J. BROOKS JESSUP

I still remember this great ten-mile-foreign-place [Shanghai] as it was a decade ago, with its unending flood of horses and cars and its rampant competition for ostentatious display. There was no evil it did not possess, no curiosity it did not have. Deceitful and dishonest, demolishing principle and damaging ethics, it was truly a den of worldly evils. It was a most imposing site in the landscape of humanity, a so-called living hell before one’s very eyes. At that time, where was there such a sanctified ritual space [daochang 道場] for buddhacization? With hardly anyone who could recognize, understand, or believe in even the character for “Buddha,” how could the Buddha’s radiance be expected to bestow its protection?

Suddenly, from amid this jungle of ten thousand evils, numerous householders [jushi 居士] appeared, riding their vows as they came. In this place where the filthiest elements of society gather, they have broadly promoted buddhacization, and everywhere invigorated the lotus school.

In the early twentieth century, an impressive cross-section of urban elites in Shanghai turned to Buddhism. They were drawn from the ranks of the most prominent and wealthy figures in China’s premier modern metropolis: bankers, doctors, lawyers, judges, government officials, intellectuals, educators, and, above all, capitalists. Over the course of the Republican era (1912–1949), this burgeoning community of Buddhist elites established an array of new organizations for the collective practice and promotion of the faith in Shanghai, extended their influence throughout the country and abroad through the creation of a modern Buddhist publishing industry, and played a central role in the national movement to protect Buddhist temples from state secularization programs and win recognition for Buddhism as the very model of legitimate Chinese religion in the twentieth century.2 These urban elites identified themselves as “householders” (jushi 居士). Although the term “householder” had a long history of usage in the Chinese lexicon as a general appellation for a lay Buddhist,3 it took on new meanings when used by modern elites as a marker of identity in the specific context of early twentieth-century Shanghai.

Shanghai during the Republican era was China’s largest and most dazzlingly modern metropolis. Ever since the mid-nineteenth century, when it acquired its status as a premier treaty port with sizable British and French foreign settlements, the city had been transformed by Western influence and international commerce. To the many Chinese who either fled to the safety of the city from disturbances in nearby provinces or were attracted by its business opportunities, treaty-port Shanghai confronted them as a strange, almost foreign, place. A new urban elite had emerged as Chinese entrepreneurs acquired vast fortunes through trade and industry and often adopted not only the business techniques but also the cultural styles of their Western counterparts. The city’s transformation was reflected perhaps most saliently in the urban landscape and infrastructure of the foreign settlements, which boasted neoclassical Western architecture, broad French-style tree-lined avenues, electricity, running water, automobiles, trams, and other such amenities of modern life. This became the setting for the proliferation of such new urban spaces as coffee shops, dance halls, department stores, amusement parks, and movie theaters, in which Chinese residents could engage in new types of sociability and cultural activity. Early twentieth-century Shanghai’s urban culture became known above all for its opportunities for novel cosmopolitan forms of leisure, entertainment, and conspicuous consumption.4 However, such urban cultural trends were by no means universally celebrated. Indeed, there was a pervasive ambivalence expressed toward Shanghai’s cosmopolitan commercial culture, particularly among the residents of the city itself. Hanchao Lu has pointed to two general views of the city as “a symbol of economic opportunities to be seized, or … a trap of moral degeneration … to be shunned and condemned.”5 As the “dystopic” quote at the beginning of this chapter suggests, it was this deep, pervasive ambivalence toward the moral effects of Shanghai’s cosmopolitan commercial culture that fired urban elite engagement with Buddhism as “householders” in a modern metropolis.6

This chapter explores how urban elites gave meaning to their identity as householders by constructing new urban religious spaces in Shanghai’s physical and cultural landscape. I focus here on one particular space, the World Buddhist Householder Grove (WBHG, shijie Fojiao jushilin 世界佛教居士林). Along with Enlightenment Garden and the Merit Grove vegetarian restaurant,7 the WBHG was one of three newly constructed sites in the mid-1920s that became the primary spaces within which the city’s householder community would carry out its social practices throughout the remainder of the Republican era and beyond.8 On the one hand, these practices unmistakably associated each of the three sites with particular aspects of Shanghai’s self-consciously “modern” urban culture—voluntary associations for collective representation and activism, public parks for leisure and assembly, and fashionable restaurants for entertainment and social events, respectively. Therefore, these newly constructed religious spaces were not, in either fact or presentation, merely anachronistic remnants of the city’s past holding on as isolated pockets of tradition in the modern metropolis. On the other, however, householder spaces were also unmistakably differentiated from other modern voluntary associations, public parks, and restaurants by a distinctive moral orientation derived from the shared Buddhist soteriology to which the householders committed themselves as a community. The morally infused social practices carried out in these spaces went beyond merely marking householder spaces as distinctive alternatives to their competitors in the urban cultural marketplace; they proclaimed an ethical, and thus political, critique of those competitors. It was therefore through the unique combination of cultural associations and distinctions established by their social practices in newly constructed spaces that urban elites gave meaning to their identity as householders in the specific context of Republican Shanghai.

There are two reasons that the spatial construction of householder identity in Shanghai deserves our attention, both of which I will return to in the conclusion. First, the WBHG, Enlightenment Garden, and the Merit Grove vegetarian restaurant were each a new type of urban religious space that, after first appearing in Shanghai, was replicated in numerous other cities across China throughout the Republican era and to the present day. Therefore, simply by virtue of being a fixture of Chinese urban culture since the 1920s, householder spaces and identity are deserving of our attention. The second reason is both broader and more historiographical. Householder Buddhist activism was closely linked to many other “traditional” cultural activities popular among urban elites in Republican China. Although often overlooked by historians searching for modern China, when taken together these activities constituted a vast and significant field of urban elite cultural production, much of which was centered in the modern metropolis of Shanghai. In the conclusion, I suggest that the spatial construction of householder identity in Shanghai exhibited a fundamental structure of cultural positioning that was shared throughout this larger field of urban cultural pursuits. Recognition of the widespread simultaneous ambivalence of urban elites toward constructions of both foreign-derived modernity and native Chinese tradition entails a fundamental revision of received understandings of urban modernity in twentieth-century China.

MAKING SPACE FOR THE HOUSEHOLDER

The first step in the construction of a householder community and a new brand of Buddhist activism in Republican Shanghai came in 1920 with the founding of the Shanghai Buddhist Householder Grove (SBHG, Shanghai Fojiao jushilin 上海佛教居士林). The SBHG was the brainchild of Wang Yuji 王與楫 (b. 1883), a modern-educated Hunanese industrial entrepreneur, newspaper reporter, and revolutionary veteran who arrived in Shanghai from Beijing in 1917 with an established reputation as an energetic Buddhist lay preacher.9 In rented quarters at the Wuxi native-place association (Xijin gongsuo 錫金公所) on Haining Road in Shanghai’s International Settlement, Wang created a new type of Buddhist organization, the householder grove, that would eventually be replicated in cities across China and spread overseas through the Chinese diaspora. Unlike previous Buddhist lay associations that focused on a particular type of religious activity or practice, the organizing principle of Wang’s householder grove was simply the identity of its members as householders.10 The householder grove therefore placed no limitations on sect or school and integrated the full range of activities and practices in which an urban householder might want to engage. During the years when the SBHG was in operation, from 1920 to 1922, this included regular preaching, study courses, scripture reading, nianfo recitation, releasing life, charity, and woodblock printing.11 However, by 1922 Wang Yuji had become increasingly distracted by other new projects for Buddhist activism, and the SBHG leadership decided to split the original organization into the WBHG and the Shanghai Buddhist Pure Karma Society.12

