Sexual Orientation

We express the direction of our sexual interest in our sexual orientation—which usually is our enduring sexual attraction toward members of our own sex (homosexual orientation) or the other sex (heterosexual orientation). Other variations include an attraction to both sexes (bisexual orientation). We experience our sexual orientation in our interests, thoughts, and fantasies.

Across time and place, cultures vary in their attitudes toward same-sex attractions. Same-sex sexual activity is “not wrong at all,” said 11 percent of Americans in 1973, and 50 percent in 2016 (GSS, 2017). “Should society accept homosexuality?” Yes, say 88 percent of Spaniards and 1 percent of Nigerians, with women everywhere being more accepting than men (Pew, 2013). Yet whether a culture condemns or accepts same-sex unions, heterosexuality is most common, and bisexuality and homosexuality exist. In most African countries, same-sex relationships are illegal. Yet the ratio of lesbian, gay, or bisexual people “is no different from other countries in the rest of the world,” reports the Academy of Science of South Africa (2015). What is more, same-sex activity spans human history, from the prehistoric rock art era to the present.

How many people are exclusively homosexual? According to more than a dozen national surveys in Europe and the United States, about 3 or 4 percent of men and 2 percent of women (Chandra et al., 2011; Herbenick et al., 2010; Savin-Williams et al., 2012). When the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics asked 34,557 Americans about their sexual identity, they found that all but 3.4 percent answered “straight,” with 1.6 percent answering “gay” or “lesbian” and 0.7 percent saying “bisexual” (Ward et al., 2014). In a follow-up survey, 1.6 percent of women and 2.3 percent of men anonymously reported feeling “mostly” or “only” same-sex attraction (Copen et al., 2016). A larger number of adults—13 percent of women and 5 percent of men—report some same-sex sexual contact during their lives (Chandra et al., 2011). In less tolerant places, people are more likely to hide their sexual orientation (though they are no less likely to seek out same-sex content and partners, as evidenced by Google searches and Craigslist ads). About 3 percent of California men express a same-sex preference on Facebook, for example, as do only about 1 percent in Mississippi (MacInnis & Hodson, 2015; Stephens-Davidowitz, 2013).

What does it feel like to have same-sex attractions in a majority heterosexual culture? If you are heterosexual, imagine how you would feel if you were socially isolated for openly admitting or displaying your feelings. How would you react if you overheard people making crude jokes about heterosexual people, or if most movies, TV shows, and advertisements portrayed (or implied) homosexuality? And how would you answer if your family members were pleading with you to change your heterosexual “lifestyle” and to enter into a homosexual marriage?

Facing such reactions, some individuals struggle with their sexual attractions, especially during adolescence and if feeling rejected by parents or harassed by peers. If lacking social support, nonheterosexual teens may have lower self-esteem, higher anxiety and depression, and an increased risk of contemplating suicide (Becker et al., 2014; Lyons, 2015; Wang, J. et al., 2012, 2015). They may at first try to ignore or deny their desires, hoping they will go away. But they don’t. They may try to change their orientation through psychotherapy, willpower, or prayer. But the feelings typically persist, as do those of heterosexual people—who are similarly incapable of change (Haldeman, 1994, 2002; Myers & Scanzoni, 2005).

Driven to suicide In 2010, Rutgers University student Tyler Clementi jumped off this bridge after his roommate secretly filmed, shared, and tweeted about Clementi’s intimate encounter with another man. Reports then surfaced of other gay teens who had reacted in a similarly tragic fashion after being taunted. Since 2010, Americans—especially those under 30—have been increasingly supportive of those with same-sex orientations.

The prevalence of harmful anti-gay stereotypes can also contribute to the isolation and rejection that many nonheterosexual people feel. One such stereotype is that homosexual men are at risk for molesting children (Herek, 2016). But research shows that most men are sexually responsive either to adult women (if straight) or to adult men (if gay), and that some others—many fewer—instead exhibit pedophilia, a disordered attraction to young boys or girls (Blanchard et al., 2012; Dreger, 2011).

