otherwise, they are frequently killed by the dominant female or die from starvation brought about by harassment of subordinate mother(s). Weaning is at around 8 weeks, and pups emerge from the den at around 12–16 weeks, after which they travel with the pack. Dispersal occurs most often at around 21–22 months for females (range 13–31), and 28 months for males (range 17–43). Inter-litter interval averages 12–14 months. Sexual maturity is at around 2 years for both sexes, but breeding usually occurs with social dominance at around 4–5 years. MORTALITY 25% (Selous GR) to 65% (Kruger NP) of pups die in their first year. Adult mortality 23–28% for prime adults, rising to around 50% for older adults. Main natural causes are Lions, other African Wild Dogs and infectious diseases such as rabies and canine distemper. LIFESPAN 11 years in the wild, 16 in captivity.

Status and Threats

The species has undergone a drastic loss of range and is now extinct in at least 25 of 39 original range countries. Total numbers are estimated at 6,600 adults in 39 subpopulations, of which only 1,400 are mature individuals. African Wild Dogs were actively destroyed by wildlife managers until the 1970s; they are now protected throughout their range, although anthropogenic factors overshadow natural deaths, even in protected populations. Persecution, incidental killing in snares, roadkills and exotic disease transmitted by domestic dogs are the main causes of death. The species now persists predominantly in areas with large parks. The main strongholds are the Okavango–Kaudom–Hwange ecosystem, Kafue NP and Luangwa Valley, Zambia; Selous GR–Mikumi NP and Ruaha–Rungwa ecosystems, Tanzania; and Kruger NP, South Africa). Red List CR in W Africa and N Africa (Algeria only, if not already extinct there), EN elsewhere, population trend Decreasing.

Plate 49

| BLACK-BACKED JACKAL Canis (Lupulella) mesomelas |

SILVER-BACKED JACKAL

HB ♀ 66–85cm, ♂ 69–90cm; T 27–38cm; SH 38–48cm; W ♀ 5.9–10kg, ♂ 6.4–11.1kg

Recent molecular analyses show that the 2 African jackal species are not closely related to Eurasian Golden Jackal, as formerly thought. Indeed, they diverged early (estimated ~3.5 million years ago) from the lineage that gave rise to the Canis clade of large, wolf-like species (see here) and may warrant being grouped separately within a distinct genus, Lupulella (adopted by some authorities). African jackals are most closely related to the African Wild Dog, and are not closely related to other Canis species. Black-backed Jackal is recognisable by its dark-edged silver-grey saddle on a buff to rufous-brown body, and grizzled, dark bushy tail. Pups show adult coloration, including saddle and dark tail, from a very young age (compare with Side-striped Jackal pups). Melanism is not recorded. Usually the most conspicuous jackal where it occurs, due to preference for open areas and aggressive dominance over other similar-sized canids. Distribution and Habitat Two disjunct populations, in southern and E Africa. Occurs in true desert, grassland, montane meadows, arid to mesic woodland savannah, and agricultural habitats. Recorded from sea-level to 3,660m (Mt Kenya, Kenya). Feeding Ecology Generalist omnivore. Recorded killing adult Springbok, Thomson’s Gazelle and Impala, but typical prey includes rodents, Springhare, hares, and young or small ungulates, especially ‘hider’ species such as Bushbuck and Grey Duiker. Juvenile Cape Fur Seals are readily killed by coastal-living jackals near seal colonies. Birds, reptiles, eggs, invertebrates and carrion are also important food items. Readily takes poultry and small livestock. Foraging is mainly nocturnal, especially where it is persecuted, but often crepuscular/diurnal where it is protected. Usually forages alone or in pairs, but up to 12 adults cooperate to kill large prey, and large congregations gather relatively amicably at carcasses and in food-rich patches like seal colonies. Readily scavenges, including from large carnivore kills and human refuse; caches food for later. Social and Spatial Behaviour Monogamous and territorial, forming breeding pairs that may endure for life and defend territories from other pairs. Up to 3 helpers accompany a pair and help to raise pups, including regurgitating food for them and the mother. Coastal Namibian jackals commute up to 20km from their territories to feed at a fur seal colony (Cape Cross Seal Reserve) along shared ‘highways’. Commuters avoid and are tolerated by territorial residents as they travel, and residents mostly abandon territorial defence at the colony itself except during the denning period. Territories range from an average of 1.0km2 (Hwange NP, Zimbabwe) to 24.9km2 (coastal Namibia). Densities peak during the breeding season, e.g. 0.5–0.8/km2 (non-breeding) to 0.7–1/km2 (breeding; Hwange NP). Density estimates 40/100km2 (Giant’s Castle GR, South Africa), 62/100km2 (Kalahari, possibly applying only to riverine areas) and as high as 220/100km2 (Cape Cross Seal Reserve, representing density only in the area of the seal colony). Reproduction and Demography Seasonal. Mating May–August; births June–November. Gestation ~60 days. Maximum litter size 6, typically 3–4. Pups weaned at 8–9 weeks. Sexually mature at 11 months. MORTALITY Predators include Leopards, Lions, Spotted Hyaenas and, occasionally, Cheetahs and African Wild Dogs. Very susceptible to domestic dog diseases (especially rabies) near settlements, although populations recover quickly. LIFESPAN 14 years in captivity. Status and Threats Widespread and common in protected and pastoral areas. Persecuted intensely on farmland (especially in southern Africa), but is very resilient, and anthropogenic population declines appear to be only temporary. Red List LC, population trend Stable.

