Look at the shirt or jeans you’ve got on: wherever there’s a seam — two pieces of fabric attached together — that’s sewing. If you look closely on the underside of the fabric, you probably can see the stitches holding the two pieces together.

Sewing comes first in this book because we think of it as a basic life skill, somewhere between breathing and, maybe, fixing a bike! Once you acquire some basic sewing know-how — like threading a needle, knotting your thread, and making a couple of simple stitches — you can do all kinds of useful things, such as mend your jeans, stitch a patch to your scout uniform, or add a button to your favorite bag so it will stay closed. To say nothing of the fun things you’ll be able to do! Like make your own clothing or Halloween costume, craft cute gifts for your friends and family, and, well, whatever you dream up.

We’re also starting with sewing because you’ll need basic sewing skills to finish or decorate many of the other projects in this book, even those that start with a different fiber craft, such as knitting or weaving. For example, you’ll need basic sewing know-how to tackle the embroidery projects in chapter 2 and to sew up the felt projects in chapter 3! Luckily, this chapter will teach you what you need to know.

Fabric. We mostly call for fabrics that don’t fray or unravel around the edges, such as cotton jersey (also known as T-shirt fabric), felt, or polar fleece, because they’re easy to work with and you don’t need to hem them! Woven fabrics, like the kind button-down shirts are made of, are harder for beginners to work with, because they don’t stretch at all, and they tend to fray at the edges. If you have a couple of big old T-shirts and a wool sweater you can shrink in the wash (see Felt the Fabric), you’ll have all the fabric you need for the projects in this chapter. If you’re using new fabric, it’s a good idea to wash and dry it before starting your project, so it won’t shrink later and surprise you.

Needles. You’ll need a sharp needle with an eye large enough for the thread: an embroidery or chenille needle is a good bet; don’t use a tapestry needle, which has a rounded, rather than sharp, point. (Trying to sew with a dull needle is very frustrating.) A stray piece of felt is a good place to keep your needles, or (once you learn to sew) you can stitch a couple of rectangles of felt down the middle to make a “book” for storing them.

Thread. We like embroidery floss (also called embroidery thread) because it comes in a million colors, and because you can separate its six strands by carefully pulling them apart if you want to sew with something thinner. (See How to Separate Your Floss for tips on separating the strands.) Alternatively, we like Dual Duty Plus Button & Carpet thread, a very sturdy thread made by the company Coats & Clark.

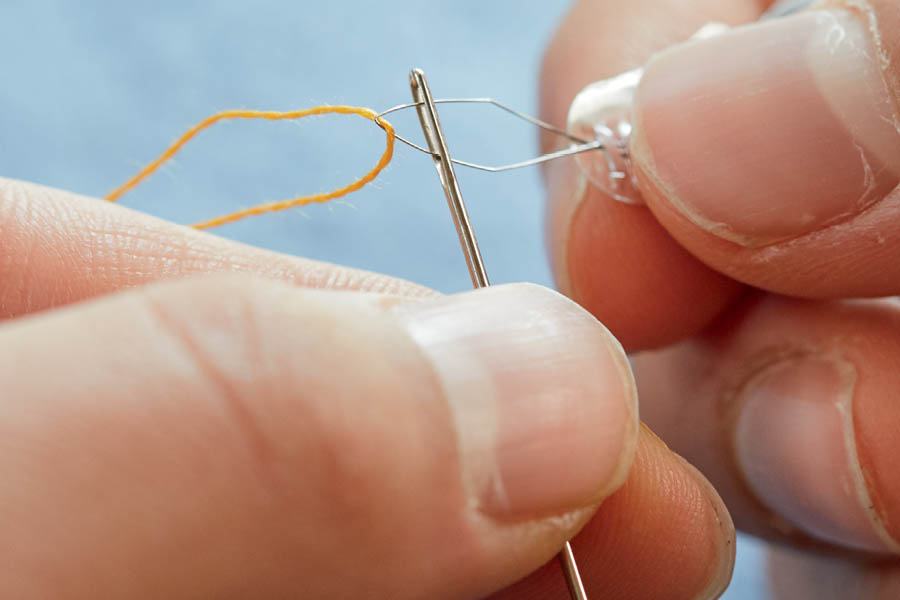

A needle threader. This optional item (shown above) is handy if threading needles is not your thing.

