CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 1 CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 1Forty years ago there was a seismic break in the geography of world power. A dozen countries that produced much of the world’s oil—almost all of them in the Middle East—declared an oil embargo against the West. They were retaliating for the humiliation of the 1973 Arab-Israeli war, but also announcing their independence from the American and European global oil companies that had long controlled their production and prices. Oil prices tripled (from about $3 to about $10 a barrel), and the United States was plunged into the nastiest recession of that time since the Great Depression. Runaway inflation in the United States and a collapsing dollar prompted another tripling of oil prices in 1979 and the steep recession of 1981–1982.

The economic collapse combined with the end of oil price controls in the United States caused a sharp drop in oil demand, and oil prices dropped steadily through the middle 1980s. Memories of the crisis faded when prosperity returned in the 1990s, and the faux American boom of the 2000s brought a return of the old profligacy, as soccer moms ferried their kids in vehicles modeled after cattle-country pickups and Gulf War troop carriers. More and more of US manufacturing migrated overseas, and the trade deficit, about a third of it energy-related, went off the cliff. In the run-up to the 2008 financial crash and Great Recession, crude prices scraped $100 a barrel. Nightmare visions of a 1970s replay seemed all too plausible.

Behind the scenes, however, awareness was slowly spreading that the United States was swimming in inexpensive energy. As the reality of the American energy position sunk in, engineers stopped work on giant multi-billion-dollar natural gas importing facilities in Louisiana and Texas, and began reconstructing them to export gas. In the fall of 2012, the International Energy Agency (IEA) forecast that by 2020 the United States would surpass both Saudi Arabia as the world’s largest oil producer and Russia as the world’s largest gas producer.1

The new American energy bonanza stems primarily from “unconventionals,” land-based hydrocarbon deposits that geologists have long known about but which were considered inaccessible on both technical and economic grounds. The unconventional energy bonus has also been supplemented by the steady expansion of the industry’s deep-sea drilling capabilities.

Coal, oil, and natural gas all derive from decayed plant and animal matter that has slow-cooked within the earth for hundreds of millions of years. As dead organic material accumulated on the muddy bottoms of swamps, lakes, and oceans, the mud sank and was gradually compressed into sedimentary shale rock, trapping the organic matter within its many layers and fault lines. Compression generates heat, which gradually transformed the organic matter into ordered chains of carbon and hydrogen atoms. The simplest chain, one carbon and four hydrogen atoms (CH4) is methane, the premier heating gas, and one of the most abundant organic compounds on earth. The hydrocarbons that are used to manufacture gasoline are much heavier, with four to twelve carbon atoms and multiples of hydrogen atoms; those used to make diesel fuel are heavier still. The hydrocarbons favored for oil and gas production tend to be derived from the decay of phytoplankton in marine (saltwater) settings and of algae in freshwater lakes, while coal is thought to derive from swampy peat forests like those still found in some southeast Asian countries.

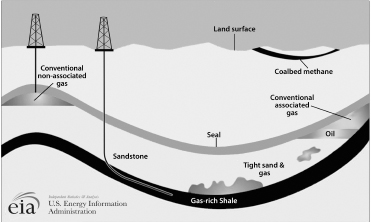

Shale is therefore called a source rock—it traps and transforms hydrocarbons. By itself shale is nearly impermeable, but over the vast stretches of geologic time, liquid or gaseous hydrocarbons seep from between the shale layers into the surrounding earth. Conventional oil reservoirs form when a hydrocarbon-rich source rock leaks into a highly permeable medium like sand formations—the “reservoir rock.” If there is another layer of shale over the reservoir, it will act as “cap rock,” sealing the seepage in the reservoir. Drillers harvest the oil or gas by sinking a pipe through the cap rock into the reservoir, and sucking it out as if with a straw. For traditional oil and gas exploration companies, the hard part is finding the reservoirs; although geologic surveying technology is improving at a rapid rate, most oil exploration efforts still end up with dry holes.

