Chapter 1

Understanding Health and Fitness Tracking

IN THIS CHAPTER

Getting a grip on self-tracking

Getting a grip on self-tracking

Exploring all the reasons why tracking your health is a good idea

Exploring all the reasons why tracking your health is a good idea

Understanding a few health tracking pitfalls

Understanding a few health tracking pitfalls

Checking out self-tracking stats such as steps, distance, and heart rate

Checking out self-tracking stats such as steps, distance, and heart rate

You are a data-generating machine. When you pay with a credit card, drive through an automated toll system, answer an email, or make a call, you leave a steady stream of ones and zeroes in your wake. This so-called digital exhaust is the trackable or storable actions, choices, and preferences that you generate as you go about your life. Even when you’re just browsing the web, you leave behind not fingerprints but clickprints that uniquely identify your surfing behavior and lengthen the paperless trail that documents your electronic self.

All the data you generate is invariably used to make others rich, usually by selling it to advertisers and marketers. Wouldn’t it be nice if you could generate data that would help you? I’m not talking about data that will make you rich, at least not literally. I’m talking about data that you can use to make yourself healthier, fitter, slimmer, and calmer.

Welcome to the world of health and fitness tracking. In this chapter, I take you on a tour of this world, explore its benefits (and, yes, its few downsides), and introduce you to the types of data you can track. It’s all presented from a Fitbit point of view.

Introducing Self-Tracking

From time to time, you might harbor vague worries about oversharing on social networks or being tracked online by ad networks, but you probably don't think about the data shadow you cast wherever you go. However, a growing segment of the population spends a remarkable amount of time and effort trying to generate more personal data. While the rest of us are content to step out for a short walk after lunch, these people count every step they take. The likes of you and I might groggily estimate the number of hours we slept last night, but these people wear their Fitbits to bed to know exactly how many hours and minutes they slept and what portion of that sleep was spent in the REM (rapid eye movement) state.

I speak of self-trackers, people who use technology to acquire, store, and analyze their own life data. Their self-tracking can create detailed records of food, exercise, and location, as well as mood, alertness, overall well-being, and other seemingly non-quantifiable psychological states. This process of self-digitization is almost always enhanced by a Fitbit or similar wearable computing technology that enables the self-monitoring of physiological states and self-sensing of such external data as steps taken and floors climbed. These self-professed data junkies select from a variety of apps and websites that serve as tools for self-quantifying — and that prod them into doing even more of it. It’s no wonder, then, that the movement as a whole is often called the quantified self and its practitioners are increasingly known as quantified-selfers or, simply, QSers.

You might think that the point of all this self-scrutiny is just to keep a record of vital stats, but self-trackers are not content with merely tracking a few numbers. Their interest lies in quantitative assessment: extracting knowledge from the raw data. They want to put their lives under the macroscope, which is the general term for any technology that enhances a person's ability to gather and analyze data. If that data tells you that you're just as bright-eyed and bushy-tailed on days when you managed only five or six hours of sleep, the lesson is clear: You’re one of those lucky people who don’t need seven or eight hours of sack time. If your heart rate spikes when you sit down to dinner, maybe a little family counseling is in order. In short, by analyzing detailed data over a long time, self-trackers turn themselves into self-experimenters, or perhaps even body hackers. The aim? Nothing more or less than the examined life, albeit one where examined means tracked, quantified, recorded, and analyzed.

Why Track Your Health and Fitness?

Self-tracking is a bona fide trend, but is it a bandwagon you should jump on? Perhaps you’ve come to the conclusion that you could be more active, fitter, calmer, and just healthier overall. If so, that’s great! But you might also be asking yourself whether you really need to self-track your activities, exercises, food, and sleep. Why go to the trouble? Can’t you just do what’s necessary and leave it at that?

So many questions! Fortunately, the answers to all of them lead to the simple conclusion that, yes, self-tracking is worth the effort. Why? I’ve come up with no less than ten reasons:

- Monitoring your progress

- Figuring out what does and doesn’t work for you

- Keeping yourself motivated

- Challenging yourself

- Challenging others

- Figuring out what health or fitness activities to try next

- Performing experiments

- Breaking bad habits

- Encouraging good habits

- Learning about yourself

In the next few sections, I fill in the details for each reason.