| SIDE-STRIPED JACKAL Canis (Lupulella) adusta |

HB ♀ 65–76cm, ♂ 66–81cm; T 30–41cm; SH 41–48cm; W ♀ 6.2–10kg, ♂ 5.9–12kg

Grizzled buff-grey, with a characteristic pale stripe (often outlined with a dark border) along the flanks and a distinctive white-tipped dark tail. Pups are typically uniformly buff-grey without obvious body markings, except for obvious white-tipped tail, until >5–6 months old. Melanism is not recorded. Distribution and Habitat Southern, W and C Africa; replaced by Black-backed Jackal in arid southern Africa, and African Wolf in arid N Africa. Inhabits wooded grassland, woodland savannah, marshland, montane areas and forest edges. Uses more open natural habitats, e.g. open grasslands, in the absence of Black-backed Jackals and African Wolves. Avoids very open habitat but can utilise agricultural areas with cover, and occurs in peri-urban and urban areas near major cities. Feeding Ecology The most omnivorous and least predatory jackal species, rarely killing prey larger than gazelle fawns. Diet varies widely locally and seasonally; mainly includes a wide range of fruits, seeds and crops, as well as small rodents, hares, Springhare, small birds, insects and carrion. Free-range poultry is sometimes killed. More strictly nocturnal than other jackals, perhaps to reduce competition with Black-backed Jackal, but becomes crepuscular when unmolested. Forages alone, but family groups gather at rich patches such as termite nests, and up to 12 from various families congregate to scavenge from carrion or dumps. Social and Spatial Behaviour Monogamous, forming mated pairs that may be lifelong. Resident pairs maintain exclusive use of a core territory, with edges shared by neighbouring pairs. Yearling offspring often remain in the territory, sometimes forming groups of up to 7 with the resident pair, although it is unclear if they act as helpers. Range size 0.15–0.56km2 outside breeding, expanding to 0.55–1.6km2 during breeding. Density estimates 7/100km2 (depleted savanna, Niokolo-Koba NP, Senegal) and 54–79/100km2 (W Zimbabwe) in non-breeding season, to 97/100km2 (W Zimbabwe) in breeding season. Reproduction and Demography Seasonal. Mating June–July; births August–November. Gestation 57–60 days. Litter size 4–6. Pups weaned at 8–10 weeks. Sexually mature at 11 months. MORTALITY Preyed on by larger carnivores, including domestic dogs near human habitation. Vulnerable to diseases such as rabies and canine distemper. LIFESPAN 10 years in captivity. Status and Threats Widespread and common. Tolerant of habitat conversion, and persists in suburban and agricultural habitats. Persecuted in human-dominated areas as a livestock predator, and many are killed by snares and vehicles, but human-caused deaths probably produce only local declines unless they are associated with poisoning or disease outbreaks. Thought to be expanding in some areas, e.g. NE South Africa, where Black-backed Jackals are heavily persecuted. Red List LC, population trend Stable.

