The enduring leopard is the most widespread of big cats with a range that extends from the southern tip of Africa to the Russian Far East and includes most of tropical Asia. Even so, leopards have lost millions of square kilometres of their former range as a result of human activities.

Humans have lived alongside cats in Africa longer than anywhere else on the planet. Modern Homo sapiens arose only some 200 000 years ago, but upright, bipedal humans of the genus Homo have occupied Africa for at least 2.3–2.5 million years. Just as in Homo sapiens, early members of the genus were intelligent and large bodied, and almost certainly lived in complex, extended family groups. At some point early in human evolution, our ancestors also developed the tools and co-ordination to hunt large mammals co-operatively, but even before then, humans and large cats must have encountered one another constantly. For millions of years in Africa, we have occupied the same habitats, stolen one another’s kills, competed for the same species as food and even killed one another (see text box ‘Man-eating cats’).

Man-eating cats

Only two African cats, the lion and leopard, kill people (otherwise, it’s recorded only for tigers, pumas and, rarely, jaguars). There is no record of wild cheetahs ever killing a human, probably because of their narrow prey preference for antelopes and their defencelessness against larger competitors; humans are both too strange and too dangerous to be considered fair game. In general, this also applies for lions and leopards; all big cats recognise humans as a formidable threat and, given the degree of opportunity, attacks on people are surprisingly uncommon. However, under certain circumstances, lions and leopards do treat people as prey. Often such incidents are provoked or are committed by an injured or otherwise debilitated ‘rogue’, but man-eating may be adopted by perfectly healthy cats when their natural prey has been eradicated. This was probably the key factor behind the killing spree of the famous man-eaters of Tsavo, two male lions that killed around 28 railway workers (not 135, as usually reported) in southern Kenya in 1898. Rinderpest had wiped out most of their natural prey and, faced with little alternative and ample opportunity, local lions turned to humans for food.

Even today, the same scenario occasionally gives rise to chronic man-eating in which the losses can be quite staggering. In Tanzania, lions kill up to 100 people every year, most in south-eastern Tanzania where intensive subsistence agriculture has depleted wild ungulates. The problem is thought to be equally severe across the border in northern Mozambique. In most of Africa, people living with lions regard them primarily as a threat to livestock (see main text) but pockets of persistent man-eating are probably more common than widely assumed.

White lions and king cheetahs:

conservation or exploitation?

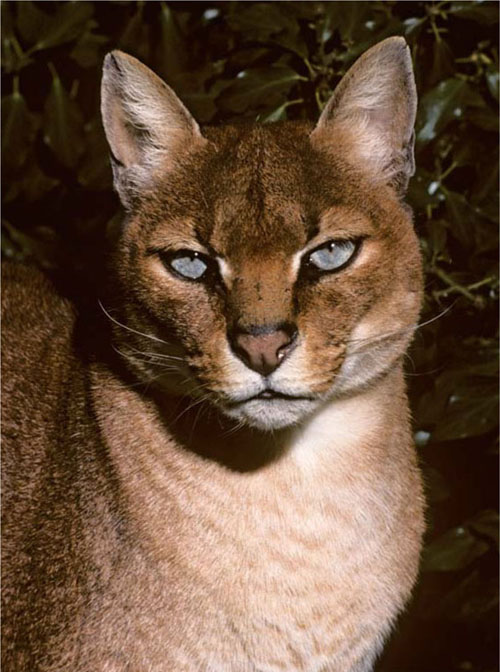

Unusual colour variations arise occasionally in all cat species (melanistic individuals occur relatively often in leopards, golden cats, servals and jungle cats, to list African examples only), but few are as celebrated as white lions and king cheetahs. Both arise from a recessive mutation to a gene that contributes to the colour or pattern of the coat, and both can occur in a litter of normally coloured siblings. Aside from colour, white lions and king cheetahs are no different from other members of their species, yet this has not prevented misguided and unscrupulous efforts to breed them in captivity. Promoted as ‘precious rarities’, they are valued by some zoos and trophy hunters willing to pay exorbitant prices to exhibit or shoot them. The demand has fuelled deliberate inbreeding to produce more cubs in which the only motive is profit. Despite the claims of most ‘breeding programmes’, propagating unusual morphs does nothing to conserve their species in the wild. Proposals to reintroduce them are worthless, given that returning captive-bred big cats to the wild usually fails, and that re-stocking can be accomplished safely by translocating wild-caught individuals from elsewhere (see text box ‘Reintroducing cats’, page 167). The reality is, from a standpoint of conserving the species, breeding white lions and king cheetahs is valueless.

