While evening gowns feature much more prominently in fashion histories than do prosaic, everyday garments, the ordinary occasionally gets its due. In Why Women Wear Clothes, C. Willett Cunnington observes that ordinary garb may, paradoxically, facilitate social recognition:

Surely that is the absolute finality of fame, to cease to be a Person and to become a—thing; from having been the Duke of Wellington to turn into—a pair of boots. And of all these curious names attached to wearing apparel the student, after laborious researching, finds that some never had corporeal existence but were only fictitious characters drawn from books and plays. To add to his confusion he finds that proper names have been attached not merely to actual garments but also to styles and methods of construction….

There seems no logic in the selection of such names as have been thus transfigured. Galoshes and mackintoshes, both made of a similar substance, suggest two eminent Scotsmen; but you will search in vain north of the Tweed—or elsewhere—for a “Mr. Galosh.”1

This playful meditation on the naming of garments after people (or fictional characters) suggests that becoming a thing, in Cunnington’s terms, need not be an alienating process. Wellington and Charles Macintosh have had their legacies enhanced through clothing that serves as material futurity, one in which ubiquitous, workaday attire points (however obliquely) to the men whose careers inspired it. The vagaries of naming might be confusing for “the student,” as Cunnington modestly calls himself, but they do not confound or shame the person who has become the thing. No doubt these men hoped to leave a more prepossessing inheritance, but their fame is partly secured through the garments they wore or designed.

Contrast Macintosh, however, with characters who become his thing in novels of the early twentieth century. In the “Hades” episode of James Joyce’s Ulysses, the reporter Joe Hynes takes down the names of those who attend the funeral of Paddy Dignam. Hynes asks Leopold Bloom,

—do you know the fellow in the, fellow was over there in the…

—Macintosh. Yes, I saw him, Mr Bloom said. Where is he now?

—M’Intosh, Hynes said, scribbling, I don’t know who he is. Is that his name?2

The mysterious figure, henceforth known as M’Intosh, appears throughout Ulysses, known only by the coat that confers a spurious identity. The character’s personal history is seemingly a tragic one: he eats dry bread, a clear sign of poverty; he purportedly “loves a lady who is dead,” a mark of mourning and loneliness; and he is identified by medical students as suffering from “trumpery insanity,” a sign of ill-health.3 Joyce’s M’Intosh is no man and unmanned throughout Ulysses, a perambulating reminder of the fragility of individual identity when a person becomes a thing.

At the opposite cultural pole of Ulysses, one finds P. G. Wodehouse’s short story “Jeeves and the Dog McIntosh” (1930), in which Bertie Wooster takes care of his Aunt Agatha’s beloved Aberdeen terrier. Wooster’s canine charge is accidentally given away, but his indefatigable valet, Jeeves, manages to substitute another terrier in his place. As Jeeves explains, “One Aberdeen terrier looks very much like another Aberdeen terrier, sir.”4 To put it another way, one McIntosh looks much like another. In quite different ways, Joyce’s and Wodehouse’s texts emphasize the ubiquity of the mackintosh and of the creatures associated with the coat. Instead of reaching “the absolute finality of fame,” M’Intosh and McIntosh find themselves de-particularized through the mac. Becoming a thing, such novels imply, can be much more alienating than Cunnington suggests.

In novels targeted at a variety of readerships, the mackintosh, under its various incarnations, repeatedly turns persons into things. It foments loss of individual identity; it cloaks the unscrupulous, deadly, and cruel. Moreover, the mac seems to have a bull’s eye on it, protecting against the elements but attracting the violence of technological warfare. It turns people into units—particularly into uniform entities like soldiers—and into corpses, and it is therefore associated with forms of commemoration. The irony of such activity is increased by the garment’s very ordinariness; it was commonplace on the streets of major cities and in the wardrobes of people of all conditions and histories. Although the mackintosh was commercially and popularly aligned with positive traits—including technological innovation, protection, value, and perseverance—writers of the period persistently animated it as enacting violence, anonymity, and the paralysis of characters dwarfed by economic and social structures they could not transcend. While the evening gown demonstrates the way that a bespoke item became acutely problematic in light of changing gender norms, the mackintosh suggests that writers were equally troubled by a mass-produced garment that turned persons into things, making individuals indistinguishable from one another. Evening gowns could and did shame when their wearers failed in bids to achieve singularity, when they failed to become unique and ideal objects; wearers of the mackintosh, I will demonstrate, could seldom aspire to the singular and instead became themselves undifferentiated and threatened material.

Literary scholars have examined representations of the mackintosh in individual novels and have explained what the garment signifies about particular characters, the limits of interpretation, and the social and ethical dimensions of each work.5 In contrast, this chapter looks at macs across a spectrum of fiction to demonstrate that this most British of garments came to signal the power of clothing to gather connotations and to foment outcomes that individual wearers could seldom control or manipulate. If we consider the mac through the lenses of industrial and military history, children’s literature, fashion columns, and advertising as well as novels, it becomes clear that the garment was either too innocent or too guilty for an adult to wear. The mackintosh became a mute participant in histories of industrial production and class divisions, in assumptions about which types of people could act on individual volition, and in a historical cataclysm that, until World War II, was unprecedented. Given the presence of the mac in such locations, it is little wonder that writers deployed it as a symptom of—and, eventually, that it became a kind of shorthand for—negative qualities and narratives.

Before turning to a brief biography of the mac, I want to clarify my use of the term throughout this chapter. I subsume a number of words under “mackintosh,” including “raincoat,” “trench coat,” “weather all,” and “mackintosh” proper, in part because Charles Macintosh was the first commercial maker of the garment, and the word thus became the British catch-all term for raincoats. According to the OED, the mackintosh was “originally: a full-length coat or cloak made of waterproof rubberized material. Subsequently: a rainproof coat made of this or some other material.”6 Manufacturers and retailers did not always differentiate between different kinds of raincoats; the Harrods General Catalogue of 1928/1929, for example, does not distinguish between coats made of different textiles, indexing and identifying all raincoats with the term “mackintosh.” The OED demonstrates the word’s universalizing function with an example from Noblesse Oblige: An Enquiry into Identifiable Characteristics of the English Aristocracy that follows the definition of “mackintosh”: “Burberry and raincoat are of the same genre, macintosh or mac being normal.” In Noblesse Oblige, a footnote to this definition reads, “This use of Burberry no doubt arose because, even before 1914…this was a good and expensive kind of macintosh.”7 This description explains the use of differing terms as an attempt by manufacturers and consumers to assert and maintain class hierarchies in the face of the garment’s ubiquity, but “mac” was considered the “normal” term for a waterproof garment.8 There was, however, nothing “normal” about this garment’s deployment in a range of literature, which collectively uses the coat to think about the associations between, and blending of, persons and things.

Making the Mackintosh

The commercial history of the mackintosh indicates why negative connotations would gradually accrue to a garment that was (and is) quintessentially British. Charles Macintosh (1766–1843) invented a means of waterproofing fabric and patented it on June 17, 1823. Macintosh’s process involved sandwiching rubber, softened by naphtha, between layers of cotton cloth.9 Although the coats succeeded in keeping out water, they were unattractive and uncomfortable. Nineteenth-century macs were a drab green, long and shapeless, and hard to maneuver. The original material could not be tailored closely to the body because the rubberized fabric did not breathe, and a tight-fitting mac was a prescription for perspiration.10 The coats themselves also smelled unpleasant. As early as 1839, “The Gentleman’s Magazine remarked that ‘a mackintosh is now become a troublesome thing in town from the difficulty of their being admitted into an omnibus on account of the offensive stench which they emit.’ ”11

Mackintoshes were unique in that they were an early artifact of British mass-production. In a period when most street clothing and outerwear was either home- or custom-made, the production requirements for macs, which had seams that necessitated chemical proofing, meant that “the mackintosh industry was one of the first clothing trades to be substantially carried out in factories.”12 Workers made individual parts of the garment, which was then assembled elsewhere on the premises, rendering the mackintosh a pre-Fordist exemplar of mass-production. Because they were not made to measure for individual customers and were manufactured far away from where they were bought and worn, mackintoshes foreshadowed the eventual popularity of “ready-to-wear” clothing. The coats were thus an emblem of modernity, but they were also marked by a lack of exclusivity, as mass-production rendered mackintoshes inexpensive. In 1893, the India Rubber Journal asserted, “Now the servant girl out of her slender means can procure a really stylish and serviceable waterproof for a mere trifle.”13 Manufacturers and servant girls were no doubt pleased that the coat had become so affordable, but such comments led to a growing sense that mackintoshes were cheap, and thus second-rate, articles.

