We turn now to the rest of the world. Dr. Seuss depicted much of the world only in passing; he focussed on Hitler’s Axis partners—Italy and Japan—and on France, the Soviet Union, and Great Britain. So we shall deal here with those countries in that order.

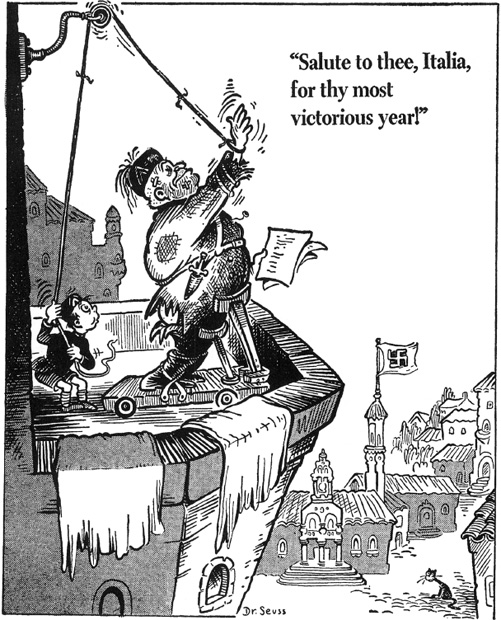

Italy and its dictator Benito Mussolini were easy targets for Dr. Seuss. In June 1941, Dr. Seuss drew Mussolini making a speech: “Salute to thee, Italia, for thy most victorious year!” Of course, the year had not been victorious, either for Italy or for Mussolini: the Italian invasions of Egypt and Greece had failed, the British had captured Ethiopia on May 16, 1941, and German influence in Italy had risen.127 Here Mussolini stands atop a wheeled platform, feet strapped down and legs propped up by wooden braces; even his right hand needs an assist from an overhead pulley to salute the assembled multitude. But assembled multitude there is not; in the empty town square below sits only a cat. Dr. Seuss’s Mussolini is a two-bit dictator from the start.

Mussolini was Hitler’s ally, yet when Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941 he got less than full Italian assistance. In a ceremony on June 26, Mussolini dispatched the first motorized division of the Italian expeditionary corps. Ultimately, some 200,000 Italian troops took part in the campaign in Russia; perhaps 80,000 did not return. On July 1, Dr. Seuss drew Mussolini claiming a role in the attack on the Soviet Union: “Yoo hoo, Adolf! Lookee! I’m attacking ‘em too!” He rides a pedal-driven tank; a toy-sized gun mounted on the handlebars has a cork stopping its barrel.128 Dr. Seuss’s Mussolini is going nowhere: he’s still south of the Alps, and his tank is anchored firmly.

As we noted earlier, Dr. Seuss started drawing editorial cartoons because he reacted so strongly against the words of the Fascist publicist Virginio Gayda. On November 14, 1941, less than a month before Pearl Harbor, Dr. Seuss drew Gayda and Mussolini ensconced like hermit crabs in snail shells at the bottom of the ocean; Mussolini’s shell has a sign reading “B. Mussolini, Private.”129 Says Mussolini to Gayda: “Write a piece called Mare Nostrum, and make it good and strong!” Mare nostrum is Latin for “our sea.” Mussolini used this Latin phrase to lend classical resonance to his goal of controlling the Mediterranean. In fact, after the British attack on the Italian navy at Taranto (November 11, 1940), the Italian navy played only a minor role in the war, largely in protecting convoys between Italy and North Africa. The Italian navy is a joke, Dr. Seuss seems to be saying, and the talk is hot air. “Good and strong” indeed!

After Pearl Harbor, Italy declared war on the United States on December 10, 1941 in tandem with Germany, Japan’s other Axis partner. The United States reciprocated on December 11. On December 22, 1941, when Dr. Seuss drew “Bundles for Benito,” the basic elements of his Mussolini were already in place: huge underslung jaw, five o-clock shadow, split upper lip, excess poundage.130 In this cartoon there are crossed bandages on Mussolini’s bared hip; in later cartoons the bandages migrate to the side of Mussolini’s head.131 In a January 1942 cartoon, Hitler and “Japan” look to a bouncing Benito as a source of rubber to patch a flat tire; the unidentified booted foot that has sent Benito bouncing may be the British forces in North Africa which in November and December had sent Germany’s Afrika Korps under General Rommel retreating westward and, in the process, isolated and captured Italian forces. By speaking of Axis shortages, Dr. Seuss may have hoped to divert attention from shortages on the home front. Dr Seuss continued his mocking assault on Mussolini’s classical pretensions in “Caesar and Cleopatra” (not included here). Mussolini is depicted as Caesar, and he has his arm about the waist of Cleopatra, a dressmaker’s dummy, headless and legless; a tag labels her “Egyptian booby prize, made in Berlin.” In a cartoon of July 21, 1942, Hitler rides the backs of Mussolini and Laval, promising them “War Spoils”—the skeleton of a fish.132 Dr. Seuss added in parentheses “(+ I do mean spoiled!).” No matter what Dr. Seuss’s attitude toward Hitler, it is clear here that he had only contempt for Mussolini and Laval. In an August image (“Rome-Town Boy Makes Good!”) Mussolini vacuums a pyramid.133 The subtitle, “194? Benito Cleans Up Egypt,” mocks Italian ambitions once more. Despite British bases on its territory, Egypt remained neutral until joining the Allies in 1945. Mussolini was fit to be janitor, nothing more.

