Memory Construction Errors

Nearly two-thirds of Americans agree: “Human memory works like a video camera, accurately recording the events we see and hear so that we can review and inspect them later” (Simons & Chabris, 2011). Actually, memory is not so precise. Like scientists who infer a dinosaur’s appearance from its remains, we infer our past from stored information plus what we later imagined, expected, saw, and heard. We don’t just retrieve memories, we reweave them.

Our memories are like Wikipedia pages, capable of continuous revision. When we “replay” a memory, we often replace the original with a slightly modified version, rather like what happens in the telephone game, as a whispered message gets progressively altered when passed from person to person (Hardt et al., 2010). (Memory researchers call this reconsolidation.) So, in a sense, said Joseph LeDoux (2009), “your memory is only as good as your last memory. The fewer times you use it, the more pristine it is.” This means that, to some degree, “all memory is false” (Bernstein & Loftus, 2009b).

Despite knowing all this, I [DM] recently rewrote my own past. It happened at an international conference, where memory researcher Elizabeth Loftus (2012) was demonstrating how memory works. Loftus showed us a handful of individual faces that we were later to identify, as if in a police lineup. Then she showed us some pairs of faces, one face we had seen earlier and one we had not, and asked us to identify the one we had seen. But one pair she had slipped in included two new faces, one of which was rather like a face we had seen earlier. Most of us understandably but wrongly identified this face as one we had previously seen. To climax the demonstration, she showed us the originally seen face and the previously chosen wrong face and asked us to choose the original face we had seen. Most of us picked the wrong face! As a result of our memory reconsolidation, we—an audience of psychologists who should have known better—had replaced the original memory with a false memory.

“Someday we’ll look back at this time in our lives and be unable to remember it.”

Clinical researchers have experimented with memory reconsolidation. People recalled a traumatic or negative experience and then had the reconsolidation of that memory disrupted, with a drug or brief, painless electroconvulsive shock (Kroes et al., 2014; Lonergan et al., 2013). Someday it might become possible to erase your memory of a specific traumatic experience—by reactivating your memory and then disrupting its storage in this way. Would you wish for this? If brutally assaulted, would you welcome having your memory of the attack and its associated fears deleted?

Misinformation and Imagination Effects

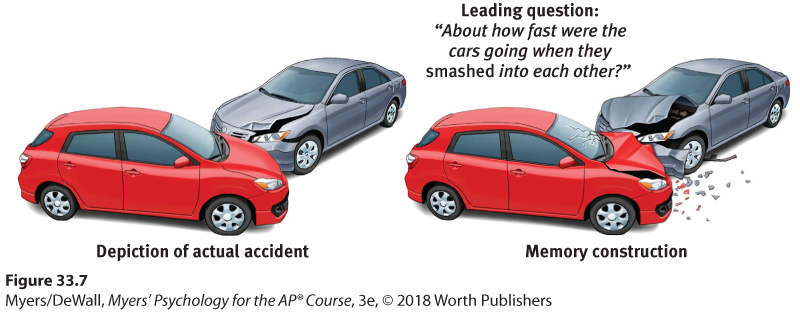

In more than 200 experiments involving more than 20,000 people, Loftus has shown how eyewitnesses reconstruct their memories after a crime or accident. In one important study, two groups of people watched a film clip of a traffic accident and then answered questions about what they had seen (Loftus & Palmer, 1974). Those asked, “About how fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?” gave higher speed estimates than those asked, “About how fast were the cars going when they hit each other?” A week later, when asked whether they recalled seeing any broken glass, people who had heard smashed were more than twice as likely to report seeing glass fragments (Figure 33.7). In fact, the clip showed no broken glass.

Figure 33.7 Memory construction

In this experiment, people viewed a film clip of a car accident. Those who later were asked a leading question recalled a more serious accident than they had witnessed (Loftus & Palmer, 1974).