Putting numbers to feelings: Monitoring your progress

Perhaps the most straightforward reason to track your health and fitness is to measure your progress. Sure, when you first start a new health or fitness regimen, at some point you start to feel better, and in many cases a lot better. But that initial massive — and, hence, noticeable — difference soon gives way to smaller — and, hence, not always noticeable — improvements. Before long, it might seem as though you’re no longer progressing at all, which is the point at which many people either scale back their lifestyle changes or quit altogether.

The problem here is that determining whether you feel better isn’t an exact process, especially when those feelings become subtle. Don’t get me wrong: Feeling fitter or healthier is a fantastic reward for all that work you’re doing. But for long-term success, you need to back up those subjective feelings with some objective data. To get that objectivity, you need to measure your progress by monitoring your activities, exercises, and body composition. That’s where your Fitbit comes in, because it gives you a record of what you’ve done, which you can compare to what you’re doing now.

How does that comparison help? Well, if you don’t feel all that much better now than you did last month, but your Fitbit tells you that, say, you’re averaging two thousand more steps per day or your heart rate is five beats lower, you know you’re still heading in the right direction despite how you feel. Oh, and good job, by the way!

Figuring out what does and doesn’t work for you

The road to your best self isn’t a straight line. Yes, the general direction is clear —move more, eat better, and reduce stress — but the specific route to get there is different for everyone. Ideally, you’ll just happen to take the path that’s right for you and not head down a bunch of dead-end streets. Ah, but there’s the rub: How do you know when you’re cruising down the right road and when you’re wasting your time on a cul-de-sac? In short (and to finally move on from that now overdone “road” metaphor), how do you know what works for you and what doesn’t?

That’s where health and fitness tracking shines. After you’ve used your Fitbit for a while, you end up with a priceless trove of data that you can mine for insights into what has been effective for you in the past. For example, if your main goal is to lose weight, you can analyze your historical data to look for periods when your weight dropped steadily and when your weight stayed the same or even increased. Now you can compare what you were eating, what types of exercise you were doing, how much sleep you were getting, and so on for those different periods. Ideally, you’ll start to see patterns in the data that tell you what works and what doesn’t.

Keeping yourself motivated

You might think that you don’t need to track your health and fitness because all you need to do is set a goal and then work towards it day in and day out, without exception. Well, sure, that would be great if you could manage it, but study after study has shown a hard truth: Willpower doesn’t work. By sheer force of will, you can’t make yourself do the work necessary to get fit or lose weight or reach whatever you’ve established as your health or fitness grail.

Does that mean there’s no point in even trying? Definitely not! The secret sauce of success here isn’t willpower — it’s motivation. If you’re sufficiently motivated to reach your goal, willpower is unnecessary because you’ll want to do the work you need to do to get where you want to go.

Motivation comes in many forms: an upcoming beach vacation, a future charity run, or a bet with a friend. You can also use your Fitbit to get motivated: If you look back at your historical data and see your daily steps steadily increasing or your weight steadily decreasing, the motivation to keep that trend going is right there.

Not only that, but you can configure your Fitbit with specific daily goals, such as 10,000 steps and 10 floors climbed (see Figure 1-1). Your Fitbit will show your progress towards those goals, motivating you to walk the long way home or take the stairs instead of the elevator to put yourself over the top.

FIGURE 1-1: Set daily goals for steps, calories burned, floors, and more.

Challenging yourself

One of the main reasons why people fail to reach their health or fitness goals is that they start off well and see some good results, so they just continue what they’re doing. That doesn’t sound so bad, except that your body has a wonderful way of adapting to most things you throw at it. When you start walking or running or lifting weights, what feels excruciatingly hard at first starts to feel pretty good after you’ve done it a few times. The exercise is stressing your heart and slightly breaking down your muscles. Once you stop, your body doesn’t just repair the damage; it rebuilds your heart and muscles so that they’re stronger. That process, which is called adaptation, is one of the secrets of getting fit.

Or, I should say, it’s one of the secrets of getting fit if you slowly and steadily increase the amount of stress you place on your body. If you just keep doing the same old thing, your body will simply adapt to that load and stop improving, which is why all successful health and fitness programs require you to challenge yourself. If you averaged 10 minutes per mile on your runs last week, see if you can run at 9 minutes and 45 seconds per mile this week; if you averaged 10,000 steps a day last month, shoot for 11,000 this month; if you walked 900 miles last year, set your sights on an even 1,000 this year.

