The cheetah is only marginally faster than its preferred prey – some gazelle species reach 90 km/h – so a successful hunt usually requires a typically feline stalk to narrow the distance. In most hunts, cheetahs carefully approach their prey to within 50–70 metres before commencing the chase.

The majority of the leopard’s kills are made when the cat is less than five metres from its target. To bring itself so close, the leopard exercises boundless patience and a superb ability to exploit all available cover.

All cats are opportunists, meaning that they kill what they can, when they can. Evolution has engineered cats to seize any opportunity to kill, regardless of whether hunger is the motivation. It means that, on occasion, cats kill more than is required merely to satisfy their energetic needs. I once watched three lions that had been feeding on a freshly killed wildebeest lie in wait as a second wildebeest and later a zebra wandered heedless into their midst. Both were killed by the lions within metres of the original carcass and left virtually untouched. Similarly, many a farmer who has suffered the loss of a dozen penned goats to a caracal or leopard despises the killer for being ‘wasteful’. But to the cat, the drive to kill is overwhelming. A wild cat never knows when it will next eat, so being constantly primed to kill makes sound evolutionary sense. Any individual cat not so utterly compelled to kill might hesitate when it really mattered, and wind up starving to death.

For all that, though, the opportunity to kill more than they need rarely arises for cats in the wild; surplus killing is restricted largely to artificial circumstances such as when livestock is corralled or trapped against fences. Normally, a cat’s meals result from a determined and sometimes exhausting hunting effort driven by the immediate need to feed itself or its cubs. To do so, cats employ a surprising variety of strategies, but the mainstay for all species is a dogged search ending with a stalk.

Finding prey – the search – has the appearance of being a haphazard process in which a cat wanders through its home range until it encounters a target. In essence, this is what every hunting cat does, but despite appearances, it is far from random. Cats are intimately familiar with their surroundings. They clearly carry in their heads a sophisticated blueprint showing the locations of rest sites, places to lay an ambush, waterholes, paths and trails, open areas, observation points, and so on. Acquiring this knowledge presumably takes some time, partly the reason why newly independent, adolescent cats often do not survive (see Chapter 4). To an adult cat, though, experience has taught it where the chances of finding something to eat are high, and it is those places where hunting effort is focused. So, a female leopard setting out on a hunt heads towards the transition between woodlands and open areas, which she knows are favoured by impalas. To reach her destination she moves onto game paths, helping to increase her view ahead, knowing that her quarry also uses them. As she walks, she scans continuously, looking for the flicker of an antelope tail or ear in the distance, and listening for tell-tale vocalisations or rustling vegetation. From time to time along her route, she seeks out high points, climbing kopjes, termite mounds or trees to increase her field of view. She also detours to check possible rest sites for smaller quarry, assiduously investigating small bushes and thickets of grass where hares or young antelope might be hiding. And she stops at the entrance of warthog burrows, listening and even smelling to determine if there’s an occupant.

Systematically scouring her range like this, the leopard is assured of finding a meal sooner or later. Often, like all cats, she stumbles upon prey before she has the chance to stalk it. Although such spur-of-the-moment hunts generally make a minor contribution to the kill tallies of most cat species, they may have a surprisingly high success rate. Paul Funston showed that lions in the Kruger National Park bushveld were more likely to make a kill when they chased prey immediately upon detecting it, rather than by stalking. Further, such spontaneous hunts often require less effort. Once, while following a female cheetah walking slowly through metre-high grass, I saw her chance upon a resting reedbuck which the cheetah caught where it lay. If not for the single, strangled bleat of the doomed reedbuck, I would have supposed the cheetah had flopped down to rest.

Melting into cover and freezing to avoid discovery when the prey looks up, a stalking cat inexorably closes the gap until it can unleash the final, explosive attack.

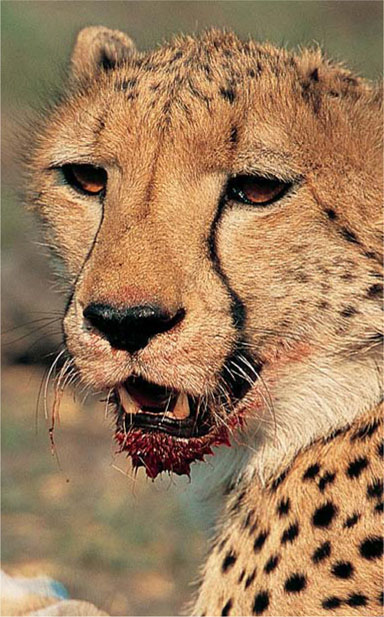

Although it’s atypical, cheetahs occasionally lie in wait to ambush prey. This impala kill was made by one of the cheetahs hiding in a reed bed at the edge of an open area until the impalas wandered into striking distance.

