GREGORY ADAM SCOTT

In 1912 the scholar and journalist Liang Qichao 梁啟超 (1873–1929) wrote that “the establishment of the Republic of China was the result of a revolution of ink, not a revolution of blood.”1 Liang’s observation draws our attention to the important role played by print media, especially periodicals, in the political and cultural shifts that took place during the twenty-five years, from about 1895 to 1920, spanning the end of the Qing dynasty and the early Republican era. While xylographic (wood-block) publishing had already undergone its own period of development in the latter part of the Qing empire, the “revolution of ink” described by Liang was driven primarily by mechanized movable type and lithographic print technology, which had been introduced to China in the latter part of the nineteenth century.2 One of the most influential new publication genres was the periodical, which rose to a new prominence in Chinese print culture in precisely the transformative era from the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895 through the May Fourth Movement, originating in 1919.3 This chapter examines three Chinese periodicals dedicated to Buddhist content published in the second decade of the twentieth century and argues that through the print media, Buddhists were full participants in the intellectual and cultural transformations of this era.

The periodical—a genre that includes newspapers, journals, and newsletters—became a central conduit for ideas and a public marker of intellectual and cultural communities; certain publications such as New Tide (Xinchao 新潮) and New Youth (Xin qingnian 新青年) came to symbolize entire cultural groups or intellectual movements.3 Periodicals had three major strengths that distinguished them from other types of print media and placed them at the vanguard of social and cultural change during this era. First, they allowed a new level of access to content—informative, argumentative, commercial—through the inclusion of a wide range of contributors, genres, and forms, such as serialized essays, translations, as well as images, including photographs and artistic depictions.4 Second, they created new networks of information by reporting on news of current events, either supplied by the publication’s own journalists or reprinted from another source; and, by featuring catalogs and advertisements for related publications in print, they linked together localities into national markets for information and other cultural products.5 Finally, they facilitated social organization by providing associations and other social groups with a platform to publicize their activities and communicate with their membership. Although print had fulfilled each of these functions to varying degrees in the past, the new technologies, markets, and genres such as the periodical made the print culture of modern China capable of assuming a much more powerful role as a driver of both public and elite culture than had ever been possible before. This role only expanded as the scale and speed of print production grew and as rising rates of education and functional literacy were met with a wider use of modern vernacular language in print.6

Religious texts had always been a core component of Chinese print culture, and in the modern era religious groups were at the forefront of those who embraced new print genres and technologies. These included missionary and indigenous Christian groups, Daoists, popular cults, as well as Buddhists.7 After the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864), which had so badly damaged the production and circulation of Buddhist texts in the Jiangnan area, Buddhist print culture in China was greatly revived in the late nineteenth century when lay publishers such as Yang Wenhui 楊文會 (1837–1911) and monastics like Miaokong 妙空 (1826–1880) set up wood-block presses outside the network of established temple scriptoria.8 The Chinese Buddhist “revolution of ink,” however, would truly come to fruition in the early twentieth century when scriptural presses and distributors were joined by commercial presses and specialist publishers producing Buddhist works using mechanized movable type. This involvement of commercial presses in Chinese Buddhist publishing made possible the creation of Chinese Buddhist periodicals, since their editors and publishers had already been printing commercial and literary periodicals and added the Buddhist-themed works to their catalogs.9 Chinese Buddhist periodicals were not, however, simply adaptations of a literary-commercial genre to a religious mode. Their content was closely modeled on the Buddhist textual past and included scriptural exegesis and commentary (jianzhu 箋注), biographies of monastic and lay figures (zhuan 傳), travel diaries (youji 遊記), and other types of texts. Additionally, they were also preceded by a number of Japanese Buddhist periodicals, which had appeared as early as 1889.10 While many of the leaders of the Chinese Buddhist periodical press had studied in Japan, and a number of articles on topics such as Buddhist history and lexicography were translated from the Japanese, the direct lines of such influence have yet to be uncovered.

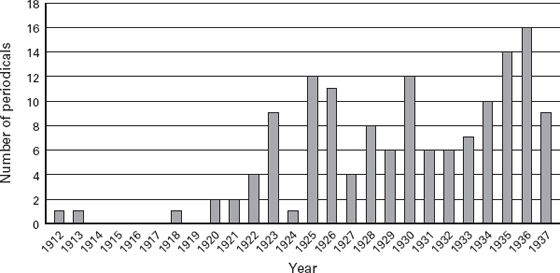

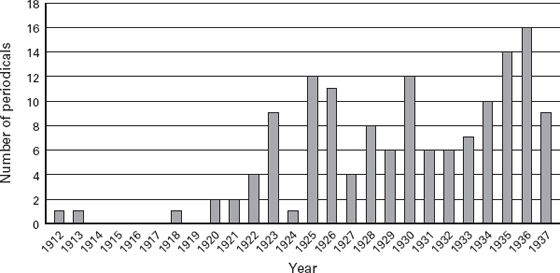

In the first two decades of the twentieth century there were three Chinese Buddhist periodicals in print, all of which ended their print runs due to financial or other internal factors. Yet this handful of pioneering works would be followed in the 1920s and 1930s by hundreds of Buddhist periodicals, and though most of them were similarly short-lived, by the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, the periodical would be one of the most prolific and widely distributed forms of Buddhist print culture in China (figure 3.1).11 In this chapter I briefly review the three Chinese Buddhist periodicals published between 1912 and 1919. I have chosen to focus on these early examples for several reasons. First, they were groundbreaking efforts that adapted what was primarily a literary and journalistic genre to a religious-themed medium. The choices made in their adaptations established authoritative precedents for later Buddhist periodicals to follow. Many of the most prolific editors and writers contributed to several of the largest periodicals, thus exerting an abiding influence on later eras of publication. Second, these periodicals appeared during a highly tumultuous historical period when the people driving Buddhist “modernity” were still in the process of formulating their intellectual and social strategies. The perspectives expressed in these works are thus invaluable to our understanding of this formative era. It was also a time during which Chinese Buddhist print culture, both xylographic and movable type, was undergoing rapid development, a phenomenon reflected in the publishing-related articles and lengthy catalogs that appeared in periodicals of the time. Finally, these periodicals played a crucial early role in the formation of modern Buddhist social organizations in China, serving as the public face of religious associations and helping to cement the media influence of prominent figures.

FIGURE 3.1 Chinese Buddhist periodicals established in the period 1912–1937

Apart from their importance to a specifically Buddhist history of modern China, however, these periodicals are also highly significant as points of contact between Buddhism and larger narratives of social history in modern China. People in Buddhist circles (Fojie 佛界) were neither exclusively religious practitioners nor only Buddhist: they were publishers, authors, industrialists, Daoists, devotees of popular religious sects, and so on. Not only did they embrace the periodical genre for many of the same reasons political, literary, and other publishers did but they were also often simultaneously publishers of those types of periodicals as well. We can thus make no clear separation between a Buddhist history of publishing and periodicals and a non-Buddhist one, even though in many cases the Buddhist aspects of these figures’ identities have, for a variety of reasons, since been effaced. To read through these periodicals is to see one more aspect of the intense ideological and social struggles that were playing out in a number of periodical publications and that drove phenomena such as the May Fourth Movement that have had an enduring impact on Chinese society.

These early Chinese Buddhist periodicals each helped to establish a particular archetype for those that were to follow. These archetypes were

1. the literary miscellanea, which features primarily essays from a number of contributors with no single institutional connection, typified by Buddhist Studies Magazine (Foxue congbao 佛學叢報, 1912–1914);

2. the association organ, which speaks for and functions as the official publication of record for a Buddhist association with national or regional aspirations, here typified by Buddhist Monthly (Fojiao yuebao 佛教月報, 1913); and

3. the society publication, which plays a similar role as the association organ but on a smaller scale, with more connections to outside organizations and greater variety to its content, typified by Awakening Society Collectanea (Jueshe congshu 覺社叢書, 1918–1919).