How do you know what you did last week, last month, or even last year? Your Fitbit can keep track for you, so it’s easy to look back on your historical data and challenge yourself to be a better version of yourself.

Challenging others

Ideally, with the help of your Fitbit, your health and fitness motivation will come from within, but internal motivation isn’t all you should look for. External motivation — that is, getting other people involved in firing yourself up to exercise or diet or whatever — can be an important part of your new regimen. For example, the simple act of announcing your health or fitness goal to friends or family members can do wonders for motivating you to stick to that goal.

How can your Fitbit help here? As I show in Chapter 4, your Fitbit account comes with a ton of social features. For example, after you’ve connected with some people, the Fitbit app displays a leaderboard that shows who among your friends has done the most steps in the past week, as shown in Figure 1-2. Similarly, Fitbit offers several challenges that you can invite people to participate in. One popular challenge is to see who can take the most steps over the coming weekend.

FIGURE 1-2: See who among your friends has taken the most steps.

Figuring out what comes next

Health and fitness regimens are not — or shouldn’t be — static routines. But even if your program includes steady increases and regular challenges (both internal and external), you’ll still be faced one day with the “What do I do next?” question. I’m not talking about how many steps you should walk that day or what you should eat. No, this is Big Picture stuff: Adding entirely new types of exercise, cutting out parts of your routine, and so on.

These major changes shouldn’t be undertaken willy-nilly. Fortunately, if you’ve accumulated a decent amount of historical health and fitness data, you can make an informed choice without the willy or the nilly.

For example, if you’ve been running and cycling, you can examine your previous workouts to see which sport has shown the most improvement. If you feel you’ve worked equally hard in both but, say, your running performance has improved much faster than your cycling, you might decide to focus more on your running.

Performing experiments

Despite what many so-called gurus will try to sell you, gaining and maintaining health and fitness is not complicated:

- To lose weight, your calories out must exceed your calories in.

- To eat well, your diet should consist of lots of fresh fruits and vegetables, not too much meat (especially red meat), and little processed food.

-

To get fit, find an activity or sport you like, start easy, and then slowly but steadily increase the duration and intensity.

If you’ve been sedentary for a long time or have health problems such as heart disease or diabetes, I strongly advise you to see your doctor before beginning any type of exercise program.

If you’ve been sedentary for a long time or have health problems such as heart disease or diabetes, I strongly advise you to see your doctor before beginning any type of exercise program. - To sleep well, avoid screen time before bed, go to bed at a regular time, and get at least seven or eight hours of shut-eye.

If you follow these basic guidelines diligently, health and fitness will follow as day follows night. That said, nothing is stopping you from thinking outside this basic health and fitness box. If you run or cycle, for example, you could try adding some workouts on an elliptical machine or a stair-climber to improve leg strength. Or you could add yoga or Pilates sessions to strengthen your core (the muscles around your trunk and pelvis).

However, you need to set up these trials like an experiment. Your Fitbit data will tell you where you are now, and you can then monitor your stats as you add an exercise or activity to see what effect it has.

Breaking bad habits

You form habits by repeatedly making the same choices over time, to the point where you no longer even think about what you’re doing. Sit at your desk doing work all day; sit on your couch watching TV all evening; repeat tomorrow and the next day and the day after that. Just like that, you’ve developed the bad habit of sitting most of the day, and you probably don’t even realize it.

Ah, but that’s where your Fitbit comes in to save the day. Above all else, a Fitbit is an activity tracker, tracking when you move during the day and when you don’t. For example, your Fitbit can track the total number of minutes you’re active during the day and the hours during the day when you take at least 250 steps. If your total active minutes is very low and you don’t take at least 250 steps most of the hours during the day, you have a bad inactivity habit. But now, thanks to your Fitbit, you know you have a bad habit, which is the first step in breaking the habit and getting more active.

Encouraging good habits

Making bad choices over and over, day after day, leads to bad habits, but here’s the good news: Making good choices over and over, day after day, leads to good habits. Health and fitness tracking can help you get on the good habit path by showing you which activities bring positive results. And seeing those positive results in hard numbers — increased steps, lower heart rate, or a weight closer to your goal — gives you the motivation to keep doing those activities. The result is a virtuous cycle that leads to the formation of good health-and-fitness-enhancing habits.