Today’s psychologists view sexual orientation as neither willfully chosen nor willfully changed. Sexual orientation in some ways is like handedness: Most people are one way, some the other. A very few are truly ambidextrous. Regardless, the way one is endures. “Efforts to change sexual orientation are unlikely to be successful and involve some risk of harm,” declared a 2009 American Psychological Association report. Recognizing this, in 2016, Malta became the first European country to outlaw the controversial practice of “conversion therapy,” which aims to change people’s gender identities or sexual orientations. Several U.S. states have likewise banned sexual conversion therapy with minors.

Sexual orientation is especially persistent for men. Women’s sexual orientation tends to be less strongly felt and, for some women, is more fluid and changing (Dickson et al., 2013; Norris et al., 2015). In general, men are sexually simpler. Men’s lesser sexual variability is apparent in many ways (Baumeister, 2000). Across time, across cultures, across situations, and across differing levels of education, religious observance, and peer influence, men’s sexual drive and interests are less flexible and varying than are adult women’s. Women, for example, more often prefer to alternate periods of high sexual activity with periods of almost none (Mosher et al., 2005). Baumeister calls this flexibility erotic plasticity.

Environment and Sexual Orientation

So, our sexual orientation seems to be something we do not choose and (especially for males) cannot change. Where, then, do these preferences come from? See if you can anticipate the conclusions that have emerged from hundreds of research studies by responding Yes or No to the following questions:

- Is homosexuality linked with a child’s problematic relationships with parents, such as with a domineering mother and an ineffectual father, or a possessive mother and a hostile father?

- Does homosexuality involve a fear or hatred of people of the other sex, leading individuals to direct their desires toward members of their own sex?

- Is sexual orientation linked with sex hormone levels currently in the blood?

- As children, were most homosexuals molested, seduced, or otherwise sexually victimized by an adult homosexual?

The answer to all these questions has been No (Storms, 1983). In a search for possible environmental influences on sexual orientation, Kinsey Institute investigators interviewed nearly 1000 homosexuals and 500 heterosexuals. They assessed nearly every imaginable psychological cause of homosexuality—parental relationships, childhood sexual experiences, peer relationships, dating experiences (Bell et al., 1981; Hammersmith, 1982). Their findings: Homosexuals are no more likely than heterosexuals to have been smothered by maternal love or neglected by their father. In one national survey of nearly 35,000 adults, those with a same-sex attraction were somewhat more likely to report having experienced child sexual abuse. But 86 percent of the men and 75 percent of the women with same-sex attraction reported no such abuse (Roberts et al., 2013).

And consider this: If “distant fathers” were more likely to produce homosexual sons, then shouldn’t boys growing up in father-absent homes more often be gay? (They are not.) And shouldn’t the rising number of such homes have led to a noticeable increase in the gay population? (It has not.) Most children raised by gay or lesbian parents grow up straight (Gartrell & Bos, 2010). And they grow up within the normal range of healthfulness and emotional well-being (Bos et al., 2016).

Imagine that a mad scientist pitted nature against nurture by, at birth, changing a group of boys into girls—by castrating them, thus surgically feminizing them, and then raising them as girls. Surely this would socialize these “girls” into becoming attracted to males? In seven famous cases, this actually has happened, sometimes as a surgical procedure after the accidental severing of a penis during surgery. In each case, the result was a person attracted to women—just “the result we would expect if male sexual orientation were entirely due to nature,” concluded a consensus statement by sexual orientation experts (Bailey et al., 2016).

So, what else might influence sexual orientation? Could a same-sex experience have an effect? Even in tribal cultures in which homosexual behavior is expected of all boys before marriage, most men are heterosexual (Hammack, 2005; Money, 1987). (As this illustrates, homosexual behavior does not always indicate a homosexual orientation.) Moreover, though peers’ attitudes predict teens’ sexual attitudes and behavior, they do not predict same-sex attraction. “Peer influence has little or no effect” on sexual orientation (Brakefield et al., 2014).

