What’s the first thing a prospective employer notices about a résumé? Its overall appearance. And first impressions matter.

But document design is about much more than first impressions: it’s about third and fourth impressions. After all, your reader may spend many hours with your work. If you know how to produce readable pages, you’ll minimize readers’ headaches and maximize the effortless retrieval of information.

So you must learn something about typography and page layout. Although lawyers formerly didn’t have to trouble themselves with these things—because the options were severely limited in the days of typewriters—times have changed. Ignore document design at your peril. Although many judges, colleagues, and clients use some form of e-reader, you’re wise to assume the primacy of print and to assume that it matters how your document will look if someone prints it.

There’s a lot more to learn about typography than most lawyers realize. Or want to realize. When someone starts talking about margins and white space and serifed typefaces, most lawyers tune out. And they tend to resent court rules containing specifications about type.1

Yet these matters are anything but trivial. As magazine and book publishers well know, design is critical to a publication’s success. Of course, it won’t make up for poor content. But poor design can certainly mar good content.

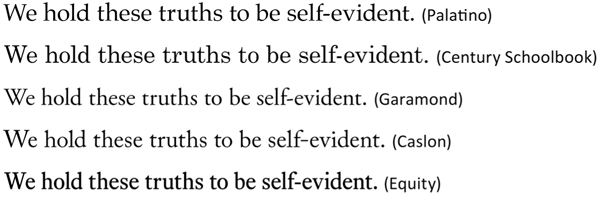

This is no time to get technical, so we’ll keep it simple: use a readable serifed typeface that resembles what you routinely see in good magazines and books. (A serifed typeface is one that has small finishing strokes jutting from the ends of each character.) Here are some examples of various serifed typefaces that will serve you and your documents well:

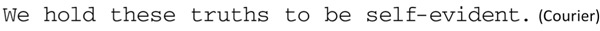

What you’ll especially want to avoid is the traditional typeface for typewriters: Courier. It’s blocklike and rather crude-looking:

You won’t find it in magazines or books. After all, no publisher would want to present such an unpolished look.

Basic

Find three sets of court rules that specify different typefaces or point size. Analyze the differences among them. If you’re part of a writing group or class, be prepared to report your findings and to discuss which rule might result in more readable court papers.

Intermediate

Find two regulations (state or federal) that contain typeface specifications. Summarize those specifications and their purpose. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a one-page summary to each colleague.

Advanced

Find two nonlegal sources that discuss which typefaces are most readable. Retype the most pertinent passages and provide citations. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy to each of your colleagues and be prepared to discuss the recommendations.

or

Find authority for the proposition that a sans-serif typeface is often best for headlines, while a serifed typeface is best for text.

To the modern eye, densely printed pages are a huge turnoff. Readers find them discouraging if not downright repellent. So you’ll need some methods to break up dense passages with white space. Many techniques discussed in this book contribute to white space, especially these:

• section headings (§ 4)

• frequent paragraphing (§ 26)

• footnoted citations (§ 28)

• set-off lists with hanging indents (§34)

• bullets (§ 43)

The white space around text is what makes a page look inviting and roomy. The lack of it makes the page look imposing and cramped.

By the way, which is easier for you to read: single-spaced or double-spaced text? Don’t be so quick with your answer. If you’re editing a manuscript, you’ll want the page double-spaced. But if you’re simply reading for comprehension, you probably won’t. That’s because double-spaced text has white space spread unmeaningfully throughout the page—between every two lines of type.

And there are three other disadvantages to double-spacing: (1) the document will be twice as long; (2) you’ll encounter paragraphs and headings less frequently; and (3) you’ll find it somewhat harder to figure out the document’s structure. Book and magazine publishers know these things: when they produce polished, readable prose that is single-spaced, it’s not necessarily because they’re environmentalists.

Although court rules often require that lawyers’ filings be double-spaced, you’re generally better off single-spacing when you can—as in letters and memos. Just be sure that you create meaningful white space in the margins, between paragraphs, and between items in set-off lists.

What about the white space after a period? Should there be one forward-space or two? The answer may surprise you (as it surprised me, initially): all the reputable authorities mandate one space after a period:

• “The typewriter tradition of separating sentences with two word spaces has no place in typesetting. The custom began because the characters of monospaced typefaces used on typewriters were so wide and so open that a single word space—one the same width as a character, including the period—was not wide enough to create a sufficient space between sentences. Proportionally spaced fonts, though, contain word spaces specifically designed to play the sentence-separating role perfectly. Because of this, a double word space at the end of a sentence creates an obvious hole in the line.” James Felici, The Complete Manual of Typography 80 (2003).

