Chapter 12

Closing Out the Century: Garfield, Arthur, Cleveland, and Benjamin Harrison

IN THIS CHAPTER

Being assassinated: Garfield

Being assassinated: Garfield

Overcoming the odds: Arthur

Overcoming the odds: Arthur

Serving two nonconsecutive terms: Cleveland

Serving two nonconsecutive terms: Cleveland

Following in his grandfather’s footsteps: Harrison

Following in his grandfather’s footsteps: Harrison

This chapter covers the last four presidents of the 19th century. All of them concerned themselves with fighting the spoils system and protecting the U.S. public from the excesses of big business. These presidents started the practice of government interference in the U.S. economy, which is still a common practice today. All four of these presidents, three Republicans and one Democrat, were honest, hardworking men who did their best to propel the United States into the 20th century. For this accomplishment they deserve credit, even though none of them ranks among the great presidents in U.S. history.

A Promising President Is Assassinated: James Abram Garfield

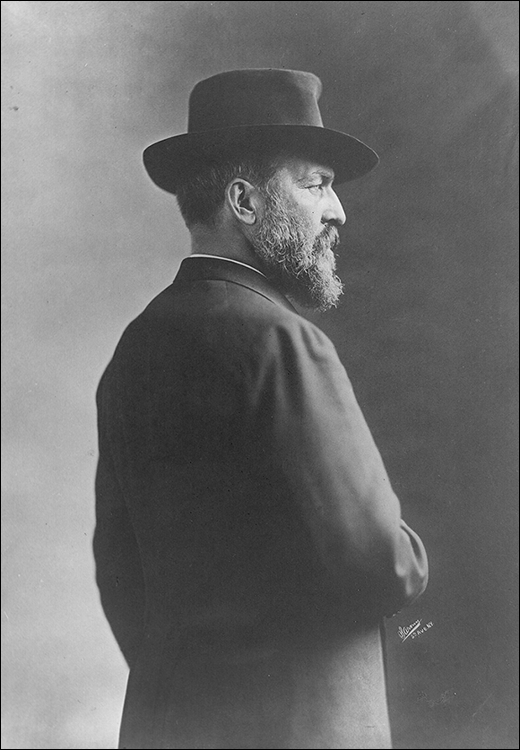

James Garfield, shown in Figure 12-1, has the distinction of being the second president to be assassinated (Lincoln was the first in 1865). He served only six months in office, four of them on his deathbed.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 12-1: James A. Garfield, 20th president of the United States.

Had he lived long enough to finish his term as president, Garfield likely would have implemented major reforms while battling the spoils system and corruption in the federal government. It would be unfair to rate him — considering that he had only two active months in office. However, judging from his long political career, Garfield would have been one of America’s better presidents. Too bad he didn’t have a chance to show his abilities.

Garfield’s early political career

Slavery helped Garfield get involved in politics. In 1856, he campaigned for the Republican nominee for president, John Frémont, who shared his views on slavery. Both Garfield and Frémont opposed slavery. In 1859, Garfield ran for a seat in the Ohio state senate and won easily.

Garfield studied law part-time while serving in the state senate. He became a lawyer in 1861, just as the Civil War broke out. He volunteered for the military and set up the 42nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry. Garfield fought bravely in Kentucky and in the battle of Shiloh. By 1863, he was a major general.

In 1862, the people of Ohio elected James Garfield to the U.S. House of Representatives. Garfield, who was still fighting the war, refused to leave to take his seat. Only after President Lincoln personally urged him to serve in Congress did Garfield resign his military commission.

For the next 16 years, Garfield served in the House of Representatives. He joined the Radical Republicans, calling for harsh punishment of the Confederacy and the right to vote for blacks. He also backed the impeachment of President Johnson. By 1876, Garfield was the leader of the Republican Party in the House. He achieved the position even though he was implicated in a bribery scandal. Garfield took $5,000 from a paving contractor in Washington, D.C., while he was chair of the Appropriations Committee, a group that handed out contracts for public works, such as paving streets.

James Garfield served as one of the Republican delegates on the Election Commission of 1877, which handed the election to Rutherford Hayes (see Chapter 11).

