The field known as “legal drafting” includes all the various types of documents that set forth rights, duties, and liabilities in the future: contracts (everything from assignments to licensing agreements to warranties), wills, trusts, municipal ordinances, rules, regulations, and statutes. Lawyers commonly think of drafting as being more “technical” than other types of legal writing. Perhaps it is. It certainly differs from most other types of writing you might think of:

• People will read it adversarially, so it’s important to be unmistakable.

• It deals with future events.

• It’s typically a committee product—over time.

• It’s boring to read (and the writer doesn’t even care about being lively).

• It’s rarely read straight through, so it needs to be easy to consult.

Although some drafters’ habits migrate to other areas—where they typically don’t belong—the problems discussed in §§ 31–40 are predominantly those of transactional and legislative drafters.

Yet every lawyer occasionally gets involved in legal drafting of some sort—even if it’s only a short letter agreement—and every lawyer should practice these principles.

Today the prevailing attitude, unfortunately, is that lawyers should draft contracts, legal instruments, and statutes with the judicial reader in mind. Draft for the legal expert, the thinking goes, not for the ordinary reader.

But this approach is wrongheaded for at least five reasons. First, lawyers who draft for judges tend to adopt a highly legalistic style, since judges have legal training. Yet because these lawyers aren’t litigators, they almost never interact with judges. They don’t know how much most judges detest legalese. Second, judges never see most drafted documents—only a small fraction of 1% ever get litigated. Third, this approach contemplates only the disaster that might occur if litigation were to erupt. It does nothing to prevent the litigation from arising. In other words, the approach focuses exclusively on the back-end users, with no concern for the front-end users who must administer and abide by the document. Fourth, the further removed a document is from plain English, the more likely the parties are to ignore it in their everyday dealings. It won’t effectively govern their relationship. Fifth, the further removed a document is from plain English, the more divergent the views will be about its meaning—even among judges.

There is nothing newfangled about drafting for ordinary readers. It’s what the drafting experts have been saying for a long time, whether the document is a contract or a statute. This list is only a sampling:

• 1843: “[Most legal documents can be written] in the common popular structure of plain English.”1

• 1887: “[Good drafting] says in the plainest language, with the simplest, fewest, and fittest words, precisely what it means.”2

• 1902: “Latin words and, where possible without a sacrifice of accuracy, technical phraseology should be avoided; the word best adapted to express a thought in ordinary composition will generally be found to be the best that can be used. . . .”3

• 1938: “The simplest English is the best for legislation. Sentences should be short. Long words should be avoided. Do not use one word more than is necessary to make the meaning clear. The draftsman should bear in mind that his Act is supposed to be read and understood by the plain man.”4

• 1976: “[M]ore often than might be expected, [the lawyer’s] . . . duty to be complete and exact will require only short and ordinary words, and short, or at least simple, sentences. The language of lawyers need not, as Coode remarked of the statutes, be ‘intricate and barbarous.’ ”5

• 1988: “The most competent version of language and legal drafting . . . is that version which enables the message to be grasped readily, without difficulty and confusion. This is none other than plain language—language which gets its message across in a straightforward, unentangled way, that lets the message stand out clearly and does not enshroud or enmesh it in convolution or prolixity.”6

• 1996: “From the draftsman’s point of view, complexity intensifies the risk of error in the drafting and the risk of different interpretations in the reading: both chum for litigators. The commercial attorney, therefore, must work to achieve a result as simple as possible.”7

• 2012: “[T]he choice between precision and clarity is usually a false choice. If anything, plain language is more precise than traditional legal and official writing because it uncovers the ambiguities and gaps and errors that traditional style, with all its excesses, tends to hide. So not only is plain language the great clarifier, it improves the substance as well.”8

There’s a related point here. Drafters often lapse into the poor habit of addressing their provisions directly to someone other than the reader for whom the document is ostensibly written. Take, for example, this provision in a fee agreement, which, though purportedly directed to a prospective client, certainly wasn’t written with the client in mind:

Client understands that any estimates provided by the Firm of the magnitude of the expenses that will be required at certain stages of any litigation asserting a cause of action are not precise, and that the kinds and amounts of expenses required are ultimately a function of many conditions over which the Firm has little or no control, particularly the extent to which the opposition files pretrial motions and engages in its own discovery requests, whether in the nature of interrogatories, depositions, requests for production, or requests for admission, or any other type of discovery allowed by the rules of procedure in the forum in which the dispute is pending.

Who’s the real audience there? Perhaps the fee-dispute committee of the local bar, or perhaps the grievance committee. And for most clients, it’s a major turnoff. A leaner version informs the client more effectively because the point is clearer:

Our estimates are just that: estimates. Conditions outside our control, especially the other side’s pretrial motions and discovery requests, may raise or lower expenses.

Interestingly, lawyer groups—dozens of them—that have compared those two passages have said that if they were sitting on a grievance committee, they would be much less favorably disposed to the lawyer who wrote the first version.

Write for your immediate readers—the ones to whom you’re directing your communications. Don’t write for some remote decision maker who probably won’t ever see, let alone interpret, the document. If you write well for the front-end users, you’re less likely to have trouble down the line.

Exercises

Basic

Revise the following sentences so that they aren’t so obviously directed to the judicial interpreter:

• Nothing expressed or implied in this Agreement is intended or shall be construed to give to any person or entity, other than the parties and the Buyer’s permitted assignees, any rights or remedies under or by reason of this Agreement.

• The Corporation and the Executive explicitly agree that this Agreement has been negotiated by each at arm’s length and that legal counsel for both parties have had a full and fair opportunity to review the Agreement so that any court will fully enforce it as written.

• The employee explicitly acknowledges and agrees that the agreement not to compete, set forth above, is ancillary to an otherwise enforceable agreement and is supported by independent, valuable consideration as required by Texas Business and Commerce Code § 15.50. The employee further agrees that the limitations as to time, geographical area, and scope of activity to be restrained are reasonable and do not impose any greater restraint than is reasonably necessary to protect the goodwill and other business interests of the employer.

In a formbook, identify a legal document that no one apart from an expert would likely understand. If you’re part of a writing group or class, be prepared to discuss (1) the extent to which people other than experts might need to be able to understand the document and (2) at least three characteristics of the document that make it particularly difficult.

Advanced

Revise one or two provisions (about 200 words total) from the document you identified for the intermediate exercise. Produce before-and-after versions. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy to each colleague.

Experienced legal readers will expect you to lead with your most important points and to arrange other points in order of descending importance. This principle might seem so obvious as to be unnecessary. Yet some legal drafters habitually bury critical information.

Remember that plain English is concerned with readers—what they need to know and when they need to know it. You can’t be content to let readers fend for themselves. You’ll need to organize documents so logically and clearly that future reference to any specific point is easy. Although the nature of the particular document will influence the structure, the following guidelines generally enhance readability:

• Put the more important before the less important.

• Put the broadly applicable before the narrowly applicable.

• Put rules before exceptions.

If you’re drafting a contract, the first substantive provisions should be the parties’ main obligations to each other. And if you’re drafting a statute, put the main requirements up front—everything else flows from them.

Consider the following, a statute dealing with discriminatory housing practices. As you read it, try to figure out the drafter’s method of organizing the material:

Boston Fair Housing Commission—Title VIII—

Enforcement, Penalties

AN ACT empowering the Boston Fair Housing Commission to impose civil penalties and enforce by judicial power the provisions of Title VIII. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives in General Court assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:

SECTION 1. The following words used in this Act shall have the following meanings:

“Aggrieved person” means any person who claims to have been injured by a discriminatory housing practice or believes such person will be injured by a discriminatory housing practice that is about to occur.

“Commission” means the Boston Fair Housing Commission.

