Chapter 8

Strategy Sufficiency

I discovered a passion for stock market trading six months before the big dot-com crash in March 2000. Online trading tools were growing dramatically in capability. I tentatively bought a few tech stocks, and within a few weeks they had doubled in value. Hmm, I thought, that’s encouraging; I should invest some more. I knew the looming risks of a market downturn and so decided on a couple of mutual funds instead of individual stocks for my next investment, which was much bigger. Three months later, the dot-com bubble burst and my total holding ended up at about half the value of my original investments. The mutual funds hadn’t been diverse enough. Thankfully, I hadn’t put too much into the stock market in total. However, it was still a painful lesson on the virtues of portfolio management.

Good financial portfolio management, as you know, starts with a targeted goal for return on investment by a specified end date. And then it involves creating a mix of diversified holdings, including high-, medium-, and low-risk components, to maximize the chance of hitting the goal, despite headwinds and economic cycles. It’s a proven model that works for retail investors. Which leads us to a more relevant question: Why don’t most digital transformations run as disciplined portfolios too?

Digital Transformation Portfolio Sufficiency

The financial portfolio management discipline applies to digital transformation perfectly. It is possible to define an end goal, such as a certain percentage of your business being run on totally new digital business models by a given date. Next, leverage the mix effect by combining high- and low-risk projects optimally. And finally, generate a sufficient number of projects to run through this portfolio—enough to transform the desired percentage of your enterprise. I call this approach “strategy sufficiency.”

The NGS portfolio process was designed exactly this way and will be described at the end of the chapter. First, it would help to reflect on why we don’t see more examples of strategy sufficiency. The short answer is that there can be a misguided emphasis on driving change enthusiasm in the organization without the requisite portfolio rigor.

Innovation Theater Is the Enemy of Strategy Sufficiency

The discipline of checking for both a sufficient portfolio mix and the requisite volume of projects is at the core of strategy sufficiency. The opposite of this is a plan that relies too heavily on sheer enthusiasm. Don’t get me wrong—enthusiasm about change is vital. Where things start to fall apart is when it is not backed up by disciplined execution. If a digital transformation seems a bit heavy on any of the following six activities, then it might be time to bring in the rigor.

![]() Silicon Valley’s Mecca tours—a few days spent in business-casual dress marveling at the magical offerings of start-ups. Or spent in the glassed-in innovation centers of the larger tech companies offering “inspiration workshops” on your problems.

Silicon Valley’s Mecca tours—a few days spent in business-casual dress marveling at the magical offerings of start-ups. Or spent in the glassed-in innovation centers of the larger tech companies offering “inspiration workshops” on your problems.

![]() Lonely innovation planet outpost—staffing a few people in global innovation hub locations, free from the stifling headquarters bureaucracy, but quickly forgotten or ignored by the core organization.

Lonely innovation planet outpost—staffing a few people in global innovation hub locations, free from the stifling headquarters bureaucracy, but quickly forgotten or ignored by the core organization.

![]() Internal crowdsourcing drama—the earnest attempts to collect innovation ideas from within the company, or the attempted one-off hackathons, without the wherewithal to execute them.

Internal crowdsourcing drama—the earnest attempts to collect innovation ideas from within the company, or the attempted one-off hackathons, without the wherewithal to execute them.

![]() Outsourced innovation delusion—the hiring of highly paid consultants to take accountability for inspiration, iterative execution, and external solution connections. It’s a start, except that true perpetual transformation cannot be outsourced.

Outsourced innovation delusion—the hiring of highly paid consultants to take accountability for inspiration, iterative execution, and external solution connections. It’s a start, except that true perpetual transformation cannot be outsourced.

![]() Labs for chasing cool technologies—the misguided attempt to focus on shiny object technologies without clarity on the problems to be solved.

Labs for chasing cool technologies—the misguided attempt to focus on shiny object technologies without clarity on the problems to be solved.

![]() Highly delegated souls innovation group—the group of junior resources flailing in their attempt to do their best to drive the hardest of changes in the company.