Dr. Seuss’s cartoons of October 20, 1942, and November 11, 1942, show Mussolini with crossed bandages on temple, albeit different temples.134 These cartoons display not only the dictator in all his fecklessness but also other Italians with faces clearly different from Mussolini’s. In the former, there are four other Italians. One has glasses, all four have mustaches, and none bears the slightest resemblance to Mussolini. Dr. Seuss underlined the message of hardship on the home front in several ways: the cobweb on the pantry shelf, the lone wisp of smoke rising from the stovepipe, the similarly anemic steam above the pot of water, the hands resting on the stove top, the patch on the coat of the man on the right. On November 11, Dr. Seuss depicted Mussolini pulling wings off butterflies (Ethiopia, Croatia, Albania, Greece—all targets of Italian attack), oblivious of the “Inevitable Invasion of Italy.”135 Note that these (friendly) planes have the same barbed noses as did Hitler and “Japan” in the earlier “Quick, Henry, THE FLIT!” With the Allied invasion of North Africa, the German occupation of the rest of France, and French admiral Darlan’s surrender to the Allies in North Africa, the inevitable was several steps closer.106 On November 17, Dr. Seuss drew “Jitters a la Duce.”136 Comments one Italian general to another as they watch Mussolini in his ornate bathroom: “His hand ain’t so steady. These days all he dares shave is his reflection!” Indeed, the cartoon Mussolini is applying lather to the mirror.137 On December 2, 1942, Dr. Seuss predicted Mussolini’s fate: a dodo (“Extinct 249 yrs.”) summons him with the words, “Are your bags packed, Sir? They’re exhibiting you in the Museum.” (Mussolini’s actual demise—execution at the hands of Italian partisans—would come more than two years later, in April 1945.) This is not the first time Dr. Seuss relegated a target to museum status: in “Hall of the Extinct,” he did similarly with an ostrich labeled “Isolationism.”48

Among foreign countries Japan is second only to Germany in the number of times it appears in Dr. Seuss’s cartoons. From its first appearance in June 1941 to a final appearance on December 7, 1942, Dr. Seuss included figures representing Japan in dozens of cartoons. The first cartoon shows Japan resisting the urging of Hitler, its Axis Alliance partner, to enter the war: “Japan’s” feet stick through the hull of his ship to brace against a rock on the ocean floor.138 In pidgin English, “Japan” says to Hitler: “Please push bit harder. Hon. feet still slightly holding back.” In mid-1941 Japan and the United States were engaged in the long negotiations that ended without success in late November, and Dr. Seuss may have had those negotiations in mind here: Japan and the United States were exploring the possibility of moving away from confrontation, but Hitler’s interest was clearly in having the Japanese in the war.

This “Japan” is a comic opera figure, owing more to Gilbert and Sullivan than to reality. His uniform has showy epaulets. His tall, cockaded hat has its own gaudy topping, and Japan’s imperial battle flag flies above. He wears heavy glasses over his slanted eyes. He has long thin mustaches. The pidgin English would appear in later cartoons, too. The term “Jap” would become almost a staple. The slanted eyes would remain. Indeed, in a cartoon about the Vichy French purchase of some Japanese ships (April 22, 1942; not included here), Dr. Seuss drew the French premier Laval on the operating table directing his doctor, “Doc, give my eyes a slant. I’ve joined the Japanese Navy.” In a late June cartoon not included here, “Japan” has conflicting body tattoos—the “Nazi pact” is the Axis Alliance, and the “Russ pact” is Japan’s non- aggression treaty of 1939. Eight days earlier, on June 22, Hitler had invaded the Soviet Union, leaving Japan highly uncomfortable with its nonaggression treaty; and of course, Japan was involved in negotiations with the United States that the United States hoped would make it wish to erase the “Nazi pact” tattoo. In July, “Japan” appeared sick in bed, attended to by Dr. Hitler, who urges him to invade Russia (“a restful little excursion up Vladivostok way”).139 After Germany invaded the Soviet Union, the Japanese government did face a decision in late June and early July: move north against the Soviet Union (despite its nonaggression treaty with the Soviet Union, Japan’s leaders were fiercely anti-Communist) or move south into resource-rich Southeast Asia. Japan chose the latter, and that choice brought with it war against the United States.