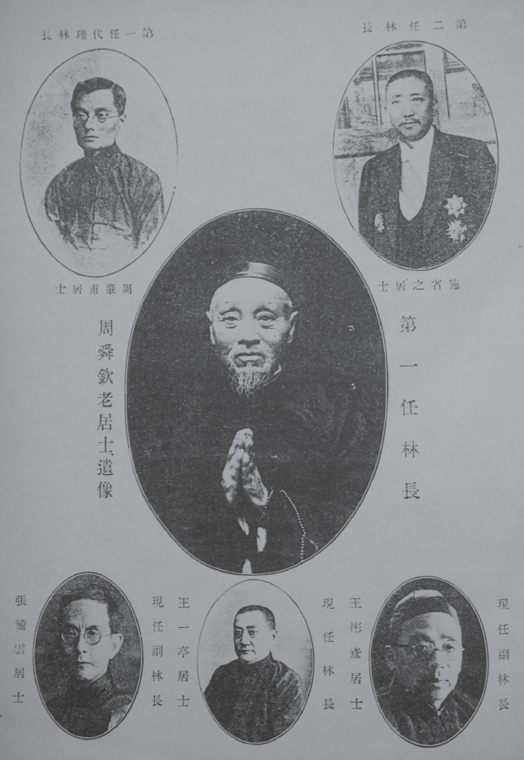

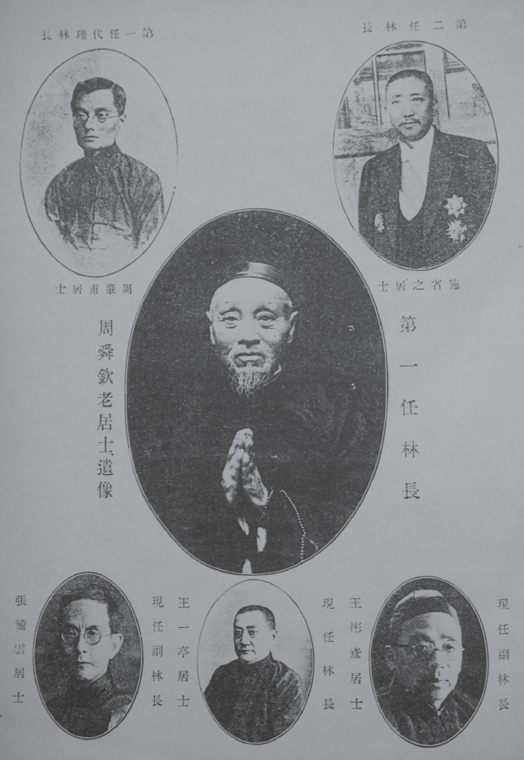

From the borrowed quarters at the Wuxi native-place association, the reorganized WBHG built upon the original framework of the SBHG. New departments, groups, and activities were added, such as a meditation hall, research society, prayer society, and an editorial office for the WBHG’s new periodical, the World Buddhist Householder Grove Journal (Shijie Fojiao jushilin linkan).13 The new designation “world” in its name signaled less an actual internationalization of the membership than a deliberate association with the growing global movement to establish Buddhism as a world or universal religion.14 In contemporary discourse, this decidedly cosmopolitan positioning distinguished the WBHG and its householders from local superstition (mixin 迷信), which had become the shame of China’s progressive elites ever since the disastrous Boxer Uprising of 1900.15 Throughout the mid-1920s, the WBHG attracted increasing numbers from the upper ranks of Shanghai’s urban populace, among them some of the most prominent notables in the city. As membership numbers grew from 170 in 1922 to 957 by the end of 1925,16 new-member records show that the majority of the incoming rank and file listed their occupations in the categories of merchant (shang 商), intellectual (xue 學), and official (zheng 政). For example, recruitment numbers for the middle of 1924 list percentages in these categories at 55, 11, and 11, respectively.17 In 1922 the membership elected as its first president the silk manufacturing magnate Zhou Shunqing 周舜卿 (1851–1923),18 who was also the founder and president of the WBHG’s host institution, the Wuxi native-place association. After Zhou passed away the following year, the second president selected (in 1924) was Shi Xingzhi 施省之 (1865–1945), a Hangzhou native who had served the Qing dynasty as consul general to the United States before returning to take up official posts in the new Republic, including director general of the Shanghai–Nanjing Railroad.19 Shi’s vice presidents were Zhou Shunqing’s younger brother and Wang Yiting 王一亭 (1867–1938), a former shipping comprador and revolutionary leader who had risen to become one of Shanghai’s most powerful capitalists and a recognized municipal leader.20 In social character, then, the WBHG was not a mass organization but rather an assembly of middle-class urbanites and wealthy elites.

FIGURE 1.1 Portraits of successive presidents of the World Buddhist Householder Grove

Shijie Fojiao jushilin chengji baogaoshu 世界佛教居士林成績報告書 [World Buddhist Householder Grove achievement report] (Shanghai: Shanghai Foxue shuju, 1933)

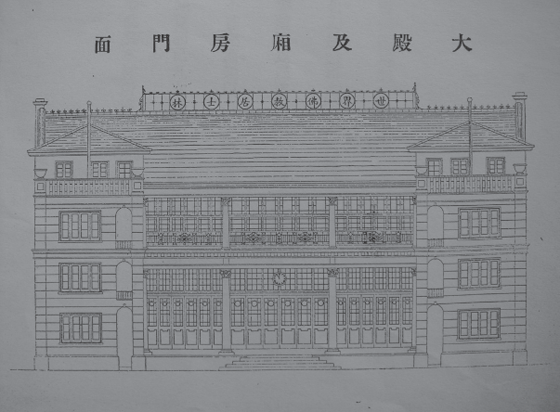

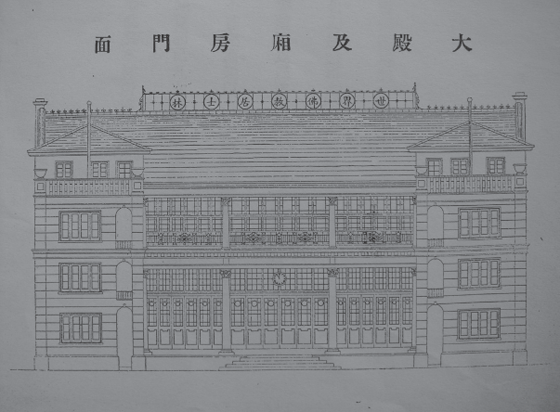

By 1925, the WBHG had outgrown its quarters at the Wuxi native-place association and was duly informed that it had outstayed its welcome. After some debate, the executive council determined to take the bold and expensive step of constructing an entirely new compound that could provide a solid basis for the organization’s long-term development. To oversee every stage of this critical project, the council formed a special construction committee led by two of its most dedicated officers, Zhu Shiseng 朱石僧 (1887–1942),21 the station manager at the Shanghai (North) Railroad Station and WBHG external communications manager, and Li Jingwei 李經緯,22 an electrical engineer employed as a central dispatcher for the Shanghai–Nanjing Railroad then also serving as head of the WBHG’s Central Affairs Department. The construction committee purchased a 2.6 mu (roughly half an acre) plot of land on Xinmin Road at its intersection with Guoqing Road. Unlike its former location within the International Settlement, this new plot was located two blocks north of the settlement border, in the Chinese-administered Zhabei district, just a short walk to the railway station. Householder Li Jingwei himself drew up the initial design for the compound to be erected at the new location and then used his connections to bring in professional architects on a volunteer basis for the final blueprints. Unlike much of Zhabei at this time, the WBHG compound was to have modern amenities such as electricity and running water. Once construction began on October 3, 1925, Li reportedly visited the site every day to personally supervise the progress through to completion in March of the following year; “no aspect of the arrangements within the compound—down to every wall, column, altar, table, plaque, and painting—escaped his master craftsmanship and superb management.”23 Despite the success of a major fund-raising campaign orchestrated by Zhu Shiseng in the spring of 1925 that brought in over 40,000 yuan (more than seven times the organization’s annual income from the previous year), the total cost of the project still left the WBHG with a bank debt of 30,000 yuan.24 Nevertheless, the heightened activism of the campaign had helped to nearly double the dues-paying membership to over 1,700 and thereby established the broad social support that would ensure the WBHG on Xinmin Road a stable and influential position in Shanghai’s urban landscape for more than a decade to come.25

The WBHG scheduled the grand-opening ceremony of its new compound for May 16, 1926, three days prior to the annual celebration of the Buddha’s birthday. In the final weeks leading up to the ceremony, Sun Chuanfang, the militarist who controlled the administration of Shanghai’s Chinese districts, publicly declared his support for the organization, and media attention was drawn to the final preparations under way on Xinmin Road.26 A palpable excitement spread among the city’s householders in anticipation of what they sensed was a momentous event in the history of their community. Perhaps the most dramatic expression of this emotional atmosphere occurred on May 5, the day construction was completed, when Householder Wang Zhengkun cut off his arm and transferred the merit for this holy act of self-inflicted violence to the future development and growth of the WBHG.27

On the day of the opening ceremony, reportedly over one thousand guests arrived at the intersection of Xinmin and Guoqing Roads in the early afternoon. As many were coming from the International Settlement, arrangements had been made in advance with the border police to allow their automobiles to cross into Zhabei without a Chinese license.28 To aid the guests in recognizing their destination, a large yellow banner was suspended across Xinmin Road displaying the words “World Buddhist Householder Grove.” Because the main outer door had yet to be installed, the otherwise unremarkable street entrance was also draped with yellow cloth and guarded by two policemen. Passing inside, the guests entered a sizable courtyard facing a five-bay, three-story, Western-style building with a large clock prominently visible at its center. Here they were attended by WBHG officers and tea servers wearing yellow badges for ready identification, who led them into a large room occupying the three central bays on the first floor of the building. This was the Great Hall (dadian 大殿), at one end of which was an altar with incense and flower offerings to large statues of Amitābha, Śākyamuni, and Maitreya, the “Tathāgatas of the Three Times” (sanshi rulai 三世如來). The walls of the Great Hall were decorated with commemorative verses composed by prominent individuals in honor of the occasion. The guests were then led to their specified seating areas: special seating was set up to the left of the altar for government officials and WBHG board members, and to the right for robed monks. The rest of the guests were seated in rows in front of the altar, with men separated to the left and women to the right.29

At precisely two o’clock, a bell was struck to signal the start of the ceremony. The guests joined their voices in singing a hymn that had been composed by the head of the WBHG’s Pure Karma Department, Householder Huang Haishan 黃海山:

A jade palace rises up to the sky, and the vows of the multitude are fulfilled;

Carrying out Buddhist affairs to repay compassionate blessings, the great earth gives allegiance;

Universally transforming the ethical norms of society, in peaceful cultivation [we] joyfully ascend together.