It must be emphasized that individual periodicals often fell into more than one of these archetypes, and the boundaries between them were in practice quite fluid, yet thinking of periodicals in terms of these categories does highlight some of the major roles that periodicals played among Chinese Buddhists in the early twentieth century. They also help reveal the strengths that the periodical genre brought to modern Chinese print culture, strengths that made these periodicals particularly attractive investments for cultural leaders of many stripes.

THE LITERARY MISCELLANEA: BUDDHIST STUDIES MAGAZINE

The first Chinese-language Buddhism-themed periodical was Buddhist Studies Magazine, published for twelve issues between October 1912 and June 1914. Founded by a professional journalist with a personal interest in Buddhism, it featured editorials on Buddhist subjects, serialized scholarly works, news on recent political and local developments, poetry, biographies of eminent figures, and advertisements for Buddhist publications. While its format and structure were similar to those of other literary magazines and newspapers then being published in Shanghai and elsewhere, its focus on Buddhism was a novelty among Chinese periodicals. In Chinese Buddhist print culture, it was among the first publications to feature photographs, including depictions of recently living and contemporary monastic figures. It was an example of an open-context, magazine-format Buddhist periodical without a single doctrinal or institutional affiliation that combined an eclectic series of contributors with content that was intended for a wide readership. As such, it sought to bring Buddhist-themed material to the public to inform readers about current events relating to Buddhism and to connect them to a world of printed Buddhist texts.

The founder of Buddhist Studies Magazine was the journalist and publisher Di Chuqing 狄楚青 (1872?–1941). Di had cofounded the Times newspaper (Shibao 時報), recognized as “the most influential reform organ of its day.” He had previously studied in Japan and been involved in promoting political reform alongside such well-known figures as Tan Sitong 譚嗣同 (1865–1898) and Liang Qichao. In 1904, Di and Liang began publishing the Times through his newly established Youzheng Press 有正書局 in Shanghai, seeking to advance the cause of political reform through nonviolent means.12 Around 1908, the year Di was elected to the Jiangsu Consultative Assembly, he opened branch offices in Beijing and Tianjin. The press would eventually expand to have more than twenty branches. It was during this time of rapid intellectual and political change that Di became involved with Buddhism. He had met the scriptural publisher Yang Wenhui sometime before Yang’s death in 1911. Then, in 1912, an encounter with the Chan monk Yuexia 月霞 (1858–1917) during the cleric’s visit to Shanghai prompted Di to take part in establishing a scripture-lecture group (jiangjing hui 講經會). In his autobiographical Notes from the Pavilion of Equality (Pingdeng ge biji 平等閣筆記, 1913), Di notes his impressions of religious subjects and treats Buddhism favorably in comparison with other religions. His personal practice appears to have been directed toward Buddhist Pure Land (jingtu 淨土) teachings. The timeline of his encounter with Buddhism neatly precedes his founding of Buddhist Studies Magazine in the latter part of 1912. Still, it is difficult to determine the extent of his influence on the periodical, since the only article attributed to him is a single essay reprinted from Notes from the Pavilion of Equality. What is clear is that, since the magazine was published by Di’s Youzheng Press, it was sold in Shanghai, Beijing, and Tianjin and, from the second issue onward, distributed by the Jiangxi Buddhist Studies Association in Nanchang as well.13

The structure and style of Buddhist Studies Magazine remained consistent over its two-year print run. It was printed in letterpress, averaging one hundred eighty pages per issue with a lithograph-printed cover. Its content was divided into thematic sections, of which the pictorial (tuhua 圖畫) section, which appeared immediately following the table of contents, was especially striking (figure 3.2). Images were reproduced in monochrome lithography, with subjects ranging from religious paintings and portraits of living monks to Buddhist historical sites in India, Tibet, Thailand, Myanmar, China, and Japan; but the selection of subjects was unrelated to the content of the particular issue in which they appeared. A few were portraits of living or recently active Buddhist figures such as Yang Wenhui, Jichan 寄禪 (1852–1912), the Japanese monk Shaku Unshō 釋雲照 (1827–1909), Dading 大定 (1824–1906), Dixian 諦閑 (1858–1932), Yekai 冶開 (1852–1923), and Miaokong.14 Lithographic printing made possible the reproduction of images in unprecedented detail and verisimilitude, and at the time it would have been quite expensive to include such reproductions in a periodical. The photographic representation of Buddhist figures was a new element in China, one that carried the imprimatur of modernity from this new type of technology and yet was also closely linked to traditional devotional and biographic portraiture.15 Following the pictorial section, textual articles were organized into sections by genre, the order of which varied slightly from issue to issue. “Editorials” (Lunshuo 論說) appeared first, and while political topics dominated this section in early issues, later ones tended to focus on questions of Buddhist doctrine. “Scholarship” (Xueli 學理) followed, often accompanied by “History” (Lishi 歷史), and usually featured long-form essays that were serialized across several issues. “Special Matters” (Zhuanjian 專件) often contained public statements or letters from the nascent Buddhist associations, while “Current Events” (Jishi 紀事) reprinted short pieces on Buddhism from other news sources.16 “Miscellaneous” (Zazu 雜爼) is where serialized articles appeared, while a few other sections featured in some but not all issues.17

FIGURE 3.2 Monochrome lithograph-printed photographs from Buddhist Studies Magazine, no. 6 (May 1, 1913)

A list of “General Regulations” (Fanli 凡例) for the periodical set out the intent of these sections, stating that their content would be limited to Buddhist studies and would “not touch upon the ways of the world” (bushe shifa 不涉世法). The “Editorials” section, prominently placed at the start of the textual sections, was particularly directed toward nonspecialist readers:

Yet for the sake of those who are unlearned in Buddhist studies, or those who criticize the application of Buddhist studies to worldly truths, [we] thus establish a standard of plain and simple writing. In composition seek only clarity, don’t use deep principles or abstruse language to “startle the world and shock convention.”18

The breadth of its intended audience was reflected in the periodical’s “Inaugural Statement” (Fakan ci 發刊辭) in the first issue. Its author, general editor Pu Yisheng 濮一乘 (dates unknown), a little-known figure who is uncredited in the publication itself,19 describes the magazine as “encouraging the improvement of humanity and safeguarding the peace of the world.” Pu’s statement proclaimed that the spread of knowledge through the periodical would not only benefit humanity and encourage world peace but also mirrored the function of the dharma assemblies of the past, such as those convened on Vulture Peak (Jiuling 鷲嶺) by Śākyamuni, and those of the future—namely, the Dragon Flower Assembly (longhua zhi hui 龍華之會) of the Buddha Maitreya.20 By using the idiom of preaching, Pu portrayed the function of the periodical as expounding the truth to an audience consisting—as was the group assembled at Vulture Peak—of beings from a variety of backgrounds and possessing a range of capabilities. The image of the diverse audience of the Buddhist scriptures was thus evoked in parallel with that of the broad reading public of the modern print market.

Such diversity was also a feature of the contributors to the magazine, who were monastic and lay Buddhists from a variety of backgrounds; many of them would later rise to prominence. The Chan monk Yuexia, whose recorded lectures on the Vimalakīrti Sūtra (Weimojie suoshuo jing 維摩詰所說經) were serialized in issues 5–12, was then teaching at Huayan University, a Buddhist seminary in Shanghai.21 Similarly, several transcribed lectures by the Tiantai monk Dixian were featured in the magazine; at the time, Dixian was in Ningbo establishing the Guanzong Research Society (Guanzong yanjiu she 觀宗研究社), a Buddhist seminary and academy.22 During the first few months of the magazine’s run, the former revolutionary turned monk Zongyang 宗仰 (1861–1921), who was supervising the completion of the first letterpress Buddhist canon printed in China, the Kalaviṇka Canon (Pinjia da zangjing 頻伽大藏經), contributed a series of articles on his work.23 Even Yinguang 印光 (1861–1940), a famously reclusive monk later credited with reviving the Pure Land school in China, had several articles published in the journal under the pseudonym Changcan 常慚 (Ever Ashamed). He subsequently rose to national renown after the Beijing-based lay Buddhist Xu Weiru 徐蔚如 (1878–1937) read these articles, contacted Yinguang, and in 1917 financed the publication of a collection of his correspondence.24 Lay contributors to the magazine included Luo Jialing 羅迦陵 (1864–1941), the wife of the Shanghai tycoon Silas Hardoon and the sponsor of the Kalaviṇka Canon,25 Cai Yuanpei 蔡元培 (1868–1940), then minister of education in Beijing,26 Ouyang Jian 歐陽漸 (1871–1943), manager of the Jinling Scriptural Press (Jinling kejing chu 金陵刻經處) founded by Yang Wenhui,27 and Li Yizhuo 李翊灼 (1881–1952), a scholar who had helped catalog the Dunhuang manuscripts.28 Although these authors had widely different backgrounds and doctrinal affiliations, many of them were united through a shared involvement with publishing or education projects of their own.29

