Sleep Deprivation and Sleep Disorders

When our body yearns for sleep but does not get it, we begin to feel terrible. Trying to stay awake, we will eventually lose. It’s easy to spot students who have stayed up late: They are often fighting the “nods” (their heads bobbing downward in seconds-long “microsleeps”) as they fight to stay awake.

In the tiredness battle, sleep always wins. In 1989, Michael Doucette was named America’s Safest Driving Teen. In 1990, while driving home from college, he fell asleep at the wheel and collided with an oncoming car, killing both himself and the other driver. Michael’s driving instructor later acknowledged never having mentioned sleep deprivation and drowsy driving (Dement, 1999).

Effects of Sleep Loss

Today, more than ever, our sleep patterns leave us not only sleepy but drained of energy and feelings of well-being. This tiredness tendency has grown so steadily that some researchers have labeled current times the “Great Sleep Recession” (Keyes et al., 2015). After several 5-hour nights, we accumulate a sleep debt that cannot be satisfied by one long sleep. “The brain keeps an accurate count of sleep debt for at least two weeks,” reported sleep researcher William Dement (1999, p. 64).

Obviously, then, we need sleep. Sleep commands roughly one-third of our lives — some 25 years, on average. Allowed to sleep unhindered, most adults will sleep at least 9 hours a night (Coren, 1996). With that much sleep, we awaken refreshed, sustain better moods, and perform more efficiently and accurately. The U.S. Navy and the National Institutes of Health have demonstrated the benefits of unrestricted sleep in experiments in which volunteers spent 14 hours daily in bed for at least a week. For the first few days, the volunteers averaged 12 hours of sleep or more per day, apparently paying off a sleep debt that averaged 25 to 30 hours. That accomplished, they then settled back to 7.5 to 9 hours nightly and felt energized and happier (Dement, 1999). In one Gallup survey (Mason, 2005), 63 percent of adults who reported getting the sleep they needed also reported being “very satisfied” with their personal life (as did only 36 percent of those needing more sleep). And when 909 working women reported on their daily moods, the researchers were struck by what mattered little (such as money, so long as the person was not battling poverty), and what mattered a lot: less time pressure at work and a good night’s sleep (Kahneman et al., 2004).

“Maybe ‘Bring Your Pillow to Work Day’ wasn’t such a good idea.”

In one survey, 28 percent of high school students acknowledged falling asleep in class at least once a week (NSF, 2006). College and university students are also sleep deprived; 69 percent in one national survey reported “feeling tired” or “having little energy” on at least several days during the two previous weeks (AP, 2009). The going needn’t get boring before students start snoring. For students, less sleep also predicts more conflicts in friendships and romantic relationships (Gordon & Chen, 2014; Tavernier & Willoughby, 2014). Tiredness triggers testiness. (To assess whether you are one of the many sleep-deprived students, see Table 24.1.)

| Cornell University psychologist James Maas reported that most students suffer the consequences of sleeping less than they should. To see if you are in that group, answer the following true-false questions: | ||

| True | False | |

|---|---|---|

| .......... | .......... |

|

| .......... | .......... |

|

| .......... | .......... |

|

| .......... | .......... |

|

| .......... | .......... |

|

| .......... | .......... |

|

| .......... | .......... |

|

| .......... | .......... |

|

| .......... | .......... |

|

| .......... | .......... |

|

| .......... | .......... |

|

| .......... | .......... |

|

| .......... | .......... |

|

| .......... | .......... |

|

| .......... | .......... |

|

| If you answered “true” to three or more items, you probably are not getting enough sleep. To determine your sleep needs, Maas recommends that you “go to bed 15 minutes earlier than usual every night for the next week — and continue this practice by adding 15 more minutes each week — until you wake without an alarm and feel alert all day.” [Sleep Quiz reprinted with permission from James B. Maas, “Sleep to Win!” (Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2013).] | ||