Shale, however, can serve as both a source rock and a reservoir rock. If the openings between the horizontal layers are wide enough it is always possible to leach out usable hydrocarbons. But the economics have been unattractive. Shale formations are often very deep in the earth, so drilling is expensive. Even in the best shale, hydrocarbons rarely make up more than 6 percent of the rock weight. And although shale formations often stretch over tens of thousands of square miles, they’re typically only a few hundred feet thick. Drilling that far down to access such a paltry area of shale, with such a small payload of hydrocarbons, made no sense.

Shale is not the only source of unconventional gas and oil, although it is by a large margin the game changer for the United States in the near term. There are at least three others: coalbed methane, or natural gas locked up in the seams of coalbeds; oil sands—heavy, rock-like concentrates of hydrocarbons permeating sand formations; and oil shale—which is not shale and has nothing to do with oil-bearing shale formations. Coalbed methane and oil sands are being exploited now, while oil shale is still quite far from commercial exploitation. The recovery technologies are described at the end of the chapter. The rest of this chapter will focus on shale-based gas, natural gas liquids, and oil, where the main opportunities lie.

The American shale revolution was born from a convergence of technologies. Two critical ones—directional drilling and well stimulation by hydraulic fracturing—were already well established, but needed to be adapted to shale. Both the industry and the government had excellent geologic maps of underground resources, and good information on the most likely shale opportunities. Other critical technologies were the software, hardware, and tools required to track and precisely direct drilling tools deep underground and to monitor wells and fractures.

The political road was eased by the fact that the first important shale discoveries were in lightly populated communities, and in America, unlike in most other countries, landowners almost always own the associated mineral rights. Once shale drilling became technically feasible, therefore, companies could quickly assemble the large areas of underground rights required for profitable shale production.

Credit for working out the final engineering solution usually goes to George P. Mitchell of Mitchell Energy Co., who invested about a decade and $6 million of his own money to create the first complete replicable technical protocol for successful shale exploitation. Mitchell’s first successful horizontal well, in the Barnett shale, right outside Fort Worth, Texas, was completed in 1991. In 1998, after successfully solving the challenge of mass hydraulic fracturing with “slippery” polymers (to lower the friction in the well pipe), Mitchell achieved the first commercial production of shale gas. Mitchell retired in 2002, after selling his company to Devon Energy. The Barnett is now the most intensively developed shale gas and gas liquids site in the world.

Mitchell richly deserves his honors for making shale exploitation a practical business, but the conventional account usually leaves out the role played by the federal government in the development of the essential technologies. In the midst of the oil price crisis of the 1970s, President Gerald Ford launched the Eastern Gas Shales Project to develop shale gas extraction technologies through demonstration contracts. In parallel, the agency that is now the Department of Energy joined the industry in funding research and demonstrations by the industry-sponsored Gas Research Institute. The government’s Morgantown Energy Research Center (now the National Energy Technology Laboratory) was already involved in a substantial coalbed methane program, which contributed to the same technologies that enabled shale exploitation. The essential three-dimensional seismic imaging technology (to track the progress of drilling) was developed at the Sandia National Laboratory, originally for use in coal mines, while researchers at Morgantown made important contributions to drill bit construction and directional drilling technology. Mitchell himself was a leader in pressing the case for government support, and his successful 1991 well was partially funded with federal research and development (R&D) money. In addition, in 1980 the Carter administration and the Congress passed a special production tax credit for unconventional gas (this expired in 2002 when the industry had achieved solvency).2 Altogether, the joint federal-industry development program in unconventional energy was pursued in much the same spirit as that of the early semiconductor industry.

