A male lion guards two lionesses in oestrus. During mating, males escalate their rate of roaring to reinforce their claims of ownership and to ward off possible rivals.

A lioness rebuffs the advances of a young male, Etosha Game Reserve, Namibia. Aggression between prospective mates is common, particularly those unfamiliar to each other, but it almost never results in anything more than superficial injuries.

Like every living organism, the cat’s fundamental biological imperative is to reproduce. As discussed in the previous two chapters, cats address the daily challenge of surviving by securing a range and the resources it contains. But, ultimately, the rich repertoire of hunting and territorial behaviour that allows a cat to make it from one day to the next is also geared towards ensuring reproductive success over the course of its lifetime. That success, or ‘biological fitness’, is measured by the ability of an individual to leave surviving, viable progeny.

The first challenge faced by most cats is overcoming their solitary tendencies and finding a mate. To achieve this, they employ the very same catalogue of behaviours intended to keep them apart. When a female approaches oestrus, the territorial displays discussed in the previous chapter – scent-marking, calling, scraping and so on – serve to attract members of the opposite sex. The switch occurs at the molecular level. Chemical changes in the female’s urine associated with elevated levels of oestrogen transform the message from a warning to a welcome – to the right audience, of course; to other females, the message presumably remains a warning and, although this has not been tested, probably a particularly explicit one keeping female rivals away. To ensure that males receive the invitation, females approaching oestrus increase their rate of urine-marking and associated come-hither behaviours, in particular calling loudly: the lioness’ roar, the leopard’s rasp or the black-footed cat’s deep caterwaul. On detecting the messages, males in return increase their own rates of marking and calling, announcing their presence to the female while also warning off potential competitors seeking the same prize.

The system clearly works efficiently. For those species that have been observed in the wild, it seldom takes more than 24 hours for a receptive female to be joined by a male. Even so, mating rarely occurs right away. Female cats of many solitary species begin advertising their availability up to three days before they are willing to accept a male. This period is known as pro-oestrus, and it ensures that pairs have sufficient time to find each other before the female’s oestrus (when the female is ready to mate and during which time she ovulates) has passed. It also provides time to establish familiarity with each other. Between such well-armed lovers, meeting for the first time can be a dangerous process. Often the early stages of the consort period are marked by outbursts of nervous aggression from both sexes as they overcome their asocial and potentially lethal predispositions. These spats are almost never serious though, and typically subside after a day or two. In the case of pairs that already know each other from prior meetings, they may not occur at all.

The pro-oestrous period might also be a mechanism whereby females encourage competition among males. By advertising her availability in advance, a female increases the likelihood that multiple males will turn up to compete for her attentions. Indeed, oestrous females attended by two or three males have been recorded in a number of cat species, among them leopards, caracals and wildcats. The behaviour is also known among lions and cheetahs, though in these species, attending males are almost always coalition partners, not unfamiliar rivals. Among lion coalitions, competition between males is usually negligible. Typically, the first male on the scene enjoys access to an available lioness, and his coalition partners stand down with little or no aggression. Doubtless, the arrangement works in part because lionesses in a pride usually come into oestrus at the same time, providing many mating opportunities; but even when that does not occur, familiar males rarely fight over females. In the case of cheetahs, mating is rarely observed (there are just five published accounts from the wild), but competition among coalition males appears to be equally mild. Two Serengeti brothers observed competing for a female tried to push each other off her with their heads.

Among solitary cats, there are few observations of direct competition between rival males over oestrous females. In theory, the female in heat represents an extremely valuable resource worth fighting for, but battle is either a rare event or there are simply too few observations for us to know. Competing males among leopards and all the smaller felids probably resolve most issues of ownership by largely demonstrative displays of ritualised feline aggression: standing sideways with back arched and hackles raised, accompanied by a stiff-legged walk, bared teeth and flattened ears showing, in most species, white or light-coloured warning patches. Such encounters must occasionally escalate into full-blown fights, but this is probably further tempered by the ‘rule of possession’, as in lions. I once saw a female leopard mate with three different males over three days. The first two males on the scene were both in attendance from the start, and one simply waited for 36 hours at a distance until the first male left. Male number two subsequently gave way to the remaining male on the third day. I did not see the changeovers to determine whether they were peaceful, though clearly there was no serious fighting; none of the males was injured when I saw each of them after the encounter. The same relatively tolerant arrangement has been noted among radio-collared caracals in Israel, where males stayed nearby and awaited their turn, with changeovers taking place around every 48 hours. It is not known whether the same pattern occurs in African caracals.

Mating behaviour: promiscuous females and misled males

Like all male cats during mating, this male leopard grips the female with a gentle bite to the loose skin of the neck. Known as the ‘inhibited nape bite’, it is thought to pacify the female, just as kittens are immobilised when carried by the scruff of the neck.