President James Abram Garfield (1881–1881)

The Stalwarts backed former President Grant for the presidential nomination. The Half-Breeds favored former Speaker of the House, James Blaine. Garfield supported a third candidate, John Sherman, who was the secretary of the treasury and a fellow Ohioan. Garfield made a passionate speech for Sherman at the presidential convention. The delegates liked Garfield’s speech so much that they turned to him as a compromise candidate. Even then, it was six days before he became the Republican nominee for the presidency.

Being assassinated

On July 2, 1881, President Garfield was waiting for his train at the Potomac and Baltimore railroad station on his way to New England, when Charles J. Guiteau, a deranged religious fanatic, shot him twice. One bullet hit the president’s arm and the other went into his back, but neither bullet killed him: Garfield’s doctors did that. While looking for the bullet in Garfield’s back, the doctors turned a 3-inch wound into a 20-inch wound, puncturing his liver in the process. The wound became infected, and Garfield died on September 19, 1881.

The Unexpected President: Chester Alan Arthur

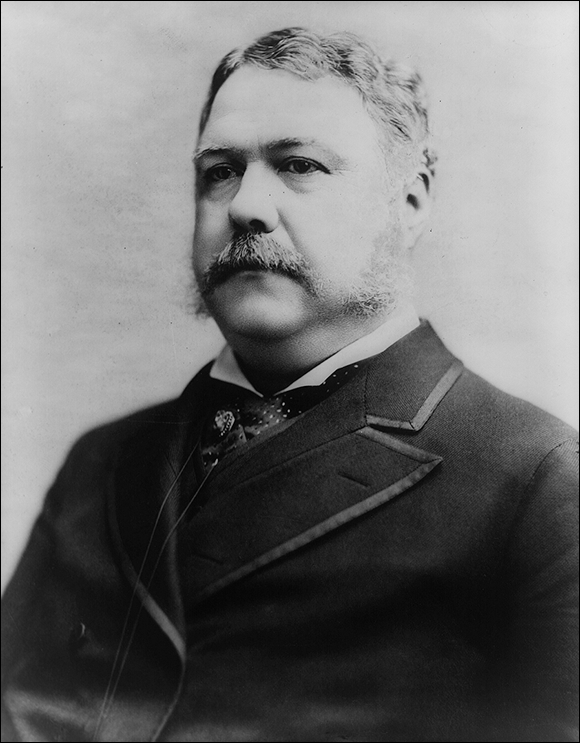

Nobody thought that Chester Arthur, shown in Figure 12-2, would ever become president, including him. Everybody expected Arthur to fail miserably and preside over a corrupt administration. He was a Republican Party loyalist who had received his political jobs based on his party loyalty.

To everybody’s surprise, Arthur abandoned the spoils system, whereby those faithful to the party are rewarded with positions in the government, and enacted the first true civil service reform act during his administration. He became the father of the U.S. Navy and was a visionary in foreign affairs. Despite expectations, Arthur turned out to be one of the better presidents of the late 19th century.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 12-2: Chester A. Arthur, 21st president of the United States.

Arthur’s early political career

The Kansas-Nebraska Act (see Chapter 9) brought Arthur into politics, just as it had Lincoln. Because Arthur was an abolitionist, one who favored ending slavery, he joined the newly created Republican Party. In 1856, Arthur became a founding father of the New York Republican Party and supported Frémont, the Republican candidate for the presidency. In 1860, Arthur campaigned for Lincoln, the Republican Party nominee, and for Governor Edwin D. Morgan of New York. When both won, Arthur was ready to receive his reward under the spoils system.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Governor Morgan named Arthur inspector general and then quartermaster general for the New York state militia. The position paid Arthur well. He did a great job equipping over 200,000 soldiers between 1861 and 1863. Arthur resigned and returned to his law practice when the Democrats won the governorship in 1863.

Arthur slowly worked his way up the political ladder. By 1868, he was one of the top men in the New York State Republican Party. When Republican Ulysses S. Grant won the White House in 1868, Arthur was given the post of collector of customs in New York City — one of the most powerful positions in the federal government at the time. In his new position, Arthur oversaw more than 1,000 people and controlled almost 60 percent of all customs receipts for the country. Arthur now controlled New York City politics. All of his employees were loyal Republicans who received their jobs based on party ties. Some of them were incompetent, and many of them were corrupt.

In 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes investigated Arthur and the customhouse. Even though Arthur was not found to be corrupt, Hayes fired him in 1878, and Arthur returned to the law.