More often, though, a hunting cat detects an opportunity ahead of time and initiates its exquisite approach. Cats are unmatched among predators in their ability to cover ground undetected, bringing them within metres of highly strung quarry whose survival depends on being constantly alert. Melting into cover and freezing to avoid discovery when the prey looks up, a stalking cat inexorably closes the gap until it can unleash the final, explosive attack. In the open, semi-arid terrain of north-eastern Namibia, researcher Phillip Stander measured 94 stalks by leopards, which covered distances ranging up to 218 metres. On average, the final rush was launched when the leopard was less than five metres from the prey, and was never greater than 15 metres. The distance is very similar for lions, at least for prey species with explosively fast acceleration. Lions hunting Thomson’s gazelles in the Ngorongoro Crater usually succeed when they launch their attack from 7.6 metres or less; they consistently fail when the distance exceeds 15 metres. For larger, heavier targets with slower acceleration, the minimum distance increases. In the Serengeti, George Schaller noted that rushes from an average distance of 30 metres often produced a kill when hunting large prey such as wildebeest.

The cheetah exploits the advantage of speed to its evolutionary limit but, unlike the lion, its acceleration is on a par with the swiftest of prey, reaching 75 kilometres per hour in the first two seconds of a chase. The cheetah is the only felid to run down its quarry with a high-speed pursuit, covering up to 500 metres, and it launches its final rush from a much greater distance than any other cat. When hunting adult gazelles in the Serengeti, the distance is around 70 metres but it may be as distant as 300 metres. Importantly, though, and contrary to popular belief, the cheetah usually precedes its chase with a typically feline stalk. Although less prolonged than the pains-taking belly-crawling advance of other cats, the cheetah’s approach is just as strategic. Exploiting all available cover that sometimes includes tourist vehicles, and dropping flat to the ground or freezing whenever the prey looks up, cheetahs narrow the distance to the prey in fairly typical feline form. Indeed, faced with almost completely bare ground, cheetahs in the Sahara flatten themselves on the sand and freeze, slinking forwards only when their gazelle quarry is grazing. The final distance to the prey resulting from such meticulous stalks is typically about 30 metres.

Variations of the search-and-stalk theme constitute the chief hunting technique for all cats. Despite its tiny stature, the black-footed cat is a predatory powerhouse with at least three distinct tactics. Like all felids, it methodically quarters its range in the search for prey. True of all smaller cats that have been properly observed, the black-footed cat takes particular care with the search-and-stalk method, snaking carefully between tufts of grass and scrub, its head moving from side to side as it watches and listens intently. Servals are similarly meticulous but they search from above, raised on stilt-like legs which, relative to body size, are the longest of all cats. Elevated above the long grasses, servals move slowly and tread softly, pausing for up to 15 minutes at a time to listen with their oversized ears for concealed rodents, birds and frogs. Also long-legged and favouring similarly well-watered, high grass habitats, jungle cats probably hunt in careful, serval-like fashion but there are few observations to confirm this.

The black-footed cat’s second strategy is more reminiscent of foraging jackals or weasels. Known as ‘fast-hunting’, the cat moves in a swift zig-zagging jog, trotting at a steady 1–2 kilometres per hour, hoping to surprise and flush prey, particularly birds. Equipped with characteristically feline reflexes, black-footed cats execute gymnastic leaps up to 1.4 metres high – almost three times their own length – to snag birds as they burst from hiding. Caracals and African wildcats also fast-hunt, sometimes with similarly acrobatic results, though only a handful of observations exist, all from arid, scrubby habitats similar to the black-footed cat’s; perhaps open country scattered with many potential hiding places for small prey favours the method (or possibly it simply increases the opportunities for biologists to observe it).

In a final alternative approach, known as the stationary or sit-and-wait strategy, cats exercise consummate feline patience waiting at strategic sites for prey to appear. Sitting in wait like this, black-footed cats lie perfectly immobile for up to two hours at the entrance of rodent burrows until the occupant emerges. The leopard’s version of the technique may be the species’ most common strategy in equatorial Africa, where dense habitat hinders visibility and limits the use of long stalks and chases. Leopards in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s (DRC) Ituri Forest wait at fruiting trees, which attract duikers and red river hogs; based on signs at freshly killed carcasses, they ambush their prey from a few metres away. In the only comprehensive observations made of a hunting rainforest leopard, biologist David Jenny watched a female hide herself on 91 occasions in dense vegetation near troops of forest monkeys, and wait for them. Monkeys came to within 50 metres of the leopard in 60 per cent of her hiding bouts, though the technique yielded only one successful attack (a sooty mangabey). Importantly, though, most of Jenny’s observations took place during the day when leopards typically have lowered hunting success; furthermore, his presence may have affected the outcome.

