Polish in writing requires not only grammatical consistency and simplicity but also the avoidance of unnecessary jargon. Every profession has its own jargon. In a medical record, you shouldn’t be surprised to read that the doctor “observed a fungal infection of unknown etiology on the upper lower left extremity.” For some doctors, the word etiology (meaning “cause”)—as well as dozens of other phrases such as the patient is being given positive-pressure ventilatory support (meaning “the patient is on a ventilator”)—reinforces one’s identity as a doctor.

Similarly, in police reports you’ll frequently encounter passages like this one:

When Officer Galvin entered the lot, he observed the two males exiting the lot. He then initiated a verbal exchange with a female white subject, who stated that she had observed two male whites looking into vehicles. When she pointed out the subjects as the two male whites who had exited the lot previously, Officer Galvin promptly engaged in foot pursuit of them.

All this gets recorded with a straight face. For the police officer, linguistic oddities such as engaging in foot pursuit of (meaning “running after”)—as well as absurdly formal word choices like observed (“saw”), exiting (“leaving”), initiated a verbal exchange (“spoke”), stated (“said”), male whites (“white men”)—are part of what makes one feel like a genuine police officer. But make no mistake: they do not contribute to precision—nor even to the “clinical” nature of the description.

Similar types of unnecessary jargon afflict most lawyer talk.

To the educated person who isn’t a doctor, a police officer, or a lawyer, those who use jargon sound more than a little silly.

Consider something as commonplace as a law firm’s jarringly antiquated e-mail disclaimer, full of verbosity and legalese:

The foregoing message may, in whole or in part (including but not limited to any and all attachments hereto), contain confidential and/or privileged information. If you are not the addressee denominated in the foregoing recipient box designated for the purpose of such denomination, or you are not a person or persons authorized to receive this message for said recipient, then you must not use, copy, disclose, or take any action on said message or on any information hereinabove and/or hereinbelow. If said message has been received by you in error, please advise the sender forthwith by reply e-mail and delete said message. Unintended transmission of said message shall not constitute a knowing waiver of attorney-client privilege or of any other privilege to which the unintentional sender may be entitled at law or in equity.

That ludicrous disclaimer reflects negatively on the sender. Instead, it could be much more direct:

This message, together with any attachments, may contain privileged or confidential information. Unless you’re the intended recipient, you cannot use it. If you’ve received this e-mail by mistake, please reply to let us know and then permanently delete it. We don’t waive any privilege with misdelivered e-mail.

What a different impression the revised version conveys.

When first studying law, you labor to acquire legalese (it’s something you must understand). But if you ultimately hope to write well, you must labor to give it up in your own speech and writing—that is, if you want to speak and write effectively. Legalisms should become part of your reading vocabulary, not part of your writing vocabulary.

But what, exactly, is a legalism? The term refers not to unsimplifiable terms of art (like habeas corpus) but to legal jargon that has an everyday English equivalent. Among the extreme examples are these:

Legalism |

Plain English |

anent |

about |

case sub judice |

this case |

dehors the record |

outside the record |

inter sese |

among themselves |

motion for vacatur |

motion to vacate |

sub suo periculo |

at one’s own peril |

These examples are extreme because few legal writers use them today. They don’t present much of a threat to your writing style because you’ll be sensible enough to avoid them.

The real danger comes with commonplace legalisms that inhabit every paragraph of murky legal writing:

While these and other legalisms might seem precise, they don’t lend precision to the discussion. They’re no more precise than the ordinary words.

In the following example, the drafter’s fondness for said, same, and such has produced an unnecessarily opaque tongue-twister:

The Undersigned hereby extends said lien on said property until said indebtedness and Loan Agreement/Note as so modified and extended has been fully paid, and agrees that such modification shall in no manner affect or impair said Loan Agreement/Note or the lien securing same and that said lien shall not in any manner be waived, the purpose of this instrument being simply to extend or modify the time or manner of payment of said Loan Agreement/Note and indebtedness and to carry forward the lien securing same, which is hereby acknowledged by the Undersigned to be valid and subsisting.

With a little effort—and by giving “the Undersigned” a name—it’s possible to boil that legal gibberish down to this:

Williams extends the lien until the Note, as modified, has been fully paid. The modification does not affect any other terms of the Note or the lien, both of which otherwise remain in force.

Lawyers recoil from this type of edit until they’ve acquired some experience. But with experience and insight comes the knowledge of just how unnecessary legal claptrap is.

Acquire that knowledge ravenously, and you might short-circuit years of befuddlement.

Basic

Translate the following passages into plain English:

• A prehearing conference was held on July 15, 2010, and the result of said conference was that Rawson was given an extension of time until August 6 to respond to Vicker’s motion. Rawson subsequently failed to file any response thereto.

• In the event that any employee is requested to testify in any judicial or administrative proceeding, said party will give the company prompt notice of such request in order that the company may seek an appropriate protective order.

