The phrase “analytical and persuasive writing” encompasses general expository prose: letters, memos, briefs, judicial opinions, and the like. The only excluded items, essentially, belong to the category known as “legal drafting” (see Part Three). In writing to analyze or persuade, strive for these major goals:

• Get your point across quickly with a concrete summary up front.

• Focus the analysis or argument.

• Make it interesting.

• Supply smooth transitions.

• Quote smartly and deftly.

Most legal writers don’t attain these goals. The tips that follow will allow you to stand out as one who does attain them.

All good expository writing has three parts: an introduction, a main body, and a conclusion. You’d think everyone knows this. Not so: the orthodox method of brief writing, and the way of many research memos, is to provide only one part—a middle.

How so? Well, formbook-style openers typically just restate the title. For example: Plaintiff Pantheon Corporation, by and through its attorneys of record [full address], files this, Pantheon’s Memorandum in Support of Its Motion for Summary Judgment. Hence the title. That’s why it’s called “Pantheon’s Memorandum in Support of Its Motion for Summary Judgment” just an inch above this wasteful sentence. In some briefs, the hence-the-title sentence starts with Now come. . .

The conclusion, meanwhile, is equally formulaic: For all the foregoing reasons . . . or (in antique language) Wherefore, premises considered,. . . These concluding refusals to summarize are every bit as common as stale openers.

If you’re writing that way, you’re neglecting the most critical parts of the brief: the beginning and the end.

A Proper Opener

The ideal introduction concisely states the precise points at issue—concretely—in a way that is fully comprehensible to any intelligent reader in a first reading. Stripped of all extraneous matter, the intro serves as an executive summary: it places the essential ideas before the reader.

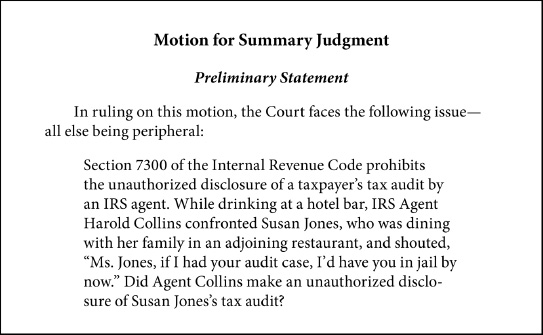

Fortunately, you’re almost always able to put a preliminary statement on the first page of a brief, even if the rules don’t call for it. Just put it there—as far up front as you can. In at least two jurisdictions, New York and New Jersey, including a preliminary statement is the norm—though few lawyers put them to good use. And in most other jurisdictions, very few lawyers use intros. But a good one is always advisable.

How do you decide what goes into an introduction? Figure out first how many arguments you want to make, and then turn each one into an issue statement.

Let’s say you have a single issue. You might begin this way:

That type of opener uses the “deep issue” technique (see § 22)—in which the issue is framed in separate sentences totaling fewer than 75 words.1

Although the deep issue is hard to beat, you can also state the issue less formally in the preliminary statement. Here’s an example from another summary-judgment motion:

Under Alabama law, a personal representative can bring a wrongful-death action on behalf of a decedent only if the decedent could have maintained a claim at the time of death. (Ala. Code § 6-5-410(a).) The decedent’s medical records establish that he was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2006. So the applicable two-year statute of limitations on the decedent’s personal-injury claim elapsed no later than 2008—nearly two years before his death. Because the two-year statute of limitations would have barred the decedent from pursuing a lawsuit at the time of his death in 2010, his personal representative is likewise barred from bringing suit.

In short, don’t depend on a rule to tell you to put the issues up front. True, some court rules require them at the outset, as U.S. Supreme Court Rule 14 does. But many rules, especially in trial courts, don’t say anything about them at all. And even on appeal, various state-court rules require mere “Points Relied On” or “Points of Error”—something rather different from true issues. Despite these requirements—which you must comply with—always add a preliminary statement that highlights the issues. Your judicial readers will be grateful.

The middle should—with a series of headings and perhaps subheadings (see § 4)—develop the reasoning by which the writer seeks to prove the affirmative or the negative of the issues stated in the introduction. How do you do that? First, select the main ideas that prove your conclusion. Then arrange them in a way that shows the relations they naturally bear to one another and to the essential idea or ideas. All the main headings and subheadings should drive the reader toward your conclusion.

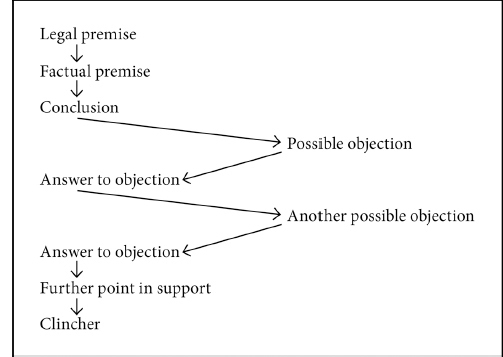

Let’s say you have three issues. You’ll have three parts in the body, typically proceeding from the strongest to the least strong. (Forget the weak arguments.) Each part will be organized to do four things:

• Set forth the legal rule embedded in the issue statement.

• Show how the factual points fit into this rule.

• Deal with counterarguments.

• Drive the point home with an additional reason or set of reasons.

That’s the basic way to organize the argument for each issue.

A tricky part is dealing with counterarguments (see § 30). You must weigh and address all serious ones, and the dialectical method of arguing is the best tool for this. A dialectic is something like a pendulum through time. At its simplest, its form is thesis-antithesis-conclusion. You’ll need to counter the antithesis to your position.

A Strong Closer

The conclusion should briefly sum up the argument. If you’re writing as an advocate, you’ll need to show clearly what the decision maker should do and why. One good method is to answer the questions posed in the opener.

Just as your opener is crucial, so is your closer. It’s your chance to sum up—preferably in a fresh, expansive way. Yet the classic Wherefore, premises considered,. . .—a form with regional variations throughout the country—is a formulaic cop-out that says nothing.

To close forcefully, recapitulate your main points concisely—and, if you can, freshly. Put them in a nutshell, without vague references to “the foregoing reasons” or “the aforementioned argument.” You’ll project an image of confidence and professionalism.

A Sea Change

All this may sound obvious. But judging from what lawyers actually do, it’s little known. Go down to the courthouse sometime and look at the filings: you’ll see that more than 85% of them have stock openers and closers. They’re all middle. This absence of logical structure—more than anything else—explains why so many briefs are inadequate. Likewise, many if not most research memos assume that the reader is as familiar with the subject as the writer—as a result of which no good, comprehensible summary appears. Although you’ll see a heading “Summary” or “Question Presented,” the text is typically incomprehensible to anyone not already working on the matter. For a research memo, which should always have a long shelf life, that is quite bad.

Lawyers fear summarizing. They fear true openers and closers: they generally know that creating strong ones takes a lot of work. So they take the easy way out.

But remember what Samuel Johnson, the great English critic and dictionary writer, once said: “What is written without effort is in general read without pleasure.”2 Talk to judges, and they’ll tell you that they generally read briefs without the remotest hint of pleasure. It shouldn’t be that way.

Exercises

Basic

Find a brief or judicial opinion that has a particularly good opener and closer. (For a brief, you might look at books with model briefs. You might also look at continuing-legal-education materials on appellate practice.) If you belong to a writing group or class, circulate a copy to each colleague. Be prepared to explain why you think the introduction and conclusion are effective.

Intermediate

Find a research memo that has no proper opener or closer—that is, one that’s all middle. Write both a summary that could be added at the start and a fresh conclusion. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy of your work to each colleague. Be prepared to discuss the problems in the original and how you tried to solve them.

Advanced

Find a motion (or memorandum in support) or a brief that launches straight into a statement of facts. Write a new preliminary statement that could be inserted at the beginning of the motion or brief. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy of your summary to each colleague. Be prepared to discuss the problems in the original and how you tried to solve them.

Virtually all analytical or persuasive writing should have a summary on page one—a true summary that encapsulates the upshot of the message. This upshot inevitably consists of three parts: the question, the answer, and the reasons. I don’t know of any exceptions. It’s true of good research memos, good briefs, and good judicial opinions. The summary is your opener.

American schools once taught what was called “précis writing”—and every American high-school student knew what a précis was: an accurate summary of a much longer piece. Teachers gave their students a three-page essay and asked them to state the gist of it in a single paragraph. Or the students would recast a three-page essay as a single paragraph. Schools did these drills frequently until the 1950s or so, when précis writing fell out of fashion.

