Three good things happen when you combat verbosity: your readers read faster, you crystallize your thoughts better, and your streamlined writing becomes punchier. Both you and your readers benefit.

The following sentence, at 35 words, isn’t grossly overlong, but still it’s verbose. It comes from the Code of Federal Regulations:

It is not necessary that an investment adviser’s compensation be paid directly by the person receiving investment advisory services, but only that the investment adviser receive compensation from some source for his or her services.

Nearly two-thirds of the sentence can be cut with no loss in meaning—but with enhanced speed, clarity, and impact:

Although the investment adviser must be paid, the source of the payment does not matter.

Imagine how this type of rewriting helps over a longer span—sentence after sentence and paragraph after paragraph.

Take a longer sentence, at 79 words, from a law-review article:

Since, under the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Guidelines pertaining to sexual harassment, an employer is liable for hostile-environment sexual harassment only if it knew or should have known of the harassment and failed to take prompt and effective steps to end the harassment, it is possible for employers to be exonerated from liability for hostile-environment sexual harassment when sexual harassment has occurred by individuals within an organization, but the organization took prompt action to prevent further harassment.3

That sentence meanders. Its basic point tends to get lost in the welter of words. Cut to its essence, the thought itself seems more coherent:

EEOC Guidelines allow courts to exonerate an employer from liability for hostile-environment sexual harassment if the employer acts promptly to prevent further harassment.

At 24 words, the rewrite is less than a third the length of the original. But that figure only hints at the heightened vigor and lucidity.

The English language has vast potential for verbosity. Almost any writer can turn a 15-word sentence into a 20-word sentence that says the same thing. Many writers could make it a 30-word sentence. And a truly skilled verbiage-slinger could lard it out to 40 words without changing the meaning. In fact, almost all writers subconsciously lengthen their sentences this way.

But reversing this process is a rare art, especially when you’re working with your own prose. You’re likely to produce verbose first drafts—each sentence being probably a quarter longer than it should be. If you know this, and even expect it, you’ll be much less wedded to your first draft. You’ll have developed the critical sense needed to combat verbosity.

Meanwhile, of course, as you’re tightening your prose, you must keep it natural and idiomatic—never allowing yourself to delete words whose omission will occasion miscues for readers. Don’t delete articles (a, an, the) where they would customarily appear (School is not liable for teacher’s unforeseeable criminal acts—insert a before school and before teacher’s). And don’t delete that if doing so will cause misreadings (He denied the assertion made any difference—insert that after denied).

Exercises

Basic

Delete at least four consecutive words in the following sentences and replace those words with just one word. You may rephrase ideas and rearrange sentences, but don’t change the meaning.

• The general consensus of opinion on the court was that Business Corporation Law does not address the ability of a New York corporation to indemnify individuals who are not its employees.

• Even assuming that the fog caused the accident in which Cetera was involved, Pardone had no duty to prevent that injury because it was idiosyncratic, and Pardone could not have been expected to foresee such injury.

• At no time prior to the time of the initial public offering did the underwriters or any officers, directors, employees, or others have knowledge of any facts that would suggest that “Palm Harbor” could not be completed in a timely fashion and in accordance with specifications.

• Beale has wholly failed to allege facts that, if true, would establish that competition among the nation’s law schools would be reduced or that the public has been in any way injured, and this failure to allege facts that would establish an injury to competition warrants the dismissal of her restraint-of-trade claim.

• The court examined a number of cases and stated that there appeared to be only a limited number of instances in which there would exist a duty to disclose the illegal conduct of persons who, through political campaigns, seek to be elected to a public office.

Intermediate

Revise the following sentences to make them as lean as you can without changing the meaning:

• The County sent an inspector who made observations as to the condition of the sidewalk and concluded that it was uneven.

• Although a review of the caselaw reflects that there are no decisions in the Eleventh Circuit concerning this issue, the great weight of federal authority favors the exclusion of third parties from a Rule 35 independent medical examination.

• There is caselaw for the proposition that use restrictions are not always strictly enforced when a lease is assigned by a tenant in bankruptcy and the property in question is not part of a shopping center.

• The court appeared to premise much of its opinion upon the argument that consumers stand at a significant disadvantage in product-liability actions based on ordinary negligence principles. Consequently, strict product liability was intended to relieve the plaintiff of the burden of having to prove actual negligence.

• With respect to matters not covered by the provisions of the Uniform Rules for the New York Court of Claims (the Uniform Rules), the Court of Claims adheres to the rules set forth in the Civil Practice Law and Rules (the CPLR). Ct. Cl. R. § 206.1(c). Because the Uniform Rules do not discuss disclosure of expert witnesses, it follows that the Court of Claims’ rules on the subject are governed by the CPLR.

• There are cases that are factually similar to the present case, but that are controlled by older statutes—i.e., the pre-1965 legislative scheme. There are no cases that have been explicitly decided under § 1511 since the 1965 amendment, so it is unclear what effect the amendment has on cases that are factually similar to the present case.

