The Human Life Span: Present, Past, and Future

Publisher Summary

This chapter considers the evolution of the human life span from shorter-lived great ape ancestors that ate much less meat and lived in low density populations. Human longevity may have evolved through “meat-adaptive genes” that allowed major increases of animal fat consumption and increased exposure to infection and inflammation not experienced by the great apes. Many outcomes of aging result from the irreplaceability of molecules and cells that are generated during development, under the control of gene regulatory programs. For molecules and cells that are replaced, aging damage may occur depending on turnover rate (life span). The loss of elasticity during arterial aging is a consequence of accrued damage to its irreplaceable elastin through inflammation and oxidative damage. Both changes contribute to the loss of arterial compliance and increased systolic pressure with aging, which is a major mortality risk factor. Fetal origins of adult vascular disease are seated in three intrinsic aging processes observed in optimal environments: aging of irreplaceable elastin; oxidation and cross linking of collagen and elastin from irreducible exposure to essential levels of glucose; and accumulation of lipids and activated macrophages in fetal aortas. Brain, kidney, muscle, ovary, and the adaptive immune system have limited cell regeneration in adults. Stem cells that can repair or regenerate arteries, brain, and muscle are attenuated by inflammation. Humans in particular have a remarkable range of behavioral, physiological, and pathological phenotypes throughout life.The chapter closes by discussing environmental trends and obesity, which may influence future longevity.

6.1 INTRODUCTION

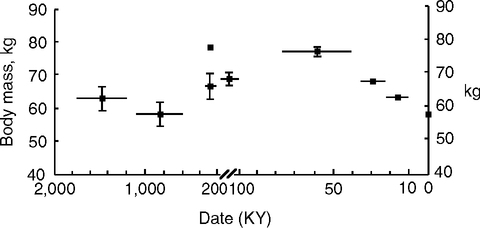

Human longevity may have evolved in two major stages. From an ancestral ape, 5 million years ago (MYA) or more, life spans doubled during the evolution of H. sapiens (Fig. 6.1, Table 6.1). We can not know the actual trajectory of change, which could have included fluctuations with decreases, as well as increases in life span during these several hundred thousand generations of Darwinian selection. Then, in less than 10 generations during the Industrial Revolution, life span doubled again, through processes that are seated in technology and culture, rather than genetic changes, particularly advances in hygiene, medicine, and public health, and improved nutrition and water (Section 2.5), which also increased adult height (Section 4.4).

TABLE 6.1

Stages in the Evolution of the Human Life Span, Brain, and Body Size

| Size | |||||

| Life Span | Brain, cc | Body, kg | |||

| Stage, YBP | Species | Median | Maximum | (95% CI) | |

| I, 7–5 million | chimp-human ancestora | 13 y | 50+ y | 400 | 30–40 |

| II, 4–3 | Australopithecus afarensus | ? | ? | 458 (335–580) | 39 (32–45) |

| III, 1.2–0.2 | Homo erectusb | ? | ? | 1003 (956–1051) | 61 (55–66) |

| IV, 0.6–0.1 | Early Pleistocene H. heidelbergensisb | ? | ? | 1204 (1130–1278) | 71 (62–80) |

| V, 0.15–0.1 | H. sapiensb/activity (Late Pleistocene) | 30–40e? | 80 y? | 1418 (1384–1452) | 64 (63–66) |

| 75,000–36,000 | /hunter-foragersc | ? | ? | 1498 | 76 |

| 21,000- 10,000 | /hunter-foragersc,d (Late Upper Pleistocene) | ? | ? | 1466 | 63 |

| <10,000 | /sedentism-agriculture | ? | ? | ||

| present | worldwided | 64 y | 122 y | 1349 | 58 (55–61) |

aThe shared ancestor is predicted to have had a life expectancy (LE) at birth, approximating that of wild chimps (Section 6.2.2), range 10–16 y, with average 12.9 (av. female, 14.6, and male, 11.2) (Hill et al, 2001). Sizes from Skinner and Wood, 2006.

bH. heidelbergensis is in a daughter lineage of H. erectus that spread after 600,000 YBP in Europe and possibly Asia, and is a possible shared ancestor of H. sapiens and H. neanderthalensis.

cHypothesized to resemble current hunter-foragers (Fig. 1.1A). About 60% of foragers survive to age 15, when their remaining life expectancy (q15) is about 35+, or 2-fold longer than the chimpanzee q15 of 15 (wild) and 23 (captive): Foragers and pre-industrial small societies, mean 36.7 [30.6–41.7, 95% confidence intervals] calculated from Hiwi, 28; Hadza, 33; Kung, 35; Ache, 38; Yanamomo, 41; Tsimane, 42; data from Gurven et al, 2007. These LE’s approximate those of preindustrial England, 1541–1741 (Oeppen and Vaupel, 2000): mean 36.7, [30.6–1.7, 95% CI] (Oeppen and Vaupel, 2000).

dGlobal life span (LE at birth) from Fig. 1.1 legend; maximum life span, Jeanne Calment (Allard et al, 1998); brain and body size from (Ruff et al, 1997).

eI chose not to present encephalization coefficient (EQ), a ratio of brain to body size, because of the lack of consensus on the allometric coefficient chosen and the variations between taxonomic orders (Balazs Horvath, 2007). Most analyses use EQ = brain mass/(11.22 × body mass)e0.76, calculated from a broad sample of mammals (Martin, 1981). However, a more detailed analysis of primates showed the best fit to e0.92 (Pagel and Harvey, 1988). It would be helpful to further resolve the EQ for the great ape clade and to account for the statistical uncertainties in size measurements (Auerbach and Ruff, 2004; Skinner and Wood, 2006). Two general trends seem clear during the last 2 million years: pre-Homo species had smaller bodies and brains, and the brain volume evolved faster than body height.

Some aging processes have been slowed relative to the great apes, despite increased exposure to infectious pathogens, inflammogens, toxins, and cholesterol-rich foods. The slowing of aging and the increase of longevity despite greater inflammatory exposures is paradoxical: Arterial disease, Alzheimer disease, and some cancers involve inflammatory processes (Chapter 1) that may be accelerated by infection and inflammation (Chapter 2) and fatty diet (Chapter 3). Conversely, diet restriction, opposite of the human preference, attenuates many of these conditions. Frequent food shortages are likely to have been the norm. Maternal metabolism and fetal growth are depressed by malnutrition yet still allow sufficient adult reproduction (Chapter 4). Variants of genes of insulin-signaling and lipid metabolism (Chapter 5) may have facilitated these evolutionary changes.

This chapter explores a new hypothesis that the pathogenic pathways in the chronic diseases of adult life were also critical to the evolution of longer human life spans ab origine. During evolution, our diet changed radically with major increase in cholesterol intake, as hunting and scavenging skills and technology advanced to allow a meat-rich diet. Moreover, humans were increasingly exposed to infections and inflammation from raw meat and later through high-density settlements with domestic excreta and smoky air. Besides containing enteric parasites and pathogenic bacteria, feces attract insects that are frequent vectors of infections. We do not know if the great recent reduction of infant mortality from decreased infections has modified the human gene pool by allowing survival of pathogen- or stress-sensitive genotypes.

The Queries of Section 1.1 will guide discussion of mechanisms fundamental to the evolution of human aging. Bystander damage from locally acting free radicals is emphasized to focus on proximal causes of molecular and cellular aging. These examples may be central to human evolution.

(I) Oxidative stress stimulates chronic inflammatory processes; e.g., glycotoxins in food that increase plasma oxidative markers also increase plasma CRP (human) and accelerate foam cell accumulation in aortic lesions (rodent) (Section 2.4.2.).

(II) Inflammation causes further bystander damage; e.g., particulate aerosols caused less lung damage in mice overexpressing extra-cellular SOD (Section 1.4.1).

(III) Diet and environmental pathogens influence chronic diseases with inflammatory components through bystander damage; e.g., Chlamydia pneumoniae accelerated arterial disease in hyperlipidemic rodents (Section 2.2.2).

Human evolution was dependent on attenuating bystander inflammatory damage to maintain health during the prolonged postnatal development and delayed onset of reproduction.

6.2 FROM GREAT APE TO HUMAN

6.2.1 Human Life History Evolution

During hominin1 evolution, life spans have more than doubled. Based on the life spans of the current great apes (Finch and Stanford, 2004; Gurven et al, 2007), the shared ancestor may have had a life expectancy at birth of under 20 years (Fig. 6.1, Table 6.1). The even shorter life spans of prosimians and monkeys implies that trends for increasing longevity with multiple births per pregnancy (polytocy) co-evolved in hominids with a life history schedule of singleton births, extended maternal care, and prolonged maturation (Fig. 6.2).

Humans are distinctive among primates for the greatest longevity and most prolonged maturation. We also evolved a unique social system of multi-generational caregiving and resource transfer to the Young (Hawkes, et al. 1998; Hawkes, 2006; Hill and Hurtado, 1996; Hrdy, 1981, 2005; Lee et al, 2003; Kaplan and Robson, 2002). The evolution of human longevity is hypothesized to be an outcome of selection for low mortality during prolonged maturation that also selected for lower mortality in older individuals who comprise the critical multi-generational human social matrix. In addition to the special role of grandmothers hypothesized by Hawkes and colleagues, input to the young is often provided by less directly related older and younger members of traditional communities (alloparenting) (Hrdy, 1981, 2005).

