Infections, Inflammogens, and Drugs

Publisher Summary

This chapter examines environmental inflammatory factors in vascular disease and dementia with a focus on infections, environmental inflammogens, and drugs that modulate both vascular disease and dementia. Infections and blood levels of inflammatory proteins are risk factors for future coronary events and possibly for dementia. When early age mortality is high, the survivors carry long-term infections that impair growth and accelerate mortality at later ages (“cohort morbidity phenotype”). Chronic infections, which are endured by most of the world’s human and animal populations, cause energy reallocation for host defense. Infections and inflammation may impair stem cell generation, with consequences to arterial and brain aging. Diet may introduce glycotoxins that stimulate inflammation. Some anti-inflammatory and anti-coagulant drugs may protect against coronary artery disease and certain cancers, and possibly also for Alzheimer disease. These “pharmacopleiotropies” implicate shared mechanisms in diverse diseases of aging.

2.1 INTRODUCTION

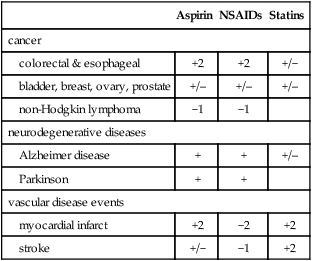

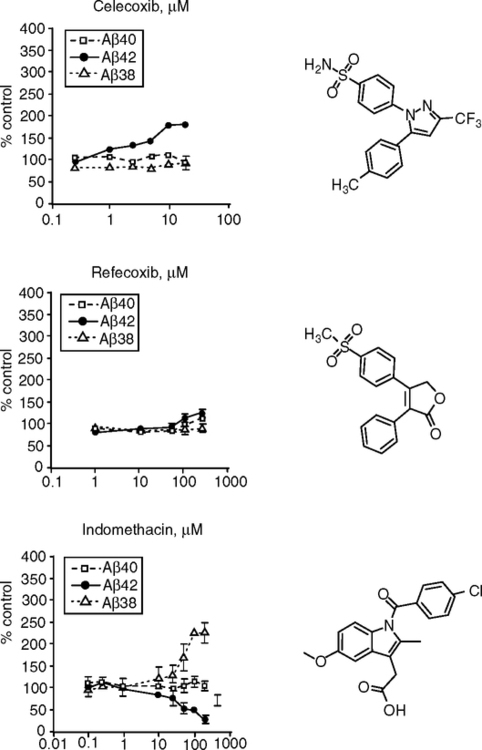

Chapter 1 emphasized the role of inflammatory processes in vascular disease, from early beginnings before birth. Alzheimer disease shares many of the same inflammatory changes, although cause and effect are less clear. This chapter follows the pathways of Fig. 1.2 further by examining the role of infections and inflammatory agents in vascular disease and Alzheimer disease and selected cancers. Pharmacologic interventions through NSAIDs and anti-coagulant drugs further establish the inflammatory mechanisms in vascular disease and may extend to Alzheimer disease. These examples are discussed in relation to Query II (Section 1.1) that inflammation causes bystander damage and Query III that environmental pathogens and inflammogens influence chronic diseases with inflammatory processes through bystander damage (Section 1.4).

The environmental role in these diverse, slowly developing diseases remains counter-current to traditional thinking, because in general, Alzheimer disease, cancer, and vascular disease are not ‘infectious,’ by Koch’s postulates. That is, with few exceptions for these diseases, infectious agents cannot be isolated, and the disease cannot be transferred and propagated to a test animal.

2.2 VASCULAR DISEASE

2.2.1 Historical Associations of Infections and Vascular Mortality

The traditional risk factors for vascular disease (hypertension, obesity, elevated LDL cholesterol, smoking) do not explain about 35% of cases (Section 1.5.3.2). From epidemiologic and pathologic studies, chronic infections may be primary causes or co-factors of inflammation in vascular disease. This controversial concept has been discussed for a century or more (Frothingham, 1911). The hypothesis of inflammation as a co-factor is strongest in human arterial disease, because prodromal microscopic foci of oxidized lipids and activated macrophages are present before birth (Section 1.5.3.1). The evidence for the role of infections in arterial disease, while considerable and supported by animal models, is still largely circumstantial for humans.

Rheumatic heart disease is a classic example of infection-caused heart disease, but with a different etiology than most cardiovascular cases. Until about 1950, rheumatic fever from ‘strep’ infections was still an important cause of damage to heart valves. In particular, streptococcal A substrains cause high incidence of endocarditis and mitral valve scarring (Bispo, 2000; Stollerman, 1997; Wilson, 1940). Rheumatic fever with mitral damage is life-shortening (Jones, 1956). In the 1930s, for example, few survivors of childhood infections lived to age 40, and most died within 15 years of infection (Wilson, 1940, p. 272). Rheumatic heart disease has become rarer in developed countries from public health improvements and, then after 1950, the availability of antibiotics. However, heart valves without rheumatic disease often harbor a diverse bacterial flora (see below).

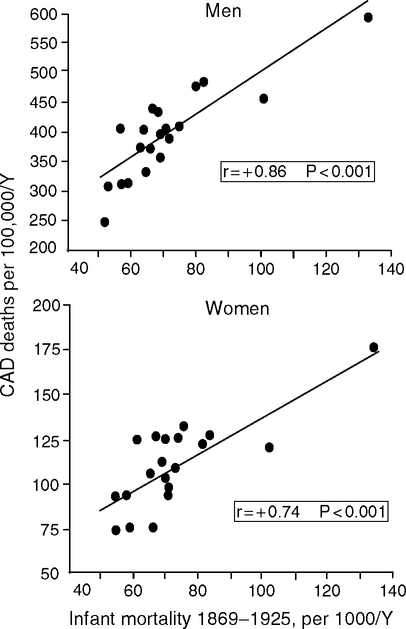

Eileen Crimmins and I hypothesize that historical and modern levels of early infection are major determinants of adult vascular disease (Crimmins and Finch, 2006a,b; Finch and Crimmins, 2004, 2005). More generally, historical and modern populations also show associations of infections with later mortality. In some rural parishes of 17th century Sweden, high early infectious mortality was followed by high late life mortality among survivors (Bengtsson and Lindstrom, 2000; Bengtsson and Lindstrom, 2003). Among U.S. Civil War veterans, infectious disease in early adulthood has been associated with heart and respiratory problems after age 50 (Costa, 2000). Cardiovascular disease was twice as prevalent among older Army veterans born before 1845 compared to veterans born in the early 20th century (Fogel and Costa 1997; Fogel, 2004). In Norway 1896–1925, infant mortality, which is a proxy for exposure to infections, correlated strongly with arteriosclerotic deaths 40–69 years later (Forsdahl, 1977) (Fig. 2.1).

In the United States 1961–1971, adult cardiovascular disease is also associated with birth cohort levels of infant diarrhea and enteritis (Buck and Simpson, 1982). Other examples are discussed in Crimmins and Finch (2006a). Considered over most of the 20th century, the associations of prior infections on later mortality may explain up to nearly 25% of the decline of both morbid and mortal conditions at later ages (Costa, 2000). Relationships of early and later age mortality in birth cohorts are developed further below.

2.2.2 Modern Serologic Associations

Stepping forward, we have access to individual histories of infections through persistent antibodies. Serologic associations with cardiovascular disease were first noted in 1987 for cytomegalovirus (CMV) (Adam et al, 1987), soon followed by Chlamydia1 pneumoniae in 1988 (Saikku et al, 1988). Other associations include the ubiquitous Helicobacter pylori and Mycoplasma pneumoniae; and cytomegalovirus (CMV), hepatitis virus A and -C viruses (HAV, HCV), and herpes simplex virus (HSV-1 and -2) (Belland et al, 2004; Campbell and Kou, 2004; Stassen et al, 2006; Vassalle et al, 2004). Cerebrovascular disease is also associated with C. pneumoniae and H. pylori (CagA strains) (Lindsberg and Grau, 2003). Carotid thickness correlates with antibodies to E. coli endotoxin (LPS) (Xu, 2000), while anti-LPS antibodies correlate with antibodies to oxidized LDL (Mayr et al, 2006). The list grows.

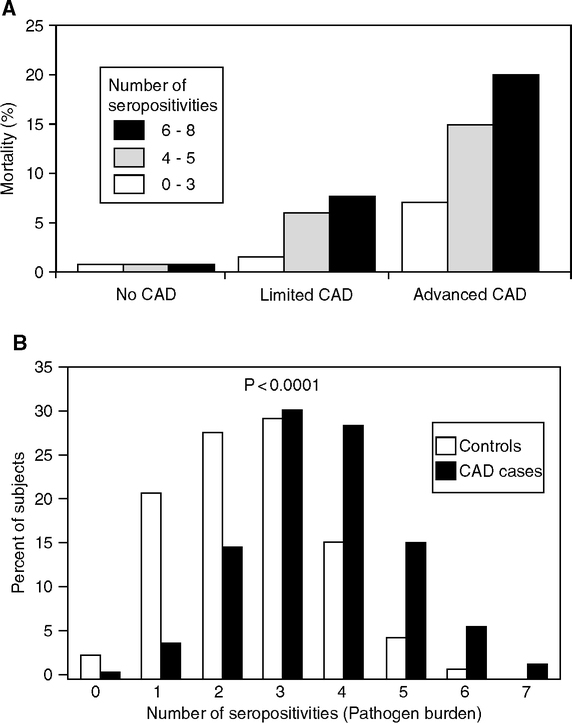

In the AtheroGene Study (Mainz and Paris), cardiovascular mortality and coronary stenosis were 2–3-fold higher in patients seropositive for ≥ 4 pathogens, relative to those with 0 to 3 seropositivities, with the highest odds ratios for C. pneumoniae and M. pneumoniae (Espinola-Klein et al, 2002a, b; Georges, 2003) (Fig. 2.2A, B). Carotid and femoral artery thickening (IMT) are greater in individuals with chronic infections who also carry proinflammatory alleles of IL-6, IL-1 receptors, and the endotoxin receptor CD-14 (Bruneck Study, northern Italy) (Markus et al, 2006). Blood levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), an inflammatory protein and strong risk indicator of coronary artery disease (Section 1.5, Fig. 1.16B), may also correlate with the number of different seropositivities (Georges et al, 2003; Zhu et al, 2000) (Fig. 2.2C). However, others did not find these serological associations with CRP elevations (Epstein et al, 2000; Lindsberg and Grau, 2003). This is not surprising, because seropositivity often persists long after an infection has subsided and transient elevations of CRP have subsided. Over the life span, the majority of adults become seropositive for C. pneumoniae and CMV (Almanzar et al, 2005; Miyashita et al, 2002).