• Arbitration as a means of settling disputes was at first viewed by the courts with much disfavor, but today is being used increasingly as a substitute for litigation for the adjudication of disputes arising out of contracts.

• The court rejected the defendant’s argument that the headlines were not the product of sufficient skill or effort, finding that because many of the headlines consisted of eight or so words that imparted information, copying of the headlines might at least in some instances constitute copyright infringement.

• To say that one who has contracted to serve for a number of years at a low salary or at distasteful work and seeks to better his or her condition by a contract with another party should be penalized in every case by inability to enforce this second contract seems harsh, and under these or other extenuating circumstances, the courts have often deemed damages to be sufficient recompense to the injured employer without also invalidating the second contract.

Advanced

Rewrite the following 193-word paragraph in fewer than 130 words without changing the meaning:

In addition to the two cases cited just above, both (as mentioned) dealing with the California State Bar Rules of Conduct, Rule 3-310 of the California State Bar Rules of Professional Conduct describes circumstances in which an attorney is embroiled in the representation of adverse interests. Rule 3-310 is concerned primarily with situations in which the attorney’s duty of loyalty and duty of confidentiality to clients are called into question. Therefore, to date, there are no Rule 3-310 cases disqualifying a district attorney as a result of a prosecution of an individual whom the district attorney used or is used as a witness in another prosecution. Most cases that involve district-attorney conflicts under Rule 3-310 consist of a former attorney-client relationship between an accused and a district attorney. In such cases, the rule serves to protect an accused from a prosecution in which a district attorney unfairly benefits from information gained during the course of his or her representation of the accused. Other Rule 3-310 cases involve overzealous prosecutions in cases where a district attorney is for one reason or another personally or emotionally interested in the prosecution of the accused.

or

Find a wordy sentence of at least 20 words that you can reliably cut in half without changing the meaning. Edit it. If you’re a member of a writing group or class, circulate a copy of the before-and-after versions to each colleague.

As much as any other quality, your average sentence length will determine the readability of your writing. That’s why readability formulas rely so heavily on sentence length.4

But you don’t just want a short average. You also want variety. You should have some 35-word sentences and some 3-word sentences. Just monitor your average, and work hard to keep it to about 20 words.

Unfortunately, in law many things converge to create overlong sentences. One is the lawyer’s habit of overparticularization—the wretched practice of trying to say too many things at once, with too much detail and too little sense of relevance (see § 23). Another is the fear of qualifying a proposition in a separate sentence, as if an entire idea and all its qualifications must be squeezed into a single obese sentence. A third is the nonsense baggage that so many writers lug around, such as the false notion that it’s poor grammar to begin a sentence with And or But. A fourth is the ill-founded fear of being simple (and, by implication, seeming simpleminded)—or perhaps seeming to lack sophistication.

Many legal writers suffer from these turns of mind. And the ones who do must adjust their thinking if they want to pursue a clear, readable style.

Is a 20-word goal realistic? Many good writers meet it, even when discussing difficult subjects. Consider how Professor W. W. Buckland—with an average sentence length of 13 words—summed up part of the philosopher John Austin’s thought:

Austin’s propositions come to this.[5] There is in every community (but he does not really look beyond our community) a person or body that can enact what it will and is under no superior in this matter.[32] That person or body he calls the Sovereign.[8] The general rules that the Sovereign lays down are the law.[11] This, at first sight, looks like circular reasoning.[8] Law is law since it is made by the Sovereign.[10] The Sovereign is Sovereign because he makes the law.[9] But this is not circular reasoning; it is not reasoning at all.[12] It is definition.[3] Sovereign and law have much the same relation as center and circumference.[12] Neither term means anything without the other.[7] In general what Austin says is true for us today, though some hold that it might be better to substitute “enforced” for “commanded.”[23] Austin is diffuse and repetitive and there is here and there, or seems to be, a certain, not very important, confusion of thought. [23] But with the limitation that it is not universally true, there is not much to quarrel with in Austin’s doctrine.[20]5

The style is bold, confident, and quick. More legal writers ought to emulate it.

