Language and Thought

Thinking and language—which comes first? This is one of psychology’s great chicken-and-egg questions. Do our ideas come first and then the words to name them? Or are our thoughts conceived in words and unthinkable without them?

Linguist Benjamin Lee Whorf (1956) contended that “language itself shapes a [person’s] basic ideas.” The Hopi, who have no past tense for their verbs, could not readily think about the past, he said. Today’s psychologists believe that a strong form of Whorf’s idea—linguistic determinism—is too extreme. We all think about things for which we have no words. (Can you think of a shade of blue you cannot name?) And we routinely have unsymbolized (wordless, imageless) thoughts, as when someone, while watching two men carry a load of bricks, wondered whether the men would drop them (Heavey & Hurlburt, 2008; Hurlburt et al., 2013).

Nevertheless, a weaker version of linguistic determinism—linguistic influence—rightly emphasizes that our words affect our thinking (Gentner, 2016). To those who speak two dissimilar languages, such as English and Japanese, it seems obvious that a person may think differently in different languages (Brown, 1986). Unlike English, which has a rich vocabulary for self-focused emotions such as anger, Japanese has more words for interpersonal emotions such as sympathy (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Many bilingual individuals report that they have different senses of self—that they feel like different people—depending on which language they are using (Matsumoto, 1994; Pavlenko, 2014). In one series of studies with bilingual Israeli Arabs (who spoke both Arabic and Hebrew), participants thought differently about their social world, with differing automatic associations with Arabs and Jews, depending on which language the testing session used (Danziger & Ward, 2010). Depending on which emotion they want to express, bilingual people often switch languages. “When my mom gets angry at me, she’ll speak in Mandarin,” explained one Chinese-American student. “If she’s really mad, she’ll switch to Cantonese” (Chen et al., 2012). Bilingual individuals may even reveal different personality profiles when taking the same test in two languages, with their differing cultural associations (Chen & Bond, 2010; Dinges & Hull, 1992). When China-born, bilingual University of Waterloo students were asked to describe themselves in English, their responses fit typical Canadian profiles, expressing mostly positive self-statements and moods. When responding in Chinese, the same students gave typically Chinese self-descriptions, reporting more agreement with Chinese values and roughly equal positive and negative self-statements and moods (Ross et al., 2002). Similar attitude and personality changes have been shown when bicultural, bilingual people shift between the cultural frames associated with Spanish and English, or Arabic and English (Ogunnaike et al., 2010; Ramírez-Esparza et al., 2006). When responding in their second language, bilingual people’s moral judgments reflect less emotion—they respond with more “head” than “heart” (Costa et al., 2014). “Learn a new language and get a new soul,” says a Czech proverb.

So our words do influence our thinking (Boroditsky, 2011). Words define our mental categories. In Brazil, the isolated Piraha people have words for the numbers 1 and 2, but numbers above that are simply “many.” Thus, if shown 7 nuts in a row, they find it difficult to lay out the same number from their own pile (Gordon, 2004).

Words also influence our thinking about colors. Whether we live in New Mexico, New South Wales, or New Guinea, we see colors much the same, but we use our native language to classify and remember them (Davidoff, 2004; Roberson et al., 2004, 2005). Imagine viewing three colors and calling two of them “yellow” and one of them “blue.” Later you would likely see and recall the yellows as being more similar. But if you speak the language of Papua New Guinea’s Berinmo tribe, which has words for two different shades of yellow, you would more speedily perceive and better recall the variations between the two yellows. And if your language is Russian, which has distinct names for various shades of blue, such as goluboy and siniy, you might recall the yellows as more similar and remember the blue better. Words matter.

Culture and color In Papua New Guinea, Berinmo children have words for different shades of “yellow,” which might enable them to spot and recall yellow variations more quickly. Here and everywhere, “the languages we speak profoundly shape the way we think, the way we see the world, the way we live our lives,” noted psychologist Lera Boroditsky (2009).

