Chapter 11

Agile Culture

The disruptions during an industrial revolution are constant. Uber, the original example of a digital disruptor, faces possible disruptions from driverless cars and local ride-sharing companies, not to mention flying taxis. That’s where Stage 5 comes in as the state of staying ahead, or perpetual digital transformation.

The discipline of building an agile culture is a tried and tested approach to facilitate constant reinvention. Adobe, the global software company, is an excellent example of an enterprise that exhibits a constant state of reinvention. It started in the 1980s as a developer of PostScript printing software, moved on to graphics editing with Photoshop, and then built an enviable media and presentation software empire by the early 2000s. In 2013, it reinvented itself from being a digital media and marketing company that sold software packages to one that licensed the capabilities. That move revolutionized the way large software companies sold their products. It continues to evolve into new businesses in ecommerce today.

This business agility rests upon its enviable award-winning corporate culture, as I illustrate with the following example.

How Adobe’s Agility Helps It Evolve Constantly

In 2012, an Adobe executive made a (well-intentioned) mistake39 and ended up turning it into a big win for her company. According to Forbes,40 in March 2012, Adobe’s senior vice president for human resources, Donna Morris, was on a business trip to India. Despite having just arrived and still being a bit jet lagged, she agreed to an interview with an Economic Times reporter. The reporter asked her what she could do to disrupt HR. Morris, who felt strongly about how performance appraisals tend to hurt employee performance, spoke out: “We plan to abolish the annual performance review format.” It was an excellent response, except for one minor detail—she had not talked about this idea yet with the Adobe CEO!

The next day the declaration was on the front page of the newspaper. Morris was aghast. She had to work furiously with the Adobe communications team to post an article on the company’s intranet inviting employees to help assess and change Adobe’s performance evaluation methods as soon as possible.

A culture that is welcoming of new ideas, even to the point of forgiving misplaced enthusiasm, will always evolve faster.

It all worked out perfectly in the end. A few months later, Adobe launched a new performance evaluation process. The formal annual reviews would be replaced by quarterly informal “check-ins.” No paperwork was needed, although the discussions were expected to cover three things—expectations, feedback, and growth and development plans. Not surprisingly, the new process was received enthusiastically. And within two years of launch, Adobe had seen a 30 percent reduction in regretted attrition combined with a 50 percent increase in involuntary attrition of nonperformers. A culture that is welcoming of new ideas (even to the extent of forgiving misplaced enthusiasm) will have the agility to transform perpetually. Adobe has the ingredient of an agile culture necessary to help it transform constantly in the face of repeated disruptions.41

Why Agile Culture Enables Perpetual Digital Transformation

An agile culture, not disruptive technology or new business models, is the ultimate disruption. Yes, I realize that sounds a bit trite, but once that statement is made actionable in the following paragraphs, I believe you’ll agree that it’s worth the risk of sounding trite.

The reason why comments about culture tend to be viewed as unhelpful is because culture is an outcome, not an action. In that context, any statement about culture is likely to be an unhelpful truism. However, based on my research of transformational companies that failed, I have identified that agile culture for perpetual digital transformation includes three sets of disciplined activities—customer-focused innovation, creating an adaptive environment, and establishing a shared common purpose. These provide the necessary outcome for success.

Agile culture in this context may be likened to air density for an airplane. The density of air directly drives the lift generated. At higher altitudes and at higher temperatures, planes work harder to generate lift. There exists a “flight ceiling,” above which an airplane simply won’t fly, because the lift generated would be insufficient for flight. Perpetual digital transformations generate a sufficiently agile culture (air density) to fly over traditional flight ceilings (constant disruptive trends).

The classic place to learn about innovative culture happens to be Silicon Valley. Not surprisingly, this is why corporate “tourism” to Silicon Valley has flourished. Initially, during the dot-com era, what some companies took away from the tours were the external trappings of freedom for their employees—the casual clothing and foosball tables. Over time, this has matured into reapplying entire processes and practices for ongoing innovation and agility. This includes lessons on the three items I mentioned before that, in combination, define an agile culture: customer-focused innovation, creating an adaptive environment, and fostering a shared purpose. To bring this to life, I’d like to use the following three case studies.

Agile culture for Stage 5 transformation = customer-focused innovation + adaptive environment + shared purpose

Zappos: How Customer-Focused Innovation Helps It Stay Ahead

Zappos is widely known for its customer-centric culture. Its dedication to customer service is legendary. Zappos was founded in 1999 under the domain name of ShoeSite.com. A few months later it changed its name to Zappos (based on the Spanish word for shoes, which is zapatos) to facilitate broadening its product range. Working in the highly personal-touch product area of shoe shopping, it defied all odds to hit $1 billion in sales in 2008. Zappos was acquired by Amazon in 2009.