Epidemiological associations of infections and vascular disease are increasingly supported by clinical studies and animal models (Campbell and Kuo, 2003; Coughlin and Camerer, 2003; Libby, 2003; Liuba et al, 2003). C. pneumoniae illustrates several key issues. This gram-negative bacterial pathogen grows only as an intracellular parasite. Infections typically begin in lungs and may propagate systemically to the vasculature by circulating macrophages. Infections are ubiquitous and reinfections very common (Belland et al, 2004; Campbell and Kuo, 2004; Grayston, 2000). C. pneumoniae is notorious for its broad cell targets, including endothelia, macrophages, and smooth muscle cells of atheromas. It resists antibiotics, which can suppress normal replication without eradicating its effects. Dead C. pneumoniae still activate the transcription factor NF-kB in endothelial cells, which could promote atherogenesis without active infection (Baer et al, 2003). C. pneumoniae are detected in the majority of atheromas by immunological, genomic, or ultrastructural criteria, but not in healthy arteries (Muhlestein et al, 1996; Shor et al, 1998; Shor, 2001). Heart valves tend to have more C. pneumoniae and other pathogens, in diseased than normal hearts (Juvonen et al, 1998; Nilsson et al, 2005; Nystrom-Rosander et al, 2003). Live C. pneumoniae was cultured from vascular tissues from some cardiac patients (Belland et al, 2004; Campbell and Kuo, 2004). T cells cultured from atherosclerotic carotids were immunopositive in 40% of 17 patients (Mosorin, 2000). These individual variations may arise from successful elimination of the pathogen by the host. The suppression of pathogen growth by antibiotics or cell stress may also add to these variations (Belland et al, 2004; Campbell and Kuo, 2004). However, assay criteria for C. pneumoniae are not well standardized and detectability varies from 0–100% (Kalayoglu et al, 2002; Peeling et al, 2000). The high genetic diversity of C. pneumoniae (Belland et al, 2004) may also contribute to variability. Some argue that C. pneumoniae and H. pylori in vascular lesions are an epiphenomenon because damaged or necrotic tissues, such as found in vascular plaques, are vulnerable to superinfections (Black, 2003). It is hard to prove the causal role of infections in atherogenesis because of their earthly ubiquity— everyone experiences infections (Belland et al, 2004; Campbell and Kou, 2004).

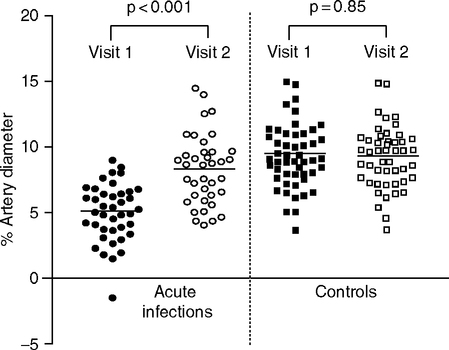

Peripheral arteries also show effects of infections. Children with acute respiratory infections had impaired regulation of the brachial artery endothelium, by the flow-mediated vasodilation test (Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, or ALSPAC Study, Fig. 2.3). The effects of infection may have persisted for a year in some individuals (the statistical significance was P<0.06) (Charakida et al, 2005). Longitudinal follow-up continues. Studies of children are valuable because seropositivities are less frequent than in adults.

Antibiotics give another test of the infection hypothesis. The large WIZARD trial [weekly intervention with zithromax (azithromycin) for atherosclerosis and its related disorders] is so far inconclusive (Dunne, 2000). Experimental design is difficult, because the treatments may be most effective early during infections (de Kruif et al, 2005). Other long-term studies include the Azithromycin and Coronary Events (ACES) (Belland et al, 2004) and the Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy (PROVE-IT) (Campbell and Kuo, 2004). The first placebocontrolled, double-blind, randomized clinical trial of antibiotics on C. pneumoniae in vascular tissue was inconclusive (Berg et al, 2005). Although 81% of cardiac bypass patients were seropositive, C. pneumoniae DNA was not present in plaques of patients with advanced CAD; antibiotic treatment did not alter seropositivity.

Animal models show that infections may have greater synergy with arterial disease when lipids are elevated, as is common during infections (Section 1.4). In rodents, rabbits, and pigs, C. pneumoniae accelerated atherogenesis, but only when the models were made hyperlipidemic (Belland et al, 2004, de Kruif et al, 2005; Liuba et al, 2003a,b,c). Chronic endotoxin also required hyperlipidemia to accelerate atherogenesis (Engelmann et al, 2006). The apoE-knockout (–/–) mouse is an important model, with greatly elevated cholesterol on non-atherogenic diets that promote progressive arterial lesions not found in normal mice. ApoE knockouts develop aortic plaques by 4 months, followed by vascular rigidity and aneurysms (Wang, 2005, Wouters et al, 2005). Moreover, the lipidemia-induced lesions depend on pathogen-signaling pathways via Toll-like receptors (TLRs) linked to MyD88, an adaptor that activates kinases (Laberge et al, 2005) (Chapter 5, Fig. 5.4). The double apoE and MyD88 knockout mouse had much small aortic lesions, with fewer macrophages and lower chemokines In apoE knockouts, C. pneumoniae caused rapid vascular endothelial damage (aortic contractility, 2–6 weeks after infection) (Liuba et al, 2000). Subsequently, the arterial wall thickens with increased ROS production. The convergence of hyperlipidemia in infection and arterial disease through pathogen-activated pathways suggests that atherogenesis is bystander outcome of the indispensable host defense mechanisms.

Future case control studies with longitudinal follow-up may be more conclusive. We may learn how to quantify effects of infections on vascular damage by the intensity and duration. There could be a threshold for acute infections of sufficient brevity that do not cause enduring damage. We may anticipate some dose-duration relationships in chronic subclinical infections and arterial disease that are like the ‘pack-years of smoking’ in relation to carotid thickening, as discussed below (Fig. 2.6) and lung cancer. The pathogen burden is indicated by the scaling of vascular event risk to the number of seropositivities, discussed above (Espinola-Klein, 2002; Georges et al, 2003; Zhu et al, 2000). Both research groups use similar terminology, ‘pathologic burden’ (Zhu et al, 2000) and ‘infectious burden’ (Espinola-Klein, 2002), to represent seropositivities, which does not inform on whether infections are active. I suggest the alternative term inflammatory burden to more comprehensively represent these long-term inflammatory influences. Besides infections, the inflammatory burden includes non-infectious inflammogens such as smoke and other aerosols and dietary AGEs produced during cooking (see below). These complexities are well expressed by Stephen Epstein and colleagues:

Given that atherosclerosis is a multifactorial disease, Koch’s postulates to establish causality will never be satisfied. These postulates … assume a single pathogen, require that all patients with the disease must have evidence of being infected with the casual agent and that all the infected develop the disease. In contrast … infectious agents are … neither necessary nor sufficient for [vascular] disease development … proof of causality can be achieved only in terms of probability rather than as certainty. (Epstein et al, 1999, p. e26).

2.3 INFECTIONS FROM THE CENTRAL TUBE: METCHNIKOFF REVISITED

A century ago, Metchnikoff suggested that autointoxication by microbial toxins in the intestinal flora causes chronic poisoning of body cells and premature death (Metchnikoff, 1901, Podolsky, 1998). Recent evidence implicates bacterial leakage from periodontal disease in vascular disease. Moreover, I suggest the lower gut should also be considered in bacterial leakage, which could be a factor in elevated circulating acute phase proteins during aging.

2.3.1 Humans: Leakage from Periodontal Disease and Possibly the Lower Intestine

The mouth normally harbors several hundred bacterial species, mostly as very high density biofilms on teeth. About 10 species of gram-negative anaerobes may be the main pathogens in vascular disease, particularly Porphyromonas gingivalis and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans (Asikainen and Alaluusua, 1993). Their subgingival location is less accessible to antibiotics. We are unavoidably exposed to this high-density flora: Even tooth brushing and flossing can cause transient bacteremia (Carroll and Sebor, 1980, Slots, 2003).

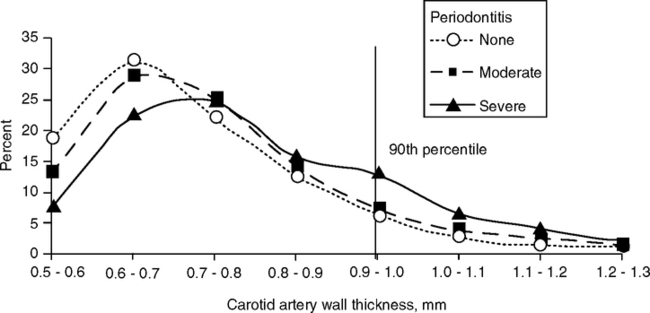

The evidence for oral-vascular disease relationships is controversial. In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (ARIC Study), severe periodontal disease was associated with thick carotid walls (Fig. 2.4); the effect was greater in men than women (Odds ratio, OR 1.46, range 1.18–1.81) (Beck et al, 2001, 2005; Beck and Offenbacher, 2001). In ARIC (Slade et al, 2003) and other studies, serum CRP, fibrinogen, and IL-6 tended to be elevated in individuals with periodontitis who were otherwise healthy (Chun et al, 2005; D’Aiuto et al, 2004; Schwahn et al, 2004). In atheromas from vascular surgery, nearly half contained DNA from at least one periodontal pathogen (Haraszthy et al, 2000).

The periodontitis-vascular association is experimentally supported. In rabbits, periodontitis induced by P. gingivalis increased aortic lipid deposits in proportion to the severity of periodontitis (Jain et al, 2003). P. gingivalis generally forms biofilms beneath the gingiva and can invade oral epithelia and vascular endothelial cells. Activation of Toll receptors by P. gingivalis is associated with increased IL-1, TNFa, prostaglandin E2, and leukocyte adhesion molecules (ICAM-1, VCAM-1) (Choi et al, 2005a; Chun et al, 2005; Hajishengallis et al, 2004).

The associations with vascular disease are considered circumstantial (see the analysis of 14 studies) (Kolltveit and Eriksen, 2001), because few studies measured infections by serology or bioassay (Danesh et al, 1999); smoking adds other confounds (Hujoel et al, 2000). In ARIC, 68% were seropositive for one or more of 17 bacterial species associated with periodontal disease (Beck et al, 2005). High antibody titers to >1 oral pathogen were associated with higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease, particularly in never-smokers. However, there were no associations of periodontal disease with prevalent cardiovascular disease after adjusting for covariates. Prospective studies should include the individual histories of oral health, smoking, and other lifestyle covariates; multiple time samples of serology for the spectrum of major pathogens; and screening for genetic polymorphisms in IL-1a and IL-1β, which are associated with risk of periodontal disease (Lopez et al, 2005).