The serval is able to execute leaps over four metres long and up to three metres high. If the initial attack fails, servals often pursue fleeing rodents by a series of bounding zig-zagging pounces that attempt to pin down the quarry.

Servals also adopt the sit-and-wait strategy, relying chiefly on their exceptional hearing to detect targets. In the Ngorongoro Crater, they listen patiently for rodents in the clumped tussocks of kasangani grass, and elsewhere servals have been seen finding common mole rats underground by sound; on locating their quarry, they scratch away the entrance mounds to reveal the shallow dead-end burrows with the occupant inside. For deep-burrowing species of mole rats, servals in eastern DRC were seen to dig lightly at the plugged entrances to entice the fastidious owner to the surface for repairs. Revealingly, the serval’s attempts at digging are never very strenuous and no cat species is especially efficient at excavating subterranean prey (see Chapter 1). On occasion, lions and leopards spend hours extracting warthogs from shallow burrows, but perhaps the most fossorial (adapted for burrowing) member of the family in Africa is the sand cat. Often considered the northern analogue of the black-footed cat, the sand cat’s diet is also dominated by small desert rodents, and it probably has a similarly diverse range of strategies to catch them. So few people have seen sand cats hunting in the wild that the extent of their hunting repertoire is unknown, but among local people they are celebrated for a skill not yet seen in black-footed cats – speedily burrowing into soft sand in pursuit of desert rodents. Indeed, sand cats are so proficient at the technique that the Touareg people of Niger refer to the sand cat as ‘the cat that digs holes’.

Co-operative hunting in cats

Except for mothers accompanied by large cubs, lions and cheetahs are the only cats that hunt in social groups. For both species, group hunting improves success; Kruger National Park lion singletons and pairs have a 21 per cent success rate when hunting, compared to 35–39 per cent enjoyed by trios and quartets. Looking at it slightly differently, Serengeti male cheetahs belonging to a trio eat slightly more each day than do single cheetahs. But do such benefits result simply because a target is less likely to elude three cheetahs than one, or because hunting cats actually co-ordinate their efforts? Evidence for co-operation by cheetahs is slim: one cheetah sometimes distracts adult herbivores attempting to defend their youngsters while his partner makes the kill, and adolescent cheetahs hunting with siblings appear to be braver when tackling larger prey (resulting in more kills) than when they hunt alone, but true co-ordination is exceptional.

However, the evidence for co-operation among lions is more persuasive. In Etosha National Park, lionesses apparently adopt different roles to enhance their success. ‘Wings’ circle the prey on long stalks and usually initiate the attack, while ‘centres’ mostly stay put and wait for the wings to drive prey towards them. Each individual lioness adopts the same role – wing or centre, but rarely both – in all hunts, and the most successful hunts are those where each lioness is in her preferred position. The Etosha study is the only one to date demonstrating such precision, perhaps a result of the very open habitat which makes opportunistic ambushes unlikely.

Without assistance, this lone lioness in Etosha National Park has no chance of pulling down an adult giraffe, but the collective might of the pride enables a group of lions to tackle very large prey successfully.

Weighing up to 870 kilograms and formidably equipped to defend itself, the African buffalo is a daunting adversary and many hunts are foiled by the collective defence mounted by the herd. The lion is the only predator capable of preying regularly upon adults, but even so, buffaloes are responsible for more lion casualties than any other prey species.

Prey: the eating habits of cats

All cats have tiny backwards-facing barbs called papillae that cover the surface of the tongue and are used for rasping flesh off bones and for grooming. Unexpectedly, each lineage of cats (see the phylogeny chart on page 44) has its own unique pattern of papillae on the tongue.

Cats make their living by killing. As discussed in Chapter 1, the members of the cat family are the most predatory of all mammalian carnivores, requiring a diet derived almost entirely from other animals. Virtually all land vertebrates (and many invertebrates) in Africa are fair game to the cat family and, even if a particular species has not appeared on a published list, chances are that a cat has killed it. The way of the cat is to kill anything it can physically overpower, and indeed the family is notable among solitary carnivores for consistently taking species as large as or larger than themselves. Moreover, as seen in the previous section, cats employ a wide variety of techniques which not only enhance their chances of finding prey but also increase the selection of prey types available to them.

For all that, though, cats are quite discerning about what they hunt. Although a leopard resting at a Kalahari waterhole will expertly snatch sandgrouse as they alight to drink, leopards are too large to live off sandgrouse alone. Cats need to invest their effort in hunting prey that provides enough of a pay-off to balance the energetic costs of finding and killing it. The result is a pattern in which, while cats opportunistically kill anything they can, a far narrower selection of prey comprises the bulk of their diet.