Several important features can be discerned in the contents of Buddhist Studies Magazine. First, many articles were quite long and serialized across several issues, such as “A Clear Outline Discourse on the Dharma-Nature School” (Faxing zong minggang lun 法性宗明綱論) by Li Duanfu 黎端甫 (dates unknown) and Yuexia’s “Recorded Discourses on the Vimalakīrti-nirdeśa-sūtra” (Weimojie suoshuo jing jiangyi lujuan 維摩詰所說經講義錄卷).30 These articles, rather than taking advantage of the rapid turnover possible with periodical printing to present up-to-date news or other information, instead offered the reader a nearly book-length work in several cases, as well as a reason to continue reading the periodical, and perhaps purchasing subsequent issues. Second, a number of articles were translated from the Japanese, including “Questions and Answers on Buddhist History” (Bukkyō rekishi mondō 佛教歷史問答) by Nagai Ryūjun 永井龍潤 (dates unknown) and “A Brief History of Buddhism in the Three Kingdoms” (Sankoku Bukkyō ryakushi 三國佛教略史), originally published in 1890 by Shimaji Mokurai 島地墨雷 (1832–1911) and Oda Tokunō 生田得能 (1860–1911).31 It is likely that editors and translators such as Di Chuqing and Zongyang, both of whom had studied in Japan, were comfortable incorporating Japanese Buddhist scholarship through translation into their periodical. It is also possible that Japanese Buddhist periodicals, of which there were many published from the Meiji period onward, exerted an unacknowledged influence on Chinese Buddhist periodicals.32 Third, the “Special Matters” section served as a venue of communication for the Chinese Buddhist associations then just being organized, which would often report on their dealings with state authorities. The first issue featured the constitution of the Chinese Buddhist General Association (Zhonghua Fojiao zonghui 中華佛教總會) (CBGA) published in full, as well as a news item regarding Ouyang Jian’s rival Chinese Buddhist Association (Zhongguo Fojiao hui 中國佛教會), which attempted to block government recognition of the CBGA.33 Finally, the “Current Events” section often featured reports of conflicts between Buddhist temples and state officials. In the first issue, for example, one such report describes how the magistrate of Wuxing county had accepted a formal request from the Zhejiang-Jiangsu branch of the CBGA regarding the return of temple property that had been seized under the slogan of “Promoting education.” During a period when religious properties were being seized indiscriminately, such news was valuable for Buddhist groups seeking to ensure their continued existence.34 Periodicals carrying such current information helped to centralize the mobilization of support for embattled temples. They often published open letters from Buddhists to government officials requesting their intervention to safeguard their religious livelihood.

While pieces on news and current events helped to link together local temples and larger associations into a social network, Buddhist Studies Magazine was equally an important medium for linking the reader to the growing realm of scriptural texts and formed one node in a nationwide print distribution network for Buddhist publications. Several Buddhist xylographic scriptural presses (kejing chu 刻經處) had been established thanks to the influence of Yang Wenhui’s pioneering publishing work, and in the years to follow Buddhist scripture distributors (Fojing liutong chu 佛經流通處) would emerge as a central feature of Chinese Buddhist print culture, particularly in the 1920s and 1930s.35 The magazine often featured lists at the end of each issue of Buddhist books and printed images for sale, with its catalog of Buddhist scriptures growing in size throughout its print run, until, by 1914, more than six hundred titles were on offer.36 In the first issue, advertisements included one for a monochrome and another for a five-color printed scroll of the Guiding Image of Amitābha Buddha of the West, as well as another advertisement for three scriptural texts.37 Issues 7 and 8 featured catalogs from the Changzhou Tianning Temple Scriptural Press (Changzhou tianning si kejing chu 常州天寧寺刻經處), while issue 10 opened with an advertisement for scriptures published by the Hunan Buddhist Studies Association (Hunan Foxue hui 湖南佛學會).38 Most scriptural titles on offer were credited to the Haichuang [Temple] Scriptorium (Haichuang [si] jingfang 海幢[寺]經坊) in Guangzhou, though there were also titles published by the Youzheng Press itself. By acting as a distributor of texts, the Youzheng Press could offer readers, via its Buddhist periodical, a much greater breadth of choice than any individual scriptural press. For example, the one hundred twenty or so titles listed in the Jinling Scriptural Press catalog issued in 1902 are dwarfed by the six hundred or more entries for the Jinling, Yangzhou, Changzhou, and other scriptural presses listed in issue 12 in 1914.39 These extensive listings enabled the periodical to function as a gateway for readers into a much wider field of Buddhist printed material. The mentioned Kalaviṇka Canon project was also featured prominently in the periodical. Articles contributed by its chief editor, Zongyang, and its patron, Luo Jialing, updated readers on its current status, while notices beginning in issue 4 (February 1, 1913) encouraged readers to order copies directly from the publisher. The completion of the canon was announced in issue 11, and the final issue featured more advertisements for it as well as a detailed article about its content and scope.40

Buddhist Studies Magazine abruptly ended publication in June 1914. Although officially a monthly periodical, there were many months in which it was not published owing to material shortages and labor difficulties. A late-planned switch to a bimonthly format and reduced price evidently were not enough to save the publication.41 In spite of its short life span, however, it had opened the way for a new type of Buddhist publication in China, bringing content from a wide variety of contributors to a broad audience, an approach emulated by a number of periodicals that followed in later decades. Many of these later periodicals would model their structure and content closely on this magazine. It also presented Buddhist teachings in a format reminiscent of literary journals and social magazines, one that was designed to be more approachable to beginners and nonspecialists than a scripture or other formal Buddhist text. In reaching out past the elite, learned Buddhist circles to a broader audience, Buddhist Studies Magazine signaled the power of the periodical genre to reach new types of readers and to encourage the creation of an inclusive community among them. Such a model was, however, only one of several that were explored by early Buddhist periodicals.

THE ASSOCIATION ORGAN: BUDDHIST MONTHLY

Following the emergence of the Nanjing-based Chinese Buddhist Association in 1912, the rival Chinese Buddhist General Association was founded as a pan-Chinese Buddhist organization in Shanghai in April 1912. It was intended to include all Chinese Buddhist monks and nuns as members, and while its active membership never exceeded a small group of committed association leaders, it was the first national Buddhist organization to receive official recognition.42 Its founder and first president was the Chan monk Jichan, and its second president was Yekai, who, when elected in March 1913, had recently retired as abbot of Tianning Temple 天寧寺 in Changzhou. Funding for the association was to be raised through a stock issue totaling thirty thousand yuan, and local branches of the association would be responsible for selling shares. Most association work was conducted at Qingliang Temple 清涼寺 in Shanghai, and planned projects involved mostly the use of print media. This included the establishment of a book exhibition, a printer, a text-compilation society, a scripture distributor, and a periodical.43 The Monthly Journal of the Chinese Buddhist General Association (Zhonghua Fojiao zonghui yuebao 中華佛教總會月報), generally referred to as Buddhist Monthly, was published for only four months in the spring and summer of 1913. The association sold the first issues of its journal and subsequently sent copies to branch offices to be distributed to shareholders. Printing was handled by National Glory Press (Guoguang shuju 國光書局), which specialized in reproductions of historical paintings, calligraphy, and rubbings.44

Buddhist Monthly was designed to function as a mouthpiece for the leaders of the Chinese Buddhist General Association, particularly Taixu 太虛 (1890–1947), who was both the editor of and a major contributor to the publication.45 Although its basic structure followed that of Buddhist Studies Magazine, Buddhist Monthly was supported by a religious organization rather than a commercial publishing house. The popularity of this type of association organ reflected the central role that publications played in the operation of this type of religious association, helping it to establish a concrete foothold in the public realm. Periodicals such as Buddhist Monthly not only serve as a window into the inner workings of these religious groups but also demonstrate how closely these periodicals were linked to their parent organizations, as they strove to engage with the public, broadcast their ideology, promote their plans, and connect their leadership to both their memberships and the public at large. Consequently, as the CBGA faded into obsolescence, so did the periodical, shrinking in number of pages with each issue.