If only it hadn’t fallen into decline, students would enter law school much better equipped to do what good lawyers must do: work on a complicated case for months or even years but be able to distill its essence down to a page.

If you include an up-front summary, one major by-product will be that you’ll think more clearly. Why? Because if you haven’t isolated the most important idea, you haven’t been thinking as clearly as you might. By highlighting the issues and conclusions on page one, you’ll end up (1) testing the validity of those conclusions more thoroughly, (2) ensuring that you carry through with them when you get to the middle, and (3) eliminating slag that your research has produced but that doesn’t help the analysis.

To summarize effectively, be sure that you include the issues, the answers, and the reasons for those answers. If you’re writing a memo, page one ends up looking something like the example on page 74. If you’re writing a brief, page one should start with a preliminary statement that looks akin to the one on page 75.

Have you noticed that the issue here contains more than one sentence? There’s a reason for that: it’s by far the best way to frame issues. You can do it in one sentence, of course, but that method typically ruins the chronology, forces you into overlong sentences, makes the issues unduly abstract, and results in altogether incomprehensible statements.

Instead, try the “deep-issue” method, which means that you’ll:

• Put the issues first.

• Never—never—begin with Whether or any other interrogative word.

• Break each issue into separate sentences.

• Keep each issue to 75 or fewer words.

• Weave in enough facts, and arrange them chronologically, to show how the problem arises.

• Forget about whether the answer is yes or no.

If you’re writing an analytical issue for a memo, the question will be open-ended, as in these three:

• While investigating a complaint about loud music, Officer Smith knocked on Jimmy Jeffson’s door. The music volume lowered suddenly, and Jeffson opened the door. Officer Jones then stepped into the apartment as Jeffson tried to close the door. If Officer Smith did not have a search warrant and no exigent circumstances existed, did his entry into the apartment violate Jeffson’s Fourth Amendment privacy protections? [64 words]

• Under Georgia law, communications between psychiatrists and their patients are absolutely privileged. Ms. Jenkins claims that Mr. Fulham’s unwelcome sexual advances caused her extreme emotional harm, triggering her need for psychiatric treatment. Given that Ms. Jenkins has placed her need for this treatment at issue, has she waived the psychiatrist-patient privilege? [52 words]

• Under Tennessee law, a judgment is not final until it is stamped “filed” by the court clerk. Fulmer was orally granted a divorce on November 10, 2009, and he “remarried” 30 days later. Yet the court clerk did not file-stamp the order from the November divorce until January 18, 2010. Is the remarriage valid? Has Fulmer committed bigamy? [59 words]

You don’t know the answer when you read the question. The answer—the underlying legal rule—should immediately follow an analytical issue of this type.

If, on the other hand, you’re writing a persuasive issue for a brief, the question should suggest the answer you want. The deep issue is cast as a syllogism, with the legal rule (major premise) first, then the factual premise (the minor premise preferably in chronological order), followed by a short, punchy question (the conclusion expressed interrogatively). Here are three good examples:

• In a testamentary bequest, an adjective used for identification purposes does not limit the gift. The will of Anton Dalby’s paternal biological grandfather provides a bequest to “my grandson Anton.” After the will was executed, Anton was adopted by his stepfather, and the biological father’s parental rights were terminated. In the will, does the adjectival use of “grandson” make the gift contingent on the ongoing legal relationship, or does it merely help identify the legatee?

• Sixteen months before trial, Judge Fanchon established “litigation boundaries” for this case, holding that only evidence about oil wells within those geographical boundaries would be admissible. Nelson framed his discovery accordingly. But 27 days into the trial, Judge Fanchon suddenly removed the boundaries and allowed Celobar to introduce prejudicial evidence about land outside the litigation boundaries—land not in dispute. Given that Nelson couldn’t rebut this evidence, was this evidentiary about-face reversible error?

• Under the Supreme Court’s search-and-seizure law, a police officer is held to a more stringent standard than a private security guard. Officer McGee, a policeman working as a security officer, stopped a parent at Gordon Grammar School, flashed his badge, and identified himself as a Chicago policeman. When Officer McGee demanded to see Rothschild’s jacket, Rothschild handed it over, exposing a gun in his vest. Was Officer McGee acting primarily as a private citizen?

Although you could rephrase those issues in single sentences, who would want to? You’d either torture the language or postpone the crux of the problem until later in the writing. The multisentence treatment in fewer than 75 words is the best method for achieving clarity, speed, and power. Once you master the technique, you’ll be a certifiably clear thinker.

Basic

In your own words, state the principal issue decided by a court in a published opinion. Use the deep-issue technique.

Intermediate

Find a judicial opinion that takes several paragraphs before getting to the point. Rewrite the opening paragraph with a more satisfactory opener. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy of both versions to each colleague.

Advanced

Take a published case that includes a dissenting opinion. Frame the deep issue decided by the majority. Then frame the most nearly corresponding issue that a dissenter would have wanted. If you’re working in a group, be prepared to discuss the basic disagreement between the two sides. Below is an example of how you might frame divergent issues on the same point:

#1 Missouri’s Spill Bill imposes liability on a “person having control over a hazardous substance” during a hazardous-substance emergency. Binary Coastal, as a landowner, controlled its land when it installed gasoline tanks and then leased the land to a service station. In February 2010, a hazardous-substance emergency occurred on the land. Was Binary Coastal a “person having control”?

#2 Missouri’s Spill Bill imposes liability specifically on “a person having control over a hazardous substance” during a hazardous-substance emergency. In January 2010, Binary Coastal leased some land to a service station but had nothing to do with day-to-day operations or with the activities involving hazardous substances. In February, Binary Coastal’s lessee experienced a release of hazardous substances. Did Binary Coastal have control of these substances at the time of release?

And here’s an example from a published case3—one in which no judge dissented.

#1 Under principles of statutory construction, when statutes are in conflict, the specific controls over the general. In 1986, the Legislature narrowly tailored the retirement statutes so that a retiree over the age of 55 who decided on a lump-sum payment of benefits would forfeit certain other benefits. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission now claims that this amendment is impermissible in light of the 1963 age-discrimination statute, which is broadly worded. Which statute controls?

#2 Since 1963, the statutory law of this state has prohibited age discrimination. Yet in 1986, the Legislature amended the retirement statutes in a way that forced retirees over the age of 55 to forfeit some of their benefits if they chose a lump-sum payment—but allowed those under 55 to make this choice with no such penalty. Did the Legislature intend this anomalous reversal of its long-held policy against age discrimination?

One requisite for clear exposition—and for getting thoughts across to readers—is knowing how to establish a context before embarking on details. Otherwise, your readers won’t know what to make of the details. They’ll get impatient, and they might well give up on you.

When you state the facts of a case, then, you need to be sure that you first give an introductory summary. That way, your readers will have a framework for understanding the case as the factual statement unfolds.

You’ll have to work hard to distinguish what is necessary from what isn’t. Although details can be important, you must omit the tedious ones. You’re not trying to compile details; you’re trying to select them knowledgeably. Here’s a good test in winnowing important from unimportant facts: if it isn’t necessary to understanding the issues or if it doesn’t add human interest, then leave it out.

In legal writing, the overparticularized style most commonly manifests itself in litanies of dates, as in this statement of facts:

On February 12, 2010, at or about 3:00 p.m., while showering, Plaintiff fell to the floor when her bathroom ceiling collapsed, striking her on the head. On February 12, 2010, at 4:06 p.m., paramedics took her, unconscious, to the hospital.

On February 13, 2010, Plaintiff sued the apartment owner, alleging negligence and gross negligence in failing to maintain the premises. On March 6, 2010, Plaintiff visited Dr. Eugene Higginbotham, an orthopedic surgeon, who confirmed the diagnosis but concluded that surgery was not indicated, given Plaintiff’s uncontrolled diabetes and her obesity. On the following dates, Plaintiff visited a physical therapist for her back condition: March 12, 2010, April 15, 2010, June 6, 2010, August 2, 2010, October 5, 2010, and November 16, 2010. The apartment owner settled the case for an undisclosed sum on December 10, 2010.

