On December 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.

On December 11, Japan’s European ally Germany declared war on the United States. The United States was at war, and the war began with a massive military setback. On December 8, Dr. Seuss published his first cartoon reacting to the changed situation.28 (The number in the margin gives the page on which the cartoon appears.) It did not show Japan or Pearl Harbor. Instead, it showed a bird, “Isolationism,” demolished by an explosion, “WAR.” For months before December 7 “isolationism” and “isolationists” had been Dr. Seuss’s targets. Dr. Seuss (and PM) had long wanted the United States to intervene in the European war. Editor Ralph Ingersoll named “Professional Isolationists” as “American Enemies of Democracy” (note the capital letters). Pearl Harbor did not change Dr. Seuss’s campaign against these domestic enemies embodied by Charles A. Lindbergh, the America First movement, and Father Charles Coughlin; anti-black racists and anti-Semites; and the opponents of New Deal social programs.

Hitler was the most frequent subject of Dr. Seuss’s wartime editorial cartoons, but Charles A. Lindbergh came in second, at least for the year 1941. Lindbergh was the first person to fly solo across the Atlantic, a feat that stunned the world in 1927 and turned him into an authentic international hero. In the 1930s, however, Lindbergh spoke in admiring tones of Hitler’s regime, and in early 1941 Lindbergh joined the anti-interventionist organization America First and began speaking out against the interventionist steps of the Roosevelt administration, notably the Lend-Lease Act. On September 11, 1941, in Des Moines, Iowa, Lindbergh made a speech in which he made a distinction between the “Jewish race” and “Americans.” That speech included these sentences:

I am not attacking either the Jewish or the British people. Both races I admire. But I am saying that the leaders of both the British and Jewish races, for reasons which are understandable from their viewpoint as they are inadvisable from ours, for reasons which are not American, wish to involve us in the war. We cannot blame them for looking out for what they believe to be their own interests, but we must look out for ours. We cannot allow the natural passions and prejudices of other peoples to lead our country to destruction.

The charge of anti-Semitism has stuck to Lindbergh’s name ever since, and it served to discredit as well the “isolationist” cause to which he had lent his prestige.

I keep “isolationist” in quotation marks because, as in the Ingersoll position paper, it is a rhetorical label that simplifies a highly complex phenomenon. Those opposing American involvement in the war in Europe did so with a variety of motives. Some were pacifists. Others looked back to Versailles and the harsh peace it imposed on Germany; these people saw a part of Hitler’s foreign policy as a reaction to Versailles and thus were reluctant to endorse sharp criticism of it. Others distrusted great-power politics of any kind, but particularly support for Britain and the British empire. Others feared the changes war would bring to the United States. Still others distrusted President Roosevelt. The “anti-isolationists” or “interventionists” read the situation differently: that Hitler and Nazi Germany were a threat not simply to Germany’s European neighbors but to civilization, that aiding Britain would enable Britain to fight on, that a British collapse would leave the United States alone in a hostile world. However, those advocating this position, as PM did, labored under the difficulty that for political reasons the Roosevelt administration had to camouflage its desire to intervene in the war in Europe.

Between “isolationists” and those advocating intervention lay a large divide. In Second Chance: The Triumph of Internationalism in America During World War II, a book critical of “isolation,” Robert A. Divine suggests that the “internationalists” (proponents since Wilsonian times of an active role for the United States in international affairs) were a relatively homogeneous group. He lists these characteristics:

Virtually all were old-stock Protestant Americans. Descendants of English and Scottish settlers, they were Anglophiles who believed that the United States had inherited England’s role as arbiter of world affairs. As representatives of a social class that had taken on many of the characteristics of a caste, they showed little sympathy for the plight of colonial peoples. The world they wanted to save was limited to Europe and its overseas possessions; they took Latin America for granted and neglected the Orient. Bankers, lawyers, editors, professors, and ministers predominated; there were few salesmen or clerks and no workmen in their ranks. The business community was represented by men who dealt in the world markets.... Small manufacturers, real-estate brokers, and insurance executives were conspicuously absent. Above all, the internationalists lived in the Northeast, with only isolated cells scattered through the provinces in university towns and such cosmopolitan centers as San Francisco and New Orleans.