The big cats: big game hunters

Africa’s three large cats depend upon large meals. Lions, leopards and cheetahs are alike in requiring medium- to large-bodied mammals as their mainstay, even if their tastes sometimes appear far more varied. A supreme opportunist that kills virtually everything it encounters, the lion is recorded eating a suite of prey that ranges from dung beetles to adolescent elephants. It eats a wide selection of birds, including ostriches, bustards, guinea fowl, francolins, plovers and birds’ eggs, while reptiles on the menu include terrapins, tortoises, African rock pythons, Nile monitors and crocodiles. Lions scavenge from whale carcasses washed ashore on Namibia’s Skeleton Coast, consume tsamma melons in the Kalahari and are not averse to eating each other. Yet, catholic tastes notwithstanding, the lion must deal with two key biological constraints at mealtimes: a very large body size and large family groups. An individual lion is too large to survive on small prey or those that are rarely encountered, which includes all of those listed above. Furthermore, as the most social of all felids, they require a prey base sufficient to feed many mouths at once.

Two lionesses and their cubs compete for warthog remains during the dry season in Savute, Botswana. During extreme shortages of prey, young cubs sometimes starve or are mortally injured while competing for their share.

The solution for lions lies in hoofed prey. Wherever they occur, lions concentrate on the most abundant, large ungulates available, with wildebeest topping the list for many lion populations. In the southern Kalahari, wildebeest (at 37 per cent), gemsbok and springbok make up slightly more than 82 per cent of lion kills. Of more than 12 300 lion kills recorded by rangers in the Kruger National Park between 1933 and 1966, wildebeest comprised 2 906 of them, almost a quarter. Six species – wildebeest, impala, zebra, kudu, waterbuck and buffalo – accounted for more than 90 per cent of Kruger National Park lion kills. A similar pattern occurs in the Serengeti, where seven ungulates ranging in size from Thomson’s gazelles to buffaloes make up 90 per cent of kills. Wildebeest again head the count, though only for the open plains during the wet season when they are abundant. During the dry season, when wildebeest are scarce on the plains, lions switch to warthogs and Thomson’s gazelles. In contrast, lions inhabiting the Serengeti woodlands and their edge habitats are able to exploit resident species that are abundant year-round. To woodland and edge lions, warthogs and buffalo are the most important prey species throughout the year. It is not yet clear where the lower threshold of lion prey size lies but prides in Namibia’s Etosha National Park might subsist at the limit. Watching 920 hunts, Phillip Stander found that 73 per cent of lion kills were of springboks. At under 50 kilograms, this is the smallest preferred prey size recorded for any lion population.

Weeding out the vulnerable

A common refrain holds that cats are more likely to prey upon vulnerable individuals and thus help weed out the infirm and weak from a prey population. The problem with the idea is that the felid method of hunting does not particularly lend itself to identifying vulnerable animals. Long distance coursing, as used by African wild dogs or spotted hyaenas, is far more efficient for singling out an individual in trouble than the cat’s close-in stalk-and-rush strategy. The high-speed pursuit used by cheetahs might provide an opportunity to isolate unhealthy prey, and cheetahs occasionally appear to ‘test’ a herd by running openly into its midst. Serengeti cheetahs are more likely to run down the least vigilant gazelles which, in some cases at least, are males that are unwary because they are exhausted or injured by the rut. Equally, though, there are many cases of apparently healthy animals being targeted simply for not remaining alert. It remains the case that, in careful studies of felid-prey interactions, the evidence for cats selecting the infirm is weak.

A solitary hunter and about a third the size of a lion, the leopard is freed of some of the larger cat’s limitations when it comes to feeding itself. Leopards have the most diverse diet of all African cats with at least 100 species recorded from sub-Saharan Africa alone. The leopard’s smaller body size allows it to switch to prey that could not possibly sustain a lion. In north-eastern Namibia where prey is thin on the ground, most kills weigh less than 20 kilograms, with common duikers and steenboks dominating. Rock hyraxes are the most common prey item in many areas where the antelope biomass is low, among them Mount Kenya’s alpine zone, Zimbabwe’s Matopos Hills and the Cederberg range in the south-western Cape. Leopards eat frogs, locusts, scorpions, termites, crabs, fish, birds, reptiles and their eggs, indeed, virtually anything living. The known inventory does not include prey of the critically endangered leopards of North Africa which have never been studied but which exist with (and presumably eat) a number of species that do not occur south of the Sahara, among them red deer, barbary sheep, Cuvier’s gazelles and red foxes. A thorough study of these leopards would doubtless swell the list even further.