The shared ancestor of humans and the great apes is obscure. It seems best not to designate the shared ancestor by genus or species name because few hominid species persist in evolutionary time for more than 3–5 million years. DNA sequence evidence consistently shows that humans are more similar to the chimpanzee than gorilla or orangutan (Chen and Li, 2001; Wildman et al, 2003). If DNA insertionsdeletions (indels) are accounted for, then the overall similarity is about 95%, which equates to >40 million nucleotide differences (Britten, 2002). Gene expression profiles in the brain (anterior cingulate cortex) also concur with the ‘sister grouping’ of humans and chimps (Uddin et al, 2004). The time of divergence from a shared ancestor in Africa is estimated as 5–7 MYA (Kumar et al, 2005).

There are precious few fossils of hominins in the crucial time range 5–10 MYA (Fig. 6.2A): one possible chimpanzee fossil (0.55 MYA) and gorilla (1 MYA), but no orangutan. From 4.4–7 MYA (Upper Miocene), Ardipithecus and Orrorin in East Africa and Sahelanthropus in the present Sahara (Chad) are candidate ancestors of Australopithecus (4.1 MYA) and of Homo (1.8 MYA) (Brunet et al, 2002; Guy et al, 2005; White et al, 2006).

The poor resolution of these lineages and their inter-relationships have lead some scholars to challenge the definition of ‘hominid’ (Cela-Conde and Ayala, 2003). Many anatomical and behavioral traits of humans show greater similarity to orangutans than chimps (Grehan, 2006; Schwartz, 2004). Moreover, the chimp dentition resembles the orangutan more than other hominids (Pickford, 2005). Nonetheless, most agree that these early anthropoids were likely to have used bipedal postures. Bipedal movement on the ground and during arboreal foraging varies widely between chimp communities and may be a learned behavior (Stanford, 2006). Upper limb injury may also increase bipedalism, suggesting a different link of human evolution to risky behavior.

The unknown shared ancestor may have had a life expectancy of about 15 y, based on the life expectancy at birth of chimpanzee and other great apes (Table 6.1, note c). Maximum life spans are under 60 y in the wild and in captivity, with one likely exception.2 Far more is known about chimpanzee aging than other great apes. Survival plots show major differences between chimpanzees and selected human populations with high mortality relative to health-rich populations (Gurven et al, 2007). Fig. 6.3A compares ‘pre-industrialized’ foragers (hunter-gatherers), acculturated foragers, and a reference high-mortality historical population, mid-18th century Sweden. Mortality rates (Fig. 6.3B) and the ratios of mortality in these groups (Fig. 6.3C) demonstrate the critical feature that at all ages, wild chimps have higher mortality than foragers. Humans and chimpanzees diverge further after sexual maturity. Wild chimps aged 15 live about 15 more y. In great contrast, human foragers aged 15 live 40 or more y, with a modal age at death of about 70 (Fig. 6.1 legend) (Gurven and Kaplan, 2007). Thus, the chimp mean adult life span is about 60% shorter than foragers (Hill et al, 2001). I suggest that Paleolithic humans lived about as long as the current remaining foragers, 30–40 y. In the past 200 y, life span doubled again in health-rich populations (developed nations) (Fig. 6.1) (Table 6.1) (Chapter 2.4).

While humans have evolved remarkable longevity for a primate, this trend was already established in the apes, which live twofold longer than monkeys or prosimians (Fig. 6.2B). The four great ape species have single births spaced at long intervals, 4.5 to 10 y, with females becoming reproductive by age 10–15 (Fig. 6.4) (Wich et al, 2004; Goodall, 1986; Robson et al, 2006). Singleton births and prolonged maternal care characterize the four great apes, suggesting a long-standing trait of the hominid lineage of 10 million or more years. The postnatal development of humans thus further extends the canonical ape pattern of prolonged child care and postnatal development.

Great apes and humans also differ importantly in age at weaning and age at first birth (Sellen, 2006; Sellen, 2001; Wich et al, 2004; Kramer, 2004; Kennedy, 2005; Goodall, 1986). In natural fertility conditions, humans are weaned by 2–2.5 y, whereas chimps and other great apes delay weaning to age 5–10. The delayed weaning also delays the next pregnancy. The shorter intervals between successive births enables humans to reproduce more frequently, a crucial advantage that enabled progressive increases in early human population growth.

Human maturation is also prolonged. First births are delayed by 5 or more beyond the norm in great apes, and in some pre-industrial societies, occur as late as 20 (Robson et al, 2006; Wich et al, 2004; Gurven et al, 2006, 2007). Acquisition of skills for hunting extends the training period for full independence and adult competence beyond the maturation of other hunting mammals that are better equipped with specialized claws and teeth. Even after sexual maturation, further skills are acquired for hunting into the late 20s and possibly 30s (Gurven et al, 2006, 2007; Kaplan et al, 2000). It may not be trivial that modern professional training takes about as long as the acquisition of hunting prowess in foragers. Brain myelin maturation continues in humans into the third and fourth decades (Bartzokis et al, 2003; Sowell et al, 2001), and may be critical to the later acquisition of high-speed complex processing of executive functions and emotional controls that enable hunting and other cooperative human activities (Finch and Stanford, 2004).

Reproductive senescence may be earlier in chimpanzees than humans, but evidence is mixed. On one hand, several chimpanzees (the famous Flo and her daughter Fifi of the Gombe study area) had successful pregnancies after age 40 (Finch and Stanford, 2004; Goodall, 1983). However, cycles may lengthen after age 30 (Videan et al, 2006), while continuing in some individuals up to nearly age 50, just before death (Graham, 1979; Gould et al, 1981). Tentatively, chimp perimenopause may begin earlier than in humans, but may last longer in some individuals into the human age range. The few aged chimp ovaries examined show definitive loss of ovarian oocytes as in human menopause (Gould et al, 1981). In any case, the higher mortality in chimps enforces a much shorter average reproductive duration than in humans.

Only the mother gives child care in the chimp and orangutan, while the male gorilla is protective and regularly plays with his kid (Table 6.2) (Allman et al, 1998). However, a few primates have extensive paternal roles in child care: The Siamang (lesser ape) and Titi monkey fathers carry their infants and develop close bonds with their offspring. The sex survival ratios are also correlated with the level of paternal behaviors. Chimp males have the lowest relative survival, while human males are the most favored among the great apes. One view of the ethnographic-anthropological evidence is that men mainly supply economic support, but give limited direct child care. Allman and colleagues hypothesize that the greater paternal role selected for increased relative life expectancy in these species.

TABLE 6.2

Sex Ratios of Survival in Anthropoids

| Species | Survival Ratio, F/M | Male Care |

| Chimpanzee | 1.42 | rare |

| Orangutan | 1.27 | rare |

| Gorilla | 1.13 | protective, plays with kids |

| Human (Sweden 1780) | 1.05 | economic support, some care |

| Siamang (lesser ape) | 0.92 | carries infant in second year |

| Titi monkey | 0.83 | carries infant from birth |

From (Allman et al, 1998). Ratios rounded off. Chimpanzee and bonobo fathers are also observed to play with infants (Enomoto, 1990). However, these males do not remain with the females or their children, unlike the gorilla, which stays with his harem, and may even protect infants from other members of the group, including juveniles (Whitten, 1987).

These behavioral shifts in paternal roles suggest alterations in the Y chromosome that determine male phenotypes. Among the 60 active genes on the human Y chromosome, chimps incurred inactivating mutations in several genes that remain functional in humans (Hughes et al, 2005). The Y chromosomes also differ in the number of alu sequences and other repetitive ‘mobile’ elements and other non-coding sequences that influence gene expression (Kuroki et al, 2006). The great ape Y chromosomes show unusually extensive structural differences, indicating major reorganization in recent evolution: translocation of 100 kb DNA from chromosome 1 to the Y of a shared ancestor and, in humans, two subsequent inversions and a deletion (Wimmer et al, 2005). Although mutations in coding sequences are a main focus of genetic studies, chromosome reorganization can induce position effects in gene expression. The relationships of these mutational and structural changes to male phenotypes is unknown.

In addition to greater paternal involvement with longer male survival than is the norm, humans evolved multi-generational care giving lacking in great apes and other primates (Hawkes et al, 1998; Hill and Hurtado, 1996; Packer et al, 1998; Robson et al, 2006). Theoretical models show the importance of intergenerational resource transfer on mortality (Lee et al, 2003) and brain evolution (Kaplan and Robson, 2002). Our social networks allow earlier weaning and much shorter birth intervals, typically 2–3 years in natural fertility, relative to great ape norms. Traditional human societies provide child care and feeding, which allows rapidly succeeding pregnancies before the child is self-sufficient (Hrdy, 2005; Kaplan et al, 2000; Kaplan and Robson, 2002; Larke and Crews, 2006).