In more recent times in the United States, the leading “internationalist” organizations—the Foreign Policy Association, the Council on Foreign Relations, and later the Trilateral Commission—have come under attack. The times have changed, but the fault line endures.

Complicating the picture for President Roosevelt was the fact that key parts of his electoral base—Southerners and Irish Americans—were generally against intervention, at least early on. But that was not a concern for PM and Dr. Seuss. In their biography of Dr. Seuss, Dr. Seuss and Mr. Geisel, Judith and Neil Morgan report that Dr. Seuss had written a bit of doggerel about Lindbergh and hung it on his studio wall. It speaks of Lindbergh’s having flown the Atlantic “With fortitude and a ham sandwich” but concluded that Lindbergh “shivered and shook/At the sound of the gruff German landgwich.” By the time of Pearl Harbor, Dr. Seuss had depicted Lindbergh in a dozen cartoons. On April 28, 1941, Dr. Seuss drew “The Lindbergh Quarter,” which includes the ostrich that becomes Dr. Seuss’s representation of “isolationism.”29 This is the bird that the explosion of war blows up into the air on December 8. This was not an innovation. Dr. Seuss had drawn an ostrich with its head in the sand before the war. Then the issue was “Sex, sex, everywhere Sex! Even ostriches hiding their heads have ulterior motives.” Nor was the image new in the national debate: in his State of the Union speech of January 3, 1940, President Roosevelt had said, “I hope that we shall have fewer ostriches in our midst. It is not good for the ultimate health of ostriches to bury their heads in the sand.” But Dr. Seuss was to put it to good use. On April 29, Dr. Seuss drew smiling simpletons lining up to don “ostrich bonnets” offered by the “Lindy Ostrich Service, Inc.”30

In mid-May 1941, Dr. Seuss depicted Uncle Sam happily in a separate bed from Europe with its contagious diseases: “Stalin-itch, Hitler-itis, Blitz Pox, Nazi Fever, Fascist Fever, Italian Mumps.”31 The latter had killed the cat stretched out beneath the bed labeled “Europe.” Later that same month Dr. Seuss depicted Uncle Sam sitting atop a nest in a forest with only one other tree still standing.32 Trees labeled Poland, France, Holland, Norway, Greece, Jugoslavia, and “etc.” have fallen victim to the assault of a woodpecker with the face of Hitler and a ferocious beak. The only other tree left is England, and the woodpecker has already cut its trunk halfway through. Says Uncle Sam, “Ho hum! When he’s finished pecking down that last tree he’ll quite likely be tired.”