On March 17, 2011, at or about 2:25 a.m., Plaintiff allegedly slipped and fell on a candy bar in a deserted hallway of Mega Electronics, Inc., where she worked as a night custodian. On March 17, 2011, at 2:40 a.m., Plaintiff reported the incident to the company nurse, who sent her home. On March 18 and 19, 2011, Plaintiff called in sick. On March 19, 2011, Plaintiff visited Dr. Felix Seaniz, who diagnosed her condition as a herniated disk caused by the recent fall at Mega Electronics. During the March 19, 2011 visit, when asked about previous back problems, Plaintiff failed to disclose the fall in her shower on February 12, 2010. When asked why, she testified that she believed the February 12, 2010 fall unimportant because she had experienced no back pain since her last therapy session on November 16, 2010.

With the precise dates removed, and some relative times (such as an hour later) supplied, the passage becomes much cleaner. Readers can more easily focus on the story:

In February 2010, while showering, Ms. Walker fell to the floor when her bathroom ceiling collapsed, striking her on the head. An hour later, paramedics took her, unconscious, to the hospital, where she was diagnosed with a herniated disk.

The next day, Ms. Walker sued the apartment owner, alleging negligence and gross negligence in failing to maintain the premises. She then visited Dr. Eugene Higginbotham, an orthopedic surgeon, who confirmed the diagnosis but concluded that surgery was not indicated, given her uncontrolled diabetes and her obesity. During the next nine months, Ms. Walker visited a physical therapist six times for her back condition. In December 2010, a month after her last therapy session, the apartment owner settled the case for an undisclosed sum.

Three months later, in March 2011, Ms. Walker allegedly slipped and fell on a candy bar in a deserted hallway of Mega Electronics, Inc., where she worked as a night custodian. Soon after the alleged fall, she reported the incident to the company nurse, who sent her home. For the next two days, she called in sick. She then visited Dr. Felix Seaniz, who diagnosed her condition as a herniated disk caused by the recent fall at Mega Electronics. During that visit, when asked about previous back problems, Ms. Walker failed to disclose the fall in her shower a year earlier. When asked why at trial, she testified that she believed the earlier fall unimportant because she had experienced no back pain since her last therapy session a few months earlier.

This rewrite reflects what happens when the writer considers the story from the reader’s point of view—the only point of view that really matters.

Exercises

Basic

Rewrite the following passage to improve the story line by omitting needless details:

On September 25, 2007, in a Texas federal district court, R&B Music sought injunctive relief against the McCoys to prevent them from any further use or disclosure of R&B’s trade secrets. On September 26, 2007, the Texas court issued an order restraining the McCoys from using or disclosing certain R&B property and proprietary information. On September 26, 2007, the court set an evidentiary hearing for Tuesday, October 7, 2007, on R&B’s preliminary-injunction motion.

On October 6, 2007, the McCoys moved to dismiss for an alleged lack of venue and personal jurisdiction. Alternatively, they asked the court to transfer the case to an Illinois federal court under 28 U.S.C. § 1404 or § 1406.

On October 7, 2007, when the parties arrived for the injunction hearing, the Texas court indicated an intent to hear testimony and rule on the McCoys’ dismissal or transfer motion, to which R&B had been given no chance to respond. The testimony established that both of the McCoys had had significant contacts in Texas for the past eight years—including daily phone calls and faxes to and from R&B; their three visits to R&B’s Texas headquarters; and their work in negotiating R&B contracts with Texas musicians.

On October 8, 2007, the Texas court transferred the case to this Court, noting that the transfer was for the reasons stated on the record. As the October 7, 2007, transcript reveals, the Texas court decided that while it has personal jurisdiction over John McCoy, it lacked personal jurisdiction over Kate McCoy. According to the court, the case should be transferred because “to accord relief to R&B down here while leaving the Illinois court to deal with Kate McCoy simply would not provide an effective situation” for any of the parties. The judge did not indicate which statutory section governed the transfer.

On October 8, 2007, in the same order, the Texas court further ruled that its September 26, 2007, order restricting both John and Kate McCoy from using or disclosing R&B’s trade secrets would remain in effect until further orders of the Illinois court. On October 13, 2007, R&B filed the present supplemental motion for a preliminary injunction, asking this Court to extend and expand the injunctive relief already granted by the Texas court.

Intermediate

Rewrite the following passage to prune the overparticularized facts and to improve the story line. The passage comes from an appellant’s brief—specifically from a section entitled “Nature of the Case and Material Proceedings in the Lower Courts,” just after the preliminary statement.

On December 26, 2009, the Division of Child Support Enforcement (“DCSE”) issued a Mandatory Withholding of Earnings Order directing the Social Security Administration to deduct $200.00 per month for current child support and $100.00 per month for payment on child-support arrears. On June 18, 2010, Skelton filed a Motion to Quash the Mandatory Withholding of Earnings Order with the Buchanan County Juvenile and Domestic Relations District Court. In the pleading, Skelton requested that the withholding order of the Division be reduced and that he be given credit against arrears for the amount of social-security benefits received by the children, and that the court recalculate the arrears. Hearings on the Motion to Quash in Buchanan County Juvenile and Domestic Relations District Court were held on September 11, 2010, and October 13, 2010. At the September 11, 2010 hearing, the court entered a temporary order requiring $28.50 per month toward current support and requiring $71.50 per month toward the arrears. The Motion to Quash was treated as a Motion for Reduction. The court took the issue of arrears under advisement and directed that the counsel for the parties prepare briefs on the issue concerning credit for a lump-sum social-security payment. The child support was set by using the appropriate code provisions, and neither party objected to the child-support award or the arrears payment.

On October 13, 2010, the Buchanan County Juvenile and Domestic Relations District Court denied the Motion to Quash and ruled that “credit for social-security payments made to the children as to debt owed to the Division is denied.” The Court declined to exercise equitable relief for Mr. Skelton (Appellee) as to any debt owed to custodial parent. Appeal was noted in open court, so no bond was required for appeal.”

This matter was subsequently appealed and tried de novo in the Circuit Court of Buchanan County. At the circuit-court level, the court denied the Division’s request for an appeal bond and ruled that Skelton should receive credit for the $7,086.10 lump-sum social-security benefits paid on behalf of the children of Mr. Skelton. This reduced the child-support arrears from $14,017.14 to $6,931.04. At the date of the circuit-court hearing, all the children were over the age of 18.

The circuit court was reminded that on October 14, 2005, Skelton was found guilty of contempt by the Buchanan County Juvenile and Domestic Relations District Court and was advised “to immediately notify the court of any change in employment, layoff, reduction in wages or hours worked.” The court further warned that “no further delinquency would be tolerated and any change in circumstances must be followed up with a petition to decrease, or else contempt sanctions will be imposed.”

Advanced

Find a passage in which too much detail impedes the progress of the writer’s thoughts. If you’re part of a writing group or class, be prepared to discuss why you think the detail is excessive and how you might prune it.

Although it’s possible to put a topic sentence last or in the middle, the best approach with persuasive writing is to open the paragraph with it. By stating the controlling idea, a topic sentence will lend unity to a paragraph, which typically begins with a shift in focus from what has preceded. The topic sentence will reorient readers to this new focus. And with well-introduced paragraphs, the writing becomes much clearer: readers who are in a hurry will get your point efficiently.

Good writers think of the paragraph—not the sentence—as the basic unit of thought. The topic sentence ensures that each paragraph has its own cohesive content. A good topic sentence centers the paragraph. It announces what the paragraph is about, while the other sentences play supporting roles.

This principle sounds simple, yet legal writers often stumble over topic sentences. The problem commonly occurs in discussing case law. Consider the following paragraph, which begins with a case citation followed by an obscure judicial disposition:

In Johnson v. Cass & Emerson, 99 A. 633 (Vt. 1917), the Vermont Supreme Court reversed the decision of a lower court that had held that the plaintiff was “doing business” in a name other than its own without making the appropriate filing. Id. In that case the plaintiff, W. L. Johnson, used stationery in his dealings with the defendant which contained the words “Johnson’s Employment Office, W. L. Johnson, Prop’r.” Id. at 634. The court observed that the stationery “on its face showed Johnson as the owner of the business . . . [and that] no person could be reasonably misled by it.” Id. at 634-35. The court further implied, however, that if the plaintiff had engaged in misleading acts in addition to the aforementioned stationery, such as the concurrent running of regular advertisements bearing only the name “Johnson’s Employment Agency,” it would have affirmed the decision of the court below. Id. at 635. Thus, in Johnson, the pivotal issue was whether the plaintiff was “doing business” under an unregistered assumed name during his relationship with the defendant, rather than if he had actually held himself out as someone else to the defendant.