I will describe the key technologies below, while reserving issues of safety and environmental and related issues for Chapter 3.3

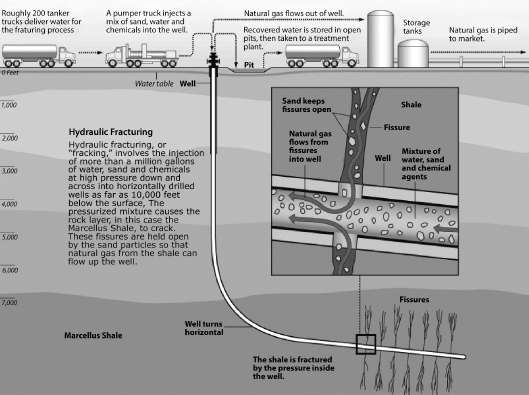

Directional drilling is essential because of the typically narrow vertical profile of shale formations. A shale drilling rig sinks a well vertically until it nears the target shale formation, then, like the rigs used for the Devon wells described in the Prologue, it gradually turns the drilling tool so it travels through the shale in a more or less horizontal plane, and even maneuvers the drill to follow the contour of the shale. Wells are routinely drilled to depths of two miles or more, and then extended horizontally through the shale for as much as another two miles. To compensate for the thin distribution of hydrocarbons, shale well pipes are perforated so they can absorb hydrocarbons along their entire horizontal length. And since the shale formations typically stretch in all directions, a single rig, or “pad,” may sink up to ten wells to cover the accessible shale terrain. An additional bonus of working in shale is that the distribution of the hydrocarbons tends to be fairly uniform over broad areas, so dry holes are a rarity. The economics are more like those of a manufacturing operation rather than of conventional gas and oil drilling.

Wells are sunk in stages. In the first stage, a large diameter hole is sunk to a depth of up to 150 feet. A heavy drilling mud or other fluid flows in behind the drill to stabilize the walls of the hole. Pipe casing, usually in thirty-foot lengths, is inserted as the drilling proceeds, and as each casing stage has been placed, cement is forced down the casing under sufficient pressure to force it out the bottom and back up around the sides to fill the space between the hole walls and the exterior of the casing. That first segment is called the “conductor casing,” since it sets the vertical direction and serves to stabilize the subsequent casing insertions.

The next stage is the “surface casing,” a narrower pipe that fits within the conductor casing. The surface casing is always sunk to a depth below any intervening drinking water aquifer. Depending on the depth of the well, several further “intermediate” and “production” casings are inserted and similarly stabilized with cement. The final production casing is usually only four to six inches in diameter in order to keep the volumes of required mud and cement within manageable proportions. (See graphic on page 27.)

Hydraulic fracturing is necessary to stimulate the release of hydrocarbons from the shale, by releasing a high-pressure burst of fluid—or sometimes compressed air or a hot gas—into the shale. The pipe must first be perforated, using perforating gun tubes. The tubes come in a variety of configurations: the ones used at the Devon well we visited were studded with stainless-steel covered openings about an inch in diameter, forty-eight in each eight-foot tube-length, one tube to a stage—and, with ten stages, 480 collection perforations in all. The powerful explosives are packed into bazooka-shell-like shaped charges to concentrate on a small point. The leading tip impacts at 25,000 to 30,000 feet per second generating ten to fifteen million pounds per square inch. Those pressures “overcome” casing and cement strength—basically, they melt it—and open a clean hole into the shale, penetrating a foot or so beyond the tube. The tube construction also embodies sequenced magnetic and nonmagnetic materials that can be interpreted by external sensors, allowing the controllers to place the tubes with accuracy of within an inch or so.

Source: EIA

The typical fracturing fluid consists almost entirely of freshwater, plus a small volume of sand called a “proppant,” sifted to a precise size to prop open the newly created fracture channels, and a cocktail of chemicals. The mix of chemicals will vary by site and geology, but it commonly includes friction-reducing polymers and acids to clear perforations and to abrade and widen the fracture openings. The chemicals usually make up only about a half of one percent of the fracking fluids, but since a single well usually requires between three and six million gallons of fluid, some 15,000 to 30,000 gallons of chemicals will be applied to each new well. Assuming ten wells are sunk from a drilling pad, each pad area will absorb between 150,000 and 250,000 gallons of chemicals.