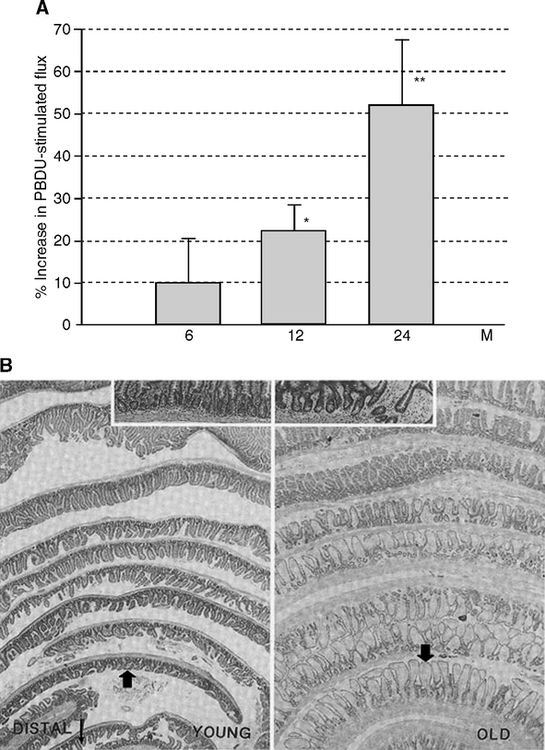

Diverse microbial ‘communities’ reside in the mouth and lower intestine. The intermediate gut is normally quite sterile, stomach through jejunum (Lin, 2004). The gut epithelial cells in the crypts of Lieberkuhn have tight junctions (zona occludens) that maintain characteristic epithelial cell polarity as part of the barrier to the body cavity and prevent leakage of gut contents (Mullin et al, 2005). Cholera and other pathogenic bacteria alter this vital tight junction barrier. In aging rats, tight junctions become leakier, as assayed by transcolonic epithelial permeability; these aging effects were greater on high fat diets (Mullin et al, 2002) (Fig. 2.5A). The aging gut may have increased leakage, allowing entry of endotoxins into the circulation. As a precedent, CRP elevations are common in inflammatory bowel disease (Poullis et al, 2002). At some threshold, leakage of endotoxins could cause elevations of blood CRP and other acute phase proteins (Section 1.7).

The increase of colonic permeability with aging may be due to aberrant crypts (Mullin et al, 2002). Aberrant crypts and villi with cellular dysplasia and loss of epithelial cell polarity increase during aging in the gut of rodents (Mullin et al, 2002) (Fig. 2.5B) and humans (Finch and Kirkwood, 2000, pp. 132–137; Shpitz et al, 1998; Takayama et al, 1998). Stem cell depletion may contribute to these aging changes. Epithelial cells in the crypts of Lieberkuhn proliferate throughout life and are extruded at the tips of the intestinal villi. The crypt stem cells (Potten et al, 2001; Potten et al, 2003) apparently become stochastically depleted during aging (Finch and Kirkwood, 2000, pp. 132–137; Martin, 1998). Radiation and some carcinogens accelerate the loss of stem cells and increase the incidence of abnormal crypts (Magnuson et al, 2000; Martin, 1998). Alternately, TNFa can alter tight-junction permeability via NF-kB activation, as implicated in Crohn’s disease and other chronic intestinal inflammations. Mucosal layer breakdown is not necessary for inflammatory transients to cause gut leakage of potential significance to arterial disease (Lin, 2004).

Obesity and diabetes predispose to chronic low-grade infections, which are discussed with effects of diet restriction in Section 3.2.4. The burden of infections (HSV-1 and -2, enteroviruses) shows correlations with insulin resistance particularly in those with C. pneumoniae seropositivity. Thus, metabolic adaptive responses to low-grade infections could be atherogenic by altering insulin sensitivity (Fernandez-Real, 2006). Moreover, the sensitivity to low-grade infections may be associated with inflammatory gene variants.

2.3.2 Worms and Flies as Models for Human Intestinal Microbial Intrusion

In the worm model of aging, bacterial autotoxicity may be a proximal cause of death during aging (Garigan et al, 2002; Gems and Riddle, 2000; Lithgow, 2003; Mallo et al, 2002) (also discussed in Section 5.2). Wads of bacteria pack the pharynx in aging worms and there is bacterial overgrowth in the pharynx and intestine (Garigan et al, 2002) (Fig. 2.5C)—“… the final coup de grace is bacterial invasion” (Lithgow, 2003, p. 16). The constipation of aging worms may model aspects of human inflammatory bowel syndrome, in which bacterial overgrowth into the normally sterile small intestine causes chronic inflammation (Lin, 2004; Pimentel et al, 2000). Several long-lived worm mutant resist pathogenic bacteria (Garsin et al, 2003) (Section 5.5.2).

In the standard culture conditions, worms are fed on live E. coli strain OP50 (Brenner, 1974). However E. coli OP50 may not be the optimum food because life spans may be longer and constipation lessened on diets of some species of yeast (Mylonakis et al, 2002a) or diets of the soil bacterium Bacillus subtilis, which may be more natural foods (Garsin et al, 2003). The concern that live E. coli OP50 is mildly pathogenic is now 40 years old (Croll and Yarwood, 1977; De Cuyper and Vanfleteren, 1982; Hansen et al, 1964): “The longer life span in the absence of bacteria suggests a possible toxicity of bacterial products in the monoxenic cultures” (Hansen and Yarwood, 1964, p. 629).

Elimination of live bacteria from the diet increases life spans. A diet of UV-killed bacteria delayed the pharyngeal pack-up of bacteria (Garigan et al, 2002) and increased life spans up to 55%, without loss of fecundity (Gems and Riddle, 2000). Moreover, axenic growth on sterile media supplemented with nutrients doubled the life span (Croll et al, 1977; De Cuyper and Vanfleteren, 1982; Houthoofd et al, 2002; Houthoofd et al, 2004). The axenic cultures maintained the rate of pharyngeal pumping to later ages and increased stress resistance, but at the expense of lower fecundity (Croll et al, 1977; Houthoofd et al, 2002). Switching from axenic to bacterial media after larval maturation eliminated the longevity benefit; conversely, raising larvae on bacteria followed by brief antibiotic treatment before transfer to axenic media increased longevity almost as much as growth on sterile media throughout life (De Cuyper and Vanfleteren, 1982). However, these benefits are due not only to the elimination of bacterial toxicity, because this axenic medium was deficient in ubiquinone, a micronutrient obtained from the bacterial diet (Jonassen et al, 2003; Larsen et al, 2002).

These findings raise uncomfortable questions about artifacts from standard lab conditions that are widespread in lab models. I argue that all of our experimental models adapted to the lab should be scrutinized for atypical outcomes of aging. Lab husbandry has eliminated most infections and provides a uniform quality ad lib diet rarely found over the life span in nature. Moreover, our highly inbred lab models were initially selected for early reproduction and high fecundity that may be atypical of the evolutionary background. These concerns will be discussed further in the next chapter in interpreting the obesity common in lab rodents.

Flies also show the importance of enteric microbes to aging. In Drosophila melanogaster antibiotics given later in life increased life span by 30% (Brummel et al, 2004). Cell changes in the aging fly gut are consistent with the leakage of gut bacteria later in life. Aging intestinal epithelial cells accumulate virus-like particles (Anton-Erxleben et al, 1983). In the aging housefly (Musca domestica), intestinal cells accumulate concretions (Sohal et al, 1977) and lipid inclusions (Sohal, 1981). Bacteria are seen in sick-looking flies (the insect body cavity is usually sterile) (Flyg et al, 1988). Recent data document the increased bacterial and fungal load of aging flies (Section 5.6.4). The extensive increase of antimicrobial genes during aging in flies (Section 1.8) is consistent with the increased pathogen load of aging flies, possibly from breakdown of the barriers from the gut and exoskeleton. Chapter 5 discusses these and other genetic influences on longevity through inflammation and stress resistance.

2.4 AEROSOLS AND DIETARY INFLAMMOGENS

Chronic inflammation is stimulated by intake of non-infectious inflammogens by inhalation and ingestion. These sources have received less attention than infectious pathogens in relation to arterial disease. Airborne inflammogens may be of looming importance to future life expectancy with the accelerating global increases of air particulates (Section 6.4).

2.4.1 Aerosols

Aerosols are characterized by size (PM10, <10 μ particle diameter) and composition (mineral, hydrocarbon, sulfur, endotoxin, etc.) and whether the aerosols carry infectious agents (viable vs. non-viable aerosols). Inflammatory responses independently of infectious agents are induced by airborne inflammogens: Among many examples are smoke from tobacco, fossil fuel, and biomass combustion; dust from agriculture; and endotoxins from feces in the many urban locations with poor sanitation and in livestock and poultry. These sources are pertinent to current aging and to historical improvements in public health (Fig. 1.1A).

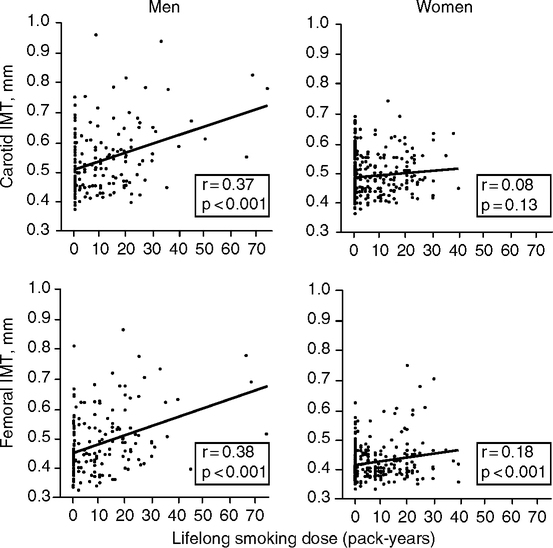

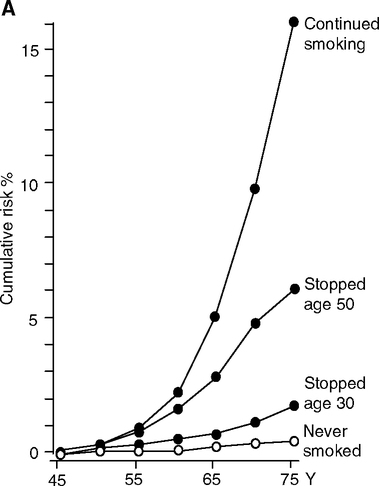

Smoke is well recognized as a non-infectious (‘non-viable’) aerosol with major consequences to vascular health. Cigarette smoke strongly increases the risk of heart attacks. In the United States in 1990, 20% of deaths from cardiovascular disease are attributable to smoking (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1993). Second-hand smoke is also strongly associated with coronary disease (Zhang and Smith, 2003; Zhu et al, 1997) and lung cancer (Section 2.4.2). Smoking increases the carotid wall thickness in men with dose-dependency (number of pack-years as an estimate of lifetime exposure) (Gariepy et al, 2000) (Fig. 2.6). The mechanisms include proatherogenic increases of oxidized LDL and acute phase proteins. In NHANES III, smokers were twice as likely than non-smokers to have very high CRP (>10 mg/L), with dose responses to the intensity and history of smoking (Bazzano et al, 2003). Second-hand smoke also increased serum CRP into the range of primary smokers and coronary risk in the ATTICA Study (Barnoya and Glantz, 2004; Panagiotakos et al, 2004). Men incur more adverse effects of smoking than women (Fig. 2.6) (Gariepy et al, 2000).