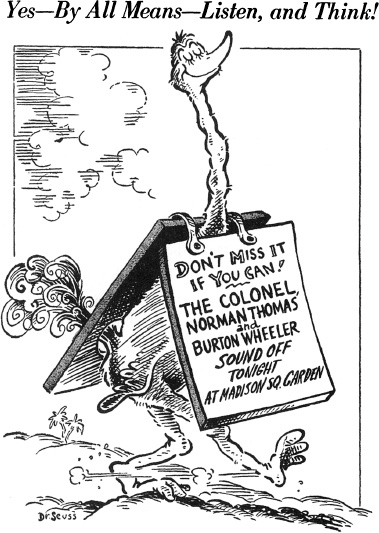

A drawing of May 23 urged people to listen to radio coverage of an event at Madison Square Garden featuring Lindbergh (“the Colonel”), the socialist Norman Thomas, and Senator Burton Wheeler. The drawing is Dr. Seuss’s, but the note underneath must have come from the editor: “PM isn’t in the habit of drumming up listeners for appeasement meetings. But sometimes it is worth listening to people just to note what they don’t say.” The questions PM wanted the “isolationists” to answer were these: “If Britain is defeated, do you think we will have more democracy, or less, in the U. S. A.? If Britain is defeated, do you think the U. S. A. will be more secure, or less, from attack by Hitler? Which will bring militarism more quickly to the U. S. A., and make it last longer—a British victory or a Hitler victory?” The notice concluded: “If Lindbergh, Wheeler, and Thomas fail to answer these simple questions, it doesn’t matter much what else they may say. Because in the answers to these questions lie the real issues facing America today.” This cartoon raises a question I cannot answer: Did Dr. Seuss draw his editorial cartoons to order? Or did he have free rein? This drawing and several others appear to have been specifically commissioned, but often there is no immediate connection between Dr. Seuss’s editorial cartoon and the rest of the editorial page.

A cartoon in late May showed a blithe “America First” lolling in a bathtub labeled “American hemisphere.”33 With him in the tub are a crocodile, a shark, an octopus, and a lobster, all wearing swastikas. Note the drainpipe with its leak and the right rear leg of the tub (well off the floor). On May 29, Lindbergh made a speech in which he stated: “Mr. Roosevelt claims that Hitler desires to dominate the world. But it is Mr. Roosevelt who advocates world domination when he says it is our business to control the wars of Europe and Asia, and that we in America must dominate islands lying off the African coast.” (Lindbergh’s reference was to Fernando de Noronha, an island off the coast of Brazil, not Africa). Lindbergh called for “new policies and new leadership.” Dr. Seuss responded on June 2: in his cartoon of that date Lindbergh pats a Nazi dragon on the head while warning against Roosevelt.34 Dr. Seuss further developed these ideas early in July in a cartoon not included in this volume. In the cartoon a flock of ostriches parades with a sign “Lindbergh for President in 1944!” while an ominous hooded figure (“U. S. fascists”) skulks behind, carrying a smaller sign: “Yeah, but why wait till 1944?”

On June 9, Dr. Seuss depicted Hitler as an artist. (Of course, Hitler was a failed artist.35) He is at work on a portrait of a female “Germania” surrounded by the torch of truth, a dove of peace, and a happy workman; she sits atop a volume labeled “Law,” and across her ample bosom is the word “Plenty.” Note the two Hitler-faced putti with haloes. John Cudahy was a Democrat who had served as ambassador to Belgium (1939–1940). A hardline opponent of the Soviet Union, Cudahy went to Germany and interviewed Hitler; the interview appeared in the New York Times in early June 1941. In an editorial PM characterized the incident as “boosting Nazi propaganda.”

Two days later, Dr. Seuss drew “By the Way...Did Anyone Send that Aid to Britain?” Eight old men sit around a table; the calendar on the wall read 1951, ten years in the future.36 The men have long beards, are festooned with cobwebs, and their beards intertwine. Even the cat has a beard. A skeptic might ask: If the ten years between 1941 and 1951 have not brought Nazi victory, why the worry? But short-term delay, not long-term outcome, is Dr. Seuss’s point here. In late June, an unhappy “America First” tries to blunt the thorns of a cactus labeled “Stiffening U. S. Foreign Policy.”37 (Count the steps on the impossible stepladder!) In July, Dr. Seuss drew two cartoons under the title, “The Great U. S. Sideshow”; both show freaks of nature. One (July 3, not included in this volume) shows a literally gutless “Appeaser” —there is nothing at all between his front and back suspenders. In the other (July 8), “America First” and a Nazi are joined at the beard.38 This was a theme Dr. Seuss and PM emphasized: connections between “isolationists” in the United States and the enemies abroad—fascism and Nazism.

On July 16, Dr. Seuss drew a happy whale on a mountain-top chortling: “I’m saving my scalp/Living high on an Alp.../(Dear Lindy! He gave me the notion!)” Particularly in 1941 Dr. Seuss incorporated rhymes and puns into his cartoons.39 The first of these (not included here) came in June and showed “Uncle Sam” at home (“Home Sweet Home”) in his armchair, feet up on a hassock, glass with straw in it on a table by his side, blithely ignoring a “blitz”: “Said a bird in the midst of a Blitz,/”Up to now they’ve scored very few hitz,/So I’ll sit on my canny/Old Star Spangled Fanny...’/And on it he sitz and he sitz.”