Also unlike the great apes, human birth is usually assisted. The increasing size of the human head requiring fetal rotation makes parturition more dangerous for mother and child, the human “obstetrical dilemma” from feto-pelvic disproportion (Rosenberg and Trevathan, 1996, 2002). In contrast, labor in the great apes “… occurs speedily and rarely with difficulty. … [due to] exceptionally wide birth canals …” (Schultz, 1969, p. 154). By the pelvic geometry, Australopithecenes and early Homo up through 0.7 MYA had easy, non-rotational births (Rosenberg, 1996; Trevathan, 2000; Rosenberg and Trevathan, 2002; Ruff, 1996; Abitbol, 1996a, b). The increasing feto-pelvic disproportion would have increased mortality at a critical time in brain evolution (Section 6.2.4).

The 3-fold lower human mortality before maturation relative to chimps (Fig. 6.3C) has huge importance to evolution of the human life history by allowing even later maturation with sufficient survival (Fig. 6.4). The later onset of first births in humans, about 19–20 in traditional hunter-foragers (Robson et al, 2006; Walker et al, 2006a), would not allow sufficient reproduction if mortality was as high as in the great apes. Fossil evidence does not inform when this major demographic shift occurred.

Less contact with feces and lower density physical contact are further differences of major importance to the level of infection and inflammation. [These concepts are being developed in collaboration with Robert Sapolsky.] Great apes typically make individual night nests, into which they defecate and urinate in the morning before departure (Goodall, 1986, p. 208, p. 545; Carel van Shaik, pers. comm.). Night nest reuse is uncommon in chimps and orangutans, and both species fastidiously avoid contact with feces and urine. Their daily movements, personal hygiene, and the largely arboreal habitat would reduce exposure to infections from organisms supported by excreta that are nutrient-rich and biotrophic. Only mothers and their single child sleep next to each other, which also reduces exposure to communal infections. Moreover, groups are usually small, rarely as large as 30 individuals (ape communities change frequently by fission and fusion). Nonetheless, diarrhea and parasitic diseases are ubiquitous in feral ape populations (Goodall, 1986, pp. 93–96). Human societies have consistently even higher exposure to their excreta and other biotrophic wastes from their sedentism at higher density and numerous infants and small children. Even migratory hunter-gatherers typically maintain base camps for extended times that typically accumulate feces.

6.2.2 Chimpanzee Aging

Corresponding to the earlier mortality acceleration in chimps, physical signs of aging begin about 20 years earlier [see detailed reviews (Finch and Sapolsky, 1999; Finch and Stanford, 2004)]. Wild chimps often look decrepit by their adult life expectancy because of sagging skin, dental damage, and traumatic injuries from fighting and falls (Goodall, 1986, p. 104). At later ages, movements are slowed and tree-climbing is more difficult. Emaciation is common before death. Bone thinning (Lovell, 2000) and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) (Steiner et al, 1999) are noted by age 40. Female reproductive cycles lengthen in the 30s with trends to increasing FSH and LH that are characteristic of peri-menopause (Videan et al, 2006). However, by ovarian histology, menopause with oocyte depletion may occur after 50 in some individuals, as in humans (Gould et al, 1981; Graham, 1979; Graham et al, 1979). In feral populations, most chimpanzees die before reaching menopause.

Another major species difference is that neurodegenerative changes are very mild by age 50. The few brains of chimps and orangutans examined had limited Aβ in plaques and arteries (congophilic angiopathy), but no neurofibrillary degeneration or large neuron loss (Erwin et al, 2002; Gearing et al, 1997). In contrast, macaque monkeys have earlier and heavier Aβ amyloid deposits by age 30, as does the gray mouse lemur by age 10 (reviewed in Finch and Sapolsky, 1999). These species differences must involve differences in amyloid metabolism (expression, processing, catabolism, and clearance) because all primates have the same Aβ peptide sequence (Section 1.2.2). Moreover, gene expression profiling showed little similarity in aging changes between chimp and human cerebral cortex (Fraser et al, 2005). The great apes may have fewer Alzheimer-type changes because their apoE is functionally more like apoE3 than apoE4 and possible dietary effects linked to the human intake of fat and metals from meat-eating (see below).

Lacking Alzheimer-like changes, chimps are vulnerable to arterial pathology [detailed summary of the scattered data in (Finch and Stanford, 2004), Table 6.3 and notes]: At autopsy of wild chimps shot for this purpose in the old Belgian Congo, 2/4 adults of unknown ages had aortic plaques (Vastesaeger and Delcourt, 1961). At the Yerkes Primate Center breeding colony, all adults had fatty lesions in the aorta and cerebral arteries, which were further increased by fatty diets (Andrus et al, 1968). At one time, chimpanzees were considered the “perfect model” for human arterial disease (Bourne and Sandler, 1973). Blood cholesterol was elevated to clinical levels in captive chimps and possibly in gorilla and orangutan (Table 6.3). Some studies, but not all (Finch and Stanford, 2004, pp. 14–15), observed extreme sensitivity to diet-induced hypercholesterolemia and to arterial disease. The older literature suggests that, even on ‘normal diets,’ sudden death from heart attacks and strokes may be common (Finch and Stanford, 2004, Table 1, footnote 3; Table 3B, and Appendix). Tooth wear is extensive and periodontal infections are common. According to many incidental observations, adult males are vulnerable to sudden cardiac arrest without evidence of coronary ischemia. Recall here the associations of periodontal infections and cardiovascular diseases (Section 2.3.1). In captivity, obesity is common, particularly in females on ‘non-atherogenic’ diets (Steinetz et al, 1996). We need detailed analyses of captive chimp vascular, myocardial, and dental pathology, and of blood lipids in relation to various diets, which often include animal fat and dairy products (Conklin-Brittain et al, 2002).

TABLE 6.3

Cholesterol Levels in Captive Great Apes (% of sample)

| Blood Cholesterol | Chimpanzeea | Gorillab | Orangutanc | Monkeyd |

| High ≥ 240 mg/dl | 34% | 100% | 100% | |

| Borderline 200–239 | 47% | |||

| Normal <200 | 19% | 100% |

Chimpanzee data summarized from (Finch and Stanford, 2004, Table 3A). The most detailed recent study of chimps is (Steinetz et al, 1996). Other species from (Srinivasan et al, 1976a,b).

a17 groups of animals, 240 animals

b2 groups, 11 animals

c2 animals

d142 animals

Monkeys also show vulnerability to lipid-rich diets in inducing accelerated vascular disease (Clarkson, 1998) and Alzheimer-like changes. Although no great ape has been studied for nutritional effects on neurodegeneration, in vervet monkeys fed for 5 y on a diet rich in saturated fats the deposition of Aβ was accelerated (Schmechel et al, 2002). Similarly, diets rich in cholesterol and fat induce Aβ deposition and other Alzheimer-like changes in rabbits and in transgenic mice with a human Alzheimer gene (Levin-Allerhand et al, 2002; Refolo et al, 2001; Shie et al, 2002). In cell culture models, added cholesterol increases Aβ production from APP by altering the subcellular distribution of BACE1 (Ehehalt et al, 2004; Kojro et al, 2001; Mills et al, 1999; Puglielli et al, 2001). Thus, the shift to cholesterol-rich diets in human ancestors could have accelerated the mild level of Alzheimer changes seen in the great apes. Provisionally, we may conclude from this varied literature that captive chimps are at least as vulnerable as humans to hypercholesterolemia and vascular disease on rich diets without regular demanding exercise.

6.2.3 The Evolution of Meat-Eating

Diet is another major difference: Unlike humans, the great apes are primarily herbivores (Table 6.4), a long-standing characteristic of this clade for 35 million years (Milton, 1993; Stanford, 1999). While comprehensive dietary data are lacking, the typical caloric intake of chimps from animal tissues is about 5% of the total, which is far below human norms. Additionally, males in some chimp communities hunt and eat monkeys and other small mammals (Goodall, 1986; Boesch and Boesch, 1989; Stanford, 1998), with some averaging 70 g meat per day. Meat-sharing has a primarily social role in attracting females and in social favors by subordinate males. However, the regular consumption of meat is not essential to chimp survival, because some chimp communities have not been observed to hunt or to eat meat. And, in those communities, meat is rarely consumed by pregnant or nursing chimps (Finch and Stanford, 2004, pp. 8–12). Thus, hunting behaviors may be cultural and socially learned, as is the different tool use between chimp communities (Whiten et al, 1999; Sanz et al, 2004). Nonetheless, important nutrients are obtained from insects. Chimps in particular search for fatty termite larvae, using thin sticks for ‘termite dipping’, and females may ingest 65 g wet weight per day (McGrew, 2001). Bird eggs are also occasionally eaten. This consumption of fat is still much below human norms, e.g. fat is 15–25% of dry weight in the modern ‘western’ diet and 38–49% of foragers (Kaplan et al, 2000; Cordain et al, 2001; Cordain et al, 2002a,b; Conklin-Brittain et al, 2002; Eaton et al, 2002).