Scissors. Sharp ones are ideal; you’ll need them for cutting both thread and fabric. (Cut paper with a different pair, since paper will dull them.)

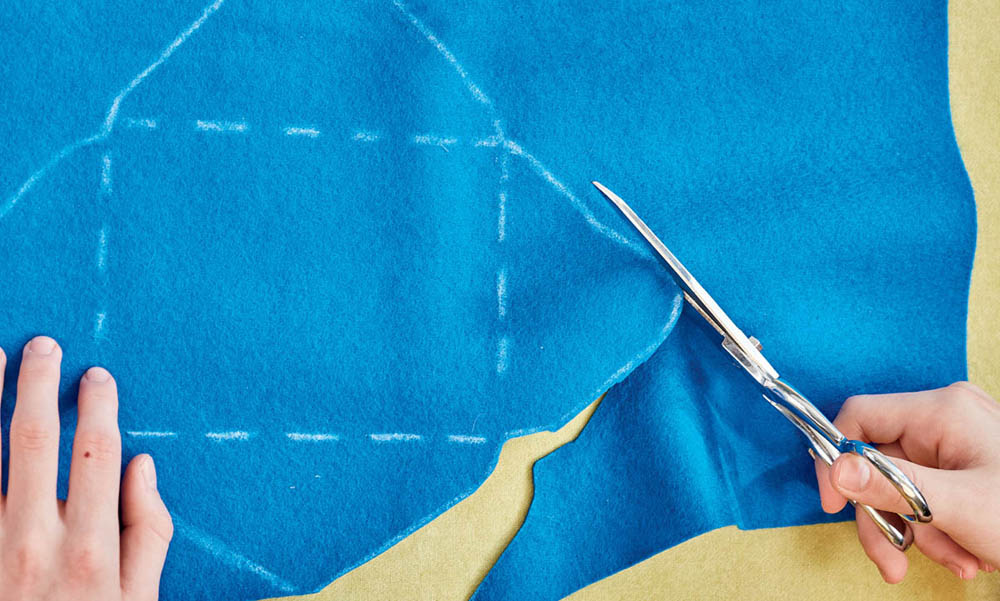

White chalk or a disappearing-ink fabric marker. This will let you mark your fabric with the lines you want to cut or sew, while leaving you the option to change your mind or make a mistake. Regular chalk can be sharpened with a large-mouthed handheld pencil sharpener so you can make finer lines, which you can simply brush off when you’re done sewing.

A ruler or measuring tape.