Praise to the bodhisattva-mahāsattvas that gather like the clouds! (Three times)

At the end of the singing, everyone joined their palms and bowed their heads. President Shi Xingzhi then welcomed the guests and delivered a speech on the history of the WBHG, the construction of its new compound, and the direction for its future development. The former New York consul general explained to his audience,

Shanghai is a place of ostentatious luxury and sensational tumult. If one wishes to practice pure karma, unfortunately there is no pure place [to do so]. Although there are ancient temples here, if we wish to use them as sites for the serious practice of householders there are many ways in which [these temples] are unsuitable. This is the reason for which the World Buddhist Householder Grove was established.

Shi’s speech was followed by a talk on karmic retribution and the path of practice by Master Yinguang, the famed Pure Land patriarch, who had agreed to serve as the WBHG’s “honored guiding teacher.”30 Yinguang concluded his talk by making full-body prostrations before the Buddha statues on the altar. Next, Zhang Taiyan, the famous revolutionary intellectual who served as a WBHG board member, and Shen Siqi, the secretary of the Jiangsu provincial government, recited verses they had composed for the occasion.31 The final speaker was WBHG vice president Wang Yiting, who, on behalf of the organization, expressed gratitude to its supporters. When Wang had finished, the ceremony concluded with another hymn by Huang Haishan:

The Householder Grove is a great sanctified ritual space [daochang], and its dignified temple buildings stand majestically;

This achievement has relied entirely on the compassionate radiance of the Buddha, [whose] vow to protect sentient beings must be repaid;

As a model for the many nations across the five continents, [we strive to] transform the great earth into purity;

[We] pledge to promote the wondrous dharma of the Tathāgata, [so that] the Way of the Buddha will forever prosper far and wide; Collectively extolling the sacred name of Amitābha, together [we will be] reborn in his kingdom of paradise.

The ceremony ended with another ringing of the bell, followed by refreshments and group photographs as the guests dispersed.32

As a choreographed public presentation of a new space that the householders had specially designed themselves, the opening ceremony positioned the WBHG, and the householder identity it represented, in Shanghai’s specific cultural context in ways that would have been clear to those in attendance. President Shi’s speech, which had in fact been jointly written with Wang Yiting and other WBHG leaders,33 pointed directly to the fundamental set of associations and distinctions that established this cultural position. At first glance, the speech reveals two things that the WBHG was to be distinguished from: the “ostentatious luxury and sensational tumult” of Shanghai’s commercial culture and the “unsuitable” environment of the city’s “ancient temples.” However, particularly when read against the built space in which this speech was delivered and heard—and which it was intended to explain—it becomes apparent that these were also precisely the two things that the WBHG was to be associated with. In other words, the WBHG was distinct from commercial culture because of its association with the “pure” space of temples, and it was distinct from temples because of its association with the “cosmopolitanism” of commercial culture. These two sets of association and distinction, mirror opposites of each other, were inscribed into the very design and function of space at the WBHG’s newly constructed compound.

THE HOUSEHOLDER AS COSMOPOLITAN ELITE

The WBHG’s distinction from Shanghai’s familiar temples was readily apparent in its building’s spatial design. Viewed from the street, there was little to suggest that the new compound was a sacred space. Barred windows, a brick facade, streetlamps, and an iron door hardly marked the location off from its surroundings. As noted, upon entering the compound, the visitor was immediately confronted by a Western-style building with straight roofs and stone columns that clearly evoked the neoclassical buildings of the International Settlement and its novel shopping centers, banks, and hotels (figure 1.2). This choice of architectural design for the WBHG paralleled a wider trend observable in the city’s proliferating urban voluntary associations during the 1920s. In her work on Shanghai’s powerful native-place associations, of which the WBHG’s original host institution was one, Bryna Goodman observes that, whereas older native-place associations were often designed in the cultural style of the group’s home province or city, the new native-place associations of the 1920s chose Western-style buildings to express their “modern spirit.”34

FIGURE 1.2 Diagram of the Great Hall and side buildings of the World Buddhist Householder Grove compound

Shijie Fojiao jushilin chengji baogaoshu 世界佛教居士林成績報告書 [World Buddhist Householder Grove achievement report] (Shanghai: Shanghai Foxue shuju, 1933)

Another prominent design feature, also readily observable upon entry, that distinguished the WBHG structure from “ancient temples” was the large clock mounted directly above the entrance to the Great Hall, from which it commanded a panoptic view of the compound. In her study of Shanghai’s middle class, Wen-hsin Yeh has pointed out that the mechanized clock, although originally only a foreign curiosity, had become, by the early twentieth century, a defining feature of Shanghai’s modern commercial culture. Far from unique to the WBHG compound, the prominent placement of similar clocks could also be found at Shanghai’s factories, office buildings, department stores, and train stations. As Yeh observes, “Modern Shanghai business organizations delineated their singular corporate space with the synchronizing power of the organizational clock. For the ordinary urbanites who made their living as white-collar employees in Republican Shanghai, mechanical clocks created the temporal frame in which their everyday life was to be lived.”35 The “organizational clock” mounted over the Great Hall at the WBHG synchronized the WBHG’s activities with the urban lifestyle of Shanghai’s cosmopolitan commercial culture. It ensured that the WBHG was running according to the same public time as that for the banker, factory manager, and office clerk. Unlike the monk living in a monastery, always within earshot of the temple bell, these urbanite working householders relied on the synchronization of clocks to participate in the WBHG’s activities. The timing of all its activities, including even the solemn rituals announced by the bell, conformed to the discipline of the clock by following a schedule divided into standard hours and minutes as precisely as that for the trains that could probably be heard on their way to and from the station located less than a mile away.

In addition to its design, its spatial function also distinguished the WBHG compound from traditional temples. A primary function of the new space was to house the WBHG organization, one so clearly unlike that represented by a temple. Its participants were voluntary members (linyuan, linyou, 林員, 林友), from whom it derived its income through dues and donations (linfei 林費), and its management (lishihui 理事會) was elected by members. Administration was handled by a Central Affairs Department (zongwubu 總務部), Funds and Property Office (kuanchanchu 款產處), Accounting Office (kuaijichu 會計處), and other offices similarly named using the modern terminology of rational administrative management.36 All these important organizational features clearly marked the WBHG as a twentieth-century urban voluntary association. Although voluntary associations had long existed in Chinese cities, the years following the establishment of the Republic, with its constitutionally guaranteed right of association, saw an explosive proliferation of such groups employing new democratic rhetoric and organizational principles. This was particularly true in Shanghai, where newly emerging social groups formed dizzying numbers of associations to represent themselves.37 These included not only new-style native-place associations but also, among others, individual associations for bankers, lawyers, and artists. Such urban groups were typically middle-class and elite phenomena, and indeed the leading householders at the WBHG were often simultaneously involved in many of them. Although these early twentieth-century voluntary associations differed in membership and content, their organizational features were largely consistent with those adopted by the WBHG, down to the very terminology used for administrative divisions and offices. Appropriating the urban voluntary association model gave Shanghai urbanites a familiar interface through which to become involved in Buddhist affairs. At monastic temples, they could never be more than external supporters or peripheral participants.38 At a Buddhist voluntary association like the WBHG, however, the householders ran their own affairs and became insiders who determined their own level of participation. In the words of President Shi, the WBHG was a much better “site for the serious practice of householders” than an “unsuitable” temple.