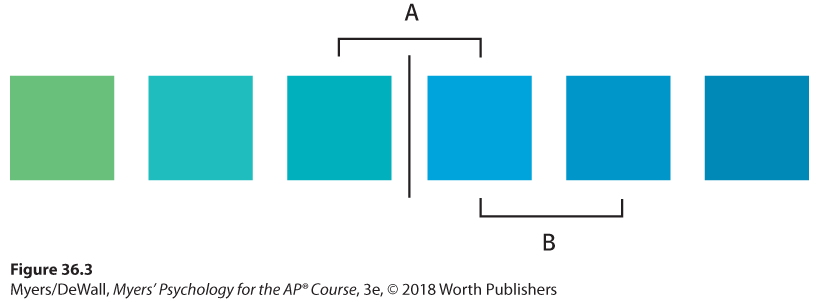

Perceived differences grow as we assign different names. On the color spectrum, blue blends into green—until we draw a dividing line between the portions we call “blue” and “green.” Although equally different on the color spectrum, two different items that share the same color name (as the two “blues” do in Figure 36.3, contrast B) are harder to distinguish than two items with different names (“blue” and “green,” as in Figure 36.3, contrast A) (Özgen, 2004). Likewise, two places seem closer and more vulnerable to the same natural disaster if labeled as in the same state rather than at an equal distance in adjacent states (Burris & Branscombe, 2005; Mishra & Mishra, 2010). Tornadoes don’t know about state lines, but people do.

Figure 36.3 Language and perception

When people view blocks of equally different colors, they perceive those with different names as more different. Thus the “green” and “blue” in contrast A may appear to differ more than the two equally different blues in contrast B (Özgen, 2004).

Given words’ subtle influence on thinking, we do well to choose our words carefully. Is “A child learns language as he interacts with his caregivers” any different from “Children learn language as they interact with their caregivers”? Many studies have found that it is. When hearing the generic he (as in “the artist and his work”) people are more likely to picture a male (Henley, 1989; Ng, 1990). If he and his were truly gender free, we shouldn’t skip a beat when hearing that “man, like other mammals, nurses his young.”

To expand language is to expand the ability to think. As Unit IX points out, young children’s thinking develops hand in hand with their language (Gopnik & Meltzoff, 1986). Indeed, it is very difficult to think about or conceptualize certain abstract ideas (commitment, freedom, or rhyming) without language. And what is true for preschoolers is true for everyone: It pays to increase your word power. That’s why most textbooks, including this one, introduce new words—to teach new ideas and new ways of thinking. And that’s also why psychologist Steven Pinker (2007) titled his book on language The Stuff of Thought.

Increased word power helps explain what McGill University researcher Wallace Lambert has called the bilingual advantage (Lambert, 1992; Lambert et al., 1993). In some studies (though not all), bilingual people have exhibited skill at inhibiting one language while using the other—for example inhibiting “crayón amarillo” from home speech while saying “yellow crayon” at school (Bialystok et al., 2015; de Bruin et al., 2015a,b). And thanks to their well-practiced “executive control” over language, they also more readily inhibit their attention to irrelevant information (Barac et al., 2016; Kroll & Bialystok, 2013). This superior attentional control is evident from 7 months of age into adulthood and even helps protect against cognitive decline in later life (Bak et al., 2014; Bialystok et al., 2012; Kroll et al., 2014). Bilingual children also exhibit enhanced social skill, by being better able to shift to understand another’s perspective (Fan et al., 2015).

Bilingual people’s switching between different languages does, however, take a moment (Kleinman & Gollan, 2016; Palomar-García et al., 2015). That’s a phenomenon I [DM] failed to realize before speaking to bilingual Chinese colleagues in Beijing. While I spoke in English, my accompanying slides were in Chinese. Alas, I later learned, the translated slides required constant “code switching” from my spoken words, thus making it hard for my audience to process both.

Lambert helped devise a Canadian program that has, since 1981, immersed millions of English-speaking children in French (Statistics Canada, 2013). Not surprisingly, the children attain a natural French fluency unrivaled by other methods of language teaching. Moreover, compared with similarly capable children in control groups, they do so without detriment to their English fluency, and with increased aptitude scores, creativity, and appreciation for French-Canadian culture (Genesee & Gándara, 1999; Lazaruk, 2007).

Whether we are in the linguistic minority or majority, language links us to one another. Language also connects us to the past and the future. “To destroy a people,” goes a saying, “destroy their language.”

Thinking in Images

When you are alone, do you talk to yourself? Is “thinking” simply conversing with yourself? Words do convey ideas. But sometimes ideas precede words. To turn on the cold water in your bathroom, in which direction do you turn the handle? To answer, you probably thought not in words but with implicit (nondeclarative, procedural) memory—a mental picture of how you do it.