Sleep loss is also a predictor of depression (Baglioni et al., 2016). Researchers who studied 15,500 12- to 18-year-olds found that those who slept 5 or fewer hours a night had a 71 percent higher risk of depression than their peers who slept 8 hours or more (Gangwisch et al., 2010). This link does not appear to reflect an effect of depression on sleep. When children and youth are followed through time, sleep loss predicts depression rather than vice versa (Gregory et al., 2009). Moreover, REM sleep’s processing of emotional experiences helps protect against depression (Walker & van der Helm, 2009). After a good night’s sleep, we often do feel better the next day. And that may help to explain why parentally enforced bedtimes predict less depression, and why pushing back school start times leads to improved adolescent sleep, alertness, and mood (Perkinson-Gloor et al., 2013; Winsler et al., 2015). Thus, European high schools rarely start before 9 A.M. (Fischetti, 2014). And the American Academy of Pediatrics (2014) advocates similarly delaying adolescents’ school start times to “allow students the opportunity to achieve optimal levels of sleep (8.5–9.5 hours).”

Smartphones as sleep stealers: “ You wake up in the middle of the night and grab your smartphone to check the time — it’s 3 A.M. — and see an alert. Before you know it, you fall down a rabbit hole of email and Twitter. Sleep? Forget it.”

Nick Bilton, “Disruptions: For a Restful Night, Make Your Smartphone Sleep on the Couch,” 2014

Sleep-deprived students often function below their peak. And they know it: Four in five teens and three in five 18- to 29-year-olds wish they could get more sleep on weekdays (Mason, 2003, 2005). “Sleep deprivation has consequences — difficulty studying, diminished productivity, tendency to make mistakes, irritability, fatigue,” noted Dement (1999, p. 231). A large sleep debt “makes you stupid.” Yet that teen who staggers glumly out of bed in response to an unwelcome alarm, yawns through morning classes, and feels half-depressed much of the day may be energized at 11:00 P.M. and unmindful of the next day’s looming sleepiness (Carskadon, 2002).

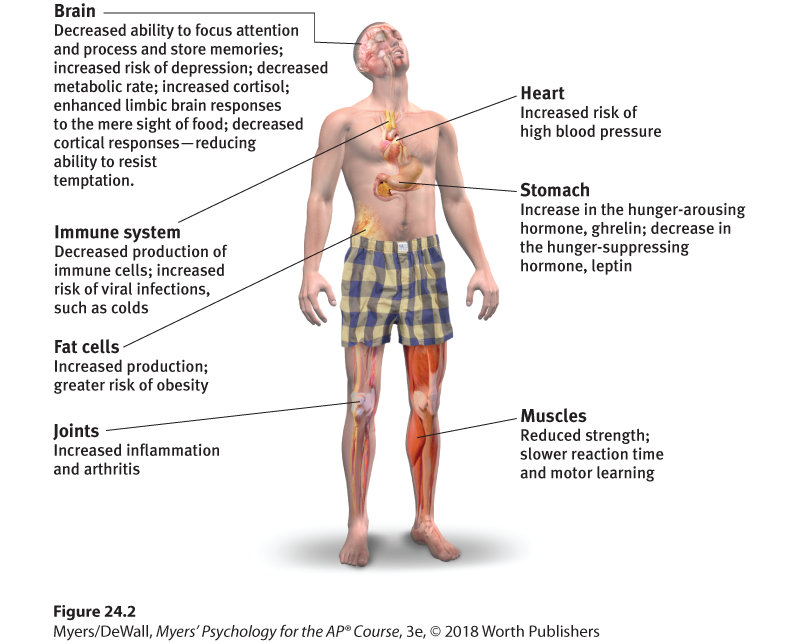

Lack of sleep can also make you gain weight. Sleep deprivation

- increases ghrelin, a hunger-arousing hormone, and decreases its hunger-suppressing partner, leptin (Shilsky et al., 2012) (More on these in Module 38.)

- decreases metabolic (energy use) rate (Buxton et al., 2012).