Staging the comeback of his life

President Chester Alan Arthur (1881–1885)

Chester Arthur became president on September 20, 1881, after President Garfield was assassinated. Everybody expected Arthur to be a puppet of the Stalwart branch of the Republican Party, but Arthur had other ideas. He knew that he was a one-term president — he suffered from Bright’s disease, a terminal kidney disorder. So he chose to initiate reforms.

- Political tests for federal officeholders became illegal.

- Alcoholics, even if they were loyal party alcoholics, couldn’t be hired anymore.

- Competitive tests for some civil service positions became mandatory. However, the act only affected 14,000 out of the 131,000 federal positions.

- Subsequent presidents were allowed to classify more civil service positions closed to the spoils/patronage system.

In the area of foreign policy, Arthur was very innovative. Some of his ideas seem visionary even today:

- The organization of an international conference to create standard time zones throughout the world.

- The proposal of a single currency for North and South America to facilitate trade.

- The negotiation of building a canal through Nicaragua and not Panama. (The Senate, favoring Panama as the site for a canal, refused to ratify the treaty.)

Other successes during Arthur’s presidency included the strengthening and modernizing of the U.S. Navy.

In 1884, Arthur changed his mind about being a one-term president and wanted to run for reelection. However, his reforms had alienated many in the Republican Party. Arthur lost the Republican nomination to Senator Blaine.

Arthur went back to practicing law, but not for long. His disease caught up with him. He died on November 18, 1886, in New York City.

Making History by Serving Nonconsecutive Terms: Grover Cleveland

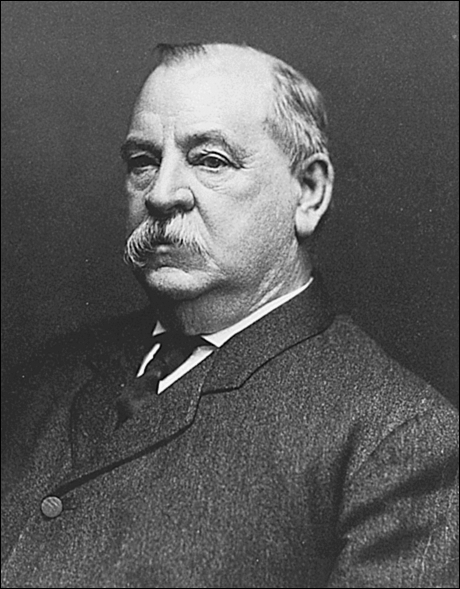

Grover Cleveland, shown in Figure 12-3, has the distinction of being the only president in U.S. history to serve two nonconsecutive terms. He proved to be an independent spirit, pursuing policies that he thought were right. In turn, he alienated many in his own party. His presidencies were characterized by an emphasis on fighting corruption and the spoils system.

Cleveland was actually more conservative than his own Democratic party, which allowed him to become a Democratic president in Republican times. Because of his independence and strong character, he deserves to be ranked in the top 15 of U.S. presidents.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 12-3: President Grover Cleveland, the 22nd and 24th president of the United States.

Cleveland’s early political career

Cleveland showed his independence early: The uncle who sponsored him was one of the founders of the Republican Party in Buffalo, but Cleveland became a Democrat.

The veto mayor

Cleveland started to work for the local Democratic Party in 1863, becoming the assistant district attorney of Erie County. He proved to be a tough crime fighter, prosecuting corruption unmercifully. The people of the county rewarded him for his work by electing him sheriff in 1871. He continued his crusade against corruption and crime and received a reputation as a hardworking, honest politician. The Democratic Party rewarded him for his loyalty by running him for mayor of Buffalo in 1881. He won easily.

Cleveland went after the corruption in the Buffalo government. He targeted politicians from both parties and consistently vetoed bills that benefited the aldermen personally. Cleveland believed that the type of corruption that was taking place shouldn’t exist. His consistent vetoing of bills earned him the nickname “the Veto Mayor.”

The veto governor

To his great surprise, the Democratic Party approached him in 1882 to run for the governorship of New York. The party couldn’t decide between the two frontrunners, so it decided to go with a new face instead. The public was fed up with constant corruption and wanted change. They wanted an honest person in office. The Veto Mayor fit the bill and won the governorship easily.

Not surprisingly, Cleveland continued his independence as governor of New York. He refused to hand out jobs purely on party affiliation. In addition, Cleveland continued to veto bills liberally.