That paragraph is quite difficult to follow partly because it lacks a good topic sentence and partly because of disruptions in chronology (see § 3). Both can be fixed with a little effort (citations, of course, would be footnoted—see § 28):

The Supreme Court of Vermont has held that the pivotal issue is whether a plaintiff “does business” under an unregistered assumed name while dealing with someone the plaintiff later tries to sue. In Johnson v. Cass & Emerson, W. L. Johnson, the plaintiff, transacted business with the defendant on stationery with the printed words “Johnson’s Employment Office, W. L. Johnson, Prop’r.” According to the court, the stationery showed that Johnson “was the owner of the business and was doing business under his own name,” concluding that “no person could be reasonably misled by it.” Apart from the stationery, there were no acts suggesting that “Johnson’s Employment Agency” was a registered name. If there had been, the court implied, the result might have been different. But the court held that Johnson could sue in a Vermont court because he did not do business there under an unregistered name.

Notice how, in this revision, the case name doesn’t come up until the second sentence. Delaying the citation typically enables you to write a stronger topic sentence.

Whether you’re discussing cases or something else, look closely at your topic sentences when revising your prose. A reader should get most of the story from skimming the topic sentences.

Exercises

Basic

Write a new topic sentence for the following paragraph—one that you could insert at the beginning while leaving the following sentences intact:

Over the past 100 years, legal publishers developed an intricate set of printed materials that controlled the flow of legal information. Most of this apparatus was built around cases. Elaborate systems of reporting, digesting, tracing, and evaluating cases developed. Until very recently, mastering these systems was the essence of learning legal research. The lawyer graduating from law school in 1975 had to know much more than someone who graduated in 1875, because the use of traditional paper-based, case-centered tools had grown more complex. But it was still a system built on the old paradigm of the paper-information world. This old-style research is the only kind of research that some senior lawyers, judges, and law professors accept as legitimate. That will change in the course of the next generation, but it hasn’t yet changed completely. Meanwhile, the new world of legal research is rooted in electronic information. In the past 30 years, the variety of electronic databases has grown, and the information that they store, as well as the search methods for using them, have improved enormously. Even the Internet carries a wide range of legal information. The modern researcher must know how to retrieve these modern tools.

Intermediate

In published legal writing, find a four-page passage with strong topic sentences. Underline them. If you’re part of a writing group or class, bring copies of your work to the next meeting.

Advanced

In published legal writing, find a four-page passage with weak topic sentences. Edit the passage to strengthen them. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy of both the original and the edited version to your colleagues.

Despite the topic sentence’s importance in announcing the subject, its more important function is to provide a transition. That is, every paragraph opener should contain a transitional word or phrase to ease the reader’s way from one paragraph to the next. Readers will then immediately see whether the new paragraph amplifies what has preceded, contrasts with it, or follows it in some other way.

Almost invariably, a good paragraph opener establishes a connection by using one or two of these devices:

• Pointing words—that is, words like this, that, these, those, and the.

• Echo links—that is, words or phrases in which a previously mentioned idea reverberates.

• Explicit connectives—that is, words whose chief purpose is to supply transitions (such as also, further, therefore, and yet).

Strong writers use all three techniques to establish continuity from paragraph to paragraph. Let’s consider each one to see how they together work in context.

Pointing words—especially this and that—refer directly to something already mentioned. They point to an antecedent. If you first talk about land at 2911 Maple Avenue, and then you refer to that property, the word that points to the preceding reference. It establishes an unambiguous connection.

Pointing words often work in tandem with echo links. In fact, the word property—in the phrase that property—is an echo of 2911 Maple Avenue. It’s a different word in which the earlier reference reverberates. Imagine a friend of yours saying that courts imprison too many people and thereby aggravate social problems, the ultimate result being greater levels of violence. You respond by saying, “That argument is fallacious for three reasons.” The phrase that argument is a pointing word plus an echo link. You’re off to a great start: now good luck in supplying the three reasons you’ve so deftly introduced.

Finally, there are explicit connectives. You won’t be able to write well without them. Although some writers have a bias against explicit connectives—and they can indeed be overdone—professional writers find them indispensable. They typically clarify the relationship between two sentences. What follows is a handy list of some of the best ones. Photocopy it, tape it to a card, and prop it up by your computer or legal pad. Besides reminding you of the need for transitions, it will supply you with a generous range of options.

• When adding a point: and, also, in addition, besides, what is more, similarly, nor, along with, likewise, too, moreover, further

• When giving an example: for instance, for example, as one example, to cite but one example, for one thing, for another thing, likewise, another

• When contrasting: but, yet, instead, however, on the one hand, on the other hand, still, nevertheless, nonetheless, conversely, on the contrary, whereas, in contrast to, unfortunately

• When comparing: similarly, likewise, in the same way

• When restating: in other words, that is, this means, in simpler terms, in short, put differently, again

• When introducing a cause: because, since, when

• When introducing a result: so, as a result, thus, therefore, accordingly, then, hence

• When conceding or qualifying: granted, of course, to be sure, admittedly, though, even though, even if, only if, true, while, naturally, in some cases, occasionally, if, while it might be argued that, despite

• When pressing a point: in fact, as a matter of fact, indeed, of course, without exception, still, even so, anyway, the fact remains, assuredly

• When explaining a sentence: that is, then, earlier, previously, meanwhile, simultaneously, now, immediately, at once, until now, soon, no sooner, that being so, afterward, later, eventually, in the future, at last, finally, in the end

• When summing up: to summarize, to sum up, to conclude, in conclusion, in short, in brief, so, and so, consequently, therefore, all in all

• When sequencing ideas: First, . . . Second, . . . Third, . . . Finally, . . .

In creating bridges, Judge Richard Posner often uses explicit connectives. But in the passage on page 84, from The Problems of Jurisprudence (1990), he uses a pointing word and an echo link (This account), another pointing word plus an echo (This need), an echo (spirit of pragmatism), and an explicit connective (Latterly) followed by an echo (pragmatism).

A good writer generally combines all the methods for bridging. On page 85 is an example from A Matter of Principle (1985) by Ronald Dworkin, in which he uses an explicit connective (But), another (But), a pointing word coupled with an echo (this suspicion), and two explicit connectives (the comparatives similar and more fundamental).

Try this exercise: take something you’ve written, look at the paragraph breaks, and see whether you can spot bridging words. Circle them. If you find that you’re bridging effectively in at least a third of the paragraphs, then you’ve already been (perhaps subconsciously) using this technique. Build on this strength—that is, start building bridges every time you make a new paragraph.

But if you find that you’re seldom including a bridge, that probably means you have some discontinuities in the text. You’re not writing with an unbroken train of thought—with a clean line. This technique should improve the structure of your writing even within paragraphs, where sentences must progress clause by clause. Yet the best test for effective bridging occurs in paragraph openers.

Exercises

Basic

The following sentences are consecutive paragraph openers from Lawrence Friedman’s Crime and Punishment in American History (1993). Identify the bridging words, as well as the bridging method (pointing word, echo link, explicit connective), in each paragraph opener, beginning with the second. Remember that each of these paragraph openers is followed by several other sentences in the paragraph. You’re not trying to link the sentences listed; rather, you’re trying to spot words in each paragraph opener that relate explicitly to what must have come at the end of the preceding paragraph.

1. The automobile made its first appearance on the streets, for all practical purposes, in the first decade of this century.

2. By 1940, the United States had become an automobile society.

3. The numbers have continued to rise, as automobiles choke the roads and highways, and millions of people, living in the land of suburban sprawl, use the automobile as their lifeline—connecting them to work, shopping, and the outside world in general.

4. Thus, a person who parks overtime and gets a “ticket” will get an order to appear in court and face the music.

5. In many localities, traffic matters got handled by municipal courts, police courts, justices of the peace, and sometimes specialized departments of a municipal court.

6. The traffic court judge, as one would expect, did not have the prestige and dignity of a higher-grade judge.

7. The root of this evil was, perhaps, the fact that defendants did not—and do not—see themselves as criminals, but rather as unlucky people who got caught breaking a rule that everybody breaks once in a while.