Despite this, our effect on cats (and African wildlife in general) has been inconsequential for the great majority of human evolutionary history. No human species prior to Homo sapiens has been sophisticated or numerous enough to cause widespread extinctions and, until recently, even our own species has been constrained by ecological conditions such that we simply could not become too abundant or too influential. The total number of humans on the planet 10 000 years ago (8000 BCE) is thought to have been somewhere between five and 10 million, most of them widely dispersed in small groups of nomadic hunter-gatherers. One thousand years later (around 7000 BCE), intensive agriculture and the domestication of livestock had given rise to the first densely settled areas in the Middle East, yet the world population still could not have exceeded 20 million people, and the largest towns housed only 1 000–2 000 inhabitants.

By 2 000 years ago (0 BCE/AD), the population of the world was about 300 million, the same number of people in the United States in 2005. Large civilisations with sophisticated technology were scattered across the globe and they must have wrought significant effects on their environment. Contrary to a popular Utopian myth, Africa’s indigenous peoples developed advanced, sedentary societies that exploited wildlife long before European colonisation took place. It seems that few African cultures hunted big cats as food, but where people intensively hunted their prey species, cat numbers likely suffered. Exacerbating these local declines, recreational hunting of lions and leopards by societies such as the ancient Egyptians resulted in the first signs of range loss among large cats. Lions had already disappeared from parts of the Nile Valley when the Roman Empire began collecting North African cats in the thousands for their gladiatorial games.

Raising the stakes substantially, domestic cattle have been an element of the African landscape for millennia. Intriguingly, recent genetic analyses show that African cattle arose locally from a now extinct species of African wild ox rather than, as long believed, via later introductions from the Middle East and western Asia. The domestication of cattle in Africa is traced to the border region of modern-day Sudan and Egypt some 7 000– 9 000 years ago; from there, cattle spread gradually southward into sub-Saharan Africa, changing the landscape forever. Livestock competed with the natural prey (various herbivore species) of cats for the same food, and cats that killed livestock were dispatched. Even today, pastoralists using traditional weapons make short work of stock-raiding lions and leopards.

Even so, the impact wrought by people must have been extremely localised until very recently. At the time of Christ, a resident of even the largest, most complex civilisation in Africa would need travel only a kilometre or two from the city limits to encounter wildlife populations largely unaffected by people. Dense congregations of cattle probably displaced wildlife, but people had still not become so numerous or technologically advanced that their effects were anything other than local. Even by 1750, only an estimated 103 million people lived in Africa – 27 million fewer than the population of modern-day Nigeria. With the exception of localised pockets (albeit, some quite extensive) where humans and their livestock reached high densities, all African cats probably still occurred across the great majority of their respective historical ranges until the time of European colonisation.

Europeans brought with them both an attitude to wildlife and the technology to exploit it that would produce the first widespread, devastating effects on Africa’s fauna. In the three-tiered hierarchy of imported European monotheistic religions – God, Man, Nature - wildlife existed entirely to benefit people. Combined with European farming practices, the advent of firearms and the notion of hunting for sport, it did not significantly transform the key threats to cats but it did spawn the uncontrolled proliferation of those hazards. Europeans propagated three main threats to carnivores – habitat loss, hunting of prey and direct persecution – that have been associated with human presence for millennia, but never before with the same intensity and efficacy. Natural habitat was cleared for large-scale intensive agriculture, livestock husbandry and forestry, while prey populations were hunted for meat, sport and ultimately to make way for more domestic herds. In parallel, the persecution of carnivores reached new heights, chiefly in the perceived defence of livestock as well as for sport. For cats, especially the larger species, it began a pattern of local extinctions and range retraction that persists today (see ‘The status of cats’, page 160). The same relentless trinity of threats caused by man remains the principal reason.