Over the months, Dr. Seuss’s “Japan” gradually evolved into the caricature we’ve already encountered in the cartoons of Hitler. A cartoon of Oct. 20, 1941 (not included here) shortened the mustaches (perhaps to ape Hitler?) and turned the nose piggish. These elements became part and parcel of the final “Japan,” although there were side trips along the way. Dr. Seuss drew “Japan” as child (November 11, 1941) and as man (November 28, 1941).140 141 The child asks for kerosene, Excelsior, and a blow torch—hardly what’s needed for a cake. (Excelsior is fine wood shavings once used as a packing material; soaked in kerosene and ignited, the shavings become an arsonist’s delight.) The man demands “a brick to bean you with.” Strikingly similar in execution, these cartoons both allude to the U.S. freezing of Japanese assets (and hence the end of all trade) in the summer of 1941, against which Japan protested bitterly. Poor in natural resources, Japan got much of its war—and peace—matériel from the United States, and oil was by far the most important single item. The argument against such sales to Japan figures in these cartoons: why supply dangerous materiel to a likely enemy? The argument for such sales recognized that a desperate Japan would have to take action to secure its own supply of oil; it was a logic that many within the Roosevelt administration understood, and President Roosevelt himself had endorsed it a year earlier, in 1940. In common with much of American opinion at the time, Dr. Seuss showed little awareness of the threat that United States actions posed to Japan. The man of November 28 is far more sinister than the child of November 11. By the latter date, negotiations between the United States and Japan had broken down completely; Dr. Seuss probably did not know it, but negotiations between the United States and Japan effectively came to an end on November 26.

Dr. Seuss also depicts Japan and the Japanese as cats. On December 1, 1941, Dr. Seuss had Japan as a cat drowning because of the heavy weight of China tied to its tail.142 Japan had been at war with China since 1937; it had proved an unwinnable war. In the cartoon, Japan certainly doesn’t appear dangerous; indeed, it is drowning and cannot save itself. On December 5, 1941, two days before Pearl Harbor, Dr.143 Seuss drew Japan as a monkey to Hitler’s organ-grinder, perhaps effective propaganda but a misreading of the actual relation. Depicting the Japanese as monkeys or apes was a common practice of American and British political cartoons of the war era; the choice of cats, I think, is unique to Dr. Seuss. These last cartoons of late 1941 raise an issue for which there is no answer: Did Dr. Seuss really take Japan so lightly? or was he whistling in the dark? Was he truly confident of U. S. power vis-à-vis Japan? or did he simply not believe that Japan would attack? Recent scholarship—see, for example, Paul Kennedy’s The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (1987)—suggests strongly that Japanese victory was impossible, that given U. S. economic strength and Japan’s economic weakness, the eventual outcome of the war was never in doubt. But the view from today and the view from 1941 are not the same. Had Dr. Seuss thought the issue through? Probably not.

By Pearl Harbor Dr. Seuss’s “Japan” is complete, and we see it most clearly in his cartoon of December 9, 1941.144 This is his second cartoon after Pearl Harbor and the first to treat Japan. As in “The Latest Portrait” of Hitler, so here: “Japan” appears five times. The Hitler portrait was a gibe at the German dictator’s ego. Here we realize that for Dr. Seuss there is only one Japanese. Hitler and Mussolini stand among other Germans and other Italians, who are usually visually distinct. But there are no other Japanese. Is this why Dr. Seuss’s cartoons of Japan have more bite than his cartoons of Hitler?

This “Japan” is not a portrait of a specific Japanese leader. It is not the emperor; it is not General Tojo Hideki, the wartime prime minister; it is not Foreign Minister Togo Shigenori (despite the caption on the cartoon of June 20, 1941 that shows Hitler, Stalin, and Togo).166 All three of those faces appeared regularly in the American media, as did—particularly in the final weeks before Pearl Harbor—the faces of Japan’s negotiators in Washington, Kurusu Saburo and Nomura Kichisaburo. Yet, rather than a specific person, Dr. Seuss draws “Japan”—piggish nose, coke-bottle eyeglasses, slanted eyes, brush mustache, lips parted (usually in a smile). On its face it is not a particularly sinister depiction, so when one version, used to sell war bonds, received the caption, “Wipe that sneer off his face!” there was a disconnect of sorts between drawing and caption.16 Surely it is more smile than sneer.