In its inaugural issue, three “Inaugural Publication Announcements” (Fakan ci 發刊詞) describe the aims of the publication. The first, by Yakun 亞髠 (dates unknown), emphasizes Buddhism’s important place as part of China’s long history and urges that religion must change with the times, just as China’s political system had changed in recent years.46 The second was written by Li Duanfu, who had also contributed an article to Buddhist Studies Magazine. In his contribution, he foresees that, although many people are biased against Buddhism and doubt the scriptures, the periodical will have a positive impact on this situation by explicating Buddhist doctrine and educating the four assemblies of monks, nuns, laymen, and laywomen.47 Both essays recognize that the revolutionary changes in Chinese society of recent years had produced both dangers and opportunities for Buddhists: there was the danger of being swept aside by the antireligious forces operating under the banner of “modernization” but also the promise that new types of Buddhist associations and publications could empower monastics and laypersons. The third announcement, by Qinghai 清海 (fl. 1914–1937), repeats the warning that the Buddhist teachings are in danger as well as the assertion that Buddhists can play a positive role in the larger context of national salvation by helping to establish a strong society.48 Just as with Buddhist Studies Magazine, the framing intent of this periodical makes reference both to the rapidly changing social and political culture of the times and to the role that the Buddhist teachings can play in the modern world. The vision is thus one of participation in worldly matters such as social or political questions, although the periodicals would still be squarely focused on Buddhist topics.

The general manager of Buddhist Monthly was the monk Qinghai, who had served as vice president of the CBGA since its founding and had had a long-standing association with Qingliang Temple in Changzhou.49 Two editors are credited, one of which, Taixu, later became among the best-known Buddhist figures of Republican China. Just the previous year, in 1912, Taixu had led an unsuccessful attempt to take over Jinshan Monastery 金山寺 outside Zhenjiang (Jiangsu province) in the hope of transforming it into a modern Buddhist seminary. Subsequently, Jichan had invited him to help establish the CBGA.50 Taixu’s comrade in the Jinshan incident, Renshan 仁山 (1887–1951), was also a founding member of the association and contributed to the periodical. Yuanying 圓瑛 (1878–1953), who had previously studied with Yekai and Jichan, contributed several articles, mostly regarding association and commemorative events. Last, there were a number of contributors who also wrote for Buddhist Studies Magazine, including Li Duanfu, Zongyang, and Gao Henian. The themes and style of their articles in the two publications were similar. Gao, for example, contributed the travelogue “Record of Visits to Famous Mountains” (Mingshan youfang ji 名山遊訪記) to Buddhist Studies Magazine and another record of travels, “Notes of Clouds and Water” (Yunshui biji 雲水筆記), to Buddhist Monthly.51

The structure of Buddhist Monthly generally mirrored that of Buddhist Studies Magazine, with the addition of a few subsections.52 The bulk of its content was related to association business and activities, including the images at the front of every issue, mainly portraits of individual members and commemorative photographs of association meetings. The lengthy lists of regulations, charters, and committee resolutions of the group were reprinted in the periodical in full, and charts detailed the locations and staff of the various local branch associations.53 Pieces of official communication between the association and government officials and announcements to local groups reminding them of their duty to sell copies of the journal and to submit news and other content to the periodical office were also included.54 As with the notices of temple-government disputes in Buddhist Studies Magazine, the CBGA organ served to facilitate communication about current events. However, in contrast to the decentralized network drawing from a wide range of sources of Buddhist Studies Magazine, the CBGA’s intent was to have a centralized information hierarchy, with published material and decrees flowing downward through the periodical to association branches, and reports and funds sent back up to the association leaders. By the second issue these announcements from the association leaders were appearing immediately following full-page section breaks, greatly increasing their visibility to readers.55 Unlike with Buddhist Studies Magazine, however, most Buddhist Monthly articles were written in formal, classical language, with the main text in large-format characters followed by explanatory and discursive notes in a smaller, column-width font.

One major development evident in Buddhist Monthly during its brief four-month print run was the increasing influence of Taixu. Articles written by him appeared from the first issue, and in issue 4 there were two special notices appearing under his name that announced two of his forthcoming articles planned for issues 5 and 6. Previously all such notices had been issued only by the association.56 Later in the fourth issue another short notice by Taixu stated that whereas the “Essential News” (Yaowen 要聞) section had not previously been edited by him, from this issue onward he alone would be the editor of all the articles and news in the entire journal.57 These notices hint at serious disagreements among association leaders, which was perhaps one of the factors that led to the dissolution of the association not long after the periodical ceased publication. The CBGA and Buddhist Monthly were so closely linked that when the association failed, the periodical also closed. Its history demonstrates how periodical publishing could be used to change the way that information and news were shared among Buddhists. In this case, it was undertaken in an attempt to centralize that communication into an institutional hierarchy. Such a structure looked orderly and comprehensive on paper, but it was difficult to implement in actuality. Publishers could not, after all, force people to read their periodicals, and the best they could do was to require their local branches to distribute their publications. Yet Buddhist Monthly was part of Taixu’s early experience with the power of print, and, while the periodical itself fizzled out, Taixu and others would later succeed in gaining exposure and influence through mastery of the genre.

THE SOCIETY PUBLICATION: AWAKENING SOCIETY COLLECTANEA

Although there were dozens of Buddhist monographs and scriptural editions published in China between June 1914 and October 1918, there were no Chinese Buddhist periodicals in print during this period. The genre was revived with the appearance of Awakening Society Collectanea, published quarterly for five issues from October 1918 to October 1919.58 As the official publication of the Awakening Society (jueshe 覺社), a Buddhist society based in Shanghai, the periodical was intended to “establish the Buddha dharma as its broad platform, select ancient and modern, Eastern and Western religious scholarship, and form a compendium of wisdom from all the philosophies. Truly it shall be the only storehouse of great radiant brightness in the world.”59 Although its function was similar to that of its predecessor, Buddhist Monthly, the scope of its content was substantially wider and included more scholarly articles and translated works, as well as links to a range of Buddhist publications. Rather than serving an association with national pretensions, Awakening Society Collectanea had more of the variety exhibited by Buddhist Studies Magazine, was much more open to cooperating with other periodicals and Buddhist publications, and even carried advertisements for non-Buddhist books sold by its printer. As with Buddhist Monthly, the periodical was closely linked to a parent organization, but it presented ideas and information that was much more open, accommodating, and interconnected across local and institutional boundaries. This pattern would prove popular since no organization was able to claim national authority over all Buddhists in China for the remainder of the Republican era. Whereas Di Chuqing and others published their magazines to reach a broad audience, and the CBGA used its publication as a mouthpiece, the Awakening Society saw its journal as part of a larger print strategy that was neither entirely open context nor group exclusive in its approach.