Modern threats: habitat destruction, loss of prey and persecution

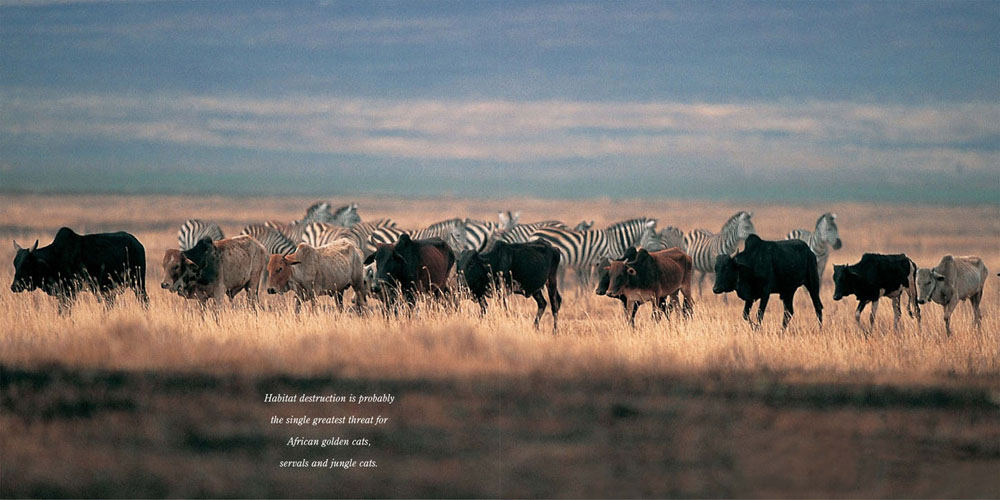

Cats cannot survive without suitable habitat. Predictably, the combined loss of habitat and prey has wrought particularly severe effects on large cats with their greater ecological demands. John Seidensticker calls this the ‘Large Carnivore Problem’. Large predators require expansive tracts of suitable habitat with ample prey populations, a recipe for wilderness that is increasingly scarce in Africa. But the same forces affect smaller cats and indeed, for those species with narrow habitat preferences, the consequences may be grave. Habitat destruction is probably the single greatest threat for African golden cats, servals and jungle cats. Deforestation in West and Central Africa has destroyed large areas of golden cat habitat, resulting in extensive swathes of rainforest converted to savanna; the forest hugging the West African coast is particularly degraded, with pockets of undisturbed stands isolated like islands in a sea of recently converted savanna. Similarly, the wetlands, marshes and riparian habitat required by servals are under extreme pressure in much of Africa, drained or dammed for agriculture, cultivation and development. In Egypt, the same modification of wetlands is thought to be responsible for local extinction of the jungle cat from the more densely inhabited areas of the Nile.

The presence of domestic livestock has far-reaching effects on wild cats: most obviously, livestock falls prey to large cats, resulting in widespread persecution in reprisal; stock also competes for the same resources as cats’ natural prey, such as these zebras in the Masai Mara National Reserve; and the clearing of habitat and attendant loss of natural prey to create room for livestock drives the local extinction of some cats, particularly habitat specialists such as the African golden cat.

African cats in Asia

Apart from the African golden cat, serval and black-footed cat, all African felids are found also in Eurasia and the Middle East (see Species Profiles for distribution maps, pages 18–31); indeed, some of them probably arose in Asia and subsequently colonised Africa. Leopards, caracals, jungle cats and wildcats (called Asian wildcats, but the same species) are widespread and reasonably common in many areas, although, as in Africa, all have experienced extensive range loss at the edges of their respective Asian distributions. The sand cat is restricted to arid parts of Central Asia and the Middle East where the remoteness of its preferred habitat means that it is probably least affected. Lions and cheetahs have suffered massive range collapse in Asia; up until the 20th Century, both occurred in the Middle East, across Central Asia and into eastern India. Today, the Asian distributions of both species are restricted to a single, though different, country. All Asiatic lions now occur in western India’s Gujurat State in the 1 412-square-kilometre Gir Wildlife Sanctuary and National Park, and surrounding areas; their numbers are estimated at around 300. The situation of the Asiatic cheetah is more dire. Only an estimated 50–60 individuals survive, all in the arid central plateau of Iran. Loss of prey from over-hunting is the principal threat to Iran’s cheetahs, though they also suffer significantly from persecution by herders and hunters, as well as from a surprisingly high incidence of being killed on roads.

Clearly, preserving suitable natural habitat is key to protecting cats and, surprisingly, it need not necessarily be pristine. Many cat species are quite tolerant of some habitat change – provided their prey base is unaffected. In Gabon, Philipp Henschel discovered that the species most valued by the bush-meat trade – small and medium-sized forest duikers – are precisely the same species preferred by rainforest leopards. In some intact stands of apparently pristine forest where the pressure of bush-meat hunting is intense, leopards have vanished. Almost certainly, competition from people for the same prey – as opposed to direct persecution of leopards themselves – is the smoking gun. Henschel’s observations are not unique. Uganda’s Bwindi Impenetrable National Park still shelters mountain gorillas, chimpanzees and elephants but lost its leopards in the 1960s, and they have similarly vanished from the otherwise intact rainforests of southern Cameroon in the last two decades.

In marginal habitat, the eradication of prey has particular significance. Across North Africa and the arid Sahelian savannas bordering the southern Sahara, recreational hunting of desert ungulates is popular, not only among local cultures but also with large, well-equipped hunting parties from the Middle East whose objective is numbers; the more antelopes bagged, the better the outing. Under intense hunting pressure, antelope populations have declined precipitously, driving the already few desert cheetahs towards extinction. The relict Egyptian cheetah population has been extirpated from more favourable areas of the coastal desert and larger oases due to the extermination of gazelles, and now persists only in the remote Qattara Depression of the Egyptian Western Desert, if at all. Assuming extinction has not already occurred, cheetahs are almost certainly doomed in Egypt unless urgent measures are taken to control the hunting of their prey species. Loss of prey is also the principal threat to the last Asiatic cheetahs in Iran (see text box ‘African cats in Asia’, above).