Plate 50

| ARCTIC FOX Vulpes lagopus |

POLAR FOX, WHITE FOX, BLUE FOX

HB ♀ 50–65cm, ♂ 53–75cm; T 25–42.5cm; W ♀ 3.1–3.7kg, ♂ 3.6–6.7kg

The northernmost canid and the only canid species to change colour seasonally. Two distinct colour morphs: white winter morph moults to grey-brown with cream underparts in summer; blue morph is pale bluish brown in winter and dark grey-brown in summer. White morph is more common, but blue dominates on islands and in coastal areas. Distribution and Habitat Circumpolar in the Arctic. Restricted to Arctic and tundra habitats, mostly north of the treeline in Canada, the USA (Alaska), Greenland, Russia, Finland, Norway, Sweden and Iceland. Inhabits most Arctic islands and winter sea ice to within 60km of the North Pole. Feeding Ecology Small rodents, chiefly lemmings and voles, are critical, especially to inland populations, which fluctuate with rodent ‘boom-bust’ cycles. Other food includes fruits, eggs, birds to the size of geese, ground squirrels, Arctic Hare and infrequent kills of Reindeer/Caribou neonates. Coastal foxes also eat molluscs, crabs, fish, seabirds, and the carcasses of seals and whales; sometimes kills Ringed Seal pups. Blamed for killing domestic sheep lambs, although these are probably scavenged. Foraging is largely nocturno-crepuscular (light during the Arctic summer) and solitary, but congregates at large carcasses. Caches surplus food; 1 larder contained more than 500 eggs. Scavenges from bear and Grey Wolf kills, winter-killed Reindeer and human refuse. Social and Spatial Behaviour Usually solitary and monogamous, forming tight-knit breeding pairs that are territorial near the den. Pairs usually separate after raising pups, but remain in the territory year-round, pairing up again each spring to breed. Helpers from previous litters sometimes linger, forming extended family groups that persist if food is plentiful. Coastal home ranges are generally smallest (5–21km2), with high densities (4–8/100km2) due to more reliable food availability; inland ranges 15–60km2 and densities 0.09–3/100km2. Individuals may wander spectacular distances, possibly driven by rodent crashes, e.g. 2,300km over 3 years by an Alaskan male. Reproduction and Demography Seasonal. Mating February–May; births April–July. Gestation 52–54 days. Litter size typically 3–11, exceptionally reaching 19 in rodent booms. Pups weaned at 7–8 weeks, reaching independence at 12–14 weeks. Most disperse in autumn, but they may overwinter on their parents’ range; some (mainly females) become helpers. Both sexes mature at 10 months, but most individuals do not breed until their third year. MORTALITY Survival is tied to rodent abundance; up to 50% of adults and 80% of pups die in poor years, and populations collapse by up to 80%. Predators include Red Fox (especially of pups), large raptors, Wolverine, Grey Wolf and bears. Domestic dogs kill Arctic Foxes near human settlements and may also transmit disease. LIFESPAN Maximum 10–11 years in the wild, typically under 5; 15 in captivity. Status and Threats More than 100,000 Arctic Foxes are trapped annually for their dense fur, but populations appear to tolerate hunting if pressure is relaxed during poor food years. In Iceland, legally killed as pests by sheep farmers and eider-down collectors. Northwards expansion of Red Fox due to climate warming and human subsidies is causing Arctic Fox declines and range contraction in lowland Fenno-Scandinavia, possibly more widely. Protected in Finland, mainland Norway and Sweden, where historic population crashes have not recovered; unprotected elsewhere. Red List LC, population trend Stable.

| RED FOX Vulpes vulpes |

CROSS FOX, SILVER FOX, COMMON FOX

Includes NORTH AMERICAN RED FOX V. fulva

HB ♀ 45–68cm, ♂ 59–90cm; T 28–49cm; W ♀ 3.4–7.5kg, ♂ 4–14kg

The world’s most widespread and abundant wild carnivore. Typically various shades of rich red-brown, but highly variable, including platinum-tipped black (‘silver fox’), an intermediate morph called ‘cross’ and pale silvery blond. All morphs (except albinos) have black-backed ears, and white-tipped tails are typical but not ubiquitous. Sometimes classified as 2 species based on genetic analyses showing divergence ~209,000 years ago: Eurasian Red Fox (V. vulpes) and North American Red Fox (V. fulva). Distribution and Habitat North America, Eurasia and N Africa. Occurs in virtually all habitats to 4,500m, including farmland, suburbs and cities north of the Tropic of Cancer, except the northernmost Arctic and deserts of the SW USA. Introduced to Australia in the mid-1800s, where it has serious impacts on native wildlife. Feeding Ecology Highly opportunistic, eating mainly reptiles, birds and small mammals to the size of hares; also eggs, amphibians, fish, invertebrates, fruits, acorns, fir cones, sedges, fungi and tubers. Kills juvenile small stock and poultry, and consumes crops such as wheat and corn. Hunting is terrestrial (although it is recorded occasionally climbing to 8m) and mostly nocturno-crepuscular, often more diurnal in winter and where it is undisturbed. Usually forages alone, but aggregates in food-rich patches, e.g. shorebird nest colonies and dumps. Caches surplus food for later use, and has an excellent memory for larder sites. Readily scavenges: ungulate carcasses (including of domestic livestock) can be especially important in winter, and scavenges from human refuse, bird feeders and compost heaps. Social and Spatial Behaviour Usually solitary and monogamous. Mated pair is the main social unit, but sociality during breeding is very flexible. With sufficient food, may form groups comprising 1 male and up to 5 vixens (probably related). Group-breeding females may den alone or together; younger females are mostly non-breeding helpers from previous litters. Range size is resource-dependent, from 0.2km2 (Oxford, UK) to 50km2 (Oman). Density estimates 0.1/km2 (Arctic tundra), 1–3/km2 (temperate forest, Canada and W Europe) and exceptionally reaching 30/km2 with abundant food, e.g. urban areas where foxes are subsidised. Reproduction and Demography Seasonal. Mating is in winter, usually December–February, earlier in southerly latitudes (Australia: June–October). Births usually March–May. Oestrus 1–6 days; gestation 49–55 days. Litter size reaches 12 depending on food availability, typically 3–8. Pups weaned at 6–8 weeks, and most disperse from age 6 months before the next breeding season. Some young females remain as helpers. Sexually mature at 9–10 months. MORTALITY First-year mortality reaches 80% and averages 50% for adults, mainly due to humans. Large raptors, other carnivores and domestic dogs kill Red Foxes, although humans are overwhelmingly their main predator. Major vector for rabies, with outbreaks causing intermittent population crashes. LIFESPAN Maximum 9 years in the wild, typically <5; 15 in captivity. Status and Threats Remarkable adaptability and resilience enables it to tolerate intense persecution, with some 1–2 million wild individuals killed annually for the fur trade, and perhaps the same amount again by sport hunters and pest control. Unprotected in most of its range; exports of furs from India are restricted. CITES Appendix III – India; Red List LC, population trend Stable.