• “Put only one space, not two, following the terminal punctuation of a sentence.” Kate R. Turabian, A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations rule A.1.3 (7th ed. 2007).

• “Like most publishers, Chicago advises leaving a single character space, not two spaces, between sentences and after colons used within a sentence.” The Chicago Manual of Style rule 2.9 (16th ed. 2010).

• “I have no idea why so many writers resist the one-space rule. If you’re skeptical, pick up any book, newspaper, or magazine and tell me how many spaces there are between sentences.” Matthew Butterick, Typography for Lawyers 42 (2010).

For a detailed treatment of this point, see Matthew Butterick, Typography for Lawyers 41–44 (2010).

Basic

Find a legal document in which ample white space appears. If you’re part of a writing group or class, bring two or three photocopied pages for each colleague. Be prepared to discuss whether you think the writer used white space well or poorly, and why.

Intermediate

Find a legal document with insufficient white space. If you’re part of a group or class, circulate a copy of the two most cramped-looking pages to each colleague. Be prepared to speculate on why the pages look the way they do.

Advanced

Redesign the pages that you found for the intermediate exercise.

When you want to highlight important items in a list, there’s hardly a better way than to use a series of bullet dots. They effectively take the reader’s eye from one point to the next.

Consider the following paragraph from a legal memo. It’s a midsize lump of sentences that buries the salient points:

The most advisable form of entity for organization of activities related to ProForm in the United States depends on the purposes for the entity, and especially on whether there are short-term or long-term plans for the national affiliates to be used as vehicles for directly profiting Mr. LaRoche or other investors and sports personalities involved. In order to definitively respond to this item, we would need more information as to the business plans in the United States. For example, what are the business objectives of the affiliate in the United States? How exactly will the organization obtain its financial resources? Will it actually have revenues, and if so from what sources? Are merchandise sales contemplated, or will the organization limit itself to providing services? To what extent will the entity actually organize and administer athletic events, as opposed to merely promoting the new sport? To what extent will educational activities or facilitating cultural exchanges be parts of the entity’s purposes? What other activities are planned?

But see what a bulleted list can do to make it snappier:

What organizational structure to devise for the sport in the United States depends on the business objectives that Mr. LaRoche envisions. Perhaps the chief question is: Does he have short-term or long-term plans for having the national affiliates directly profit himself or other investors and sports personalities? But to address even this question, we need more information about his business plans in the United States:

• What, specifically, are his business goals for the US affiliate?

• How will the entity be financed?

• Will it actually have revenues? If so, from what sources?

• Does Mr. LaRoche contemplate having the entity sell merchandise, or will he limit it to providing services?

• To what extent will the entity actually organize and administer athletic events as opposed to simply promoting the new sport?

• To what extent will educational activities, such as facilitating cultural exchanges, be part of the entity’s purposes?

• What other activities are planned?

That sort of listing is vital to readability and punchiness. Advertisers, journalists, and other professional writers use bullets. So should you.

Because the mechanics of bullets aren’t self-explanatory, here are several points—in bulleted fashion, of course—to keep in mind:

• Put a colon at the end of the sentence leading into the bulleted list. It serves as a tether for the bulleted items.

• Be sure to use “hanging” indents. That is, keep each bullet hanging out to the left, without any text directly underneath it.

• Adjust your tab settings so that you have only a short distance between the bullet dot and the first word. Normally, a quarter-inch is too much space—an eighth of an inch is about right.

• Make your items grammatically parallel (see § 8).

• Adopt a sensible convention for ending your items with semicolons or periods. (1) If each of your items consists of at least one complete sentence, capitalize the first word and put a period at the end of each item. (2) If each item consists of a phrase or clause, begin each item with a lowercase letter, put a semicolon at the end of all but the last item, and put a period at the end of the last. Place an and or an or after the last semicolon.

Exercises

Basic

Find one or more uses of bullets in the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure. Consider (1) why you think the drafters used bullets in those places but not elsewhere and (2) to what extent the presentation follows the guidelines given in this section.

Find and photocopy a court rule containing a page with a list that would benefit from bullets. Retype the passage to improve it.

Advanced

In the literature on effective writing, find two discussions of bullets. If you’re part of a writing group or class, be prepared to talk about what additional information you learned from those discussions.

In the old days, typists had chiefly two ways—rather crude ways—to emphasize text. They could underline, or else they could capitalize all the characters. Typewriters afforded extremely limited options. Although computers have given writers many better options—boldface, italic, boldface italic, variable point sizes, and bullet dots, to name a few—many legal writers are stuck in the old rut of all-caps text.