Other types of smoke cause chronic lung damage and inflammatory responses consistent with vascular diseases. Common sources of smoke are open combustion in fireplaces, furnaces, and factories, which diffuse into the breathing environment with adverse effects on the lungs (Singh and Davis, 2002). Until the mid-20th century, exposure to wood and coal smoke was almost unavoidable, and still is in many countries (Zhu et al, 1997). ‘Hut lung,’ or domestically acquired particulate lung disease, is associated with inhaled smoke particulates from burning coal, wood, or other fuels and wastes (Gold et al, 2000). Cardiovascular admissions to hospitals were associated with recent exposure to black smoke PM(10) in some studies, e.g., Edinburgh (Prescott et al, 1998).

Particulate air pollutants induce vascular endothelial damage (Sandhu et al, 2005; Schulz et al, 2005). Mortality gradients in vascular diseases followed indexes of ambient air pollution in residential zones; not surprisingly, higher income zones had the least exposure to pollution (Finkelstein et al, 2005). Animal models support this epidemiology. Particulate inhalants cause chronic lung damage with lung alveolar macrophage hyperplasia, fibrosis, and accelerated atherosclerosis, e.g., rats exposed to wood smoke (Tesfaigzi et al, 2002) or to fly ash (Schreider et al, 1985). In hypercholesterolemic Watanabe rabbits, exposure to particulate aerosol increased the size of coronary atheromas in proportion to the number of lung macrophages that had phagocytosed particles (Suwa et al, 2002).

Dust from corn and grain also induces inflammatory responses (Buchan et al, 2002; Jagielo et al, 1996). Even lab animal bedding materials can contain appreciable bacterial endotoxin and (1- >3)-β-D-glucan from bacteria, molds, and plants. When inhaled, these common aerobiosols induce chronic inflammation (Ewaldsson et al, 2002). Humans also experience varying exposures to bioaerosols according to occupation and income, which can be a factor in the strong socio-demographic gradients in longevity. Bioaerosols are now a major concern of industrial safety (Burrell, 1994; Menetrez et al, 2001), but are still a hazard of agricultural workers. Workers in sewage plants and garbage collectors also suffer from inhalants that cause chronic systemic inflammation and elevated CRP (Rylander, 1977). Farm workers entering a swine confinement building had rapid elevations of blood complement C3 peaking at 1 h, followed by peak CRP at 2 h (Hoffmann et al, 2003). The smokers in this group had greater responses. Besides airborne live bacteria and fungi, non-viable bioaerosols may contain endotoxins of fecal origin. A specific role of LPS inhalation was shown by the induction of plasma CRP and other inflammatory responses with well-defined dose responses (Michel et al, 1997; Thorn, 2001).

The aerosol-vascular disease association is relevant to the historical increase of human longevity during the developments of public sanitation (Section 2.5) and to earlier phases of human evolution as population density increased and encountered increasing exposure to infections, inflammogens, and especially to domestic smoke for cooking and heating (Section 6.2). Genetic risk factors for resistance to domestic smoke and other types of air pollution may have evolved during this time. Curiously, European populations have a high prevalence of a null allele (GSTM1*0) of glutathione-S-transferase M1. GST makes the key antioxidant glutathione (Fig. 1.11) and belongs to a superfamily of xenobiotic detoxifying enzymes with potential importance to human evolution (Section 6.4.2). The M1*0 homozygotes (equivalent to GSTM1 knockout) have impaired lung functions as children and a higher risk of asthma (Peden, 2005).

2.4.2 Food

Cooked foods have inflammogens produced by the chemistry of glyco-oxidation (Sandu et al, 2005). As discussed in Section 1.4.2, advanced glycation endproducts (AGE) and advanced lipid oxidation endproducts (ALEs) are produced endogenously from chemical reactions of glucose and other reducing sugars with peptide lysine and arginine, which are proinflammatory, atherogenic, and carcinogenic (Kikugawa, 2004; Skog et al, 1998; Vlassara et al, 2002). This saga began in 1912 with Louis Maillard’s discovery of chemical reactions between amino acids and glucose that lead to the loss of lysine and the formation of brownish condensation products (Finot, 2005; Maillard, 1912; Nursten, 2005). These reactions are the basis for browning of foods by broiling, or frying, which can increase AGE content 3- to 5-fold (Table 2.1) (Goldberg et al, 2004). AGEs and ALEs are also formed during food processing and storage. AGEs ingested from cooked foods are detected by immunoreactivity for the glycation adduct CML (N-carboxymethyl-lysine) (Table 2.1). In healthy adults, plasma CML strongly correlated with the dietary intake of AGE over a 3-fold range (Urribari et al, 2005).

TABLE 2.1

Advanced Glycation Endproduct (AGE) Content of Common Foods and Effects of Cooking

| Food | CML, kU/g food |

| beef, boiled 1 hr | 22 |

| broiled, 15 min | 60 |

| tofu, raw | 8 |

| broiled | 41 |

| milk (pasteurized) | 0.05 |

| butter | 265 |

CML (N-carboxymethyl-lysine, an AGE formed by heating); radioimmunoassay (Goldberg et al, 2004).

The proinflammatory effects of dietary AGEs were directly shown in diet cross-over studies of diabetics (Vlassara et al, 2002). Nutritionally equivalent diets were prepared by different degrees of heating that yielded 5-fold differences in CML. Six weeks on the high AGE diet elevated inflammatory markers, serum C-reactive protein by 35%, and TNFa by 85% in association with 30% higher CML. Similarly, ingested dietary AGEs correlated with serum CML in renal failure patients (Uribarri et al, 2003).

Rodents show adverse effects of dietary AGEs. In a mouse model of both atherosclerosis and diabetes (apoE–/– genotype, with STZ-induced diabetes), the high-AGE diet increased aortic lesions, whereas a low-AGE diet decreased lesions below the level in the standard chow diet (Lin et al, 2003). The lesions of the high-AGE diet group had more arterial foam cells and receptors for AGE (RAGE). In another mouse model, 6 months on a high-AGE/high-fat diet induced type-2 diabetes, with impaired glucose regulation and insulin insensitivity (Sandu et al, 2005). The low-AGE/high-fat controls had normal glucose regulation despite similar adiposity. Plasma 8-isoprostane, a marker of lipid oxidation, was increased by the high-AGE diet. As a further scary example, a caramel component used for coloring beverages (2-acetyl-4-tetrahydroxybutylimidazole, THI) inhibits lymphocyte egress from the thymus by inhibiting the sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor (Schwab et al, 2005). Dietary AGE content may have unrecognized influences on rodent studies, because lab chows are typically heated during preparation.2

These findings point to an expanding role of dietary AGEs in atherosclerosis and diabetes, and support their designation as glycotoxins’ (Koschinsky et al, 1997; Vlassara, 2005). Vlassara hypothesizes that dietary AGEs, possibly synergizing with tobacco and other environmental inflammogens, sustain oxidative stress and chronic inflammation. The AGE receptors (RAGEs) that activate signaling pathways with PI3K (Section 1.3.3) may link dietary glycotoxins to longevity pathways that involve insulin/IGF-1 signaling (Fig. 1.3A) and that are also implicated in vascular disease (Fig 1.3B).

Besides their color, some Maillard products have definitive tastes and aromas (Schieberle, 2005). Caramel coloring and flavorings have been added to commercial foods and beverages for more than a century (Chappel and Howell, 1992; Nursten, 2005). These preferences may have been important in the development of cooking during the last half million years when early humans learned to control fire (Section 6.2). Cooking could have enhanced health by killing parasites and infectious organisms in animal tissues. Moreover, cooking increases the usability of many plants as foods by increasing digestibility and by inactivating toxins that are widely found, e.g., cassava and potatoes. (De Bry, 1994) suggests that early humans used Maillard products as olfactory cues to indicate when tubers with heat-sensitive toxins were sufficiently cooked. Nonetheless, evolution of the omnivorous human diet would have greatly increased exposure to toxins, implying the importance of detoxification mechanisms to enable these new foraging strategies (Sections 3.7 and 6.2.3).

Future increases of human longevity may come from better knowledge of these interactions and the mechanisms that remove ingested and endogenously produced AGEs. Dietary changes during human evolution may also have selected for genes that detoxified dietary AGEs, e.g., the recently discovered amadoriases (‘AGE-breakers’) (Monnier and Sell, 2006). Our ancestors ate meat increasingly by a million or more years ago, a major departure from the plant-based diets of the great apes, and, it is presumed, that of the shared human-chimpanzee ancestor (Section 6.2) (Finch and Stanford, 2004). The more recent use of fire for broiling or roasting meat would have increased AGE ingestion and selected for meat-adaptive genes.

2.5 INFECTIONS, INFLAMMATION, AND LIFE SPAN

2.5.1 Historical Human Populations

The recent longevity increases (Fig. 1.1A) also implicate the relationship of infection and inflammation to arterial disease (Finch and Crimmins, 2004, 2005; Crimmins and Finch, 2006a,b). Anonymous reviewers of these papers questioned the importance of vascular disease in deaths before the modern era. However, all evidence points to vascular disease as ancient and ubiquitous “… its pattern has always been the same regardless of race, diet, and the stresses of survival” (Magee, 1998, p. 663). The 5,300 year old Tyrolean “iceman” of the Bronze Age evidenced carotid artery calcification (Murphy et al, 2003), which is common in advanced atherosclerosis (Fig. 1.13) (Section 1.5.3.1) and is an independent risk factor of vascular mortality (Doherty et al, 2003; Sangiorgi et al, 1998). Two millennia later, Egyptian mummies of the 18th dynasty preserved calcified arteries and other vascular pathology (Ruffer, 1911). Most large arteries (16/24) in this sample met criteria for atherosclerosis, with half of these specimens showing vascular calcification (9/16). By the European Middle Ages, anatomists were describing arteriosclerosis as “natural to old age” (Long, 1933). Approaching the modern era, the records, scarce as they are, also show cardiovascular disease as a major cause of death in older adult ages. In 19th and mid-20th century England and Sweden, which had low life expectancy, cardiovascular disease was one of the two most important causes of mortality at the oldest ages (Preston et al, 1972; Preston, 1976). For cohorts born after the first decade of the 1800s, the deaths recognized as due to cardiovascular diseases exceed those attributed to infectious conditions. From the earliest date in Sweden, deaths from cardiovascular disease are two times higher than from infectious conditions for those 70–74. For the U.S. Civil War, Fogel and colleagues compared doctors’ reports of heart disease from Union Army veterans aged 65 and over in 1910 versus veterans of the same age in 1983. Heart disease was nearly twice as prevalent in the U.S. Civil War Veterans (76% vs. 40%, age-adjusted) (Fogel, 2004, p. 31). William Osler’s statement from 1892 still holds true today, “Longevity is a vascular question, which has been well expressed in the axiom that ‘a man is as old as his arteries.’ To a majority of men, death comes primarily or secondarily through this portal.” (Osler, 1892, p. 664).