Importantly, though, just as with the lion, leopards subsist primarily on antelopes. In savanna ecosystems where the leopard has been well studied, the same pattern of concentrating on the most abundant ungulates manifests itself, if scaled slightly downwards. This translates to the leopard specialising in antelopes in the 20–80 kilogram range. In the southern part of the Kruger National Park, the most common antelope in this size class, the impala, makes up almost 88 per cent of their kills. In the Serengeti, preferred prey is the Thomson’s gazelle whereas in Zambia’s Kafue National Park, reedbuck, young waterbuck and puku are most often taken. In the moist savannas of West Africa, antelopes contribute between 53 and 67 per cent of the meat that leopards consume. Surprisingly, though, together with the kob and the western hartebeest, the most important prey species to these leopards is the greater cane rat. In one site, Côte d’Ivoire’s Marahoué National Park, Frauke Fischer and her colleagues calculated that the large rodent is the local leopard’s number one species.

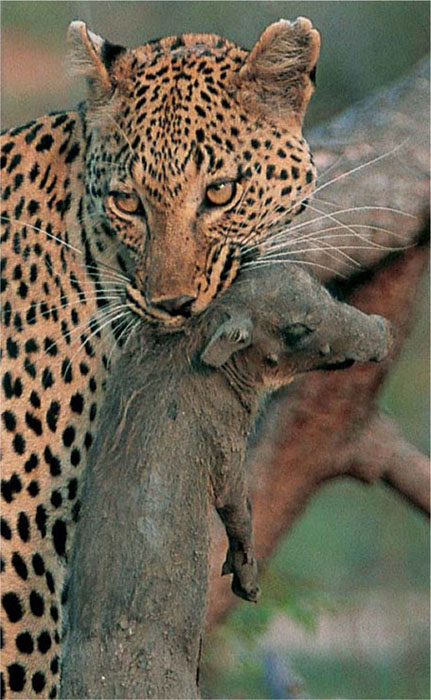

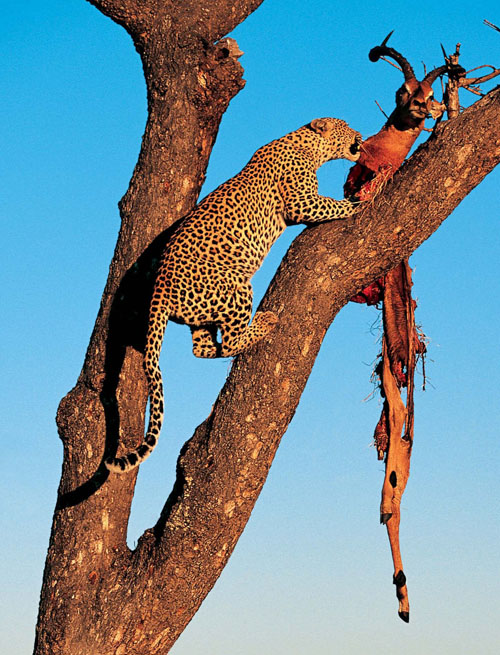

The leopard is the only felid that consistently caches its kills in trees (although it is occasionally also recorded in caracals), a strategy to avoid losing carcasses to lions, spotted hyaenas and other competitors. Where competitors are scarce, leopards rarely haul their kills up trees, and feed mainly on the ground.

Separated from the safety of the herd, this young buffalo calf is doomed. Large buffalo herds usually stand their ground when threatened by lions, and the key to a successful hunt is to panic the herd into stampeding so that an individual can be targeted.

Leopards inhabiting rainforest have fewer ungulates from which to choose, both in terms of diversity and density. Nonetheless, red river hogs and forest duikers are their most important prey species with water chevrotains, forest buffaloes, okapis and sitatungas occasionally killed. Primates are the next most important group to forest leopards, with 11 different species recorded from studies in Côte d’Ivoire, DRC and the Central African Republic. Various arboreal species of colobus and mangabey monkeys are most important, but even the great apes are not invulnerable. In the Taï Forest of Côte d’Ivoire, leopard predation is the main cause of chimpanzee deaths, and indeed leopards and lions are the only carnivores able to kill adult chimps (lions rarely kill chimps, mainly because they mostly occupy different habitats, but four confirmed cases are known from when a pride passed through Tanzania’s Mahale National Park in 1989). Researchers in the Taï Forest documented at least 17 cases where leopards killed and ate chimps during a 12-year study. Leopards have also been recorded killing lowland gorillas, and, recently, researcher Danielle D’Amour working in DRC’s Salonga National Park recorded bonobos as leopard prey for the first time.