“Housing accommodations” means any building, structure or portion thereof which is used or occupied or is intended, arranged or designed to be used or occupied as the home, residence or sleeping place of one or more human beings and any vacant land which is offered for sale or lease for the construction or location thereon of any such building, structure or portion thereof.

“Person” includes one or more individuals, partnerships, associations, corporations, legal representatives, trustees, trustees in bankruptcy, receivers, and the commonwealth and all political subdivisions and boards or commissions thereof.

“Source of income” shall not include income derived from criminal activity.

SECTION 2. Subject to the provisions of section five, classes protected by this Act shall include race, color, religious creed, marital status, handicap, military status, children, national origin, sex, age, ancestry, sexual orientation and source of income.

SECTION 3. All housing accommodations in the city of Boston shall be subject to this Act, except as hereinafter provided. Nothing in this Act shall apply to housing accommodations which are specifically exempted from coverage by this Act, Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1988, as amended, 42 U.S.C. Sections 3601 et seq. or chapter one hundred and fifty-one B of the General Laws. Nothing in this Act shall apply to the leasing or rental to two or fewer roomers, boarders, or lodgers who rent a unit in a licensed lodging house.

SECTION 4. Nothing in this Act shall prohibit a religious organization, association or society, or any nonprofit institution or organization operated, supervised, or controlled by or in conjunction with a religious organization, association, or society, from limiting the sale, rental or occupancy of housing accommodations which it owns or operates for other than a commercial purpose to persons of the same religion, or from giving preference to such persons, unless membership in such religion is restricted on account of race, color, marital status, handicap, military status, children, national origin, sex, age, ancestry, sexual orientation or source of income.

SECTION 5. In the city of Boston, discriminatory housing practices are prohibited; provided, however, that no practice shall be prohibited hereunder unless such practice is also prohibited by the federal Fair Housing Act or chapter one hundred and fifty-one B of the General Laws.

SECTION 6. Any person who violates the provisions of this Act as to discriminatory housing practices shall, pursuant to the provisions of section seven, be subject to orders, temporary, equitable and legal, including compensatory damages, punitive damages or civil penalties and attorney’s fees and costs.

Lawyers who read that statute invariably say the same thing: § 5 should be moved to the fore. Once you make this change—as well as using headings and fixing various sentence-level problems—the statute is vastly improved:

Boston Fair Housing Commission—Title VIII—Enforcement, Penalties

This Act creates civil penalties for discriminatory housing practices.

The Legislature enacts the following:

1. Definitions.

1.1 “Housing accommodation” means any building, structure, or portion of a building or structure that is used or occupied or is intended, arranged, or designed to be used or occupied as the home, residence, or sleeping place of one or more human beings, including any vacant land that is offered for sale or lease for the construction or location of such a building or structure.

1.2 “Person” includes one or more individuals, partnerships, associations, corporations, legal representatives, trustees, trustees in bankruptcy, and receivers, as well as the commonwealth and all political subdivisions and boards or commissions of the commonwealth.

1.3 “Source of income” does not include income derived from criminal activity.

2. Discriminatory Practices Prohibited. In the city of Boston, discriminatory housing practices are prohibited to the greatest extent that they are prohibited by the federal Fair Housing Act or Chapter 151(B) of the General Laws. Classes protected by this Act include those based on race, color, religious creed, marital status, handicap, military status, parental status, national origin, sex, age, ancestry, sexual orientation, and source of income.

3. Scope of Prohibition; Exemptions. All housing accommodations in the city of Boston are subject to this Act. But nothing in the Act applies to housing accommodations that are specifically exempted from coverage by 42 USC §§ 3601 et seq. or Chapter 151(B) of the General Laws. Nothing in the Act applies to the leasing or rental to two or fewer roomers, boarders, or lodgers who rent a unit in a licensed lodging house.

4. Religious and Nonprofit Organizations. Nothing in this Act prohibits a religious organization or any nonprofit organization operated or supervised by a religious organization from limiting the sale, rental, or occupancy of housing accommodations that it owns or operates for other than a commercial purpose to persons of the same religion, or from giving preference to those persons, unless membership in the religion is restricted on account of race, color, marital status, handicap, military status, parental status, national origin, sex, age, ancestry, sexual orientation, or source of income.

5. Penalties. Any person who violates this Act is subject to court orders—temporary, equitable, and legal—including compensatory damages, punitive damages, and civil penalties, as well as attorney’s fees and costs.

So weigh the relative importance of the ideas you’re writing about—especially their importance to an intelligent reader. Then let your document reflect sensible judgment calls.

One last thing about organizing legal documents. Try to make whatever you write—and every part within it—self-contained. Your readers shouldn’t have to remember other documents or sections, or flip back to them, to make sense of what you’re saying.

Basic

Reorganize the following paragraph from a commitment letter for the purchase of unimproved land. (A commitment letter is a lender’s written offer to grant a mortgage loan.) Group the sentences according to whether they (1) specify the purpose of the letter, (2) state a buyer commitment, or (3) clarify the limitations of the letter. Then rewrite the passage in four paragraphs. Create a new introductory paragraph, and then create three paragraphs numbered 1, 2, and 3.

No sale or purchase agreement nor contract of sale is intended hereby until ABC Company (Buyer) and Lucky Development Company (Seller) negotiate and agree to the final terms and conditions of a Sale-and-Purchase Agreement. Buyer shall exercise its best efforts toward securing such commitments from high-quality department and specialty stores as are essential to establishment, construction, and operation of a regional mall. For the 111.3 acres of land in the Benbow House Survey, Abstract 247, the total consideration to be paid by Buyer to Seller, in cash, shall be equal to the product of Five and 50/100 Dollars ($5.50) multiplied by the total number of square feet within the boundaries of the land, in accordance with the terms and conditions that shall be contained in a subsequent Sale-and-Purchase Agreement mutually acceptable to and executed by Buyer and Seller within sixty (60) days from the date hereof. Buyer shall exercise its best efforts to enter into the Sale-and-Purchase Agreement within the stated time period. In the event Buyer and Seller cannot come to final agreement on the terms and conditions of a Sale-and-Purchase Agreement within sixty (60) days from the date hereof, this letter of commitment shall be null and void and neither party shall have any liabilities or obligations to the other.

Intermediate

Reorganize and rewrite the following paragraph from an oil-and-gas lease. If you feel the need, break the passage into subparagraphs and add subheadings.

9. The breach by Lessee of any obligations arising hereunder shall not work a forfeiture or termination of this Lease nor cause a termination or reversion of the estate created hereby nor be grounds for cancellation hereof in whole or in part unless Lessor shall notify Lessee in writing of the facts relied upon in claiming a breach hereof, and Lessee, if in default, shall have sixty (60) days after receipt of such notice in which to commence the compliance with the obligations imposed by virtue of this instrument, and if Lessee shall fail to do so then Lessor shall have grounds for action in a court of law or such remedy to which he may feel entitled. After the discovery of oil, gas or other hydrocarbons in paying quantities on the lands covered by this Lease, or pooled therewith, Lessee shall reasonably develop the acreage retained hereunder, but in discharging this obligation Lessee shall not be required to drill more than one well per eighty (80) acres of area retained hereunder and capable of producing oil in paying quantities, and one well per six hundred forty (640) acres of the area retained hereunder and capable of producing gas or other hydrocarbons in paying quantities, plus a tolerance of ten percent in the case of either an oil well or a gas well.

Advanced

In a statute book or contract formbook, find a document (no more than ten pages) with provisions that aren’t in a well-organized order of descending importance. Give it what professional editors call a “macro-edit”—that is, edit for organization without worrying much about sentence-level problems. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy of your cleanly edited version to each colleague. Be prepared to explain your edits.

You’ll find that most contracts begin with definitions. That’s all right if the document contains three or four of them. But if it has several pages of them, the definitions become a major obstacle. And believe it or not, you’ll sometimes encounter documents (such as municipal bonds) that begin with more than 30 pages of definitions.

