What’s your biggest challenge as a writer? It’s figuring out, from the mass of possibilities, exactly what your points are—and then stating them coherently, with adequate reasoning and support.

Although this advice might seem obvious, legal writers constantly ignore it. The result is a mushy, aimless style. Even with your point well in mind, if you take too long to reach it, you might as well have no point at all. Only readers with a high incentive to understand you will labor to grasp your meaning.

That’s where law school comes in. Every law student must read and digest scads of diffuse writing. You read through old cases that take forever to convey fairly straightforward points. You read law-review articles that take 50 pages to say what might be said more powerfully in 5. And as you read, your incentive for gleaning the main message remains high because your future in law depends on it. You have no choice but to wade through all that opaque prose.

Take, for example, a sentence from a judicial opinion. See if you can follow the court’s point:

And in the outset we may as well be frank enough to confess, and, indeed, in view of the seriousness of the consequences which upon fuller reflection we find would inevitably result to municipalities in the matter of street improvements from the conclusion reached and announced in the former opinion, we are pleased to declare that the arguments upon rehearing have convinced us that the decision upon the ultimate question involved here formerly rendered by this court, even if not faulty in its reasoning from the premises announced or wholly erroneous in conclusions as to some of the questions incidentally arising and necessarily legitimate subjects of discussion in the decision of the main proposition, is, at any rate, one which may, under the peculiar circumstances of this case, the more justly and at the same time, upon reasons of equal cogency, be superseded by a conclusion whose effect cannot be to disturb the integrity of the long and well-established system for the improvement of streets in the incorporated cities and towns of California not governed by freeholders’ charters.1

What’s the court saying? In a highly embellished style, it’s simply saying, “We made a mistake last time.” That’s all.

If you add sentence after sentence in this style—all filled with syntactic curlicues—you end up with an even more impenetrable morass of words. The only readers who will bother to penetrate it are either law students or lawyers who are paid to do so.

However willing you might be to pierce through another writer’s obscurity, you must insist that your own writing never put your readers to that trouble. On the one hand, then, you’ll need a penetrating mind as a reader to cut through overgrown verbal foliage. On the other hand, you’ll need a focused mind as a writer to leave aside everything that doesn’t help you swiftly communicate your ideas.

That’s the start to becoming an effective legal writer.

Exercises

Begin each of the following exercises by looking up the case cited. Then write a case brief for each one—that is, a short case synopsis that follows a standard form: (1) case name and citation (in proper form); (2) brief facts; (3) question for decision; (4) holding; and (5) reasoning. Your finished product should fit on a five-by-seven-inch index card (front and back). The exercises are increasingly challenging for either or both of two reasons: first, the increasing complexity of the legal principles involved; and second, the increasing difficulty of the language used in the opinions. When you’re finished, have a friend assess how easy it is to understand what you’ve written. Here’s an example of a case brief:

Case: Henderson v. Ford Motor Co., 519 S.W.2d 87 (Tex. 1974).

Facts: While driving in city traffic, Henderson found that, despite repeated attempts, she couldn’t brake. To avoid injuring anyone, she ran into a pole. An investigator later found that part of a rubber gasket from the air filter had gotten into the carburetor. Henderson sued Ford on various theories, including defective design. Her expert witness didn’t criticize the design of the gasket, carburetor, or air filter, but did say that the positioning of the parts might have been better. No one testified that the air-filter housing was unreasonably dangerous from the time of installation. Yet the jury determined that the air-filter housing was defective and that this defect had caused Henderson’s damage.

Question: The expert witness didn’t testify that the design was unreasonably dangerous—only that it could be improved on. Is this testimony sufficient to support a jury finding that a product’s design is unreasonably dangerous?

Holding: Mere evidence that a design could be made better—without evidence that the design itself was unreasonably dangerous—is insufficient to impose liability on a manufacturer.

Reasoning: A plaintiff in a design-defect case must provide some evidence that the design of the product made it unreasonably dangerous. Specifically, the evidence must show that a prudent manufacturer who was knowledgeable about the risks would not have placed the particular product in the stream of commerce. Mere speculation that a product might be improved on does not constitute evidence of a design defect. A manufacturer is not required to design the best product that is scientifically possible.