Plate 51

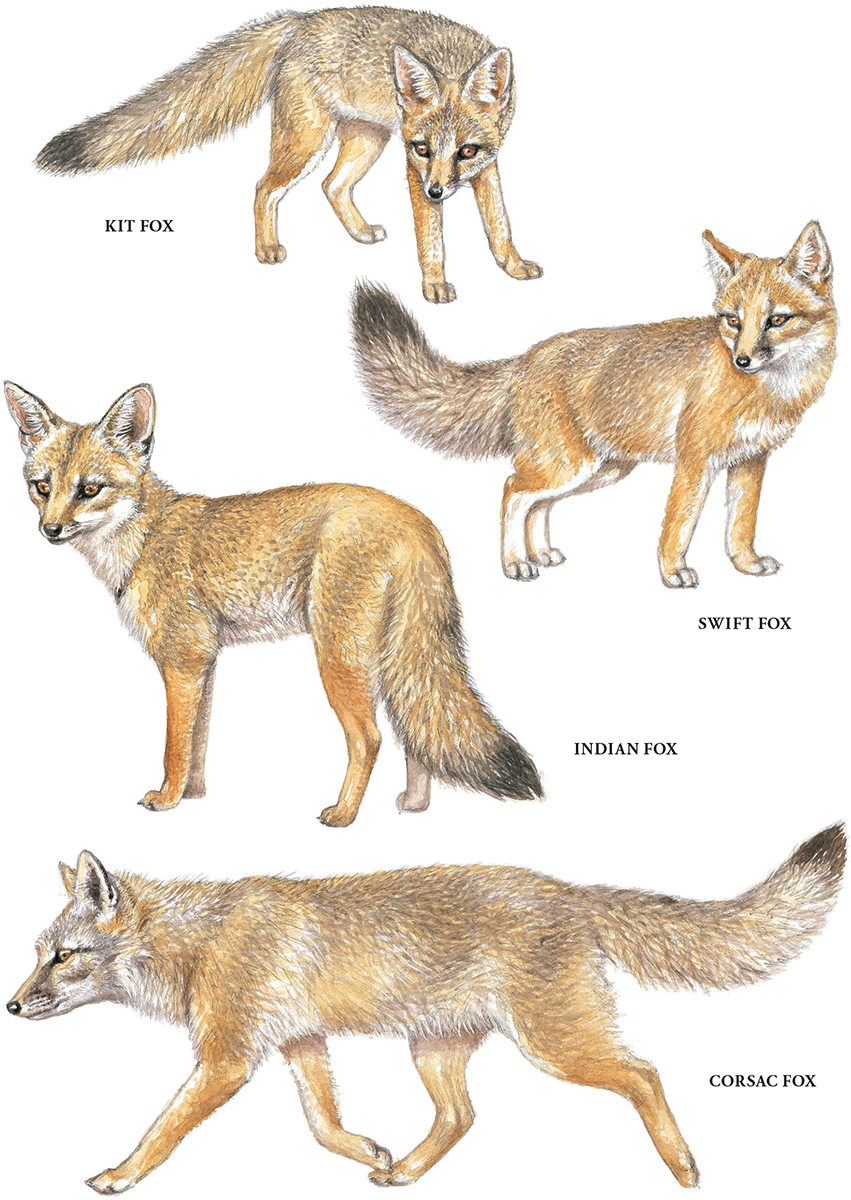

| KIT FOX Vulpes macrotis |

HB 45.5–54cm; T 25–34cm; W ♀ 1.6–2.2kg, ♂ 1.7–2.7kg

Smallest fox on mainland North America. Tawny grey with ochre sides, neck and legs. Closely related to Swift Fox; hybrids occasionally occur in a narrow band of overlap in Texas and New Mexico. Distribution and Habitat W USA and N Mexico. Inhabits semi-arid to arid desert scrub and grassland. Can occupy urban and agricultural areas. Feeding Ecology Eats mainly mice, rats, kangaroo rats, ground squirrels, prairie dogs, lagomorphs and insects; also small birds, reptiles, carrion, wild cactus fruits and crops, e.g. tomatoes and almonds. Foraging is mainly nocturnal and solitary. Scavenges from livestock carcasses and human refuse. Social and Spatial Behaviour Monogamous, normally mating for life. Helpers, usually grown daughters, often remain with the pair. Ranges are stable, with exclusive core denning areas. Range size (both sexes) averages 2.5–11.6km2. Densities fluctuate widely depending on prey oscillations: 10–170/100km2, averaging 44/100km2. Reproduction and Demography Seasonal. Mating December–January; births February–March. Gestation 49–55 days (estimated). Litter size 1–7. Weaning at around 3 months and independence at 5–6 months. MORTALITY Average annual mortality 65% (juveniles) and 45% (adults), mainly from Coyote predation and starvation during prey shortages. LIFESPAN 7 years in the wild, 20 in captivity. Status and Threats Secure but has undergone significant local declines, e.g. California and Mexico, from habitat conversion and eradication of prey colonies, e.g. prairie dog and kangaroo rat towns. Threatened in California and Oregon, endangered in Colorado, vulnerable in Mexico. Red List LC, population trend Decreasing.

| SWIFT FOX Vulpes velox |

HB 47.5–54cm; T 25–34cm; W ♀ 1.6–2.3kg, ♂ 2–2.95kg

Very similar to Kit Fox, with more rounded ears and a shorter tail. Distribution and Habitat Mid-western North America, from Alberta to New Mexico. Restricted to short- to medium-grass prairies and grassland. Tolerates dry land agricultural areas. Feeding Ecology Diet dominated by prairie dogs, ground squirrels, mice and lagomorphs, plus wild fruits, seeds, insects, small birds, reptiles, eggs and carrion. Foraging is solitary and mainly nocturno-crepuscular. Social and Spatial Behaviour