Zappos pioneered and perfected the art of turning personalized customer focus into a winning business model during the early days of online shopping, where online distribution channels struggled to be profitable. Zappos’s fanatical focus on the customer is best exemplified by their distinctive call center service, where agents would go to any length to drive customer satisfaction. Call center agents have no limits on the time spent per call. In one instance recorded in December 2012, a Zappos customer service representative spent a whopping ten hours and twenty-nine minutes with a customer. What was even more remarkable was that the call wasn’t about an order or even a complaint—it was about living in the Las Vegas area! In another example, Zappos earned a customer for life when the individual who was to be the best man at a wedding had his Zappos shoes misplaced by the courier. Zappos not only delivered a replacement overnight at no cost but also upgraded him to VIP status and gave him a full refund.

These examples are not anecdotal; they are the result of deliberate strategy. Zappos takes pains to recruit the right people, hire them mostly at entry level, and build them to be senior leaders within five to seven years. At the call centers, each recruit gets seven weeks of training before they get to the phones. Zappos was deliberate about neutralizing the no-physical-touch disadvantage of online shoe shopping via a business model that was incredibly customer-centric.

There’s one final story that’s worth sharing. Tony Hsieh repeats this frequently. After a night of bar hopping with clients, Hsieh and his clients found themselves back in the hotel room when one client happened to mention that they would have loved to get a pizza. The room service at the hotel was closed for the night. Hsieh suggested that they call the Zappos customer service line. The Zappos rep was initially taken aback but got back very quickly after a few minutes with the names of three nearby pizza shops that were open at that hour and helped place a delivery order for the pizza.42

A culture that puts the customer first will always be more receptive to accepting the changes needed to maintain customer service.

The best bet to keep an enterprise in sync with market disruptions is to foster rock-solid customer focus. To be clear, it doesn’t need to underpin the entire business model, as with Zappos.43 They initially chose customer-centricity to overcome the disadvantages of not having a physical store experience. What Zappos discovered along the way was that a culture that puts the customer first will always be more receptive to accepting changes needed to maintain customer service.

The next case study focuses on how an adaptive environment, or a lack of it, can affect innovation.

Adaptive Culture: Why the New York Times’s Initial Efforts on Digital Transformation Sputtered

In May 2014, an internal report on digital innovation at the venerable New York Times newspaper was leaked. It shared the struggles to adopt new ways of working driven by digital publishing, among other issues. The digital troops were airing their frustration with the gaps in people, processes, and systems that were necessary for the very future of the organization. These highlighted issues of a print-first culture that conflicted directly with the digital era.

For instance, many of the daily reporting and editorial activities were oriented toward finalizing the front page, called A1,44 starting from a 10:00 a.m. meeting, to the early afternoon deadline for reporters to file summaries, to the verdict on which stories made it to the front page. All these activities were more suited to the rhythm of a traditional daily newspaper as opposed to real-time web-based news. The report also called out the need for new systems that were critical for a webfirst future. The Times was behind on its data tagging and structuring. For example, it took the paper seven years to tag “September 11.” The ability for its web readers to “follow” a certain topic was also subpar. All these were systems that were not very important in a print-first world but critical in a digital-first world.

Another issue highlighted was the ability to better understand readers’ needs in the digital world.45 Readers saw capabilities like graphics and interactive as important; the print-centric organization didn’t value it as much. One final example: a digital-first approach needed to pull readers into the story via a comments section. However, the Times had no capability for readers to do that.

More action was demanded on the processes and function of the digital-first teams. For example, many in the newsroom were under the impression that the social media team existed to promote their work while, in reality, that team was originally conceived of as primarily an information-gathering body.

All in all, the systems, processes, and people at the Times seemed to be inadvertently fighting the very change that might ensure their long-term survival. In terms of hearts and minds, the “head” part of the Times understood the need to transform, but the “heart” had trouble adapting to the change. The New York Times has eventually built all these capabilities and more, but other players, including the Washington Post, have been able to overtake them in the process.

There’s one other point worth making based on the New York Times example of culture transformation. Building a transformative culture needs to start early in the transformation. It’s too late to start building transformative culture from scratch after Stage 4 transformation because the seeds of the culture to “stay ahead” belong in the decisions made in the strategy sufficiency discipline area (chapter 8)—especially around intrapreneurship structures.

Our final example of a culture that enables perpetual transformation comes from a source who’s been one of the most prolific disruptive innovators of our time—Elon Musk. In particular, the SpaceX company is a fascinating study because it illustrates the power of a common purpose.

SpaceX: How a Shared Common Purpose Can Drive an Agile Culture

SpaceX founder Elon Musk raised a lot of eyebrows in March 201846 when he shared that SpaceX had no business model when he started it. Neither did his next venture, the Boring Company. In fact, Musk has described starting SpaceX and Tesla, the two companies he’s best known for founding, as possibly “the dumbest things to do” in terms of new ventures.47

The history of SpaceX, like most of Musk’s ventures, is the history of vision, passion, and risk taking prevailing over conventional wisdom. SpaceX has endured many public failures. In 2006, the first SpaceX launch failed thirty-three seconds after liftoff. Its next launch in the following year failed when the rocket did not reach orbit. The year after, SpaceX’s first payload for NASA ended up in the sea and almost killed the company. A 2015 launch destroyed two more NASA payloads meant for the International Space Station, and in 2016 a rocket exploded during refueling.48 All these failures are a feature of Musk’s style that prizes passion over pragmatism.