• The court asks whether the plaintiff is guilty of unreasonable delay in asserting its rights. Such determination is committed to the trial court’s sound discretion. The emphasis is on the reasonableness of the delay, not the length of such delay.

• Subsequent to the Bank’s dishonor and return of the forged check, the U.S. Attorney served the aforementioned subpoena upon the Bank and directed the Bank to deliver to his office forthwith, upon receipt, at any time and from time to time, any and all bank checks, cashier’s checks, and similar items stolen in the robbery that transpired on July 2, 2010.

Intermediate

Translate the following passages into plain English:

• All modifications, interlineations, additions, supplements, and/or changes to this Contractual Amendment are subject to and conditioned upon a fully executed, signed, and dated acceptance, approval, and confirmation at Pantheon’s corporate headquarters.

• An interpreter is needed if, after examining a witness, the court arrives at the conclusion that the witness is without the ability to understand and speak English at a sufficient level of proficiency to comprehend the proceedings in such a way as to assist counsel in the conduct of the case.

• This letter shall confirm our understanding and agreement that if your loan application on the above-described property is approved, you shall occupy the same as your primary residence within thirty (30) days of the closing date. You are aware that if you shall fail to do so, such failure shall constitute a default under the Note and Security Instrument executed in connection with your loan, and upon occurrence of such default the full and entire amount of the principal and interest payable pursuant to said Note shall become immediately due and payable at the option of the holder thereof.

• Pursuant to the provisions of §§ 3670, 3671, and 3672 of the Internal Revenue Code of the United States, notice is hereby given that there have been assessed under the Internal Revenue Code of the United States, against the following-named taxpayer, taxes (including interest and penalties) which after demand for payment thereof remain unpaid, and that by virtue of the above-mentioned statutes the amount (or amounts) of said taxes, together with penalties, interest, and costs that may accrue in addition thereto, is (or are) a lien (or liens) in favor of the United States upon all property and rights to property belonging to said taxpayer.

Advanced

Find a published piece of legal writing that is thick with legalese. Prepare a short memo—no more than three pages—in which you (1) show at least two paragraphs from the original, (2) show how you would edit the passage, and (3) explain briefly why you made your edits. If possible, cite authority (such as a usage guide—see § 48) in support of your edits.

or

Review three of the following books and write a summary of what they say about using plain language:

• Mark Adler, Clarity for Lawyers: The Use of Plain English in Legal Writing (2d ed. 2007).

• Rudolf Flesch, How to Write Plain English: A Book for Lawyers and Consumers (1979).

• Joseph Kimble, Lifting the Fog of Legalese: Essays on Plain Language (2006).

• David Mellinkoff, The Language of the Law (1963).

• Peter M. Tiersma, Legal Language (2000).

Despite many notable exceptions—as in “I think, therefore I am,” “To be or not to be,” or “It depends on what the meaning of is is”—be-verbs often lack force. When they appear frequently, the writing can become inert. Legal writers often overindulge, as in these passages:

• If there is information to which the company has reasonable access, the designated witness is required to review it so that the witness is prepared on all matters of question.

• Affecting vitally the problem of the burden of proof is the doctrine of presumptions. A presumption occurs in legal terminology when the fact-trier, whether a court or a jury, is required from the proof of one fact to assume some other fact not directly testified to. A well-known example is the presumption that a person is dead after seven years if he or she has been shown to have been absent for seven years without being heard from.

We can recast each of those passages with better, more picturesque verbs:

• If the company has reasonable access to information, the designated witness must review it to prepare for all matters of questioning.

• The doctrine of presumptions vitally affects the burden-of-proof issue. A presumption occurs in legal terminology when the fact-trier, whether a court or a jury, must deduce from one fact yet another that no one has testified about directly. For example, the law presumes that a person has died if that person has been absent for seven years without being heard from.

As you might gather, relying on is and its siblings can easily turn into a habit. And wherever you find the various forms of the verb to be congregating, you’re likely to find wordy, sluggish writing. Although the English language actually has eight be-verbs—not only is, are, was, and were but also been, being, be, and am—this section targets the big four. They’re the ones that you’ll need to focus on most. So mentally—or even physically—highlight every is, are, was, and were, and see whether you can improve the sentence by removing it.

Many writers, by the way, erroneously believe that a be-verb always signals passive voice. In fact, it’s only half of the passive-voice construction (see § 9). But even if be-verbs don’t always make sentences passive, they can certainly weaken your prose on their own. So they merit your critical attention.

Exercises

Basic

Rewrite the following sentences to eliminate the be-verbs:

• Jones is in agreement with Smith.

• The professional fees in this project are entirely dependent upon the planning techniques that the client is in favor of implementing.

• The judge is of the opinion that it is within sound judicial discretion to determine whether, once the claim is asserted, the crime-fraud exception is applicable.

• Where there is no express agreement, it is ordinarily taken that the authority was to last for what was a reasonable time in light of all the circumstances.