Of the three big cats, the cheetah takes the narrowest range of prey. Of 325 cheetah kills I recorded in South Africa’s Phinda Game Reserve, 322 were ungulates ranging in size from steenboks and red duikers to young giraffes and sub-adult wildebeest (the three outstanding kills were one adult ostrich and two cases of cannibalism). Three species of antelope – nyala, impala and common reedbuck – comprised over 80 per cent of kills. The same specialised pattern repeats itself throughout Africa. Springboks make up almost nine out of ten cheetah kills in the Kalahari Desert, while two-thirds of all cheetah kills on Tanzania’s short grass plains are Thomson’s gazelles. In the great swathe of woodland savanna habitat stretching along Africa’s east coast, from South Africa to southern Kenya, cheetahs focus on impalas. Exceptional prey recorded for cheetahs includes bustards, guinea fowl, cane rats, mole rats, one record of a baboon and, very rarely, other carnivores including caracals, jackals, bat-eared foxes and Cape foxes. Taken collectively, this mixed bag of unusual kills never comprises more than five per cent of the cheetah’s diet.

Medium-sized cats: robust rabbit-traps

A caracal suffocates a rock hyrax. Daytime kills like this occur fairly often where caracals are protected, but elsewhere they hunt primarily at night.

Leaving the three larger felids, there is a conspicuous drop in the size class of cats. After the similarly-sized cheetah and leopard, we see a gap to the next largest cats spanning around 25 kilograms. The caracal, African golden cat and serval share similar body sizes and weights, but while the serval’s lanky proportions reflect a specialisation on rodents (see page 76), the caracal and golden cat are built to handle larger quarry. The robust caracal is renowned for its ability to kill outsized prey. Able to tackle antelopes up to three times their weight, the caracal’s menu includes mountain reedbucks, springboks, female impalas and young greater kudus. In the Kalahari, Gus Mills saw a caracal on a freshly killed adult ostrich which he estimated at 100 kilograms – at least five times the weight of the cat. Such large kills represent the upper threshold of the caracal’s predatory prowess, though, and more typically, they focus on smaller mammals. Caracals are surprisingly under-studied given their wide range and comparative abundance, and detailed information on their feeding ecology is available only from South Africa. There, rock hyraxes, hares, duikers, steenboks and small rodents make up the bulk of their kills. Birds are often regarded as a caracal favourite but, in fact, most studies show they represent a minor percentage of prey. On South Africa’s west coast, small birds reach a peak in caracal diet, perhaps because of the low densities of larger mammal prey. On average, birds constitute slightly more than 23 per cent of caracal diet in the West Coast National Park, and they comprise more than half their kills in months when migrant birds swell the numbers.

The little knowledge about the African golden cat’s diet comes almost exclusively from analysing their scats. A chance observation from Kenya’s Kimikia River near the Aberdare National Park of a golden cat killing a Syke’s monkey is one of the few eyewitness accounts available. It confirms that golden cats prey upon forest primates, although, in the only detailed studies from DRC’s Ituri forest and Dzangha-Sangha in the Central African Republic, primates occurred in only five per cent of scats. Golden cats feed proportionally more on small rodents, squirrels and forest duikers, and they thrive where the understorey is most dense, sheltering high densities of these species. They are also thought to benefit from occasional scavenging of larger prey. Local people in Ituri report that golden cats feed upon large duikers killed in snares and they probably also scavenge the remains of crowned eagle kills and fallen monkeys on the forest floor. Like most cats, an opportunistic balance of hunting and scavenging probably satisfies the golden cat’s daily needs, but until a determined researcher sets out to observe this elusive species more thoroughly, the finer details of its feeding ecology will remain a mystery.

A mother cheetah with large cubs feeds on a thomson’s gazelle, Masai Mara National Reserve, Kenya. Unlike lions, cheetahs show little aggression over carcasses and compete chiefly by bolting food as quickly as possible.

Small cats: rodent-killers

An adult serval kills around 4 000 small rodents each year, providing significant benefits to crop farmers. Under enlightened management, servals can thrive in agricultural areas but they are still widely persecuted in the mistaken belief that they are important predators of livestock.

Ranging in size from the 18 kilogram serval down to the 2.5-kilogram black-footed cat (both figures represent top weights), all five remaining species of African cats specialise in eating rodents. The diet of servals, which are common to Uganda’s Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Tanzania’s Ngorongoro Crater, Zimbabwean farmlands and the foothills of South Africa’s Drakensberg mountains, comprises at least 80 per cent small mammals such as Nile rats, vlei rats, various mice species and shrews. Small grassland birds like queleas, bishops and flufftails are collectively the next most common class of prey; cats slap them from mid-air or dispatch them by clapping their front paws together. They occasionally take swifter prey like hares and springhares, but servals are poorly built for pursuit and are easily outpaced by speedy quarry if the first pounce misses. Despite its long legs, the serval is designed for jumping rather than sprinting; its height is more the result of highly elongated foot bones – the metapodials – rather than lengthened limb bones. Indeed, it is more accurate to say the serval has long feet, rather than long legs and, unlike the cheetah’s compact metapodials and stretched limb bones (a combination for speed), the serval’s long legs deliver relatively sluggish speed but a prodigious ability to leap. The seasonal arrival in East Africa of huge flocks of migratory Abdim’s storks around October each year puts the serval’s aerial skills on spectacular show. Sighting a stork, the serval adopts a classically feline stalk to come up close. A short, explosive sprint ends in a skywards leap up to three metres high, snagging the heavy bird during its clumsy take-off. Lesser flamingos, korhaans, guinea fowl and francolins are also taken by these caracal-like acrobatics.