Understandably, SpaceX has had to pivot on its plans very frequently. The lack of a bigger business model may actually have been a help in those situations. How does SpaceX thrive among this orchestrated chaos?

Examining the traits of the employees that SpaceX hires provides insight into the company’s highly agile culture. At the top of the four qualities they look for is an appetite for exploration. SpaceX is very clear on its mission—they exist to help mankind achieve the goal of colonizing other planets. (The other qualities are passion, drive, and talent.)

SpaceX is a fabulous example of how a common purpose can drive organizations to an agility to persevere in the face of all odds.

The Discipline of Creating an Agile Culture to Stay Ahead

The examples of Zappos, the New York Times, and SpaceX provide insights into what makes for a culture that provides perpetual transformation. The enterprise that facilitates the most change internally has the best chance of constantly evolving. And this constant evolution on a digital backbone of the enterprise prevents it from being a digital one-hit wonder.

It is not a coincidence that the best Silicon Valley enterprises all share these three characteristics. Procter & Gamble’s NGS modeled itself after this. In part III of this book, we will see how this and other disciplines came together to deliver big wins for NGS.

Chapter Summary

![]() Culture eats strategy for breakfast (and apparently lunch, according to another quote). Whatever it consumes, the fact is that for an organization to digest digital transformation, there are three specific behaviors that will enable an agile culture necessary to create a living DNA of perpetual digital transformation: customer-focused innovation, an adaptive environment, and a shared common purpose.

Culture eats strategy for breakfast (and apparently lunch, according to another quote). Whatever it consumes, the fact is that for an organization to digest digital transformation, there are three specific behaviors that will enable an agile culture necessary to create a living DNA of perpetual digital transformation: customer-focused innovation, an adaptive environment, and a shared common purpose.

![]() Building an agile culture must start early in the digital transformation process. It’s too late to start after Stage 4, although it must be completed before Stage 5.

Building an agile culture must start early in the digital transformation process. It’s too late to start after Stage 4, although it must be completed before Stage 5.

![]() The lessons from successful Silicon Valley companies such as Zappos have proved how culture plays a hugely disproportionate role in fostering transformation through customer-focused innovation.

The lessons from successful Silicon Valley companies such as Zappos have proved how culture plays a hugely disproportionate role in fostering transformation through customer-focused innovation.

![]() The leaked New York Times internal memo of 2014 on the paper’s digital transformation challenges demonstrates that missing an adaptive culture can significantly slow down the natural momentum of the organization and resist digital transformation.

The leaked New York Times internal memo of 2014 on the paper’s digital transformation challenges demonstrates that missing an adaptive culture can significantly slow down the natural momentum of the organization and resist digital transformation.

![]() The remarkable story of SpaceX and how it continues to break paradigms in its attempt to put humans on other planets is a clear case for purpose-driven agility.

The remarkable story of SpaceX and how it continues to break paradigms in its attempt to put humans on other planets is a clear case for purpose-driven agility.

Your Disciplines Checklist

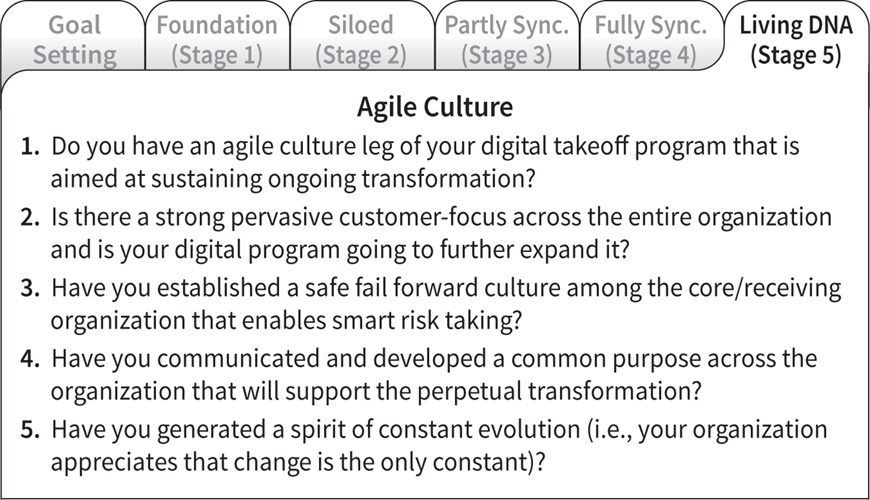

Evaluate your digital transformation against the questions in figure 24 to follow a disciplined approach to each step in Digital Transformation 5.0.

Figure 24 Your disciplines checklist for agile culture