Given the miles of pipe to be traversed and the forces required to fracture shale rock, the fluid is injected under great pressure by trailer-truck-size diesel engines—the Devon site had eighteen—that generate up to 15,000 pounds of pressure per square inch (psi). Newly available software and hardware can generate real-time pictures from microseismic data showing the path of the fluid into the rock fractures. Chemical markers help trace the distribution of the proppant and identify areas of blocked holes in the perforated pipe. Once the fractures open, the pressures within the shale will immediately start the flow of hydrocarbons into the well pipe through the perforations.

The violence of the fracking makes it essential that well and casing pressures be carefully monitored during and after the operation to identify cement breaks or other leaks. Any fugitive, or uncontained, pressure outside of the well pipe is cause for heightened alert, and sustained pressures probably indicate liberated gases migrating up the perimeter of the well. The first rush of gas up the well pipe will bring considerable flowback of the fracking fluid, which will have been contaminated with heavy metals and other potentially toxic substances from the rock fractures, including naturally occurring radioactive materials or NORMs. (The organic matter in shale sometimes binds uranium and its derivatives.)4 The fracking fluid is then followed by “produced” fluid, water that has been trapped in the rocks for eons, which is frequently more noxious than the fracking fluid. Good well management requires the sequestration and safe disposal or recycling of both the fluids and their associated hydrocarbons.

Conventional and Unconventional Oil and Gas Recovery

Source: EIA

When organic matter is trapped under sedimentary rock and gradually pushed deeper into the earth, microbial action and increasing heat expel oxygen, microbial methane, and other contaminants. If compression continues and temperatures rise to about 120°F, the organic material congeals into an insoluble substance called kerogen, the source of all hydrocarbon fuels. As temperatures continue to mount, all noncarbon material, including the hydrogen, is gradually stripped away; eventually as temperatures rise over 400°F, there is nothing left but an inert mass of nonreactive carbon. The different stages of the kerogen’s transformation generate various hydrocarbons of commercial interest, with the earlier stages typically being the heavier and binding the most contaminants. Later stage productions include the “wet” gases that are sometimes liquid at atmospheric pressures, and generally have fewer contaminants. Methane is the smallest stable hydrocarbon molecule and the last usable kerogen product and is often found in a nearly pure state.5

Geologists have been examining the US shales at least since early in the twentieth century. They were long understood to be a source of valuable commodities, including uranium, as well as oil and gas. Analysis of the shales generally proceeds by sinking boreholes, an expensive process given the depth of many shales, and acquiring samples for chemical and other testing. The presence of recoverable hydrocarbons is deduced from a range of indicators. The shale’s thickness and its thermal maturity—a heat index that suggests its kerogen’s stage of transformation—can both be measured directly. Other important data include the shale’s total organic content, usually expressed as a percentage of weight (4–6 percent is a good number); the amount of adsorbed gas; the volume of free gas within pores and fractures; and the source rock’s permeability. Since those data are hard to measure directly, they are usually derived from sophisticated mathematical models, using radio-metric data, patterns of magnetism, satellite thermal images, three-dimensional seismic analysis, as well as empirical data from similar developed shales. Gamma radiation, for example, can be a good indication of the quantity and nature of the kerogen.6

The map on the previous page shows the major shale “plays”—shale areas under active exploitation in the continental United States. Shales predominate throughout the middle sections of the country, covering much of the area between the western slopes of the Appalachians and the eastern slopes of the Rockies. The geologic record suggests that they are the sedimentary relics of large inland seas that inundated the region some 450–400 million years ago. They can be very large—the Marcellus shale, which stretches from western New York State to Ohio and southward to Virginia, covers an area of more than 100,000 square miles. The depth and thickness of shales also vary quite dramatically. The depth of the Marcellus undulates from 4,000 to 8,500 feet below the surface, and its thickness varies from 50 to 200 feet. With total recoverable reserves of 141 trillion cubic feet (Tcf), the Marcellus is one of the world’s largest reservoirs of “dry gas”—almost pure methane that, with only minimal processing, can be piped directly to electrical utilities and to heavy industrial establishments to power their generators and machinery.7