A surprise nominee

In 1884, the Democratic Party went looking for a presidential candidate. The Republicans nominated Senator James Blaine of Maine, who was accused of taking money from businesses while he was the Speaker of the House. A wing of the Republican Party broke off and proclaimed that they would back any Democrat who was honest and opposed corruption. Cleveland fit the bill. He became the Democratic nominee and won the presidency in a very close election in 1884.

President Stephen Grover Cleveland (1885–1889 and 1893–1897)

Cleveland continued his independent streak as president. For his cabinet, he picked the best and most capable people. He didn’t care whether they were former Confederates, or even Republicans.

Cleveland’s first act was to enhance the scope of the Pendleton Act to further promote civil reform. He actually doubled the number of federal jobs, which were now based on merit and not patronage. Next, he turned into the “Veto President.” In his first administration, Cleveland vetoed over 200 bills; most of them were pension bills that extended money to Union war veterans. He paid a price for the vetoed bills when veterans’ organizations backed his opponent, Benjamin Harrison, in 1888.

Reforming the country

Two major pieces of legislation stood out during Cleveland’s first term:

- The Dawes Act of 1887: This act, which ended in failure, provided for the distribution of tribal American Indian lands to individual Native Americans. But, instead of becoming independent farmers, as Cleveland had hoped, many Native Americans lost their land due to fraud.

- The Interstate Commerce Act of 1887: This act, which proved to be the more successful of the two, fixed the price for railroad tickets at a just and reasonable level. Although the act was ignored in the beginning, it was the first major attempt by the federal government to regulate U.S. businesses. It set a precedent for many more acts to come.

Losing in 1888

Cleveland ran for reelection in 1888. He squared off against war hero Benjamin Harrison, the Republican nominee.

Serving again

In 1892, the Democratic Party was split one more time. The Silver Democrats supported the free, unlimited coinage of silver to increase the money supply in the United States. They believed that it would allow small farmers to repay their debts more quickly. The Gold Democrats, of which Cleveland was one, believed that money should be backed by gold so that currency could be exchanged into gold at any time. The amount of gold reserves determined how much money was in circulation.

Cleveland soundly defeated the incumbent Harrison, reclaiming the office of president for the Democratic Party.

Cleveland’s second term proved to be fairly unsuccessful. He alienated industrialists by supporting tariffs, workers by breaking a strike, and imperialists by refusing to annex the Hawaiian Islands.

Dealing with a depression

When he came back to the White House, Cleveland faced the great depression of 1893, a worldwide depression that had spread to the United States.

The trigger industry for the economic depression in the United States was the railroads, which expanded too quickly. By 1893, the whole country faced an economic downturn. The conventional wisdom of the day dictated that Cleveland not interfere because the economy would right itself.

The depression dragged on for years, undermining the public’s trust in the president. To top it all off, a group of impoverished men and their families, organized by Jacob Coxey, marched to Washington, D.C., to ask Cleveland for help. The group, called Coxey’s Army, wanted Cleveland to spend federal money to create jobs. Cleveland just ignored them. The move was not good for his publicity. More and more Democrats turned away from their president.

Instead of trying to cure the ailing economy, Cleveland pushed for lower tariffs. He got his wish in 1894, when Congress lowered tariffs on many foreign goods. However, Republicans and Northern Democrats actually watered down the bill by increasing tariffs on certain industrial goods.

Punishing striking workers

The most damaging event to the Cleveland presidency occurred in 1894 when employees of the Pullman Company went on strike. The American Railway Union joined the strike in support of the workers at Pullman, shutting down all railroad traffic.

Because the strike handicapped the federal mail service, Cleveland believed that the federal government had the right to interfere. He sent troops to break up the strike and threw union leaders into jail. Workers began to turn away from the president.

Saying no to imperialism

Cleveland opposed imperialism, or the acquisition of colonies, by the United States. His predecessor, President Harrison, signed a treaty annexing Hawaii to the United States. Cleveland considered it to be imperialism, knowing that a majority of Hawaiians opposed the idea. He withdrew the treaty from the Senate, and Hawaii was not annexed. This act infuriated the many U.S. citizens who believed in imperialism.

He again passed up a chance to get involved in territorial expansion when Spain cracked down on its colony in Cuba, killing thousands, in 1895. Many U.S. citizens, including Republicans and Southern Democrats, wanted to use military action to not only help the people of Cuba, but also to annex it. Cleveland refused.