TABLE 6.4

Meat Sources of African Great Apes and Human Ancestors

| Pana Chimp | Gorillaa | Pongoa Orangutan | Australopithecusb | H. ErgasterIc | H. neanderthalensisd | H. sapiens, Paleolithice | |

| cannibalization | YES | NO | NO | ? | ? | YES | YES |

| mammal | |||||||

| skeletal muscle | YES | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| brain | YES | NO | NO | ? | ? | YES | YES |

| bone marrow | YES | NO | NO | ? | YES | YES | YES |

| viscera | YES | NO | NO | ? | ? | ? | YES |

| reptile- bird | RARE | NO | RARE | ? | ? | YES | YES |

| eggs | RARE | NO | RARE | ? | ? | ? | YES |

| fish | NO | NO | NO | ? | ? | ? | LIKELY |

| insect | YES | YES | RARE | LIKELY | LIKELY | LIKELY | LIKELY |

Table directly from (Finch and Stanford, 2004). New entry for orangutan provided by Craig Stanford.

aOrgans consumed by chimpanzees (Stanford, 1999; Stanford, 2001). Both chimp sexes occasionally kill and eat the infants of other females in their group. Cannibalism is very rare in bonobos, gorillas, or orangutans (Goodall, 1986). Orangutans incidentally ingest insects with fruit and may randomly pluck them from leaves.*

bAustralopithecus 2.5 MYA extracted marrow from long bones, as indicated by induced fractures (e.g., (de Heinzelin et al, 1999). Some Australopithicenes (’robust taxa’) had large chewing muscles and large, thickly enameled cheek teeth indicative of herbivory (e.g., (Andrews and Martin, 1991). Stone tools were very limited and crude.

cEarly Homo had smaller molars than Australopithecus (Andrews and Martin, 1991), suggesting less reliance on tough fibrous plants, consistent with evidence for tool use in obtaining meat by scavenging or hunting.

dNeanderthals obtained most protein from animal sources (isotopic analysis, *15N), approximating that eaten by non-human carnivores (Richards et al, 2000).

eSome modern hunter-gatherers, e.g., the Aché, save prey animal brains for their young children (Hillard Kaplan, pers. comm.).

“Meat made us human” is Bunn’s trenchant phrase (Bunn, 2007, p. 191). The meat-rich diet preferred by humans is strongly implicated in the evolution of the brain and complex social behaviors (Dart, 1953; Kaplan et al, 2000; Milton, 1993; Milton, 1999; Stanford, 1999). Meat provides a rich package of nutrients that greatly reduce the time spent in foraging. Chimps are occupied 75% of the waking day in searching for plant foods, which are mainly low-yield (Finch and Stanford, 2004, p. 8). The evolution of hunting and meat-eating thus made available high energy rich meals that take less time to digest, and that also reduce the necessity of all members of the group to spend every day of their lives in endless foraging. The huge increase in consumption of carrion exposed early humans to huge increases in cholesterol, but also to increased biohazards from infections and toxins. With Robert Sapolsky and Craig Stanford, I have developed the hypothesis that these huge shifts in diet and life history strategy were enabled by the evolution of ‘meat-adaptive’ genes, including the apoE alleles, which enabled increased longevity together with increased consumption of meat (Finch and Sapolsky, 1999; Finch and Stanford, 2004).

Besides its value to adults as an energy dense food, meat also provides a rich source of essential polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), which are required for normal brain development (Cordain, 2001; Cordain et al, 2002a,b; Eaton, 2002; Finch and Stanford, 2004, pp. 11––2). Arachidonic acid (AA) and docohexanoic acid (DHA) are made from different PUFA precursors (Section 2.9.5). Because PUFAs are scarce in plant material, their availability to children could decrease the risk of marginal neurological impairments from sporadic deficits. PUFA levels may influence brain development even on ‘normal diets,’ and in one study AA:DHA levels in mother milk strongly correlated with neonatal brain growth (Xiang et al, 2000). Vitamin B12 is also not provided by plant foods. It is cogent that some children given vegan-macrobiotic diets have a higher incidence of mild cognitive impairment and slower growth that is not corrected by supplements (Louwman, 2000; Van Dusseldorp et al, 1999). A lower risk of retarded development would have favored the acquisition of the skills for hunting and foraging.

By 2.6 MYA, mammalian prey bones were associated with Australopithecus at Oldovai Gorge in East Africa. Many bone cuts and breaks are consistent with the use of stone tools to remove flesh and crack long bones for marrow (Blumenschine and Pobiner, 2007; Bunn, 2007; Shipman, 1986; Asfaw et al, 1999; Shea, 2007). The lack of evidence for clubs or large weapons suggests that large carcasses were scavenged (Bunn, 2007). Cooperative transport of carcasses is suggested by the numbers of large bones at one site (FLK Zinj), which exceeded the regional density of these species. Brain and body size were slightly larger than in chimps (Table 6.1; see footnote for comment on encephalization coefficients).

The diet is inferred from the natural isotopic [13C] composition of tooth enamel. Australopithecus africanus 3 MYA appears omnivorous, with greater isotopic similarity to hyenas than to grazers and browsers (Sponheimer, 1999; Sponheimer et al, 1999, 2007). These authors emphasize that the isotopic composition cannot resolve if the source of the isotope was directly ingested plant material or indirectly transferred through the flesh of an animal that ate the plant material. A wide variety of wild-plant foods was available in East and Southern Africa, including some with high nutritional values (Bunn, 2007; Peters, 2007; Sept, 2007). Australopithecenes had relatively larger teeth than all species of Homo, implying the greater importance of fibrous plants to their diet (Wrangham, 2007).

Early Homo by 1.8 MYA clearly used tools and, by isotopic evidence, was also an omnivore. By 1.8–1.6 MYA, H. erectus occupied a broad belt extending from East Africa to Java (Rightmire et al, 2006). In the recently developed Dmanisi site in the Caucasus (1.77 MYA), brain estimates are under 1000 cc, even as small at 600 cc; these size variations suggest sex differences (Rightmire, 2004). One toothless adult skull shows resorption of tooth sockets and extensive jaw bone remodeling, suggesting that this individual had impaired chewing for some years (Lordkipanidze et al, 2005). Survival in the cold climate of the Caucasus with such major impairments implies access to foods that don’t require mastication, possibly mashes made from nuts or tubers, or soft tissues such as marrow and brain. There is no evidence for controlled use of fire for cooking, which would soften tubers for easier ingestion, until 0.5 MYA at the earliest (Wrangham and Conklin-Brittain, 2003; Wrangham, 2007).

Hunting technology advanced remarkably after 0.5 MYA, concurrently with further brain size evolution in H. erectus (Fig. 6.5). The earliest evidence of spears is 0.3–0.4 MYA in Schöningen (Gaudzinski and Roebroeks, 2000; Thieme, 1997). H. erectus in this region of Europe had brains of about 1000 cc. The Schöningen site finds include a remarkable series of long spears and other crafted wooden tools; flint scrapers; thousands of bones, many with cut marks; and fireplaces. Horse skeletons dominate over smaller bones of other mammals, birds, and fish. This evident ability to hunt a large herd animal and bring the carrion to one place implies that hunting was highly organized and suggests large-scale meat-eating; however, bone evidence does not inform on the frequency of meat-eating (O’Connell et al, 2002).

A daughter lineage of H. erectus may have lead to H. heidelbergensis, which had a larger brain (ca. 1200 cc) and is a possible shared ancestor of H. sapiens with H. neanderthal (Rightmire, 2004). Comparable skeletons of H. heidelbergensis have been found in Africa, but not H. neanderthal. Neandertals in Europe and Western Asia independently evolved large brains as large or larger than most modern humans (1200–1700 cc) and survived to 34,000 years before present (YBP) in the region of southern France (Hublin et al, 1996). The earliest anatomically modern H. sapiens skeleton dates to 195,000 YBP (Omo Kibish, Ethiopia) (McDougall et al, 2005). East Africa continues to be the most likely region of origin of modern H. sapiens (Ray et al, 2005; Grine et al, 2007).

By 100,000 YBP (Late Pleistocene), skilled extraction of bone marrow and brains is well documented (Gaudzinski and Roebroeks, 2000). Isotope signatures of neanderthal bones resemble those in non-human carnivores, suggesting that animal tissues were also their main protein sources (Richards et al, 2000). Cannibalism is evidenced by cut marks that could have been made during removal of marrow and the tongue. At one neandertal cave (Moula-Guercy, 100,000 YBP), all human crania and limb bones had cut marks and fractures (Defleur et al, 1999). Cannibalization is known only in chimps among the great apes, but may have been a long-standing human practice (Table 6.4). By 60,000 YBP in South Africa, plant fibers were apparently used to bind shaped stones to spear shafts (Lombard, 2005), which suggests further advances in hunting technology.

Humans also evolved distinctive fat depots. In pregnancies of captive chimps and other great apes, the newborn have remarkably less subcutaneous fat than characteristic of humans (Kuzawa, 1998; Robson et al, 2006; Schultz, 1969). Schultz also noted picturesquely “… newly born … monkeys and apes resemble in their faces emaciated and toothless old men … due to the lack [of] the padding of subcutaneous fat which appears in man before birth and normally persists throughout infantile life.” (op. cit, p. 114). In allometric comparisons with other mammals, human neonates are several-fold fatter for their size (Kuzawa, 1998). Frustratingly, none of the species compared with humans were primates. Moreover, Schultz’s ‘in the gross’ observations of great apes could be misleading because visceral fat depots were not characterized. The needed data on primates can now be easily obtained with MRI.