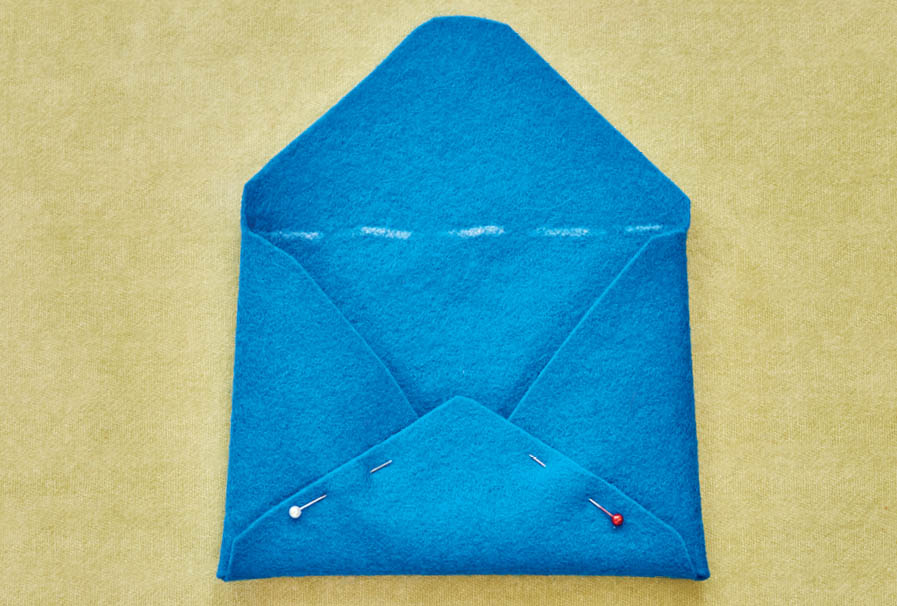

Pins. Straight pins are useful for connecting a pattern to your fabric before cutting or for joining two pieces of fabric together before sewing. Keep your pins in a pincushion for easy access.

In the Stone Age people in Europe and Asia sewed clothes from animal fur and skin, using needles made from antlers and bone, and thread made from other animal parts, such as sinew, which connects an animal’s bones and muscles and probably made pretty strong thread. The sewing machine wasn’t invented until the nineteenth century, which means that people were sewing by hand, and by hand only, for many thousands of years.

This bone sewing needle dates back to the second or third century.

If you have a needle threader, great. But even if you don’t, threading a needle is not difficult. For both methods, start by cutting an arm’s length of thread; longer and it’s likely to get tangled, shorter and you’re going to run out quickly and be frustrated.

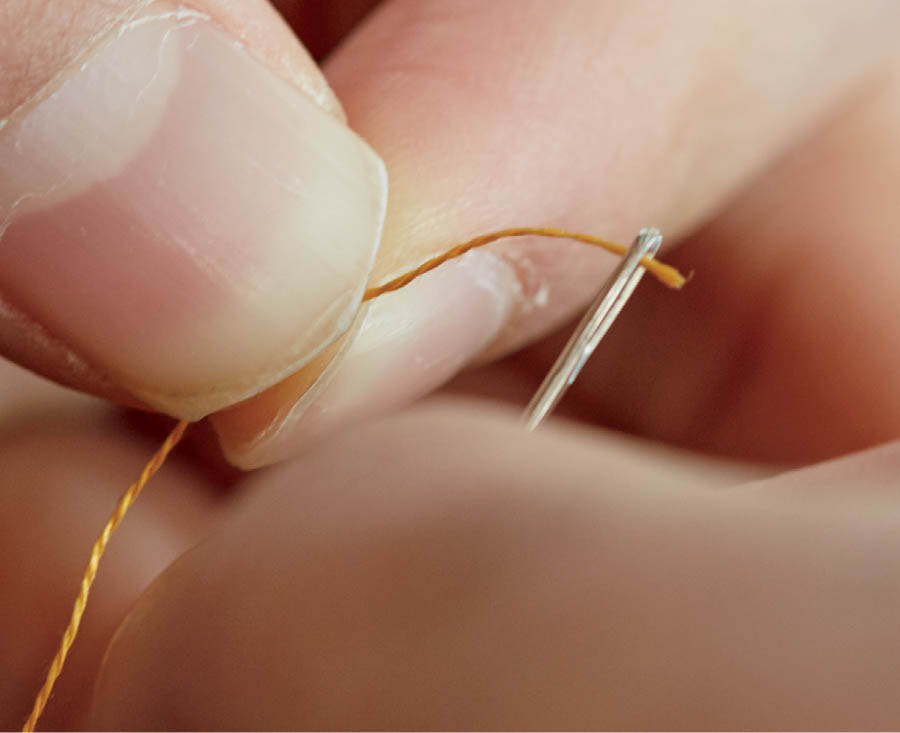

For hand threading, our preferred method is the old-fashioned “lick and thread.” Gross as it might sound, when you lick the end of your thread, you get all the individual strands to stick together into a point, and it’s easier to poke this into the eye of the needle. Lick one end of the thread, then push that end into the eye of the needle. Pull it through so that you have a 6-inch tail.