But the Marcellus is just one part of a massive shale system, the Appalachian Basin that extends from the Lake Ontario region down to Kentucky. The Utica shale lies under the Marcellus, but extends further in every direction and may have twice the area. It is also thicker (ranging from 100 to 500 feet) and much deeper (from 2,000 to 12,000 feet). Over the last couple of years, the Utica has attracted a great deal of drilling interest because it produces heavier products than the Marcellus—natural gas liquids (NGLs) like propane, butane, and “natural gasoline”—that currently command a higher market price than dry gas. A 2012 survey by the United States Geological Survey (USGS), known for its conservative analyses, concluded that the Utica had recoverable reserves of thirty-seven Tcf of natural gas, or the rough energy equivalent of more than six billion barrels of oil,* plus an additional 1.2 billion barrels of recoverable oil and NGLs.8 A third large formation, the Devonian, extends from the southwestern edges of the Marcellus further south and west into Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia, in several varying formations with an area of about 75,000 square miles, with substantial reserves of both gas and NGLs.

The so-called mid-continent region shale formations, the Fayetteville shale of Arkansas and the Woodford shales of Oklahoma, are far smaller than the Appalachian Basin shales, with a combined area of about 13,000 square miles. The depths are quite variable, ranging from 1,000 feet all the way down to 14,500 feet, or nearly three miles, in a branch of the Woodford. A 2010 survey of most of the area by the USGS concluded that there are total recoverable reserves of thirty-six Tcf of gas, or about the same as the Utica.9

The Gulf Coast region has three major formations, with an area of about 14,000 square miles between them. The Haynesville shale in east Texas and Louisiana, according to industry sources, has very large gas resources, while the Eagle Ford in east Texas has been producing large quantities of shale gas and “tight” oil, or oil retrieved from oil-bearing shale and sandstone. Industry sources believe that its oil production capacity is of the same scale as in the Bakken formations (see below). The Floyd-Neal shales in Alabama and Mississippi are also believed to have substantial reserves of gas.

The producing areas of the Southwest region include the Barnett shale around Dallas-Fort Worth, the location first exploited by George Mitchell; the Permian Basin region in far-west Texas, once the world’s most productive oil region; and further west into the Avalon-Bone Springs region of west Texas and New Mexico. The Barnett is the most intensely developed shale gas and liquids site in the world, with rigs that once dotted the Dallas-Fort Worth airport. Production began with natural gas, but over the past year has swung sharply toward liquids, since the heavier fractions like ethane, which competes with petroleum-sourced naphtha as a chemical feedstock, command higher prices than methane. As this book goes to press, Texas producers are enthusing over what may be a massive find in the state’s Permian Basin, which is plausible, given its once-great oil endowment.

The Rocky Mountain region has two distinct producing areas—the Green River and Piceance Basins of Wyoming and Colorado; and the Bakken oil formations of North Dakota and Montana, and well into Canada, which may be the single largest oil producing formation in US history.

The Bakken formation mostly consists of oil-bearing sandstone squeezed between two shale formations. Fracturing and well technologies are basically the same as for natural gas, adjusted for the different weight and viscosity of the material. Production has jumped from 10,000 to 15,000 barrels a day in 2008 to a half million a day in 2012; ExxonMobil expects the Bakken to reach a steady state of a million barrels a day within the next several years.10 North Dakota is now the second largest oil-producing state after Alaska.

Wyoming and Colorado have rich natural gas and NGL shales. A 2002 USGS assessment of the Green River Basin in Wyoming concluded that there was more natural gas than even in the Marcellus, and it is found in relatively porous sandy formations that are accessible by vertical wells. But the area is still better known for its spectacular reserves of oil shale, which may be as much as 60 percent of the world total, although it will be a long time, if ever, before they make a meaningful contribution to the usable hydrocarbon supply.