Moreover, early human ancestors were also likely to incur vascular pathology. Chimpanzees, our closest biological relative, also show extensive hypercholesterolemia, even on non-atherogenic diets, and die from heart attacks and strokes in captivity (Finch and Stanford, 2004; Steinetz et al, 1996) (Section 6.2). Crimmins and I provisionally conclude that vascular pathology during aging has been prevalent throughout human history and, quite possibly, throughout human pre-history as well (Crimmins and Finch, 2006a).

Crimmins and I are evaluating the role of infection and inflammation on later mortality in historical cohorts (Finch and Crimmins, 2004; Crimmins and Finch, 2006a, b). According to our ‘cohort morbidity hypothesis,’ exposure to infections early in life causes chronic infections that, in turn, promote vascular disease, leading to earlier mortality. Tuberculosis, Helicobacter pylori, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and other gastro-intestinal pathogens noted above are among many chronic infections that have recently diminished. The human environment in rural and urban areas alike was typically filthy by modern standards, with gross continuing exposure to human and animal feces. Running water was not available for convenient washing and bathing. Conditions gradually improved with national efforts in public hygiene even before the identification of infectious pathogens and development of immunization at the end of the 19th century. Besides the infectious environment, it was difficult to keep clothes clean and free of ectoparasites, especially before the availability of cheap cotton for clothing, which is easier to wash than wool or leather. Improved nutrition was another major factor in resistance to infectious conditions, due to agricultural improvements and the development of national transport systems of canal and rail (Fogel and Costa, 1997; Fogel, 2004; McKeown, 1976).

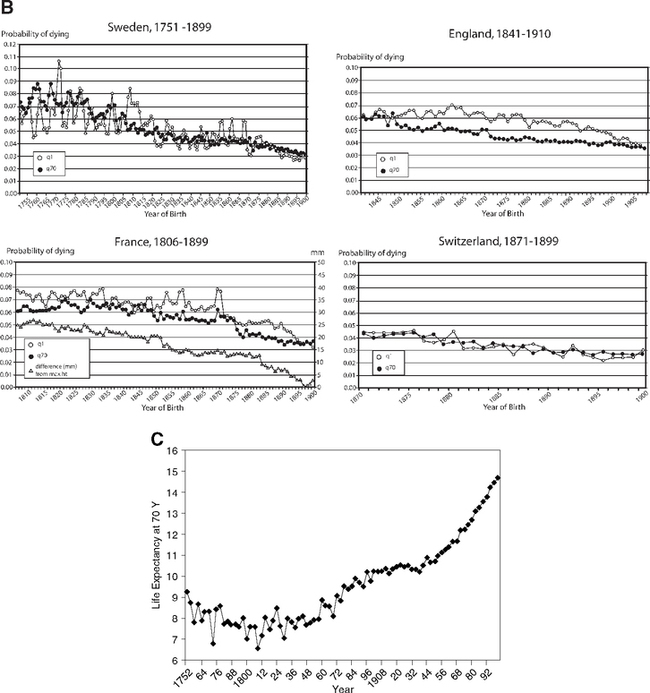

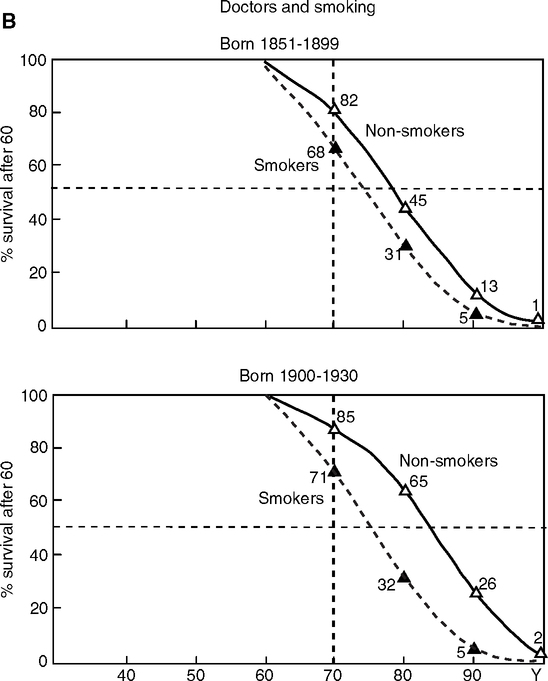

We chose to consider birth cohorts before the 20th century when infections were very common or rampant, but before tobacco smoking became popular. Smoking is a major inflammatory stimulus, as discussed above. Complete birth and death records are available from Sweden from 1751. Sweden also pioneered a national program of inoculation against small pox, begun in 1756, which attenuated these epidemics by the 1820s, decades ahead of other European countries (Skold, 2000). We also included England (1841–1899), France (1806–1899), and Switzerland (1871–1899). These early cohorts also did not benefit from antibiotics, which were not widely available before 1950. All the old age mortality examined occurred before 1973. In many countries, dramatic declines in mortality after 1970 are explained best by lifestyle and medical factors.

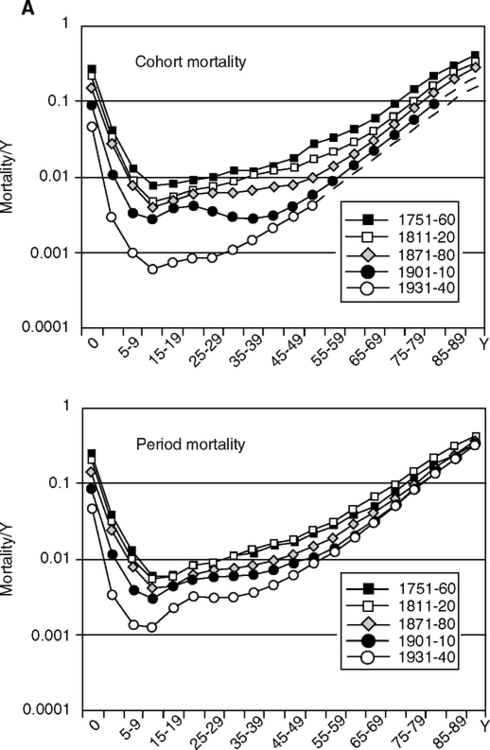

Initial life expectancy was low due to high early mortality characteristic of preindustrial societies, but increased considerably by 1899 (Fig. 2.7A). The historical trends for declining childhood mortality and old age mortality were remarkably parallel in Sweden, England, and France (Fig. 2.7B). As early age mortality declined, so did later age mortality in the survivors, seven decades later. The increased life expectancy at age 70 was clear in Sweden by 1850 (Fig. 2.7C). These findings support my early estimate that the steady historical increase in the adult age when mortality reaches 1% implies a slowing of aging processes (Finch, 1969, p.12).

These associations were tested with regression models for the relationships of temporal change in mortality at ages 70–74 with four childhood stages: infancy, <1 year; early childhood, 1–4; later childhood, 5–9; and adolescence, 10–14 years (Crimmins and Finch, 2006a). Infant mortality is largely attributed to infections. A key feature of this analysis is the comparison of birth cohort, followed throughout life, with the same ages in the corresponding periods. The results are consistent across these four countries: Most of the variance in old age mortality is explained by the early mortality in that birth cohort, 87–96%. The early and later mortality association of cohorts was much stronger than for periods. At a given year, the older adults in a population were born seven decades before the children and had experienced different environments that had a stronger effect on their mortality than in the current environment. Mortality of intermediate adult ages also did not predict old age mortality. The overall mortality curves shift downward quite uniformly as early mortality improves (Fig. 2.7A). Separate analysis of males and females also showed consistent associations in cohorts between early and later mortality (Crimmins and Finch, 2006b). Many specific mechanisms can be considered in cohort morbidity through which recurrent exposure to acute infections or continiued chronic infections accelerates atherosclerosis as well as causing direct damage to heart valves and myocardium (focal lesions and diffuse fibrosis). Extensive immune activation through hyperantigenic stimulation of T cells could also have increased T cell participation in atheroma instability (Section 1.5).

Height was also examined because infections slow growth (Section 4.4). The level of early mortality strongly predicted adult height (Fig. 2.7B). In birth cohorts with high early mortality, the survivors were shorter as adults, which we attribute to the greater exposure to infections in childhood. Infections and inflammation cause the reallocation of metabolic resources and energy from growth (Fig. 1.2B), as discussed in detail in Chapter 4. There are also associations of inflammatory genes with fetal growth (TNFa-308 G/G is more prevalent in lower birthweights) (Casano-Sancho et al, 2006) (Section et al 4.10.1). These mechanisms may also account for the progressively decreasing size of adults after 50,000 years ago in human pre-history (Chapter 6, Fig. 6.7).

Our model of inflammation in the pathobiology of aging (Fig. 1.2A) also includes important links between maternal infections and inflammation to fetal and infant growth and inflammation. Influenza, malaria, and tuberculosis were common maternal inflammations until recently (Riley, 2001). Malaria and possibly other maternal infections can retard fetal growth and increase fetal cytokines (Moormann et al, 1999) (Section 4.5). Smaller babies may have lower resistance to environmental pathogens. These possibilities are not included in the Barker hypothesis of fetal origins that focused on maternal malnutrition as the main cause of the fetal retardation effect on later vascular disease (Barker, 2004), discussed at length in Chapter 4. These manifold effects of inflammation and infection on growth during childhood and on later arterial disease point to a potential unifying theory of human development and aging.