Mated pairs are typical, but sociality is flexible; trios and extra-pair breeding occur. Pairs/groups maintain exclusive core areas with overlapping edges; neighbours are often related. Range size (both sexes) 7.6km2 (Colorado) to 25.1km2 (W Kansas). Reproduction and Demography Seasonal. Mating December (Oklahoma) to March (Canada); births March–May. Gestation 50–55 days. Litter size 3–6, exceptionally to 8. MORTALITY Rates average 67–95% (juveniles) and 36–57% (adults), mainly from Coyote predation. LIFESPAN 8 years in the wild, 14 in captivity. Status and Threats Extirpated from about 60% of its historic range, from massive prairie conversion and intense persecution of prey. Extirpated from Canada by 1938; now present as a small reintroduced population. Red List LC, population trend Stable.

| INDIAN FOX Vulpes bengalensis |

BENGAL FOX

HB ♀ 46–48cm, ♂ 39–57.5cm; T 24.5–32cm; W ♀ 2–2.9kg, ♂ 2.3–3.6kg

Slender, fine-featured fox with a narrow face, yellow-grey to silvery-grey fur and a black-tipped tail. Distribution and Habitat Endemic to the Indian subcontinent. Inhabits hot, semi-arid grassland, plains, scrub and open, dry forest. Occurs on agricultural land. Feeding Ecology Omnivorous, eating mainly small mammals and insects, supplemented by birds, reptiles, eggs, fruits, seeds and fresh shoots. Foraging is solitary and nocturno-crepuscular; often diurnal on cool or overcast days. Scavenges from carrion, but rarely since feral dogs dominate carcasses. Social and Spatial Behaviour Monogamous in mated pairs. Other adults sometimes associate with pairs, but do not help raise pups; their role and relatedness is uncertain. Range estimates average 1.6km2 (♀s) and 3.1km2 (♂s). Densities fluctuate due to rodent cycles and disease outbreaks, usually 1–15/100km2, reaching 150/100km2 in ideal conditions. Reproduction and Demography Seasonal. Mating November–January; births January–May. Gestation 50–53 days. Litter size 2–4. Both parents provision and guard pups. MORTALITY Disease is implicated in population crashes. LIFESPAN 8 years in captivity. Status and Threats Relatively widespread, but occurs at low densities in habitats that are under strong development pressure. Naturally vulnerable to population crashes, exacerbated by hunting pressure from people for food. CITES Appendix III – India; Red List LC, population trend Decreasing.