There are others. On July 18 (a cartoon not included in this volume), two isolationist clams commented on the dangers of the Atlantic Ocean: “Cried a clam with an agonized shout,/‘Don’t be so aggressive, you lout!/That’s Hitler’s Atlantic;/You’ll make the man frantic!/Good gracious, don’t stick your Neck Out’!” And in August a limerick accompanies a cartoon of Stalin knitting.167 But that was the last. Perhaps indicating Dr. Seuss’s maturation as an editorial cartoonist, he later was to de-emphasize words and focus instead on balancing words and image.

On an August cover, “The Appeaser” (is it Lindbergh?) offers lollipops to Nazi dragons.40 A September cartoon has Lindbergh attempting to mate the American eagle and a jellyfish.41 (Note that the jellyfish has eyes — two of them; note also the beards and mustaches of the learned audience.) In September, “America First” assures Uncle Sam, as they stand beside a railroad track, that the Nazi express roaring toward them will turn off onto a very flimsy “Appeasement Junction.”42 Lindbergh made his Des Moines speech, on September 11. One week later, in “Spreading the Lovely Goebbels Stuff,” Dr. Seuss draws Lindbergh atop a “Nazi Anti-Semite Stink Wagon.”43 (Paul Joseph Goebbels was Hitler’s Minister of Propaganda.) On September 26 Dr. Seuss drew “Appeaser’s Mirror,” a critique of defeatism: a fun house mirror—”Take one look at yourself and despair!”—gives a healthy Uncle Sam a black eye, a long beard, and a crutch.44 On October 1, a mother labeled “America First” reads the tale of “Adolf the Wolf” to her frightened children; she reassures them: “...and the wolf chewed up the children and spit out their bones... But those were Foreign Children and it really didn’t matter.”45

Four days later—two full months before Pearl Harbor—came the hilarious “I was weak and run-down.”46 Before: “I had circles under my eyes. My tail drooped. I had a foul case of Appeasement... THEN I LEARNED ABOUT ‘GUTS’ that amazing remedy For all Mankind’s Woes.” After: “I FEEL STRONG ENOUGH TO PUNCH MISTER HITLER RIGHT IN THE SNOOT!”

Senator Burton Wheeler (D-Montana) was a staunch opponent of intervention. On October 17, he said: “I can’t conceive of Japan being crazy enough to want to go to war with us.” One month later, he added: “If we go to war with Japan, the only reason will be to help England.” On November 7, to pillory Wheeler, Dr. Seuss invoked the story of Admiral George Dewey, the American hero of the battle of Manila Bay in the Spanish-American War.47 Dewey was the attacker, and he became famous for saying to the captain of his flagship: “You may fire when you are ready, Gridley.” Dr. Seuss’s admiral is Wheeler, and he speaks from the bottom of the ocean; a torpedo has blown out the port side of his flagship. The Nazi sub that did the deed lurks not far away as Wheeler fulminates: “You may fire when I am damn good and ready, Gridley.” At the end of November—still before Pearl Harbor—Dr. Seuss relegates “Isolationism” to a museum along with a pair of dinosaurs.48