The fat content of human infants increases further to a maximum of about 25% body weight by 6–9m, accounting for about half of the weight gain and more than half of total caloric intake (Kuzawa, 1998). The age of peak adiposity approximates the beginning of weaning, when transitional foods are introduced and when the risk of exogenous infections increases. The importance of neonatal fat is also shown in the babies of malnourished South Indian women, which had conspicuous subcutaneous fat, despite their low birthweight (Section 4.4.4). The uniquely human acquisition of breast fat before pregnancy may have evolved as a hedge for uncertain resources (Kuzawa, 1998; Robson et al, 2006).

In the great apes, breast development is delayed until pregnancy. Breast fat in particular is adaptive because it sustains nursing when resources are unpredictable. Skeletal evidence does not tell when breast fat began to be acquired before pregnancy in evolving human lineages. The great range of breast development before pregnancy is not obviously associated with subsequent milk production or success in nursing. Also recall the remarkable metabolic adaptations to energy limitations during pregnancy (Fig. 4.8). Humans have many individual variations in somatic fat deposits (abdominal, breast, steatapygic, and subcutaneous), suggesting genetic variations beyond the sex differences.

The fertility goddess figures of the Upper Paleolithic, such the Venus of Willendorf from 21,000 YBP on this book’s cover4, suggest an ancient ideal of fat, perhaps even an ideology, that represented survival advantages from stored nutritional reserves. Her broad hips also suggest easy child-bearing. Many other plump and broad hipped statues are found in Neolithic and Chalcolithic settlements throughout Europe and Western Asia (Hodder, 2004; Gimbutas, 1982). An intrigu ing statuette from a Çatalhöyük grain bin portrays a seated fat lady with plump limbs and pendulous breasts and belly (Hodder, 2006, Plate 24). Being ‘overweight’ by current standards may have caused far fewer ill effects within the shorter life spans of those days. Or, perhaps any consequences of obesity (Fig. 3.4) were outweighed by the greater reproductive success of women with ample fat reserves who could sustain nursing and for normal postnatal growth during seasonal fluctuations in food availability (Kuzawa, 1998; Sellen, 2006). The idea that plumpness and health coexist continues today in the pot-bellied Buddha statues found in many Asian households and shrines which represent prosperity and fertility.

6.2.4 Meat Adaptive Genes

The evolution of meat-eating poses an important puzzle. Given that diet restriction in lab rodents and monkeys slows aging processes associated with obesity and hyperlipidemia (Chapter 3), we may ask what genetic changes enabled human ancestors to shift to high fat content diet and to double the life expectancy. On many grounds, the major increase of meat-eating would be predicted to shorten, not lengthen, life span. If the atherogenic lipid profile of captive chimps is any index (Section 6.2.2), increased meat ingestion would have increased vascular-related deaths.

Meat-eating increased direct hazards not widely experienced by the herbivorous great apes: increased tissue toxins and infectious pathogens5 (Table 6.5). Potential toxins from meat that are scarce in plants include cholesterol; iron and copper, from hemoglobin and myoglobin (both present in all vertebrate tissues); and phytanic acid in ungulate tissues. Infectious pathogens are unavoidable in eating carrion. Wild mammals and birds carry prions, viruses, bacteria, bloodborne protozoans, and nematodes. Genomic analysis shows that the domestic tapeworm Taenia infested Homo as a host 0.8–1.7 MYA (Hoberg, 2002). The controlled use of fire, possibly before 0.5 MYA (Goren-Inbar et al, 2004; Wrangham, 2007), may have been important in pathogen control by cooking or smoking of meat. However, some pathogens are not killed by ordinary cooking; e.g., infectious prions can survive autoclaving at >120°C (Taylor, 1999).

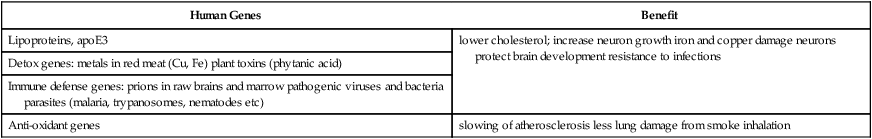

TABLE 6.5

Categories of Meat-Adaptive Gene Candidates

| Human Genes | Benefit |

| Lipoproteins, apoE3 | lower cholesterol; increase neuron growth iron and copper damage neurons protect brain development resistance to infections |

| Detox genes: metals in red meat (Cu, Fe) plant toxins (phytanic acid) | |

| Immune defense genes: prions in raw brains and marrow pathogenic viruses and bacteria parasites (malaria, trypanosomes, nematodes etc) | |

| Anti-oxidant genes | slowing of atherosclerosis less lung damage from smoke inhalation |

Fire and cooking increase exposure to smoke, which must have been intense in the early cave dwellings, as well as in semi-permanent structures. In pre-industrial societies, open fires were used for warmth and insect control, as well as for cooking. Smoke inhalation causes lung damage with consequences to the level of aerobic activity that can be sustained and cardiovascular functions (Chapter 2). Moreover, the process of cooking and charring produces glyco-oxidation products (AGEs) that are proinflammatory (Section 2.4.2) (Vlassara et al, 2002). Fire is inflammatory, no pun meant. Each of these exposures may have selected for new gene variants not needed in the herbivorous apes.

The butchering and handling of carrion also bring hazards separate from ingestion. The Foré of New Guinea once suffered from the neurodegenerative disease kuru, a spongioform encephalopathy, acquired by women who handled raw brains of the recently deceased (Mead et al, 2003). The infectious agent in kuru is the prion, which causes the spongiform encephalopathies Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in humans and of scrapie in herd animals (Liberski and Gajdusek, 1997; Prusiner and Hsiao, 1994).

The abundant bones in Paleolithic sites also imply extended human occupancy, which would increase exposure to infectious agents in carrion and human feces, and the insects attracted. In contrast, as discussed above, the great apes rarely occupy the same site for more than a day. The increased exposure to animal fat, new food toxins, and diverse pathogens in feces thus defines a new phase in the evolution of both lipoprotein metabolism and of host defense mechanisms.

Humans differ from the great apes in several lipoproteins that are candidates for meat-adaptive genes (Table 6.5) (Fig. 6.5B). The best case may be the cholesterol carrier apolipoprotein E (apoE), which is a regulator of blood cholesterol in reverse cholesterol transport (Section 5.7). ApoE also transports cholesterol for steroid synthesis and neuronal outgrowth. The main human variants, apoE3 and apoE4, differ in one amino acid (R112C) that alters lipid binding affinity and subcellular processing (Ji et al, 2006; Mahley and Rall, 2000) (Table 6.6). The apoE4 isoform was first identified in association with elevated cholesterol (Section 5.7.3).

TABLE 6.6

Gene Candidates for Resistance to Disease Associated with Meat-Eating

| Animal Organ Component | Main Source | Disease Risk | Gene Candidate (note) |

| cholesterol unsaturated fatty acids | brain, fat, marrow, muscle | cognitive decline during aging; traumatic brain injury; Alzheimer disease; vascular disease | apoE4a apoE4b apoE4c apoE4d; Lp(a)f |

| infectious agents: viruses |

dysenteries, hepatitis | apoEe CMAHg HLAh |

|

| prions | bone marrow, brain, | spongiform | apoE3e, HLAh |

| viscera | encephalopathies | Prpi | |

| bacteria | viscera | cholera and dysenteries | CFTRj |

| apoE3e | |||

| HLAh | |||

| amoeba protozoa | dysenteries | ||

| malaria | Hbk, apoEe | ||

| nematodes | HLAh | ||

| metals: | red meat, blood | vascular disease | ?l |

| copper, iron, zinc | Alzheimer disease? | ||

| phytanic acid | fish, ungulates, dairy | Refsum’s disease, prostate cancer | PHYHm |

Table directly from (Finch and Stanford, 2004).

aApoE4 also increases the risk of early Alzheimer disease (Section 5.7.3 text and references).

bTraumatic brain injury and hemorrhagic stroke have worse outcomes in E4 carriers, with more memory impairments (Crawford et al, 2002; Liberman et al, 2002).

cApoE4 decreases cerebral glucose utilization during middle age and accelerates cognitive decline.

dApoE4 increases risk of heart attack by 40% and accelerates atherosclerosis (Section 5.7.3, text and references). Because apoE4 versus E3 carriers show more decrease of blood cholesterol in response to reductions of dietary fat and cholesterol, at least in the case of obese diabetics (Fig. 5.16) (Saito, 2004), they may be more sensitive to hypercholesterolemia on fatty diets.

eApoE3 increases liver damage to hepatitis C and may protect brain development from impairments in children with diarrhea (Section 5.7.5, text and references). Prion diseases have not shown consistent associations with apoE alleles.

fBlood Lp(a) elevations are a mild risk factor in heart disease, up to 2-fold (Seed, 2001; Sharrett, 2001). Human Lp(a) levels vary >1000-fold between individuals under genetic control (Boerwinkle et al, 1992).

gCMAH [CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid (CMP-Neu5Ac) hydroxylase] is an enzyme that modifies CMP-neu5Ac (N-acetylneuraminic acid) to the hydroxylated CMP-NeuGc (N-glycolylneuraminic acid). CMAH and NeuGc are found in anthropoids but not humans (Chou, 2002; Crocker, 2001; Varki, 2001). The CMAH gene in humans was inactivated by deletion of exon 6 about 3.2 MYA (Hayakawa, 2006). Siglec-4a in myelin-associated glycoprotein shows species differences pertinent to white matter diseases such as multiple sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

hHLA-B27 allele is associated with reactive arthritis induced by diverse infections (Urvater, 2000). Reactive arthritis after enteric infections with bacteria is associated with Mhc haplotypes in gorillas and macaques (Finch and Stanford, 2004, Appendix).