8. This attitude came to the surface in a 1958 American Bar Association report on traffic matters in Oklahoma.

Intermediate

In published legal writing, find an exemplary passage (four pages or so) illustrating good bridges. At the outset of each paragraph, box the bridging word or words. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy to each colleague, provide the full citation on each copy, and be prepared to discuss your findings.

Advanced

In published legal writing, find a passage (four pages or so) illustrating an absence of bridges. Either add a bridge where needed or else explain in the margin why the problem isn’t fixable by an editor. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy to each colleague, provide the full citation on each copy, and be prepared to discuss your findings.

Remember that the paragraph is the basic unit of thought. Have you ever done a word count for your paragraphs? If not, you might find it revealing. Strive for an average paragraph of no more than 150 words—preferably fewer—in three to eight sentences. It’s tempting to mandate a sentence count. The problem, of course, is that an average of six sentences could still be horrendous if the sentences were each 80 words long. So a word count is more reliable than a sentence count.

As with sentence length (see § 6), you need variety in paragraph length: some slender paragraphs and some fairly ample ones. But watch your average. And remember that there’s nothing wrong with an occasional one-sentence paragraph. The superstition to the contrary is a remnant of half-remembered grammar-school lessons.4

During the 20th century, paragraphs tended to get shorter. Although finding truly representative samples is a tricky matter, the following data—showing average numbers of words per paragraph in the works of noted 20th-and 21st-century legal writers—illustrate the trend:

Writer |

Average Words per Paragraph |

James Bradley Thayera (1900) |

655 |

Oliver Wendell Holmesb (1909) |

270 |

James Barr Amesc (1913) |

217 |

John Alderson Footed (1914) |

426 |

Charles Evans Hughese (1928) |

434 |

Harry D. Nimsf (1929) |

211 |

William F. Walshg (1930) |

286 |

Benjamin N. Cardozoh (1939) |

322 |

William L. Prosseri (1941) |

139 |

Samuel Willistonj (1948) |

189 |

Arthur L. Corbink (1952) |

116 |

Thomas E. Atkinsonl (1953) |

119 |

Karl N. Llewellynm (1960) |

151 |

Frederick Bernays Wienern (1967) |

127 |

Reed Dickersono (1975) |

95 |

Richard A. Posnerp (1977) |

153 |

Susan Estrichq (1987) |

118 |

George T. Bogertr (1987) |

85 |

Michael E. Tigars (1993) |

74 |

Karen Grossi (1997) |

116 |

Charles Alan Wrightu (1999) |

84 |

Douglas G. Bairdv (2001) |

117 |

Elizabeth Warren |

|

& Jay Lawrence Westbrookw (2009) |

97 |

Pity the poor readers of Thayer, Foote, and Hughes!

The sampling from Professor Wright’s celebrated treatise Federal Practice and Procedure5 illustrates the variety that adds interest and appeal. His longest paragraph contains 231 words. His shortest is a single sentence of 14 words.

Despite this powerful evidence, much contemporary legal writing contains massive paragraphs. An average of 250 words or more isn’t uncommon, especially in law reviews. But a high average count occurs in court papers as well, and this raises a special problem. If you double-space, as court rules require, then a 250-word paragraph will occupy 85–90% of the page. You’ll end up with about one paragraph per page. Double-spacing makes for an uninviting, blocklike density. The mere sight of it is enough to put off modern readers.

But if your average is under 150 words—or, better yet, under 100—the reader can come up for air more frequently. You’ll have an average of two or more paragraphs per page. Having some visual variety, the page will take on a more relaxed feel—whether you’re double-spacing or single-spacing.

Exercises

Basic

In published legal writing, find a three-or four-page example of aptly varied paragraph lengths. Identify something specific that you like about the passage. If you belong to a writing group or class, circulate a copy to each colleague and be prepared to discuss your example.

Intermediate

Break down each of the following passages so that it contains three to five separate paragraphs. Find the best places for starting new paragraphs.

• When the courts of equity created the equity of redemption, they ignored the parties’ explicit intention. They allowed the mortgagor to regain the property by performing the secured obligation after the legal title to the property had vested absolutely in the mortgagee. This vesting took place according to both the parties’ express language in the mortgage deed and the effect that the law courts gave the language. After their original intervention, equity courts developed the doctrine prohibiting the clogging of the mortgagor’s equity of redemption. Under this doctrine, even though the mortgage is in default, no agreement contained in the mortgage can cut off a recalcitrant mortgagor’s equity of redemption without the resort to foreclosure by the mortgagee. Courts won’t enforce a mortgagee’s attempts to have the mortgagor waive the right to be foreclosed in the event of a default. The prohibition against clogging has been characterized by a variety of labels. The most common characterization associated with the doctrine in the United States is “once a mortgage, always a mortgage.” This is only another way of saying that a mortgage can’t be made irredeemable. The clogging doctrine, as a corollary of the equity of redemption, prevented evasion by ingenious and determined mortgagees. These mortgagees had tried using many types of clauses that, while recognizing the existence of the equity of redemption, nullified or restricted its practical operation.

• Before an intelligent study of criminal law can be undertaken, it is necessary to focus on the single characteristic that differentiates it from civil law. This characteristic is punishment. Generally, in a civil suit, the basic questions are (1) how much, if at all, defendant has injured plaintiff, and (2) what remedy or remedies, if any, are appropriate to compensate plaintiff for his loss. In a criminal case, on the other hand, the questions are (1) to what extent, if at all, defendant has injured society, and (2) what sentence, if any, is necessary to punish defendant for his transgressions. Since the criminal law seeks to punish rather than to compensate, there should be something about each course of conduct defined as criminal that renders mere compensation to the victim inadequate. This follows from the truism that no human being should be made to suffer if such suffering cannot be justified by a concomitant gain to society. No rational assessment of the kinds of activity that should be punished can be undertaken without some analysis of the purposes of punishment. Those purposes most frequently mentioned are reformation, restraint, retribution, and deterrence.

• Declaratory remedies furnish an authoritative and reliable statement of the parties’ rights. Other remedies may be added if necessary, but the declaratory remedy itself makes no award of damages, restitution, or injunction. The chief problem in obtaining declaratory relief lies in the rules of justiciability—rules that courts will not issue advisory opinions, decide moot cases or those that are not ripe, or deal in any dispute that does not count as a case or controversy. Although people might settle legal arguments between themselves by going to the law library or calling the librarian, they cannot call on the courts this way. These concerns grow out of procedural and process values. They involve what we think about the nature of courts and judicial work. Before declaratory-judgment statutes were enacted, plaintiffs obtained relief that was sometimes essentially declaratory by suing for injunctive relief, or to quiet title to land, or to rescind a contract. When the declaratory judgment performs an analogous function, the case is justiciable and such relief is appropriate. Yet it is not possible to describe adequately all the instances in which these concerns will prevent declaratory relief. This type of relief is often useful in contract disputes. A good example is the dispute over liability-insurance coverage. The insured tortfeasor, the insurer, and the injured victim all need to know whether insurance covers the claim. When the insurer insists that it does not cover the claim and the others insist that it does, declaratory judgment is a good resolution.

Advanced

In published legal writing, find an example of grossly overlong paragraphs. Suggest the natural points for additional paragraph breaks. If you belong to a writing group or class, circulate a copy with your paragraph markings to each colleague.

Headings (see § 4) are signposts, of course, but you’ll also need textual signposts in all but the most elementary writing. If there are three issues you’re going to discuss, state them explicitly on page one. If there are four advantages to your recommended course of action, say so when introducing the list. And be specific: don’t say that there are “several” advantages. If there are four, say so. This greater level of specificity shows that you’ve thought through the problem.

Consider the following paragraph:

Although stock-appreciation rights, including alternative settlements, can solve substantial problems encountered by corporate officers in realizing the value of their stock options, this solution also imposes costs on the corporation. Most obviously, alternative settlements result in a cash outflow from the corporation rather than the cash inflow that results from the exercise of an option. Alternative settlements also result in charges to corporate earnings—charges not required for ordinary stock options. All that is required for ordinary stock options is a disclosure of the options and balance-sheet charges against retained earnings when they are exercised.

That paragraph is difficult to wade through—unnecessarily so. Consider how helpful some simple signposts are (in boldface here only for pedagogical purposes):

Although stock-appreciation rights, including alternative settlements, can solve substantial problems encountered by corporate officers in realizing the value of their stock options, this solution also imposes costs on the corporation in two ways. First, alternative settlements result in a cash outflow from the corporation rather than the cash inflow that results from the exercise of an option. Second, alternative settlements result in charges to corporate earnings—charges not required for ordinary stock options. All that is required for ordinary stock options is a disclosure of the options and balance-sheet charges against retained earnings when they are exercised.