Basic

Write a case brief for People v. Nelson, 132 Cal. Rptr. 3d 856 (Ct. App. 2011). If you belong to a writing group or class, circulate a copy of your case brief to each colleague.

Intermediate

Write a case brief for Wilburn v. Commonwealth, 312 S.W.3d 321 (Ky. 2010). If you belong to a writing group or class, circulate a copy of your case brief to each colleague.

Advanced

Write a case brief for District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570 (2008). If you belong to a writing group or class, circulate a copy of your case brief to each colleague.

Writers work in various ways, often experimenting with many methods before settling into certain habits. But most writers need a way to set down their yet-unformed ideas in some way other than a top-to-bottom order.

Once you’ve thought of some points to make—even if they’re not fully formed—you’ve already begun the writing process. But you’re not yet ready to begin writing sentences and paragraphs. You’re ready to start outlining, which itself can be a multistep process. Here I’ll discuss producing an outline that probably won’t resemble the outlines you’ve tried for other writing projects. More on this in a moment. First, let’s break down the writing process into its component parts.

It’s useful to think of writing as a four-step process:

1. Think of things you want to say—as many as possible as quickly as possible.

2. Figure out a sensible order for those thoughts; that is, prepare an outline.

3. With the outline as your guide, swiftly write out a draft.

4. After setting the draft aside for some time (whether minutes or days), come back to it and edit.

These four steps derive from a system developed by Betty Sue Flowers, a former University of Texas English professor. She has named each of the steps: (1) Madman, the creative spirit who generates ideas; (2) Architect, the planner who ensures that the structure is sound and appealing; (3) Carpenter, the builder who makes the corners square and the counters level; and (4) Judge, who checks to see whether anything has gone wrong.2 Each character represents a separate intellectual function that writers must work through.

The Madman, essentially, is your imagination. This character, though sometimes brilliant, is almost always sloppy. When you’re in the Madman phase, you’re going for copious thoughts—as many as possible. Ideally, though, you won’t be writing out sentences and paragraphs. Rather, you’ll be jotting down ideas. And if you get into the swing of it, your jottings will come fast and furious.

You’ll need to protect the Madman against the Judge, who hates the Madman’s sloppiness. If you don’t restrain the Judge in these early stages of the writing process, the Madman could be at considerable risk. Writers commonly have little battles in their heads if the hypercritical Judge is allowed to start censoring ideas even as the Madman is trying to develop them. The result is writer’s block. The one thing all slow writers seem to have in common is that they will not go on to sentence two until sentence one is perfect. By the time they get to the end of the paragraph, the Judge still isn’t satisfied, so they cross it out and start again. Fast writers never bring in the Judge that early in the writing process; this enables them to use the process to discover what they have to say. The perfectionistic, Judge-dominated writers view their initial efforts as producing a final product, which is why it takes them so much longer to get it done. So learn to keep the Judge out of the Madman’s way.

The other steps are equally important.

Once you’ve let the Madman come up with ideas—in no particular order—the Architect must arrange them. But it’s virtually impossible for the Architect to work well until the Madman has had free rein for a while. Although initially the Architect’s work might be nonlinear, you’ll ultimately need a linear outline—a plan that shows the steps on the way from the beginning, through the middle, to the end. Typically, in legal writing, you’ll arrange your points from the most to the least important—and then clinch the argument or analysis with a strong closer.

The Architect’s work product should be in complete sentences—not mere phrases. Why? You should be working with full propositions, not just scraps of ideas. A good outline can be as simple as three propositions arranged in their most logical and powerful order.

Next is the Carpenter’s turn in the lead. This is where you begin writing in earnest. Following the Architect’s specifications, the Carpenter builds the draft, joining sentence to sentence and paragraph to paragraph. Of course, the Architect’s blueprint makes the Carpenter’s job much easier. Ideally, the Carpenter writes quickly, treating the outline as a series of points that need elaboration.

For many people, the carpentry is the most unpleasant part of writing. They find it hard to sit down and produce a draft. But this problem stems largely from skipping the Madman and Architect stages—as if any writer could do three things at once: think of ideas, sequence them, and verbalize them. That’s not the way it works, even for superb writers. In any event, the Carpenter’s job becomes relatively easy if the Madman and Architect have done competent work beforehand.