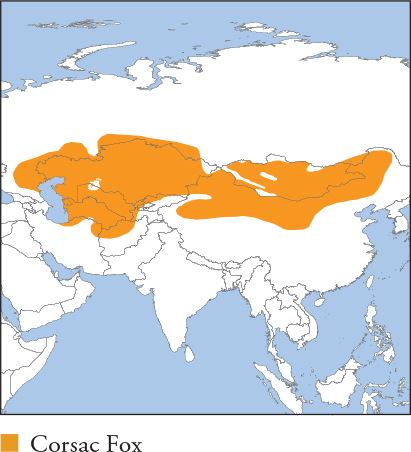

| CORSAC FOX Vulpes corsac |

CORSAC, STEPPE FOX

HB ♀ 45–50cm, ♂ 45–59.5cm; T 19–34cm; W ♀ 1.6–2.4kg, ♂ 1.7–3.2kg

Medium-sized fox with pale, tawny-grey fur (silky and frosted in winter) and a black-tipped tail. Distribution and Habitat C Asia, from W Russia to NE China. Inhabits steppes, grassland, shrubland, semi-desert and desert. Feeding Ecology Omnivorous and opportunistic, exploiting seasonal fluctuations in food, especially of rodents, e.g. lemmings, voles, ground squirrels, gerbils and jerboas. Also consumes birds, reptiles, insects and carrion. Foraging is solitary and usually nocturnal; diurnalism increases when feeding young pups and during food shortages. Scavenges, including from human refuse, Grey Wolf kills and winter-killed livestock. Social and Spatial Behaviour Forms monogamous breeding pairs, although it is unknown if they are permanent or territorial, and 2 females sometimes den together with their pups. Juveniles may become helpers. Range size (pairs) 3.5–11.4km2 (C Mongolia), occasionally to 35–40km2 in poor habitat. Reproduction and Demography Seasonal. Mating January–March; births mid-March–May. Litter size 2–10, averaging 5–6. Gestation 52–60 days. Both parents provision and guard pups; helpers sometimes assist. MORTALITY Average adult mortality 34% (protected reserve, C Mongolia), mainly from human hunting and Red Fox predation. LIFESPAN 9 years in captivity. Status and Threats Widespread and locally common, but heavy hunting pressure for furs and rodent-poisoning campaigns (especially in China) are pervasive. Extirpated in many areas, especially in Russia and its former republics. Red List LC, population trend Decreasing.

Plate 52

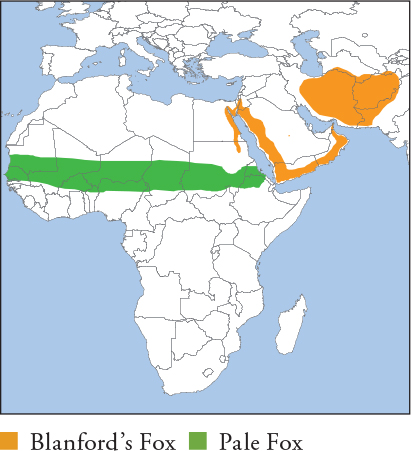

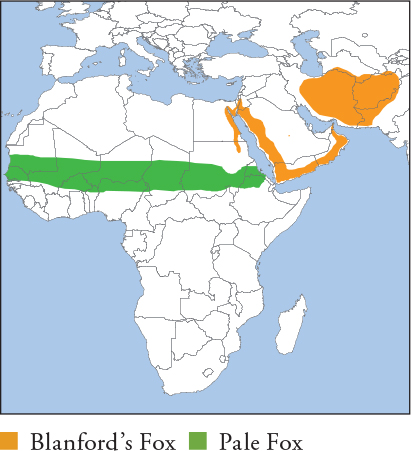

| BLANFORD’S FOX Vulpes cana |

KING FOX, ROYAL FOX, AFGHAN FOX

HB ♀ 34–45cm, ♂ 38.3–47cm; T 26–36cm; W 0.8–1.6kg

Very small fox with distinctive dark ‘tear’ lines along the muzzle. Brown-grey fur is interspersed with long black guard hairs, and very bushy tail usually has a black (rarely white) tip. Distribution and Habitat E Egypt, Arabian Peninsula and C Asia. Inhabits semiarid to arid rocky desert and mountainous habitats. Independent of water. Feeding Ecology Largely insectivorous and frugivorous, eating mainly beetles, crickets, grasshoppers, ants, termites, scorpions, wild capers, olives, grapes and melons. Small rodents, birds and (rarely) reptiles are also hunted; newborn ibex records are probably carrion. Foraging is usually solitary and nocturnal, with increased crepuscularity in winter. Social and Spatial Behaviour Forms territorial monogamous pairs that cooperate to raise pups, but are fairly solitary outside the breeding period. Non-breeding yearling females (possibly from previous litters) are often tolerated by resident pairs. Range size (both sexes) 0.5–2km2, averaging 1.6km2. Density estimates 0.5–2/km2 (Israel) to 8/km2 (high-quality habitat with abundant carrion, Jordan). Reproduction and Demography Seasonal. Mating January–February (Israel); births late February–May. Gestation 50–60 days. Litter size 1–3. Males groom, guard and accompany pups (2–4 months) on foraging excursions. MORTALITY Rabies and old age appear to be the main mortality factors. Red Fox is a confirmed predator. LIFESPAN <5 years in the wild, 6 in captivity. Status and Threats Fairly widespread and common. Locally threatened by habitat development, especially in coastal areas, and incidentally killed by poison set for other species. CITES Appendix II; Red List LC, population trend Stable.