Intermediate

Rewrite the following passages to eliminate the be-verbs:

• There was no light-duty work that was available at the company. The company’s actions were hardly discriminatory when there was no showing that the company was practicing any type of discriminatory preference.

• Several members were in attendance, and those present were in agreement that the board’s action was violative of the bylaws.

• This evidence is indicative that the company was desirous of creating a monopoly with the operating system.

• Since there is a limited number of persons with the requisite skills, it is increasingly difficult for the company to hire personnel who are qualified.

In a piece of published legal writing, find two meaty paragraphs—consecutive ones—in which be-verbs predominate. Type the paragraphs, preserve an unedited version, and then revise them to reduce the number of be-verbs by at least 75%. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy of the before-and-after versions to each colleague.

In working to shorten sentences, phrase by phrase, you’ll need to become a stickler for editing out the usual suspects—the recurrent phrases that bloat legal writing. Each one typically displaces a single everyday word:

Bloated Phrase |

Normal Expression |

an adequate number of |

enough |

a number of |

many, several |

a sufficient number of |

enough |

at the present time |

now |

at the time when |

when |

at this point in time |

now |

during such time as |

while |

during the course of |

during |

for the reason that |

because |

in the event that |

if |

in the near future |

soon |

is able to |

can |

notwithstanding the fact that |

although |

on a daily basis |

daily |

on the ground that |

because |

prior to |

before |

subsequent to |

after |

the majority of |

most |

until such time as |

until |

You’ll need to remember this list—and the reliable one-word translations.

More than that, though, you can strengthen your writing by cultivating a skepticism toward the one word in the English language that most commonly signals verbosity: of. Although this may sound simplistic, it actually works: focus on each of to see whether it’s propping up a wordy construction. You might be surprised at how often it does that. When editing on a computer, try searching for “[space]of[space]” to see how many ofs you can safely eliminate. Reducing the ofs by 50% or so can greatly improve briskness and readability. With a little experience, you’ll find that you carry out three or four predictable edits.

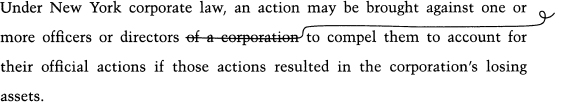

First, you’ll sometimes delete a prepositional phrase as verbiage:

Although the edit may seem minor, deleting of a corporation helps streamline the sentence. This edit—by which you brand the of-phrase needless—is especially common in phrases such as the provisions of and the terms and conditions of. Instead of writing that an agency’s actions are “subject to the provisions of the 2010 legislation,” simply write that they are “subject to the 2010 legislation.” Phrases like the provisions of typically add nothing.

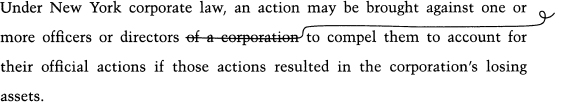

Second, you’ll sometimes change an of-phrase to a possessive form. For example:

That’s an easy edit. It also puts a punch word at the end of the sentence (see § 11).

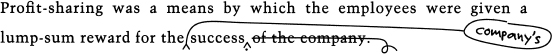

Third, you’ll sometimes replace a prepositional phrase with an adjective or adverb. For example:

Although we might want to keep one of in the final phrase, we’ll need to delete the other one and use California as an adjective.

Finally, you’ll often just find a better wording. For example:

This edit is especially common with -ion words, as here:

Changing effectuation to effectuate immediately eliminates a preposition and improves the style.

Selectively deleting ofs is surprisingly effective: even the most accomplished writer can benefit from it.

Exercises

Basic

Revise these sentences to minimize prepositions:

• Jenkins knew of the existence of the access port of the computer.

• This Court did not err in issuing its order of dismissal of the claims of Plaintiff.

• Courts have identified a number of factors as relevant to a determination of whether the defendant’s use of another’s registered trademark is likely to cause a state of confusion, mistake, or deception.

• One way in which a private party can act preemptively to protect the enforceability of the rest of the provisions of a contract, in the face of one void provision, is to insert a severability clause.

• Any waiver of any of the provisions of this Agreement by any party shall be binding only if set forth in an instrument signed on behalf of that party.

Intermediate

Revise the following passages to minimize prepositions:

• Henry II had genius of a high order, which never manifested itself more clearly than in his appreciation of the inevitability of the divergence of the paths of crime and of tort, and in his conception of crimes as offenses against the whole community.

• The recognition of the propriety of a court’s overruling its own decisions places those decisions on the plane of merely persuasive authority and causes our theory of judicial precedent to be substantially like the theory held on the continent of Europe.

• Penfold had no knowledge of the amount of money paid—and could not have had knowledge of this—in advance of Penfold’s review of its financial position in 2010. Thus, Penfold’s profit-sharing is neither deserving of nor subject to the protections of Title III.