Again, the Judge must stay out of the Carpenter’s way. If you’re constantly stopping yourself to edit the Carpenter’s work, you’re slowing yourself down. And you’re getting into a different frame of mind—that of editor, as opposed to writer. Still, though, the Carpenter exercises considerable discretion in following the Architect’s plans and makes architectural refinements here and there when producing paragraphs and sections.

When you have a draft, no matter how rough, the Judge can finally take over. For many writers, this is where the fun begins. You have the makings of a solid piece of writing, but now you can fix the ragged edges. The Judge does everything from smoothing over rough transitions to cutting unnecessary words to correcting grammar, spelling, and typos. An alternative name for the Judge is “Janitor” because a big part of what the Judge does is tidy up little messes.

Each character has an important role to play, and to the extent that you slight any of them, your writing will suffer. If you decide, for example, to “rough out” a draft by simply sitting down and writing it out, you’ll be starting the whole process at the Carpenter phase. You’ll be asking the Carpenter to do not just the carpentry but also the Madman’s and the Architect’s work. That’s a tall order. People who write this way tend to produce bad work. And they tend to procrastinate.

If you decide that you can begin an outline with a Roman numeral, you’ll still be asking a lot: the Architect will have to dream up ideas and sequence them simultaneously. And worse: whatever your I-II-III order happens to be at this early stage will probably become fossilized in later drafts. Most writers’ minds aren’t supple enough to allow part IV to become part I(D) in a later draft, even if it logically belongs there.

That’s why it’s critical to let the Madman spin out ideas in the early phases of planning a piece. Ideally, the ideas will come to you so fast and fluidly that it’s hard to get them all down as your mind races.

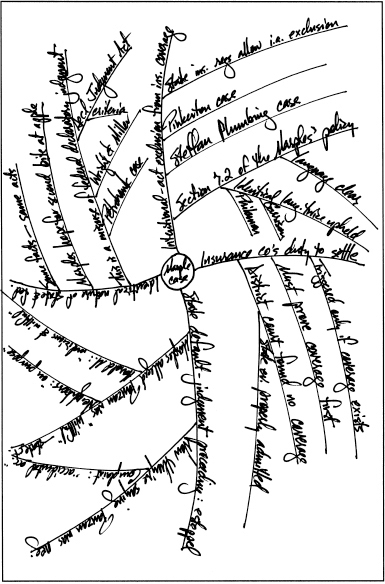

One way to do this—to get yourself into the Madman frame of mind—is to use a nonlinear outline. Among lawyers, the most popular type of nonlinear outline is the whirlybird. It starts out looking like this:

A shorthand name for the project goes in the center. Then you begin adding ideas—the more the better. For every major idea you have, use a branch off the center circle. For supporting ideas, try branching off from a major branch. Everything you might want to mention goes into the whirlybird—which has no top and no bottom. You’re striving for copious thoughts without having to worry about where they go, how they fit together, or what they’ll look like when put in the right order. Here’s an example:

Once you’ve finished a whirlybird—whether it takes ten minutes or ten hours—you’ll probably find it easy to work the elements into a good linear outline. You’ll know all the materials. It will just be a matter of having the Architect organize them sensibly. The next step might look like this:

An insurer’s duty to settle requires proof of actual coverage, and the Milnes assert that they have proof of coverage. But in a previous, related proceeding, they proved up a default judgment by arguing that the person they now claim was negligent harmed them intentionally.

A. The district court did not find that there was coverage, so Panzan Insurance properly refused a settlement offer.

B. The Milnes cannot contradict the factual and legal position they took in state court:

(1) The equitable doctrine of judicial estoppel prevents a party from taking a position contradictory to the position taken on another issue or in a previous but related proceeding.

(2) In state court, the intentional nature of the act that harmed the Milnes was crucial to obtaining the default judgment, and they presented evidence of intent.

(3) The policy does not cover intentional actions, and the state-court evidence is fatal to their claim against Panzan, so the Milnes presented evidence that the act was not intentional.

Once you have this type of linear outline—something that many writers can create only if they do a nonlinear outline first—writing your first draft becomes much less intimidating. More on this in a moment.

Lawyers who have tried using the whirlybird before drafting a linear outline commonly cite several advantages:

• It encourages creativity. It helps you think of things you might otherwise miss. Brainstorming becomes easier because the creative mind tends to jump around. You eliminate the straitjacketing effect of As, Bs, and Cs, which can cause you to force ideas into premature categories.