The mac was a particularly British garment, in both its construction and its manufacture. Early in the coat’s development, it became traditional to line the mackintosh with tartan cloth; as Sarah Levitt explains, “There was a fashion for all things Scottish” in the nineteenth century, and tartan linings “were especially appropriate in view of Macintosh’s Caledonian Origins.”14 The coat continued to reference its national genesis—a British, if not English, patrimony—long after the vogue for tartan faded. Such linings persist in contemporary mackintoshes (as most Burberry advertisements make plain) and remain an oblique reminder of the coat’s origins. Moreover, even though the American Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company developed its own version of the mac, in the early twentieth century “the entire British production supplied ninety percent of the world market.”15 British domination of what we might call the mackintosh sector means that the coat was and is aligned with a specific national identity; even today, British brands like Traditional Weatherwear (the descendant of Macintosh’s original operation) remain popular in overseas markets because a British mac is “the real thing” according to many consumers.16

The first—and, over the long term, best—customer for the mackintosh was the British Army. When other manufacturers entered the market with different means of waterproofing cloth, they too found the army to be their best market. Ordinary soldiers wore mass-produced mackintoshes, but officers wore Aquascutums during the Crimean War and, later, Burberry waterproofs.17 These companies offered tailor-made mackintoshes, but the cut and color of the garments they produced followed military specifications, making the coats of the officer class visually uniform. Even as the quality of a mac quietly expressed its wearer’s social and economic status, the coat became a de-individuating garment worn by members of an institution that functioned because of group behavior, experience, and history. The mac thus substantiates Georg Simmel’s argument that clothing can amalgamate individuals: “[S]imilarly dressed persons exhibit similarity in their actions.”18 While Simmel contends that fashion simultaneously facilitates “individual accentuation and original shading of the elements of” stylish garb,19 the mac’s utilitarian nature (and largely unfashionable history) rendered, as we shall see, individuality and originality extremely difficult.

It is illuminating to contrast even the upscale mac with the evening gown; while both garments were made to measure and costly, the synthesis of “having” and “being” that Simmel theorizes as characteristic of evening finery could only with difficulty pertain to a Burberry or an Aquascutum coat. A consumer would know that he had bought an expensive garment, but the casual observer might not. A comic story in Punch hinges on this very point. In “Personal,” the narrator offers an account of her purchase of a “McIntosh,” the product of “the celebrated British firm” that costs “the extra guinea.” After she has the coat repaired, she is dismayed to discover that an unscrupulous tailor removed the McIntosh tag and sewed it into another raincoat, which promptly sold on the strength of the label. “Personal” thus suggests that the difference between a “McIntosh” coat and a cheaper garment is not always visible.20 One mackintosh seemed very like another, and the coat thus helped to construct British masses, whether they were soldiers, officers, “servant girls,” or simply ordinary consumers.

Early advertisements for the mackintosh tended to promote it to two types of consumer: sportsmen (and, to a lesser extent, women) and servants. In other words, the upper echelons of British society would wear their macs while participating in extraordinary leisure activities, while those in the working class would wear the same raincoats while performing their ordinary, workaday jobs. During the nineteenth century, Macintosh touted its waterproofs as a necessary implement for the sporting life, particularly for dangerous sports. In an advertisement published in the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News in 1890, a man and a woman wear the coats while yachting in rough seas.21 This advertisement was no doubt intended to display the protective qualities of the mac—the couple is endangered but not wet—but it paradoxically aligns the garment with exciting pastimes that verge on the perilous.

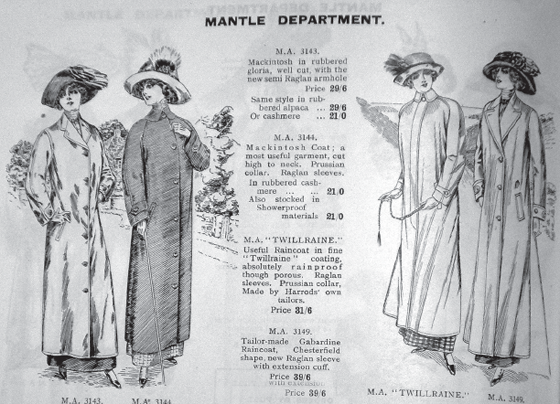

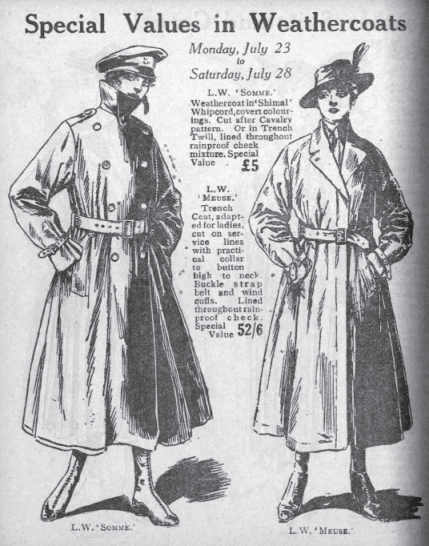

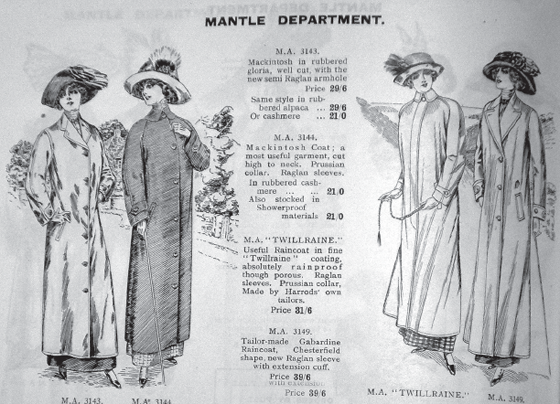

If members of the yachting class wore mackintoshes when in danger of being washed overboard, they purchased these garments for their servants to wear when occupied in the routine tasks of driving carriages, opening doors, and carrying packages. Early Harrods catalogs depict mackintoshes as suitable for coachmen and footmen. While thus attired, they could escort their employers around town with the sheltering aid of umbrellas. These catalogs make plain why no woman of fashion would have worn a mackintosh when paying calls or going to evening entertainments: in 1912, the coats were still voluminous, chin-to-foot affairs (figure 2.1). Before the war, the coats were thus associated with the military, sports, and the working class. They were utilitarian garments that were connected mainly with de-individuating activities such as army or household service. They were appropriate for select leisure activities, but in contrast to the evening gown and to fancy dress, they positively interfered with making a distinctive, stylish appearance.

Sartorial Shorthand: The Mac, Children, and Poverty

In literature of this period, writers consistently align the coat with sport and protection but also with de-individuation. These qualities emerge most clearly in books written for children, who, like servants and soldiers, do not choose what they wear, and in depictions of working-class characters, who are treated as objects by those higher up on the social scale. Both groups are clothed in macs for pragmatic reasons, but when adults wear the coats, the garments come to represent—and even to invite—a peculiar form of non-progression. These depictions of mackintoshes suggest that the coat became a trope to neatly figure the circumscription of personal choice by age or class. If the evening gown rose (and, as we have seen, often fell) because of the range of choices it mobilized, the mac renders adults a thing by highlighting a lack of choice: it turns a human subject into a type, an object that does not exercise agency and can be dealt with by more fortunate others.

For children, the mackintosh poses few problems. Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Mr. Jeremy Fisher, a sequel to her famous The Tale of Peter Rabbit, depicts the mackintosh as sound garb and, in fact, as nothing short of life preserving. In Potter’s illustrated story, the title character, a frog, dons a mackintosh before going out to fish in the rain. The mac would have been regarded as appropriate sporting wear, so this choice seems unremarkable, a specific instance of Potter’s general tendency to dress her animal protagonists in human clothes.22 As the tale progresses, predator becomes prey, and a large trout swallows Fisher. Lest Potter’s young readers fear, however, the narrator quickly reassures them: “[T]he trout was so displeased with the taste of the macintosh, that in less than half a minute it spat him out again.” Fisher then pulls himself out of the water, “his macintosh all in tatters.”23 Potter pairs this description with an illustration that depicts the mackintosh with vertical tears, perhaps caused by the trout’s sharp teeth. Although Potter avoids overt moralizing, the lesson of the tale seems clear: when venturing out, children should listen to adults and wear a mackintosh. It will protect them from rain and, perhaps, the larger dangers of the natural world.