In early 1942, PM launched a campaign to convince the government to act against the anti-Semitic Roman Catholic priest Charles E. Coughlin. Coughlin had a radio show and published a magazine, Social Justice, that PM wanted banned from the U. S. mail. On March 30, PM printed a ten-page attack on Father Coughlin that included a ballot for readers to sign and mail to the attorney general. In April Social Justice was banned from the mail for violating the Espionage Act of 1942. As Paul Milkman comments, “PM’s zeal to silence the fascist and pro-fascist mouthpieces shows an alarming absence of concern for civil liberties.” Dr. Seuss contributed a number of cartoons to this campaign.49 On February 9, 1942, he drew “Still Cooking with Goebbels Gas.” Earlier he had linked Lindbergh and Goebbels; here it is Coughlin and Goebbels and “The same old Down-with-England-and-Roosevelt Stew.” On March 23, “Vater Coughlin” appears as engineer on “The Berlin-Tokyo Rome + Detroit” railroad, pulling freight cars loaded with “Axis propaganda.”50 (Coughlin’s home base was just outside Detroit.) Note the swastika on the front of the locomotive and the steam that blasts the unfortunate onlooker in the face. On March 30, he had Hitler himself reading Social Justice and phoning Coughlin: “Not bad, Coughlin...but when are you going to start printing it in German?”51

Few of Dr. Seuss’s editorial cartoons dealt with the postwar world. When his last editorial cartoon appeared in January 1943, the end of the war was still more than two years off. But beginning at the end of August 1942, Dr. Seuss did plan the peace or at least restate his opposition to American “isolationism.” In August, he ridiculed “The Gopher Hole of Isolation.”52 Then came five cartoons dedicated to this theme in December 1942 (of twenty-one in all) and one in January 1943 (of four). We don’t know the date on which Dr. Seuss decided to leave PM, but in his last five weeks, the fight against “isolationism” was very much on his mind. On December 14, a giant Uncle Sam was shown watching tiny figures at work on FOUNDATIONS FOR POST-WAR ISOLATIONISM.53 A huge sign read: “DANGER! SMALL MEN AT WORK!” In a Christmas Day cartoon, a man peeks out from a shelter after the cyclone of war has passed; the title, “With a Whole World to Rebuild...” underlines the pettiness of the shelter-dweller, who thinks only of patching up his fence, labeled “ISOLATION.”54 Finally, on New Year’s Day 1942, Dr. Seuss depicted a seedy gentleman labeled “REACTION” offering an “Isolation Lollipop” to Baby 1943.55 Dr. Seuss may not have drawn the postwar settlement, but he went on record against U. S. “isolationism.”

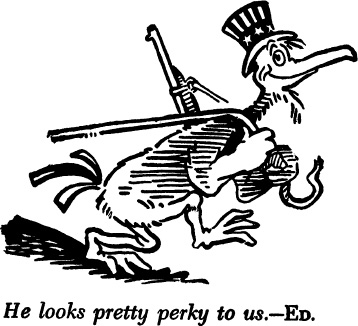

As we have seen, Dr. Seuss portrayed the United States in two ways: as human Uncle Sam and as bird. Uncle Sam wears a bow tie, cutaway, striped pants, and top hat; unlike Dr. Seuss’s other top hats (on the heads of folks he is ridiculing), this hat has stars around the band and vertical stripes. The bird—witness the cartoon showing Lindbergh attempting to crossbreed eagle and jellyfish—is an eagle, though bird lovers may be forgiven if they don’t recognize it as such.41 And note that the eagle’s wings often end, virtually, in fingers. Dr. Seuss’s use of this bird to represent the United States drew a rebuke from one reader, who complained in a letter to the editor (December 18, 1941): “Much as I admire and appreciate the work of Dr. Seuss, I question the fitness of continuing to picture our Uncle Sam as an ostrich. At least he should be transformed into an Eagle.” Without correcting the reader’s misapprehension, Ralph Ingersoll reprinted one of Dr. Seuss’s Uncle Sams and this sentence: “He looks pretty perky to us.”

Dr. Seuss never drew President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. His representations of the United States were Uncle Sam and an eagle, and, sometimes, in a sense “YOU + ME.” Dr. Seuss idolized Roosevelt. He quoted Roosevelt and honored him by conferring on him the first membership in his imaginary “Society of Red Tape Cutters,” as we will see. But he never drew Roosevelt.188 It is not that Roosevelt was not suitable material for caricature: before and during the war American cartoonists often depicted him, jaunty demeanor, cigarette in holder at a confident angle, and—despite the fact that in real life he was confined to a wheelchair—often standing or striding. But Dr. Seuss’s United States is always an idealized figure distinct from its president. In the next chapters we will contrast that treatment with Dr. Seuss’s treatment of Germany, Italy, and Japan.