Another important way in which the use of space at the WBHG differed from that at Shanghai’s temples was the householders’ careful attention to ceremonial decorum. This attention to decorum was readily apparent at the opening ceremony, the scheduling of which, whether intentionally or not, set up a revealing contrast with the celebration of the Buddha’s birthday at Jing’an Temple three days later. Although bad weather dampened the festivities this particular year, Jing’an was famous among Shanghai residents for hosting the most lively annual celebrations in the city.39 The Shenbao newspaper covered these celebrations as a matter of course and year after year printed largely repetitive reports expressing unveiled scorn for the “hot and noisy” (renao 熱鬧) scene they created:

Yesterday [the Buddha’s birthday], Jing’an Temple in western Shanghai held a great Buddha festival. Average superstitious [mixin] men and women all went to burn incense and pray for blessings, and it became extremely crowded. The constable of the Jing’an police station worried that bad characters would mix in and cause trouble, so he specially sent many Chinese and Western agents into and around the temple to look after peoples’ welfare.40

This scene smacked of the temple festivals put on in villages across the countryside, which were shunned by urban elites as, in the discourse of the day, the “superstition” of the untutored masses. By contrast, what the urban householders of the WBHG valued in a religious ceremony was not “hot and noisy” but rather “solemn decorum” (zhuangyan 莊嚴). We have already seen a demonstration of this at the opening of the new compound: badged WBHG attendants ushered the guests to their arranged seating while policemen stood guard at the main entrance to keep out the uncouth. However, the WBHG took the principle of solemn decorum beyond special ceremonial occasions, writing it into the very regulations that governed the everyday use of space within their compound. The regulations for the Great Hall were set as follows:

1. The Great Hall is [a place of] solemn decorum. Those who enter must be completely respectful in order to avoid profane behavior.

2. When daily practice is taking place in the hall, visitors are welcome to join in the chanting if they wish.

3. Wandering monks and people improperly attired will not be accepted.

4. Visitors who participate in the chanting must do so according to the method of the assembly and may not use some special style or chant strange sounds.

5. If it is not a time set for daily practice, there is to be no loud chanting of sutras, mantras, or Buddha names in the hall.

6. The assemblies of men and women are to be divided into east and west and may not mix together.

7. When daily practice is taking place, there will be many attendants specially designated for the task of attending [to visitors], and they will each be wearing a yellow badge with the words “Great Hall Attendant” written on it so that they can be recognized.

8. If visitors have a matter to inquire about, they may find an attendant wearing a badge and freely consult with them.

9. Visitors who participate in chanting must follow the instructions of the attendants in such matters as seating position; visitors will please respect order and not just make a decision [on such matters] as they please.

10. The following things are prohibited in the hall:

a. Fund-raising

b. Distributing pamphlets

c. Using tobacco products

d. Talking or laughing loudly

e. Striking the ritual implements

f. Young children crying

g. Spitting

These regulations may have been inspired by similar rules at strict “public” Buddhist monasteries, but such monasteries were rare and usually located intentionally in areas remote from human traffic. In the urban environment of a densely populated city like Shanghai, the emphasis on solemn decorum distinguished the WBHG from crowded urban temples and accorded with the more cosmopolitan sensibilities of the urban elite. By participating in religious activities at the WBHG, such elites would not run the risk of associating themselves with the “superstitious” and “hot and noisy” gatherings at places like Jing’an Temple.

THE URBAN ELITE AS PIOUS DEVOTEE

Alongside the design and functional features distinguishing the WBHG from Shanghai’s temples and associating it with the city’s commercial culture, there coexisted other features that created the exact reverse set of distinctions and associations. Commercial culture in early twentieth-century Shanghai showed clear signs of becoming increasingly secularized. This trend was evident among the very voluntary associations with which the WBHG shared an organizational kinship. Bryna Goodman writes that, whereas Shanghai’s original native-place communities of the Qing had “established their associations as religious corporations … to collectively worship local or patron gods,” the new-style native-place associations of the 1920s “moved toward a more secular and national public-spiritedness” by “spurning the religious and oligarchic rituals … [and] rejecting the traditional architecture with its central altar, stage and courtyard.”42 Even with its Christian roots, Shanghai’s Chinese YMCA—itself a prime example of a successful urban voluntary association patronized by urbanites of the same social strata as the WBHG—accepted nonreligious members and had become much more a social club than a religious organization.43 Moreover, similar secularizing trends were also evident among the dazzling displays of conspicuous consumption and leisured entertainment represented most famously by the department stores and pleasure palaces along Nanjing Road, an urban space that more than any other symbolized Shanghai’s modern commercial culture to its residents, admirers, and detractors alike. As Sherman Cochrane writes in his introduction to Inventing Nanjing Road, “Unlike high culture, commercial culture is thoroughly secular; it lacks strong moral and religious overtones.”44 The ethical implications of Nanjing Road’s “ostentatious luxury and sensational tumult,” as President Shi put it, were deeply troubling to the middle-class and elite urbanites who identified themselves as householders and joined the WBHG. The householders distinguished themselves from such secularizing trends by imbuing the design and function of the space in their new compound with features associating it with the sanctity and numinous power of the Buddhist temple.

Just behind the Western-style stone columns on the ground level of the main building, a visitor to the WBHG compound would notice a stretch of wooden doorways in the style commonly seen marking the entrances to temple worship halls. Indeed, beyond these doorways was the Great Hall, traditionally a central feature of any Buddhist temple or monastery. As the WBHG’s main ritual space, the Great Hall was oriented toward a large altar with the usual tripartite arrangement of Buddha statues (figure 1.3). The altar had once been inspected by a visiting householder with the supernatural power known as the dharma eye (法眼),45 who had confirmed that “the dharma altar is sanctified beyond compare, and a great many dharma-protecting spirits are gathered around it.”46 The hall also contained a “ghost bell” (youming zhong 幽冥鐘) specially empowered to produce a numinous ringing that would save the “orphaned souls” (guhun 孤魂) of soldiers who had died during the wars of the Northern Expedition (1926–1928).47 The regular ringing of the bell marked the rhythm of the WBHG’s daily ritual schedule and its annual cycle of religious ceremonies following the lunar calendar. The ghost bell thus represented the coexistence at the WBHG of a second, sacred conception of time integrated with that kept by the mechanical clock. In addition to the Great Hall, also dispersed throughout the three-floor building were rooms that similarly paralleled what was typically found in a temple, such as a Meditation Hall (chanding shi 禪定室), Buddha-Recitation Hall (nianfo tang 念佛堂), Canon Room (zangjing shi 藏經室), and Reliquary Room (sheli shi 舍利室).

FIGURE 1.3 Scriptural lecture in the Great Hall, World Buddhist Householder Grove compound, 1933

Liang Xiaozhong 梁孝忠, Yuanying fashi honghua jiniance 圓瑛法師弘化紀年冊 [Master Yuanying’s propagation commemorative volume] (Shanghai: Yuanming jiangtang, 1949)

Among these various temple features of the compound it was the Reliquary Room that held pride of place as the jewel of the WBHG’s spatial achievement. It was a required stop on any tour of the compound, such as when the twenty-two-member Japanese Buddhist Inspection Delegation visited in December 1926.48 The Reliquary Room represented the profound numinous effect that the built space at the WBHG was intended to generate for any individual blessed with the karmic affinities to set foot inside its premises. Conceptualized and designed by Li Jingwei, the room was located on the top floor of the building, square in shape, and windowless. Its four walls were made entirely of mirrors, and numerous electric lights were suspended from the ceiling. Placed in the center of the floor, rising about halfway to the ceiling, there was a small ornately crafted treasure stupa (linglong baota 玲瓏寶塔).49 The room was designed to have a profound optical effect on anyone who entered to “ritually view” (zhanli 瞻禮) the stupa. The viewer was confronted not only by the one stupa in the middle of the room but by countless stupas interspersed with innumerable floating lights, all infinitely reflected in the mirror walls. This optical effect, which was considered so powerful that people with mental illnesses were expressly forbidden to enter, had a doctrinal basis and a soteriological purpose. The room was intended to conjure in front of the ritual viewer the “Lotus-Store World [huazang shijie 華藏世界] [in which] one penetrates all and all penetrates one.”50 As Householder Tang Dayuan explained, the viewer was surrounded by infinite manifestations not only of the stupa but also of the viewer’s own self, such that it became impossible to determine which of the manifestations were “real”: “[The viewer] realizes that stupa and self are both empty … the ten directions of the dharma world and all dharmas are empty. Because of this kind of empty viewing [kongguan 空觀], [the viewer] is able to view the true relics.”51