Highly delegated souls innovation group—the group of junior resources flailing in their attempt to do their best to drive the hardest of changes in the company.

Granted, elements of these tactics have a role to play in a successful disruptive transformation program. However, the haphazard application of these tactics does not lead to a sufficient strategy for digital transformation.

Innovation theater is the opposite of strategy sufficiency.

What delivers strategy sufficiency is a strong portfolio mix and the right input project volume, which I expand upon in the coming sections using the examples of Alphabet/Google for portfolio mix and the Virgin Group for generating the right volume of input ideas. These are organizations to which a fertile innovation culture comes natively. Somewhere along their early growth cycle, they recognized that their best business strategy was one of constant change. How they got there isn’t important. We just need to unbundle their discipline and get to the essence that can be transplanted into other organizations.

Alphabet/Google’s Formula for a Sufficient Mix of Transformative Ideas

Google has always had an entrepreneurial mindset as its lifeblood since inception, but ex-CEO Eric Schmidt gets credit for making transformation systemic via a portfolio mix of work that includes big-bet ideas and incremental improvement ideas in addition to daily operations.

A healthy mix is important—if the list of ideas is weighted too heavily toward incremental change or toward highly risky ideas, the outcome degrades. A good mix includes ideas that improve daily operations, those that enable continuous evolution, and game-changing disruptive ideas, or 10X as they are called, for delivering ten times the impact as opposed to 10 percent improvements. Eric Schmidt advocated for a mix of these, roughly in the 70-20-10 ratio.

The 70-20-10 Mix for Sufficiency of Transformation

The formula that Google came up with is a 70-20-10 ratio of employee capacity for innovation.30 Specifically,

![]() 70 percent of people’s capacity is dedicated to core business

70 percent of people’s capacity is dedicated to core business

![]() 20 percent of their capacity is related to a core project

20 percent of their capacity is related to a core project

![]() 10 percent of their capacity is spent on unrelated new businesses

10 percent of their capacity is spent on unrelated new businesses

The key was to create a platform where employees could take systemic risks, thrive in ambiguity, and be encouraged to come up with prototypes rather than slides. Ideas had to be original. The culture had to promote “yes” rather than “no.” It had to feed the core business while also encouraging hugely disruptive 10X ideas.

Setting up and professionally managing a sufficient portfolio of projects delivers sufficient and scaled digital transformation.

To be clear, the 70-20-10 ratio isn’t a universal formula for all innovation portfolios. The generic idea, however, has sound roots. In a Harvard Business Review article in May 2012 titled “Managing Your Innovation Portfolio,”31 Geoff Tuff and Bansi Nagji reported that a study of companies in the manufacturing, technology, and consumer goods sectors revealed that those that allocated 70 percent of their innovation activity to core initiatives, 20 percent to adjacent ones, and 10 percent to transformational ones outperformed their peers via a price-to-earnings premium of 10 to 20 percent. What these organizations were able to do was not just strike the ideal balance of core, adjacent, and transformational initiatives but also implement tools and capabilities to manage those various initiatives as part of an integrated whole.

How to Focus on the 10 in the 70-20-10 Model

Executing innovations in the 70 and 20 parts of the 70-20-10 model is well understood. It’s the disruptive innovation work (i.e., the 10 in the 70-20-10) that requires a very different mindset and therefore new discipline. This is where the concept, popularized by Alphabet—moon-shot thinking—is useful. The term “moonshot thinking” comes from the original challenge from President John F. Kennedy to go to the moon. It advocates for ideas that deliver ten times the impact (10X) instead of incremental ones. The Alphabet company X (previously called Google X) is the main proponent of this type of thinking. X has claimed that sometimes it is easier to make something ten times better than to improve it 10 percent. While that may be controversial, the point is that going after a 10X improvement demands breaking all existing paradigms about the problem. Anything else leads to incremental thinking. Thus, 10X is a great framework to separate incremental thinking from disruptive thinking. The rewards for getting a disruptive idea right can be huge. For instance, Alphabet/Google’s driverless car company, Waymo, has been valued at over $100 billion by UBS.