Is this type of style achievable in law practice? You bet. Here’s a splendid example from a response to a motion to continue, by Thomas D. Boyle of Dallas:

Gunther demanded an early trial date and breakneck discovery.[9] What Gunther wanted, Gunther got.[5] But now that Findlay seeks a hearing on its summary-judgment motion, Gunther wants to slam on the brakes, complaining that it needs more time to gather expert opinions.[28] Gunther ostensibly demanded the accelerated trial date to force a prompt resolution of its claims.[15] Yet now that Gunther may have that resolution, it does not want it.[13] Must Findlay’s motion, already delayed once, be delayed again to accommodate Gunther’s tactical timetable? . . .[14]

Gunther’s motion to continue is tactical only.[7] It is no more than an attempt to gain more time to answer Findlay’s summary-judgment motion, which has already been reset once.[23] Even so, by the time Findlay’s motion is heard on August 13, Gunther will already have had eight weeks to prepare its response.[23] If Gunther wants to defeat Findlay’s motion, it need only identify a disputed fact for each point in the motion.[20] But Gunther spends much of its motion for continuance arguing the merits.[12] Rather than wasting time and money with dilatory tactics, Gunther should simply address the points in Findlay’s motion head on.[20] If Gunther shows the existence of a genuine factual issue, then so be it.[14]

Although these sentences vary in length, the average is just 15 words. The variety, coupled with the short average, improves readability and generates both speed and interest. Keeping your sentences reasonably brief can also help you divide your ideas, simplify the punctuation, and enhance the clarity of syntax.

Exercises

Basic

Break each of the following long sentences into at least three separate sentences:

• Appellee Allied Indemnity of New York respectfully suggests that oral argument would be of little benefit because the dispositive issue has been recently authoritatively decided by the Texas Supreme Court in National Union Fire Insurance Co. v. CBI Industries, Inc., 907 S.W.2d 517 (Tex. 1995), and by this Court in Constitution State Insurance Co. v. Iso-Tex, Inc., 61 F.3d 405 (5th Cir. 1995), because the facts and legal arguments are adequately presented in the briefs and record, and because the decisional process would not be significantly aided by oral argument. [91 words]

• Although no Kansas cases were found that explicitly hold that Kansas requires a corporation to have a valid business purpose in order to engage in certain specified corporate transactions, either for mergers or consolidations, or for a sale of assets followed by a dissolution and liquidation, in a 2013 Supreme Court of Kansas case involving a cash-out merger where the dissenters claimed the defendant’s board of directors breached its fiduciary duties to the dissenters, the court cited as one of the trial court’s pertinent conclusions of law that it is not necessary for a corporation to show a valid corporate purpose for eliminating stockholders. [105 words]

• The court of appeals noted that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) had already issued the applicant a National Pollution Elimination System permit for the actual discharge of wastewater, which would occur from the outfall pipe, and that the issuance and conditions of such permits were generally exempt under the Clean Water Act from compliance with the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) requirement, and accordingly the court concluded that the Corps had properly excluded the environmental implications of the discharges from the outfall pipe from its analysis and instead considered only the construction and maintenance of the pipeline itself in determining that the issuance of the permit did not constitute a major federal action. [112 words]

Rewrite the following passages to make the average sentence length under 20 words:

• At best, the lack of precise rules as to the treatment of routine corporate transactions forces investors and others who seek to understand accounting statements in all of their complex fullness to wade through pages of qualifying footnotes, the effect of which is often to express serious doubts about the meaningfulness and accuracy of the figures to which the accountants are attesting. Equally bad, while the footnotes, carefully read and digested, may enable the sophisticated analyst to arrive at a reasonably accurate understanding of the underlying economic reality, the comparison of figures published by one firm with those of any other is bound to result in seriously misleading distortions. Indeed, the figures for any given company may not be comparable from one year to the next, for although auditing standards require that the principles used by a firm must be “consistently applied” from year to year, the “presumption” of consistency may be overcome where the enterprise justifies the use of an alternative acceptable accounting principle on the basis that it is preferable. [Average sentence length: 57 words]

• It follows that in order for Wisconsin to compel school attendance beyond the eighth grade against a claim that such attendance interferes with the practice of a legitimate religious belief, it must appear either that the State does not deny the free exercise of religious belief by its requirement, or that there is a state interest of sufficient magnitude to override the interest claiming protection under the Free Exercise Clause. Long before there was general acknowledgment of the need for universal formal education, the Religion Clauses had specifically and firmly fixed the right to free exercise of religious beliefs, and buttressing this fundamental right was an equally firm, even if less explicit, prohibition against the establishment of any religion by government. The values underlying these two provisions relating to religion have been zealously protected, sometimes even at the expense of other interests of admittedly high social importance. The invalidation of financial aid to parochial schools by government grants for a salary subsidy for teachers is but one example of the extent to which courts have gone in this regard, notwithstanding that such aid programs were legislatively determined to be in the public interest and the service of sound educational policy by states and by Congress. [Average sentence length: 51 words]

• Some time subsequent thereto defendant, Brian Dailey, picked up a lightly built wood-and-canvas lawn chair that was then and there located in the back yard of the above described premises, moved it sideways a few feet and seated himself therein, at which time he discovered that the plaintiff, Ruth Garratt, was about to sit down at the place where the lawn chair had formerly been, at which time he hurriedly got up from the chair and attempted to move it toward Ruth Garratt to aid her in sitting down in the chair, whereupon, due to the defendant’s small size and lack of dexterity, he was unable to get the lawn chair under the plaintiff in time to prevent her from falling to the ground. [Average sentence length: 126 words]