- increases production of cortisol, a stress hormone that stimulates the body to make fat.

- enhances limbic brain responses to the mere sight of food and decreases cortical responses that help us resist temptation (Benedict et al., 2012; Greer et al., 2013; St-Onge et al., 2012).

Thus, children and adults who sleep less are heavier than average, and in recent decades people have been sleeping less and weighing more (Shiromani et al., 2012; Suglia et al., 2014). Moreover, experimental sleep deprivation increases appetite and eating; our tired brain finds fatty foods more enticing (Fang et al., 2015; Hanlon et al., 2015). So, sleep loss helps explain the weight gain common among sleep-deprived students (Hull et al., 2007).

Sleep also affects our physical health. When infections do set in, we typically sleep more, boosting our immune cells. Sleep deprivation can suppress immune cells that battle viral infections and cancer (Möller-Levet et al., 2013; Motivala & Irwin, 2007; Opp & Krueger, 2015). One experiment exposed volunteers to a cold virus. Those who averaged less than 5 hours’ sleep a night were 4.5 times more likely to develop a cold than those who slept more than 7 hours a night (Prather et al., 2015). Sleep’s protective effect may help explain why people who sleep 7 to 8 hours a night tend to outlive those who are chronically sleep deprived, and why older adults who have no difficulty falling or staying asleep tend to live longer than their sleep-deprived agemates (Dew et al., 2003; Parthasarathy et al., 2015; Scullin & Bliwise, 2015).

Sleep deprivation slows reactions and increases errors on visual attention tasks similar to those involved in screening airport baggage, performing surgery, and reading X-rays (Caldwell, 2012; Lim & Dinges, 2010). Slow responses can also spell disaster for those operating equipment, piloting, or driving. Drowsy driving has contributed to an estimated one in six American traffic accidents (AAA, 2010) and to some 30 percent of Australian highway deaths (Maas, 1999). One two-year study examined the driving accidents of more than 20,000 Virginia 16- to 18-year-olds in two major cities. In one city, the high schools started 75 to 80 minutes later than in the other. The late starters had about 25 percent fewer crashes (Vorona et al., 2011). When sleepy frontal lobes confront an unexpected situation, misfortune often results.

“ So shut your eyes Kiss me goodbye And sleep Just sleep.”

My Chemical Romance, “Sleep”

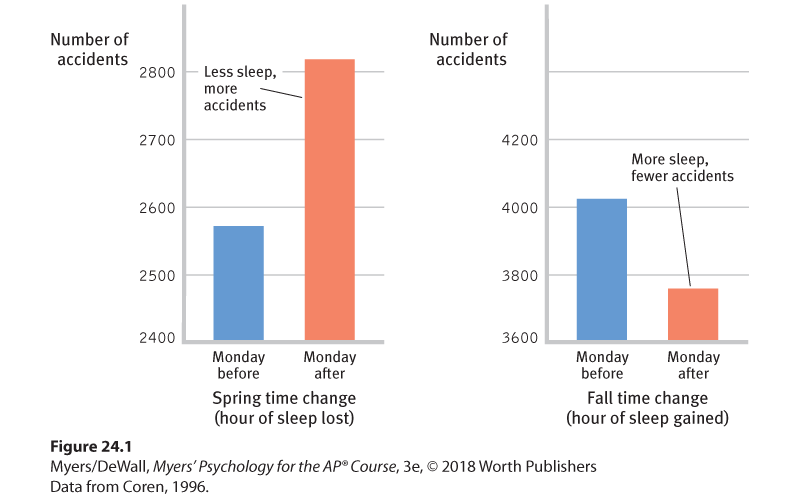

Stanley Coren capitalized on what is, for many North Americans, a semi-annual sleep-manipulation experiment — the “spring forward” to daylight saving time and “fall back” to standard time. Searching millions of Canadian and U.S. records, Coren found that accidents increased immediately after the spring-forward time change, which shortens sleep (Figure 24.1).