• In the case of R.E. Spriggs Co. v. Adolph Coors Co., 94 Cal. App. 3d 419 (Ct. App. 1979), the Court of Appeal of California addressed the estoppel effect of a cease-and-desist order. The court was of the view that the trial court erred in failing to apply the doctrine of collateral estoppel, since the factual issue in dispute had been litigated and decided in an earlier case involving the enforcement of an FTC cease-and-desist order.

• One or both of the aspects of the function of the court must suffer. Either consideration of the merits of the actual controversy must yield to the need of detailed formulation of a precedent that will not embarrass future decision, or careful formulation must give way to the demand for study of the merits of the case at hand.

Advanced

Find a published passage in which you can improve the style by cutting the ofs by at least half. Type the original, and then handwrite your edits so that they’re easy to follow. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy to each of your colleagues.

It’s not just passive voice (§ 9) and be-verbs (§ 13) that can sap the strength from your sentences. So can abstract nouns made from verbs. Avoid using words ending in -ion when you can. Write that someone has violated the law, not that someone was in violation of the law; that something illustrates something else, not that it provides an illustration of it; that a lawyer has decided to represent the defendant, not that the lawyer has made the decision to undertake the representation of the defendant; that one party will indemnify the other, not that the party will furnish an indemnification to the other.

In each of those alternatives, there’s the long abstract way of saying it, and there’s the short concrete way. The long way uses weak verbs and abstract nouns ending in -ion. The short way uses a straightforward verb. Legal writing is full of flabby phrases containing -ion words:

Wordy |

Better Wording |

are in mitigation of |

mitigate |

conduct an examination of |

examine |

make accommodation for |

accommodate |

make adjustments to |

adjust |

make provision for |

provide for |

provide a description of |

describe |

submit an application |

apply |

take into consideration |

consider |

Of course, when you need to refer to mediation or negotiation as a procedure, then you must say mediation or negotiation. But if a first draft refers to the mediation of the claims by the parties, you might well consider having the second draft refer to the parties’ mediating the claims.

Why concentrate on editing -ion words? Three reasons:

• You’ll often avoid inert be-verbs by replacing them with action verbs (see § 11).

• You’ll generally eliminate prepositions in the process, especially of (see § 14).

• You’ll humanize the text by saying who does what.

The underlying rationale in all this is concreteness. By uncovering buried verbs, you make your writing much less abstract—it becomes far easier for readers to visualize what you’re talking about.

If you still have doubts, compare that preceding sentence with this one: “After the transformation of nominalizations, the text will have fewer abstractions; readers’ capability for visualization of the discussion is enhanced.”

Be alert to words ending in -ion. When you can, eliminate them.

Exercises

Basic

Improve the following passages by changing all but one or two of the -ion words. Do any -ion words need to stay?

• An interested party may make an application for a modification or revocation of an antidumping order (or termination of a suspension agreement) in conjunction with an annual administrative review. A revocation application will normally receive no consideration by the board unless there have been no sales at less than fair value for a period of at least three consecutive years.

• In analyzing the ADA claim, the court noted that the decedent’s termination and the reduction in AIDS benefits by the company occurred before the ADA became effective. Plaintiff nonetheless made the allegation that maintaining the limitation on AIDS benefits beyond the effective date of the ADA—in effect discrimination between plan members with AIDS and members without AIDS—constituted a violation of the general rule of Title I.

• The determination that reasonable grounds exist for the revocation of parole should first be made by someone directly involved in the case. Yet we need make no assumptions in arriving at the conclusion that this preliminary evaluation, and any recommendations resulting therefrom, should be in the hands of someone not directly involved.

Intermediate

Edit the following sentences to reduce the number of words ending in -ion:

• In the event of termination of this Agreement by Sponsor before expiration of the project period, Sponsor must pay all costs that the University has accrued as of the date of termination.

• The federal district courts have discretion over supervision of the discovery process, the imposition of sanctions for discovery violations, and evidentiary rulings.

• Although compliance with the terms of the Act should provide Hince some protection from state or local actions, the actual degree of protection remains uncertain because of the absence of any prior judicial interpretation of the Act.

• Any violation of the terms of probation established by the Board will result in revocation of VanTech’s authority to conduct itself as a public-utility operation.

• In addition, the imposition of punitive damages here would be a violation of the constitutional provision containing the prohibition of ex post facto laws.

Advanced

Find a paragraph in published legal writing with at least three - ion words that need editing. Retype the paragraph, with its citation, and then type your own revised passage below it. If you’re a member of a writing group or class, circulate a copy of your page to each colleague, and be prepared to discuss your work.

or

Research the literature on effective writing for additional support for eliminating -ion words. What are the various terms that writing authorities use for these words?