The third major threat to cats, the direct persecution of cats by people predominantly in conflict over domestic animals, is now so pervasive that biologists use shorthand to discuss it – HWC, standing for ‘Human-Wildlife Conflict’ (which encompasses conflicts between people and all wildlife, not carnivores exclusively, though they comprise the majority). HWC affects all African cats – even the sand cat is occasionally killed in gin traps set around poultry pens in remote regions of the Sahara – but predictably the effects are most severe on the three large species. Lions, leopards and cheetahs do kill livestock which, naturally, people take measures to curtail.

The lion is particularly affected; large, dangerous and group-living, lions are a genuine and expensive threat to people and their cattle. Working in communal areas adjacent to Waza National Park, Cameroon, Hans Bauer found that annual losses of cattle to lions comprised only about 3.1 per cent of all domestic animal losses to all factors, but represented almost a quarter of financial losses; cattle are valuable and the loss of one causes greater suffering than the loss of many sheep. Leopards and cheetahs generally cause less damage to herders because adult cattle are beyond their reach, but they take calves and small stock. After lions, leopards are the second most costly predator to Ju/Hoan San communities in arid north-eastern Namibia; during one study, they accounted for 100 per cent of dogs killed, 97 per cent of chicken losses and 42 per cent of cattle losses. Also in Namibia, Laurie Marker found that cheetahs were responsible for only three per cent of the livestock losses to predators.

Of course, whether losses are suffered by a subsistence pastoralist family or large-scale commercial ranchers, the percentages are academic. In many areas, predators are not responsible for a majority of losses – livestock die from many factors including disease, poor husbandry, complications during birth, injury and so on – but the ‘predator problem’ is often the one aggrieved herders or ranchers feel is most easily addressed. It does not take much to kill a cat. Today most herders carry firearms, and predators are opportunistically shot or hunted down with the help of dogs; in Namibia, ranchers are known to shoot cheetahs from the air in micro-light aircraft using automatic rifles. Even where firearms are illegal or too expensive, baited cages and gin traps are an effective and economical alternative. Most insidious and destructive of all methods, lacing carcasses with poison has gained rapid and recent currency across much of Africa. The widespread availability of inexpensive, legal poisons such as those used to dip livestock for parasites is an irresistible solution to even the poorest pastoralists. The consequences for cats are acute.

Trade in cats

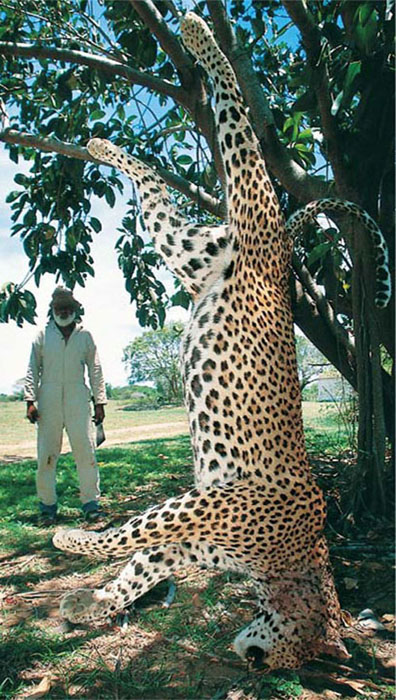

Distinct from trophy hunting (see ‘Protecting the unprotected’, page 166) or persecution by livestock herders, the intentional hunting of cats for their fur represented a major threat until very recently. At its climax in the late 1960s, the fashion for spotted cat furs in Europe, Japan and the US saw over 50 000 leopards killed each year in Africa; cheetahs and servals were also harvested in large numbers. Fortunately, public tolerance for cat furs waned during the 1970s and today there is effectively no international commerce in African cat skins for fashion (though in February 2004, the New York Times displayed spectacular ignorance in celebrating a revival of cat fur coats in Manhattan).

Even so, hunting cats for skins and other parts remains widespread in Africa. Leopards, African golden cats and caracals are increasingly common as ‘luxury’ bush meat and fetish items in the markets of West and Central Africa. Throughout northern Africa and the West African Sahel belt, cheetah, leopard and serval parts (especially skins and claws) are sought after, mainly for domestic ceremonial and medicinal purposes, but also by foreigners. In Djibouti, leopard skins are bought mainly by French military personnel who smuggle them to Europe – a single day spent by investigators in tourist shops in 1999 counted 44 skins on display. When local hunting pressure escalates to meet a wider market demand, overharvesting of cats can result in local extinction.

The status of cats: range loss, numbers and trends

The sand cat’s preference for extremely arid, remote regions of the Sahara means that it is probably the African felid least likely to be affected by human activities in the future.

Although extremely resilient to persecution in southern and East Africa, caracals are not faring nearly as well in more marginal habitat. They have disappeared from over a third of their historic range, and the remaining populations in northern and West Africa are in peril.

Large, viable populations of lions are mostly restricted to the most extensive reserves and surrounding areas. Effective conservation of lions now relies in large part on securing their safety in unprotected areas.