Figure 24.1 Less sleep = more accidents

On the Monday after the spring time change, when people lose one hour of sleep, accidents increased, as compared with the Monday before. In the fall, traffic accidents normally increase because of greater snow, ice, and darkness, but they diminished after the time change.

The same spring-forward effect appeared in another study, which showed that tired people are more likely to “cyberloaf” — to fritter away time online. On the Monday after daylight saving time begins, entertainment-related Google searches have been 3.1 percent higher than on the preceding Monday, and 6.4 percent higher than on the following Monday (Wagner et al., 2012). On that “sleepy Monday,” U.S. judges also punish offenders with sentences that are 5 percent longer than average (Cho et al., 2017).

Figure 24.2 summarizes the effects of sleep deprivation. But there is good news! Psychologists have discovered a treatment that strengthens memory, increases concentration, boosts mood, moderates hunger, reduces obesity, fortifies the immune system, and lessens the risk of fatal accidents. Even better news: The treatment feels good, it can be self-administered, the supplies are limitless, and it’s free! If you are a typical high school student, often going to bed near midnight and dragged out of bed six or seven hours later by the dreaded alarm, the treatment is simple. Each night, just add 15 minutes to your sleep until you feel more like a rested and energized student and less like a zombie. Ignore that last text, resist the urge to check in with friends online, and succumb to sleep, the gentle tyrant. For some additional tips on getting better quality sleep, see Table 24.2.

Figure 24.2 How sleep deprivation affects us

|

Major Sleep Disorders

Do you have trouble sleeping when anxious or excited? Most of us do. An occasional loss of sleep is nothing to worry about. But about 1 in 10 adults, and 1 in 4 older adults, complain of insomnia — persistent problems in either falling or staying asleep (Irwin et al., 2006). The result is tiredness and increased risk of depression (Baglioni et al., 2016). From middle age on, awakening occasionally during the night becomes the norm, not something to fret over or treat with medication (Vitiello, 2009). Ironically, insomnia becomes worse when we fret about it. In laboratory studies, people with insomnia do sleep less than others. But they typically overestimate how long it takes them to fall asleep and underestimate how long they actually have slept (Harvey & Tang, 2012). Even if we have been awake only an hour or two, we may think we have had very little sleep because it’s the waking part we remember.

The most common quick fixes for true insomnia — sleeping pills and a alcohol — can aggravate the problem, reducing REM sleep and leaving the person with next-day blahs. Such aids can also lead to tolerance — a state in which increasing doses are needed to produce an effect.

Did Brahms need his own lullabies? Cranky, overweight, and nap-prone, classical composer Johannes Brahms exhibited common symptoms of sleep apnea (Margolis, 2000).

Falling asleep is not the problem for people with narcolepsy (from the Greek narke, “numbness,” and lepsis, “seizure”), who have sudden attacks of overwhelming sleepiness, usually lasting less than 5 minutes. Although treatable with medication and a sleep regimen, narcolepsy attacks can occur at the most inopportune times, often triggered by strong emotions — perhaps just after taking a terrific swing at a softball or when laughing loudly, shouting angrily, or having sex (Dement, 1978, 1999). In severe cases, the person collapses directly into a brief period of REM sleep, with loss of muscular tension. People with narcolepsy — 1 in 2000 of us, estimated the Stanford University Center for Narcolepsy (2002) — must therefore live with extra caution. As a traffic menace, “snoozing is second only to boozing,” says the American Sleep Disorders Association, and those with narcolepsy are especially at risk (Aldrich, 1989).