As Householder Tang suggested, the soteriological effect of the room did not derive from optics alone but from the numinous power of the special relics (sheli 舍利, Skt. śarīra) housed in the treasure stupa and for which the room was named.52 The “empty viewing” produced by the room’s optical effect unlocked this true power of the relics for the viewer. These particular relics—there were three of them—had been obtained by Grand Master Baipuren 白普仁, a Mongolian monk of the Buddhist esoteric tradition believed to wield incredible supernatural powers, directly after experiencing a vision of the bodhisattva Mañjuśrī at Mount Wutai.53 Simply by virtue of being in the presence of such numinous relics in this specially designed room, the ritual viewer was temporarily elevated to a higher realm (jingjie 境界) of attainment on the path to awakening and liberation. One householder described his experience in words that suggested rebirth in the Western Paradise: “All thoughts of craving, all thoughts of anger, all thoughts of ignorance [i.e., the three poisons], all killing, stealing, sex, deceit, and every sort of evil karma were simultaneously extinguished. At this instant, the hells were suddenly emptied, the triple world was transcended, and the Pure Land appeared before me.” Even after this householder departed the Reliquary Room, his elevated state of mind lasted for seven wondrous days.54

The WBHG also had numerous spatial functions that quite specifically associated it with a temple. As at any proper Buddhist temple or monastery, the WBHG operated a daily ritual schedule (table 1.1). This schedule was punctuated, as at a temple, by morning and evening practice. A small contingent of monks, including a rector (weina 維那) and a hall master (tangzhu 堂主), were housed on-site to orchestrate these daily ritual programs. The WBHG maintained an elaborate schedule dictating the specific curriculum for morning and evening practice for each day of the year. For example, the curriculum for morning practice (zaoke) on the first day of the first month of the lunar year was set as follows:

TABLE 1.1 Daily ritual schedule of the World Buddhist Householder Grove

| |

Mar.–Aug. |

Sept.–Feb. |

| Morning bell (3 times) |

4:30 A.M. |

5 A.M. |

| Morning practice (zaoke 早課) |

5:30 A.M. |

6 A.M. |

| Porridge breakfast |

6:30 A.M. |

7 A.M. |

| Vegetarian lunch |

12 noon |

12 noon |

| Evening practice bell |

4:45 P.M. |

4:15 P.M. |

| Evening practice (wanke 晚課) |

5 P.M. |

4:30 P.M. |

| Vegetarian dinner |

6:30 P.M. |

6 P.M. |

Shijie Fojiao jushilin kecheng guiyue 世界佛教居士林課程規約 [World Buddhist Householder Grove schedule and regulations] (Shanghai: Foxue shuju, undated), 2–3, reprinted in Minguo Fojiao qikan wenxian jicheng 民國佛教期刊文獻集成 [Collection of Republican-era Buddhist periodical documents], ed. Huang Xianian 黃夏年, 209 vols. (Beijing: Quanguo tushuguan wenxian suowei fuzhi zhongxin, 2006), 129:239–40.

At six o’clock the assembly enters the Great Hall;

Ringing of the stone chimes, followed by the drum;

Three prostrations, one ritual salutation, then [members] face one another;

Intone the “Baoding Hymn”;

Chant the Śūraṃgama-dhāraṇī, Mahā-karuṇika-dhāraṇī, the Ten Short dhāraṇī, and the Heart Sutra;

Sing the Mahā-prajñā-pāramitā;

Sing the Maitreya hymn three times, followed by the Maitreya gāthā;

Circumambulate the Buddha;

Chant “Praise to Maitreya Buddha who will descend”;

Strike the dang and the he [instruments], return to seats;

Put palms together, kneel, and chant three times each: “Praise to the Medicine Buddha who extinguishes calamity and extends life,” “Praise to the bodhisattva who perceives the sounds of the world,” “Praise to the bodhisattva who possesses great energy,” “Praise to the bodhisattva of the pure great ocean assembly”;

Sing “Strong Republic”;

Sing “Three Refuges”;

Chant “Praise to the bodhisattva Fragrant Cloud Canopy” three times;

Intone the Weituo hymn three times;

Make three prostrations facing the front;

Sound the great stone chime once;

Enter the patriarchs [hall] and make three prostrations;

Each person takes one stick of incense, goes outside, makes a request facing west, does one ritual salutation, takes the incense and places it in the incense burner;

Everyone returns to their own rooms;

The above [curriculum] should take about one hour and fifteen minutes.55

Such an elaborate daily ritual schedule, resembling that of a large public monastery, signaled that being a householder at the WBHG required a discipline comparable to that of an ordained monk.56 The difference was that for householders, who maintained families and careers, participation was voluntary. Householders with busy schedules often installed altars in their homes, where they could carry out morning and evening practice when unable to participate communally at the WBHG. On weekends, when more working householders could participate, the basic schedule outlined in the preceding was expanded to include an extra hour in the morning of chanting in the Buddha-Recitation Hall, an hour and a half in the afternoon of recitation and singing in the Great Hall, and two more hours of Buddha recitation in the evening. Thus on Saturdays alone there was a total of seven hours of scheduled ritual recitation and singing carried on throughout the day in the WBHG compound. Moreover, for any householder who had the ability to take at least one month of time away from family and work, the WBHG made available so-called purity dormitories (qingjing sushe 清淨宿舍) so that householders might live entirely according to the full discipline of the householder ideal.57 Just as it was the discipline of the monks that separated them and their monasteries from secular society, so too was it the daily discipline of the householders and their compound that differentiated them from the increasingly secularized voluntary associations as well as the “cathedrals of material culture” on Nanjing Road in 1920s Shanghai.

Aside from its daily ritual schedule, the WBHG also resembled a temple in its function as a daochang 道場, or sanctified ritual space, that observed the full annual cycle of Buddhist ceremonies according to the lunar calendar. These ceremonies included celebrations for the birthdays of twelve Buddhas and bodhisattvas; fourteen “offering ceremonies,” such as the Ullambana offering for hungry ghosts and deceased ancestors (yulanpen gong 盂蘭盆供); four seasonal seven-day recitation retreats (foqi 佛七); and at least one “releasing-life ceremony” (fangsheng hui 放生會) every other month.58 Beyond this set schedule, other ceremonies were often held when a special need or request arose, such as funerary rites for a recently deceased WBHG member. Members could even have “extending-life karma tablets” (yansheng yuanwei 延生緣位), for themselves, and “soul-saving lotus tablets” (jianwang lianwei 薦亡蓮位), for their ancestors, installed in the Buddha-Recitation Hall, where the tablets would receive offerings regularly throughout the ceremonial cycle.59 Ordinarily, a householder wishing to partake of such ceremonies and services would have had to visit a temple and make generous donations to the monks there. According to traditional Buddhist regulations, householders were not granted the authority to officiate at ceremonies themselves, and in fact this became a particularly contentious issue in the wider Buddhist community during the Republican era, as some householders overstepped the restriction. However, at the WBHG, monks were brought in expressly to officiate at ceremonies as well as to lecture on the scriptures, two activities that were often held in tandem. In addition to the small contingent of in-house clerics mentioned previously, the WBHG also established a “permanent lecturer” (changzhu jiangshi 常駐講師) and an “honored guiding teacher” (shangzuo daoshi 上座導師), as well as inviting “honorary lecturers” (mingyu jiangshi 名譽講師) to perform specific ceremonies. The monks who served in these positions were invariably among the most eminent masters of the era, including Yinguang and Dixian, both of whom accepted the title of honored guiding teacher. With such famously accomplished clerics officiating and the carefully maintained solemn decorum of the daochang, the ceremonies performed at the WBHG compound could be at least as ritually efficacious for householders, if not more so, than those held at any of Shanghai’s ancient temples. This space created by an urban voluntary association was thus designed to be more a proper “temple” in its function as a daochang than many of the monastically run temples that the urban environment had to offer.

A final feature of the use of space at the WBHG compound that established it as an effective urban religious center, and further distinguished it from the secularizing trends in commercial culture, was the wide range of activities or “enterprises” (shiye 事業) that it housed. By the late 1920s, these enterprises were categorized and administered under four departments (excluding the General Affairs Department). The Culture Department (wenhuabu 文化部) managed educational enterprises such as a vocational night school and free elementary school; a library with four complete editions of the Buddhist canon and hundreds of extracanonical Buddhist texts; a preaching office; and a publishing office for editing and printing periodicals and texts. The Charity Department (cishanbu 慈善部) operated a free medical clinic; a coffin-donation office; a releasing-life society; a disaster-relief association; and eventually a public Buddhist cemetery. The Religious Study Department (xuejiaobu 學教部) administered a scripture-reading office and a canon room; a research society; and a propagation society for organizing lectures. Finally, the Religious Practice Department (xiuchibu 修持部) oversaw a lay ordination and precept society, a lotus society, and a meditation hall.60 In addition to these basic enterprises, members could and did propose to the Executive Council their own ideas for groups and societies to be added to the list; the WBHG had an open organizational structure that developed according to the growth and interests of its membership. Among the most well attended of the activities held at the WBHG were the Saturday and Sunday afternoon lectures, which could be either profound scriptural expositions or topical discourses delivered in accessible vernacular language. Frequently arranged as a series that could stretch over weeks and even months for longer sutras, the lectures were delivered by many of the most famous monastic masters of the time, such as Taixu and Yuanying, and by their well-known householder counterparts, such as Ding Fubao, Fan Gunong, and Zhang Taiyan (figure 1.3). The weekend lecture colloquia were followed by textual-study seminars in which householders intensively read and discussed a set schedule of scriptural materials, again under the guidance of learned monks and accomplished householders.61