Flip It Video: Misinformation Effect and Source Amnesia

Flip It Video: Misinformation Effect and Source Amnesia

In many follow-up experiments around the world, others have witnessed an event, received or not received misleading information about it, and then taken a memory test. The repeated result is a misinformation effect: When exposed to subtle misleading information, we may misremember (Loftus et al., 1992). A yield sign becomes a stop sign, hammers become screwdrivers, Coke cans become peanut cans. Breakfast cereal becomes eggs. And a clean-shaven man morphs into a man with a mustache.

So powerful is the misinformation effect that it can influence later attitudes and behaviors (Bernstein & Loftus, 2009a). One experiment falsely suggested to some Dutch university students that, as children, they became ill after eating spoiled egg salad (Geraerts et al., 2008). After absorbing that suggestion, they were less likely to eat egg salad sandwiches, both immediately and four months later.

“ Memory is insubstantial. Things keep replacing it. Your batch of snapshots will both fix and ruin your memory. . . . You can’t remember anything from your trip except the wretched collection of snapshots.”

Annie Dillard, “To Fashion a Text,” 1988

Even repeatedly imagining nonexistent actions and events can create false memories. In one study, Canadian university students were asked to recall two events from their past. One event actually happened; the other was a false event that involved committing a crime, such as assaulting someone with a weapon. Initially, none of the lawful students remembered breaking the law. But after repeated interviewing, 70 percent of students reported a detailed false memory of having committed the crime (Shaw & Porter, 2015).

Misinformation and imagination effects occur partly because visualizing something and actually perceiving it activate similar brain areas (Gonsalves et al., 2004). Imagined events also later seem more familiar, and familiar things seem more real. The more vividly we can imagine things, the more likely they are to become memories (Loftus, 2001; Porter et al., 2000).

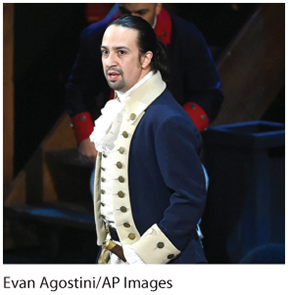

Was Alexander Hamilton a U.S. president? Sometimes our mind tricks us into misremembering dates, places, and names. This often happens because we misuse familiar information. In one study, many people mistakenly recalled Alexander Hamilton—the subject of a popular Broadway musical whose face also appears on the U.S. $10 bill—as a U.S. president (Roediger & DeSoto, 2016).

Digitally altered photos have also produced this imagination inflation. In experiments, researchers have altered photos from a family album to show some family members taking a hot air balloon ride. After viewing these photos (rather than photos showing just the balloon), children reported more false memories and indicated high confidence in those memories. When interviewed several days later, they reported even richer details of their false memories (Strange et al., 2008; Wade et al., 2002). Similarly, when Slate magazine readers in 2012 were shown a doctored photo of U.S. President Barack Obama and Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad shaking hands, 26 percent recalled the event—despite it never having happened (Frenda et al., 2013).

In British and Canadian university surveys, one-fourth of students have reported autobiographical memories that they later realized were not accurate (Foley, 2015; Mazzoni et al., 2010). I [DM] empathize. For decades, my cherished earliest memory was of my parents getting off the bus and walking to our house, bringing my baby brother home from the hospital. When, in middle age, I shared that memory with my father, he assured me they did not bring their newborn home on the Seattle Transit System. The human mind, it seems, comes with built-in Photoshopping software. The moral: Don’t believe everything you remember.

Source Amnesia

What is the frailest part of a memory? Its source. We may recognize someone but have no idea where we have seen the person. We may tell a friend some gossip, only to learn we got the news from the friend. We may dream an event and later be unsure whether it really happened. Famed child psychologist Jean Piaget was startled as an adult to learn that a vivid, detailed memory from his childhood—a nursemaid’s thwarting his kidnapping—was utterly false. He apparently constructed the memory from repeatedly hearing the story (which his nursemaid, after undergoing a religious conversion, later confessed had never happened). In attributing his “memory” to his own experiences, rather than to his nursemaid’s stories, Piaget exhibited source amnesia (also called source misattribution). Misattribution is at the heart of many false memories. Authors, songwriters, and stand-up comedians sometimes suffer from it. They think an idea came from their own creative imagination, when in fact they are unintentionally plagiarizing something they earlier read or heard.