The jungle cat shares the serval’s adaptations for hunting in waterlogged, long-grass habitats. Although not as marked as in the serval, the jungle cat’s long legs raise it above sodden ground and its large ears help to pinpoint prey concealed in reeds and rank grass. As with the serval, small rodents make up the bulk of the jungle cat’s diet, and they also take water-fowl, small birds, hares and insects. Interestingly, although their physical specialisations for a wetland existence are less refined than the serval’s, jungle cats show a stronger affiliation for water itself and are capable swimmers. They have been recorded swimming across stretches of open water up to 1.5 kilometres wide and readily plunge beneath the water’s surface to catch fish and frogs. The stomach of one jungle cat examined near Alexandria in Egypt was full of fish and nothing else.

It is hardly surprising that the wild relative of the domestic cat is a mouse hunter. A range of figures from around southern Africa shows that the African wildcat’s diet is dominated by various wild mice and rat species. Wildcats also hunt Cape hares, rabbits and springhares, and are capable of killing very young antelope lambs, but they rarely kill anything exceeding four kilograms. Birds up to the size of korhaans, reptiles, amphibians and insects are also eaten, particularly during rodent shortages; wildcats readily switch prey when mice are thin on the ground and are able to survive for long stretches on less preferred quarry. During a drought in Botswana in which rodent numbers plummeted, wildcats subsisted solely on arthropods such as crickets and grasshoppers supplemented with small birds and, unexpectedly, the fruit of the jackalberry tree.

German biologist Alex Sliwa can be thanked for furnishing a spectacularly comprehensive insight into the eating habits of the black-footed cat. He witnessed more than 2 000 captures of prey made by this tiny felid in South Africa’s arid Kimberley region. The large-eared mouse tops its list, and small rodents, shrews and 21 different birds make up the bulk of black-footed cat kills. Sliwa observed successful kills up to the size of Cape hares and recorded scavenging on dead springboks, though hunting attempts made on living lambs always failed when the lambs stood up. Possibly unique to small cats is the black-footed cat’s habit of caching unfinished prey in shallow aardvark digs, concealing it with a covering of soil and grass. Surprisingly, the cat continues hunting even when many kills have been stockpiled. With winter night-time temperatures dropping below -8 °C and an elevated metabolic rate requiring constant fueling, continual hunting maintains the cat’s immediate energetic needs while also establishing a network of caches to ensure a meal later if prey becomes difficult to find.

Sand cats are hunters of small desert rodents, particularly gerbils and jerboas, but there are few detailed accounts from Africa. The best indication of their diet comes from the former USSR where the species was killed in large numbers for its long, silky winter coat. Soviet biologists recorded the unfortunate cats’ final meal and showed that, along with a rodent staple, common prey includes desert larks, sandgrouse, partridges, followed by hares, snakes, lizards, scorpions and insects. African sand cats probably have a very similar diet. The Toubou nomads of Niger regard the sand cat as a snake specialist and excellent records exist of their killing horned and sand vipers in the Sahara. Against such lethal adversaries, the cat employs a succession of rapid-fire blows to the snake’s head until it tires and lowers its defence. The coup-de-grâce comes to the exhausted snake by the agile cat pinning down its head with a paw and biting the skull or neck. In the only published account of such an encounter, the cat devoured an entire sand viper after killing it, consuming venom glands, fangs and all without harm.

A black-footed cat with its kill, a Cape turtle-dove. In the only comprehensive study of black-footed cats, conducted near Kimberley, South Africa, 21 species of birds made up a quarter of all kills by mass.

Statistics of the hunt: how well,how far, how often?

A lioness ‘tests’ a 1 000-strong buffalo herd in northern Botswana. Contrary to popular belief, there’s little evidence for lions selecting weak or vulnerable individuals but the strategy of running into herds probably improves chances of a kill by separating a target from the dangerous, defensive mass of the herd.