After the collapse of the CBGA in 1913, Taixu went into sealed confinement (biguan 閉關) for meditation and study on the island of Putuoshan from 1914 to 1917, after which he embarked on a tour of Japan, Taiwan, and Southeast Asia. Returning to Shanghai in 1918, he founded the Awakening Society in consultation with a group of Buddhist laymen, including the scholar and revolutionary Zhang Taiyan 章太炎 (1868–1936) and Wang Yiting 王一亭 (1867–1938,) a prominent lay Buddhist, artist, and industrialist.60 The “awakening” in the society’s name was explained as referring to self-awakening, awakening others, and awakened action. The society’s purpose was to sponsor publications and work toward the reform of the Buddhist monastic community. Members signed a pledge, and upon joining were required to take formal refuge in the Three Jewels, accept the precepts, and participate in Buddhist study. A range of other activities were open to members, including meditation, recitation of the Amitābha Sūtra (Amituofo jing 阿彌陀佛經), paying obeisance to Buddha images, and repentance rituals. All members were to gather together for one week twice a year, once to recite the Buddha’s name and again to meditate. On October 28, 1918, the society conducted the first of a planned series of lectures on Buddhist topics and published the first issue of Awakening Society Collectanea.61 By January 1919, a branch association had been opened in Hankou, and it was around this time that the group was reorganized into four departments, three of which were devoted to printing and distributing Buddhist publications.62

Publishing and the promotion of Buddhist texts made up a substantial part of the association’s activities. In several issues of the periodical, the association advertised three Buddhist books that were being offered for free if postage was paid. It also provided a list of “good books” (liangshu 良書), all of which were recently published titles by the Shanghai Medical Press (Shanghai yixue shuju 上海醫學書局) of Ding Fubao 丁福保 (1874–1952).63 Some of the society’s earliest accomplishments in 1918 were the publication of two works by Taixu, A Balanced Discourse on Ethics (Daoxue lunheng 道學論衡) and Collected Discourses on the Śūraṃgama-sūtra (Dafo dingshou lengyan jing shelun 大佛頂首楞嚴經攝論). These were later advertised in the pages of the journal and distributed by Zhonghua Books (Zhonghua shuju 中華書局), which was also responsible for printing the periodical.64 Zhonghua had been founded by a former editor at the Commercial Press (Shangwu yinshu guan 商務印書館), and from 1912 to 1918 it was issuing eight major periodicals, including Liang Qichao’s journal Great China (Da Zhonghua 大中華). Although Zhonghua’s 1920 catalog listed no religious works, and its 1927 catalog had only four titles in that category, notices published in Awakening Society Collectanea stated that branches of Zhonghua Books as well as Buddhist Scriptural Distributors (Fojing liutong xhu 佛經流通處) were distributing the periodical as well as the two monographs authored by Taixu.65 The periodical’s range of distribution eventually extended beyond the realm of Zhonghua Books; by the third issue, in April 1919, it was also being carried by scripture distributors in Beijing, Hong Kong, Chongqing, Ningbo, Nanjing, Yichang, Changzhou, and Changsha.66 Distribution was thus linked to both the commercial Zhonghua Books network and the nonprofit Buddhist-scriptural networks.

Two major article contributors were also founding members of the Awakening Society: Chen Yuanbai 陳元白 (1877–1940) had been a military commander in the Republican Revolution of 1911 before heading to Japan after the political turmoil of the years immediately following. After returning to China, he joined the redemptive society Tongshanshe (同善社) and began practicing meditation.67 Huang Baocang 黃葆蒼 (1884–1923) had also studied in Japan, where he had joined the Revolutionary Alliance (tongmenghui 同盟會), and had served in the Qing military before joining the 1911 Revolution. He and two other friends were later tonsured in Ningbo, where Huang took the name Daci 大慈.68 Although he did not write for the periodical, Jiang Zuobin 蔣作賓 (Jiang Yuyan 蔣雨岩, 1884–1941), a fellow former Revolutionary Alliance member and a graduate of a Japanese military academy who had served in the tumultuous Beijing-based government of the early post-Revolution years, was also involved in the founding of the society.69 In the summer of 1918, these three men, all with revolutionary and military backgrounds and experience in Japan, had traveled together to Putuoshan, where they heard Taixu preach and suggested to him the idea of founding the Awakening Society in Shanghai.70 Huang’s article “Buddhism and Human Conscience in the World after the European War” (Ouzhan hou shijie renxin yu Fojiao 歐戰後世界人心與佛教), an essay on the special salvific power of Buddhism, would later be included in a 1923 edition of selected articles, as well as a 1925 issue of another Buddhist periodical.71

The general arrangement of sections in Awakening Society Collectanea mirrored that established by the two earlier Buddhist periodicals, adding only a section on “Office Matters” (Lushi 錄事) at the end of each volume to report on the society’s activities. Many of its photographs were portraits of association members; famous Buddhist sites such as Yonghe Temple 雍和宮 in Beijing were also pictured. Most of the publication’s pages were devoted to essays written by members, including Zhang Taiyan, who contributed an article on Yogācāra.72 Several scriptural texts were reprinted accompanied by a detailed explication of their meanings and relevance to modern times.73 Translations also appeared, such as a story about the eternalness of the soul by one Dr. An Luozhi 安羅支博士, and sections from the Great Dictionary of Buddhism (Bukkyō daijiten 佛教大辭典, 1917), by Oda Tokunō 織田得能 (1860–1911), which were included in issues 3 and 4.74 Because of its brief print run, however, Awakening Society Collectanea had little chance to establish a pattern of content. In the final issue, published in October 1919, there was an announcement that from the following year the publication would change from a quarterly to a monthly publication and that its new name would be Voice of the Sea Tide (Haichao yin 海潮音). Around the same time, the society faded into obscurity; it is last mentioned by name in Voice of the Sea Tide in July 1921, although some branches or similarly named associations were noted in print as late as the 1930s.75 Nevertheless, although Taixu had failed in his attempted “invasion” of Jinshan, by his takeover of the editorship of Buddhist Monthly and his leadership of the Awakening Society, he succeeded in transforming the society’s periodical into a new publication, Voice of the Sea Tide, which would continue to publicize his teachings and activities for the remainder of his life.

Finally, society publications were a new venue in which Buddhists could attempt to claim authority and power in the public sphere. Yet a highly focused publication such as the Buddhist Monthly was not as effective as Awakening Society Collectanea with its close ties to a range of other scriptural and periodical publications. Its successors, Voice of the Sea Tide and many other Buddhist periodicals of the 1920s, would feature many lists, advertisements, and catalogs for other publications and often a wide range of contributors. Awakening Society Collectanea was also only one part of a much broader array of publishing activities for the society. Additionally, later groups such as the World Buddhist Householder Grove (discussed in chapter 1 in this volume) would similarly publish a society journal as well as books and series, which would be advertised in its and other periodicals.

CONCLUSION

This brief survey of three early Chinese Buddhist periodicals can only hint at the textual, doctrinal, social, and iconographic complexity evidenced by these texts. What should be clear, however, is that although these periodicals were short-lived and limited in their distribution, they were foundational publications that initiated a legacy of Buddhist elites engaging with both their own community of believers and the larger public reading world, addressing doctrinal, social, philosophical, and practical questions in a variety of literary modes and visual media. Chinese Buddhist periodicals would flourish in the 1920s and 1930s, and most would draw in some way from the earlier examples established by these three periodicals. These journals, newspapers, and magazines would function as a vibrant new type of forum for a variety of organizations and participants, mirroring the immensely influential though often fractious world of the literary and political periodical press in the late Qing and early Republic. One example of the parallels between the discourse of Buddhist periodicals and that of broader reform-minded media can be seen in the following clarion call printed in 1919 in Awakening (Juewu 覺悟), a non-Buddhist journal of the May Fourth period: “To ‘awaken’ step-by-step and to ‘progress’ step-by-step; ‘awakening’ is boundless as progress is limitless.”76 Such common pleas to “awaken” the Chinese people in well-known literary and political periodicals of this era are echoed in Buddhist calls for their version of a national and spiritual awakening. The parallels and connections between the Buddhist use of periodicals and that of wider Chinese society during the modern era should remind us that religious groups and people acting in religious roles, whether lay or ordained, were not excluded from history but were enthusiastic participants in such aspects as the use of print media.