The final region, the Far West, so far consists of a single oil-bearing area—the Monterey/Santos shale formations in southern California. California was once one of the largest of America’s oil-producing regions, and preliminary assessments are that the oil-bearing shale formations may hold far more oil than even the Bakken.

The table on page 35 offers a snapshot of companies that are competing in the shale oil and gas production process.* I have left out the oil majors—ExxonMobil, Shell, Occidental, Hess—who are rapidly building their footprint in the business. Although ExxonMobil and Shell are among the largest players in the shale and related industries, their other operations are so big that their their financial reports necessarily provide less detail than those of more mono-focused companies do. The companies in the list have varied histories. Several entered from backgrounds in technically challenging offshore drilling, others previously had pipeline, oil field servicing, or gas processing businesses, and still others were pure startups by experienced people. All of them are substantial firms; only one on the list had annual sales of less than $1 billion.

Over the past two years, the dominant factor in the American industry has been overproduction—not so much with respect to demand but with respect to transport capacity from the production areas. Production of natural gas has run well ahead of “out-take” capacity, so prices of natural gas have fallen very sharply—from as much as $8 per thousand cubic feet (Mcf) to, at one point, slightly under $2/Mcf last year. As this is written, prices are hovering in the $3.50/Mcf range, close to the $4–6/Mcf the industry needs to be profitable. A similar, but less severe, situation exists with shale oil production. Under normal circumstances, there is a tight relationship between American prices for crude based on a “sweet” non-sulphurous crude pricing hub—the West Texas Intermediate (WTI) and the “Brent” price for the more sour oil from the Arabian Peninsula. Because of a glut of American crude that has overwhelmed shipping capacity, the WTI has been consistently 20 percent or more lower than the Brent.

The industry continues to invest aggressively. Capital spending in 2013 is projected to be $348 billion, with about two-thirds of it in the upstream—land acquisition, exploration, and production. The investment announcements highlight the growing dominance of the industry majors; ExxonMobil, Shell, Hess, Chevron, and Conoco Phillips are all up at the top of the list. The biggest jump in spending is the near-quintupling of investment in pipelines. Gas prices will not rise to profitable levels until the industry can reach more of its natural customers; ratcheting up pipeline investment is the only way to make that happen.

In his January 2012 State of the Union address, President Obama said that “We have a supply of natural gas that can last America nearly one hundred years.” That sounds like a definitive report of a measured quantity of gas. In fact, it is highly speculative. Only a tiny fraction of the known natural gas shale formations have had wells sunk in them, so there are few data points on recoveries, gas quality, flow rates, and other parameters. All current estimates are drawn from mathematical models that at their best can make only gross approximations. The USGS uses a probabilistic model that gathers the standard modeling inputs, the experience in similar geologic formations, the percentage of the target area that has not been tested, as well as the constraints of current technology. The rapid progress of “current technology” by itself has generated steady increases in the estimates of recoverables.

Until last year, that is. At the time of the president’s speech, the US Energy Information Administration’s (EIA) best estimate of technically recoverable resources* (TRR) of natural gas was 750 Tcf, the rough energy equivalent of 130 billion barrels of oil, which is about thirteen years’ worth of current production by Saudi Arabia—so, yes, that is a lot of energy. But in the summer of that same year, the EIA reduced its gas recovery estimate to just 482 Tcf, due entirely to a two-thirds reduction in the estimate of reserves in the Marcellus shale.