The bottom line from a half-century’s theory and research: If there are environmental factors that influence sexual orientation after we’re born, we do not yet know what they are.

Biology and Sexual Orientation

The seeming absence of environmental influences on sexual orientation has motivated researchers to explore possible biological influences. They have considered

- evidence of same-sex behaviors in other species,

- gay-straight brain differences,

- genetics, and

- prenatal hormones.

Same-Sex Attraction in Other Species

In Boston’s Public Gardens, caretakers solved the mystery of why a much-loved swan couple’s eggs never hatched. Both swans were female. In New York City’s Central Park Zoo, penguins Silo and Roy spent several years as devoted same-sex partners. Same-sex sexual behaviors have also been observed in several hundred other species, including grizzlies, gorillas, monkeys, flamingos, and owls (Bagemihl, 1999). Among rams, for example, some 7 to 10 percent display same-sex attraction by shunning ewes and seeking to mount other males (Perkins & Fitzgerald, 1997). Homosexual behavior seems a natural part of the animal world.

Gay-Straight Brain Differences

Researcher Simon LeVay (1991) studied sections of the hypothalamus taken from deceased heterosexual and homosexual people. As a gay scientist, LeVay wanted to do “something connected with my gay identity.” To avoid biasing the results, he did a blind study, not knowing which donors were gay. For nine months he peered through his microscope at a cell cluster that varied in size among donors. Then, one morning, he broke the code: One cell cluster was reliably larger in heterosexual men than in women and homosexual men. “I was almost in a state of shock,” LeVay said (1994). “I took a walk by myself on the cliffs over the ocean. I sat for half an hour just thinking what this might mean.”

It should not surprise us that in other ways, too, brains differ with sexual orientation (Bao & Swaab, 2011; Savic & Lindström, 2008). Remember our maxim: Everything psychological is simultaneously biological. But when do such brain differences begin? At conception? In the womb? During childhood or adolescence? Does experience produce these differences? Or is it genes or prenatal hormones (or genes activating prenatal hormones)?

LeVay does not view the hypothalamus as a sexual orientation center; rather, he sees it as an important part of the neural pathway engaged in sexual behavior. He acknowledges that sexual behavior patterns may influence the brain’s anatomy. In fish, birds, rats, and humans, brain structures vary with experience—including sexual experience, reports sex researcher Marc Breedlove (1997). But LeVay believes it more likely that brain anatomy influences sexual orientation. His hunch seems confirmed by the discovery of a similar hypothalamic difference between the male sheep that do and don’t display same-sex attraction (Larkin et al., 2002; Roselli et al., 2002, 2004). Moreover, such differences seem to develop soon after birth, or perhaps even before birth (Rahman & Wilson, 2003).

Juliet and Juliet Boston’s beloved swan couple, “Romeo and Juliet,” were discovered actually to be, as are many other animal partners, a same-sex pair.

Responses to hormone-derived sexual scents also point to a brain difference (Savic et al., 2005). When straight women were given a whiff of a scent derived from men’s sweat, their hypothalamus activated in an area governing sexual arousal. Gay men’s brains responded similarly to the men’s scent. But straight men’s brains showed the arousal response only to a female hormone derivative. Other studies of brain responses to sex-related sweat odors and to pictures of male and female faces have found similar gay-straight differences, including differing responses between lesbians and straight women (Kranz & Ishai, 2006; Martins et al., 2005). Researcher Qazi Rahman (2015) sums it up: Compared with heterosexuals, “gay men appear, on average, more ‘female typical’ in brain pattern responses and lesbian women are somewhat more ‘male typical.’”