The end of mating is often marked by aggression from both partners. For females, the male’s spine-covered penis is thought to be the chief reason, though for both partners it probably also stems from anxiety at being so close to such a potentially dangerous mate.

Courtship in cheetahs is always prefaced by prolonged and apparently severe harassment of the female (here, on the right) by the males. The behaviour is thought to encourage the female’s receptivity but the theory remains untested.

As many a safari guide has explained to fascinated tourists, mating itself is both a brief and, for most cats, frequent event. Feline copulation usually takes less than a minute and most matings are over in under 20 seconds. In a series of observations from a pair of Serengeti leopards, copulation lasted on average for three seconds. Caracals apparently hold the record among cats, at least in captivity, where copulation has been timed ranging from 90 seconds to eight minutes; the average duration was around four minutes. There is no clear reason why caracals should have such relatively prolonged matings. Indeed, if observations from other small cats are any indication, brief matings make more sense in that they reduce vulnerability to predation. Given that there are no accounts of wild caracals mating, it remains to be seen whether the record-breaking performances of captive cats reflect what occurs in nature.

Regardless of duration, mating may occur with astonishing frequency, with large cats the most prolific. George Schaller watched a male lion mate with two lionesses 157 times in 55 hours, while a captive pair mated 360 times in eight days. Leopards mate at similarly elevated rates, with up to 70–100 copulations per day. Cheetahs are something of an exception among the larger cats. The few observed mating bouts (including those in captivity) are rare events, separated by long periods of inactivity with only three to 15 copulations taking place per day. The discreet mating behaviour of cheetahs might be a strategy to avoid drawing the attention of predators, less of a concern for leopards and lions which suffer fewer such threats. The same pattern is manifested among smaller cats, which tend to mate less frequently or for shorter periods than their larger relatives. Among those species for which we have good data, black-footed cats represent the most extreme case. Females accept males for a fleeting period of receptivity lasting only five to 10 hours, during which time they mate about a dozen times. Alex Sliwa suggests that the black-footed cat’s sparsely vegetated habitat with few refuges and many potential predators creates an incentive for getting mating over as quickly as possible.

Whether mating is discreet and concise or flamboyant and prolonged, the end result is that all female cats mate many times during a single oestrous period compared to numerous other species. But exactly why do cats have so much sex? Part of the reason is probably to induce ovulation. Most cats are thought to ovulate in response to mating (unlike spontaneous ovulators such as human females, who automatically ovulate at regular intervals). The stimulus for a female cat to release eggs is thought to come from backwards-facing barbs on the male’s penis – the reason a female often turns violently on the male at the end of each copulation. Biologists think that females require repeated stimulation before ovulation occurs, presumably achieved by repeated copulations in a limited time. For ex ample, domestic cats separated after only one mating conceive only half as often as those allowed to mate four times. Similarly, only about every third mating bout in lionesses results in conception. Interestingly, lionesses and female leopards (and tigresses too) in captivity occasionally ovulate without mating when housed next to other cats, or in response to some other social or physical stimulus, a trait known as reflex ovulation.

Induced ovulation (and perhaps even reflex ovulation, should it occur in wild females) serves to increase the likelihood that mating is successful in solitary species; there is no point wasting an egg if there are no males to be found. But it may also serve to test the quality of males. The female’s requirement for frequent copulation increases the likelihood that she will mate with numerous males over the course of her oestrous period. Recall the female leopard I watched pair off with three separate mates: all those males were territorial, mature adults which, presumably, were all worthwhile mates from the female’s point of view. Being more or less evenly matched, they had little reason to fight over her but they may, unknowingly, have competed for her at another level. It is thought that the difficulty in inseminating females puts the genetic quality of competing males on trial by ‘sperm competition’, which ensures that only the most active, healthy sperm reaches the eggs for fertilisation. Some species are believed even to have a type of non-fertilising sperm that repels or disables the sperm from rival males, though this has not been demonstrated for any felids yet.

If the quality of male suitors (or of their sperm) is comparable, the sperm of different males can contribute to a litter – the second advantage to accepting several males. Only lions have so far been shown to produce litters from multiple sires, and this appears to be rare; in the only rigorous study performed to date, 23 of 24 litters of Serengeti cubs were each sired by a single male. The single litter demonstrating mixed paternity had greater genetic heterogeneity which, in theory, would make those cubs more likely to survive a change in conditions, for example, the outbreak of a novel disease. Even so, nobody has yet collected sufficient data to demonstrate the advantage in any felid.