But notice the activities of the “Japan” figures. They employ slingshot, hotfoot, hammer-on-head, drill-in-back, trapdoor. These are hardly life-threatening assaults and seem more in the nature of Laurel and Hardy slapstick. Of course, it is true that the censors blocked full reporting of U. S. losses at Pearl Harbor, but this cartoon seems if anything less sinister than Dr. Seuss’s depictions of Japan before Pearl Harbor. Finally, the cartoon as Dr. Seuss draws it (the original is in the San Diego collection) bears a subtitle: “Good God! I’ve been raped!” Given the relative tolerance of the time toward rape, the assault is clearly meant to seem something less than life-threatening.

Two of the most powerful of all the editorial cartoons are monumental juxtapositions of this “Japan” and Hitler. The first appeared almost immediately after Pearl Harbor (December 12, 1942), when Dr. Seuss drew Hitler and “Japan” as enormous faces on a new Mt. Rushmore.146 Note the swastika flag flying above the U. S. flag and the four figures (none of them labeled “You”) that stand and regard the statues.

The stunning Japanese gains of late 1941 and early 1942—Hong Kong surrendered on December 24, Singapore surrendered on February 15, and fighting continued in the Philippines, Borneo, and other parts of the Pacific—must be behind a cartoon of February 17: “Keep count of those fox-holes!” The losses to Japan were hardly fox-holes, nor did they come at the hands of tanks (note the swastika on the barrel of the gun); but Hitler made no startling gains in the European fighting in January-February, so the cartoon must refer to Japan.147 The day before Dr. Seuss had drawn a cartoon—not included here—showing Hitler and “Japan” as cattle rustlers who comment, “Funny...Some people never learn to keep their barn doors locked.” The barns in the background carry labels: “Singapore,” “Pearl Harbor,” “Maginot Line.” But of course the end run around the Maginot Line was already nearly two years in the past.

In March 1942, in the second of the monumental juxtapositions, Dr. Seuss depicted Hitler and “Japan” as faces on a billboard and asked, “What have YOU done to help save your country from them?” (March 5, 1942).148 Note that the John Q. Public figure now has “YOU” inscribed on his back. “Japan” is missing his glasses in a cartoon of April 20, 1942, in which Dr. Seuss celebrated the quixotic bombing of Japan by General James Doolittle’s “Doolittle’s Raiders.” The glasses are missing for a very specific reason: to enable an American pilot to spit in “Japan’s” eye.149 Still, one line from “Japan’s” forehead curls around his right eye, forming almost a vestigial eyeglass.

In tracing Dr. Seuss’s “Japan” from December 9 until April 1942 we have skipped over an important cartoon of December 10, 1941.145 It shows Uncle Sam under siege by literally hundreds of cats in “JAP ALLEY”: “Maybe only alley cats, but Jeepers! a hell of a lot of ‘em!” All of the cats have slanted eyes, and one of the cats takes a prodigious leap from the middle of the crowd up and over the corner of the fence to descend on Uncle Sam from behind his back. We might conclude that this cat represents the attack at Pearl Harbor, but Uncle Sam already has one cat in his grasp, so the flying cat is not the first.

It remains for us to examine several later “Japans.” Three months later Japan had made even more gains: the Dutch surrendered in the Dutch East Indies on March 5, in the Philippines Bataan surrendered on April 9, the Japanese landed in Northern New Guinea in April. But the Battle of the Coral Sea (May 4–8) represented Japan’s first strategic defeat, and it may be behind the optimism of a cartoon on May 12. Dr. Seuss acknowledged Japan’s successful springboarding around Asia and the Pacific—China, Java, Sumatra, Burma, the Philippines, New Guinea—but still forecasted Japan’s ultimate defeat.150 The final springboard reads, “To Complete and Utter Destruction,” and the “Japan” waiting to jump on it says, “ME...? Oh, I’m the Climax of the Act!” On Aug. 13, 1942, Hitler, “Japan,” and “YOU” appeared “Playing Musical Chairs...For Keeps, and With Experts.”151 Here it is the “YOU” figure (note the suspender buttons) that is small compared with the figures of “Japan,” Hitler, and Mars, the god of war playing a song titled “War.” Three contestants, two seats: “YOU” know he’s in deep trouble.