The backstory is that in 2002, the USGS surveyed the Marcellus and came up with a mean probability reserve of only 1.9 Tcf of gas, based on the performance of older vertical wells. When the advent of horizontal drilling brought a rush on gas extraction by entrepreneurs into the Marcellus, production quickly got on a track to exceed the USGS’s estimate within just a couple of years. The EIA asked for another survey, which was not completed and published until mid-2011. By then the EIA, based on its own work and that of consultants, had published a TRR estimate of 410 Tcf. It was an embarrassment therefore when the USGS, who are the science guys, came in with a mean estimate of 84 Tcf TRR, a big number, but not even a fourth of what the EIA had been carrying. The EIA massaged the USGS figures a bit—USGS had still not assumed the availability of horizontal drilling in some areas—but followed their primary reductions, which were based in part on lower quality assessments of large areas of the Marcellus, producing a final number of 141 Tcf.11

A second disquieting sign is that early wells appear to have a more rapid depletion rate than industry and EIA projections assume. The unconventional hydrocarbon industry is still so new that only a relative handful of wells have as yet produced much in the way of useful data. The Texas Barnett shale has the longest track record. An Oil & Gas Journal analysis published in late 2012 found only two shale gas plays—the Barnett and the Fayetteville—with meaningful data, along with one tight oil field—the Elm Coulee in the Bakken play.12 All three had started with high production rates but experienced rapid declines. Companies love the high initial production since they recover costs faster, but long-term recovery estimates and capitalization values assume production schedules of twenty-five to thirty years. If the few early decline rates turn out to be representative, total recoveries would be only about half of the current estimates. Combining that with the recent TRR reductions by the EIA suggests that the energy boom would be of far shorter duration than currently imagined—twenty or thirty years perhaps, or even less.

While disappointments are not impossible, those data are only straws in a sandstorm, and it’s far too soon to attach much significance to them. Unconventional gas and oil exploitation is a brand new industry that has already run far ahead of the expectations of even a decade ago, and only a tiny percentage of potential drilling opportunities have been actively explored. Witness the several new announcements over the past year. Drilling technology is still evolving rapidly, and there is no warrant for assuming that early recovery efficiencies won’t be improved upon, or that the engineers won’t learn to exploit areas that appear relatively unattractive today. The EIA and other forecasters freely concede that their forecasts are the grossest of approximations that will necessarily require frequent large revisions. Perhaps the best indication of the reality of the opportunity is that the oil majors—ExxonMobil, Shell, Chevron, Marathon, and others—are jumping in with both feet, not only starting their own production sites but buying up ones already developed by smaller companies. They are also champing at the bit for permits to spend up to $100 billion or even more to build the massive projects required to support the export of natural gas (see Chapter 2). The oil majors are among the most experienced energy companies in the world, and they have clearly sized up the opportunity and made their own very positive assessments. While the growing presence of the majors may raise concerns about future cartelization of the industry, it eases worries that it is merely a swamp-gas will-o’-the-wisp.

The most recent research, published just as this book was going to press, is an impressive new study from the Bureau of Economic Geology at the University of Texas at Austin. An assessment team collected complete production and geologic records from all 15,000+ wells that had been sunk on the Barnett shale by the end of 2010. Combining the actual production records with a new geology-based production model to project the output of new Barnett wells, the team concluded that actual production would be in a mid-range between the most optimistic and most pessimistic assessments—in other words, much like current EIA forecasts. Further, they scotch fears expressed by some that all the “sweet spots,” have already been tapped. At least in the Barnett, it looks like there is a lot of good rock left. All of it is bracing news for the industry. By end of 2013, the team will extend the study to several other shales, including the critically important Marcellus.13

But what if the worst case scenario comes true, and the shale boom lasts only twenty or thirty years? The golden age of American manufacturing is often placed in the very prosperous postwar period of about 1948–1968—only twenty years. We shouldn’t turn up our noses at another twenty-year run like that.

![]()

THE “OTHER” UNCONVENTIONAL HYDROCARBONS

Coalbed Methane

Large amounts of methane are trapped in coalbeds. Coal is porous and adsorbs (attracts) methane. Since concentrated methane is explosive, miners long ago developed methods for draining the methane from mines, often by drilling vent holes. The large-scale capture and reuse of the methane is a more recent development, at least outside of Germany, which began capturing coalbed methane some forty years ago. Australia, China, and the United States are now all extracting coalbed methane in commercial quantities. Unlike shale gas, coalbed methane contains few liquids, so its production has shrunk with the current low prices for dry gas. There are multiple techniques for extracting methane from coalbeds, some of which involve fracturing and lateral well drilling, much as in shale gas operations, although the majority use other methods, which may involve vacuum pumps and boreholes, and occasionally even blasting. Unlike shale plays, extracting methane from coal mines usually produces water. Water builds up in coal seams, and must be cleared to release the methane. Water recovered from coalbeds is typically highly toxic and requires careful handling. Coalbed methane production, at about 2 Tcf annually, accounts for about 10 percent of US dry gas production. The EIA forecasts that its production will fall slowly through 2035.14