Less ambiguously, female promiscuity almost certainly reduces the danger of infanticide (see text box ‘Infanticide in cats’) by confusing the issue of paternity. Males encountering cubs for the first time most likely cannot recognise their offspring by smell or some other innate chemical cue, and presumably base their attitude towards them on their relationship with the mother; having mated with her probably encourages a male to believe he is the father, whether or not he actually is. There are no tests of this idea in wild individuals, although a few captive trials suggest males accept cubs on the basis of having mated with their mother.

For example, a male lion introduced into a large, naturalistic enclosure with six related lionesses mated with all the females over the course of six weeks, even though some were already pregnant by a previous, unrelated male. The introduced male treated the subsequent crop of cubs as though they were his. Even females close to birth or already with young cubs will attempt to win over new males. I once watched a lioness who was 12 hours away from giving birth consorting with three intruding males. She doggedly attempted to mate with all three, trotting invitingly in circles around them, flicking their faces with her tail and emitting a deep, purring rumble. But whether the new males were too inexperienced (they were 30 months old, young to be in their privileged position) or simply unconvinced by her displays, none mated with her. They killed her newborn litter the following day.

Infanticide in cats

Intense competition for territory among male cats (see Chapter 3) means that they cannot afford to be stepfathers. Territorial tenure is simply too brief to allow females to raise offspring sired by previous males so, in taking over turf and the females that go with it, new males typically kill all the cubs present. Removing cubs hastens the female’s return to oestrus, creating the all-important window in which a new male can make his own genetic contribution. Infanticide is best documented from lions, where incoming males typically kill 100 per cent of unrelated cubs up to the age of nine months. If not killed outright, older cubs and sub-adults, including females too young to breed, are expelled and usually die from starvation. In Serengeti lions, infanticide speeds up the female’s return to oestrus by an average of eight months. Intriguingly, though, this is not as fast as when cubs are lost for other reasons. Following a take-over, a lioness’ fertility is suppressed (even though she mates normally), on average, for four months longer than when cubs die from other causes. The postponement allows the lioness to assess whether the newcomers will endure; why conceive to them if they are not going to be around to prevent the loss of her next litter?

Among African cats, infanticide is also known among leopards and caracals (eyewitness accounts are unknown in the latter, but five male caracals killed in the Cape contained the remains of kittens in their stomachs), and it is recorded in tigers, pumas, Canada lynxes, ocelots and semi-wild domestic cats living in colonies. Indeed, it is probably practised by all cats in which both sexes are territorial, which is perhaps the reason it has never been recorded in cheetahs. The female cheetah’s non-territorial behaviour is thought to rule out the potential benefits of infanticide to males because there is no certainty she will remain nearby after losing a litter. Due to her wide-ranging movements, she is just as likely to conceive to the males of a neighbouring territory or, indeed, any male. So, although male cheetahs finding mothers with cubs occasionally batter the youngsters a little, they apparently have little incentive for infanticide, and otherwise tolerate them.

At around two months of age, these young cubs have recently been introduced into the pride by their mother. Once cubs are absorbed into the pride, they are treated communally by the adult lionesses and it is almost impossible to tell which cubs belong to each female.

Once pregnant, female cats are essentially on their own again. In all species (except, to some extent, in lions: see text box ‘Altruism versus self-interest in lions’, page 121), males play no active role in raising cubs, though of course their presence is crucial for maintaining social stability and preventing infanticidal intrusions. With the possible exception of the sand cat, female cats do not construct a den and instead seek out existing sheltered natural features in which to give birth. Just as she knows which places offer the best opportunities for hunting (see Chapter 2), a female cat probably has intimate knowledge of suitable den sites in advance. Typically, a week or two before birth, the expectant mother does the rounds of her territory or home range to inspect potential dens and make her selection. Cheetahs, leopards and lionesses usually locate their dens in dense thickets of vegetation or crevices among rocks and in kopjes. Smaller cats choose similar sites and are also able to exploit tree hollows (the sole record of a golden cat den site was inside a large, hollow log) or burrows made by other species. Sand cats den in the burrows of various foxes, desert hedgehogs and gerbils, enlarging the lair to their satisfaction; and, given their burrowing ability, they perhaps also excavate their own dens from scratch. Blackfooted cats use springhare burrows or termitaria hollowed out by aardvarks, while in the Kalahari Desert, female African wildcats, caracals and even leopards use porcupine and aardvark burrows. Saharan cheetahs conceal their cubs in the appropriated burrows of striped hyaenas, black-backed jackals and even spurred tortoises, as well as in caves scattered throughout the desert’s mountain massifs.