The Volume Part of Strategy Sufficiency

A good portfolio mix in your personal financial investment plan helps optimize risk. However, whether the plan generates enough returns for you to, say, retire comfortably depends on how much you invest into the plan. This “volume of input” has a parallel in digital transformation as well, i.e., how many ideas and projects are being funneled into the transformation effort. The systemic generation of enough transformation projects (i.e., beyond generating ideas) is foundational to generating enough fuel for sufficient transformation. There are many approaches to generating these ideas for projects, but the one that I like the most, because it also helps change the culture of the entire organization, is “intrapreneurship,” a system for employing the practices of entrepreneurship within a large organization.

Targeted intrapreneurship can generate enough transformation projects (i.e., fuel) for sufficient transformation.

To be clear, intrapreneurship without the rest of the disciplines of digital transformation produces little fruit. However, when supported by the rest of the disciplines of digital transformation, it is a powerful tool. Many well-known iconic products have come from intrapreneurship programs within some of the world’s leading companies, including:

![]() DLP (Digital Light Processing) technology—Texas Instruments

DLP (Digital Light Processing) technology—Texas Instruments

![]() Elixir guitar strings—W. L. Gore

Elixir guitar strings—W. L. Gore

![]() Gmail—Google

Gmail—Google

![]() Post-it Notes—3M

Post-it Notes—3M

![]() Java programming language—Sun Microsystems

Java programming language—Sun Microsystems

![]() PlayStation—Sony

PlayStation—Sony

![]() in-store health clinics—Walmart

in-store health clinics—Walmart

![]() several movie scripts—DreamWorks

several movie scripts—DreamWorks

But the example of intrapreneurship that I find most striking is Virgin Group. Sir Richard Branson, the founder of Virgin Group, is a strong proponent of disciplined transformation led via intrapreneurship.

The Virgin Group’s Approach to Intrapreneurship

By most objective metrics, Sir Richard Branson has been a highly successful serial entrepreneur. His Virgin Group has spawned more than five hundred companies and currently holds more than two hundred. For a group that has been in existence less than five decades, that’s a remarkable record.

It is the sheer breadth of industries in the holding and the success rates in business that is fascinating. How does the Virgin Group drive consistency across such varied businesses? In an article for Entrepreneur magazine, Branson talked about the importance of intrapreneurship in driving perpetual transformation in the group. “What if CEO stood for ‘chief enabling officer’? What if that CEO’s primary role were to nurture a breed of intrapreneurs who would grow into tomorrow’s entrepreneurs?” Branson admits that Virgin has stumbled onto this model because when they entered businesses in which they had very little knowledge, they had to enable a few select people who knew what they were doing. The intrapreneurship model has clearly paid off for Virgin.

Virgin’s processes are highly conducive to intrapreneurship, with disciplined communications, training, and ideation processes designed to generate internal ideas. Several of Virgin’s innovations, including the herringbone design of business-class seats in commercial airliners that give each flyer a sleeper aisle seat, owe their existence to Virgin’s intrapreneurship program (see sidebar). The Virgin Group’s culture mirrors the style of its founder. Branson is a known enabler who firmly believes in empowering his people to make decisions. He has some fundamental business principles, one of them being to protect the downside. Another principle is to have fun in your business. Branson uses this as a criterion for choosing which businesses to enter. The disciplined processes to gather innovations based on these principles bottom-up, and then mash them up with top-down strategy, serves as a powerful source of constant change at Virgin32,33,34 as demonstrated by their innovation record.

There’s another side benefit of the intrapreneurial culture of Virgin. It also serves to propagate a culture of ongoing change acceptance. I will return to this point in chapter 11, “Agile Culture.”