The African wildcat is widespread, common and relatively safe from ‘traditional’ threats to cats. Ironically, though, hybridisation with domestic cats threatens its survival as a species.

It is impossible to estimate accurately the original abundance of any cat species, but by extrapolating where natural habitat occurred a few centuries ago, we have a reasonable idea of the historic distribution of cats in Africa. Combined with historical accounts of occurrence, we know most about the distribution of Africa’s three big cats.

With the exception of a few natural gaps, lions, leopards and cheetahs originally occurred across the entire continent. Lions never penetrated the interior of rainforest nor that of the Sahara, though they naturally occurred at the periphery of both habitat types. Lions survived in the Sahara around Niger’s Aïr Mountains until the 1930s, and occupied the ecotone between forest and savanna in Gabon until only a decade ago. Cheetahs are naturally absent from the equatorial rainforests of Central Africa and West Africa’s forested coastal belt, while the most versatile of the three species, the leopard, is excluded from only the most arid areas of the Sahara. We know less about the smaller felids but the same habitat reconstructions give us a reasonable idea of their likely original occurrence. The historical range of the caracal and African wildcat essentially mirrored that of leopards, except both are naturally excluded from rainforest (perhaps because the African golden cat has always filled the mesopredator niche there; see ‘Escaping competition’, page 140). Serval distribution has always been more restricted; they naturally avoid arid areas and forest. Similarly, African golden cats occur only in forested habitat, jungle cats in Africa probably never ranged beyond the Nile Valley and surrounding oases, and the remaining two species, sand cats and black-footed cats, have always been restricted to arid areas.

What is the situation today? Attempts to estimate the change in populations of cats are plagued by very limited data on their numbers today, let alone prior to declines. However, we can be confident that lions and leopards historically existed in contiguous populations which, continent-wide, probably numbered in the millions. Occurring naturally at lower densities, cheetahs were never as numerous as leopards or lions, but they probably numbered in the mid- to high hundreds of thousands. Attempting to estimate the original numbers of the smaller felids is essentially meaningless. For the three big cats, a scattering of accurate density estimates from across their range provides a meaningful starting point; we cannot claim the same for the smaller species.

However, we are able to examine the trends in distribution by comparing probable historic range to current occurrence. Justina Ray and I recently mapped the loss of range for the six larger African felids (we excluded the three smallest species because their current range limits are poorly known, and because the larger carnivores have generally suffered most at the hands of people; and we omitted the mid-sized jungle cat because it exists primarily outside Africa). The results are far from perfect – there are major gaps in the distribution data even for well-known species like lions and cheetahs – but they paint a bleak picture for cats. At best, all are now extinct in close to a quarter of their original range. Of the six species, servals are least impacted with about 24 per cent range loss, while leopards and caracals have disappeared from about 37 per cent of their range. African golden cats have lost 44 per cent of their habitat, chiefly to deforestation. The worst affected felids are the cheetah and lion, with an estimated 76.5 and 83 per cent loss in range respectively.

Cats have been most impacted in north-east Africa, north of the Sahara, West Africa and South Africa. Today, lions occur only south of the Sahara, where recent estimates of their numbers range from 16 500–47 100. Only six contiguous populations, three mainly in Tanzania, are thought to number at least 1 000 individuals: Selous Game Reserve and surrounds, Ruaha-Rungwa ecosystem (Tanzania), the Serengeti-Mara ecosystem (Tanzania-Kenya), the Kafue-Zambezi-Luangwa complex (Zambia), the Okavango region (Botswana) and the Greater Kruger ecosystem (South Africa and Mozambique). In all likelihood, there are fewer than 1 000 lions in all of West and Central Africa. Cheetahs occur over a greater range, but they are also now extinct or relict in North Africa and much of West Africa, and their total numbers are fewer: current estimates total 12 000–15 000 (though, as for lions, the data for most regions are very poor). Of Africa’s three big cats, leopards are the most resilient, yet they are reduced to a single relict population in North Africa and have been lost from large parts of West Africa. No Africa-wide estimate of leopard numbers is reliable, but conservatively they number at least 100 000. Even so, as with all the large cats, an overall aggregate is relatively meaningless. Many populations of cats are too isolated, too small or too beleaguered to be viable.

Suffering from intense pressure for its forested habitat, the golden cat is thought to be naturally rare and is probably the most threatened of the smaller felids in Africa. Similarly, the jungle cat’s extremely restricted African range, all of it under pressure from humans, places it in peril though it is widespread in Asia. The African wildcat is widespread, common and not considered threatened in any formal assessment of its status, but hybridisation with domestic cats threatens its survival as a genetically pure form. Occupying the middle ground in terms of status, servals and caracals are still relatively widespread and considered common throughout much of their range; both species are extinct or reduced to low densities in North and West Africa. The status of black-footed cats is poorly known; populations are probably relatively secure, though they are unlikely to reach high densities given the constraints imposed by arid habitat, and their limited natural range is vulnerable to human activities, particularly the expansion of agriculture. The sand cat is possibly the only African felid whose population may not decline in the next 50 years. They inhabit remote areas far from serious human influence and, unlike most cats, their habitat is not being degraded. Indeed if desertification in North Africa continues its inexorable spread, they may be the only African cat whose range will increase as a result of human activities.