The problem with using all capitals is that individual characters lose their distinctive features: the strokes that go above and below a line of text. (Typographers call these strokes “ascenders” and “descenders.”) Capital letters, by contrast, are designed to be uniform in size. And when they come in battalions, the eye must strain a little—or a lot—to make out words and sentences. Modern readers think they scream:

THESE SECURITIES HAVE NOT BEEN APPROVED OR DISAPPROVED BY THE SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION OR ANY STATE SECURITIES COMMISSION NOR HAS THE SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION OR ANY STATE SECURITIES COMMISSION PASSED UPON THE ACCURACY OR ADEQUACY OF THIS PROSPECTUS SUPPLEMENT OR THE ACCOMPANYING PROSPECTUS. ANY REPRESENTATION TO THE CONTRARY IS A CRIMINAL OFFENSE.

Even if you change to initial capitals, you can’t say there’s much improvement in readability. Initial caps create visual hiccups:

These Securities Have Not Been Approved or Disapproved by the Securities and Exchange Commission or Any State Securities Commission Nor Has the Securities and Exchange Commission or Any State Securities Commission Passed upon the Accuracy or Adequacy of This Prospectus Supplement or the Accompanying Prospectus. Any Representation to the Contrary Is a Criminal Offense.

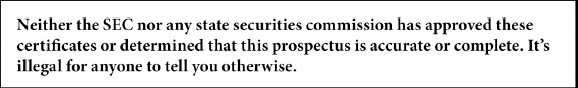

You’d be better off using ordinary boldface type:

Neither the SEC nor any state securities commission has approved these certificates or determined that this prospectus is accurate or complete. It’s illegal for anyone to tell you otherwise.

You might even consider putting the highlighted text in a box, like this:

Although some statutes require certain types of language—such as warranty disclaimers—to be conspicuous, they typically don’t mandate all-caps text. There’s always a better way.

Exercises

Basic

Find a ghastly example of all-caps text in a brief or formbook. Then read it closely to see how many typos you can find. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy to each colleague.

Intermediate

In the literature on typography or on effective writing, find two authorities stating that all-caps text is hard to read. Type the supporting passage and provide a citation. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy to each colleague.

Advanced

Find a state or federal regulation requiring certain sections of certain documents to be in prominent type. Interview a lawyer who sometimes prepares these documents. Consider (1) how lawyers comply with the requirement—especially the extent to which they use all capitals, (2) whether capitals are actually required, and (3) whether you think there is a better way to comply with the requirement.

A two-page document doesn’t need a table of contents. But anything beyond six pages—if it’s well organized (see §§ 2, 3, 21, 31) and has good headings (§ 4)—typically benefits from a table of contents. Your outline (§ 2) will be a good start. Yet even if you’ve neglected the outline, a table of contents can serve you well—as an afterthought. You’ll benefit from rethinking the soundness of your structure after you’ve completed a draft.

Whatever the document, most readers will appreciate a table of contents. Some judges routinely turn first to the contents page of the briefs they read. Readers of corporate prospectuses often do the same—to get a quick overview of what the document discusses. Parties to a contract can use the contents page to find the information that concerns them.

If you’re writing a brief, try creating a table of contents that looks something like the one below, by Jerome R. Doak of Dallas. Notice how every heading within the argument section is a complete sentence—an argumentative statement:

Table of Contents

If you’re writing a securities-disclosure document such as a prospectus for an initial public offering—commonly called an “IPO”—your table of contents might look like the one below. Notice that this document uses topical headings, not argumentative ones:

Table of Contents

And if you’re drafting a contract, try a table of contents like the one below. This one comes from an asset-purchase agreement. Again, the headings are topical instead of argumentative:

Asset-Purchase Agreement

An asset-purchase agreement like that one, of course, is usually the product of many hands over many years. You won’t be expected to draft it from scratch—and almost certainly couldn’t. But even when you’re starting with a form, you should prepare a contents page. The process will help you understand the structure of the document. And your readers will thank you.

Exercises

Basic

In a contractual formbook, find a 10-to 20-page contract that has no table of contents. Make one for it. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy of your table to each colleague. Be prepared to discuss whether your outline would result in any major edits—especially edits that might cause the drafter to reorganize the document.

Intermediate

Find a state statute or regulation (10–25 pages) that has no table of contents. Make one for it. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy of your table to each colleague. Be prepared to discuss whether your outline would result in any major edits—especially edits that might cause the drafter to reorganize the document.

Advanced

Find a brief, an IPO prospectus, or an asset-purchase agreement that has a table of contents. Photocopy it, and then compare it with the relevant example in this section. Write a two-or three-paragraph essay comparing and contrasting the two. If you’re part of a writing group or class, circulate a copy of your essay to each colleague, along with the table of contents you found.