A top-notch tracker will also help you form good habits by giving you small nudges throughout the day. For example, when Fitbit shows you any daily stat, it includes an icon with a partial circle around it, and that circle is completed only when you reach your daily goal. For example, Figure 1-3 shows that today I’ve taken a bit less than 9,000 steps, and the not-quite-filled-in circle tells me that I’m shy of my goal of 10,000 steps. I want to complete that circle, so I’m motivated to keep moving.

FIGURE 1-3: The circle associated with each Fitbit stat closes when you’ve reached your goal.

Similarly, most Fitbits will display a notification at ten minutes to the hour if you’ve yet to meet your hourly goal, which by default is 250 steps, as shown in Figure 1-4. That’s just two or three minutes of walking, so why not get out of your seat and move?

FIGURE 1-4: Your Fitbit nudges you if you haven’t taken at least 250 steps this hour.

Learning about yourself

A typical health and fitness tracker generates a ton of data. Depending on the device’s capabilities, it can track steps, heart rate, floors climbed, distance, pace, active minutes, and calories burned. That wide range of stats has one thing in common: Each piece of data tells you something about yourself. Without a tracker, the days turn into weeks, the weeks turn into months, and the months turn into years, and all the while you almost certainly have only a vague idea of how active you are, how much sleep you’re getting, and how well you’re eating. And, if you’re like most people, even that vague idea is probably an overestimate. Improving your health and fitness means knowing yourself, and the best way to do that is to get some objective data about your activities, workouts, and body composition. That’s right in the wheelhouse of any tracker worthy of the name, so if an examined life is your goal, make a health and fitness tracker your tool.

Understanding the Downside of Health and Fitness Tracking

Downside? With all the positive reasons for tracking your health and fitness outlined in the preceding section, could being a self-tracker have any downsides? Yep. Several pitfalls exist, but they are minor and can be easily avoided if you understand them and are mindful of them as you track your activity. Here they are:

- Feelings of pressure or stress to meet your daily goals: Meeting your daily goal for, say, steps taken or active minutes is a great feeling. However, in your quest to get that feeling, you might end up putting a ton of pressure on yourself. First, remember that although meeting your goals is worthwhile, a relaxed attitude towards those goals is best. Plus, stress can undo many of your health and fitness gains, so there’s some twisted irony to self-generating stress about those health and fitness gains.

- Feelings of guilt, shame, or unworthiness when you don’t meet your daily goals: Your daily activity goals are meant to be a gentle goad that gets you moving and making better choices in your life. These goals are not judgements, however. If you fall short of floors climbed or calories burned, shake it off and resolve to do better tomorrow. Remember that the road to good health and overall fitness is a long one (in fact, it is — or it should be — a life-long one) and doesn’t depend on the results of a single day. If you meet your goals most of the time (think of them as “daily-ish” goals), you’ll eventually get where you want to go.

- Having your daily routines disrupted or controlled by your desire to meet your activity goals: If by “daily routines” you’re talking about prolonged sitting at work or in the evening, being active instead is an upside. However, if an old friend invites you out for a coffee or a meal and you beg off because you need to get in a few thousand more steps to meet your goal, that decision is probably not balanced. Go ahead and meet your friend; you can always reach your goal tomorrow. Better yet, ask your friend to go on a walk with you!

- Feeling that an un-tracked activity is a wasted activity: You go out for a long walk, realize you’ve forgotten your Fitbit, and no longer enjoy the walk because now the steps and activity time don’t “count.” Okay, I get it: In an ideal world, you’d never miss a step or a minute or a mile. But in the real world, many activities are untracked. That’s fine because it’s way more important that you are active, even if that activity is now “tracked” only in your head.

- Lacking motivation to be active if you don’t have your tracker: This pitfall is related to the preceding one in that an activity undertaken without a tracker isn’t real or important because the activity won’t generate stats. Without those numbers, you lack the motivation to even do the activity. Remember that your health, not a bunch of stats, is what is real and important. Do the activity anyway because it will get you closer to your long-term goal. Your future healthy and fit self will thank you.

Learning about Health and Fitness Tracking Metrics

A metric is a standard that you use to measure something. That standard is usually quantifiable, which means that it can be expressed numerically or statistically. Health and fitness tracking — which earlier in this chapter I said was also known as the quantified-self movement — is all about metrics and the numbers they generate: steps taken, floors climbed, hours slept, and many more.

Fortunately, these metrics are mostly straightforward, but even apparently simple metrics — such as the number of steps you take in a day — have subtle nuances that you need to understand. I spend the rest of this chapter going through the seven metrics — steps taken, distance covered, floors climbed, active minutes, heart rate, calories burned, and sleep time — tracked by most Fitbits.