Except, perhaps, for the sand cat, continued loss of habitat and the concomitant decline of Africa’s cats is almost assured. By the middle of 2005, Africa had 14 per cent of the world’s human population, around 906 million people. But more to the point, Africa’s population is growing faster than any other region’s, on average around 2.6 per cent each year between 1975–2005, compared to just over 1.0 per cent for North America and 0.25 per cent for Europe. Of the 10 countries with the world’s fastest growing populations, five are African; of the 12 countries with populations expected at least to triple between 2005 and 2050, 10 are in Africa. Wherever Africa’s human population grows – and no African country currently has a negative growth rate – most cats will decline. The Population Division of the United Nations predicts that Africa will have 1.9 billion people by 2050. That figure represents the ‘medium’ projection; it could be as low as 1.6 billion or as high as 2.2 billion. Regardless, in most of Africa, there will be millions more people requiring more space and resources. The question is, will there be anywhere left for cats?

Conservation: the future of Africa’s cats

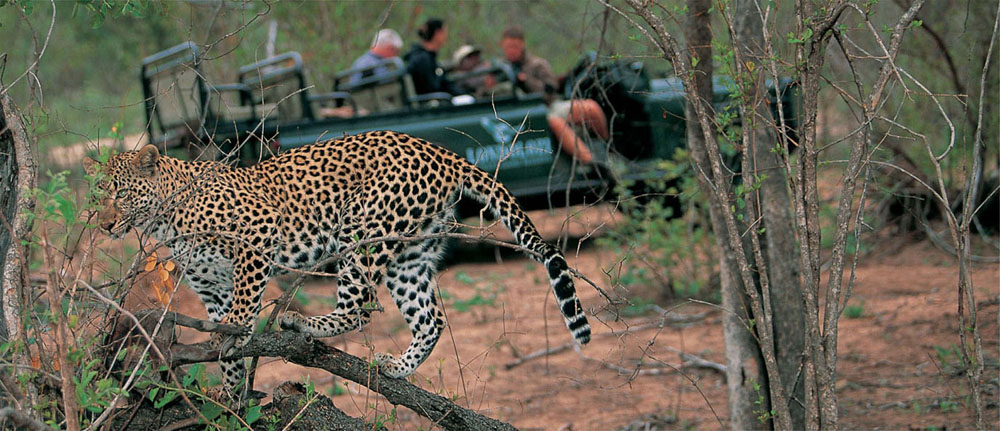

Of all places, Africa holds the greatest promise for extraordinary encounters with wild cats, but only where decades of protection have enabled them to overcome their natural inclination to avoid people and their activity. The perpetuation of large protected areas and the tourism they support is a crucial factor in the conservation of African cats.

The ‘Large Carnivore Problem’ has a simple answer: give carnivores space. Any meaningful effort to conserve felids must begin with setting aside large expanses of wilderness. Fortunately, Africa boasts a superb network of parks and reserves, with some of the oldest, largest and most biologically diverse protected areas on the planet. Provided that African governments continue to safeguard vast, essentially undisturbed ecosystems, African cats will persist in the wild. But can parks survive? Agriculture, livestock and high densities of people now demarcate a ‘hard edge’ to many African protected areas, and the human pressure to access the natural resources they protect is intense. That pressure will grow as Africa’s population continues to bloom. It may seem inconceivable that the Masai Mara, Serengeti or Kruger National Park could be engulfed by cattle or crops, but to impoverished people living on their boundaries, parks are increasingly viewed as a means of survival.

Many conservationists believe that local communities can benefit from protected areas without having to consume them. Their argument is reasonable; if wildlife generates revenue for local people, they will preserve it. Indeed, virtually every national park, reserve and sanctuary on the continent is populated by people who derive their living from the parks as scientists, guides, drivers, lodge staff, game guards and so on. Many more people support themselves on the periphery of parks or in adjacent towns by selling goods and services to the tourist traffic passing through. The complex economies associated with parks are the reason that many of them persist in Africa today. Reducing wildlife to a dollar-value offends many purists, but it may be an extravagance to think that it will be saved other wise. I believe passionately that we should protect big cats because of their intrinsic value. But I am not a poor subsistence farmer living adjacent to a resource-rich wilderness whose sole contribution to my life is regular raids from cattle-killing predators or crop-raiding herbivores.

The end of the hunt. Though considered inhumane by many observers, the revenue generated from trophy hunting ensures the preservation of significant tracts of wilderness in Africa.