Steeped in Buddhist knowledge, the WBHG householders also took to the streets with the WBHG Preaching Brigade (xuanjiangtuan 宣講團), which was managed by the Culture Department. The Preaching Brigade was one of the vehicles through which the WBHG compound functioned as a central space for launching householders out beyond its walls and across Shanghai’s urban landscape. Such public preaching was an activity approached with both enthusiasm and prudence. Brigade members first had to be knowledgeable and presentable enough to be approved by the Executive Council. They were instructed in preaching strategy and formulas, how to respond to challenges and ridicule, what sorts of language and metaphors to employ, how to hold their posture in public, and even what to wear: “Clothing colors and designs close to secular [styles] are not worn by disciples of the Buddha. … [You] may not wear Western suits because this will detract from [your] solemn decorum and arouse people’s criticisms.”62 The brigade preached every evening for three hours from Monday through Friday within the supportive environment of the WBHG’s own Lecture Hall. Once per weekend, on either Saturday or Sunday, brigade members gathered at the compound for an outing to an “extemporaneously” determined destination (suidi xuanjiang 隨地宣講), usually a temple, factory, hospital, jail, refugee shelter, or other similar public place. For example, on one occasion, the brigade met on the day after the Qingming Festival:

On that morning, when the bell struck 9:00 A.M., Brigade Manager Zhang Xingren and members Du Jingzhai, Zhu Jinhua, Zhang Shilin, and other householders assembled at the WBHG and set out. They took the electric tram from Haining Road and got off at Xujiahui, [from where they] walked to Longhua Temple [i.e., the largest Buddhist temple in Shanghai]. Seeing crowds of people offering incense and tourists, [the brigade] energetically advanced to take advantage of the opportunity.

Householder Zhang Xingren visited the temple’s abbot, explained the mission of the WBHG, and received both encouragement and permission. They then selected an empty space in front of the second hall, raised a flag, and [prepared to] start preaching. The time was 10:30 A.M.

That day the weather was cool and comfortable, and the audience reached about three hundred people. Before the householders began preaching, they heard the people offering incense and tourists yell that they did not want to hear the sounds of Christianity [yesusheng 耶穌聲]. Upon learning that Buddhism was to be preached, they were happily surprised. They had never seen Buddhism preached extemporaneously before.

Then the two householders Zhang Xingren and Zhu Jinhua took turns preaching. Their main message was to urge the audience that if they cut off their worldly afflictions and chanted the Buddha’s name without interruption, they would be able to extinguish all their karmic obstacles and be reborn in the Western Paradise, [where] they could be liberated from the samsaric cycle of birth and death. They preached until 12:30, ate the temple’s vegetarian lunch, and resumed preaching at 1:30. At 2:30 they took the road back to the WBHG, and it was 3:30 [by the time they returned].63

The householders of the brigade did not only intentionally distinguish themselves from secular urbanites dressed in the Western fashions of Shanghai’s commercial culture, whom they undoubtedly encountered while crossing the city in a crowded electric tram car. As the account emphasizes, they also stuck out even among the Buddhist worshippers and monks at Longhua Temple. Indeed, they were mistaken for Chinese Christians and, perhaps with some secret relish, observed the spontaneous scorn expressed for their Westernized religious competitors. However, the Chinese Christians that the WBHG Preaching Brigade was mistaken for could not have been the Western-suited Christians of the Shanghai YMCA, which functioned more as a social club than a religious mission. For all the socializing and networking that took place in the various groups, societies, and other activities at the WBHG, the overt purpose of its enterprises was derived from Buddhist soteriology. The householders of the WBHG presented themselves as working tirelessly to “extol the teachings of the Buddha, spread the Buddhist religion, save oneself and save others, and adorn the dharma world.”64 Activities like the brigade’s extemporaneous preaching brought into focus the WBHG’s complex set of cultural associations and distinctions by propelling householders out into the urban landscape, where their householder identity was put to the test through direct social interactions and conflicts.

RECEPTION OF HOUSEHOLDER IDENTITY

As President Shi’s speech at the opening ceremony had made evident to the WBHG’s members and supporters on that momentous occasion in the history of the Shanghai householder community, the cultural position of the WBHG was structured as a pair of differing associations and distinctions. On the one hand, the WBHG was to be distinguished from the “hot and noisy” environment of ancient temples by associating its new compound with the cosmopolitanism of commercial society. On the other, the WBHG was also to be distinguished from the disturbing secularizing trends of commercial society through its association with the religious discipline and numinous power of the Buddhist monastic community and its temples. This set of associations and distinctions was constructed by means of a range of social practices related to the design and function of space. The WBHG compound was spatially distinguished from temples by its Westernized architecture and mechanical clock, which associated it with commercial society. Functionally, this cultural position was reinforced by the compound’s housing of a modern urban voluntary association and careful attention to ceremonial decorum. The reverse cultural position, that of distinction from commercial society and association with temples, was established spatially by the inclusion of precisely the types of architecturally recognizable halls and facilities that were essential to the constitution of any temple, as well as by the deliberate investment of these halls and facilities with awe-inspiring numinous power. This second cultural position was also reinforced functionally by the WBHG’s daily ritual schedule, annual ceremonial cycle, and array of soteriologically significant activities and enterprises. As was perhaps most apparent when householders moved outside the WBHG compound and across the urban landscape, it was this complex pair of cultural distinctions and associations that gave the householder identity meaning in the specific context of early twentieth-century Shanghai. In a word, the spatial practices of the WBHG constructed householders as cosmopolitan religious devotees.

The clarity of this meaning and its attraction for Shanghai’s urban elite are evident in another account of the WBHG householders and their newly constructed space. Unlike the accounts analyzed in the foregoing, this account narrates the experience of an outsider and allows us to see how the cultural meanings of the WBHG were received through the eyes of an unaffiliated, external observer. “Taste of the Dharma” (Fawei 法味) is an essay written by the celebrated cartoon artist and writer Feng Zikai 豐子愷 (1898–1975) in August 1926, less than three months after the WBHG’s opening ceremony.65 At the time, Feng was living in Shanghai and in the early phase of his career when he received a letter from his former art teacher, Li Shutong, whom he had not seen for the six intervening years since he had initially gone off to study in Japan. As Feng knew from former classmates and friends, Li Shutong had left his teaching career behind, been ordained as a monk, taken the dharma name Hongyi 弘一, and become a renowned Buddhist master of Vinaya practice (i.e., the practice of the monastic disciplinary code).66 Curious about the dramatic transformation of his former mentor, Feng met with Master Hongyi in Hangzhou and then joined him to tour Shanghai for a few days in the summer of 1926. On the final day of their time together, the two were eating lunch at a vegetarian restaurant near the city god temple when Master Hongyi spoke of a certain householder called You Xiyin at the WBHG, whom he described as a pious believer who loved to do good works in society. Since nothing was planned for the afternoon before Master Hongyi’s scheduled departure back to Hangzhou, they decided to visit Householder You at the WBHG.

In his essay recounting these events, Feng describes in detail his experience at the WBHG:

The World Buddhist Householder Grove is a four-story67 Western-style building, extremely solemn [zhuangyan] and magnificent. The first floor is an expansive Buddha hall within which were high-quality seats and worship cushions, and the facilities were richly endowed. There were many pious men and women there worshipping the Buddha. Having been told that Householder You lived on the third floor, we went up the stairs. Here it was very quiet and everywhere on the walls were hung yellow signs that read “Walk slowly and keep your voice down,” which made one even more solemn upon seeing them. The third floor was all individual rooms. Master Hongyi recognized Householder You through a window and quietly knocked on the windowpane a few times. I then saw an elderly man of about fifty years in age open the door and come out. He did full prostrations at the master’s feet, as if he were almost going to embrace them. Master Hongyi gave a short bow, and I stood behind, stunned. When the elder man stood up and led me into the room, I finally regained my senses. I finally remembered that he [may have been] a lay disciple of Master Hongyi’s.