HLA-DQ7 is 75% less frequent in those with vCJD than normals (Jackson et al, 2001). Onchocerca volvulus, the nematode parasite that causes river blindness, is endemic in West Africa. HLA-DQ variants influence outcomes of infection (Meyer et al, 1994; Meyer et al, 1996); one haplotype associated with more severe disease in West Africa shows less malaria (Hill et al, 1991), implying balancing selection (Meyer et al, 1996).

iThe prion gene PrPc influences transmission of infectious prions PrPsc between species and the age of disease onset (Prusiner and Hsiao, 1994; Prusiner et al, 1999; Telling et al, 1996). Primates are relatively vulnerable to prion infections (Schatzl et al, 1995). The human PrPc gene evolved two polymorphisms about 0.2 MYA ago that increase resistance to infection in heterozygotes (Mead, 2003).

jCFTR (cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator) heterozygotes may be resistant to diarrhea from cholera and other dehydrating diseases transmitted by intestinal bacteria, as shown in a mouse model (Gabriel, 1994; Kirk, 2000).

kResistance to malaria from Plasmodium falciparum is mediated by variants of hemoglobin that cause sickle cell anemia; milder forms in heterozygotes are maintained by balancing selection. Variants in G6PDH and HLA genes (note h) confer relative resistance to malaria may have spread in association with agriculture (Hill et al, 1997; Rich et al, 1998).

lMuscle contains iron, copper, zinc, and other divalent metal ions, which are implicated in Alzheimer and vascular disease and infections (Bush and Tanzi, 2002; Finch and Stanford, 2004, Appendix). Trace metals enhance Aβ aggregation (Huang, 2004). In the presence of soluble copper (Cu2+), apoE4 enhances Aß aggregation relative to apoE3 (Bush and Tanzi, 2002). An iron-responsive element resides in the UTR of the amyloid precursor protein RNA transcript, which may have a role in APP metabolism (Rogers, 2002). The Aß peptide binds iron directly; the rodent amino acid differences from human and primate decrease iron binding and the chemical production of H2O2 (Boyd-Kimball et al, 2004). Because most plant sources have low metal concentrations, transitions to meat-eating would have sharply increased iron intake. Diet also influences metal bioavailability; e.g., iron absorption is inhibited by plant-derived phytase and tannins that bind free iron, whereas absorption is enhanced by vitamin C (Haddad et al, 1999). No chimp-human differences are known in iron transport proteins.

mHumans have higher expression of an enzyme PHYH (phyantol CoA hydroxylase) that degrades phytanic acid, a branched chain fatty acid derived from fish and ungulate meat and milk products, which are rarely eaten by the great apes. Phytanic acid is absent from carnivores, eggs, and plants, although derived from chlorophyll (van den Brink, 2006). PHYH expression was higher in human than chimp (fibroblast gene expression profiling) (Karaman et al, 2003). Phytanic acid elevations in blood are associated Refsun’s disease, a peripheral neuropathy, and possibly with prostate cancer (van den Brink et al, 2006; Xu et al, 2005).

Human apoE alleles evolved in two critical stages (Fullerton et al, 2000) (Fig. 6.6). In modern populations, apoE3 is the most prevalent allele (>50% in all populations; Fig. 5.15) and, relative to apoE4, increases life expectancy by up to 6 y (Fig. 5.12). ApoE3 also reduces age-related frailty from heart attacks, cognitive decline, and Alzheimer disease. During middle-age, apoE3 carriers have higher frontal cortex glucose metabolism and report less use or need of memnonics in daily activities. ApoE3 carriers have better recovery from head injury and may have higher bone density, which would protect against traumas in hunting and fighting, and age-related osteoporosis (Section 5.7.3). These anti-frailty effects of apoE3 would also have favored health in middle age and later. Middle-aged and older humans have unique roles in multi-generational care giving and mentoring (Gurven et al, 2006), including the grandmothering unique to humans (Hawkes et al, 1998; Packer et al, 1998; Robson et al, 2006).

ApoE isoforms also differ in effect on amyloid aggregation (Aβ peptide). In the presence of soluble copper (Cu2+), apoE4 enhances Aβ aggregation relative to apoE3 (Bush and Tanzi, 2002). This interaction could promote amyloid degenerative processes from meat-eating, which introduces surges of copper, iron, and other metals at each meal. Even trace levels of copper in the drinking water increased Aβ deposits in animal models (Sparks et al, 2006b). Moreover, the Aβ peptide directly binds iron, which increases cytotoxic H2O2 production (bystander effect, Section 1.4.1), while the amyloid precursor protein (APP) transcript also has an iron-binding regulatory site (Rogers et al, 2002). The high metal content of senile plaques (copper, iron, and zinc are 2- to 5-fold above healthy brain neuropil) (Lovell et al, 1998) is implicated in the association of oxidative damage and amyloid burden (Bush and Tanzi, 2002). Other aspects of metal ingestion are described in Table 6.6, note I.

By DNA sequence analysis, apoE3 arose from a single point mutation in apoE4 and spread 0.226 MYA (Fullerton et al, 2000), just before the first fossil of H. sapiens. The ‘bad’ E4 allele was thus the ancestral human gene (Fig. 6.6) (Hanlon and Rubinsztein, 1995; Mahley, 1988). The dating estimates of apoE3 (0.176–0.579 MYA) partly overlap with H. erectus (0.3–1.6 MYA), which allows the possibility that H. neanderthalensis shared apoE3 with H. sapiens (Section 6.2.1). The subpopulation of H. sapiens from which apoE3 spread could have been African or Eurasian (this is not in conflict with an East African origin of modern H. sapiens). The great apes have a further functional base difference from the H. sapiens gene (T61R) (Fig. 6.6). This substitution is predicted to alter peptide folding, resulting in lipid binding functions like the modern human apoE3; these differences are modeled in a transgenic mouse apoE4 (Dong et al, 1994; Raffai et al, 2001). The great apes have other scattered base differences from human apoE (Table 6.7), which, by their location and effect on coding, are not predicted to influence peptide folding or lipid binding.

TABLE 6.7

Apolipoprotein E: Polymorphisms in Humans and Species Differences

| ApoE residue1 (+signal peptide) | 612 (79) | 1123 (130) | 1352 (153) | 1583 (176) |

| human: apoE2 | R | C | V | C |

| apoE3 | R | C | V | R |

| apoE4 | R | R | V | R |

| Chimp | T | R | A | R |

| Gorilla | T | R | A | R |

| Orangutan | T | R | A | R |

1Amino acid residues numbered positions of the polymorphisms in the mature plasma protein, as used in this text and in (Finch and Sapolsky, 1999). The other numbering system includes the ‘+ signal peptide’ of the full protein sequence (the 18 residue signal peptide is cleaved before secretion by the liver into the blood): data from National Center for Biotechnology (NCBI) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez). Table directly taken from (Finch and Stanford, 2004, Table 5).

2Residue 61 strongly affects apoE structure through ‘domain interactions’ and is an important cause of species variations (Dong et al, 1994; Raffai et al, 2001). Chimpazee apoE with T61 is predicted to function in lipid binding like human apoE3, despite the R112 and R158 as in human apoE4.

3Bolded residues identify the functionally important differences in the human alleles.

The single mutation leading to the ancestral apoE4 may have spread as a pathogen resistance factor. (Finch and Stanford 2004). ApoE4 carriers have less liver fibrosis during hepatitis C viral infections and maybe better cognitive development in children with enteric infections (Section 5.7.4). ApoE alleles also influence HDL remodeling during the acute phase response (Section 1.5.4). Acute phase lipid remodeling increases plasma triglycerides and other lipid energy resources needed in host defense, but also decreases the anti-oxidant activities of HDL. In a biochemical experiment, apoE4 caused greater release of serum amyloid A (SAA) from HDL (Miida et al, 2006), which, in turn, would increase uptake of cholesterol by macrophages, a key step in atherogenesis (Section 1.5). Thus, apoE4 by altering acute phase HDL remodeling would tend to promote vascular disease over longer durations in an infectious environment. ApoE also has a direct role in immunity in the presentation of lipophilic antigens (vander Elzen et al, 2005) (Section 5.7.5). These and other observations support the Charlesworth-Martin hypothesis (Charlesworth, 1996; Martin, 1999) that apoE4 is maintained in human populations by balancing selection. We may also see how the evolution of longevity has involved selection for genes that influence oxidative damage from inflammation and infection (Queries II, III, and IV; Chapter 1).