The Japanese captured eight of the fliers of Doolittle’s Raiders and in October 1942, claiming that they had strafed a schoolyard, announced dire threats: “If enemy fliers, in disregard of humanitarian principles, persist in their cruel, inhuman ‘what the hell’ attitude in the future they will face death or some other severe punishment.” Although the news was not made known until April 1943, on October 15 the Japanese did execute three of the American fliers. In reaction—to the threat, not to the fact of the deaths—comes the nadir in Dr. Seuss’s renderings of “Japan.”152 The face we’ve come to know. But this time his teeth are jagged, a skull hangs from his top hat, his arms end in lobster claws, and his legs, in bear paws. His left claw squeezes a human figure, and three other figures are on the ground, presumably dead.

In November 1942, Dr. Seuss reverted almost to the Gilbert and Sullivan “Japan” with which he began, and in a cartoon from November 18, the gaudy epaulets and hat are back on the figure reporting naval disaster to the emperor.153 The throne on which the Son of Heaven sits sports matching guardian beasts (with eyeglasses, no less), a paper lantern dangling overhead, and a rising sun emblem on the headrest. This is the sole Japan cartoon where there are distinct differences among Japanese. The emperor has no mustache—all the more startling because of course Emperor Hirohito did wear a mustache. The 40,000 dead are apparently the Japanese dead in the fighting in the Solomon Islands in the Southwest Pacific, for that is the only naval battle at the time.154 On December 7, in his final cartoon featuring Japan, Dr. Seuss regresses still further. December 7 is the anniversary of Pearl Harbor (not the anniversary of the alliance between Japan and Germany), and Dr. Seuss portrays husband Hitler, ugly wife “Japan” (no glasses, no mustache, piggish nose, outsized breasts), and in a cradle beside them, “Hashimura Frankenstein.” The baby is a misshapen buck-toothed monster with mustache, flaps for ears, and legs that end in claws; his adult right hand wields an axe.

Perhaps it is no surprise that American cartoonists during the Pacific War painted Japan in overtly racist ways. However, it is a surprise that a person who denounces anti-black racism and anti-Semitism so eloquently can be oblivious of his own racist treatment of Japanese and Japanese Americans. And to find such cartoons—largely unreproached—in the pages of the leading left newspaper of New York City and to realize that the cartoonist is the same Dr. Seuss we celebrate today for his imagination and tolerance and breadth of vision: this is a sobering experience.

France posed cartooning challenges somewhat different from those presented by Hitler’s Axis partners. In 1941, the northern half France was occupied by the Germans; the southern half was in theory independent under a government located at Vichy. It had not one leader but two: Marshall Henri Philippe Pétain, the aged hero of World War I who became the first chief of state of the Vichy regime, and Pierre Laval, who in 1942 assumed dictatorial power in Vichy. Dr. Seuss also drew cartoons (not included here) featuring Admiral Jean-Louis-Xavier-François Darlan, minister of the navy in the Vichy regime and—briefly in late 1942—collaborator with the Allies, and Jacques Doriot, leading collaborator. An early cartoon shows Hitler picking the pocket of a totally befuddled Pétain.155 The French leader wears his marshall’s cap from World War I and dress uniform of striped trousers, jacket, and cape. Pétain looks skyward toward Hitler’s Sieg Heil salute, but the saluting arm is a prop, and Hitler’s real right hand reaches out to relieve Pétain of his watch. In June 1941, Dr. Seuss drew France as a battered prizefighter (“François”) whom Hitler and Mussolini summon to new battle against Britain.156

Pierre Laval served as vice-premier and foreign minister in the Vichy government of Marshall Pétain from its inception in July 1940 until December, when Pétain, doubting his loyalty, dismissed him. Based in Occupied France, Laval advocated collaboration with the Nazis and Hitler. In April 1942, apparently under Nazi pressure, Pétain reinstated him in the Vichy government, and in November Laval assumed dictatorial powers. Laval approved the shipping of French workers to Germany, the creation of French fascist militia, and the establishment of a highly repressive regime.103 (In 1944, he followed the retreating German army into Germany, and in 1945, back in France, he was executed by firing squad.) In April 1942, Dr. Seuss commemorated his return to Vichy in “Marianne...look what the cat brought back!”157 The cat, complete with three swastikas cut into his fur, is Hitler, and the cat’s foul-smelling burden is Laval, hand raised in salute. Leaning on his cane, Marshall Pétain speaks to Marianne, the symbol of France’s Third Republic (1870–1940), which ended with the fall of France.