Although 1 in 20 of us have sleep apnea, it was unknown before modern sleep research. Apnea means “with no breath,” and people with this condition intermittently stop breathing during sleep. After an airless minute or so, decreased blood oxygen arouses them enough to snort in air for a few seconds, in a process that repeats hundreds of times each night, depriving them of slow-wave sleep. Apnea sufferers don’t recall these episodes the next day. So, despite feeling fatigued and depressed — and hearing their mate’s complaints about their loud “snoring” — many are unaware of their disorder (Peppard et al., 2006). Sleep apnea is associated with obesity, and as the number of obese Americans has increased, so has sleep apnea, particularly among overweight men (Keller, 2007). Apnea-related sleep loss also contributes to obesity. In addition to loud snoring, other warning signs are daytime sleepiness, irritability, and (possibly) high blood pressure, which increases the risk of a stroke or heart attack (Dement, 1999). If one doesn’t mind looking a little goofy in the dark, the treatment — a masklike device with an air pump that keeps the sleeper’s airway open (imagine a snorkeler at a slumber party) — can effectively relieve apnea symptoms. By so doing, it can also alleviate the depression symptoms that often accompany sleep apnea (Levine, 2012; Wheaton et al., 2012).

Now I lay me down to sleep For many with sleep apnea, a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine applies mild air pressure to keep the airways open, making for sounder sleeping and better quality of life.

Unlike sleep apnea, night terrors target mostly children, who may sit up or walk around, talk incoherently, experience doubled heart and breathing rates, and appear terrified while asleep (Hartmann, 1981). They seldom wake up fully during an episode and recall little or nothing the next morning — at most, a fleeting, frightening image. Unlike nightmares — which, like other dreams, typically occur during early morning REM sleep — night terrors usually occur during the first few hours of NREM-3.

Sleepwalking and sleeptalking are usually childhood disorders and, like narcolepsy, they run in families. Occasional childhood sleepwalking (also called somnambulism) occurs for about one-third of those with a sleepwalking fraternal twin and half of those with a sleepwalking identical twin. The same is true for sleeptalking (Hublin et al., 1997, 1998). Sleepwalking happens during NREM-3 sleep. Sleeptalking — usually garbled or nonsensical — can occur during any sleep stage (Mahowald & Ettinger, 1990). Sleepwalking is usually harmless. After returning to bed on their own or with the help of a family member, few sleepwalkers recall their trip the next morning. About 20 percent of 3- to 12-year-olds have at least one episode of sleepwalking, usually lasting 2 to 10 minutes; some 5 percent have repeated episodes (Giles et al., 1994). Young children, who have the deepest and lengthiest NREM-3 sleep, are the most likely to experience both night terrors and sleepwalking. As we grow older and deep NREM-3 sleep diminishes, so do night terrors and sleepwalking. (See Table 24.3 for a summary of these sleep disorders.)

| Disorder | Rate | Description | Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insomnia | 1 in 10 adults; 1 in 4 older adults | Ongoing difficulty falling or staying asleep. | Chronic tiredness. Reliance on sleeping pills and alcohol, which reduce REM sleep and lead to tolerance — a state in which increasing doses are needed to produce an effect. |

| Narcolepsy | 1 in 2000 adults | Sudden attacks of overwhelming sleepiness. | Risk of falling asleep at a dangerous moment. Narcolepsy attacks usually last less than 5 minutes, but they can happen at the worst and most emotional times. Everyday activities, such as driving, require extra caution. |

| Sleep apnea | 1 in 20 adults | Stopping breathing repeatedly while sleeping. | Fatigue and depression (as a result of slow-wave sleep deprivation). Associated with obesity (especially among men). |

| Sleepwalking and sleeptalking1 | 1–15 in 100 in the general population for sleepwalking; about half of young children for sleeptalking | Doing normal waking activities (sitting up, walking, speaking) while asleep. Sleeptalking can occur during any sleep stage. Sleepwalking happens in NREM-3 sleep. | Few serious concerns. Sleepwalkers return to their beds on their own or with the help of a family member, rarely remembering their trip the next morning. |

| Night terrors | 1 in 100 adults; 1 in 30 children | Appearing terrified, talking nonsense, sitting up, or walking around during NREM-3 sleep; different from nightmares. | Doubling of a child’s heart and breathing rates during the attack. Luckily, children remember little or nothing of the fearful event the next day. As people age, night terrors become more and more rare. |