Genetic Influences

Evidence indicates that “about a third of variation in sexual orientation is attributable to genetic influences” (Bailey et al., 2016). A same-sex orientation does have some tendency to run in families. And identical twins are somewhat more likely than fraternal twins to share a homosexual orientation (Alanko et al., 2010; Långström et al., 2010). Because sexual orientations differ in many identical twin pairs, especially female twins, we know that other factors besides genes are also at work—including, it appears, epigenetic marks that help distinguish gay and straight identical twins (Balter, 2015).

By genetic manipulations, experimenters have created female fruit flies that pursued other females during courtship, and males that pursued other males (Demir & Dickson, 2005). “We have shown that a single gene in the fruit fly is sufficient to determine all aspects of the flies’ sexual orientation and behavior,” explained Barry Dickson (2005). With humans, it’s likely that multiple genes, possibly in interaction with other influences, shape sexual orientation. A genome-wide study of 409 pairs of gay brothers identified sexual orientation links with areas of two chromosomes, one maternally transmitted (Sanders et al., 2015).

Researchers have speculated about possible reasons why “gay genes” might exist in the human gene pool, given that same-sex couples cannot naturally reproduce. One possible answer is kin selection. Recall from Module 15 the evolutionary psychology reminder that many of our genes also reside in our biological relatives. Perhaps, then, gay people’s genes live on through their supporting the survival and reproductive success of their nieces, nephews, and other relatives. Gay men make generous uncles, suggests one study of Samoans (Vasey & VanderLaan, 2010).

A fertile females theory suggests that maternal genetics may also be at work (Bocklandt et al., 2006). Italian studies confirm what others have found—that homosexual men tend to have more homosexual relatives on their mother’s side than on their father’s (Camperio-Ciani et al., 2004, 2009; Camperio-Ciani & Pellizzari, 2012; VanderLaan & Vasey, 2011; VanderLaan et al., 2012). And the relatives on the mother’s side also produce more offspring than do the maternal relatives of heterosexual men. Perhaps the genes that dispose some women to conceive more children with men also dispose some men to be attracted to men (LeVay, 2011). Thus, the decreased reproduction by gay men appears offset by the increased reproduction by their maternal extended family.

Prenatal Influences

Elevated rates of homosexual orientation in identical and fraternal twins suggest an influence not only of shared genes but also a shared prenatal environment. Recall that in the womb, sex hormones direct our development as male or female. In animals and some human cases, prenatal hormone conditions have altered a fetus’ sexual orientation. German researcher Gunter Dorner (1976, 1988) pioneered research on the influence of prenatal hormones by manipulating a fetal rat’s exposure to male hormones, thereby “inverting” its sexual orientation. In other studies, when pregnant sheep were injected with testosterone during a critical period of fetal development, their female offspring later showed homosexual behavior (Money, 1987).

A critical period for the human brain’s neural-hormonal control system may exist during the second trimester (Ellis & Ames, 1987; Garcia-Falgueras & Swaab, 2010; Meyer-Bahlburg, 1995). Exposure to the hormone levels typically experienced by female fetuses during this time appears to predispose the person (whether female or male) to be attracted to males in later life. “Prenatal sex hormones control the sexual differentiation of brain centers involved in sexual behaviors,” notes Simon LeVay (2011, p. 216). Thus, female fetuses most exposed to testosterone appear most likely later to exhibit gender-atypical traits and experience same-sex desires. (For males, prenatal testosterone exposure, given a sufficient minimum amount, seems not to affect sexual orientation [Breedlove, 2017].)