Although you might think of definitions as clarifiers, they are often just the opposite—especially when bunched up at the outset of a corporate document. Take, for example, what is known as a “stock-purchase agreement.” The first section (which runs for ten pages) begins this way, in the middle of page one:

“Accounts Payable” means trade payables, plus Affiliate (as defined below) payables due in connection with Intercompany Agreements (as defined below) that will not be terminated prior to Closing (as defined below) pursuant to Section 6(h) below, less vendor credit receivables.

“Accounts Receivable” means trade receivables, plus Affiliate (as defined below) receivables due in connection with Intercompany Agreements (as defined below) that will not be terminated prior to Closing (as defined below) pursuant to Section 6(h) below, plus miscellaneous receivables less the reserve for doubtful accounts.

“Active Employees” means:

(i) AFPC Employees (including but not limited to Union Employees (as defined below)) as defined below;

(ii) Seller Guarantee Employees as defined below;

(iii) Shared Service Employees as defined below;

who remain in the employ of, or become employed by, AFPC on the date of Closing (as defined below), including but not limited to employees who are on the active payroll of AFPC, Seller Guarantor or Anaptyxis Corporation immediately prior to the Closing (as defined below) and who, although not performing direct services, are deemed to be Active Employees under AFPC’s, Seller Guarantor’s, or Anaptyxis Corporation’s standard personnel policies, such as employees on vacation.

“AFPC” has the meaning set forth in the recitals above.

“AFPC Employees” means employees of AFPC immediately prior to the Closing (as defined below).

“AFPC Facilities” means the plants, operations, and equipment owned or leased by AFPC and located in Jacksonville, Florida; Madison, Wisconsin; Virginia Beach, Virginia; Asheville, North Carolina; Sacramento, California; Canyon, Texas; Hot Springs, Arkansas; Morristown, New Jersey; Springfield, Illinois; and Yakima, Washington. The singular “AFPC Facility” means any one of the foregoing AFPC Facilities, without specifying which one.

“AFPC Pension Plan” means the General Employee Retirement Plan of Anaptyxis Foam Products Company and Participating Companies.

“AFPC Severance Plan” has the meaning set forth in Section 7(d)(v) below. “AFPC Shares” means all of the shares of the Common Stock, par value one hundred dollars and no/100 cents ($100.00) per share, of AFPC. The singular “AFPC Share” means any one of the AFPC Shares, without specifying which one.

“Affiliate” means, with respect to each of the Parties (as defined below), any legal entity that, directly or indirectly, (1) owns or otherwise controls, (2) is owned or otherwise controlled by, or (3) is under common control with, the aforesaid Party.

“Affiliated Group” means the affiliated group of corporations within the meaning of Section 1504(a) of the Code (as defined below) of which Anaptyxis Corporation is the common parent.

And we’re not even halfway through the A’s. The list finishes with the term Union Welfare Plans (sensibly enough never telling us that the singular Union Welfare Plan refers to any one of the specified plans, without specifying which one).

Corporate lawyers often become immune to this stuff after learning the material. They get used to having the definitions up front. But this approach violates § 32—about organizing from most to least important. In time, you might even conclude that these definitions are nothing but a ruse, by and large, for stripping the important information from relevant provisions and sticking it somewhere else, for the purpose of willful obscurity.

Of course, definitions aren’t always intended to obfuscate. Sometimes they’re placed in context—but again they’re often unnecessary. Maybe these definitions get in the way a little, and maybe nonlawyers will laugh at them, but they don’t usually cause ambiguity. They’re just a symptom of paranoia:

11. Indemnification. Each party hereto will indemnify and hold harmless (the “Indemnifying Party”) the other party (the “Indemnified Party”) from all loss and liability (including reasonable expenses and attorney’s fees) to which the Indemnified Party may be subject by reason of the breach by the Indemnifying Party of any of its duties under this Agreement, unless such loss or liability is also due to the Indemnified Party’s negligence or willful misconduct.

Delete the definitions, use the fairly ordinary legal word indemnitor, and you’ll shorten the passage by more than 25%:

11. Indemnification. Each party will indemnify the other party from all loss and liability (including reasonable expenses and attorney’s fees) to which the other party may be subject if the indemnitor breaches its duties under this Agreement, unless the loss or liability is also due to the indemnified party’s negligence or willful misconduct.

The revised version is clearer on a first read-through. And it’s every bit as clear on a second, third, or fourth.

If you work with securities disclosure documents, there’s some hope. The Securities and Exchange Commission has urged—if not mandated—that prospectuses and other securities documents minimize definitions.9 Most disclosure documents today put definitions, if there are any, at the end.

So what can you do if you’re not working in securities law? The first step is to put all the definitions in a schedule at the end of your document. Call it Schedule A. The second step—a much more ambitious one that you may have to postpone until you achieve some degree of seniority—is to rewrite the document to cut the definitions in half. That is, rewrite it so that it doesn’t need all those definitions. Simply say what you mean at the very place where you’re discussing something. In time, you’ll revise the document further. And one day you’ll find that you’re down to fewer than half a dozen definitions.

Then you can move them up front again, if you like. You won’t be creating a ghastly parade of terms at the outset. And if you have fewer than six, they’re likely to be only the most important terms. Getting to that point will involve much toil and trouble. But it will be worthwhile for virtually all your readers—whoever they may be.

As for cross-references, the question is whether they are genuinely intended to help the reader. If so, they are beneficial. But they can become instruments of sadistic torture. Let’s say you want to know whether you can e-file a pleading in a state trial court, but you’re not certain whether your case qualifies as a commercial action. Good luck discovering the answer:

“For purposes of this rule, ‘commercial action’ shall mean an action in which at least one claim of the types described in subparagraph (1) of paragraph (B) of subdivision (b) of section 6 of chapter 367 of the laws of 1999, as amended by chapter 416 of the laws of 2009 and chapter 528 of the laws of 2010, as amended, is asserted.”

Note that the drafter has referred to the legislature’s session laws, as opposed to the statute sections as codified, just to make finding the answer more onerous. A more readable version would incorporate the elements of the cross-referenced statute:

“For purposes of this rule, a ‘commercial action’ is one in which (1) neither party is a natural person, (2) the dispute concerns a business transaction, or (3) the lawsuit involves a claim of subrogation, contribution, or indemnity.”

This version gives you what you need without your needing to hunt elsewhere.

The world record for obscure cross-referencing must go to § 509(a) of the Internal Revenue Code, which states:

For purposes of paragraph (3), an organization described in paragraph (2) shall be deemed to include an organization described in section 501(c)(4), (5), or (6) which would be described in paragraph (2) if it were an organization in section 501(c)(3).10

To understand this provision, you must hold in mind the contents of six different sections nearly simultaneously. Some tax lawyers say that even after studying it at length, they’re not entirely sure what the provision means.

Exercises

Basic

In the literature on legal drafting, find additional authority for the idea that good drafters minimize definitions.

Intermediate

In a formbook or statute book, find a contract or statute in which definitions account for at least 40% of the length. If you’re part of a writing group or class, be prepared to discuss your views on (1) why the drafter resorted to so many definitions, (2) the extent to which you consider the definitions a help or a hindrance, and (3) whether any of the definitions are downright silly.

Advanced

In a formbook or ordinance book, find a short contract or ordinance in which definitions account for at least 20% of the length. Rewrite it without definitions. If you’re part of a writing group or class, be prepared to discuss any difficulties you had.