All cats give birth alone. Even lionesses abandon the pride to give birth (very rarely accompanied by a close female relative), often moving some distance from the core area of their range to do so. The reasons for the separation are unclear, especially given that lionesses in a pride often give birth around the same time due to their synchronised oestrous cycles. For the first six to eight weeks of their lives, lion cubs are alone and vulnerable whenever the mother leaves to forage, usually by joining up with her pride to hunt before she returns to the den. Lionesses would seem to benefit by having their cubs together, safe under the protective mantle of the pride. Perhaps the competitive, vigorous life in the pride is too dangerous for newborns, especially when older cubs and sub-adults are present; on occasion, very young cubs are killed by older cubs, though it is more a result of over-exuberant play than aggression. Yet lionesses could easily avert this threat by forming a crêche of mothers and guarding the cubs from the unwanted attention of unruly relatives (and other dangers) or by simply avoiding the main pride altogether. Indeed, two or three closely related lionesses with cubs sometimes come together for a brief nursery period prior to introducing their youngsters to the pride proper around the age of two months. Even so, as with all cats, lion cubs begin their lives knowing only their mother and are completely defenceless when she is away. Perhaps there is no significant advantage in giving birth on their own, and lionesses are simply expressing a solitary feline tendency deep in their evolutionary heritage.

Once they join the pride, lion cubs benefit from greater protection than that accorded the young of solitary cats, but it sometimes comes with costs. Lionesses share cub-raising duties and, although a female shows a slight preference for suckling her own offspring, all cubs in the pride are suckled communally. If milk is available, young lions continue to suckle until around 12 months, long beyond when their own mother has weaned them (which usually takes place around four months of age and rarely later than six). With older cubs in the pride monopolising milk, very young cubs are occasionally out-competed and starve. Similarly, competition over carcasses is intense, especially during periods when prey is scarce. Lion cubs on the Serengeti plains often die from starvation during the long, dry season when prey and water are hard to find. Under such dire conditions, young cubs cannot compete with older relatives on kills and also fail to keep up with the pride when it is forced to cover long distances to find food (see text box ‘Altruism versus self-interest in lions’, page 121). By contrast, in the nearby Ngorongoro Crater where prey is resident and generally abundant year-round, cubs rarely die from starvation or abandonment. Comparing the two populations, under 30 per cent of plains cubs survive to 12 months compared to almost 70 per cent in Ngorongoro. Survival to two years of age is about 23 and 58 per cent respectively.

Other cat species under gruelling circumstances are similarly affected. Karen Laurenson’s exhaustive research on female cheetahs in the Serengeti showed that the most successful mothers located their dens close to prey and water. A mother that denned 12 kilometres from the nearest concentration of Thomson’s gazelles ate a third as much as other mothers due to her having to commute such large distances from her litter to hunt. She was eventually forced to abandon her young cubs.

Captive African golden cat females usually have one or two kittens. If true in wild individuals, small litter size may reflect relatively low predation rates on kittens – the only serious potential threat in golden cat habitat is the leopard.

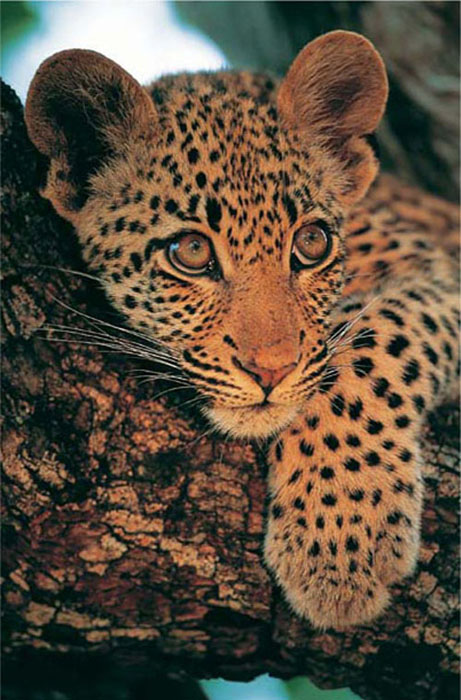

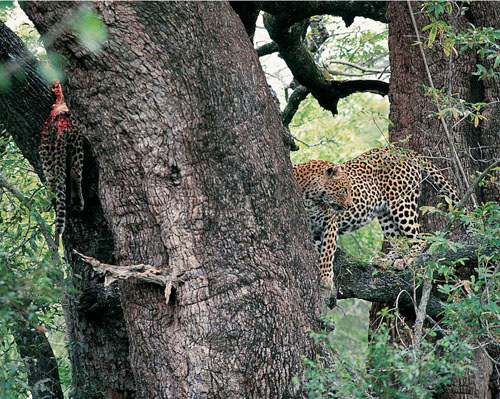

Leopard cubs are left alone for long periods when their mother goes to hunt. To reduce their vulnerability to predators, leopard cubs instinctively and expertly climb trees from the age of two months.