Indeed, we often think in images. Artists think in images. So do composers, poets, mathematicians, athletes, and scientists. Albert Einstein reported that he achieved some of his greatest insights through visual images and later put them into words. Pianist Liu Chi Kung harnessed the power of thinking in images. One year after placing second in the 1958 Tchaikovsky piano competition, Liu was imprisoned during China’s cultural revolution. Soon after his release, after seven years without touching a piano, he was back on tour. Critics judged Liu’s musicianship as better than ever. How did he continue to develop without practice? “I did practice,” said Liu, “every day. I rehearsed every piece I had ever played, note by note, in my mind” (Garfield, 1986).

For someone who has learned a skill, such as ballet dancing, even watching the activity will activate the brain’s internal simulation of it, reported one British research team (Calvo-Merino et al., 2004). So, too, will imagining a physical experience, which activates some of the same neural networks that are active during the actual experience (Grèzes & Decety, 2001). Small wonder, then, that mental practice has become a standard part of training for Olympic athletes (Blumenstein & Orbach, 2012; Ungerleider, 2005).

One experiment on mental practice and basketball free-throw shooting tracked the University of Tennessee women’s team over 35 games (Savoy & Beitel, 1996). During that time, the team’s free-throw accuracy increased from approximately 52 percent in games following standard physical practice, to some 65 percent after mental practice. Players had repeatedly imagined making free throws under various conditions, including being “trash-talked” by their opposition. In a dramatic conclusion, Tennessee won the national championship game in overtime, thanks in part to their free-throw shooting.

Mental rehearsal can also help you achieve an academic goal, as researchers demonstrated with two groups of introductory psychology students facing a midterm exam one week later (Taylor et al., 1998). (Students who were not engaged in any mental rehearsal formed a control group.) The first group spent five minutes each day visualizing themselves scanning the posted grade list, seeing their A, beaming with joy, and feeling proud. This daily outcome simulation had little effect, adding only 2 points to their exam-score average. The second group spent five minutes each day visualizing themselves effectively studying—reading the textbook, going over notes, eliminating distractions, declining an offer to go out. This daily process simulation paid off: The group began studying sooner, spent more time at it, and beat the others’ average score by 8 points. The point to remember: It’s better to spend your fantasy time planning how to reach your goal than to focus on your desired destination.

* * *

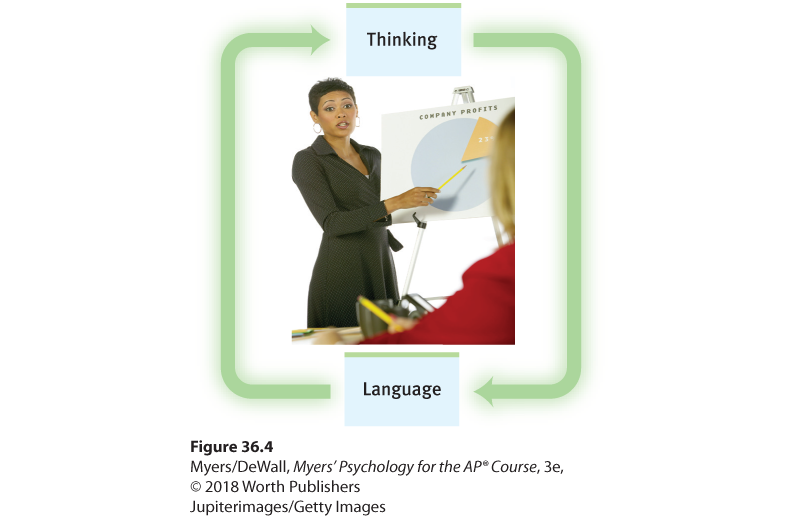

What, then, should we say about the relationship between thinking and language? As we have seen, language influences our thinking. But if thinking did not also affect language, there would never be any new words. And new words and new combinations of old words express new ideas. The basketball term slam dunk was coined after the act itself had become fairly common. Blogs became part of our language after web logs appeared. So, let us say that thinking affects our language, which then affects our thought (Figure 36.4).

Figure 36.4 The interplay of thought and language

The traffic runs both ways between thinking and language. Thinking affects our language, which affects our thought.

Psychological research on thinking and language mirrors the mixed impressions of our species by those in fields such as literature and religion. The human mind is simultaneously capable of striking intellectual failures and of striking intellectual power. Misjudgments are common and can have disastrous consequences. So we do well to appreciate our capacity for error. Yet our ingenuity at problem solving and our extraordinary power of language mark humankind as almost “infinite in faculties.”