The new print culture of the periodical press enabled Buddhist participation in Chinese modernity through its embrace of current events, organizing social networks, making the public aware of their identity and ideals, addressing political questions, and attracting new readers by means of advertisements and promotional materials. In terms of how this participation took place and how it has been remembered, there are several important parallels with other themes explored in this volume. Erik Hammerstrom describes (in chapter 2) how Buddhists played an overlooked role in disseminating modern science in China; similarly, Buddhists were at the forefront of periodical print culture, yet later studies have tended to marginalize their role in favor of that of secular publications. Gareth Fisher argues (in chapter 7) that Buddhism in post-Mao China is primarily a textual community. In their bringing together diverse and disparate contributors and later distributing their publications to a national market, Buddhist periodicals indicated the beginnings of that textual community. Periodicals served as the public face of Buddhist societies and prominent figures as well as venues for internecine battles over power and control. More than ever before, Chinese Buddhists were able to articulate themselves in relation to questions of culture, tradition, and modernity. Yet this articulation is one that, with only a few exceptions, remains largely unexplored in scholarly literature.77

NOTES

1. Liang is quoted in Joan Judge, Print and Politics: “Shibao” and the Culture of Reform in Late Qing China (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996), 4. This chapter is adapted from my PhD diss., “Conversion by the Book: Buddhist Print Culture in Early Republican China” (Columbia University, 2013). I am very grateful for the constructive criticism provided by my fellow participants at the workshop Buddhists and Buddhism in the History of Twentieth-Century China, held at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, May 30–31, 2012, particularly that provided by the two coeditors of this volume.

2. Cynthia J. Brokaw, “Commercial Woodblock Printing in the Qing (1644–1911) and the Transition to Modern Print Technology,” in From Woodblocks to the Internet: Chinese Publishing and Print Culture in Transition, circa 1800–2008, ed. Cynthia Brokaw and Christopher A. Reed (Leiden: Brill, 2010), 40–44; Christopher A. Reed, Gutenberg in Shanghai: Chinese Print Capitalism, 1876–1937 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2004); Ted Huters, “Culture, Capital, and the Temptations of the Imagined Market: The Case of the Commercial Press,” in Beyond the May Fourth Paradigm: In Search of Chinese Modernity, ed. Kai-wing Chow, Tze-ki Hon, Hung-yok Ip, and Don C. Price, 27–49 (Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books, 2008).

3. Vera Schwarcz, The Chinese Enlightenment: Intellectuals and the Legacy of the May Fourth Movement of 1919 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986); Milena Doleželová-Velingerová, Oldřich Král, and Graham Sanders, eds., The Appropriation of Cultural Capital: China’s May Fourth Project (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center, 2001).

4. Judge, Print and Politics; Schwarcz, Chinese Enlightenment, 49–50, 68–76.

5. One example of an early periodical focused on pictorials is the Dianshizhai huabao 點石齋畫報 [Dianshizhai pictorial], published in Shanghai from 1884 to 1898. See Christopher A. Reed, “Re/Collecting the Sources: Shanghai’s ‘Dianshizhai Pictorial’ and Its Place in Historical Memories, 1884–1949,” Modern Chinese Literature and Culture 12, no. 2 (fall 2000): 44–71.

6. Natascha Vittinghoff, “Readers, Publishers and Officials in the Contest for a Public Voice and the Rise of a Modern Press in Late Qing China (1860–1880),” T’oung Pao, 2nd ser., 87, fasc. 4/5 (2001): 393–455.

7. Paul J. Bailey, Reform the People: Changing Attitudes Towards Popular Education in Early Twentieth-Century China (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1990).

8. On the importance of print culture among religious groups in modern China, including Christians, Buddhists, and popular religious groups, see Philip Clart and Gregory Adam Scott, eds., Religious Publishing and Print Culture in Modern China, 1800—2012 (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2014).

9. Yang’s courtesy name was Renshan 仁山. See Holmes Welch, The Buddhist Revival in China (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1968), 2–10; Gabriele Goldfuss, Vers un bouddhisme du XXe siècle: Yang Wenhui (1837–1911), réformateur laïque et imprimeur (Paris: Collège de France, 2001); Luo Cheng 羅琤, Jinling kejingchu yanjiu 金陵刻經處硏究 [A study of the Jinling Scriptural Press] (Shanghai: Shanghai shehui kexue yuan, 2010).

10. Early Chinese Buddhist periodicals were published by Youzheng Press 有正書局, Guoguang Press 國光書局, and Zhonghua Press 中華書局, all of which had already printed periodicals before taking on the Buddhist publications.

11. Pure Land Teaching News (Jōdo kyōbō 浄土教報), for example, was founded in 1889. On Japanese Buddhist publishing in the Meiji period, see Silvio Vita, “Printings of the Buddhist ‘Canon’ in Modern Japan,” in Buddhist Asia 1: Papers from the First Conference of Buddhist Studies Held in Naples in May 2001, ed. Giovanni Verardi and Silvio Vita, 217–45 (Kyoto: Italian School of East Asian Studies, 2003); Judith Snodgrass, Presenting Japanese Buddhism to the West: Orientalism, Occidentalism, and the Columbia Exposition (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 134–35.

12. Scott, “Conversion by the Book,” chap. 5; Rudolf Löwenthal, The Religious Periodical Press in China (Beijing: Synodal Commission in China, 1940), 135–62. On other religious groups, see Xun Liu, Daoist Modern: Innovation, Lay Practice, and the Community of Inner Alchemy in Republican Shanghai (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center, 2009), chap. 6.

13. Di also used the name Baoxian 葆賢; see Judge, Print and Politics, 1–2. Youzheng Press later also published periodicals such as Woman’s Times (Funü shibao 婦女時報, 1911–1917) and Literary World (Xiaoshuo shijie 小說世界, 1923).

14. Fan Muhan 范慕韓, Zhongguo yinshua jindai shi (chugao) 中國印刷近代史(初稿) [A modern history of Chinese publishing (draft)] (Beijing: Yinshua gongye chubanshe, 1995), 275; Duan Chunxu 段春旭, “Di Chuqing zai xinwen chuban yeshang de gongxian” 狄楚卿在新聞出版業上的貢獻 [The contributions of Di Chuqing in the realm of news publishing], Chengdu daxue xuebao (jiaoyu kexue ban) 22, no. 12 (December 2008): 108; Joan Judge, “Public Opinion and the New Politics of Contestation in the Late Qing, 1904–1911,” Modern China 20, no. 1 (January 1994): 64–91; Yu Lingbo 于凌波, ed., Xiandai Fojiao renwu cidian 現代佛教人物辭典 [Biographical dictionary of modern Buddhism] (Sanchong: Foguang, 2004), 529–30; Di Baoxian 狄葆賢 [Di Chuqing 狄楚青], Pingdeng ge biji 平等閣筆記 [Notes from the Pavilion of Equality], in Xiandai Foxue daxi 現代佛學大系 [Modern Buddhist studies series], ed. Lan Jifu 藍吉富 (Taipei: Mile chubanshe, 1984), 48:89–91, 108–14; Huang Xianian 黃夏年, ed., Minguo Fojiao qikan wenxian jicheng 民國佛教期刊文獻集成 [Collection of Republican-era Buddhist periodical documents], 209 vols. (Beijing: Quanguo tushuguan wenxian suowei fuzhi zhongxin, 2006) (hereafter MFQ), 2:379. Magazine distributors are based on the list printed on the publication information page of the periodical.

15. Jichan was a Chan monk also known as the Eight-Fingered Ascetic (bazhi toutuo 八指頭陀); Unshō was a late-Meiji Japanese Shingon monk credited with inspiring the New Buddhism (shin Bukkyō 新佛教) movement; Dading and Yekai were Chan monks. See the short biography of Yekai in the journal Shijie Fojiao jushilin linkan, no. 1/2 (1925?), reprinted in Huang Xianian 黃夏年, ed., Minguo Fojiao qikan wenxian jicheng bubian 民國佛教期刊文獻集成補編 [Supplement to the collection of Republican-era Buddhist periodical documents], 83 vols. (Beijing: Zhongguo shudian, 2008) (hereafter MFQB), 7:70–71; Miaokong had helped establish the Jiangbei Scriptural Press (Jiangbei kejingchu 江北刻經處).