Laval becomes the subject of some of Dr. Seuss’s most vitriolic depictions. A cartoon in June 1942 shows Hitler playing Laval like a violin.158 (The original drawing in the Dr. Seuss Collection of the University of California at San Diego has an alternate caption: “Amazing what tone I can get out of such a cheap instrument!”) Note here the swastikas on Hitler’s cufflinks and on the very notes!159 In October, Laval sells a caged France “Down the River.” (That expression comes from the practice of American slave owners in the upper South of selling difficult slaves down the Mississippi to a worse fate in Louisiana.)160 Also in October Hitler and Laval combine to put “France” through the wringer of war. And Laval figures in two of the most brutal of all Dr. Seuss’s cartoons of Hitler: singing with Hitler as Jewish bodies hang from trees in the background, and slouching out of a cave to round up 400,000 Frenchmen to labor in Germany.101 103 Indeed, if one were to judge only from the cartoons of Dr. Seuss, one might conclude that Pierre Laval—not Adolf Hitler—is the most evil figure of World War II in Europe. Compared with his craven Laval, Dr. Seuss’s Mussolini is a buffoon pure and simple.

The Soviet Union posed complex issues for any cartoonist, let alone one drawing cartoons for PM. American policy had been resolutely anti-Soviet, but on the Left there was great sympathy for the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union had signed a non-aggression treaty with Hitler, and then, in 1939, assisted Hitler in the destruction of Poland. Until the very end of the war, the Soviet Union had a non-aggression treaty with America’s enemy Japan. When Germany attacked Russia in June 1941, the Soviet Union gained more favor with the American public, and Soviet casualties in the war far outstripped those of any European or American ally—indeed, all European and American Allied casualties combined. One’s attitude toward the Soviet Union often had immediate consequences for one’s attitude toward the American Communists, and vice versa. Though Communists were a major element in Denning’s Popular Front of the 1930s and early 1940s, Dr. Seuss seems to have been skeptical of both.

Dr. Seuss portrayed the Soviet Union in four images. One is as a dinosaur to Hitler’s caveman (August 16, 1941): clad in animal skin, Hitler whacks away at the dinosaur’s tail, oblivious to the danger of riling the monster.161 Here Dr. Seuss had the big picture right: that the Soviet Union, albeit at enormous cost, would prove to be Hitler’s downfall. But in August 1941, only eight weeks into the German assault, that was far from certain. In a second image, the Soviet Union is winter personified. In his cartoon of February 6, 1942, “Russian Winter,” an icebound giant sitting atop Hitler holds a stopwatch registering (improbably) “February.”162 In the background “YOU + ME” wonder, “Yeah...but who takes over when the big guy’s time is up?” Indeed, it would be the second Russian winter, 1942–43, that saw the crumbling of the German forces. (Think back to the cartoon on page 104, showing a giant Russian snowball taking a tiny Hitler down the mountainside; that cartoon appeared ten months after this cartoon, during that second Russian winter.) Dr. Seuss also depicted Russia as a bear. In a cartoon of June 25, 1941, the Soviet bear resists the intentions of “A. Hitler, Taxidermist.”163 Among the trophy heads already adorning his wall is Italy. Why Italy? It is hard to say. Hitler did intervene in Italy to prop up Mussolini, but those events came in 1943, not 1941. Note that unlike the other stuffed heads, all with antlers, Italy is a pelt, unmounted, stretched on tacks; its genus—skunk? polecat? squirrel?—is hard to judge, but it is certainly several steps down the scale from the animals on the rest of the wall. In “The Unexpected Target” (July 4, 1941), Dr. Seuss suggests opportunity for Uncle Sam, not in alliance with the bear—that would come later, but incidental to the German attack.164 A cartoon one week later comments on Soviet casualties, but in a backhanded fashion.165 Hitler is cheerleader (“Sis! Boom! Bah! Rah!”) to his Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels, who uses an adding machine to tally Soviet deaths. The figures start at 9,128,275 and climb higher, sometimes by fractions and decimals, soon reaching 87,429,387,256. The figures are clearly spurious, a product of the Nazi propaganda mill. But Soviet casualties were real casualties, not mere statistics, and even without Nazi inflation they soon reached staggering proportions. Indeed, postwar estimates of Soviet civilian and military deaths in World War II often exceed 20,000,000, nearly one hundred times higher than U. S. civilian and military deaths. Of that sobering fact there is little inkling here.

But for Dr. Seuss the Soviet Union is preeminently its dictator Joseph Stalin, whom we have encountered already. Just before the German attack on the Soviet Union, Dr. Seuss had Stalin hopelessly entangled in pacts with Hitler and “Japan.” In this cartoon, Stalin wears a Cossack-style costume with billowy pants and blousy top.166 Says Hitler (with his mouth closed!): “In other words, gentlemen, Togo won’t hit Joe and Joe won’t hit Togo...unless they take a poke at each other when I start socking Joe.” Hands, toes, teeth: all come in handy in holding five sheets of paper labeled “Pact.” In fact, there were only three pacts, and three of the sheets in the cartoon perform the same task of linking Stalin and “Japan,” but visual impact trumps exactitude. Dr. Seuss’s Stalin appears happy in this Axis company.