• At the same time, the whirlybird can help in free-form categorizing.

• It makes getting started fairly easy. It’s stress free. You can avoid writer’s block.

• As some of the same ideas emerge in different contexts, you can see more clearly the interconnections between your ideas.

• It’s a great way to discover your key points—and to distill your thoughts.

• Once you know all the options, you can more confidently select what your lead will be.

• The whirlybird is an excellent reminder of ideas that might otherwise get dropped.

Once the Architect has finished organizing the Madman’s ideas, the Carpenter’s job—the one that writers most often put off—becomes easier. It’s just a matter of elaborating. Further, the Judge will be able to focus on matters of form and style, and that’s what the character is best suited for. The Judge shouldn’t have to think on several levels at once.

If you were to give me a pile of writing samples, I’d critique them according to this paradigm:

• The writer whose prose is “correct” but dry and dull needs work on the Madman.

• The writer who uses no headings (see § 4)—and for whom it would be difficult to devise headings once a draft is done—needs work on the Architect.

• The writer who has problems with transitions (see § 25) needs work on the Carpenter.

• The writer who allows typos in the final draft needs work on the Judge.

Each character in the Flowers paradigm must have its time at the helm. What you don’t want to do is let one character dominate so much that the others get squeezed out. Your writing will suffer.

Perhaps the most crucial phases—because they’re the most unpredictable and mysterious—are the first two: Madman and Architect. They will determine the degree of originality and insight in your writing. If you don’t consciously involve them, the Carpenter will waste a lot of time. A carpenter must follow plans.

So as you can see, writing well is much more than getting the grammar and spelling right. Those are matters for the Judge, who in the end should tidy things up. Don’t underestimate this tidying: it requires loads of know-how and serious stamina. Meanwhile, though, your Judge won’t contribute many interesting or original thoughts.

Although you might fear that you’ll never have time to go through all four phases, try it: it’s one of the surest and quickest ways to good writing. In a one-hour span, you might spend 10 minutes as Madman, 5 minutes as Architect, 25 minutes as Carpenter, and 10 minutes as Judge—with short breaks in between. That’s a productive way to spend an hour. But it won’t happen without conscious planning—and ensuring that you allocate meaningful time to each stage. You have to plan how you’re going to turn mushy thoughts into polished prose.

Basic

While planning and researching a writing project, fill out a whirlybird. (You’re ready to begin once you know enough about the problem to have an idea or two.) Use unruled paper. Take your time. Fill as many major and minor branches as you can, and feel free to add more. Then, when the paper starts getting full—and only then—create a linear outline consisting of three full-sentence propositions. Once you’ve written those, rethink their order and make any necessary adjustments. Remember that you’re working on the basic unit of organization; once you have that, you’ll organize further according to issues and answers.

Intermediate

Do the same with a trial or appellate brief. Fashion your full-sentence propositions into point headings.

Advanced

Do the same with a journal article or continuing-legal-education paper. For this one, your whirlybird may require a large sheet of butcher paper.

Though ordering your material logically might not seem difficult, it will often be one of your biggest challenges, especially because of some odd conventions in law. One example among many is the stupefying use of alphabetized organization in certain contracts. That is, some formbooks actually have provisions in alphabetical order according to headings: assignments, default, delivery, indemnity, notices, payment, remedies, and so on. A far better strategy—if clarity is the goal—is to follow the logic and chronology of the deal. What are the most important provisions? In what order are the parties to do things?

Even when narrating events, legal writers often falter when it comes to chronology. Disruptions in the story line can result from opening the narrative with a statement of the earlier steps in litigation. Here, for example, is a judge’s opener that recites events in reverse chronological order—a surprisingly common phenomenon:

This is an appeal from an order of the Circuit Court of Jackson County entered February 10, 2011, affirming the June 20, 2010 order of the Mississippi Workers’ Compensation Commission directing the Jackson County School District to pay immediately the assessed amount of $52,218 to the South Mississippi Workers’ Compensation Fund.

For most readers, that doesn’t easily compute.