Two other lipoprotein system genes differ between humans and chimps. The Lp(a) lipoprotein gene promoter differs between humans and chimps with strong effects on plasma levels of Lp(a), an LDL-like protein with links to thrombosis and vascular events though Lp(a) binding sites to fibrin in the clotting system (Belczewski et al, 2005; Doucet et al, 1994; Doucet et al, 1998). Chimpanzees typically have high plasma Lp(a), 2–4-fold above the human norm. In one colony, a majority of animals had plasma Lp(a) levels above a clinical threshold for cardiovascular risk (Doucet et al, 1994). The Lp(a) promoter has three nucleotide differences between chimp and human (Huby et al, 2001). Of unknown functional significance, the LDR-receptor gene of humans has an unusual Alu repetitive element in the 3’ untranslated mRNA not found in great apes, possibly from a rare gene conversion event (Kass et al, 1995; Kass et al, 2004).

Increased resistance to infections must have been a major importance to the reduction of mortality and increased life expectancy. Many gene candidates may be considered that influence resistance to infections transmitted by raw organs (Finch and Stanford, 2004). The prion diseases causing spongiform encephalopathies are particularly interesting examples and include ‘mad cow’ disease, first recognized in humans as kuru in New Guinea traditionalists (Foré) who handled and ate the brains of recently deceased relatives (Liberski and Gajdusek, 1997; Prusiner and Hsiao, 1994). Prion transmission is decreased by heterozygosity at the Prp locus 129M/V, which encodes the prion protein (Prusiner, 1999; Mead et al, 2003). Older Foré survivors of kuru are predominantly PRNP 129 heterozygotes, while homozygotes are more common in the younger generation (Mead et al, 2003). Homozygosity (M/M) also increases the risk of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (Lucotte and Mercier, 2005; Mitrova et al, 2005). Prion alleles differ widely in human populations and are in linkage disequilibrium, suggesting that balancing selection was associated with cannibalism, which was only recently suppressed. Chimp and human prion genes differ in six sites. The modern prion alleles may be dated to 0.5 MYA (Mead et al, 2003), which approximates the use of spears in organized hunting (Section 6.2.2). Contact with raw brains is not limited to cannibalism. Animal brains are considered a delicacy by many traditional peoples (Table 6.4, footnote e). Also recall that brain and marrow were extracted by early humans. Moreover, raw brains have been widely used for curing hides.

The sialic acids on cell membranes have major importance to pathogen resistance as sites for binding of viruses and bacteria (Angata and Varki, 2002; Varki, 2001). CMAH encodes an enzyme that modifies the sialic acid Neu5Gc (Table 6.6, note g). CMAH and NeuGc are found in other anthropoids but not in modern humans or Neanderthals (Chou et al, 2002). The CMAH gene in humans was inactivated by deletion of exon 6 about 3.2 MYA (Hayakawa et al, 2006), which predates the genus Homo and may have occurred in an Australopithicene (Fig. 6.5). Sialic acid binding immunoglobulins (SIGLECs) have also evolved differences from chimpanzees of potential importance in host resistance. SIGLEC11 is expressed in human brain microglia but not in chimp or orangutan microglia (Hayakawa et al, 2005). Siglec-1 sequence differences may account for differences in tissue distribution of macrophages, e.g., chimps have higher titers of blood macrophages and fewer myeloid precursors in marrow than humans (Varki, 2001).

The evolved absence of Neu5Gc could increase resistance to rotoviruses, which cause diarrhea, and influenza viruses, both of which bind to Neu5Gc (Angata and Varki, 2002; Delorme et al, 2001). Children are especially susceptible to mortality from diarrhea (Fig. 4.2, Section 4.6). The absence of Neu5Gc could have also favored the later human cohabitation with domestic animals which are major reservoirs of pathogens.

Lactose tolerance was also evolved in association with the domestication of cattle and the increased use of milk as an adult food. Lactose, the main carbohydrate in milk, is hydrolyzed by intestinal lactase, which is universally expressed on intestinal enterocytes during early life (Swallow, 2003). However, lactose expression is transcriptionally suppressed in most populations before age 10. The resulting adult lactose intolerance typically causes diarrhea. Lactose tolerance, however, has arisen through at least four mutations in lactase gene promoter that arose independently in association with pastoralism during the past 9000 y (Tishkoff et al, 2006; Coelho et al, 2005). The spread of adult lactose tolerance is attributed to two factors: the benefit of milk as a new high energy food source for adults and the reduction of diarrhea as a side effect. Besides the recognized danger of dehydration from diarrhea in hot climates, diarrhea also increases the local exposure to enteric pathogens.

The HLA system variants are also candidates for evolution of host resistance. This extraordinary complex cluster of a thousand genes (Section 1.3.2) modulates many aspects of antigen presentation to immune cells and includes cytokine and complement system genes. HLA haplotypes (combinations of alleles at different loci) are highly conserved, and some are shared with chimpanzees (O’Huigin et al, 2000; Venditti et al, 1996). Some class HLA I genes are more diverse in humans than chimps (Adams et al, 2001). HLA-DQ variants modulate responses to infections (Table 6.6, note h). The persistence of these ancient haplotypes is attributed to balancing selection, but the pathogens or environmental factors are not known.

Smoke inhalation from domestic fire causes lung damage, as noted above. Genes that increase resistance to smoke inhalation could include catalase, SOD, and other anti-oxidant genes, with increased expression (Cutler, 2005; Lopez-Torres et al, 1993). Recall that transgenic overexpression of SOD that decreases bystander damage to lung by fly-ash (Section 1.4.1) (Ghio et al, 2002b) and of transgenic catalase that increases mouse life span and delays atherosclerosis (Section 1.2.6) (Schriner et al, 2005; Yang, 2004a). Other candidates for resistance to inflammogens may be found in xenobiotic detoxifying enzymes, e.g., glutathione-S-transferase M1, which makes the key anti-oxidant glutathione (Fig. 1.11). The proinflammatory AGEs that are produced by cooking and charring may also be decreased enzymatically by amidoriases (‘AGE-breakers’) (Monnier and Sell, 2006) (Sections 1.2.6 and 2.4.2). On the other hand, AGEs may have been served as olfactory cues to tell when tubers were sufficiently cooked to destroy toxins (de Bry, 1994).

A further phase of ‘meat-adaptation’ occurred during the emergence of semi-permanent or seasonal assemblages which introduced new pressures on immune defenses and detoxification, and benefits of new hygienic behaviors. By 42,000 YBP, modern humans had reached the East European Plain (Don River site in Russia) (Anikovich et al, 2007). Caves, huts, and tents would have increased the exposure to infection and inflammation through carrion, excreta, garbage, and smoke from indoor fires. Hygiene must have been problematic with increasing population density, especially children in ‘sphincter’ training. Recall from above that the great apes have much lower exposure to biotrophic excreta; their night groups in close contact are usually small, 20 adults or less, wherein only mother and child sleep together. Because of vulnerability of the youngest to infections, it would be interesting to compare the proportions of infants and children per group in great apes and pre-industrial human communities and the prevalence of infections.

This putative phase of increased exposure to infections and inflammogens may coincide with the gradual reduction of human body size after 50,000 YBP (Fig. 6.7) (Ruff et al, 1997). Most agree that early anatomically modern H. sapiens were about 15% larger than current global averages (Kappelman, 1997). I hypothesize that this down-shift of size is due at least in part to the increasing load of infection and inflammation during transitions to sedentism with increasing population density. In modern populations, infections in early life attenuate growth, even when food is plentiful (Chapter 4). Exposure to infection and inflammation gradually increased with the beginning of the first high density permanent settlements (‘towns’) as the last Ice-Age ended. In the Jordan Valley, Natufian stone dwellings in semi-permanent or permanent settlements are dated from 13,000 YBP, before the domestication of crops and animals, and before pottery (Belfer-Cohen, 1991).

The Natufian culture shows progressive separation of garbage from inside the living and cooking space to designated middens (Hardy-Smith and Edwards, 2004). By the end of the Pre-pottery Neolithic B phase, 8000 YBP, interior living spaces were very clean, evidenced by sweeping and plastering (archeological sites of Beidha and Wadi El-Hammeh 27). Other important findings come from excavations at Çatalhöyük, a major town on the Anatolian plateau inhabited from 9500 to 8000 YBP, after the beginnings of crop domestication. Extensive findings by the Hodder team are summarized as interim reports (Hodder, 2005, 2006). Of great interest to our discussion are the hundreds of contiguous apartments that had definitive clean and dirty areas. Adjacent middens held diverse species of bones (Yeomans, 2005). Moreover, there is evidence for human feces in these middens from bile acid residues with human biochemical signatures of deoxycholate and lithocholate (Bull et al, 2005). The novel behavior of separating garbage and feces from the living spaces can be designated as ‘urban proto-hygienic’ and implies some understanding that infectious disease is linked to hygiene.

Despite the separation of clean and dirty spaces in the early Levantine towns, there were limits in clean living. Rodent infestations are evident, and insect swarms may be supposed. Inside smoke was dense in the apartments of Çatalhöyük, which vented smoke from the fireplaces through the access port on the roof of each unit. The skeletons of older adults buried within these apartments have sooty particulate deposits on the inside surfaces of upper ribs, presumably left by the drying lung tissue (Hodder 2006; Andrews et al, 2005; Molleson et al, 2005). The extent of the deposits suggests pulmonary impairments (anthracosis) (Birch, 2005), like ‘hut-lung’ disease (Section 2.4.1). A high burden of infection and inflammation is indicated by the excess of infants in the burials and by bone and dental evidence for slow growth and small adult size (men 1.63 m, women 1.54 m) (Molleson et al, 2005). DNA from skeletons in Çatalhöyük is being recovered and might be evaluatable for inflammatory gene allelic diversity (Sections 1.3.2 and 5.7.2).