Statutes and contracts typically contain lists, often long ones. These lists are the main cause of overlong sentences. Break them up—set them apart—and when you’re calculating readability, the pieces won’t count as a single sentence.11

Although it’s sometimes useful to have a 1-2-3 enumeration within a paragraph of ordinary expository writing, in legal drafting it’s almost always better to set off the enumerated items. No one should have to trudge through this kind of marshy prose:

In the event that by reason of any change in applicable law or regulation or in the interpretation thereof by any governmental authority charged with the administration, application or interpretation thereof, or by reason of any requirement or directive (whether or not having the force of law) of any governmental authority, occurring after the date hereof: (i) the Bank should, with respect to the Agreement, be subject to any tax, levy, impost, charge, fee, duty, deduction, or withholding of any kind whatsoever (other than any change which affects solely the taxation of the total income of the Bank), or (ii) any change should occur in the taxation of the Bank with respect to the principal or interest payable under the Agreement (other than any change which affects solely the taxation of the total income of the Bank), or (iii) any reserve requirements should be imposed on the commitments to lend; and if any of the above-mentioned measures should result in an increase in the cost to the Bank of making or maintaining its Advances or commitments to lend hereunder or a reduction in the amount of principal or interest received or receivable by the Bank in respect thereof, then upon notification and demand being made by the Bank for such additional cost or reduction, the Borrower shall pay to the Bank, upon demand being made by the Bank, such additional cost or reduction in rate of return; provided, however, that the Borrower shall not be responsible for any such cost or reduction that may accrue to the Bank with respect to the period between the occurrence of the event which gave rise to such cost or reduction and the date on which notification is given by the Bank to the Borrower.

Drain the marshes, add some headings and subheadings (see § 4), and you have a presentable piece of writing, even though the material is fairly complex:

8.3 Payment of Reductions in Rates of Return

(A) Borrower’s Obligations. The Borrower must, on demand, pay the Bank additional costs or reductions in rates of return if the conditions of both (1) and (2) are met:

(1) the law or a governmental directive, either literally or as applied, changes in a way that:

(a) increases the Bank’s costs in making or maintaining its advances or lending commitments; or

(b) reduces the principal or interest receivable by the Bank; and

(2) any of the following occurs:

(a) the Bank becomes—with respect to the Agreement—subject to a tax, levy, impost, charge, fee, duty, deduction, or withholding of any kind whatever (other than a change that affects solely the tax on the Bank’s total income);

(b) a change occurs in the Bank’s taxes relating to the principal or interest payable under the Agreement (other than a change that affects solely the tax on the Bank’s total income); or

(c) a reserve requirement is imposed on the commitments to lend.

(B) Exceptions to Borrower’s Obligations. The Borrower is not responsible for a cost or reduction that accrues to the Bank during the period between the triggering event and the date when the Bank gives the Borrower notice.

A fix like that is mostly a matter of finding enumerated items, breaking them out into subparts, and then working to ensure that the passage remains readable.

You’ll need to use this technique almost every time you see parenthesized romanettes (i, ii, iii) or letters (a, b, c) in the middle of a contractual or legislative paragraph. Spotting the problem is relatively easy in a paragraph like this one:

5.4 Termination Fees Payable by Pantheon. The Merger Agreement obligates Pantheon to pay to OJM an Initial Termination Fee if (a) (i) OJM terminates the Merger Agreement because of either a Withdrawal by Pantheon or Pantheon’s failure to comply (and to cure such noncompliance within 30 days’ notice of the same) with certain Merger Agreement covenants relating to the holding of a stockholders’ meeting, the solicitation of proxies with respect to the Pantheon Proposal, and the filing of certain documents with the Secretary of State of the State of Delaware, (ii) Pantheon terminates the Merger Agreement prior to the approval of the Pantheon Proposal by the Pantheon stockholders, upon Pantheon having received an Acquisition Proposal and the Pantheon Board having concluded that its fiduciary obligations under applicable law require that such Acquisition Proposal be accepted, or (iii) either party terminates the Merger Agreement because of the failure of Pantheon to obtain stockholder approval for the Merger Agreement and the transactions contemplated thereby at a duly held stockholders’ meeting, and (b) at the time of such termination or prior to the meeting of the Pantheon stockholders there has been an Acquisition Proposal involving Pantheon or certain of its significant subsidiaries (whether or not such offer has been rejected or withdrawn prior to the time of such termination or of the meeting).

Breaking down the list into parallel provisions, with cascading indents from the left margin, clarifies the provision:

5.4 Termination Fees Payable by Pantheon. The Merger Agreement obligates Pantheon to pay to OJM an initial termination fee of $250 million if both of the following conditions are met:

(A) any of the following occurs:

(1) OJM terminates the merger agreement because Pantheon’s board withdraws its support of the merger or because Pantheon fails to comply (and fails to properly cure its noncompliance within 30 days of receiving notice) with its merger-agreement covenants relating to the holding of a stockholders’ meeting, the solicitation of proxies on the Pantheon proposal, and the filing of certain documents with the Delaware Secretary of State;

(2) Pantheon terminates the merger agreement before the Pantheon stockholders approve the Pantheon proposal, upon Pantheon’s having received a business-combination offer involving at least 15% of Pantheon’s stock and the Pantheon board’s having concluded that its fiduciary obligations under applicable law require acceptance of that proposal; or

(3) either party terminates the merger agreement on grounds that Pantheon has failed to obtain stockholder approval for the merger agreement and the related transactions at a duly held stockholders’ meeting; and

(B) at the time of the termination or before the meeting of the Pantheon stockholders, there has been a business-combination offer involving at least 15% of Pantheon’s stock or of its significant subsidiaries (whether or not the offer has been rejected or withdrawn before the termination or the meeting).

There’s another point here: you can’t have the main verb come after the list. The core parts of the English sentence are the subject and the verb (and sometimes an object). One key to writing plain English is ensuring that your readers reach the main verb early on. That way, the structure of the sentence becomes transparent.

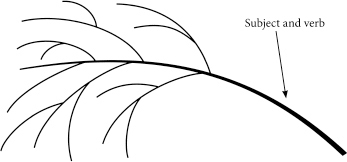

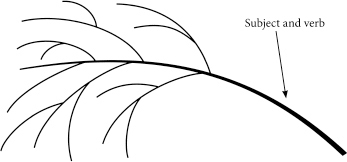

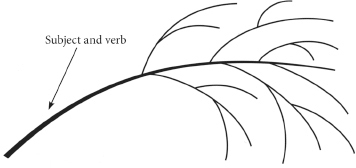

One of the worst habits that drafters develop is putting long lists of items in the subject so that the main verb is seriously delayed. This postponement of the action results in what linguists call “left-branching” sentences: ones with lots of complex information that branches out to the left side of the verb. The metaphor is that of a tree. As you read from left to right, and remembering that the tree’s trunk is the verb, imagine a sentence configured in this way:

That’s going to be fiendishly difficult to get through.

But imagine the tree reconfigured:

If all this talk of trees sounds too botanical, look at actual examples of sentences done both ways. Here’s a typical left-brancher:

Except as may otherwise be provided in these rules—

(a) every order required by its terms to be served;

(b) every pleading subsequent to the original complaint unless the court orders otherwise because of numerous defendants;

(c) every paper relating to discovery required to be served upon a party unless the court orders otherwise;

(d) every written motion other than one that may be heard ex parte; and

(e) every written notice, appearance, demand, offer of judgment, designation of record on appeal, and similar paper

—must be served on each of the parties to the action.

The language after the enumeration—sometimes called “unnumbered dangling flush text”—is uncitable. That can be a problem. Once you put the enumeration at the end, however, the problem is cured: every subpart is citable. Here’s the same sentence done as a right-brancher, with the enumeration at the end. Notice the newly added foreshadowing language (the following papers):

Except as these rules provide otherwise, the following papers must be served on every party:

(a) an order required by its terms to be served;

(b) a pleading filed after the original complaint, unless the court orders otherwise because of numerous defendants;

(c) a discovery paper required to be served on a party, unless the court orders otherwise;

(d) a written motion, other than one that may be heard ex parte; and

(e) a written notice, appearance, demand, offer of judgment, designation of record on appeal, or similar paper.