Cleveland felt so strongly about imperialism that he joined the Anti-Imperialist League, which opposed the annexation of the Philippines in 1898, after he left office.

Retiring to Princeton

By 1896, Cleveland had managed to alienate not only his own party, but also much of the public. The Democratic Party opted to nominate William Jennings Bryan for president instead of Cleveland. Cleveland didn’t even campaign for Bryan.

Cleveland retired to his home in Princeton, New Jersey, and became a trustee at Princeton University. He became close friends with the university’s president, a professor of government named Woodrow Wilson, who would become president of the United States in 1913.

The Spoiled Republican: Benjamin Harrison

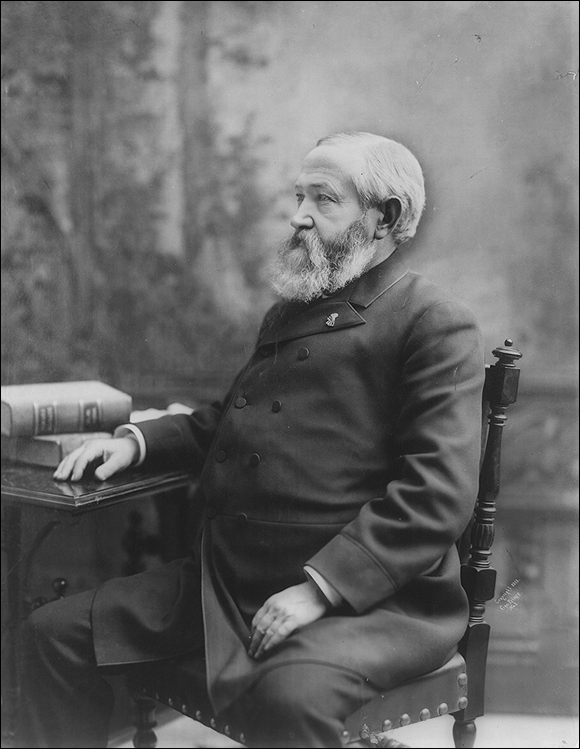

Benjamin Harrison, shown in Figure 12-4, has the distinction of being the only grandson of a former president to be elected president. Harrison was a devout Republican — so much so, that many considered him a puppet of the Republican Party. However, Harrison proved to be an honest, capable president who initiated major legislation during his term. He was actually one of the better presidents of the late 19th century.

Harrison’s early political career

After moving to Indianapolis in 1854, Harrison opened a prosperous law firm and became active in the Republican Party. In 1857, he became the city attorney of Indianapolis. In 1860, he was elected Supreme Court reporter for the state of Indiana.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 12-4: Benjamin Harrison, 23rd president of the United States.

At first, Harrison sat out the Civil War. But in 1862, the governor of Indiana asked him to set up the 70th Indiana Volunteer Regiment. He accepted and saw action in Kentucky and in the bloody battle of Atlanta. He proved to be an exceptional leader in the Union army, retiring with the rank of brigadier general.

Benefiting from the spoils system

After serving in the Civil War, Harrison returned to his law practice in Indiana. He stayed active in Republican politics. He tried for the Republican nomination for governor in 1872, but he was unsuccessful. He tried again four years later. This time he received the nomination. He lost the race by 5,000 votes, but he received more votes than any other Republican in Indiana history. Over the next ten years — thanks to the spoils system (see “The spoils system” sidebar in Chapter 11) — Harrison held a slew of political offices, including the following:

- Member of the Mississippi Commission: The commission oversaw the economic development of the river.

- Chairman of the Indiana delegation to the 1880 Republican convention: Harrison delivered the delegation’s votes for James Garfield, helping him win the nomination.

- U.S. senator: Harrison championed Union war veterans. The veterans became some of his staunchest supporters in the 1888 election. In addition, Harrison stood for high tariffs, which pleased business, and supported Native American rights.

Getting nominated in 1888

In 1888, the Republican field for the presidential nomination was wide open after the frontrunner, Senator Blaine, refused to stand for the nomination. He endorsed Harrison instead.

Harrison was the ideal candidate for the Republicans. He had great name recognition, thanks to his grandfather, former president William Henry Harrison. War veterans loved him and despised the Democratic incumbent, Grover Cleveland. Harrison had a good war record, while Cleveland had none. In addition, Harrison was able to deliver Ohio, where he was born, and Indiana, where he resided. After receiving the Republican presidential nomination, Harrison, despite losing the popular vote to Cleveland by 100,000 votes, defeated the incumbent president in the electoral vote, 233 to 168.