Oil Sands

Oil sands are sand formations infused with bitumen (oil tar) a heavy, extremely viscous hydrocarbon that does not flow at normal temperatures. Oil sands are widely distributed and represent a potentially vast store of energy. Currently, the major development is concentrated in the Alberta province in western Canada. Shallow oil sand deposits are removed by strip mining techniques (using some of the largest power shovels in the world) and treated in separation centers using water and caustic chemicals to separate the bitumen from sand and other waste. Deeper deposits are treated in situ, by pumping superheated steam and chemicals into the sands, melting the bitumen, so it can flow out from the sands. Bitumen-derived oil is heavy and sour, but with additional processing, it can be converted into the light, sweet, oil preferred for transportation and other big-market applications. But extraction and processing, which often involves mixing the processed bitumen with conventional petroleum products, is expensive and energy-intensive, while the affinity of bitumen for heavy metals and other toxic substances imposes complex and expensive treatment issues. Alberta produces about 1.5 million barrels of high-quality oil a day. Production levels may not be sustainable in the face of a glut of Canadian oil, due to a backup in transportation facilities. The controversial Keystone XL pipeline, held up by the Obama administration, is key to ending the glut, by moving the oil to Gulf Coast export facilities. The cost of oil sands production may rise to unacceptable levels as the industry moves beyond the most readily accessible production fields.15

Oil Shale

Oil shale is a sedimentary rock in which rock-like particles of kerogen—the source organic hydrocarbon—is bound tightly within quartz, limestone, or other rock forms. (The industry uses the term “tight oil” to distinguish oil-bearing shale or sandstone from “oil shale.”) Conceivably, it is the most abundant, if one of the least accessible, forms of hydrocarbon. Rough estimates are that there are some three trillion oil-equivalent barrels of oil shale in the world (some estimates are much higher); two-thirds are in the United States, primarily in the Green River and Piceance Basin formations in the Wyoming and Colorado Rockies, with a substantial portion of them on federal lands. The United States authorized the commencement of several research, development, and demonstration projects during the George W. Bush administration, which have since been revised under the Obama administration. Two awards have been made on 160-acre demonstration tracts, one to ExxonMobil and one to National Soda Inc., a Colorado firm. Each of them will use in situ methods, which are viewed as more environmentally sound than mining the rocks for reprocessing in surface plants. The two are using different processes, but each involves heating the subsurface target rock until it reaches a liquid state and then separating the kerogen with techniques that are analogous to, but more complex than, typical unconventional technologies. Production from oil shale is either not included at all or assumed to produce little usable product in the major energy near-term forecasting programs.16

_____________

* The industry uses a 6:1 ratio (or 5.8:1 or similar ratios) to convert gas measures into barrels of oil equivalent. One thousand cubic feet of gas (at a specified temperature and pressure) has the same energy value as a sixth of a barrel of oil. It is at best roughly right, since various oils and gasses, depending on their sources and processing, have quite different energy values.

* The ten listed are drawn from throughout the top twenty names in a shale drilling exchange-traded fund (ETF). Information is from company reports; financial information is from the most recently filed 10-Ks.

* The EIA uses two definitions of inground supplies of energy—proved reserves and technically recoverable resources (TRRs). Proved reserves are those that the data suggest “with reasonable certainty” can be recovered from known reservoirs “under existing economic and operating conditions.” TRRs add resources that can be recovered with current technology without regard to economic or operating conditions.