Strategy Sufficiency at Procter & Gamble’s NGS

One of the lessons learned from past attempts to set up innovation in GBS was that having a handful of big-hitter ideas doesn’t make for a disciplined and sufficient portfolio of outcomes. Therefore, we needed to address both the “right mix” and the “right volume” issues for sustainable transformation. We looked at various options and eventually set up NGS to focus only on 10X disruptive change experiments (projects), while the core organization would drive continuous improvements, i.e., the 70 and the 20 in the 70-20-10 model. Recognizing that 10X disruptions require different processes and reward systems than those in normal operations, this split made sense. It allowed us to implement different designs for rewards, recognition, and risk management in NGS that would be different from the rest of the company.

For instance, one example of how we cultivated and supported high-risk, high-return projects was by creating new terminology. The term “projects” was replaced by “experiments.” Projects come with an expectation of success, whereas experiments convey a riskier proposition to the core organization.

Another example of a process to cultivate moonshot behavior was the composition of the NGS portfolio itself. We came up with the strategy of 10-5-4-1, which I mentioned previously. That ratio was based on what some venture capitalists do within their portfolios, and it worked for NGS too.

The volume part of strategy sufficiency was addressed by leveraging our vast ecosystem of internal and external resources to generate hundreds of ideas. Put together, the way NGS’s strategy sufficiency worked was simple—the internal and external ecosystems generated a large number of ideas (which were always in response to a strategic GBS opportunity area). Of these, in a given year we might pick ten to turn into formal experiments. And then the 10-5-4-1 ratio was applied in execution.

Chapter Summary

![]() For sufficient digital transformation, it’s important to distinguish between anecdotal success stories and systemic transformation. A sustainable digital transformation draws on a large number of innovation ideas and then processes them efficiently to kill most of them. Strategy sufficiency therefore includes the ability to generate sufficiency in terms of numbers of ideas as well as the portfolio sufficiency to turn some of them into major successes.

For sufficient digital transformation, it’s important to distinguish between anecdotal success stories and systemic transformation. A sustainable digital transformation draws on a large number of innovation ideas and then processes them efficiently to kill most of them. Strategy sufficiency therefore includes the ability to generate sufficiency in terms of numbers of ideas as well as the portfolio sufficiency to turn some of them into major successes.

![]() Running effective portfolios such as the 70-20-10 model can help in making digital transformation plans sustainable.

Running effective portfolios such as the 70-20-10 model can help in making digital transformation plans sustainable.

![]() Within the 70-20-10 mix, moonshot thinking, or the 10X approach, is a powerful tool to generate ideas for the 10 segment.

Within the 70-20-10 mix, moonshot thinking, or the 10X approach, is a powerful tool to generate ideas for the 10 segment.

![]() Intrapreneurship programs are a great mechanism to generate sufficient numbers of ideas.

Intrapreneurship programs are a great mechanism to generate sufficient numbers of ideas.

Your Disciplines Checklist

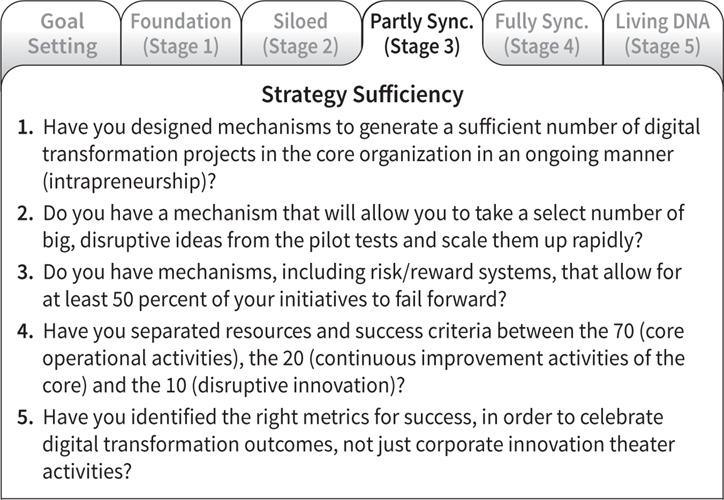

Evaluate your digital transformation against the questions in figure 18 to follow a disciplined approach to each step in Digital Transformation 5.0.

Figure 18 Your disciplines checklist for strategy sufficiency