Even if the order isn’t a strictly reversed chronology but merely starts in the middle of a story, the reader’s difficulties can be insurmountable. Consider a before-and-after example. It comes from an amicus brief submitted to a state supreme court, seeking to overturn a lower court’s ruling on an aspect of the state’s oil-and-gas law. Here is the original two-paragraph opener, in which the two meanings of hold in the first paragraph present a stumbling block:

I. Introduction

The Court of Appeals held that capability of the lease to produce in paying quantities does not hold an oil and gas lease after the primary term and that actual marketing is necessary to perpetuate the lease in the secondary term. The Court of Appeals’ holding is contrary to the fundamental principle of Arkansas oil and gas law that marketing is not essential to hold a lease where there is a well capable of producing in paying quantities.

The Court of Appeals’ decision will create title uncertainty in thousands of oil and gas leases in this state. As this Court is well aware, thousands of wells across Arkansas have been shut-in or substantially curtailed from time to time. Under the Court of Appeals’ decision, it will be argued that many of these currently productive and profitable Arkansas oil and gas leases terminated years ago if there was a timeframe when gas was not taken from the lease in paying quantities for the period specified in the cessation of production clause—often as short a time as sixty days. The issues of this case already affect a dozen or more cases now being litigated in Arkansas. The Court of Appeals’ decision will encourage waste of a valuable natural resource and harm lessors and lessees by requiring continuous marketing of gas even at fire-sale prices.

Could you track the argument there? Does it hold any dramatic value?

Now consider a revision that emphasizes the underlying story. The editor has achieved clarity partly by highlighting the historical perspective, partly by tucking in some transitional words, and partly by specifying that the whole case hinges on the meaning of the word produced (admittedly in an obscurely named clause: the habendum clause). Note, too, the heightened drama of the case (on which huge sums of money were riding):

I. Introduction

Since first considering the issue more than 30 years ago, the Arkansas Supreme Court has consistently held that the word produced—as used in the habendum clause of an oil-and-gas lease—means “capable of producing in paying quantities.” The Court of Appeals in this case overrode that settled principle by holding that (1) capability to produce in paying quantities does not maintain an oil-and-gas lease after the primary term—rather, gas sales and deliveries are necessary to perpetuate a lease in the secondary term; and (2) the cessation-of-production clause is a special limitation to the habendum clause. The court further held, incorrectly, that equities may be ignored in determining whether a lease terminates.

These holdings, besides being legally incorrect, are apt to prove catastrophic, since they will create title uncertainty in oil-and-gas leases across this state. As this Court well knows, thousands of Arkansas wells have been shut in or substantially curtailed from time to time. Under the new ruling, litigants can now argue that many currently productive and profitable Arkansas oil-and-gas leases actually terminated years ago—if, for example, gas was not taken from a lease in paying quantities for the period specified in the cessation-of-production clause—often as short as 60 days. Indeed, the issues in this case already affect a dozen or more Arkansas cases in various stages of litigation. The Court of Appeals’ decision, besides encouraging waste of a vital natural resource, and besides spawning needless litigation, will harm lessors and lessees alike by requiring continuous marketing of gas, even at fire-sale prices.

What qualities distinguish the two versions? What is the sequence of each? Which one is more logically organized, assuming that these are the first words a reader encounters? Did either version seem impenetrable when you first started reading it? What does that say about the writing?

Exercises

Basic

Improve the sequence of ideas in the following sentence. Start like this: “In March 2010, Gilbert Spaulding applied to the Workforce Commission for extended unemployment benefits.” Then use one or two extra sentences.

• The lower court did not err by affirming the Workforce Commission’s denial of Spaulding’s request for extended unemployment benefits, since those benefits were not available during the period for which he sought eligibility.

Improve the sequence and phrasing of ideas in these sentences, perhaps by breaking them into separate sentences:

• The state supreme court reversed the intermediate appellate court’s affirmance of a summary judgment granted to Pilsen Corporation, the plaintiff, which had only requested a partial summary judgment on the discrete issue of fraud.

• The issue is whether Davis Energy has granted its neighbors an easement to use a private road that enters a Davis fuel-storage yard, when for three years Davis has had a guard at the road’s entrance but has posted no other notice about private property or permission to enter, and for seven years the owners of adjacent property have used the road to reach their own property.

• The Plaintiff Los Angeles Dodgers, a corporation with offices and its principal office in Los Angeles, California, is the owner of a professional baseball team that, since 1958, has played baseball in Los Angeles, California, and before 1958 played baseball in Brooklyn, New York, under the name “the Brooklyn Dodgers,” but in that year moved the site of its home games from Brooklyn to Los Angeles.