Cub-killers: the threat of predation

A lioness with day-old cubs, Phinda Game Reserve, South Africa. The greatest threat to very young lion cubs is predation, either by intruding males of their own species or by other large carnivores.

This female leopard consumed her cub after it was killed by lions, behaviour also observed in female cheetahs and lionesses. In such cases, the female’s behaviour indicates she does not perceive the carcass as that of her cub – females often call for their missing youngster while intermittently eating it – and that eating it simply serves the same purpose as any meal.

Starvation and desertion, however, rarely rank at the top of the list of factors that kill the cubs or kittens of most species. The principal threat to most young cats is predation, often by other members of the cat family. Where lions occur, they are usually responsible for the majority of cub deaths in both cheetahs and leopards. Leopards in turn kill the cubs of cheetahs and, less so, of lions; doubtless they also kill kittens of smaller felids, though there are few observations. Similarly, caracals are thought to be a threat to the kittens of black-footed cats. In most (though not all) cases of intra-familial predation, the killed cubs are left uneaten; the motivation for their killing is presumably to reduce competition for resources rather than for food (see Chapter 5 for details on competition between cats).

Other predators of young cats generally treat them as prey. Spotted hyaenas comprise a significant threat to young cats, and there are numerous records of their killing and eating the cubs of lions, leopards and cheetahs. Other occasional predators include any species large enough to tackle a cub or kitten, usually when the mother is absent. Black-backed jackals are recorded killing young cheetahs, caracals and black-footed cats, and a honey badger in the Kalahari was seen chasing and killing an African wildcat kitten. Large raptors sometimes feature as predators: a secretary bird was seen to kill a very young cheetah momentarily left in the open by its mother; a martial eagle in the Masai Mara was witnessed taking a serval kitten; and the Verreaux’s eagle-owl is recorded as a predator of young blackfooted cats. In a unique record from Tanzania’s Mahale National Park, a male chimpanzee snatched a very young leopard cub from a cave with the mother leopard present (who, other than growling from inside the cave, did not resist the attack). The chimpanzee eventually killed the cub but did not eat it.

Taken together, predation and other sources of mortality mean that more cubs die than survive in most populations. Calculating the mortality rate of juvenile cats is invariably fraught with problems, because they are very rarely seen before they leave the den. For most species, estimates begin only once they have emerged, which inflates the survival rate because losses in the den are unknown. Karen Laurenson addressed this question by radio-tracking 20 female Serengeti cheetahs until they gave birth and counting very young cubs still in the den. Of 125 cubs in 36 litters, 89 did not survive the period in the den; most were found and killed by lions. At four months of age, close to the point at which young cheetahs can out-run most predators, only 12 were still alive. By the time the cohort reached independence at 14–18 months, perhaps seven of the cubs were still alive; the survivors may have numbered as few as five, given that Laurenson was not certain about the fate of two animals. In other words, the survival rate for Serengeti cheetah cubs was no greater than 5.6 per cent and may have been as low as 4 per cent.

These extreme figures reflect conditions in the region. The density of predators in the Serengeti is high and the plains offer few refuges against them; den sites such as kopjes, luggas (river valleys) and thickets are thinly spread and also attract lions or spotted hyaenas. Further, once they have emerged, cubs are visible to predators from as far away as two kilometres. Despite its common depiction as sub-optimal cheetah habitat, denser woodland offers a refuge for mothers with cubs; its mixed vegetation affords an abundance of suitable den sites, dens are less likely to be discovered and emerged cubs are less likely to be seen. In the humid woodlands of northern KwaZulu-Natal, almost 70 per cent of cheetah cubs that emerge from the den survive to independence. Although this figure excludes losses in the lair (the most vulnerable period), it is over three times the survival rate of Serengeti cubs after emergence; Karen Laurenson’s data showed that, at most, only 19 per cent of Serengeti cubs survived once they left the den.

No other study has matched Laurenson’s for such a precise estimate of cub mortality in any cat species; but even so, such severe losses are unlikely to apply to most populations of felids. Ninety-five per cent mortality means that a female will lose 19 cubs for every one she manages to raise, a ratio that’s probably unsustainable for any cat. In fact, the reason cheetahs persist on the plains at all may be due to overflow from surrounding woodlands where cubs probably enjoy greater rates of survival (a question currently being investigated by researchers). For leopards, Ted Bailey estimated that half of cubs in the Kruger National Park survived to independence. Long-term records from the adjacent private Londolozi Game Reserve suggest higher rates, at least for cubs observed from about the age of eight weeks (therefore excluding some losses taking place earlier in the lair). There, the famous female leopard known simply as ‘The Mother’ had at least 16 cubs in nine litters between 1979 and 1991. She reared 12 to independence. Importantly, though, Lex Hes, who observed the Londolozi leopards for many years, regards her as a particularly successful mother; he agrees with Bailey’s estimate of 50 per cent survival of cubs for females in general. Among the seven smaller species of African cats, estimates of kitten survival remain a guess.