Even if wildlife-seeking visitors continue coming to Africa in sufficient numbers, can we assume that protected areas are safe? In many East and southern African countries where open woodland savannas and high wildlife densities furnish spectacular experiences, tourism ranks among their most valuable industries. Yet by 2050, many of those countries will have populations at least twice as large as today. Rwanda and Zambia’s populations are predicted to double, Kenya’s will grow from 34 million to 83 million and Uganda, with its recovering wildlife populations and growing tourism industry, will explode from 28 million to a staggering 127 million. In some of these countries, it’s hard to imagine that the intense demands of such enlarged populations can be addressed by parks and their associated economies. For countries already with more people and less wildlife, the prospect for tourism as a mechanism to protect wildlife is grim. By 2050, Ethiopia’s fine system of protected areas will need to justify its existence to a population of 170 million people (from 77 million in 2005).

Even in the worst scenario, some protected areas will survive and, provided they are large enough, so too will cats and other large carnivores. Indeed, some African states – Gabon, Mozambique and South Africa, for example – are continuing to protect more land today even as their human populations grow. However, even with these successes, we can no longer afford to assume that setting aside reserves is sufficient. Apart from the growing threats to their survival, many reserves are already too small or too isolated to protect viable populations of cats. Even large, very well protected populations are not invulnerable, exemplified by the distemper outbreak in Serengeti lions (Chapter 4). To tackle the conservation of Africa’s cats successfully, conservationists are increasingly shifting their focus to the areas where they are most imperiled today – outside the parks.

Protecting the unprotected: cats, people and coexistence

Typified by the adaptable leopard, the resilience of the cat family will confront its greatest test in the coming decades. Without concerted conservation efforts, the outlook for cats in many parts of Africa is bleak.

Many African countries still have huge areas where cats live outside the protective custody of national parks and reserves. These areas have the potential to sustain large numbers of cats well into the future. However, in most cases, they are also home to many people, and cats in unprotected areas are already subject to greater pressure than protected populations. As discussed earlier, the greatest threat to cats in unprotected areas is Human-Wildlife Conflict, and the key to conserving these cats is finding ways to ease it.

Sometimes, the solutions are simple. There is now a wealth of evidence demonstrating that pastoralists with few predator problems adopt some basic precautions compared to their beleaguered neighbours. Not surprisingly, good husbandry translates into fewer losses; the most successful herders corral their stock at night, accompany herds as they graze during the day, and post dogs at night to warn of approaching predators. Slightly more sophisticated approaches include limiting the birth periods for stock to the dry season when vegetation is less dense, and using electrified fencing to deter predators from nocturnal raids on bomas.

The emerging use of large, aggressive breeds of European livestock-guarding dogs holds promise; bonded to the herds as puppies, they confront predators rather than attempt to herd their livestock to safety when danger appears (which often incites an attack from a hunting cat). Anatolian shepherd dogs in Namibia successfully deter attacks from caracals, cheetahs and occasionally more formidable foes – there is a recent record from Namibia in which an Akbash dog defending its herd killed a leopard. Above all else, the communities that tolerate wild herbivores on their land boast dramatically fewer losses than areas where there is little natural prey for cats. Of course, cats will seize an opportunity to make an easy kill of domestic stock, but in places where natural alternatives are still abundant, and especially when herders and their dogs stay with the herds, they largely don’t.

As intuitive, uncomplicated and beneficial as these solutions are, they require effort to accomplish. Most also require an additional investment which, even though none is costly, some communities cannot afford or are simply unwilling to make. To many pastoralists, the cheapest alternative also requires the least effort; why go to the trouble of keeping dogs or spending long, arduous hours in the bush watching cattle when poison will do the job? It is a fact that, unless people want to protect cats, a great many more will be killed wherever there are people and their livestock.

Which brings us full circle, back to commerce. In some areas and for some communities, providing a financial incentive to tolerate cats may be the only way to conserve them. Numerous efforts have been made to compensate farmers for their loss; by paying for livestock killed, the hope is that herders are less likely to kill cats. But compensation programmes almost invariably fail. Claims of depredation are difficult and costly to verify, cats are often erroneously or intentionally blamed for losses to other factors and falsification of claims inevitably creeps into the system. Surprisingly perhaps, being paid to tolerate losses may even remove the incentive to avoid them; the rewards for losing stock can sometimes be more profitable than caring for it. Rather than compensation, positive incentives or insurance schemes may provide an answer. Perhaps paying communities for the number of lions on their land will work more effectively to build tolerance than reimbursements for any cattle the lions kill. Similarly, if livestock were insured against losses to cats, sensible herders would adopt better techniques to reduce their losses. Just as with drivers whose vehicle insurance rates reflect their ability to avoid damage, farmers practicising sound husbandry would enjoy fewer losses and lower premiums. In principle, these novel ideas hold considerable promise, though none has yet been prosecuted anywhere in Africa with meaningful results for cats.