Intermediate

Rewrite the following passages to reassemble the elements in chronological order. Again, you might need to break one or more sentences into separate sentences.

• This action arose out of a request by Pan-American to cancel its surety bond posted with the Land Reclamation Commission to ensure reclamation on a portion of the Prelancia Fuels mine site. The Commission filed a petition for declaratory judgment and application for a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction on February 16, 2006, to determine whether Pan-American could lawfully cancel its surety bond. Pan-American made its request after legislation had been passed that, according to Pan-American, would increase its liability under the bonds. The trial judge disagreed with Pan-American. At the request of the Commission, after a brief evidentiary hearing, a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction were granted on February 16, 2006, preventing Pan-American from canceling the bond at issue until final judgment on the declaratory-judgment action.

• In Sinclair, the court awarded the niece of Sinclair a constructive trust. Sinclair’s niece was suing Purdy’s estate for one-half interest in property that she claimed her uncle owned and had promised to bequeath to her in exchange for caring for him until his death. The court observed that the property was purchased in his sister’s name. This was done for business purposes and because he and his sister shared a close relationship. There was also an agreement between the siblings that the sister would be allowed to keep only half the property. The court ruled that withholding the property from the niece would be a breach of promise; hence, a constructive trust was awarded in favor of the niece.

• Kathcart filed the instant patent application on April 11, 2012, more than one year after he filed counterpart applications in Greece and Spain on November 21, 2010. Kathcart initially filed an application in the U.S. on November 22, 2009, claiming most of the same compounds as in the instant application. When he filed abroad, however, in 2010, he expanded his claims to include certain ester derivatives of the originally claimed compounds. It is the claims to these esters, which Kathcart has made the subject of a subsequent continuation-in-part application, the application now before the court, that are the issue here. Both foreign patents issued before the instant application in the U.S., the Greek patent on October 2, 2011, and the Spanish patent on January 21, 2012.

Advanced

Find a published case in which the presentation of the facts is marred by disruptions in chronology. Write a short explanation specifying why the narrative was difficult for you to read. Rewrite the factual statement as best you can, omitting irrelevant facts and putting in brackets any facts you might want to add (but weren’t given in the case itself). If you belong to a writing group or class, circulate a copy of your before-and-after versions to each colleague.

Once you’ve determined the necessary order of your document in the outlining stage, divide it into discrete, recognizable parts. This may well present a serious challenge because the legal mind isn’t very good at division. Its strength is multiplication—multiplying thoughts and multiplying words. Still, with a little effort, you can learn to divide a document into readable segments of text. You can do this even as you’re writing.

While you’re figuring out a structure, make its parts explicit. Doing so will help you as well as your readers. The more complex your project, the simpler and more overt its structure should be. When writing a memo or brief, try thinking of its contents as a series of points you wish to make. Each point will account for a chunk of the whole—a chunk on this, a chunk on that, yet another chunk on this other point. For each of these parts, ask yourself, “What would make a pithy section heading here?” Then put it in boldface so it really stands out. You may need to go even further by devising subheadings as well. Busy readers welcome having a stream of information divided up this way.

In fact, headings have many advantages:

• They help you organize your thoughts into categories.

• They give readers their bearings at a glance.

• They provide some visual variety to your pages.

• They make the text skimmable—an important quality for those in a hurry and those who want to return to a specific part of your argument.

• They instantly signal transitions.

• When collected into a table of contents, they provide a road map for the whole document, however long it might be (see § 45).

You’d think these things would be obvious. But to many writers they’re not.

Let’s take a short example—a paragraph from an amended agreement of sale. At first it might look all right:

4.5 Upon the additional property closing, the Purchaser will:

(A) authorize the title company to release the additional property escrow funds to the Additional Property Seller;

(B) execute and deliver such documents as may be reasonably required by the Additional Property Seller or the title company;

(C) deliver a certificate of good standing, a certificate of Purchaser’s corporate existence, and copies of all documents requested by the Additional Property Seller to show the Purchaser’s corporate existence;

(D) execute and deliver the additional bill of sale, assuming the obligations under the additional contracts from the date of the additional property closing and the obligation relating to the physical and environmental condition of the additional property;

(E) at the additional property closing, Purchaser and the Additional Property Seller will execute and deliver an additional closing statement setting forth the amount held in the additional property escrow and all prorations, adjustments, and credits to that escrow, and, if necessary, a post-closing agreement for the additional property closing for any adjustments based on estimates that are to be readjusted after the additional property closing.