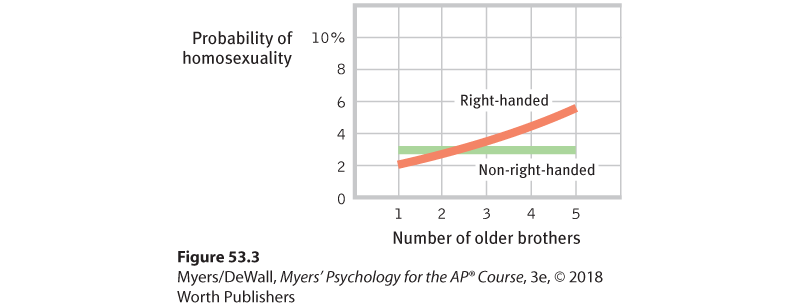

The mother’s immune system may also play a role in the development of sexual orientation. Men with older brothers are somewhat more likely to be gay, report Ray Blanchard (2004, 2008a,b, 2014) and Anthony Bogaert (2003)—about one-third more likely for each additional older brother. If the odds of homosexuality are roughly 2 percent among first sons, they would rise to about 2.6 percent among second sons, 3.5 percent for third sons, and so on for each additional older brother (Bailey et al., 2016; see Figure 53.3).

Figure 53.3 The older brother effect

Researcher Ray Blanchard (2008a) offers these approximate curves depicting a man’s likelihood of homosexuality as a function of the number of biological (not adopted) older brothers he has. This correlation has been found in several studies, but only among right-handed men (as about 9 in 10 men are).

The reason for this curious phenomenon—the older brother or fraternal birth-order effect—is unclear. Blanchard suspects a defensive maternal immune response to foreign substances produced by male fetuses. With each pregnancy with a male fetus, the maternal antibodies may become stronger and may prevent the fetus’ brain from developing in a male-typical pattern. Consistent with this biological explanation, the fraternal birth-order effect occurs only in men with older brothers born to the same mother (whether raised together or not). Sexual orientation is unaffected by adoptive brothers (Bogaert, 2006). The birth-order effect on sexual orientation is not found among women with older sisters, women who were womb-mates of twin brothers, and men who are not right-handed (Rose et al., 2002).

Gay-Straight Trait Differences

Comparing the traits of gay and straight people is akin to comparing the heights of men and women. The average man is taller than most women, but many women are taller than most men. And just as knowing someone’s height doesn’t specify their sex, so also knowing someone’s traits doesn’t tell you their sexual orientation. Yet on several traits, the average homosexual female or male is intermediate between straight females and males (Table 53.1; see also LeVay, 2011; Rahman & Koerting, 2008; Rieger et al., 2016). For example, lesbians’ cochlea and hearing systems develop in a way that is intermediate between those of heterosexual females and heterosexual males, which seems attributable to prenatal hormonal influence (McFadden, 2002). From birth on, gay males tend to be shorter and lighter than straight males, while from birth on, lesbian females tend to be heavier than straight females (Bogaert, 2010; Deputy & Boehmer, 2014; Frisch & Zdravkovic, 2010). Facial structure and fingerprint ridge counts may also differ (Hall & Kimura, 1994; Mustanski et al., 2002; Sanders et al., 2002; Skorska et al., 2015).

| Gay-straight trait differences

Sexual orientation is part of a package of traits. Studies—some in need of replication—indicate that homosexuals and heterosexuals differ in the following biological and behavioral traits:

On average (the evidence is strongest for males), results for gays and lesbians fall between those of straight men and straight women. Three biological influences—brain, genetic, and prenatal—may contribute to these differences. |