Adding five words makes quite a difference. Three other words got deleted—so the net increase was only two.

Take another example. Most readers will find it unsettling to read, at the bottom of page one, “The examiner’s reasoning was flawed”—followed by a long paragraph introduced by the words “In the first place . . . .” Of the two most obvious cures, the better one would be to write, “The examiner’s reasoning was flawed for three reasons’—followed by a bulleted list (see § 43) succinctly introducing those reasons before you embark on a full explanation. The second-best cure would be to omit the bulleted list while mentioning that there are three reasons. But merely to refer vaguely to “several reasons” isn’t really a cure at all. Phrases like that one often induce anxiety. How many reasons are there, after all?

Good signposts are especially important when the writing is double-spaced. In single-spaced text the paragraphs tend to be compact, but in double-spaced text the related sentences are more spread out. Page breaks come more frequently. And because much legal writing has to be double-spaced (as with briefs), signposts take on a special significance.

Exercises

Basic

Find a piece of published legal writing—such as a book chapter, a judicial opinion, or a law-review article—in which the writer uses signposts effectively. Photocopy a section that illustrates the signposts and highlight them. If you’re part of a writing group or class, bring a highlighted copy to each colleague.

Intermediate

Find a piece of published legal writing—such as a book chapter, a judicial opinion, or a law-review article—in which the writer omits signposts where they’re needed. Photocopy a section that illustrates the lack of signposts, and then edit the page by hand to supply them. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy to each colleague.

Advanced

One of your coworkers, in a hurry to leave for a two-week vacation, has come to you for help with a memo that needs to go out immediately. She leaves it with you. Although you don’t know much about the subject—and don’t know Ezra Bander, the recipient—do your best to rewrite the memo to clarify how many items your colleague is attaching.

To: Ezra Bander

From: [Your colleague’s name]

Subject: Group Annuity Policies

Date: March 15, 2011

Attached are two photocopies of the policy files for five of the six group annuity contracts the NY examiners selected for further review. To be as responsive as possible to the examiners’ request, we have attached the applicable Administration section’s complete file to each client relating to the contracts in question (other than FSR (GA-8192)). For FSR we have attached the Contract section’s correspondence file since it is the most complete source of client information. Please note that for the GIC files (on page 1 of the list attached to your request), we consider certain pricing information to be proprietary and confidential. Therefore, we have added a Request for Confidential Treatment to the applicable portions of these files. We discovered that the jurisdiction for one of the contracts the examiners selected (GA-8180 Purgon) is actually Massachusetts. Please let us know if there is another contract you want to review. Due to the complexity of the SBCD Communications file, we created a timeline to facilitate the examiners’ review (which was created solely to help the examiners follow the file). We are unable to send the original policy files since we have ongoing relationships with these clients. However, we have certified to NY (see attachment) that we have copied the files they requested. Also, attached to each of the five files are all related state filing materials, including any prefilings under Circular Letter 64-1, the submission packages to the Dept. of forms, any correspondence with the Dept., and approvals from the Dept. if received. The files have been reviewed by the business area and appropriate legal counsel.

If you have any questions, please call me.

Do you remember when you first started reading law? You were probably reading a judicial opinion, and surely among the most irksome things about the experience was encountering all the citations in the text. For beginning legal readers, the prose is quite jarring—as if you were driving down a highway filled with speed bumps.

These thought-interrupters were born of a technologically impoverished world. Originally, lawyers used scriveners who interspersed authorities in their writings. Then, in the 1880s, typewriters became popular, and it was all but impossible to put citations in footnotes. That’s why citations have traditionally appeared in the text. They were there in 1800, they were there in 1900, and they were still there in 1975. It had become a hardened convention.

Meanwhile, of course, the number of cases being cited in legal writing skyrocketed during the years leading up to 1975. And by the turn of the 21st century, things had gotten even worse. With computer research and the proliferation of case law, it has become easier than ever to find several cases to support virtually every sentence.

So over time, the pages of judicial opinions, briefs, and memos have become increasingly cluttered. Some have become unreadable. Others can be read only by those mentally and emotionally intrepid enough to cut through the underbrush.

If citations plague readers, though, they plague writers every bit as much. When you put citations within and between sentences, it’s hard to come up with shapely paragraphs. The connections between consecutive sentences get weaker. Even worse, legal writers often intend a single sentence, followed by a string citation with parentheticals, to stand for a paragraph. After all, it fills up a third or even half of the page. How would such a paragraph fare with a high-school composition teacher? It would flunk.

In short, it doesn’t really matter whether readers can negotiate their way through eddies of citations—because, on the whole, writers can’t.

Reference notes can cure these ills. That is, put citations—and generally only citations—in footnotes. And write in such a way that no reader would ever have to look at your footnotes to know what important authorities you’re relying on. If you’re quoting an opinion, you should—in the text—name the court you’re quoting, the year in which it wrote, and (if necessary) the name of the case. Those things should be part of your story line. Just get the numbers (that is, the volume, reporter, and page references) out of the way.

If footnoting your citations seems like such a revolutionary idea, ask yourself why you’ve never seen a biography that reads like this:

Holmes was ready for the final charge. His intellectual powers intact (Interview by Felix Frankfurter with Harold Laski, 23 Mar. 1938, at 45, unpublished manuscript on file with the author), he organized his work efficiently so that little time was wasted (3 Holmes Diary at 275, Langdell Law Library Manuscript No. 123-44-337; Holmes letter to Isabel Curtain, 24 June 1923, Langdell Law Library Manuscript No. 123-44-599). He volunteered less often to relieve others of their caseload (Holmes court memo, 24 July 1923, at 4, Library of Congress Rare Book Room Doc. No. 1923-AAC-Holmes-494), and he sometimes had to be reassured of his usefulness (Brandeis letter to Felix Frankfurter, 3 Mar. 1923, Brandeis Univ. Manuscript Collection Doc. No. 23-03-3-BF). His doctor gave him a clean bill of health (Mass. Archives Doc. No. 23-47899-32, at 1), told him his heart was “a good pump” (Holmes letter to Letitia Fontaine, 25 June 1923, at 2, Langdell Law Library Manuscript No. 123-44-651), and told him that very few men of Holmes’s age were “as well off as he was” (id.)—to which Holmes drily replied that “most of them are dead” (Memo of Dr. Theobald Marmor, 26 June 1923, at 2, Morgan Library Collection, copy on file with the author). But he was pleased that the “main machinery” was “in good running order” (Holmes letter to Letitia Fontaine, 25 June 1923, at 1, Langdell Law Library Manuscript No. 123-44-651), and he frequently felt perky enough to get out of the carriage partway home from court and walk the remaining blocks with Brandeis (Brandeis letter to Clare Eustacia Bodnar, 22 July 1923, Brandeis Univ. Manuscript Collection Doc. No. 23-7-22-BCEBB).

No self-respecting historian would write that way. But brief writers commonly do something very much like it:

Agency decisions are entitled to the greatest weight and to a presumption of validity, when the decision is viewed in the light most favorable to the agency. Baltimore Lutheran High Sch. Ass’n v. Employment Security Admin., 302 Md. 649, 662–63, 490 A.2d 701, 708 (1985); Board of Educ. of Montgomery County v. Paynter, 303 Md. 22, 40, 491 A.2d 1186, 1195 (1985); Nationwide Mut. Ins. Co. v. Insurance Comm’r, 67 Md. App. 727, 737, 509 A.2d 719, 724, cert. denied, 307 Md. 433, 514 A.2d 1211 (1986); Bulluck v. Pelham Wood Apartments, 283 Md. 505, 513, 390 A.2d 1119, 1124 (1978). Thus, the reviewing court will not substitute its judgment for that of the agency when the issue is fairly debatable and the record contains substantial evidence to support the administrative decision. Howard County v. Dorsey, 45 Md. App. 692, 700, 416 A.2d 23, 27 (Md. Ct. Spec. App. 1980); Mayor and Aldermen of City of Annapolis v. Annapolis Waterfront Co., 284 Md. 383, 395–96, 396 A.2d 1080, 1087–88 (1979); Cason v. Board of County Comm’rs for Prince George’s County, 261 Md. 699, 707, 276 A.2d 661, 665 (1971); Germenko v. County Board of Appeals of Baltimore County, 257 Md. 706, 711, 264 A.2d 825, 828 (1970); Bonnie View Country Club, Inc. v. Glass, 242 Md. 46, 52, 217 A.2d 647, 651 (1966). The court may substitute its judgment only as to an error made on an issue of law. State Election Board v. Billhimer, 314 Md. 46, 59, 548 A.2d 819, 826 (1988), cert. denied, 490 U.S. 1007, 109 S.Ct. 1644, 104 L.Ed.2d 159 (1989); Gray v. Anne Arundel County, 73 Md. App. 301, 308, 533 A.2d 1325, 1329 (Md. Ct. Spec. App. 1987).