2.5.2 Longer Rodent Life Spans with Improved Husbandry

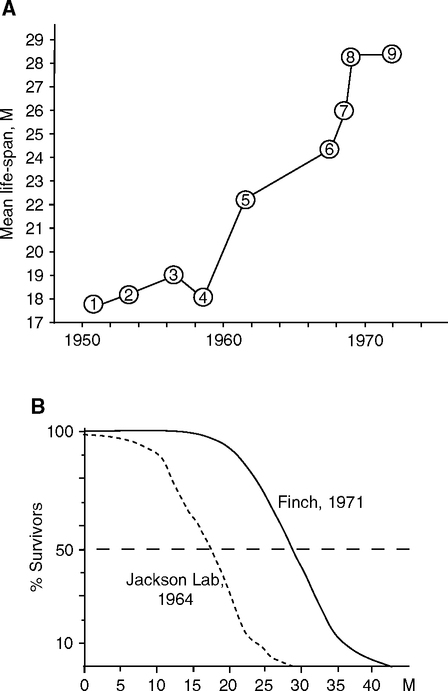

With intriguing parallels to the increasing human longevity discussed above, rodent life spans have nearly doubled in the past 50 y. Elimination of chronic infections through improved husbandry is a major factor. Additionally, arterial and myocardial disease may have been more severe in the early rodent colonies, as indicated for 19th century humans above.

Life span increases are best documented for mice of the C57BL/6J (‘B6’) strain, inbred since 1936 at the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), a pioneering center of mouse genetics (Staats, 1985). B6 males had mean life spans of 18 m in 1948–1956 (Russell, 1966) that gradually increased to the present range of 26–30 m (Finch, 1972; Kunstyr and Leuenberger, 1975) (Fig. 2.9.A, B). Survival curves became increasingly ‘rectangularized’ and right-shifted: Sporadic deaths before 20 m decreased, while maximum longevity increased from 30 to 44 m (Finch, 1969; Tanaka et al, 2000; Turturro et al, 2002). These right-shifts of mortality indicate reduction of infections and match those of human populations as health improved (Fig. 1.1A). Unfortunately, the pathology of aging was not well documented for B6 mice during this transition. In modern colonies of B6 mice, the cumulative incidence of cardiomyopathy is about 40% by 24 m (Schriner et al, 2005; Turturro et al, 2002) (Section 1.2.2). Rat life spans also increased during the same period: In McCay’s rat colony at Cornell University, where he conducted pioneering studies of nutirion and aging (Chapter 3), mean life span increased from 13 m in 1934 to 20 m in 1943 (McCay et al, 1943). Current lab rat life spans are 26-32 m.

Another striking example is the greatly improved longevity of dwarf mice with growth hormone deficiency. Thirty years ago, the Snell dwarf mouse was considered a model for accelerated aging because of short life span (< 6 m) and wizened appearance with gray hair, cataracts, and early onset tumors (Fabris et al, 1972) (Chapter 5, Table 5.3, footnote c). However, in the past decade with improved husbandry, dwarf mice have ‘switched teams’ to become models of slow aging, with life spans over 4 y and delayed onset of tumors. Gray hair is not common in contemporary dwarf mice and, in any case, is not a general trait of aging in B6 mice or other strains (Finch, 1973b). Husbandry improvements that enabled this remarkable transformation probably include reduced infections (see below) and better vivarium temperature control.

The general improvements in longevity across all genotypes of rodents in the past decades are not well understood. Even in the early days of laboratory rodent husbandry, some colonies were maintained well enough to achieve contemporary longevity. Slonaker’s rats lived up to age 46 m (Slonaker, 1912) (Chapter 3, footnote 5), while Robertson’s white mice averaged 25 m (Robertson and Ray, 1920) and the Berg-Simms colony females averaged 31 m in the 1960s (Chapter 1; footnote 3, this chapter), discussed below. I suggest that these early colonies were less inbred and closer to wild-types that were recently shown to have greater longevity (Harper et al, 2006a) (Chapter 3, Fig. 3.3).

Because the age-related pathology of aging mice at Jackson Labs before 1960 was not reported, we may look to the occasional reports on pathology from other early aging colonies.3 This scattered literature describes conditions in aging rats that may surprise readers. In the 1960s, Wexler and colleagues documented in detail that repetitive mating can accelerate arterial degeneration in males as well as females (Wexler and Miller, 1958, 1960; Wexler and True, 1963; Wexler, 1964; Wexler, 1976). These studies employed standard rat stocks (Holtzman, Long-Evans, Sprague-Dawley, Wistar) fed on low fat (4%) diets. Lesions developed in coronary and carotid arteries in proportion to the breeding experience. Heart valve damage was common. ACTH injections or restraint stress also accelerated spontaneous atherosclerosis. Wexler and colleagues postulated that the repetitive mating caused severe stress. It is impossible to define the conditions in Wexler’s colony that caused this level of stress during reproduction. Myocardial fibrosis was also associated with the severe coronary artery changes. In current clinical practice, myocardial fibrosis is associated with arrhythmias and sudden death (Siwik and Colucci, 2004; Zannad and Radauceanu, 2005).

Moreover, myocardial fibrosis with microscopic scarring was also common in several early rat colonies that may have contributed to premature death. “In older rats fibrosis may be so extensive that it is difficult to understand how the animals remain alive” (Fairweather, 1967, p. 227). Other examples include colonies with 60% prevalence of fibrosis (mild to severe fibrosis) by 20 m (Wilens and Sproul, 1938) and 100% by 20 m (Humphreys, 1957). In modern colonies, myocardial fibrosis is apparently uncommon and arises later (Bronson, 1990). Myocardial fibrosis is associated with inflammation and chronic stress (Holloszy and Smith, 1986), e.g., in rodent models, increased by TGF-β1 overexpression and decreased by TGF-β1 deficiency (Brooks et al, 2000; Siwik and Colucci, 2004). Diet-restricted humans have lower myocardial stiffness and plasma TGF-β1 (Section 3.3.2).

Arterial calcification was common in many early colonies but may be rarer today. In the Wilens-Sproul colony, calcification was noted in 46% in pulmonary arteries and 3% in coronary arteries and the aorta (Wilens and Sproul, 1938). In McCay’s colony, aortic calcification occurred in 20% of ad lib fed, but was unexpectedly 3-fold higher (60%) with diet restriction (McCay et al, 1939). Others described ‘bamboo stick aorta’ with disintegration of the elastic layers and secondary calcification resembling Monckeberg’s medial sclerosis (Fairweather, 1967; Mawdesley-Thomas, 1967; Wilgram, 1959). Sporadic arterial and myocardial calcification in aging rats was also reported by (Hummel, 1938; Wilgram, 1959). Moreover, calcification was associated with repetitive breeding in females (Gillman and Hathorn, 1959; Wexler, 1964). Current aging rodents have a low incidence of arterial calcification (<5%) (Bronson, 1990). Arterial calcification is associated with local nodules of Chlamydia pneumoniae in humans (Pierri et al, 2005) and in renal failure (Oh et al, 2002).

Coronary artery disease (CAD) was variable in the early colonies. The first report of spontaneous coronary disease on a normal (not fat-loaded) diet may have been from the Wilens-Sproul rat colony, in which 60% had some degree of coronary sclerosis by 24 m (Wilens and Sproul, 1938). Coronary artery stenosis to varying degrees was concurrent with myocardial fibrosis. In the Edinburgh colony, occlusive CAD with intimal plaques was present in 60% of rats by 17 m on a low-fat diet, causing complete blockage of a coronary vessel in some rats (Humphreys, 1957). In another colony, the incidence of coronary stenosis was about 15% (Wissler et al, 1954). CAD was particularly high in female ‘retired breeders’ (Wilgram and Ingle, 1959). However, in two other contemporary colonies, CAD was rare (Berg, 1967; Fairweather, 1967).

Three factors may be at work in the increased longevity of laboratory mice, ranked in reverse order of likeliness, in my opinion: genetics, diet, and infectious diseases. Improvements at the Jackson Laboratory occurred after 1959 when the Pedigreed Expansion Stock (begun in 1948) was moved to cleaner facilities (Russell, 1966). Longevity increases were not the result of intentional selection for longevity, although routine culling of sickly pups should lower overall mortality by reducing the pool of infections. The lack of correlation between life spans of parents and offspring in these early B6 colonies (Gunther Schlager, in Russell op. cit.) can be considered evidence against genetic drift (crosses of B6 and other strains clearly show inheritance of life span) (Jackson et al, 2002; Finch and Tanzi, 1997). Cardiomyopathies, nonetheless, may arise more frequently in aging rats maintained on diet restriction with exercise (McCarter et al, 1997) (Section 3.4.2). Dietary fat could be a factor because fatty diets can shorten life span (Chapter 3). The fats fed the first longevity group at Jackson are not known: The composition of the commercial diet was then a ‘trade secret’ (Elizabeth Russell, pers. comm.). In 1959, the Jackson Lab switched to Guilford Chow (11% fat, 19% protein), routinely given breeding females to enhance milk production. Chows with 4–5% fat are currently favored for aging studies (Finch et al, 1969; Turturro et al, 2002).

The major change from the 1940s to the 1970s at Jackson and elsewhere was reduction of chronic infections through improved animal and human hygiene. Some reported deaths from epidemic infections as merely ‘accidental’ (Robertson and Ray, 1920). Until the 1970s, laboratory colonies were often infected with microbial infections and skin parasites. Numerous pathogens were gradually minimized or eliminated, including bacteria (Salmonella, Mycoplasma); viruses [coronavirus; ectromelia (mousepox), mouse hepatitis virus, Sendai virus]; and ectoparasites (mites, pinworms) (Bell et al, 1964; Cotchin and Roe, 1967; Flynn et al, 1965; Miller and Nadon, 2000). Early colonies often had chronic respiratory disease (CRD) from endemic Mycoplasma4 recognized by wheezy breathing and crusty noses. While minimizing infections and dietary fat could only increase longevity, we may never know the causes of the extensive myocardial and arterial lesions described above. The Wilens-Sproul colony rats had numerous abscesses (‘suppurative lesions’) in brain, ears, genitourinary tract, and lungs (Wilens and Sproul, 1938).

Besides the Jackson Lab mice, another early benchmark rat colony was founded at Columbia University by Benjamin Berg and Henry Simms, which maintained advanced husbandry and exemplary documentation of age-related pathology (Fig. 1.5) (Berg, 1967; Simms and Berg, 1957; Simms and Berg, 1962). Although the Berg-Simms colony was begun in 1945, there was little respiratory disease (< 5% of rats). These rats were not selectively inbred, except to eliminate an ‘eye anomaly’ (Simms and Berg, 1957). Longevity in the Berg-Simms colony was in the range of modern colonies: females, median life span of 31 m and maximum of 34 m; males, median of 27 m and maximum of 29 m (Berg, 1976). Chronic lesions of aging approximated those of other rat strains in modern colonies (Bronson, 1990) and in the same age ranges: glomerulonephropathy arose before cardiomyopathy and abnormal growths (Simms and Berg, 1957; Simms and Berg, 1962), and arterial calcification was occasional. This health and longevity is remarkable for that time.