• Since it is undisputed that the sugar was stolen, and that it was purchased by Johnson, the question at issue for jury determination is the state of Johnson’s mind when he purchased it. While the jury is unauthorized to convict unless it finds that Johnson himself had guilty knowledge, such knowledge may be proved by circumstances here to warrant the conclusion that Johnson, when he purchased the sugar, knew it to have been stolen and did not in fact honestly believe that the sellers were sugar dealers or were properly authorized by the Ralston Mill to sell sugar for it. In arriving at this conclusion, the jury might have considered the time and arrangements for the purchases, statements of Johnson to Gordon showing that he knew that he was taking a risk, the absence of any invoice or regular billing procedure, the contradictory statements of Johnson after his arrest, and the unlikelihood of the sellers’ having come into possession of such large quantities of sugar to be sold below wholesale price in a legal manner. [Average sentence length: 58 words]

Advanced

Find a published piece of legal writing in which the average sentence length exceeds 40 words. Rewrite it to make the average under 20.

As you edit to ensure that your sentences are of manageable length, you should think about phrasing. Are the right words appearing in the right places? A sentence has two vital elements: a subject and a predicate (typically consisting of a verb and an object or complement). It seems simple:

The partnership may buy a bankrupt partner’s interest.

But legal sentences get complicated, and legal writers often complicate them unduly by separating the vital words:

If any partner becomes a bankrupt partner, the partnership, at its sole option, exercisable by notice from the managing general partner (including any newly designated managing general partner) to the bankrupt partner (or its duly appointed representative) at any time prior to the 180th day after receipt of notice of the occurrence of the event causing the partner to become a bankrupt partner, may buy, and upon the exercise of this option the bankrupt partner or its representative shall sell, the bankrupt partner’s partnership interest.

Even if you needed some of the details in that second version, you’d be better off keeping the related words together, at the outset—and breaking the one sentence into two:

The partnership may buy any bankrupt partner’s interest. To exercise its option to buy, the managing general partner must provide notice to the bankrupt partner no later than 180 days after receiving notice of the event that caused the bankruptcy.

Why should you put the subject and verb at or near the beginning? Because readers embarking on a sentence look for the action. So if a sentence has abundant qualifiers or conditions, state those after the subject and verb. Itemize them separately if you think a list might help the reader. You’d certainly want to restructure a sentence like this one:

In the event that the Indemnitor shall undertake, conduct, or control the defense or settlement of any Claim and it is later determined by a court that such Claim was not a Claim for which the Indemnitor is required to indemnify the Indemnitee under this Article VI, the Indemnitee shall, with reasonable promptness, reimburse the Indemnitor for all its costs and expenses with respect to such settlement or defense, including reasonable attorney’s fees and disbursements.

Putting the subject and predicate up front, as well as listing the two conditions separately (see § 34), makes the sentence easier to understand:

The Indemnitee must promptly reimburse the Indemnitor for all its costs and expenses of settlement and defense, including reasonable attorney’s fees and disbursements, if:

(a) the Indemnitor undertakes, conducts, or controls the defense or settlement of any claim; and

(b) a court later determines that the claim was not one for which the Indemnitor must indemnify the Indemnitee under this Article VI.

Remember: keep related words together. So important is this principle that—as you will observe in the examples just given—it can overcome the chronological-order principle (§ 3).

Exercises

Basic

Edit the following sentences to cure the separation of related words:

• Ms. Lenderfield, during the course of her struggle to provide for her children as a single parent, accrued considerable debt to her family and others.

• Chesapeake’s assertion that it is not a proper defendant in this case and, therefore, that relief cannot be granted is incorrect.

• The court, in finding that Officer McGee was acting more as a school employee than as a police officer in searching Robinson, ruled that an official’s primary role is not law enforcement.

Intermediate

Edit the following sentences to cure the separation of related words:

• Plaintiff’s testimony that he had never had a back injury and had never been treated by a doctor for a back ailment before this workplace accident is suspect.

• The Trustee, at any time, by an instrument in writing executed by the Trustee, with the concurrence of the City Council evidenced by a resolution, may accept the resignation of or remove any cotrustee or separate trustee appointed under this section.

• In Barber v. SMH (US), Inc., the Michigan Court of Appeals held that the plaintiff’s reliance on a statement made by the defendant that “as long as he was profitable and doing the job for the defendant, he would be defendant’s exclusive representative” as establishing an oral contract for just-cause employment was misplaced.

• Taxes imposed by any governmental authority, such as sales, use, excise, gross-receipts, or other taxes relating to the equipment, except for the personal-property tax, for which Biltex, Inc. is assessed and liable by applicable law, must be reimbursed by Calburn, Inc.

Advanced

Find a published legal example of either subject-verb separation or verb-object separation. (The worse the separation, the better your example.) Retype the sentence, with the citation, and then type your own corrected version below it. If you’re a member of a writing group or class, circulate a copy of your page to each colleague, and be prepared to discuss your work.