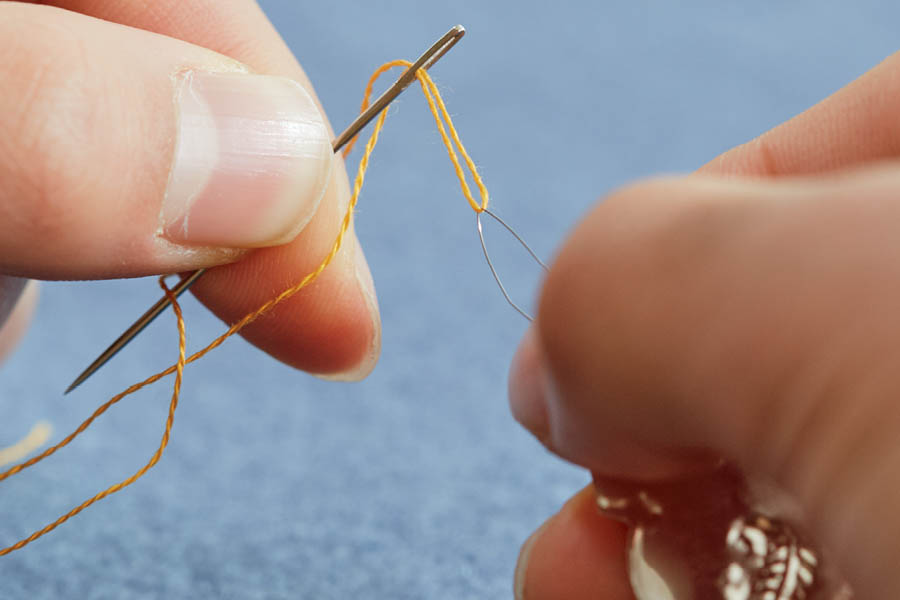

Regardless of which method you use . . . voilà! Your needle is now threaded. When you’re pulling a stitch through your fabric as you sew, try pinching the eye of the needle to keep the thread from pulling out of it.

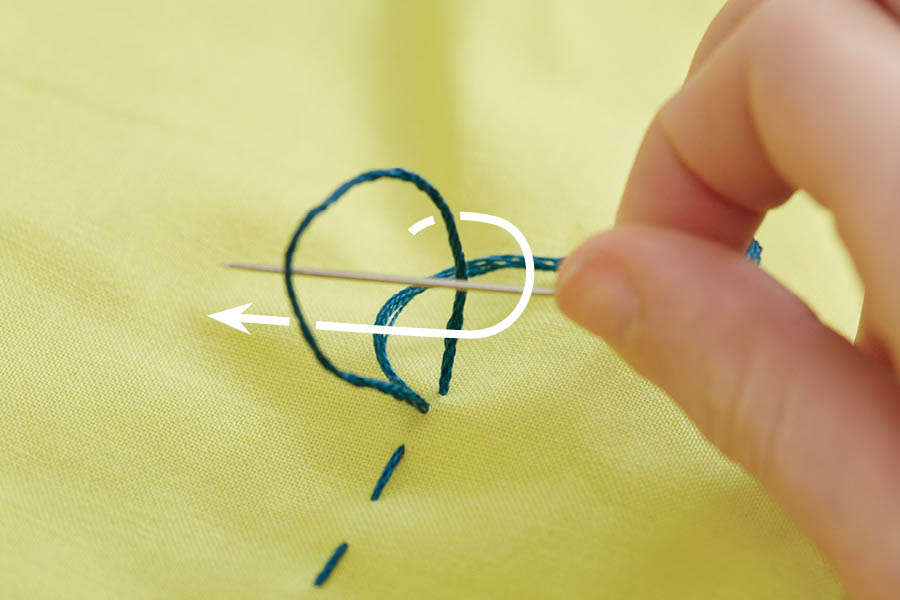

This knot will keep the thread from pulling through your fabric when you start. The process works best when you begin by licking the end of your thread.