In American society in the early 1940s, relations among the races—primarily, black-white relations—were rocky at best. During the 1930s, there were on average more than ten lynchings per year. Jim Crow laws were in place throughout the country. The U. S. military was still segregated, as were schools and major league baseball. In 1943, riots paralyzed northern cities when black workers joined assembly lines that had been all-white.

Dr. Seuss saved some of his most biting cartoons for issues of racism and anti-Semitism. In April 1942, he showed a “Discriminating Employer” —castigating “Jewish Labor” and “Negro Labor”: “I’ll run Democracy’s War.56 You stay in your Jim Crow Tanks!” Note the evil expression on the employer’s face, and note that Dr. Seuss’s “Negro” differs from his “Jew” only in skin tone. On June 11, 1942 Uncle Sam uses a Flit gun to disinfect American brains. Says John Q. Public as a “racial prejudice bug” blows out of his ear, “Gracious, was that in my head?” As many other Americans await their turn to be spritzed, the cat in the lower right corner smiles approvingly.57 On June 16, an estimated 18,000 blacks gathered at Madison Square Garden to hear A. Philip Randolph kick off a campaign against discrimination in the military, in war industries, in government agencies, and in labor unions. On June 26, a Seuss cartoon, “The Old Run-Around,” shows “Negro Job-Hunters” entering a maze which leads only to dead ends, not to “U. S. War Industries.”58 (How any job-hunters were to get to “U. S. War Industries” is a puzzle.)

In a cartoon later that month an angry Uncle Sam taps an organist labeled “War Industry” on the shoulder: “Listen, Maestro...if you want to get real harmony, use the black keys as well as the white!” Cobwebs on the black keys underline the fact that they haven’t been used.59 In July’s “War Work to Be Done,” a white employer posts a sign on a woodpile: “No Colored Labor Needed.”60 Two blacks comment: “There seems to be a white man in the woodpile!” (The original expression is “There seems to be a nigger in the woodpile.” The term “nigger” was clearly pejorative, but the origins of the expression are obscure; it may have meant simply something unexpected.) In August a black bird of “Race Hatred” perches on the shoulder of segregationist Democratic Governor Eugene Talmadge of Georgia.61 Note that the bird wears a black hood (why not the white hood of the Ku Klux Klan?) and that Talmadge’s whip dwarfs the fenced-in state of Georgia. It is not easy to tell which of the tiny figures are black and which white, but the figures themselves are all similar, as are the houses in front of which they stand.

As we have seen, Dr. Seuss linked racism and anti-Semitism and opposed both. Anti-Semitism was one focus of his assault on Charles Lindbergh. A PM cover of September 22, 1941, stated the case in reaction to Lindbergh’s speech of September 11 at Des Moines. Dr. Seuss placed a chagrined Uncle Sam in stocks, and a sign hanging from his beak reads, “I am part Jewish.”62 The “sheriffs” who have placed him there are Lindbergh and Senator Gerald P. Nye (D-Wisconsin), one-time New Deal ally of President Roosevelt. A later cartoon involving Nye (April 26, 1942; not included here) depicted him as the hind part of a horse. According to Seuss biographers Judith and Neal Morgan, Ralph Ingersoll feared a lawsuit. But what arrived in the mail from Senator Nye was something else: “[The] issue of Sunday, April 26...carried a cartoon, the original of which I should very much like to possess. May I request its mailing to me?”

In a grim cartoon of July 20, 1942, ten bodies hang by their necks from trees, each one bearing the stark label “Jew”; Hitler stands with Pierre Laval, an additional noose at the ready.101 On October 21, 1941 (a cartoon not included here), Dr. Seuss drew “Japan” puzzling over Mein Kampf and musing, “Now what in blazes am I going to use for Jews?” A photo of Hitler hangs on the wall, signed, “Your Old Pal, Adolf.” Shortly before Christmas 1942 Dr. Seuss depicted “Race Hatred” as Adolf Hitler’s “annual gift to civilization”; a “U. S. anti-Semite” stands poised to help Hitler wrap the present.63 A wreath on the wall is filled with swastikas.