Just as you should generally put related words together in ways that match the reader’s natural expectations, you should also state related ideas in similar grammatical form. Parallelism harmonizes your language with your thoughts. At its simplest, it’s a device for balancing lists:

Adverbs

The jury weighed the evidence carefully, skillfully, and wisely.

Adjectives

The arguments were long, disorganized, and unpersuasive.

Nouns

The facilities are available to directors, officers, and corporate counsel.

Verbs

The perpetrator drove to Minnesota, changed cars, and dropped the box on the side of the road outside St. Cloud.

The simplest, most common errors include a noun-noun-verb sequence, as here: “She was a law professor, environmental activist, and wrote mystery novels.” For the sake of parallelism, the final element should be writer of mystery novels. In legal writing, though, an almost equally common error is to intersperse parenthetical numerals in a sentence without regard for whether the enumerated items match grammatically—as here:

To prove a claim of false advertising under the Lanham Act, Omega must show that Binnergy (1) made a false or misleading statement, (2) that actually deceived or was likely to deceive a substantial segment of the advertisement’s audience, (3) on a subject material to the decision to purchase goods or services, (4) about goods or services offered in interstate commerce, (5) that resulted in actual or probable injury to Omega.

In that passage, #1 is a predicate, #2 is a subordinate clause beginning with that, #3 and #4 are prepositional phrases, and #5 is another that-clause. Let’s instead try leading off all the items with verbs, using only one that to introduce the list:

To prove a claim of false advertising under the Lanham Act, Omega must show that Binnergy made a statement that (1) was false or misleading, (2) actually deceived or was likely to deceive a substantial segment of the advertisement’s audience, (3) related to a subject material to the decision to purchase goods or services, (4) related to goods or services offered in interstate commerce, and (5) resulted in actual or probable injury to Omega.

Many grammatical constructions require parallelism. Among the most frequent are “correlative conjunctions,” which must frame matching parts. The four most common pairs are these:

Both . . . and

Either . . . or

Neither . . . nor

Not only . . . but also

For example, if a verb follows not only, then a verb must likewise follow but also. Here, though, the writer got it wrong:

Domestic violence is a force that not only causes suffering to the victim of an attack, but also detrimental effects on any children in the home.

The sentence needs matching parts for the not only. . . but also construction. Hence:

Domestic violence causes suffering not only to the victim of an attack but also to any children in the home.

Be sure that whenever you list items or use correlative conjunctions, you phrase the corresponding ideas so that they correspond grammatically. Doing so shows an orderly mind at work.

Basic

Revise the following sentences to cure the unparallel phrasing:

• The court relied heavily on the district court’s statement that the would-be intervenors retained the right to appear through counsel, to participate in the fairness hearing, to conduct discovery, and standing to appeal the court’s approval or disapproval of the class-action settlement.

• Tenant will probably not be able to have the lease declared void and unenforceable for vagueness because it contains all the essential elements of a lease: a description of the premises, the amount of rent to be paid, the term of the lease, and identifies the parties.

• The Younger doctrine also applies to a state civil proceeding that is (1) ongoing, (2) implicates important state interests, and (3) affords an adequate opportunity to raise federal claims.

Intermediate

Rewrite the following paragraph from a loan agreement so that you highlight the parallel phrases. The parenthetical letters—except for “(A)”—have been deleted. Simply reinsert the missing parenthetical letters “(B)” and “(C)” for the phrases that are parallel to the phrase introduced by “(A).” Study the passage first. Once you’ve decided where the letters should go, set off the listed items separately (see § 34). You might want to edit the sentence, of course. But be careful not to change the meaning.

2.1 No Default or Violation of the Law. The execution and delivery of this Loan Agreement, or the bond indenture, and any other transaction documents by the Authority, will not result in a breach of the terms of, or constitute a default under, (A) any indenture, mortgage, deed of trust, lease, or other instrument to which the Authority is a party or by which it or any of its property is bound or its bylaws or any of the constitutional or statutory rules or regulations applicable to the Authority or its property.

Advanced

Revise the following sentences to cure the unparallel phrasing:

• The essential elements of a fraud claim under New York law are that:

(a) the defendant made a misrepresentation

(b) of a material fact

(c) that was intended to induce reliance by the plaintiff

(d) which was in fact relied upon by the plaintiff

(e) to the plaintiff’s detriment.

• Where there are already allegations of defects in design, manufacturing, and warnings, a claim that the manufacturer should have recalled its 2009 products is redundant, prejudicial, and directed to the wrong institutional forum.

• Under Georgia law, the elements necessary for the application of equitable estoppel are (1) a false representation or concealment of facts, (2) it must be within the knowledge of the party making the one or concealing the other, (3) the person affected thereby must be ignorant of the truth, (4) the person seeking to influence the conduct of the other must act intentionally for that purpose, and (5) persons complaining must have been induced to act by reason of such conduct of the other.