Two days after this cartoon appeared Germany attacked the Soviet Union, just as Dr. Seuss predicted, and Dr. Seuss overcame his initial anti-Communist concerns to draw a benevolent Stalin. On August 11, in one of his limerick cartoons, Dr. Seuss showed Stalin knitting a huge sock: “In Russia a chap, so we’re told,/Knits an object strange to behold./Asked what is his gag,/He says “This is the bag/That the great Adolf will hold!’” Russia will defeat all invaders.167 Here Stalin wears the military shirt he often wore, not the Cossack outfit we noted earlier. Again, on December 24, 1941, Dr. Seuss depicted Stalin as a chef/headwaiter, hammer and sickle in hand, serving “Roast Adolf”—a pig.168 Two months later, Dr. Seuss’s sympathy is clearly with Stalin, as a dowager on Uncle Sam’s arm expresses disdain for Stalin the redcap, who carries an impossible load.169 In addition to a huge trunk labeled “Our War Load,” Stalin carries eighteen pieces of luggage—and two umbrellas! The dowager is “Our Cliveden set,” a reference to a pejorative coinage of the Communist journalist Claud Cockburn in 1937 to refer to pro-appeasement British nobility supposed to meet at Cliveden, the country home of Viscount Astor and his American-born wife Nancy. Lord Astor owned the Observer; his brother controlled the Times. Note the striking difference in tone between these three cartoons and the earlier ones. Like Dr. Seuss’s Hitler, his mature Stalin has no visible mouth. His hook nose bends down over an immense mustache. His eyebrows stand out below a low hairline; his chin is full—indeed, double. The only other Russian Dr. Seuss mentioned by name is Vyacheslav Molotov, and he does not appear in a cartoon; instead, he is a recipient of membership in the Society of Red Tape Cutters.

On August 6, 1942, Hitler walks a “Velvet carpet” of human bodies to reach the oil wells of the Caucasus, Soviet territory.170 The bodies are all male and wear boots and swastika armbands, so the reference seems to be to German soldiers killed in the campaign. The German offensive in the Caucasus began July 25 and bogged down in the mountains during the winter of 1942–43. By April 1943, the Red Army had almost restored the military status quo ante. Hitler’s forces never did reach their target—the oil fields of Baku. Note that Dr. Seuss focused exclusively on German casualties, perhaps to emphasize Hitler’s indifference to the cost. But where are the Soviet casualties? As with “Sis! Boom! Bah! Rah!” so here: Soviet casualties are not foremost in Dr. Seuss’s thinking.

In August Dr. Seuss predicted trouble for Germany in its campaign in the Soviet Union.171 Stalin does not appear in this cartoon, nor does Hitler, but two German underlings, one a military officer and the other a civilian, read a letter from Hitler asking that they send him his winter underwear: “Tck, Tck! Now he writes it looks like he’ll need dot Historical Underwear back!” The underwear in question, now on display in Room XXIV of “Adolf’s Museum,” was “worn by Der Fuehrer before Moscow in 1941.” It is displayed with right arm raised in Sieg Heil stance.

At first Dr. Seuss’s Russia was the enemy of his enemy. Over time it metamorphosed into a more positive image, but even late in 1942 there was ambivalence in Dr. Seuss’s depictions of the Soviet Union.

Dr. Seuss rarely drew Britain. In the Munich Pact of September 30, 1938, Great Britain and France acceded to Hitler’s demands on Czechoslovakia as the price for avoiding general war. But thereafter Great Britain took a strong stand against Hitler and bore the brunt of his air attacks in 1940-41. Given the role of Great Britain in the war and particularly in the American run-up to the war, this relative absence is itself noteworthy. Nor did Dr. Seuss ever draw British leader Winston Churchill, the focus of so many wartime cartoons that emphasized his cigar, his paunch, and his “V for Victory” sign. Since Dr. Seuss drew cartoons only between January 1941 and January 1943, there was no call for him to castigate Neville Chamberlain for Munich (although we have seen his cartoon lampooning the “Cliveden Set”) or mourn the British-French evacuation of Dunkirk or celebrate the Battle of Britain and the Royal Air Force. Yet Churchill and Britain are front and center in the events of 1941 and 1942. Why so little Britain in the cartoons? It is hard to say.