16. Raoul Birnbaum, “The Deathbed Image of Master Hongyi,” in The Buddhist Dead: Practices, Discourses, Representations, ed. Jacqueline Stone and Bryan Cuevas, 175–207 (Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 2007).

17. Such sources included Di Chuqing’s Shibao, Taiping yangbao 太平洋報, the Peking and Tientsin Times (Jingjin shibao 京津時報), and Shenzhou bao 神州報.

18. These sections included “Biography” (Zhuanji 傳記), “Questions and Answers” (Wenda 問答), “Literary World” (Wenyuan 文苑), “Fiction” (Xiaoshuo 小說), and “Translations” (Yicong 譯叢).

19. Buddhist Studies Magazine, no. 1 (October 1, 1912), reprinted in MFQ, 1:15–17.

20. Yinshun 印順, Taixu dashi nianpu 太虛大師年普 [Chronology of Master Taixu] (Xinzhu: Fuyan jingshe liutong, 1950), 38–39; Yu, Xiandai Fojiao renwu cidian, 530.

21. Buddhist Studies Magazine, no. 1 (October 1, 1912), reprinted in MFQ, 1:13–14.

22. Juexing 覺醒, “Yuexia fashi changdao sengqie jiaoyu” 月霞法師倡導僧伽教育 [Monastic education under the leadership of Yuexia], Xianggang Fojiao 471 (August 1999): 15–19, http://www.hkbuddhist.org/magazine/471/471_07.html. See also Shi Dongchu 釋東初, Zhongguo Fojiao jindai shi 中國佛教近代史 [A history of early modern Chinese Buddhism], in Dongchu laoren quanji 東初老人全集 [Complete works of Venerable Dongchu] (Taipei: Dongchu chubanshe, 1974), 2:755–57; Yu, Xiandai Fojiao renwu cidian, 146.

23. Jiang Weiqiao 蔣維喬, “Dixian lao fashi zhuan” 諦閑老法師傳 [Biography of Venerable Master Dixian], Hongfa yanjiu she, no. 20 (February 1933), reprinted in MFQ, 22:185–89. Eulogies appear in MFQ, 22:221–32.

24. Yu, Xiandai Fojiao renwu cidian, 1:567–71; Fan, Zhongguo yinshua jindai shi, 257–58.

25. Jan Kiely, “Spreading the Dharma with the Mechanized Press: New Buddhist Print Cultures in the Modern Chinese Print Revolution, 1866–1949,” in Brokaw and Reed, From Woodblocks to the Internet, 199–202. Gao Zhennong 高振農, “Yinguang dashi yu Shanghai Fojiao” 印光大師與上海佛教 [Master Yinguang and Buddhism in Shanghai], Xianggang Fojiao 496 (September 2001): 10–12, http://www.hkbuddhist.org/magazine/496/496_04.html. The 1917 publication is Yinguang fashi xingao 印光法師信稿 [Letters of Master Yinguang]. In a letter written to Gao Henian 高鶴年 (1872—1962), Yinguang states that a magazine (congbao 叢報) ought to have eminent laypersons “blowing the conch shell of the dharma, beating the dharma drum, its doctrines vast and deep, high as the heavens and deep as the earth.” See Yinguang dashi wenchao san bian di yi 印光大師文鈔三編第一 [Master Yinguang’s writings, third volume, section one], letter 35, http://www.minlun.org.tw/haihui/data/56/index.asp?t1=2&t2=0&t3=34.

26. Dongchu, Zhongguo Fojiao jindai shi, 2:736–38; Welch, Buddhist Revival, 16–17, 298–99n47, 319n30.

27. Cai did not identify as a Buddhist devotee but did support Buddhist causes, reportedly financially backing the publication of Buddhist Studies Magazine. His articles, under the name of Jiemin 孑民, are reprinted in MFQ, 1:49–51; MFQB, 18:287–88.

28. Ouyang is also known by his courtesy name, Jingwu 竟無. See Yu, Xiandai Fojiao renwu cidian, 1560–63; Eyal Aviv, “Differentiating the Pearl from the Fish Eye: Ouyang Jingwu (1871–1943) and the Revival of Scholastic Buddhism” (PhD diss., Harvard University, 2008).

29. Li used the courtesy name Zhenggang 證剛. See Liu Jianqing 劉劍青, “Linchuan Li Yizhuo xiansheng yishu luëzheng lu xu” 臨川李翊灼先生遺書略征錄序 [Preface to the Linchuan native Mr. Li Yizhuo’s posthumous writing: Travel sketches], Fayin, no. 2 (March 1985): 21–22.

30. Other contributors included Li Duanfu 黎端甫 (dates unknown) and Gao Henian, as well as Anagarika Dharmapala (1864—1933), whose article on Buddhism and society appears in MFQ, 4:185–89.

31. Li’s essay appeared in every issue of the periodical, while Yuexia’s was serialized in nos. 5–12 and still had additional sections to be published.

33. Examples include Pure Land Teaching News and the long-running Essence of Religion (Shūsui 宗粹), founded by Mochizuki Shinkō 望月信亨 (1869–1948). See the works by Vita and Snodgrass cited in note 11.

34. MFQ, 1:109–88, 121; Welch, Buddhist Revival, 33–35.

35. MFQ, 1:131. Vincent Goossaert, “1898: The Beginning of the End for Chinese Religion?” Journal of Asian Studies 65, no. 2 (May 2006), 328–31; Tai Shuangqiu 邰爽秋, Miaochan xingxue wenti 廟產興學問題 [The problem of seizing temple property to promote education] (Shanghai: Zhonghua shubao liutong she, 1929).

36. Scott, “Conversion by the Book,” chap. 1, sec. 4, chap. 5, sec. 4.

37. Buddhist Studies Magazine, no. 12 (June 15, 1914), reprinted in MFQ, 4:549–69.

39. Ibid., 3:145–48, 227–68, 309–12; 4:2. For an announcement of the association’s charter, see Buddhist Monthly, no. 3, reprinted in MFQ, 6:67–68.

40. Yang Wenhui 楊文會, comp., Foxue shumu biao 佛學書目表 [Book catalog of Buddhist studies] (Nanjing: Jinling kejing chu, [1902]), reprinted in Yang Wenhui, Yang Renshan quanji 楊仁山全集 [Complete works of Yang Renshan], 344–68 (Hefei: Huangshan shushe, 2000); see also MFQ, 4:546–69.

41. MFQ, 2:179–80; 4:176, 469–80.

42. Ibid., 205:1. See announcements of publication delays ibid., 1:368; 2:182; 4:346.

43. The constitution of the Chinese General Buddhist Association is printed in ibid., 5:131–43.

44. Welch, Buddhist Revival, 35–38, 301n23; Dongchu, Zhongguo Fojiao jindai shi, 1:102–5; MFQ, 5:137, 387–88; 205:1. After the association went defunct some time in 1914, it was briefly revived in 1917 in Beijing as the Chinese Buddhist Association (Zhonghua Fojiao hui 中華佛教會) but was ordered dissolved in 1919 when authorities discovered that it had been “set up contrary to law.” See Welch, Buddhist Revival, 38–39.

45. The press was the publishing arm of the Divine Continent National Glory Society (shenzhou guoguang she 神州國光社), founded in the last decade of the Qing by the artist Huang Binhong 黃賓虹 (1865–1955) and the historian Deng Shi 鄧實 (1877–1951). On Deng, see Fan, Zhongguo yinshua jindai shi, 282.

46. Welch, Buddhist Revival, 51–71; Don A. Pittman, Toward a Modern Chinese Buddhism: Taixu’s Reforms (Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 2001); Yinshun, Taixu dashi nianpu.

47. Yakun had studied under Yang Wenhui and founded the Universal Monastic Study Hall (putong sengxue tang 普通僧學堂) at Tianning Temple in Yangzhou in 1906. See MFQ, 5:119–21; Zuo Songtao 左松濤, “Jindai Zhongguo Fojiao xingxue zhi yuanqi” 近代中國佛教興學之緣起 [The origins of the revival of modern Chinese Buddhism], Fayin 282 (2008): 34–38.