Think of it this way: if you’re active, you do things; if you’re passive, things are done to you. It’s the same with subjects of sentences. In an active-voice construction, the subject does something (The court dismissed the appeal). In a passive-voice construction, something is done to the subject (The appeal was dismissed by the court).

The active voice typically has four advantages over the passive:

• It usually requires fewer words.

• It better reflects a chronologically ordered sequence (ACTIVE: actor → action → recipient of action), as opposed to the reverse (PASSIVE: recipient of action → action → actor).

• It makes the reading easier because its syntax meets the English speaker’s default expectation that the subject of a sentence will perform the action of the verb.

• It makes the writing more vigorous and lively (John wrote to the company as opposed to The company was written to by John).

Although these advantages generally hold true, they are not absolutes. You’ll occasionally find exceptions—situations in which you’ll want the passive (such as when the actor can’t be identified or is relatively unimportant). If you can reliably spot passive-voice constructions and quickly assess the merits of an active-voice alternative, you’ll be able to make sound judgments.

Reliably spotting the passive will prove a challenge. Fewer than half of lawyers can do it consistently. But it’s not so hard if you keep this fail-safe test in mind: if you see a be-verb (such as is, are, was, or were) followed by a past-tense verb, you have a passive-voice construction. Look for phrases like these:

is |

dismissed |

are |

docketed |

was |

vacated |

were |

reversed |

been |

filed |

being |

affirmed |

be |

sanctioned |

am |

rewarded |

And there is also the got passive, usually confined to informal contexts: The statute got repealed.

So all the following sentences are passive:

• In 2011, only ten executives were covered by Article 12.

• Prospective investors are urged to consult their own tax advisers.

• The 2012 Plan is intended to facilitate key employees in earning a greater degree of ownership interest in the Company.

You can improve these sentences by changing them to the active voice:

• In 2011, Article 12 covered only ten executives.

• We urge prospective investors to consult their own tax advisers.

• With our 2012 Plan, we intend to help key employees obtain a greater ownership interest in the Company.

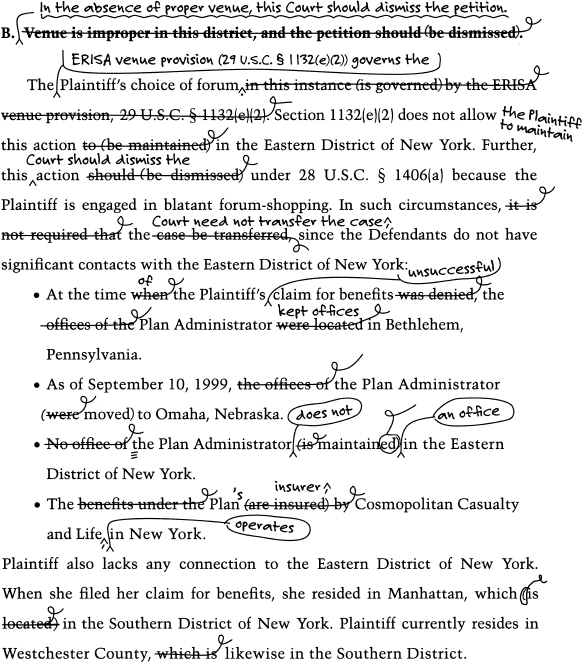

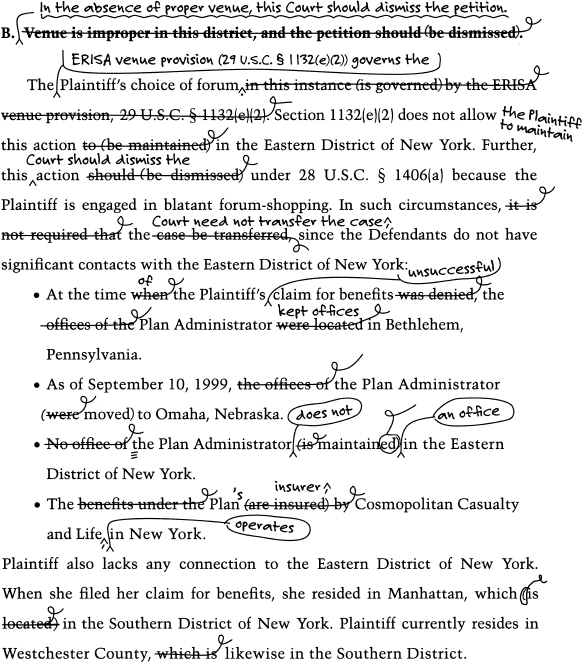

With a little effort, you’ll find yourself marking passages in this way:

Once you learn to edit that way, you’ll have mastered the passive voice. And in gaining this skill, you’ll find that there are many subtleties.