Growing up: learning to be a cat

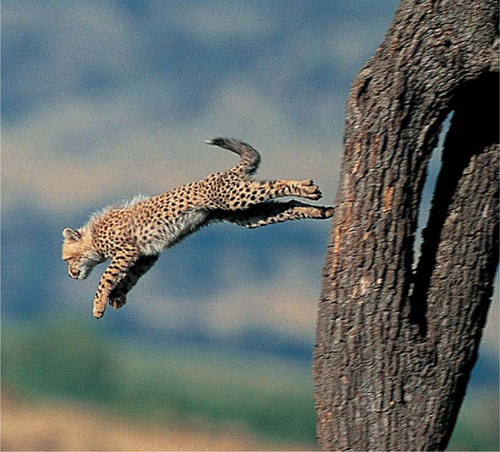

Despite their reputation for being feeble, cheetah cubs are actually very robust, and like all young cats, engage in furiously energetic play sessions in which trees and other high points are favoured focal points.

Life as a young cat is hazardous, but life-threatening events are fairly rare episodes and most of their time is spent resting, feeding and playing. Regardless of species, cubs or kittens usually leave the den and begin accompanying their mother from about the age of six to 10 weeks. Young cheetahs are rarely left alone from that point and move with their mother constantly. Lion cubs similarly tend to be with their mother or other members of the pride most of the time, though hunting females may leave crêches of young cubs alone until they reach four to five months of age and are better able to keep pace. In leopards and most likely the smaller cat species, even larger cubs are left to their own devices more often. Although cubs often travel with their mother, a female leopard setting out to hunt usually leaves them behind and returns later to escort them to her kill.

A lion pride scavenges the carcass of an elephant that died of natural causes, northern Botswana. Like most cats (with the exception of cheetahs), lions are not averse to putrefying meat and will remain with such a bounty for days on end. In this case, the pride fed for a week before leaving the remains to crocodiles and spotted hyaenas.

A female cheetah (far right) oversees her cubs’ hunting attempts after releasing a live young springbok. Although this appears cruel to human observers, such opportunities are a crucial part of the training that young cats must undergo to survive as adults.

Travelling with their mother helps equip cubs with the critical skills they will need to survive as adults. As they mature and cover increasingly more ground, young cats are exposed to danger, prey and conspecifics, honing their instinctive responses to each under the relative protection of their mother’s presence. In particular, mothers assist their youngsters in learning how to be efficient killers. Mother cats begin releasing live, sometimes disabled, prey in front of their offspring early in their development: from as young as four weeks for domestic kittens in semi-wild colonies, to around four to five months for big cats such as leopards and cheetahs. Tim Caro tested the effects of this predatory training in domestic cats, discovering that kittens raised with their mother were much more efficient at dealing with mice than kittens without their mother. By 12 weeks of age, kittens with mothers had killed five times as many mice as those where the mother was absent. Kittens raised by their mother benefited from maternal encouragement – vocalising reassuringly to draw the kittens’ attention and prompting them to investigate the prey – and from mothers intervening to assist clumsy youngsters when the mouse was getting away.

Caro later investigated this phenomenon among cheetahs in the Serengeti. The same experimental set-up – mothers present versus mothers absent – was impossible to replicate in wild cheetahs, but Caro demonstrated how mothers gradually release more live prey for their cubs as they age: from around 10 per cent of her catches when the cubs were four months of age to around 40 per cent at seven months. At the same time, the proportion of prey caught by the mother but killed by her cubs increased over time as they became more proficient in applying a suffocating bite. Although the process has not been as precisely documented for other felids, it is doubtless similar, and many observations exist of lionesses and mother leopards releasing live prey for their cubs.

Eventually, the young cat reaches the point where it can hunt on its own. The age at which cats attain independence varies (see Species Profiles, page 18–31), but families ultimately part ways because the reproductive imperative has come full circle. Female cheetahs and leopards (and likely those in other species) may mate and conceive while still accompanied by older cubs, but they invariably leave their adolescent offspring when they are about to give birth to the next generation. It is the culmination of a sometimes protracted process in which the young cat spends increasingly more time on its own until all contact with the mother is finally severed. Newly independent cats face a suite of challenges and dangers and, as discussed in the next section, many will not make it to adulthood.