Famous psychologists and artists aren’t the only ones to experience source amnesia. Preschoolers interacted with “Mr. Science,” who engaged them in activities such as blowing up a balloon with baking soda and vinegar (Poole & Lindsay, 1995, 2001). Three months later, on three successive days, their parents read them a story describing some things the children had experienced with Mr. Science and some they had not. When a new interviewer asked what Mr. Science had done with them—“Did Mr. Science have a machine with ropes to pull?”—4 in 10 children spontaneously recalled him doing things that had happened only in the story.

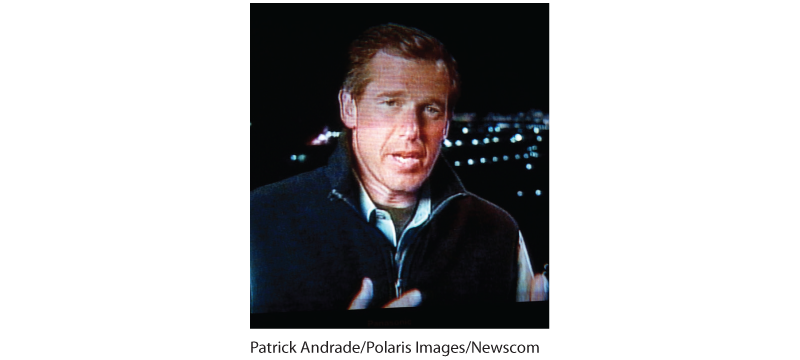

“Lyin’ Brian”? Or a victim of false memory? In 2015, NBC Nightly News anchor Brian Williams recounted a story about traveling in a military helicopter that was hit with a rocket-propelled grenade. But the event never happened as he described. The public branded him as a liar, leading his bosses to fire him. Several memory researchers had a different opinion. “I think a lot of people don’t appreciate the extent to which false memories can happen even when we are extremely confident in the memory,” noted psychologist Christopher Chabris (2015).

Source amnesia also helps explain déjà vu (French for “already seen”). Two-thirds of us have experienced this fleeting, eerie sense that “I’ve been in this exact situation before.” The key to déjà vu seems to be familiarity with a stimulus without a clear idea of where we encountered it before (Brown & Marsh, 2009; Cleary, 2008). Normally, we experience a feeling of familiarity (thanks to temporal lobe processing) before we consciously remember details (thanks to hippocampus and frontal lobe processing). When these functions (and brain regions) are out of sync, we may experience a feeling of familiarity without conscious recall. Our amazing brains try to make sense of such an improbable situation, and we get an eerie feeling that we’re reliving some earlier part of our life. Our source amnesia forces us to do our best to make sense of an odd moment.

“ Do you ever get that strange feeling of vujà dé? Not déjà vu; vujà dé. It’s the distinct sense that, somehow, something just happened that has never happened before. Nothing seems familiar. And then suddenly the feeling is gone. Vujà dé.”

Comedian George Carlin (1937–2008), in Funny Times, December 2001

Discerning True and False Memories

Since memory is reconstruction as well as reproduction, we can’t be sure whether a memory is real by how real it feels. Much as perceptual illusions may seem like real perceptions, unreal memories feel like real memories. Because the misinformation effect and source amnesia happen outside our awareness, it is hard to separate false memories from real ones (Schooler et al., 1986). Perhaps you can recall describing a childhood experience to a friend and filling in memory gaps with reasonable guesses. We all do it. After more retellings, those guessed details—now absorbed into your memory—may feel as real as if you had actually observed them (Roediger et al., 1993). False memories, like fake diamonds, seem so real.

False memories can be persistent. Imagine that we were to read aloud a list of words such as candy, sugar, honey, and taste. Later, we ask you to recognize the presented words from a larger list. If you are at all like the people tested by Henry Roediger and Kathleen McDermott (1995), you would err three out of four times—by falsely remembering a nonpresented similar word, such as sweet. We more easily remember the gist than the words themselves.