One subtlety is that in some passive-voice constructions the be-verb is understood in context. That is, although a grammarian would say it’s implied, you won’t be able to point to it in the sentence. For example:

Last week, I heard it argued by a client that national insurance should cover all legal fees.

Grammatically speaking, that sentence contains the implied verb being after the word it, so part of the sentence (not I heard but it argued) is in the passive voice. To make it active, you’d write this:

Last week, I heard a client argue that national insurance should cover all legal fees.

With the so-called “truncated passive,” the actor is omitted altogether—so that the sentence becomes vague and perhaps mysterious:

Last week, I heard it argued that national insurance should cover all legal fees.

The truncated is especially common among litigators who tell courts that their motions should be granted and that their opponents’ motions should be denied. Although it’s clear who is to do the granting or denying (the court), the lawyers who write this way miss an opportunity to flatter the very court they are trying to persuade. That is, by explicitly placing this Court as the subject of the sentence, they proclaim that only this Court has the power to do as they request.

In sum, the active voice generally saves words, says directly who does what, and makes for better, more interesting prose.

Exercises

Basic

Edit the following sentences to eliminate the passive voice:

• Testimony was heard from the plaintiff and from three witnesses on behalf of the defendant.

• This is a purely legal question to be determined by the court.

• McCormick’s motion for partial summary judgment on the duty to defend should be denied.

• Plaintiff’s opposition violates Rule 313 of the California Rules of Court and may be disregarded by the court.

Intermediate

Count the passive-voice constructions in the following paragraphs. Decide which ones you would change to active voice. Change them.

• The intention of the donor is established at the moment the funds are dedicated to a charitable cause. This dedication imposes a charitable trust for the donor’s objective as effectively as if the assets had been accepted subject to an express limitation providing that the donation was to be held in trust by a trustee solely for the purpose for which it was given. It is imperative that the objectives of individuals who give to charity be strictly adhered to.

• There are situations in which a motion for rehearing should be granted. Before the enactment of CPLR § 5517, it was held that when such a motion was granted, any appeals from the prior order would be dismissed. The CPLR was amended to “alter caselaw holding that an appeal from an order had to be dismissed upon entry in the court below of a subsequent order.” [Citation.] Thus today, § 5517(a) states that after a notice of appeal from an order has been served, the original appeal will not be affected if a motion for rehearing is entertained. The appeal will be neither mooted nor canceled by the grant or denial of a motion for rehearing.

• Jurisdiction was conferred on the district court by 28 U.S.C. § 1331. The complaint was dismissed with prejudice on March 31, 2009, and judgment was entered in favor of the Cauthorns. A timely notice of appeal was filed by Perkins on April 7, 2009. Jurisdiction is conferred on this court by 28 U.S.C. § 1291.

• During the taxable years at issue, the replacement fuel assemblies had not begun to be used by the company for their specifically assigned function, namely, to generate electrical power through nuclear fission. Nor were the assemblies placed in a state of readiness for their intended use during the years in which they were acquired. That did not occur until the spring of 2010, when, after more than a year of careful planning, the reactor was shut down, various maintenance tasks were performed, spent fuel assemblies were removed, the reactor was reconfigured using the new fuel assemblies in conjunction with partially spent assemblies that were not replaced, and low power testing was performed to ensure that the reconfigured reactor core performed safely in accordance with specifications. Only after those procedures had been successfully completed did the replacement fuel assemblies generate salable electric power and, hence, income to taxpayers. Only at that point could the replacement fuel assemblies be considered to have been placed in service.

Advanced

Find a published passage—two or three paragraphs—in which more than 50% of the verbs are in the passive voice. Retype it, providing the citation. Then, beneath the original, show your rewritten version.

or

In the literature on effective writing, find three authoritative discussions of situations in which the passive voice can be preferable to the active. Consolidate what those authorities say. In how many situations is the passive voice better?

When you can recast a negative statement as a positive one without changing the meaning, do it. You’ll save readers from needless mental work.

A single negative often isn’t very taxing:

No more than one officer may be in the polling place at a given time.

Still, the positive form is more concise and direct—and equally emphatic:

Only one officer may be in the polling place at a given time.

But when a sentence has more than one needless negative, the meaning can get muddled:

A member who has no fewer than 25 years of credited service but has not yet attained the age of 60 years and is not eligible for retirement may not voluntarily retire early without first filing a written application with the board.

Change no fewer than to at least; has not yet attained to is under; and may not. . . without to a different construction entirely, using must. Then make a few other edits, and the sentence becomes much more cogent:

Even if you’re a member who is not otherwise eligible for retirement, you may voluntarily retire if you are under the age of 60 and have at least 25 years of credited service. To do so, you must file a written application with the board.