The problem is that paragraph 4.5 has been plopped into the midst of paragraphs 4.1, 4.2, 4.3, 4.4, 4.6, and so on—not one of which has a heading. Without significant effort, the reader won’t be able to see what each paragraph is about.

“Well,” the naysayer might object, “agreements of sale aren’t supposed to be pleasure reading. After all, other lawyers are paid to read them!” But that’s not really an argument you can make with a straight face. And we’re not talking just about making the reader’s task more pleasurable.

When we put a heading on the paragraph, look what happens:

4.5 Purchaser’s Obligations upon Closing. Upon the additional property closing, the Purchaser will:

(A) authorize the title company to release the additional property escrow funds to the Additional Property Seller;

(B) execute and deliver such documents as may be reasonably required by the Additional Property Seller or the title company;

(C) deliver a certificate of good standing, a certificate of Purchaser’s corporate existence, and copies of all documents requested by the Additional Property Seller to show the Purchaser’s corporate existence;

(D) execute and deliver the additional bill of sale, assuming the obligations under the additional contracts from the date of the additional property closing and the obligation relating to the physical and environmental condition of the additional property;

(E) at the additional property closing, Purchaser and the Additional Property Seller will execute and deliver an additional closing statement setting forth the amount held in the additional property escrow and all prorations, adjustments, and credits to that escrow, and, if necessary, a post-closing agreement for the additional property closing for any adjustments based on estimates that are to be readjusted after the additional property closing.

Subparagraph (E) suddenly sticks out: it doesn’t fit within the category of the heading, and it doesn’t fit with the other subparagraphs. (On parallelism, see § 8.) We’ll need to move it somewhere else. Depending on the larger context, we’ll either make it as a subparagraph in another section or make it a paragraph of its own. But all this might have been difficult to see if we hadn’t gone to the trouble to think about headings for every decimal-level paragraph.

State and federal judges routinely emphasize the importance of point headings in briefs. They say that headings and subheadings help them keep their bearings, let them actually see the organization, and afford them mental rest stops. Headings also allow them to focus on the points they’re most interested in. The key characteristics of sound point headings for persuasive writing are that they (1) are complete sentences; (2) contain (typically) 10 to 35 words; (3) are capitalized normally (never in all caps) but set in single-spaced boldface type; and (4) contain not just a conclusion but ordinarily a reason as well. In the following example, from the United States Solicitor General’s Office, the point headings as they appear in the table of contents convey the gist of the argument at a glance:

Argument:

Prison and jail officials need not have individualized suspicion to justify strip searches of incoming detainees who will be placed in the general prison or jail population |

9 |

A. The Fourth Amendment permits corrections officials to conduct reasonable searches to protect inmates and officers and to maintain institutional security |

10 |

B. Compelling interests in maintaining jail safety and security justify the searches in this case |

16 |

C. Petitioner’s proposed rule is unworkable and unsupported by federal policy and practice |

24 |

Conclusion |

32 |

A device as simple as headings can help you think more clearly.

Exercises

Basic

Go to the website of the US Solicitor General’s Office: http://www.justice.gov/osg. Find two briefs with particularly effective headings. If you’re a member of a writing group or class, circulate a copy of the table of contents and be prepared to discuss why you think the headings are so effective.

Intermediate

Find a state statute or regulation having at least three sections with headings that don’t adequately describe the sections’ contents. Devise better headings. If you’re a member of a writing group or class, be prepared to explain why your edits would improve the regulation.

Find a transactional document with long stretches of uninterrupted text. Break up the long paragraphs into smaller paragraphs and add headings where appropriate. For a model of this approach, see Garner, Securities Disclosure in Plain English §§ 41-43 (1999). If, as a result of this exercise, you find that the organization is poor, note the organizational deficiencies. If you’re a member of a writing group or class, circulate a copy of the relevant pages and be prepared to explain where your headings would go and to discuss any organizational problems you uncovered.