| PALE FOX Vulpes pallida |

PALLID FOX, AFRICAN SAND FOX

HB 38–55cm; T 23–28.5cm; W 1.2–3.6kg

Very small fox, uniformly pale sandy cream except for dark-tipped tail (distinguishing it from Rüppell’s Fox). Ears medium-sized, in proportion to the head and lacking the oversized appearance in Rüppell’s Fox and Fennec. Distribution and Habitat Sub-Saharan Africa, in a narrow band from W Senegal–Mauritania to Eritrea and Ethiopia. Inhabits very arid, sandy and stony deserts, and dry savannah. Occurs near human settlements. Feeding Ecology Primarily insectivorous, eating mainly weevils, scarabs, grasshoppers and scorpions; small mammals, especially gerbils and jerboas, are also taken. Robust molars suggest fruits, seeds and plant matter are consumed, but these appeared very rarely in scats collected in SE Niger. Largely nocturnal. Social and Spatial Behaviour Mostly seen in pairs and small groups, probably mated pairs with offspring, suggesting patterns similar to those of other small foxes. Range estimates average 5.6km2 with minimal overlap, suggesting territoriality (Termit and Tin Toumma National Nature and Cultural Reserve, Niger) Reproduction and Demography Probably seasonal. Gestation (captivity) 51–53 days. Litter size 3–6. MORTALITY Poorly known; occasionally killed by domestic dogs. LIFESPAN Unknown. Status and Threats One of the least known canids; status unknown. Occasionally killed near settlements, and used locally for traditional medicines, e.g. Sudan, for asthma. Red List LC, population trend Unknown.

| RÜPPELL’S FOX Vulpes rueppellii |

SAND FOX

HB 35–56cm; T 25–39cm; W ♀ 1.1–1.8kg, ♂ 1.1–2.3kg

Small, fine-featured fox with large ears and a slender face. Body colour near white to greyish brown, often with a silvery sheen due to dark guard hairs. Long, bushy tail has a white tip. Distribution and Habitat N Africa (Sahara), the Arabian Peninsula and C Asia. Independent of water and inhabits semi-arid to very arid habitats, including sandy and stony deserts, rocky steppes, massifs, scrub and vegetated watercourses. Occurs near human habitation. Feeding Ecology Omnivorous. Eats small mammals, birds, lizards, insects and plant matter, including wild fruits (especially dates), desert succulents and grass (probably an emetic). Foraging is solitary and nocturno-crepuscular. Most hunting is terrestrial; climbs palm trees for dates. Scavenges from carrion and human refuse. Social and Spatial Behaviour Monogamous, forming mated territorial pairs, but larger aggregations of up to 15 suggest more complex sociality. Territories are largely exclusive, although large ranges overlap significantly. Female range sizes 13.2km2 (Saudi Arabia) to 53.8km2 (Oman); male ranges 20.9–84.4km2. Density estimates 0.7–1.05/km2 (fenced reserve, Saudi Arabia). Reproduction and Demography Seasonal. Mating November–February (Saudi Arabia); births March–May. Gestation 52–56 days. Litter size 2–6. Pups independent at 4 months and disperse at 6–10 months. MORTALITY Rabies, distemper and predation are the main factors; Steppe Eagle and Pharaoh Eagle-owl are confirmed predators. LIFESPAN 7 years in the wild, 12 in captivity. Status and Threats Widespread and quite common. Killed indiscriminately during poisoning campaigns, and absent in heavily grazed areas. Expanding Red Fox range (in association with human settlements) displaces Rüppell’s Fox; it is almost extinct in Israel as a result. Red List LC, population trend Stable.