49. Ibid., 12–14. See also Schwarcz, Chinese Enlightenment, 286–91.

50. Yu Lingbo 于凌波, Minguo gaoseng zhuan chubian 民國高僧傳初編 [Initial volume of biographies of eminent monks of the Republican era] (Xindian: Yuanming chubanshe, 1998), 45; Yu, Xiandai Fojiao renwu cidian, 389. See also Chongxing Qingliang si shuilu fahui tekan 重興清涼寺水陸法會特刊 [Special issue on the dharma assembly of water and land at the renovated Qingliang Temple (1937)], reprinted in MFQB, vol. 58.

51. The other editor was Zhifu 智府. On Taixu, see Welch, Buddhist Revival, 28–33.

52. Yu, Xiandai Fojiao renwu cidian, 1:1267; Dongchu, Zhongguo Fojiao jindai shi, 2:804–5. Gao’s article is in MFQ, 5:267–71; 6:334–39.

54. The first such chart appeared in issue no. 2; reprinted in MFQ, 5:389–98. The second was presented in issues 3 and 4; reprinted in MFQ, 6:71–77, 281–84, where a considerably smaller number of local associations are listed. Whether these branches ever existed except on paper is an open question.

55. MFQ, 5:125–30, 183–204.

56. Ibid., 346, 366, 378; 6:12.

57. Ibid., 6:185–86. Neither of these issues was ever published, and neither article appears in later bibliographic sources.

59. From issue no. 3 onward, it is also called simply Jueshu 覺書 and often appears in library catalogs under this title.

60. MFQ, 7:168, repeated on 7:318. A longer statement of purpose appears in MFQ, 6:384–87.

61. Ibid., 7:156; Pittman, Toward a Modern Chinese Buddhism; Welch, Buddhist Revival, 52–54. On Wang Yiting, see Kang Bao 康豹 [Paul R. Katz], “Yige zhuming Shanghai shangren yu cishan jia de zongjiao shenghuo—Wang Yiting” 一個著名上海商人與慈善家的宗教生活—王一亭 [The religious life of a renowned Shanghai businessman and philanthropist: Wang Yiting], in Cong chengshi kan Zhongguo xiandaixing 從城市看中國現代性 [An urban perspective on Chinese modernity], ed. Wu Renshu 巫仁恕, Lin Meili 林美莉, and Kang Bao 康豹 [Paul R. Katz], 275–96 (Nankang: Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica, 2010).

62. Awakening Society Collectanea, issue nos. 2 and 3, reprinted in MFQ, 7:168, 318. See also MFQB, 1:104; MFQ, 6:501–2; 7:156–58.

63. MFQ, 7:153–56; 6:503; 7:316; Yinshun, Taixu dashi nianpu, entry for 1919. See also MFQ, 7:168; MFQB, 1:42. The four departments were Buddhist Education (Fojiao jiangxi 佛教講習), Scripture Reading (Fojing yuelan 佛經閱覽), Compilation of Buddhist Studies (Foxue bianji 佛學編輯), and Printing and Distribution of Buddhist Books (Foshu banxing 佛書版行). For a list of regulations of the first two departments, see MFQ, 7:312–15.

64. Ding’s courtesy name was Zhongyou 仲祐. See MFQ, 7:272; MFQB, 1:124, 310. On Ding, see Gregory Adam Scott, “Navigating the Sea of Scriptures: The Buddhist Studies Collectanea, 1918–1923,” in Clart and Scott, Religious Publishing.

65. MFQ, 6:388; 7:144, 212; MFQB, 1:72, 332.

66. The press had absorbed Ding Fubao’s Wenming Press (Wenming shuju 文明書局) and the Progressive Press (Jinbu shuju 進步書局) and survived a period of near bankruptcy in 1917–1918. See Reed, Gutenberg in Shanghai, 225–38; Fan, Zhongguo yinshua jindai shi, 289–90; Zhou Qihou 周其厚, Zhonghua shuju yu jindai wenhua 中華書局與近代文化 [Zhonghua Books and modern culture] (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2007), 46–47; Liu Hongquan 劉洪權, ed., Minguo shiqi chuban shumu huibian 民國時期出版書目彙編 [Collected publishing catalogs from the Republican era] (Beijing: Guojia tushuguan chubanshe, 2010), 4:317.

67. Based on distribution lists in MFQ, 6:480, 498, 504, and elsewhere in the periodical.

68. Chen’s courtesy name was Yushi 裕時. See Dongchu, Zhongguo Fojiao jindai shi, 2:517–18. On Tongshanshe, see Vincent Goossaert and David A. Palmer, The Religious Question in Modern China (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 100–101.

69. Huang had also used the lay name Kaiyuan 愷元. See Zhongguo Renmin Zhengzhi Xieshang Huiyi Hubei Sheng Weiyuanhui 中國人民政治協商會議湖北省委員會, Xinhai shouyi huiyi lu 辛亥首義回憶錄 [Records of the Xinhai revolution] (Wuhan: Hubei renmin chubanshe, 1979), 124–25; Yu, Xiandai Fojiao renwu cidian, 45. A memorial to Daci by Chen appears in MFQ, 158:132.

70. Howard L. Boorman ed., Biographical Dictionary of Republican China (New York: Columbia University Press, 1970), 1:358–60.

71. MFQ, 6:360; 7:156. According to Boorman, Biographical Dictionary, however, Jiang was in the United States from September 1917 to November 1918.

72. MFQ, 7:14–19; MFQB, 13:149–52; MFQ, 29:58–61.

74. A section from fasc. 28 of Da fangguang Fo huayan jing suishu yanyi chao 大方廣佛華嚴經隨疏演義鈔 [An informal collection of discourses and commentaries on the Huayan Sūtra; T 1736.36.1a–701a] by Chengguan 澄觀 (738–839) appears in issue no. 1, while Dasheng qixin lun 大乘起信論 [The awakening of Mahāyāna faith; T 1666.32.575b–583b] is explicated by Taixu in issue no. 2. See MFQ, 6:443–49; 7:53–132. Titles and locations in the Taishō canon are based on entries in the Digital Dictionary of Buddhism, http://www.buddhism-dict.net/ddb/.

75. MFQ, 6:457–79; 7:249–50; MFQB, 1:68–71. An Luozhi was likely Sir Robert Anderson (1841–1918), who wrote on Christianity, theosophy, and Buddhism.

76. MFQB, 1:179; MFQ, 150:498. An Awakening Society based in Sichuan is mentioned in the Foxue banyue kan in September 1921, while a Fuzhou qingnian jueshe 福州青年覺社) appeared in print in August 1926. See MFQ, 151:194; 165:369. A Suzhou society (Suzhou jueshe 蘇州覺社) was quite active in the 1930s, publishing its own periodical, Jueshe niankan 覺社年刊. See MFQ, 48:358; 205:23. It is not yet clear what relationship, if any, these groups had to the Shanghai organization. Many articles were collected and reprinted as Jueshe congshu xuanben 覺社叢書選本 [Selected works from Awakening Society Collectanea], published by Wuchang Scriptural Press (Wuchang yinjing chu 武昌印經處) in 1923. See MFQB, vol. 13.

77. Juewu, December 29, 1919, 415; quoted in Leo Ou-fan Lee, “Incomplete Modernity: Rethinking the May Fourth Intellectual Project,” in Doleželová-Velingerová, Král, and Sanders, Appropriation of Cultural Capital, 59. For more on the theme of awakening in the Qing to Republican-era transition, see John Fitzgerald, Awakening China: Politics, Culture, and Class in the Nationalist Revolution (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996).

78. Hung-yok Ip, “Buddhism, Literature, and Chinese Modernity: Su Manshu’s Imaginings of Love (1911–1916),” in Beyond the May Fourth Paradigm: In Search of Chinese Modernity, ed. Kai-wing Chow, Tze-ki Hon, Hung-yok Ip, and Don C. Price (Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books, 2008): 229–51.