December 28, 1942, was the eighty-sixth anniversary of the birth of Woodrow Wilson, the American president who a generation earlier had attempted unsuccessfully to take the United States into the League of Nations that was, in large measure, his creation. Henry A. Wallace, President Roosevelt’s vice-president, used the occasion to deliver a speech that focused on postwar issues; the speech was carried on NBC radio. Here is one excerpt: “The United Nations [i. e., the war-time allies, not the postwar organization, which didn’t exist yet] must back up military disarmament with psychological disarmament—supervision, or at least inspection, of the school systems of Germany and Japan, to undo so far as possible the diabolical work of Hitler and the Japanese war lords in poisoning the minds of the young.”64 Dr. Seuss weighed in two days later. On December 30, in “‘Psychological Disarmament’ of Axis Youth,” Uncle Sam uses power-driven bellows to blow germs out of the brain of a Nazi boy. Uncle Sam holds a child “Japan” by the scruff of his neck; he’s next. This cartoon is a reworking of the cartoon of June 1942 in which it is American heads that need to be debugged. Thinking on race needed to change, whether here in the United States or in Nazi Germany. Dr. Seuss was not simply echoing the Roosevelt Administration, for he was also echoing his own earlier cartoon; still, the conjunction indicates how closely Dr. Seuss was attuned to the politics of the day. (This is one of the two cartoons included in this collection that do not have Dr. Seuss’s signature; the other is the cartoon on p. 217. Many of his cartoons have both signature and printed credit.)

Dr. Seuss’s campaign for civil rights and against racism and anti-Semitism had one major blind spot: Americans of Japanese descent. At the time of Pearl Harbor, nearly 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent lived on the West Coast. Two-thirds were U. S. citizens by virtue of having been born in the United States. Many of the others were prevented by law from becoming citizens. Soon after Pearl Harbor, the American government ordered the forced relocation and internment of all Americans of Japanese descent living on the West Coast. On February 13, 1942, just days before the Roosevelt administration’s decision to incarcerate all Japanese Americans living on the West coast, Dr. Seuss drew “Waiting for the Signal From Home...”65 It shows the West Coast—Washington, Oregon, and California—and a horde of smiling, bespectacled, virtually identical Asians lining up to pick up blocks of TNT from a warehouse labeled “Honorable 5th Column.” A smiling fellow on the roof looks through a telescope out to sea for that “signal from home.” It is a scurrilous cartoon. For one thing, no Japanese American on the West Coast was ever convicted of an act of sabotage. General John DeWitt, the individual most responsible for the incarceration, could not have asked for more effective propaganda. To its eternal discredit, PM never attacked head-on the incarceration of the Japanese Americans. This cartoon bears a distinct resemblance to the cartoon (December 10, 1941) that shows Japanese as alley cats: the sheer numbers, the sweep of the crowd from right rear to left front, the interchangeable faces.145

How could so antiracist and progressive a man as Dr. Seuss and so antiracist and progressive a paper as PM indulge in such knee-jerk racism? We see here a blind spot of the wartime New York left. A few people spoke out against America’s concentration camps, but only a few; more failed to see a civil rights issue of monumental consequence. No reader of PM wrote in to protest this cartoon—at least, no such letter appeared among the letters to the editor. As we have seen, there were letters against Dr. Seuss’s eagle. As we shall see, there were letters against his attack on the pacifist preacher John Haynes Holmes and against his slander of dachshunds. But there was no letter against this stark example of mainstream American racism against Asians in America.