This is only a special application of the principle announced in § 7: keep the subject and verb together toward the beginning of the sentence.

Here’s the upshot: find the operative verb in the sentence and move it toward the front, putting your lists at the end of the sentence. Even with fairly modest lists, this technique can enhance readability.

Exercises

Basic

Revise the following paragraph to put the enumerated items in separate subparagraphs. At the same time, be sure that you don’t create unnumbered dangling flush text.

7.7 Insurance. Borrower shall provide or cause to be provided the policies of insurance described in Exhibit I, together with such other policies of insurance as Lender may reasonably require from time to time. All insurance policies (i) shall be continuously maintained at Borrower’s sole expense, (ii) shall be issued by insurers of recognized responsibility which are satisfactory to Lender, (iii) shall be in form, substance and amount satisfactory to Lender, (iv) with respect to liability insurance, shall name Lender as an additional insured, (v) shall provide that they cannot be canceled or modified without 60 days’ prior written notice to Lender, and (vi) with respect to insurance covering damage to the Mortgaged Property, (A) shall name Lender as a mortgagee, (B) shall contain a “lender’s loss payable” endorsement in form and substance satisfactory to Lender, and (C) shall contain an agreed value clause sufficient to eliminate any risk of coinsurance. Borrower shall deliver or cause to be delivered to Lender, from time to time at Lender’s request, originals or copies of such policies or certificates evidencing the same.

Intermediate

Revise the following passage to cure the left-branching problem:

If at any time the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission should disallow the inclusion in its jurisdictional cost of gas, cost of service, or rate base any portion of the cost incurred because of this gas purchase or the full amount of any costs incurred by Buyer for any field services or facilities with respect to any well subject hereto, whether arising from any term or provision in this Agreement or otherwise, including but not limited to price and price adjustments, the prices provided for herein, then Seller agrees that the price will be reduced to the maximum price for gas hereunder which the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission will allow Buyer to include in its jurisdictional cost of gas, cost of service, or rate base and Seller shall promptly refund with interest all prior payments for gas purchased hereunder which exceed the amount Buyer is permitted to include in said cost of gas, cost of service, or rate base.

Advanced

In a contract formbook, find a 200-plus-word paragraph that contains a series of romanettes (i, ii, iii). Rewrite the paragraph to set off the listed items, and make any other edits that improve the style without affecting the meaning. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy of the before-and-after versions to each colleague. Be prepared to discuss your edits.

Shall isn’t plain English. Chances are it’s not a part of your everyday vocabulary, except in lighthearted questions that begin, “Shall we . . . ?”

But legal drafters use shall incessantly. They learn it by osmosis in law school, and law practice fortifies the habit. Ask a drafter what shall means, and you’ll hear that it’s a mandatory word—opposed to the permissive may. Although this isn’t a lie, it’s a gross inaccuracy. And it’s not a lie only because the vast majority of drafters don’t know how shifty the word is.

Often, it’s true, shall is mandatory:

Each corporate officer in attendance shall sign the official register at the annual meeting.

Yet the word frequently bears other meanings—sometimes even masquerading as a synonym of may. Remember that shall is supposed to mean “has a duty to,” but it almost never does mean this when it’s preceded by a negative word such as nothing or neither:

• Nothing in this Agreement shall be construed to make the Owners partners or joint venturers.

• Neither the Purchaser nor any Employer shall discriminate against any employee or applicant for employment on the basis of race, religion, color, sex, national origin, ancestry, age, handicap or disability, sexual orientation, military-discharge status, marital status, or parental status.

• Neither party shall assign this Agreement, directly or indirectly, without the prior written consent of the other party.

Does that last example really mean that neither party has a duty to assign the agreement? No. It means that neither party is allowed to (that is, may) assign it.

In just about every jurisdiction, courts have held that shall can mean not just must12 and may13 but also will 14 and is.15 Even in the U.S. Supreme Court, the holdings on shall are major cause for concern. The Court has

• held that a legislative amendment from shall to may had no substantive effect;16

• held that if the government bears the duty, “the word ‘shall,’ when used in statutes, is to be construed as ‘may,’ unless a contrary intention is manifest”;17

• held that shall means “must” for existing rights, but that it need not be construed as mandatory when a new right is created;18

• treated shall as a “precatory suggestion”;19

• acknowledged that “[t]hough ‘shall’ generally means ‘must,’ legal writers sometimes use, or misuse, ‘shall’ to mean ‘should,’ ‘will,’ or even ‘may’ ”;20

• held that when a statute stated that the Secretary of Labor “shall” act within a certain time and the Secretary didn’t do so, the “mere use of the word ‘shall’ was not enough to remove the Secretary’s power to act.”21

These examples, which could be multiplied, show only a few of the travails that shall routinely invites. And the 92 pages of reported cases in Words and Phrases—a useful encyclopedia of litigated terms—show that the word shall is a mess.22 As Joseph Kimble, a noted drafting expert, puts it: “Drafters use it mindlessly. Courts read it any which way.”23

Increasingly, official drafting bodies are recognizing the problem. For example, most sets of federal rules—Civil, Criminal, Appellate, and Evidence—have recently been revamped to remove the shalls.24 (In stating requirements, the rules use the verb must.) The improved clarity is remarkable. Meanwhile, many transactional drafters have adopted the shall-less style, with the same effect. (In stating contractual promises, they typically use will.) You should do the same.

Basic

Edit the following sentences for clarity, replacing the shalls:

• Escrow Agent shall be entitled to receive an annual fee in accordance with standard charges for services to be rendered hereunder.

• Each member shall have the right to sell, give, or bequeath all or any part of his membership interest to any other member without restriction of any kind.

• The occurrence of any one or more of the following shall constitute an event of default: (a) Borrower shall fail to pay any installment of principal or interest on an advance . . .

• After completion of Licensee’s work, Licensee shall have the duty to restore the License Area to its former condition, as it was before the Licensee’s entry into the License Area.

• The sender shall have fully complied with the requirement to send notice when the sender obtains electronic confirmation.

Intermediate

In the following extract from a licensing agreement, count the various ways in which duties are stated. Edit the passage for consistency.

7.3 Ownership and Use of the Marks and Copyrights. Licensee shall not claim any title to or right to use the Marks except pursuant to this Agreement. Licensee covenants and agrees that it shall at no time adopt or use any word or corporate name or mark that is likely to cause confusion with the Marks.

7.4 Compliance with the Law. Licensee will use the Marks and copyright designation strictly in compliance with all applicable and related legal requirements and, in connection therewith, shall place such wording on each Licensed Item or its packaging as Licensee and Licensor shall mutually agree on. Licensee agrees that it will make all necessary filings with the appropriate governmental entities in all countries in which Licensee is selling the Licensed Item or using the Marks to protect the Marks or any of Licensor’s rights.

7.5 Duty of Cooperation. Licensee agrees to cooperate fully and in good faith with Licensor for the purpose of securing, preserving, and protecting Licensor’s rights in and to the Marks. Licensee must bear the cost if Licensee’s acts or negligence have in any way endangered or threatened to endanger such rights of Licensor.

Advanced

In a contract formbook, find a document in which shall appears inconsistently. On a photocopy, highlight every shall, as well as every other verb or verb phrase that seems to impose a requirement—such as must, will, is obligated to, agrees to, undertakes to, and has the responsibility to. If you’re part of a writing group or class, bring a highlighted copy to each colleague. Be prepared to discuss (1) how serious the inconsistencies are, (2) how they might have come about, and (3) how easy or difficult it would be to cure the problem in your document.

Legal-drafting authorities have long warned against using provided that.25 The phrase has three serious problems: (1) its meaning is often unclear, since it can create a condition, an exception, or an add-on; (2) its reach is often unclear, especially in a long sentence; and (3) it makes the sentence sprawl and creates more margin-to-margin text. You’re better off never using the phrase. You can always find a clearer wording.