The valorization of the utilitarian mackintosh for youth was reflected more broadly in illustrated newspapers of the early twentieth century. Older children wearing macs were depicted as having the plucky resolution to “carry on” in the face of Britain’s notoriously wet weather. The Sunday Pictorial of November 21, 1926, included a photograph captioned, “Modern Gumboot Girls Don’t Care: They Despise Rain’s Dreary Drip.” The accompanying text reads, “Rain doesn’t frighten the modern girl—she just puts on [a] sensible raincoat and gumboots and ‘doesn’t care if it snows.’ Here is a typical group at the women’s hockey match.”24 Although the individuals pictured could be young women, the newspaper twice calls them “girls,” a term that emphasizes youth, sport, and a cheerful attitude. Such news items, together with Potter’s The Tale of Mr. Jeremy Fisher, frame the mac as eminently practical when worn by children or young adults. Fisher experiences a violent attack while wearing it, but the coat shields him from harm. More prosaically, the “gumboot girls” are protected from rain and snow. This protective quality, however, vanishes in representations of the mac worn by adults, who purportedly enjoy freedom of choice when it comes to attire. A practical coat becomes an object that de-individuates, a coat that only adults enslaved by common sense, and unable to be more subject than thing, would wear.

Rebecca West’s novella The Return of the Soldier, for example, uses the mackintosh as shorthand for one character’s poverty, which motivates her sartorial choices. In West’s book, a British officer, Chris Baldry, forgets his adult life as the result of shell shock. His cousin Jenny, the novella’s narrator, enables Baldry’s daily visits with Margaret Grey, a woman living in suburban poverty whom Baldry loved in his youth. Grey’s appearance is marked by her continual wearing of a “yellowish raincoat,” which leads Jenny to reflect, “It would have been such agony to the finger tips to touch any part of her apparel.”25 Grey seems relatively untroubled by her appearance—if she recognizes her dowdiness, she is used to it—but the upper-class women in the book project characteristics and emotions such as “unpardonable” and “sick” onto her mackintosh.26

Grey’s raincoat deftly captures her poverty and personal limitations, and through Jenny’s descriptions and diction, West neatly illustrates the snobbery of her well-meaning narrator. According to Jenny, Grey “was repulsively furred with neglect and poverty, as even a good glove that has dropped down behind a bed in a hotel…is repulsive when the chambermaid retrieves it.”27 Later, Jenny describes Grey as “not so much a person as an implication of dreary poverty,” a characterization that evacuates Grey’s persona and history and makes her (and her coat) a perambulating, degraded figure for the class that would have been excluded from the luxurious world of Baldry Court before the war.28 Like the glove that Jenny uses to signal Grey’s physical decay, the yellowish mackintosh becomes “unpardonable” in part because it is out of place. As a result of the disruption caused by World War I, such dismal objects invade the world of the upper class, where servants might wear such garments but not visitors to the house.

While West clearly aligns the mackintosh with the dreary practicality that poverty necessitates, she also uses the garment to illustrate how upper-class women view those below them on the economic scale. The mackintosh prevents Jenny from perceiving Grey as an equal or, indeed, as human. During her most positive assessment of Grey’s appearance, the narrator comes to see her shabbiness as akin to “the untidiness of a child who had been so eager to get to the party that it had not let the nurse fasten its frock.”29 Jenny’s (or, rather, West’s) choice of the word “it” instead of “she” is tactical: even though Grey displays superior understanding toward the end of the novella, her appearance and being are figured as less than fully feminine—indeed, as nonhuman—because of her mac.30 In fact, the coat may be the cover that allows Margaret and Jenny to kiss (in the novel’s famous line) “not as women, but as lovers do”;31 like the evening gown, the mackintosh has the power to queer those who wear it, subsuming gender and sexuality, however temporarily. At the end of the novella, when Baldry recovers his memory, Grey is reduced to a “figure mothering something in her arms.”32 She will have to return to her life of respectable poverty, a “figure” instead of a person. West’s depiction of the yellowish raincoat constellates the mac with poverty and the ontological slide from person to thing. The mac works to anonymize and serialize Grey, an activity it will perform in novels throughout the next two decades.

Twenty years later, in his novel Brighton Rock, Graham Greene’s murdering main character (alternately identified as “Pinkie” or “the Boy”) watches as Rose, an impoverished waitress, approaches. Pinkie arranges to marry Rose after the unwitting young woman witnesses events that could incriminate him; Greene’s male protagonist has no affection for his future wife—indeed, for anyone—and plans to kill her after he covers up a previous murder. As Pinkie “watched the girl as if she were a stranger he had got to meet,” the narrator observes that Rose “had tricked herself up for the wedding, discarded the hat he hadn’t liked: a new mackintosh, a touch of powder and cheap lipstick.”33 In this brief description, Greene makes evident Rose’s desire to please her future husband. Her “touch of powder and cheap lipstick” signal an attempt to appeal to him even as they underline her poverty and unfamiliarity with makeup. It is, however, her “new mackintosh” (worn to a wedding!) that economically communicates her lack of style, impoverished state, and increasingly endangered position.

As Rose walks toward her future husband, the narrator observes that she has “tricked herself up” in the new mac. This phrase points to Rose’s conscious decisions and actions—to her self-conscious effort to dress as well as possible. Greene’s narrator, however, quickly shifts away from Rose’s agency to how others, particularly Pinkie, see her: “She looked like one of the small gaudy statues in an ugly church: a paper crown wouldn’t have looked odd on her or a painted heart: you could pray to her but you couldn’t expect an answer.”34 Greene’s language positions her, both for the reader and for Pinkie, as a tacky object; in figuring Rose as a statue, Greene strips her of movement, speech, and all trace of human agency. In her mac, she becomes less young woman than thing. This kind of process echoes Barbara Johnson’s observation that “a person who neither addresses nor is addressed is functioning as a thing,”35 a form of being that becomes clear as Greene’s novel continues. Later, when Pinkie’s lawyer asks, “And what is the little lady thinking?” it comes as no surprise that “she didn’t answer him.”36 Rose remains silent after the wedding, letting her new husband speak for her and dictate her actions.

Although, in contrast to Margaret Grey, Rose is not regarded by upper-class characters, she is viewed through the lens of working-class men who consider themselves superior to her female sex, innocence, and greater poverty. Her mackintosh, like Grey’s raincoat, becomes a focal point for human subjects who want to deal, not interact, with her. The mac thus captures and communicates an atmosphere of limited horizons, of problems of economic privation so acute that the poor seem less humans than objects. This type of representation of the coat remained prevalent right up to the outbreak of World War II. As late as 1939, George Orwell’s Coming Up for Air aligns the mackintosh with the domestic hardships of the lower-middle class. At the conclusion of Orwell’s novel, the protagonist, George Bowling, returns to a home pervaded with and characterized by the odor of the coat: “I fumbled with the key, got the door open, and the familiar smell of old mackintoshes hit me.”37 Bowling is soon enveloped in a spat with his wife, Hilda, and in the novel’s final pages, the character (who also serves as the novel’s narrator) returns to the smell of mackintoshes four times. Although no one in the scene wears a mac, the garment suffuses the family home, suggesting that the coat not only is a discrete object but confers a diminished way of being. As Bowling bids goodbye to the political speculation and the nostalgic memories of his childhood home that have consumed him for most of the novel, he concludes, “The old life…was fading out, all fading out. Nothing remained except a vulgar low-down row in a smell of old mackintoshes.”38 Here, the mackintosh does not turn a specific character into a thing, but Orwell’s novel suggests that the coat comes to stand for the kind of life that Bowling and his ilk lead—the “common man’s [and woman’s] passivity and helplessness.”39 Along with West and Greene, Orwell implies that the mackintosh somehow infiltrates the homes, lives, and persons of those who live in or near poverty; instead of a garment that one might put on and take off, the coat creates an atmosphere in which characters find their choices so restricted that they hardly seem—or feel—like agentic beings.

Such examples deploy the mac to express the lack of choice faced by particular characters and, in Orwell’s novel, in particular settings. The coat becomes a way to represent, and thus to think through, the de-individuating experience of poverty in Britain, which renders characters passive and vulnerable to the actions of others. Surprisingly, when an author places the garment on a privileged character, the coat’s evacuation of agency similarly pertains. In The Last September, Elizabeth Bowen’s novel about the waning days of the Protestant Ascendancy, the mackintosh at first seems simple and utilitarian. Lois Farquar, the young British ward of Sir Richard and Lady Naylor, wears the coat when driving and walking in the rain.40 Because Lois is on the brink of coming of age, childish apparel seems appropriate. That she wears a mackintosh in the Irish countryside, and while driving and walking, also makes her seem to be properly attired, given the coat’s history as a garment worn for sport.