That’s a fairly serious example of excessive citations, but it’s actually mild compared with what writers do when coupling parentheticals with the citations. Even if you have fewer citations, the reading becomes significantly worse because it’s harder to know what you need to read and what you can skip:

To state a claim under Rule 10b-5, a complaint must allege that the defendant falsely represented or omitted to disclose a material fact in connection with the purchase or sale of a security with the intent to deceive or defraud. See Ernst & Ernst v. Hochfelder, 425 U.S. 185, 96 S.Ct. 1375, 47 L.Ed.2d 668 (1976). A party’s specific promise to perform a particular act in the future, while secretly intending not to perform that act or knowing that the act could not be carried out, may violate § 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 if the promise is part of the consideration for the transfer of securities. See, e.g., Luce v. Edelstein, 802 F.2d 49, 55 (2d Cir. 1986) (citing McGrath v. Zenith Radio Corp., 651 F.2d 458 (7th Cir.), cert. denied, 454 U.S. 835, 102 S.Ct. 136, 70 L.Ed.2d 114 (1981)); Wilsmann v. Upjohn Co., 775 F.2d 713, 719 (6th Cir. 1985) (concluding that plaintiff’s securities-fraud claim against acquiring corporation was in connection with defendant’s purchase of plaintiff’s stock where plaintiff alleged that part of consideration for sale of stock was false promise by acquiring corporation concerning future payments for stock plaintiff received in acquired corporation but holding that evidence of fraud was insufficient to support jury’s verdict), cert. denied, 476 U.S. 1171, 106 S.Ct. 2893, 90 L.Ed.2d 980 (1986). But see Hunt v. Robinson, 852 F.2d 786, 787 (4th Cir. 1988) (holding that defendant’s failure to tender shares in new company in return for plaintiff’s employment did not state securities-fraud claim because the defendant’s alleged misrepresentation concerned its tender of shares as required by the terms of the employment contract, not the actual sale of stock). The failure to perform a promise, however, does not constitute fraud if the promise was made with the good-faith expectation that it would be performed. See Luce, 802 F.2d at 56.

By the way, double-spacing aggravates this problem in a virulent way (see § 42).

Even if you strip out the citations, something the careful reader will have to do anyway (by mental contortion), you end up with unimpressive, wooden prose:

To state a claim under Rule 10b-5, a complaint must allege that the defendant falsely represented or omitted to disclose a material fact in connection with the purchase or sale of a security with the intent to deceive or defraud. A party’s specific promise to perform a particular act in the future, while secretly intending not to perform that act or knowing that the act could not be carried out, may violate § 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 if the promise is part of the consideration for the transfer of securities. The failure to perform a promise, however, does not constitute fraud if the promise was made with the good-faith expectation that it would be performed.

Now it’s possible to see what you’re actually saying. You can more easily focus on style. So you edit the paragraph. Now it reads well:

To state a claim under Rule 10b-5, a complaint must allege that the defendant—intending to deceive or defraud—falsely represented or failed to disclose a material fact about the purchase or sale of a security. A party’s specific promise to do something in the future, while secretly intending not to do it or knowing that it can’t be done, may violate Rule 10b-5 if the promise is part of the consideration for the transfer. But not performing the promise isn’t fraud if the promisor expected in good faith to be able to perform.

The revised passage isn’t a work of art. But it’s much closer than the original—and probably as artful as most discussions of Rule 10b-5 ever could be.

Go back and look at the original 10b-5 passage. Look at how much more difficult it is to tease out the essential ideas. In your imagination try doublespacing it, so that you fill up the entire page. Now imagine page after page of this. You get the idea.

In sum, if you put citations into footnotes, while still naming in the text the important authorities you’re relying on, your prose will improve. Here are ten advantages to using citational footnotes:

1. You’re able to strip down an argument and focus on what you’re saying.

2. You’re able to write better, more fully developed paragraphs.

3. Meanwhile, your paragraphs will be significantly shorter than they would be with the citations in the text.

4. You’re able to connect your sentences smoothly, with simple transitional words. When citations appear between sentences, writers tend to repeat several words that aren’t necessary once the sentences are put together without citational interruptions.

5. You’re able to use greater variety in sentence patterns, especially by sometimes using subordinate clauses.

6. You can’t camouflage poor writing—or poor thinking—in a flurry of citations. And you won’t be tempted to bury important parts of your analysis in parentheticals.

7. The long-decried string citation becomes relatively harmless. (I don’t favor string citations, but I’m not adamantly opposed to them either—not if they’re out of the way.)

8. You’ll find it necessary to discuss important cases contextually, as opposed to merely relying on citations without ever discussing the cases you cite. You’ll pay more respect to important precedent by actually discussing it instead of simply identifying it in a “citation sentence,” which isn’t really a sentence at all.

9. You give emphasis where it’s due. That is, the court and the case and the holding are often what matters (“Three years ago in Gandy, this Court held . . .”), but the numbers in a citation never are (“925 S.W.2d 696, 698”—etc.). Numbers, when sprinkled through the main text, tend to distract.

10. Your pages end up looking significantly cleaner.

Many brief-writers and many judges have been persuaded by these points. They’ve begun using citational footnotes because they want to be better writers.

Seemingly the only argument against footnoting citations is the odd accusation that doing so diminishes the importance of precedent. No one ever leveled this accusation against Judge John Minor Wisdom or Judge Alvin Rubin, two highly respected Fifth Circuit judges who, from about 1983 to the end of their careers, footnoted all their citations. As Judge Wisdom put it in a 1993 article: “Citations belong in a footnote: even one full citation such as 494 U.S. 407, 110 S. Ct. 1212, 108 L. Ed. 2d 347 (1990), breaks the thought; two, three, or more in one massive paragraph are an abomination.”6

Until the advent of personal computers in the 1980s, law offices had no choice. Citations had to go into the text. Only professional printers had a realistic option of footnoting citations. The computer has liberated us from this technological constraint.

Within a generation, the citational footnote may well be the norm in both judicial opinions and briefs. It will probably come to be viewed as one of the greatest improvements in legal writing.

Exercises

Basic

Look up (in hard copy, if possible) at least three cases listed below, all of which put citations in footnotes. Identify the stylistic differences you notice between these cases and other cases (in the same volume) having citations in the text.

• Alizadeh v. Safeway Stores, Inc., 802 F.2d 111 (5th Cir. 1986).

• Alamo Rent A Car, Inc. v. Schulman, 897 P.2d 405 (Wash. Ct. App. 1995).

• Warden v. Hoar Constr. Co., 507 S.E.2d 428 (Ga. 1998).

• M.P.M. Enters., Inc. v. Gilbert, 731 A.2d 790 (Del. 1999).

• Aleck v. Delvo Plastics, Inc., 972 P.2d 988 (Alaska 1999).

• State v. Martin, 975 P.2d 1020 (Wash. 1999) (en banc).

• In re Nolo Press/Folk Law, Inc., 991 S.W.2d 768 (Tex. 1999).

• Williams v. Kimes, 996 S.W.2d 43 (Mo. 1999) (en banc).

• United States v. Parsee, 178 F.3d 374 (5th Cir. 1999).

• McGray Constr. Co. v. Director, Office of Workers’ Comp. Programs, 181 F.3d 1008 (9th Cir. 1999).

• Minneapolis Public Hous. Auth. v. Lor, 591 N.W.2d 700 (Minn. 1999).

• Kohlbrand v. Ranieri, 823 N.E.2d 76 (Ohio Ct. App. 2005).

• McHenry v. State, 820 N.E.2d 124 (Ind. 2005).