Steps taken

Fitbit made its name as a simple and easy-to-use step tracker, also known as a pedometer. To this day, the number of steps taken daily (see Figure 1-5) remains the device’s most iconic and familiar metric. That steps get pride-of-place on your Fitbit isn’t surprising because the humble step is an indication of activity. Taking a step means you’re not sitting down or standing in one spot, both of which, if done to excess, are bad for your health. You can’t get or stay fit without movement, so a step is, well, a step in the right direction.

FIGURE 1-5: Your Fitbit tracks the number of steps you take each day.

“Wait a minute,” I hear you ask. “If the Fitbit goes on my wrist, how does it know what my feet and legs are doing? Excellent question! The answer is that each Fitbit comes with an accelerometer, which is a special sensor designed to detect movement (especially acceleration) and convert that movement into data. A Fitbit can detect steps from your wrist because it assumes that you swing your arms while you move. If a given arm swing’s overall motion, speed, acceleration, frequency, and distance surpass a predefined threshold, Fitbit’s step-counting algorithm identifies your movement as a step and adds that step to your total.

This algorithm works fairly well, particularly because the accelerometer can detect movement along three axes: forward-back, left-right, and up-down. However, you can fool the algorithm in several ways:

- If your Fitbit-wearing arm is still or moves only a little as you walk (or run), your steps might not get counted. Fortunately, this tendency to miss steps when your arm is still usually doesn’t apply when you’re pushing a stroller or a shopping cart.

- In an activity that includes vigorous arm motions without steps — such as shoveling snow and digging holes — those arm motions get counted as steps. I don’t view these extra steps as unearned because, let’s face it, shoveling and digging are hard.

- If you vigorously swing your arm in a walking or running motion while sitting down or standing in place, those arm swings are counted as steps.

So, yes, it’s possible to cheat your step count by swinging your Fitbit-shod arm while not moving. Of course, you would never do that because you know as well as I do that you’re only cheating yourself, right? Right?

Distance covered

Suppose you walk 10,000 steps today and then walk another 10,000 steps six months from now. Suppose, too, that you were exercising regularly during those six months. Does the fact that you did the same number of steps mean that your fitness didn’t improve over that time? Not necessarily. If the second time around you covered a greater distance, you got more out of those steps by walking at a faster pace.

Being able to compare how far a given number of steps takes you is, in a nutshell, why the metric of distance covered is important. If you can walk (or run) farther given the same number of steps — or the same elapsed time — your fitness is improving.

Also, distance on its own (that is, without reference to the number of steps involved) is important for runners and cyclists. If you’re training for your first 10K race, you need to set up your program to build your distance slowly until you know you can complete the 10K distance.

It might seem weird that a wrist-based device can figure out how far you’ve traveled during a walk or run (see Figure 1-6). But a Fitbit can calculate distance in not one but three ways:

-

A Fitbit Ionic watch has an on-board Global Positioning System (GPS) receiver, so it can use that GPS signal to follow your location and calculate your distance automatically.

Both the Ionic and the Versa use GPS only for distance-related activities (such as runs and walks) initiated by the Exercise app (see Chapter 9). The Ionic and the Versa don’t use GPS for regularly tracked activities.

Both the Ionic and the Versa use GPS only for distance-related activities (such as runs and walks) initiated by the Exercise app (see Chapter 9). The Ionic and the Versa don’t use GPS for regularly tracked activities. - A Fitbit Versa watch or a Charge 3 or Inspire wristband can connect to your smartphone’s GPS receiver and calculate your distance by using that signal.

- All other Fitbit devices that track distance do so by multiplying the number of steps you take by the length of your stride. Wait, what! How can a Fitbit know your stride length? Fitbit calculates stride length automatically by using the height and gender info you supply when you first set up your Fitbit account (see Chapter 3). Actually, Fitbit makes two calculations: your walking stride length and your running stride length.

FIGURE 1-6: Some Fitbits tell you the distance you cover daily.

Floors climbed

Walking along level ground is a fantastic way to get fit and feel better. However, you can quickly and easily kick your fitness program into a higher gear by adding ascents to your walks. These climbs can be the stairs at home or at work, a local street with a steep incline, or a park or similar natural setting with one or more hills. Whatever the ground you’re climbing, going up is always harder than staying level, and the steeper the climb the harder the workout.