Legal writing is legendarily redundant, with time-honored phrases such as these:

alienate, transfer, and convey (transfer suffices)

due and payable (due suffices)

give, devise, and bequeath (give suffices)

indemnify and hold harmless (indemnify suffices)

last will and testament (will suffices)

The list could easily be lengthened. Perhaps you’ve heard that these strung-along synonyms once served a useful purpose in providing Latin, French, and Anglo-Saxon translations when legal language was not fully settled. This explanation is largely a historical inaccuracy.6 But even if it were accurate, it would have little relevance to the modern lawyer.

The problem isn’t just that doublets and triplets, old though they may be, aren’t legally required. They can actually lead to sloppy thinking. Because courts must give meaning to every word—reading nothing as mere surplusage7—lawyers shouldn’t lard their drafts with unnecessary words. The idea isn’t to say something in as many ways as you can but to say it once as well as you can.

To avoid needless repetition, apply this rule: if one word swallows the meaning of other words, use that word alone. To put it more technically, if one term names a genus of which the other terms are merely species—and if the genus word supplies the appropriate level of generality—then use the genus word only. Hence use encumbrances alone, not liens and encumbrances—which wrongly suggests that a lien is not an encumbrance. And if the two words are simply synonyms (convey and transport), simply choose the one that fits best in your context.

What about indemnify and hold harmless? Is there a nuanced distinction? Historically, and in most states today, no. But in some states, yes: courts have fabricated a historical distinction between indemnify and hold harmless on the assumption that every word must be given effect. For the full story—a rather sad one—see Garner’s Dictionary of Legal Usage (3d ed. 2011) under indemnify.

Exercises

Basic

Edit the following sentences to eliminate the redundancies without changing the meaning:

• Licensee will perform the work in compliance with all applicable laws, rules, statutes, ordinances, and codes.

• A party may not challenge a witness’s truthfulness and veracity by the introduction or injection of extrinsic evidence relating to matters not already in the record.

• If the bailee fails, refrains, or refuses to perform any obligation under this agreement, the bailor may, at its option, perform the obligation of the bailee and charge to, bill, or otherwise recover from the bailee the cost of this performance.

• Seller must cooperate with and assist Buyer in this process, without bearing the costs or expenses associated therewith.

Find two examples of doublets or triplets in your apartment lease, mortgage, car-loan agreement, or other personal contract. Suggest a revision that eliminates the redundancy without (in your opinion) changing the meaning. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy of the before-and-after versions to each colleague.

Advanced

In the literature on legal language, find at least three discussions of the origin and modern use of doublets and triplets. Write a short essay (300-500 words) reporting your findings.

Imagine a world in which all novelists used the terms “Protagonist” and “Antagonist” as the names of their principal characters. Assume that playwrights and screenwriters did the same. The stories would grow tedious, wouldn’t they?

Legal writers have traditionally spoiled their stories by calling real people “Plaintiff” and “Defendant,” “Appellant” and “Appellee,” or “Lessor” and “Lessee.” It’s a noxious habit that violates the principles of good writing.

You can do better: call people McInerny or Walker or Zook. Or refer to the bank or the company or the university. (If you want to—if you’re feeling particularly nervous—you can capitalize them: the Bank, the Company, or the University. But see § 18.) Then make sure your story line works. Do what you can, however, to avoid legal labels as party names.

Most people, you see, don’t think of themselves as intervenors, mortgagors, obligors, prosecutrixes, and the like. Even lawyers end up having to backtrack and continually translate. You’re better off supplying the translations in advance.

By the way, you’ll sometimes hear litigators say that it’s a good idea to humanize your client (Johnson) while dehumanizing your adversary (Defendant). This advice is almost always unsound: it not only makes your writing halfway dull but also suggests that you lower yourself to transparently cheap tricks. Besides, if your adversary has really done bad things, the reader will readily associate those bad acts with a name (Pfeiffer) but won’t with a legalistic label (Defendant).

Yet the preference for real names does have two limited exceptions: (1) when you’re briefly discussing a case other than the one you’re currently involved in, the plaintiff and the defendant (both lowercase) may work fine; and (2) when multiple parties are aligned in such a way that a single name is inaccurate, as in a class action, you may need Plaintiffs or Defendants (capitalized). Otherwise, use real names for parties—even your opponents.

As for -or/-ee correlatives, they typify poor legal drafting: indemnitor/indemnitee, licensor/licensee, mortagagor/mortgagee, obligor/obligee, etc. They have three major drawbacks. First, using such pairs means that you are differentiating the parties with nothing but a two-character suffix: you’re inviting typographical errors, misreadings, and confusion. Second, you’re making your document look as if you copied it from a formbook—and it is understandable that people will think you did just that. Third, you will review your own work less attentively if you use these boring labels—and you are therefore more likely to make substantive mistakes.

You are much better off personalizing your documents by using particular names, whether you’re preparing pleadings, briefs, or transactional documents.

Exercises

Basic

Rewrite the following paragraph from a summary-judgment brief. Substitute names for procedural labels. Assume that the movant (your client) is Pine National and that the plaintiff is Peter Foster. You’ll undoubtedly see the need for other edits, so improve the style as best you can.