Brain differences

|

Genetic influences

|

Prenatal influences

|

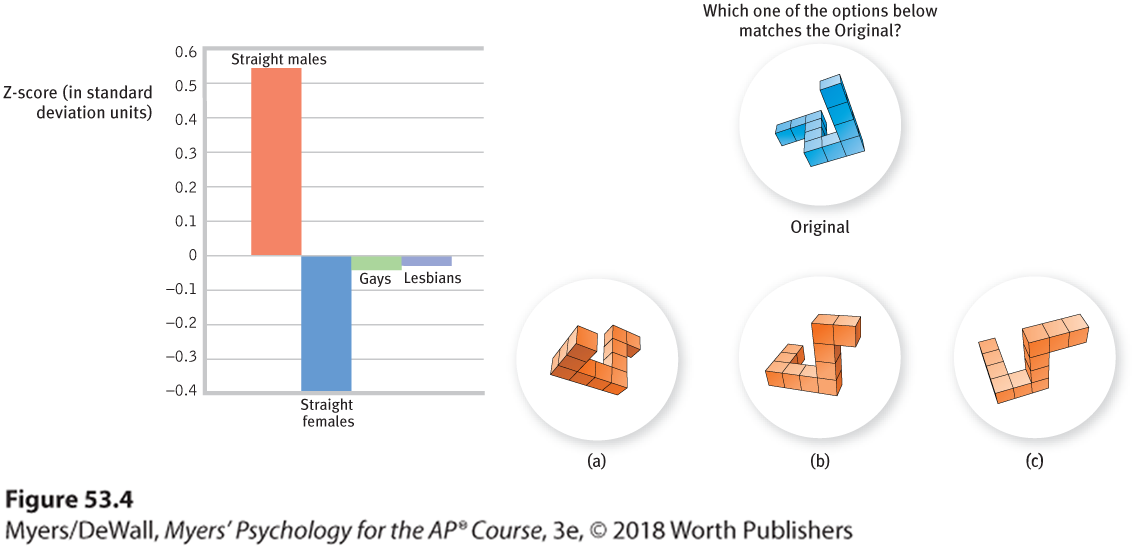

Another you-never-would-have-guessed-it gay-straight difference appears in studies showing that gay men’s spatial abilities resemble those typical of straight women (Cohen, 2002; Gladue, 1994; McCormick & Witelson, 1991; Sanders & Wright, 1997). On mental rotation tasks such as the one illustrated in Figure 53.4, straight men tend to outscore straight women. (So do women who were womb-mates of a male co-twin [Vuoksimaa et al., 2010].) Researchers find that, as on a number of other measures, the scores of gays and lesbians fall between those of heterosexual males and females (Rahman et al., 2004, 2008). But straight women and gays have both outperformed straight men at remembering objects’ spatial locations in memory game tasks (Hassan & Rahman, 2007).

Figure 53.4 Spatial abilities and sexual orientation

Which of the three figures can be rotated to match the original figure at the top? Straight males tend to find this type of mental rotation task easier than do straight females, with gays and lesbians falling in between (Rahman et al., 2004)1.

***

The consistency of the brain, genetic, and prenatal findings has swung the pendulum toward a biological explanation of sexual orientation (Rahman & Wilson, 2003; Rahma & Koerting, 2008). Still, some people wonder: Should the cause of sexual orientation matter? Perhaps it shouldn’t, but people’s assumptions matter. If you see sexual orientation as inborn—as shaped by biological and prenatal influences—then you likely favor “equal rights for homosexual and bisexual people” (Bailey et al., 2016). If you see same-sex attraction as a lifestyle choice or as encouraged by social tolerance, then you likely oppose equal rights for nonheterosexual people. To justify his signing a 2014 bill that made some homosexual acts punishable by life in prison, the president of Uganda, Yoweri Museveni, declared that homosexuality is not inborn but rather is a matter of “choice” (Balter, 2014; Landau et al., 2014).

“ Modern scientific research indicates that sexual orientation is . . . partly determined by genetics, but more specifically by hormonal activity in the womb.”

Glenn Wilson and Qazi Rahman, Born Gay: The Psychobiology of Sex Orientation, 2005

However, the new biological research is a double-edged sword (Roan, 2010). If sexual orientation, like skin color and sex, is genetically influenced, that does offer a rationale for civil rights protection—though not the only rationale, argue rights advocates (Diamond & Rosky, 2016). Yet this research raises the troubling possibility that genetic markers of sexual orientation could someday be identified through fetal testing, that a fetus could be aborted simply for being predisposed to an unwanted orientation, or that hormonal treatment in the womb might engineer a desired orientation.

“ There is no sound scientific evidence that sexual orientation can be changed.”

UK Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2009