Since provided that has as many as three meanings, the phrase has long been known to cause ambiguities.26 It has been said to be equivalent to if,27 except,28 and also.29

But that’s only the beginning of the problem. Another frequent source of litigation arises over what the phrase modifies. Does it go back ten words? Twenty? A hundred? That depends on how long the sentence is. Believe it or not, there’s a canon of construction about provisos, and the test is anything but clear: a proviso modifies only the immediately preceding language (whatever that is),30 but it may be held to reach back still further to effectuate the drafters’ manifest intention.31 This type of guidance is of little practical value.

Finally, there’s the problem of the blocklike appearance that provisos commonly create. You can double or even triple the length of a sentence with a couple of ill-placed provisos. Drafters frequently do this.

Let’s look at a passage that illustrates all three problems. The first two words in the passage mean if, but after that the sense of the provisos gets more confusing:

Provided that the Issuing Bank or Escrow Agent has received an Inspection Report, the Purchase Price will be released upon the earliest occurrence of one of the following: (i) receipt by the Escrow Agent or the Issuing Bank of a letter from the Buyer, the Buyer’s freight forwarder, if any, or the Buyer’s shipper certifying that the Glenn Mill is loaded on one or more cargo vessels and in transit to Brazil; or (ii) the expiration of a period of one hundred twenty (120) calendar days following the Delivery Date; provided, however, that any events or circumstances beyond Buyer’s reasonable control which prevent the disassembly, packing or shipment of the Used Steel Mill and/or Incomplete Mill, including both events of force majeure and causes imputable to Seller, shall extend the aforementioned period for the same number of days that such event or circumstance persists, and provided, further, that if such a period should be extended by such events or circumstances more than one hundred eighty (180) calendar days beyond the Delivery Date, either party may rescind this Agreement by written notice to the other, with a copy to the Escrow Agent or the Issuing Bank in accordance with section 11, hereof, whereupon the portion of the Purchase Price being held in the Escrow Account will be released to the Buyer or the letter of credit will be canceled, as the case may be, and title to and possession of the Glenn Mill will revert to Seller without the need for further action.

In fact, the middle proviso creates an exception, and the third (as you might have recognized) creates what lawyers call a “condition subsequent” to the exception. But then there’s the question of what the second proviso modifies: does it go back to the beginning of the sentence, or only to (i) and (ii), or only to (ii)? If you took the time to puzzle it out, you’d finally conclude that it modifies only (ii), which is the only preceding language that mentions a period of time. Finally, did you notice how unappealing the long paragraph is?

If you eliminate the provisos and use subparagraphs (see § 34), the ambiguities are removed. Equally important, the passage becomes much more readable:

If the Issuing Bank or Escrow Agent receives an Inspection Report, the Purchase Price must be released upon the earlier of

(A) the date when the Escrow Agent or the Issuing Bank receives a letter, from either Buyer or Buyer’s freight forwarder or shipper, certifying that the Glenn Mill is loaded on one or more cargo vessels and is in transit to Brazil; or

(B) 120 days past the Delivery Date, with the following qualifications:

(1) this 120-day period will be extended for as long as any event or circumstance beyond Buyer’s reasonable control—including force majeure and causes imputable to Seller—prevents disassembling, packing, or shipping the Used Steel Mill or Incomplete Mill;

(2) if, under (1), the period is extended for more than 180 days beyond the Delivery Date, either party may rescind this Agreement by giving written notice to the other and by forwarding a copy to the Escrow Agent or the Issuing Bank, in accordance with section 11; and

(3) if either party rescinds under (2), the portion of the Purchase Price held in the Escrow Account will be released to Buyer or the letter of credit canceled; title to and possession of the Glenn Mill will then automatically revert to Seller.

According to the system for computing average sentence length (again, see the beginning of § 34), the average in that particular passage is now down to 33 words—as opposed to the 250-word sentence in the original.

You’ll see the same phenomenon again and again: you can always improve on a proviso. Here are three more examples:

• Neither party may assign this Agreement without the prior written consent of the other party; provided, however, that Publisher may assign its rights and obligations under this Agreement without the prior written consent of Author to any person or entity that acquires all or substantially all of the business or assets of Publisher.

• If Pantheon’s annual requirements for aluminum closure sheet fall below the 9-million pound minimum, Pantheon will purchase and Alu-Steel will supply all of Pantheon’s volume requirements; provided, however, that Pantheon may have reasonable trial quantities supplied by an alternate source.

• If in the absence of a protective order Bryson is nonetheless compelled by court order to disclose protected information, Bryson may disclose it without liability hereunder; provided, however, that Bryson gives Pantheon written notice of the information to be disclosed as far in advance of its disclosure as practicable and that Bryson use its best efforts to obtain assurances that the protected information will be accorded confidential treatment; and provided further, that Bryson will furnish only that portion of the protected information that is legally required.

The first two examples are easily remedied by relying on But as a sentence starter—a perfectly acceptable and even desirable method of beginning a sentence (see § 6):

• Neither party may assign this Agreement without the prior written consent of the other party. But without the Author’s prior written consent, Publisher may assign its rights and obligations under this Agreement to any person or entity that acquires all or substantially all of Publisher’s business or assets.

• If Pantheon’s annual requirements for aluminum closure sheet fall below the 9-million-pound minimum, Pantheon will purchase and Alu-Steel will supply all of Pantheon’s volume requirements. But Pantheon may have reasonable trial quantities supplied by an alternate source.

A grammatically acceptable but less appealing method would be to start those revised sentences with However.32

The third example requires only slightly more ingenuity to improve the wording:

• If a court orders Bryson to disclose protected information without entering a protective order, Bryson may disclose it without liability if

(A) Bryson gives Pantheon written notice of the information to be disclosed as far in advance of its disclosure as practicable;

(B) Bryson uses best efforts to obtain assurances that the protected information will be accorded confidential treatment; and

(C) Bryson furnishes only the portion of the protected information that is legally required.

Notice how the revision makes it clear that there are three requirements with which Bryson must comply. That wasn’t as clear in the original.

By the way, relatively few transactional lawyers have ever heard the chorus of warnings about provisos. Long-standing members of the bar, having practiced for 25 years or more, often use provisos throughout their work. You might well ask how this is possible if the principle about avoiding them is so well established. The answer is that despite recent improvements, legal drafting has long been neglected in American law schools. And the literature on legal drafting is little known. You’ll find that most transactional lawyers can’t name even one book on the subject. So it’s hardly surprising that even the most basic principles of good drafting are routinely flouted. Only recently have law schools begun to correct this problem by offering more drafting courses.

Basic

Revise the following passages to eliminate the provisos:

• The quantity of product whose delivery or acceptance is excused by force majeure will be deducted without liability from the quantity otherwise subject to delivery or acceptance; provided, however, that in no event will Buyer be relieved of the obligation to pay in full for product previously delivered.

• Contractor will be reimbursed for travel and subsistence expenses actually and necessarily incurred by Contractor in performing this Contract in an amount not to exceed $2,000; provided that Contractor will be reimbursed for these expenses in the same manner and in no greater amount than is provided in the current Commissioner’s Plan.

• The Borrower may, at any time and from time to time, prepay the Loans in whole or in part, without premium or penalty, upon at least one business day’s notice to the Lender, specifying the date and the amount of the prepayment; provided, however, that each such prepayment must be accompanied by the payment of all accrued but unpaid interest on the amount prepaid to the date of the prepayment.

Intermediate

Revise the following passages to eliminate the provisos:

• If Seller’s production of the product is stopped or disrupted by an event of force majeure, Seller must allocate its available supplies of the product to Buyer based upon the same percentage of Seller’s preceding year’s shipments of products to Buyer in relation to Seller’s total shipments for the product, provided, however, that to the extent that Seller does not need any tonnage that is available in excess of the allocation of products to Buyer, it must make that tonnage available to Buyer.