(To sew with a double length of thread, pull the short thread tail until it is even with the long tail. Then wind both ends around your pointer finger.)

When you get to the end of your sewing, you’ll need to tie a knot on the underside of your project. Make sure to leave at least 6 inches of thread, or this will be very frustrating!

Make a sewing kit that doubles as a pincushion!

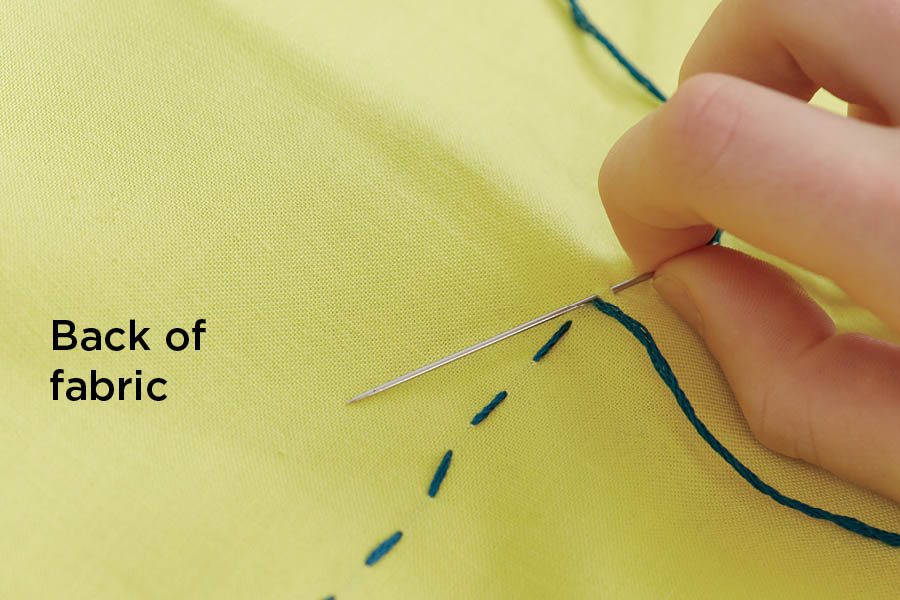

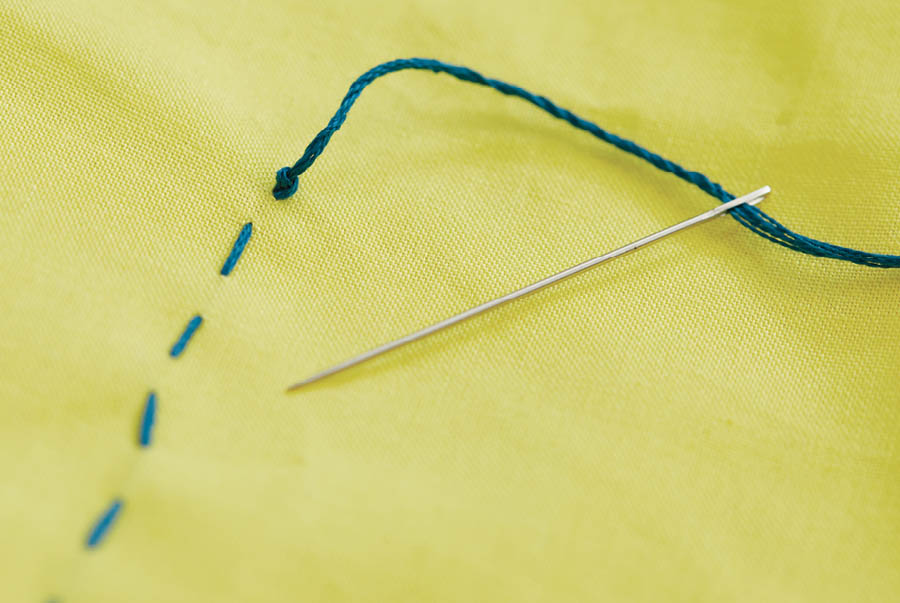

The backstitch produces very sturdy seams that don’t pull apart, making it a great stitch for securely closing up something like a beanbag (see Beanbag That Is Also a Hand Warmer). It also produces lines of stitches so close together they look solid — perfect for tracing a drawing or writing. It’s called a backstitch because with every stitch, your needle loops back to your previous stitch before making the next stitch forward. Try practicing on a scrap of fabric before stitching your project.