Memory construction can help us understand why some people have been sent to prison for crimes they never committed. Of 337 people who were later proven not guilty by DNA testing, 71 percent had been convicted because of faulty eyewitness identification (Innocence Project, 2015; Smalarz & Wells, 2015). It explains why “hypnotically refreshed” memories of crimes so easily incorporate errors, some of which originate with the hypnotist’s leading questions (“Did you hear loud noises?”). It explains why dating partners who fell in love have overestimated their first impressions of one another (“It was love at first sight”), while those who broke up underestimated their earlier liking (“We never really clicked”) (McFarland & Ross, 1987). And it explains why people asked how they felt 10 years ago about marijuana or gender issues recalled attitudes closer to their current views than to the views they had actually reported a decade earlier (Markus, 1986). People tend to recall having always felt as they feel today (Mazzoni & Vannucci, 2007; and recall from Module 4 our tendency to hindsight bias).

“ It isn’t so astonishing, the number of things I can remember, as the number of things I can remember that aren’t so.”

Author Mark Twain (1835–1910)

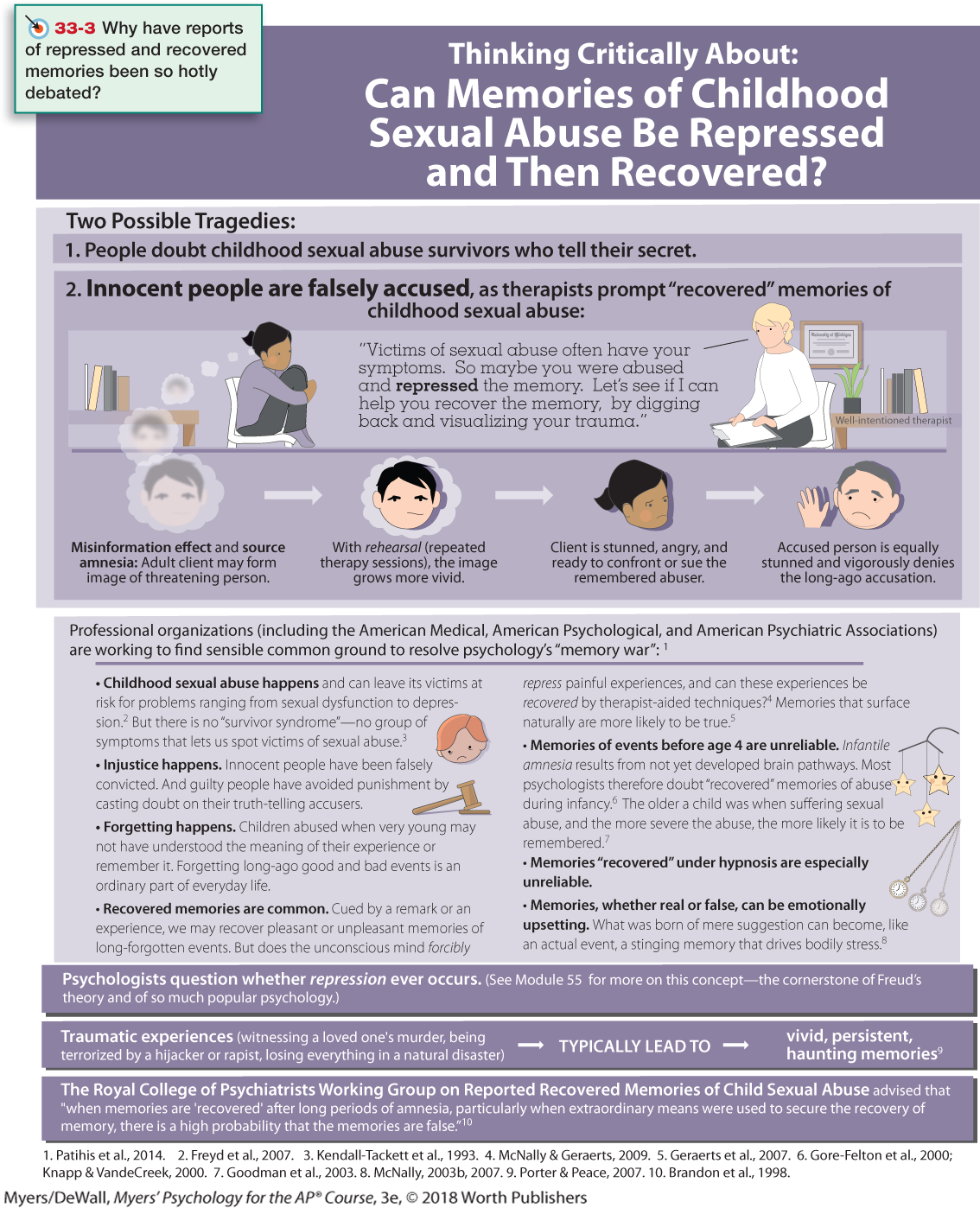

One research team interviewed 73 ninth-grade boys and then reinterviewed them 35 years later. When asked to recall how they had reported their attitudes, activities, and experiences, most men recalled their ninth-grade statements at a rate no better than chance. Only 1 in 3 now remembered receiving physical punishment, though as ninth-graders 82 percent had said they had (Offer et al., 2000). As George Vaillant (1977, p. 197) noted after following adult lives through time, “It is all too common for caterpillars to become butterflies and then to maintain that in their youth they had been little butterflies. Maturation makes liars of us all.” Memory construction errors also seem to be at work in many “recovered” memories of childhood abuse. See Thinking Critically About: Can Memories of Childhood Sexual Abuse Be Repressed and Then Recovered?

Children’s Eyewitness Recall

If memories can be sincere, yet sincerely wrong, how can jurors decide cases in which children’s memories of sexual abuse are the only evidence? “It would be truly awful to ever lose sight of the enormity of child abuse,” observed Stephen Ceci (1993). Yet Ceci and Maggie Bruck’s (1993, 1995) studies of children’s memories have made them aware of how easily children’s memories can be molded. For example, they asked 3-year-olds to show on anatomically correct dolls where a pediatrician had touched them. Of the children who had not received genital examinations, 55 percent pointed to either genital or anal areas.