Originally from Wuxi, Householder You has done many charitable works in Shanghai and is quite a famous person. Even someone like me, who does not pay much attention to current events, had long heard his name. His demeanor, clothing, and all signs of lifestyle in his room were highly frugal, with little difference from those of Master Hongyi, who had “left home” [i.e., been ordained]. I now realized that householders are the most powerful propagators of Buddhism. Monks are oriented internally [within the Buddhist community], while householders are oriented externally. Householders are actually monks who have manifested themselves deeply in secular society to preach the dharma. When I first saw the extravagance of this Householder Grove’s architecture and facilities, I thought it was far off from the ascetic practice of a monk. Now seeing Householder You, I finally realized this [extravagance] is probably just an expedient means for secular [society].68

Upon arriving at the WBHG compound, Feng immediately noticed the spatial aspects that associated it with cosmopolitan commercial culture. These included the solemn decorum of the place as well as its Western architecture and lavish facilities. In fact, these “extravagant” features associated with Shanghai’s commercial culture initially led Feng to distinguish the WBHG from the sort of Buddhism practiced by his monastic companion, and roused in him a certain cynicism. This reaction might have turned him away had he not gone further to also recognize the other side of the WBHG’s cultural positioning. This occurred through his observation of Householder You. Feng immediately recognized the elite social status of this Shanghai notable, having seen his name prominently in the media. Yet what impressed Feng—himself a young member of Shanghai’s cultural elite—about You was precisely the obvious ways in which he differed from other elite urbanites and social celebrities: his frugal appearance, demeanor, and lifestyle. All this connected Householder You in Feng’s mind to the monastic master of disciplinary practice with whom he was traveling. It was only after realizing this second side of the householder cultural positioning that Feng came to a new understanding of the first: those extravagant aspects of the WBHG that associated it with commercial culture were precisely what made householders even more effective propagators of Buddhism than monks in the particular secularizing environment of Shanghai’s urban landscape.

Feng continued,

Householder You then guided us to ritually view the Reliquary Room. The Reliquary Room is a room for housing relics that is about twenty feet square. It has no window, the four walls are entirely inlaid with mirrors, and four electric lamps hang from the ceiling. In the middle is installed an ornate and brilliant red-lacquered and gold-decorated small stupa. On each of the four sides [around the stupa] are four worship cushions. From the bottom corners of the stupa are hung many small electric lights; in its upper portion a ball made of crystal has been installed, and in the ball it is said that there are relics. What kind of things are relics? Because I didn’t quite understand, they themselves didn’t elicit any feeling in me. But upon entering the room, I saw myself immediately transformed into millions of bodies—everywhere I looked there were millions of stupas, millions of electric lights, and I faced myself on every side. I felt dizzy and my heart palpitated; I was entirely pressed down into a mood of terror and willing submission. After Master Hongyi and Householder You had both made obeisance, we filed out of the room. We toured the Buddha-Recitation Hall and the Canon Room, then parted with Householder You and left. …

This day I saw Chengnan Caotang [i.e., another site in Shanghai] and experienced heartfelt compassion for the impermanence of human life and the unfathomableness of the law of karma. In the Reliquary Room, I again tasted a bit of vivid craving for Buddhism. These two days were very exciting, serious, and I also could not drink alcohol. As soon as I got home, I immediately called for someone to pour me a drink.69

Despite the characteristic humorous quip with which Feng concludes his account, he formally became a householder himself the following year in a ceremony officiated by Master Hongyi. A few years later he famously promoted Buddhist ethics through his widely popular publication Collected Drawings to Protect Life (Husheng huaji 護生畫集). Feng Zikai’s account of his visit to the WBHG, and the role it apparently played in his own conversion, demonstrates not only the successful communication of the compound’s cultural positioning of householder identity but also the strong attraction that identity held for Shanghai’s urban elite. The opportunity to become a cosmopolitan religious devotee possessed considerable appeal in a society that was deeply ambivalent about its own brand of modernity.

CHINESE URBAN CULTURE AND AMBIVALENT MODERNITY

The particular meanings of householder identity in 1920s Shanghai were undeniably shaped by the city’s specific cultural environment. Urban elites constructed these meanings in space through social practices that drew associations and distinctions with the salient features of an urban landscape that had been transformed by the cosmopolitan commercialism of China’s premier treaty port. This process was exhibited in the WBHG’s complex relationship to urban voluntary associations such as new-style native-place associations and the YMCA, and it can similarly be observed at Enlightenment Garden and the Merit Grove in their relationships to the new public parks and fashionable restaurants opening up across the cityscape. The prominent presence of such competitors representing cosmopolitan commercial culture in the urban environment provided householders with both the inspiration for their innovations in spatial practices and the motivation for their contentious cultural activism against the morally disconcerting trends of secularization and rampant consumerism. At the same time, it was the crowded urban conditions of China’s most populous city that set the basic conditions under which householders labored to find for themselves a meaningful communal religious lifestyle. The urban temples dotting Shanghai’s cityscape were qualitatively different from the famous remote monasteries that provided the model for Buddhist ideals of sanctity and discipline. Urban temples like Jing’an and Longhua smacked of the “hot and noisy” local “superstition” that the urbanite might imagine finding in the most parochial of villages. For these and other reasons, the urban temples were deemed unsuitable spaces for elites to construct their identity as householders. Yet such temples simultaneously represented the idea, however much they fell short of it, of establishing pure and numinous religious space in the heart of the crowded urban environment. In all these ways, then, the spatial construction of householder identity in Shanghai was profoundly shaped by the particular urban culture of China’s leading treaty port and largest metropolis in the 1920s.

This localized study also has implications beyond 1920s Shanghai for modern Chinese urban culture in general. In tandem with the spread of modern Buddhist periodicals and print culture described in chapter 3 in this volume, Shanghai’s householder spaces were replicated in cities across China throughout the Republican era. From the original founding of the WBHG as the SBHG in 1920 to the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, as many as one hundred eighty identifiable householder groves had sprung up in nearly every province of the country.70 The fact that these were overwhelmingly located in cities, and the largest were in treaty ports, suggests that the householder grove as a new type of organization was fundamentally suited to urban settings sharing many of the key cultural features common to Shanghai: foreign influence, modern commercialism, and a crowded urban environment. Although the meanings of householder identity in each of these geographically dispersed spaces of the Republican era undoubtedly derived from their own particular urban environments, there is evidence that the WBHG of Shanghai served as their predominant model for communal construction.71 Moreover, this model became a durable and adaptable fixture of Chinese urban culture that continues to thrive today. In mainland China, householder groves were temporarily expunged from the urban landscape during the Mao era (1949–1976) as part of the Communist Party’s wider assault on Buddhist institutions and ideology (discussed in chapters 5 and 6). However, since the 1980s many householder groves have been revived or built anew, alongside and sometimes in connection with the contemporary surge of less-elite forms of lay Buddhism (taken up in chapters 7 and 8).72 Outside the mainland, householder groves have spread internationally along with the Chinese diaspora, producing such prominent contemporary examples as the Kuching Buddhist Society (Gujin Fojiao jushilin 古晉佛教居士林) in Malaysia, the Singapore Buddhist Lodge (Xinjiapo Fojiao jushilin 新加坡佛教居士林), and the Ming Ya Buddhist Foundation (Mingyue jushilin 明月居士林) with branches in Oakland and Los Angeles, California. Shanghai’s householder community of the 1920s thus made a lasting contribution to Chinese urban culture that even to this day continues to contest and stand as counterevidence to secularizing trends in Sinophone urban communities throughout the modern world.

The spatial construction of householder identity in Shanghai also has broader historiographical implications for the study of Chinese modernity, evident in part in its connections to a wide range of other “traditional” cultural activities popular among urban elites in Republican China such as Daoist inner alchemy, morality or redemptive societies, the martial arts, and Chinese medicine.73 Householder Buddhism was part of a vast field of cultural production based in Chinese “traditions”—alchemical practices, spirit writing, moral cultivation, Chinese gymnastics, dietary regimens, breathing techniques—that shared a deep grounding in the world of late imperial Chinese religion. Moreover, these cultural activities were also connected at the social level through overlaps in leadership and adherents. Just to cite one notable example, Wang Yiting not only served as president of the WBHG from 1927 to 1937, he was also cochairman of the Shanghai Martial Arts Association and a member of the spirit-writing redemptive society known as the China Rescuing Life Association.74 Although it is rarely acknowledged in historical scholarship, Shanghai’s urban elite served as a central social matrix for the national promotion of traditional cultural activities throughout the Republican era. In the context of this cosmopolitan sector of Chinese society, however, these traditions became associated with aspects of foreign-defined modernity—modern voluntary associations, biological notions of the body, scientific hygiene, competitive sports, and so forth. Such associations implied a different worldview derived from the West and entailed critiques of the very traditions upon which these cultural pursuits were based, often phrased in terms of divesting them of their “superstitious” elements. Some scholars have taken this as evidence that the urban elite, moved by nationalist sentiment, were merely assimilating these traditional Chinese cultural activities into a foreign-defined modernity by thoroughly “scientizing,” or disenchanting, them.75 However, such an interpretation surely underestimates the strong resonance that the world of Chinese religion continued to hold for even the most cosmopolitan members of Chinese society.