As the novel continues, however, the mackintosh signals a kind of arrested development in its protagonist and the society that she represents. As Jed Esty has noted, Bowen’s novel depicts Lois’s “balky nonprogress to adulthood” and portrays her as “frozen in her youth, stuck between cultures, hopelessly virginal.”41 Glamorous and mature characters, such as Marda Norton, get drenched in rainstorms and are chastised for going out without a mackintosh.42 Marda, who moves into adult society and married sexuality when she leaves the Naylors’ home, is the kind of character who does not wear a mackintosh; Lois, on the contrary, wears a coat that protects her from the rain but also embodies her lack of (hetero-)sexual passion and her refusal to become, or act as, an adult.43

In contrast to the childish mac that Bowen’s “overgrown juvenile” wears, soldiers and Irish insurgents in her novel wear trench coats. This distinction, which is unique to Bowen, serves to highlight the contrast among the moribund Protestant Ascendancy, British soldiers, and Irish nationalists. Unlike Lois and the others in her set, characters in trench coats are purposeful; early in the novel, Lois hears “branches slipping against a trench-coat. The trench-coat rustled across the path ahead to the swing of a steady walker. She stood by the holly immovable…and there passed within reach of her hand…some resolute profile powerful as a thought.”44 The figure is unidentified, abstracted to the point that the coat alone seems to take action. Although a human body wears the coat (there is a profile), garment and wearer are inextricable, assembled as one thing. “It must be because of Ireland he was in such a hurry,” Lois speculates; the trench coat thus underlines the abstraction of individual identity under the politicized violence dividing the country, where it is the cause (and not the man) that matters.45

The novel does not specify which side of the struggle this ghostly figure supports. Although Lois suspects that this trench coat cloaks a rebel, Bowen’s novel pointedly depicts armed men—or, rather, armed coats—on both sides of the conflict. Later, Lois encounters another animated object: “[A] trench-coat flickered between the trees, approaching.”46 On this occasion, the man wearing the coat is particularized as Gerald Lesworth, a British soldier, but the coat moves and acts before Lesworth does. Indeed, Lois initially stares in the direction of the coat, unable to differentiate between Irish insurgents and British soldiers from a distance. A great deal rests on this distinction, given the violent attacks that take place at the novel’s periphery, but through the trench coat, the novel constructs both soldiers and rebels as more alike than different. The soldiers and the insurgents are militarized, armed, and capable of violent acts. And both groups dispossess the Anglo-Irish: the insurgents bury guns on estate property and burn the great houses, but the soldiers constitute an “army of occupation” and are not entirely welcome. As Sir Richard opines, “This country…is altogether too full of soldiers.”47 Or, to follow the diction that Bowen uses elsewhere, it is altogether too full of trench coats—of men who function as things instead of as individuals.

Bowen’s novel thus demonstrates the different ways the mackintosh transformed persons into things in the 1920s. In The Last September, the mackintosh confers a juvenile innocence, a child-like passivity, onto a character who might put on other garments and qualities. While West’s, Greene’s, and Orwell’s characters cannot afford better outerwear, a woman of Lois Farquar’s class could make different sartorial choices, and Bowen uses the coat to figure her protagonist’s shortcomings. Arrested development is not the only quality put on with the mackintosh in The Last September, however; the coat also confers the anonymity inherent to military service. If they do not always efface the particular identity of individuals, mackintoshes trouble that identity by blurring distinctions between persons and even between the opposing factions of British soldiers and Irish insurgents. Although Lesworth briefly rises above his coat to exercise a degree of individual agency, the irony of The Last September is that readers have always known him to be on the losing side of the struggle the book represents. When Bowen’s novel was published in 1929, the anonymous insurgents had already secured their aims with the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922. The book thus suggests that it is occasionally better to be a thing than a person: the anonymous, resolute coat (unlike Lesworth and the other British soldiers in the novel) walked steadily to independence.

The Mackintosh at War

Bowen’s use of the mackintosh in The Last September reflects her historical position, writing in the decade after the end of World War I. When macs were tailored and marketed for use at the front during the war, the biography of this garment took a dramatic turn; although waterproof coats had long been worn by soldiers, they had never been as ubiquitous—or as abundant—as they became between 1914 and 1918. One of the necessary items in any officer’s “kit” was the trench coat, a long belted mackintosh cut differently for each branch of service.48 Ordinary soldiers and female volunteers also wore such coats, though the cut and quality of individual examples varied, depending on the wearers’ financial wherewithal.

The pervasive presence of trench coats during the war is well known, but at our historical remove, it is difficult to imagine the visual impact of the sheer proliferation of these garments. People saw men and women in mackintoshes everywhere: in the streets, at railroad stations, and in the newspapers. On December 24, 1916, for example, readers of the Sunday Pictorial would have seen the photograph of a member of the Women’s Volunteer Reserve guiding soldiers, each figure attired in a mackintosh (figure 2.2). While there is some variation in appearance among the individuals, the coherence of their attire creates a group identity, one enhanced by the newspaper’s decision not to provide names for either the volunteer or the soldiers. In their coats, they could be everyman (and everywoman)—or, at least, any British citizen of a certain age in 1916.

The trench-mackintosh reached iconic status as the coat appeared in advertising for products both associated with and far removed from the war. A promotion for war bonds in the Daily Telegraph on January 10, 1918, included a line drawing of a soldier in a trench coat “standing to” that pulled patriotic heartstrings and encouraged readers to give to the cause. Similar images also encouraged people to buy prosaic consumer products. Phosferine, a patent medicine for “nerves” and general conditioning, used a picture of a soldier in a mackintosh in a July 5, 1917, advertisement in the Daily Telegraph (figure 2.3). Although the text accompanying the photograph claims that Phosferine helped Private W. G. Amatt recover from shell shock, the advertisement depicts the very environment—and garment—associated with incurring this malady. Readers of advertisements would thus have seen the coat not only associated with protection, common sense, and grit, but also aligned with shell shock, wounds, and the violence that caused them.

While newspaper illustrations and advertisements for an array of products helped to connect the mac with the war, the firms that manufactured the coats were most responsible for keeping them in the public eye. These companies targeted their marketing to soldiers and civilians, and in so doing followed a nineteenth-century advertising tradition. As Brent Shannon has demonstrated, in Victorian advertising, “the most masculine—and therefore most popular—male figures were athletes and soldiers, and their presence was used to make even ostensibly gender-neutral products masculine and appealing to male buyers.”49 Soldiers thus helped to promote consumer goods by gendering them male, but the use of soldiers in advertisements that ran during the war had an additional effect. With coats marketed to and by officers and soldiers, consumer products generated a sartorial blending of home and front. This no doubt made wearers feel that they were materially aligned with the war; as Jennifer Craik has argued, uniforms are essential when nations and cultures want to emphasize group identity.50 While trench coats were not identical, they were stylistically similar to one another and ubiquitous, thus producing a cohesive national style. In this respect, they were quite different from the evening gown: if it promised access to a singularity without limit, the wartime mackintosh offered a selfhood supported and mediated by a collective identity—a psychic structure premised less on individuation than on identification with others. To return once more to Simmel, the trench-mac demonstrates how omnipresent garments construct an “inner world” that reflects “the aspects of the external group governed by” the attire.51

The marketing of these coats helped to produce this national style by framing the same garments and makers as appropriate for both soldiers and civilians. In 1916, for example, the front page of the Daily Mail touted goods sold by Derry & Toms, including “Gentlemen’s Raincoats,” which are described as “suitable for military or civilian wear.”52 Such advertisements constructed a visual continuity between the trench and the city street through consumer goods. When Aquascutum described itself as “Military and Civil Tailors” in a Daly’s Theatre program published in September 1916, readers would not have been surprised by the proximity of military and civilian models and modes (figure 2.4). The militarized nation had a visual coherence created by clothing that aligned British bodies with one another.

Such conformity no doubt appeared unproblematic, the innocent desire of those back in Britain to model themselves on their “boys” and to look like they, too, were participating in the war effort. As Craik has argued, however, uniforms constitute one of the “central body techniques in the actualization of persona and habitus.” Indeed, Craik sees this technique as so powerful that she questions, “Do people wear uniforms or do uniforms wear people?”53 The marketing and wearing of the trench-mac conferred qualities otherwise aligned with officers and soldiers onto civilians. In retrospect, writers such as Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, Helen Zenna Smith (Evadne Price), and Dorothy L. Sayers would deploy the mackintosh to critique the militarism celebrated in such promotions; moreover, they would suggest that the coats themselves threatened the bodies and muddled the identities of those who wore them.