| TIBETAN FOX Vulpes ferrilata |

TIBETAN SAND FOX, SAND FOX

HB 49–70cm; T 22–29cm; W ♀ 3–4.1kg, ♂ 3.2–5.7kg

Very distinctive stocky fox with a long, narrow muzzle, small ears and small, wide-set eyes on a broad face. Body grizzled grey with white underparts, and a rufous cape, head and lower legs. Distribution and Habitat Restricted to the Tibetan Plateau in Ladakh (India), N Nepal, and through S and C China; presence in N Bhutan is unconfirmed. Inhabits remote, cold, semi-arid to arid steppes, meadows, grassland and slopes at 2,500–5,200m. Tolerates ambient temperatures of –40°C to 30°C. Feeding Ecology Eats mainly small mammals, especially pikas (with which it is closely associated), mice and zokors. Also eats hares, marmots, birds, lizards, insects and berries. Eats carrion, including scavenging Grey Wolf kills, and follows foraging Brown Bears to mop up flushed rodents. Hunts alone and appears diurnal, possibly reflecting the activity patterns of pikas. Social and Spatial Behaviour Poorly known. Monogamous breeding pairs are typical, but adult trios with pups are recorded. Pairs are found in close proximity, especially in food patches like pika colonies, suggesting the species is not strongly territorial. Densities are naturally low, reaching 2–4/km2 with abundant prey and low hunting pressure. Reproduction and Demography Seasonal. Mating December–March; births February–May. Litter size 2–5. Gestation 50–55 days. MORTALITY and LIFESPAN Unknown. Status and Threats Widespread and inhabits remote areas, somewhat insulating it from human threats. Given its strong association with pika colonies, the gravest threat is the state-sanctioned rodent poisoning affecting most of the Tibetan Plateau. Red List LC, population trend Unknown.

Plate 53

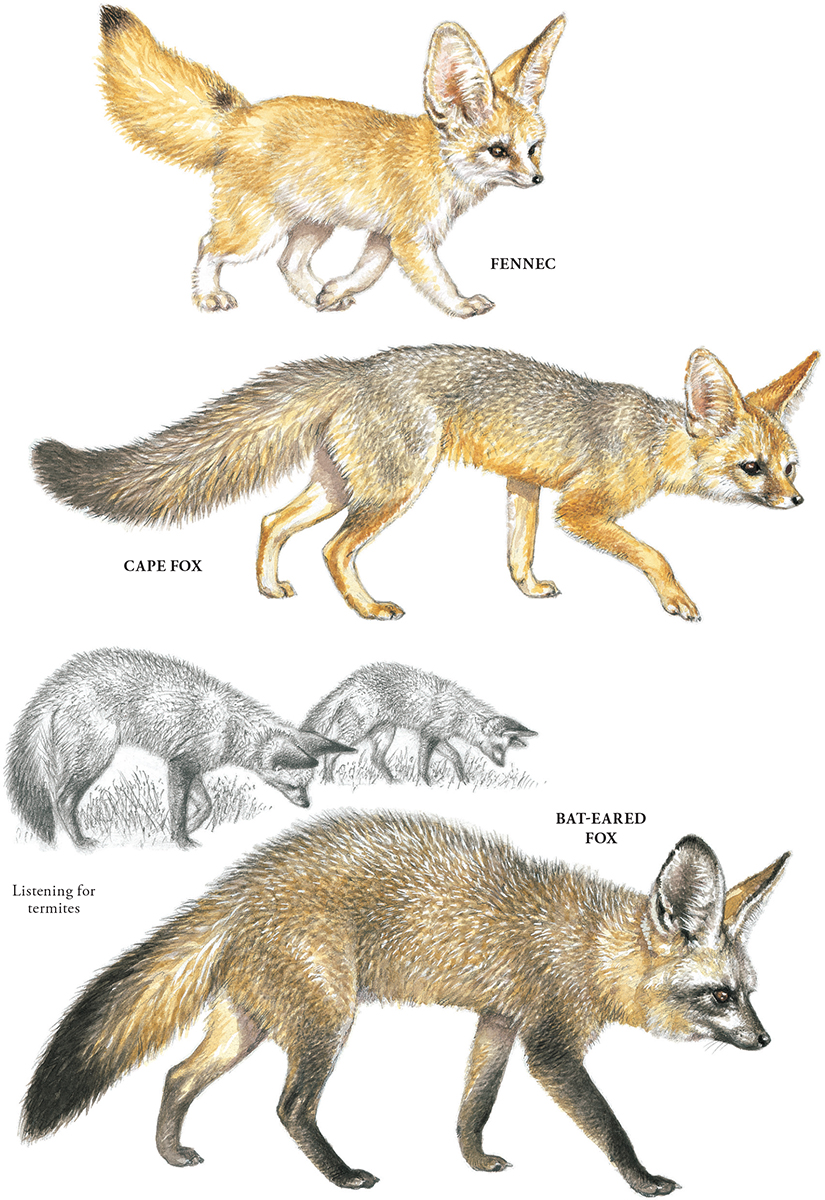

| FENNEC Vulpes zerda |

FENNEC FOX

HB 33.5–39.5cm; T 12.5–23cm; W 0.8–1.9kg