Movant has conclusively established that Plaintiff did not initiate this lawsuit against Movant until after the expiration of the applicable limitations period. Plaintiff does not dispute this. Instead, Plaintiff seeks to avoid application of the limitations bar by (1) asserting that this is a case of misnomer, in which case limitations would be tolled, and (2) asserting that, under Enserch Corp. v. Parker, 794 S.W.2d 2, 4-5 (Tex. 1990), factual issues exist as to whether Movant was prejudiced by the late filing. Yet the evidence before the Court establishes as a matter of law that this is a case of misidentification (which does not toll limitations), not one of misnomer. Further, Plaintiff has not responded with any proof of a basis for tolling limitations under the equitable exception to the statute of limitations described in Enserch. The exception is inapplicable under the facts before this Court, and, therefore, prejudice or the lack thereof to Movant is not a relevant inquiry. Plaintiff’s claims against Movant are barred by limitations as a matter of law.

Intermediate

Find a legal document in which defined legal labels, such as mortagagor and mortgagee, have caused the drafter to avoid pronouns, as a result of which the style becomes embarrassingly repetitious. Rewrite a paragraph or two of the example. If you’re part of a writing group or class, provide each colleague with a copy of the example and the revision.

Advanced

Find some authority that supports (or contradicts) the idea that you should refer to parties by name. Look at the relevant literature on brief writing and contract drafting. If you’re part of a writing group or class, be prepared to discuss the authority you’ve found.

Ever read a newspaper article that begins this way?

A powerful Russian industrialist named Mikhail Khodorkovsky (hereinafter “the Industrialist” or “Khodorkovsky”), whose empire (hereinafter “the Khodorkovsky Empire”) is under investigation in the money-laundering inquiry (hereinafter “the Inquiry”) at the Bank of New York (hereinafter “the Bank”), said yesterday that a large part of the billions of dollars (hereinafter “Russian Capital”) moved through the Bank was controlled by Russian officials (hereinafter “the Officials”) who used the Khodorkovsky Empire to protect their fortunes by shipping the Russian Capital abroad before Russian markets collapsed last year (hereinafter “the Russian Collapse”).

Although that’s absurd—and no professional journalist would ever do it—many lawyers are smitten with the idea:

Gobel Mattingly (“Mattingly”), shareholder on behalf of Allied Ready Mix Company, Incorporated (“Allied”) and Jefferson Equipment Company, Incorporated (“Jefferson”), has appealed from a nunc pro tunc order (the “Nunc Pro Tunc Order”) of the Jefferson Circuit Court (the “Court Below”) in this stockholder derivative action (“the Action”).

Even without hereinafters, that’s nonsense. There’s only one Mattingly, one Allied, and one Jefferson involved. And if you tell the story competently, any reader will know what order, what action, and what trial court you’re talking about. As it is, the parentheticals impede comprehension.

So if you avoid the rote, mechanical use of parenthetical shorthand names, when might you actually need them? Only when there’s a genuine need, which typically arises in just two instances. First, if you’re going to refer to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade as GATT—something you may well do because the acronym is well established (see § 19)—then you might want to do this:

Signed originally in 1948, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (“GATT”) promotes international trade by lowering import duties.

That way, the reader who encounters GATT won’t be momentarily confused. Second, if you’re writing about a case with two or more entities having confusingly similar names, a shorthand reference will dispel the confusion:

Seattle Credit Corporation (“Seattle Credit”) has sued Seattle Credit Engineering Corporation (“SC Engineering”) for trademark infringement.

Although these situations sometimes occur, they aren’t the norm.

Exercises

Basic

Rewrite the following paragraph to eliminate the shorthand names:

The statement of the procedural history of this matter, as stated in the Appellant’s brief, is essentially correct. The claimant, Keith W. Hillman (hereinafter “Hillman”), filed his claim for benefits from the Criminal Injuries Compensation Fund, Va. Code §§ 19.2-368.1 et seq., on July 27, 2010. His claim was denied by the Director of the Division of Crime Victims’ Compensation (hereinafter “the Director”) on August 27, 2010, because his conduct contributed to the infliction of his injury and because he had failed to cooperate with law enforcement. On December 20, 2010, Hillman requested a review of the denial of benefits. On April 8, 2011, Hillman was given an opportunity for an evidentiary hearing before a deputy commissioner pursuant to Administrative Bulletin No. 25, attached hereto as Addendum A (hereinafter “Add. A”).

Intermediate

Find a judicial opinion in which the parties are methodically defined at the outset. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy of the first two pages. Be prepared to discuss whether you think the definitions serve any valid purpose.

Advanced

Find a legal document in which the introduction of shorthand names seems pedantic—or, worse still, absurd. Decide how you would deal with the issue if you were the writer. If you belong to a writing group or class, be prepared to discuss your findings and your proposed solutions.