Each brand of military mackintosh had a range of strategies for promoting itself, but four general trends emerged during the war: firms celebrated the quality of the garments, cast the coats as suitable for all fronts and in all weathers, supplied testimonials that praised manufacturers for keeping men comfortable in the trenches, and suggested that the macs protected against all threats to the body of the wearers. In practice, these approaches often overlapped. I trace these advertising campaigns in some detail, in part because they are a component of this garment’s history—what Elizabeth Grosz calls the thing’s “ ‘life’ of its own”54—and in part to illuminate the narrative backlash against the mackintosh and its manufacturers after the war. Advertisements published in wartime aligned the coat with the very qualities, the very psychic processes, that writers would figure as dangerous in peacetime. If homogeneous appearance and protection from harm promised comfort and ease in a hostile environment, at peace, these qualities emerged as unappealing and as beacons of false promise.55

Because a number of manufacturers produced mackintoshes and trench coats, the firms vied with one another to position their garments as the best in quality. Burberry and Aquascutum, in particular, sought to create the sense that their coats were exceptional, worn by men of a certain caliber and class. Their promotional materials offer a glimpse of a world of privilege that some officers managed to enjoy even at the front. An Aquascutum ad that ran in Punch on April 18, 1917, quotes from a letter penned by an officer in German East Africa: “We are constantly having Tropical Rains, which wet one through in about two minutes. You will be pleased to hear that in spite of these awful storms, my ‘Aquascutum’ keeps me quite dry—when I am fortunate enough to have the native carriers near enough to get it.”56 This advertisement not only promotes the coat but aligns it with a class that enjoys “native carriers,” whose burdens include the Aquascutum. Unlike the mackintoshes worn by children, child-like characters, and the poor in literary works of the period, this coat is worn by those who have servants to “do” for them. In the Daily Telegraph, Burberry similarly extolled its trench coats as maintaining “the highest Service tradition in point of smartness and distinction.”57 It might seem counterintuitive that looking stylish mattered to men four years into the war, but the advertisement positions the coat as a means to the end of an elevated, upper-class appearance. Burberry and Aquascutum were, and still are, invested in promoting themselves as distinctive, luxe brands, and wearing one of their coats communicated attention to sartorial detail under trying conditions.

These ads appealed to nonmilitary personnel as well as to soldiers because they present the garments as a class apart from more utilitarian mackintoshes. Although, as I suggested earlier, observers might not know that an individual was wearing a brand-name (and not a no-name) coat, the wearer himself would know, and the label thus served as a silent reminder of individual difference in a sea of conformity. A decade after the war, Helen Zenna Smith (the pseudonym of the popular author Evadne Price) would represent this association in Not So Quiet…Stepdaughters of War. Smith’s text complements Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front (1929) through a semi-biographical narrative about English women who work as ambulance drivers and cooks at the Western Front in France. Blimey, a working-class woman, buys a Burberry with her wages, and the coat plays a significant role in her personal transformation. For Blimey, a Burberry is a mark of her new earning power and class aspirations. The acquisition of a brand-name garment demonstrates that she has improved herself and can now aim for “distinction.”

And yet, writing a decade after the war, Smith intimates that in putting on a Burberry, Blimey also puts on the generalized role of combatant. Even as the character selects a coat in a light shade to signal her individuality,58 she purchases the same brand and type of garment worn by officers and other female war workers. This choice demonstrates the effective nature of Burberry’s advertising, but the death that Smith metes out to Blimey implies that the coat materializes a particular fate along with the purported distinction it confers. The novel concludes with a horrific air raid in which bombs rain down on female volunteers as they shelter in a trench. In putting on a soldierly style, Smith suggests, Blimey also puts on a serializing identity that makes her vulnerable to a violent death. The narrator reports that “Blimey is bleeding from a wound in the arm…the blood is pouring from it.” For her part, Blimey focuses on the marring of her coat and not on her injury: “ ‘Now see wot’s ’appened to me new Burberry, all covered in blood. Now see wot’s ’appened to me new Burberry, all covered in blood,’ she keeps muttering.”59 While these words are no doubt meant to communicate Blimey’s shock as the result of a grievous injury, she focuses less on her wound (and impending death) than on the damaged commodity, which has facilitated and stands in for her wartime experience. When the narrator later reports her fate—”Blimey is unconscious from loss of blood. Her Burberry will never be any use again”60—the object’s loss of “use” stands in for Blimey’s loss of life. There is a human casualty here, but Smith’s novel marks the terminal condition of the Burberry, a strategy that demonstrates the unity of person and garment (both so much material) in total war.

Not So Quiet…Stepdaughters of War deploys Blimey’s Burberry to remind readers that the uniform identity materialized through such coats was hazardous. Although the character’s final words (or, rather, her accent) remind readers of her individual history and working-class status, the novel’s erasure of the distinction between (male) soldier and (female) cook reflects a broader truth about the way the coats were marketed. In addition to the emphasis on quality, other promotional campaigns conducted by the same firms suggest that the trench-macs erased individual identities, in part because numerous men (and women) in so many different places wore them. Advertisements thus aligned the mackintosh with the military and with the sacrifice of individuality required by military life. The marketing campaigns for trench-macs asserted that the same garment could be worn by anyone, anywhere, and thus this one coat might efface differences between the fronts, campaigns, and individuals fighting around the globe.

In these advertisements, illustrations work synergistically with text to represent the coat as universally needed and worn. In an ad in the Times on July 1, 1915, Burberry coats are said to “ensure advantages of the greatest value to Officers in France or Turkey.”61 This claim depicts the Burberry weatherproof as suitable for officers stationed on either front in any weather. The accompanying sketch shows a universalized soldier, whose face displays no remarkable features. Although he sports a small mustache, he is otherwise “any officer.” This depiction allows readers to picture themselves in a Burberry, but it also points to a disquieting truth of military service: once at the front, officers and soldiers fill a place (occupy a coat), and it does not matter who or what they were before turning up with their war kits. The repetition of advertising images underscores this de-individuation. Each manufacturer had a limited number of illustrations it used to promote its coats in a given year; while the text of ads would change, the images would not, thus further effacing individual identities.

Such pictures also standardized “praise from the trenches” that manufacturers quoted from unsolicited letters. Most of the letter writers were not identified, though the advertisements promised that original documents to support the claims were available on request. While such letters asserted individual experiences and personalities, the illustrations accompanying them served to undercut the specificity of the writer’s words. For example, a Burberry advertisement in the August 23, 1915, edition of the Times features a letter from J. K. Dunlop. Dunlop personifies his Burberry as “my best friend for some months in front of Ypres” because it both withstood “the rain and wind perfectly” and “seemed impervious to the filthy mud of the trenches.”62 Although Dunlop’s testimony is replete with particulars of his time in the armed forces, there is no photograph to complement his words. Instead, the sketch that illustrates Dunlop’s letter depicts an officer gazing stalwartly into the distance as he stands in a trench pelted with rain. The officer’s face has nothing distinct about it—he may or may not look like Dunlop—and the coat therefore seems appropriate for all officers. In other words, the Burberry promotion works to homogenize individual experiences, which helps to cast its product as a garment that any officer on the Western Front could wear, a “best friend” to one and all in the trenches.63

Advertisements that feature “praise from the trenches” effaced differences among men, assembling identity through the clad body and advancing a collective, soldierly style. During wartime, the use of a satisfied, particular consumer to speak to and for the nation’s combatants and noncombatants makes sense. As Jean Baudrillard argues, the uniform reflects “a structured, hierarchical society and seals like an emblem the ideological cohesion of a nation.”64 What is surprising, then, is that the same marketing strategies persisted after the war. In 1919, for example, readers of the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News were informed that the Aquascutum coat “kept out the rain during the blizzard at SUVLA BAY.”65 In postwar Britain, when ideological agreement was less consistent and widespread, dissident writers would seize on the garment as a sign of cohesion gone wrong.