President Benjamin Harrison (1889–1893)

Harrison entered office under a dark cloud. He lost the popular vote by 100,000 votes, and many looked upon him as a Republican Party stooge. To his credit, he disappointed the Republican Party by nominating people to his cabinet based on their qualifications. His cabinet included people like Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft, both future presidents.

In the area of domestic policies, Harrison had several major accomplishments. These achievements included

- The Dependent Pension Act: This bill, passed in 1890, guaranteed pensions to all disabled Union war veterans. It further provided assistance to children and dependent parents of Union war veterans.

- The Sherman Antitrust Act: This act made it illegal to establish a monopoly, or a business that dominates a whole sector of the economy. It gave the federal government the power to break up these monopolies.

- The McKinley Tariff Act: This bill enacted the highest tariffs in U.S. history, about 48 percent, on foreign goods.

Harrison was also successful with his foreign policy. He increased the size of the U.S. Navy and negotiated a treaty annexing Hawaii. Later, President Cleveland, opposed to imperialism, voided the treaty upon his return to the White House. Harrison set the foundation to acquire American Samoa and settled a dispute with Great Britain over fishing rights in the Bering Sea.

Losing in 1892

President Harrison ran for reelection in 1892. He faced off against former President Cleveland one more time. The main campaign issue was tariffs. Harrison wanted to increase tariffs, while Cleveland advocated a reduction.

Harrison didn’t have his mind on the campaign, because his wife was dying. He suspended his campaign in October, and Cleveland followed suit out of respect for the first lady. Caroline Harrison died two weeks before the 1892 election. Her husband never got over her death. Harrison lost the election in a landslide, receiving only 145 electoral votes to Cleveland’s 277.

Returning to his legal career

Harrison returned to Indianapolis in 1893 and practiced law one more time. He also became an author. He wrote two books, one on the presidency and one on the state of the country.

His greatest legal accomplishment occurred between 1897 and 1899, when he represented Venezuela against Great Britain in a border dispute. Harrison filed an 800-page brief and spoke for 25 hours at the five-day tribunal. Before he was done, the British counselor informed his government that its case was lost, though the ultimate resolution of the conflict favored Great Britain. Two years later, on March 13, 1901, Benjamin Harrison died of pneumonia.

Garfield was a Republican senator from Ohio in 1880 when the Republican Party split into two camps, the Stalwarts and the Half-Breeds. The two factions disagreed on the issue of patronage, the practice of handing out federal jobs to party loyalists and friends. Both groups supported patronage but disagreed over how the jobs should be handed out.

Garfield was a Republican senator from Ohio in 1880 when the Republican Party split into two camps, the Stalwarts and the Half-Breeds. The two factions disagreed on the issue of patronage, the practice of handing out federal jobs to party loyalists and friends. Both groups supported patronage but disagreed over how the jobs should be handed out. President Garfield was ambidextrous, meaning he could write with either hand. He got a kick out of astounding people by writing Latin with one hand and Greek with the other.

President Garfield was ambidextrous, meaning he could write with either hand. He got a kick out of astounding people by writing Latin with one hand and Greek with the other. Garfield’s assassin had asked to be named consul to Paris but was turned down by Republican leaders. Guiteau was angry, as well as quite mad. He believed that God told him to assassinate the president to save the country and the Republican Party. The federal government hanged Guiteau in 1882.

Garfield’s assassin had asked to be named consul to Paris but was turned down by Republican leaders. Guiteau was angry, as well as quite mad. He believed that God told him to assassinate the president to save the country and the Republican Party. The federal government hanged Guiteau in 1882. President Garfield’s deathbed quote: “He must have been crazy. None but an insane person could have done such a thing. What could he have wanted to shoot me for?”

President Garfield’s deathbed quote: “He must have been crazy. None but an insane person could have done such a thing. What could he have wanted to shoot me for?” Arthur’s major accomplishment as president occurred in 1883, when Congress passed the Pendleton Act, the first civil service reform bill in U.S. history. The Pendleton Act established the following provisions:

Arthur’s major accomplishment as president occurred in 1883, when Congress passed the Pendleton Act, the first civil service reform bill in U.S. history. The Pendleton Act established the following provisions: