Perceptual Set

To see is to believe. As we less fully appreciate, to believe is to see. Through experience, we come to expect certain results. Those expectations may give us a perceptual set, a set of mental tendencies and assumptions that affects, top-down, what we hear, taste, feel, and see.

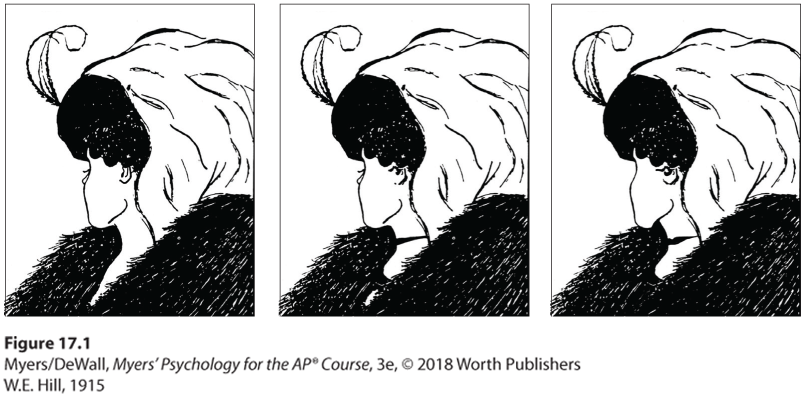

Consider: Is the center image in Figure 17.1 an old or young woman? What we see in such a drawing can be influenced by first looking at either of the two unambiguous versions (Boring, 1930). Likewise, in the figure below Figure 17.1: Reading from left to right, our expectations cause us to perceive the middle script differently than when reading from top to bottom.

Figure 17.1 Perceptual set

Show a friend either the left or right image. Then show the center image and ask, “What do you see?” Whether your friend reports seeing an old woman’s face or young woman’s profile may depend on which of the other two drawings was viewed first. In each of those images, the meaning is clear, and it will establish perceptual expectations.

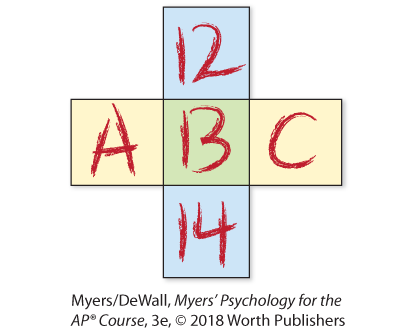

Everyday examples abound of perceptual set—of “mind over mind.” In 1972, a British newspaper published unretouched photographs of a “monster” in Scotland’s Loch Ness—“the most amazing pictures ever taken,” stated the paper. If this information creates in you the same expectations it did in most of the paper’s readers, you, too, will see the monster in a similar photo in Figure 17.2. But when a skeptical researcher approached the original photos with different expectations, he saw a curved tree limb—as had others the day that photo was shot (Campbell, 1986). With this different perceptual set, you may now notice that the object is floating motionless, with ripples outward in all directions—hardly what we would expect of a swimming monster.

Figure 17.2 Believing is seeing

What do you perceive? Is this Nessie, the Loch Ness monster, or a log?

To believe is also to hear. Consider the kindly airline pilot who, on a takeoff run, looked over at his sad co-pilot and said, “Cheer up.” Expecting to hear the usual “Gear up,” the co-pilot promptly raised the wheels—before they left the ground (Reason & Mycielska, 1982). The context of spoken words will determine whether you hear “the stuffy nose” or “the stuff he knows.” And depending on your perceptual set, the weather-forecasting “meteorologist” may become a muscular kidney specialist—your “meaty urologist.” Music lovers have recorded thousands of mishearings at kissthisguy.com, a website named for Jimi Hendrix’s oft-misheard phrase “kiss the sky.”

Or consider this odd question: If you said one thing but heard yourself saying another, what would you think you said? To find out, a clever Swedish research team invited people to name a font color, such as saying “gray” when the word green was presented in a gray font (Lind et al., 2014). While the participants heard themselves speaking over a noise-cancelling headset, the experimenters occasionally substituted the participant’s own previously recorded voice, such as saying “green” instead of “gray.” Surprisingly, people usually missed the switch—and experienced the inserted word as self-produced. What they heard controlled their perception of what they had just said.

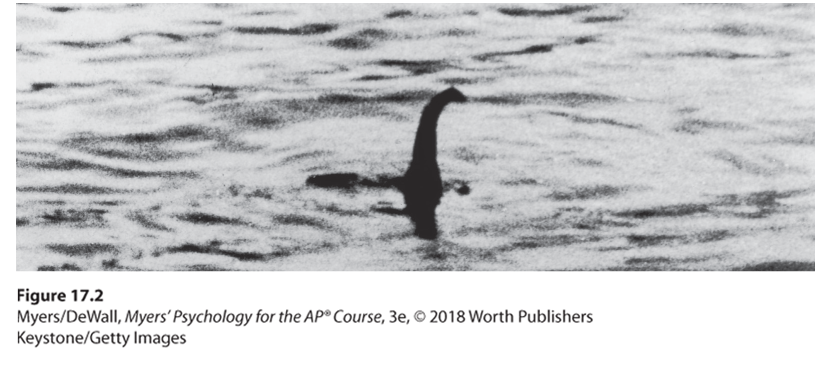

Perceptual set at work.

Our expectations can also influence our taste perceptions. In one experiment, preschool children, by a 6-to-1 margin, thought french fries tasted better when served in a McDonald’s bag rather than a plain white bag (Robinson et al., 2007). Another experiment invited campus bar patrons at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to sample free beer (Lee et al., 2006). When researchers added a few drops of vinegar to a brand-name beer and called it “MIT brew,” the tasters preferred it—unless they had been told they were drinking vinegar-laced beer. In that case, they expected, and usually experienced, a worse taste.

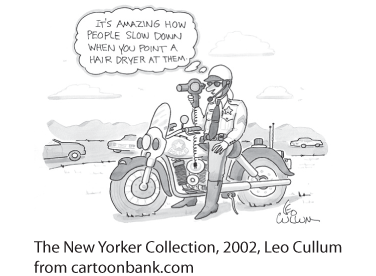

There

Are Two

Errors in The

The Title Of

This Book

Book by Robert M. Martin, 2011

Did you perceive what you expected in this title—and miss the errors? If you are still puzzled, see the explanation below.1

What determines our perceptual set? As Module 47 will explain, through experience we form concepts, or schemas, that organize and interpret unfamiliar information. Our preexisting schemas for monsters and tree trunks influence how we apply top-down processing to interpret ambiguous sensations.

In everyday life, stereotypes about gender (another instance of perceptual set) can color perception. Without the obvious cues of pink or blue, people will struggle over whether to call the new baby “he” or “she.” But told an infant is “David,” people (especially children) have perceived “him” as bigger and stronger than when the same infant was called “Diana” (Stern & Karraker, 1989). Some differences, it seems, exist merely in the eyes of their beholders.

Context, Motivation, and Emotion

Perceptual set influences how we interpret stimuli. But our immediate context, and the motivation and emotion we bring to a situation, also affect our interpretations.

Context

Social psychologist Lee Ross invited us to recall our own perceptions in different contexts: “Ever notice that when you’re driving you hate pedestrians, the way they saunter through the crosswalk, almost daring you to hit them, but when you’re walking you hate drivers?” (Jaffe, 2004).

Some other examples of the power of context:

- When holding a gun, people become more likely to perceive another person as also gun-toting—a phenomenon that has led to the shooting of some unarmed people who were actually holding their phone or wallet (Witt & Brockmole, 2012).

- Imagine hearing a noise interrupted by the words “eel is on the wagon.” Likely, you would actually perceive the first word as wheel. Given “eel is on the orange,” you would more likely hear peel. In each case, the context creates an expectation that, top-down, influences our perception of a previously heard phrase (Grossberg, 1995).

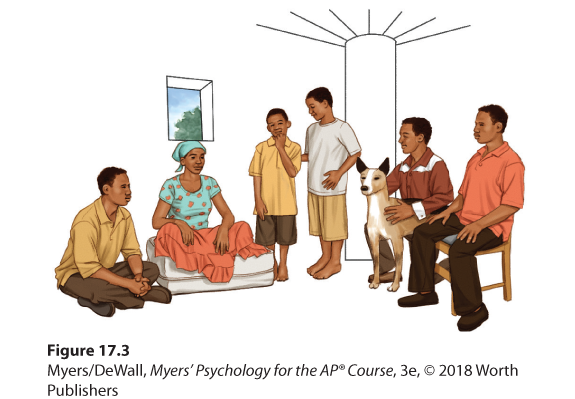

- Cultural context helps inform our perceptions, so it’s not surprising that people from different cultures view things differently, as in Figure 17.3.

- How tall is the shorter player in Figure 17.4?

- And how is the woman in Figure 17.5 feeling? The context provided in Figure 17.6 will leave no doubt.

Figure 17.3 Culture and context effects

What is above the woman’s head? In one classic study, most rural East Africans questioned said the woman was balancing a metal box or can on her head (a typical way to carry water at that time). They also perceived the family as sitting under a tree. Westerners, used to running water and box-like houses with corners, were more likely to perceive the family as being indoors, with the woman sitting under a window (Gregory & Gombrich, 1973).

Figure 17.4 Big and “little”

The “little guy” shown here is actually a 6’9’’ former Hope College basketball center who would tower over most of us. But he seemed like a short player when matched in a semi-pro game against the world’s tallest basketball player at that time, 7’9’’ Sun Ming Ming from China.

Figure 17.5 What emotion is this?

(See Figure 17.6.)

Figure 17.6 Context makes clearer

The Hope College volleyball team celebrates its national championship winning moment.

Motivation

Motives give us energy as we work toward a goal. Like context, they can bias our interpretations of neutral stimuli. Consider these findings:

- Desirable objects, such as a water bottle viewed by a thirsty person, seem closer than they really are (Balcetis & Dunning, 2010). This perceptual bias energizes our going for it.

- A to-be-climbed hill can seem steeper when we are carrying a heavy backpack, and a walking destination further away when we are feeling tired (Burrow et al., 2016; Philbeck & Witt, 2015; Proffitt 2006a,b). Going on a diet can lighten our biological “backpack” (Taylor-Covill & Eves, 2016). When heavy people lose weight, hills and stairs no longer seem so steep.

- A softball appears bigger when you’re hitting well, as researchers observed after asking players to choose a circle the size of the ball they had just hit well or poorly. There’s also a reciprocal phenomenon: Seeing a target as bigger—as happens when athletes focus directly on a target—improves performance (Witt et al., 2012).

Emotion

Other clever experiments have demonstrated that emotions can shove our perceptions in one direction or another.

- Hearing sad music can predispose people to perceive a sad meaning in spoken homophonic words—mourning rather than morning, die rather than dye, pain rather than pane (Halberstadt et al., 1995).

- When angry, people more often perceive neutral objects as guns (Baumann & DeSteno, 2010).

- When mildly upset by subliminal exposure to a scowling face, people perceive a neutral face as less attractive and likeable (Anderson et al., 2012).

Emotions and motives color our social perceptions, too. People more often perceive solitary confinement, sleep deprivation, and cold temperatures as “torture” when experiencing a small dose of such themselves (Nordgren et al., 2011). Spouses who feel loved and appreciated perceive less threat in stressful marital events—“He’s just having a bad day” (Murray et al., 2003).

The moral of all these examples? Much of what we perceive comes not just from what’s “out there,” but also from what’s behind our eyes and between our ears. Through top-down processing, our experiences, assumptions, expectations—and even our context, motivation, and emotions—can shape and color our views of reality.