Discussions about the hunting success of carnivores and the effort it requires are plagued by problems of measurement and definition. A sand cat waiting at the entrance of a rodent burrow and lions chasing a herd of 1 000 buffalo for over a kilometre have the same goal in mind – to eat – but they represent vastly different expenditure of effort. Similarly, how does one measure the intent to hunt? Both the leopard that happens upon a newborn impala lamb, killing it where it lies, and a caracal that wrestles a young greater kudu to the ground, taking 45 minutes to kill it, have successfully hunted – but are they comparable events?

Perhaps the most meaningful answer is that cats are as proficient as they need to be. To most adult cats, starvation is a rare threat, which means that they are at least efficient enough to survive. For females raising cubs, the stakes are higher and, under conditions of extreme food shortages, cubs may be abandoned (see Chapter 4). However, excluding these relatively rare events, cats are clearly proficient at balancing effort with intake. How they do so varies surprisingly among species.

Among the most impressive figures, the black-footed cat boasts some extraordinary statistics. Of the many hundreds of kills seen by Alex Sliwa, about 60 per cent of them produced a kill, one of the highest success rates for any cat. Black-footed cats typically make between 10 and 14 kills a night, averaging a kill every 50 minutes and eating between 250 to 450 grams – 20 to 30 per cent of their body weight. They cover up to 16 kilometres during a single night’s foraging, though Sliwa is careful to point out that he measured the distance by following behind cats in his vehicle; the real distance covered by the endlessly weaving hunter could be twice as much.

Servals in Ngorongoro Crater average a success rate of 49 per cent. They are most efficient hunting insects (54 per cent), least so while hunting small birds (23 per cent), with their mainstay, rodents, coming in at the average (49 per cent). Well protected and free of human persecution, Ngorongoro servals show a prevalence for diurnal activity and have greater returns from daylight hunting. They average one kill per hour during the day, compared to a kill every two hours at night. Looking at it another way, Ngorongoro servals make three kills per kilometre walked during the day compared to an average of 1.9 kills per kilometre at night. Hunting servals cover around 4.5 kilometres every 24 hours, occasionally walking as far as 10 kilometres. Servals kill an astonishing number of small animals every year: Aadje Geertsema watched 12 Ngorongoro servals for four years and calculated that each killed 3 950 rodents, 130 birds and 260 snakes annually.

At first glance, the figures for large cats seem somewhat less impressive. However, it is important to bear in mind that large felids hunt large, sometimes dangerous species that provide a greater return. Leopards in north-east Namibia walk up to 33 kilometres in 24 hours and average a kill once every 2.7 hunts, a success rate of 38 per cent. Tracking Kalahari leopards, Koos Bothma showed lower rates: females with cubs were most successful (27.9 per cent) compared to females without cubs (14.5 per cent) and males (13.6 per cent). Annually, Kalahari leopards average 111 kills for males to 243 kills for females, the higher figure for females reflecting more, smaller kills. Leopards in the Kruger National Park make fewer kills of larger prey, equating to one adult impala per week.

As the only intensely social felid, lions might be expected to show elevated rates of success. Although group hunting does increase success (see text box ‘Co-operative hunting in cats’, page 63), their overall success rate is comparable to other large cats. An average across numerous studies gives an overall rate of around 26 per cent, ranging from 15 per cent to 38.5 per cent. Etosha lions have the lowest success rate, perhaps because they inhabit such open habitat. Surprisingly, males and females are often equally successful hunters. From 679 attempted hunts seen by Paul Funston and Gus Mills in southern Kruger National Park, females succeeded around 27 per cent of the time compared to 30 per cent for males (the difference is negligible when the appropriate statistical tests are applied). Hunting success was least for medium-sized prey such as wildebeest, kudus and zebras (20 per cent) and climbed to more than 50 per cent for buffaloes.

Tackling large, well-armed prey carries significant risks to cats, particularly when a prolonged struggle results, such as between this cheetah and impala. Although it does not occur often, species recorded killing cheetahs include gemsbok, blue wildebeest, warthog and domestic cattle.

With about a third of their chases ending in a kill, cheetahs have a success rate slightly higher than lions. On the open grasslands of the Serengeti where Thomson’s gazelles comprise the cheetah’s preferred prey, estimates of hunting success vary from 29 to 54 per cent (emphasising the problems in comparing measurements made by different researchers). When hunting very young gazelles, the figures show far less ambiguity: 100 per cent of hunts on newborn gazelles witnessed by Schaller resulted in a kill, while a comprehensive set of observations made by Tim Caro revealed a 92 per cent success rate for female cheetahs and 86 per cent for males. Although baby gazelles are extremely swift, they simply cannot match the cheetah’s extraordinary speed, reliably timed at 105 kilometres per hour. Hares are also easily killed, 87 and 93 per cent of the time when hunted by females and males respectively. Caro further showed that hunting ability improves with age and, as detailed later in this book, that survival is not easy for young cats.