This revisory technique won’t always work, of course. If you’re stating a prohibition, you’ll need to use a negative (“Don’t litter”). One airline avoids this type of directness in a lavatory sign: “Please discard anything other than tissue in the trash dispenser.” What this really means is “Please don’t discard anything except tissue in the toilet.” You wonder how many people bother to puzzle out the roundabout message of the original—which seems prompted by a desire to avoid using the word toilet. Still, avoiding the negative in that instance is awkward at best.

As Groucho Marx once said, “I can’t say that I don’t disagree with you.”

Exercises

Basic

Recast the following sentences in a more positive, straightforward way:

• Notice will not be effective unless it is delivered in person or by certified mail, return receipt requested.

• In the absence of any proof to the contrary, the court should presume that the administrator’s functions have not ceased.

• No termination will be approved unless the administrator reviews the application and finds that it is not lacking any requisite materials.

• It was not unreasonable to find that the jurors did likely believe Payton’s mitigation evidence beyond their reach. The jury was not left without any judicial direction.

Intermediate

Recast the following sentences in positive form:

• Notwithstanding the due-diligence requirement, the granting of a motion to vacate a judgment of conviction will not be precluded where there is nothing in the record to indicate that the defendant’s failure to acquire the evidence before or during trial was unreasonable.

• There is no issue of material fact that Renfro cannot establish that Aniseed, Inc. owed her a duty to prevent the injury she claims to have suffered.

• Bendola cannot be permitted to stand on nothing more than unsubstantiated and self-laudatory statements as a basis for denying summary judgment.

• No reason for refusing confirmation of the master’s report not covered by the exceptions in the rule is disclosed by the record or urged by the defendants.

• A plan shall not be treated as not satisfying the requirements of this section solely because the spouse of the participant is not entitled to receive a survivor annuity (whether or not an election has been made), unless both the participant and the spouse have been married throughout the one-year period ending on the date of the participant’s death.

Advanced

Find a sentence in published writing that is burdened with at least two negatives that you can easily recast in the positive with no change in meaning. If you’re a member of a writing group or class, provide each colleague with a copy of the original (with a citation) and your revised version.

Unskilled writers often compose sentences that, at the very end, fizzle. But skillful writers know that a sentence’s final word or phrase, whatever it may be, should have a special kick. So if you want to avoid sounding like a bureaucratic bore, perk up your endings. Consider:

• Melinda Jackson died three weeks later in Columbus, Ohio.

• Melinda Jackson died in Columbus, Ohio, three weeks later.

• Three weeks later, while visiting Columbus, Melinda Jackson died.

The first emphasizes the place of death—probably a poor strategy. The second emphasizes the time of death—again, probably ill-advised. The third emphasizes the death itself. That’s almost certainly what the writer intended.

With virtually any sentence, you have a choice about what you want to stress. Make it a conscious choice.

Again and again, you’ll find that the most emphatic position in a sentence isn’t the beginning but the end. Just as it’s unwise to end a sentence with a date (unless the date is all-important), it’s usually unwise to end one with a rule number or a citation:

Fenster International Racecourse, Inc. respectfully asks this Court to enter a summary judgment and, further, to find that there is no just reason to delay enforcement or appeal pursuant to Illinois Supreme Court Rule 304A.

A little reordering can make a big difference:

Fenster International Racecourse, Inc. respectfully asks this Court to enter a summary judgment. Under Illinois Supreme Court Rule 304A, there is no just reason to delay enforcement or appeal.

When you make this type of adjustment in sentence after sentence, you brighten the style.

Exercises

Basic

Rewrite the following passages to make the sentence endings more emphatic:

• This Court dismissed the whistleblower claims against the Governor on August 27 in response to the Governor’s Plea to the Jurisdiction.

• The right to stop the work is the single most important factor in determining whether a party is in charge of the work within the meaning of the Act.

• The Commission is not in a position to provide additional affidavits and other evidence to support its contention that Bulworth and Islington are an integrated enterprise at this time.

• The court may authorize a preappearance interview between the interpreter and the party or witness if it finds good cause.

• Silver Sidings contends that it had no control over the hazardous substance released to create the emergency, and that the Department of Natural Resources therefore has no jurisdiction over Silver Sidings under the Spill Bill (see § 260.510, RSMo 1994). In fact, Silver Sidings owned the property where the release occurred, owned the underground storage tanks from which the hazardous substance was released, permitted the hazardous substances to be stored in its tanks on its property, and had every right as a landowner to control how its land and tanks were used—all relevant factors under the Spill Bill. Thus, Silver Sidings is “a person having control over a hazardous substance involved in a hazardous-substance emergency” within the meaning of the Spill Bill.

Find a journalist’s article in which the last word is especially arresting. Be prepared to explain why.

or

In published legal writing, find a paragraph in which the sentence endings are unemphatic. Rewrite the paragraph to spruce it up.

Advanced

In the literature on effective writing, find support for the idea that sentences should end emphatically. If you belong to a writing group or class, prepare a page with at least three quotations to this effect. Provide full citations to your sources.