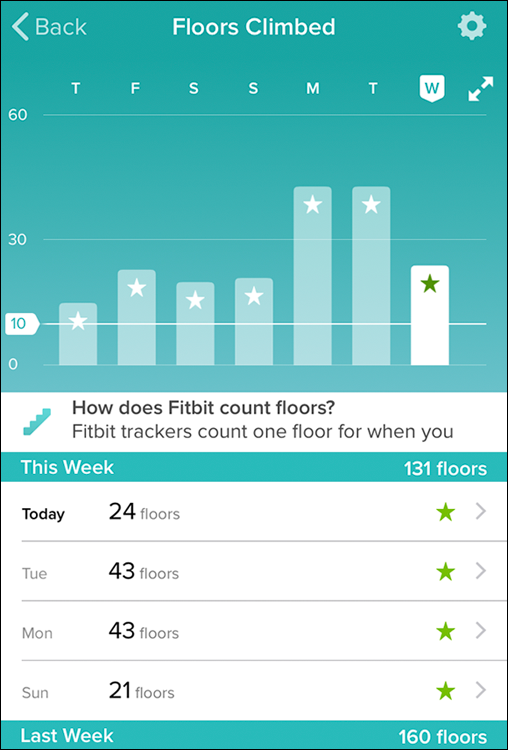

Certain Fitbit devices can track the number of floors you climb each day (see Figure 1-7). These devices contain a sensor called an altimeter, which detects changes in elevation. Whenever the altimeter detects that you’ve climbed ten feet, it adds a floor to your total. Alas, the altimeter ignores negative elevation changes, so you get no credit for going down!

FIGURE 1-7: A few Fitbits track the number of floors you climb each day.

You might be wondering whether you would get climbing credit for cranking up the incline on a treadmill or using a StairMaster? Nope, sorry. The altimeter detects changes in barometric pressure, so your Fitbit has to physically move up in elevation to get credit for a climb.

Active minutes

The worst thing you can do for your health is nothing. Sitting is especially bad, but standing in one place isn’t much better. If you want to be fit, the prescription couldn’t be simpler: You have to move. Although any movement is good, however, not all types of movement count the same for your long-term health. For example, a leisurely stroll is a fine thing to do, but it’s not going to boost your fitness much. Instead, most experts suggest at least 150 minutes of moderate physical activity per week. What does moderate mean? Basically, it’s any activity that raises your heart rate a little, such as the following:

- Walking at a brisk pace (at least three miles per hour)

- Playing tennis

- Raking leaves and similar yard work

In the Fitbit tracking world, if you perform these types of activities for at least ten minutes, that time is added to your active minutes metric, shown in Figure 1-8. Your Fitbit doesn’t know what you’re doing, of course, but its accelerometer can measure the intensity of your effort, which determines whether the time is counted as active minutes. Even better is a Fitbit with a built-in heart rate monitor (see the next section), because heart rate is a more accurate indicator of an activity’s intensity.

FIGURE 1-8: Some Fitbits can track your daily number of active minutes.

Heart rate

What’s the difference between a languid stroll and a brisk walk, or a slow jog and a fast run? In a word, the stroll and the jog are easier than the walk and the run. Your Fitbit can sense this difference to a certain extent based on the intensity of your arm swings, which tend to be shorter and slower during more leisurely paced activities, and then get longer and faster as you ramp up your speed.

However, another key difference exists between a stroll or jog on one side of the activity spectrum and a brisk walk or run on the opposite end: For the latter, your heart rate — measured in beats per minute (bpm) — climbs higher the faster you go.

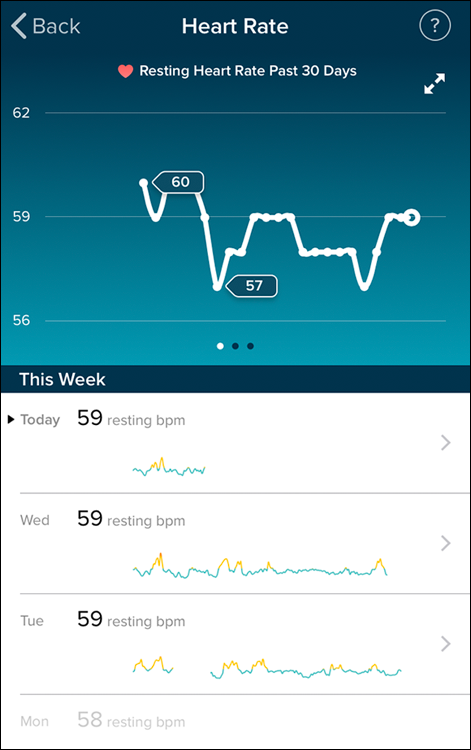

Being able to put a number, such as beats per minute, to an effort is more accurate and more trackable over time than arm-swing intensity, which is why some Fitbits come with built-in heart rate monitors.