The current best practice in rodent husbandry is the ‘specific-pathogen free’ (SPF) colony, in which the pathogen load is regularly monitored with sentinel mice (Lindsey, 1998; Miller and Nadon, 2000). SPF status with minimal mycoplasmas and other pathogens increases fecundity and post-weaning growth and lowers spontaneous mortality (Bell et al, 1964). However, pathogen loads can fluctuate in SPF colonies with agents carried by humans and other adjacent lab animals (Taylor, 1974; Taylor and Doy, 1975). Infections are still embarrassingly common within SPF colonies at major research institutions (Jacoby and Lindsey, 1997). Although stricter barrier facilities can further reduce transmission of external infections, the expense and effort are prohibitive. Germ-free (axenic) animals lacking bacteria are problematic for aging studies: Their adaptive immunity is undeveloped, and their flaccid, grossly enlarged caecums develop fatal constrictions (volvulus) (Gordon et al, 1966).

Recent examples also show the importance of animal husbandry. Age-changes in skeletal muscle composition and function observed in ‘dirty’ colonies are negligible in aging rodents from SPF colonies of the same strains (Florini, 1989). Moreover, age-changes in rat liver protein oxidation (carbonyl content) disappeared in a subsequent cohort of the same strain of rats obtained 10 years later; these differences were confirmed with stored samples (Stadtman and Levine, 2003). Lastly, sporadic hippocampal neuron loss in aging may have been common in early colonies (Landfield et al, 1977; Meaney et al, 1988) but is not obvious currently (Gallagher et al, 1996; Rasmussen et al, 1996). Variable stress and infections may have been involved. Moreover, early reports of neuron loss (reduced density of large neurons) could be interpreted as neuron atrophy (Fig. 1.7A). In many ways, the hygiene of lab animals parallels that of humans in modern health care: We can minimize childhood infections by immunization and hygiene, but we remain vulnerable to sporadic epidemics. “La pest reste ici” (J.P. Sartre, The Plague, 1947).

2.6 ARE INFECTIONS A CAUSE OF OBESITY?

Viral infections as causes of obesity are being discussed because of evidence that four viruses cause obesity in vertebrate models and serological associations of obesity with infections in humans with obesity and glucose intolerance. These findings should be considered provisional.

This story began with the finding that mice developed obesity when infected as weanlings with canine distemper virus (CDV, paramyxovirus closely related to measles) (Lyons et al, 1982; Lyons et al, 2002). CDV causes focal lesions of hypothalamic appetite centers with selective loss of leptin receptors, POMC and catecholaminergic neurons in the arcuate nucleus, and hyperplasia of adipocytes and pancreatic islets. Obesity is also induced in other animal models by infections with scrapie (prion disease), Bornavirus, the retrovirus (RAV-7), and AD-36 (human group D adenovirus) (Atkinson et al, 2005; Lyons et al, 2002). In a recent study impressive for its large subject pools, AD-36 seropositivity was 3-fold more prevalent in obese adults (30% than controls, 11%; 502 Ss); moreover, in 28 twin pairs discordant for AD-36, the seropositive individual was fatter than the co-twin (Atkinson et al, 2005). Curiously, AD-36 seropositive individuals had lower cholesterol and triglycerides. In vitro, AD-36 infections of adipocytes decreased increased glucose uptake and leptin secretion; these effects depend on transient expression of viral mRNA, but not viral DNA replication (Rathood et al, 2007). Unlike CDV, no hypothalamic lesions have been found in AD-36 infected mice (Dhurandhar et al, 2000). Another study of obese men who were otherwise healthy found inverse correlations between insulin sensitivity and seropositivity for common infections (HSV-1 and -2, enterovirus, and C. pneumoniae; AD-36 was not included in this panel) (Fernandez-Real, 2006).

If the 30% prevalence of AD-36 seropositivity in obesity is generally validated, viral infections may contribute as much to obesity as life style behaviors of eating and exercise, and moreover, may be a causal factor in these behaviors by their impact on the hypothalamus. However, responses to viral infections depend on many factors of host defense, including food intake and exercise (Chapter 3). Resolution of cause and effect in these associations is difficult because obesity and diabetes increase vulnerability to infections (Falagas and Kompoti, 2006) (Chapter 3). Nonetheless, these recent findings support the suggestion of (Lyons et al, 1982) that viral infections have roles in sporadic childhood and adult obesity. AD-36 infections that lead to obesity by causing hypothalamic lesions could be another, and milder example, of viruses that propagate by modifying behaviors, although how obesity could particularly favor AD-36 viral propagation is far from obvious.

2.7 INFLAMMATION, DEMENTIA, AND COGNITIVE DECLINE

2.7.1 Alzheimer Disease

Infections may also be causes or promoters of Alzheimer disease (AD). This new possibility is even less settled than associations of infections with vascular disease. As a first example, identical Swedish twins who are discordant for dementia may also show long-term outcomes of infections. The first twin to be affected was 3.6-fold more likely to have had periodontal disease (Gatz et al, 2006). Periodontal disease is also associated with infections that interact with arterial lesions (see above), but links of infections to AD are even more speculative.

The current (and incomplete) evidence on infections and AD centers on herpes viruses and Chlamydia pneumoniae (Mattson, 2004; Ringheim, 2004; Robinson et al, 2004; Wozniak et al, 2005). Causality is elusive because these infections are ubiquitous. Herpes virus infections occur widely. Postmortem, about 2/3 of all brains, normal and Alzheimer, have HSV-1 (Itzhaki, 1997). HSV-1 infections reside in some brain regions affected by AD (frontal lobe and hippocampus), as well as the trigeminal ganglion. At later ages, HSV-1 infections appear to be active by the presence of HSV-1 antibodies in the cerebrospinal fluid of about half AD and normal controls (Wozniak et al, 2005). Clearly, AD can arise in the absence of active HSV-1 infections! However, in one sample, the apoE4 allele and HSV-1 co-occurred 10-fold more frequently in AD brains than normal elderly (PCR assay). ApoE4 carriers may have a greater risk of neurodegeneration from the activation of HSV-1 (Itzhaki et al, 1997). HSV-1 activation in the trigeminal ganglion causes shingles, which afflicts many elderly. A much rarer condition is herpes simplex encephalitis; survivors often have life-long cognitive impairments, possibly from neuronal apoptosis from HSV-1 (Aurelian, 2005). Other candidates are human herpes virus 6 (HHV6) seropositivity in Alzheimer (22% AD vs. 0% controls) (Wozniak et al, 2005) and CMV in vascular dementia (93% VascD vs. 34% controls) (Lin et al, 2001).

Some evidence suggests that vaccination against common infections may be protective. In the Canadian Study of Health and Aging, the risk of developing dementia during 5 years was lowered by vaccination for influenza (OR, 0.75), poliomyelitis (OR, 0.6), or diphtheria (OR, 0.41) (4392 Ss, aged ≥ 65) (Verreault et al, 2001). None of these infections is otherwise implicated in dementia. The protective effects of vaccination could be indirect by reduced vulnerability to other infections.

The case for C. pneumoniae as a casual factor in AD is less developed than for arterial disease. On one hand, C. pneumoniae persistently infects macrophages and can enter the brain, as in HIV (Stratton and Sriram, 2003). In a culture model, C. pneumoniae promoted monocyte migration across brain endothelia (MacIntyre et al, 2003). Infections of cultured human cerebral microvascular endothelial cells altered the levels of proteins associated with entry of this pathogen into the brain (increased β-catenin, N cadherin; decreased occludin) (MacIntyre et al, 2002). However, the evidence is mixed for the postmortem detection of infections. One study detected C. pneumoniae in cerebral vessels and glia in more Alzheimer brains than controls (Balin et al, 1998; MacIntyre et al, 2003). However, subsequent studies could not detect C. pneumoniae DNAs even in these same brains (Gieffers et al, 2000; Nochlin et al, 1999; Ring and Lyons, 2000). Vascular dementia studies were also mixed: positive association (Yamamoto et al, 2005) versus no association (Chan Carusone et al, 2004; Wozniak et al, 2003). Antibiotic treatment of AD patients with doxycycline and rifampin did not alter seropositivity for C. pneumoniae but, unexpectedly, slowed early cognitive declines (Loeb, 2004).

C. pneumoniae isolated from AD brains caused rapid formation of amyloid plaques in a normal mouse (BALB/c) (Little et al, 2004), which, like other ‘wildtype’ mice, never develops plaques during normal aging. Aβ1-42 containing plaques increased during the three months after infection, and a subset of plaques had fibrillar amyloid. Activated astrocytes around the plaques and distant from plaques suggest general inflammatory responses. Neuronal perikarya also had increased Aβ1-42, an early Alzheimer change (Section 1.6.3). The formation of fibrillar Aβ is puzzling because the mouse Aβ1-42 protein differs from the human in three substitutions that reduce aggregation (Section 1.6.). Nonetheless, mice overexpressing TGF-β1 (an inflammatory factor upregulated in Alzheimer brains) slowly developed fibrillar Aβ deposits around cortical microvessels; these deposits were preceded by thickening of the basement membrane. These changes are absent during aging in wild-type mice (Wyss-Coray et al, 2000).

Transgenic AD mice also show acceleration by systemic inflammation from i.p. injections of the endotoxin LPS (Godbout et al, 2005; Konsman et al, 2004; Scott et al, 2004). In the triple transgenic mouse model of AD, which has both amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary degeneration (Section 1.6), LPS caused earlier hyperphosphorylation of neuronal tau but, contrary to expectations, did not alter amyloid deposits (Kitazawa et al, 2005). In other AD transgenics, LPS induces APP and Aβ in neurons of the cerebral cortex and hippocampus, which are AD brain regions (Sheng et al, 2003). Microglial activation correlated strongly with neuronal APP and Aβ.

Aging mice had greater inflammatory responses and more prolonged ‘sickness behaviors’ in response to LPS (Godbout et al, 2005). The effects of aging on responses to LPS were not examined by these transgenic studies, which used relatively young mice. In stroke models, LPS pretreatment increases subsequent brain damage from cerebral artery blockade (Becker et al, 2005). Moreover, blood CRP is also elevated by LPS (Section 1.2) and elevated peripheral CRP increased damage from stroke in rats (Gill et al, 2004). Thus, in populations with high levels of infection and inflammation, stroke may cause greater brain damage and higher mortality. It is unclear if systemic endotoxins cross the blood-brain barrier. In rodents, systemic LPS binds to Toll-like receptors (TLRs) (Section 1.2 and Section 2.2.2 above) on cerebrovascular endothelia, which may increase vascular permeability to some sugars (Singh and Jiana, 2004).