• Admiral Ins. Co. v. Abshire, 574 F.3d 267 (5th Cir. 2009).

• Romain v. Frankenmuth Mut. Ins. Co., 762 N.W.2d 911 (Mich. 2009).

• United States v. Zajac, 748 F.Supp.2d 1340 (D. Utah 2010).

• Wolters v. Lakey, 456 B.R. 687 (D. Kan. 2011).

• Howard v. Howard, 336 S.W.3d 433 (Ky. 2011).

• Donatelli v. D.R. Strong Consulting Eng’rs, Inc., 261 P.3d 664 (Wash. Ct. App. 2011).

• In re Woods, 465 B.R. 196 (B.A.P. 10th Cir. 2012).

• Blockbuster Investors LP v. Cox Enters., Inc., 724 S.E.2d 813 (Ga. Ct. App. 2012).

Intermediate

Rewrite the following passages to put all citations in footnotes and otherwise improve the style:

• Having initially remanded the question of attorney’s fees to the Circuit Court following its decision in Greenwald Cassell Assocs., Inc. v. Department of Commerce, 15 Va. App. 236, 421 S.E.2d 903 (1992), the Court of Appeals’ subsequent review of that remand in Greenwald Cassell Assocs., Inc. v. Guffey, 19 Va. App. 179, 450 S.E.2d 181 (1994) provides an ample basis to determine the appropriateness and thoroughness of the appellate review conducted.

• In certain narrow exceptions, a court may consider patents and publications issued after the filing date. In re Koller, 613 F.2d 819, 824 (C.C.P.A. 1980). For example, in deciding an appeal from the denial of an application, the Federal Circuit relied upon an article published in 1988, five years after an application’s filing date, to conclude that the level of skill in the art in 1983 was not sufficiently developed to enable a scientist to practice the invention claimed. In re Wright, 999 F.2d 1557, 1562 (Fed. Cir. 1993). Similarly, in Gould v. Quigg, 822 F.2d 1074 (Fed. Cir. 1987), the same court upheld a decision to permit the testimony of an expert who relied on a subsequent publication to opine on the state of the art as of the applicant’s filing date. Id. at 1079. The publication was not offered to supplement the knowledge of one skilled in the art at the time to render it enabling. Id. In addition, later publications have been used by the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals numerous times as evidence that, as of the filing date, a parameter absent from the claims was or was not critical, Application of Rainer, 305 F.2d 505, 507 n.3 (C.C.P.A. 1962), that a specification was inaccurate, Application of Marzocchi, 439 F.2d 220, 223 n.4 (C.C.P.A. 1971), that the invention was inoperative or lacked utility, Application of Langer, 503 F.2d 1380, 1391 (C.C.P.A. 1974), that a claim was indefinite, Application of Glass, 492 F.2d 1228, 1232 n.6 (C.C.P.A. 1974), and that characteristics of prior-art products were known, Application of Wilson, 311 F.2d 266 (C.C.P.A. 1962). Nonetheless, none of these exceptions “established a precedent for permitting use of a later existing state of the art in determining enablement under 35 U.S.C. § 112.” Koller, 613 F.2d at 824 n.5.

Advanced

Rewrite the following passage, putting all citations in footnotes. Improve the flow of the text. Decide what case names you might want to weave into your narrative—and how you can best accomplish this.

III. Attorney’s Fees

In reality, Ohio law is in conflict as to whether attorney’s fees may be claimed as compensatory damages (which would provide the foundation for punitive damages). Of course, Ohio law has long permitted recovery of attorney’s fees, even in the absence of statutory authorization, where punitive damages are proper and first awarded. Roberts v. Mason, 10 Ohio St. 277 (1859); Columbus Finance, Inc. v. Howard, 42 Ohio St. 2d 178, 183, 327 N.E.2d 654, 658 (1975); Zoppo v. Homestead Ins. Co., 71 Ohio St. 3d 552, 558, 644 N.E.2d 397, 402 (1994). However, the important question for our purposes is whether obtaining punitive damages is the only way in which to recover attorney’s fees, or if attorney’s fees can be recovered “before” punitive damages and used as the requisite compensatory foundation (actual damages) necessary for recovery of punitive damages.

Several cases hold that attorney’s fees cannot be recovered unless punitive damages are first awarded. See Olbrich v. Shelby Mut. Ins. Co., 469 N.E.2d 892 (Ohio App. 1983); Ali v. Jefferson Ins. Co., 5 Ohio App. 3d 105, 449 N.E.2d 495 (1982); Stuart v. Nat’l Indemn. Co., 7 Ohio App. 3d 63, 454 N.E.2d 158 (1982); Convention Center Inn v. Dow Chemical Co., 484 N.E.2d 764 (Ohio Com. Pl. 1984). However, a close reading of the Ohio Supreme Court’s decision in Zoppo suggests that such a requirement might not be necessary:

Attorney fees may be awarded as an element of compensatory damages where the jury finds that punitive damages are warranted. Columbus Finance, Inc. v. Howard, 42 Ohio St. 2d 178, 183, 327 N.E.2d 654, 658 (1975).

Zoppo, 71 Ohio St. 3d at 558.

Furthermore, in the earlier decisions of Spadafore v. Blue Shield, 21 Ohio App. 3d 201 (1985), an Ohio appellate court held that damages “flowing from” bad faith conduct may include:

lost time at work and . . . mileage and other travel costs due to the additional [testimonial] examination which was held out of town. . . . An obvious loss to [the plaintiff] was the cost of the lawsuit to enable recovery of his claim. . . .

Id. at 204. Other courts have alluded to the possibility of litigation expenses and/or attorney’s fees as compensatory damages. See, e.g., LeForge v. Nationwide Mut. Ins. Co., 82 Ohio App. 3d 692 (1992) (“reasonable compensation for the . . . inconvenience caused by the denial of the insurance benefits”); Eastham v. Nationwide Mut. Ins. Co., 66 Ohio App. 3d 843 (1990) (“evidence of . . . costs in this case, including expenses incurred in collecting (on the coverage) attorney fees, lost interest . . .”); Motorists Mut. Ins. Co. v. Said, 63 Ohio St. 3d 690, 703–04 (1992) (Douglas, J., dissenting) (“litigation expenses are primary compensatory damages in bad faith claim”) (overruled in part by the Zoppo decision).

Moreover, in Motorists Mut. Ins. Co. v. Brandenburg, 72 Ohio St. 3d 157, 648 N.E.2d 488 (1995), the Ohio Supreme Court upheld a trial court’s award of attorney’s fees to the insureds who were forced to defend their right to coverage (against the insurance company) in a declaratory judgment action. The court acknowledged the “anomalous result” that might arise when an insured is required to defend his/her right to recover under an insurance policy, but cannot recover the damages incurred thereby. Id. at 160.

Because our legal system relies on precedent, legal writers quote with great frequency. We quote from statutes, cases, treatises, law reviews, and dictionaries. We quote from depositions and from live testimony. Yet most legal writers quote poorly, and many if not most of their readers skip the quotations.

Novices sometimes drop into the text direct quotations without any lead-in at all. They pepper their discussions with others’ language, seemingly to avoid thinking about or coping with the problem of paraphrasing what someone else has said. Their style is disjointed and distracting.

A step beyond the novice is the intermediate writer who tries to incorporate quotations with stereotyped lead-ins such as these:

• The statute reads in pertinent part:

• The court stated as follows:

• According to Federal Practice and Procedure:

• As one noted authority has explained:

• Black’s Law Dictionary states:

• The witness testified to the following facts:

These phrases are deadly. They’re enough to kill a good quotation.

Then what, you may ask, are you to do? After all, those are the standard quotation introducers. The answer is that you should tailor the lead-in to the quotation. Say something specific. Assert something. Then let the quotation support what you’ve said. Good lead-ins resemble these:

• The statute specifies three conditions that a trustee must satisfy to be fully indemnified:

• Because the plaintiff had not proved damages beyond those for breach of contract, the court held that the tort claim should have been dismissed:

• In fact, as the court noted, not all written contracts have to be signed by both parties:

• The Central Airlines court recognized that the facts before it involved a lawyer who neither willfully nor negligently misled the opposing party:

• The power to zone is a state power that has been statutorily delegated to the cities:

• The court found that Nebraska’s export laws are stricter than its in-state regulations:

By the way, is it acceptable to put a colon after a complete sentence? You bet.7 More writers ought to be doing it.