• This Agreement will terminate upon the termination of the Merger Agreement under § 6.1 or two years from the effective date of this Agreement, whichever occurs earlier; provided that if the Merger Agreement is terminated under § 6.1(d), 6.1(g), or 6.1(h) of that agreement and at the time of termination there has been an acquisition proposal as described in § 14 of that agreement, then this Agreement will not terminate until four months after the termination of the Merger Agreement or payment to the parent company of a termination fee under § 6.2, whichever occurs earlier.

• When the Lease term expires, if Renton has fully complied with all its obligations under the Lease, Renton will be entitled to a 20% interest in the profits of Jamie Ridge in the form of a nonmanaging membership interest, and the right to lease or buy for nominal consideration approximately 1.6 acres, in an area designated by Jamie Ridge, for the purpose of operating a garden nursery, provided that any such lease or sale would be contingent upon the nursery’s purpose being permitted under all applicable laws, and provided further that the area designated for the nursery would be burdened by a restrictive covenant prohibiting any other use thereof.

In a federal statute or regulation, find a passage containing at least two provisos. Rewrite the passage to eliminate the provisos and otherwise improve the style. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy of the before-and-after versions to each colleague.

With experience you’ll find that you don’t need and/or. But more than that, you’ll find that and/or can be positively dangerous.

About half the time, and/or really means or; about half the time, it means and. All you need to do is examine the sentence closely and decide what you really mean. If a sign says, “No food or drink allowed,” it certainly doesn’t suggest that you may have both. And if a sign says, “Lawyers and law students are not allowed beyond this point,” even though the message is bizarre it doesn’t suggest that a lawyer may proceed alone.

But let’s look at real sentences from transactional documents. In the following examples, and/or means or:

• Licensee provides no warranty as to the nature, accuracy, and/or [read or] continued access to the Internet images provided under this Agreement.

• The Foundation will promptly furnish Sponsor with a disclosure of all intellectual property conceived and/or [read or] reduced to practice during the project period.

• Each party will inform the other if it becomes aware of the infringement by a third party under any claim of a patent that issues on joint inventions and/or [read or] sole inventions. If litigation occurs under any joint invention and/or [read or] sole invention, and both parties are necessary parties to the litigation, then each party will pay its own costs.

Here, though, it means and:

• All applicable state and federal taxes will apply to cash awards received and/or [read and] options exercised by Zerton.

• Licensee agrees to indemnify Owner for any claims for brokerage commissions and/or [read and] finder’s fees made by any real-estate broker for a commission, finder’s fee, or other compensation as a result of the License.

• The deliverables are the Sponsor’s property, and the Sponsor may use and/or [read and] duplicate them in its normal business operations.

The danger lurking behind and/or is that the adversarial reader can often give it a skewed reading. Consider the employment application that asks, “Are you able to work overtime and/or variable shifts?” If the applicant can work overtime but not variable shifts, the answer would be yes. The next question reads, “If the previous answer was ‘No,’ please explain.” The applicant need not fill this out, since the previous answer was yes. She gets hired, goes to work, and is soon asked to work variable shifts. She says no and gets fired. A wrongful-termination lawsuit soon follows. Is that a far-fetched case? No. It’s one of many actual lawsuits spawned by the use of and/or.

Courts, by the way, have routinely had extremely unkind words for those who use and/or.33 Don’t give them cause for more grumbling.

Exercises

Basic

Edit the following sentences to remove and/or:

• AmCorp and Havasu have the sole right to use inventions covered by this Agreement and to obtain patent, copyright, and/or trade-secret protection or any other form of legal protection for the inventions.

• Immediately upon notice from Licensor, Licensee must discontinue the printing and/or manufacture of licensed items at every print shop and/or the making of those items.

• No change, waiver, and/or discharge of this Agreement is valid unless in a writing that is signed by an authorized representative of the party against whom the change, waiver, and/or discharge is sought to be enforced.

• The settlement is binding on all the creditors and/or classes of creditors and/or on all the stockholders or classes of stockholders of this Corporation.

Intermediate

Find three cases in which courts have criticized the use of and/or. Quote and cite the relevant passages.

Advanced

In state statutes or regulations, find three sentences in which and/or appears. Retype them, providing citations, and then edit them to remove and/or without changing the original drafter’s meaning. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy of the before-and-after versions to each colleague. Be prepared to discuss your edits.

You’ll find an age-old provision in statutes and contracts: “The singular includes the plural; the plural includes the singular.” Only the second part of this formulation has ever really mattered. For example, if an ordinance says, “People may not set off fireworks within the city limits,” the plural words people and fireworks create several problems. First, does the ordinance apply only to people who work in groups, but not to individuals? Second, even if it does apply to individuals, doesn’t the phrasing imply that everyone gets a freebie? That is, only fireworks are forbidden, but if you shoot off just one . . . (Some would make it a big one.) Third, what constitutes a violation? If you set off 30 fireworks in 30 minutes, how many times have you violated the ordinance? Once or 30 times?

But if the ordinance says, “No person may set off a firework,” it avoids all those problems. That’s the beauty of the singular.

It’s true that you’ll occasionally need the plural. For example:

• Any dispute among employers may be resolved by the employers’ grievance committee.

• The Company agrees to destroy all unauthorized reproductions in its possession.

• These rules are intended to streamline discovery.

If you’re going to use a plural, however, double-check it: make sure that it really is necessary.

Exercises

Basic

Edit the following sentences to change the plural to singular when appropriate:

• Employees who have earned more than 25 credits are eligible for positions under § 7.

• The fire marshal is responsible for issuing all the permits listed in this section.

• All the shareholders of the corporation have only one vote.

• If the appealing parties have not satisfied the requisites for interlocutory appeals, their appeals will be dismissed.

• When issues not raised by the pleadings are tried by the express or implied consent of the parties, the issues must be treated in all respects as if they had been raised by the pleadings.

In a state-court rulebook, find a rule that is undesirably worded in the plural. Photocopy the rule and edit it to fix the problem you’ve identified. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy of your edited version to each colleague.

Advanced

In the literature on legal drafting, find additional authority for the idea that a singular construction typically works better than a plural one.

To maximize readability, spell out the numbers one to ten only. For 11 and above, use numerals. They’re more economical. Compare just how many characters you save by writing 73 as opposed to seventy-three. For the busy reader, even milliseconds add up.

But this numerals-vs.-words rule has four exceptions:

1. If a passage contains some numbers below 11 and some above—and the things being counted all belong to the same category or type—use numerals consistently: Although we ordered 25 computer terminals, we received only 2. (But We received our 25 terminals over a three-month period.)

2. For dollar amounts in millions and billions, use a combination of numerals plus words for round numbers ($3 million) and numerals for other numbers ($3,548,777.88).

3. For a percentage, use numerals with a percent sign: 9%, 75%.

4. Spell out a number that begins a sentence: Two hundred fifty-three cases were disposed of in this court last year. (You also might just recast a sentence like that one.)

An additional point: unless you’re preparing mathematical figures in a column, omit “.00” after a round number.

As for word-numeral doublets—“one hundred thousand and no/100 dollars ($100,000)”—few lawyers know the origin of this ancient habit. Having put the question to more than fifty (50) lawyerly audiences, I’ve mostly heard wrong answers:

• Word-numeral doublets are a safeguard against typos.

• They increase readability.

• In checks, they help in cases of illegible handwriting.

• The illiterate can at least read the numbers.

• They prevent discrepancies in numbers.

The last is the most ludicrous: discrepancies aren’t possible unless you write it twice.