Reintroducing cats

Reintroducing cats into areas they formerly inhabited – usually by capturing wild cats from locally abundant populations and translocating them to a new site – has yielded some notable successes in southern Africa. In some areas where farming is proving marginal, landowners and governments alike are attempting to tap the demand for wildlife tourism (including trophy hunting) by replacing cattle with large cats and their prey. Provided a few basic needs are met, cats are surprisingly amenable to reintroduction, and populations enjoy high survivorship, successful reproduction and rapid re-establishment. In South Africa alone, wild lions have been reintroduced into at least 21 privately and publicly-owned reserves covering a combined land area of over 4 500 square kilometres. Even so, the long-term conservation value of reintroduction as a conservation strategy remains equivocal. All the South African reintroduction sites are small and most are isolated from other populations. With few prospects for natural dispersal and immigration, reintroduced cats require intensive management that includes translocations, contraception, sterilisation and, in some cases, hunting. Furthermore, reintroduction is costly and requires very specialised expertise. The South African projects have provided critical insight into ensuring that reintroduction works when it is required, but the priority for long-term protection of cats rests in conserving them where they still exist.

For considerable parts of Africa, the only realistic solution is ‘consumptive utilisation’ – hunting. As difficult as it is for me to accept that hunting a lion or a leopard can be considered sport, there is no doubt that hunting makes a substantial contribution to protecting African wilderness. Areas given over to trophy hunting comprise huge areas of many African states, and the revenue generated by the industry ensures those areas are not converted to agriculture or cattle farms. Further, sport hunters often value places and experiences that ‘normal’ tourists on the safari route will not tolerate. The dense, malariaridden scrub that dominates much of the Ruaha-Rungwa ecosystem in southern Tanzania is of no interest to most wildlife-watchers, but it is prized by hunters for its ruggedness, remoteness and isolation. Similarly, whereas Zimbabwe’s current social and political turmoil has led to a virtual collapse in wildlife tourism, the hunting industry is little affected.

Hunting may also be a mechanism to protect cats in conflict with livestock. Ranchers in some southern and East African countries earn a portion of the hunter’s fee when a cat is shot on their land. In principle, the financial benefit from the shooting of an occasional big cat encourages a farmer to leave the rest of the population alone because they want to be able to hunt in the future. The same rationale underlies projects such as Zimbabwe’s CAMPFIRE project (Communal Areas Management Programme For Indigenous Resources) which empowers rural communities to manage their wildlife resources and derive economic benefits from trophy hunting (and, less so, from tourism).

In practice, none of these novel schemes is a panacea to the challenges of conserving cats. CAMPFIRE has succeeded where profits are distributed to all members of the community, as intended; where local corruption thwarts sharing, it has plainly and drastically failed. Similarly, the Namibian farmers whose land represents habitat for over 90 per cent of the country’s cheetahs probably benefit too infrequently from trophy hunting to stop shooting cheetahs themselves. Even if those obstacles are overcome, the trophy hunting industry itself is rife with problems. The incentives for hunting operators are so large – hunters are willing to pay US$25 000 to $30 000 to shoot a lion or leopard – that corruption is widespread. Over-shooting quotas and hunting young animals and females are persistent problems that, to date, much of the industry seems unwilling to self-regulate. Awarding long-term concessions – 15–25 years – to operators, such that they treat the land as their own to manage sustainably, averts many of the worst practices, but African governments increasingly favour shorter concessions to increase competition over them. To a concessionaire granted only a few years, shooting as much as possible maximises profits in a limited time, regardless of its rampant unsustainability.

Realistically then, do the cats of Africa have a future? I do not believe that any of Africa’s felids will disappear from the wild in the next 50 years. However, with the possible exception of the sand cat, all of them will lose more range, decline further in number and surrender some populations – the smaller ones, those already surrounded by people and perhaps those in the most productive regions – to human encroachment. At some point, these losses will reach a threshold at which a species can no longer sustain itself. Science is unable to predict when that point will arrive for any African cat across its range, but it is now inevitable for leopards in North Africa, probable for cheetahs in Egypt and may already be too late for lions across West Africa.

Cats display astonishing resilience and manage to persist despite our best efforts to eradicate them. But in the Africa of 2050, most species (especially the ‘big three’) will survive only where people choose to tolerate them. Such areas will be those where we have succeeded on two fronts – reducing people’s conflict with cats and providing the means for people to derive benefit from them, whether by tourism, hunting or some other mechanism. As we have seen, no single approach will provide the complete solution. Indeed, conservationists will need to try – and triumph with – many approaches if we are to ensure that cats remain a part of Africa’s extraordinary fauna beyond the next 50 years. If we fail, the continent that has seen humans and cats coexist for the longest time will be a wretched place.