Some acronyms are fine. People don’t hesitate over ATM cards, FAA regulations, GM cars, IBM computers, or USDA-inspected beef. And lawyers are well familiar with acronyms such as ADA, DOJ, UCC, and USC.

But specialists often glory in concocting an alphabet soup that no one else finds digestible. They haven’t learned how to write in plain English. Their acronyms are shortcuts, all right—but for themselves, not for their readers. This, for example, is a word-for-word passage (only the names have been changed) from a summary-judgment opposition filed by a major law firm:

Plaintiff Valhalla Imports, Inc. (“VII”) is correct in pointing out that Maine Casualty Corporation (“MCC”) was represented at the voluntary settlement conference (“VSC”) by Matthew Tabak, a claims representative. Tabak attended the VSC as MCC’s claims representative handling Grosse’s claim against the Randall County Water District (“RCWD”), which was listed as an additional insured under MCC’s insurance policy. MCC simply was not involved in the worker’s compensation (“WC”) proceeding, had no responsibility for that proceeding, nor any duty in regard to the settlement of that proceeding, including the settlement of the serious and willful (“S&W”) application. Rather, MCC’s involvement in the facts giving rise to the action was limited to the following: MCC agreed to defend and indemnify (1) the RCWD under the insurance policy against Grosse’s civil claims, and (2) VII against RCWD’s cross-complaint. When Tabak contributed the aggregate limit of the MCC policy at the VSC, MCC did all it could do or was required to do to promote settlement.

Refuse to engage in that type of self-important obscurity. If you worry enough about your reader’s convenience, you’ll translate ideas into ordinary words that more readers—even more legal readers—can understand. Instead of the example just quoted, you might write it up as a good journalist would. Give the reader credit for having read the title that shows the full name of Valhalla. You might write something like this:

Plaintiff Valhalla correctly points out that Maine Casualty was represented at the voluntary settlement conference by Matthew Tabak, a claims representative. Tabak attended the conference as the company’s claims representative. He was handling Grosse’s claim against the Randall County Water District, which was listed as an additional insured on the Maine Casualty policy. But the company was not involved in the worker’s-compensation proceeding, had no responsibility for that proceeding, and had no duties in any of the settlement discussions in that proceeding. Rather, Maine Casualty’s involvement was limited to the following: it agreed to defend and indemnify (1) the Water District under the insurance policy against Grosse’s civil claims, and (2) Valhalla against the Water District’s cross-complaint. When Tabak contributed the aggregate limit of the insurance policy at the voluntary settlement conference, Maine Casualty did all it was required to do to promote settlement.

When it comes to overused acronyms, environmental lawyers are among the grossest offenders. In environmental law, it’s common to see discussions in which small-quantity handlers of universal wastes are defined as “SQHUW” (singular in form but plural in sense!), large-quantity handlers as “LQHUW” (again plural in sense), and conditionally exempt small-quantity generators as “CESQGs” (plural in form and in sense). Then, before you know it, you’re reading that “the requirements for SQHUW and CESQGs are similar” and that “SQHUW and LQHUW are distinguished by the amount of on-site waste accumulated at any one time.” Then, just as you’re about to master these acronyms, you see references to “SQHUW handlers” and “LQHUW handlers.” (The phrases are, of course, redundant.) Finally, when all these acronyms get intermingled with references to statutes such as RCRA, CERCLA, and FIFRA, you really do wonder what language you’re reading.

Exercises

Basic

In a law journal, find a passage that contains too many acronyms. Pick out one paragraph, type it (with citation), copy it, and then revise it to minimize the acronyms while you avoid repeating cumbersome phrases. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy of your before-and-after versions to each colleague.

Intermediate

In a book or article, find 10 to 20 acronyms. On a single page, present the acronyms together with their meanings. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy to each colleague and be prepared to discuss (1) the extent to which you think the acronyms save time in communication among specialists, (2) the extent to which you think they impede understanding for ordinary readers, and (3) the relative desirability and feasibility of making the field more understandable to more people.

Advanced

In the literature on effective writing, find two sources that discuss the use of acronyms. Distill their guidance and write a one-page report on your findings. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy to each colleague.

Whenever you write, whether you know it or not, you’re answering a question: What do you sound like? You might be stuffy (many legal writers are), whiny, defensive, aloof, or chummy. You probably don’t want to be any of those things.

Generally, the best approach is to be relaxed and natural sounding. That tone bespeaks confidence. It shows that you’re comfortable with your written voice. It’s worth remembering, as the late Second Circuit judge Jerome Frank once put it, that the primary appeal of the language is to the ear.8 Good writing is simply speech heightened and polished.