In truth, word-numeral doublets arose centuries ago as a safeguard against fraudulently altered documents. That’s why you write out checks in both words and numerals—the numerals by themselves would be too easy for a cheat to alter. And the practice proliferated in the days of carbon copies. When you had five or six carbons, the typewriter’s impressions for digits often weren’t legible on the last couple of copies. Hence the doubling helped ensure that all the carbons were legible.

But these rationales don’t extend very far. There’s no good reason why modern briefs, judicial opinions, statutes, or contracts should contain doublets—yet many of them do. The result is unappealing:

Often you’ll find passages in which the important numbers are written out once, while the trivial ones get doubled:

If the sale transaction closes on or before December 31, 2010, (i) the purchase price will be reduced by $100,000; and (ii) on the second anniversary of the closing date, the City will receive the vehicles and equipment listed in Exhibit G. During the two (2) year period after the closing date, Pitmans will make its vehicles and equipment available to the City for routine emergency maintenance at the rate of fifty and no/100 dollars ($50.00) per hour.

Are the two-year period and the $50 rate really more susceptible to fraudulent alteration than the sum of $100,000?

The extremes to which this silly habit is taken are illustrated by a letter I recently received from a fellow lawyer. This acquaintance has an underdeveloped sense of humor, so I knew the letter was no joke. It began: “Dear Bryan: It was a real pleasure running into you and your two (2) daughters last week at the supermarket.” Did he really suspect that I might alter the letter?

Quite apart from the recommendation in this section, be exceedingly careful about numbers in drafted documents. Your eye, of course, will be immediately drawn to the numerals. So the recommendation will help you. But whatever convention you follow, you’ll find that it’s important to double-check—even though you shouldn’t double up—your numbers.

Exercises

Basic

Fix the numbering problems in the following passage:

Before the entry of the final decree on June 5, 2010, the parties participated in four (4) hearings before three (3) Commissioners in Chancery, took three (3) additional sets of depositions of healthcare providers, and had at least twelve (12) ore tenus hearings. The court granted a divorce on the ground of separation in excess of one year, granted spousal support and Five Thousand Dollars ($5,000.00) in costs and attorney’s fees to the wife, and equitably distributed the property.

In the literature on legal drafting, find two authoritative discussions on any aspect of word-numeral doublets, such as the idea that words control over numerals (and why). If you’re part of a writing group or class, bring the authorities with you and be prepared to report on them.

Advanced

Find two cases in which courts have had to interpret documents that contain discrepancies in doubled-up words and numerals. Brief the cases and, if you’re part of a writing group or class, be prepared to discuss them.

There’s a recurring story in law offices. It goes something like this.

Two corporations are planning a joint venture. Each one, of course, is represented by a law firm. One firm—the one representing the larger corporation—prepares the first draft of the contract. Naturally, the lawyers rely on one of their forms. They just tweak it.

Henry, a third-year associate at Firm A, sends the draft contract over to Lindsay, a partner at Firm B. Being an experienced lawyer, Lindsay carefully works through the draft, noting possible additions, amendments, and negotiating points. After a few hours of reading, she comes across § 7.1, on page 31. It seems to be a remnant of some other deal—something not at all germane to the joint venture. She can’t understand what it’s saying. She talks to a couple of colleagues, who agree. So she calls Henry.

“Henry, this is Lindsay.”

“Hi.”

“I’ve been working through your draft contract, and I expect to have my comments to you by next Tuesday. I don’t see any serious impediments.”

“Glad to hear it,” says Henry.

“Oh, but there’s one thing I want to ask you about now. Do you have a copy of the contract handy?”

“Let me just get it.” (Pause.) “OK.”

“Look at page 31. Section 7.1. What does that mean?”

(Long pause.)

“Now that you mention it, I’m not quite sure. I didn’t draft that part of the agreement. I’m working on this deal with Barbara, a partner here at the firm. Let me talk with her about it. I’ll get back to you.”

Henry has just admitted to Lindsay that he didn’t know the meaning of a provision in a document that he sent to her. It’s a little embarrassing—but only a little. Now he has the difficult problem of raising the issue with Barbara. He’ll have to finesse the discussion. Here goes:

“Say, Barbara,” he says, “Lindsay just called about our draft contract. She’ll have her comments to us by next Tuesday.”

“Good,” says Barbara. “Thanks for telling me.”

“Well, that’s not all. She wants to know something about § 7.1, right here on page 31. See?”

“What does she want to know?”

“Well, she’s asking what it means.”

“Did you tell her?”

“No. Since I didn’t draft that, I thought I should get your view of it.”

“I see. What do you think it means?”

“To be honest, I can’t tell. I’ve looked at it and can’t figure it out.”

As you can imagine, this hasn’t been pleasant for Henry. He has had to admit both to Lindsay and to Barbara that he sent a contract out without knowing what one of its provisions means. Barbara, being a partner, knows what it means. And she says so in fairly clear language: “Henry, essentially § 7.1 does thus-and-so.” A light goes on in Henry’s brain. Now he sees it.

Back at his office, he calls Lindsay:

“This is Henry again. I’ve talked with Barbara about § 7.1, and essentially that provision does thus-and-so.”

“Oh. That’s what it’s doing there. Let’s just say it that way, then. ‘Thus-and-so’ is clear, but not this language you have at § 7.1. I don’t have any problem with what you’re trying to accomplish, but we need to say it so that my client and I can understand it.”

“You mean change the language?”

“Of course. I can’t understand § 7.1.”

“Well, I’ll have to talk with Barbara about this.”

And he does. In the end, Lindsay always wins this kind of discussion. But rather than use the newly clarified language, Firm A sticks to its bad old form—the one that even its third-year associates can’t understand. That’s the way of the world.

This scenario might seem far-fetched. In fact, though, some version of it plays out every day in dozens of law offices throughout the country.

What might be even more surprising is that official documents frequently contain provisions that are so obscure that no one knows how, when, or why they got inserted. In the mid-1990s, when a state supreme court revised its appellate rules for clarity, there were several sentences that befuddled everyone. Even procedural scholars wouldn’t venture to guess why those sentences were there, or even what they meant. So did the court keep the sentences? Absolutely not. The revisers cut them, and rightly so.

If you don’t understand a provision, it’s probably one that will come back to harm you in some way—especially in a contract. So rather than leave something in, idly supposing there’s a reason for it when no knowledgeable lawyer can say what that reason is, you’re better off deleting it. But remember the part about diligence: you must sometimes sweat and fret awhile to discover a meaning before you can safely conclude that there isn’t any.

Exercises

Basic

Decide whether you think the provisions described below have any real meaning. If you’re part of a writing group or class, be prepared to defend your position.

• No savings and loan holding company, directly or indirectly, or through one or more transactions, shall . . . acquire control of an uninsured institution or retain, for more than one year after other than an insured institution or holding company thereof, the date any insured institution subsidiary becomes uninsured, control of such institution. [12 CFR § 584.4(b).]

• “Spouse” is defined as the person to whom the Cardholder is legally married or the person with whom the Cardholder is cohabiting as husband and wife and has been cohabiting for at least two years provided that where there is a legally undissolved marriage and the Cardholder is cohabiting with a person as husband and wife and has been so cohabiting for at least two years, the spouse is the person with whom the Cardholder has been cohabiting.

• The 911 provider shall not impose, or fail to impose, on Company any requirement, service, feature, standard, or rate that is not required of the incumbent local exchange company.

Intermediate

Interview a lawyer who (1) has practiced transactional law for at least ten years and (2) can recall a situation in which a provision relating to some other deal had meaninglessly crept into draft contracts where the provision didn’t belong. Take specific notes on the interview. If you’re part of a writing group or class, be prepared to report your findings.

Advanced

Find a reported case in which a party has had to argue that a sentence or paragraph is essentially meaningless. Write a case brief. Decide whether you agree with the court’s resolution of the issue. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy of both the case and your case brief to each colleague.