Altruism versus self-interest in lions

Male lions in Ngorongoro Crater (and, indeed, wherever they enjoy reliable foraging) often allow young cubs to feed on carcasses while repelling the rest of the pride. The classic portrayal of males ‘always feeding first’ is correct in that they monopolise kills when they can, but under most conditions they make an exception for small cubs. Apparently altruistic, the behaviour is inherently selfish because it improves the likelihood of their cubs surviving, thereby enhancing their own genetic ‘fitness’. But, of course, such vested interest is the underlying reason for the great majority of behaviours we often interpret as selfless and it usually disintegrates when individual survival is at stake; when prey is particularly scarce, males prevent even young cubs from access to kills. Interestingly, lionesses almost always allow their cubs to feed, no matter how hungry they are themselves. Their energetic investment in producing cubs is greater than that of males, and it takes truly desperate circumstances for a female to forsake her offspring. Because lionesses do not carry cubs to kills nor bring kills to their cubs, the critical threshold is reached when females have to cover prohibitive distances to feed themselves. If cubs cannot keep up, the female has no choice but to abandon them.

Into adulthood: dispersal and survival

A female leopard confronts her young adult son, a necessary part of his gaining independence. At 24 months, the young male is no longer welcome in his natal home range, and escalating conflict with his mother and especially with adult males will soon force him to disperse.

The path to adulthood for young cats is surprisingly poorly understood but, in general, the feline pattern is one of female philopatry and male dispersal: sub-adult females are more likely to stay in or near their mother’s (or pride’s) range while males move further afield to establish a range. As a general rule, the pattern probably applies to all felids but it has been thoroughly investigated only in lions and cheetahs, and less so in leopards and servals.

In solitary-living servals and leopards, the adult female usually tolerates her female offspring utilising part of her territory when the youngsters gain independence, though they rarely interact directly with one another. To the mother cat, tolerating a female relative nearby is less hazardous than risking encounters with an unfamiliar newcomer; adhering to the ‘dear enemy’ principle (see Chapter 3) carries even fewer costs when the neighbour is a relative. It potentially also increases the mother’s overall reproductive output (her fitness) by enhancing the survival prospects of her female offspring and elevating the likelihood that they will in turn raise their own cubs. For dispersing adolescent females, inheriting a portion of their mother’s territory has considerable advantages during a period when the chances of starving or being killed by other carnivores suddenly escalate. They already know the area intimately and do not need to invest energy in locating and ‘mapping’ those features that are critical to their survival: areas where prey congregates, the location of hostile neighbours, and the whereabouts of waterholes, rest sites, refuges from predators and so on. Given the limitations of space, it is likely that some young females do not end up settling near their mother (and, most probably, their older sisters), but the process is still insufficiently understood in any felid to estimate relative figures.

Males, on the other hand, are always evicted (at least, the limited data available indicate this is so). Increasing aggression from the mother and resident male or males pushes young male leopards and servals from their natal range into a dangerous phase of nomadism. The pattern guards against young males staying put and breeding with their female relatives, but it comes with considerable costs to them. In South Africa’s Phinda Game Reserve, sub-adult male leopards are almost three times as likely as females to die during this period; young males die from a combination of natural violence and being forced into marginal areas such as farms where the chances are high that they will be killed by people. Phillip Stander found a similar outcome for two adolescent leopard males he monitored in north-eastern Namibia. Both stayed in their mother’s range for 6–8 months after independence before dispersing 25 and 162 kilometres respectively. The first died in his new range after six months while the second was killed for cattle-raiding five months later.

In this unusual case, the resident pair of mature males has accepted a sub-adult pair (left and standing) recently evicted from their pride, Duba Plains, Botswana. Given that larger coalitions have longer territorial tenure, access to more females and sire more surviving cubs than smaller coalitions, the ‘pact’ might reflect rising pressure on the resident coalition from intruding males.

The pattern of philopatric females and dispersing males also applies to lions. Young lionesses occasionally wander for a period near their natal range but most will eventually end up incorporated in their original pride. In the Serengeti, about two-thirds of female sub-adults are recruited into their mothers’ prides while the rest emigrate, either to avoid mating with their fathers and uncles or to evade new males which have taken over the pride. Dispersing females usually establish new prides nearby, but their reproductive success is significantly less than for females that stay put; reproductively, the best strategy for lionesses is to remain with the pride in which they were born.

Male lions, however, always leave. Between the ages of two and four, young males are evicted, either due to increasing aggression from their adult relatives, both males and females, or in response to a take-over by new males. Bereft of their pride, sub-adult males enter a similar nomadic phase as experienced by young male leopards. This is a perilous period during which they risk being killed by territory holders if they are caught interloping on occupied land. Intriguingly, Paul Funston and Gus Mills found that young males in southern Kruger National Park do not always become drifters, but sometimes form ‘lodger groups’ close to their natal range. While they must still avoid their former pride or risk a potentially deadly reunion, inhabiting the vicinity of their original home probably confers similar advantages to those enjoyed by non-dispersing females; they already know the best areas to search for prey and are well equipped to avoid other male lions in the region because they are familiar with their rivals’ status and movements. Ultimately, 80 per cent of the male lions in the Kruger study established territories close to their original pride range; by comparison, most Tanzanian males established territories at least 120 kilometres from where they were born.