To the legal reader, few things are more pleasing than the sense that a writer is talking directly to you—one intelligent being to another. It’s unusual enough to be genuinely refreshing. Consider the following example. It’s the opener to a memorandum of law that Charles Dewey Cole Jr. of New York filed in federal court:

Grieg’s Response in Support of Denying Wilson’s Late Designation of Expert Witnesses

You wouldn’t know it from reading Wilson’s objections, but what is at stake is not Grieg’s inability to depose Wilson’s employees (or even Grieg’s inability to depose them fully). What these objections are about—and this is all that they are about—is Wilson’s unexcused failure to serve its expert-witness disclosure by the deadline: July 13, 2011. Because Wilson didn’t serve a medical report by then, Grieg assumed that Wilson would forgo medical testimony, and Grieg in turn decided against having Walim Alibrandi examined by a physician.

The plaintiffs’ attorney must have assumed that whatever injuries Mr. Alibrandi received in the collision (and they were slight indeed), the cost of a physical examination and of preparing a medical report simply wasn’t justified—an understandable decision given a comparison of that cost with the anticipated recovery. What the plaintiffs’ attorney did not anticipate was that the defendants weren’t about to settle the case, and he found himself in the unenviable position of having let the discovery deadline run without having served a medical report. And he had no excuse.

Because the plaintiffs’ lawyer had no justification for failing to serve any medical expert-witness disclosure, he dressed up his application before the magistrate judge to include all sorts of stuff about how the defendants had impeded discovery so that he couldn’t take a whole bunch of unnecessary depositions. The magistrate judge recognized this for what it was and concluded that the plaintiffs’ lawyer “had no excuse for his failure to have served his own medical expert disclosure.” So she refused to reopen the period for discovery at the October settlement conference.

The relaxed tone, achieved partly through contractions, shows confidence. The point about contractions isn’t to use them whenever possible, but rather whenever natural. Like pronouns, they make a document more readable: “Write as You Talk is the accepted rule of writing readably—and in English, the most conspicuous and handiest device of doing that is to use contractions.”9 A 1989 study confirmed this: it found that frequent contractions enhance readability.10 This advice applies not just to briefs but also to contracts, rules, and other legal documents.

A word of caution: you might not be allowed to use contractions much until you achieve a certain level of experience or seniority. The applicability of this admonition will depend on your work situation. If you’re in a junior position, you may have to be patient. My coauthor of two books, Justice Antonin Scalia, disapproved of contractions, much to my surprise—so although in our first joint book we used them throughout (he made concessions to my style), in our second book we abstained.11

What are the other characteristics of a natural, spoken style?

One is the use of first-person and second-person pronouns—especially we and you—as opposed to third-party references such as resident or mortgagor or vendee (see § 17). Readers are much more engaged by a text that speaks to them directly. For example, the U.S. Air Force years ago began to remedy the problem of unnatural, hard-to-understand language in its directives. To translate a grievance procedure into plain English, the revisers used you instead of employee. One sentence originally read:

If the employee feels that an interview with the immediate supervisor would be unsatisfactory, he or his representative may, in the first instance, present his grievance to the next supervisor in line.

That sentence is much clearer with the personal word you:

If you feel that your supervisor will not handle your case fairly, you may go directly to your supervisor’s supervisor.12

In sum, when you address readers directly, they more readily see how the text applies to them.

Another point is to begin sentences with And, But, and So—especially But. You do this in speech all the time. Good writers routinely do it in print—nearly 10% of the time.13 But legal writers often lapse into stiffer sentence openers like Similarly, However, Consequently, and Inasmuch as. Try replacing these heavy connectors with faster, more conversational ones.

Here’s a good test of naturalness: if you wouldn’t say it, then don’t write it. You’ll give your writing much more credence if you come across as sincere, honest, and genuine. Your words will be plainer, your style more relaxed, and your prose more memorable. You should probably try reading your prose aloud to see whether you’d actually say it the way you’ve written it.

Basic

Rewrite the following openers and closers from letters to make them speakable:

• Enclosed please find the following documents:

• Pursuant to your instructions, I met with Roger Smith today regarding the above-referenced cause.

• Please be advised that the discovery cutoff in the above-referenced cause is Monday, March 10, 2014.

• Pursuant to my conversation with Alex in your office on today’s date, I contacted the trustee.

• This letter is for the purpose of retaining your services as a consultant regarding the above-referenced matter.

• Thank you in advance for your courtesy and cooperation in this regard. Please do not hesitate to contact me should you have any questions regarding this request.

Intermediate

In a law review, find a long sentence or a short to medium paragraph that strikes you as particularly unspeakable. Type it, provide a citation, and set out a bulleted list of reasons why you consider it difficult to read aloud. If you belong to a writing group or class, circulate a copy to each colleague.

Advanced

In a judicial opinion, find a two-or three-paragraph passage that strikes you as being particularly unspeakable. Type it, provide a citation, and set out a bulleted list of reasons why you consider it difficult to read aloud. Rewrite the passage. If you belong to a writing group or class, circulate a copy of your before-and-after versions to each colleague.