In the early cartoons of 1941, Britain is the largely-unseen recipient (more often than not, nonrecipient) of U. S. aid. President Roosevelt had promised “All-out aid to Britain,” and Dr. Seuss quoted him in a PM cover of May 4, 1941.172 Two weeks later Herbert Hoover stands atop a vast pile of war materiel—planes, tanks, artillery, shells, crates—and hollers: “It’s all yours, dear lads! (If you can dope out a way to get it.173)” England is an island in flames in the far distance, and on the ocean between Hoover and England four freighters are sinking. In the foreground, a lazy stevedore blows smoke rings. Herbert Hoover, the former president, was hostile to President Roosevelt and opposed intervention. But he favored relief aid (food) to all of Europe and aid to Britain so long as that aid did not involve convoy duty for American ships. A cover of a September PM depicts U. S. aid under the Lend-Lease Act.174 Lend-Lease, which President Roosevelt signed into law on March 11, 1941, was one of the “steps short of war” by which the Roosevelt administration sought to keep the British afloat. In the cartoon, a sinuous highway on stilts gets the goods “Two Thirds of the way to England.” (How do the trucks turn around?)

On October 10 the “U. S. S. Neutrality Act” steams in a tight circle.175 The Neutrality Act of 1935 banned shipments of war materiel to belligerents. Revisions in 1936 prohibited loans to belligerents and in 1937 covered civil war situations (read: Spain). In 1939 the Roosevelt administration succeeded in convincing Congress to amend the law to allow “cash and carry” trade, which favored naval superpower Britain over Germany. Lend-Lease marked a further revision, so that by the time of Pearl Harbor the United States had moved far from true neutrality. But to Dr. Seuss, aid short of war was not enough.

Britain is a lion on a PM cover of November 1941.176 Here a very boyish “Japan” with a slingshot emerges between two towering giants, each with a cigar and a confident smile: Uncle Sam on the left, the British lion on the right. Note that the boy’s eyes do not slant—the only instance in all Dr. Seuss’s cartoon depictions of Japan. This cartoon must have caused the perfectionist Dr. Seuss true anguish, for the typesetter misread Dr. Seuss’s handwritten caption, “Looks Like the Mighty Hunter Has Us Cornered,” rendering the final word, nonsensically, “convinced.”

After Pearl Harbor “Gnawing at Our Lifeline” (March 11) shows Russia, the United States, and Britain as rock climbers roped together, Russia leading the United States and Britain up a cliff, but Britain is almost out of the picture.177 A mountain goat labeled “Propaganda attempts to cut us apart” nibbles at the rope between Russia and the United States.

To support Britain was to support in some degree the British empire. On February 23, 1942, amid the stunning early Japanese victories in the Pacific, Dr. Seuss drew “Hurry Up With That Ark!” This cartoon shows the U. S. in the role of Noah, with Africa (a giraffe), the Near East (a camel), Australia (a kangaroo), India (an elephant up a tree, shades of Horton), and the East Indies (already submerged in the flood).178 That many of these areas were under British colonial control does not figure in the cartoon. (For most of the parts of the world in this cartoon, notably Africa, the Near East, and Australia, this cartoon is about the extent of Dr. Seuss’s treatment.) That Dr. Seuss was torn on how to depict Britain is clear from cartoons two days apart in the spring of 1942. The first, “A Chance to Fight For His OWN Freedom” (March 31) shows Caucasians arming an angry elephant (“India”) to fight a Japanese tank; Sir Richard Stafford Cripps, the left-wing British politician Winston Churchill had sent to India with a plan for self-government that did not reach fruition, saws away at the elephant’s leg irons.179 Two days later (April 2) Dr. Seuss set the Cripps mission in a very different light.180 “Awkward Place to Be Arguing About Contracts” has the Indian elephant sitting on the back of a bent-over figure labeled “Britain,” and Britain is teetering on a tightrope. He followed these two cartoons with a third (April 17) showing a snake charmer (is it Cripps?) charming a small snake (“India’s Home Problem”) while a huge boa constrictor (“Japan”) approaches from behind, drooling at the prospect of devouring the snake charmer.181 Says snake to charmer: “Don’t look now, pal, but you’ll be needing a much larger Flute!” In a fourth (May 4), Dr. Seuss depicted the development in India that he saw as opening “The Gateway to India” for Japanese troops.182 India’s politicians had to choose between their colonial overlord, Great Britain, and Japan. Days before, anticipating a Japanese invasion, India’s Congress Party had adopted a policy toward Japan of “non-violent non-cooperation.” In fact, Japanese troops got beyond Burma only barely and briefly, and that happened in 1944.

This about-face leads us to ask a more general question: What were the connections between White House and PM during Dr. Seuss’s tenure on the newspaper? As Paul Milkman reports, President Roosevelt played an important role in finding Ralph Ingersoll the financial backing for PM; but did the contact continue thereafter? Did PM take editorial or cartoon cues from the White House? Whatever the situation, Dr. Seuss’s cartoons about Britain are remarkably few in number and ambivalent in content.