Disease in cats

Investigating disease in cats is problematic because researchers rarely find dead cats. Even so, indications from wild populations suggest that significant loss to disease is a rare event. As in all species, naturally occurring diseases probably cycle continually in cat populations with relatively minor impacts. Most individuals survive exposure with a small percentage of individuals succumbing; those that die are often already compromised and vulnerable from other factors such as injury, starvation or infection. Some pathogens persist in populations with no effect at all, Feline Immunodeficiency Virus (FIV) being a case in point. Despite sometimes hysterical press reports about AIDS in lions, FIV has been present in many wild lion populations for prolonged periods, possibly for thousands or even millions of years, and most adult lions have the virus. Unlike HIV in humans, FIV produces no clinical effects and does not affect the survival of lions. FIV has also been found in African leopards where it is similarly innocuous.

Many cats suffer from occasional outbreaks of ‘mange’, caused by skin-burrowing mites. Mange is usually innocuous but severe outbreaks sometimes lead to fatal secondary infections.

Exotic disease, usually introduced by people or their domestic animals, has the potential to cause far greater damage. In 1993–1994, an epidemic of canine distemper virus (CDV) raged through the lions in East Africa’s Serengeti-Mara ecosystem, killing one third of the population, some 1 000–1 100 animals. The outbreak probably originated in the 30 000 village dogs living on the periphery of the protected area. Lions are particularly vulnerable to novel diseases because of their rich sociality and high densities; constant interaction among lions facilitates transmission. Fortunately, the solitary lifestyle of other cats probably reduces their vulnerability, and the CDV episode apparently did not affect Serengeti leopards or cheetahs. The exotic livestock disease bovine tuberculosis (bTB) may pose a significant threat to lions in the Kruger National Park and there is at least one case of infection in leopards. The long-term implications of bTB on cats in Kruger are still being investigated.

An aged lioness close to the end of her life, Savute, Botswana. Provided they can keep up, the support structure of the pride means that lionesses are more likely to die from advanced old age than infectious disease.

It is still unclear how Kruger males avoid breeding with their female relatives but, when given a choice, it seems that males prefer non-relatives. Long-term observations in the Serengeti show that, instead of being ousted from their prides, some young males voluntarily depart to avoid inbreeding. Maturing coalitions of males have been known to quit prides even when there were no resident males driving them off and when their own pride contained more reproductively available females than the unrelated prides in which they eventually settled. Perhaps a similar choice-based mechanism is at work among the Kruger male lions as they gain territory and access to females, although so far it has not been documented.

At one year old, these young cheetahs (right and left) will soon be independent. The female cub (left) will ultimately pursue a solitary existence while the male (right) will likely attempt to form a coalition with another single male.

Among cheetahs, female philopatry and male dispersal hold true, even allowing for the vast home ranges of the mothers. Newly independent adolescents, females and males, usually stay together in a sib-group that remains temporarily in their mother’s range. Grouping in young cheetahs increases their chances of making a kill while still developing their hunting abilities, though they eat no more than corresponding singletons; sib-groups kill larger prey more often, but they have to share the spoils with their siblings. There are, however, further advantages to staying together. The individuals in a sib-group each devote less time to watching for danger and are more relaxed than young females on their own; and groups are less likely than individuals to be harassed by spotted hyaenas or by adult male cheetahs. Even so, the advantages of sociality are not compelling enough for females to remain permanently in the sib-group and they always leave their brothers to adopt a solitary lifestyle as they approach sexual maturity. Just as in lionesses, leopards and servals, they usually inherit some of their mother’s range; in the Serengeti, the ranges of young females overlapped those of their mothers’ by an average of 62 per cent and their sisters’ by 30–90 per cent. Young males older than three rarely stayed in their natal range, probably because of the presence of adult territorial males. Sub-adult males in the Serengeti dispersed at least 18 kilometres from their mother’s range while distances recorded in Kenya’s Masai-Mara reached 40 kilometres.

If they reach adulthood, cats continue to face threats throughout their lives, but the risk of dying from natural causes declines sharply from the precarious periods of cubhood and dispersal, then rises again as cats grow old (see Species Profiles for longevity figures, pages 18–31). As covered in earlier chapters, some will die in clashes with their own kind over territory or from mortal injuries incurred in hunting mishaps. Starvation and disease (see text box ‘Disease in cats’, page 125) claim a lesser percentage of adult cats and some will be killed by other carnivores; this complex relationship is covered in the next chapter.