. . . and bring the needle back up through the fabric one stitch length ahead of your first stitch.

One of the reasons we love working with embroidery floss is because it’s so versatile. If you’re filling in shapes or creating chunky designs, you may want to sew with all six strands of your floss, while other times — like if you’re working a delicate design or a line of writing — you may want to work with only three or four strands of it. To make sure your stitches are secure, though, we don’t recommend sewing with fewer than two strands. (See Separate Your Floss for how to separate strands.)

Toss them into a bucket and keep score — and they’re toys! Heat them in the microwave and pop them in your pockets — and they’re hand warmers! Either way, this is a fun project that comes together quickly, and it makes a great gift. Make your beanbag as big or small as you like, or vary the sizes for different projects.

Embellish your beanbag with embroidery, if you want (see chapter 2). Just make sure to decorate your pieces of fabric before you sew them together and fill them up!

Instead of using your beanbag as a toy or hand warmer, you can add a tablespoon (about 12 grams) of dried lavender to your filling, call it a sachet, and use it to scent your dresser drawers.

If you’re planning to offer your beanbags up (or use them yourself) as hand warmers, use wool felt for the outside. Synthetics can behave strangely in the microwave, which is where you’ll heat them up.

Rice is our favorite choice for filling hand warmers (it smells good when you heat it!), but whatever you choose, don’t use popcorn! Guess what popcorn will do in the microwave. Go on. Guess.

Here's your finished beanbag!

A really expert sewer helped us with this project, which is why it looks so perfect! Don’t worry — our stitches never look as neat as this. And yours don’t have to, either.

Blanket stitch around your completed beanbag to add a neat decorative element. Or, if you prefer, sew the whole thing up with a blanket stitch or whipstitch instead of a backstitch — just keep your stitches nice and close together so the filling doesn’t fall out!

backstitch + blanket stitch (left); whipstitch (right)

To use your beanbag as a hand warmer, heat it in the microwave for one minute; if it’s still not hot, try one more minute. Be very careful when you remove it, just in case it gets hotter than you thought it was going to!

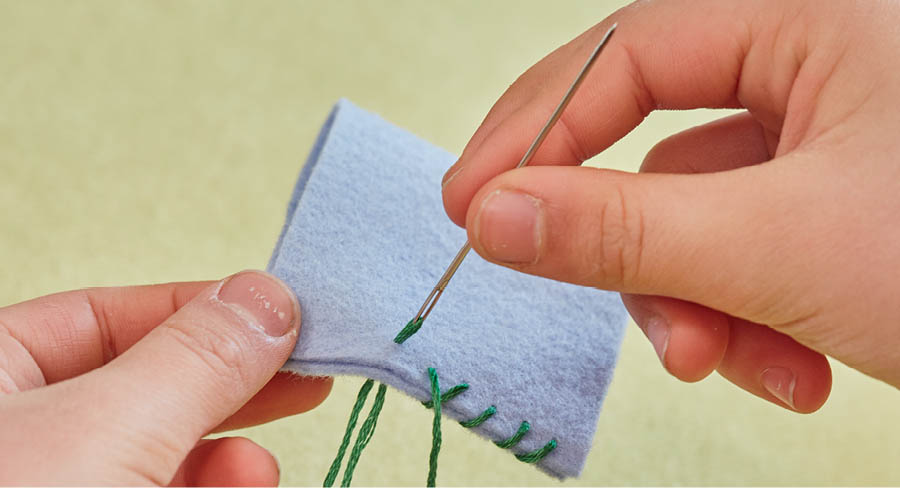

A whipstitch is a quick way to sew together two pieces of fabric along the edge. It doesn’t look as tidy as the blanket stitch, but it’s easier. (Catherine uses it for everything!) Try practicing on a scrap of fabric before stitching your project.