During the war, the mackintosh could already be seen to track the costs of militarism. The collective struggle in which the coat displayed its merits was obviously a dangerous one. Because service at the front was uncomfortable and life threatening, the manufacturers of trench-mackintoshes touted the protective qualities of their coats. Burberry’s advertisements must have been seductive, allowing consumers to fantasize that the right purchase might somehow help them beat the odds. The firm promoted its trench coats with language that casts the garments as a kind of armor. In an advertisement in the Times on July 16, 1915, for example, Burberry extolled its “Military Weatherproof” as “ALL-PROTECTIVE, no matter what the weather—rainy or cold, warm or temperate.”66 Although the immediate context for this claim is the weather, the advertisement suggests that the coat could protect against other dangers. Readers are told that the Burberry mac “ensures healthful security and comfort under each and every condition,”67 a statement that, in retrospect, seems naïve about the conditions of trench warfare. As the war went on, Burberry dropped the “ALL-PROTECTIVE” claim, but other marketing campaigns contained similar rhetoric. On July 2, 1917, the Daily Telegraph published an advertisement that asserted, “From every front—from soldiers fighting in the desperate battles of France and Flanders, beneath the sweltering sun of Palestine and Mesopotamia, amongst the wind swept Balkan mountains, and in the miasmic depths of African jungle—comes the same consistent story of the perfect protection afforded by the Burberry.”68 This ad appears to acknowledge the difficult, and even deadly, conditions experienced by men at the fronts, but it promises “protection” in a context that covers not only weather but also “desperate battles.” Purchasing and wearing a Burberry enabled consumers to materialize their wishful thinking. Buyers must have known that the coat could protect against only wet, dirt, and wind, but the desire for “perfect protection” against all threats was no doubt appealing.

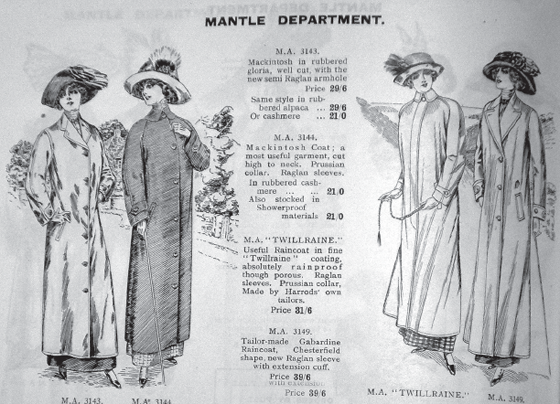

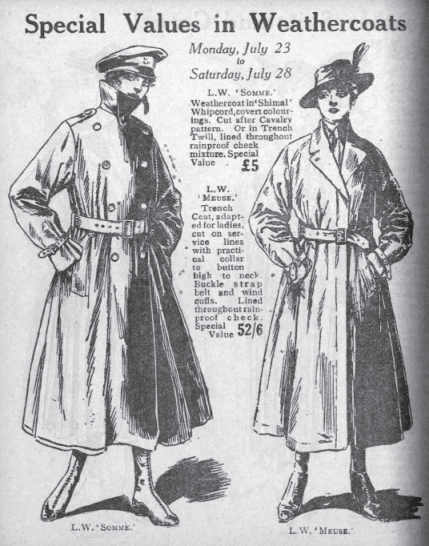

Such advertisements made claims that would, over the course of time, come to seem incredibly disingenuous. And yet, other companies similarly promoted garments in terms that are shocking to the contemporary sensibility. The Harrods Weekly Price List for July 23–28, 1917, offered “Special Values in Weathercoats” named after battles. Both the “Somme,” which was “cut after Cavalry pattern,” and the “Meuse,” a “Trench Coat, adapted for ladies, cut on service lines,” were offered at sale prices (figure 2.5).69 When one recalls that the Battle of the Somme, which was fought between July and November 1916, resulted in over 1.5 million casualties, and that Meuse is the department in France in which the Battle of Verdun (or “Meuse Mill”), also fought in 1916, took more than 250,000 lives, it seems incredible that a company would name coats after two of the bloodiest campaigns of the war. At the time, however, such names must have functioned like the “ALL-PROTECTIVE” claim; until people achieved historical distance from the war—a process in motion in the 1920s, when many novelists represented mackintoshes—such names and claims must have signified a determination to “carry on” despite the grim losses at the front. Advertisers banked on the emotional appeals of affording protection and of participating—if only through consumption—in the war effort. As Camilla Loew writes in her analysis of war posters, World War I was the first conflict in which women “had a right to…claim their experience as a part of war.”70 Harrods mackintoshes went even further and allowed women to wear the war: to lay claim to a kinship of experience that countered the purported incommensurability of men’s and women’s war work.

If the Harrods Weekly Price List and Burberry advertisements suggest that the mackintosh offered a mediated, material form of denial during the war, newspapers provided readers with ample evidence that the coat did not protect vulnerable bodies. On the same page of the Times of July 16, 1915, that carried the “ALL-PROTECTIVE” Burberry ad, readers saw several smaller classified notices for secondhand-clothing dealers. During the war, such dealers traded and advertised used uniforms, including, no doubt, trench-mackintoshes made by Burberry and Aquascutum. Used uniforms could have different provenances, but some of them undoubtedly came from bereaved families, who often received a loved one’s kit after he died at the front. Vera Brittain’s Testament of Youth describes reviewing her fiancé’s belongings after they were returned after his death.71 Many families kept their dead soldiers’ garments as mementos, but given wartime shortages and economic necessity, garb in good condition was also sold to secondhand-clothing dealers or distributed among family friends. In other words, Britain’s robust market for used clothing, as discussed in chapter 4, recommodified what may otherwise have remained family heirlooms. Brittain “never knew” what had happened to her fiancé’s clothes,72 but the classifieds suggested one possible destination for them.

Classified advertisements that ran throughout the war make the link between used coats and dead men even more direct. With the exception of the Times, these notices typically ran on the front page of daily newspapers, not toward the back, where they are located today. As a result, anyone picking up the paper would see these small announcements first. In many editions, advertisements for secondhand stores that dealt in used uniforms and trench coats were located, without evident irony, right next to the “Killed in Action” columns or appeals by charities that served wounded soldiers. The Daily Telegraph, for example, of January 5, 1917, published a call for used clothes by Salmon and Co. in the column next to “Killed in Action.”73 This unhappy juxtaposition was not unusual: on July 5, 1917, the Telegraph similarly put “Killed in Action” announcements right next to offers to purchase “Officers Uniform and All Effects” (figure 2.6). One might almost suspect the Telegraph of pacifism, but the newspaper was firmly conservative in outlook. Classifieds placed by Salmon and Co. and other secondhand-clothing dealers continued to promote their trade in officers’ garments for years after the war ended, reminding readers of the business long after the armistice.74

Advertisements for trench-mackintoshes thus nestled cheek by jowl with reminders that such coats could not, in fact, defend against “all” the threats of the trenches. The garments could keep rain, wind, and mud at bay, but they could not shield against bullets, bombs, poison gas, and other weapons. In the years after the war, battlefield tourism and memorials helped to forge an association between violence and mackintoshes sold for use at the front; the garments themselves remained to testify to human bodies that lived and died wearing them. As Jane Marcus writes, “Blood-soaked…coats are exhibited in the museum of World War I at Le Linge in Alsace.”75 The afterlife of such garments not only reminds museum visitors of the bodies that fought, were wounded, and sometimes died in their military macs, but also demonstrates that the object world often enjoys a permanence denied the human subjects who design, manufacture, purchase, and wear clothes. The mackintosh—in parallel with the black evening gowns that signaled mourning in the period—becomes a kind of memento mori in museums and in postwar texts, which frame the thing as more stable, more viable, than the human.76 Although blood-stained coats lose their value as commodities—in contrast to secondhand garments, they are removed from circulation—they take on a new role as muséal objects and continue to have a use value denied their wearers. The death of Blimey, whose final words express horror at soaking her new Burberry with blood, serves as a fictional mirror for the men and women who died in macs that might memorialize but did not protect them.

Postwar Reflections and Transformations

The world of James Joyce’s Ulysses seems a long way from Burberry advertisements, the Harrods Weekly Price List, and the battlefields of France. The novel, set as it is in Dublin in 1904, appears culturally and historically removed from World War I; Joyce’s landmark aesthetic experiment seems equally removed from the war fiction of the 1920s and 1930s. As any student of modernism knows, however, Ulysses was written during the war and published less than four years after it ended. Joyce’s man in the mackintosh (M’Intosh), who remains mistakenly identified throughout the book, has seemed to take no part in the text’s historical moment, but his sartorial choice resonates with the slide from person to thing effected by the coat during the war.