As we have seen at the WBHG (and further exemplified by the Buddhist engagement with science discussed in chapter 2), the traditional cultural activities of Republican-era urban elites also critiqued the very aspects of foreign-defined modernity with which they were newly associated, often for being so materialist and competitive as to overlook the spiritual and ethical dimensions of human life. Shanghai’s Buddhist householders gave pride of place precisely to the numinous aspects of their compound, such as the Reliquary Room, and based their disciplined lifestyle on soteriologically derived ethics, leading to rebirth in the Western Paradise and final liberation from the samsaric world of birth and death. Indeed, such enchanted elements were central to the appeal of householder identity. Feng Zikai did not write that he enjoyed the “taste of the dharma” because it was Chinese, scientific, or modern; rather, for him, the appeal lay in the respect he held for the householder’s ethical discipline amid a world of materialistic luxury, as well as in the inexplicable visceral effect that he experienced in the Reliquary Room.

In other words, traditional cultural activities like householder Buddhism embraced diametrically opposed cultural associations without resolving the contradictions between them. The modernity represented by these activities was therefore structured by a fundamental ambivalence. This ambivalent modernity allowed a Chinese medical professional to simultaneously popularize Western germ theory and promote Chinese religious techniques for health and healing; it allowed the most vocal advocates of Western physical education regimens to simultaneously call for training all of China’s children in the traditional martial arts; and it allowed Shanghai’s biggest capitalists, like the Nanyang Brothers Tobacco Company founders Jian Zhaonan and Jian Yujie, to make a fortune revolutionizing Chinese commercial marketing through their ubiquitous cigarette advertisements while simultaneously claiming spiritual transcendence as Buddhist householders over the conspicuous consumption and profiteering of Shanghai’s commercial culture. Far from a state of indecision or weakness, “ambivalence” thus signals the remarkable ability of Shanghai’s urban elites to straddle both sides of cultural fault lines, accruing the strengths of both and the deficiencies of neither. Contrary to the conventional one-sided image of China’s urban elite as wholeheartedly embracing foreign-defined discourses under the irresistible pressures of semi- or hypercolonialism,76 householder identity suggests that Chinese urban modernity in early twentieth-century Shanghai was structured by a deep ambivalence that could simultaneously wield secular power in one hand and numinous power in the other.

I am grateful for the comments given on the workshop draft of this chapter by the discussants, David Faure and Gareth Fisher, as well as by members of the audience. I would also like to thank Jan Kiely for his suggestions for revision. The chapter was written with the generous support of a Residential Faculty Research Grant at the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley.

1. Grand Master Yansheng 演乘大法師, “Fojiao jingyeshe shiming” 佛教淨業社釋名 [Explanation of the name of the Buddhist Pure Karma Society], Jingye yuekan (Shanghai) 5 (August 1926), reprinted in Minguo Fojiao qikan wenxian jicheng bubian 民國佛教期刊文獻集成補編 [Supplement to the collection of Republican Buddhist periodical documents], ed. Huang Xianian 黃夏年, 83 vols. (Beijing: Zhongguo shudian, 2008) (hereafter MFQB), 17:5–16.

2. J. Brooks Jessup, “The Householder Elite: Buddhist Activism in Shanghai, 1920–1956” (PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 2010). On Republican-era Buddhist publishing, see chapter 3 in this volume; see also Jan Kiely, “Spreading the Dharma with the Mechanized Press: New Buddhist Print Cultures in the Modern Chinese Print Revolution, 1866–1949,” in From Woodblocks to the Internet: Chinese Publishing and Print Culture in Transition, circa 1800 to 2008, ed. Cynthia Brokaw and Christopher A. Reed, 185–210 (Leiden: Brill, 2010).

3. On the etymology of jushi, see Pan Guiming 潘桂明, Zhongguo jushi Fojiaoshi 中國居士佛教史 [A history of Chinese householder Buddhism], 2 vols. (Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe, 2000), 1:1–4.

4. For representative studies of Shanghai’s urban culture, see Leo Ou-fan Lee, Shanghai Modern: The Flowering of a New Urban Culture in China, 1930–1945 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999); Wen-hsin Yeh, Shanghai Splendor: Economic Sentiments and the Making of Modern China, 1843–1949 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007); Catherine Vance Yeh, Shanghai Love: Courtesans, Intellectuals, and Entertainment Culture, 1850–1910 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006); Sherman Cochran, ed., Inventing Nanjing Road: Commercial Culture in Shanghai, 1900–1945 (Ithaca: Cornell University East Asia Program, 1999); Wu Renshu 巫仁恕, Lin Meili 林美莉, and Kang Bao康豹 [Paul R. Katz], eds., Cong chengshi kan Zhongguo de xiandaixing 從城市看中囯的現代性 [An urban perspective on Chinese modernity] (Nankang: Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica, 2010).

5. Hanchao Lu, Beyond the Neon Lights: Everyday Shanghai in the Early Twentieth Century (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 11. For other recent studies that point to a pervasive ambivalence toward Shanghai’s modern cultural trends, see Jan Kiely, “Shanghai Public Moralist Nie Qijie and Morality Book Publication Projects in Republican China,” Twentieth-Century China 36, no. 1 (2011): 4–22; Mark Swislocki, Culinary Nostalgia: Regional Food Culture and the Urban Experience in Shanghai (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009).

6. Although criticisms of urban moral decay were not unprecedented in early periods of Chinese history, in the context of semicolonial Shanghai, they mixed with similar dystopic images of the modern city that had circulated globally since the turn of the twentieth century. See Gyan Prakash, ed., Noir Urbanisms: Dystopic Images of the Modern City (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010).

7. The Merit Grove Vegetarian Restaurant (gongdelin shushichu 功德林蔬食處) became a popular meeting place for Shanghai householders after opening in 1922, and Enlightenment Garden (jueyuan 覺園) became their public-event space of choice after its founding in 1926 to house the Shanghai Buddhist Pure Karma Society (Shanghai Fojiao jingyeshe 上海佛教淨業社); see Jessup, “Householder Elite.”

8. I understand any purposive activity carried out in a public communal setting to be a “social practice”; this includes banquets, meetings, and speeches but also religious rituals and even the design and construction of space itself.

9. “Zhina dajue jingshe shezhang Wang Yuji” 支那大覺精舍舍長王與楫 [China Great Awakening Vihāra president Wang Yuji], Haichaoyin 7, no. 4 (May 31, 1926), reprinted in Minguo Fojiao qikan wenxian jicheng 民國佛教期刊文獻集成 [Collection of Republican-era Buddhist periodical documents], ed. Huang Xianian 黃夏年, 209 vols. (Beijing: Quanguo tushuguan wenxian suowei fuzhi zhongxin, 2006) (hereafter MFQ), 165:121; “Ji bentang jiaowu lianhehui kaihui shi” 紀本堂教務聯合會開會事 [An account of a meeting of the Shangxiantang alliance], Shangxiantang jishi 8, no. 12 (December 1917): 38–40.

10. On lay Buddhist associations in the Song and Ming dynasties, respectively, see Daniel A. Getz Jr., “T’ien-t’ai Pure Land Societies and the Creation of the Pure Land Patriarchate,” in Buddhism in the Sung, ed. Peter N. Gregory and Daniel A. Getz Jr., 477–523 (Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 1999); Timothy Brook, Praying for Power: Buddhism and the Formation of Gentry Society in Late Ming China (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center, 1994), 103–7.

11. “Shanghai Fojiao jushilin zanxing guiyue”上海佛教居士林暫行規約 [Shanghai Buddhist Householder Grove provisional regulations], Haichaoyin 1, no. 5 (July 10, 1920), reprinted in MFQ, 148:127–28. Nianfo 念佛 refers to the practice of reciting the Buddha’s name (see also chapter 8), and releasing life (fangsheng 放生) refers to the practice of liberating animals from captivity.

12. For a more detailed analysis of the SBHG and more information on the Pure Karma Society (jingye she 凈業社), see Jessup, “Householder Elite.”

13. “Shijie Fojiao jushilin gangyao” 世界佛教居士林綱要 [World Buddhist Householder Grove outline], Shijie Fojiao jushilin linkan (Shanghai) (hereafter LK) 1 (March 1923): 2–6; “Benlin gexiang zuzhi gangyao (chongding)” 本林各項組織綱要(重訂) [Articles of the grove organizational outline (revised)], LK 13 (August 1926), reprinted in MFQ, 15:119–23. The World Buddhist Householder Grove Journal is an example of what Gregory Scott analyzes as a “society publication” in chapter 3 in this volume.

14. On Buddhism as a world religion, see Linda Learman, ed., Buddhist Missionaries in the Era of Globalization (Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 2005).