Do environmental inflammogens promote AD? Smoking, while a strong risk factor in vascular disease (above), is not a clear risk factor for AD. While some case control studies indicate that smokers had lower risk of AD, recent cohort studies showed higher risk (Letenneur et al, 2004; Luchsinger and Mayeux, 2004; Sabbagh et al, 2005). Occupation and education are confounding variables. Smokers with AD may be younger at death but had the expected neuropathology (Sabbagh et al, 2005). Lastly, obesity and the metabolic syndrome are associated with chronic, low-grade inflammation (Section 1.7). As discussed in the next chapter, obesity and diabetes increase the risk of infections, while obese mice also have greater neuroinflammatory responses to LPS (Scott et al, 2004).

2.7.2 HIV, Dementia, and Amyloid

Dementia with memory loss is common in HIV sufferers with AIDS (acute immunodeficiency syndrome) (Selnes, 2005). The HIV virus enters the brain through macrophages but does not infect neurons with the production of further infectious virions. Diffuse damage and inflammation are found throughout the brain. Cases are often complex because of infections by other pathogens that cause diverse damage, e.g., demyelination (multifocal leukoencephalopathy) from the neurotropic JC virus (Del Valle and Pina-Oviedo, 2006).

Recently, diffuse amyloid Aβ deposits were found in the brains of AIDS patients (Green et al, 2005; Rempel and Pulliam, 2005) in proportion to the duration of infection (Fig. 2.10). The average age at death was 43 years, which is two decades before amyloid deposits become generally common. Nearly 50% of 150 brains from AIDS victims had diffuse Aβ deposits in the frontal cortex, most frequently near arteries (Green et al, 2005). Neuronal Aβ was also common, an early change in Alzheimer disease (Section 1.6.3). So far, AIDS brains have not shown two hallmarks of Alzheimer disease: compact neuritic plaques (Rempel and Pulliam, 2005) or neurofibrillary tangles (Green et al, 2005). These findings with well-characterized monoclonal antibodies confirm smaller studies of AIDS brains, which also included younger ages (Esiri et al, 1998; Izycka-Swieszewska et al, 2000; Rempel and Pulliam, 2005). Two mechanisms are noteworthy because of possible synergy: (I) induction of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) in neurons as an acute phase response during the brain inflammation of AIDS (Section 1.6.4) and (II) decreased degradation of Aβ by neprolysin, an endopeptidase enzymatically inhibited by Tat peptides from the HIV-encoded protein (Daily et al, 2006; Rempel and Pulliam, 2005). Both mechanisms should increase the production of oligomeric and solid Aβ. More information may be anticipated from HIV carriers who did not develop AIDS because of successful anti-viral therapy.

2.7.3 Peripheral Amyloids

Tissue amyloid deposits (amyloidosis) are associated with chronic infections, e.g., tuberculosis (de Beer et al, 1984, Sipe, 1994, Urban et al, 1993). Peripheral tissue amyloid accumulations are also increased by endemic bacterial flora and common endemic pathogens in mice. Specific-pathogen free mice of several genotypes had no tissue amyloids (thioflavin-binding, not otherwise characterized) up through 28 m (mean life span), whereas ‘conventional’ (dirtier) colonies had amyloid deposits (Lipman et al, 1993). In mice transgenic for mutant human transthyretin (TTR), the amyloid deposits of the gut and the penetrance of the mutant TTR-induced peripheral neuropathy (polyneuropathy) were strongly influenced by the microbial flora (Noguchi et al, 2002). TTR amyloidosis was increased by exposure to enterobacteria and yeast, and decreased by anaerobic cocci. Social stress or social deprivation may also influence amyloidosis, e.g., more amyloid accumulated during aging when mice were housed in groups versus solitary (Lipman et al, 1993).

2.7.4 Inflammation and Cognitive Decline During ‘Usual’ Aging

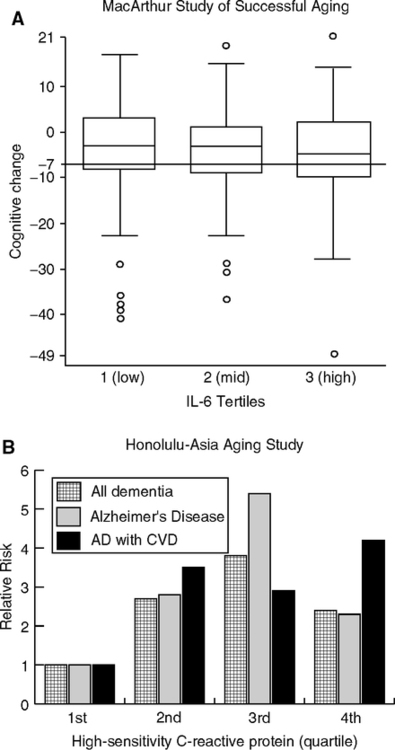

Elevations of CRP and other acute phase proteins are common at later ages in populations (Fig. 1.23) and may be modest risk factors of cognitive declines. The MacArthur Study of Successful Aging followed high performing elderly for 7 years in a carefully controlled analysis (Weaver et al, 2002). Elderly in the highest IL-6 tertile had twice the risk of cognitive decline (Fig. 2.10A). This subgroup may be > 25% of all elderly with elevated IL-6.

Other studies show similar risks. In the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study of well-functioning elderly (African American and Caucasian) (Yaffe et al, 2003), during 2 years, the top tertile of inflammatory markers showed a risk of cognitive declines in association with levels of CRP (OR 1.41) and IL-6 (OR, 1.34), but not for TNFa. During 5 years of observation, 23% had significant cognitive decline. Subgroups with both the metabolic syndrome (Chapter 1) and high inflammatory markers had 1.66-fold higher risk of cognitive impairment (Yaffe et al, 2004). In the Helsinki Aging Study over 5 years, the risk of cognitive decline increased with CRP < 5 mg/L (OR, 2.32) and diabetes (OR 2.18) (Tilvis et al, 2004).

However, the Longitudinal Aging Study (Amsterdam) found mixed associations: Cognitive decline was associated with elevated α1-antichymotrypsin (ACT), but not with elevations of CRP or IL-6 (Dik et al, 2005). In the Maastricht Aging Study (MAAS) for those over 50 during 6 years, elevated CRP was associated with decline in only one cognitive test (word learning) (Teunissen et al, 2003). The InCHIANTI study of aging in Tuscan communities documents the age-related increase of IL-6 and other acute phase proteins (Cesari et al, 2004) (Fig. 1.21) and may soon report on cognition. Overall, the associations of acute phase elevations and cognitive declines are modest and may not generalize between populations. Some divergences may be due to different tests used. But, a larger question lurks.

Do the cognitive declines in “normal aging” represent incipient dementia from Alzheimer or cerebrovascular disease? Although these studies of normal aging excluded individuals with signs of dementia at entry, none was designed to identify the early, preclinical stages (CDR 0.5 or mild cognitive impairment) (Section 1.6.3). However, the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study of men clearly shows associations of blood CRP at middle age with Alzheimer and vascular dementia 25 years later (Schmidt et al, 2002). Relative to the lowest quartile, the top three quartiles showed 3-fold higher risk of Alzheimer and vascular dementias 25 years later (Fig. 2.10B). The risks did not scale smoothly with CRP levels, but are highly significant for each of the top three quartiles: for Alzheimer, for vascular dementia, and for mixed cases. These associations were independent of cardiovascular disease in this sample, which may represent selective mortality. However, InCHIANTI attributed most of the elevations of CRP and other acute phase proteins to cardiovascular disease (Cesari et al, 2004). Seropositivity to C. pneumoniae was prevalent among the elderly and correlated with IL-6 and TNFa (Blanc et al, 2004). As noted in Section 1.5.4, vascular and Alzheimer disease share many risk factors including elevated acute phase proteins, elevated cholesterol, and hypertension.

2.8 IMMUNOSENESCENCE AND STEM CELLS

Immune system aging is very complex: Innate immunity tends to increase, exemplified by arterial macrophages and local inflammation, whereas adaptive immunity tends to develop restriction of repertoire from oligoclonality and depletion of T cells (Sections 1.2 and 1.5.1). Inflammatory processes may interact with aging in instructive immunity and stem cell generation.

2.8.1 Immunosenescence and Cumulative Exposure

The thymus is highly sensitive to atrophic changes during acute infections, which alter the critical micro-environment and impair thymocyte proliferation (Savino, 2006). During the life span, humans and other mammals show major shifts from naive T cells to memory T cells with progressively restricted repertoire (oligoclonality) (Sections 1.2.2 and 1.4.3). This aspect of immunosenescence can be accelerated by greater exposure to antigens. The ‘hyperstimulation hypothesis’ of naive T cell depletion is most strongly developed for the very common infections by cytomegalovirus (CMV). Deficits of memory cells and the presence of highly differentiated T cells with CMV-specificity are strongly linked to CMV seropositivity. These changes characterize an ‘immune risk phenotype’ with higher mortality in the elderly, observed in two European populations (Akbar and Fletcher, 2005; Huppert et al, 2003; Pawelec et al, 2005; Wikby et al, 2005). Continued antigenic stimulation is hypothesized to drive clonal expansions of memory T cells and is predicted to eventually clonally deplete cells with the highest antigenic affinity. Moreover, the hyperstimulation by one antigen can have bystander effects that activate other T cell specificities due to local secretion of IFNα and TNFa (Fletcher et al, 2005) (Section 1.4.3).

Although CMV is a ubiquitous infection, in 60–100% of adults depending on the population, nonetheless, some individuals reach old age without becoming seropositive. By comparison with CMV-seronegative individuals aged 22–91, healthy CMV-seropositive individuals with latent infections at all ages had 25–50% fewer naive T-cells and an increase of differentiated memory T cells (CD8+ CD28– effector cytotoxic) in all age groups, particularly the older (Almanzar et al, 2005). Moreover, IFγ expression is higher in CD8+ T cells with CMV-seropositivity, which would increase the body load of this powerful cytokine and possibly synergize with inflammatory processes throughout the body.

The hyperstimulation hypothesis of immunosenescence predicts that populations with chronic infectious disease should show premature T cell senescence. HIV is being examined from this perspective. Young HIV carriers have impaired T-cell responses to vacci-nation for preventing childhood infections; e.g., measles, polio, and influenza antigens induce weaker responses (Rubinstein et al, 2000; Setse et al, 2006). HIV-specific T cells have lower proliferation and cytotoxicity, both as found in immunosenescence of the elderly (van Baarle et al, 2005). Moreover, HIV patients show immune impairments to other antigens. Multiple immunizations with a T cell-dependent neoantigen (φ174, non-infectious bacteriophage) caused progressively smaller responses, unlike healthy controls, presumably because of the already limited pool of naive T cells; booster immunizations with φ174 also increased plasma HIV viremia (Rubinstein et al, 2000). These findings support the hyperstimulation hypothesis of immunosenescence.