If you’ve had any experience with heart rate monitors in the past, you know that the standard setup is a combination of a strap that holds the heart rate sensor to your chest, relatively close to your heart, and a device, such as an exercise watch or smartphone app, that reads the sensor’s heart rate data. Using a heart rate monitor is, in short, a hassle.

That hassle disappears when you use a Fitbit to monitor your heart rate, as shown in Figure 1-9, because you don’t have to strap on extra devices. Instead, the Fitbit comes with one or more light-emitting diodes (LEDs) on the back (Fitbit calls them PurePulse LEDs). These LEDs reflect onto the skin to detect blood volume changes, which are the telltale signs of your capillaries (small blood vessels) expanding and contracting as your heart beats.

FIGURE 1-9: A few types of Fitbits have onboard heart rate monitors.

Do these LEDs provide an accurate hear rate? For the most part, yes, particularly when you’re at rest or moving moderately. Heart rate detection problems can crop up during higher-intensity exercise and during activities that require frequent wrist bending (such as weight lifting) or vigorous, non-rhythmic arm movements (such as martial arts). I talk more about heart rate monitoring in Chapter 7.

Calories burned

If your interest in self-tracking is mostly as an aid to losing weight or maintaining your current weight, tracking the calories you burn each day is crucial. The direction your weight goes depends mostly on calories:

- To lose weight: The calories you take in during the day must be less than the calories you burn.

- To maintain weight: The calories you consume must be roughly the same as the calories you burn.

Some confounding factors exist; for example, muscle weighs more than fat, so any activity that replaces fat with muscle will often cause you to gain weight. But in general, the difference between calories in and calories out determines whether and how your weight changes.

Fitbit enables you to monitor the “calories in” part of the equation by its daily food log, where you enter what you consume by hand or by scanning a food item’s barcode, if it has one. From this information, Fitbit automatically calculates the total calories from its food database. For more details about tracking food, see Chapter 10.

For the “calories out” part of the calculation, Fitbit first determines the rate at which you burn calories to perform standard bodily functions such as your heartbeat, breathing, and brain activity. This calculation is called you basal metabolic rate (BMR), and Fitbit determines it based on your height, weight, age, and gender. Fitbit also estimates calories burned based on the intensity and duration of activities and exercises, as well as your heart rate, if your Fitbit measures that. With these three measurements — BMR, activity, and heart rate (if available) — your Fitbit tracks your daily calories burned as a metric, as shown in Figure 1-10.

FIGURE 1-10: Most Fitbits use your BMR and activities to track daily calories burned.

Sleep time

If you don’t get enough sleep on a particular night, you’ll probably still be able to function normally the next day, perhaps with a few extra yawns. But if you don’t get enough sleep for many nights in a row, numerous studies have shown that you’ll experience some significant physical and cognitive decline.

Suppose that you try to counteract the nastiness of chronic sleep deficit by going to bed at 11 p.m. and waking up at 7 a.m. Eight hours of solid sack time means problem solved, right? Not so fast. Sure, you might have been in bed for eight hours, but were you sleeping the entire time? Or were you restless during the night? Did you rouse yourself one or more times? Did you wake up at 6:30 a.m. and lie there until your alarm went off at 7:00 a.m.? You may have actually slept as little as six or seven hours. Problem most definitely not solved.

Knowing how much sleep you’re really getting is difficult because being objective about the quality of your sleep is difficult. Fortunately, your Fitbit is here to help by monitoring your sleep and reporting the results as the amount of time you were awake, restless, and asleep, as shown in Figure 1-11. Even better, if your Fitbit has a heart rate monitor, it can break down your sleep time into sleep stages, such as light sleep or REM sleep. I explain how the Fitbit tracks sleep patterns in Chapter 6.

FIGURE 1-11: Most Fitbits can track your daily sleep time.