Because the character is so oddly attired—he sports a raincoat on a sunny day during a drought—and because he is never identified by his proper name, M’Intosh has attracted the notice of many scholars. The arguments about this character are as heterogeneous as Ulysses itself, but they tend to fall toward two poles: those that claim that M’Intosh can be positively and correctly identified, and those that use M’Intosh as a lens into modes of understanding Ulysses.77 Like the second cohort of critics, I do not think that Joyce’s riddle can be solved. We can, however, explain why Joyce selected this garment for his character. Because the name of the garment can revert to a proper name—in Michael Sidnell’s words, it is “an eponymous noun which is (unintentionally) made to revert to a proper one”78—the selection of the coat may appear self-explanatory. It represents a reversal of the process described by Cunnington at the outset of this chapter: instead of a person becoming a thing, a thing becomes a person. Or, rather, the name permits a person/thing assemblage, a character who is both a human (he has a history; he moves around the city of Dublin) and an object (it does not speak). Like the coats addressed earlier in this chapter, the mackintosh in Ulysses elegantly communicates the character’s presumptive poverty: he eats dry bread, and his inexpensive garb manifests his limited means.79 Most important, however, is a hitherto ignored reason that Joyce may have selected the mac for his silent, penurious mystery: the author uses the coat to suggest that the abstraction of human particularity enables men (and women) to be violently treated. If the savagery visited on Joyce’s character is symbolic rather than literal, it is nonetheless striking and (within the world of Ulysses) permanent.

In “Circe,” the dangers this garment poses to its wearer become most apparent. Leopold Bloom’s wild fantasies of power and punishment include a group of sightseers who die after stating, “Morituri te salutant.” M’Intosh then appears through a trapdoor—a feature often used in medieval and Renaissance plays as a sign for a grave or hell—and accuses Bloom of being “the notorious fireraiser.” When Bloom responds, “Shoot him! Dog of a christian! So much for M’Intosh!” he/it disappears with martial signs and rhetoric: “A cannonshot. The man in the macintosh disappears. Bloom with his sceptre strikes down poppies.”80 While the cannon shot does not apparently hit M’Intosh—he “disappears” but does not cry out or bleed—the character’s appearance is juxtaposed with those who die saluting their leaders. In the aftermath of World War I, Joyce’s representation of “cannonshot” and “poppies” (which were, of course, associated with the war dead because of the flower’s prevalence in France) fuses the hybrid person/thing M’Intosh with World War I. Although Bloom thinks about the man in the mac later in Ulysses, M’Intosh disappears in this scene, which surely reminded readers in 1922 of the recent war and its attendant losses.81

As Robert Spoo has argued in his analysis of “Nestor,” “Joyce’s text, though ostensibly out of battle, is a neutral zone crossed and recrossed by rumors and phantoms” of the war.82 The man in the mackintosh is one such phantom, his garment and “name” silent reminders of the militarism and death visited on millions of combatants. Equally important, M’Intosh speaks to the bizarre fusion of garment and wearer that the coat enacted; to wear the mackintosh, Ulysses suggests, is to give up individuation and human agency, however problematic and limited the latter may be. It is instructive to contrast M’Intosh with Leopold Bloom, who owns (but does not wear) a secondhand waterproof,83 and with the epic’s cast of characters who do not seem to possess a mac. By 1922, the garment must have seemed too threatening to wear, and Joyce’s perambulating coat figured the way that individuals could disappear under the things they put on.

In the postwar period, when Joyce and the other authors I have mentioned wrote and published their novels, the mackintosh was making something of a comeback in serials that focused on fashion. The garment was still marketed to working-class customers as utilitarian; advertisements for this kind of mac generally emphasize its cheapness and value, as in promotions for John Blanford’s inexpensive models in navy and fawn.84 Although Mattamac, another firm that advertised mackintoshes, claimed that its coats were “identical in appearance with the usual five-guinea Weatherproof,”85 the sales pitch for this class of coats focused less on quality than on low price.

If the working class had to make do with cheap mackintoshes, fashion columns demonstrate that those with money could look quite smart in their macs. These new coats, however, had to be carefully distinguished from the old mackintoshes. A striking number of columns acknowledge readers’ preconceptions of the mac. Eve opened a discussion of “the modern conception of the old-time mackintosh” by observing, “Let us hope that history will not repeat itself, for it would be nothing short of a catastrophe to have to return to the drab, ill-fitting, evil-smelling garb of yore.”86 The rhetoric of history and catastrophe locates the mackintosh temporally, marking modern macs as distinct from previous iterations of the garment. And yet, this differentiating gesture was repeated on other dates and in other publications, indicating that the “old-time mackintosh” remained a vivid memory for many consumers. In 1929, the Sunday Graphic’s “Vogues and Vanities” column, which focused on upper-class society news as well as fashion, described the garment’s transformation after first acknowledging its history:

[T]hose of us who can remember the days when a waterproof was the last word in dowdiness were forced to “sit up and take notice” last week. On Wednesday it rained relentlessly at intervals on the Goodwood racing crowd. But…society merely slipped on its newest macintosh of rubberized velvet or silk in a gay plaid design, or a satin coat made rainproof by some secret process.87

In this column, the mackintosh is redeemed from being “the last word in dowdiness” through new fabrics, colors, and technologies. By distinguishing the coat from earlier incarnations, the mackintosh of the 1920s was cast as a fashionable, distinctive object.

In the 1920s and 1930s, then, the women’s mackintosh was—with some labor—transformed at the level of consumer culture. At the same time, styles based on military coats continued to be popular for men and women. Even as the ready-to-wear and fashion industries framed some macs as stylish means of self-expression, there were reminders of the coat’s alignment with World War I. In advertisements for mackintoshes modeled on military styles, allusions to the conflict could be indirect. The February 3, 1932, issue of British Vogue, for example, published a promotion for the “ ‘Mosco’ Mackintosh,” which was “cut on the lines of a cavalry overcoat.”88 The reference to the cavalry in this advertisement signified perhaps no more than the style of the coat. In ads for Aquascutum weatherproofs, however, the war itself undergirded the brand; throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the firm traded on its garments’ wartime “experience.” An advertisement in the Early August 1923 issue of Vogue proclaimed that “in the Field of Sport women come to regard the Aquascutum Field Coat in the manners officers on Active service esteemed the Aquascutum Trench-coat—as a trustworthy bodyguard in worst of weather.”89 The personification echoes the description of trench coats as “best friends” during the conflict, positing an intimacy with material tested on the battlefield and subsequently available to all. The parallel between sports—specifically hunting, which would require a field coat—and war reminded readers of what men had worn at the front and advocated analogous garments for women’s civilian use. An ad from the 1930s headed “The Famous ‘Aquascutum’ Storm Coats” similarly promoted military styles to men, particularly model G.9, which was “originally designed for the rigorous conditions created by trench warfare” (figure 2.7). More than a decade after the war, such language continued to align the mac with the front; the camion positioned in the background of the advertisement serves as a visual reminder that the coat, a martial thing, is uniquely available for civilian use. The Aquascutum coat thus emerges as a kind of sartorial monument: if women and men purchased it because similar garments had proved themselves during the war, daily acts of individual consumption were undertaken through a constellation of collective identity, trench warfare, and military technology.

Because consumers could buy everything from stylish velvet mackintoshes to storm coats in the decades after the war, writers of the 1920s and 1930s had a range of associations to choose from when clothing their characters in mackintoshes. And yet, very few authors chose to depict the coat—and the characters who wear it—as stylish, sporty, comfortable, or modern. More often, mac-clad figures look like Mrs. Dalloway’s Doris Kilman, who tutors the Dalloways’ daughter, Elizabeth, and “year in year out” wears “a green mackintosh coat.”90 As Clarissa Dalloway speaks to Elizabeth, she senses Kilman’s presence:

[O]utside the door was Miss Kilman, as Clarissa knew; Miss Kilman in her mackintosh, listening to whatever they said.

Yes, Miss Kilman stood on the landing, and wore a mackintosh; but had her reasons. First, it was cheap; second, she was over forty; and did not, after all, dress to please. She was poor, moreover; degradingly poor.91

After Elizabeth and Kilman leave to go shopping, Clarissa muses about “love and religion,” which she envisions as “clumsy, hot, domineering, hypocritical, eavesdropping, jealous, infinitely cruel and unscrupulous, dressed in a mackintosh coat.”92 The range of qualities that Clarissa projects onto Kilman—and specifically into her coat—points to the tutor’s repulsive physicality, to Clarissa’s upper-class distaste for the unfashionably dressed, and to Kilman’s position as Clarissa’s rival for Elizabeth’s love and attention. If M’Intosh seems disembodied under his coat, Kilman’s abject body is all too present, and her mackintosh underlines rather than disguises that abjection.