Diffusion of hygienic concepts was slow and irregular. Other pre-industrial traditional people, Northwest Indians, for example, in the 18th Century did not exclude garbage from their living spaces (Hardy-Smith and Edwards, 2004, p. 284). In Roman cities, the toilet was typically located in the kitchen. Contact with human and animal excreta was unavoidable in rural and urban European households until recently, e.g., many traditional farm houses held animals on the ground floor with the family floor just above the manure (Barnes et al, 2006; Wright, 1960; George, 1984).

The domestication of mammals and birds would have created new reservoirs for disease and modes of transmission in all directions (Pearce-Duvet, 2006). Taeniid tapeworms, which have infested humans since 0.8 MYA or before (Hoberg, 2002), were evidently transmitted to cattle, dogs, and pigs during domestication 5,000–10,000 YBP. The three domestic Taenia species are derived from a common ancestor in Africa or Eurasia according to genomic data 0.78–1.81 MYB and may be the oldest parasite specific to the genus Homo. Malaria (Plasmodium falciparum) may also have preceded domestication (Pearce-Duvet, 2006), challenging the attractive hypothesis that domestication of fowl introduced malaria through host switching (Hill et al, 1997; Rich et al, 1998). Chimpanzees carry P. reichenowi, which is much closer to P. falciparum than the avian plasmodia (Waters et al, 1991; Waters et al, 1993). Expansions of agriculture are associated with the speciation of Anopheles mosquitoes in Africa (Pearce-Duvet, 2006). The strong associations of malaria with agricultural areas is hypothesized to have favored the spread of the sickle cell hemoglobin gene and the numerous other mutant hemoglobins by balancing selection (Hill et al, 1997; Livingstone, 1985; Pearce-Duvet, 2006; Rich et al, 1998). The many cystic fibrosis CFTR mutants may also be maintained by balancing selection (Table 6.6, note j). Cystic fibrosis causes abnormal mucus accumulation in intestine, lung, and skin that impair breathing, digestion, and sweating. CFTR mutants are common recessives in Caucasian populations (3–10%) and arise as independent mutations at many sites (Mateu et al, 2001; Mateu et al, 2002). The normal allele encodes a chloride (Cl–) channel, activated by bacterial enterotoxins. Hypothesized heterozygote advantages include reduced sweating, which might attract fewer mosquitoes, and decreased dehydration from diarrheal disease or from sweating in hot climates; however, supporting evidence is modest (Quinton, 1994). The spread of agriculture has had huge effects on human pathogen exposure through host reservoirs in flocks and herds that also increase transfer from feral populations (Pearce-Duvet, 2006). Thus, permanent settlements and the ‘agricultural revolution’ would have brought a further major increase in the burdens of chronic infection and inflammation.

Brain evolution also sharply accelerated in the genus Homo after 1.0 MYA concurrently with the record of increasingly sophisticated hunting tools and butchering. Brain evolution was crucial to the evolution of meat-eating; we may consider as ‘meat-adaptive’ the genes that enabled further brain developments (Finch and Stanford, 2004). A survey of genes expressed in the most rapidly evolving brain regions (human accelerated regions, HARs) identified a novel gene sequence in HARF1 that evolved >1 MYA; this non-coding RNA is expressed in Cajal-Retzius neurons during cortical development (Pollard et al, 2006). White matter (myelinated pathways) increases also evolved during human cortex enlargement. The density of myelinated neuronal connections increased disproportionately relative to the great apes (Schoenemann et al, 2005), which enables high-speed exchanges between higher cortical centers that are critical to complex social decisions, as well as to spear throwing. The apoE3 allele favors slower myelin deterioration (Bartzokis et al, 2006), among other examples of apoE3 in delaying cognitive aging noted just above and discussed in Section 5.7.3. The increasing importance of older individuals to the uniquely human multi-generational care giving and mentoring not found in the great apes would be favored by healthier brains later in life with greater ‘cognitive reserve’ (Allen et al, 2005).

The spread of the apoE3 allele during the final stages of brain size increases (ca. 0.226 MYA) might have contributed to brain development as well as to cognitive functions later in life (Finch and Stanford, 2004). Besides its role in peripheral cholesterol metabolism, apoE transports cholesterol to growing neurons. Transgenic mice with targeted replacement of the mouse apoE gene with the human shows that apoE3 and E4 alter synaptic development. Neurons in apoE3 mice are more complex (dendritic arborization) and have more excitatory synaptic transmission than apoE4 mice (Wang et al, 2005a). Similar effects of apoE4 in human brain development are not yet documented but could be consistent with differences at later ages: non-demented E4 carriers had lower frontal cortex glucose metabolism (Reiman et al, 2005; Small et al, 2000) and more cortical synapses (Ji et al, 2003) (Section 5.7.4). Great care is needed in interpreting these data, which could be promiscuously used to support eugenic ideologies.

FOXP2 is another brain evolution candidate gene. This transcription factor of the FOXO gene family, which includes DAF-16, is expressed in neurons of brain regions that mediate language in humans and song in birds (Scharff and Haesler, 2005). FOXP2 acquired two mutations about 0.2 MYA (Enard, 2002), diverging from the highly conserved sequence in mammals. Because of rare familial mutations that cause speech abnormalities, the mutations of 0.2 MYA that approximate the earliest modern H. sapiens suggest a role of FOXP2 in human language capacity.

Two other genes expressed in the brain have variants that evolved and spread very recently. Variants of MCPH1 (Microcephalin) and ASPM (abnormal spindle-like microcephaly associated) most likely arose <50,000 YBP, long after the initial emigration from Africa (Evans et al, 2005b; Mekel-Bobrov et al, 2005). The ASPMD variant may be 6,000 years old, approximating the spread of cities and agriculture. Rare mutations in either gene impair brain size development, but it is not known if the common alleles, which differ across populations, influence cognition or behavior. There is debate about the role of selection in the spread of these variants, but the timing of spread is accepted as Neolithic (Currat et al, 2006).

6.2.5 The Increase in Life Expectancy

When did life expectancy of human ancestors begin to increase above the great ape baseline of 15–20 y? This inquiry does not assume that changes in life expectancy were linear or always progressive. In animals, life span can increase or decrease within 10––5 generations in response to predation or artificial selection (Section 1.2.8). One may start with the dental evidence for demographic shifts during the Middle to Upper Paleolithic (Pleistocene) (Caspari, 2004; Caspari and Lee, 2006). Younger and older adults may be distinguished by tooth wear and presence of adult molars (M3) that erupt at the end of the juvenile period. The Upper Paleolithic sample of modern H. sapiens 30,000 YBP in Europe had a ratio of old:young adults of 2.1, which was significantly higher than the <0.4 of old: young ratio for Middle Paleolithic ‘early modern’ H. sapiens in West Asia, Neandertal, other earlier Homo, and Australopithecus. Caspari and Lee (2006) suggest that the increased life expectancy implied by the 30,000 YBP European samples represents cultural developments after arrival from Africa and West Asia. Of course, paleodemographic estimates are problematic because of the incompleteness of age-group samples and uncertainties in age assignments based on wear (Hawkes and O’Connell, 2005; Skinner and Wood, 2006; Konigsberg, 2006; Hoppa and Vaupel, 2002). While this dental or skeletal evidence is not sufficient for estimating adult life expectancies, The Caspari-Lee analysis indicates that major increases in survival to adult ages occurred relatively recently in the Upper Paleolithic.

Two further arguments may be considered, both of which depend on the evolving size and suggest prior increases in life expectancy. First, larger animals tend to have slower development and to live longer as described by allometric relationships (Sacher, 1977; Calder, 1984; Finch, 1990, pp. 267–271; Charnov, 1993; Hawkes and Paine, 2006). Australopithecenes and other early hominids before 2 MYA were in the upper size range of chimpanzees, 20–40 kg (Skinner and Wood, 2006) (Table 6.1), implying modestly longer life spans (Fig. 6.2B). The genus Homo rose above this range with H. habilis (46 kg) and H. erectus (61 kg), followed by H. heidelbergensis 71 kg) and H. sapiens (64 kg). The range of uncertainty in adult sizes (Table 6.1, footnote e) precludes calculation of life span increases from allometric formulae.

As another approach, consider the possibility that life expectancy increased concurrently with the increase of brain size and the social cooperation. While social cooperation has been emphasized in relation to hunting (also seen in chimpanzees), three uniquely human behaviors are cogent to the evolution of mortality rates, and of life expectancies (summarized from Section 6.2):

1. All societies have multi-generational caregiving of mothers and their young children.

2. Human birth is almost always assisted, unlike that of the great apes. Humans have many difficulties in labor because of the larger human head size (Abitbol, 1996a,b; Ruff, 1995; Trevathan and Rosenberg, 2000; Rosenberg and Travathan, 2002).

3. Weaning is much earlier than in the great apes (Fig. 6.4). Across pre-industrial societies, the 2.5 y average age at weaning is several years earlier than in chimpanzees (4–6 y) or orangutans (7–8 y) (Sellen, 2006; Kennedy, 2005).