In its domestic politics, as we have seen, the newspaper PM supported the New Deal vociferously. President Roosevelt moved right, in part because of Republican electoral gains beginning in 1936, but PM stayed the course. Even as “Dr. New Deal” became “Dr. Win the War,” PM committed itself to the New Deal goals that “Dr. Win the War” preferred to downplay. We find these commitments in Dr. Seuss’s cartoons, too, albeit in less strident forms. Most of these cartoons appeared in 1942, after the United States joined the war. In one of his political position papers, Ralph Ingersoll had written, “Labor’s interests are synonymous with ours—and with the country’s.” Dr. Seuss, too, concerned himself with labor, but his commitment seemed significantly less strong than PM’s. In November 1941, he showed Hitler welcoming news of American labor unrest.66 The point of the cartoon is in part Hitler’s control of information, in part American labor unrest. But the unrest Dr. Seuss has in mind is not primarily between labor and business but within labor: between the American Federation of Labor and the upstart Congress of Industrial Organizations, and within the C. I. O. itself. Dr. Seuss’s sympathies are not obvious. Was he merely opposed to labor unrest and for unity and maximum productivity in time of war? A cartoon of March 26, 1942 decries antilabor policies in more unequivocal fashion: “Gassing the Troops on Our Own Front Line.”67 But in October (in a cartoon not included here) Dr. Seuss derided John L. Lewis, president of the United Mineworkers and a power in the C. I. O. The cartoon is “The Lord Giveth, and the Lord Taketh Away,” and in it Lewis is the lord, and he reaches down out of a cloud with a piece of coal. A strike had brought coal production to a halt, and Dr. Seuss did not approve.

The committed pro-labor cartoons of other cartoonists of this era are strikingly different from Dr. Seuss’s cartoons. They feature men in open-throated shirts, sleeves rolled up, in overalls, wearing caps, perhaps, but not hats. Dungarees often sport union badges. Miner’s lamps are common, as are lunch pails. So are women, spectacularly so in the cartoons that focus on Rosie the Riveter. These cartoons depict a world quite different from Dr. Seuss’s.

On May 18, 1942 Dr. Seuss showed a “Reactionary Wrecking Crew of Congress” advancing with a huge wrecking ball on the “U. S. Social Structure.”68 One bearded fellow, eyes closed, drives the crane; another, eyes open, says: “We’re just going to knock out the Unnecessary Floors designed by F. D. R.!” Nine days later, amid much Congressional discussion of taxes, there appears a cartoon lambasting a “tax-exempt securities loop hole for rich.”69 A rich man (top hat, bow tie, spats) climbs up on the rump of a snooty figure labelled “House Ways and Means Committee” to climb through the loophole. The “Committee” points John Q. Citizen—tiny in comparison—to the Income Tax Window: “G’wan, small fry. You pay at the turnstile!” News reports in June showed that New York City had more unemployed people than any other city in the United States. In June, Dr. Seuss pleaded the cause of “400,000 New York unemployed.”70 In October a cartoon attacked the poll tax: “Democracy’s Turnstile: Vote Here (If you can afford it).”71 Here again the crowd is all male and all white. (The poll tax—an annual tax for the right to vote—was an issue with clear racial implications, for it was southern states that had poll taxes.72) A later cartoon (November 16, 1942) attacks a prime instrument of conservative opposition to the New Deal, the filibuster. A huge creature, part dog, part dragon, flies through the sky over the Capitol in Washington, D. C. A diminutive Senator Theodore Bilbo (D-, Mississippi), prominent filibusterer, stands on the back of the beast, using its thirty-foot-long ears as reins. Attached to him is the label “Poll tax bloc.” Bilbo’s career (and life) ended several years later as Congress investigated the charge that he had intimidated blacks from voting. More than twenty-five years elapsed after the appearance of Dr. Seuss’s editorial cartoons before poll taxes were abolished. In 1964, the Twenty-fourth Amendment outlawed poll taxes for primary and general elections for national offices; at that time five states still had poll taxes. Because of a general sense that that constitutional amendment was ineffective, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which authorized a legal test of all poll taxes; two years later, in 1966, the Supreme Court extended the ban to all elections.