In other experiments, the researchers studied the effect of suggestive interviewing techniques (Bruck & Ceci, 1999, 2004). In one study, children chose a card from a deck of possible happenings, and an adult then read the card to them. For example, “Think real hard, and tell me if this ever happened to you. Can you remember going to the hospital with a mousetrap on your finger?” In interviews, the same adult repeatedly asked children to think about several real and fictitious events. After 10 weeks of this, a new adult asked the same question. The stunning result: 58 percent of preschoolers produced false (often vivid) stories regarding one or more events they had never experienced (Ceci et al., 1994). Here’s one:

My brother Colin was trying to get Blowtorch [an action figure] from me, and I wouldn’t let him take it from me, so he pushed me into the wood pile where the mousetrap was. And then my finger got caught in it. And then we went to the hospital, and my mommy, daddy, and Colin drove me there, to the hospital in our van, because it was far away. And the doctor put a bandage on this finger.

Given such detailed stories, professional psychologists who specialize in interviewing children could not reliably separate the real memories from the false ones. Nor could the children themselves. The above child, reminded that his parents had told him several times that the mousetrap incident never happened—that he had imagined it—protested, “But it really did happen. I remember it!” Unfortunately, this type of error is common. In one analysis of eyewitness data from over 20,000 participants, children regularly identified innocent suspects as guilty (Fitzgerald & Price, 2015). “[The] research,” said Ceci (1993), “leads me to worry about the possibility of false allegations. It is not a tribute to one’s scientific integrity to walk down the middle of the road if the data are more to one side.”

Children can, however, be accurate eyewitnesses. When questioned about their experiences in neutral words they understood, children often accurately recalled what happened and who did it (Brewin & Andrews, 2016; Goodman, 2006). When interviewers used less suggestive, more effective techniques, even 4- to 5-year-old children produced more accurate recall (Holliday & Albon, 2004; Pipe et al., 2004). Children were especially accurate when they had not talked with involved adults prior to the interview and when their disclosure was made in a first interview with a neutral person who asked nonleading questions.