Let the purpose of your sewing determine how far apart you make your whipstitches. If you’re closing up something that has a filling or stuffing, you’ll want your stitches to be quite close together so it doesn’t spill out. But if you’re using whipstitches to sew a fun patch onto your jeans, the distance between your stitches can be greater since they’re more decorative than functional.

To play this fun game, you’ll need three beanbags and three empty containers of varying sizes: a bucket, a flowerpot, and a soup can, for example. You can play by yourself, but it’s more fun with other people.

Set Up. Use a stick (or tape) to mark a line on the ground (or floor). Then arrange the containers in a row starting about 10 feet away, smallest to biggest (about 6 inches apart), with the smallest closest to you, and the biggest farthest away.

Play. Take turns tossing all three of the beanbags and keeping score.

You can use a felt envelope for so many things: to store your jewelry, glasses, or Swiss Army knife; to wrap a small present or gift card; or as, yes, an envelope for giving (or keeping) an important letter. Feel free to use your own homemade felt (see Felt the Fabric), just expect it to be a little less smooth and even than store-bought felt.

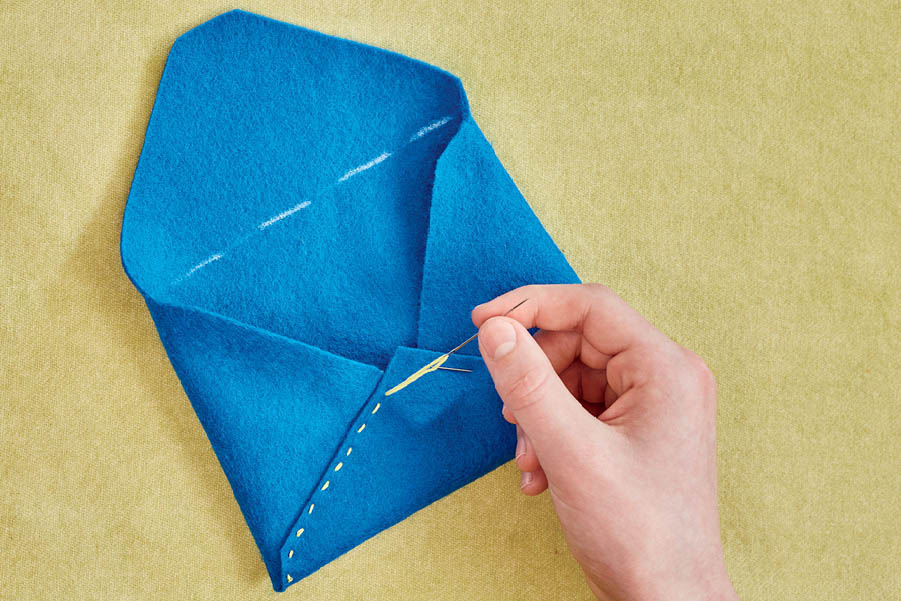

Starting in that corner and taking care to not stitch all the way through the front of the envelope fabric, use a running stitch to sew the bottom flap up from one corner and down to the other corner.

As you sew, pay attention to how much working thread you have. Don’t leave yourself less than 6 inches of thread to work with, or you’ll be frustrated trying to knot it. But if you find yourself running out of thread before you’re done with your project, don’t worry. Simply tie off and trim your original thread on the underside of the fabric (see Tie Off the Thread), thread your needle anew, and start sewing again, pushing the needle up through the fabric near your last stitch.

Trying to use a really long piece of thread to avoid knotting off in the middle is a trick we’ve used — but it can backfire, since long thread tends to tangle and be really frustrating!

If you want your envelope to close securely, you can add a button.

Fold the top flap down. Then with chalk, mark through the buttonhole onto the fabric underneath. That’s the spot where the button will go.