There are obvious reasons for Kilman to wear the coat, even if the weather makes it seem unnecessary. Like the characters penned by West, Greene, and Orwell, Kilman’s poverty is materialized through the mackintosh.93 She “could not afford to buy pretty clothes,” so Kilman cannot make a striking, distinctive appearance. Instead of a silk or velvet mac, she is likely wearing something like the Blanford or Mattamac coat, in which case price is the garment’s sole virtue. Like West’s Margaret Grey before her, then, Kilman wears a coat that marks her as out of place in upper-class homes. When wealthy women criticize these characters’ coats—Clarissa describes Kilman’s appearance as inflicting “positive torture”94—such comments reveal as much about upper-class assumptions and values as they do about the women who wear the mackintosh.95 Horrified reactions to the garment neatly emphasize divisions that neither class can bridge; if the war purportedly unified the nation, reactions to the mackintosh signal deep rifts in postwar unity. Moreover, while Margaret and Jenny kiss “not as women, but as lovers do,”96 Kilman “genuinely loved” the “beautiful” Elizabeth Dalloway, wishing to “grasp her,” “clasp her,” and “make her hers absolutely and forever and then die.”97 The female body that is produced by the cheap mac can thus be regarded as queer; economic alterity necessitates the adoption of a garment that affords—or, rather, produces—a gender identity and sexuality at odds with the femininity and heterosexuality that Kilman finds out of her reach.

The qualities that Clarissa mentally attributes to the mackintosh indicate that it figures more than the garment’s persistent class connotations. The coat makes Kilman appear clumsy and awkward in its expression of practicality. While a child might be expected to wear a mackintosh, an adult—particularly a woman—should have other values, whether they are “dress[ing] to please” or personal expression.98 Although her pragmatic and authentic appearance no doubt contributes to the tutor’s appeal to Elizabeth, Kilman herself “minded looking as she did,”99 and her mackintosh is not so much an attempt to transcend fashion (or a bold assertion of a lesbian identity) as an admission of sartorial defeat.

The power of the negative qualities that Clarissa imagines “in a mackintosh coat” signals, furthermore, that the garment embodies the “cruel and unscrupulous” war that Virginia Woolf and the other writers discussed in this chapter, regarded as barbaric and wasteful. It is a reminder of the women and men, including Kilman’s brother,100 who died in their mackintoshes. As the sole character who wears such a coat—even the shell-shocked Septimus Warren Smith wears a “shabby overcoat” instead of a mac101—Kilman becomes a perambulating reminder of the war that most people wanted to forget.

No other garment could so succinctly mobilize the range of qualities that make Doris Kilman repulsive to Clarissa Dalloway. Kilman’s childlike, unattractive appearance; anger and suppressed violence; and class status are all materialized in the mackintosh, which wears Kilman as much as she wears it. When Kilman stumbles into Westminster Abbey, which contains the “tomb of the Unknown Warrior,”102 Mrs. Dalloway points toward the many traumatizing objects that continue to haunt postwar London. Kilman’s coat suggests that the work of mourning continues, and is carried out, across time and space with the help of this one garment.103

Long-Lasting Legacies

Although the mackintosh would come to be associated with other qualities over time, it remained characterized, throughout the mid-twentieth century, by many of the traits I have discussed. What is, perhaps, most surprising about this persistence is that a range of texts aimed at quite different audiences deploy the mackintosh similarly. As I argued in chapter 1, there is continuity in representations of the evening gown across cultural strata, and yet feminist writers emphasized the potential pleasure that the garment offered in a manner that their contemporaries did not. The extent of agreement found in representations of the mackintosh is, therefore, striking, and it suggests a twofold rationale for British writers’ figurations of the garment. World War I, as I have argued, helped to align the coat with battlefield experience and with the war more broadly; in the postwar period, representations of the mac point to a shared reaction against a thing that configured individuals as masses—a sartorial form reminiscent of a military effort that most Britons wanted to put behind them. Whether one regarded the war as a tragic waste or as a necessary endeavor, few were eager to return to the type of collective struggle in which the mac had emerged as a quasi-uniform.

Equally important, the early literary examples of mackintoshes were profoundly influential. Novels like The Return of the Soldier and Ulysses helped to configure the mac into a garment that uniquely complicated the relationship between person and thing. Such works are particularly good examples of Rita Felski’s argument that “the significance of a text is not exhausted by what it reveals or conceals about the social conditions that surround it. Rather, it is also a matter of what it makes possible in the viewer or reader—what kind of emotions it elicits, what perceptual changes it triggers, what affective bonds it calls into being.”104 In highlighting the limited agency that characters in the coat can exercise, as well as their loss of identity, such representations provided later authors with a topos of the coat as diminishing singularity. In her popular novel Rebecca, for example, Daphne du Maurier deploys this model even as she extends the coat’s de-individuation into the private home. The young second wife of Maxim de Winter suspects that the spirit of Maxim’s first wife, the shadowy, glamorous Rebecca, “was in the house still…; she was in that room in the west wing, she was in the library, in the morning-room, in the gallery above the hall. Even in the little flower-room, where her mackintosh still hung.”105 Rebecca’s coat testifies to its former wearer’s life and death, and the narrator observes that the mackintosh also opens a portal between the two women: “Perhaps I haunted her as she haunted me…. The mackintosh I wore, the handkerchief I used. They were hers. Perhaps she knew and had seen me take them.”106 The coat and handkerchief emerge as foci for a silent, mutual regard. Equally important, the mac suggests that it and other objects enable a succession of women whose personalities are poles apart. In a novel that focuses on the differences between the narrator and Rebecca, the mac serves to underscore parallels between the two characters. Although the wife of Maxim de Winter could easily afford to purchase a new mackintosh, du Maurier chooses the (used) item to communicate the novel’s sense that humans are constituted by objects that render them not so much singular as sequential.

Graham Greene, in The Third Man, also represents the coat in a manner that underscores his dialogue with the mackintosh topos. The British military police officer Major Calloway appreciates the anonymity of his costume, which allows him to attend a funeral as “just a man in a mackintosh.”107 Like Joyce’s M’Intosh, who receives his moniker in a report on Paddy Dignam’s funeral, Greene’s character wears the coat to witness a burial, but he strategically adopts the mac to blend into the group of mourners. Greene (and Calloway, who himself seems to have read Ulysses) inherits and deploys the tradition that the coat conferred anonymity and was associated with funerals, mystery, and violence.108 Published after World War II, Greene’s novel proposes that particular individuals might embrace the very qualities that seem troubling in Ulysses; Calloway is nothing more than a “man in a mackintosh” to facilitate an investigation, and while he does not become the thing, as M’Intosh does, it is perhaps because he understands the implications of his dress.

In these examples and others, the mackintosh rises above the inertia ascribed to the object world to suggest that, at a time of ongoing class differences punctuated by total war, characters find themselves at the mercy of their clothes. This quintessentially British garment emerges across a range of texts—including high modernism, “hard-boiled” crime fiction, middlebrow best sellers, and the condition-of-England novel—as a place to meditate on the collectivizing powers of particular garments. Representations of the mac highlight, and often intimate concern about, a person’s inability to halt his or her own objectification: James Joyce’s man in the mac becomes M’Intosh; Helen Zenna Smith’s female noncombatant wearing a Burberry falls victim to the bombs dropped on male soldiers; Elizabeth Bowen’s Irish rebels seem less men than animated coats. While the fashion press and advice columns of the period insisted that British citizens could choose from a range of fashionable macs—that men and women could look distinctive, stylish, and modern—fiction repeatedly took up the coat to reflect a lack of choice and even to suggest that the premise of human agency (on which the notion of choice rests) is mistaken.

As Alison Clarke and Daniel Miller have argued in their work on fashion and anxiety, dress transcends “the idiosyncrasies of individual agency, instead operating as manifestations of socialization and power relations.”109 Writers represented the mackintosh to manifest such relations, to articulate a time and place in which bodies were standardized and de-individuated. The coats were worn by some people who could transcend their social roles: when Punch ran a poem called “Happiness” in its June 18, 1924, issue, it depicted a little boy named John who had a “Great Big / Waterproof / Macintosh.”110 John would clearly grow up, and macs would stop being the very stuff of pleasure and fun. Most characters whom authors dress in the mac are, however, less able to move out of the places that fix them. Servants, the poor, soldiers, and officers had little opportunity to assert an individual agency. Such characters—in contrast to Charles Macintosh, who secured a type of fame and futurity through the coat that bears his name—become less persons than things in plots that emphasize inequality, straightened circumstances, and extreme physical vulnerability.